Drew Soderborg

April 10, 2025

Improving Legislative Oversight of Emergency Authorities

- Introduction

- Legislature Has Granted Broad Authority to the Governor to Respond to Emergencies

- Emergency Laws Sometimes Cede Core Legislative Powers Unnecessarily and Lack Adequate Oversight

- Recommendations

- Conclusion

Executive Summary

The Legislature Has Granted Broad Authorities to the Governor to Respond to Emergencies. Because disasters require swift action, the Legislature has granted broad authorities to the Governor to declare states of emergency and respond. Following such a declaration, emergency laws provide the Governor with extensive authorities which are often exercised through executive orders. These authorities include the ability to temporarily amend or make statute and spend any available funds to respond to the emergency.

Emergency Laws Sometimes Cede Core Legislative Power Unnecessarily and Lack Adequate Oversight. We find that the current emergency laws lean more heavily toward giving the Governor flexibility to respond to emergencies than necessary at the expense of the Legislature’s core constitutional powers. This is particularly concerning given that there are often inadequate legislative oversight mechanisms in place. Specifically, we identify the following concerns:

- Governor Can Bypass the Legislative Process Unnecessarily. The Governor determines when a state of emergency exists and, as a result, determines when typical legislative budget and policy processes do not need to be followed. This allows Governors to proclaim states of emergency even in cases where, arguably, normal budget and policy processes could have been used.

- No Process to Ensure Authority Is Promptly Restored to Legislature. There is no formal process to assess whether a state of emergency should remain in effect. This has resulted in many remaining open longer than necessary.

- Limited Role for Legislature in Ongoing States of Emergency. There is no formal way for the Legislature to raise objections to or terminate specific parts of the Governor’s use of emergency authorities. Additionally, the Legislature does not have an opportunity to review and provide oversight of emergency expenditures before they occur.

- Limited Requirements to Provide Legislature With Information on Use of Emergency Authorities. Due to a lack of such requirements, the amount of information provided by the administration on emergency response activities has varied. Similarly, the Legislature has often received little information on how emergency response funds are being used.

- Governor’s Emergency Spending Authority Lacks Oversight Mechanisms. The Governor’s emergency spending authorities are extremely broad and allow the Governor to spend an essentially unlimited amount of funds on emergencies with very little oversight.

In many cases, these aspects of California’s emergency laws stand in contrast to federal, other state, and local emergency laws.

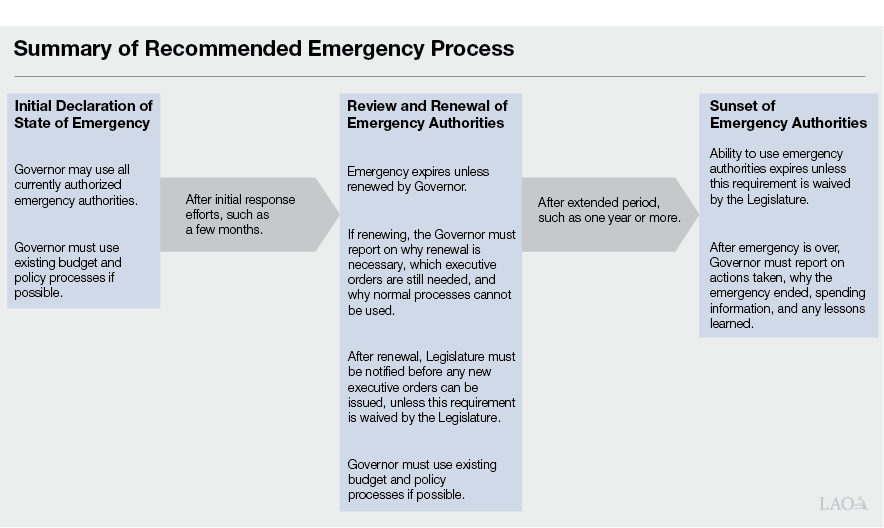

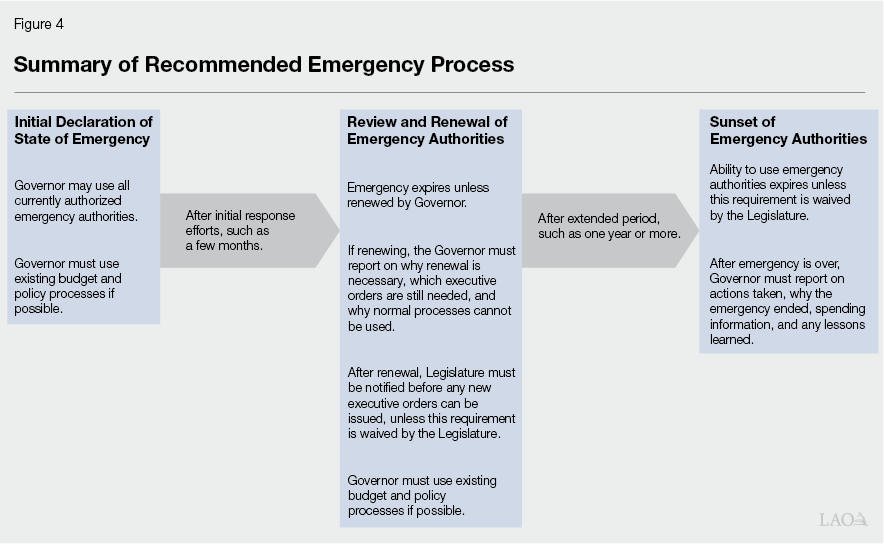

Recommendations. To better balance the Governor’s need for flexibility with the Legislature’s ability to retain its core powers and exercise oversight during and after emergencies, we recommend the Legislature take the steps below, which would result in a new emergency process summarized in the figure.

- Adopt Statute Specifying Governor Should Not Use Emergency Authorities When Existing Processes Suffice. This would minimize the extent to which the Legislature must cede its core powers to the Governor.

- Require States of Emergencies to Expire Unless Renewed by Governor at Specified Time Periods. As part of the renewal, any executive orders not identified as necessary would automatically expire. Going forward, any new executive orders that are needed could only be issued after advanced notification is provided to the Legislature, unless the Legislature waives this requirement.

- Require the Administration to Provide Certain Information Prior to Renewal. This would include: (1) a description of how emergency authorities have been used, (2) conditions that warrant keeping the emergency open, (3) which executive orders are still needed and what actions the Governor expects to take, (4) why those executive orders (rather than normal budget and policy processes) are needed, (5) specific conditions needed to terminate the state of emergency, and (6) anticipated dates for termination.

- Create Sunset for States of Emergency That Are Open for an Extended Period of Time. This would create a mechanism to ensure any authority needed to continue emergency response activities would go through the normal legislative budget and policy processes. However, we recommend allowing the Legislature to waive this requirement for a set amount of time, if conditions warrant.

- Require the Administration to Submit a Report After Emergency Expires. This would enhance legislative oversight by providing the Legislature with more information about how the Governor used emergency authorities.

- Reform Emergency Spending Authorities to Enhance Legislative Oversight. We recommended (1) requiring all emergency augmentations come from one fund, (2) establishing an amount for that fund in the budget, (3) requiring advanced notice to transfer additional monies into the fund and (4) requiring reporting on planned and actual emergency expenditures.

Introduction

California’s diverse landscape and climate mean the state regularly faces emergencies such as wildfires and floods. From time to time, the state also responds to emergencies that are rare due to how infrequent they are—such as earthquakes and public health emergencies—or their size, such as the January 2025 Southern California wildfires. All of these emergencies require swift and coordinated efforts to protect communities. Effective emergency response is critical given the threat emergencies often pose to both life and property.

To help facilitate effective emergency response, the Legislature has granted authority to the Governor to proclaim a state of emergency and given the Governor broad authorities to undertake activities related to proclaimed emergencies. These authorities are designed to give the administration flexibility to rapidly respond to emergencies. In this report, we describe the core constitutional powers of the Legislature, how the Legislature has delegated some of these powers to allow the Governor to exercise emergency authorities during a state of emergency, and how these authorities have been used over time. Next, we assess the degree to which the authorities granted to the Governor are necessary to facilitate emergency response and whether there are adequate oversight mechanisms of this authority in place. Finally, we make various recommendations intended to allow the Legislature to exercise more of its core budget and policymaking powers and ensure there is adequate oversight of the Governor during emergencies, while still preserving considerable flexibility for the state to respond swiftly.

We note that the primary focus of our report is not to assess the state’s responses to recent emergencies, such as the January 2025 Southern California wildfires. Rather, our goal is to take a broader look at the structure of emergency authorities—much of which has been in place for decades—with a focus on ensuring the Legislature has a meaningful role in overseeing emergency response efforts that will inevitably be needed in the future.

Legislature Has Granted Broad Authority to the Governor to Respond to Emergencies

Below, we describe the powers the Constitution provides to the Legislature and how, through statute, the Legislature has delegated some of this power by granting authority to the Governor to respond to emergencies. We also provide an overview of how recent Governors have used this authority.

California Constitution Establishes Core Powers of the Legislature

Legislature Responsible for Enacting Laws, Appropriating Funds, and Levying Taxes. The California Constitution establishes three kinds of power exercised by the state government: legislative, executive, and judicial. The Constitution generally requires that these powers be separately exercised by the Legislature, the Governor, and the judicial branch. Core powers of the Legislature include enacting laws, appropriating funds, and levying taxes through the annual state budget and other legislation. In contrast, the Governor’s core executive powers include executing and enforcing statutes, while the core powers of the judicial branch include interpreting statutes and determining their constitutionality.

Legislative Budget and Policy Process Designed to Be Deliberative. The exercise of legislative powers—namely making budget and policy decisions—can often take time. For example, the Legislature typically deliberates over the annual state budget bill from January until June. Moreover, policy bills often take at least several months to be reviewed, considered, and enacted. This process is designed to allow the Legislature to seek input from stakeholders, consider trade‑offs, and build consensus among a majority of members in each house. In contrast, the Governor can make decisions more quickly.

Legislature Has Granted Governor Authority to Proclaim a State of Emergency

Responding to an Emergency Requires Swift Action. Responding to an emergency frequently requires that actions be taken quickly. Accordingly, in many cases, the deliberative approach typical of legislative decision‑making can be impractical and the Governor can be better positioned to take decisive action. This is compounded by the fact that the Legislature goes into recess for a few months each year. Additionally, the Governor has direct authority over the state entities that carry out emergency response activities. In recognition of these important differences, the Legislature has granted the Governor significant authority and flexibility to respond to state emergencies, as we describe in more detail below.

Statute Establishes Process Allowing Governor to Proclaim a State of Emergency. In 1970, the Legislature adopted the California Emergency Services Act (CESA), which grants the Governor the authority to proclaim a state of emergency when there exist conditions of disaster or extreme peril to the safety of people and property. Under CESA, the Governor may proclaim a state of emergency in an area affected by a natural or human‑made disaster, when (1) requested to do so by the governing body of the local agency affected, or (2) the Governor finds the local authority is inadequate to cope with the emergency. In addition, depending on the severity of the emergency conditions, local, state, and federal agencies can issue other types of emergency declarations. For example, the governing body of an affected local government—such as a city council—can declare a local emergency if it determines a natural or human‑made disaster is or is expected to be beyond its capacity to respond to and recover from. Moreover, at the federal level, the President can also make similar emergency declarations. For example, the President can make a Major Disaster Declaration when there is a natural event beyond the capacity of the state and local governments to respond, typically when the amount of damage caused by disaster events exceeds certain per capita dollar thresholds.

Emergency Proclamations Made in Writing and Often Include Executive Orders. CESA requires the Governor to make emergency proclamations in writing. Governors’ proclamations typically include the specific conditions bringing about the state of emergency, the areas affected, the anticipated impacts, and a list of executive orders that implement the Governor’s emergency authorities (discussed in greater detail below). The Governor’s proclamation is filed with the Secretary of State and publicly posted on the Governor’s and Governor’s Office of Emergency Services’ (OES) websites. (CESA establishes OES as the state entity responsible for overseeing the state’s response to emergencies.)

Governor Has Various Emergency Authorities Following Proclamation of State of Emergency

CESA Provides Extensive Emergency Authorities. Through CESA, the Legislature has granted the Governor significant authorities to respond to emergencies—effectively delegating some of its core powers to the Governor—to ensure that the state can adequately address emergencies. In particular, CESA allows the Governor to:

- Suspend any regulatory statute, or statute prescribing the procedure for conduct of state business, or the orders, rules, or regulations of any state agency, where the Governor determines that strict compliance with them would in any way prevent, hinder, or delay addressing the emergency.

- Have complete authority over all agencies of the state government and the right to exercise all police power in responding to the emergency. Courts have interpreted this to mean that the Governor may temporarily make or amend statute to respond to an emergency.

- Spend any available funds—including General Fund resources—to respond to an emergency. When redirecting special funds dedicated for a specific purpose, state law requires that the funds be repaid. However, no specific deadline for repayment is specified. (Additionally, some emergency‑related spending may occur without an emergency declaration, as described in the nearby box.)

- Use state department personnel, property, equipment, and appropriations to respond to an emergency, even if originally intended for other purposes.

- Commandeer or utilize generally any private property deemed necessary in carrying out the responsibilities vested in the Governor as Chief Executive of the state. In these situations, the state pays the reasonable value to the owners. Statute does not specify a deadline for the state to repay the owners.

Some Emergency‑Related Spending Can Occur Without an Emergency Declaration

Some funds for emergency‑related activities are included in the annual budgets of departments tasked with responding to emergencies, such as the Governor’s Office of Emergency Services and the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection (CalFire). These funds can be used without an emergency declaration as they are made available by the Legislature exercising its constitutional appropriation power through the normal budget process. For example, CalFire’s wildfire protection budget includes the Emergency Fund (E‑Fund). The E‑fund is an amount budgeted for emergency fire protection and is intended to enable the department to pay for the costs of responding to large wildfires. (For more on this and our recommendations for improving legislative oversight of the E‑Fund, please see The 2023‑24 Budget: Improving Legislative Oversight of CalFire’s Emergency Fire Protection Budget.)

Authorities Generally Exercised Through Executive Orders. The Governor generally exercises these authorities by issuing executive orders. For example, in March 2023, Governor Newsom issued an executive order waiving statute to ease access to unemployment benefits for people unemployed as a result of severe winter storms that struck the state in February 2023. As mentioned above, these executive orders are often included in the proclamation declaring the emergency though the Governor may also issue them separately. For example, Governor Newsom issued over 20 executive orders related to the January 2025 Southern California wildfires following the initial emergency proclamation for the disaster. CESA requires the Governor to provide “widespread publicity and notice” of orders made during an emergency. This is typically accomplished by posting executive orders to the Governor’s website.

Authorities Remain in Effect Until the Governor or Legislature Terminates the Emergency. CESA requires that the Governor terminate a state of emergency at the earliest possible date that conditions warrant. The Legislature may also terminate a state of emergency by concurrent resolution (a measure that must be approved by both the Senate and Assembly but not the Governor). The authorities granted to the Governor under CESA end only when the state of emergency has been terminated. Similarly, the executive orders the Governor issues during an emergency also generally remain in effect until the emergency has been terminated or the Governor chooses to rescind them earlier.

California Disaster Assistance Act (CDAA) Authorizes Spending From Special Disaster and Emergency Account. CDAA provides a variety of authorities to respond to emergencies. Most notably, the statute authorizes the Department of Finance (DOF) to transfer funds from the Special Fund for Economic Uncertainties (SFEU) to the Disaster Response‑Emergency Operations Account (DREOA) and allocate funds from DREOA to state departments for disaster response operations costs. (The SFEU is the state’s discretionary budget reserve of the General Fund.) Funds are allocated from DREOA immediately upon notification to the Joint Legislative Budget Committee (JLBC) by DOF. Initially, the use of DREOA for each emergency is limited to 120 days following the Governor’s declaration of the emergency. However, the Governor can extend the use of DREOA for emergency‑related activities in 120‑day increments—even if the proclaimed state of emergency has ended. In this way, DREOA funds can be available for response operations that might arise beyond the state of emergency. Notably, these extensions can generally only be made through the end of the fiscal year in which the first 120‑day extension was made. The Legislature established this limit on the use of DREOA on the basis that, if the administration needs to spend funds on an emergency beyond the time allowed, it could seek such funds through the state’s annual budget process. Submitting these requests through the annual budget process ensures that the Legislature retains its core powers and that such expenditures are subject to normal legislative oversight mechanisms.

Emergency Proclamations Allow Governor to Request Federal Assistance. A proclamation of a state of emergency is required for the state to apply for several types of federal assistance. For example, it is a prerequisite for the state to request that the President make a Major Disaster Declaration, which provides opportunities for the state to seek financial assistance through federal government programs. One such program is the Federal Emergency Management Agency’s Public Assistance Program, which typically pays at least 75 percent of eligible state and local government costs in responding to a disaster and repairing public facilities after a disaster.

Governors Have Used Emergency Authorities in Various Ways

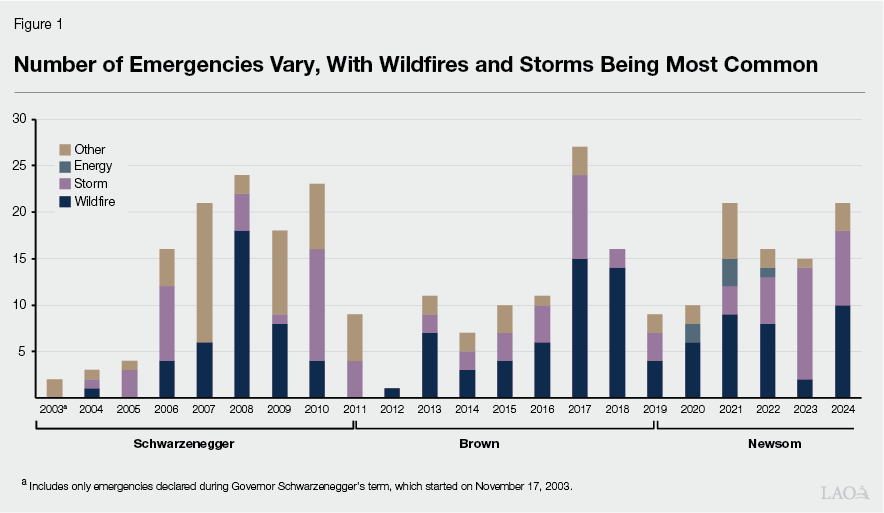

Numerous Emergencies Proclaimed, Mostly for Wildfires and Storms. Based on our review of proclamations published on the Governors’, OES’, and the California State Library’s websites, Governors have proclaimed 295 states of emergency from the beginning of Governor Schwarzenegger’s term in November 2003 through December 2024, as shown in Figure 1.

By type, wildfires and storms made up the majority of these proclamations. Of the 295 emergencies, wildfires represented 130 (44 percent) while storms represented 86 (29 percent) as shown in Figure 1. The remaining include 11 droughts (4 percent), 9 earthquakes (3 percent), and 6 energy and 6 health emergencies (2 percent each), as well as 5 freeze and 5 wind‑related emergencies (2 percent each). The remaining 37 (13 percent) consisted of other types of emergencies, including those related to oil spills, snow melts, gas leaks, and tsunamis.

States of Emergency Are Proclaimed Before and After Events. Some states of emergency are proclaimed to authorize response activities before an event takes place. For example, in August 2023, the Governor proclaimed a state of emergency in advance of Hurricane Hilary’s projected landfall in Southern California. This allowed the Governor to mobilize and coordinate resources ahead of the storm’s forecasted impacts. Emergencies have also been proclaimed after events causing the emergency conditions have passed. This can happen within a couple of weeks of the emergency event, but also after significant time has passed. For example, the Alisal Fire started on October 11, 2021, and continued until November 20, 2021. However, the Governor proclaimed a state of emergency related to the fire on July 1, 2022—over seven months after the wildfire ended. A delay in the proclamation of an emergency can be due to the fact that the extent of damage might not be fully known until time has passed from the disaster or it can take time for the costs of a disaster to accumulate to a point where an emergency declaration is necessary.

Certain Types of Authorities Are Frequently Used During Emergencies… Some types of emergency response activities taken with CESA and CDAA authorities occur relatively frequently. For example, after wildfires and storms, Governors often use CESA authorities to issue executive orders (1) requiring state agencies to use their resources to respond as directed by OES; (2) requiring state agencies to take specific actions, such as directing the California Department of Transportation to request federal assistance for highway repairs and reconstruction; (3) suspending statutes related to contracting to allow state agencies to procure necessary supplies and services; and (4) suspending certain statutes to ease access to unemployment benefits for those unemployed as a result of the disaster. In addition, the Governor often uses the authority in CDAA to direct DOF to allocate funds from DREOA for emergency response activities, including hazardous debris removal or the procurement of goods, such as trailers, to assist with wildfire response efforts.

…But Wider Range of Authorities Have Been Used in Some Instances. For emergencies that are novel or occur less frequently, Governors have used emergency authorities to take a much wider range of actions. For example, CESA authorities have been used to issue executive orders:

- Requiring the public—except for those working in critical infrastructure sectors—to stay at home to reduce the spread of the virus during the COVID‑19 pandemic.

- Redirecting state employees—also during the COVID‑19 pandemic—to “contact tracing” activities, which involves conducting case investigations and notifying people who may have been exposed to the virus of the need to quarantine.

- Requiring the California Department of Public Health to assist the San Bernardino County Division of Environmental Health Services (SBDEHS) until the division could attain normal staffing levels following a 2015 terrorist attack on a training session involving 80 SBDEHS employees.

- Requiring all state agencies with expertise in the removal of highly explosive materials to assist local law enforcement with responding to the discovery of an illegal bomb making operation in a house in Escondido in 2010.

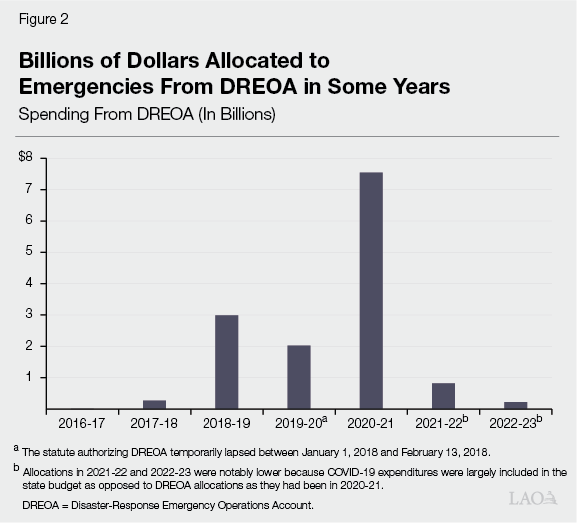

Significant Resources Spent on Emergency Response. Since 2016‑17, Governors have generally allocated hundreds of millions to billions of dollars each year to state departments from DREOA for various emergencies. As shown in Figure 2, allocations were notably higher from 2018‑19 to 2021‑22 due to extreme wildfire seasons and the COVID‑19 pandemic. It is important to note that allocations are sometimes based on cost estimates—rather than actual costs incurred—for performing the emergency response activities. Accordingly, not all of the funds allocated to departments might be expended, as we discuss later.

Many Proclamations Stay Open for at Least a Few Years. A total of 242 of the 295 states of emergency proclaimed between the beginning of Governor Schwarzenegger’s term in November 2003 through December 2024 had been terminated by the end of 2024. These terminated emergencies remained open for an average of about three and a half years. The remaining 53 states of emergency declared since October 30, 2015 that were still open on December 31, 2024 had been open for an average of about two years—ranging from a couple weeks to over nine years. (No states of emergency declared before October 30, 2015 are still open.) Governors choose to keep states of emergency open for various reasons, such as ongoing recovery efforts or the continued need for certain authorities to respond to an emergency. For example, multiple drought states of emergency proclaimed in 2021 remained open into 2024 because the administration indicated that certain areas were still experiencing groundwater supply shortages and domestic well failures.

Emergency Laws Sometimes Cede Core Legislative Powers Unnecessarily and Lack Adequate Oversight

When considering emergency authorities granted to the Governor, the Legislature has the difficult task of balancing two key goals: (1) providing enough flexibility for the Governor to respond effectively and swiftly during emergencies and (2) maintaining and exercising the Legislature’s core constitutional powers. Overall, we find that the current emergency laws lean more heavily toward flexibility than necessary in some cases. This is particularly concerning given that there are often inadequate mechanisms in place to allow the Legislature to effectively conduct oversight of the Governor’s use of emergency authorities. Below, we identify key instances where the existing emergency laws cede a substantial amount of the Legislature’s core powers to the Governor and contain relatively limited oversight mechanisms to ensure the Governor is using this authority consistent with legislative intent and priorities. We also highlight a couple of examples where Governors have used these authorities in ways that were potentially inconsistent with legislative priorities and/or with very little legislative input and oversight. It is important to note, however, that our primary focus is not on how Governors have used these authorities to date. Rather, we are more concerned that, without action by the Legislature to establish a process for better maintaining its core powers and ensuring adequate oversight, future Governors could choose to use emergency authorities in more concerning ways.

Governor Can Bypass the Legislative Process Unnecessarily

Under CESA, the Governor determines when a state of emergency exists and, as a result, determines when typical legislative budget and policy processes do not need to be followed. Such a structure allows Governors to proclaim states of emergency even in cases where, arguably, normal budget and policy processes could have been used. For example, in March 2019, Governor Newsom proclaimed a state of emergency to implement 35 forest management projects that were intended to reduce the risk of wildfire through activities such as removing hazardous dead trees and clearing vegetation. The California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection (CalFire) had been undertaking forest management projects for a number of years beforehand, using normal processes to do so. However, the state of emergency proclamation authorized the Secretary of the Natural Resources Agency and the Secretary of the California Environmental Protection Agency to suspend state environmental permitting requirements in order for CalFire to implement the 35 projects immediately. Moreover, the state of emergency suspended certain requirements for licensing and procurement. Although this allowed the administration to expedite the completion of these priority projects, the state of emergency was not addressing an active emergency event and it is reasonable to think that the Governor could have instead used existing budget or policy processes to preserve a role for the Legislature. For example, the Governor could have used legislation with an urgency clause to obtain the suspensions he was seeking. Declaring an emergency instead precluded the Legislature from providing input on the proposed projects and whether they warranted suspending state law and regulations.

No Process to Ensure Authority Is Promptly Restored to Legislature

Legislature Cedes Authority Longer Than Necessary. CESA requires the Governor to terminate a state of emergency at the earliest possible date that conditions warrant. However, it does not establish a formal process for the Governor and/or Legislature to assess whether a state of emergency—and all of the associated authorities granted to the Governor—should remain in effect. This means there is no formal process for the Legislature to regain its authority, short of ending the entire emergency through concurrent resolution. Officials under the current administration stated that they have established a process for regularly reviewing ongoing states of emergency. Through this process, they coordinate with state, regional, and local officials to confirm whether the authorities under an ongoing state of emergency are still needed. This appears to be a reasonable starting point for reviewing the ongoing need for emergencies, but it has a couple of key limitations. First, this process does not include a systematic way to keep the Legislature informed of the ongoing need for states of emergency or a clear opportunity for the Legislature to weigh in on whether the administration still needs the emergency authorities. Second, it appears that the requirement to terminate emergencies at the earliest possible date is not always adhered to. This is demonstrated by the fact that Governors have often terminated states of emergency in batches. For example:

- On March 10, 2005, Governor Schwarzenegger terminated 17 emergencies dating back to December 1998. All but two had been proclaimed under previous administrations but had not been terminated.

- On May 18, 2011, Governor Brown terminated 103 states of emergency dating back to June 2004. All of these states of emergency were proclaimed under the previous administration but had not been terminated.

- On December 23, 2019, Governor Newsom terminated 61 states of emergency dating back to January 2011. All of these states of emergency were proclaimed under the previous administration but had not been terminated.

- On February 25, 2022, Governor Newsom terminated 11 states of emergency that had been proclaimed between 2015 and 2021.

We find it unlikely that numerous emergencies were all resolved on the same day, meaning that at least some of the states of emergency terminated in batches should have been terminated at an earlier date. The lack of a required process for reviewing or renewing the continuing need for states of emergency in CESA enables the Governor to retain some of the Legislature’s core powers beyond the time that conditions warrant contrary to the legislative intent expressed in CESA.

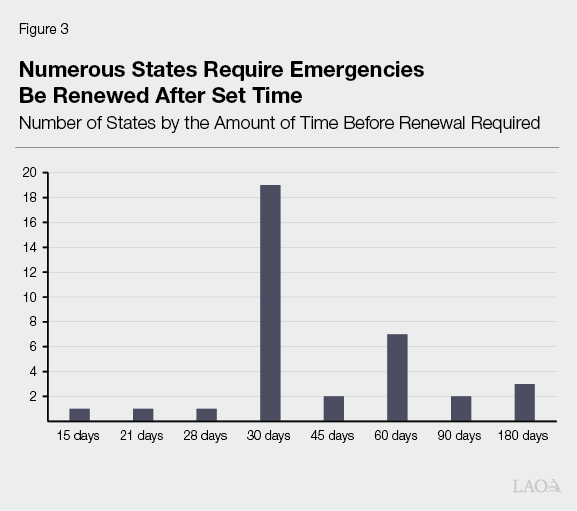

Requirement to Review or Renew Emergencies Exist in Numerous Jurisdictions. The lack of a review or renewal requirement stands in contrast to state law as it applies to local emergencies in California. Specifically, when a local emergency is declared by a city, county, or city/county governing body, CESA requires the emergency to be reviewed every 60 days by the governing body until the local emergency is terminated. Moreover, compared to other states, California is an outlier by not requiring states of emergency to expire unless renewed. Specifically, 36 states limit the amount of time states of emergency can be open before the Governor or Legislature must act to renew them—ranging from 15 days to six months. For example, Florida state law requires a state of emergency to expire after 60 days unless renewed by the Governor. Figure 3 shows the distribution of the 36 states by the amount of time in which their Governors or Legislatures must act.

At the federal level, the National Emergencies Act (NEA) was enacted in 1976 to rein in presidential emergency powers and provides that a national emergency will end automatically after one year unless the President publishes a notice of renewal in the Federal Register. (The Federal Register is the official daily publication for rules, proposed rules, and notices of federal agencies and organizations, as well as executive orders and other presidential documents.) The NEA also allows a national emergency to be ended upon a presidential declaration terminating the emergency or if Congress enacts a joint resolution terminating the emergency.

Limited Role for Legislature in Ongoing States of Emergency

CESA Only Allows Legislature to Terminate Entire Emergency. Although CESA allows the Legislature to terminate an entire state of emergency by concurrent resolution, it does not create a formal process whereby the Legislature can raise objections to or terminate specific parts of the Governor’s use of emergency authorities. As a result, in the event that the Legislature agrees with the need for the Governor’s proclamation of a state of emergency but disagrees with a specific action or authority, the Legislature must weigh whether to end the entire state of emergency—which could hinder ongoing emergency response and recovery efforts—or continue to allow the Governor to act in ways that are contrary to legislative interests. For example, if the Legislature had concerns with any of the Governor’s actions during the COVID‑19 pandemic—such as how long the stay home order remained in place—its only option would have been to end the emergency. Ending the emergency not only could have prevented the Governor from taking steps the Legislature thought necessary to protect public safety, but also could have prevented the state from qualifying for significant amounts of federal funding. Such a scenario illustrates how the current structure makes it difficult for the Legislature to exercise oversight of the Governor’s use of authority during emergencies.

CDAA Does Not Provide for Legislative Oversight Before Funds Are Allocated. Similarly, as noted above, DOF is only required to notify JLBC at the time of allocating funds from DREOA and sometimes the information provided is limited. Accordingly, the Legislature does not have an opportunity to review and provide oversight of a substantial level of emergency response expenditures before funds are allocated to individual departments. For example, in July 2021, Governor Newsom proclaimed a state of emergency to address energy supply and demand issues during extreme heat events that were resulting in immediate and projected energy shortfalls in the summers of 2021 and 2022. In particular, the proclamation directed the Department of Water Resources (DWR) and the California Energy Commission to procure materials, goods, and services necessary for energy generation projects to be online by October 31, 2021. In response, DWR procured four gas generators through a $171.5 million allocation from DREOA in August 2021. This action prevented the Legislature from weighing in on the procurement of the generators when it appears that there was interest in doing so. Specifically, the Chair of the JLBC noted in a January 24, 2022 letter to the administration that the use of DREOA limited reasonable oversight and that the Legislature never had the opportunity to thoroughly review the expenditure of these funds. Moreover, the Chair went on to note that it was unprecedented for the state to purchase large natural gas generators to address statewide emergency demands and that doing so was an inefficient use of state funds and should not be repeated. However, because of the authority ceded to the Governor through CDAA, the Legislature had no clear opportunity to weigh in before the generators were purchased.

Legislatures in Other States Have Greater Oversight of Ongoing Emergencies. Utah’s emergency statute requires the Governor to report certain suspensions and modifications of statute to its Legislative Management Committee, which then may recommend that the Governor (1) continue the suspensions or modifications, (2) terminate them, or (3) call a special session of the Legislature to review and approve or reject them. Moreover, during certain states of emergency that last longer than 30 days, the Utah Governor generally must notify the Legislative Emergency Response Committee at least 24 hours before issuing an executive action. In addition, in Florida, statute allows the Legislature to terminate any specific order, proclamation, or rule under a state of emergency at any time by concurrent resolution. Upon such a concurrent resolution, statute requires the Florida Governor to issue an executive order or proclamation consistent with the concurrent resolution. Such mechanisms allow these legislatures to provide input into ongoing states of emergency while also maintaining some of the flexibilities that their Governors might need to respond.

Limited Requirements to Provide Legislature With Information on Use of Emergency Authorities

CESA Has Few Requirements to Provide Information. Under CESA, the Governor is required to provide “widespread publicity and notice” of orders made during an emergency. However, there are no requirements that the Governor provide the Legislature with specific types of information and at predetermined time intervals. As a result, in previous years, the amount of information provided directly to the Legislature on the Governor’s emergency response activities has varied. At times, the administration has established a process for updating the Legislature with information on such activities during ongoing states of emergency. For example, during the COVID‑19 pandemic, the administration set up regular meetings with the Legislature to provide updates on emergency response activities, such as the availability of personal protective equipment and various executive orders that had been issued. Similarly, the administration regularly briefed the Legislature on its response to the January 2025 Southern California wildfires. However, this process has not been consistently established for other states of emergency. Moreover, establishing such a process is not required by CESA, thus other Governors would not be bound to such a practice in the future.

CDAA Has Only Limited Information Requirements. Under CDAA, funds are allocated from DREOA immediately upon notification of JLBC by DOF. However, there is no requirement on the type of information that must be included in the notification. As a result, notifications have often included very little information. For example, in a May 4, 2017 letter to JLBC, DOF indicated that the California Military Department required $1.6 million from DREOA for “unexpected equipment and personnel costs” stemming from emergencies declared related to rainstorms and the damaged spillway of the Lake Oroville dam. Basic information—such as how much was needed to respond to each emergency as well as what equipment and personnel were needed and why—was not provided with the notification. Moreover, CDAA does not require any subsequent update on the actual expenditure of DREOA funds, which further limits legislative oversight. For example, in the 2024‑25 budget, the administration reverted $1.7 billion from DREOA transfers dating back to 2018‑19 that had not been spent by departments. The administration explained that this largely resulted from overestimating the California Department of Resources Recycling and Recovery’s costs for removing debris caused by wildfires. Had it not been for this reversion, the Legislature likely would not have known that $1.7 billion went unused. The lack of information on actual use of the funds is particularly concerning given how little information is provided on their planned use. This makes it difficult for the Legislature to conduct oversight of the Governor’s use of emergency spending authorities.

Providing Enhanced Information Does Not Appear to Have Impeded Past Response Efforts. One potential reason for not requiring the administration to provide more information to the Legislature is that meeting such requirements could require diverting state resources from important emergency response activities. However, we do not see any evidence that additional information requirements adopted during certain past emergencies have had a major effect on response efforts. For example, as mentioned above, the administration voluntarily provided more information than currently required on its COVID‑19 and January 2025 Southern California wildfire response efforts. Moreover, under legislation that applied specifically to the wildfires, the administration was required to provide much more detailed spending information than otherwise. Neither the voluntary nor mandated provision of additional information to the Legislature by the administration appears to have impeded its response efforts in these cases.

Lack of Such Information Requirements Contrasts With Federal and Some States’ Statutes. Federal statute requires the President to provide Congress with information related to declared emergencies, which can enhance congressional oversight. Specifically, the NEA provides mechanisms for enhanced congressional oversight of national emergency declarations. In particular, the NEA requires the President to:

- Specify which statutory emergency authorities the President intends to invoke upon a declaration of a national emergency.

- Maintain records and transmit to Congress all rules and regulations promulgated to carry out such authorities.

- Provide an accounting of expenditures directly attributable to the exercise of such authorities for every six‑month period following the declaration.

Some other states also have specific requirements for the provision of information to their state legislatures during an emergency. For example, under Colorado law, the Governor must provide information “of a comprehensive nature” about an ongoing emergency to certain legislative committees and respond to questions from committee members about the emergency. Additionally, under Kentucky law, the Governor is required to provide the Kentucky Legislature specific expenditure information—such as all contracts issued and federal funds received during the emergency—every 30 days following the declaration of an emergency.

Governor’s Emergency Spending Authority Lacks Oversight Mechanisms

As we noted in our report, The 2021‑22 Budget: Improving Legislative Oversight of Emergency Spending Authorities, the Governor’s emergency spending authorities are extremely broad and allow the Governor to spend an essentially unlimited amount of funds on emergency‑related activities with very little opportunity for the Legislature to provide effective oversight. For example, CESA spending authorities have no legislative notification or reporting requirements. As such, the Governor could—without any legislative action or oversight—reallocate to emergency response activities any legally available funds in the state treasury as well as any available state employees and resources during a state of emergency. If such a redirection took place on a large enough scale, it could have serious consequences, such as undermining the structure and condition of the state budget. This is a considerable unilateral authority for the Governor to wield without any meaningful oversight mechanisms.

Recommendations

Below, we outline some steps the Legislature could take that would help it exercise some of its core powers and ensure adequate oversight, while still preserving considerable flexibility for the state during emergencies. (The Legislature could, of course, choose to take a different mix of actions depending on how it balances these different factors.) In large part, these recommendations focus on ensuring the normal legislative process is used whenever possible and, whenever it is not possible, that there is adequate legislative oversight. One key part of our recommendations is to establish a new two‑step process that would occur after the Governor has declared an emergency. First, after an emergency declaration has been in effect for a set period of time (such as a few months), the Governor would be required to review states of emergency, determine whether they need to continue, and submit information to the Legislature on the activities conducted. Second, after a somewhat longer period of time (such as one year or more), the Governor’s emergency authorities would automatically expire and the normal legislative budget and policy processes would be used to authorize any remaining activities needed for response or recovery, unless a waiver is granted by the Legislature. This process is summarized in Figure 4. We discuss this process, as well as our other recommendations, in more detail below.

Adopt Statute Specifying Governor Should Not Use Emergency Authorities When Existing Processes Suffice. We recommend the Legislature modify statute to specify that the Governor may not use emergency authorities in cases where normal budget and policy processes can be used without negatively affecting response and recovery activities. For example, the Legislature could modify statute to explicitly state that the authorities granted in CESA and CDAA do not provide an alternative budget or policy process and that, whenever possible, proposals should be considered through the annual state budget or other state legislation. This would minimize the extent to which the Legislature must cede its core powers to the Governor, including in time periods when states of emergency are in place. For example, if seeking funds for specific emergency activities through the budget process would not interfere with response or recovery efforts, the Governor would be required to do so.

Require States of Emergency to Expire Unless Renewed by Governor at Specified Time Periods. We recommend the Legislature revise CESA to establish a time period after which states of emergency expire unless renewed by the Governor. This would require the Governor to review states of emergency—and the corresponding executive orders that are being used—to determine whether they need to remain in effect. After review, the Governor would then be required to renew states of emergency that are deemed necessary. As part of the renewal, the Governor would be required to identify which executive orders are still needed. Any executive orders not identified as necessary would automatically expire. Going forward, any new executive orders that are needed could only be issued after advanced notification is provided to the Legislature, unless the Legislature waives this requirement. This would maintain the Governor’s flexibility to continue to utilize states of emergency that need to remain in effect, but would create an accountability mechanism that ensures that the Governor revisits the need for states of emergency and related executive orders in a timely manner. It would also provide greater legislative oversight of the Governor’s use of executive orders. The specific time period for renewal, which should ideally occur after initial response efforts are largely complete, could be set in different ways, such as:

- Renewing Each State of Emergency Separately at Specific Intervals. The Legislature could require that the Governor renew each state of emergency separately at specific intervals of time, such as every 30 to 120 days, until the emergency is terminated. Alternatively, the Legislature could require that the Governor renew each state of emergency initially after a period of time, such as 30 to 120 days, with the initial renewal being required to specify when the state of emergency will be terminated or reviewed again.

- Renewing All Ongoing States of Emergency Simultaneously at Set Times Each Year. The Legislature could instead require that the Governor renew all ongoing states of emergency simultaneously at set times of the year. For example, the Legislature could require that the Governor review and renew all ongoing states of emergency that have been open for more than 60 days in January and July of each year.

The Legislature could consult with the Governor’s office, OES, local governments, and other practitioners and experts to determine a reasonable time period and approach for renewing states of emergency.

Require the Administration to Provide Certain Information Prior to Renewal. We recommend that the review and renewal process identified above be structured in a way that enhances legislative oversight of the Governor’s use of emergency authorities. Specifically, we recommend the Legislature require the Governor to provide advance notification prior to renewal that includes, at a minimum, the following information: (1) a description of how emergency authorities and executive orders were used to address the emergency to date, (2) an assessment of the conditions that warrant keeping the emergency open, (3) which executive orders are still needed to respond to the emergency and what actions the Governor expects to take, (4) why the Governor needs to use those executive orders (rather than normal budget and policy processes) to undertake response and recovery activities, (5) specific conditions that need to be satisfied to terminate the state of emergency, and (6) anticipated dates for termination. The notifications should be provided to JLBC and the legislative committees whose jurisdictions include emergency response: The Assembly Committee on Emergency Management, the Senate Governmental Organization Committee, and the Joint Legislative Committee on Emergency Management. The amount of advanced notification could vary depending on the time periods and approach for the renewal process we recommend above. A shorter notification time frame, such as 72 hours to a week, could be used for a shorter renewal period or for individual emergencies. A longer notification time frame, such as 30 days, for a longer renewal period or for numerous emergencies. This time period would allow these legislative committees to raise concerns with the Governor’s plans identified in the report. For example, the committees could raise concerns with the need for particular executive orders. Similar to other existing legislative notification processes, Governors could choose to ignore these concerns, but seldom have in similar circumstances in the past.

Create Sunset for States of Emergency That Are Open for an Extended Period of Time. We recommend that the Legislature establish an automatic sunset period for states of emergency after an extended period of time. This would create a mechanism to ensure any authority needed to continue emergency response activities over an extended period of time would go through the normal legislative budget and policy processes. For example, the Legislature could consider modeling such guidelines after CDAA’s limitation on the use of DREOA funds generally through the end of the fiscal year in which the first 120‑day extension was made. When applying this model to the Governor’s use of emergency authorities, the Legislature could revise CESA to sunset states of emergency at the end of the fiscal year after which the state of emergency is proclaimed. Over this period of time, response and recovery efforts would likely be more well defined, and this process would ensure that ongoing actions are subject to legislative review and approval. The Legislature could consult with the Governor’s office, OES, and other emergency experts and practitioners to ensure that any such requirements would not affect emergency response and recovery activities and to identify a time frame that is generally sufficient for such activities to be more well defined. This would ensure normal budget and policy processes are used again as soon as possible. We note that normal budget and policy processes have been used to respond to ongoing emergencies previously. For example, rather than continuing to use emergency spending authorities, Governor Newsom submitted many proposals for COVID‑19‑related emergency response spending to the Legislature for consideration during the 2021‑22 budget process. Similarly, initial funding for responding to the January 2025 Southern California wildfires was approved through normal budget and policy processes. These actions allowed the Legislature to exercise its core powers and provided it much greater oversight of these proposals

Allow for Waiver of Sunset in Certain Circumstances. For particularly complex and extended states of emergency where conditions are constantly changing after an extended period of time, the Legislature could include a statutory provision for the JLBC or the Joint Legislative Committee on Emergency Management to waive this sunset requirement for a set amount of time so that the Governor can continue to use emergency authorities until response and recovery activities are more well defined. Additionally, such waivers could be used to facilitate the receipt of federal funds in cases were response and recovery efforts are particularly extended.

Require the Administration to Submit a Report After Emergency Expires. We recommend the Legislature require the administration to submit a report to the Legislature after each emergency ends. This would enhance legislative oversight by providing the Legislature with more information about how the Governor used emergency authorities. The Legislature could require the reports to include, at a minimum, the conditions that warranted ending the emergency and the amount of actual expenditures, including state spending and federal reimbursements. The Legislature could also consider requiring other types of information be included that would be helpful for informing approaches to future states of emergency, such as any lessons learned from the emergency activities. We note that this requirement is similar to an already existing requirement that OES complete ‘after‑action reports’ within 180 days after each declared disaster and provide such reports to interested public safety and emergency management organizations. Accordingly, the new report we recommend would likely not represent a significant increase in workload. Rather, it would build on existing reports to enhance the amount of information provided directly to the Legislature.

Reform Emergency Spending Authorities to Enhance Legislative Oversight. The above changes would be enhanced by the Legislature also implementing the recommendations from our 2021 report on the Governor’s emergency spending authorities. Specifically, we recommended (1) requiring all emergency augmentations come from DREOA, (2) establishing an amount for DREOA in the budget, (3) requiring advanced notice to transfer additional funds into DREOA, and (4) requiring reporting on planned and actual emergency expenditures. (We provide more detail on these recommendations in the nearby box.) Implementing these recommendations will provide the Legislature with greater oversight of state spending during emergencies and minimize the extent to which it must cede its core spending powers. We also note that some of these recommendations could be incorporated into the review and renewal process that we recommend above. For example, the Legislature could require the administration to include information on planned and actual emergency expenditures in the renewal reports submitted to the Legislature.

Improving Legislative Oversight of Emergency Spending Authorities

In our report, the 2021‑22 Budget: Improving Legislative Oversight of Emergency Spending Authorities, we recommended that the Legislature make fundamental changes to the Governor’s overall emergency spending authorities, as outlined below.

Require All Emergency Augmentations Come From the Disaster‑Response Emergency Operations Account (DREOA). In order to ensure that emergency spending augmentations authorized under the California Emergency Services Act (CESA) and DREOA are tracked and follow the same requirements for legislative notification and reporting, we recommended that the Legislature require all emergency augmentations come from DREOA. Under this recommendation, the Governor could still redirect any legally available state funds to emergency response‑related activities through CESA. However, these funds would first have to be deposited into DREOA. (We recommended additional oversight mechanisms for the Governor’s authority to transfer funds into DREOA below.) Having all emergency augmentations coming from the same account would ensure that a consistent process governs all emergency augmentations.

Establish an Amount for DREOA in the Budget. In order to (1) ensure that the Governor can access a reasonable amount of funding for emergencies, (2) give the Legislature input into the level of funding available for emergency expenditures, and (3) minimize the chance that emergency spending will undermine the state budget structure or condition, we recommended establishing the total initial level of funding authorized each year for emergencies in the state budget. This amount would be budgeted in DREOA with the funds available to the Governor to respond to emergencies. As we discuss below, the Governor would only be authorized to augment departmental budgets from the account by notifying the Legislature when such allocations are made.

Require Advanced Notification to Transfer Additional Funds Into DREOA. In some years, the Governor may need to exceed the amount of emergency funding budgeted in DREOA. In order to maintain this flexibility—while also ensuring the Legislature is involved in spending decisions that could impact the overall structure of the state budget—we recommended that the Legislature require advanced notification before additional funds can be transferred into DREOA, including when funds are deposited into DREOA using CESA authority. The notifications should be provided to the Joint Legislative Budget Committee (JLBC), since most midyear budget changes and current DREOA notifications go through JLBC. The amount of advanced notification and the information provided to the Legislature could vary depending on different factors. For example, the Legislature could:

- Establish Shorter Notification Period for Smaller Transfers Tied to Ongoing Emergencies. Transfers below a specified dollar threshold that are tied to ongoing emergencies and are accompanied by details on how the funds would be spent could have a shorter notification time frame, such as 72 hours. (The dollar threshold could be established in consultation with the administration based on historical emergency spending needs.) This is because such transfers would have less significant budgetary implications. Moreover, the required details on how the funds would be spent allows the Legislature to effectively evaluate the request in a shorter time frame. In addition, given that the emergency would be ongoing in such a circumstance, the need for funds could be urgent.

- Establish Longer Notification Period for Larger Transfers or Transfers Made Proactively Before Emergencies. In other cases, the Governor may want to transfer large sums into DREOA if the balance becomes low or there is a known risk of potential emergencies. In this case, a longer notification period would be warranted, such as 30 or 45 days, to allow the Legislature to conduct more oversight of the transfer and its budgetary implications. For example, the Legislature could hold an oversight hearing within this longer time frame.

- Allow Waiver of Notification Time Frame in Urgent Circumstances. If the Governor found it necessary to transfer funds to respond urgently to protect lives or property, a process could be established to allow the Governor to request a waiver to shorten the time frame specified for advanced notification. For example, the administration could request JLBC to waive the 72‑hour notification time frame mentioned above if there was sufficient urgency, such as to address immediate threats to people or property. If JLBC approved a waiver of the time frame, the administration would be able to transfer the funds immediately, or after a shortened time frame specified by JLBC.

Require Reporting on Planned and Actual Emergency Expenditures. In order to ensure that the Legislature has complete information on emergency spending, we recommended the Legislature require the Department of Finance to provide regular emergency expenditure reports. For each emergency‑related activity, the reports should show, at a minimum, all planned and actual emergency spending by state entities, including expenditure of funds allocated from DREOA, federal funds, and private funds, as well as the expenditure of funds budgeted for emergency response or redirected within departmental budgets to respond to an emergency. This information should include a description of the specific activities funded. This would provide the Legislature—and the public—with the information necessary to conduct oversight of how the Governor spends funds during emergencies.

Provide Additional Funding to Comply With New Requirements. We acknowledge the changes outlined above would create some new workload for the agencies involved in emergency response, such as OES. To ensure these requirements do not negatively impact the state’s ability to respond to and recover from emergencies, we recommend that the Legislature provide additional funding to support this new workload. We estimate the cost of this workload would be unlikely to exceed a few million dollars annually. However, the Legislature could work with the administration to get a more precise estimate of the amount of funding necessary. In our view, the benefits of additional legislative oversight of broad emergency authority outweigh these relatively modest costs.

Conclusion

While the state must have flexibility to respond to emergencies, it is also critical for the Legislature to maintain and exercise its core constitutional powers. This is necessary to maintain the balance of powers fundamental to the structure of California’s constitution, which has been put in place to ensure that one branch of government is not able to exercise its powers at the expense of another. We find that current emergency laws lean more heavily toward flexibility than necessary in some cases. This is particularly concerning given that, under the current structure, the mechanisms in place for the Legislature to conduct oversight of the Governor during emergencies are somewhat limited. Setting aside whether Governors have abused this flexibility or lack of transparency to date, it remains possible that such abuse could occur in the future. Accordingly, we recommend modifying these laws in ways that would better balance the Governor’s need for flexibility with the Legislature’s right to retain its core powers and exercise oversight during and after emergencies.