LAO Contact

Update (10/20/22): A previous version of this report excluded $2.5 billion in targeted legislative augmentations from the discretionary spending total. As a result, our estimate of the surplus has increased.

October 12, 2022

The 2022-23 Budget

Overview of the Spending Plan (Final Version)

- Introduction

- Budget Overview

- Evolution of the Budget

- Major Features of the 2022‑23 Spending Plan

- Appendix

Introduction

Each year, our office publishes the California Spending Plan to summarize the annual state budget. This publication provides an overview of the 2022‑23 Budget Act, gives a brief description of how the budget process unfolded, and then highlights major features of the budget approved by the Legislature and signed by the Governor. All figures in this publication reflect actions taken through July 1, 2022, but we have updated the narrative to reflect actions taken later in the legislative session. In addition to this report, we have released a series of issue‑specific, online posts that give more detail on the major actions in the budget package.

Budget Overview

Budget Condition

Figure 1 summarizes the condition of the General Fund under the revenue and spending assumptions in the July 2022 budget package, as estimated by the administration.

Figure 1

General Fund Condition Summary

(In Millions)

|

2020‑21 |

2021‑22 |

2022‑23 |

|

|

Prior‑year fund balance |

$5,889 |

$38,335 |

$22,451 |

|

Revenues and transfers |

194,575 |

227,061 |

219,707 |

|

Expenditures |

162,129 |

242,944 |

234,366 |

|

Ending fund balance |

$38,335 |

$22,451 |

$7,791 |

|

Encumbrances |

$4,276 |

$4,276 |

$4,276 |

|

SFEU balance |

$34,058 |

$18,174 |

$3,515 |

|

Reserves |

|||

|

BSA |

$14,643 |

$20,320 |

$23,288 |

|

SFEU |

34,059 |

18,175 |

3,515 |

|

Safety net |

900 |

900 |

900 |

|

Total Reserves |

$49,602 |

$39,395 |

$27,703 |

|

Note: Reflects administration estimates of budget actions taken through July 1, 2022. |

|||

|

SFEU = Special Fund for Economic Uncertainties and BSA = Budget Stabilization Account. |

|||

Total General Fund Reserves Reach Nearly $28 Billion Under Spending Plan. As shown at the bottom of Figure 1, the budget package assumes that 2022‑23 will end with nearly $28 billion in total reserves. This consists of: (1) $23.3 billion in the Budget Stabilization Account; (2) $3.5 billion in the Special Fund for Economic Uncertainties (SFEU); and (3) $900 million in the Safety Net Reserve, which is available for spending on the state’s safety net programs, like Medi‑Cal.

Proposition 98 Reserve Also Reaches $9.5 Billion. In addition to the general‑purpose reserves described above, the Proposition 98 Reserve (dedicated to school and community college spending) would reach $9.5 billion under the spending plan. We do not include this reserve in the total because withdrawals supplement the constitutional minimum spending level for K‑14 education and therefore do not help the state address future budget problems. However, this reserve does benefit schools and community colleges because it mitigates the funding reductions that occur when the constitutional minimum drops.

Revenues

Figure 2 displays the administration’s revenue projections as incorporated into the July 2022 budget package. The most notable change between 2021‑22 and 2022‑23 is the drop in corporation tax revenues. Most of this drop is due to timing issues related to a recent change in how the state taxes pass‑through businesses. These changes resulted in a one‑time revenue boost in 2021‑22, which tapered off beginning in 2022‑23.

Figure 2

General Fund Revenue Estimates

(Dollars in Millions)

|

Revised |

Enacted |

Change From 2021‑22 |

|||

|

2020‑21 |

2021‑22 |

Amount |

Percent |

||

|

Personal income tax |

$128,856 |

$136,497 |

$137,506 |

$1,008 |

1% |

|

Sales and use tax |

29,073 |

32,750 |

33,992 |

1,242 |

4 |

|

Corporation tax |

22,591 |

46,395 |

38,464 |

‑7,932 |

‑17 |

|

Totals, Major Revenue Sources |

$180,519 |

$215,642 |

$209,961 |

‑$5,681 |

‑3% |

|

Insurance tax |

$3,139 |

$3,468 |

$3,667 |

$199 |

6% |

|

Other revenues |

3,152 |

3,771 |

9,421 |

5,650 |

150 |

|

Transfer to/from Budget Stabilization Account |

2,707 |

‑5,677 |

‑2,968 |

2,709 |

‑48 |

|

Other transfers and loans |

5,057 |

9,856 |

‑375 |

‑10,231 |

‑104 |

|

Totals, Revenues and Transfers |

$194,575 |

$227,061 |

$219,707 |

‑$7,354 |

‑3% |

|

Note: Reflects administration estimates of budget actions taken through July 1, 2022. |

|||||

Policy Changes Reduce Tax Revenues. The budget package includes several policy changes which reduce tax revenues. These changes are expected to reduce revenues in 2021‑22 and 2022‑23 by $2.2 billion and $4.2 billion, respectively. The most significant policy change is the early elimination of limits on business’ use of certain tax credits and deductions to reduce their tax payments. These limits originally were put in place for tax years 2020 through 2022, but the budget package ended the limits for 2022. The budget package also includes tax relief for businesses receiving pandemic assistance from various federal programs. Finally, the budget package makes some changes related to the state’s cannabis taxes (which are special fund revenues and not included in Figure 2). The plan moves the point of collection for the retail excise tax from distributors to retailers, and it also eliminates the cultivation tax. To address the resulting loss of cultivation tax revenue, the plan appropriates $150 million General Fund in 2023‑24 and authorizes periodic administrative adjustments to the retail excise tax rate.

Spending Plan Provides One‑Time Refund Payments to Most California Taxpayers. In addition to the revenue policy changes described above, the spending plan includes $9.5 billion General Fund for a one‑time tax refund payment, the Better for Families Refund, also known as the Middle Class Tax Refund. Payments will be made to taxpayers with adjusted gross income (AGI) below $500,000 (for joint filers) and $250,000 (for single filers). The payment amount is based on AGI, with larger payments going to taxpayers with lower income levels. For example, a married couple with two children whose AGI was $100,000 will receive $1,050. A similar family with AGI of $300,000 will receive $600. The stated intent of the refund is to help offset higher costs resulting from recent inflation. (In the budget accounting, a refund is scored as spending, rather than a revenue reduction, however.)

Spending

Figure 3 displays the administration’s July 2022 estimates of total state and federal spending in the 2022‑23 budget package. As the figure shows, the spending plan assumes total state spending of $303 billion in 2022‑23. This represents a slight decrease (2 percent) over the 2021‑22 level. However, that decrease is attributable to the spending plan scoring new discretionary spending, particularly for spending that meets the definition of capital outlay under the state appropriations limit (SAL), to 2021‑22. The next section describes some of the major discretionary spending choices reflected in the spending plan.

Figure 3

Total State and Federal Fund Expenditures

(Dollars in Millions)

|

Revised |

Enacted |

Change From 2021‑22 |

|||

|

2020‑21 |

2021‑22 |

Amount |

Percent |

||

|

General Fund |

$164,129 |

$242,944 |

$234,366 |

‑$8,578 |

‑4% |

|

Special funds |

58,170 |

66,098 |

69,119 |

3,021 |

5 |

|

Budget Totals |

$222,299 |

$309,042 |

$303,485 |

‑$5,557 |

‑2% |

|

Bond funds |

$6,291 |

$9,907 |

$4,431 |

‑$5,476 |

‑55% |

|

Federal funds |

272,294 |

318,949 |

143,614 |

‑175,335 |

‑55 |

|

Note: Reflects administration estimates of budget actions taken through July 1, 2022. |

|||||

Federal Funds Expected to Decline Significantly Between 2021‑22 and 2022‑23. The figure also shows federal funds decline $175 billion, or 55 percent, between 2021‑22 and 2022‑23. This decline is the result of several significant federal programs enacted in response to COVID‑19 expiring in 2022‑23. For example, funding the state receives for federally enhanced unemployment insurance benefits are accounted for in the Employment Development Department (EDD) budget. Under the administration’s assumptions, federal spending in EDD would decline from $34 billion in 2021‑22 to $7 billion in 2022‑23. Other federal programs also are expected to expire in 2022‑23, including the enhanced Federal Medical Assistance Percentage for the state’s Medicaid program (which the administration assumes will expire in December 2022) and $27 billion in fiscal relief funding from the American Rescue Plan. However, there are also some increases in federal funds in 2022‑23 related to the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act.

Hundreds of Millions of Dollars in Additional Augmentations Linked to “Trigger” Language in 2024‑25. Chapter 48 of 2022 (SB 189, Committee on Budget and Fiscal Review) contains trigger language that prioritizes specified future program augmentations if certain conditions are met. Figure 4 lists these program augmentations. In the spring of 2024, the state will assess whether the General Fund can support these augmentations over the multiyear forecast. Though prioritized for funding in 2024‑25, these program augmentations are not automatic. If the General Fund is determined to be able to support the augmentations, subsequent legislation still would be needed to enact them.

Figure 4

Augmentations for 2024‑25

Prioritized by Trigger‑On Language

(In Millions)

|

Augmentation |

Amounta |

|

CalWORKs maximum aid payment increase |

TBDb |

|

Tax credit to offset costs of union membership |

$400 |

|

Cal Grant reform |

365 |

|

Full pass‑through of child support payments to CalWORKs families |

TBDc |

|

Victim compensation eligibility, benefits, and administration |

50 |

|

Align income levels for maintenance with income limits in Medi‑Cal |

33d |

|

Eliminate restitution fines |

25 |

|

Continuous Medi‑Cal eligibility for children ages 0 to 4 |

20 |

|

Cal Grant CCC Expanded Entitlement award portability to nonprofit schools |

10 |

|

aEstimated cost in 2024‑25. For some items, reflects a partial‑year cost. bTrigger language does not specify an amount for the increase, could range from low hundreds of millions of dollars to more than $1 billion. cTrigger language does not specify an amount for the full pass‑through. The administration has estimated costs of roughly $150 million, but actual costs will depend on collections and caseload at the time of implementation. dIncreases to $80.2 million in 2025‑26 and ongoing. |

|

|

TBD = to be determined. |

|

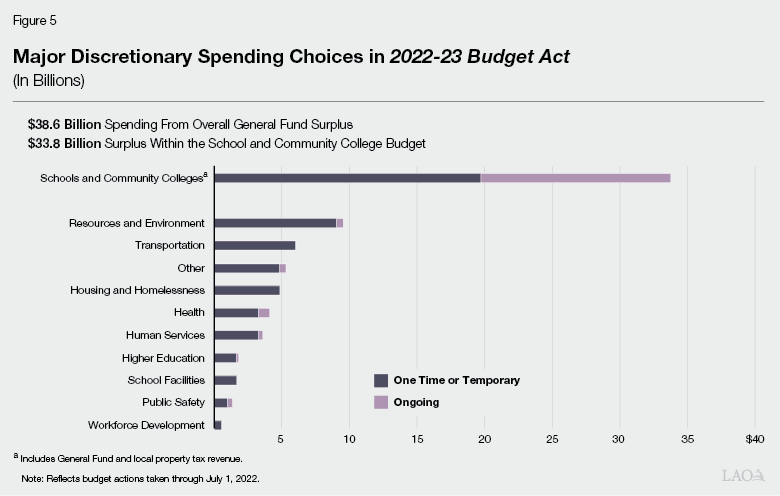

The Surplus

Budget Package Includes $72.4 Billion in Discretionary General Fund Spending Choices. Figure 5 displays the major discretionary spending decisions in the 2022‑23 Budget Act. It includes: (1) the $38.6 billion in spending choices using the overall General Fund surplus (this figure only includes the amount spent from the surplus and excludes reserve deposits, tax refunds, and debt payments, which are shown instead in Figure 6) and (2) the $33.8 billion surplus within the school and community college budget. As the figure shows, schools and community colleges would receive the largest spending allocations reflecting the significant growth in Proposition 98. Within the overall General Fund surplus, most spending amounts were dedicated to resources and the environment, transportation, health, and housing and homelessness. The remainder of this section discusses the major components of each of these funding amounts.

Overall General Fund Surplus

A surplus occurs when, over the three‑year budget window, the state anticipates collecting more in General Fund revenues than it requires to meet its existing obligations. Put another way, the overall General Fund surplus is the amount of revenue available for new spending commitments after paying for the costs of programs under current law. (If, instead, we found spending under current law was higher than projected revenues, we would use the phrase “deficit” or “budget problem” to describe the difference.)

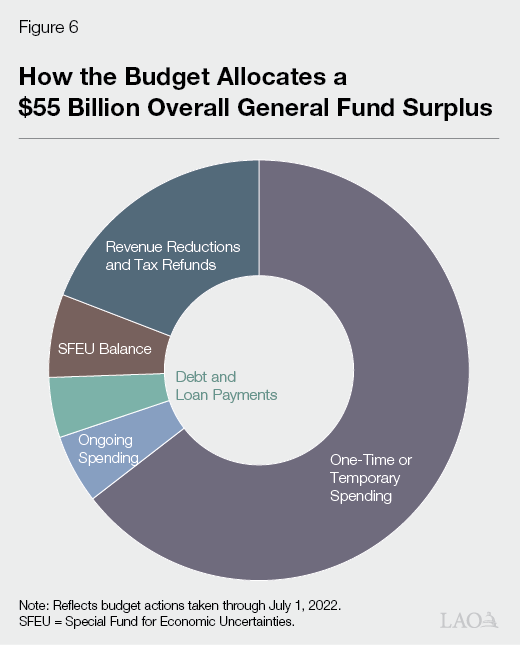

Spending Plan Allocated a $55 Billion Overall General Fund Surplus. We estimate the Legislature had a $55 billion overall General Fund surplus to allocate in the 2022‑23 Budget Act. The surplus is about $3 billion larger than our estimate at the time of the May Revision due to changes in federal funds assumptions and some workload budget adjustments. Figure 6 shows how the 2022‑23 Budget Act allocated that surplus. Overall, we estimate 96 percent of the surplus was devoted to one‑time or temporary purposes and 4 percent is ongoing. Specifically, the budget allocated:

- $36.3 Billion to One‑Time or Temporary Spending. The spending plan used 64 percent of the overall General Fund surplus, or $36.3 billion, for one‑time or temporary programmatic expansions. (We define temporary to mean three years or fewer.)

- $10.5 Billion to Revenue Reductions and Tax Refunds. The spending plan used $10.5 billion, about 20 percent of the overall General Fund surplus, to reduce revenues. (Nearly all of these revenue‑related amounts are one time or temporary.) In particular, this category includes the $9.5 billion Better for Families Tax Refund, one‑time payments to households with incomes up to $500,000.

- $3.5 Billion to Maintaining Reserves. The spending plan enacts a year‑end balance in the SFEU of $3.5 billion. (This amount is technically discretionary because the Legislature can choose to set the balance of the SFEU to any amount above zero. However, recent budgets have enacted SFEU balances around $2 billion to $4 billion, which the state uses to cover costs for unanticipated expenditures.)

- $2.3 Billion to Ongoing Spending Increases. The spending plan includes $2.3 billion in ongoing spending increases, using about 4 percent of the surplus. The ongoing costs of these augmentations would grow over time, reaching $4.9 billion by 2025‑26.

- $2.5 Billion to Pay Off Debts and Liabilities. Each year, the state pays many billions of dollars towards debts and liabilities. (Under the spending plan, for example, the state would make $3.4 billion in constitutionally required debt payments under Proposition 2, as well as other routine debt payments made by the state, such as annual actuarially required contributions to the state’s pension systems, debt service on state bonds, and the state’s plan to prefund retiree health.) In addition to these routine payments, the spending plan uses $2.5 billion from the overall General Fund surplus funds to repay state debts and liabilities. This includes $1.9 billion for converting some projects currently funded by lease revenue bonds to cash and repaying around $600 million in special fund loans to the General Fund.

Surplus Within the School and Community College Budget

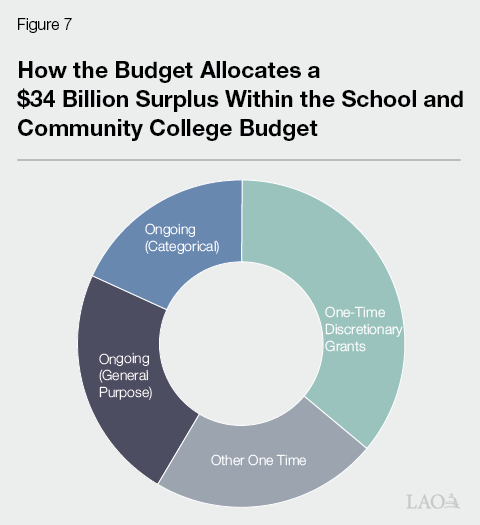

Total state spending on schools and community colleges is determined mainly by a set of constitutional formulas set forth in Proposition 98 (1988). These formulas establish a minimum funding requirement for K‑14 education, commonly known as the minimum guarantee. The state meets the guarantee through a combination of General Fund and local property tax revenue. The Legislature, in turn, decides how to allocate this funding among specific school and community college programs. When the guarantee exceeds the cost of existing programs, the state has a “surplus” within the school and community college budget. This amount is separate from the overall General Fund surplus and must be allocated for school and community college programs (or deposited into the Proposition 98 Reserve).

How the Budget Allocates the Surplus Within the K‑14 Education Budget. After setting aside funding for statutory cost‑of‑living adjustments (COLAs) and other planned program expansions, the budget plan includes $33.8 billion in discretionary spending proposals to meet the minimum required funding level for schools and community colleges. As Figure 7 shows, the spending plan includes $7.9 billion for ongoing increases to the main school and community college funding formulas and $6.2 billion for ongoing increases to restricted categorical programs. The budget plan also includes $19.7 billion in one‑time funding, of which $12.1 billion is for discretionary block grants to schools and community colleges.

State Appropriations Limit

The SAL limits how the state can use revenues that exceed a certain limit. When revenues are expected to exceed the limit before the state makes its discretionary budget choices, it has a SAL requirement. (In other words, a SAL requirement is the amount of revenue the state is required to allocate in ways that meet its constitutional requirements under Proposition 4.) The Legislature can meet SAL requirements by: (1) reducing taxes or issuing tax refunds, (2) spending more on excluded purposes (categories of excluded spending include: subventions to local governments, debt service, federal and court mandates, capital outlay, and emergency spending), or (3) splitting excess revenues between tax refunds and additional school spending. For more information on how the SAL works, see our report: The State Appropriations Limit.

State Revenues Not Expected to Exceed Appropriations Limit. Figure 8 shows the administration’s July 2022 SAL estimates after accounting for all of the spending plan decisions. As the figure shows, 2020‑21 would end with “negative room” (appropriations subject to the limit above the limit) of $16 billion. However, 2021‑22 would have positive room of $29 billion. Because the state’s SAL position is considered on net over two fiscal years, these two years have roughly $13 billion in room remaining, meaning there are no excess revenues in 2020‑21 and 2021‑22. Further, while the Governor’s May Revision left $3.4 billion in unaddressed SAL requirements for 2022‑23, the July budget package reflects different choices. As a result, under the spending plan, the administration estimates the state would have $12 billion in room in that year.

Figure 8

SAL Estimates in the 2022‑23 Budget Act

(In Billions)

|

2020‑21 |

2021‑22 |

2022‑23 |

|

|

SAL revenues and transfers |

$216 |

$256 |

$252 |

|

Exclusions |

‑84 |

‑160 |

‑129 |

|

Appropriations Subject to the Limit |

$132 |

$97 |

$123 |

|

Limit |

$116 |

$126 |

$136 |

|

Room/Negative Room |

‑$16 |

$29 |

$12 |

|

Excess Revenues? |

No |

||

|

Note: Reflects administration estimates of budget actions taken through July 1, 2022. |

|||

|

SAL = state appropriations limit. |

|||

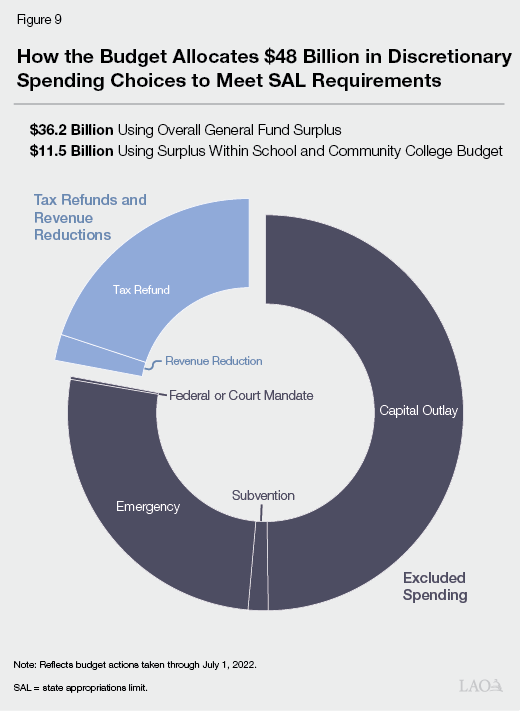

Budget Allocates $48 Billion of Surplus to Discretionary Choices That Address SAL Requirements. A key reason that the state does not have excess revenues across 2020‑21 and 2021‑22 (as well as room under the limit in 2022‑23) is that the spending plan includes $48 billion in discretionary choices that meet SAL requirements across the budget window. This includes:

- $36.2 Billion From the Overall General Fund Surplus. The spending plan dedicates about 66 percent of the overall General Fund surplus to meeting SAL requirements, including $24 billion in spending proposals, $10.5 billion in tax refunds and other revenue reductions, and nearly $2 billion in debt payments—specifically, the state’s conversion of some lease revenue bonds to cash.

- $11.5 Billion From the Surplus Within the Schools and Community Colleges Budget. In addition, the spending plan dedicates one‑third of the surplus within the schools and community colleges budget, or $11.5 billion, for SAL‑excluded purposes. The largest components of these exclusions are $8.6 billion in emergency spending for discretionary block grants to assist schools and community colleges in the long‑term recovery from the COVID‑19 pandemic, $1.4 billion to purchase electric school buses, and $630 million for community college facilities maintenance and instructional equipment.

Figure 9 shows the distribution of the $48 billion in discretionary resources that meet SAL requirements by type. As the figure shows, more than three‑quarters of the total is dedicated to excluded spending, including about half going to capital outlay projects. (Importantly, the definition of capital outlay under the SAL is more expansive than the typical definition in the budget.) Some of the largest augmentations that meet this definition include: over $5 billion for various components of the transportation infrastructure package, nearly $2 billion (across the budget window) for the strategic reliability reserve (part of the Energy Package), $1.6 billion for the Behavioral Health Continuum Infrastructure Program (part of the Housing Bridge program), and $1.3 billion for the school facilities aid program. Just less than one‑quarter of the SAL‑related budget choices are for revenue reductions and tax refunds, including the $9.5 billion Better for Families tax refund. (The box nearby also describes some administrative and statutory changes to the SAL calculation reflected in the spending plan, which result in lower SAL requirements across the budget window.) We plan to discuss the SAL estimates and major SAL‑related decisions in the 2022‑23 budget package in more detail in a forthcoming post.

Administrative and Statutory Changes to the State Appropriations Limit (SAL) Calculation

Modifies the Definition of Subvention. The State Constitution allows subventions to local governments to be counted against that local government’s limit (instead of the state’s limit). Previously, the definition of subvention included only state funding to local government that was unrestricted. (This change built on actions taken last year, which we described here). Chapter 48 of 2022 (SB 189, Committee on Budget and Fiscal Review) expanded the definition of subvention to also include a variety of other specific streams of funds, as listed in Government Code 7903. For example, subventions will now include funds to counties for the administration of health and human services programs like Medi‑Cal. In addition, the new law requires local agencies to identify and report any new state subventions that would cause that entity to exceed its own appropriations limit so that the state can continue to count those amounts at the state level instead.

Counts More School District Capital Outlay Expenditures. School districts, like local governments and the state, have their own appropriations limits. State law requires most school districts to set aside a portion of their general‑purpose funding for the ongoing and major maintenance of their facilities. Districts currently set aside approximately $2.2 billion per year related to this requirement. These funds meet the definition of capital outlay for SAL purposes, and so the spending plan adopts a plan to require school districts to exclude this spending from their limits. Because of the way school district limits interact with the state’s limit, excluding this change results in dollar‑for‑dollar reductions in appropriations subject to the limit at the state level.

Counts Certain Information Technology (IT) Expenditures as Excluded. Previous spending plans did not categorize IT expenditures as SAL excludable, but this year’s spending plan identifies IT expenditures totaling $226.5 million General Fund in 2021‑22 and $478.8 million General Fund in 2022‑23 as expenditures on qualified capital outlay excluded from the SAL calculation. These expenditures include most IT project development and implementation costs and software licensing costs. Expenditures not currently identified as SAL excludable include hardware costs, IT project planning costs, and most IT system maintenance and operations costs.

Evolution of the Budget

This section provides an overview of the 2022‑23 budget process. Figure 10 lists the budget and budget‑related legislation passed as of July 1, 2022.

Figure 10

Budget‑Related Legislation Passed on or Before July 1, 2022

|

Bill Number |

Chapter |

Subject |

|

Budget Bills and Amendments |

||

|

SB 154 |

43 |

2022‑23 Budget Act |

|

AB 180 |

44 |

Amendments to the 2021‑22 Budget Act |

|

AB 178 |

45 |

Amendments to the 2022‑23 Budget Act |

|

Trailer Bills Passed on or Before July 1, 2022 |

||

|

AB 181 |

52 |

Education |

|

AB 182 |

53 |

Education: Learning Loss Recovery Fund |

|

AB 183 |

54 |

Higher education |

|

AB 186 |

46 |

Skilled nursing facilities financing |

|

AB 192 |

51 |

Better for Families Tax Refund |

|

AB 194 |

55 |

Revenue and taxes |

|

AB 195 |

56 |

Cannabis |

|

AB 199 |

57 |

Courts |

|

AB 200 |

58 |

Public safety |

|

AB 202 |

59 |

Public safety infrastructure |

|

AB 203 |

60 |

Resources |

|

AB 205 |

61 |

Energy |

|

AB 210 |

62 |

Early childhood education |

|

SB 125 |

63 |

Resources: Lithium Valley |

|

SB 130 |

64 |

State employee compensation |

|

SB 131 |

65 |

Elections |

|

SB 132 |

66 |

State employee compensation |

|

SB 184 |

47 |

Health |

|

SB 187 |

50 |

Human services |

|

SB 188 |

49 |

Developmental services |

|

SB 189 |

48 |

State government, 2024‑25 budget trigger |

|

SB 191 |

67 |

Employment/labor |

|

SB 193 |

68 |

Economic development |

|

SB 196 |

69 |

State employee compensation |

|

SB 197 |

70 |

Housing |

|

SB 198 |

71 |

Transportation |

|

SB 201 |

72 |

Tax credits |

|

Note: This figure includes budget bills and trailer bills identified in Section 39.00 in the 2022‑23 Budget Act that were enacted into law on or before July 1, 2022. Ordered by bill number. |

||

Governor’s January Budget Proposal

On January 10, 2022, Governor Newsom presented his proposed state budget to the Legislature, marking the formal beginning of the 2022‑23 budget process. At the time of the Governor’s budget, and under the administration’s revenue estimates, we estimated the Governor had a $29 billion surplus to allocate in the 2022‑23 budget process. This surplus was nearly entirely the result of higher revenue collections and estimates compared to 2021 budget projections. The Governor proposed spending about 60 percent of discretionary resources, or $17.3 billion, on a one‑time or temporary basis for a variety of programmatic expansions. The Governor also proposed using $6.2 billion to reduce revenues and $2 billion for ongoing spending increases. In addition, the Governor’s budget allocated a nearly $13 billion surplus within the schools and community colleges budget.

Governor’s May Revision

On May 13, 2022, Governor Newsom presented a revised state budget proposal to the Legislature (called the “May Revision”). At the time of the May Revision, and under the administration’s revenue estimates, we estimated the Governor had a $52 billion surplus to allocate in the 2022‑23 budget process. This surplus was higher than the January estimate for three reasons. First, revenues were higher by nearly $57 billion compared to the Governor’s budget, reflecting continued, unprecedented growth in revenue collections. Second, offsetting this increase in revenues, constitutional spending requirements were higher by $23 billion. Third, also offsetting the increase in revenues, baseline spending was also higher by $11 billion. This was primarily the result of early legislative action, including adopting $5.7 billion in a variety of revenue reductions—such as the restoration of net operating loss deductions—and $2.7 billion for rental assistance. (The final budget package reflected a slightly lower appropriation amount, $2 billion, for rental assistance.)

Legislature’s Budget Package

The Legislature passed an initial budget package on June 13, 2022. The Legislature’s budget package provided the same level of overall spending for schools and community colleges as the May Revision, but designated more ongoing and one‑time funding for discretionary purposes. Relative to the May Revision, the Legislature’s budget also: (1) rejected the Governor’s transportation‑related relief proposals and instead provided tax rebates of $200 per taxpayer and dependent for those with incomes below $125,000 ($250,000 for joint filers) and one‑time cash assistance to Supplemental Security Income/State Supplementary Payment recipients and California Work Opportunity and Responsibility to Kids families; (2) provided significant additional funding for affordable housing development, established a new homeownership program, and provided additional discretionary funding for homelessness services at the local level over multiple fiscal years; (3) provided larger ongoing base increases and funded higher enrollment growth at the universities; (4) provided larger augmentations for student financial aid grants; (5) accelerated the implementation of a developmental services rate study; (6) provided additional funding for health workforce development; and (7) deferred action on, but set aside funding for, a number of the Governor’s major health‑related budget proposals, most notably the hospital and nursing facility retention payments proposal.

Final Budget Package

The Legislature passed a final budget package on June 29, 2022 and a series of additional budget‑related bills in late August 2022. Figure 11 contains a list of the budget‑related legislation passed later in the legislative session.. The next section of this report describes the major features of the final budget package.

Figure 11

Budget‑Related Legislation Passed After July 1, 2022

|

Bill Number |

Chapter |

Subject |

|

Budget Bills and Amendments |

||

|

AB 179 |

249 |

Amendments to the 2022‑23 Budget Act |

|

Trailer Bills Passed After July 1, 2022 |

||

|

AB 151 |

250 |

State employee compensation |

|

AB 152 |

736 |

COVID‑19 relief: supplemental sick leave |

|

AB 156 |

569 |

State government |

|

AB 157 |

570 |

State government |

|

AB 158 |

737 |

Paycheck Protection Program |

|

AB 160 |

771 |

Public safety |

|

AB 185 |

571 |

Education |

|

AB 190 |

572 |

Higher education |

|

AB 204 |

738 |

Health |

|

AB 207 |

573 |

Human services |

|

AB 209 |

251 |

Energy and climate change |

|

AB 211 |

574 |

Public resources |

|

Note: This figure includes budget bills and trailer bills identified in Section 39.00 in the 2022‑23 Budget Act that were enacted into law after July 1, 2022. Ordered by bill number. |

||

Major Features of the 2022‑23 Spending Plan

The major General Fund and federal fund spending actions in the 2022‑23 budget package are briefly described in this section, mostly organized around the issue areas shown in Figure 5 in the first section of this report. We plan to discuss these and other actions in more detail in a series of forthcoming publications this fall.

K‑14 Education

Significant Increase in School and Community College Funding. The Proposition 98 minimum guarantee depends upon various formulas that adjust for several factors, including changes in state General Fund revenue. For 2021‑22, the guarantee is up $16.5 billion (17.6 percent) compared with the estimates made in June 2021 (Figure 12). This increase represents one of the largest upward revisions since the adoption of Proposition 98 and is due to higher General Fund revenue estimates. For 2022‑23, the guarantee increases by an additional $117 million (0.1 percent) relative to the revised 2021‑22 level.

Figure 12

Comparing June 2021 and June 2022 Proposition 98 Estimates

(In Millions)

|

2021‑22 |

2022‑23 |

||||||

|

June 2021 Enacted |

June 2022 Revised |

Change |

June 2022 Enacted |

Change From 2021‑22 Revised |

Change From 2021‑22 Enacted |

||

|

Minimum Guarantee |

|||||||

|

General Fund |

$66,374 |

$83,677 |

$17,302 |

$82,312 |

‑$1,364 |

$15,938 |

|

|

Local property tax |

27,365 |

26,560 |

‑805 |

28,042 |

1,482 |

677 |

|

|

Totals |

$93,739 |

$110,237 |

$16,498 |

$110,354 |

$117 |

$16,615 |

|

|

Funding by Segment |

|||||||

|

K‑12 schools |

$80,523 |

$93,997 |

$13,474 |

$95,524 |

$1,527 |

$15,001 |

|

|

Community colleges |

10,598 |

12,251 |

1,653 |

12,606 |

354 |

2,007 |

|

|

Reserve deposit |

2,617 |

3,988 |

1,371 |

2,224 |

‑1,764 |

‑393 |

|

Makes Required Reserve Deposit and Funds New Programs. When the minimum funding requirement is growing quickly, the Constitution requires the state to deposit some of the available funding into a statewide reserve account for schools and community colleges. Under the adopted budget plan, the state deposits a total of $9.5 billion into this account across the 2020‑21 through 2022‑23 period—an increase of $4.5 billion compared with the estimates made in June 2021. The budget allocates the remaining funds for significant one‑time and ongoing program increases. For schools, the largest ongoing augmentation is $7.9 billion to provide a 13 percent increase to the Local Control Funding Formula and provide greater fiscal stability to school districts experiencing declining attendance. The budget plan also includes $12.1 billion in one‑time funding for two K‑12 block grants—$7.9 billion focused on learning recovery and $3.6 billion intended for arts, music, and instructional materials. For community colleges, the largest augmentation is $1.1 billion ongoing for apportionment increases, consisting of a COLA as well as a base increase above the COLA. In addition, the budget plan includes $841 million one time for facilities maintenance and instructional equipment and $650 million one time for a COVID‑19 block grant.

Adjusts Guarantee Upwards for Expansion of Transitional Kindergarten. The June 2021 budget plan established a plan to expand eligibility for transitional kindergarten beginning in 2022‑23. Under the plan, all four‑year old children will be eligible by 2025‑26. (Previously, only children born between September 2 and December 2 were eligible.) The Legislature and Governor also agreed the state would cover the associated costs by adjusting the Proposition 98 formulas to increase the share of General Fund revenue allocated to schools. Consistent with this agreement, the budget plan includes an increase in the 2022‑23 guarantee of $614 million related to the first‑year costs of the expansion.

School Facilities Grants. The budget allocates $1.4 billion (non‑Proposition 98 General Fund) attributable to 2021‑22 for school facilities grants. Of this total, $1.3 billion is to cover the state share for new construction and modernization projects under the School Facilities Program. These funds supplement existing funds from Proposition 51, the state school bond approved by voters in 2016. (Funding from Proposition 51 will likely be exhausted in 2022‑23.) The remaining $100 million is for schools to construct or renovate State Preschool, transitional kindergarten, and full‑day kindergarten classrooms.

Resources and Environment

Energy Package. The spending plan includes a total of $7.9 billion across five years from the General Fund—including $1.2 billion through the California Emergency Relief Fund—for energy‑related activities. This includes $5.2 billion—$2.3 billion in 2021‑22 and $2.9 billion in 2022‑23—for activities such as actions to ensure there is adequate statewide electricity supply over the next few years, financial support to cover unpaid household energy bills that accrued during the pandemic, and incentives for long‑duration storage projects.

Drought Response and Resilience Package. The budget package includes $2.9 billion across three years from the General Fund—including roughly $1 billion through the California Emergency Relief Fund—to respond to current drought conditions, as well as for activities to prepare for future droughts. This includes $2.3 billion—$1.9 billion in 2021‑22 and about $400 million in 2022‑23—for activities such as actions to improve water conservation, drinking water supplies and projects, grants for repairs to community water systems, and steps to protect fish and wildlife from drought impacts. These funds add to $880 million provided for water‑related activities in 2022‑23, consistent with a multiyear agreement that was part of the 2021‑22 budget package.

Wildfire Resilience and Response. The spending plan provides resources to improve the state’s resilience to wildfires, as well as to augment the state’s capacity to respond when fires do occur. First, it includes a total of $900 million from the General Fund on a one‑time basis over three years—$80 million in 2021‑22, $320 million in 2022‑23, and $500 million in 2023‑24—for various departments to implement a package of proposals focused on wildfire prevention and improving landscape health. This funding is in addition to $200 million annually in continuously‑appropriated funding from the Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund (GGRF) for similar purposes. Second, the spending plan provides roughly $850 million in 2022‑23, of which about $500 million is ongoing—almost entirely from the General Fund—for various augmentations aimed at enhancing the state’s wildfire response. These augmentations mainly support additional personnel and equipment at the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection, but also provide wildfire response resources for the Governor’s Office of Emergency Services, California Military Department, and California Conservation Corps. Notably, the budget package also includes approval of a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) with Unit 8, which represents CalFire firefighters. As we discuss in our August analysis, this MOU could increase out‑year wildfire response costs significantly.

Zero‑Emissions Vehicles (ZEV) Package. The budget package provides a total of $6.1 billion over five years for ZEV programs. (This amount is in addition to $3.9 billion included in last year’s budget.) This includes $3.1 billion from various funds across 2021‑22 and 2022‑23, such as $1.5 billion from Proposition 98 General Fund for zero‑emission school buses, $804 million from the General Fund for various activities including ZEV fueling infrastructure grants, $600 million from GGRF for heavy‑duty vehicle incentives, and $77 million in federal funds for ZEV fueling infrastructure.

Climate Change Response. In addition to the aforementioned drought and wildfire packages, the spending plan contains funding targeted to address other climate change impacts. This includes additional General Fund generally consistent with the 2021‑22 agreement to address extreme heat ($150 million in both 2022‑23 and 2023‑24) and nature‑based climate solutions ($594 million in 2022‑23 and $428 million in 2023‑24). The budget package also provides significant augmentations to address sea‑level rise, including roughly $600 million in 2022‑23 and $650 million committed for 2023‑24. (These totals include some funding incorporated within the nature‑based solutions package.)

Transportation

Transportation Infrastructure Package. The budget package includes $9.5 billion across four years from the General Fund to support transportation infrastructure. This includes $7.7 billion—$3.7 billion in 2021‑22 and $2 billion in both 2023‑24 and 2024‑25—to fund transit and rail projects throughout the state. The package also includes (1) $1.8 billion in 2021‑22 to support active transportation, climate adaptation, and grade separation projects, and (2) $100 million in 2023‑24 to augment a local litter abatement and beautification grant program initiated in 2021‑22.

Supply Chain Resilience Package. The budget includes $1.4 billion from the General Fund over four years for a package of initiatives intended to support ports and goods movement infrastructure, workforce development, and operational efficiency at the state’s ports Specifically, the package consists of (1) $1.2 billion for the California State Transportation Agency to fund port, freight, and goods movement infrastructure; (2) $110 million for the California Workforce Development Board to establish a goods movement workforce training campus; (3) $40 million for the Department of Motor Vehicles to increase capacity to issue commercial driver’s licenses; and (4) $30 million for the Governor’s Office of Business and Economic Development to fund operational and process improvements at ports.

High‑Speed Rail Project. The budget package appropriates essentially all of the remaining unappropriated Proposition 1A bond (2008) funds—$4.2 billion—for the high‑speed rail project in 2021‑22. The budget package also includes associated budget trailer legislation that establishes a new independent Office of the Inspector General for the High‑Speed Rail Authority and prioritizes funding the Merced‑to‑Bakersfield segment of the project, among other provisions.

Health and Developmental Services

Retention Payments for Workers in Certain Health Care Facilities. The budget package includes roughly $1.1 billion General Fund (transferred into the California Emergency Relief Fund) in 2021‑22 to provide one‑time retention payments to eligible workers in certain health care facilities, including hospitals and skilled nursing facilities. Eligible workers could receive up to $1,500 from the state. A similar payment is being included in labor bargaining agreements for state employees, paid using a mix of General Fund and other funds. In addition to the $1.1 billion amount, the spending plan includes $70 million General Fund for a separate program to provide retention payments to eligible workers in health care clinics.

Behavioral Health. The spending plan reflects a number of major investments in behavioral health. These investments include roughly $2 billion in General Fund expenditures in 2022‑23 approved last year as part of the multiyear Children and Youth Behavioral Health Initiative. This initiative funds a variety of programs administered by multiple state departments intended to transform behavioral health service delivery for children and youth under age 25. In addition, the spending plan includes $1 billion General Fund in 2022‑23 ($1.5 billion General Fund over two years) to establish a state‑level Behavioral Health Bridge Housing program, which will support the creation of immediate, clinically enhanced housing settings for people experiencing homelessness with serious behavioral health conditions.

Late in session, the Legislature passed the Community Assistance, Recovery and Empowerment (CARE) Act. The CARE Act creates an alternative judicial process to connect those with severe mental illness to behavioral health services and supports. The spending plan provides $88.3 million General Fund (of which $57 million is for direct assistance to counties) to the Department of Health Care Services, the California Health and Human Services Agency, and the Judicial Branch for the implementation of the CARE Act in 2022‑23. CARE Act implementation will begin in seven “Cohort I” counties by October 1, 2023, with the remaining counties to begin implementation no later than December 1, 2024.

Medi‑Cal Coverage Expansion to Remaining Undocumented Populations. Historically, undocumented residents were only eligible for limited Medi‑Cal coverage. In recent years, the state has taken steps to expand eligibility for comprehensive Medi‑Cal coverage to undocumented residents under the age of 26 as well as those over the age of 49. The budget package expands eligibility for comprehensive Medi‑Cal coverage to otherwise‑eligible undocumented residents between the ages of 26 and 49 beginning no later than January 1, 2024. While there are no costs in 2022‑23, the expansion is expected to result in increased spending of $2.1 billion General Fund at full implementation.

Developmental Services Rate Reform Acceleration. The 2021‑22 budget included funding to begin implementation of service provider rate reform, with funding for rate increases and quality incentives ramping up to $1.2 billion General Fund in 2025‑26 and ongoing. The 2022‑23 budget spending plan includes one‑time General Fund in 2022‑23 ($159.1 million), 2023‑24 ($34.1 million), and 2024‑25 ($534.1 million) to accelerate the time line, reaching full implementation by 2024‑25, one year ahead of the original schedule.

Housing and Homelessness

Significant Funding Largely Continues Existing Efforts. In addition to the $9 billion for housing and homelessness programs provided in the budget last year, the 2022‑23 budget authorizes an additional $4.8 billion General Fund over three years to nearly 20 major housing and homelessness programs within the Business, Consumer Services, and Housing Agency and the Housing and Community Development Department. The vast majority of funding is one time or temporary. However, the budget does provide $34 million in ongoing funding beginning in 2023‑24 for housing assistance for foster youth and former foster youth. Most of the funding—$2.9 billion General Fund—is primarily for housing‑related proposals, while $1.9 billion General Fund is allocated primarily towards homelessness‑related programs.

Some of the major uses of housing and homelessness funding in the budget would support encampment resolutions; provide flexible aid to local governments to help address homelessness in their communities; fund affordable housing development; and establish a new homeownership program. The budget also provides funding that could be used to help address homelessness and/or housing affordability in other program areas, including the health, courts, and higher education areas.

Higher Education

Base Funding Increases for Universities’ Core Operations. The spending plan provides the California State University (CSU) and the University of California (UC) with 5 percent increases to their base General Fund support. These base increases equate to a $211 million augmentation for CSU and a $201 million augmentation for UC. The universities have discretion over how to spend their base augmentations. They likely will use the funds primarily to cover salary and benefit cost increases. (In addition to CSU’s unrestricted base increase, the budget provides CSU with $103 million General Fund to cover certain pension and retiree health benefit cost increases.) The 5 percent base increases are consistent with the Governor’s January proposal for the universities (also reflected in the Governor’s university “compacts”). The June legislative package had contained higher base increases for the universities. (We treat funding increases for core operations, including pensions and other employee benefits, as maintaining current service levels rather than discretionary spending.)

Additional Funding Increases for Undergraduate Enrollment Growth. Largely consistent with 2021‑22 Budget Act provisions, the 2022‑23 spending plan provides $81 million to CSU and $99 million to UC for resident undergraduate enrollment growth. At CSU, enrollment is expected to grow by 9,434 full‑time equivalent (FTE) students from 2021‑21 to 2022‑23 (leaving CSU still approximately 3,000 FTE students below its peak enrollment level in 2020‑21). At UC, the budget funds growth of 7,132 FTE students—consisting of 1,500 FTE students that were not funded in previous budgets, 902 FTE students resulting from replacing nonresident with resident slots, and an additional 4,730 FTE new students. UC has through 2023‑24 to enroll these additional 4,730 FTE students. The budget also indicates that UC is to grow by a further 1 percent in 2023‑24, with this additional growth funded from an unrestricted General Fund base augmentation to be provided that year. The budget package also reflects UC’s continued implementation of its statutory nonresident replacement plan, with an additional 902 nonresident slots replaced with resident slots in 2023‑24. The budget package sets no 2023‑24 enrollment expectation for CSU.

Appendix

Note: In the online version of this report, we include a series of Appendix tables that have detailed information on the discretionary choices in the 2022‑23 Budget Act.