Background

California Adopted First Credit in Response to Other States’ Actions. The U.S. motion picture industry is heavily concentrated in Los Angeles and New York. As we noted in our 2014 report, about half of the motion picture industry’s jobs located are in and around Los Angeles and these jobs pay relatively high wages. Because most film and television productions can be made almost anywhere, many U.S. states, Canadian provinces, and other foreign governments offer generous financial incentives to attract film and television production to their regions.

A decade ago, film production employment declined in California while increasing in states like Louisiana and New Mexico that had film production incentives. California policy makers believed that the financial incentives offered by other places were causing the state to lose these high-paying jobs. In 2009, the Legislature created a tax credit to reduce production companies’ tax liabilities by up to 25 percent of certain production expenses. Total credits were capped at $100 million annually statewide. The California Film Commission (CFC) allocates and issues the credits to eligible production companies. The Franchise Tax Board (FTB) tracks and verifies when the corporations that own the production companies use the credits to reduce their state taxes. We described and evaluated this program in detail in our September 2016 report, California’s First Film Tax Credit Program.

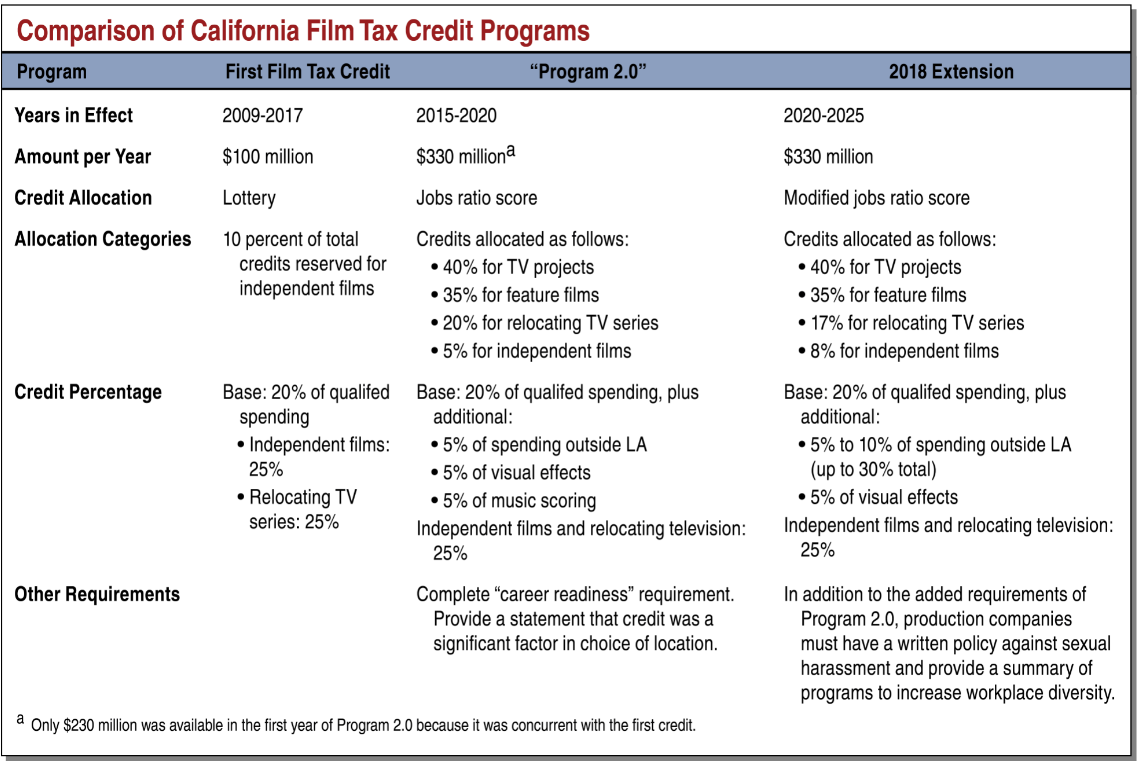

“Program 2.0” Tripled Amount of Film Tax Credits Available. The state’s film tax credit was expanded in 2015 from $100 million to $330 million per year. The new program—which the CFC refers to as Program 2.0—also made significant changes to how credits are allocated and provided an additional 5 percent tax credit for certain kinds of production spending, such as visual effects. The state film tax credit was set to expire in June 2020, but the 2018 budget package extended it for an additional five years and made relatively minor changes to the program. The figure below compares the three iterations of the film tax credit.

Fiscal Update

$617 Million in Credits Issued for First Film Tax Credit. The state had expected to issue a total of $800 million in credits under the first version of the program. Of that amount, the CFC issued a total $617 million in tax credits as of June 2019. This amount is less than expected for several reasons. First, many of the film and television projects allocated credits were never made. Second, other projects allocated credits became ineligible because they were unable to complete production within the required timeframe or because they were filmed in another state. Third, about 70 percent of the production companies actually spent less on qualified expenses than they initially estimated, and therefore were issued a lower credit amount than they were allocated. Unused credits could not be reallocated after the program ended in July 2016.

Some Completed Projects Have Not Yet Received Credits. The amount of credits issued by CFC could rise somewhat over the next several years because there are roughly $50 million outstanding credits allocated—but not issued—under the first program. The CFC has informed us that a handful of production companies have completed their films and television projects but have not yet submitted the paperwork required for CFC to issue their credits. We believe this is because these corporations do not have sufficient state tax liability to use their credits.

First Film Tax Credit Program Has Cost About $500 Million to Date. FTB reports that for taxable years 2011 through 2017, about $440 million in credits have been used to reduce corporation taxes and $2 million to reduce personal income taxes. The credit also can be applied against sales and use taxes, which are administered by the California Department of Tax and Fee Administration (CDTFA). According to CDTFA, credits totaling $53 million have been applied against the sales and use tax through 2017-18. The cost of the first program will continue to increase because production companies have up to five years to use the credits once issued. The total cost of the first film tax credit likely will be between $600 million and $650 million, depending on the amount of credits that expire before they can be used.

Nearly $1.2 Billion Allocated Under Program 2.0. The CFC has been allocating tax credits under the expanded Program 2.0 since July 2015. As noted earlier, Program 2.0 provides up to $330 million in credits per year. Other changes to the program have resulted in the average tax credit allocation being significantly larger—more than $5 million in Program 2.0 compared to about $2 million in the first program. As of April 1, 2019, a total of 200 projects

have been allocated almost $1.2 billion in credits. Of these, roughly one-third of the projects have been issued credit certificates.

Cost to Date of Program 2.0 Is Unclear. FTB is unable to readily capture and report differences between the film tax credit programs. According to FTB, some filers claim a total amount of tax credits on their tax returns and then separately provide supporting documentation. FTB taxpayer compliance staff subsequently verifies tax credit claims with the CFC. Publically reported income tax statistics do not currently differentiate between the different tax credit programs. Consequently, because production companies could be using credits from either the first or second program since 2016, we cannot determine the cost of the second program independently. (Moreover, a portion of the $440 million cost of the first program cited above could be from the second program.)

Effectiveness of Film Production Incentives in Dispute

Prior LAO Comments on Film Credits: Credits are Problematic... In our evaluation of the first film tax credit, we found that the costs exceeded the benefits. While the credit probably caused some film and television projects to be made here, many other similar projects also were made here without receiving any financial incentive. Studying the projects that applied for but did not receive a credit, we concluded that about one-third of the projects receiving a credit probably would have been made here whether or not they received the subsidy. In general, we have long raised concerns about tax provisions that favor a small number of businesses at a real cost to all other businesses.

…But Understandable to Defend a Flagship Industry Targeted by Other States. At the same time, we observed that all of the other leading film production locations—New York, Canada, and the United Kingdom—provide significant subsidies. As such, we wrote that the state’s film tax credits “can be viewed as ways to ‘level the playing field’ and counter financial incentives to locate productions outside of California unrelated to creative considerations.” So, while we expressed concerns about film tax credits, we noted that providing film tax credits was understandable in light of this interjurisdictional tax competition and the state’s economic interest in maintaining the concentration of businesses in this industry in California.

Recent Research Findings Raise Concerns. Since our last report, other independent researchers have studied the effectiveness of public subsidies for film and television production. (See Patrick Button and Michael Thom.) They found that incentives do not help states establish a new local film industry or create lasting economic development. Like our research, these studies confirm production is mobile, susceptible to influence by financial incentives, and that film production subsidies provide some tangible benefits. However, these studies have all concluded that the benefits are small relative to the subsidies’ cost. A notable new finding in this research is that changes in the number of motion picture industry jobs—increases and decreases—are not affected by the existence of a tax incentive in that state or in other states. When the number of jobs in states with an incentive increased, jobs also increased in some states that did not have an active incentive program—such as Florida and Nevada. This suggests that incentives have less effect on film industry jobs than other factors—discussed in our first report—such as the growth of the U.S. economy and technological changes.