November 14, 2012

The 2013-14 Budget: California’s Fiscal Outlook

Table of Contents

Executive Summary

Budget Situation Has Improved Sharply. The state’s economic recovery, prior budget cuts, and the additional, temporary taxes provided by Proposition 30 have combined to bring California to a promising moment: the possible end of a decade of acute state budget challenges. Our economic and budgetary forecast indicates that California’s leaders face a dramatically smaller budget problem in 2013–14 compared to recent years. Furthermore, assuming steady economic growth and restraint in augmenting current program funding levels, there is a strong possibility of multibillion–dollar operating surpluses within a few years.

The Budget Forecast

Projected $1.9 Billion Budget Problem to Be Addressed by June 2013. The 2012–13 budget assumed a year–end reserve of $948 million. Our forecast now projects the General Fund ending 2012–13 with a $943 million deficit, due to the net impact of (1) $625 million of lower revenues in 2011–12 and 2012–13 combined, (2) $2.7 billion in higher expenditures (including $1.8 billion in lower–than–budgeted savings related to the dissolution of redevelopment agencies), and (3) an assumed $1.4 billion positive adjustment in the 2010–11 ending budgetary fund balance. We also expect that the state faces a $936 million operating deficit under current policies in 2013–14. These estimates mean that the new Legislature and the Governor will need to address a $1.9 billion budget problem in order to pass a balanced budget by June 2013 for the next fiscal year.

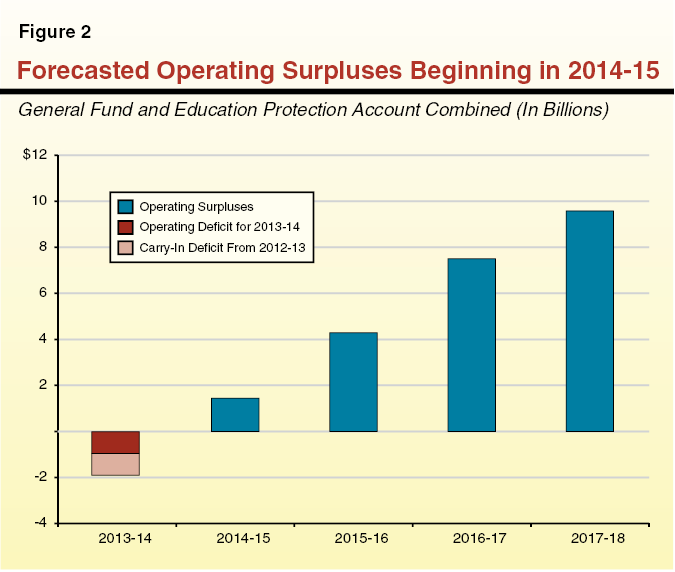

Surpluses Projected Over the Next Few Years. Based on current law and our economic forecast, expenditures are projected to grow less rapidly than revenues. Beyond 2013–14, we therefore project growing operating surpluses through 2017–18—the end of our forecast period. Our projections show that there could be an over $1 billion operating surplus in 2014–15, growing thereafter to an over $9 billion surplus in 2017–18. This outlook differs dramatically from the severe operating deficits we have forecast in November Fiscal Outlook reports over the past decade.

LAO Comments

Despite Positive Outlook, Caution Is Appropriate. Our multiyear budget forecast depends on a number of key economic, policy, and budgetary assumptions. For example, we assume steady growth in the economy and stock prices. We also assume—as the state’s recent economic forecasts have—that federal officials take actions to avoid the near–term economic problems associated with the so–called “fiscal cliff.” Consistent with state law, our forecast omits cost–of–living adjustments for most state departments, the courts, universities, and state employees. The forecast also assumes no annual transfers into a state reserve account provided by Proposition 58 (2004). Changes in these assumptions could dramatically lower—or even eliminate—our projected out–year operating surpluses.

Considering Future Budget Surpluses. If, however, a steady economic recovery continues and the Legislature and the Governor keep a tight rein on state spending in the next couple of years, there is a strong likelihood that the state will have budgetary surpluses in subsequent years. The state has many choices for what to do with these surpluses. We advise the state’s leaders to begin building the reserve envisioned by Proposition 58 (2004) as soon as possible. Beyond building a reserve, the state must develop strategies to address outstanding retirement liabilities—particularly for the teachers’ retirement system—and other liabilities. The state will also be able to selectively restore recent program cuts—particularly in Proposition 98 programs (based on steady projected growth in the minimum guarantee).

Chapter 1

The Budget Outlook

This publication summarizes our office’s independent projections for California’s economy, tax revenues, and expenditures from the state General Fund, as well as the Education Protection Account (EPA) created by Proposition 30. Our forecast is based on current state law and policies, as discussed in the nearby box.

The Budget Forecast

Projected $1.9 Billion Budget Problem Must Be Addressed by June 2013. The 2012–13 Budget Act assumed a year–end reserve of $948 million. As shown in Figure 1, assuming that no corrective budgetary actions are taken, we project that the state will close 2012–13 with a $943 million deficit. As discussed later, lower–than–expected savings related to the dissolution of redevelopment agencies (RDAs) and other budgetary erosions contribute to this shortfall. We also expect that the state faces an operating deficit in 2013–14—the difference between current–law revenues and expenditures in that fiscal year—of $936 million. These estimates mean that the new Legislature and the Governor will need to address a $1.9 billion budget problem in order to pass a balanced budget in June 2013 for the next fiscal year. This is a dramatically smaller budget problem than the state has faced in recent years.

Figure 1

LAO Projections of General Fund Condition

If No Corrective Actions Are Taken

(In Millions, Includes Education Protection Account)

|

|

2011–12

|

2012–13

|

2013–14

|

|

Prior–year fund balances

|

–$1,285

|

–$1,885

|

–$224

|

|

Revenues and transfers

|

86,482

|

95,610

|

96,743

|

|

Expenditures

|

87,082

|

93,950

|

97,679

|

|

Ending fund balance

|

–$1,885

|

–$224

|

–$1,160

|

|

Encumbrances

|

719

|

719

|

719

|

|

Reservea

|

–$2,604

|

–$943

|

–$1,879

|

Basis for Our Projections

This forecast is not intended to predict budgetary decisions by the Legislature and the Governor in the coming years. Instead, it is our best estimate of revenues and expenditures if current law and current policies are left in place through 2017–18. Specifically, our estimates assume current law and policies, including those in the State Constitution (such as the Proposition 98 minimum guarantee for school funding), statutory requirements, and current tax policy. Our forecast projects future changes in caseload and accounts for relevant changes in federal law and various other factors.

Effects of November 2012 Voter Initiatives Included. Our forecast reflects the approval by voters of Propositions 30, 35, 36, 39, and 40 at the November 6, 2012 statewide election.

COLAs and Inflation Adjustments Generally Omitted. Consistent with the state laws adopted in 2009 that eliminated automatic cost–of–living adjustments (COLAs) and price increases for most state programs, our forecast generally omits such inflation–related cost increases. This means, for example, that budgets for the universities and courts remain fairly flat throughout the forecast period and that state employee salaries do not grow except for already–negotiated pay increases. We include inflation–related cost increases when they are required under federal or state law, as is common in health and social services programs.

Uncertainty Surrounding Federal Fiscal Policy. There is great uncertainty surrounding the federal “fiscal cliff,” the combination of tax increases and spending cuts set to take place under current federal law in 2013. These policies, if left unchanged, would have a significant effect on the economy and could result in economic conditions differing materially from our forecast. As discussed in Chapter 2, our forecast makes a number of assumptions regarding the federal fiscal cliff and its effect on the California economy. In general, we assume that federal policy makers take actions to avoid virtually all major near–term effects of the fiscal cliff.

Recent Accounting Issues That Affect the State Budget Process

This box discusses two accounting issues that have risen in prominence recently: the state’s revenue accrual policies and accounting practices for the state’s over 500 special funds.

The State’s Revenue Accrual Policies. The state commonly adjusts the prior year’s ending fund balance as part of the budget process—to reflect updated information concerning spending or revenue accrual estimates. The $1.4 billion positive fund balance adjustment (preliminary and subject to change) recently reported to us by the Department of Finance is related to updated revenue accruals. In our budgetary process, accruals are used to allocate tax revenues—generally paid on a calendar year basis—to a particular fiscal year. The general idea is to assign the revenue to the fiscal year in which the economic activity producing the revenue occurred. In recent years, the state has altered its accrual policies. Some of the changes have a theoretical basis in accounting principles, but their effect has been to move more revenue collected in one fiscal year to a prior fiscal year (thereby helping to balance the state budget). The changes also affect calculation of the Proposition 98 minimum guarantee. (We discussed revenue accruals in our January 2011 publication, The 2011–12 Budget: The Administration’s Revenue Accrual Approach.)

Section 35.50 of the 2012–13 Budget Act institutes a new accrual method for the tax revenues generated by Propositions 30 and 39. A portion of final income tax payments paid in, say, April of one year will be accrued all the way back to the prior fiscal year (which ended ten months in the past). One effect of the change is that we will no longer have a good idea of a fiscal year’s revenues until one or two years after that fiscal year’s conclusion. Because the volatile capital gains–related revenues from Proposition 30 are the subject of the accrual changes, the late adjustments to revenues could total billions of dollars—much more than in the past. As a result, the chances of large forecast errors by us and the administration will increase.

We are now convinced that the problems that this new accrual method will introduce to the budgetary process outweigh its benefits. We recommend that the Legislature direct the administration to develop a simpler, logical budgetary revenue accrual system by 2015. Alternatively, to help ensure the accuracy of our forecasts and improve transparency, we recommend that the Legislature require the administration to document accruals regularly online.

Special Fund Accounting Practices. In response to this year’s Department of Parks and Recreation accounting issues, the Legislature passed Chapter 343, Statutes of 2012 (AB 1487, Committee on Budget), to ensure that special fund information was presented in the Governor’s budget on the same basis as that used in the Controller’s budgetary accounting reports. We expect that the 2013–14 Governor’s Budget will include updated information on special fund balances in response to these requirements. Legislative committees will want to scrutinize the condition of special funds with significant discrepancies compared to prior administration reports. Decisions about when special fund loans are repaid by the General Fund could materially affect the condition of special funds in the coming years. When considering whether or not to extend repayment dates of existing loans or authorize new loans, the Legislature will want to consider: (1) whether special fund programs are meeting legislative expectations; 2) whether a General Fund loan repayment would facilitate one–time or permanent fee decreases, either immediately or over time; (3) whether existing priorities for special fund programs should be changed; and (4) the relative prioritization of General Fund and special fund activities.

Projected 2012–13 Deficit of $943 Million

Higher Spending and Lower Revenues Contribute to Deficit. The $1.9 billion deterioration in the 2012–13 budget situation is due to the impact of (1) $625 million of lower revenues in 2011–12 and 2012–13 combined, (2) $2.7 billion in higher expenditures, and (3) an assumed $1.4 billion positive adjustment in the 2010–11 ending budgetary fund balance. (The box on page 3 discusses the subject of revenue accruals—reportedly responsible for the fund balance adjustment—and other accounting issues related to the state budget.)

Revenue Estimates Down Somewhat From Budget Act Assumptions. The 2012–13 budget package assumed that Proposition 30 would pass—thereby temporarily levying additional personal income taxes (PITs) and sales and use taxes and depositing them to a new state fund, the EPA. Our forecast includes updated estimates concerning Proposition 30 tax receipts and the rest of the state’s revenues. It also adds increased corporation tax (CT) revenues based on voters’ approval of Proposition 39. For the General Fund and EPA combined, we currently project that 2011–12 revenues will be $348 million less than assumed in the 2012–13 budget package and that 2012–13 revenues will be $277 million less than assumed, for a total of $625 million less in revenues for these two fiscal years combined. The largest differences in this regard relate to the PIT and CT, as follows:

- Facebook Offsets Other Projected PIT Gains.

Our updated estimate of revenues related to the initial public offering (IPO) of stock by Facebook, Inc., is lower than that assumed in the budget package—by $626 million spread across 2011–12 and 2012–13. On the other hand, our forecast of non–IPO PIT revenues is higher across these two fiscal years by $473 million. In total, PIT revenues in 2011–12 and 2012–13 are forecast to be $153 million below budget act assumptions. (Due to the state’s new revenue accrual policies related to Proposition 30, we note that the books will not be closed on 2011–12 revenues until at least a year from now.)

- Proposition 39 Revenues Offset Lower CT Estimates.

Estimated CT revenues in 2011–12 were $605 million below the assumption in the budget act. In keeping with recent, very weak collection trends, we also forecast that CT revenues under prior tax law will be about $403 million lower than the budget act assumption in 2012–13. These declines, however, will be partially offset by the passage of Proposition 39, which changes the method by which some multistate businesses calculate their taxable income. We estimate that Proposition 39 will increase CT revenues by about $450 million in 2012–13. In total, therefore, our forecast of CT revenues in 2011–12 and 2012–13 combined is $558 million below the amount assumed in the 2012–13 budget act.

Significant 2012–13 Budget Actions at Risk.

Our forecast projects $2.7 billion in higher expenditures will contribute to a year–end deficit in 2012–13. These include budgetary erosions associated with several actions adopted in the 2012–13 budget package, including the following:

- RDA Savings Will Be Much Less. As described further in Chapter 3, the budget package assumed about $3.2 billion in General Fund savings related to the dissolution of RDAs. We estimate, however, that the savings will total about $1.8 billion less than assumed in the budget.

- $400 Million of Cap–and–Trade General Fund Savings Unlikely to Materialize. The 2012–13 budget included savings associated with the state’s cap–and–trade program. Specifically, the budget package assumed that $500 million in revenues generated by the program’s auctions would offset costs traditionally supported by the General Fund. Consistent with our prior estimates, our forecast projects that only $100 million of such costs could be offset by the revenues, resulting in a $400 million budgetary erosion.

- Healthy Families Program (HFP) Costs. The 2012–13 budget package included a $183 million reduction to HFP. As explained in Chapter 3, our forecast assumes the reduction will not be put in place because it would violate a maintenance–of–effort requirement under the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, the federal health care reform law.

- Wildfire–Related Costs. The 2012–13 Budget Act included $92.8 million in General Fund support for emergency fire suppression activities. Due to heavy fire activity during the early part of 2012–13, CalFire has requested an additional $118 million in funding. While the federal government or local fire agencies will eventually reimburse the state for some of this funding, our forecast treats the entire amount as an increased cost because the amount of future reimbursement is unknown.

Relatively Small Budget Problem Forecasted for 2013–14

Many Factors Contribute to the 2013–14 Operating Deficit. The combination of recent spending reductions and temporary tax increases—plus improvement in the economy—has virtually eliminated the state’s “structural deficit.” Accordingly, we estimate that the state is poised to record a substantial operating surplus in 2012–13—which was necessary to eliminate most of the carry–in deficit related to prior years’ budgetary problems. In 2013–14, however, our forecast projects a $936 million operating deficit, assuming current law policies.

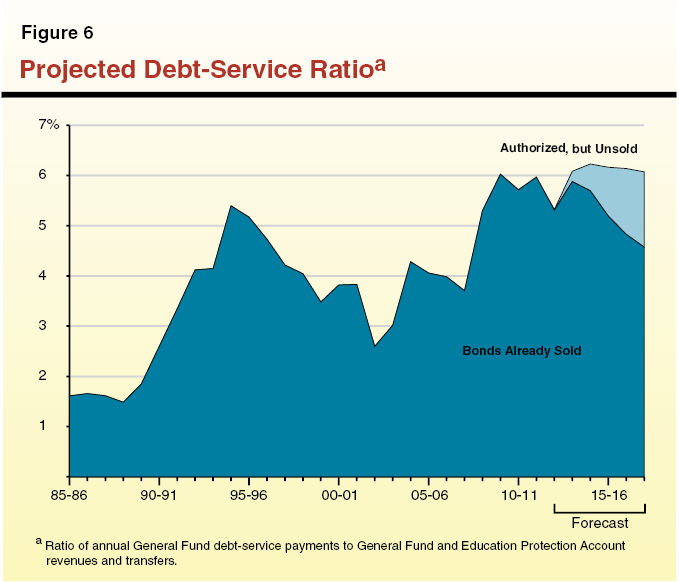

Many factors contribute to the small operating deficit we forecast in 2013–14. General Fund Proposition 98 payments, for example, grow by $1.8 billion. Also, actions to achieve savings in employee compensation—including furloughs and the Personal Leave Program—expire in June 2013, consistent with current labor agreements. Combined with scheduled pay increases and higher premium costs for state employees’ health care benefits, we project that employee compensation costs will increase by more than $750 million in 2013–14. We also project that General Fund debt–service costs related to infrastructure bonds will grow by $759 million in 2013–14. (These debt–service costs go up in 2013–14 primarily because the state structured its infrastructure bonds so that payments were lower in 2012–13. The state did this to accommodate the required, one–time repayment this year of a $2 billion loan from local governments, which the Legislature authorized in 2009 with its suspension of Proposition 1A [2004].)

The expiration of various one–time actions in the 2012–13 budget also contribute to the operating deficit, including about $419 million in higher expenditures for the judicial branch. We also assume that the state repays about $1.1 billion of loans to special funds, consistent with previous loan repayment schedules provided by the administration. (We note that the administration has substantial flexibility, in many cases, to delay such planned repayments.) Revenue growth of about $1.1 billion over 2012–13 partially offsets $3.7 billion in increased expenditures in our forecast.

Operating Surpluses Projected Over the Next Few Years

State “In the Black” After Years of Major Operating Deficits. Under current law, General Fund and EPA expenditures are projected to grow less rapidly than revenues, given our current economic forecast. Beyond 2013–14, we therefore project growing operating surpluses throughout the forecast period. As indicated in Figure 2, our forecast shows that there could be an over $1 billion operating surplus in 2014–15, growing thereafter to an over $9 billion surplus in 2017–18. A contributing factor to the surpluses beginning in 2016–17 is the end of the “triple flip,” the financing mechanism used for the 2004 economic recovery bonds (ERBs). (Specifically, the General Fund benefits—to the tune of about $1.6 billion per year—once the ERBs are retired, which will result in higher local funding for school districts and a related decrease in state funding requirements for schools.) This outlook of significant operating surpluses differs dramatically from the severe operating deficits we have forecast in November Fiscal Outlook documents over the past decade.

LAO Comments

Despite Positive Outlook,Caution Is Appropriate

Several Assumptions Key to Achieving Future Surpluses. Our multiyear budget forecast depends on a number of economic, policy, and budgetary assumptions that, if changed, could result in dramatically different outcomes. As discussed below, a variety of alternate scenarios would result in much smaller future operating surpluses or possibly operating deficits.

Revenue Forecast Assumes Steady Growth in the Economy and Stock Prices. Our forecast assumes steady economic growth, fueled in particular by recent encouraging data about the state’s housing market and income trends. In one alternative scenario we considered—assuming the economy underperforms and state revenues grow one–third slower than forecasted—80 percent of the surplus shown in Figure 2 for 2017–18 would be eliminated, and prior fiscal years would be much more likely to have an operating deficit. Our forecast also assumes steady growth in the stock market, which results in taxable capital gains. As we have pointed out many times over the years, these gains are notoriously volatile and hard to predict. They are a key reason why tax revenue forecasts can easily be a few billion dollars lower (or higher) than projected by us or the administration in any given fiscal year.

Federal Fiscal Policy Poses Risk to Revenue Forecast. As discussed in Chapter 2, the federal fiscal cliff poses a significant risk to our economic and revenue forecast. Specifically, if the Congress and the President are unable to resolve the fiscal cliff, the economy could enter recession beginning in 2013. We examined one possible recession scenario in which state revenues were about $11 billion lower than in our forecast for 2012–13 and 2013–14 combined. This scenario obviously would also delay any potential future operating surpluses.

Forecast Assumes No Transfers to the BSA. Proposition 58 (2004) generally requires 3 percent of estimated General Fund revenues to be transferred each year to the Budget Stabilization Account (BSA), the state’s rainy day fund. The state has made such transfers in the past, but the Governor has suspended the requirement annually since 2008–09 due to the state’s persistent budget problems. Our forecast assumes that no transfer will be made during the forecast period. As shown in Figure 3, however, a transfer of 3 percent of General Fund revenues to the BSA beginning in 2015–16 would reduce the operating surpluses by over $3 billion per year.

Figure 3

Alternate Forecasts of General Fund Operating Surpluses

(In Millions, Includes Education Protection Account)

|

|

2015–16

|

2016–17

|

2017–18

|

|

Budget Forecast

|

|

|

|

|

Revenues and transfers

|

$111,017

|

$116,461

|

$121,627

|

|

Expenditures

|

106,728

|

108,962

|

112,047

|

|

Operating Surplus

|

$4,289

|

$7,499

|

$9,580

|

|

Alternate Scenarios

|

|

|

|

|

Transfer 3 percent of General Fund revenues to BSAa

|

–$3,331

|

–$3,494

|

–$3,649

|

|

Grow state operations and judiciary budget by inflation

|

–1,189

|

–1,624

|

–2,140

|

|

Subtotals

|

–$4,520

|

–$5,118

|

–$5,789

|

|

Alternate Scenario Operating Deficit/Surplus

|

–$231

|

$2,381

|

$3,791

|

Forecast Assumes No COLAs or Inflation Adjustments. Consistent with state law and recent state policy, our forecast includes no cost–of–living adjustments (COLAs) or price increases over the forecast period, except when required under federal or state law. As shown in Figure 3, if we included COLAs and price increases for state operations (including the universities and the judicial branch) each year of the forecast, operating surpluses would be around $2.1 billion lower by 2017–18.

Forecast Does Not Account for Repayment of Many Obligations. Our forecast assumes that the state initiates no additional loans from special funds to the General Fund (except those already envisioned in the 2012–13 budget plan), and that these loans are repaid when scheduled or otherwise required—generally consistent with recent repayment schedules provided by the administration (and, in some cases, with repayment deadlines included in prior budget acts). As a result, in our forecast, the $4.3 billion loan balance currently owed to special funds by the General Fund is reduced to $3.1 billion by the end of 2013–14 and $1.2 billion by the end of our forecast period in 2017–18. The Governor, however, has stated his preference to pay down this and other elements of the so–called “wall of debt” within a few years. If the Legislature and the Governor seek to repay these obligations, surpluses could be lower in some years.

Revenue Volatility and Maintenance Factor. As discussed in our May 2012 report, Proposition 98 Maintenance Factor: An Analysis of the Governor’s Treatment, the maintenance factor approach used in building the 2012–13 budget can ratchet up Proposition 98 spending in certain situations. This ratcheting effect is most likely to occur in years with significant year–to–year increases in General Fund revenues. Because Proposition 98 appropriations in one year typically are used to calculate the minimum guarantee in the next year, a significant increase in the Proposition 98 minimum guarantee for one year also would likely increase the state’s obligations in future years. Although such ratcheting does not occur in our current forecast, this situation is possible over the forecast period, particularly given the inherent volatility of PIT revenues.

Proposition 30 Tax Increases Temporary. Proposition 30 increases the sales tax rate for all taxpayers through 2016 and PIT rates on upper–income taxpayers through 2018. In 2017–18, the last fiscal year of our forecast, we estimate that the higher PIT rates will raise about $5.6 billion in additional revenues. When those taxes expire beginning in 2018–19 (outside the time period considered in our forecast), ongoing surpluses could be several billion dollars lower.

Considering Future Budget Surpluses

As noted above, there are many ways that the future operating surpluses we now project could disappear or be reduced substantially. If, however, the state’s leaders choose to keep a tight rein on the budget over the next year and the economy avoids another recession over the next several years, they could experience the operating surpluses shown in Figure 2. During the 2013–2014 legislative session, lawmakers may want to begin considering how to use such potential surpluses. There are a variety of priorities for surplus funds, as described below.

Building a Reserve? As noted above, Proposition 58 generally requires that 3 percent of estimated General Fund revenues be deposited in the BSA, the state’s rainy day fund. Beginning in 2015–16, we project potential surpluses that would accommodate such a transfer. Within the next few years, we advise the Legislature and the Governor to begin building the reserve envisioned by Proposition 58, which could buy time to deal with the budgetary problem accompanying the next economic downturn. While our forecast does not assume such a downturn, one could easily materialize by 2018. For this reason, we favor BSA deposits as one priority for the use of available resources over the next few years.

Paying Down Budgetary Liabilities? As discussed above, our forecast assumes that special fund loans to the General Fund are paid back consistent with recent repayment schedules provided by the administration and that $1.2 billion of such loans remain outstanding by the end of 2017–18. The state could choose to pay down these loans faster. Paying down the loans faster would relieve the General Fund of some additional interest costs, allow special funds to either expand programs or reduce fees, and serve as a possible additional budget cushion for the General Fund during future recessions (since special fund balances available to be borrowed at that time could be larger). Other elements of the wall of debt (such as addressing the backlog of payments related to local government mandates) also could be funded from any surpluses that materialize. Still, other elements of the wall of debt could be retired with funds made available as part of the Proposition 98 minimum guarantee each year.

Addressing Retirement Liabilities? Unfunded liabilities of the state’s key pension systems—the California Public Employees’ Retirement System, the California State Teachers’ Retirement System (CalSTRS), and the University of California (UC) Retirement Plan—and the retiree health programs serving state government (including the California State University system) and UC represent funds not currently set aside to pay for benefits already earned by current and past public employees. While this year’s pension legislation reduces significantly the net employer cost of benefits that will be earned by future public employees, these unfunded liabilities must still be addressed. As such, one possible use for potential surpluses is paying down these significant liabilities, which total over $150 billion.

A key priority of the state in this regard probably should be a funding plan to address CalSTRS’ unfunded liabilities. Additional funding from the state, districts, and/or teachers of over $3 billion per year (and growing over time) likely will be required to keep CalSTRS solvent and retire its unfunded liabilities over the next several decades. Under a resolution approved by both houses of the Legislature this year, CalSTRS will submit several proposals in February 2013 for how to better fund the system in the future. Assisting UC in rebuilding the funding status of its pension system is another possible priority for surplus funds. Addressing these unfunded liabilities sooner likely would save state and local funds, compared to the costs of funding them down the road. This is because contributing funds to the pension systems sooner means that the systems can invest the funds and generate investment returns earlier than would otherwise be the case.

Selectively Restoring Cuts? The state has reduced spending in recent years in most areas, including health and social services programs, schools, universities and community colleges, the courts, and state administration. The state has also generally not provided COLAs or inflation adjustments for most of these programs. A key decision to consider for possible budget surpluses will be to what extent to use them to restore some of these cuts. (In Chapter 3 of this report, for example, we discuss potential priorities for the state in the use of increased Proposition 98 school funding over the next few years.)

Investing in Infrastructure? Another option for the use of potential surpluses would be investment in the state’s infrastructure. Our forecast, for example, assumes no additional bond authorizations for infrastructure even though several programs, such as K–12 and higher education, have exhausted most of their existing bond authority. Our forecast also does not include bond payment costs related to the $11 billion water bond now scheduled for the November 2014 statewide ballot. In our August 2011 report, A Ten–Year Perspective: California Infrastructure Spending, we noted various major infrastructure funding needs for the state, including those related to aging infrastructure and a growing backlog of deferred maintenance.

To effectively assess the enormous variety and complexity of the state’s infrastructure needs, the state needs a well–defined process for planning and financing projects. Unfortunately, the state does not have such a process. Particularly in the event that the state pursues a new infrastructure investment program in the coming years, a new approach to planning and financing it is needed, as we discussed in the August 2011 report.

Conclusion

The state’s economic recovery, prior budget cuts, and the temporary taxes provided by Proposition 30 have combined to bring California to a promising moment: the possible end of a decade of acute state budget challenges. If a steady economic recovery continues and the Legislature and the Governor keep a tight rein on state spending in the next couple of years, there is a strong likelihood that the state will have operating surpluses in subsequent years. The state has many choices for what to do with these surpluses. We advise the state’s leaders to begin to build the reserve envisioned by Proposition 58 as soon as possible. Beyond building a reserve, the state must develop strategies to address several substantial liabilities that will have to be paid—most notably, unfunded retirement liabilities and outstanding loans from the state’s special funds to the General Fund.

Chapter 2

Economy, Revenues, and Demographics

Economic Outlook

Figure 1 shows a summary of our forecast for both the U.S. and California economies through 2018. Figure 2 compares the near–term economic forecast with other recent California economic forecasts, including the Department of Finance’s (DOF) May Revision forecast (which was used as the basis for revenue assumptions in the 2012–13 Budget Act).

Figure 1

LAO Economic Forecast Summary

|

United States

|

2009

|

2010

|

2011

|

2012

|

2013

|

2014

|

2015

|

2016

|

2017

|

2018

|

|

Unemployment rate

|

9.3%

|

9.6%

|

8.9%

|

8.2%

|

8.0%

|

7.6%

|

6.9%

|

6.4%

|

6.2%

|

6.0%

|

|

Percent change in:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Real gross domestic product

|

–3.1%

|

2.4%

|

1.8%

|

2.1%

|

1.8%

|

3.0%

|

3.4%

|

2.9%

|

2.7%

|

2.5%

|

|

Personal income

|

–4.8

|

3.8

|

5.1

|

3.5

|

3.9

|

4.9

|

4.9

|

4.9

|

4.3

|

4.4

|

|

Wage and salary employment

|

–4.4

|

–0.7

|

1.1

|

1.4

|

1.3

|

1.8

|

2.0

|

1.8

|

1.3

|

0.9

|

|

Consumer price index

|

–0.4

|

1.6

|

3.2

|

2.0

|

1.3

|

1.7

|

1.7

|

1.9

|

1.9

|

2.0

|

|

Housing starts (thousands)

|

554

|

587

|

609

|

751

|

949

|

1,276

|

1,587

|

1,690

|

1,713

|

1,709

|

|

Percent change from prior year

|

–38.8%

|

5.9%

|

3.7%

|

23.3%

|

26.4%

|

34.5%

|

24.4%

|

6.5%

|

1.4%

|

–0.2%

|

|

S&P 500 average monthly level

|

947

|

1,139

|

1,269

|

1,384

|

1,476

|

1,541

|

1,615

|

1,684

|

1,751

|

1,817

|

|

Percent change from prior year

|

–22.5%

|

20.3%

|

11.4%

|

9.0%

|

6.7%

|

4.4%

|

4.8%

|

4.3%

|

3.9%

|

3.8%

|

|

Federal funds rate

|

0.2

|

0.2

|

0.1

|

0.1

|

0.1

|

0.1

|

0.6

|

2.6

|

4.0

|

4.0

|

|

California

|

2009

|

2010

|

2011

|

2012a

|

2013a

|

2014

|

2015

|

2016

|

2017

|

2018

|

|

Unemployment rate

|

11.4%

|

12.3%

|

11.8%

|

10.6%

|

9.6%

|

8.7%

|

7.8%

|

7.1%

|

6.7%

|

6.7%

|

|

Percent change in:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Personal income

|

–5.8%

|

3.1%

|

5.2%

|

4.1%

|

4.7%

|

5.5%

|

5.8%

|

5.4%

|

4.9%

|

4.7%

|

|

Wage and salary employment

|

–6.0

|

–1.1

|

0.9

|

1.7

|

2.3

|

2.5

|

2.6

|

2.1

|

1.7

|

1.1

|

|

Consumer Price Index

|

–0.3

|

1.3

|

2.6

|

2.2

|

1.3

|

1.7

|

1.7

|

1.9

|

1.9

|

2.0

|

|

Housing permits (thousands)

|

36

|

45

|

47

|

63

|

83

|

113

|

139

|

155

|

168

|

164

|

|

Percent change from prior year

|

–43.9%

|

23.0%

|

5.9%

|

32.6%

|

32.6%

|

35.8%

|

22.4%

|

11.6%

|

8.4%

|

–1.9%

|

|

Single–unit permits (thousands)

|

25

|

26

|

22

|

27

|

37

|

53

|

70

|

80

|

87

|

82

|

|

Multi–unit permits (thousands)

|

11

|

19

|

26

|

36

|

46

|

61

|

68

|

75

|

81

|

83

|

Figure 2

Comparing This Economic Forecast With Other Recent Forecastsa

|

|

2012

|

|

2013

|

|

DOF

May

2012

|

LAO May 2012

|

UCLA

Sept 2012

|

LAO

Nov

2012

|

DOF

May

2012

|

LAO May

2012

|

UCLA

Sept

2012

|

LAO

Nov

2012

|

|

United States

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Percent change in:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Real Gross Domestic Product

|

2.2%

|

2.2%

|

2.1%

|

2.1%

|

|

2.4%

|

2.4%

|

1.7%

|

1.8%

|

|

Employment

|

1.6

|

1.6

|

1.4

|

1.4

|

|

1.7

|

1.7

|

1.4

|

1.3

|

|

Consumer Price Index

|

2.1

|

2.2

|

2.0

|

2.0

|

|

2.0

|

1.7

|

1.7

|

1.3

|

|

S&P 500 Stock Indexb

|

8.1

|

9.2

|

NA

|

9.0

|

|

3.5

|

4.0

|

NA

|

6.7

|

|

Unemployment Rate

|

8.2

|

8.2

|

8.2

|

8.2

|

|

7.9

|

7.9

|

8.0

|

8.0

|

|

Federal Funds Rate

|

0.1

|

0.1

|

0.1

|

0.1

|

|

0.1

|

0.1

|

0.2

|

0.1

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

California

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Percent change in:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Personal Income

|

4.9c

|

3.9

|

3.0

|

4.1

|

|

3.4c

|

4.7

|

4.1

|

4.7

|

|

Employment

|

1.4

|

1.7

|

1.7

|

1.7

|

|

1.9

|

2.1

|

1.5

|

2.3

|

|

Unemployment Rate

|

10.9

|

10.7

|

10.7

|

10.6

|

|

10.4

|

9.9

|

9.8

|

9.6

|

|

Housing Permits (thousands)

|

53

|

59

|

50

|

63

|

|

81

|

69

|

69

|

83

|

U.S. Economic Forecast Down, State Forecast Up From Budget Act Forecast. In general, our updated U.S. economic forecast is somewhat weaker than the forecast upon which the 2012–13 Budget Act was based. This is based on recent trends in the nation’s economy, including apparent hesitation by businesses to invest and hire due in part to uncertainty concerning future federal tax and fiscal policies. At the same time, we are somewhat more optimistic about the California economy than we were in prior months due to rising strength in the state’s depressed housing market, vehicle sales, and various employment trends. Nevertheless, as noted below, this remains a slow economic recovery by historical standards.

(We note that our economic forecast was developed prior to both the election and the date on which Hurricane Sandy struck New Jersey and New York. Sandy is likely to affect national economic data in the coming months. One possibility is that the storm’s effects will reduce U.S. gross domestic product [GDP] growth below our forecast by a few tenths of a percentage point in the fourth quarter of 2012, but add back about that amount to GDP in the following quarter due to reconstruction efforts.)

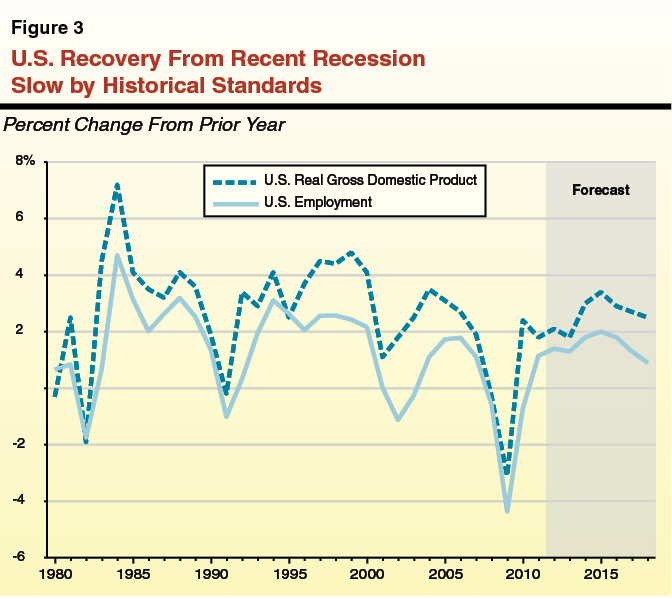

U.S. Economy

Slow Recovery From a Severe Economic Contraction. The 2007–2009 recession was the most severe economic contraction since the Great Depression. Moreover, as shown in Figure 3, the nation’s recovery from the recession has been slow by historical standards. Following the 1981–1982 recession, U.S. real GDP expanded at 3.5 percent or greater in each of the next four years, and the nation’s employment grew at 2.5 percent or greater in five of the six years during the 1984–1989 period. After the 1990–1991 recession, GDP grew by 3 percent to 5 percent in all but two years between 1992 and 2000, while employment grew by 2 percent to 3 percent annually through almost all of that period.

As shown in Figure 3, the current recovery—from the far more severe economic contraction of 2007–2009—is slower than the two recoveries described above in several respects. To date, GDP growth since the recession has been in the range of 2 percent per year, and we forecast that it will remain between 2 percent and 3 percent per year in all but one year between now and 2018. United States employment is forecast to grow at 2 percent or less each year through 2018.

Reasons for the Slow Recovery. Unlike other recent recessions, the 2007–2009 downturn was caused by an implosion of the nation’s financial sector and housing markets. This resulted in significant harm to banks’ balance sheets, as well as the balance sheets of households—particularly those that saw their net worth decline with the collapse of home values. Since the recession, financial institutions, households, and many businesses have been “deleveraging”—rebuilding their net worth and balance sheets step by painful step. Deleveraging requires saving, reducing consumption, and, in some cases, shedding liabilities through bankruptcies and renegotiation with creditors. Households and businesses are less capable of prodding the economy forward through spending, and financial institutions are less able to lend to facilitate such spending. These are some of the reasons why the U.S. economic recovery is so slow, relative to historical standards.

Federal Policy Important in the Forecast. The U.S. government borrowed significant amounts—including from international lenders—before, during, and after the recession to address the collapse of the financial sector, support some other economic sectors (such as the automotive industry and state and local governments), and provide economic stimulus. The Federal Reserve also has taken significant monetary policy actions intended to support the economy. As discussed later in this chapter, the U.S. government now faces major decisions about the future course of its fiscal and tax policies. These decisions have the potential to alter our economic forecast significantly over the next few years. In the worst case, federal decisions concerning the so–called “fiscal cliff” could plunge the U.S. economy into recession in 2013 and result in much weaker economic conditions in the near term than reflected in our forecast.

California Economy

California Also Recovering Slowly From the Recession. A similarly tepid recovery—compared to historical standards—is occurring in the California economy. The 2007–2009 recession was much more severe than recent downturns. Similar to the nation, personal income growth in California following the 2007–2009 recession has been much lower than after recent recessions. The rate of employment growth also has been slower. These trends are projected to continue in our forecast, although the recovery we are now projecting in the housing market is assumed to increase employment growth over the next four years, compared to what it would be otherwise.

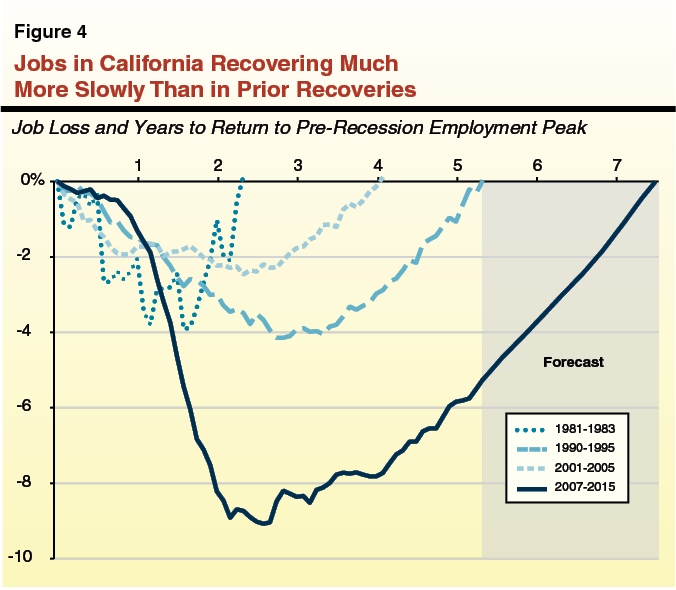

Figure 4 shows another way to look at the slowness of the current recovery in California. Covering the periods after the last four recessions, this figure shows how long it took California’s economy to return to the pre–recession peak level of jobs. After the 1981–1982 recession, it took over two years for the number of jobs in California to return to the pre–recession peak. After the 1990–1991 recession and the resulting cutbacks in the defense industry, it took over five years. After the 2001 recession and the bust of the “dot–com” bubble, it took four years. As shown in the figure, the total decline in jobs during and after the 2007–2009 recession—about 1.4 million jobs (9 percent of seasonally–adjusted employment)—was far greater than in the prior recessions shown. Moreover, the projected recovery period is much longer than for the prior recessions shown. Our forecast assumes that seasonally adjusted employment in California reaches its pre–recession peak in early 2015, or 7.5 years after its pre–recession peak in July 2007. (In 2015, California’s unemployment rate is projected to be around 8 percent—around 2 percentage points higher than it was in 2007—due in part to the state’s growing population over the period.)

Improvements in Job Market. Despite the slowness of this recovery, improvements in the state’s job market are evident. California now has regained 500,000 of the 1.4 million jobs it lost between July 2007 and February 2010, including a net gain of 262,000 jobs (1.9 percent) since September 2011. (This was faster than the national rate of employment growth—1.4 percent—over the same time period.) Due in part to some improvement in the housing sector, even California’s weakened construction industries now are adding jobs—up about 26,000 (4.7 percent) in the past year. Every category of construction jobs—except highway, street, and bridge construction—has contributed to these gains.

Manufacturing and Government Are Weak Job Sectors. While manufacturing employment has grown 1.5 percent for the U.S. as a whole over the past year, recent monthly jobs reports show that manufacturing jobs continue to decline in California—now down 11,000 jobs (0.9 percent) from one year ago. Moreover, while government employment has stabilized nationally, the combined number of federal, state, and local government jobs in California has declined—down 1.7 percent from one year ago. The bulk of the decrease is attributable to a drop of 35,000 jobs in local government educational services (a decline of 4 percent of jobs in this category). Manufacturing and government, therefore, are notable weak spots in an otherwise improving job situation in the state.

Housing Recovery Is Strengthening Somewhat

Recovery Has Been Slow. California’s housing market is well into its third year of recovery from the recent housing crisis, during which home prices declined substantially before hitting bottom in 2009. (The median existing single–family home price fell from $560,000 in 2007 to $275,000 in 2009.) The recovery has been anything but stable, marked instead by a series of false starts. Beginning in late 2009, for example, home prices in the state’s most populous areas—as shown in Figure 5—made solid gains for nine consecutive months before reversing trend throughout 2010 and 2011.

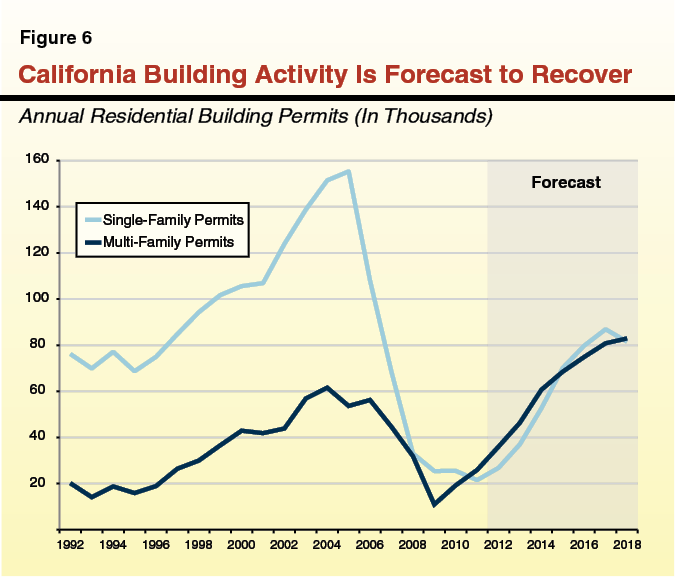

Construction activity also suffered during the housing crisis, coming to a near halt in 2009. As shown in Figure 6, single– and multi–family unit building permits declined from their combined peak of around 210,000 units annually in 2004 to just 36,000 units in 2009. Not surprisingly, construction–related jobs were one of the state’s most significantly weakened employment sectors.

Recent Housing Market Activity Stronger Than Previously Expected. A number of factors suggest that the demand for housing in California has picked up significantly from last year. Home prices in Los Angeles, San Diego, and San Francisco increased for the eighth consecutive month in August. Prices also have increased lately in the area’s most affected by the housing crisis: the Central Valley and the Inland Empire. In addition, monthly rents have increased throughout the coastal regions of the state, with some areas posting double–digit annual increases. Not only do large annual rent increases act as a signal to developers to build more units, they can also indirectly affect the market for single–family homes. Specifically, as the cost to rent increases more quickly than the cost to own, many current renters may find that is has become comparably more affordable to purchase a home, further bolstering the modest housing recovery. Finally, a recent jump in the number of building permits—an indicator of future housing activity—suggests that housing development may already be responding to recent demand indicators.

Current Forecast Projects Recent Strength to Continue. We view the trends discussed above as potentially more sustainable than those associated with earlier signs of housing strength, which proved largely illusory. Accordingly, we now forecast housing activity in the state to build upon current trends and stabilize in the final years of our forecast at approximately 160,000 new units annually, as shown in Figure 6. We forecast growth in both single– and multi–family unit building activity. Although our forecast level of building permits is much lower than during the housing boom of the mid–2000s, it remains a substantive upward adjustment in this forecast compared to our previous projections. This strength carries over to our forecast for assessed property values and property taxes, which is discussed in the nearby box.

Considerable Uncertainty Due to Difficulties in Forecasting Housing Trends. Forecasting housing activity is difficult because housing is influenced by complex and often unpredictable economic relationships. These include broad indicators like income and employment growth; real estate metrics like credit availability, mortgage rates, affordability, and prices (which may be subject to speculation); as well as behavioral markers like household formation and consumer confidence. In addition, the most recent data used in most economists’ forecast models—including our own—are from two atypical periods: the housing boom of the mid–2000s and the ensuing crisis of the past few years. Forecasting future housing activity relies heavily, therefore, on judgment and is prone to significant upward and downward variation. Because of the importance of the housing market to the state’s economy, housing activity below the levels in our forecast would in turn influence other key economic variables. For example, should building permits peak at 120,000 units annually (somewhat below our expectation of 160,000 units), the state’s sales tax base could grow about one–half of a percentage point slower each year through 2017–18 than our current forecast assumes. Construction employment and, therefore, income taxes also would be affected.

Federal Policy

As noted in Chapter 1, the fiscal cliff is a key uncertainty in this forecast. All economic and tax forecasts are based on assumptions about future federal tax, spending, and regulatory policies. Similar to recent forecasts from our office, the administration, and many economists, this forecast assumes that the President and the Congress agree to actions in the coming weeks to delay or eliminate the tax increases and spending cuts of the fiscal cliff in the near term. We believe this is the most likely type of outcome.

Tax Policy Issues Are the Key Short–Term Risk for the State Budget. We believe that the most significant fiscal cliff issues affecting the state budget in the near term are the tax policy decisions facing the President and the Congress. Under current federal law, many federal taxes are scheduled to rise in 2013—potentially increasing tax liabilities of about 90 percent of the population. The following tax increases (or end to temporary tax reductions) are scheduled to occur as part of the fiscal cliff:

- The end of the “Bush tax cuts” (which were extended during the Obama administration), resulting in increased federal income tax rates for the vast majority of all taxpayers and a variety of other tax changes. Among the tax changes are higher capital gains and dividend tax rates for many taxpayers.

- The expiration of the 2 percentage point reduction in Social Security payroll taxes in effect for the last two years—increasing the taxes of about 120 million households.

- Increased applicability of the federal alternative minimum tax (AMT)—potentially affecting tens of millions of taxpayers nationwide—in the coming months due to the fact that there has not yet been an AMT “patch” passed for 2012. (Taxpayers in states with relatively high state or local taxes—such as New York, New Jersey, and California—may be the most likely to be affected if there is no AMT patch.)

- An additional 0.9 percent tax on higher–income taxpayers’ earnings and a new 3.8 percent investment surtax on higher–income taxpayers’ capital gains, dividend, and interest income over certain thresholds, among other tax changes included in the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (the federal health care reform law).

- The expiration of several expanded tax credits for low–income households adopted during the Obama administration, such as the expansion of the earned income tax credit adopted as part of the 2009 federal stimulus package.

- The expiration of various other short–term tax provisions that Congress regularly extends (known as “extenders”), such as the adoption credit, the deduction for qualified education expenses, and the research and experimentation business tax credit.

- The end to the temporary “bonus depreciation” business tax provision for new investments, which has allowed companies to expense more costs of qualified machinery and equipment, rather than claiming deductions for depreciation over time.

- A resumption of pre–2000 federal estate tax rates and exemption amounts, which could result in the number of estates subject to this tax increasing by more than ten times.

Assessed Property Values Projected to Improve

Local Property Taxes Affect State Budget. Although property taxes are a local revenue source, our office forecasts statewide property tax revenue because the portion of these taxes that goes to school districts generally offsets—on a dollar–for–dollar basis—state General Fund spending on schools and community colleges.

Statewide Assessed Value Set to Improve. We expect net assessed property value in the state to increase 1.7 percent to $4.4 trillion in 2012–13. (Net statewide assessed value is the main determinant of property tax revenue and consists of the combined taxable value of all property in California.) For 2013–14, we project statewide assessed value to strengthen further, consistent with recent trends in the state’s housing markets, increasing 3.7 percent to $4.6 trillion. Over the final four years of our forecast, assessed value increases by an average of about 5 percent per year. This growth is based on the projected recovery in building activity and home values, as well as the general economic expansion that is assumed to continue in our forecast through 2018.

Property Taxes Available for School Districts Expected to Grow Faster Than Assessed Value. We expect local property taxes that go to K–12 and community college districts—revenues that generally offset state spending—to grow faster than statewide assessed value, for two reasons. First, local school property taxes benefit in the near term due to the dissolution of redevelopment agencies (RDAs) because a portion of property taxes that went to these agencies in recent years is now distributed to other local governments, including schools and community colleges. (The dissolution of RDAs is discussed in Chapter 3 of this report.) Second, the expected retirement of the state’s 2004 economic recovery bonds in 2016–17 increases local property taxes available for schools in the final years of our forecast by about $400 million per quarter. Because of these two factors, we expect property taxes for school and community college districts to grow at an average annual rate of over 6 percent between 2013–14 and 2017–18, notably faster than the growth in assessed value (about 5 percent annually) over the same period.

In addition to the tax increases, a broad array of domestic and defense–related spending cuts—some of which are to be implemented via the federal government’s “sequestration” process—are scheduled to begin in 2013. (These would impose on many programs an across–the–board spending cut—generally between 8 percent and 10 percent—but would not directly affect most of the major federal funding streams that flow through the state treasury.) Extended emergency unemployment insurance (UI) benefits also are scheduled to expire, which would shorten significantly the amount of time that some unemployed workers are eligible for benefits.

Forecast Assumes That Washington Avoids the Fiscal Cliff. As noted above, our economic and budgetary forecast assumes that the President and the Congress adopt measures in the next few weeks to delay or eliminate virtually all of the near–term tax increases and spending cuts of the fiscal cliff. Instead, we assume that federal officials eventually reach agreements that involve spending cuts and tax increases, phased in over many years, to address the federal government’s serious long–term budgetary challenges. Our forecast also assumes that the necessary increase in the federal debt ceiling in 2013 causes little or no disruption to the economy, including consumer confidence.

Recession Likely if Federal Leaders Are Deadlocked. If the President and the Congress cannot come to an agreement and the fiscal cliff tax increases go into effect (particularly when combined with the domestic and defense federal spending cuts in the current sequestration law), the U.S. economy likely would fall into recession in 2013. This in turn would cause the California economy to perform considerably weaker than we assume in our forecast and reduce state revenues substantially in the near term. In an alternative simulation in which we assumed a 0.6 percent contraction of real U.S. GDP in 2013—rather than the 1.8 percent increase in our forecast—state revenues in 2012–13 and 2013–14 combined were about $11 billion lower than indicated in our forecast. (For the state’s General Fund expenditures, such a revenue reduction would be accompanied by a lower Proposition 98 minimum guarantee and higher spending requirements under current law for various health and social services programs.) The bulk of the assumed drop in GDP in this alternative recession scenario results from the expiration of the Bush tax cuts and the payroll tax cut. Spending cuts, the end of the bonus depreciation policy, and the expiration of emergency UI benefits each are responsible for a smaller part of this hypothetical near–term economic contraction.

Policy Uncertainty Hindering U.S. and Global Economic Growth. The perception of political paralysis concerning economic policy in the U.S., Europe, and China has constrained global economic growth in recent months. These issues contribute to our weaker projections for near–term U.S. economic growth. Exports and business fixed investment had—until recently—been key drivers of the current global economic recovery, but U.S. export growth has slowed. Exports to China are growing at only 2.2 percent on a year–over–year basis, while exports to Europe have been down recently—both figures related to the weakened economies of those important trading partners. Our forecast assumes that business investments in structures, equipment, and software are now growing more slowly than before—a trend that could affect California’s technology and service sectors in the coming months. In general, uncertainty about federal tax and spending policy inhibits risk taking and causes businesses and consumers to be more cautious in their spending and investment decisions. While there are “downside” risks due to the fiscal cliff, we note as well that there are “upside” risks to our economic forecast. If, for example, there is a speedy agreement concerning these federal issues, this could be looked upon favorably by consumers and businesses, thereby encouraging them to spend, invest, and hire even more in the short term than we are projecting.

The Demographic Outlook

Domestic and International Migration Expected to Climb. A summary of the key findings of our California population forecast is shown in Figure 7. Over the next several years, we project steady overall growth in the state’s population of about 1 percent per year. Migration into California—from other states and countries—declines during periods of relative economic weakness here. As Figure 7 shows, we estimate that the state has recently experienced significant declines in domestic migration (that is, many more people have left California for other states than have come from other states). Our forecast projects that these trends are turning around, and total net migration (domestic and international) will be positive over the forecast period. The state’s population—now just over 38 million—is projected to surpass 40 million in 2017.

Figure 7

LAO California Population Forecast

(In Thousands)

|

|

2009

|

2010

|

2011

|

2012

|

2013

|

2014

|

2015

|

2016

|

2017

|

2018

|

|

Population (as of July 1)

|

37,077

|

37,318

|

37,639

|

38,004

|

38,414

|

38,849

|

39,305

|

39,727

|

40,133

|

40,541

|

|

Percent change from prior year

|

0.6%

|

0.7%

|

0.9%

|

1.0%

|

1.1%

|

1.1%

|

1.2%

|

1.1%

|

1.0%

|

1.0%

|

|

Births

|

527

|

510

|

507

|

511

|

516

|

522

|

528

|

534

|

538

|

542

|

|

Deaths

|

220

|

229

|

231

|

234

|

237

|

239

|

242

|

245

|

248

|

251

|

|

Net domestic migration

|

–144

|

–133

|

–87

|

–61

|

–27

|

–3

|

13

|

–19

|

–31

|

–31

|

|

Net international migration

|

58

|

94

|

128

|

149

|

157

|

155

|

157

|

151

|

147

|

147

|

Our forecast assumes continued declines in both birth rates and death rates. Specifically, women are waiting until later to have children and are having fewer children, on average, than in the past. This trend is largely responsible for a projected small decline in the state’s school–age and college–age populations between the 2010 and 2020 censuses. We forecast that there will be 6.7 million Californians age 5–17 in 2020 (down 1.4 percent from 2010) and 3.8 million who are age 18–24 (down 2.8 percent from 2010). In addition, Californians are living longer and this—coupled with the aging of the massive post–World War II “baby boom” generation—is resulting in large increases in the elderly population. We forecast that there will be 6.5 million Californians age 65 and over in 2020 (up 51 percent from 2010).

California’s Racial and Ethnic Makeup Continues to Change. In 1980, about 67 percent of Californians were non–Hispanic whites, and about 19 percent were Hispanic. By 2010, the census indicated that 40 percent of the state’s population consisted of non–Hispanic whites, and Hispanics made up 38 percent of the population. During the same time period, Asian Americans climbed from 5 percent to 13 percent of the population. African Americans made up 6 percent of the population in 2010, down from 7.5 percent in 1980.

In the next few years, the number of Hispanic Californians should surpass the number of non–Hispanic white residents. In 2020, we project that Hispanics will comprise 39 percent of the state’s population, followed by non–Hispanic whites (37 percent), Asian Americans (14 percent), African Americans (6 percent), and other racial and ethnic groups (4 percent).

Revenue Outlook

Figure 8 shows our multiyear forecast of General Fund and Education Protection Account (EPA) revenues, including revenues resulting from the two tax–related measures that voters approved at the statewide election on November 6, 2012. These two measures are Proposition 30 (which increases personal income tax [PIT] rates for higher–income Californians through 2018 and raises the sales and use tax [SUT] rates by 0.25 percentage points for four years beginning in 2013) and Proposition 39 (which institutes a new corporation tax [CT] apportionment policy that will result in some businesses paying more in taxes).

Figure 8

LAO November 2012 Revenue Forecasta

General Fund and Education Protection Account Combined (In Millions)

|

|

2011–12

|

2012–13

|

2013–14

|

2014–15

|

2015–16

|

2016–17

|

2017–18

|

|

Personal income tax

|

$53,213

|

$59,860

|

$61,712

|

$66,848

|

$71,602

|

$75,678

|

$79,786

|

|

Sales and use tax

|

18,859

|

20,839

|

22,721

|

24,354

|

25,993

|

26,835

|

27,214

|

|

Corporation tax

|

7,603

|

8,535

|

9,119

|

9,236

|

9,734

|

9,935

|

9,979

|

|

Subtotal, “Big Three” Taxes

|

($79,675)

|

($89,234)

|

($93,551)

|

($100,438)

|

($107,329)

|

($112,448)

|

($116,979)

|

|

Insurance tax

|

$2,204

|

$2,050

|

$2,187

|

$2,415

|

$2,492

|

$2,576

|

$2,667

|

|

Other revenuesb

|

2,819

|

2,695

|

2,129

|

2,071

|

2,103

|

2,034

|

2,069

|

|

Net transfers and loansc

|

1,784

|

1,631

|

–1,149

|

–622

|

–941

|

–638

|

–134

|

|

Total Revenues and Transfers

|

$86,482

|

$95,610

|

$96,743

|

$104,332

|

$111,017

|

$116,461

|

$121,627

|

Figure 9 compares our revenue forecast for 2011–12 and 2012–13 to other recent forecasts. (Additional figures comparing this forecast with other recent forecasts are available on our website.)

Figure 9

Comparisons With Prior Revenue Forecastsa

General Fund and Education Protection Account Combined (In Millions)

|

|

2011–12

|

|

2012–13

|

|

LAO

May

2012

|

Budget Act June 2012

|

LAO

November 2012

|

LAO

May

2012

|

Budget Act June 2012

|

LAO

November

2012

|

|

Personal income tax

|

$52,366

|

$52,958

|

$53,213

|

|

$59,368

|

$60,268

|

$59,860

|

|

Sales and use tax

|

18,927

|

18,921

|

18,859

|

|

20,765

|

20,605

|

20,839

|

|

Corporation tax

|

8,623

|

8,208

|

7,603

|

|

8,869

|

8,488

|

8,535

|

|

Subtotals, “Big Three” Taxes

|

($79,916)

|

($80,087)

|

($79,675)

|

($89,003)

|

($89,361)

|

($89,234)

|

|

Insurance tax

|

$2,150

|

$2,148

|

$2,204

|

|

$2,093

|

$2,089

|

$2,050

|

|

Other revenues

|

2,800

|

2,810

|

2,819

|

|

2,712

|

2,849

|

2,695

|

|

Net transfers and loans

|

1,784

|

1,784

|

1,784

|

|

1,489

|

1,588

|

1,631

|

|

Total Revenues and Transfers

|

$86,650

|

$86,830

|

$86,482

|

$95,297

|

$95,887

|

$95,610

|

|

Difference—LAO November Forecast Minus Budget Act

|

–$348

|

–$277

|

|

Difference—LAO November Forecast Minus LAO May Forecast

|

–$169

|

$314

|

Personal Income Tax

Little Net Change in Budget Act Revenue Assumptions. Before considering the passage of Proposition 30, which will generate some revenue that the state plans to attribute—or “accrue”—to 2011–12, PIT revenues for the prior fiscal year currently are estimated to have been $50.4 billion. After including our current projections for Proposition 30 collections, we now estimate that 2011–12 General Fund and EPA PIT revenues will total $53.2 billion, $255 million above the level assumed in the 2012–13 budget package. In 2012–13, we project PIT revenues to reach $59.9 billion, $408 million below the level assumed in the 2012–13 budget package. Therefore, for the two fiscal years combined, our PIT forecast is $153 million below the level assumed in the budget plan. For such a large, volatile revenue source, this is a minor forecasting difference.

The over $6.6 billion of year–to–year growth between 2011–12 and 2012–13 is due to (1) a full fiscal year of increased revenue under Proposition 30, (2) assumed growth in the economy and stock market, and (3) 2012–13 revenues related to Facebook, Inc.’s initial public offering (IPO) of stock.

About 6 Percent Annual Growth in PIT Revenues Forecast. For 2013–14, we forecast General Fund and EPA PIT revenue to grow to $61.7 billion, with steady growth thereafter, reaching $79.8 billion in 2017–18. Between 2012–13 and 2017–18, we forecast average annual growth in PIT collections of 5.9 percent.

Strengthening Job Market Helps PIT Revenues. The PIT is the state’s largest General Fund revenue source and grows over time largely in line with the main component of taxable personal income: the wages and salaries of Californians. The most recent data for 2010 indicate that wages and salaries made up 73 percent of California resident tax filers’ adjusted gross income (AGI) and accounted for 63 percent of PIT revenue. Accordingly, the strength of trends in the state’s job market plays a major role in the PIT’s overall growth rate.

Consistent with the decline in employment in the state during 2008 and 2009 (illustrated earlier in this chapter in Figure 4), resident tax filers saw their wage and salary income drop from $716 billion in 2008 to $679 billion in 2009 (down 5.2 percent). In 2010, wages and salaries grew to $697 billion (up 2.7 percent). The Franchise Tax Board (FTB) will provide us with our first solid data on 2011 wages later this month, but based on 2011 and 2012 PIT collections, economic data, and our forecasting estimates, we currently assume that wages and salaries grew to about $730 billion (up 4.6 percent) in 2011. The significantly greater increase in wages and salaries in 2011 was driven by the start of the state’s job recovery in that year.

Furthermore, based on data received to date for 2012, we assume that wages and salaries will grow to $774 billion (up 6 percent) in 2012. As 2012 job growth in the state is faster than that in 2011, so is the growth in overall taxable wages. (A small portion of this 2012 gain represents taxable income that higher–income Californians, in particular, are projected to accelerate—that is, choose to receive early—in order to benefit from lower federal tax rates in current law before the scheduled fiscal cliff tax increases.)

Our forecast model assumes that California resident tax filers’ wage and salary income surpasses $1 trillion for the first time in 2017. Between 2012 and 2018, we assume that wages and salaries for all resident California taxpayers grow at an average annual rate of about 5 percent—similar to the growth rate in recent decades. Employment growth, inflation, and changes in labor productivity contribute to rising wages and salaries throughout the economy.

Capital Gains Drive PIT Volatility. Net capital gains made up only 6 percent of AGI in 2010 and 3 percent in 2009, but this relatively small part of overall income is the most difficult element of the PIT to project. Net capital gains—the difference between capital gains and capital losses reported on tax returns—represent net investment gains from sales of assets such as stocks, bonds, and real estate. Data suggest that the single greatest driver of capital gains trends is the direction of the stock market. All economic models must make assumptions about stock market trends, as does ours. Nevertheless, in any given time period, the stock market can move up or down in ways that are both wildly volatile and inconsistent with trends elsewhere in the economy. As such, capital gains forecasts are subject to a wide band of uncertainty.

While capital gains made up 6 percent of AGI in California in 2010, personal income taxes paid on these capital gains totaled 10.5 percent of overall PIT paid that year, according to FTB estimates. The typical dollar of capital gains is taxed at a higher rate than the typical dollar of wage and salary income. In 2010, 15 percent of total AGI was reported on tax returns that had AGIs of $1 million or greater. By contrast, over 75 percent of capital gains were reported on returns with taxable income of $1 million or greater. Returns with $10 million or more of taxable income had 46 percent of all capital gains.

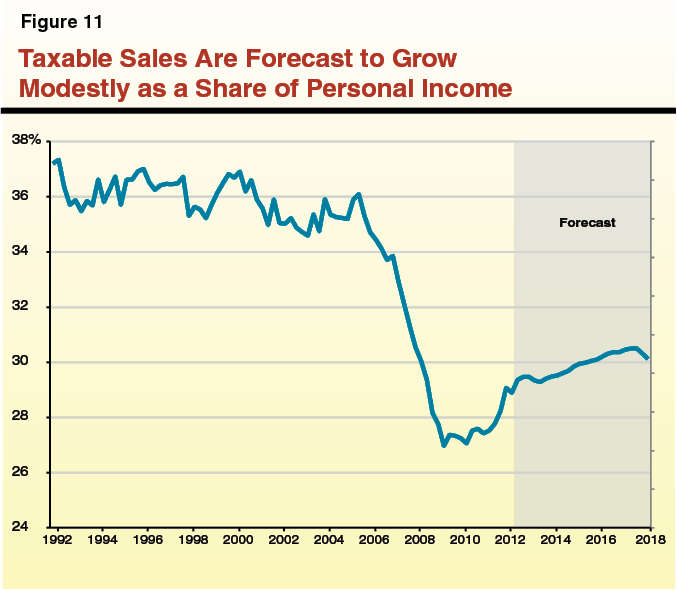

Net capital gains reported by resident tax filers climbed as high as $120 billion in 2000 (equal to 10.6 percent of personal income) and $132 billion in 2007 (8.4 percent of personal income), as shown in Figure 10. Such increases were driven by “asset bubbles” in the stock market and/or the real estate market. Net capital gains fell to $29 billion in 2009 (1.9 percent of personal income) before rising, along with the recovery in the stock market, to $55 billion in 2010 (3.5 percent of personal income). While the stock market has grown fairly well during much of the time since then, we assume that net capital gains remained fairly flat in 2011, given the substantial losses that investors experienced during the recession (which “offset” the gains that they report). Figure 10 shows our forecast for net capital gains, including gains assumed to be accelerated from 2013 to 2012 due to the lower federal tax rates currently in federal law prior to the fiscal cliff.

Figure 10

Capital Gains Assumed to Rise in Forecast

(Dollars in Billions)

|

Tax Year

|

CaliforniaResidents—

Net Capital Gains

|

As Percent of Personal Income

|

|

1990

|

$22

|

3.5%

|

|

1991

|

17

|

2.6

|

|

1992

|

17

|

2.5

|

|

1993

|

20

|

2.7

|

|

1994

|

18

|

2.5

|

|

1995

|

21

|

2.7

|

|

1996

|

33

|

4.0

|

|

1997

|

47

|

5.4

|

|

1998

|

61

|

6.4

|

|

1999

|

94

|

9.2

|

|

2000

|

120

|

10.6

|