May 17, 2025

The 2025‑26 Budget

Initial Comments on the

Governor’s May Revision

Key takeaways

A Budget Problem Has Emerged Since January. Overall, our assessment of the state’s budget condition for 2025‑26 is very similar to that of the administration’s assessment—namely, since January, when the budget was roughly balanced, a budget problem has emerged. We estimate the administration solved a $14 billion budget problem (similar to the $12 billion budget problem cited by the Governor). This budget problem is driven by two key factors: higher baseline spending, most notably in Medi‑Cal, and lower revenues, reflecting diminished expectations for both the personal income tax and the corporation tax.

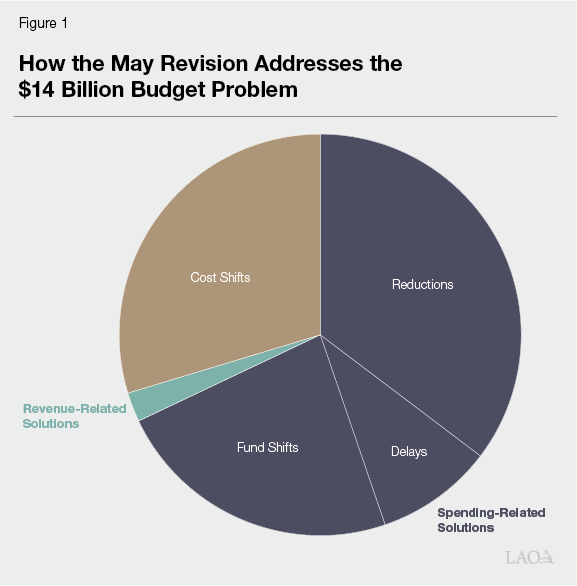

The Governor Mainly Proposes Addressing the Budget Problem With Spending Solutions. The May Revision proposes $9.5 billion in spending solutions, including about $5 billion in spending reductions. A significant share of these spending solutions are ongoing and grow to $17.5 billion by the last year of the administration’s forecast—helping to address, but not fully solve, the state’s persistent multiyear deficits. Notably, the administration does not propose using any more in reserves to address this new budget problem, which is prudent.

Recommend Legislature Maintain Overall May Revision Structure. We recommend the Legislature address the budget shortfall with a similar approach that the administration took, namely adopting solutions that primarily put the state on more solid fiscal footing, rather than those that delay or exacerbate future problems. Moreover, we recommend avoiding committing to new activities. Finally, although we have not previously recommended the Legislature take decisive action to address the structural deficits, the state’s persistent fiscal imbalance and the added downside risks—particularly from potential federal actions—suggest a need for a more proactive approach. As such, we view the Governor’s focus on reducing multiyear spending as a reasonable and appropriate step. That said, the Legislature could allocate the mix of solutions differently, for example, by changing the types of programs, types of reductions, or mix of spending and revenue solutions adopted.

Introduction

On May 14, 2025, Governor Newsom presented a revised state budget proposal to the Legislature. This annual proposed revised budget is referred to as the May Revision. In this brief, we provide a summary of and comments on this revised budget, focusing on the Governor’s proposals for and the overall condition of the state General Fund—the budget’s main operating account. At this time, our assessment is based on the administration’s revenue projections and spending estimates. In the coming days, we will analyze the plan in more detail, provide additional comments in hearing testimony, and update our multiyear forecast of the budget’s condition using our own projections and estimates. (The information presented in this brief is based on our understanding of the administration’s proposals as of May 15, 2025. In many areas, our understanding of the proposals will continue to evolve.)

The Budget Problem

In this section, we present our estimates of the budget problem that the Governor addressed in the May Revision, focusing on the three‑year budget window under consideration: 2023‑24 to 2025‑26. We begin by reviewing the evolution of the budget condition, detailing how the outlook deteriorated from roughly balanced in January to a deficit today. Then, we summarize the proposals the Governor puts forward to address the budget problem.

What Is a Budget Problem? A budget problem—also called a deficit—arises when resources for the upcoming budget are insufficient to cover the costs of currently authorized services. A budget problem is inherently a point‑in‑time estimate that reflects information available at the time of development, forecasts of future revenues and spending, and assumptions about the extent to which changes in costs are due to current policy (that is, whether or not they are “baseline changes”). When changes in costs do not occur automatically under current policy, we count them as budget solutions or augmentations. We take this approach in order to provide the Legislature visibility into the full scope of the administration’s choices. The remainder of this section walks through the sources of our differences with the administration and how those differences impact the budget problem estimate.

We Estimate Governor Addressed a $14 Billion Budget Problem. Overall, our assessment of the state’s budget condition for 2025‑26 is similar to that of the administration. While we estimate the administration addressed a $14 billion budget problem, the Governor cited a figure of $12 billion. The reason for this difference is mainly that the May Revision includes a number of proposals that generate budget savings that our office considers budget solutions, but the administration would count as workload budget changes. Most of these are related to proposals made in the January Governor’s budget. For example, this includes a proposal to provide $1.3 billion less in total funding for schools and community colleges than the estimated constitutional minimum for 2024‑25. This yields one‑time General Fund savings in that year but creates a “settle‑up” obligation that will need to be paid in a future year if 2024‑25 revenues remain unchanged. Smaller proposals, such as shifting nearly $300 million in General Fund spending to the Proposition 4 (2024) climate bond, account for the remaining difference.

Absent Proactive Choices Last Year, Budget Problem Would Be Significantly Larger. In June 2024, the Legislature not only addressed the 2024‑25 budget problem, but also took proactive steps to mitigate the anticipated 2025‑26 budget challenge. The June 2024 budget package included $28 billion in budget solutions for 2025‑26, although savings from some of these actions have since diminished. We provided further detail and updated estimates of these solutions in our January report, The 2025‑26 Budget: Overview of the Governor’s Budget (see Appendix 1). Without this legislative action, the current budget problem would be substantially larger.

How Has the Budget Picture Changed Since January?

In January, both our office and the administration assessed the budget as roughly balanced. Since then, the outlook has weakened, and we now estimate the state faces a $14 billion budget problem. This section outlines the major factors contributing to that change.

Revenues Lower by About $5 Billion. The May Revision downgrades the administration’s revenue estimates by $5 billion. Revenues for prior and current years are up a total of $6 billion, primarily reflecting stronger‑than‑expect personal income tax collections which are running $4 billion ahead of prior projections as of April. In contrast, the administration’s forecast for the budget year is down $11 billion, reflecting diminished expectations for both the personal income tax and the corporation tax.

General Fund Spending on Schools and Community Colleges Lower by $3.9 Billion. Proposition 98 (1998) sets a minimum funding requirement for schools and community colleges based on formulas in the State Constitution. Compared with the Governor’s budget, the General Fund portion of this requirement is down $3.9 billion across 2024‑25 and 2025‑26. As we discuss later in this brief, the May Revision maintains a cost‑of‑living adjustment (COLA) and other spending increases for schools and community colleges despite the drop in funding.

Baseline Spending Higher by $12 Billion. Baseline spending reflects the projected cost of continuing existing services under current law and policy, prior to the adoption of any new budget solutions. Compared to the Governor’s January budget, the administration now estimates baseline spending (excluding Proposition 98 spending on schools and community colleges) is higher by $12 billion. This represents an unusually large revision. For context, the comparable revisions in the prior two budget cycles were $2 billion (2023‑24) and $2.7 billion (2022‑23). The increase is primarily driven by higher costs in the Medi‑Cal program, which are projected to exceed January estimates by $10 billion over the three‑year budget window: roughly $2 billion in 2024‑25 and $8 billion in 2025‑26. According to the administration, this growth is largely due to higher‑than‑anticipated per‑enrollee costs, which reflects a range of factors like greater utilization of services, increased prices for medical care, and expanded use of high‑cost specialty drugs. While these cost increases affect all enrollee groups, the administration attributes a significant share of the growth to higher costs associated with individuals lacking satisfactory immigration status. In addition to Medi‑Cal, the other main driver of increased costs is higher‑than‑expected costs in the In‑Home Supportive Services (IHSS) program, related to both higher caseload and hours per case.

New Discretionary Spending and Revenue Proposals Total Nearly $2 Billion. The January budget included about $700 million in discretionary spending and revenue reductions. The May Revision retains most January proposals, including the Governor’s plan to expand the film tax credit, and adds new proposals that bring the total to nearly $2 billion—$1.6 billion in spending and around $150 million in revenue reductions. These measures require additional budget solutions to maintain budget balance and include:

- Partially Reversing Funding Reductions for the University of California (UC) and California State University (CSU). The largest May Revision discretionary proposal relates to the base funding cuts for UC and CSU. The May Revision reduces planned base cuts from 7.95 percent, as agreed to in last year’s budget, to 3 percent. This change increases ongoing General Fund costs by $267 million for UC and $231 million for CSU.

- Rebenching Proposition 98 for Wildfire‑Related Property Tax Losses. The May Revision proposes rebenching the Proposition 98 minimum funding guarantee to account for property tax revenue losses resulting from the January 2025 Los Angeles wildfires. This policy decision increases the Proposition 98 guarantee, requiring an additional $172 million in General Fund resources over the budget window to offset those losses.

In addition, the administration includes roughly 70 other proposals, each with an estimated cost of less than $100 million. (Appendix 1 provides a full listing of these items.)

All Other Changes Improve Budget Bottom Line by $2 Billion. Across the rest of the budget, the administration estimates a net improvement of $2 billion to the General Fund bottom line. The largest component is a $1.5 billion upward revision to the entering fund balance, primarily driven by higher‑than‑expected reversions of unspent funds and lower required Proposition 2 (2014) debt payments. The lower debt payments reflect weaker projected revenues in 2025‑26, which reduce constitutionally required transfers.

How Does the Governor Propose Addressing the Budget Problem?

Figure 1 summarizes the budget solutions described in this section. The May Revision primarily addresses the budget problem through spending‑related solutions—totaling $9.5 billion—which include reductions ($4.9 billion), fund shifts ($3.2 billion), and delays ($1.3 billion). A significant share of these spending solutions are ongoing and grow to $17.5 billion by 2028‑29 in the administration’s forecast. In addition, the May Revision includes $4.1 billion in cost shifts and $330 million in revenue‑related solutions. Online Appendices 1 and 2 provide a complete list of solutions by program area.

Spending‑Related Solutions

Reductions. Under our definition, a spending reduction occurs when the Governor proposes spending less than what is required under current law or policy—more commonly referred to as a spending cut. The May Revision includes $4.9 billion in such reductions. Key proposals include limiting provider overtime and travel hours in the IHSS program (about $700 million, growing to nearly $900 million), reducing Medi‑Cal payments to clinics that serve patients with unsatisfactory immigration status ($450 million, growing to $1.1 billion), and eliminating certain long‑term care facility benefits for this population (about $300 million, growing to $800 million).

Fund Shifts. Fund shifts occur when the state uses alternative fund sources—such as special funds—to pay for costs typically borne by the General Fund. These actions reduce General Fund spending while displacing spending that otherwise would have been supported by the special funds. Because fund shifts typically result in lower overall state spending, we categorize them as spending‑related solutions. The May Revision includes an estimated $3.2 billion in fund shifts. Major proposals include shifting $1.5 billion in California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection operational costs to the Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund, using $1.3 billion in Proposition 35 (2024) revenues to support base growth in Medi‑Cal, and moving roughly $300 million in climate‑related project costs to the Proposition 4 climate bond (about $270 million of which was initially proposed in January). These actions reduce the availability of these fund sources for other purposes.

Delays. We define a delay as a proposal that reduces expenditures within the budget window (2023‑24 through 2025‑26) but shifts those costs to a future year in the multiyear period (2026‑27 through 2028‑29). In effect, the Governor proposes to defer, rather than eliminate, the spending. The May Revision includes about $1.3 billion in such delays, reflecting the administration’s proposed Proposition 98 settle‑up payment. As a result, associated spending is likely to be higher in the out‑years.

Revenue‑Related Solutions

The Governor’s May Revision maintains a January proposal to change the rules about how taxable profits are determined for financial institutions. The administration estimates this change would increase revenues on an ongoing basis by around $300 million per year.

Cost Shifts

The May Revision includes about $4 billion in cost shifts. We define cost shifts as budget actions that achieve savings in the present, but result in a binding obligation or higher cost for the state in a future year. In that way, these actions can be similar to borrowing, but are often not explicitly structured as such. For example, major categories of cost shifts include:

- Medi‑Cal Maneuver. Under state law, the administration can transfer funds to the Medical Provider Interim Payment (MPIP) Fund to help cover an appropriation deficiency in Medi‑Cal. These transfers are capped as a percent of Medi‑Cal’s appropriation. On March 12, the administration notified the Joint Legislative Budget Committee it had transferred $3.4 billion General Fund (around the maximum allowed) to the MPIP Fund to cover unanticipated cost increases in Medi‑Cal. While this payment has been made on a cash basis, the May Revision proposes that the state not recognize it in the budget this year (instead, it would be recognized over multiple years and fully reflected by 2034). This maneuver essentially creates a loan from the state’s cash resources, and a future obligation that is repaid when the state recognizes the payment that was already made. It conceptually similar to the Proposition 98 funding maneuver used in last year’s budget—for more information on how these types of budget solutions work, see our report: The 2024‑25 Budget: The Proposition 98 Funding Maneuver.

- Special Fund Loans. The May Revision also proposes using special fund loans, a more traditional form of borrowing, to help balance the budget. These loans are made on a budgetary basis from borrowable special funds with unspent balances. There are proposals for two new special fund loans: $150 million from the Unfair Competition Law Fund and $400 million from the Labor and Workforce Development Fund.

Budget Condition

In this section, we describe the overall condition of the General Fund budget after accounting for the May Revision proposals and solutions. We also describe the condition of the school and community college budget.

General Fund Budget

Figure 2 shows the General Fund condition under the May Revision. The state would end 2025‑26 with $4.5 billion in the Special Fund for Economic Uncertainties (SFEU). The SFEU is the state’s operating reserve and essentially functions like an end‑of‑year balance. The State Constitution’s balanced budget provision prohibits the state from enacting a negative SFEU balance for the upcoming fiscal year, in this case, 2025‑26. While historically the state mostly has enacted SFEU balances between $1 billion and $4 billion, the Legislature can choose to set the balance at any level above zero.

Figure 2

General Fund Condition Summary

(In Millions)

|

2023‑24 |

2024‑25 |

2025‑26 |

|

|

Prior‑year fund balance |

$51,769 |

$41,886 |

$34,321 |

|

Revenues and transfers |

195,879 |

225,673 |

214,558 |

|

Expenditures |

205,762 |

233,238 |

226,376 |

|

Ending fund balance |

$41,886 |

$34,321 |

$22,504 |

|

Encumbrances |

$18,001 |

$18,001 |

$18,001 |

|

SFEU balance |

$23,885 |

$16,320 |

$4,503 |

|

Reserves |

|||

|

BSA |

$23,194 |

$18,292 |

$11,192 |

|

SFEU |

23,885 |

16,320 |

4,503 |

|

Safety net |

900 |

— |

— |

|

Total Reserves |

$47,979 |

$34,612 |

$15,695 |

|

SFEU = Special Fund for Economic Uncertainties and BSA = Budget Stabilization Account. |

|||

Under May Revision, Reserves Would Total Nearly $16 Billion at End of 2025‑26. Legislative action taken last year planned for a $7 billion withdrawal from the Budget Stabilization Account (BSA) this year. The Governor’s May Revision maintains that action, but does not propose using additional reserves relative to this action. (The budget also includes formula‑driven adjustments to prior‑year deposits, primarily in 2023‑24, resulting in about $200 million more deposited into reserves.) All told, under the May Revision estimates and proposals, the state would end 2025‑26 with nearly $16 billion in total reserves, including $11 billion in the BSA and $4.5 billion in the SFEU.

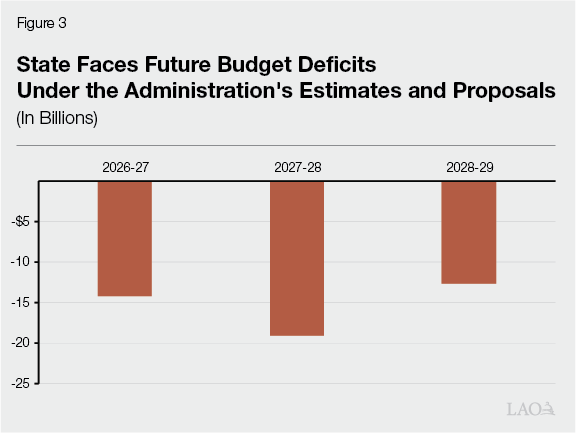

Multiyear Budget Deficits Persist Under the Administration’s Estimates and Proposals. According to the administration’s estimates and assumptions, budget deficits are projected to persist in future years, with operating deficits of approximately $15 billion to $20 billion annually through the outlook period (see Figure 3). These deficits would accumulate, resulting in a negative $42 billion balance in the SFEU by 2028‑29. As a result, these operating deficits represent future budget challenges the Legislature would need to address. The budget outlook will differ under our revenue and spending projections, however. We plan to provide a more detailed analysis of the multiyear budget condition under our own projections in an upcoming report, The 2025‑26 Budget: Multiyear Budget Outlook.

School and Community College Budget

Overall Proposition 98 funding across 2024‑25 and 2025‑26 is $4.6 billion below the January estimate. This change consists of a $3.9 billion decrease in the General Fund portion of the funding requirement and a $753 million decrease in local property tax revenue. Despite this drop, the May Revision continues to fund a COLA for existing school and community college programs (revised down from 2.43 percent in January to 2.3 percent in May) and maintains most of the January spending proposals. To cover the drop in Proposition 98 funding, the Governor proposes four main actions:

- Deferring school and community college payments from the end of 2025‑26 to the beginning of 2026‑27 ($2.4 billion).

- Zeroing out the Proposition 98 Reserve by withdrawing deposits that are no longer required or were previously discretionary ($1.5 billion).

- Withdrawing or reducing several community college proposals mainly involving information technology projects ($400 million).

- Accelerating a settle‑up payment related to the Proposition 98 requirement in 2024‑25, which makes more funding available for school and community college programs ($250 million).

Comments

Budget Structure

Governor’s Revenue Estimates Reasonable. We generally agree with the administration’s assessment of the revenue outlook. Recent collection trends support its upgrade in prior‑ and current‑year revenues. Meanwhile, mounting risks suggest its revenue downgrade in the budget year is warranted. A turbulent federal policy environment poses significant risks to both the state’s already stagnant economy and a potentially overheated stock market that is prone to volatility. This confluence of factors suggests there are limited prospects for continued revenue growth in the coming year.

Focus on Solutions That Do Not Delay or Exacerbate Budget Problems. Both our office and the administration have revised down our forecasts for the budget position since January, reflecting more downside risk in the economy and revenues, and significantly higher‑than‑anticipated costs in key programs, most notably Medi‑Cal. Given these factors and the uncertainty about decisions by the federal government that could reduce funding to the state, we recommend the Legislature address the shortfall with a similar approach that the administration took, namely adopting solutions that primarily put the state on more solid fiscal footing, rather than those that delay or exacerbate future problems. Moreover, we recommend avoiding committing to new activities.

Governor’s Multiyear Spending Reductions Appropriate. Both our office and the administration have forecasted significant out‑year budget deficits in recent years, ranging from $10 billion to nearly $30 billion annually. In addition, our most recent forecast showed that projected spending growth exceeds both projected revenue growth and historical patterns of spending increases. Although we have not previously recommended the Legislature take decisive action to address these structural issues, the state’s persistent imbalance and the added downside risks—particularly from potential federal actions—suggest a need for a more proactive approach. As such, we view the Governor’s focus on reducing multiyear spending as a reasonable and appropriate step. We recommend the Legislature adopt a similar level of ongoing budget solutions in its final budget package.

Maintaining Remaining Reserve Prudent. In the May Revision, the Governor chose not to draw additional funds from the state’s reserves to address the budget shortfall that has emerged since January. Maintaining the state’s reserves in this way would preserve them to be used for future deficits, or as a flexible funding source to avoid sudden disruption to services should there be midyear federal spending changes. For this reason, we recommend the Legislature maintain this approach in the final budget package. Further, the May Revision maintains a January proposal to put certain changes to the state’s reserve policy before voters. This issue continues to deserve the Legislature’s attention and we have provided an analysis of this proposal in our report: Rethinking California’s Reserves.

Budget Choices

Absent New Proposals, Fewer Budget Solutions Would Be Required. The Governor’s May Revision includes nearly $2 billion in new discretionary spending and revenue proposals, including about $900 million in new ongoing spending and $300 million in ongoing revenue reductions. Without these proposals, the state’s budget problem would be smaller, requiring fewer budget solutions now and in the future. While the Legislature may support the Governor’s priorities, accepting these proposals involves trade‑offs. We recommend the Legislature carefully evaluate each new proposal to determine if it warrants inclusion given the state’s fiscal challenges. A high bar should be applied to new proposals, with even greater scrutiny for ongoing commitments, to ensure only the highest‑priority items are adopted in the final budget.

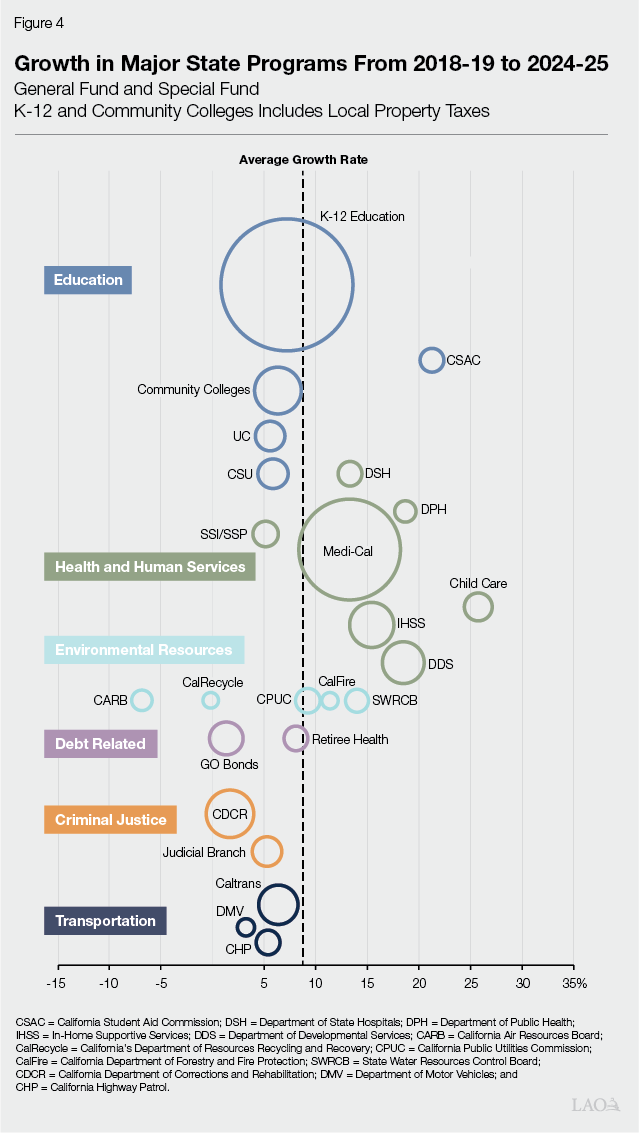

Governor’s Out‑Year Spending Solutions Largely Focus on Large, Fastest Growing Health and Human Services (HHS) Programs. Of the total $9.5 billion in proposed spending solutions in the May Revision, $5.3 billion are proposed in the health and human services area. (Under the administration’s estimates, these solutions grow to $13.6 billion by 2028‑29.) In general, we understand that in putting together this proposed budget, the administration focused on the state’s largest and fastest‑growing programs—specifically Medi‑Cal, IHSS, and the Department of Developmental Services (DDS). Figure 4 shows growth rates across the state’s largest programs over the last decade.

HHS Reductions Largely Achieved Through Limiting Access to Programs. Ongoing reductions to Medi‑Cal, IHSS, and DDS largely are achieved by limiting access in three ways: eligibility, benefits, and administrative requirements. The largest eligibility‑related solution is the freezing of the Medi‑Cal enrollment for individuals 19 and older with unsatisfactory immigration status. The proposed solution would mean adults with unsatisfactory immigration status not currently in the program could not enroll in the future. The May Revision also proposes to limit benefits for this population by terminating dental, IHSS, and certain long‑term care coverage. Lastly, the May Revision includes a few solutions that would increase administrative requirements. These include reinstating a complex asset limit test for Medi‑Cal eligibility and limiting enrollment in the IHSS residual program, which could create administrative challenges for re‑enrolling recipients who lose access to IHSS services due to a loss of Medi‑Cal eligibility. While these proposed solutions would have different impacts, they ultimately would limit access to services.

Legislature Can Choose Another Approach. While we recommend the Legislature maintain the same amount of ongoing solutions as proposed in the May Revision—both in the short and long term—the Legislature could allocate the mix of these solutions differently. For example, the Legislature could adopt proposals over a broader set of program areas. The May Revision does not include major solutions in a few program areas that received larger augmentations in recent years like child care, student aid, or public health (although some of these programs received reductions in the June 2024 budget package). The Legislature also could consider alternative variations of the administration’s proposals, such as limiting Medi‑Cal enrollment for adults with unsatisfactory immigration status based on populations of priority, like those with the lowest income, instead of timing of enrollment. Alternatively, the Legislature could consider reductions in longer‑standing program areas that may no longer be meeting legislative goals. Lastly, the Legislature could consider increasing revenues either through limiting or eliminating tax expenditures or increasing rates. We discuss ways to consider identifying these alternative solutions in our post Undertaking Fiscal Oversight.

Encourage Legislature to Focus on Fiscal Picture, Leave Other Policy Issues for Later. The Legislature has a few weeks to review the May Revision and develop its own budget plan. Finalizing this year’s budget plan involves challenging trade‑offs that likely will impact service levels provided to Californians. As such, we recommend the Legislature defer—without prejudice—the policy‑driven May Revision proposals that have limited budget implications to later in the year (or beyond). These include the administration’s proposals related to streamlining housing production, accelerating Delta conveyance projects, changing requirements for state water quality control plans, regulating pharmacy benefit managers, and creating new state agencies for housing and consumer protection. This would allow the Legislature more time and capacity for sufficient consideration of the potential benefits, implications, and trade‑offs associated with these proposals.