Kenneth Kapphahn

November 19, 2025

The 2026-27 Budget

Fiscal Outlook for Schools and

Community Colleges

Summary

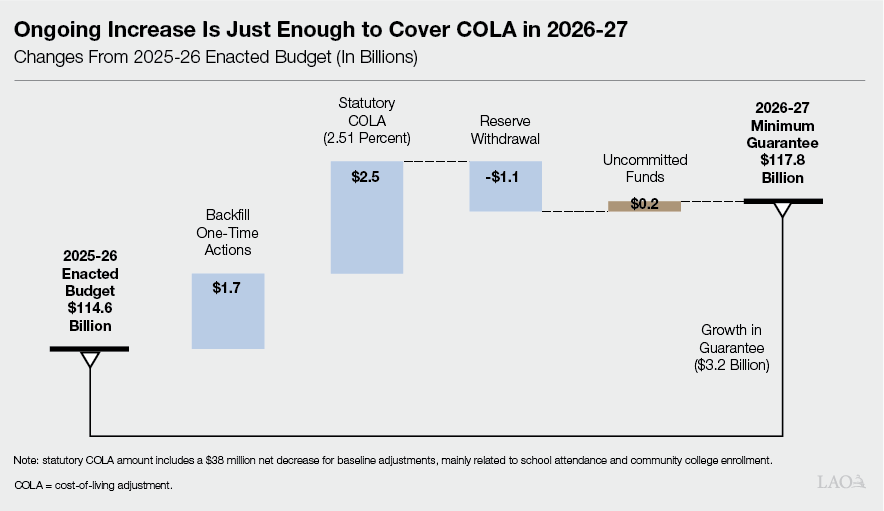

Large One‑Time Windfall and Modest Ongoing Increase Projected for School and Community College Funding. Each year, the state calculates a “minimum guarantee” for school and community college funding based on the formulas established by Proposition 98 (1988). Under our forecast, increases to the guarantee in 2024‑25 and 2025‑26, coupled with a preexisting payment obligation, require the state to provide nearly $7.4 billion in one‑time funds for schools and community colleges. For 2026‑27, we estimate the guarantee is $117.8 billion, an increase of $3.2 billion (2.8 percent) from the previously enacted level. This growth—combined with a required reserve withdrawal—would be just enough to fund a 2.51 percent statutory cost‑of‑living adjustment (COLA) (see figure below). The state could use the one‑time funds to build budget resiliency, which seems especially important given the risks of a stock market downturn. Some promising options include eliminating payment deferrals, providing districts with an advance payment toward their future funding allocations, and accelerating the restoration of a grant the state previously reduced. These actions would help protect ongoing programs if state revenues decline.

Introduction

Report Provides Our Fiscal Outlook for Schools and Community Colleges. State budgeting for schools and the California Community Colleges is governed largely by Proposition 98. The measure establishes an annual funding requirement commonly known as the minimum guarantee. In this report, we estimate the guarantee and examine its implications for school and community college programs. First, we review the formulas that determine the guarantee. Next, we analyze recent revenue trends and explain their effect on the guarantee in 2024‑25 and 2025‑26. Third, we estimate the guarantee from 2026‑27 through 2029‑30 based on our revenue forecast. Finally, we assess the funding available for school and community college programs and provide some considerations for the Legislature in the upcoming year. (The 2026‑27 Budget: California’s Fiscal Outlook contains our outlook for the overall state General Fund budget.)

Background

Proposition 98 Establishes an Education Budget Within the Overall State Budget. By requiring the state to allocate a specific amount of funding each year, Proposition 98 creates a dedicated budget for schools and community colleges. The guarantee represents the minimum revenue the Legislature must make available in this budget. Specific school and community college programs, in turn, correspond to the annual expenditures. The largest school program is the Local Control Funding Formula (LCFF), and the largest community college program is the Student Centered Funding Formula (SCFF). During strong economic times, the guarantee often increases more quickly than the cost of existing programs. In such cases, funding is available to expand programs (similar to a surplus). Conversely, in weaker economic times, the guarantee often falls below the cost of existing programs, and the state must either provide more funding than the guarantee or reduce spending on programs (similar to a deficit). The school and community college budget also includes a dedicated reserve account to help stabilize funding over time. The rest of this section provides additional details on the guarantee, program costs, and the reserve.

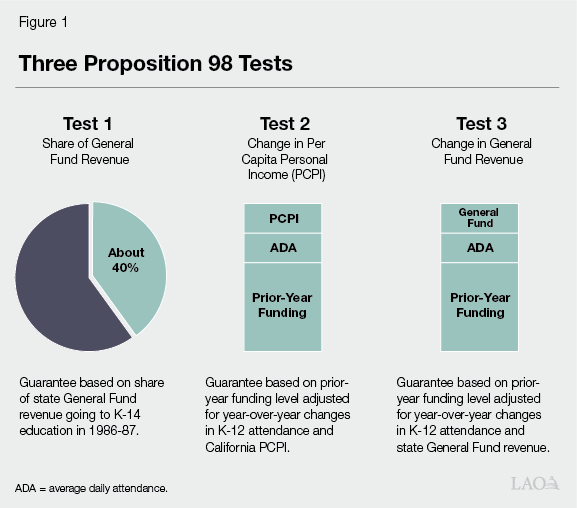

Proposition 98 Guarantee Depends on Various Inputs and Formulas. The California Constitution sets forth three main “tests” (formulas) for calculating the Proposition 98 guarantee. Each test takes into account certain inputs, including General Fund revenue, per capita personal income, and student attendance (Figure 1). Whereas Test 1 links school funding to a minimum share of General Fund revenue, Test 2 and Test 3 build upon the funding provided in the previous year. The Constitution contains rules for comparing the tests, with one becoming operative and determining the guarantee for that year. With a two‑thirds vote of each house of the Legislature, the state can suspend the guarantee and provide less funding than the formulas require in a given year. The state funds the guarantee through a combination of state General Fund and local property tax revenue.

Proposition 98 Guarantee Is a Moving Target. The state estimates the guarantee when it enacts the budget, but this calculation typically changes as the state updates its revenue estimates and other inputs. The state recalculates the guarantee at the end of each year, then recalculates it again at the end of the following year. This schedule means each budget includes new estimates for the previous, current, and upcoming years. When the guarantee exceeds the initial estimate, the state makes additional payments (known as “settle up”) to meet the higher requirement. The state finalizes its prior‑year calculation through a statutory process called certification. This process involves publishing the underlying Proposition 98 inputs and providing a period for public comment and review. The most recently certified year is 2023‑24.

School and Community College Programs Are Adjusted for Enrollment Changes and COLA. The LCFF, SCFF, and many other school and community college programs allocate funding through per‑student formulas. As enrollment changes, the costs for these programs tend to move in tandem. For school programs, changes in the school‑age population are usually the most significant factor, though policy decisions—such as the expansion of transitional kindergarten—also have notable effects. For the community colleges, enrollment changes reflect a combination of factors, including demographic and economic trends, community college districts’ enrollment management strategies, and state decisions regarding enrollment growth funding. Separate from enrollment changes, the state typically provides a COLA for existing programs. The COLA rate depends on a federal price index that tracks the cost of goods and services purchased by state and local governments nationwide. The state finalizes the COLA rate for the upcoming year using the data available in May. For school programs, state law automatically provides the COLA unless the guarantee cannot cover the associated costs. For community colleges, the state typically provides the same COLA as it does for schools.

Proposition 98 Reserve Helps Stabilize Funding. The California Constitution establishes a reserve specifically for school and community college funding—the Public School System Stabilization Account (Proposition 98 Reserve). The Constitution requires the state to deposit Proposition 98 funds into this reserve when it receives significant tax revenue from capital gains and the guarantee is growing quickly relative to inflation. It requires withdrawals when the guarantee is not keeping pace with inflation. The state can use these withdrawals for any school or community college purpose. The state updates its estimates of any required deposits or withdrawals whenever it recalculates the guarantee. Separate from these constitutional provisions, a state law caps the local reserves held by medium and large school districts when the Proposition 98 Reserve balance exceeds 3 percent of the funding allocated to schools in the previous year.

2024‑25 and 2025‑26 Updates

Revenue Trends

Corporation and Sales Tax Receipts Reflect Weak Economic Conditions. Both the California and U.S. economies currently face significant headwinds. For example, borrowing costs—a key factor in business expansions and major consumer purchases—remain high. New tariffs on imports into the U.S. are increasing costs for businesses and consumers. Surveys report that consumers are pessimistic about economic growth and their personal finances. Reflecting these conditions, two broad measures of California’s economy—payroll job growth and sales of taxable goods—have been flat over the past year. Consistent with these trends, state receipts from the sales tax and corporation tax (adjusted for recent policy changes) have posted below‑average growth in recent months.

Income Tax Receipts Have Been Strong, Reflecting Exuberance Around Artificial Intelligence (AI). Income tax receipts, by contrast, have been growing at an annualized rate of more than 10 percent for the past several months. This trend reflects investor enthusiasm around the advance of AI, which has pushed the stock market to record highs and boosted compensation among the state’s tech workers. The S&P 500 has risen 50 percent over the past two years, with most of the gains driven by a few large tech companies. These companies have committed hundreds of billions of dollars to new datacenters and offered extraordinary pay packages to recruit AI researchers. This spending, coupled with sizable gains to investors and tech company employees via stock options, is boosting state income tax receipts.

Funding Changes

Proposition 98 Guarantee Revised Up in 2024‑25 and 2025‑26. We estimate the guarantee is up $2.2 billion (1.8 percent) in 2024‑25 and $3.8 billion (3.3 percent) in 2025‑26 compared with the estimates in the June 2025 budget (Figure 2). These upward revisions mainly reflect higher General Fund revenue estimates. Test 1 is operative in both years, meaning the guarantee automatically grows by about 40 cents for each $1 of higher revenue. In 2024‑25, the guarantee increases even more because the state makes a larger “maintenance factor” payment. (Maintenance factor is a constitutional obligation created under certain conditions, including when the state suspends the guarantee. The state pays this obligation when it experiences strong year‑over‑year revenue growth. The payments are part of the guarantee.) After making this payment, the remaining maintenance factor obligation would be $1.7 billion. Our estimates of local property tax revenue are also slightly higher in 2024‑25 and 2025‑26 based on updated data. In Test 1 years, increases in local property tax revenue directly increase the guarantee.

Figure 2

Guarantee Revised Up in Prior and Current Year

(In Millions)

|

2024‑25 |

2025‑26 |

||||||

|

June |

November |

Change |

June |

November |

Change |

||

|

Minimum Guarantee |

|||||||

|

General Funda |

$87,628 |

$89,520 |

$1,892 |

$80,738 |

$84,326 |

$3,588 |

|

|

Local property tax |

32,317 |

32,581 |

263 |

33,821 |

34,029 |

208 |

|

|

Totals |

$119,946 |

$122,101 |

$2,155 |

$114,558 |

$118,355 |

$3,796 |

|

|

General Fund tax revenue |

$209,813 |

$211,822 |

$2,009 |

$204,027 |

$213,705 |

$9,678 |

|

|

Maintenance factor payment |

5,466 |

6,619 |

1,154 |

— |

— |

— |

|

|

aIncludes maintenance factor payment. |

|||||||

Program Cost Estimates Reduced in 2024‑25 and 2025‑26. For 2024‑25, updated data from the California Department of Education show that LCFF costs were $466 million lower than the June 2025 estimates (Figure 3). We estimate that much of this decrease is ongoing, and our LCFF cost estimate for 2025‑26 is $295 million below the June estimate. In contrast, our estimates for other school and community college programs are slightly higher than the June estimates in both years.

Figure 3

Additional Funding Required in 2024‑25 and 2025‑26

(In Millions)

|

2024‑25 |

2025‑26 |

||||||

|

June |

November |

Change |

June |

November |

Change |

||

|

Minimum Guarantee |

$119,946 |

$122,101 |

$2,155 |

$114,558 |

$118,355 |

$3,796 |

|

|

Allocations |

|||||||

|

Local Control Funding Formulaa |

$81,606 |

$81,140 |

‑$466 |

$84,480 |

$84,186 |

‑$295 |

|

|

Other K‑14 programs |

35,968 |

36,041 |

73 |

30,533 |

30,619 |

86 |

|

|

Reserve deposit/withdrawal (+/‑) |

455 |

1,382 |

927 |

‑455 |

‑270 |

185 |

|

|

Totals |

$118,029 |

$118,562 |

$533 |

$114,558 |

$114,535 |

‑$24 |

|

|

Additional Funding Owed (Settle Up) |

$1,917 |

$3,539 |

$1,622 |

— |

$3,820 |

$3,820 |

|

|

aIncludes school districts, charter schools, and county offices of education. |

|||||||

Larger Reserve Deposit Required in 2024‑25. We estimate that capital gains revenues in 2024‑25 are more than $1 billion above the June 2025 estimate. These increased capital gains require the state to deposit an additional $927 million into the Proposition 98 Reserve. For 2025‑26, we estimate the state will make a mandatory withdrawal of $270 million from the reserve—$185 million less than the June estimate. The State Constitution requires this withdrawal because the guarantee—though significantly above the previous estimate—is below the inflation‑adjusted 2024‑25 level. Accounting for these changes, the reserve would have a balance of $1.1 billion at the end of 2025‑26.

State Has a Preexisting Obligation Related to 2024‑25. The June budget approved funding for schools and community colleges at a level $1.9 billion below the estimated guarantee for 2024‑25. We assume the state will provide a settle‑up payment to meet this obligation in the upcoming budget. This assumption aligns with state practice since 2018‑19, which is to provide any required funding before certifying the guarantee. Trailer legislation accompanying the budget indicates the state will use the $1.9 billion to support existing programs, eliminate payment deferrals, and/or avoid future deferrals. (If the state does not make this payment in the upcoming budget, a fallback provision in the certification law would convert the obligation into a per‑student grant that would be paid on a schedule determined by the Department of Finance.)

State Required to Provide Nearly $7.4 Billion in One‑Time Funding. After accounting for increases in the guarantee, lower program costs, larger reserve deposits, and the preexisting obligation from 2024‑25, school and community college funding is $3.5 billion below our estimate of the guarantee in 2024‑25 and $3.8 billion below in 2025‑26. Across the two years, the state would need to provide nearly $7.4 billion to meet the guarantee. The Legislature could allocate this one‑time funding for any school or community college purposes.

Multiyear Outlook

Revenue Assumptions

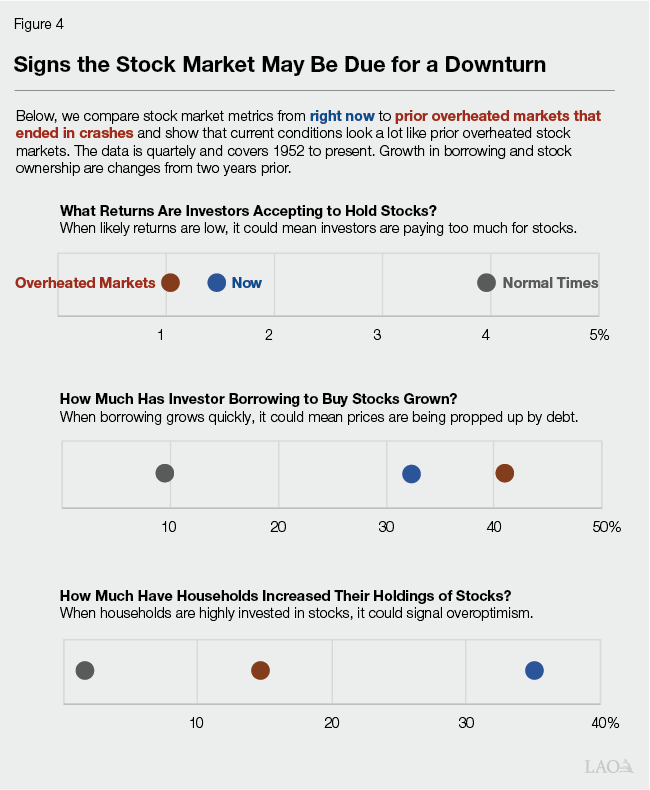

Several Signs Suggest the Stock Market May Be Overvalued. Several indicators suggest that enthusiasm for AI is pushing the stock market to unsustainable levels. For example, measures of whether stocks are “expensive” are at historically high levels, investors are borrowing more to buy stocks, and households are more invested in the stock market than they have been in at least 70 years (Figure 4). Historically, these patterns have signaled that a stock market downturn will occur within the next few years.

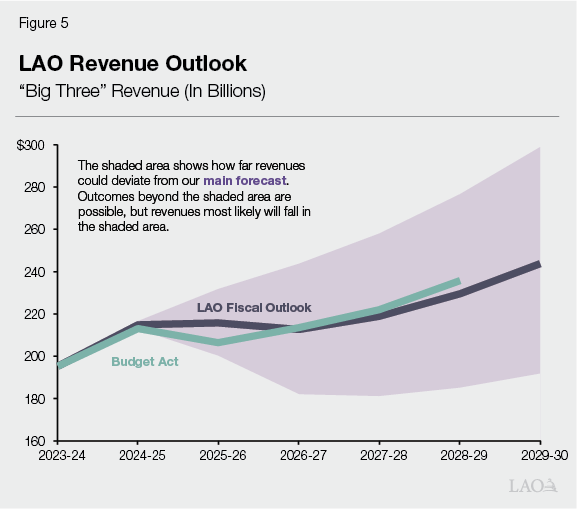

Forecast Assumes Recent Revenue Gains Are Temporary. The state’s strong income tax receipts over the past several months usually would imply an ongoing revenue increase. Our forecast, however, assumes these gains fade in 2026‑27. Specifically, our revenue estimate for 2026‑27 reflects an increase relative to the 2025‑26 enacted budget level, but a decrease relative to our revised 2025‑26 estimate (Figure 5). The decrease reflects the strong risk that the recent gains are tied to an unsustainable stock market. Our forecast does not specifically project a stock market downturn next year, but it gives this possibility much greater weight than previous outlooks. Moving forward, our forecast reflects modest revenue increases in 2027‑28 and 2028‑29 and average growth in 2029‑30. (The 2026‑27 Budget: California’s Fiscal Outlook provides additional context for our revenue assumptions.)

Proposition 98 Guarantee

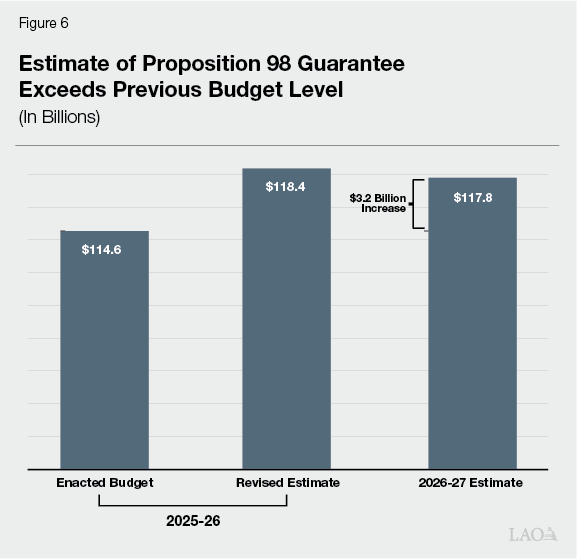

Guarantee Revised Up From the Previous Budget Level. Under our forecast, the minimum guarantee grows to $117.8 billion in 2026‑27, an increase of $3.2 billion (2.8 percent) from the previously enacted budget level (Figure 6). Test 1 is operative, with growth in General Fund revenue and local property tax revenue each contributing about equally to the increase. The 2026‑27 guarantee is less than our revised estimate of the 2025‑26 guarantee, however. This difference mirrors our forecast that state revenues in 2026‑27 are up relative to the previously enacted budget level but down slightly from our revised 2025‑26 estimate. Regarding local property tax revenue, we project a 4.8 percent increase in 2026‑27, which is below the long‑term average of about 6 percent. This slower growth is related to declining home sales and a slowdown in home price growth over the past few years.

Guarantee Is Moderately Sensitive to Revenue Changes in 2026‑27. General Fund revenue is typically the most significant input for calculating the guarantee. For any given year, the relationship between the guarantee and General Fund revenue generally depends on which Proposition 98 test is operative and whether another test could become operative with higher or lower revenue. In 2026‑27, Test 1 is likely to remain operative even if General Fund revenue or other inputs vary significantly from our forecast. In Test 1 years, the guarantee changes by about 40 cents for each $1 of higher or lower General Fund revenue. (The state also is unlikely to pay any maintenance factor unless revenue growth from 2025‑26 to 2026‑27 is substantially higher than our forecast estimates.)

Average Growth in the Guarantee After 2026‑27. Figure 7 shows the guarantee under our forecast over the next four years. The increases in 2027‑28 and 2028‑29 are just below the long‑term average of 5.4 percent. In 2029‑30, growth would accelerate to 7.5 percent under our assumptions, driven by faster revenue growth and a required maintenance factor payment. This payment would eliminate virtually all of the remaining maintenance factor obligation. Test 1 remains operative over the period, with increases in General Fund revenue and local property tax revenue each contributing to growth in the guarantee. The increases in the General Fund portion of the guarantee closely track our General Fund revenue estimates. Regarding local property tax revenue, we expect that improvements in the housing market will result in annual growth that approaches the historical average (about 6 percent) from 2027‑28 through 2029‑30.

Figure 7

Proposition 98 Outlook

(Dollars in Millions)

|

2025‑26 |

2026‑27 |

2027‑28 |

2028‑29 |

2029‑30 |

|

|

Minimum Guarantee |

|||||

|

General Fund |

$84,326 |

$82,130 |

$85,785 |

$90,183 |

$97,689 |

|

Local property tax |

34,029 |

35,671 |

37,849 |

39,968 |

42,257 |

|

Totals |

$118,355 |

$117,800 |

$123,634 |

$130,151 |

$139,946 |

|

Change From Prior Year |

|||||

|

General Fund |

‑$5,194 |

‑$2,196 |

$3,655 |

$4,399 |

$7,506 |

|

Percent change |

‑5.8% |

‑2.6% |

4.5% |

5.1% |

8.3% |

|

Local property tax |

$1,448 |

$1,642 |

$2,178 |

$2,119 |

$2,289 |

|

Percent change |

4.4% |

4.8% |

6.1% |

5.6% |

5.7% |

|

Total guarantee |

‑$3,746 |

‑$554 |

$5,833 |

$6,517 |

$9,795 |

|

Percent change |

‑3.1% |

‑0.5% |

5.0% |

5.3% |

7.5% |

|

General Fund Tax Revenuea |

$213,705 |

$208,298 |

$217,562 |

$228,278 |

$242,912 |

|

Growth Rates |

|||||

|

K‑12 average daily attendance |

0.9% |

‑1.0%b |

‑0.7%b |

‑1.0% |

‑1.1% |

|

Per capita personal income (Test 2) |

6.4 |

4.2 |

4.8 |

4.6 |

4.7 |

|

Per capita General Fund (Test 3)c |

1.1 |

‑2.3 |

4.8 |

5.3 |

6.7 |

|

Maintenance Factor |

|||||

|

Amount created/paid (+/‑) |

— |

— |

— |

‑$171 |

‑$1,907 |

|

Amount outstandingd |

$1,796 |

$1,871 |

$1,960 |

1,860 |

18 |

|

Proposition 98 Reserve |

|||||

|

Deposit (+) or withdrawal (‑) |

‑$270 |

‑$1,112 |

— |

$1,863 |

$3,376 |

|

Cumulative balance |

1,112 |

— |

— |

1,863 |

5,239 |

|

Operative Test |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

|

aExcludes non‑tax revenues and transfers, which do not affect the calculation of the minimum guarantee. bThis decline is deemed to be zero for the purpose of calculating the guarantee. As set forth in the State Constitution, an attendance decline does not reduce the guarantee unless attendance has declined in the two previous years. cAs set forth in the State Constitution, reflects change in per capita General Fund plus 0.5 percent. dIncludes adjustments to the previous year’s maintenance factor for growth in per capita personal income and K‑12 attendance as required by the State Constitution. |

|||||

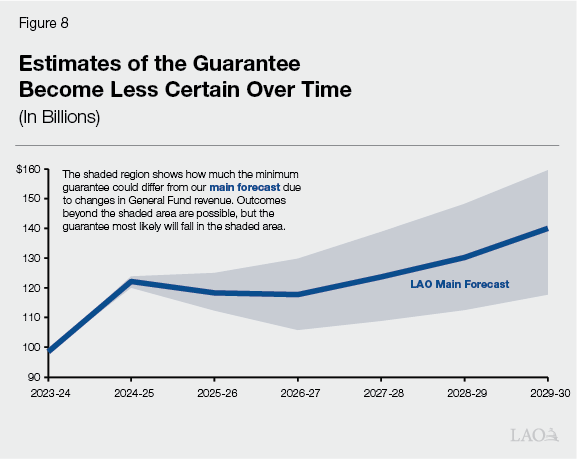

Estimates of the Guarantee Become Less Certain Over Time. Our forecast reflects the revenue estimates we consider most likely, but many other revenue scenarios are possible. Revenues can also fluctuate notably from year to year, even if they track our forecast over a longer period. Figure 8 shows how much the minimum guarantee could differ from our projections based on variations in General Fund revenue. For this analysis, we examined the historical relationship between previous revenue estimates and actual tax collections, then calculated the guarantee under the different revenue scenarios. The uncertainty in our estimates increases significantly over time. For example, the likely range for the guarantee in 2029‑30 is nearly twice the range in 2026‑27.

Program Costs

Moderate COLA Projected for 2026‑27. We estimate the statutory COLA for 2026‑27 will be 2.51 percent, but our estimate carries more uncertainty than usual. Our November forecast typically incorporates published data for six of the eight quarters affecting the calculation (and our projections for the remaining quarters). This year, the sixth quarter was unavailable due to the lapse in appropriations for the federal agency providing the data (the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis). As of this writing, the agency has reopened but not yet determined when the data will be available. Assuming the COLA rate remains at 2.51 percent, the associated cost would be $2.5 billion.

Somewhat Higher COLA Rates Projected After 2026‑27. Under our forecast, the COLA rate would increase after 2026‑27. Specifically, our estimate of the statutory rate is 3.7 percent in 2027‑28, 4 percent in 2027‑28, and 4.2 percent in 2029‑30. These estimates are above the historical average of about 3 percent per year. The cost of covering the COLA in these years would be $3.9 billion, $4.3 billion, and $4.7 billion, respectively. These projections should be interpreted with caution, as the final rates often differ significantly from the initial estimates.

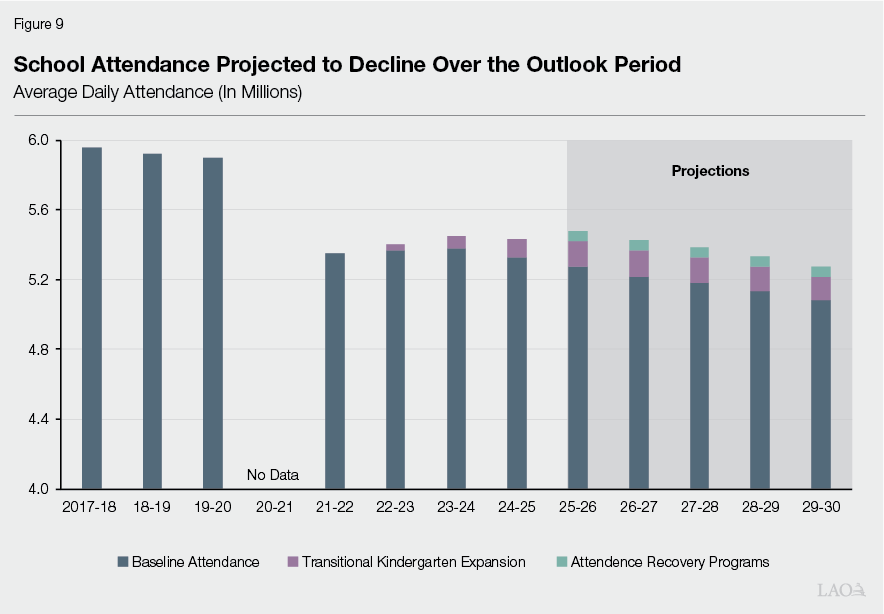

School Attendance Projected to Increase in 2025‑26, Then Decline. We estimate that school attendance will increase by 0.9 percent in 2025‑26. Two main factors explain the increase. First, districts can begin implementing attendance recovery programs—a recent measure that allows districts more flexibility to offset student absences by providing instruction outside the regular school day. We expect these programs to increase attendance on an ongoing basis. Second, universal transitional kindergarten will be fully implemented in 2025‑26. (The state began expanding this program four years ago.) On the other hand, the state’s school‑age population is declining due to a decrease in births that began nearly two decades ago and accelerated between 2017 and 2020. This decline is likely to be the main factor affecting school attendance over the next several years, and we estimate corresponding attendance decreases of about 1 percent per year (Figure 9). We expect the decline to yield only minor cost savings in 2026‑27 because the state funds LCFF based on each district’s attendance in the current year, the previous year, or the average of the three previous years (whichever is highest). As the decline continues, these savings will grow.

Community College Enrollment Projected to Continue Increasing. For 2025‑26, our projections are based on the enrollment assumptions from the adopted budget. For 2026‑27, we estimate a 2.9 percent increase in funded full‑time equivalent students, reflecting the net effect of enrollment growth and other enrollment adjustments. Community college enrollment has increased in recent years, likely due to several factors including regional demographic growth, rising unemployment, and the expansion of high school dual enrollment. We expect enrollment will continue to increase at a similar rate in 2026‑27, then grow more slowly afterward. Although our outlook treats the cost of enrollment changes as a baseline adjustment, the Legislature has discretion over how much growth to fund each year.

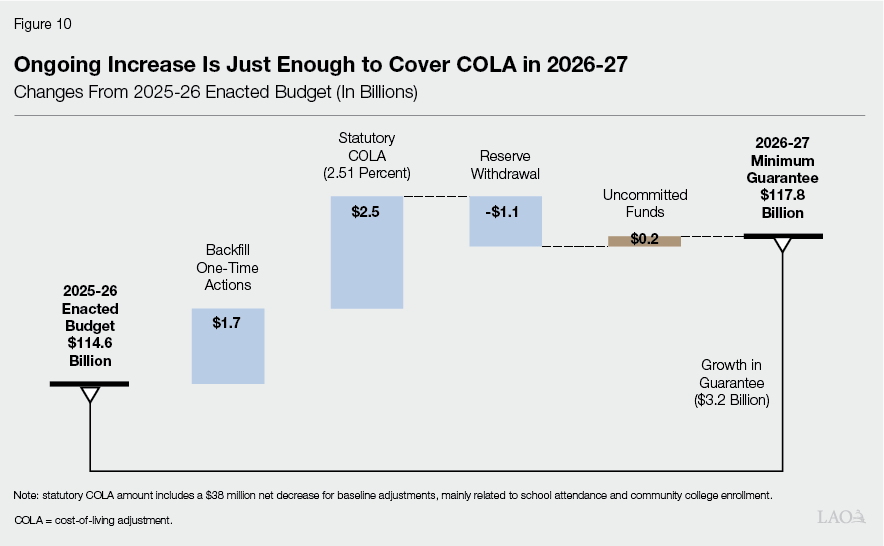

June Budget Covered Ongoing Program Costs With One‑Time Funds. The 2025‑26 adopted budget used $1.7 billion in one‑time funds to pay for ongoing school and community college programs. Most of these one‑time funds came from (1) increases in the Proposition 98 guarantee in previous years and (2) savings related to deferring payments. Entering 2026‑27, these one‑time funds will expire, leaving a $1.7 billion gap between the cost of ongoing programs and the funding set aside to pay for them. The state will have to allocate some of the increase in the Proposition 98 guarantee to cover this shortfall in the upcoming budget.

Proposition 98 Reserve

Reserve Withdrawal Required in 2026‑27. The Proposition 98 Reserve generally requires withdrawals when the guarantee is less than the previous year’s guarantee, adjusted for inflation. For 2026‑27, we estimate the guarantee is $5.5 billion below this threshold. This relatively large gap has several implications. First, the state is required to withdraw the entire balance from the reserve in 2026‑27 ($1.1 billion). Second, the state would be unlikely to retain any funding in the reserve even if it makes larger deposits in 2024‑25 or 2025‑26. Under our forecast, additional required deposits in those years would have to be withdrawn in 2026‑27. Finally, the withdrawal is not especially sensitive to changes in revenue. Specifically, General Fund revenues would have to exceed our estimate by roughly $14 billion in 2026‑27 before the formulas would cancel the withdrawal. (This threshold holds all other inputs constant.)

Deposits and Withdrawals After 2026‑27 Are Sensitive to Revenue Estimates. For 2027‑28, no deposit would be required under our forecast because the guarantee is growing more slowly than inflation. As growth in the guarantee accelerates, the state would be required to make deposits in 2028‑29 and 2029‑30 totaling $5.2 billion. These deposits are sensitive to changes in revenue. For example, if revenues grow 1 percent faster than our forecast assumes in 2027‑28, the state would start making deposits that year.

Key Considerations

Funding Estimates for 2026‑27 and Beyond

State Would Have Just Enough Funding to Cover COLA. Figure 10 shows our estimate of the funding available for new commitments in 2026‑27. It begins with the spending level the state approved in the 2025‑26 budget, then adjusts for the expiration of one‑time savings and the cost of covering COLA. These adjustments alone would increase spending above the guarantee, but the state could cover these costs through the required reserve withdrawal. After accounting for all adjustments, $220 million in Proposition 98 funding would remain available. The state could use this funding for any school or community college purposes.

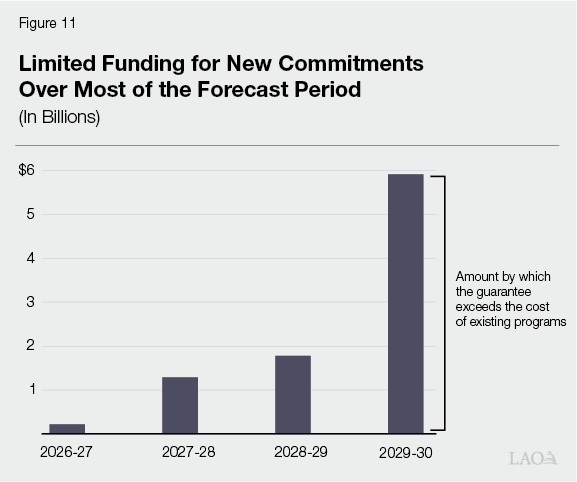

Funding for New Commitments Remains Limited Until Revenue Accelerates. Figure 11 illustrates how the funding available for new commitments could change over the outlook period. Specifically, it shows the difference between the Proposition 98 guarantee and the costs of existing programs (adjusted for the statutory COLA and enrollment‑related changes). The positive bars indicate the guarantee could cover existing programs with funds left over for new commitments—similar to a surplus. This surplus remains small over the next few years, but increases in the final year when the guarantee grows more rapidly. This pattern shows how the available funding depends on state revenues. If revenues grow more slowly than our forecast assumes for the next few years, however, the guarantee likely could not even support existing programs.

Planning for the Upcoming Budget

Several Considerations for One‑Time Funds. The $7.4 billion in one‑time funds is large by historical standards. Specifically, it exceeds the one‑time funding we have projected in all previous outlooks, except for November 2020 ($13.7 billion) and November 2021 ($10.2 billion). This funding offers the Legislature a significant opportunity to advance its priorities. During budget deliberations, the Legislature will likely want to consider (1) how much to allocate for budget resiliency versus new one‑time programs, (2) whether additional one‑time funding could complement any existing initiatives or programs, and (3) how these funds could improve student outcomes or local budgets beyond the upcoming year.

State Is Not Well Positioned for New Ongoing Commitments. Whereas our forecast projects substantial one‑time funding, it also suggests the state has little capacity to sustain additional ongoing commitments. Most notably, it indicates that the guarantee in 2026‑27 would be unable to cover the COLA without a reserve withdrawal. A decline in revenues or a higher COLA rate could make the COLA unaffordable. Our forecast shows the guarantee increasing slightly faster than the inflation‑adjusted cost of existing programs in 2027‑28, but the margin is small. If the state were to commit to significant new ongoing spending, it could find the increase hard to sustain over the next few years.

Options for Building Budget Resiliency

Compared With Previous Years, the State Has Fewer Tools to Address Funding Declines. When the state faced significant revenue drops in 2022‑23 and 2023‑24, it used several tools to sustain ongoing school and community college programs. Most notably, it withdrew $9.5 billion from the Proposition 98 Reserve. The state also had a $3.5 billion “cushion” because it did not spend all of the previous increases in the guarantee on ongoing programs. In contrast, our forecast suggests the state will end 2026‑27 with no funding in the reserve and no ongoing cushion. It also enters the upcoming year having already deferred $2.3 billion in school and community college payments. These aspects of the budget—and the state’s dependence on the stock market—make the upcoming year especially precarious. A decline in the value of the tech companies leading the stock market could rapidly reduce state revenues and the Proposition 98 guarantee. In the rest of this section, we provide some options to build budget resiliency and help protect ongoing school and community college programs.

Consider Eliminating Payment Deferrals ($2.3 Billion). School districts and community colleges ordinarily receive their funding in 12 monthly installments. The June budget deferred the last payment to schools and the last two payments to community colleges to obtain one‑time savings. As a starting point for building resilience, the Legislature could use $2.3 billion in one‑time funding to eliminate these deferrals and restore the regular payment schedule. This approach would remove pressure on future Proposition 98 budgets, giving the Legislature more options during the next economic downturn.

Consider Providing Districts an Advance Payment ($1.9 Billion). After eliminating the deferrals, the Legislature could further improve budget resiliency with a new fiscal tool: giving districts a 13th payment at the end of 2026‑27 that would count toward their LCFF and SCFF allocations in 2027‑28. Moving forward, districts would receive this same amount a month earlier than usual each year. During the next economic downturn, the state could obtain savings by reverting to the regular payment schedule. The advance payment would function like the opposite of a traditional payment deferral. Whereas a deferral provides up‑front state savings but creates future costs and weakens district cash flow, the advance payment is an up‑front state cost that allows future savings and improves district cash flow. The fiscal benefit for school and community college programs would be similar to having a larger balance in the Proposition 98 Reserve—without the risk of facing premature reserve withdrawals or activating the local reserve cap. The Legislature could consider any amount for this purpose, but one option is to use the $1.9 billion settle‑up payment the state owes from the June 2025 budget. This approach is consistent with legislative intent for this payment because it would reduce the likelihood of future deferrals. (The advance payment would require districts to update their cash flow projections, but it would not affect the Proposition 98 guarantee.)

Consider Early Restoration of Learning Recovery Emergency Block Grant ($757 Million). The state created this grant in the 2022‑23 budget to mitigate the learning loss and social disruption students experienced during the pandemic. The initial allocation was $7.9 billion, but the state later reduced the grant by $1.1 billion to address a drop in the guarantee. The June 2025 budget provided $379 million as the first installment in a three‑year plan to restore the original amount. Continuing with this plan would require another $379 million in the upcoming budget, but the Legislature could instead provide $757 million to restore the full amount a year early. This approach would reduce costs in 2027‑28, when the state will likely have less one‑time funding available. It could also accelerate the learning recovery efforts supported by the grant.

The School and Community College Split

Sharp Differences Between Schools and Community Colleges Based on the “Split.” Throughout this report, we have estimated the funding available each year by comparing the Proposition 98 guarantee to the total cost of all school and community college programs. The state, however, typically budgets by allocating about 89 percent of the guarantee to schools and about 11 percent to community colleges. These percentages are colloquially known as the split. The state has an uncodified list of programs that it excludes from this calculation. (The state subtracts the cost of these programs from the guarantee before applying the percentages to the remaining amount.) If the state allocates funding in 2026‑27 using the split and the same exclusions as the June 2025 budget, the fiscal outcomes for schools and community colleges would differ significantly. Specifically, the state would need to spend $721 million more on school programs and $501 million less on community college programs compared with the amounts required to maintain existing programs and cover the COLA. (These amounts add up to the $220 million in available funding we identified earlier.) As a point of comparison for the community colleges, $501 million exceeds our projected cost for COLA and all enrollment‑related increases in the SCFF in 2026‑27.

Differences in Split Calculation Related to Three Factors. The most significant factor explaining the gap between schools and community colleges is enrollment. We estimate that enrollment‑related adjustments will increase community college costs by more than $200 million in 2026‑27, reducing the funding available for other activities. School attendance, by contrast, is expected to decline in 2026‑27. Another significant factor involves a recent change to the split methodology related to transitional kindergarten. For 2026‑27, the new method provides about $200 million less for community colleges than the previous method. The third factor concerns the program cost estimates in the adopted budget. Our estimate of SCFF costs for 2025‑26 is tracking about $90 million higher than the June estimate, and this higher spending level continues into 2026‑27. School district costs, by contrast, are tracking slightly below the June estimates. Without these three factors, the split calculation would have produced similar outcomes for schools and community colleges in 2026‑27 (meaning each segment would have received a roughly proportional share of the available funding).

Legislature Can Build a Budget Aligned With Its Priorities. The California Constitution gives the Legislature broad discretion over the allocation of Proposition 98 funding. Most notably, the Legislature decides how to distribute funding between schools and community colleges, chooses which spending proposals to fund, and determines the portion of the guarantee to allocate to activities that build budget resiliency. Regarding the split, the Legislature could use the previous year’s methodology, further modify it, or adopt another allocation mechanism altogether.