The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) released its December 2014 U.S. consumer price index (CPI) data on Friday, January 16, as well as new CPI data for large metropolitan areas such as the region around Los Angeles and the Bay Area.

The CPI is a principal measure of inflation in the economy, and the bureau's CPI indices report data on changes in prices paid by urban consumers for representative "baskets" of goods and services.

Inflation in U.S. Is Very Low

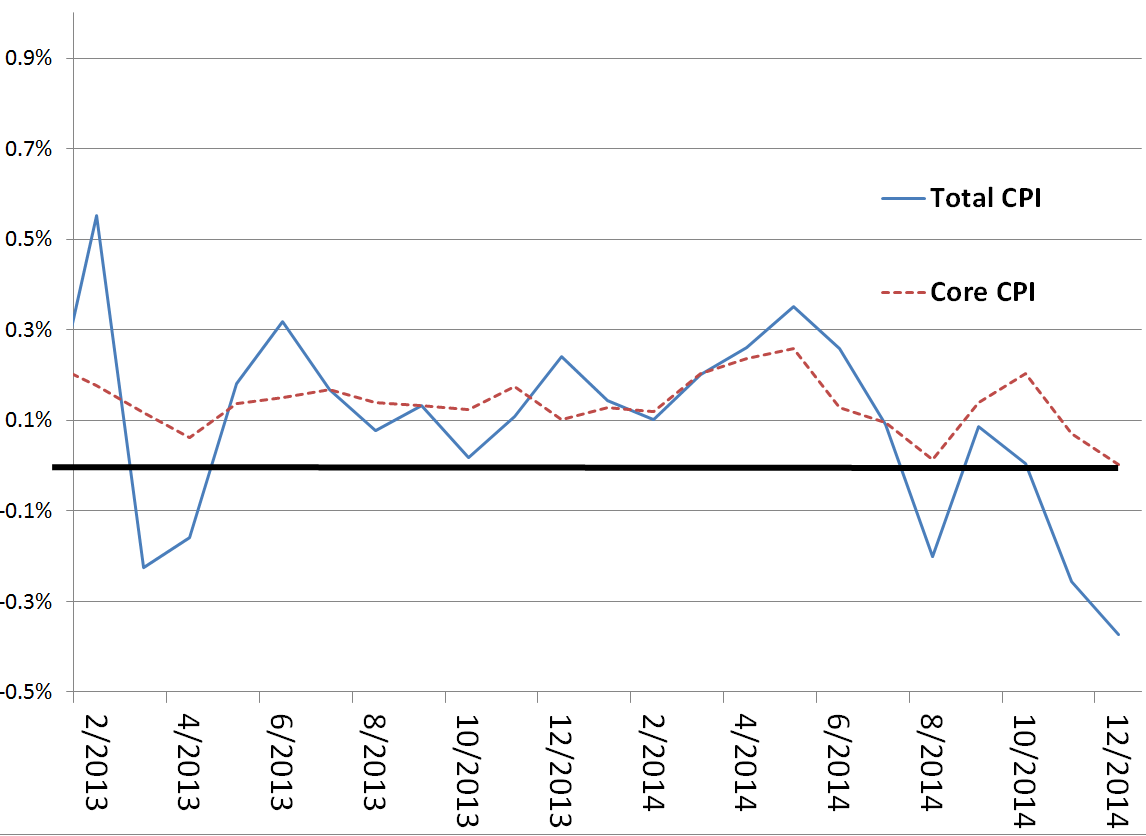

Total CPI Down in December. The overall (total) CPI measure, the CPI for all urban consumers, declined 0.4 percent in December on a seasonally-adjusted basis. Total CPI previously fell in August and November. (The figure below displays the month-by-month changes in total CPI and "core" CPI, described further below, since the beginning of 2013.) For 2014 as a whole, today's data indicates that total CPI rose 0.8 percent after a 1.5 percent increase in 2013. According to BLS, CPI growth since last year represents "the second smallest December-to-December increase in the last 50 years, trailing only the 0.1 percent increase in 2008." Over the last 10 years, the average increase was 2.1 percent.

Data Shows Energy Prices Drove Fall in Total CPI. While total CPI, considering consumer prices of all goods, fell in December, economists often focus instead on "core" measures of inflation. One such measure is the core CPI that includes all items except food and energy. (Food and energy prices are especially volatile.) In December, BLS reports that core CPI was unchanged, making last month only the second time since 2010 that this price index held flat. BLS's food price index climbed slightly in December. Accordingly, the fall in energy prices drove December's price declines in the total CPI, as BLS's energy price index fell 4.7 percent, its sixth monthly decline in a row.

While the data tells us that energy prices were key to the December total CPI decline, these were not the only prices to fall. BLS reports declines in some other price indices including apparel, airline fares, cars, and household furnishings. Prices for homes and lodging continued to rise, and the price index for medical care posted its largest increase, 0.5 percent, in over a year.

Further Inflation Drops Likely. As we discussed on the blog a few days ago, much of the recent drop in oil and gasoline prices occurred during December. The full effect of these price declines should show up in the January 2015 CPI data, scheduled for release by BLS on February 26. It is possible the January decline in inflation could be much larger than the December decline. It is possible that the total CPI, the overall measure of prices in the economy, will be lower at that time than one year before.

Risks, Benefits of Very Low Inflation

Lower Price Growth Creates Some Benefits in Near Term. For consumers and businesses, very low levels of price growth, such as those we are seeing now, have certain benefits in the short term. We discussed some of the near-term benefits of lower oil prices for the California economy, for example, in our Overview of the Governor's Budget earlier this week. Low gas prices can help consumers spend more, and this consumption boost can increase near-term growth in economic activity.

However, Deflation or Very Low Inflation Can Be Risky. While there are certain benefits of very low inflation in the near term, such low rates of price growth pose significant risks to the economy if they persist for long. This is one reason why the Federal Reserve targets 2 percent inflation growth according to a specific inflation index. According to the Federal Reserve, this rate of inflation "is most consistent over the longer run" with the agency's statutory mandate to aim for price stability and maximum employment. A lower inflation rate over the longer run, the Federal Reserve reasons, "would be associated with an elevated probability of falling into deflation, which means prices and perhaps wages…are falling." Such deflation is a "phenomenon associated with very weak economic conditions." Deflation can depress borrowing and spending that are crucial to economic growth, as well as worsen repayment burdens for borrowers. When consumers expect that prices will fall further, they may delay purchases, thereby reducing demand for goods and services. The Federal Reserve concludes that "having at least a small level of inflation makes it less likely that the economy will experience harmful deflation if economic conditions weaken."

Federal Reserve Assessment. At the December 2014 meeting of the Federal Open Markets Committee (FOMC), Federal Reserve staff noted that while consumer price inflation was running below the FOMC's longer-run objective of 2 percent, measures of the markets' "longer-run inflation expectations remained stable" according to a variety of surveys. Federal Reserve staff indicated that risks to their forecast for real gross domestic product growth and inflation were "tilted a little to the downside," since neither federal fiscal policy nor monetary policy—marked currently by near-zero target interest rates—"were well positioned to help the economy withstand adverse shocks." FOMC members "generally anticipated that inflation was likely to decline further in the near term" due to falling oil prices and the strengthening dollar. Most FOMC members viewed these influences as temporary, however. Some FOMC members also noted that if the U.S. unemployment rate continued to decline quickly, "wage and price inflation could rise more than generally anticipated." The FOMC's meeting's final public statement in December concluded that the committee "expects inflation to rise gradually toward 2 percent as the labor market improves further and the transitory effects of lower energy prices and other factors dissipate." Many market observers have been expecting the Federal Reserve to increase its near-zero interest rate targets beginning sometime in 2015. The December statement noted that if progress toward the Federal Reserve's employment and inflation objectives "proves slower than expected, then increases in [the FOMC's interest rate] target range are likely to occur later than currently anticipated." Those rate increases, when they occur, could affect both bond and stock prices, as well as the volatility of global markets, and thereby have a direct effect on California's state revenues (driven as they are by fluctuations in stock prices).

International Deflation Fears. The possibility of sustained deflation in various parts of the global economy has been weighing on markets recently. Many economic policy makers recall Japan's debilitating experience with deflation in the 1990s. As we discussed in this week's Overview of the Governor's Budget, the international economic situation could affect California's economy too, in both positive and negative ways.

Inflation in California

BLS local inflation data shows that the Los Angeles region has been mirroring national inflation trends, while Bay Area prices have been increasing somewhat more rapidly over the past year. The local CPI data discussed below is not seasonally adjusted, unlike the national data described above. Because the local data is not seasonally adjusted, seasonal influences may affect month-to-month changes. BLS reports local data on different schedules, with smaller urban areas reported less frequently than the largest areas like Los Angeles.

Los Angeles Region. In December, total CPI in the Los Angeles-Riverside-Orange County region fell 0.5 percent. Over the last 12 months, total CPI increased 0.7 percent in this region, which includes Los Angeles, Orange, Riverside, San Bernardino, and Ventura Counties. Energy prices in the region fell 12.9 percent over the last 12 months, largely the result of gas price declines. Excluding food and energy, the local measure of core CPI grew 1.5 percent since December 2013. Shelter costs, mainly those for rents and homeownership, grew 3 percent over the past year, BLS calculated.

Bay Area. For the two months ending in December, total CPI in the San Francisco-Oakland-San Jose region fell 0.9 percent, largely attributable to lower gasoline and apparel prices according to BLS. Over the last 12 months, total CPI increased 2.7 percent in this region, which includes Alameda, Contra Costa, Marin, Napa, San Francisco, San Mateo, San Benito, Santa Clara, Santa Cruz, Sonoma, and Solano Counties. Energy prices in the region fell 11.8 percent over the last 12 months. Excluding food and energy, the local measure of core CPI grew 3.6 percent since December 2013. Shelter costs in the Bay Area grew 5.4 percent over the last year, BLS calculated.