In this report, we analyze the Governor’s Proposition 98 budget package. The report begins with an overview. The next six sections analyze all the Governor’s major Proposition 98 proposals, except for his Local Control Funding Formula proposals, which we analyze separately in our companion document, Restructuring the K–12 Funding System. The penultimate section of this report compares the fiscal effects of the Governor’s Proposition 98 plan with our Proposition 98 recommendations. The final section lists all the recommendations we make throughout the report.

Governor Proposes $2.7 Billion Increase in Proposition 98 Funding. Figure 1 shows Proposition 98 funding for preschool, K–12 education, CCC, and various other state education programs. The Governor’s budget increases total Proposition 98 funding by $2.7 billion—a 5 percent increase from the revised current–year level. The General Fund share of Proposition 98 increases by 9 percent whereas the share from local property tax (LPT) revenue is projected to drop by 4 percent. This drop is due to the tapering off of the transfer of one–time cash assets from former redevelopment agencies (RDAs). Also shown in the figure, the year–to–year increase in Proposition 98 funding is notably greater for community colleges (10 percent) than for K–12 education (4 percent). About half of the community college increase is related to the Governor’s proposal to restructure adult education.

Figure 1

Proposition 98 Fundinga

(Dollars in Millions)

|

|

2011–12 Actual

|

2012–13 Revised

|

2013–14 Proposed

|

Change From 2012–13

|

|

Amount

|

Percent

|

|

Preschool

|

$368

|

$481

|

$481

|

—

|

—

|

|

K–12 Education

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

General Fund

|

$29,368

|

$33,406

|

$36,084

|

$2,679

|

8%

|

|

Local property tax revenue

|

11,963

|

13,777

|

13,160

|

–618

|

–4

|

|

Subtotals

|

($41,331)

|

($47,183)

|

($49,244)

|

($2,061)

|

(4%)

|

|

California Community Colleges

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

General Fund

|

$3,279

|

$3,543

|

$4,226

|

$683

|

19%

|

|

Local property tax revenue

|

1,974

|

2,256

|

2,171

|

–85

|

–4

|

|

Subtotals

|

($5,253)

|

($5,799)

|

($6,397)

|

($597)

|

(10%)

|

|

Other Agencies

|

$83

|

$78

|

$79

|

$1

|

1%

|

|

Totals

|

$47,035

|

$53,541

|

$56,200

|

$2,659

|

5%

|

|

General Fund

|

$33,097

|

$37,507

|

$40,870

|

$3,362

|

9%

|

|

Local property tax revenue

|

13,937

|

16,034

|

15,331

|

–703

|

–4

|

Programmatic Per–Student Funding Increases for Schools and Colleges. Under the Governor’s budget, Proposition 98 programmatic per–student funding for schools is $7,929—an increase of $360 (5 percent) from the revised current–year level. For community colleges, Proposition 98 programmatic per–student funding is $5,969—an increase of $522 (10 percent) from the revised current–year level.

Estimate of 2012–13 Minimum Guarantee Changes Slightly. For 2012–13, the administration’s estimate of the Proposition 98 minimum guarantee is $53.5 billion—down $54 million from the budget act estimate. (Various technical adjustments and changes in revenue decrease the minimum guarantee by $480 million. These were largely offset, however, by a guarantee increase of $426 million due to the revenue raised from Proposition 39. These revenues were not assumed in the 2012–13 Budget Act.) Proposition 98–related spending is estimated to be $163 million above the revised estimate of the minimum guarantee, primarily due to increases in revenue limit costs stemming from higher–than–projected charter school attendance. To bring spending down to the minimum guarantee, the Governor proposes to reclassify $163 million in 2012–13 appropriations as funds for meeting a statutory obligation associated with the Quality Education Investment Act (QEIA). Such action has no programmatic effect on schools or community colleges.

2013–14 Minimum Guarantee Increases Due to Revenue Growth. For 2013–14, the Governor proposes to fund at the administration’s estimate of the minimum guarantee—$56.2 billion. The $2.7 billion year–to–year increase in the guarantee is driven by the state’s General Fund revenue growth. Student average daily attendance (ADA)—another factor that drives growth in the minimum guarantee—is projected to grow by 0.1 percent. (As described in the nearby box, the minimum guarantee can be very sensitive to year–to–year changes in state revenues.)

Recent information regarding 2012–13 tax revenues—in which January 2013 personal income tax (PIT) collections were $5 billion higher than projected—demonstrate the significant uncertainty regarding state revenue estimates. Although the state’s PIT revenues have been subject to large swings, these effects recently have been magnified by a number of factors, including the passage of Proposition 30 (which increased taxes on high–income earners, whose incomes are most volatile), the initial public offering of Facebook, anticipation of federal tax increases, and changes in state revenue accrual policies. Theses swings in tax revenues can significantly change the state’s Proposition 98 requirements. Below, we discuss some of the possible implications of higher revenues on the Proposition 98 minimum guarantee.

Virtually All New Revenue in 2012–13 Would Go to Proposition 98 Programs. To the extent that final 2012–13 revenue collections are higher than projected, the 2012–13 minimum guarantee would increase roughly dollar for dollar. (Virtually all revenue goes to Proposition 98 programs due to recent state decisions regarding how to make maintenance factor payments.) As a result, higher revenues in 2012–13 could have substantial benefit for schools and community colleges but provide little, if any, benefit for other state programs.

2013–14 Minimum Guarantee Could Be Lower Year Over Year, but Two–Year Proposition 98 Funding Likely Would Be Higher Than Under Governor’s Budget. If the increase in 2012–13 revenues were temporary—that is, if they did not result in a corresponding increase in 2013–14 revenues—the 2013–14 minimum guarantee could be lower than the Governor’s estimate. This is because the year–to–year growth in General Fund revenues under this scenario is reduced. This in turn would lower the minimum guarantee in 2013–14. Funding over the two–year period, however, likely would be higher than under the Governor’s budget.

Spending Option if This Scenario Materializes. If recent revenue collection trends persist and the Proposition 98 minimum guarantee sees a corresponding increase in 2012–13, the Legislature could use these new, additional funds to accelerate pay down of school and community college deferrals. This approach would pay down deferrals more quickly without affecting ongoing programmatic support. If 2013–14 revenues are lower than the Governor’s January estimate, the Legislature correspondingly could reduce the amount of funds dedicated in 2013–14 to paying down deferrals. In essence, the state could adjust its deferral payments across the two years to moderate the effects of revenue volatility on programmatic funding.

Figure 2 summarizes the major changes in Proposition 98 spending proposed by the Governor. We discuss these proposals below, focusing first on proposals affecting schools and then turning to CCC proposals.

Figure 2

Proposition 98 Spending Changes

(In Millions)

|

2012–13 Revised Spending

|

$53,541

|

|

Technical Changes

|

|

|

Make technical adjustments

|

$148

|

|

Fund K–12 categorical growth

|

49

|

|

Fund K–12 revenue limit growth

|

3

|

|

Adjust for prior–year deferral payments

|

–2,225

|

|

Subtotal

|

(–$2,025)

|

|

K–12 Policy Changes

|

|

|

Pay down deferrals

|

$1,765

|

|

Transition to new funding formula

|

1,630

|

|

Allocate money for energy–related projects

|

401

|

|

Add two programs to mandate block granta

|

100

|

|

Provide COLA for certain programsb

|

63

|

|

Swap one–time funds

|

–17

|

|

Subtotal

|

($3,941)

|

|

CCC Policy Changes

|

|

|

Create new adult education categorical program

|

$300

|

|

Increase funding for apportionments

|

197

|

|

Pay down deferrals

|

179

|

|

Allocate money for energy–related projects

|

50

|

|

Fund new technology initiative

|

17

|

|

Subtotal

|

($742)

|

|

Total Changes

|

$2,659

|

|

2013–14 Proposed Spending

|

$56,200

|

Major K–12 Proposals. The Governor’s K–12 education budget includes $1.8 billion to retire some existing school payment deferrals. The Governor’s budget also provides $1.6 billion as part of a major initiative to restructure the way the state allocates funding to school districts, charter schools, and county offices of education (COEs). For school districts and charter schools, his plan would replace most existing general purpose and categorical funding with a single, new funding formula. The formula includes base grants adjusted for various grade spans as well as supplemental funding based on counts of English learners and low–income students. Virtually all of the proposed $1.6 billion funding increase would be used to align each school district’s and charter school’s allocation more closely to target funding levels established under the new formula. For COEs, the Governor’s plan also would replace existing general purpose and categorical funding with a new formula. The COE formula would incorporate funding for (1) services COEs provide to school districts and (2) alternative education programs. The budget provides $28 million to begin increasing COE allocations to the COE target funding rate.

In addition to these proposals, the Governor’s budget allocates $400.5 million to school districts for energy–efficiency projects. This appropriation—along with a corresponding community college appropriation—is intended to fulfill the state’s Proposition 39 spending requirements. The budget also provides a $100 million increase to the school mandate block grant to reflect the addition of two large mandates: Graduation Requirements and BIPs. The Governor’s plan also includes a 1.65 percent cost–of–living adjustment (COLA) for four categorical programs that are not consolidated into the new funding formula—special education, child nutrition, California American Indian Education Centers, and the American Indian Early Childhood Education Program. In addition to the ongoing Proposition 98 funding shown in Figure 2, the budget includes $9.7 million in one–time funding for the Emergency Repair Program (ERP), which provides funding to school districts for facility repairs.

Major CCC Proposals. The largest of the Governor’s CCC augmentations is $300 million for a restructured adult education program. The Governor’s budget also includes $197 million in discretionary funding to be allocated based on the priorities of the Chancellor’s Office. In addition, the Governor’s plan provides $179 million to retire existing payment deferrals, $49.5 million for energy–efficiency projects, and $16.9 million for a new CCC technology initiative.

The largest augmentation in the Governor’s budget is $1.9 billion to reduce the amount of outstanding K–14 payment deferrals. This proposal is part of the Governor’s multiyear plan for paying off the state’s outstanding one–time education obligations. Below, we provide background on these obligations, describe the Governor’s proposal to pay off most of these obligations over the next four years, and discuss our assessment of the payment plan.

State’s One–Time Education Obligations Have Grown Significantly Over Several Years. The state currently has large outstanding one–time obligations relating to schools and community colleges. Figure 3 describes each existing type of obligation and identifies the corresponding amount the state owes. The largest outstanding obligation involves school and community college payments that the state is making late. The state also has a large backlog of unpaid school and community college mandate claims. The other two obligations—for the ERP and QEIA—are connected with lawsuits.

Figure 3

State Has Several Outstanding One–Time School and Community College Obligations

(In Millions)

|

Obligation

|

Description

|

Amount Outstandinga

|

|

Payment deferrals

|

State has deferred certain school and community college payments from one fiscal year to the subsequent fiscal year, thereby achieving one–time state savings.

|

$8,205

|

|

Mandates

|

State must reimburse school and community college districts for performing certain state–mandated activities. State deferred payments seven consecutive years (2003–04 through 2009–10).

|

4,014

|

|

Emergency Repair Program

|

As part of the Williams settlement, state agreed to provide certain schools with $800 million for emergency facility repairs.

|

452

|

|

Quality Education Investment Act

|

Associated with a Proposition 98 suspension in 2004–05, the state agreed to provide an additional $2.7 billion to schools and community colleges over a multiyear period.

|

247

|

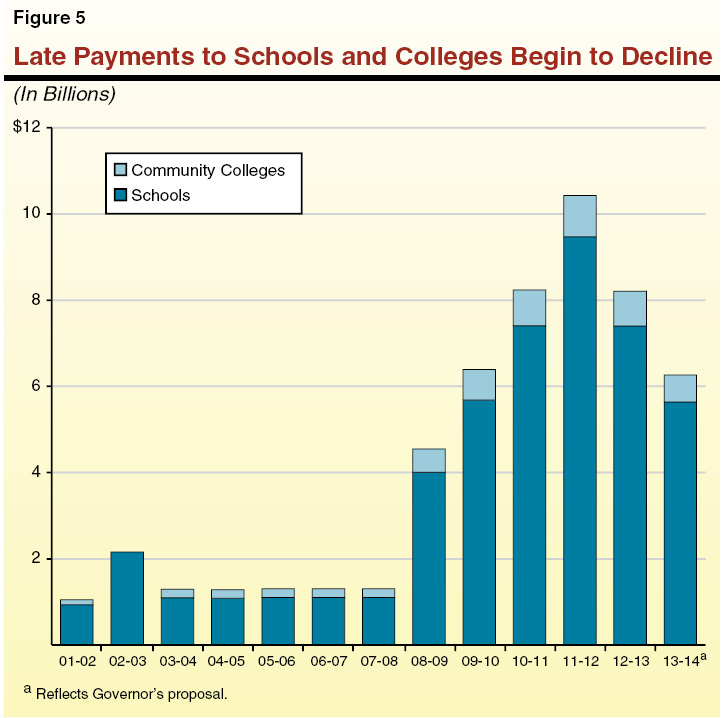

State Relied Heavily on Deferrals During Difficult Fiscal Times. Over the past several years, the state has significantly increased the amount of school and community college payments it makes late. The first Proposition 98 deferrals were adopted in the middle of 2001–02, when $1.1 billion in K–12 payments were deferred from late June 2002 to early July 2002. This delay, while only a few weeks, allowed the state to achieve one–time savings by reducing Proposition 98 General Fund spending in 2001–02. Schools continued to operate a larger program using cash reserves. In 2008–09, facing an even larger budgetary shortfall, the state delayed $3.2 billion in Proposition 98 payments to achieve one–time General Fund savings. The state adopted additional deferrals in each of the next three years. By 2011–12, a total of $10.4 billion in annual Proposition 98 payments were paid late (roughly 21 percent of total Proposition 98 support).

State Has One–Time Proposition 98 Settle–Up Obligations. In addition to the obligations discussed above, the state has $1.7 billion in outstanding one–time Proposition 98 obligations known as “settle–up” obligations. A settle–up obligation is created when the minimum guarantee increases midyear and the state does not make an additional payment within that fiscal year to meet the higher guarantee. Because the associated ongoing base increase in the minimum guarantee is reflected automatically in the subsequent year’s Proposition 98 appropriation, the state is left with only a one–time obligation to backfill the unanticipated prior–year shortfall. The state’s existing settle–up obligations were created as a result of underfunding in 2006–07 ($212 million), 2009–10 ($1.2 billion), 2010–11 ($2.5 million), and 2011–12 ($251 million). Settle–up funds can be used for any educational purpose, including paying off other state one–time obligations, such as deferrals and mandates.

State Has Options for Paying Down Outstanding Obligations. The state typically retires one–time obligations by making a series of payments over several years. In most cases, the state can choose whether to make these payments using ongoing or one–time funds. When using ongoing funds, the state sets aside a portion of undesignated Proposition 98 resources, which reduces the amount of funds available for other ongoing Proposition 98 purposes. (In the subsequent year, these resources are “freed up” to pay off additional obligations or to make programmatic augmentations.) Alternatively, the state can use one–time appropriations made on top of the annual minimum guarantee—such as settle–up funds—to pay off these obligations. This approach has no effect on the ongoing programmatic funding available for schools and community colleges.

As Figure 4 shows, the Governor’s proposal includes a multiyear plan for paying off the state’s outstanding one–time education obligations. We discuss the proposal in more detail below.

Figure 4

Governor’s Multiyear Plan for Paying Education One–Time Obligations

(In Millions)

|

Obligation

|

Paid Within Annual Proposition 98 Appropriation?

|

2013–14

|

2014–15

|

2015–16

|

2016–17

|

Total Payments Over Perioda

|

|

Payment deferrals

|

Yes

|

$1,950

|

$2,986

|

$3,137

|

$132

|

$8,205

|

|

Mandates

|

No

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

1,666

|

1,666

|

|

Emergency Repair Program

|

No

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

452

|

452

|

|

Quality Education Investment Act

|

No

|

—

|

247

|

—

|

—

|

247

|

|

Fiscal–Year Totals

|

|

$1,950

|

$3,233

|

$3,137

|

$2,250

|

$10,570

|

Uses Roughly Half of New Proposition 98 Funds to Pay Down Deferrals. In 2012–13, the state began reducing the amount of late payments by providing $2.2 billion to pay down Proposition 98 deferrals—$2.1 billion for schools and $159 million for community colleges. (This funding was contingent on the passage of Proposition 30.) In 2013–14, the Governor’s budget dedicates $1.9 billion to retire additional deferrals—$1.8 billion for schools and $179 million for community colleges. As Figure 5 shows, these payments would reduce the amount of outstanding deferrals to $6.3 billion. Each year for the subsequent three years, the Governor proposes to dedicate roughly half of available Proposition 98 funds toward additional deferral pay downs, with all deferrals eliminated by the end of 2016–17.

Retires a Few Other Obligations Over Period. The Governor’s plan provides $247 million on top of the minimum guarantee in 2014–15 for QEIA and an additional $452 million on top of the minimum guarantee in 2016–17 for ERP. These payments would fully retire the state’s statutory obligation for both programs. In 2016–17, the Governor also proposes to make a $1.7 billion payment to retire the state’s existing settle–up obligations. These funds would be allocated to school districts and community colleges to reduce the mandate backlog. (A backlog of roughly $2.3 billion would remain.)

Governor’s Plan Reasonable. Over the next several years, as state General Fund revenue growth results in additional Proposition 98 resources, the Legislature will want to weigh the trade–offs between building up ongoing base support and retiring outstanding one–time obligations. Although no one right mix of spending exists, we think the Governor’s generally balanced approach is reasonable. Using such an approach would allow the state to retire most school and community college obligations by 2016–17—prior to the expiration of Proposition 30’s personal income tax increases—while also dedicating a substantial portion of Proposition 98 funding for ongoing programs.

Dedicate Unanticipated Proposition 98 Increases to One–Time Obligations. As we discuss earlier in the report, General Fund revenue estimates could be subject to significant swings over the next several years, largely due to volatility in the earnings of high–income taxpayers. These changes in General Fund revenues can result in significant midyear changes to the Proposition 98 minimum guarantee. Over the next several years, if the state receives unanticipated revenues that increase the minimum guarantee midyear, we recommend the Legislature dedicate these additional resources to accelerating the pay down of its one–time education obligations. This would allow the state to more quickly retire its obligations without affecting the amount of ongoing programmatic funding it provides to school districts and community colleges.

The Governor makes several adjustments to the minimum guarantee to reflect the shift of RDA revenues to school districts and community colleges. Below, we: (1) provide an overview of how LPT shifts can affect the Proposition 98 minimum guarantee, (2) discuss how the dissolution of RDAs is affecting schools and colleges, (3) describe the Governor’s approach to making related Proposition 98 adjustments, and (4) provide short– and long–term recommendations for making these RDA–related adjustments.

Addressing the Effect of LPT Shifts on the Minimum Guarantee. Over the past two decades, the state has made numerous shifts in the allocation of property taxes among cities, counties, special districts, school districts, and community college districts. In some years, these shifts can unintentionally increase or decrease the Proposition 98 minimum guarantee. To ensure that these shifts have no effect on the total amount of funding schools and colleges receive, the state “rebenches” the Proposition 98 minimum guarantee. (The state also has rebenched the minimum guarantee when certain programs have been shifted into or out of Proposition 98. No program rebenchings, however, are proposed for the budget year.)

State Rebenches by Adjusting “Test 1” Factor. The Proposition 98 minimum guarantee is determined by one of three formulas, commonly called tests. Each of these tests is calculated using a somewhat different set of inputs. Test 1 requires the state to provide roughly 40 percent of General Fund revenues to Proposition 98 programs. When Test 1 is operative, schools and colleges effectively receive LPT revenues on top of their General Fund allocation. Thus, when Test 1 is operative, changes to LPT revenues affect total Proposition 98 funding. To ensure that policy–driven property tax shifts do not affect total Proposition 98 funding in these years, the state adjusts the specific percentage of General Fund revenues used in making the Test 1 calculation (this is commonly referred to as “rebenching the Test 1 factor”). Because the rebenching only affects the Test 1 factor, the state’s minimum guarantee is not always directly affected by the adjustment. In some cases, for example, Test 2 or Test 3 would be operative even if the Test 1 factor were not adjusted. (The Test 2 and Test 3 calculations are not affected by changes in property taxes, so no rebenching adjustments are needed for these tests.) In other cases, however, Test 1 would be operative with or without the adjustment. In these cases, rebenching has a direct effect on the minimum guarantee.

State Has Rebenched in Various Situations. The state has rebenched the Test 1 factor due to various property tax shifts over the past 20 years. In some instances, the state has rebenched to achieve General Fund savings. For example, in 1993–94, the state required cities, counties, and special districts to permanently shift $2.6 billion in property tax revenues to schools and community colleges. To ensure the shift in revenue provided state savings and did not increase total Proposition 98 funding, the state reduced the Test 1 factor. In other instances, the state has rebenched to avoid possible reductions to Proposition 98 funding. In 2004–05, for example, the state temporarily shifted roughly $1 billion in property tax revenues from schools and colleges to cities and counties as part of a complicated transfer associated with paying off the state’s Economic Recovery Bonds. To ensure the shift did not reduce total school and college funding, the state increased the Test 1 factor. Because the shift is temporary (it will likely expire in 2017), the state will rebench again when the transfer ends.

Dissolution of RDAs Shifts LPT Revenues to Schools and Colleges. In recent years, schools and colleges have been affected by LPT shifts related to RDAs. The state authorized local agencies to create RDAs in 1945 to address urban blight in certain “project areas.” When an RDA project area was created, most of the growth in property tax revenue from the project area was distributed to the city or county’s RDA as “tax increment revenues” instead of being distributed as general purpose revenues to other local agencies serving the area. In 2011–12, RDAs statewide received roughly $5 billion in tax increment revenues. As a result of legislation adopted in 2011, all RDAs statewide were dissolved on February 1, 2012. In most cases, the city or county that created the RDA is managing its dissolution as a successor agency. The successor agencies are required to use tax revenues previously provided to RDAs to continue to pay the former RDA’s outstanding financial obligations. After these obligations are paid, the remaining revenues—known as residual RDA revenues—are distributed based on existing property tax allocation laws to cities, counties, special districts, schools, and colleges. Successor agencies also are required to allocate former RDA cash assets to local agencies serving the area. When all RDA debts have been repaid, tax increment revenues no longer will be separated from other property tax revenues and instead be distributed to local agencies using existing property tax allocations. Once all shifts have been completed, schools and community colleges are expected to receive a total of roughly $2.5 billion in additional property tax revenues.

State Rebenches for Redevelopment–Related Revenues in 2011–12 and 2012–13. The minimum guarantee in 2011–12 and 2012–13 was rebenched to account for the shift of property tax revenues to schools and colleges from the dissolution of RDAs. Given both 2011–12 and 2012–13 are Test 1 years, this adjustment is allowing the state to achieve dollar–for–dollar General Fund savings for the transfers of ongoing residual RDA property tax receipts and one–time RDA cash assets. The 2012–13 Budget Act assumed school districts and community colleges would receive $1.7 billion from residual RDA revenues and $1.5 billion from cash assets in 2011–12 and 2012–13, for total General Fund savings of $3.2 billion.

Redevelopment Revenues Face Significant Uncertainty. For a number of reasons, the amount of revenue shifted to schools and colleges from RDAs in the near term is subject to a substantial amount of uncertainty. Several key steps in the dissolution process have yet to occur, resulting in little reliable information on a large category of former RDA assets. Some RDA successor agencies also have not met anticipated timelines for performing certain procedures or have disputed Department of Finance findings regarding the availability of assets for distribution to schools, colleges, and other local governments. A number of pending lawsuits regarding RDA dissolution also could affect savings. In the long run, as RDA obligations are repaid and more funds are transferred to local agencies, the amount of revenues for schools and community colleges will increase. Due to these uncertainties, however, any estimates of RDA–related revenue for the next several years likely will change significantly as updated information becomes available.

Reduces RDA Savings Estimates by One–Third. The Governor’s budget reduces RDA revenue estimates by roughly one–third from the amounts assumed in the 2012–13 Budget Act. As Figure 6 shows, estimates of RDA–related revenues for 2012–13 decreased by $1.1 billion. For 2013–14, estimates of redevelopment–related revenues decreased by $494 million.

Figure 6

Lower Estimates of Redevelopment–Related Transfers to Schools and Colleges

(In Millions)

|

|

2012–13 Budget Act

|

2013–14 Governor’s Budget

|

Difference

|

|

2011–12

|

|

|

|

|

Ongoing residual

|

$113

|

$147

|

$34

|

|

Cash assets

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

|

Totals

|

$113

|

$147

|

$34

|

|

2012–13

|

|

|

|

|

Ongoing residual

|

$1,676

|

$784

|

–$893

|

|

Cash assets

|

1,479

|

1,302

|

–177

|

|

Totals

|

$3,155

|

$2,086

|

–$1,070

|

|

2013–14

|

|

|

|

|

Ongoing residual

|

$1,011

|

$559

|

–$452

|

|

Cash assets

|

600

|

558

|

–42

|

|

Totals

|

$1,611

|

$1,117

|

–$494

|

|

Totals Through 2013–14

|

|

|

|

|

Ongoing residual

|

$2,800

|

$1,490

|

–$1,310

|

|

Cash assets

|

2,079

|

1,860

|

–219

|

|

Totals

|

$4,879

|

$3,350

|

–$1,529

|

Updates One Rebenching but Locks in Another. As part of his budget package, the Governor updates the 2011–12 and 2012–13 rebenching adjustments to reflect the revised estimates of one–time RDA cash assets and ongoing residual RDA revenues. For 2013–14, the Governor also updates his RDA cash asset rebenching to reflect new revenue estimates but does not update the rebenching for ongoing residual RDA revenues, effectively locking in the rebenching adjustment at the 2012–13 level, regardless of actual RDA revenues transferred moving forward.

RDA Estimates Too Uncertain to Make Rebenching Permanent. Given the uncertainty regarding redevelopment receipts over the next several years, the Governor’s proposal to lock in the associated rebenching adjustment is premature. Over the next several years, schools and colleges are expected to receive substantially more property tax revenues as RDA debts are repaid. If the state locks in its rebenching adjustment at 2012–13 levels, the Test 1 calculation would not be properly adjusted to ensure that RDA revenues have no fiscal effect on schools and colleges. This approach also would result in higher state costs in future years.

Recommend Annually Updating Rebenching Adjustment in Near Term. Given the uncertainty of redevelopment revenues, we recommend the Legislature update its rebenching, as needed, to account for the increase in revenues transferred to schools. This approach would ensure Proposition 98 funding reflects more accurately the sizeable shift of LPT receipts to schools that is expected to occur over the next several years. It also would generate an associated reduction in state General Fund costs.

Adopt Different Long–Term Solution. To rebench accurately for RDA dissolution, the state must calculate the resulting increase in property tax revenues for schools and colleges. In the initial years after RDA dissolution, the state easily can calculate this effect based on the amount of residual RDA revenues annually transferred to schools and community colleges by the county auditor, as county auditors are required to keep separate accounting of tax revenues formerly transferred to RDAs. In future years, however, when RDA debts are fully repaid, schools and community colleges will not receive these funds as residual RDA revenues. Instead, they will receive these revenues along with all other property tax receipts, making it virtually impossible for the state to calculate the net benefits of RDA dissolution. To avoid these issues, we recommend the Legislature adopt a different long–term rebenching approach. One possible approach would lock in the rebenching adjustment when RDA revenues have stabilized (likely within the next decade). Alternatively, the state could create a multiyear rebenching schedule to adjust the Test 1 factor. The schedule would gradually adjust the Test 1 factor to reflect assumptions about the increase in property tax revenues transferred to schools and colleges as RDA obligations are repaid.

Passed by the voters in November 2012, Proposition 39 increases state corporate tax (CT) revenues and requires for a five–year period, starting in 2013–14, that a portion of these revenues be used to improve energy efficiency and expand the use of alternative energy in public buildings. The Governor’s 2013–14 budget counts all Proposition 39 revenues toward the Proposition 98 minimum guarantee and allocates all associated energy–related funding to school and community college districts. Below, we (1) provide an overview of Proposition 39 and its requirements, (2) describe the Governor’s proposed treatment of Proposition 39 revenues and the proposed allocation of such revenues, (3) raise many serious concerns with the Governor’s approach, and (4) offer an alternative approach.

Proposition 39 Raises Additional State Revenues and Designates Half for Energy Projects. Proposition 39 requires most multistate businesses to determine their California taxable income using a single sales factor method. (Previously, state law allowed such businesses to pick one of two different methods to determine the amount of taxable income associated with California and taxable by the state.) This change has the effect of increasing state CT revenue. For a five–year period (2013–14 through 2017–18), the proposition requires that half of the annual revenue raised from the measure—up to $550 million—be transferred to a new Clean Energy Job Creation Fund to support projects intended to improve energy efficiency and expand the use of alternative energy. Specifically, the measure requires that such funds maximize energy and job benefits by supporting (1) eligible projects at public schools, colleges, universities, and other public buildings and (2) public–private partnerships and workforce training related to energy efficiency and alternative energy. Proposition 39 also requires that funded programs be coordinated with CEC and the California Public Utilities Commission (CPUC) to avoid duplication and leverage existing energy efficiency and alternative energy efforts. In addition, the proposition states that the funding be appropriated only to agencies with established expertise in managing energy projects and programs.

Proposition 39 Revenues Can Increase Proposition 98 Minimum Guarantee. Because the Proposition 98 minimum guarantee can grow with increases in state General Fund revenues (including those collected from state corporate income taxes), the revenues generated by Proposition 39 can increase the state’s Proposition 98 funding requirements.

Existing State Energy Efficiency and Alternative Energy Programs. Currently, California maintains over a dozen major programs (such as Bright Schools and the Energy Conservation Program) that are intended to support the development of energy efficiency and alternative energy in the state. (For a more detailed description of these programs, please see our recent report,

Energy Efficiency and Alternative Energy Programs.) Over the past 10 to 15 years, the state has spent a combined total of roughly $15 billion on such efforts. The various energy programs are administered by multiple state departments, including CEC and CPUC, as well as the state’s investor–owned utilities (IOUs). Funding from these programs have been allocated to various entities, including many schools and community college districts. In determining which specific projects to fund, the CEC and the IOUs provide energy audits to evaluate what types of upgrades would result in the most cost–effective energy savings. These programs also provide financing options for these upgrades.

Counts All Proposition 39 Revenue in Proposition 98 Calculation. The administration projects that Proposition 39 will increase state revenue by $440 million in 2012–13 and $900 million in 2013–14. The Governor’s budget plan includes all revenue raised by Proposition 39 in the Proposition 98 calculation, which has the effect of increasing the minimum guarantee by $426 million in 2012–13 and an additional $94 million (for a total increase of $520 million) in 2013–14. In both 2012–13 and 2013–14, the Governor proposes to fund Proposition 98 at his estimate of the minimum guarantee.

Designates All $450 Million for School and Community College Energy Projects. The Governor proposes to allocate all Proposition 39 energy–related funding over the next five years exclusively to school and community college districts ($450 million in 2013–14 and an estimated $550 million annually for the next four years). For 2013–14, the Governor’s budget proposes to provide school districts with $400.5 million and community college districts with $49.5 million. The Governor proposes to classify this spending as Proposition 98 expenditures that count toward meeting the minimum guarantee. The administration proposes to appropriate the funding for school districts to the California Department of Education (CDE) and the funding for community colleges to the CCC Chancellor’s Office. The budget also proposes to provide CDE with one permanent position ($109,000) to help implement and oversee the Proposition 39 program. The Governor proposes no additional positions for the CCC Chancellor’s Office for the administration of Proposition 39.

Allocates Funds on Per–Student Basis. The administration’s proposal would require that CDE and the Chancellor’s Office allocate funding to districts on a per–student basis. In 2013–14, school districts and community college districts would receive $67 and $45 per student, respectively. The CDE and Chancellor’s Office would issue guidelines for prioritizing the use of the funds. The administration notes that CDE and the Chancellor’s Office could consult with CEC and CPUC in developing these guidelines. Upon project completion, school districts and community college districts would report their project expenditure information to CDE and the Chancellor’s Office, respectively.

We have many serious concerns with the Governor’s Proposition 39 proposal. Figure 7 summarizes these concerns, which we discuss in more detail below.

Figure 7

LAO Concerns With Governor’s Proposition 39 Proposal

|

|

- Questionable Treatment of Proposition 39 Revenues

|

- • Varies from our longstanding view of Proposition 98.

|

- • Could lead to greater manipulation of the minimum guarantee.

|

- Governor’s Proposed Allocation Method Limits Benefits

|

- • Excludes many eligible projects.

|

- • Fails to account for energy consumption differences.

|

- • Allocates funding inefficiently.

|

- • May not guarantee return on investment.

|

- • Does not account for significant past investments in K–14 facilities.

|

- • Fails to sufficiently leverage existing programs and experience.

|

Varies Significantly From Our Longstanding View of Proposition 98. As described above, the Governor counts all Proposition 39 revenue, including the revenue required to be spent on energy–related projects, toward the Proposition 98 calculation. This is a serious departure from our longstanding view, which we developed over many years with guidance from Legislative Counsel, of how revenues are to be treated for the purposes of Proposition 98. It also is directly contrary to what the voters were told in the official voter guide as to how the revenues would be treated. Based on our view, revenues are to be excluded from the Proposition 98 calculation if the Legislature cannot use them for general purposes—typically due to restrictions created by a voter–approved initiative or constitutional amendment. The voter guide reflected this longstanding interpretation by indicating that funds required to be used for energy–related projects would be excluded from the Proposition 98 calculation. Had the Governor used the approach described in the voter guide, the minimum guarantee would be roughly $260 million lower in 2013–14 than the amount specified in his budget proposal. (This approach would have no effect on the calculation of the 2012–13 minimum guarantee.)

Could Lead to Greater Manipulation of the Minimum Guarantee. The Governor’s approach assumes that all tax revenues deposited directly into the General Fund must be included in the Proposition 98 calculation, whereas any tax revenues deposited directly into a special fund must be excluded from the calculation. This approach easily could result in greater manipulation of the Proposition 98 minimum guarantee. The state could, for example, require that all sales tax revenues be deposited directly into a special fund rather than the General Fund, thereby excluding the revenues from the Proposition 98 calculation. These types of accounting shifts could undermine the meaningfulness of the guarantee and render it effectively useless in setting a minimum funding requirement for schools and community colleges. By focusing on allowable uses of funds, not whether the funds were deposited into this or that account, our view would prevent such manipulation. Under our view, revenues are excluded from the Proposition 98 calculation only if they are clearly removed from the Legislature’s control (typically by constitutional or voter–approved action).

Excludes Many Eligible Projects. By dedicating all of the Proposition 39 energy–related funding over the five–year period to school and community college districts, the Governor’s approach excludes consideration of other eligible projects that potentially could achieve a greater level of energy benefits. For example, large public hospitals that operate 24 hours a day, 7 days a week generally have a relatively large energy load. In contrast, schools typically are open for only part of the day and generally either closed or partially closed in the summer months.

Fails to Account for Energy Consumption Differences. A building’s energy consumption is largely affected by the climate in which it is located. For example, facilities located in cold climates will use more energy for heating, while facilities located in temperate climates generally use less energy for heating and cooling. These climate differences significantly impact what types of energy efficiency retrofits and upgrades will be most effective at reducing a particular facility’s energy consumption. All other factors being equal, conducting an energy efficiency upgrade on a facility that requires relatively more energy (versus a facility that uses less energy) will result in greater energy benefits. In addition, the size, design, and age of a facility affects its energy consumption. By providing funding to every school district and community college district on a per–student basis, the Governor’s proposal ignores these important factors and effectively limits the potential energy benefits that otherwise could be achieved with the Proposition 39 funding.

Allocates Funding Inefficiently. By distributing funding to districts on an annual, per–student basis, the Governor’s approach also likely would result in some school districts lacking enough funding to implement major energy–efficiency improvements in the first year of the program. For example, under the proposal, a small school district having 100 students would receive $6,700 in Proposition 39 funds in 2013–14. Such a small sum is unlikely to be sufficient to undertake comprehensive improvements for a facility. Given that the state has many small school districts (about 10 percent of districts have fewer than 100 students), this problem would be notable. To mitigate this concern, the Governor indicates that districts could carry over funding throughout the program’s five–year life to increase the total resources available for a project. This approach, however, would result in funds potentially remaining idle for several years instead of being used in a way that would immediately begin to achieve benefits.

May Not Guarantee Return on Investment. Proposition 39 requires that the total benefits of each project be greater than total costs over time. For energy efficiency projects, it can take several years before enough energy savings accumulate to offset the upfront investment. For example, replacing an outdated heating and cooling system with an energy–efficient model would likely require a significant upfront investment and take several years for the project’s savings to outweigh this investment. Under the Governor’s proposal, it is unclear what requirements would be put in place to ensure that facilities upgraded with Proposition 39 funds remain in use long enough for the benefits to outweigh the costs. This is a particular concern for the nearly half of school districts with declining enrollment. Given the corresponding reductions in need for space, these districts might close or sell facilities that had been improved with Proposition 39 funds prior to a project’s benefits outweighing its costs.

Does Not Account for Significant Past Investments in K–14 Facilities. Since 2002, voters have approved about $29 billion in state bonds and about $71 billion in local bonds for school facilities. Nearly all of the state bonds (and likely most of the local bonds) relate to new construction and modernization, with about $100 million of the state bonds specifically dedicated to green schools. During the same time, voters have approved about $3 billion in state bonds and about $24 billion in local bonds for facility improvements at the state’s community colleges. In addition, many schools and community colleges have received funding from the energy efficiency programs administered by CEC and the state’s IOUs. As a result of the decade–long $127 billion investment in K–14 facilities, as well as these other energy–specific programs, many school and community college buildings throughout the state have been newly built or modernized. As the state’s building codes incorporate a large number of energy efficiency provisions, many of these facilities are already very energy efficient. The Governor’s proposal, however, does not take into account the above state and local investments in energy–efficient facilities when allocating the Proposition 39 funds.

Fails to Sufficiently Leverage Existing Programs and Experience. The Governor’s proposal also does not take advantage of the state’s existing knowledge and administrative infrastructure regarding energy efficiency. For example, many of the state’s energy efficiency programs include some evaluation of a facility’s energy usage (such as from the energy audits that are provided through CEC and the IOUs) to ensure that the most cost–effective energy projects are funded. In addition, because the proposed budget would appropriate the funding to CDE and the Chancellor’s Office, the Governor’s proposal might not meet Proposition 39’s requirement that monies from the Clean Energy Job Creation Fund be appropriated only to agencies with established expertise in managing energy projects and programs. As a result of not coordinating Proposition 39 funding with the state’s other energy efficiency activities and not appropriating the funding to agencies with established expertise, the Governor’s approach makes comparing effectiveness across programs and evaluating the relative benefits of projects from a statewide basis difficult. (As we discussed in our recent report on energy programs, we believe a comprehensive strategy is needed for the state to meet its energy efficiency and alternative energy objectives.)

In view of the above concerns, we recommend an alternative treatment of Proposition 39 revenues for purposes of calculating the Proposition 98 minimum guarantee. In addition, we outline a specific set of recommendations that would help maximize the potential benefits of this new funding.

Exclude Energy–Related Funding From Proposition 98 Minimum Guarantee. Consistent with our view of how revenues are to be treated for the purposes of calculating the minimum guarantee, we recommend the Legislature exclude from the Proposition 98 calculation all Proposition 39 revenues required to be used on energy–related projects. Based on the administration’s revenue estimates, this approach would reduce the minimum guarantee by roughly $260 million. In addition, we recommend the Legislature reclassify the $450 million to be spent on energy–related projects as a non–Proposition 98 expenditure (though the state still could choose to spend these monies on schools and community colleges).

Alternative Increases Proposition 98 Operational Support by $190 Million. As Figure 8 shows, adopting our recommended approach would result in $190 million in additional operational Proposition 98 support for schools and community colleges. This amount is the net effect of two factors. On the one hand, by excluding some Proposition 39 revenue from the Proposition 98 calculation, the minimum guarantee falls by $260 million in 2013–14. On the other hand, by not using Proposition 98 funding for school energy projects, spending falls by $450 million relative to the Governor’s budget plan. Thus, maintaining spending at the revised minimum guarantee would result in an additional $190 million in operational funding. Under this approach, the $450 million still needs to be used for energy–related projects, and it could be used for schools and community colleges to the extent the basic provisions of Proposition 39 are met. From the state’s perspective, this approach increases total state costs by $190 million and, thus, could result in reduced spending on non–Proposition 98 General Fund programs.

Figure 8

Fiscal Effects of LAO Approach

(In Millions)

|

|

Governor

|

LAO

|

Difference

|

|

Proposition 98 Funding:

|

|

|

|

|

Operational funding for schools and community colleges

|

$55,750

|

$55,940

|

$190

|

|

Energy project funding, only schools and community colleges

|

450

|

—

|

–450

|

|

Subtotals, Proposition 98

|

($56,200)

|

($55,940)

|

(–$260)

|

|

Non–Proposition 98 Funding:

|

|

|

|

|

Energy project funding, all allowable projects including schools and community colleges

|

—

|

$450

|

$450

|

|

Total Spending

|

$56,200

|

$56,390

|

$190

|

Process for Allocating Funding Should Maximize Benefits. In order to ensure that the state meets the requirements of Proposition 39 and maximizes energy and job benefits, we recommend the Legislature adopt a different approach than that proposed by the Governor. Specifically, we recommend that it:

- Designate CEC as Lead Agency for Proposition 39 Energy Funds. We recommend the Legislature designate the CEC (whose primary responsibility is energy planning) as the lead agency for administering—in consultation with the CPUC and other experienced entities—the energy funds authorized in Proposition 39. This would help ensure that the relative benefits of each project can be considered from a statewide perspective.

- Use Competitive Grant Process Open to All Public Agencies. We also recommend the Legislature direct CEC to develop and implement a competitive grant process in which all public agencies could apply for Proposition 39 funding on a project–by–project basis. In order to ensure that the state maximizes energy benefits, this competitive process should consider and weigh all factors that affect energy consumption. The CEC could create a tiered system that categorizes facilities based on a high–, medium–, and low–energy intensity or need. Based on that categorization, funding should be provided to facilities with the greatest relative need in coordination with other existing energy programs.

- Require Applicants to Provide Certain Energy–Related Information. To qualify for grant funding and assist CEC in evaluating potential projects, we recommend that applicants first have an energy audit to identify the cost–effective energy efficiency upgrades that could be made, similar to the types of audits currently provided through CEC and the IOUs. As part of the application, facilities also should provide information regarding the climate zone, size, design, and age of a building.

We recognize that the Legislature may be interested in allocating all or a portion of the Proposition 39 energy funding to support energy projects at schools and community colleges. To the extent the Legislature chooses to prioritize such projects, we believe that our recommended process would be a more effective approach in meeting the goals of Proposition 39 than allocating funds to school and community college districts on a per–student basis as proposed by the Governor.

The Governor’s budget includes several proposals involving education mandates. Most notably, the Governor proposes to add two large mandates and $100 million to the mandates block grant for schools. In addition, he proposes to modify the state requirements for a special education mandate to align them more closely with federal requirements. The Governor’s budget also newly suspends six education mandates and includes funding for a new mandate related to pupil suspensions and expulsions. Below, we (1) provide some background on education mandates, (2) describe and asses the Governor’s mandate proposals, and (3) make various related recommendations.

Five Major Problems With Mandate Reimbursements. In 1979, voters passed Proposition 4, which added a requirement to the California Constitution that local governments—including school and community college districts—be reimbursed for new programs or higher levels of service the state imposes on them. Afterwards, the state created an elaborate legal and administrative process for determining whether new requirements constitute mandates and reimbursing associated mandate claims. Over the years, our office has identified numerous problems with this system. Specifically, we have found that (1) many mandates do not serve a compelling purpose, (2) mandated costs are often higher than expected, (3) reimbursement rates vary greatly by district, (4) the reimbursement process rewards inefficiency, and (5) the reimbursement process ignores program effectiveness.

Block Grant Intended to Address Some of the Problems With Reimbursement System. To address some of the problems identified above, the Legislature and Governor created a block grant as an alternative method of reimbursing school and community college districts. Instead of submitting detailed claims listing how much time and money was spent on mandated activities, districts now can choose to receive funding through the block grant. As listed in Figure 9, the state included 43 mandates (and $167 million) in the block grant for schools and 17 mandates (and $33 million) for community colleges. Block grant funding is allocated to participating local educational agencies (LEAs) on a per–student basis that varies by type of LEA, as different mandates apply to each type. Charter schools receive $14 per student, while school and community college districts receive $28 per student. The COEs receive $28 for each student they serve directly, plus an additional $1 for each student within the county. (The $1 add–on for COEs is intended to cover mandated costs largely associated with oversight activities, such as reviewing district budgets.) Due to concerns regarding the state’s constitutional obligation to reimburse districts for mandated costs, the state also retained the existing mandates claiming process for districts not opting into the block grant.

Figure 9

Mandates Included in Block Grants

2012–13

|

Schools Block Grant

|

|

Absentee Ballots

|

Juvenile Court Notices II

|

|

Academic Performance Index

|

Law Enforcement Agency Notificationc

|

|

Agency Fee Arrangements

|

Mandate Reimbursement Process I and II

|

|

AIDS Prevention/Instruction

|

Notification of Truancy

|

|

Annual Parent Notificationa

|

Open Meetings/Brown Act Reform

|

|

CalSTRS Service Credit

|

Physical Performance Tests

|

|

Caregiver Affidavits

|

Prevailing Wage Rate

|

|

Charter Schools I, II, and III

|

Pupil Expulsion Appeals

|

|

Child Abuse and Neglect Reporting

|

Pupil Expulsions

|

|

COE Fiscal Accountability Reporting

|

Pupil Health Screenings

|

|

Collective Bargaining

|

Pupil Promotion and Retention

|

|

Comprehensive School Safety Plans

|

Pupil Safety Notices

|

|

Criminal Background Checks I and II

|

Pupil Suspensions

|

|

Differential Pay and Reemployment

|

School Accountability Report Cards

|

|

Expulsion of Pupil: Transcript Cost for Appeals

|

School District Fiscal Accountability Reporting

|

|

Financial and Compliance Audits

|

School District Reorganization

|

|

Habitual Truants

|

Student Records

|

|

High School Exit Examination

|

Teacher Notification: Pupil Suspensions/Expulsionsd

|

|

Immunization Recordsb

|

The Stull Act

|

|

Interdistrict Attendance Permits

|

Threats Against Peace Officers

|

|

Intradistrict Attendance

|

|

|

Community Colleges Block Grant

|

|

Absentee Ballots

|

Mandate Reimbursement Process I and II

|

|

Agency Fee Arrangements

|

Minimum Conditions for State Aid

|

|

Cal Grants

|

Open Meetings/Brown Act Reform

|

|

CalSTRS Service Credit

|

Prevailing Wage Rate

|

|

Collective Bargaining

|

Reporting Improper Governmental Activities

|

|

Community College Construction

|

Sex Offenders: Disclosure by Law Enforcement

|

|

Discrimination Complaint Procedures

|

Threats Against Peace Officers

|

|

Enrollment Fee Collection and Waivers

|

Tuition Fee Waivers

|

|

Health Fee Elimination

|

|

Block Grant Participation Relatively High in First Year of Program. As shown in Figure 10, most school districts and COEs and virtually all charter schools and community college districts opted to participate in the block grant. These LEAs represent 86 percent of K–12 students and 96 percent of community college students. Charter schools likely opted in at such high rates because they have been deemed ineligible for mandate reimbursements through the claims process. The lower participation rate for school districts and COEs could be due to various reasons. Some might have continued claiming for reimbursements because they calculated that they could receive more money that way (because of very high claiming costs compared to others due to differences in salaries and staffing). Other districts and COEs might not have participated due to transitional issues, such as terminating contracts with companies that had been providing reimbursement services for them.

Figure 10

Most Local Educational Agencies (LEAs) Opted Into Mandates Block Grants

2012–13

|

|

Number in Block Grant

|

Total

|

Percent in Block Grant

|

Corresponding ADAa

|

|

Community colleges

|

67

|

72

|

93%

|

96%

|

|

Charter schools

|

877

|

946

|

93

|

91

|

|

School districts

|

634

|

943

|

67

|

86

|

|

County offices

|

35

|

58

|

60

|

87

|

Block Grant Left Some Issues Unanswered. Moving forward, the state left unanswered how to include new mandates in the block grant. Specifically, the state did not address at what point in the mandate determination process a new mandate would be included in the block grant. The state also did not address how much funding to provide for new mandates. (Though the block grant in 2012–13 provided levels of funding that were roughly similar to how much schools and community colleges had been claiming for the included mandates, the amounts were not directly tied to claims costs.) Additionally, the state did not address whether adjustments would be made to the block grant in the future to account for any changes in costs (such as for inflation).

Science Courses Required to Graduate From High School. In 1983, the state added greater specificity to high school graduation requirements, including a provision requiring two years of science (as well as three years of English, three years of social science, two years of mathematics, two years of physical education, and one year of visual or performing arts or foreign language). Though none of the other 12 high school graduation requirements became state reimbursable mandates, the Commission on State Mandates (CSM)—the quasi–judicial body that makes mandate determinations—determined the second year of science to be a mandate. Specifically, CSM found that district costs could increase to (1) remodel or acquire new space for additional science courses, and (2) staff and supply equipment for them. At the same time, CSM found that offsetting savings could result from reductions in non–science courses and any other funds districts receive to pay for the mandate could be applied as offsets. Based on a sample of districts, CSM estimated costs for the mandate would be a few million dollars annually.

Several Lawsuits Over Graduation Requirements Mandate. After districts began claiming reimbursements, the state became involved in several lawsuits over many years regarding the mandate. In one case, the courts limited the state’s ability to apply offsetting savings from reductions in non–science courses by essentially requiring the state to find direct evidence that the additional science course led to a reduction in other courses. Two additional lawsuits still remain unresolved. In the first case, the state is suing CSM over the specific reimbursement methodology it adopted to calculate the costs of the mandate. The state believes the methodology adopted by CSM does not meet statutory requirements. The methodology also significantly increases state costs—both prospectively and retrospectively. In the second case, school districts are suing the state regarding whether revenue limits are an allowable offset for covering science teacher salary costs. The Legislature amended state law to require this offset a few years ago. (School districts recently amended this second lawsuit to include a charge that the schools mandate block grant itself was illegal. Given the amendment, the suit essentially restarts a process that can take several years to complete.)

Significant Uncertainty Over Reimbursable Costs of Graduation Requirements Mandate. Currently, districts are claiming $265 million annually for the Graduation Requirements mandate (more than what they claim for all other mandates combined). These costs, however, are based on the reimbursement methodology that the state believes to be flawed. The costs also have not been offset with revenue limits as required under state law. (The CSM has not yet included the revenue limits offset in its reimbursement guidelines due to the pending litigation.) If the state succeeds in having the reimbursement methodology changed and the revenue limits offset applied, reimbursable claims would be significantly less than what districts are now claiming. Due to this uncertainty, the state neither included the mandate in the block grant last year nor provided any funding for reimbursement claims.

Mandate Requires Planning and Other Activities for Certain SWDs. In 1990, the Legislature enacted a statute directing the Superintendent of Public Instruction and the State Board of Education (SBE) to implement regulations for how districts should respond when a student with a disability exhibits behavioral problems. The SBE subsequently adopted regulations requiring (1) a “functional analysis assessment” of the student’s behavior, (2) the development of a positive BIP, (3) the development of emergency intervention procedures, and (4) a few other related activities. The regulations also prohibited certain types of interventions (such as seclusion and restraints). After these regulations were issued, CSM found these activities to be a reimbursable mandate.

Also Significant Uncertainty Over Costs for BIP Mandate. The BIP mandate was not included in the block grant last year nor was any money provided for reimbursement claims since districts are not yet filing for reimbursement. Though the mandate dates back over two decades, various legal challenges and settlement negotiations delayed CSM’s adoption of reimbursement guidelines until just last month. At this time, it is still unclear how much districts will claim for the mandate. Based on the reimbursement guidelines adopted by CSM, statewide claims could total $65 million annually. The reimbursement guidelines require that these claims be offset, however, by special education funding specifically designated in state law for the BIP mandate. Enough special education funding is available to offset virtually all claims. Uncertainty regarding the offset exists, however, because the state is currently being sued in court over it as part of the same lawsuit regarding the offset for the Graduation Requirements mandate.

Adds Two Mandates and $100 Million to Block Grant. The Governor proposes to include both the second science course and BIP mandates in the block grant for schools. He further proposes to increase the block grant by a total of $100 million to account for the addition of the two mandates. Given the Governor has a separate proposal that would reduce BIP costs significantly (as discussed below), it appears that most of this $100 million augmentation would relate to the second science course mandate. The increase to the block grant would result in a corresponding increase in the per–student rate for school districts and COEs from $28 to $47 and for charter schools from $14 to $23.

Modifies Requirements for BIP. The Governor also proposes to modify several of the state’s BIP requirements to make them less prescriptive. For example, districts no longer would be required to use specific assessments and specific behavioral interventions. This would make state BIP requirements conform with current federal BIP requirements, thereby eliminating associated state reimbursable mandate costs. The Governor’s proposal, however, retains a few state requirements in excess of federal requirements. For example, state requirements would continue to prohibit certain types of interventions as well as prescribe certain activities related to emergency interventions. As a result of these changes, the Governor estimates BIP mandate costs would drop to $7 million annually.

Suspends Six Additional Mandates. The Governor’s budget continues to suspend the same education mandates in 2013–14 that were suspended in 2012–13. He further proposes to suspend six additional education mandates to conform with the approach taken on these mandates for local governments. Figure 11 provides a description of these mandates, their current status, and the Governor’s proposed changes for 2013–14.

Figure 11

Governor Proposes to Suspend Six Mandates That Apply to Local Educational Agencies (LEAs)

|

Mandate

|

Included in Block Grant?

|

|

Suspended for Local Governments?

|

|

2012–13 Budget

|

Governor’s Proposal

|

2012–13 Budget

|

Governor’s Proposal

|

|

Absentee Ballots. Requires that absentee ballots be provided to any eligible voter upon request.

|

Yes

|

No

|

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

|

Brendon Maguire Act. Requires a special election (or the reopening of nomination filings) when a candidate for office dies within a specified time prior to an election.

|

Noa

|

No

|

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

|

California Public Records Act. Requires the disclosure of agency records to the public upon request. Also requires agencies to assist the public with their requests.

|

Nob

|

No

|

|

No

|

Yes

|

|

Mandate Reimbursement Process I and II: Requires reimbursement for the costs of (1) filing initial mandate test claims, if found to be a mandate, and (2) filing annual mandate reimbursement claims.

|

Yes

|

No

|

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

|

Open Meetings/Brown Act Reform. Requires local governing boards to post meeting agendas and perform other activities related to board meetings.

|

Yes

|

No

|

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

|

Sex Offenders: Disclosure by Law Enforcement Officers. Requires law enforcement to obtain, maintain, and verify certain specific information about sex offenders.

|

Yes

|

No

|

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Includes Funding for Claims for New Pupil Suspension/Expulsion Mandate. Lastly, the Governor’s budget provides funding for a new mandate related to pupil suspensions and expulsions. (The Governor does not identify any changes to the block grant related to the mandate.) This mandate relates to an existing mandate requiring districts to suspend or expel students for committing certain offenses. The reimbursable costs are largely attributable to expulsion and suspension hearings, including appeals. The new mandate pertains largely to offenses not included within the purview of the original mandate. For example, the new mandate includes the requirement that a school board expel a student who brandishes a knife at another person.

Block Grant Increase Could Be Significantly More or Less Than Claims for Science Course and BIP Mandates. Given the uncertainty regarding the costs of the Graduation Requirements and BIP mandates, it is difficult to assess whether $100 million is an appropriate amount to add to the block grant. On the one hand, if the state were to lose all the various lawsuits involving these mandates, then the claims for the two mandates combined could be over $300 million annually. On the other hand, if the state were to prevail in court, then claims for the two mandates likely would be almost entirely offset with Proposition 98 funding. From a state perspective, this means that the block grant augmentation potentially is too large and the state might be “overpaying.” From a district perspective, this means that the block grant augmentation potentially is too small. In that case, some districts might view this as a disincentive to participate in the block grant.

Graduation Requirements Mandate Also Raises Serious Distributional Concerns. Because the mandates block grant is distributed on a uniform per–student basis, districts that serve different grade spans receive the same rate. For example, an elementary district receives the same $28 per–student rate as a high school district. The Graduation Requirements mandate raises serious distributional concerns since the mandate is so costly and applies only to high schools. We estimate about $63 million of the proposed increase for the mandate would be distributed to districts for students not in high school. In effect, many districts would receive a substantial amount for a mandate that does not apply to them. These distributional issues would alter the incentives districts have to participate in the block grant (either on a continuing basis or for the first time).

Current Law Approach to Offset Costs Reasonable. While we understand the Governor’s desire to address the two mandate’s costs, we think the existing offset language for both mandates already provides a reasonable approach. Notably, the state has been successful in the past using offsets for several other education and local government mandates. Moreover, in the case of BIP, CSM has already included the offset in its guidelines for reimbursements. Though CSM has not yet included the offset for Graduation Requirements, we believe a compelling case can be made to consider revenue limits an offset for this mandate for the following reasons.

- The State Did Not Require Districts to Lengthen School Day. When the state added specificity to high school graduation requirements in 1983, the Legislature did not believe costs would increase notably, as no change had been made to the length of the school day. Furthermore, virtually all local teacher contracts do not pay science teachers higher salaries than other teachers, such that a district could not reasonably make a claim that the second science course resulted in higher compensation costs. Though the state’s ability to automatically apply offsetting savings by assuming reductions in non–science courses has been limited by the courts, the courts noted that offsetting savings could exist.

- Revenue Limits Pay for Teacher Salaries and Other Graduation Requirements. Revenue limit funding is the state program most closely aligned with paying teacher compensation, with revenue limit funding covering the vast majority of teacher compensation costs. In addition, the state effectively uses revenue limit funding to cover all the other high school graduation requirements that it established at the same time as the second science course requirement. This funding is available for districts to cover costs for the second science course.

Aligning State and Federal BIP Requirements Would Increase Flexibility and Reduce Costs. The Governor’s proposal to better align state and federal BIP requirements has several positive features. First, the proposal recognizes that since the state enacted its BIP requirements over 20 years ago, many changes have been made to federal law that strengthen protections for all SWDs. As a result, the requirements in state law provide relatively few additional benefits. Moreover, state law is more prescriptive in terms of the types of assessments and BIPs that districts must develop, whereas federal law allows for a broader spectrum of options. At the same time, the Governor’s proposal retains a few key state requirements that offer stronger protections than federal law, such as the prohibition on using emergency interventions that involve physical discomfort. Finally, the Governor’s proposal has the advantage that it would significantly reduce the associated mandate costs.

Some Education Mandates Proposed for Suspension Similar to Local Government Mandate . . . Among the six mandates the Governor proposes to suspend, four (Brendon Maguire Act, Absentee Ballots, California Public Records Act, and Sex Offenders: Disclosure by Law Enforcement Officers) relate closely to the equivalent local government mandates. To the extent applicable, the state generally applies the same policy across local government agencies; otherwise, the state could adopt conflicting policies across different sectors of government. Absent a clear rationale for treating agencies differently, similar treatment ensures consistency in policy.

. . . But Others Have Education–Specific Considerations. The remaining two mandates have certain aspects unique to schools and community colleges. For the Mandate Reimbursement Process mandate, schools and community colleges have the option to participate in the block grant instead of filing claims for reimbursement. Therefore, suspending this mandate for LEAs would provide an even greater incentive for them to participate in the block grant instead of filing claims. For the Open Meetings/Brown Act Reform mandate, Proposition 30 (passed by the voters at the November 2012 election) eliminated the state’s obligation to pay for this mandate but did not eliminate the requirement that local agencies perform the activities. This has different implications for LEAs compared to other local governments. This is because the state is not required to suspend a mandate for LEAs in order to avoid paying down prior–year claims, as it is required to do for local governments.

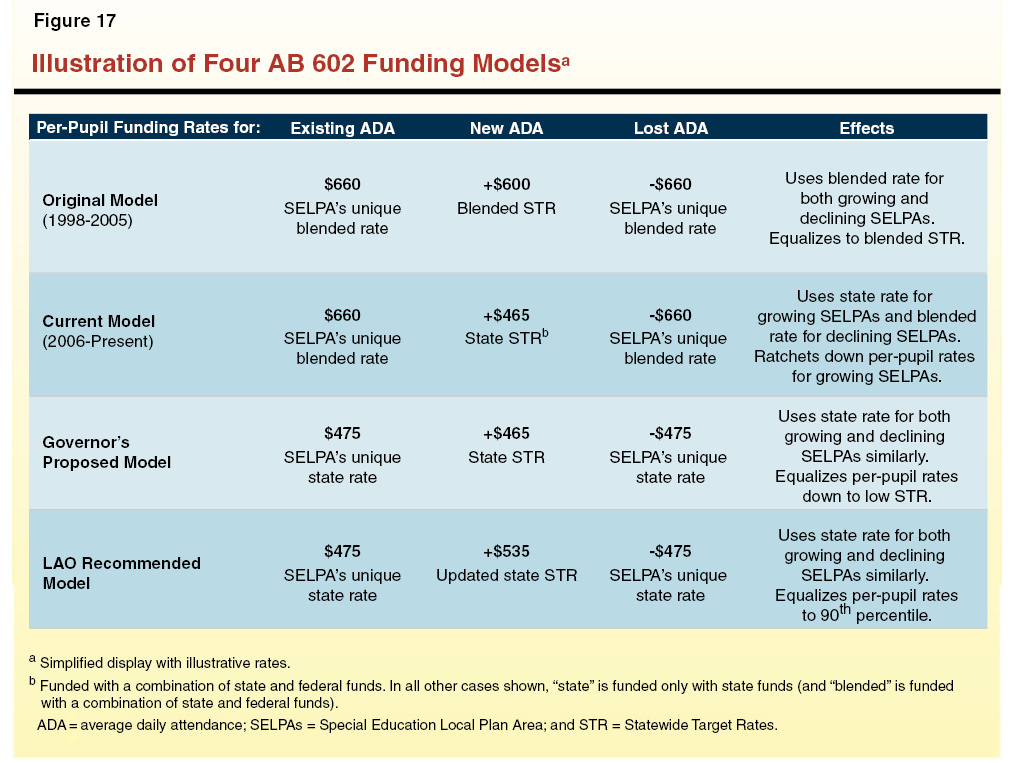

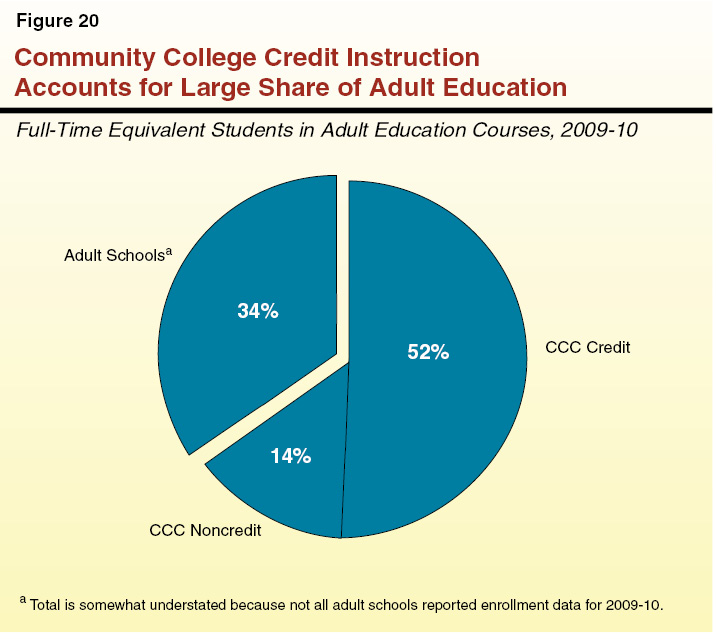

Several Considerations Regarding Pupil Suspensions/Expulsions Mandate. The CSM estimates that this mandate will cost a little over $1 million annually. On the one hand, it seems likely that districts would perform the mandated activities even if they were not required to do so under state law. For example, a student brandishing a knife at others would most likely be expelled by a school board. On the other hand, the mandate relates to pupil safety, which we believe generally provides a strong justification for retaining a state–mandated activity. Moreover, the mandate is closely related to an existing mandate that has been active for many years and was included in the block grant last year.