LAO Contact

Ann Hollingshead

For detail about specific budget areas, see the California Spending Plan Series.

October 16, 2025

The 2025-26 Budget

Overview of the Spending Plan

- Introduction

- The Budget Problem

- Budget Condition

- Evolution of the Budget

- Major Features of the 2025‑26 Spending Plan

- K‑14 Education

- Health

- Higher Education

- California Environmental Quality Act

- Recent Voter‑Approved Bond Allocations

- Cap‑and‑Invest Program Spending

- Appendices

Introduction

Each year, our office publishes the California Spending Plan to summarize the annual state budget. In this publication we: provide an overview of the 2025‑26 budget package, give a brief description of how the budget process unfolded, and then highlight the major features of the budget approved by the Legislature and signed by the Governor. All figures in this publication reflect the administration’s estimates of actions taken through early July 2025, however, we have updated the text to reflect actions taken later in the legislative session. In addition to this report, we will release a series of issue‑specific, online posts that give more detail on the major actions in the budget package.

The Budget Problem

For the third year in a row, the state faced a budget problem, or deficit. Although the budget problem this year was smaller than in recent years ($15 billion this year compared to $55 billion in 2024‑25 and $27 billion in 2023‑24), addressing this year’s budget problem required the state to adopt more ongoing solutions. In this section, we first present our estimates of the budget problem the Legislature addressed in the 2025‑26 budget package, focusing on the three‑year budget window under consideration: 2023‑24 through 2025‑26. Second, we briefly summarize the key actions taken to address projected out‑year deficits, and describe the administration’s June 2025 estimates of the state’s multiyear budget condition under the enacted spending plan.

What Is a Budget Problem? A budget problem—also called a deficit—arises when resources for the upcoming budget are insufficient to cover the costs of currently authorized services. A budget problem is inherently a point‑in‑time estimate that reflects information available at the time of development, forecasts of future revenues and spending, and assumptions about which cost changes reflect current law and policy (referred to as “baseline changes”). When cost changes do not occur automatically under current policy, we classify them as either budget solutions or discretionary augmentations.

Budget Package Addressed a Nearly $15 Billion Budget Problem. We estimate the Legislature addressed a nearly $15 billion budget problem in the 2025‑26 budget package. This budget problem is slightly higher than the one addressed by the Governor in the May Revision (around $14 billion), and results from two somewhat offsetting differences. First, compared to the May Revision, the final budget package assumed higher revenues in major taxes by $1.1 billion, reflecting cash receipts to date, which have come in slightly higher than the administration’s May estimates. (This improves the budget condition.) Second, these higher revenues are more than offset by more discretionary spending, which totals $4 billion in the final package, compared to $1.6 billion in the May Revision. (The difference between these two—over $2 billion—increases the budget problem.)

Actions Taken Last Year Reduce the Budget Problem. In June 2024, the Legislature not only addressed the budget problem for 2024‑25 but also proactively adopted solutions intended to reduce the anticipated shortfall in 2025‑26. At the time, the June 2024 budget package included $28 billion in budget solutions for 2025‑26, although savings from some of these actions have since diminished. Importantly, these budget solutions also included a planned withdrawal from the state’s rainy‑day fund, the Budget Stabilization Account (BSA), of $7.1 billion. The June 2025 spending plan maintains these actions, including the reserve withdrawal. We provided further detail and updated estimates of these solutions in our January report, The 2025‑26 Budget: Overview of the Governor’s Budget (see Appendix 1). These early decisions substantially reduced the size of the budget problem the Legislature faced this year.

New Discretionary Spending Increases the Size of the Budget Problem. Most of the reason that the state faces a budget problem is that the underlying costs of state services continue to outpace the state’s revenue collections. However, about $4 billion of the budget problem results from new, discretionary General Fund spending in the budget package, as well as some budget actions adopted in a special session, which we describe in the box below. (We define discretionary spending as new spending or revenue reductions that were not previously authorized under current law or legislative policy.) Total discretionary General Fund spending (excluding Proposition 98) in the 2025‑26 budget package are listed in Appendix 1.

Special Session Had Notable Budgetary Implications

This year, the Governor called a special session of the Legislature that had notable budgetary implications. (The special session was initially called in November 2024, and then subsequently amended in January 2025.) The measures approved in the special session provided funding for (1) response and recovery costs related to the January 2025 Southern California wildfires and (2) activities to address federal government actions impacting the state. Below, we provide a high‑level summary of these measures.

Funding for the January 2025 Southern California Wildfires. During the special session, the Legislature added Control Sections 90.00 and 90.01 to the 2024‑25 Budget Act providing up to $2.5 billion one‑time for response and recovery costs related to the January 2025 Southern California wildfires. Specifically, the control sections authorized the Department of Finance (DOF), through June 2025, to augment both General Fund and special fund appropriations for state agencies to support activities such as emergency protective measures, sheltering for survivors, assessment and remediation of post‑fire hazards, and other actions necessary to protect persons or property and expedite recovery. The control sections required DOF to publish expenditure reports documenting the use of the funds. As of June 30, 2025, $335.9 million exclusively from the General Fund had been allocated through the control sections by DOF for these purposes. After the special session, the sections were amended to allow funds to be used to reimburse local governments through June 2026 for (1) unmet response and recovery costs, and (2) lost property tax revenue. DOF has not yet received official claims from all affected local governments, but early estimates indicate expenditures for these purposes could be around $200 million across the 2024‑25 and 2025‑26 budget years. (Modified versions of Control Sections 90.00 and 90.01 were also added to the 2025‑26 Budget Act, extending the availability of these funds. For more on this please see our forthcoming publication, The 2025‑26 California Spending Plan: Other Provisions.)

Addressing Federal Actions Impacting the State. During the special session, the Legislature amended existing Control Section 5.25 and also added Control Section 5.26 to the 2024‑25 Budget Act, providing a total of up to $50 million one‑time General Fund for legal and administrative activities that address federal actions impacting the state. Specifically, up to $25 million was made available through June 2028 for legal activities to allow the Department of Justice (DOJ) and other state departments to defend the state against federal actions or to challenge federal actions more generally. These funds are also available to allow state departments to take administrative steps to mitigate the impacts of federal actions. DOJ is required to report regularly on how these funds are used. The remaining $25 million was made available through June 2028 for grants to legal service providers as follows:

- $10 million to the judicial branch for indigent civil legal services for individuals likely to be impacted by potential or actual federal actions.

- $10 million to the Department of Social Services (DSS) for immigration‑related legal services.

- $5 million to the judicial branch to supplement its existing contract with the California Access to Justice Commission for legal services nonprofits generally.

The judicial branch and DSS are required to report to the Legislature on grant awardees. (Details on similar ongoing funding included as part of the 2025‑26 budget is discussed in our forthcoming publication The 2025‑26 California Spending Plan: Judiciary and Criminal Justice.)

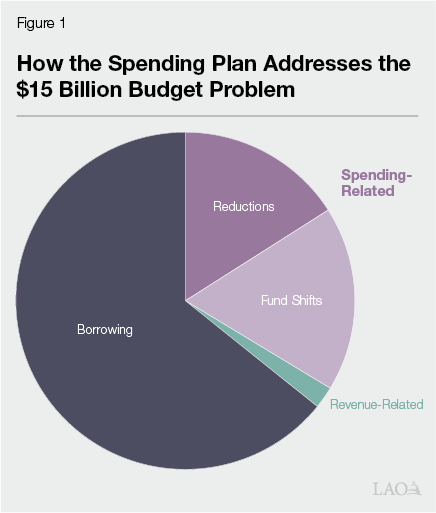

How the Spending Plan Addresses the Budget Problem

The state has several types of solutions—or options—for addressing a budget problem, but the most important include: reserve withdrawals, spending reductions, revenue increases, and borrowing (for example, loaning money from other funds to the General Fund). Figure 1 summarizes the solutions that the budget package used to address the $15 billion budget problem. As the figure shows, the budget primarily relies on borrowing to close the gap, representing about two‑thirds of the total solutions. (We describe our use of this term in more detail below.) After borrowing, spending‑related solutions, including both reductions and fund shifts, total $5 billion and represent nearly all of the remaining one‑third of the total solutions. (Revenue‑related solutions, totaling about $300 million, represent the small remainder.) Note that while the state is also making a $7.1 billion withdrawal from the BSA in 2025‑26, this withdrawal is not reflected in Figure 1 because it was authorized in the 2024‑25 budget package. The remainder of this section provides additional detail on each category of solution. Appendix 2 lists all the budget solutions.

Borrowing ($10 Billion)

The budget package primarily addresses the budget problem using borrowing—these solutions represent $10 billion or roughly two‑thirds of the total solutions. We define “borrowing” as budget actions that achieve savings in the present, but result in an obligation or higher cost for the state in a future year. (Until recently, we had used the term “cost shift” [instead of borrowing] to describe these types of actions because they are not always explicitly structured as loans or similar instruments. However, we have found the term cost shift is unclear for many readers and, as a result, can obscure the fiscal implications of these actions. Accordingly, we have adopted terminology that more transparently reflects the underlying nature of these budget solutions, if not always their precise mechanics.)

Major categories of borrowing in the budget include:

- Medi‑Cal Maneuver ($4.4 Billion). Under state law, the administration can transfer funds to the Medical Provider Interim Payment (MPIP) Fund to help cover an appropriation deficiency in Medi‑Cal. These transfers are capped as a percent of Medi‑Cal’s appropriation. On March 12, the administration notified the Joint Legislative Budget Committee it had transferred $3.4 billion General Fund (around the maximum allowed) to the MPIP Fund to cover unanticipated cost increases in Medi‑Cal. While this payment has been made on a cash basis, the May Revision proposes that the state not recognize it in the budget this year (instead, it would be recognized over multiple years and fully reflected by 2034). This maneuver essentially creates a loan from the state’s cash resources, and a future obligation that is repaid when the state recognizes the payment that was already made. The final budget reflects a Medi‑Cal maneuver of $4.4 billion.

- Special Fund Loans ($2.1 Billion). The spending plan includes loans from special funds, which compared to other actions in this section, are a more traditional form of borrowing used to help balance the budget. These loans are made on a budgetary basis from borrowable special funds with unspent balances. The spending plan includes two types of these loans: $550 million in loans allocated to specific funds ($150 million from the Unfair Competition Law Fund and $400 million from the Labor and Workforce Development Fund) and $1.5 billion in unallocated special fund loans, authorized through Control Section 13.40. Through that control section language, the Department of Finance (DOF) is authorized to collectively transfer $1.5 billion from various special funds to the General Fund during the 2025‑26 year. As of this writing, DOF is still working on identifying the list of those funds to borrow from to achieve this target.

- Proposition 98 “Settle Up” ($1.9 Billion). Proposition 98 (1988) sets a minimum funding requirement for schools and community colleges based on formulas in the State Constitution. The state makes an initial estimate of this requirement when it enacts the budget, then revises this estimate over the following two years to reflect updated data. The estimate of the requirement for 2024‑25 is up nearly $4.7 billion (4 percent) from the June 2024 level, but the budget appropriates just over $2.7 billion in additional funding for that year. Funding schools and community colleges at this level—$1.9 billion below the estimate of minimum requirement—provides temporary savings but requires the state to settle up using future revenues. The state will finalize its calculation of this obligation in May 2026. (In January and May, we had categorized settle up as a spending delay, but upon further deliberation, we view this action as borrowing.)

- Middle Class Scholarships (MCS) Arrears Budgeting ($1 Billion). The budget package reflects $1 billion in savings by deferring recognition of MCS program costs from 2025‑26 to 2026‑27 on a budgetary basis. However, on a cash basis, these costs would still be paid in 2025‑26 as they are incurred. Like other budget maneuvers, this creates a misalignment between the state’s cash position and its budgetary costs. Notably, this cost shift is intended to continue on an ongoing basis—meaning costs incurred in 2026‑27 would be recognized in 2027‑28, and so on. Undoing this maneuver in the future will require the state to pay for two years’ worth of program costs in a single fiscal year.

- University Payment Deferrals ($274 Million). The budget defers University of California (UC) and California State University (CSU) payments that otherwise would have been made in May to June or July. By shifting payments to the next fiscal year, these deferrals create one‑time savings in 2025‑26. Similar to other forms of borrowing, undoing these deferrals in the future (and reverting payments to their typical schedule) will require the state to provide one‑time back payments to the universities.

Balance of the State’s Outstanding Budgetary Borrowing Has Increased. The actions described in this section increase the amount of outstanding borrowing the state has used to address its budget problems. (This borrowing is similar to the measures used during the Great Recession—collectively previously referred to as the state’s “wall of debt”—and create obligations that should be repaid or reversed in the future.) While the state has various financial and accounting reports that allow policy makers and observers to track a variety of the state’s outstanding liabilities, the administration does not produce an easily accessible, public list of the state’s outstanding budgetary borrowing incurred to address recent deficits. We have provided this list in Figure 2. As shown in Figure 2, the 2025‑26 spending plan includes nearly $10 billion in new borrowing, increasing total outstanding budgetary borrowing from $12 billion to $22 billion.

Figure 2

The State’s New Wall of Debt

(In Billions)

|

Borrowing type |

Amount |

|

Existing |

|

|

Payroll deferral |

$1.6 |

|

Proposition 98 maneuver (cash borrowing) |

6.4 |

|

Special fund loans |

4.0 |

|

Total |

$12.0 |

|

Adopted in 2025‑26 Budget Package |

|

|

Medi‑Cal maneuver (cash borrowing) |

$4.4 |

|

Settle up |

1.9 |

|

Special fund loans (unallocated) |

1.5 |

|

Middle Class Scholarships arrears budgeting |

0.9 |

|

Special fund loans (allocated) |

0.6 |

|

University payment deferrals |

0.3 |

|

Total |

$9.6 |

|

Total Outstanding Budgetary Borrowing |

$21.6 |

Spending‑Related Solutions ($5 Billion)

Reductions ($2.5 Billion). Under our definition, a spending reduction occurs when the state reduces spending relative to what was established under current law or policy. More colloquially, these are spending cuts. We estimate the budget package includes about $2.5 billion in spending‑related reductions. Many spending reductions enacted as part of this year’s budget will increase over time, such that spending reductions grow to $10.5 billion ongoing by 2028‑29. For example, the budget package freezes enrollment in Medi‑Cal for the adult population with unsatisfactory immigration status (UIS)—an action that saves less than $100 million in the budget window, but increases to over $3 billion over time. The budget also includes unallocated operational improvements at the Department of Health Care Services, Department of Social Services, and Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation, which the administration assumes will eventually yield over $1 billion in ongoing savings. The budget package also reduces payments to clinics for services rendered to individuals with UIS by changing the payment methodology for this population—resulting in about $1 billion in savings ongoing.

Fund Shifts ($3 Billion). Fund shifts are budget solutions that use other fund sources—for example, special funds—to pay for a cost typically incurred by the General Fund. These shifts reduce expenditures from the General Fund as they simultaneously displace spending that these other funds otherwise would have supported. As a result, we consider these to be a type of spending‑related solution because they typically result in lower overall state spending, inclusive of all funds. We estimate the budget package includes nearly $3 billion in fund shifts. The largest categories include:

- $1 Billion for California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection (CalFire) Activities. The budget shifts $1 billion in costs for CalFire’s operational expenses from the General Fund to the Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund (GGRF, which is funded with auction revenues from the state’s cap‑and‑trade program) in 2025‑26. The budget agreement expresses intent to continue such a shift in the coming years to provide additional General Fund relief but in differing amounts, depending upon the budget condition. Specifically, if the General Fund continues to experience deficits, the plan intends that GGRF would cover $1.25 billion of CalFire’s costs in 2026‑27, $500 million in 2027‑28, and $500 million in 2028‑29. If the General Fund is not projected to be in a deficit in 2026‑27, GGRF would only cover $500 million for CalFire in that year.

- About $300 Million for Various Environmental Activities. The budget package reduces about $300 million in planned General Fund support for nine categories of environmental activities—including dam safety, offshore wind development, and wildfire resilience projects at State Parks—and then provides at least as much funding for similar activities from Proposition 4, the climate bond authorized by voters in November 2024. (In some cases, the bond‑supported programs—and, therefore, projects that ultimately will end up being funded—may differ slightly from those that might have been funded with the General Fund. However, the general categories overlap and were selected and proposed by the Governor as fund shifts.)

Reversions ($70 Million). Costs for state programs sometimes come in lower than the amount that was appropriated. This often occurs, for example, when the state overestimates uptake in a new program or as a routine matter in programs where spending is uncertain due to factors like caseload. When actual state costs are below budgeted amounts, a reversion occurs after a period of time—typically, three years. The reversion returns the unspent funds to the General Fund. This year’s budget package accelerates some reversions that would have otherwise occurred in the future and proactively reverts certain funds that otherwise are continuously appropriated (which has the effect of realizing savings from the unspent funds that would not otherwise occur). While not all of these amounts represent lower state spending over the long term, they do result in savings today at a cost of forgone savings in the future. As a result, we count them as spending‑related solutions. The budget package includes less than $100 million in reversions.

Revenue‑Related Solutions ($300 Million)

Change in Tax Rules for Financial Institutions. The spending plan changes the rules about how taxable profits are determined for multistate financial institutions. This change is assumed to increase revenues by $330 million in 2025‑26 and $250 million per year thereafter.

Multiyear Budget Problem

The budget package has taken steps to partially address the state’s persistent multiyear deficits. We describe those actions at a high level in this section, and then provide an overview of the administration’s estimates of the out‑year condition of the budget after accounting for these ongoing solutions.

Ongoing Budget Solutions Total $11 Billion. The spending plan includes roughly $11 billion in ongoing budget solutions, including $10.5 billion in ongoing spending solutions, and $300 million in ongoing revenue increases. Nearly all of these spending solutions are reductions. The reductions are largely concentrated in the health area, with ongoing solutions in Medi‑Cal—the state’s Medicaid program—reflecting about two‑thirds of the total. (We describe the health‑related budget solutions in more detail below.) In addition to the ongoing solutions, the budget includes $20 million for DOF to contract with consultants to assist and advise DOF on analyzing and creating process improvements within state government. The overall aim of this effort is to find other areas of ongoing savings for future legislative action.

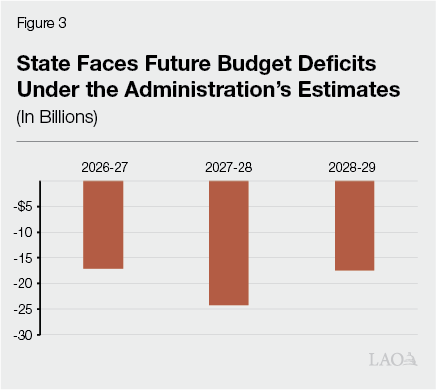

Multiyear Deficits Persist Under Administration’s Estimates. Based on the administration’s June 2025 projections and assumptions, budget deficits are expected to persist despite the ongoing solutions included in the 2025‑26 spending plan. Specifically, the administration projects annual operating deficits ranging from roughly $15 billion to $25 billion throughout the outlook period (see Figure 3). These projected shortfalls represent future budget challenges the Legislature would need to address. However, multiyear estimates—particularly revenue projections—are subject to considerable uncertainty. Revenue estimates can vary by billions of dollars in the near term and by tens of billions of dollars in later years. As such, these estimates should be interpreted cautiously, as shortfalls of these magnitudes are far from guaranteed.

Budget Condition

In this section, we describe the overall condition of the General Fund budget, the condition of the school and community college budget, and state appropriations limit (SAL) estimates under the spending plan. As is the case in the previous section, all of the figures here use the administration’s budget estimates as of June 2024.

General Fund

Figure 4 summarizes the condition of the General Fund under the revenue and spending assumptions in the June 2025 budget package, as estimated by the administration. Under these projections, the state ends 2025‑26 with $4.5 billion in the Special Fund for Economic Uncertainties (SFEU). (The SFEU is the state’s operating reserve and essentially functions like an end‑of‑year balance.)

Figure 4

General Fund Condition Summary

(In Millions)

|

2023‑24 |

2024‑25 |

2025‑26 |

|

|

Prior‑year fund balance |

$51,769 |

$41,977 |

$35,145 |

|

Revenues and transfers |

195,879 |

226,745 |

215,733 |

|

Expenditures |

205,670 |

233,577 |

228,366 |

|

Ending fund balance |

$41,977 |

$35,145 |

$22,513 |

|

Encumbrances |

$18,001 |

$18,001 |

$18,001 |

|

SFEU Balance |

$23,976 |

$17,144 |

$4,512 |

|

Reserves |

|||

|

BSA |

$23,194 |

$18,291 |

$11,191 |

|

SFEU |

23,976 |

17,144 |

4,512 |

|

Safety net |

900 |

— |

— |

|

Total Reserves |

$48,070 |

$35,435 |

$15,703 |

|

Note: Reflects administration estimates of budget actions taken through July 1, 2025. |

|||

|

SFEU = Special Fund for Economic Uncertainties and BSA = Budget Stabilization Account. |

|||

Reserves

General Fund Reserves Nearly $16 Billion Under Spending Plan. Although the state did not withdraw any funds from reserves to address the 2023‑24 budget problem, reserves have been used to address budget problems in 2024‑25 and 2025‑26. In particular, from the BSA, the state has used $5 billion in 2024‑25 and $7 billion in 2025‑26, bringing the balance to $11 billion remaining at the end of 2025‑26. The state already used the entire balance of the Safety Net Reserve—nearly $1 billion—in 2024‑25. Along with the planned balance of $4.5 billion in the SFEU, the state’s reserves total nearly $16 billion at the end of 2025‑26 under the spending plan. (The state reserve for schools and community colleges is also fully withdrawn by the end of 2025‑26.)

Revenues

Figure 5 displays the administration’s revenue projections as incorporated into the June 2025 budget package. As the figure shows, the administration expects revenues from the state’s three largest sources—the personal income tax, corporation tax (CT), and sales and use tax—to grow about 10 percent between 2023‑24 and 2024‑25. This primarily reflects strong stock market growth between June 2023 and June 2025. The spending plan anticipates negative growth in these three major sources from 2024‑25 to 2025‑26, primarily driven by the CT. In this case, the 15 percent decline is attributable to the expiration of a policy that temporarily increased CT receipts.

Figure 5

General Fund Revenue Estimates

(Dollars in Millions)

|

Revised |

Enacted |

Change From 2024‑25 |

|||

|

2023‑24 |

2024‑25 |

Amount |

Percent |

||

|

Personal income tax |

$115,166 |

$126,277 |

$125,962 |

‑$316 |

— |

|

Sales and use tax |

33,339 |

33,706 |

34,862 |

1,156 |

3% |

|

Corporation tax |

35,456 |

41,696 |

35,613 |

‑6,083 |

‑15 |

|

Totals, Major Revenue Sources |

$183,962 |

$201,679 |

$196,437 |

‑$5,243 |

‑3% |

|

Insurance tax |

$3,966 |

$4,177 |

$4,359 |

$182 |

4% |

|

Other revenues |

7,333 |

7,182 |

5,626 |

‑1,556 |

‑22 |

|

Transfers and loans |

618 |

13,707 |

9,312 |

‑4,395 |

‑32 |

|

Totals, Revenues and Transfers |

$195,879 |

$226,745 |

$215,733 |

‑$11,012 |

‑5% |

|

Note: Reflects administration estimates of budget actions taken through July 1, 2025. |

|||||

Figure 5 reflects several tax policy changes, including an expansion of the state’s film tax credit, a new partial tax exclusion for military retirement income, and additional state low‑income housing tax credits. In addition, “transfers and loans” in Figure 5 include transfers from the state’s rainy‑day fund, described elsewhere, as well as loans from the state’s special funds, which have been used to partially address the budget problem.

Spending

Figure 6 displays the administration’s June 2025 estimates of total state and federal spending in the 2025‑26 budget package. (The amounts displayed in the figure do not include some notable actions taken late in the summer legislative session, including appropriations of $3.3 billion from the Proposition 4 climate bond and $540 million from GGRF, which we discuss later in this post.) As the figure shows, the spending plan assumes total state spending of $317 billion in 2025‑26. This is lower than the 2024‑25 total by 5 percent. Declines in state spending this year are generally attributable to the state’s budget problem and actions taken to lower spending to address the budget problem. (The “Major Features” section of this report also describes some of the major discretionary spending choices and budget solutions reflected in the spending plan.) As of June 2024, federal funds are expected to be flat between 2024‑25 and 2025‑26, but these projections do not include any potential effects of House Resolution 1: One Big Beautiful Bill Act (H.R. 1), which was signed by the President on July 4. The box below gives a high‑level description of the major changes in H.R. 1 for health and human services programs, as well as some late session state responses.

Figure 6

Total State and General Fund Expenditures

(Dollars in Millions)

|

Revised |

Enacted |

Change From 2024‑25 |

|||

|

2023‑24 |

2024‑25 |

Amount |

Percent |

||

|

General Fund |

$205,670 |

$233,577 |

$228,366 |

‑$5,211 |

‑2% |

|

Special funds |

93,320 |

98,637 |

88,799 |

‑9,838 |

‑10 |

|

Budget Totals |

$298,991 |

$332,214 |

$317,164 |

‑$15,050 |

‑5% |

|

Bond funds |

$4,255 |

$5,720 |

$3,886 |

‑$1,834 |

‑32% |

|

Federal funds |

149,484 |

172,349 |

174,506 |

2,157 |

1 |

|

Note: Reflects administration estimates of budget actions taken through July 1, 2025. |

|||||

House Resolution 1—One Big Beautiful Bill Act

Major Federal Changes to Health and Human Services Programs. Federal House Resolution 1 of 2025 (H.R. 1)—the One Big Beautiful Act passed by Congress and signed by the President in July 2025—introduced multiple, significant changes to states’ health and human services programs. These changes primarily impact states’ Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Programs (SNAP, known as CalFresh in California) and Medicaid (known and Medi‑Cal in California). California’s programs will be affected in a number of ways, including by tightening eligibility, reducing federal funding for services and programs, and placing stricter limits on the use of certain financing mechanisms. The H.R. 1 changes to these programs will be phased in over multiple years, beginning in 2025 and continuing through federal fiscal year 2028.

State Spending Plan Actions in Response to H.R. 1. As part of the final 2025‑26 budget package, the Legislature provided modest funding and made some statutory changes in response to the more immediate impacts anticipated as a result of H.R. 1. These legislative actions were primarily administrative in nature—focusing on ensuring that (1) the state and counties have the funding needed to implement the changes, (2) the computer systems and staffing are positioned to operationalize the changes, and (3) actions are taken now to reduce possible future federal fiscal penalties included in H.R. 1. It is important to note that, although the final budget package did not include any funding to backfill any anticipated lost benefits for individuals, it did provide some select augmentations for certain health and food programs in response to H.R. 1 provisions. For example, the spending plan includes enhanced funding for food banks and to help ensure access to abortion services.

Schools and Community College Budget

Overall School and Community College Funding Up $2 Billion. School and community college spending in California is governed by the rules of Proposition 98. The state meets the Proposition 98 funding requirement through a combination of state General Fund and local property tax revenue. Compared with the June 2024 enacted budget level, the total requirement is up $3.9 billion across 2024‑25 and 2025‑26 (Figure 7). This increase primarily reflects a higher requirement in 2024‑25 due to higher General Fund revenue estimates. A decrease in the 2025‑26 requirement partially offsets this increase. The budget, however, funds an increase of only $2 billion over the two years. (The difference reflects the $1.9 billion settle‑up obligation the state will be required to pay in the future.) Of this additional funding, the state General Fund covers $1.2 billion and local property tax revenue covers $797 million.

Figure 7

Tracking Changes in Proposition 98 Funding

(In Millions)

|

2024‑25 |

2025‑26 |

Change Across Both Years |

||||||

|

June 2024 (Enacted) |

June 2025 (Revised) |

Change From June 2024 Enacted |

June 2025 (Enacted) |

Change From June 2024 Enacted |

||||

|

Proposition 98 Guarantee |

$115,283 |

$119,946 |

$4,663 |

$114,558 |

‑$724 |

$3,938 |

||

|

Funding Allocated |

$115,283 |

$118,029 |

$2,746 |

$114,558 |

‑$724 |

$2,022 |

||

|

By Source: |

||||||||

|

General Fund |

$82,612 |

$85,711 |

$3,099 |

$80,738 |

‑$1,875 |

$1,224 |

||

|

Local property tax |

32,670 |

32,317 |

‑353 |

33,821 |

1,150 |

797 |

||

|

By Segment: |

||||||||

|

K‑12 schools |

$101,121 |

$104,101 |

$2,979 |

$102,055 |

$933 |

$3,913 |

||

|

Community colleges |

13,108 |

13,473 |

366 |

12,959 |

‑149 |

217 |

||

|

Reserve deposit/withdrawal (+/‑) |

1,054 |

455 |

‑599 |

‑455 |

‑1,509 |

‑2,108 |

||

|

Funding Owed (Settle Up) |

— |

$1,917 |

$1,917 |

— |

— |

$1,917 |

||

Fully Withdraws Proposition 98 Reserve Balance. The Proposition 98 Reserve is a statewide reserve account for school and community college funding. Constitutional formulas and legislative actions determine the size of the deposit or withdrawal each year. The June 2025 budget package rescinds a $1.1 billion discretionary deposit into this account in 2024‑25. It makes a new mandatory $455 million deposit in 2024‑25 and a mandatory withdrawal of this same amount in 2025‑26. These actions together draw down the entire balance.

Shifts Ongoing Funding From Community Colleges to Schools. The state typically divides Proposition 98 funding between schools and community colleges using an uncodified methodology known as “the split.” The methodology involves allocating about 89 percent of the available funding to schools and about 11 percent to community colleges, with certain expenditures excluded from these percentages. The budget establishes a new exclusion, beginning in 2025‑26, for the costs associated with the recent expansion of transitional kindergarten. Compared with the previous methodology, this modification shifts $233 million in ongoing Proposition 98 funding from community colleges to schools.

Uses One‑Time Savings to Cover Ongoing Program Costs. The budget funds several increases for ongoing school and community college programs, including a 2.3 percent cost‑of‑living adjustment (COLA). These actions increase the cost of ongoing programs beyond the ongoing Proposition 98 funding level by nearly $1.7 billion. To cover the gap, the budget relies upon one‑time savings generated through three main actions: (1) deferring payments from 2025‑26 to 2026‑27, (2) withdrawing funds from the Proposition 98 Reserve, and (3) repurposing some unused Proposition 98 funds from previous fiscal years. These savings allow the state to cover the cost of these increases in 2025‑26. Entering 2026‑27, however, the savings expire and the state will need to cover the $1.7 billion shortfall with new ongoing funds, ongoing reductions, or additional one‑time actions.

State Appropriations Limit

Under Proposition 4 (1979), the Constitution limits how the state can spend revenues that exceed a certain limit—a set of formulas known as the SAL. During the revenue surges in the early 2020s, the SAL was an important constraint in the budget process and had significant implications for the Legislature’s budget decisions. For the last few years, however, the SAL has not been salient to the budget process. This is because declines in revenues have meant the state has more room under the limit. Figure 8 provides an overview of the SAL estimates in this year’s budget. As the figure shows, the state is expected to have room across all years in the budget window, including $15 billion in 2023‑24, $9 billion in 2024‑25, and $35 billion in 2025‑26.

Figure 8

State Appropriations Limit (SAL) Estimates

(In Billions)

|

2023‑24 |

2024‑25 |

2025‑26 |

|

|

SAL Revenues and Transfers |

$233.4 |

$258.6 |

$252.6 |

|

Exclusions |

‑106.6 |

‑119.5 |

‑120.5 |

|

Appropriations Subject to the Limit |

$126.8 |

$139.0 |

$132.1 |

|

Limit |

$141.5 |

$147.6 |

$166.9 |

|

Room/Negative Room |

$14.7 |

$8.5 |

$34.8 |

|

Excess Revenues? |

No |

||

|

Note: Reflects administration estimates of budget actions taken through July 1, 2025. |

|||

Evolution of the Budget

This section provides an overview of the 2025‑26 budget process. Figure 9 contains a list of the budget‑related legislation passed on or before July 1, 2025.

Figure 9

Budget‑Related Legislation Passed on or Before July 1, 2025

|

Bill Number |

Chapter |

Subject |

|

Budget Bills and Amendments |

||

|

SB 101 |

4 |

2025‑26 Budget Act |

|

ABX1 4 |

1 |

Amendments to the 2024‑25 Budget Act |

|

SBX1 3 |

2 |

Amendments to the 2024‑25 Budget Act |

|

SBX1 1 |

3 |

Amendments to the 2024‑25 Budget Act |

|

AB 100 |

2 |

Amendments to the 2023‑24 Budget Act and 2024‑25 Budget Act |

|

AB 102 |

5 |

Amendments to the 2025‑26 Budget Act |

|

AB 104 |

77 |

Amendments to the 2025‑26 Budget Act |

|

SB 103 |

6 |

Amendments to the 2022‑23, 2023‑24, and 2024‑25 Budget Acts |

|

Trailer Bills |

||

|

AB 116 |

21 |

Health |

|

AB 118 |

7 |

Human services |

|

AB 121 |

8 |

Education finance |

|

AB 123 |

9 |

Higher education |

|

AB 130 |

22 |

Housing |

|

AB 134 |

10 |

Public safety |

|

AB 136 |

11 |

Courts |

|

AB 137 |

20 |

General Government |

|

AB 143 |

12 |

Developmental services |

|

SB 120 |

13 |

Early childhood education and childcare |

|

SB 124 |

14 |

Public resources |

|

SB 127 |

15 |

Climate change |

|

SB 128 |

16 |

Transportation |

|

SB 131 |

24 |

Public resources |

|

SB 132 |

17 |

Taxation |

|

SB 141 |

18 |

California Cannabis Tax Fund |

|

SB 142 |

19 |

Deaf and disabled telecommunications program |

|

Note: This figure includes budget bills and trailer bills identified in Section 39.00 in the 2025‑26 Budget Act that were passed by the Legislature on or before July 1, 2025. Ordered by bill number. |

||

Governor’s January Proposal

January Budget Roughly Balanced. Governor Newsom’s administration presented its proposed state budget to the California Legislature on January 10, 2025. At the time, both our office and the administration found that the underlying condition of the budget was roughly balanced. (In other words, we did not describe the budget as having a surplus or a deficit.) A key reason this was true was that, in June 2024, the Legislature took proactive steps to address the anticipated budget problem for 2025‑26. (These actions are described at a high level earlier in this report.)

Governor’s Budget Included Discretionary Proposals That Used and Created Budget Capacity. The Governor’s budget included discretionary proposals, which are those that are not already committed to under current law or policy, that both used and created budget capacity. In particular:

- Savings Proposals Provided $2.2 Billion in Short‑Term Budget Capacity. Some January proposals provided short‑term budget savings, creating more budget capacity. These proposals resulted in $2.2 billion in General Fund savings within the budget window. This total included a proposal to provide $1.6 billion less in total funding for schools and community colleges than the estimated constitutional minimum funding level for 2024‑25, generating a future settle‑up payment of the same amount. In addition, the January budget increased revenues by $300 million and shifted nearly $300 million in General Fund spending to the Proposition 4 (2024) climate bond.

- Discretionary Proposals Used $700 Million Budget Capacity. The budget also included new discretionary proposals that used budget capacity by increasing spending or reducing revenues. These totaled roughly $700 million, including nearly $600 million in new spending proposals and $150 million in revenue reductions associated with expansions to existing tax expenditures and the creation of new ones.

Governor’s May Revision

In Spring, Revenues Exceeded Expectations, but Outlook for Future Growth Weakened. Following release of the January budget, revenues for the prior and current years came in $6 billion above expectations, primarily due to stronger‑than‑anticipated personal income tax collections, which were running $4 billion ahead of prior projections as of April. Ordinarily, such collections would indicate a stronger revenue outlook. However, both our office and the administration lowered our revenue projections for 2025‑26, with the administration revising its forecast downward by $11 billion. Several factors contributed to tempered revenue expectations for 2025‑26, including: the state’s stagnant economy, uncertainty about the sustainability of recent stock market gains, and potential negative effects from expanded tariffs.

Costs of State Programs—Particularly Medi‑Cal—Exceeded Expectations After January Budget. Compared to the Governor’s January budget, the administration’s May Revision estimated that baseline spending (excluding Proposition 98 spending on schools and community colleges) was $12 billion higher. This was an unusually large upward revision in spending for the budget window. The increase was primarily driven by higher projected costs in the Medi‑Cal program, which were estimated to exceed January levels by $10 billion over the three‑year budget window. This increase was largely due to higher‑than‑anticipated per‑enrollee costs, reflecting a combination of factors such as increased utilization of services, rising medical care prices, and expanded use of high‑cost specialty drugs. Although these cost pressures affect all enrollee groups, the administration attributed a significant share of the increase to higher costs associated with individuals with UIS.

As a Result, a $14 Billion Budget Problem Emerged. Taken with other factors—such as new discretionary spending proposals and lower required General Fund spending on schools and community colleges—the net effect of these changes was the emergence of a $14 billion budget problem at the time of the May Revision. To address this shortfall, the Governor proposed $9.5 billion in spending‑related solutions, including reductions ($4.9 billion), fund shifts ($3.2 billion), and delays ($1.3 billion). A significant portion of these solutions were ongoing, and under the administration’s forecast, their value would grow to $17.5 billion by 2028‑29.

May Revision Focused on Reducing Growth in Medi‑Cal. Reductions to the Medi‑Cal program accounted for roughly two‑thirds of the ongoing spending reductions proposed in the May Revision. These changes were intended to substantially slow the program’s projected cost growth in future years. Under our estimates, the May Revision proposals would have reduced Medi‑Cal’s out‑year cost growth from about 9 percent (as our office estimated in November 2024) to approximately 1 percent.

Legislature’s Budget

The Legislature passed an initial budget on June 13, 2025. The Legislature’s budget package differed structurally from the Governor’s May Revision in two key ways. First, it included two new major actions to increase budget capacity. Second, it used that additional capacity to reject some of the Governor’s proposed spending solutions and to fund other augmentations. We describe these major structural differences in more detail below.

Legislative Actions Increased Budget Capacity by $5 Billion. The Legislature’s budget package included two major actions that increased available budget capacity by a combined $5 billion. First, it expanded internal borrowing by approximately $2.5 billion. This included increasing the size of the Medi‑Cal‑related cash flow maneuver by $1 billion and making a $1.5 billion loan from the state’s internal cash resources to the General Fund. (The final budget maintained these actions, but as of this writing, we understand DOF will administer this as a set of traditional special fund loans, rather than one loan from the state’s cash resources. DOF is still working to identify the fund[s] that would make these loans.) Second, the budget reduced the 2025‑26 year‑end balance of the SFEU from $4.5 billion to $2 billion, freeing up an additional $2.5 billion in budget capacity. (The final budget reflected an SFEU balance at the same level of the Governor’s May Revision.)

Legislative Budget Made Changes to May Revision Solutions and Provided Targeted Augmentations. The Legislature used the additional budget capacity to modify several of the Governor’s May Revision proposals and to fund a limited number of augmentations. In the Medi‑Cal program, for example, the budget restored the asset limit to $130,000, rather than adopting the Governor’s proposed limits of $2,000 per individual and $3,000 per couple. It also modified the Governor’s proposal to establish premiums for the UIS population by reducing the monthly premium from $100 to $30, and delayed the proposed $1.1 billion ongoing reduction to Health Centers and Rural Health Clinics. Beyond Medi‑Cal, the legislative package also rejected the Governor’s proposal to reduce UC and CSU by 3 percent ongoing (instead deferring payments to the universities but providing the cash earlier to offset the effects of those deferrals) and rejected the Governor’s proposal to cap overtime hours for In‑Home Supportive Services providers. In addition, the budget included a limited number of augmentations, particularly for the MCS program and various housing and homelessness initiatives.

Final Budget Package

The Legislature passed an amended budget act and associated trailer bills on June 27, 2025. The Legislature also took some additional actions later in the legislative session, which are listed in Figure 10. The next section of this report describes the major features of the final budget package.

Figure 10

Budget‑Related Legislation Passed After July 1, 2025

|

Bill Number |

Chapter |

Subject |

|

Budget Bills and Amendments |

||

|

AB 104 |

77 |

Amendments to the 2025‑26 Budget Act |

|

SB 105 |

104 |

Amendments to the 2021‑22, 2023‑24, 2024‑25, and 2025‑26 Budget Acts |

|

Trailer Bills |

||

|

AB 138 |

78 |

State bargaining |

|

AB 144 |

105 |

Health |

|

AB 149 |

106 |

Public resources |

|

AB 154 |

609 |

Climate disclosures |

|

SB 119 |

79 |

Social services |

|

SB 146 |

107 |

Human Services |

|

SB 147 |

744 |

Education finance |

|

SB 148 |

745 |

Higher education |

|

SB 151 |

108 |

Early childhood education and child care |

|

SB 153 |

109 |

Transportation |

|

SB 155 |

649 |

California Civic Media Program |

|

SB 156 |

110 |

Labor |

|

SB 157 |

111 |

Public safety |

|

SB 158 |

650 |

Land use |

|

SB 159 |

112 |

Taxation |

|

SB 160 |

113 |

Background check |

|

SB 161 |

114 |

State employment |

|

SB 162 |

115 |

Elections |

|

Note: This figure includes budget bills and trailer bills identified in Section 39.00 in the 2025‑26 Budget Act that were passed by the Legislature after July 1, 2025. Ordered by bill number. |

||

Budget Act Included Language That Placed Budget Contingent on Passage of SB 131. Control Section 37.00 of Chapter 5 of 2025 (AB 102, Gabriel) contained extraordinary language that made the entire state budget contingent on the passage of SB 131, a trailer bill, by June 30, 2025. SB 131 appropriated funding for a homelessness‑related program and contained a number of policy changes to the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA). (The CEQA changes are described in more detail in the section on major features below.) After the Legislature enacted Chapter 5 and Chapter 24 of 2025 (SB 131, Committee on Budget and Fiscal Review), the Legislature enacted Chapter 77 of 2025 (AB 104, Gabriel), which repealed Control Section 37.00.

Major Features of the 2025‑26 Spending Plan

This section briefly describes the major spending actions in the 2025‑26 budget package, including some actions that were taken as part of special sessions. We also discuss the programmatic features of the budget in more detail in a series of online publications. In the box on the next page, we also describe special session actions taken that have budgetary implications.

K‑14 Education

Funds COLA and a Few Other Ongoing Augmentations. The state calculates the statutory COLA each year based on a price index published by the federal government. For 2025‑26, the budget provides $2.2 billion to cover a 2.3 percent COLA for existing school and community college programs. For schools, the budget also provides an ongoing increase of $607 million for the Expanded Learning Opportunities Program. (This program funds before and after school activities and summer enrichment.) This augmentation will increase the share of districts qualifying for the program’s higher “tier 1” funding rate. For community colleges, the budget also provides $140 million to cover 2.35 percent enrollment growth across 2024‑25 and 2025‑26.

Funds One‑Time Discretionary Grants. For schools, the budget provides $1.7 billion for the Student Support and Professional Development Discretionary Block Grant. Districts can use these funds for any local purpose, but trailer legislation encourages them to prioritize teacher training and professional development, teacher recruitment and retention, career pathways for high school students, and dual enrollment programs. The state will distribute funds on an equal per‑pupil basis (about $312 per student). For community colleges, the budget provides $60 million for the Student Support Block Grant. Districts can use these funds for a range of student services, including basic needs (such as food, housing, and transportation), financial aid, counseling, and job placement activities. The state will allocate funds based on student headcount and the share of students qualifying for fee waivers or nonresident tuition exemptions, with a minimum grant of $150,000 per college in each district. In addition to these discretionary grants, the budget funds several smaller grants for schools related to learning recovery, teacher training and recruitment, school meals, and career technical education. It also funds several smaller grants for community colleges focusing on other student support initiatives and career technical education.

Implements Payment Deferrals. The budget reduces spending in 2025‑26 by deferring $2.3 billion in payments to 2026‑27. Of this amount, $1.9 billion pertains to schools. The state will implement the school deferral by shifting a portion of the June 2026 payment to July 2026. The law exempts districts and charter schools that can demonstrate the delay would make them unable to meet their financial obligations. The remaining $408 million in deferrals pertains to community colleges. The state will implement the community college deferral by moving payments from May and June 2026 to July 2026. The purpose of these deferrals is to free up funding for additional one‑time and ongoing spending that would otherwise exceed the available Proposition 98 funding in 2025‑26.

Health

Adopts Ongoing Budget Solutions in Medi‑Cal, With a Focus on Undocumented Immigrants. To help address a multiyear budget problem, the spending plan reflects a number of ongoing budget solutions in Medi‑Cal. The largest pertain to adults with UIS. The UIS population largely consists of undocumented individuals, but also includes certain lawful immigrants lacking citizenship status. Medi‑Cal services to this population are relatively costly to the state because they are eligible for federal funds in only limited cases. The UIS‑related budget solutions mostly begin in 2026 and are estimated to result in over $5 billion of General Fund savings by 2028‑29. They affect several areas, including eligibility (a freeze on new enrollment for comprehensive coverage), benefits (the end of dental coverage), provider rates (lower payments to safety net clinics for services to the UIS population), and new cost‑sharing requirements (a new $30 monthly premium to access comprehensive coverage).

Implements First Year of Proposition 35 (2024), With a New Limited‑Term Budget Solution. In November 2024, voters passed Proposition 35, which creates new rules over how the state spends money from the managed care organization (MCO) tax. A tax on health plan enrollment, the MCO tax historically has helped support the existing Medi‑Cal program. Proposition 35 largely continues to use the associated tax funds to support Medi‑Cal, but with a greater focus on expanding, rather than maintaining, the program. Accordingly, the spending plan includes an initial plan to implement Proposition 35’s rules over the next two years. The plan supports a number of ongoing and one‑time augmentations ($5.2 billion MCO tax funds over two years), including provider rate increases and workforce initiatives. Some of the supported provider rate increases are scored as a limited‑term budget solution to the General Fund ($1.6 billion over 2025‑26 and 2026‑27). This is because the state had previously planned to cover the cost of the increases using General Fund support.

Higher Education

State Defers Rather Than Reduces Base University Funding in 2025‑26. The budget defers $274 million General Fund for UC and CSU combined from May/June to July 2026, thereby generating one‑time state savings in 2025‑26. The deferral equates to 3 percent of General Fund support for UC and CSU. The deferral takes the place of earlier proposed ongoing General Fund reductions (of 3 percent in the May Revision and 7.95 percent in the Governor’s budget). The state offers UC and CSU short‑term, no‑interest General Fund loans, if needed, in response to cash flow challenges resulting from the payment deferrals. The budget plan does not specify when the state would provide a one‑time back payment to retire these deferrals. Beyond General Fund support, both UC and CSU are raising additional ongoing revenue through increases in their tuition charges and anticipated enrollment growth. The state budget also includes a total of $157 million General Fund for one‑time UC and CSU initiatives.

State Modifies University Funding Plan for Next Couple of Years. Under the Governor’s compact with the universities, the Governor intended to provide annual 5 percent base increases through 2026‑27. Instead of providing a 5 percent base increase in 2025‑26, the multiyear budget plan includes intent to provide UC and CSU each a 2 percent increase in 2026‑27, followed by a 3 percent base increase in 2028‑29 (both attributable to 2025‑26). In 2027‑28, the state also intends to provide to a one‑time back payment totaling $493 million to UC and CSU (also attributable to 2025‑26).

Budget Includes Higher Financial Aid Spending in the Current and Budget Years. Specifically, for 2024‑25, the package increases ongoing General Fund by a total of $187 million from the June 2024 enacted level to cover higher‑than‑anticipated costs in the Cal Grant and MCS programs. From the revised 2024‑25 level, the budget includes a $243 million ongoing General Fund augmentation in 2025‑26 to cover projected cost increases in the Cal Grant program. For the MCS program, the state changes its budgetary approach beginning in 2025‑26—basically converting MCS from a typical categorical program to an entitlement program funded one year in arrears. Under previous state law, the state adjusted award coverage, as needed, to remain within the annual state appropriation. Under the new rules, the state set MCS award coverage at 35 percent of remaining student financial need for 2025‑26. The state is covering costs in 2025‑26 using a General Fund loan. On August 11, 2025, the Governor issued an executive order authorizing a loan of $996 million. The state intends to provide an associated budget appropriation in 2026‑27.

California Environmental Quality Act

Budget Package Addresses State’s Long‑Standing CEQA Policy. The budget package included a number of notable policy changes aimed at speeding up and streamlining CEQA, which was originally enacted by the Legislature in 1970. Unless a project falls under a statutory or certain other type of exemption, public agencies (such as cities and counties) generally must conduct a detailed study of the potential environmental effects of new housing construction (and many other types of development) prior to approving it. These studies, known as negative declarations and environmental impact reports, can provide valuable information to decision‑makers and the public and help to avoid unnecessary environmental impacts (pertaining to traffic, air and water quality, and other matters). Yet, required CEQA studies generally are time consuming and costly and the CEQA process can be used to stop or limit housing and other development. In addition, CEQA’s complicated procedural requirements give development opponents significant opportunities to continue challenging housing projects after local governments have approved them.

Amends CEQA Requirements Pertaining to Various Housing and Other Development. The changes, which are contained in three budget trailer bills, include: (1) narrowing the scope of existing required environmental reviews for housing projects that meet all but one criterion for an exemption from the CEQA process and (2) eliminating the requirement for CEQA review entirely when local governments rezone (change land‑use restrictions for) neighborhoods to meet their state‑mandated housing goals, subject to certain restrictions. In addition, trailer bill legislation creates new exemptions from CEQA requirements for various categories of projects, including specified “infill” housing developments (such as certain projects on vacant land within an urban area), farmworker housing, rural health clinics, day care centers, food banks, broadband deployment in a right‑of‑way, and advanced manufacturing facilities (with each exemption type subject to various requirements and limitations). The trailer bill legislation also makes some limited changes to permitting rules for certain residential projects in the coastal zone.

Authorizes New Statewide Vehicles Miles Traveled (VMT) Mitigation “Bank.” In addition, the budget package creates a new option for developers to meet their transportation‑related CEQA requirements for projects. Specifically, trailer bill language allows projects to mitigate their VMT impact (at the discretion of the local public agency) by paying a fee. Fee revenue is to be deposited into a fund administered by the Department of Housing and Community Development and used to fund VMT‑reducing projects such as affordable housing near transit stops. The Governor’s Office of Land Use and Climate Innovation is required by July 2026 to issue initial guidance for this new program, including providing details such as the methodologies for determining the amount of the fee and estimating the anticipated reduction in VMT resulting from payment of the fee.

Recent Voter‑Approved Bond Allocations

Budget Contains First Allotment of Proposition 2 Bond Funding. Proposition 2, approved by voters in November 2024, authorizes $10 billion in state general obligation bonds for school and college facilities. Of this amount, $8.5 billion is for schools and $1.5 billion is for community colleges. The 2025‑26 budget package begins drawing down these bond funds. The budget assumes the state will award $1.5 billion for school projects, consistent with the state’s existing application processing rate. For community colleges, the 2025‑26 budget package authorizes the preliminary plans and working drawings phases of 29 new projects and the design‑build phase of 1 existing student housing project. The total Proposition 2 cost across all phases of these 30 projects is $863 million.

Proposition 4 (Climate Bond). The budget package appropriates $3.5 billion from Proposition 4, the $10 billion bond approved by voters in November 2024 for climate and environmental activities. This includes $181 million provided through actions taken in April to amend the 2024‑25 budget (Chapter 2 of 2025 [AB 100, Gabriel]) and $3.3 billion approved through Chapter 104 of 2025 (SB 105, Wiener). This total includes $1.2 billion for water‑related activities and $600 million for projects to improve the state’s wildfire resilience.

Cap‑and‑Invest Program Spending

2025‑26 Spending Package Includes Over $4 Billion From GGRF. The budget package assumes spending totaling $4.1 billion from GGRF in 2025‑26. The bulk of these funds support existing statutory commitments—most of which are continuously appropriated—such as for the high‑speed rail project and programs for housing, transit, forest health, and drinking water. As noted earlier, 2025‑26 GGRF spending also includes a $1 billion backfill for CalFire’s operational budget in order to achieve General Fund savings while avoiding programmatic impacts. At the end of the legislative session, Chapter 104 of 2025 (SB 105, Weiner) appropriated an additional $540 million from GGRF for a number of activities including related to transit, zero‑emission vehicles, and community air protection.

Program Reauthorization Legislation Will Affect GGRF Allocations in Future Years. Separate from the budget package, the Legislature approved legislation that will affect GGRF spending allocations beginning in 2026‑27. Chapter 117 of 2025 (AB 1207, Irwin) extends the statutory authorization for the existing cap‑and‑trade program from 2030 to 2045, makes a number of changes to the program’s structure, and renames it “cap‑and‑invest.” Chapter 121 of 2025 (SB 840, Limón) revises the existing statutory allocation amounts that support particular activities, including changing several from being set percentages of GGRF revenues to fixed amounts. For example, beginning next year, the high‑speed rail project will receive $1 billion annually rather than 25 percent of auction revenues. The legislation also reserves $1 billion annually from GGRF for the Legislature to allocate based on its budget priorities each year, and expresses intent for particular activities to be funded in 2026‑27.

Appendices

Note: In this online version of this report, we include a series of Appendix tables that have detailed information on the discretionary spending decisions and budget solutions reflected in the 2025‑26 Budget Act.