LAO Contacts

- Edgar Cabral

- Deputy Legislative Analyst: K-12 Education

- Michael Alferes

- Community Schools, Necessary Small Schools, Dual Enrollment

- Sara Cortez

- Differentiated Assistance, Science Performance Tasks, Kitchen Infrastructure

- Dylan Hawksworth-Lutzow

- Expanded Learning Opportunities Program, Teacher Residency, Reading Difficulties Screening

February 19, 2026

The 2026‑27 Budget

K‑12 Proposals

- Overview

- Community Schools

- Expanded Learning Opportunities Program

- Necessary Small Schools

- Differentiated Assistance

- Science Performance Tasks

- Teacher Residency Grant Program

- Dual Enrollment

- Kitchen Infrastructure and Training

- Reading Difficulties Screening

- Summary of LAO Recommendations

Summary

This brief provides our assessment and makes recommendations related to nine of the Governor’s K‑12 education budget proposals. Below, we provide a summary of our major recommendations. (A figure summarizing our recommendations for all proposals is at the end of this brief.)

Community Schools. The Governor’s budget proposes $1 billion ongoing Proposition 98 General Fund to support the community schools model. In addition to providing ongoing funding for about 2,500 schools that have already received one‑time community schools funding, about 3,700 new schools would be eligible for funding on an annual basis. Although the community schools model has been shown to have a variety of benefits for students, we have concerns about funding the model at such a large scale and establishing a new ongoing categorical program restricted for specific purposes. For these reasons, we recommend providing one‑time funding for additional rounds of community schools implementation grants. If the Legislature is interested in adopting the proposal as ongoing, we recommend several modifications to the Governor’s proposal.

Expanded Learning Opportunities Program. The Governor proposes $62.4 million ongoing Proposition 98 General Fund to set a minimum “Tier 2” rate at $1,800 per English learner or low‑income student, more than $200 higher than the 2024‑25 and 2025‑26 rates. If funds within the program are available, the rate could exceed $1,800. Although setting a minimum Tier 2 rate would eliminate much of the uncertainty districts face, allowing the rate to fluctuate above that level would provide increases that are not tied to program costs. In addition, we see no clear rationale for increasing the Tier 2 rate above the current levels. We recommend establishing a fixed Tier 2 rate at current Tier 2 levels.

Necessary Small Schools. The Governor’s budget proposes $30.7 million ongoing Proposition 98 General Fund to apply a 20 percent increase for necessary small schools—additional funding provided for geographically isolated schools. The Governor’s proposal has some merit given it would target districts that likely face greater cost pressures from operating very small schools in geographically isolated parts of the state. However, the proposed 20 percent increase is not aligned with any particular assessment of cost and results in a significant difference in per‑student funding rates between schools above or below the upper thresholds of eligibility. If the Legislature is interested in adopting the proposal, it could consider providing a different level of funding based on its priorities. We also recommend modifying the proposal to avoid large differences in funding above and below the eligibility thresholds.

Differentiated Assistance. Under current law, local education agencies are identified for additional support, known as differentiated assistance, based on certain performance criteria. The Governor proposes an additional $13 million ongoing Proposition 98 General Fund to adopt a new formula for differentiated assistance and expand the intended use of these funds. The Governor also proposes changes to the timing and frequency of differentiated assistance. These changes are premature given they are intended to align with forthcoming updates to the performance criteria that must be adopted by July 15, 2026. We recommend rejecting these proposals, as they need to be evaluated in tandem with the updated performance criteria.

Overview

Budget Contains Nearly $9.7 Billion in New K‑12 Education Spending Proposals. Proposition 98 (1988) establishes a minimum funding requirement for schools and community colleges, commonly known as the minimum guarantee. The administration estimates that the guarantee has increased by nearly $21.7 billion compared with the June 2025 budget level. About half of this increase is attributable to 2026‑27, with smaller portions attributable to 2024‑25 and 2025‑26. The increase is primarily due to the administration’s higher General Fund revenue estimates. As Figure 1 shows, the Governor’s budget allocates $9.7 billion of the increase for new school spending—more than $5.9 billion for one‑time activities and $3.7 billion for ongoing augmentations. (The rest of the increase—$12 billion—is unavailable for several reasons, including the Governor’s proposal to delay some of the associated funding and deposits into the Proposition 98 Reserve.)

Figure 1

Governor’s Budget Has $9.7 Billion in School

Spending Proposals

(In Millions)

|

Ongoing |

|

|

Local Control Funding Formula COLA (2.41 percent) |

$1,893 |

|

Community schools |

1,000 |

|

Special Education |

509 |

|

COLA for select categorical programs (2.41 percent)a |

230 |

|

Expanded Learning Opportunities Program |

62 |

|

Necessary Small Schools |

31 |

|

COE funding to support districts and charter schools |

13 |

|

Charter School Facility Grant Program |

7 |

|

FCMAT salary adjustment |

1 |

|

California School Information Services |

1 |

|

Science performance tasks |

1b |

|

K‑12 High Speed Network |

1 |

|

Subtotal |

($3,749) |

|

One Time |

|

|

Discretionary block grant |

$2,796 |

|

Deferral paydown |

1,875 |

|

Learning Recovery Emergency Block Grant |

757 |

|

Teacher Residency Grant Program |

250 |

|

Dual enrollment |

100 |

|

Kitchen infrastructure and training |

100 |

|

Reading difficulties screening |

40 |

|

Wildfire‑related support for schools |

23 |

|

Subtotal |

($5,941) |

|

Total Proposals |

$9,690 |

|

aApplies to Special Education, State Preschool, Child Nutrition, Equity Multiplier, K‑12 Mandates Block Grant, Charter School Facility Grant Program, Foster Youth Services Coordinating Program, Adults in Correctional Facilities, American Indian Education Centers, Child and Adult Care Food Program, and American Indian Early Childhood Education. bReflects $890,000 ongoing, beginning in 2025‑26. |

|

|

COLA = cost‑of‑living adjustment; COE = county office of education; and FCMAT = Fiscal Crisis Management Assistance Team. |

|

Recommend the Legislature Build the School Budget Cautiously. In an earlier brief, The 2026‑27 Budget: Proposition 98 Guarantee and K‑12 Spending Plan, we analyzed the overall structure of the Governor’s plan and provided our assessment and recommendations. In that brief, we highlight that the Governor’s budget is based on revenue estimates that do not account for the current elevated risk of a stock market downturn. A significant downturn could reduce state revenues by tens of billions of dollars, and the Proposition 98 guarantee would decline about 40 cents for each $1 of lower revenue. We recommend the Legislature prepare for this possibility by being cautious about new spending commitments; building reserves and other tools to protect existing school programs; and identifying proposals it would be willing to delay, reduce, or reject if a decline occurs. We also recommend the Legislature set aside a significant portion of the new funding available in 2026‑27 for one‑time activities rather than ongoing increases. Taking these steps would help the Legislature protect its core priorities and maintain its chosen spending level over time.

Previous Brief Analyzed a Few Major K‑12 Proposals. In addition to analyzing the broader school spending plan, our previous brief also provided our assessment and recommendations for a few major proposals. We recommend prioritizing the proposed statutory cost‑of‑living adjustment (COLA) over other ongoing spending and funding the statutory COLA rate unless revenue estimates decline significantly by May, as these funds would help districts address the cost increases they face. In addition, we recommend the Legislature adopt the administration’s proposed increase for special education to address statewide increases in special education costs. (However, we recommend using a lower estimate of costs.) We also recommend the Legislature adopt the Governor’s three major one‑time proposals: funding the discretionary block grant ($2.8 billion), eliminating the existing payment deferrals ($1.9 billion), and restoring funding for the Learning Recovery Emergency Block Grant ($757 million). These proposals are reasonable approaches to address district costs and ease future budget pressures for schools and the state. Regarding the discretionary block grant, the Legislature could provide a different level of funding based on revised estimates of the guarantee.

This Brief Analyzes Other K‑12 Proposals. In this brief, we provide our analysis and recommendations related to nine other K‑12 proposals—five proposals for additional ongoing funding and four one‑time proposals. (We have no major concerns with the remaining spending proposals.) A figure summarizing our recommendations is at the end of this brief. On the “EdBudget” section of our website, we also post numerous tables with additional budget information.

Community Schools

Background

Community Schools Model Is a Strategy for Improving Student Outcomes and Well Being. The community schools model is intended to improve student outcomes by addressing many of the factors outside of the classroom that can have impacts on student engagement and learning. Compared to traditional public schools, community schools are more likely to proactively communicate with families and create opportunities for feedback, which can help schools better understand the academic and socioemotional needs of their students. In addition, community schools engage with other community‑based organizations and public agencies to identify services available to support students. The specific programs and changes that schools make as a result of implementing the model vary depending on the needs of students and resources available in the local community. For example, schools that identify high levels of anxiety among their student population may partner with a county agency or a local community organization to provide counseling services for students at the school site. Schools often rely on a coordinator that leads the efforts to implement the community schools model.

State Has Provided $4.1 Billion in One‑Time Funding for Implementation of Community Schools Model. Since 2021‑22, the state has provided $4.1 billion in one‑time Proposition 98 General Fund for the California Community Schools Partnership Program (CCSPP), a competitive grant program that supports the establishment and expansion of the community schools model. Out of the $4.1 billion provided, the state set aside $3.9 billion for schools to plan and implement the community schools model (Figure 2). To receive funding, local education agencies (LEAs)—school districts, county offices of education (COEs), and charter schools—applied for funding on behalf of eligible school sites. LEAs are able to retain the lesser of $500,000 or 10 percent of their total allocation to build capacity for supporting community schools across the LEA. The state also set aside $282 million for support and technical assistance. This included $140 million to provide grants up to $500,000 annually for COEs to support the coordination of services across grantees within their county, as well as $142 million for a statewide system of technical assistance. Under current law, all CCSPP funds are to be allocated by 2031‑32.

Figure 2

Community School Grant Types

(In Millions)

|

Grant Type |

Purpose |

Annual Grant |

Total |

|

Planning |

For schools to develop plans for implementing the community schools model. |

Up to $200,000 for two years. |

$83 |

|

Implementation |

For new and existing community schools to implement the community schools model. |

Up to $500,000 for five years. |

3,299a |

|

Extension |

To extend implementation for two years, beginning in 2027‑28. |

Up to $100,000 for two years. |

485 |

|

Total |

$3,867 |

||

|

aIncludes $204 million initially set aside for planning grants that were used for implementation grants. |

|||

State’s System of Technical Assistance Includes Nine COEs. The state’s system of technical assistance is composed of a lead technical assistance center, known as the State Transformational Assistance Center (S‑TAC), and eight Regional Technical Assistance Centers (R‑TACs). The S‑TAC is currently led by the Sacramento COE, in partnership with the University of California, Los Angeles Center for Community Schooling; Californians for Justice; and the National Education Association. The eight R‑TACs consist of the COEs from Fresno, Los Angeles, Monterey, Sacramento, San Bernardino, San Diego, Santa Clara, and Shasta. R‑TACs are tasked with providing a variety of supports to community schools, including professional development, models of practice, coaching, and related supports for implementing the community schools model. The S‑TAC and R‑TAC work closely with the California Department of Education (CDE) for implementation and evaluation of the program.

State Adopted a Community Schools Framework in 2022. To support implementation, the state adopted a Community Schools Framework in 2022 that outlines various aspects of the community schools model. For example, it specifies the community schools model has four pillars consistent with research: (1) integrated student support, such as on‑site mental and physical health care; (2) family and community engagement; (3) collaborative leadership and practice; and (4) extended learning time and opportunities, such as after school care and summer programs. Additionally, the framework specifies key roles that LEAs and the state have in supporting the community schools model. For example, the framework specifies that LEAs have a key role in developing partnerships with external organizations on behalf of their school sites and building systems to support continuous improvement of the community schools model. The framework also includes four best practices associated with successful community schools implementation:

- Community Asset Mapping and Gap Analysis. Engaging with school and community members to identify existing gaps in program services and resources, and engaging with educational partners to identify programs, services, or other resources within the local community that can support students.

- Community Schools Coordinator. Having a coordinator that is responsible for overall implementation of the community schools model at the school site.

- School‑Based and LEA‑Based Advisory Councils. Designing shared decision‑making models at the school site and at the LEA that engage students, staff, families, and community members.

- Integrating and Aligning With Other Relevant Programs. Ensuring schools provide services that align with and can help coordinate and extend state, school, and district initiatives

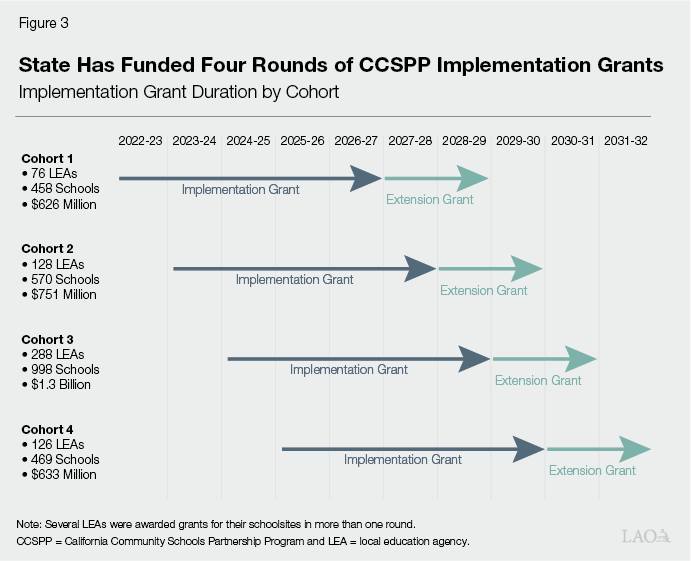

Roughly 2,500 Schools Have Received Funding Across Four Cohorts. To date, the state has awarded implementation grants to about 2,500 schools across roughly 560 school districts, COEs, and charter schools. LEAs were eligible to apply for schools that have either (1) a student body where 50 percent or more of their enrolled students are English learners, low income, or foster youth (EL/LI), or (2) higher than the state average rate of any of the following: dropouts, suspensions and expulsions, child homelessness, foster youth, or justice‑involved youth. Statute gives priority to schools with an EL/LI percentage of more than 80 percent. As Figure 3 shows, the funding was awarded across four cohorts of grantees, from 2022‑23 through 2025‑26. Grantees receive funding annually for a five‑year period. Implementation grant amounts range from $75,000 to $500,000 annually based on school size. Grantees can use funding for a variety of purposes, including for coordination of services (such as hiring a community schools coordinator), providing direct services to students and families, and providing training and support to staff on how to align services with the community schools framework. At the end of the five‑year implementation period, schools could apply to receive extension grants of up to $100,000 for an additional two years. Cohort 1 will be in the final year of the implementation grant period in 2026‑27, and can apply for extension grants for 2027‑28 and 2028‑29. CCSPP is set to sunset at the end of 2031‑32 when Cohort 4 will be at the end of the two‑year extension grant period.

Grantees Have Several Reporting Requirements. As part of the competitive grant process, applicants are required to submit a variety of information, including an implementation plan, a proposed budget for how funds will be used, and various supplemental information demonstrating alignment with the community schools model (such as evidence of having conducted a community asset mapping and needs assessment, a shared decision‑making council, and having agreements with external service providers). Additionally, applicants must submit detailed data regarding student outcomes (such as school attendance rates, test scores, and suspension rates), disaggregated by student subgroup. As a condition of receiving CCSPP funding, grantees are required to publicly present information on their community school plans at school site and local governing board meetings, as well as post information on their websites. The state requires annual updates as described below.

- Annual Expenditure Reports. School sites are required to develop plans for how they will spend community schools funding. This information is aggregated at the LEA level, and the LEA must also document how it used any community schools funding for administrative costs.

- Implementation Plan Updates. As part of the initial application, each school must have a plan for how they will implement the community schools model in alignment with all of the key aspects of the state’s community schools framework. They must include school goals, activities to achieve these goals, and how progress on goals will be measured. The plans also must specify how a community school coordinator will work on executing the community schools model. Each year, the implementation plan is updated based on any changes in goals or services provided.

- Annual Progress Reports. Grantees are required to submit student outcome data on an annual basis for evaluating progress made toward improving student outcomes and other goals set in the original implementation plan. These reports provide an opportunity for the school to assess the effectiveness of the services and supports that are being implemented.

- Sustainability Plans. Beginning in year two of the implementation grant cycle, grantees are required to submit plans annually on how they will sustain the community schools model. This includes how practices will be sustained (such as partnerships and shared leadership and decision‑making structures), how student supports will be sustained, and potential funding sources that could be leveraged when grant funding expires.

At the end of the implementation grant period, grantees are required to provide CDE with a comprehensive report showing expenditure data and progress on meeting specified goals.

State Requires Annual Formative Evaluations of CCSPP. Statute requires CDE to submit annual formative evaluations of CCSPP beginning December 31, 2023, and to submit a final comprehensive report by December 31, 2031. To date, CDE has submitted three reports to the Legislature. These reports provided summaries of CCSPP implementation, including trends in student outcomes and system‑level implementation patterns based on data submitted in annual progress reports and expenditure plans.

Governor’s Proposal

Provides $1 Billion Ongoing Funding for Community Schools. The Governor’s budget provides $1 billion ongoing Proposition 98 General Fund for a new program to support the community schools model. To be eligible to receive funding, schools must (1) enroll more than ten students, (2) have a student body where 65 percent or more of their enrolled students are EL/LI, and (3) must not be a nonclassroom‑based charter school. In addition, current CCSPP grantees that do not meet these criteria would be eligible. Annual grant amounts vary depending on school size and range from $75,000 to $400,000 (Figure 4). The administration estimates that, in addition to schools that have already received one‑time community schools funding, about 3,700 new schools would be eligible for funding. Initially, ongoing funding for current community school grantees would be reduced by the amount of one‑time funding they are currently receiving. Beginning in 2027‑28, the $1 billion ongoing allocation would receive an annual cost‑of‑living adjustment (COLA).

Figure 4

Proposed Grant Amounts

Vary by School Size

|

Enrollment |

Annual Grant |

|

10‑24 |

$75,000 |

|

25‑150 |

115,000 |

|

151‑400 |

190,000 |

|

401‑1,000 |

230,000 |

|

1,001‑2,000 |

305,000 |

|

2,001 or more |

400,000 |

Schools Must Opt Into Funding. To receive funding in 2026‑27, LEAs with eligible schools are required to notify CDE by November 1, 2026 that they intend to receive funding. As with the one‑time grants, LEAs would be allowed to keep the lesser of $500,000 or 10 percent of the total allocation for their eligible community schools to support coordination activities across school sites. For LEAs with eligible school sites that do not opt in by November 1, 2026, trailer legislation specifies that LEAs will have the opportunity to submit a request to be considered for funding during regular intervals. CDE, in collaboration with the S‑TAC and R‑TACs, would determine the deadlines and timing of the intervals for subsequent requests for funding.

Provides $10 Million Annually for Statewide System of Technical Assistance. The Governor’s proposal would set aside $10 million of the $1 billion for technical assistance centers, including $2 million for the S‑TAC. Trailer legislation provides CDE discretion to determine contract terms, including duration, for each technical assistance center, subject to approval by the State Board of Education. The administration has indicated their intent is that any current S‑TAC or R‑TAC that applies and receives funding would receive this funding in addition to their contracted amounts from one‑time community schools funding.

Requirements for New Grantees Begin in 2029‑30. LEAs receiving funding would be required to annually report and publicly present their community school plans. For new community schools grantees, the administration indicates annual reporting requirements would begin in 2029‑30, when they will be required to submit an implementation plan by December 31, 2029. Current implementation grantees would satisfy their reporting requirement through their annual progress reports under the existing one‑time program. In addition, current and future grant recipients would be required to submit an annual self‑certification beginning in 2029‑30, indicating they are continuing to implement the community schools model in alignment with the state’s community schools framework. The self‑certification is to be developed by the S‑TAC.

Establishes an Accreditation Process Beginning in 2033‑34. Beginning in 2033‑34, schools receiving community schools funding must successfully complete an accreditation process every seven years. The accreditation process would be managed by the technical assistance centers and CDE.

Frees Up Current Funding for Extension Grants. Trailer legislation proposes to free up the $485 million allocated in prior budgets that is set aside for the two‑year extension grants. Current community schools grantees would no longer be required to submit requests for extensions. Instead, they would begin receiving ongoing funding at the new proposed rates after their implementation period is over. Trailer legislation specifies that this freed up funding could be used to provide grants to new community schools. The administration indicates it plans to modify this part of the proposal in the May Revision and may allow funds to be used for a broader set of activities related to community schools.

Assessment

Effects of Community Schools Model

Research Finds Benefits to Community Schools Model. Several formal evaluations of community schools nationally tend to find positive results for student and school outcomes, such as higher attendance and graduation rates, narrower academic achievement gaps as measured by standardized tests, and decreases in instances of disciplinary incidents. Consistent with the previous studies, the Learning Policy Institute recently released a report assessing student outcomes of Cohort 1 of community schools grantees. The report found that schools in this initial cohort showed gains in student outcomes, particularly in reduced chronic absenteeism rates and suspension rates, compared with similar schools that did not receive funding. For example, the evaluation found that Cohort 1 grantees declines in chronic absenteeism rates that were 30 percent (about 1.5 percentage points) greater than the declines for similar schools that did not receive community schools funding. Additionally, suspension rates for Cohort 1 grantees declined by 15 percent more (0.52 percentage points) than similar schools. The improvement in student outcomes was reported across student subgroups, however, the improvements were shown to be most significant for Black students, English learners, and socioeconomically disadvantaged students.

Unclear if Future Cohorts Would Have Similarly Strong Gains. The preliminary results suggest implementation of the model has had positive outcomes for students. However, it is not clear if the state should expect to see similarly strong gains for subsequent cohorts. Cohort 1 grant recipients may have been more likely to have experience with the community schools model than those in subsequent cohorts, and therefore may have been better positioned to successfully implement the model. For example, they may have been using the funds to expand programming in an existing community school or part of an LEA that was expanding the community schools model to new school sites. Eligible LEAs that had less experience may have opted to instead to apply for planning grants, or to apply in subsequent rounds of funding. The state will have more information available regarding the effects of implementing the model as data become available for future cohorts.

Many Schools Report Key Changes in Practices. Information gathered by CDE from annual progress reports demonstrate that many schools in the first cohort of grantees made key changes through implementing the community schools model. One key change cited by many schools was increased collaborative leadership and practices. For example, many schools reported increased engagement from students, families, and school staff as a result of seeking more feedback from families and community partners. Schools reported they made changes in their practices to respond to this feedback. Many schools also have reported establishing shared leadership structures so that decisions can be made with input from administrators, staff, students, parents, and community partners. These changes helped inform the community schools implementation plan. Another key change was better integration of supports and services through various funding streams and programs. Having more frequent communication among school staff and with community partners can help schools to more effectively use their existing resources. For example, improved coordination between instruction during the school day and after school programs can help schools more effectively support student academic success and well‑being. In addition, grantees have leveraged multiple funding sources (such as expanded learning funds, federal funding, and Medi‑Cal reimbursements) to provide more wraparound services, such as behavioral health and counseling, academic supports, and nutritional services. Additional services are sometimes supported by district general purpose funds or through community partnerships. Some schools also reported making changes in their curriculum so that instruction better reflects the culture, experiences, and interests of students.

Model Can Be Challenging to Initiate and Sustain. Although adopting a community schools model can lead to improved outcomes, particularly for disadvantaged students with the greatest needs, successful adoption requires fundamental changes that can be complicated for LEAs to implement. School staff often do not have the skills or experience to implement key aspects of the community schools model, such as improving community engagement and building partnerships with other local organizations. For example, the 2025 annual formative evaluation cites the lack of staff training as a key challenge to implementing the community schools model. It also cited several other challenges, including organizational silos within the LEA and resistance among staff to changing long‑held processes and procedures. Another key challenge reported was limited ongoing resources. Community schools typically require a variety of longer‑term funding streams to expand the services provided to students and families. LEAs can generate additional funding by building the capacity to be reimbursed for certain health and behavioral health services (funded by Medi‑Cal or private insurance), or by seeking philanthropic funds. These funds, however, typically are not sufficient to sustain all of the LEA’s community schools activities. LEAs also may need to redirect existing funding, such as Local Control Funding Formula (LCFF) or expanded learning funds, for activities that can be integrated with community schools grants.

State Has Robust System of Technical Assistance. Given that implementing the community schools model can be challenging, the state set aside a substantial portion of funding for technical assistance. The state has a comprehensive approach to monitoring progress and support schools statewide. At the state‑level, the S‑TAC and CDE develop frameworks and implementation rubrics to support implementation and capacity building. Additionally, the S‑TAC and CDE help construct data systems to help LEAs with the collection and analysis of data for monitoring progress and continuous improvement. The R‑TACs have provided a wide range of technical assistance to schools, including assisting in conducting asset mapping and community needs assessments and offering communities of practice, where groups of schools implementing the model can share best practices. R‑TACs also support LEAs in building capacity in a variety of areas that support implementation of the community schools model, such as making governance changes, developing external partnerships, collaborating with other public agencies, and identifying ongoing funding streams to sustain the model.

Establishing a New Ongoing Categorial Program

Disadvantages to Creating a New Ongoing Categorical Program. In 2013, the state created LCFF and eliminated dozens of programs that provided funding for restricted or targeted purposes, also known as categorical programs. These changes were made with the goal of streamlining state funding and providing funding more equitably across LEAs. In addition, these changes were intended to give LEAs more discretion over spending decisions, recognizing that local decision makers are better positioned to understand the specific needs of their students. Although categorical programs are typically created to support activities that the state determines to be a high priority, they have some key drawbacks in comparison to LCFF:

- Less Flexibility. Categorical programs typically come with new spending requirements that limit an LEA’s flexibility in deciding how to best use its funding. In the case of this proposal, school districts must implement the community schools framework and maintain accreditation or risk losing funding. During times when school districts have constrained budgets and need to reduce programs, this may result in LEAs prioritizing community schools spending and making reductions in other areas (such as math tutoring), even if they believe these other activities would be more beneficial for students.

- Presumes Best Practices Can Be Scaled. Many categorical programs were created to encourage statewide adoption of best practices found to be effective. However, implementing best practices does not necessarily result in the same type of strong improvements when scaled at a state level. In some cases, LEAs do not have the expertise to effectively implement these best practices, and the state does not have the capacity or expertise to support schools to ensure effective implementation. In addition, state‑required activities may be seen with skepticism and may not have sufficient local buy‑in for the practices to be implemented effectively. In the case of the Governor’s proposal, many of the 3,700 newly eligible schools may not have the expertise or local buy‑in to effectively implement the community schools model and, as we discuss later, the state may not have the capacity to provide support to such a large number of schools. Despite these challenges, however, many schools are likely to opt into the program to maximize the amount of funding they receive from the state, particularly since schools have no requirements as a condition of receiving the funding until 2029‑30.

- More Administratively Burdensome. Categorical programs typically have greater administrative burden because school staff must comply with additional reporting requirements and become familiar with the program rules. In the case of this proposal, LEAs would be required to comply with annual reporting requirements and meet the necessary requirements for accreditation.

- Can Result in Similar LEAs Being Treated Differently. Prior to LCFF, the allocation formulas for numerous programs were based on historical factors that no longer had relevance. Over time, this led to variation in funding across districts with no underlying rationale. The Governor’s proposal uses clear objective criteria to determine eligibility (a school’s EL/LI percentage). However, the Governor’s proposal allows recipients of one‑time community schools funding to be eligible for ongoing funding, even if they do not meet the other eligibility criteria. This element of the proposal would result in similar schools being treated differently by the program.

In our view, unless the state has a compelling reason to the contrary, the state should allocate ongoing funding through LCFF so that LEAs have greater flexibility to allocate their funding to address their student needs.

Additional Ongoing Spending Can Create Fiscal Pressure for State. As we discuss in the “Overview” section of this report, we recommend the Legislature be cautious about new spending commitments in order to provide a cushion in case the state faces a decline in revenues. By creating a new $1 billion ongoing program that would increase annually by the COLA, the Governor’s proposal would somewhat increase the likelihood that the state may not be able to fund its K‑12 commitments if the state were to experience a revenue downturn.

Community Schools Funding Was Expected to Be Temporary. The state provided CCSPP grants with the expectation that the grants would serve as start‑up funding to implement the community schools model. Grantees were expected to identify ongoing funding streams—either existing school funds, such as LCFF, or new revenue streams—that could be used to sustain the community schools model after one‑time grant funds expire. Additionally, each cohort receives a lower grant amount in their fifth year of implementation to encourage grantees to begin relying on other funding sources to sustain their programs. The phasing out of targeted funding also provides LEAs with an opportunity to build strong local buy‑in to help ensure their community will support the model over the long run. (In some cases, LEAs may decide the model was not a good fit for their specific schools.) Building this local buy‑in is important for the long‑term success of the community schools model and can help support other key efforts, such as identifying other sources of funding that can sustain the model. Providing ongoing funding may dampen efforts for LEAs to build this strong local buy‑in. In addition, some schools that would receive funding under the Governor’s proposal may have been able to sustain their programs without new ongoing funding.

Design and Scope of Proposed New Program

New Grantees Would Have Few Requirements Until 2029‑30. Under the state’s one‑time community schools grants, applicants were required to submit implementation plans and provide supporting materials demonstrating a commitment to the community schools framework. Those that received grants are required to comply with a variety of annual reporting requirements. In contrast, under the Governor’s proposal for ongoing funding, new recipients would have no substantive requirements until 2029‑30—three years after initially receiving funding. (The only requirement would be to notify CDE by November 1, 2026 that they intend to receive funding.) Based on our conversations with individuals involved with implementing the community schools model, the requirements for one‑time grantees helped LEAs begin to identify their community needs, identify key challenges, and access support from COEs and R‑TACs when needed. Without any specific planning expectations for the first three years of funding, new grantees may not be as successful in establishing their programs as prior recipients.

Unclear How Frequently Schools Would Be Able to Opt Into Program in Future. Under the Governor’s proposal, LEAs must decide by November 1, 2026 if they want to participate in the program for 2026‑27. Those that choose not to participate could opt into the program in the future, at “regular intervals” determined by CDE and the technical assistance centers. This lack of detail creates significant uncertainty for LEAs, particularly for those that may want to stagger implementation of the community schools model at their eligible school sites. The lack of clarity could encourage LEAs to opt into the program right away, even if they are not prepared to begin implementing the model. Moreover, if the state does not allow LEAs to opt in for many years, some eligible schools may be locked out of the program for a long period of time.

Significant Influx of New Grantees Raises Concerns With Capacity for Support. Through CCSPP, the state’s system of technical assistance has provided support to about 2,500 schools over four cohorts. The Governor’s proposal would essentially create a fifth cohort of grantees that could be as large as 3,700 schools in 2026‑27. This would be more than triple the number of grantees than in any of the previous cohorts. Many of these grantees also would be less familiar with the community models model and may not have begun the planning process. With such a large increase in new grantees, we think it is unlikely the state’s system of technical assistance would have the capacity to fully support the new grantees.

Proposed Accreditation Process Lacks Detail. Under the Governor’s proposal, the state’s main tool for ensuring community school funds are spent effectively is through an accreditation process. This approach could have some benefits. An accreditation process could be designed to focus on implementation practices, rather than more bureaucratic compliance reporting. Making funding contingent on accreditation also could create a strong incentive for schools to effectively implement the community schools model. The administration’s proposed trailer legislation, however, has little detail regarding the accreditation process or how the process will be determined. Broad discretion is given to the S‑TAC, R‑TACs, and CDE to develop the accreditation process, with no time line for when the process must be adopted and shared with LEAs. The proposal also does not specify how costs for accreditation would be covered. Without such detail, it is not possible to determine whether this would be an effective approach for ensuring accountability or whether the funding available is sufficient to cover the associated costs.

$1 Billion Is More Than Necessary Initially, but May Not Be Sufficient Over Long Term. The administration estimates the cost of providing grants to new community schools would be $800 million initially, assuming every eligible school receives funding in the budget year. During the first few years of implementation, the cost would be less than $1 billion because many of the current grantees still have one‑time implementation funds available from prior‑year allocations. Trailer legislation allows any unallocated funding to be rolled over across fiscal years, which will likely result in hundreds of millions of dollars of surplus funding being available for the program in the initial years. In addition, the $485 million freed up from the set‑aside for extension grants will result in additional funding that could be used for a one‑time purpose. However, as current community schools grantees exhaust their available one‑time funds, ongoing costs would begin to increase. By 2030‑31, when all current grantees would have exhausted their one‑time funding, assuming community school grant rates receive COLA, we estimate ongoing costs for funding all eligible schools would be a few hundred million dollars higher than the funding provided under the proposal.

Recommendations

Recommend Continuing With One‑Time Funding Approach. Although the community schools model has been shown to have a variety of benefits for students, we have concerns about funding the model at such a large scale. The model can be challenging to implement and requires strong local support to be successful. In addition, we have broader concerns about establishing a new ongoing categorical program restricted for specific purposes. For these reasons, we recommend the Legislature continue funding community schools implementation with one‑time grants. This would allow additional schools to receive start‑up funding from the state to implement the community schools model, while leaving the decisions about whether to provide ongoing financial support for sustaining the model to LEAs if they find there are adequate benefits for their students. The Legislature could provide the $1 billion in 2026‑27 as one‑time funding for additional rounds of community schools implementation grants under the current CCSPP application and reporting requirements. Based on the awards granted to date through CCSPP, we estimate the state could support roughly 700 additional schools with this amount. The state likely would see demand from schools for additional one‑time funding. According to CDE, 238 LEAs applied for funding from Cohort 4 and passed the initial application screening, but were not awarded grants due to limited funds. Continuing with the state’s one‑time funding approach would give the state more control over the number of new grantees, which would help ensure sufficient capacity exists to support schools implementing the model. This approach would also avoid some of the pitfalls of creating a new ongoing program.

Consider Funding Technical Assistance Over Longer Period. Under the state’s one‑time funding approach, technical assistance funding is available over the same period that schools receive grants for implementation. Given the importance of technical assistance in implementing the community schools model, the Legislature may want to consider funding technical assistance over a longer period of time, so that LEAs have access to support in future years. For example, the state could set aside additional funding to support schools beyond the initial implementation period. Moving forward, the state could consider whether it may be reasonable to provide ongoing funding for this purpose and integrate these activities into the broader state system of support that funds regional support through COEs and establishes leads for certain issues, such as addressing achievement gaps and improving literacy instruction. This would provide a baseline level of support for community schools implementation in the longer term, even if the state does not provide funding for community schools annually.

If Providing Ongoing Funding, Recommend Several Modifications to Proposal. If the Legislature is interested in providing ongoing funding for community schools, we recommend the Legislature make several modifications to the Governor’s proposal.

- Prior to Accreditation Process, Align Requirements for New Grantees With Current CCSPP Guidelines. While the state is developing the accreditation process for community schools, we recommend setting annual planning and reporting requirements for LEAs, consistent with the current requirements for CCSPP Cohort 4. This would encourage schools receiving funding to begin planning and accessing technical support earlier in the process. After implementation of the accreditation process, some CCSPP requirements—such as expenditure reports and sustainability plans—may become duplicative or unnecessary.

- Phase in Eligibility Over Time. To ensure the state has capacity to support new community schools, we recommend initially targeting a narrower scope of schools and then expanding eligibility over multiple years. For example, the state could begin by only allowing schools with an EL/LI percentage that is 85 percent or greater to be eligible in 2026‑27, then expand to all schools with 65 percent EL/LI or higher over multiple years. This would allow for smaller cohorts and more time for the state to absorb the influx of new grantees.

- Set Clear Guidelines for When Eligible Schools Can Opt in Moving Forward. For schools that choose not to initially opt into the program, we recommend specifying the interval in which they could begin participating in the program (currently not defined in the Governor’s proposal). We think allowing schools to opt in on an annual basis is reasonable, as it would ensure that schools do not opt in just to avoid potentially being locked out of the program for a long period of time. In addition, clear expectations would help LEAs develop multiyear plans to expand the community schools model in their eligible schools.

- Begin Accreditation Process Earlier for Current Grantees. To make implementation of accreditation more manageable for the state, we recommend staggering the accreditation process based on when schools initially received community schools funding. For example, the Legislature could begin the accreditation process for the first cohort of grantees in 2029‑30—seven years after receiving their initial CCSPP grants. This would provide all schools with the same amount of time to establish their programs before having to meet accreditation requirements. Starting the process earlier with more experienced schools also would give the state time to apply the accreditation standards to a smaller cohort of schools and determine if changes are needed.

- Set More Specific Time Lines Around Accreditation Process. In addition to setting an earlier date for when accreditation would begin, we recommend establishing time lines for key milestones associated with the development of the accreditation process. We recommend the Legislature require CDE and the S‑TAC to submit a status update on the accreditation process that includes draft guidelines and estimated costs. We also recommend the Legislature require adoption of the accreditation process several months before schools begin going through accreditation. For example, the Legislature could require a status update by January 2028 and adoption of the process by January 2029, with the goal of beginning accreditation activities in 2029‑30. Receiving a status update would give the Legislature an opportunity to determine whether the proposed guidelines provide sufficient accountability for schools and whether existing funding is sufficient to support accreditation costs. This also would allow schools to develop a better understanding of what they must do to meet accreditation standards.

- Assess Funding Level for Technical Assistance Centers. The Legislature may want to assess whether the proposed funding level for technical assistance is sufficient given the increased number of schools that will be supported on an ongoing basis. The specific level of funding would depend on several factors, including the number of new schools expected to receive funding annually and the amount of support R‑TACs and the S‑TAC are expected to provide to new grantees.

- Require Unspent Funding to Revert Back to the State. We recommend requiring unallocated funding from community schools grants to revert back to the state at the end of each fiscal year. We also recommend reverting the $485 million currently set aside for extension grants. This would provide the Legislature an opportunity to determine—through the annual budget process—how these excess funds can be allocated to best achieve the state’s educational goals. If the Legislature finds that additional one‑time funding to support community schools is a high priority at that time, it could provide a specific appropriation accordingly.

Expanded Learning Opportunities Program

Background

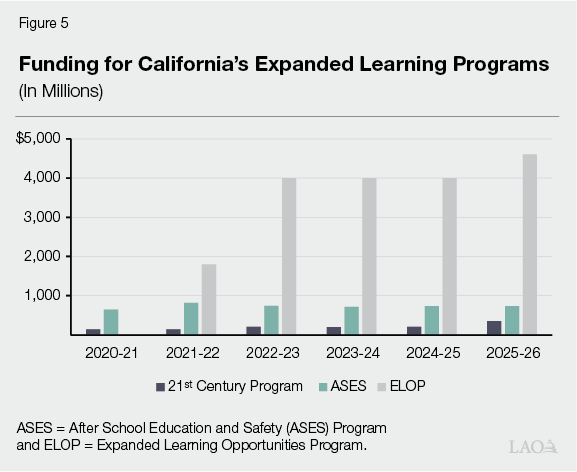

State Has Three Expanded Learning Programs. The state has three expanded learning programs that provide students with academic and enrichment activities outside of normal school hours. Two of these programs, the After School Education and Safety (ASES) program and 21st Century Community Learning Centers (21st Century program), are longstanding. In 2002, voters approved Proposition 49, which requires the state to provide at least $550 million annually to the ASES program. The 21st Century program is primarily federally funded. In 2021‑22, the state created the Expanded Learning Opportunities Program (ELOP) with plans to ramp up funding through 2025‑26. This program now represents the vast majority of funding schools receive for expanded learning (Figure 5).

ELOP Funds Allocated Through a Two‑Tiered Funding Structure. As Figure 6 shows, the ELOP implementing legislation established two funding rates that account for TK‑6 attendance and vary based on the proportion of a school district or charter school’s students who are English learners or from low‑income families (EL/LI). (Throughout this section, we use the term “districts” to refer to school districts and charter schools.) Beginning in 2025‑26, districts with a student body that is 55 percent or more EL/LI receive a rate per EL/LI student ($2,750) that is set in statute. We refer to these as the Tier 1 rates. For other districts, statute specifies the rate will vary based on the amount of funding remaining after accounting for Tier 1 allotments. (These are known as Tier 2 rates.) From 2022‑23 through 2024‑25, the state appropriation remained at $4 billion annually, while the Tier 1 rate and overall Tier 1 TK‑6 attendance increased. As a result, funding available for Tier 2 rates decreased. In 2025‑26, the state increased funding to $4.6 billion and made several programmatic changes. One goal of the funding increase was to ensure that 2025‑26 Tier 2 rates would be no less than $1,579 per EL/LI student. (The funding increases also covered the costs of lowering the Tier 1 threshold and increasing minimum grant amounts.)

Figure 6

ELOP Funding Tiers and Rates Over Time

|

Tier 1 EL/LI |

Tier 1 Rate Per |

Tier 2 Rate Per |

|

|

2021‑22 |

80% |

$1,170 |

$672 |

|

2022‑23 |

75 |

2,500 |

2,054 |

|

2023‑24 |

75 |

2,750 |

1,803 |

|

2024‑25 |

75 |

2,750 |

1,579 |

|

2025‑26 |

55 |

2,750 |

1,579 |

|

ELOP = Expanded Learning Opportunities Program and EL/LI = English learner or low income. |

|||

ELOP Tiers Have Different Programmatic Requirements. Under ELOP, all programs are required to provide at least nine hours per day of combined in‑person instructional time and expanded learning opportunities during the school year and for 30 days during the summer. Tier 1 districts, however, are subject to higher requirements. Specifically, these programs must offer the program to all TK through grade 6 students in classroom‑based settings and provide access to all students whose parent or guardian requests their placement in a program. By contrast, Tier 2 districts are only required to provide access to EL/LI students who are interested in the program. Tier 2 districts can opt to serve non‑EL/LI students and may choose to cover the additional costs above their apportionment by assessing family fees.

State to Begin Collecting Expanded Learning Participation Data This Year. Historically, the state generally has not collected participation data for ELOP. Chapter 1003 of 2024 (AB 1113, McCarthy) requires districts to collect enrollment data for their expanded learning programs through the state’s longitudinal data system, starting with the 2025‑26 school year. This will provide the state with information on participation by district, as well as the demographics of participating students.

Governor’s Proposal

Sets Minimum Tier 2 Rate of $1,800 per EL/LI Student. The Governor proposes to set a minimum Tier 2 rate of $1,800 per EL/LI student, while the Tier 1 rate would remain at $2,750 per EL/LI student. The budget includes an associated ongoing $62.4 million Proposition 98 General Fund increase to fund the higher Tier 2 rates. If additional funding is available within the ELOP appropriation, the funding would be allocated to increase Tier 2 rates above $1,800.

Assessment

Proposed $62.4 Million Is a Reasonable Estimate of Cost to Implement the Proposal. Based on 2024‑25 attendance—the data used to calculate 2025‑26 allocations—the proposed $62.4 million in additional funding would allow for increasing the Tier 2 rates. By the spring, the state will have preliminary 2025‑26 attendance data that it can use to update this estimate.

Providing Greater Certainty for Tier 2 Rate Would Be Beneficial for Districts. The current Tier 2 ELOP rate is effectively determined by whatever ELOP funding is left over after Tier 1 districts have been funded. This has resulted in significant variability of rates. Between 2022‑23 and 2024‑25, the Tier 2 rate decreased 23 percent (from $2,054 to $1,579). This variability makes it difficult for districts to make long‑term decisions about staffing levels and programming. By setting a minimum rate amount, the Governor’s proposal would provide more predictable funding that would make planning easier for Tier 2 districts.

Proposed Rate Increase Not Tied to Program Costs. The proposed Tier 2 rate of $1,800 would be more than $200 higher than the rate provided in 2024‑25 and 2025‑26. Given the state funded at the lower rate the past two years, we see no clear rationale for providing a rate increase. The state has added no new program requirements in 2026‑27 that would require higher levels of funding. Moreover, as we discuss in a previous report, existing ELOP rates are likely providing districts with more funding per participating student than required to meet program requirements. The state will be in a better position to assess the level of funding provided for ELOP by next year, when expanded learning participation data for 2025‑26 becomes publicly available.

No Clear Rationale for Allowing Rate to Exceed Proposed Minimum. In our view, the administration has not presented a compelling case for allowing the Tier 2 rate to exceed the minimum amount proposed. First, this approach would create funding uncertainty for the districts—a problem that the administration is trying to address with this proposal. Notably, the Department of Finance projects the state will experience a 2.8 percent decline in public school enrollment between 2026‑27 and 2029‑30. This decrease in enrollment likely will free up funding within the ELOP appropriation over the next several years to increase the Tier 2 rate. These rate increases would solely be based on available program funds, and as such would create instability for districts. Second, as discussed above, these increases also would not be tied to the costs required to operate expanded learning programs.

Recommendation

Establish Fixed Tier 2 Rate. To provide greater predictability for districts, we recommend setting a specific rate for Tier 2 districts in statute. This certainty would help districts make longer term program decisions. We think the current Tier 2 rate of $1,579 is likely sufficient to meet current ELOP program requirements, but the Legislature could provide a higher rate if it would like to fund additional programs and services. Rather than automatically allocating excess funding within ELOP to Tier 2 districts, we recommend the excess funds revert back to the state. If the Legislature is interested in increasing Tier 1 or Tier 2 rates in the future, we recommend those increases be based on an analysis of program costs that take into consideration the number of students participating in expanded learning programs and the programmatic requirements set in statute.

Necessary Small Schools

Background

Most School District Funding Is Allocated Through the Local Control Funding Formula (LCFF). The LCFF is the primary source of funding for school districts. The formula provides a base amount for each student in four grade spans (transitional kindergarten through grade 3, and grades 4‑6, 7‑8, and 9‑12), plus additional funding for low‑income students and English learners. For funding purposes, the state credits school districts with the greater of their average daily attendance (ADA) in the current year, prior year, or rolling average from the three prior years. Schools pay for most of their general operating expenses (including employee salaries and benefits, supplies, and student services) using these funds. In 2024‑25, the state spent more than $54 billion on LCFF base funding for school districts—an average of about $11,200 per student.

State Has Alternative Base LCFF Calculation for Necessary Small Schools. The Necessary Small Schools program provides an alternative LCFF base grant for the ADA in small schools (96 or less ADA for an elementary school and 286 or less ADA for a high school) within small school districts (generally districts with less than 2,500 ADA). To be classified as a necessary small school, schools also must demonstrate that (1) students who attend the school would otherwise be required to travel relatively long distances from their home to attend school, or (2) geographic or other conditions (such as annual snowfall) make busing students an unusual hardship. In 2024‑25, the state provided $147 million for this purpose—an average of about $16,800 per student for the roughly 8,700 students attending necessary small schools.

Necessary Small School Funding Is Based on ADA and Staffing Levels. The Necessary Small Schools allocation uses funding bands based on either a school’s ADA or its staffing levels, whichever provides the lesser amount. The number of full‑time teachers is used for elementary schools that serve students in grades K‑8, while the number of full‑time equivalent certificated employees is used for high schools. (See Figure 7 and Figure 8, respectively.) Districts receive funding for their necessary small schools in place of LCFF base grants, but they receive LCFF base grant funding for all other schools in the district. As with the LCFF base grant, each necessary small school is credited with the greater of their ADA in the current year, prior year, or rolling average of their three prior years. Necessary Small School funding levels are also annually adjusted by the statutory cost‑of‑living adjustment (COLA). School districts receive supplemental and concentration grant funding for necessary small schools in the same way as the rest of their ADA.

Figure 7

Funding Bands for Necessary Small

Elementary Schools

2025‑26 Rates

|

Number of |

Average Daily |

Funding |

|

1 |

1 to 24 |

$277,457 |

|

2 |

25 to 48 |

549,072 |

|

3 |

49 to 72 |

820,926 |

|

4 |

73 to 96 |

1,092,539 |

Figure 8

Funding Bands for Necessary Small High Schools

2025‑26 Rates

|

Number of Certificated |

Average Daily |

Funding |

|

1‑3 |

1 to 19 |

Up to $740,514a |

|

4 |

20 to 38 |

907,196 |

|

5 |

39 to 57 |

1,073,880 |

|

6 |

58 to 71 |

1,240,562 |

|

7 |

72 to 86 |

1,407,246 |

|

8 |

87 to 100 |

1,573,928 |

|

9 |

101 to 114 |

1,740,612 |

|

10 |

115 to 129 |

1,907,294 |

|

11 |

130 to 143 |

2,073,978 |

|

12 |

144 to 171 |

2,240,662 |

|

13 |

172 to 210 |

2,682,875 |

|

14 |

211 to 248 |

3,167,262 |

|

15 |

249 to 286 |

3,651,657 |

|

aFunding for schools between 1‑19 ADA depends entirely on their number of certificated staff. Specifically, schools receive $233,818 if they have one certificated employee, $333,366 for two, and $740,514 for three. |

||

|

ADA = average daily attendance. |

||

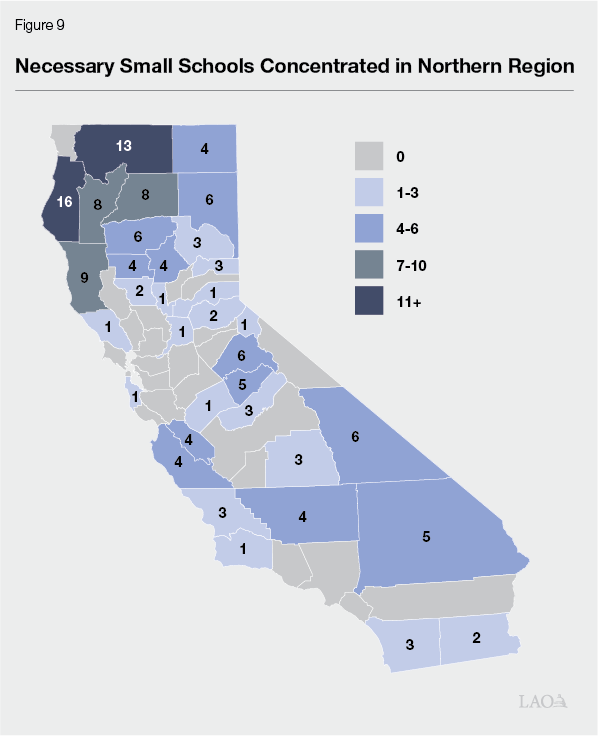

Necessary Small Schools Are Concentrated in Northern Region of the State. In 2024‑25, the state provided additional funding for 144 necessary small schools across 108 districts, including 79 elementary schools and 65 high schools. Of the 108 districts with a necessary small school, 38 districts (35 percent) are comprised entirely of necessary small schools (including 35 districts comprised of a single necessary small school). For districts that receive Necessary Small Schools funding, the combined ADA from their necessary small schools represents roughly 20 percent of their total ADA. As Figure 9 shows, necessary small schools are primarily located in more rural counties, particularly in the northern part of the state.

One‑Fifth of Districts Below 2,500 ADA Have a Necessary Small School. Of the state’s 937 school districts, 551 (59 percent) have less than 2,500 ADA. Roughly one‑fifth of these districts had at least one necessary small school (Figure 10). Furthermore, Figure 10 shows that the vast majority of districts with necessary small schools have less than 500 ADA (77 percent).

Figure 10

One‑Fifth of Small School Districts Have a

Necessary Small School

2024‑25

|

Average Daily |

Districts with Necessary |

Total School |

Percentage of |

|

Less than 500 |

83 |

316 |

26% |

|

501‑1,000 |

12 |

86 |

14 |

|

1,001‑1,500 |

6 |

58 |

10 |

|

1,501‑2,000 |

6 |

48 |

13 |

|

2,001‑2,500 |

— |

43 |

— |

|

Totals |

107a |

551 |

19% |

|

aDoes not include one district that has more than 2,500 units of average daily attendance and receives necessary small schools funding for one of their school sites due to extreme geographic isolation. |

|||

Governor’s Proposal

Provides a 20 Percent Increase to Necessary Small Schools Funding. The Governor’s budget proposes $30.7 million ongoing Proposition 98 General Fund to apply a 20 percent increase to each necessary small school funding band. This is in addition to a 2.41 percent COLA for the rates, equaling roughly $3.6 million. The administration has indicated that this proposal is intended to help necessary small schools maintain instructional programming amidst various fiscal challenges. The administration cites several fiscal challenges, including cost increases that have outpaced inflation, higher per‑student costs, less flexibility to distribute fixed expenses across their student body compared to larger districts, and less flexibility to absorb declines in enrollment compared to larger districts.

Assessment

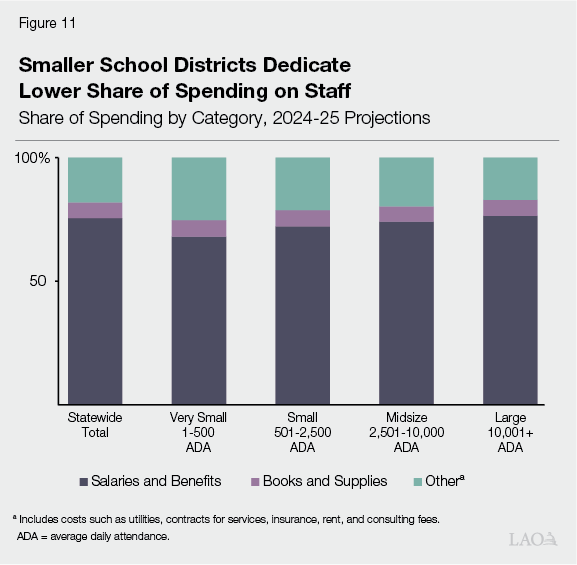

Small School Districts Have Different Spending Patterns. As Figure 11 shows, preliminary 2024‑25 budget data show that very small (less than 500 ADA) and small (between 501 and 2,500 ADA) school districts dedicated a lower share of spending on staffing and a higher proportion on other costs, such as utilities, contracts for services, insurance, rent, and consulting fees. In particular, very small school districts were projecting to spend 25 percent of their budget on these other costs, significantly higher than the statewide average of 18 percent. Due to the lower share of spending on staffing overall, small school districts tend to have more limited educational options for students. A small high school, for example, typically offers a more limited number of course options than a larger comprehensive high school.

Small School Districts May Be More Affected by Recent Cost Pressures. School districts across the state have reported increasing cost pressures in many parts of their budgets, such as special education, employee benefits, and utilities. Additionally, the majority of districts in the state have been experiencing declines in student enrollment, with statewide enrollment declining by roughly 7.3 percent from 2019‑20 through 2024‑25. The decreased funding levels due to declining enrollment place additional fiscal pressure on school districts, often resulting in districts needing to downsize programs or close school sites. Some of these cost pressures may be more acute for small school districts in rural areas. Although small and very small districts have experienced smaller enrollment declines than the state average—4.5 percent for small districts and 3.8 percent for very small districts—accommodating declining enrollment may be more challenging for some of these districts. For example, in our conversations with small school districts, school leaders indicated that closing school sites in response to declining enrollment wasn’t always a viable solution due to the geographical isolation of some schools. Additionally, very small districts may have acute challenges reducing programs as they already dedicate a larger share of their spending on fixed costs compared to larger districts. One indicator of a school district’s fiscal health is the change in its reserve levels over time, with larger increases suggesting stronger fiscal health. While statewide school district reserve levels as a share of expenditures have increased by 8 percentage points since 2019‑20, reserves for very small districts have remained flat over the same period. (Statewide district reserve levels have increased in part due to one‑time funding the state has provided that is to be spent over a multiyear period.) This suggests very small school districts may be experiencing greater fiscal pressures than school districts statewide. Reserves for small districts increased somewhat, but at a lower rate than the state average.

Governor’s Proposal Increases Funding for Only a Portion of Small and Very Small Districts. Although recent cost pressures may be more acute for small and very small school districts, the Governor’s proposal would provide funding to only a subset of these schools (about one‑quarter of school districts under 500 ADA). Districts with necessary small schools have similar cost structures to that of very small districts overall. They have a similar share of their budget that is dedicated to other costs (24 percent) and also have had little growth in their reserve levels since 2019‑20 (growth of 1 percentage point, compared with no growth for very small districts).

No Specific Rationale for Level of Proposed Increase. Although the administration cited a variety of cost pressures as the reason for providing an increase in Necessary Small Schools funding, the proposed 20 percent increase is not tied to any particular assessment of higher cost pressures.

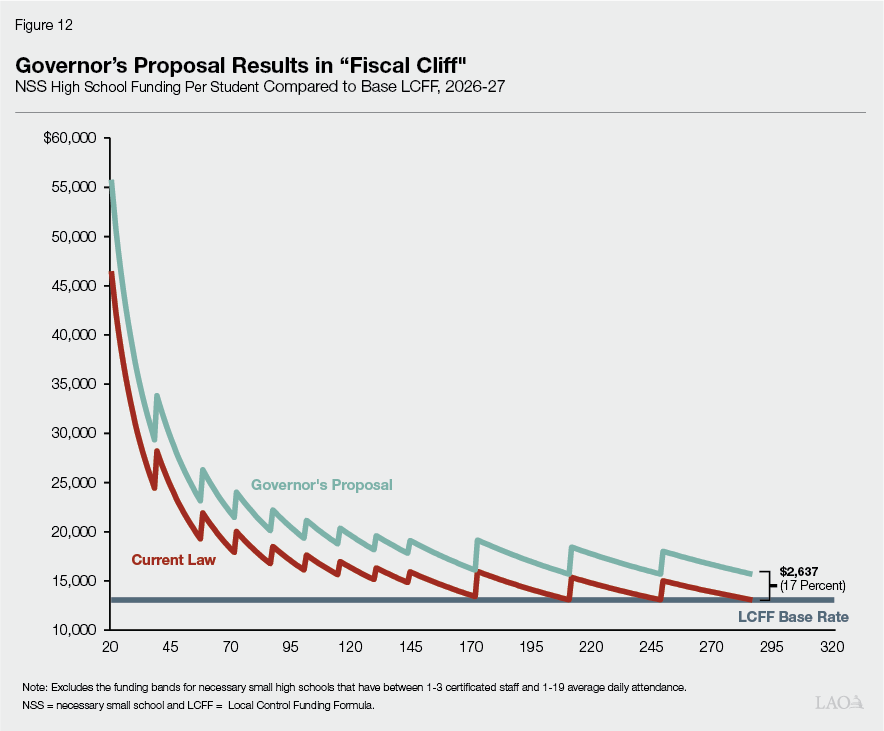

Augmentation Results in “Fiscal Cliff” at End of Funding Bands. The existing funding bands for necessary small schools provide greater per‑pupil funding for the smallest schools, with per‑pupil funding decreasing in each subsequent funding band. This means that per‑pupil funding for schools right above or below the existing thresholds (96 ADA for elementary schools and 286 ADA for high schools) do not result in substantially different rates. However, the Governor’s proposed 20 percent augmentation results in a large difference between schools above or below the threshold for the highest funding bands. Figure 12 shows the fiscal effects for necessary small high schools. Under the Governor’s proposal, a necessary small high school with 286 ADA would generate roughly $2,637 more per student than a school with 287 ADA. (Under current law, the difference would be $22 per student.) This would create a significant fluctuation in funding if schools have ADA that is at or near the threshold of the highest funding band.

Issues for Consideration

Proposal Is a Simple Way to Target Some Small Districts Within Existing Funding Structure. The Governor’s proposal has some merit given it would target districts that likely face greater cost pressures from operating very small schools in geographically isolated parts of the state. If the Legislature is interested in increasing funding for small school districts, increasing Necessary Small School funding is a simple way to do so under the current LCFF structure. Given the proposed 20 percent increase is not aligned with any particular assessment of costs, the Legislature could consider providing a different level of funding based on its priorities. The Legislature may also wish to weigh this proposal against its other education priorities, such as providing funding increases that more broadly benefit schools statewide or proposals that help build budget resiliency.

Legislature Could Consider Alternative Approaches That Target Small School Districts. As mentioned above, one‑fifth of the smallest school districts in the state have a necessary small school and would receive additional funding under this proposal. If the Legislature is interested in providing funding in a way that benefits small school districts more broadly, it could consider exploring other options. For example, the Legislature could explore options for modifying LCFF or creating an LCFF add‑on that accounts for the density of districts’ student populations. These options, however, could be more complex to design and would require additional analysis to ensure they are aligned with a district’s cost structure. In addition, these options likely would result in significantly higher costs compared to the Governor’s proposal.

If Adopting, Legislature May Want to Consider Addressing “Fiscal Cliff” Issue. If the Legislature is interested in adopting the Governor’s proposal, we recommend it modify the proposal to avoid large differences in funding above and below the ADA thresholds. One option is to add a new funding band or extend the range of the final funding band to increase the ADA threshold. This would allow for a more gradual reduction in per‑pupil funding until, as ADA approaches the new threshold, schools shift to the regular LCFF base rates. By increasing the ADA threshold, however, this approach would have higher state costs than the Governor’s proposal. Alternatively, the Legislature could modify rates in a way that minimizes the fiscal cliff and has similar costs to the Governor’s proposal. Implementing this option would require larger increases to the lower funding bands (for schools with lower ADA) and smaller increases to the highest funding bands, with minimal increases for those closest to the threshold.

Differentiated Assistance

Background

State Uses Various Indicators to Understand Student Outcomes. The state uses multiple indicators and a variety of data sources to assess the student outcomes of local education agencies (LEAs)—school districts, county offices of education (COEs), and charter schools—as well as individual schools. For example, to understand student achievement, the state uses standardized test results in English, math, and—for English learners—progress in developing English proficiency. In addition to tracking outcomes related to standardized tests, the state also uses indicators in other areas, such as student engagement and school climate. For example, to understand student engagement, the state uses high school graduation and chronic absenteeism rates.

State Displays School Performance Through California School Dashboard. The state publicly displays achievement on these indicators on a website known as the California School Dashboard. Performance is shown for the state, each LEA, and each school. In addition, performance for the state, each LEA, and each school is disaggregated by up to 14 student subgroups (Figure 13). The dashboard was first made available in fall 2017 and is updated annually. (The state suspended annual updates in 2020 and 2021 given some of this data was not collected during the COVID‑19 pandemic.)

Figure 13

Student Subgroups for Which

Outcome Data Is Reported

|

Racial Subgroups |

|

American Indian or Alaska Native |

|

Asian |

|

Black |

|

Filipino |

|

Hispanic or Latino |

|

Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander |

|

Two or more races |

|

White |

|

Other Subgroups |

|

English learners |

|

Foster youth |

|

Homeless youth |

|

Long‑term English learners |

|

Socioeconomically disadvantaged |

|

Students with disabilities |

Dashboard Uses Five Performance Levels. For each performance indicator shown by LEA, school, or subgroup, the state assigns one of five performance levels. Performance levels are based on a combination of overall status and change in the measure over the past year.

Dashboard Used to Identify LEAs in Need of “Differentiated Assistance.” LEAs are identified for differentiated assistance annually based on the performance of their student subgroups—also known as the performance criteria. Certain requirements of the performance criteria are set in statute, with the State Board of Education (SBE) responsible for deciding the specific details for implementation. Under current law, a school district or COE enters differentiated assistance based on low performance of a student subgroup in two or more areas. SBE determines the performance level threshold that determines eligibility for differentiated assistance. This is similar for charter schools, except they must meet the performance criteria for two consecutive years to enter differentiated assistance. In 2025, 553 LEAs were eligible for differentiated assistance. When a school district or charter school is identified, it receives assistance from its COE for two years. (Identified COEs receive assistance from a state agency or another COE.) As part of differentiated assistance, the COE is to support the district or charter school to build their capacity to implement actions that address student needs. The specific support may vary, but actions can include helping a district identify the primary causes of its performance issues or securing an expert to assist in a specific area.

State Provides Ongoing Funding to Support Differentiated Assistance. The state provides COEs with additional funding to cover the costs associated with their differentiated assistance activities. This funding is provided through a formula that consists of a base amount of $300,000 for each COE, plus additional funding based on the number of districts and charters in the county in need of differentiated assistance. (The amount per district varies based on the district’s size.) The 2025‑26 Budget Act provided COEs $119 million for this purpose.

SBE Required to Make Changes to Performance Criteria. Trailer legislation included in the 2025‑26 budget package requires SBE to update the performance criteria by July 15, 2026. This update will change how LEAs are identified for differentiated assistance.

Governor’s Proposal

Changes Differentiated Assistance Funding Formula. The Governor’s budget provides an additional $13 million ongoing Proposition 98 General Fund to adopt a new formula for differentiated assistance. This would bring total differentiated assistance funding to $132 million. The new formula would increase the base amount for each COE from $300,000 to $500,000. The remainder of funds would be based on the number of students within the county rather than the number of districts and size of districts identified. The Governor’s budget also proposes to expand the intended use of these funds. The funding is intended to fund targeted assistance to those LEAs identified for differentiated assistance, as well as universal support to all LEAs for improving student outcomes.