Kenneth Kapphahn

February 4, 2026

The 2026‑27 Budget

Proposition 98 Guarantee and K-12 Spending Plan

- Introduction

- Minimum Guarantee

- Settle Up

- School Spending Plan

- Appendix: Summary of Assessment and Recommendations

Summary

School Funding Requirement Grows, but Underlying Revenue Estimates Are Risky. The state calculates an annual “minimum guarantee” for school and community college funding based upon the formulas established by Proposition 98 (1988). Compared with the June 2025 enacted budget, the Governor’s budget estimates the guarantee is up $3.9 billion (3.2 percent) in 2024‑25, $6.9 billion (6 percent) in 2025‑26, and $10.9 billion (9.5 percent) in 2026‑27. These estimates depend on revenue projections that do not account for the current elevated stock market risks. A major downturn could reduce revenues by tens of billions of dollars—reducing the guarantee by about 40 cents for each $1 of lower revenue.

Recommend an Alternative to the Governor’s Proposed Funding Delay. The Governor proposes delaying a $5.6 billion payment associated with the higher estimate of the 2025‑26 guarantee. This delay shifts costs to the future when the state must “settle up” and meet this obligation. We recommend an alternative that would set aside funding to cover the full cost of the guarantee while holding some or all of the additional funding in the Proposition 98 Reserve. This alternative would address the Governor’s concern about inadvertently exceeding the guarantee and avoid worsening future budget deficits. It would also require additional solutions for the non‑Proposition 98 side of the budget this year.

Governor’s School Spending Plan Has Some Prudent Features. After accounting for higher guarantee estimates, delayed payment, and other adjustments, nearly $9.7 billion is available for new school spending. The Governor’s budget allocates $3.7 billion for ongoing programs and $5.9 billion for one‑time activities. It uses $4 billion in ongoing funds to pay for the one‑time activities. This approach is prudent because it creates a cushion to protect ongoing programs if the guarantee declines in the future. Separate from the new spending proposals, the Governor’s budget adds $4.1 billion to the Proposition 98 Reserve. Most of this amount is required by constitutional formulas, but a small portion reflects a discretionary deposit.

Recommend Adopting Several of the Larger Proposals. The largest ongoing proposal provides $2.3 billion for a 2.41 percent cost‑of‑living adjustment (COLA). We recommend funding the final statutory COLA rate unless revenue estimates drop significantly by May. The budget also provides $1 billion in ongoing funds for community schools, a proposal we plan to analyze in a forthcoming report. Regarding one‑time proposals, the Governor proposes $2.8 billion for a discretionary block grant, $1.9 billion to eliminate previous payment deferrals, and $757 million to restore the Learning Recovery Emergency Block Grant. These proposals would help sustain local programs and fund previous commitments, and we recommend adopting them.

Legislature’s Core Budget Decisions Revolve Around Risk and Resiliency. As the Legislature reviews the Governor’s budget and makes adjustments, we recommend that it plan for scenarios where the guarantee decreases. In practical terms, this approach means being cautious about new spending commitments, building reserves and other tools to protect existing school programs, and identifying proposals that it would be willing to delay, reduce, or reject if the guarantee were to drop. The Legislature cannot predict the timing or magnitude of the next downturn, but it can use the upcoming hearings to identify actions that would stabilize the budget, shore up programs that benefit students, and preserve its core priorities. (For brevity, this report refers to school districts, charter schools, and county offices of education collectively as “districts.” The appendix contains a summary of our recommendations.)

Introduction

This brief examines the Governor’s school spending plan. The first section analyzes the funding requirement established by Proposition 98 and explains how changes in revenue estimates could affect this requirement. The second section analyzes the Governor’s proposal to delay a payment associated with the higher estimate of this requirement. The third section analyzes the Governor’s plan for allocating the available funds, focusing on its overall structure and major proposals. Whereas the first and second sections address issues affecting schools and community colleges, the third section focuses solely on proposals affecting schools. We analyze community college spending proposals in our forthcoming publication The 2026‑27 Budget: California Community Colleges. On the “EdBudget” section of our website, we post numerous tables with additional budget information. We also plan to release additional briefs in the coming weeks that will examine many of the proposals in detail.

Minimum Guarantee

Proposition 98 established a minimum funding requirement for schools and community colleges known as the minimum guarantee. In this section, we (1) provide background on the guarantee, (2) describe the administration’s estimates of the guarantee, and (3) explain how the guarantee could change in the coming months as the state revises its revenue estimates.

Background

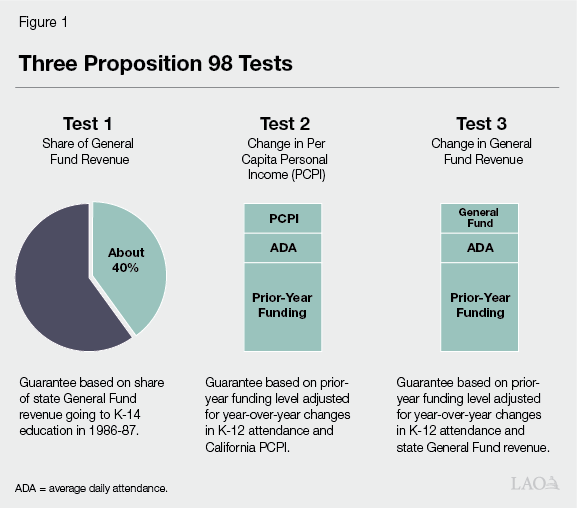

Proposition 98 Guarantee Depends on Various Inputs and Formulas. The California Constitution sets forth three main “tests” (formulas) for calculating the Proposition 98 guarantee. Each test takes into account certain inputs, including General Fund revenue, per capita personal income, and student attendance (Figure 1). Whereas Test 1 links school funding to a minimum share of General Fund revenue, Test 2 and Test 3 build upon the funding provided in the previous year. The Constitution contains rules for comparing the tests, with one becoming operative and determining the guarantee for that year. With a two‑thirds vote of each house of the Legislature, the state can suspend the guarantee and provide less funding than the formulas require in a given year. The state funds the guarantee through a combination of state General Fund and local property tax revenue.

Maintenance Factor Accelerates Growth in the Guarantee. Besides the three main tests, the Constitution requires the state to track an obligation known as maintenance factor. The state creates this obligation when Test 3 is operative or the Legislature suspends the guarantee. The obligation equals the difference between the actual funding provided and the higher Test 1 or Test 2 level. Moving forward, the state adjusts the obligation for changes in student attendance and per capita personal income. The Constitution requires the state to make maintenance factor payments when General Fund revenue grows faster than per capita personal income.

The Guarantee Is a Moving Target. The state estimates the guarantee when it enacts the budget, but this calculation typically changes as the state updates its revenue estimates. The state recalculates the guarantee at the end of each year and again at the end of the following year. This schedule means each budget includes new estimates for the previous, current, and upcoming years. The state finalizes its calculation of the prior‑year guarantee through a statutory process called certification. This process involves publishing the underlying inputs and allowing the public to review and comment on the calculations. The most recently certified year is 2023‑24. The state will begin certifying the 2024‑25 guarantee in May and conclude this process in August.

Proposition 98 Reserve Helps Stabilize Funding. The Constitution establishes a reserve for school and community college funding—the Public School System Stabilization Account (Proposition 98 Reserve). The Constitution requires the state to deposit Proposition 98 funds into this reserve when it receives significant tax revenue from capital gains and the guarantee is growing quickly relative to inflation. It requires withdrawals when the guarantee grows more slowly than inflation. The state can use these withdrawals for any school or community college purpose. The state updates its estimates of any required deposits or withdrawals whenever it recalculates the guarantee. Additionally, a state law caps the local reserves held by medium and large school districts when the Proposition 98 Reserve balance exceeds 3 percent of the funding allocated to schools in the previous year.

Governor’s Budget

Estimates of the Guarantee Revised Up in 2024‑25 and 2025‑26. Compared with the June 2025 budget estimates, the administration estimates the guarantee is up $3.9 billion (3.2 percent) in 2024‑25 and $6.9 billion (6 percent) in 2025‑26 (Figure 2). Test 1 remains operative in both years, with the increase mainly reflecting higher General Fund revenue estimates. The administration also revises its local property tax estimates upward by $319 million in 2024‑25 and $126 million in 2025‑26. These increases reflect recent data showing higher distributions from redevelopment successor agencies and slightly faster growth in assessed property values. When Test 1 is operative, changes in property tax revenue have dollar‑for‑dollar effects on the guarantee.

Figure 2

Guarantee Revised Up in Prior and Current Year

(In Millions)

|

2024‑25 |

2025‑26 |

||||||||

|

June 2025 Estimate |

January 2026 Estimate |

Change |

Percent Change |

June 2025 Estimate |

January 2026 Estimate |

Change |

Percent Change |

||

|

General Fund |

$87,628 |

$91,197 |

$3,568 |

4.1% |

$80,738 |

$87,473 |

$6,735 |

8.3% |

|

|

Local property taxes |

32,317 |

32,636 |

319 |

1.0 |

33,821 |

33,947 |

126 |

0.4 |

|

|

Total Guarantee |

$119,946 |

$123,833 |

$3,887 |

3.2% |

$114,558 |

$121,420 |

$6,861 |

6.0% |

|

|

General Fund tax revenue |

$209,813 |

$213,420 |

$3,607 |

1.7% |

$204,027 |

$222,181 |

$18,154 |

8.9% |

|

State Pays Off Most of the Maintenance Factor Obligation. The administration’s calculation of the 2024‑25 guarantee includes a $7.8 billion maintenance factor payment, an increase of $2.3 billion from the June 2025 estimate. After making this payment, the state’s remaining obligation would be $523 million. For 2025‑26, the Constitution does not require any maintenance factor payments because General Fund revenues are growing relatively slowly year over year.

Downward Adjustment Related to Transitional Kindergarten (TK) Estimates. In 2022‑23, the state began implementing a multiyear plan to make all four‑year old children eligible for TK. The plan requires the state to adjust the guarantee upward for these additional students. The Governor’s budget revises the previous estimate of this expansion downward by 5,900 students (5.8 percent) in 2024‑25 and by 13,600 students (8.9 percent) in 2025‑26. These new estimates reduce the guarantee by $80 million in 2024‑25 and $190 million in 2025‑26. On a cumulative basis, the Governor’s budget estimates that 139,100 additional students are attending TK programs in 2025‑26 (the final year of the plan). The Proposition 98 guarantee, in turn, is $1.9 billion more than it would have been without the plan.

Estimates of the 2026‑27 Guarantee Up Significantly From the Previous Budget Level. The Governor’s budget estimates the guarantee at $125.5 billion in 2026‑27, an increase of $10.9 billion (9.5 percent) relative to the 2025‑26 enacted budget level (Figure 3). Test 1 is operative, and the increase in the General Fund share of the guarantee is about 40 percent of the projected growth in General Fund tax revenue. Increases in local property tax revenue also contribute to the higher guarantee. This property tax increase reflects projected growth in assessed property values (estimated at 5.4 percent) and several smaller adjustments. The Governor’s budget does not make any further adjustments related to TK, but the previous adjustments remain in place.

Figure 3

2026‑27 Guarantee Grows Significantly Relative to

Previous Budget Level

(In Millions)

|

2025‑26 |

2026‑27 |

Change |

Percent |

|

|

General Fund |

$80,738 |

$89,877 |

$9,139 |

11.3% |

|

Local property taxes |

33,821 |

35,604 |

1,783 |

5.3 |

|

Total Guarantee |

$114,558 |

$125,480 |

$10,922 |

9.5% |

|

General Fund tax revenue |

$204,027 |

$228,467 |

$24,440 |

12.0% |

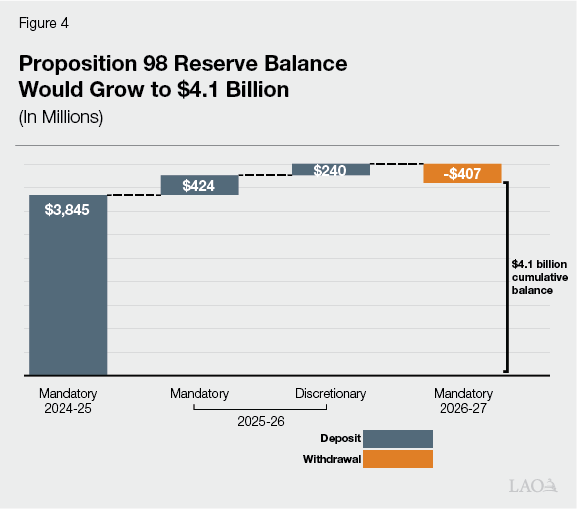

State Makes Notable Deposits Into the Proposition 98 Reserve. The June 2025 budget withdrew the entire balance from the Proposition 98 Reserve. Under the Governor’s budget, the state would make four adjustments that increase the reserve balance to $4.1 billion (Figure 4). The largest adjustment is a $3.8 billion mandatory deposit in 2024‑25, driven by significantly higher capital gains revenue since June. Another notable adjustment is the Governor’s proposal to make a $240 million discretionary deposit in 2025‑26. The reserve balance would exceed the threshold that triggers the local district reserve cap (approximately $3 billion). Although the cap nominally limits a district’s discretionary reserves to 10 percent of its budgeted expenditures, various exemptions and exclusions typically allow higher reserve levels.

Assessment

The Stock Market Poses a Notable Risk to General Fund Revenues. State tax collections have been strong over the past year, but these gains primarily reflect investor enthusiasm for Artificial Intelligence and robust stock market growth. The S&P 500, for example, has risen about 40 percent over the last two years. Several signs, however, suggest that the stock market has become overvalued. For example, the ratio of stock prices to corporate earnings (a measure of how expensive stocks are) is near historically high levels (Figure 5). Investors are borrowing large sums to buy stocks, and households are more invested in the stock market than at any time in at least 70 years. Historically, these signs have preceded stock market downturns. The Governor’s budget acknowledges these risks but assumes that state revenues will continue to grow. If the stock market declines significantly, revenues most likely would drop by tens of billions of dollars.

Guarantee Is Moderately Sensitive to Revenue Changes in 2025‑26 and 2026‑27. General Fund revenue is typically the most significant input affecting the guarantee. For any given year, the relationship between revenues and the guarantee depends on which Proposition 98 test is operative and whether another test could become operative with different inputs. In 2025‑26 and 2026‑27, Test 1 is likely to remain operative even if revenues or other inputs vary significantly from the Governor’s budget estimates. Revenue fluctuations in those years would change the guarantee by approximately 40 cents for each $1 change in General Fund revenue. In 2024‑25, the maintenance factor payment makes the guarantee highly sensitive to revenue changes. The potential fluctuations in 2024‑25, however, are much smaller than in the other years.

Prepare for the Possibility the Guarantee Is Billions of Dollars Lower. Given the significant risks to state revenue estimates, we recommend the Legislature begin preparing for scenarios where the guarantee falls short of the Governor’s budget estimates. For example, our November General Fund revenue estimates for 2026‑27 were about $20 billion lower than the administration’s estimates for that year. A revenue decline of this magnitude would reduce the Proposition 98 guarantee by about $8 billion. In such a scenario, the state could likely maintain existing programs, but would have to reject many of the Governor’s proposals. Although revenue estimates will change in the coming months, we recommend the Legislature place more emphasis on downside risk than upside potential during the upcoming budget hearings. In practical terms, this approach means being cautious about new commitments; building reserves and other buffers to protect existing school programs; and identifying proposals that the Legislature would be willing to delay, reduce, or reject.

Proposition 98 Reserve Is a Key Tool for Protecting Programs. The state has multiple tools that can make school and community college programs more resilient against risk and volatility. The Proposition 98 reserve is particularly powerful because it (1) can be accessed relatively quickly, (2) can support any school or community college activities, and (3) avoids disrupting district cash flow (unlike payment deferrals). Whether through mandatory or discretionary deposits, building this reserve helps protect programs from unexpected revenue drops. The $4.1 billion reserve balance under the Governor’s budget is equivalent to 3.3 percent of the estimated guarantee in 2026‑27, making it a modest but important step toward budget resiliency. Later in this report, we recommend an even larger discretionary deposit as an alternative to the Governor’s settle‑up proposal.

Local Property Tax Estimates Seem Reasonable. The administration’s property tax estimates are only $93 million lower than our November estimates over the 2024‑25 through 2026‑27 period (a difference of less than 0.1 percent). The state will receive updated property tax data in February and April, but significant changes to these estimates seem unlikely.

Settle Up

In this section, we examine the Governor’s proposal to delay a $5.6 billion payment that would be required under the administration’s estimate of the guarantee. The first section reviews how the state typically makes these payments. The second section explains the Governor’s proposal and its connection to the overall state budget. The third section provides our assessment, and the fourth section describes our recommended alternative.

Background

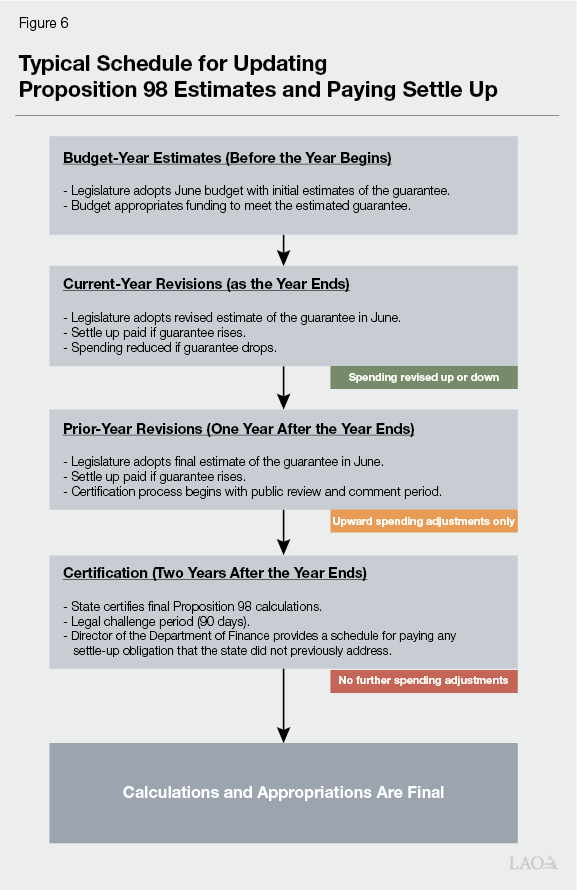

State Required to Settle Up After the Proposition 98 Guarantee Rises. The state makes an initial estimate of the guarantee when it adopts the budget. Over the following two years, revenue estimates and other inputs change, sometimes significantly. When these revisions increase the guarantee, the state must provide additional funding through settle‑up payments. The Legislature can allocate these payments for any school or community college purposes. The Constitution does not specifically address the timing of these payments.

State Usually Pays Settle Up as Soon as It Recognizes a Higher Guarantee… The state does not officially update its estimate of the guarantee until it adopts the following year’s budget. If that budget shows a higher estimate, the state typically includes the corresponding settle‑up payment. A year after the first revision, the state adopts a second revision as part of the next budget. If the second revision exceeds the first, the state makes another settle‑up payment. Figure 6 summarizes the usual schedule for these revisions and settle‑up payments. From an accounting perspective, settle‑up payments are always scored to the year in which the guarantee increased, rather than to the year the state disburses the payment to schools.

…But the State Has Made Several Exceptions. In several instances, the state has recognized an increase in the guarantee without providing additional funding. For example, in July 2009, the state identified a $212 million obligation related to meeting the 2006‑07 guarantee. Trailer legislation scheduled the payment for 2014‑15 (later changed to 2015‑16). In October 2010, the state recognized a $1.8 billion increase to its previous estimate of the 2009‑10 guarantee. It made an initial payment of $300 million but did not schedule any future payments. It paid the remaining amount over the 2015‑16 through 2018‑19 period. Most recently, the June 2025 budget recognized an increase in the 2024‑25 guarantee but set school funding $1.9 billion below the revised estimate. Trailer legislation required the administration to propose a plan to provide this funding as part of the Governor’s January budget.

State Law Has a Contingency for Unpaid Settle‑Up Obligations. A state law adopted in 2018‑19 establishes an alternative payment mechanism if any settle‑up obligation remains after the state certifies the guarantee. (The state begins the certification process after adopting its final estimate of the guarantee.) Specifically, the law converts the remaining obligation into a block grant. The state allocates 89 percent of this grant to schools based on average daily attendance and 11 percent to community colleges based on full‑time‑equivalent enrollment. The law requires the State Controller to disburse this grant automatically according to a schedule determined by the Director of the Department of Finance, potentially over multiple years. This law has never been operative—since 2018‑19, the state has always paid settle up before completing certification.

State Law Prohibits Downward Spending Adjustments After the Year Ends. Settle‑up payments occur after the guarantee increases, but in other years, the guarantee falls short of projections. In these cases, the state usually reduces school spending to match the lower guarantee. In 2019‑20, however, the state adopted a new law prohibiting spending reductions after the fiscal year ends. This law allows the state to reduce spending during its first recalculation of the guarantee, but prevents reductions during the second recalculation at the end of the next fiscal year. If school spending exceeds the guarantee at that time, the higher amount becomes the base for future Proposition 98 calculations. Before this law, the state typically made prior‑year spending reductions through state accounting adjustments, such as counting some of that year’s spending toward the following year’s guarantee. These adjustments sometimes reduced the guarantee going forward, but they did not require districts to return prior payments.

Governor’s Budget

Creates $5.6 Billion Settle‑Up Obligation for 2025‑26. The Governor’s budget estimates that the 2025‑26 guarantee has increased to $121.5 billion but provides only $115.9 billion for schools and community colleges (slightly above the June 2025 enacted budget level). This difference results in a $5.6 billion settle‑up obligation. The administration indicates that the purpose of the proposal is “to mitigate the risk of potentially appropriating more resources to the Guarantee than are ultimately available in the final calculation for 2025‑26.” The budget does not specify when the state would make this payment. If the Legislature adopts the proposal, it would face three choices next year, assuming the obligation is still owed: (1) appropriate additional funding for schools and community colleges in the 2027‑28 budget; (2) take no action, meaning the contingency law would apply and the Director of the Department of Finance would determine the payment schedule; or (3) adopt an alternative plan before certification concludes in August 2027.

Uses the Savings to Help Balance This Year’s Budget. For the state budget, the settle‑up proposal is similar to other forms of borrowing and spending delays—it provides temporary savings in the current year but increases costs in the future. The Governor’s budget allocates these savings for the non‑Proposition 98 side of the budget. Without this proposal, the budget would require $5.6 billion in other solutions this year.

Pays Previous Settle‑Up Obligation. The Governor’s budget provides $1.9 billion to cover the settle‑up obligation from the June 2025 budget (related to 2024‑25). Additionally, the Governor’s budget estimates that the 2024‑25 guarantee is $3.9 billion above the June estimate and provides additional funding to meet the higher requirement.

Projects Large Budget Deficits Moving Forward. The Governor’s budget projects annual deficits exceeding $20 billion over the next three years, including an operating deficit of more than $26 billion in 2027‑28. (These deficits reflect the gap between the cost of currently authorized state programs and forecasted revenues each year.) These projections assume state revenues grow at a modest pace. If the stock market declines or an economic downturn occurs, the deficits would be much larger. Moreover, these estimates exclude the future cost of providing the $5.6 billion payment. Making that payment in next year’s budget, for example, would increase the deficit to about $32 billion (holding other factors constant).

Assessment

Three Distinct Budget Challenges Are Relevant to the Governor’s Proposal. First, the budget faces short‑term forecasting risk. Specifically, the state could adopt a spending level that appears affordable based on current revenue estimates, but becomes unaffordable if revenue falls short of expectations. Regarding Proposition 98, the state might increase school spending based on its higher estimate of the guarantee, only for the guarantee to decline the following year. This scenario poses a risk to the state budget, which likely cannot afford to spend beyond the guarantee. The second challenge concerns future deficits. Chronic deficits like the ones projected by the administration and our office increase the likelihood that the state will (1) be unable to sustain its current priorities, (2) lack funding to address new priorities in the future, and/or (3) face a fiscal crisis if revenues decline significantly. The third challenge involves the risk to school and community college programs from future declines in the guarantee. The state would likely have to reduce these programs if the guarantee declines significantly, which could negatively affect the education students receive. The rest of this section analyzes how the Governor’s proposal affects these three challenges.

The State’s Short‑Term Forecasting Risk Is Considerable. The state’s reliance on tax revenue associated with the stock market poses an acute risk to its revenue forecast. Several signs suggest the stock market is overvalued, and a significant drop most likely would reduce state revenues by tens of billions of dollars. The state, however, cannot predict the timing of such a decline. The potential forecasting errors are larger in 2026‑27 than in 2025‑26 because the 2026‑27 estimates must make assumptions further into the future, and the state does not yet have any tax collection data for the year. The risks for 2025‑26, however, are still significant. The state will not have complete tax collection data for 2025‑26 before adopting the June budget. Moreover, complex accrual policies could assign future revenue gains or losses to 2025‑26 after the year ends.

Proposal Would Lessen Forecast‑Related Risk in 2025‑26. Our office and the administration will release updated revenue forecasts in May that incorporate additional months of tax collection data. The additional data will narrow some of the uncertainty around revenue estimates for 2025‑26 relative to the level in our November outlook and the Governor’s budget. We analyzed previous forecasts and found that, for current‑year revenue estimates, the May forecast is typically within about 4 percent of the year’s final revenue collections. (The range of uncertainty for the budget year is more than twice as large.) This analysis suggests that the state could expect 2025‑26 revenues to be as much as $9 billion higher or lower than the updated estimates it will have in May. If revenues fall short of projections by $9 billion, the guarantee would decrease by about $3.5 billion relative to the May estimate. Under the Governor’s proposal, by comparison, the guarantee could decrease as much as $5.6 billion, and the state could respond by making a smaller settle‑up payment. In other words, the Governor’s proposal likely provides a larger buffer than necessary if the state’s goal is to avoid inadvertently exceeding the guarantee in 2025‑26.

Proposal Worsens the Challenge Posed by Future Budget Deficits. Whereas the proposal reduces short‑term forecasting risk, it will likely worsen future budget deficits. If the revenue estimates meet the Governor’s projections, the state will owe schools $5.6 billion in payments for which no funding is currently set aside. The proposal effectively shifts that cost from this year to future budgets—helping address the current budget problem on a one‑time basis, but adding to the large budget deficits the state is projecting over the next several years.

Proposal Has Limited Value in Protecting Ongoing School Programs. The Governor’s proposal could provide some one‑time protection for ongoing school programs in a future downturn. For example, if the guarantee declines while the state is paying the settle‑up obligation, the state could use the payments to help cover Local Control Funding Formula (LCFF) costs on a temporary basis. The Governor’s proposal, however, does not specify when it will make these payments. More importantly, the payments would be most beneficial when the state experiences a significant revenue decline—exactly when they would be least affordable. The uncertainty about when the state will provide the $5.6 billion and how it will cover the associated costs makes it a weak form of protection for ongoing school programs.

Prohibition on Prior‑Year Spending Reductions Contributes to Actions Making School Funding More Unpredictable. The law prohibiting spending reductions after the year ends was meant to provide greater certainty in calculating the guarantee and allocating school funding. Recent budgets, however, suggest it has had the opposite effect. Rather than establishing a stable base for Proposition 98 calculations, it has led the state to adopt a range of actions to avoid exceeding the prior‑year guarantee. Most notably, this law was part of the rationale for the complicated funding maneuver the state adopted to address the unexpected drop in the 2022‑23 guarantee. It also prompted a complex law that excludes certain school spending from Proposition 98 calculations when the state overestimates the guarantee due to tax‑filing extensions. The June 2025 budget alluded to this law in its explanation for the $1.9 billion settle‑up delay in 2024‑25, and the Governor’s budget makes a similar reference to explain the proposed delay in 2025‑26. For schools, these actions create new uncertainty about when and how the state will allocate Proposition 98 funding.

Recommendations

Alternative Approach Makes Difficult Decisions Now but Reduces Future Budget Challenges. We recommend an alternative to the Governor’s proposal that would continue to mitigate short‑term forecasting risk while also reducing future state costs and better protecting school and community college programs from future downturns. This approach entails additional solutions affecting the non‑Proposition 98 side of the budget this year. Some details of this alternative will depend on the state’s updated revenue estimates in May. The Legislature could adopt the alternative under a range of potential revenue scenarios, but for illustrative purposes, we describe its effects using the Governor’s budget as the baseline.

Fully Fund the Estimate of the Guarantee. We recommend the Legislature allocate enough funding to cover the full cost of the guarantee based on the revenue estimates it adopts. Relative to the Governor’s budget, the state would need to set aside an additional $5.6 billion. Adopting this approach would recognize the full cost of the state’s school funding obligations this year and avoid creating new settle‑up obligations

Deposit Some of the Additional Funding Into the Proposition 98 Reserve. Whereas we recommend setting aside additional funding to meet the guarantee, we do not recommend a corresponding increase in school and community college spending this year. Instead, we recommend (1) making a larger deposit into the Proposition 98 Reserve, and (2) adopting trailer legislation that automatically reduces the deposit if the 2025‑26 guarantee declines relative to May estimates. The savings from any reductions in the deposit would help the state balance the budget. Like the Governor’s proposal, this approach would allow the state to avoid inadvertently exceeding the guarantee if revenues fall short of projections, thereby mitigating the state’s short‑term forecasting risk. We recommend that the Legislature make a total deposit of at least $3.5 billion in 2025‑26. This deposit would provide a buffer to address the likely range of reductions to the 2025‑26 guarantee relative to the state’s May estimate. The Governor’s budget already contains $664 million in Proposition 98 Reserve deposits for 2025‑26, so implementing this recommendation would involve an additional deposit of nearly $2.9 billion.

Use Remaining Funds to Build Additional Resiliency for School Programs. If the state makes an additional $2.9 billion deposit in 2025‑26, it would have $2.7 billion remaining for other one‑time school and community college priorities (relative to the Governor’s budget). We recommend using this funding to build additional resiliency for school programs. One option is to deposit all the remaining funds into the Proposition 98 Reserve, bringing the total balance to $9.7 billion. At this level, the reserve likely would be large enough to protect school and community college programs from the initial effects of a significant downturn. Another option is to provide advance payments to districts toward their 2027‑28 funding allotments, consistent with an approach we outlined in our November 2025 report, The 2026‑27 Budget: Fiscal Outlook for Schools and Community Colleges. This approach would help protect district cash flow by reducing the state’s reliance on deferrals to manage future downturns. A third option is to provide additional funding for district pension costs. The state could structure this payment to reduce pension costs over time or to provide short‑term relief if costs rise above a specified threshold. This approach would build resiliency by reducing future pressure on district budgets.

Adopt Solutions That Address the State’s Underlying Budget Problem. Setting aside enough funding to cover the guarantee means adopting a commensurate level of budget solutions for the non‑Proposition 98 side of the budget this year. (Using the Governor’s budget as a baseline, the state would need $5.6 billion in additional solutions.) As we explained in The 2026‑27 Budget: Overview of the Governor’s Budget, we recommend the Legislature adopt a plan to shrink multiyear deficits that includes spending reductions, revenue increases, or a combination of both. (General Fund tax increases would increase the state’s constitutional requirements further, eroding some of the benefit to the budget’s bottom line.) These additional solutions would entail difficult decisions amidst an already tight budget. Nevertheless, taking this proactive approach would avoid an even more difficult budget situation next year and begin to address the state’s structural deficit.

Consider Repealing Prohibition on Prior‑Year Spending Reductions. Repealing the law on prior‑year spending reductions would mitigate some of the risk motivating the Governor’s settle‑up proposal. It would also reduce pressure to use funding maneuvers, spending exclusions, settle‑up delays, or similar actions that complicate state budgeting and make school funding less predictable. If the Legislature wanted to implement the recommendation in a way that protected local district budgets, it could replace the law with a less strict alternative. Specifically, it could allow reductions through state‑level accounting adjustments while still prohibiting reductions that require districts to return previous funding.

School Spending Plan

In this section, we examine the Governor’s plan for allocating Proposition 98 funds to schools. First, we describe the Governor’s overall approach and explain the most notable spending proposals. Next, we assess the merits of this approach. Finally, we provide our recommendations for the Legislature.

Governor’s Budget

Overall Structure

Contains Nearly $9.7 Billion in New School Spending Proposals. Of the new spending, the Governor proposes to allocate more than $5.9 billion for one‑time activities and $3.7 billion for ongoing augmentations (Figure 7). From an accounting perspective, nearly all of this spending ($8.1 billion) is attributable to the increase in the 2026‑27 guarantee. Most of the remaining $1.6 billion relates to 2024‑25, reflecting the increase in the guarantee and the settle‑up payment being made that year. Separately from these proposals, the Governor’s budget also provides $1.2 billion in ongoing Proposition 98 funds to offset the expiration of various one‑time funds that paid for school programs in the 2025‑26 budget. (The figure excludes this backfill because it is a required adjustment rather than a new proposal.)

Figure 7

Governor’s Budget Has $9.7 Billion in School

Spending Proposals

(In Millions)

|

Ongoing |

|

|

Local Control Funding Formula COLA (2.41 percent) |

$1,893 |

|

Community schools |

1,000 |

|

Special Education |

509 |

|

COLA for select categorical programs (2.41 percent)a |

230 |

|

Expanded Learning Opportunities Program |

62 |

|

Necessary Small Schools |

31 |

|

COE funding to support districts and charter schools |

13 |

|

Charter School Facility Grant Program |

7 |

|

FCMAT salary adjustment |

1 |

|

California School Information Services |

1 |

|

Science performance tasks |

1b |

|

K‑12 High Speed Network |

1 |

|

Subtotal |

($3,749) |

|

One Time |

|

|

Discretionary block grant |

$2,796 |

|

Deferral paydown |

1,875 |

|

Learning Recovery Emergency Block Grant |

757 |

|

Teacher Residency Grant Program |

250 |

|

Dual enrollment |

100 |

|

Kitchen infrastructure and training |

100 |

|

Reading difficulties screening |

40 |

|

Wildfire‑related support for schools |

23 |

|

Subtotal |

($5,941) |

|

Total Proposals |

$9,690 |

|

aApplies to Special Education, State Preschool, Child Nutrition, Equity Multiplier, K‑12 Mandates Block Grant, Charter School Facility Grant Program, Foster Youth Services Coordinating Program, Adults in Correctional Facilities, American Indian Education Centers, Child and Adult Care Food Program, and American Indian Early Childhood Education. bReflects $890,000 ongoing, beginning in 2025‑26. |

|

|

COLA = cost‑of‑living adjustment; COE = county office of education; and FCMAT = Fiscal Crisis Management Assistance Team. |

|

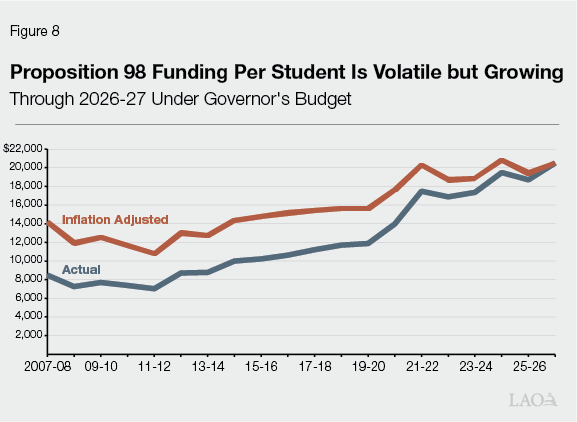

Funding Per Student Near Previous Inflation‑Adjusted Peak. Under the Governor’s budget, total Proposition 98 funding for schools would be $20,512 per student in 2026‑27, an increase of $1,887 (10.1 percent) over the 2025‑26 budget level. This funding level is an all‑time high in unadjusted dollars (Figure 8). Adjusting for inflation, the 2026‑27 funding level is about $300 per student below the previous peak (2024‑25).

Major Ongoing Proposals

$2.1 Billion for Statutory COLA. The state calculates the COLA rate using a federal price index that tracks goods and services purchased by state and local governments during the preceding year. For 2026‑27, the administration estimates the statutory rate is 2.41 percent. The Governor’s budget provides $2.1 billion to cover the associated cost—$1.9 billion for LCFF and $230 million for several other programs.

$1 Billion for Community Schools Grants. The Governor’s budget includes $1 billion in ongoing funding for schools to implement the community schools model. The administration indicates that this funding is intended to provide ongoing support to the roughly 2,500 schools that have received one‑time funding to implement the model and to expand the model to additional school sites. The accompanying trailer legislation also indicates that moving forward, the state will provide the statutory COLA for this program.

$509 Million for Special Education. Most state special education funding is provided through a base rate formula that is allocated to Special Education Local Plan Areas (SELPAs)—typically regional consortia of local education agencies that coordinate special education funding and services. The formula distributes funding based on total student attendance rather than direct measures of special education costs. The Governor’s budget provides $509 million to increase the special education base rate to $999 per student. For most SELPAs, this would be a 6.3 percent increase beyond the statutory COLA. With this augmentation, all SELPAs would receive the same rate, equalizing per‑pupil funding across the state.

Major One‑Time Proposals

$2.8 Billion for Discretionary Block Grant. The Governor proposes $2.8 billion for the Student Support and Professional Development Discretionary Block Grant. This funding would supplement the $1.8 billion provided for a similar grant in the June 2025 budget. Districts would receive funding based on their average daily attendance in 2025‑26—$512 per student under current attendance estimates. The grant would not have specific spending requirements, but trailer legislation suggests several potential uses, including teacher professional development, teacher recruitment and retention, career pathways, dual enrollment programs, and “addressing rising costs.” Districts could spend their funds at any time before June 30, 2030.

$1.9 Billion to Eliminate Payment Deferral. The June 2025 budget deferred $1.9 billion from 2025‑26 to 2026‑27 by moving a portion of the payment schools would typically receive in June 2026 to July 2026. The Governor’s budget provides $1.9 billion to eliminate the deferral and restore the regular payment schedule beginning in 2026‑27.

$757 Million for the Learning Recovery Emergency Block Grant (LREBG). The state provided $7.9 billion for the LREBG in the 2022‑23 budget to mitigate the learning loss and social disruption students experienced during the pandemic. The subsequent budget reduced the grant by $1.1 billion to address a revenue shortfall. It also established a plan to restore the grant in three equal installments across 2025‑26, 2026‑27, and 2027‑28. The June 2025 budget provided the first installment of $379 million. The Governor’s budget proposes $757 million—two more installments—to restore the grant a year earlier than planned. Like the original grant, districts would receive funding based mainly on their counts of English learners and low‑income students. The proposal also maintains the deadline requiring districts to spend their funds by June 30, 2028.

Assessment

Overall Structure

Spending Plan Builds Upon Estimates of the Guarantee That Seem Risky. The Governor’s spending proposals are predicated on estimates of state revenues and the guarantee that are substantially higher than the June 2025 budget level. The state faces a significant risk that some of these increases will not be sustained, eroding its capacity for new school spending. As we explain in The 2026‑27 Budget: Overview of the Governor’s Budget, the state could reduce its risks by adopting revenue estimates that account for a potential stock market drop. The State would have to pare back some of the Governor’s proposals under this approach, but it would reduce the risk that revenues fall far short of budget estimates. A spending plan that uses the Governor’s revenue estimates can still mitigate risk in other ways, but it requires careful budgeting—not making too many new commitments, building up reserves, and not committing all of the new funding next year to ongoing program increases.

Contains a Notable One‑Time Cushion. The Governor’s budget allocates $4 billion in ongoing 2026‑27 funds for one‑time spending. The underlying funding will be freed up in 2027‑28 when this one‑time spending ends. This budgeting approach creates a cushion that protects ongoing programs. For example, if the guarantee were to decrease by as much as $4 billion in 2027‑28, the state could absorb the drop without reducing programs or deferring payments. This cushion is large by historical standards, and seems especially prudent this year given the significant risks to state revenues. The state took a similar approach when it adopted the 2022‑23 budget, which included a $3.5 billion cushion. When the guarantee declined sharply in the following year, the cushion helped the state avoid reductions to ongoing programs.

Contains a Reasonable Mix of Flexible Funding and Targeted Proposals. The Governor’s budget dedicates about two‑thirds of the new spending to proposals that provide districts with flexible funding—mainly the LCFF COLA and discretionary block grant. Flexible funding allows districts to implement programs tailored to their individual circumstances and local priorities. It also helps districts manage cost increases and develop cohesive local programs. The budget dedicates the remaining one‑third for proposals that require districts to undertake specific activities (primarily the community schools grant and LREBG augmentation). This targeted spending helps ensure districts use their funding for activities the state considers its highest priorities. This approach—proposals in both areas but with greater emphasis on flexible funding—seems reasonable. It could allow districts to address their cost pressures and a few core state priorities without being overwhelmed by additional spending requirements.

Nearly All of the Targeted Proposals Build on Existing Programs. The Governor’s budget does not introduce any significant new programs. Instead, nearly all the proposals extend or expand existing programs. This budgeting approach encourages districts to prioritize existing activities. For the upcoming hearings, the Legislature could focus its review of these proposals on a few core issues: (1) whether the underlying problem remains unaddressed, (2) whether the existing program is meeting its objectives, and (3) whether additional funding would allow districts to address the problem more effectively.

Major Ongoing Proposals

Funding a COLA Helps Districts Maintain Programs. Districts face cost increases in many parts of their budgets. Most districts spend roughly 80 percent of their operating budgets on personnel costs, including salaries, health benefits, and pensions. Districts have faced pressure in all of these areas over the past few years, including pressure to increase salaries to keep up with inflation. Districts also face higher costs in a few other areas, including notable increases for utilities and insurance. Funding the statutory COLA is a straightforward way to help districts address these costs, balance their budgets, and sustain local programs.

COLA Estimate Is More Uncertain Than Usual. The federal government typically publishes the eight quarters of data used to calculate the COLA on a standard schedule. Due to the fall 2025 government shutdown, the last few quarters of data have been delayed. Specifically, the sixth quarter (normally published in October) was not available in time for the Governor’s budget, and the seventh quarter (normally published in January) will not be available until February 20. These delays make the COLA estimate more uncertain and could lead to larger changes in the coming months. For each 0.5 percent increase or decrease in the statutory rate, the associated costs for school programs would change by about $450 million. Based on the current federal schedule, the state will receive the final quarter and finalize the rate on April 30.

Community Schools Proposal Raises Several Issues to Consider. The state has provided $4.1 billion in one‑time Proposition 98 funding to support the implementation and expansion of the community schools model. This funding has provided multiyear grants to approximately 2,500 schools across four cohorts of grantees, a statewide and regional technical assistance system, and grants to county offices of education to coordinate services for community schools within their counties. These funds were provided with the expectation that school districts would be responsible for sustaining their community schools model after the grant funding expired. In assessing the proposal, the Legislature may want to consider the rationale for creating a new ongoing program for current grantees. It may also want to weigh the trade‑offs of providing dedicated, ongoing funding for community schools against other alternatives, such as a comparable LCFF increase. We will analyze the proposal in greater detail in a forthcoming publication.

Special Education Increase Would Help Address District Cost Pressures. School districts cover special education costs through a combination of federal categorical, state categorical, and local unrestricted funding (largely LCFF). Over the past two decades, special education costs have increased faster than federal and state categorical funding, requiring districts to rely more on local funds. Based on our analysis of historical spending data, we estimate the share of special education costs covered by local funds has increased from roughly 50 percent to roughly 60 percent over the past decade. Providing additional base special education funding would help address these cost increases and free up local funding for other purposes. In addition, the proposal would achieve a long‑term state goal of equalizing special education base rates. The state used special education increases from 2020‑21 through 2022‑23 to address historical inequities in base rates. Currently, all SELPAs but one receive the same per‑student base rate. Under the Governor’s proposal, all SELPAs would receive the same rate.

Budget Overestimates the Cost of Special Education Proposal. The Governor’s budget likely overestimates the higher costs associated with funding higher special education base rates. Based on the statewide student attendance estimates in the Governor’s budget, we estimate that increasing base rates to $999 per student would cost $325 million—$184 million less than the administration’s estimate.

Major One‑Time Proposals

Districts Could Use Discretionary Grants for Various Costs and Programs. We spoke with local leaders and explored how districts might use one‑time discretionary funding. Some districts likely would use the funding to help implement the state’s new curriculum for teaching literacy and mathematics, including costs for teacher training and instructional materials. Additionally, many districts would likely extend programs they previously funded with one‑time federal grants. (The federal government provided more than $20 billion in one‑time grants during the pandemic, but these funds expired in September 2024.) These programs include coaching for teachers, counseling and tutoring for students, attendance improvement initiatives, and Multi‑Tiered Systems of Support (a framework for providing supports to students that vary based on their academic and behavioral needs). A few districts likely would address infrastructure‑related priorities, such as refreshing technology and upgrading facilities for transitional kindergarten. We also think many districts would use some of their grants to offset revenue reductions from declining enrollment. While this approach could delay necessary budget adjustments, it might be reasonable if it allows districts to implement expenditure reductions gradually. Districts might also consider using their grants to cover fiscal liabilities, including unfunded retiree health care obligations and one‑time and ongoing liability insurance costs.

Eliminating Deferrals Is Prudent. Conceptually, deferrals are similar to borrowing from future Proposition 98 funds. The Governor’s proposal to eliminate them would align the ongoing costs of school programs with the ongoing funding needed to support them. This realignment would ease pressure on future budgets, improve cash flow for districts, and simplify state and school accounting.

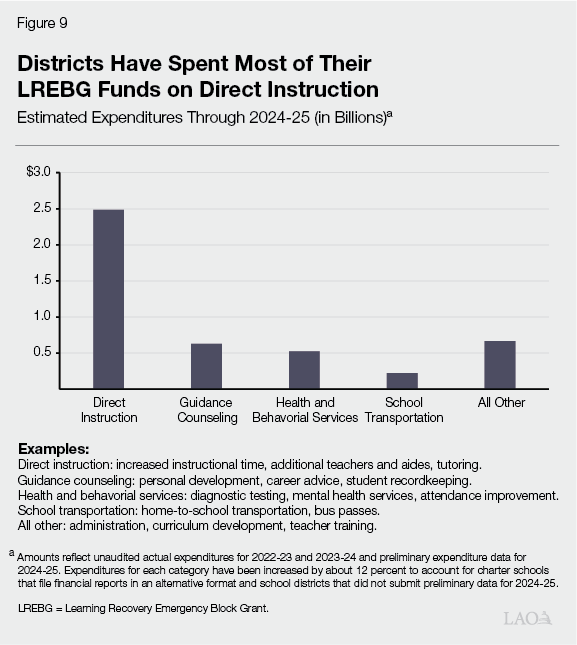

Districts Have Spent Most of Their LREBG Funds on Instruction. Based on our analysis of district fiscal data, we estimate districts spent about $4.5 billion in LREBG funds through 2024‑25 (covering the first three years of the program). More than half of this spending involved direct instruction, such as increased instructional time, additional teachers and aides, and tutoring (Figure 9). Most of the other spending supported student services, such as counseling and transportation. Although the state does not collect detailed information on district use of the grant, the emphasis on direct instruction and student services suggests that districts are prioritizing initiatives that could address learning loss. The spending reported through 2024‑25 represents approximately two‑thirds of the initial grant amount. The remainder—approximately $2.3 billion—remained unspent at the end of 2024‑25. Districts, however, are required to adopt multiyear plans for how they will spend these funds by 2027‑28.

Restoring the LREBG Ahead of Schedule Has Merit. The original impetus for the grant—helping students recover from learning loss—remains a significant concern. State test scores show that student achievement has been improving but remains below pre‑pandemic levels. Adopting the Governor’s proposal to accelerate this restoration would give districts greater certainty about their final funding levels. This approach seems especially important if the state maintains the original spending deadline. The LREBG requires districts to undertake a lengthy planning process, including (1) conducting a needs assessment, (2) gathering community input, (3) developing measures of student engagement and performance, and (4) explaining how research or other evidence supports their plans. If the state does not make the final payment until 2027‑28, districts would not have time for a thoughtful planning process. Accelerating the restoration also eliminates the need for another payment in 2027‑28.

Recommendations

Maintain Large One‑Time Cushion if Adopting Governor’s Revenue Estimates. If the Legislature adopts lower revenue estimates, it would mitigate some of the risks that the Governor’s budget seeks to address. Under this approach, prudent budgeting would mean paring back spending proposals to align with the lower guarantee. Other tools for budget resilience (such as reserves and one‑time cushions) would be less necessary. If the Legislature uses the higher revenue estimates in the Governor’s budget, however, we recommend a one‑time cushion at least as large as the Governor’s plan ($4 billion). Having a significant cushion means the budget has some capacity to accommodate a lower guarantee without disrupting ongoing school programs. This approach means the budget would include a mix of one‑time and ongoing spending, which the Legislature could use to fund the Governor’s proposals, its own priorities, or some combination of both.

Maintain the Same General Mix of Flexible Funding and Targeted Proposals. The Governor’s plan to allocate most of the new spending to flexible grants while reserving a smaller portion for targeted proposals is a reasonable way to build the budget. Whether the Legislature directs new spending toward the Governor’s priorities or to other priorities, we recommend maintaining a roughly similar mix of flexible and targeted proposals.

Adopt Funding for COLA Based on Final Statutory Rate. Although we recommend the Legislature remain cautious about new ongoing spending, our November outlook concluded that the state could afford to cover the COLA even under our lower revenue estimates. We recommend prioritizing the COLA over other ongoing spending and funding the final statutory rate unless revenue estimates decline significantly by May. Funding the COLA would help districts address the cost increases they face.

Adopt Special Education Increase but Reduce Cost Estimate. Given statewide increases in special education costs, we think increasing special education base rates is a reasonable way to address local cost pressures. We recommend that the Legislature adopt this proposal, but use a lower cost estimate. (We estimate the cost is $325 million, but the number likely will change in May when the state has updated attendance and COLA data.) Providing additional special education funding would reduce the need for districts to rely on general purpose funding, such as LCFF, to cover rising costs.

Adopt the Governor’s Major One‑Time Proposals. The Governor’s three major one‑time proposals seem reasonable, and we recommend adopting them. Specifically, we recommend adopting the discretionary block grant, which could help districts advance local programs and address various costs. Whereas the Governor proposes $2.8 billion, other amounts could be reasonable based on revised estimates of the guarantee. Regardless of the final amount, we recommend refining the intent language to add fiscal liabilities, infrastructure, and temporary costs to the suggested uses—the types of expenditures that one‑time funds are well suited to address. We also recommend adopting the proposal to eliminate the payment deferral, which would ease future budget pressure. Finally, we recommend adopting the proposal to restore the remaining funds for LREBG. This proposal would help districts meet the upcoming expenditure deadline and reduce costs in 2027‑28.

Appendix: Summary of Assessment and Recommendations

The Minimum Guarantee

Assessment

- Revenue Risks. The stock market poses a notable risk to General Fund revenues. Several signs suggest the market is overvalued, and a significant decline likely would reduce state revenues by tens of billions of dollars. The revenue estimates in the Governor’s budget do not account for this risk.

- Proposition 98 Sensitivity. The Proposition 98 guarantee is moderately sensitive to revenue changes and would drop about 40 cents for each $1 of lower revenue in 2025‑26 or 2026‑27.

- Budget Preparation. We recommend that the Legislature prepare for the possibility that the guarantee is billions of dollars lower by (1) being cautious about new spending commitments, (2) building reserves and other tools to protect existing school programs, and (3) using the upcoming hearings to identify proposals that could be delayed, reduced, or rejected if the guarantee drops.

- Proposition 98 Reserve. The $4.1 billion deposit under the Governor’s budget is a key tool for protecting school programs because the reserve is flexible and can be accessed relatively quickly.

- Property Tax Estimates. The administration’s estimates are reasonable.

Settle Up

Assessment

- Budget Challenges. Three distinct budget challenges are relevant to the Governor’s proposal to delay a $5.6 billion settle‑up payment in 2025‑26:

- Managing short‑term forecasting risk (overcommitting to school spending if revenues are lower than projected).

- Addressing future budget deficits. (The state budget faces deficits averaging more than $20 billion annually over the next few years.)

- Protecting school programs from future declines in the guarantee.

- Short‑Term Forecasting Risk. The proposal mitigates short‑term forecasting risk because the guarantee could drop by as much as $5.6 billion and the state could respond by reducing the eventual settle‑up payment. Past experience suggests the 2025‑26 guarantee is unlikely to drop by more than $3.5 billion relative to May estimates.

- Future Deficits. The proposal effectively shifts $5.6 billion in costs from this year to future budgets—helping address the current budget problem on a one‑time basis but adding to the large budget deficits the state faces in the future.

- School Programs. The future settle‑up payments could help support school programs the next time the guarantee drops, but they are a weak form of protection. The payments would be most beneficial when the state experiences a significant revenue decline—exactly when they would be least affordable.

- Prior‑Year Spending Adjustments. A state law that prohibits school spending adjustments after the year ends is one of the motivations for the Governor’s proposal. Rather than making school funding more predictable, the law seems to have prompted the state to adopt settle‑up delays and other actions that create new uncertainty about when and how the state will allocate funding.

Recommendations

- Adopt Alternative Approach. The alternative addresses the risk of overcommitting school funding and reduces future budget risks and challenges. However, it involves some difficult decisions for the non‑Proposition 98 side of the budget this year. Although the details will vary based on updated revenue estimates in May, the core elements of the alternative include the following:

- Setting aside enough funding to cover the full estimate of the guarantee, rather than delaying $5.6 billion in costs to the future.

- Making a Proposition 98 Reserve deposit of at least $3.5 billion in 2025‑26 ($2.9 billion more than the Governor’s budget proposes), pending additional revenue information. The state would reduce this deposit to the extent the guarantee falls short of its May estimates.

- Using the remaining funds to build additional resiliency for school programs, such as by making further reserve deposits, providing an advance payment, or addressing district pension costs.

- Adopting budget solutions that address the state’s structural deficit—spending reductions for non‑Proposition 98 programs or revenue increases.

- Prior‑Year Spending Adjustments. Consider repealing the prohibition on prior‑year spending reductions to mitigate the risks posed by drops in the guarantee. The state could continue to prohibit reductions that would require districts to return previous payments.

School Spending Plan

Assessment of Overall Structure

- Budget Starting Point. The Governor’s budget builds its spending package on estimates of the state revenues that do not account for the elevated risk of a stock market downturn. Using lower estimates would mean a lower guarantee and less new spending but also less risk. Using the Governor’s estimates heightens the importance of managing risk in other ways.

- Mix of One‑Time and Ongoing Spending. The Governor’s budget includes $3.7 billion in ongoing spending and $5.6 billion in one‑time spending. Of the one‑time amount, $4 billion is paid with ongoing 2026‑27 funds. This approach builds a cushion that would protect programs if the guarantee declines in the future.

- Flexible and Targeted Spending. The Governor’s budget allocates about two‑thirds of the proposed spending to flexible grants and one‑third to targeted grants with spending requirements. This is a reasonable mix that could help districts cover their costs while addressing a few state priorities.

- Relation to Existing Programs. Nearly all the targeted proposals expand or extend existing programs rather than create new initiatives.

Assessment of Specific Proposals

- Cost‑of‑Living Adjustment (COLA). Funding the statutory COLA would help districts manage cost pressures ranging from salaries and benefits to utilities and insurance. The COLA rate estimate (2.41 percent) is more uncertain than usual due to federal delays, but final data should be available in late April.

- Community Schools. Core issues to consider include (1) whether districts should be responsible for sustaining community schools with existing funds, (2) the rationale for creating a new ongoing program, and (3) the trade‑off between funding for community schools and increases in other programs.

- Special Education. The proposed $59 per‑student increase (about 6 percent) would supplement the COLA and help districts cover costs that have risen faster than inflation. We estimate the associated cost is $325 million—$184 million less than the Governor’s budget estimates.

- Discretionary Grant. Districts could use this $2.8 billion grant for various costs and programs, including (1) implementing new state curriculum, (2) extending programs previously funded with one‑time federal funds, (3) making infrastructure improvements, (4) managing enrollment declines, and (5) covering fiscal obligations and liabilities.

- Payment Deferral. Using $1.9 billion to eliminate the June 2025 payment deferrals is prudent because it aligns ongoing program costs with the funding necessary to support them.

- Learning Recovery Emergency Block Grant. Providing $757 million to accelerate the restoration of this grant would help districts sustain learning recovery efforts and meet an upcoming expenditure deadline. It would also reduce future state costs.

Recommendations

- Budget Structure:

- Consider using revenue estimates that account for stock market risks. Alternatively, maintain a large one‑time cushion if building a budget based on the Governor’s revenue estimates.

- Maintain the same general mix of flexible funding and targeted proposals.

- Specific Proposals:

- Adopt funding for the statutory COLA rate unless revenue estimates deteriorate significantly by May.

- Adopt the special education increase but reduce the cost estimate to $325 million.

- Adopt the discretionary block grant proposal but modify the list of priorities to include fiscal liabilities, infrastructure, and temporary costs. Consider increasing or decreasing the amount in response to changes in the guarantee.

- Adopt the proposal to eliminate payment deferrals.

- Adopt the proposal to restore the Learning Recovery Emergency Block Grant.