The California Film and Television Production Tax Credit (film tax credit) program provides up to $100 million annually to qualifying film and television productions. Since 2009, when the program was adopted, the state has allocated film tax credits using a lottery system because the program has had more eligible applicants than available tax credits. Under current law, the film tax credit program will sunset on July 1, 2017. California lawmakers recently have introduced legislation that would revise key provisions of the program.

Chapter 841, Statutes of 2012 (AB 2026, Fuentes), requires the Legislative Analyst’s Office (LAO) to report on the economic effects and administration of the film tax credit program by January 2016. Given the level of interest in this program among the public and legislators, we prepared this initial report to provide background information on the motion picture industry and to offer preliminary observations regarding the tax credits. In the preparation of this report, we conducted over two dozen interviews with industry experts and reviewed the available research on the economic effects of state subsidies for film and television production. This early report does not make recommendations regarding the film tax credit program or the proposed legislation.

Our next report on the program will review the project–level data that state officials are collecting about film tax credit recipients. We expect to release the report required by Chapter 841 in late 2015.

Production Process

The motion picture industry creates films, television programs, and other motion picture products (such as commercials and music videos) for distribution through various channels—including movie theatres, television broadcasters, and retailers. While every motion picture production is a different undertaking, each usually follows the same process: (1) pre–production, (2) principal photography, and (3) post–production. Some understanding of these phases helps to better understand the industry and certain provisions of the film tax credit.

Hiring Ramps Up During Pre–Production Phase. Pre–production is the process of planning and preparing all of the details of the production. Industry experts advise us that the pre–production phase typically begins with a small staff of about ten individuals. During pre–production, the initial production staff prepare a detailed schedule and budget, finalize the script, determine the filming location (or locations), and negotiate contracts with vendors and suppliers. During pre–production, the initial production staff also hires the core production staff, crew, and cast. The core production staff may exceed 200 people for large–budget films and television programs, although this number varies depending on the needs of the individual production. (Smaller–budget productions typically have a smaller staff.) The core staff generally begins work—designing and building sets and property (props), for example—well in advance of principal photography.

Principal Photography Phase Usually Is Short, but Offers Many Jobs. The cast performances are filmed during the principal photography phase. Employment may increase dramatically for short periods during principal photography depending on the number of additional cast or crew required for individual scenes or episodes. Production spending is highest during principal photography, although budgets and durations of principal photography can vary greatly. While principal photography for a major feature film might continue for several months, a movie made for a basic cable television network typically will be shot over 30–35 days and a single episode for a one–hour television drama typically will be shot over 7–9 days. Many television commercials are filmed in a single day, but some may require a longer period.

Timeline and Employment During Post–Production Phase Are Highly Variable. Post–production is the process of editing and assembling all of the elements of the film, television program, or other production into the finished product. Post–production often begins while principal photography is still in progress. The specific requirements of post–production depend on the project. In addition to editing, the process typically includes sound editing, adding sound effects, adding a musical score, adding visual effects, color correction, and other technical tasks. Following the completion of principal photography, post–production may take a week or many months depending on the length of the project and, more critically, the number and complexity of the added visual effects. Employment levels during this stage are highly variable and significantly depend on the needs of the individual production.

Production Phases Can Overlap or Occur Simultaneously. While the phases of the production processes overlap somewhat for a film or one–time television program, it is more or less a linear process. Episodic television programs, on the other hand, are more complex with writing, planning and preparation, filming, and post–production all occurring on different episodes at the same time.

Workforce and Economic Statistics

About the Data. Much of our description of the film and television production industry below relies on employment, wage, and economic output data reported by state and federal agencies. These statistics have certain limitations that may cause them to be somewhat overstated or understated. We provide more detail in the nearby box. These data limitations are not unique to this report. Every analysis of this industry makes choices about how to address them. Comparisons across various studies and reports are difficult because there is some variation in how they address these data limitations.

Workforce and Economic Data Have Some Limitations

Much of our description of the film and television production industry relies on employment, wage, and economic output data reported by state and federal agencies. In some cases, the available data include businesses that do not produce films or television programs. For example, film libraries may be grouped with film and television post–production companies. Still in other cases, the available data do not include information regarding certain film and television production companies because (1) their primary business activity is in another industry, such as television broadcasting, or (2) they contract with a payroll services company, which serves as the employer of record for the production staff, cast, and crew. Additionally, the wages and output of actors, screenwriters, and directors working on a freelance basis (as opposed to being employees of a motion picture studio) typically are reported under a different industry group that also includes independent artists and writers in other fields, such as novelists and professional speakers.

State agencies derive employment and wage statistics from quarterly reports filed by most employers. In reviewing this data, it is important to note that various factors may cause employment levels and wages to be overstated or understated. Specifically, most of the employment information refers to jobs, not annual full–time equivalent positions. While this likely overstates employment for all industries, the effect is greater for industries with a lot of temporary and part–time employment—such as film and television production. Conversely, as described previously, film and television production jobs are understated because the statistics may not include freelance performers and crew directly employed by payroll services companies.

Wages are summarized in the available data as total annual wages (which may include bonuses, reimbursements, and some other benefits) for each establishment. To arrive at an average annual wage for an industry, total annual wages are divided by total jobs. Annual wages may vary with employee skill levels, hourly wages, and the number of hours worked. For example, film and television production workers may work a lot of overtime in some locations while, in other locations, similar workers may only work part–time. The available data does not provide sufficient information to help us understand whether changes in wages over years and across locations are due to differences in employee skill levels, hourly pay, number of hours worked, or some combination of these factors. However, the wage data clearly provides information on the total amount of wage income earned by the employees working in that industry.

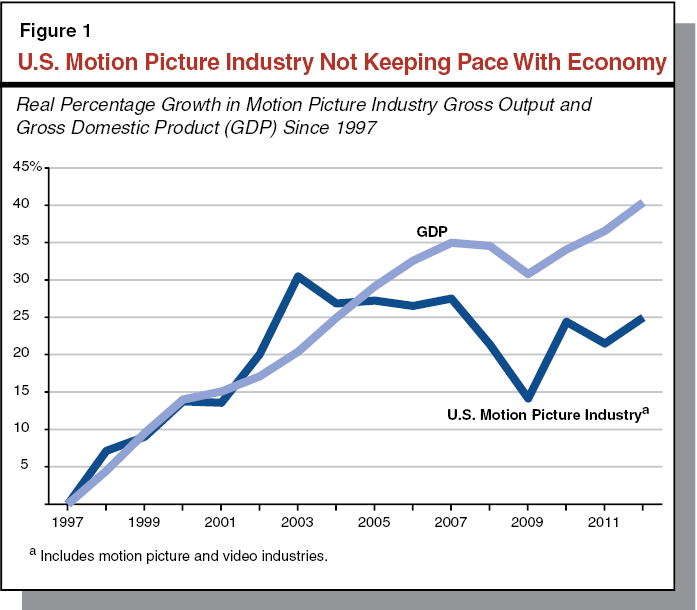

U.S. Motion Picture Industry Appears to Be Growing More Slowly Than Overall Economy. To understand whether the U.S. motion picture industry is making more or fewer products over time, we examined national data on the “gross output” of the “motion picture and video industries.” Gross output represents the total market value of an industry’s production. The gross output of the U.S. motion picture industry was $120 billion in 2012. (This estimate, while reasonable, reflects the data limitations described above. Gross output data is aggregated and, in addition to film and television production and post–production, it includes motion picture distribution and movie theatres.) At $120 billion, the U.S. motion picture industry is larger than, for example, automotive repair and maintenance ($112 billion) and natural gas distribution ($82 billion).

Figure 1 compares inflation–adjusted growth in the gross output of the motion picture industry since 1997 with growth in real gross domestic product. We see that the U.S. motion picture industry generally kept pace with the nation’s economy between 1997 and 2004—with gross output growing by about 3.5 percent annually. Motion picture industry gross output has since leveled off. In real terms, it has declined by an average of 0.2 percent annually between 2004 and 2012. Over the 1997 to 2012 period, the motion picture industry grew at an average annual rate of 1.5 percent, while the overall economy grew at an average annual rate of 2.3 percent.

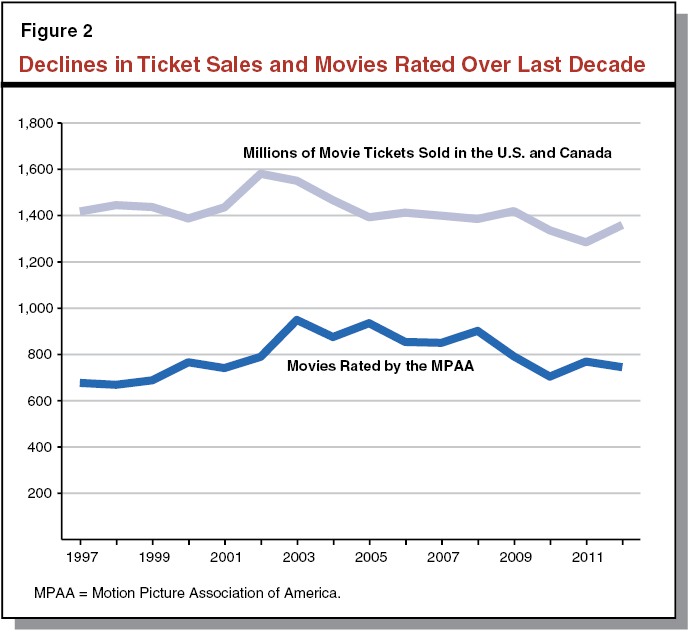

Another Look at Growth in the Motion Picture Industry. Given the data limitations, we looked for other measures of film and television production output—such as the number of movies or television episodes filmed each year. Unfortunately, the production statistics that we are aware of are limited and often self–reported by producers, distributors, or broadcasters. In the case of television production, we were not able to identify a consistently reliable source of output data. In the case of film production, however, we found two metrics that were of sufficient quality to illustrate trends in film output over time: (1) the annual number of movie tickets sold in the U.S. and Canada, and (2) the annual number of films rated by the Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA)—an industry advocacy group. We present this information in Figure 2. Annual movie ticket sales peaked in 2002 with 1.58 billion movie tickets sold in the U.S. and Canada. In 2013, 1.34 billion tickets were sold, a decrease of 16 percent from the peak. The number of films annually submitted to the MPAA for rating (G, PG, PG–13, R, or NC–17) is a good, but imperfect measure of annual film production. (It excludes unrated films and double–counts some films that were resubmitted or that have more than one version.) By this metric, film production appears to have peaked in 2003 with 949 films rated by the MPAA. For comparison, the MPAA annually rated between 700 and 800 films over each of the past five years. While we caution against drawing strong conclusions from these data, the trends indicate that growth in the motion picture industry output may have slowed over the last decade.

Motion Picture Production Employment Growing. Employment statistics provide information on hiring trends in an industry. The federal Bureau of Labor Statistics reports that in 2012, there were 205,000 film and television production jobs and 16,000 film and television post–production jobs in the nation. Film and television production employment has increased since 2001—when the industry supported 173,000 jobs—at an average annual rate of 1.6 percent. Film and television post–production employment has not significantly changed since 2001. Overall, film and television production industry employment since 2001 grew somewhat faster than U.S. employment.

Wage Incomes for Motion Picture Industry Jobs Are High Relative to Other Industries. Wage incomes vary considerably across industries. The relatively high incomes earned by film and television production and post–production employees frequently are cited as a reason for supporting efforts to attract and develop this industry. In 2012, the national average annual wage income in the film and television production industry was $89,000 and was $106,000 in the post–production industry. This compares to average annual wage income of about $49,000 for all private–sector jobs in the U.S. in 2012. The average annual wage income in the film and television production industry has increased from $70,000 in 2001—an increase of about 2.2 percent per year on average. This is slower than the 2.8 percent annual average increase in wage incomes for all private industries. Average annual wage income in the post–production industry increased faster than average, with a rate of about 4 percent per year. There appears to be significant variation in the average annual wage incomes for film and television production employees (and post–production employees) across states. This may reflect differences in employee skill levels, hourly pay, number of hours worked, or some combination of these factors.

Pressures Confronting the Industry

According to industry experts, the U.S. motion picture industry is facing challenges from intellectual property theft, competition from other media, and competition from foreign production locations. The industry is also evolving in significant ways due to globalization and technological change. These pressures and changes may play some role in the industry’s slowing growth in output (discussed above) and the changes in production locations that we discuss later in this report.

Intellectual Property Theft and Competition From Other Media. The MPAA has identified intellectual property theft as a major problem facing the industry. This problem seems to have become more pervasive with widespread access to unauthorized copies of films and television programs on the Internet. In addition, there seems to be an increase in competition for consumers’ attention and disposable income as new types of consumer electronic entertainment devices become available. As the data in Figure 2 show, annual per capita movie ticket sales declined from 5 tickets in 2002 to 3.8 tickets in 2013. It is unclear whether this decline is being offset by an increase in the viewing of films in other ways, such as DVDs, on–demand cable television, and Internet streaming or downloading (legal or illegal). However, one survey reports that Americans are watching more television; in 2012 Americans spent an average of 2.8 hours per day watching television—a 10 percent increase from 2003.

Government Subsidies to Attract Productions. Throughout the history of cinema, films have been made in foreign locations for creative reasons (for example, a film is shot in Paris because the story takes place in that city). Beginning around 1997, however, some productions began to film in Canada because favorable currency exchange rates and labor costs reduced production costs. As economic conditions began to normalize, provincial governments began to offer filmmakers subsidies to enhance the financial incentive to film in Canada instead of the U.S. Now, other governments around the world are offering similar subsidies to attract film and television production. The relocation of production due to subsidies, instead of for creative reasons, is what the industry calls “runaway production.”

Technological Change and Globalization. Industry experts advise us that technological changes have transformed the way films and television programs are made. Digital film editing, digital cameras, three–dimensional projection, extensive digital animation in live action films, and high–definition television have led to significant changes in the industry. Some of these changes have reduced production costs, while other technological changes have increased the complexity and costs of production. In addition, other technological advancements—such as e–mail, smartphones, and video teleconferencing—reduce production costs and allow management to better oversee film and television development over great distances. Industry experts have noted, for example, that the combined forces of technological change and globalization now allow digital animators and post–production staff in multiple locations to collaborate in real time on production and visual effects.

Concentration in Southern California

Historical Home of the Motion Picture Industry. California has a particularly rich history with the motion picture industry. Former Governor Leland Stanford funded the photographic experiments of Eadweard Muybridge that led in 1878 to what some historians consider to be the very first motion picture. Thomas Edison and his employees advanced the early commercial development of the U.S. motion picture industry in New York and New Jersey. Soon afterwards, however, many pioneering filmmakers began to relocate to Southern California in order to take advantage of the better filming conditions and, perhaps, to avoid paying the fees to license Edison’s patents. The community of Hollywood—which merged with the City of Los Angeles in 1910—was a key location for filmmakers. The entire Los Angeles area—often broadly called “Hollywood”—became, and remains to this day, the center of film and television production in the U.S.

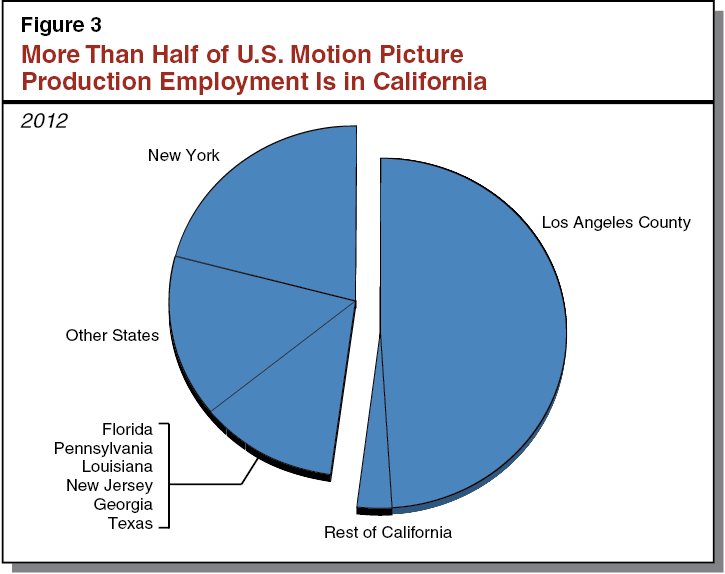

California Has a Large, but Declining Share of U.S. Motion Picture Employment. California had 107,400 film and television production jobs in 2012. This is more than half—52 percent—of the 205,000 industry jobs in the nation. As shown in Figure 3, New York is the only other state with a significant number of film and television production jobs. Florida, Pennsylvania, Louisiana, New Jersey, Georgia, and Texas each account for about 2 percent of U.S. jobs in the industry. California also had 9,600 film and television post–production jobs in 2012, 61 percent of the U.S. total. While California has more than half of the nation’s film and television production jobs, its share of national employment has steadily declined since 2004—when California had about 65 percent of the national film and television production jobs.

Most California Motion Picture Industry Jobs Are in Los Angeles. Film and television production employment is heavily concentrated in Los Angeles County. Of the 107,400 film and television production jobs in California, 100,500—94 percent—are located in Los Angeles County. In addition, about 8,100 film and television post–production jobs are located in Los Angeles County—about 84 percent of the post–production jobs in California. This means that half of all film and television production and post–production jobs in the U.S. are located in a single county.

The motion picture industry is a significant employer in Los Angeles County. The 108,600 combined film and television production and post–production jobs account for nearly 3 percent of all jobs in the county. By employment, the industry is about the same size as the construction sector or about a third as large as the manufacturing sector, which, in Los Angeles County, includes a significant number of jobs related to manufacturing transportation equipment, apparel, fabricated metal products, and computer and electronic products.

Industry Wages in Los Angeles Are Higher Than Elsewhere. As mentioned above, jobs in the motion picture and video industries have relatively high wages. Average annual wage incomes for these industries are higher in Los Angeles County than in New York or the rest of the U.S. It is not clear to us whether this difference in annual wage incomes across the states reflects differences in employee skill levels, hourly pay, number of hours worked, or some combination of these factors. The average annual wage income for a film and television production job in Los Angeles County was $101,000 in 2012—5 percent higher than in New York and 82 percent higher than the rest of the nation. The discrepancy is more pronounced for post–production incomes. The average annual wage income for a post–production job in Los Angeles County was $127,000 in 2012—29 percent higher than in New York and more than twice as much as the average in the rest of the nation.

Additional Jobs in Related Industries. The many businesses that provide the motion picture industry with specialized equipment and services employ many thousands of California residents—mostly in the Los Angeles area. Within Hollywood is an aggregation of thousands of specialized businesses that support the motion picture industry in various ways.

- Vendors and suppliers of specialty motion picture, video, sound, and lighting equipment.

- Vendors and suppliers of specialty production items, such as animal handlers, property (prop) craftsmen, and companies renting trailers.

- Specialty insurance, legal, information technology, and other business services providers.

As this is a somewhat unusual industry, these types of individual suppliers have specialized to meet the industry’s needs. Growth or decline in motion picture production in California will also have an economic effect on these other businesses. Industry experts estimate that one motion picture industry job supports about 2.7 other jobs in the area—suggesting that the industry supports between 250,000 and 300,000 additional jobs in California.

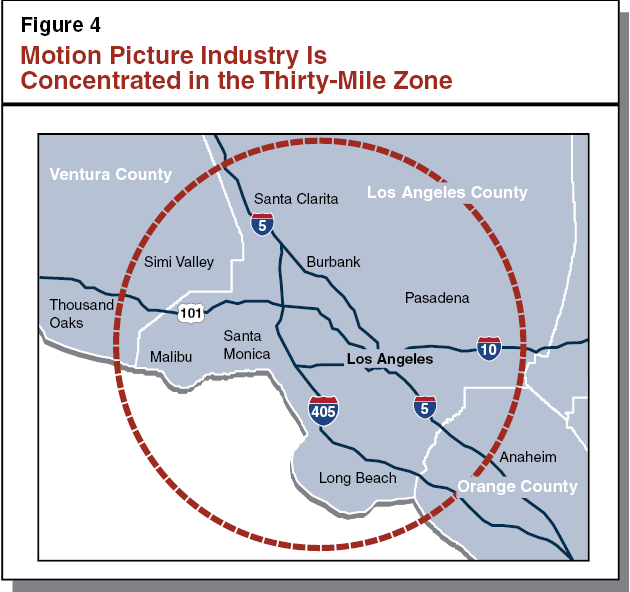

The Thirty–Mile Zone (TMZ). Many film and television production workers are unionized. Historically, collective bargaining agreements have stipulated more favorable work rules and other labor provisions for production work that is located within a 30–mile radius of the intersection of West Beverly Boulevard and North La Cienega Boulevard in Los Angeles. This is one reason that the industry became so heavily concentrated in Los Angeles. Figure 4 shows that most of the TMZ is located in Los Angeles County with some parts of Orange and Ventura counties included.

Some film and television productions located in other countries and other states might have located in California were it not for the subsidies offered by those jurisdictions. (We discuss these subsidy programs in more detail later in the report.) The relocation of motion picture production due to these subsidies—runaway production—has been a major topic in legislative discussions of film tax credits. However, there has been considerable debate about the extent to which this is a problem. As we discuss further below, official wage and employment statistics suggest that California—and Los Angeles County in particular—has a large share of employment and wages in the motion picture and video industries, but that California’s share has declined somewhat.

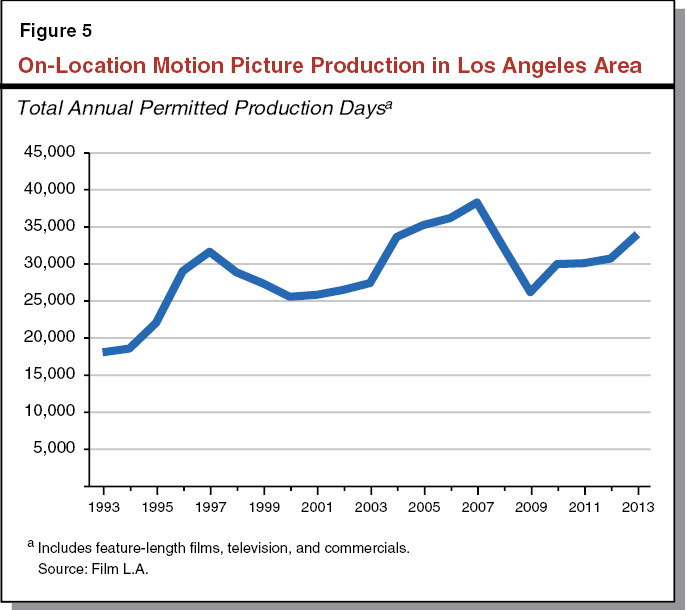

Some Types of Production Appear to Have Increased, While Others Decreased. Los Angeles County and several cities in the Los Angeles metropolitan area contract with a nonprofit company—Film L.A.—to coordinate and process permits for on–location motion picture filming. Film L.A. tracks permitted production days for different types of motion picture production including feature films, television programs, and commercials. Their data, replicated in Figure 5, shows that overall permitted production days have increased by about 90 percent since 1993, but total permitted production days in 2013 remain somewhat below 2005–2007 levels. While not shown in Figure 5, Film L.A.’s data also show that the share of permitted production days for films has declined relative to the share for television and commercials (productions that typically have lower levels of spending and employment than films). In reviewing the Film L.A. data, it is important to note certain limitations. First, some of the changes could be affected due to growth in the number of jurisdictions that contract with Film L.A. to coordinate permitting. In addition, some film and television production in the Los Angeles area is excluded because Film L.A. data do not include unpermitted filming and most filming on soundstages (large, sound–proofed buildings for motion picture production).

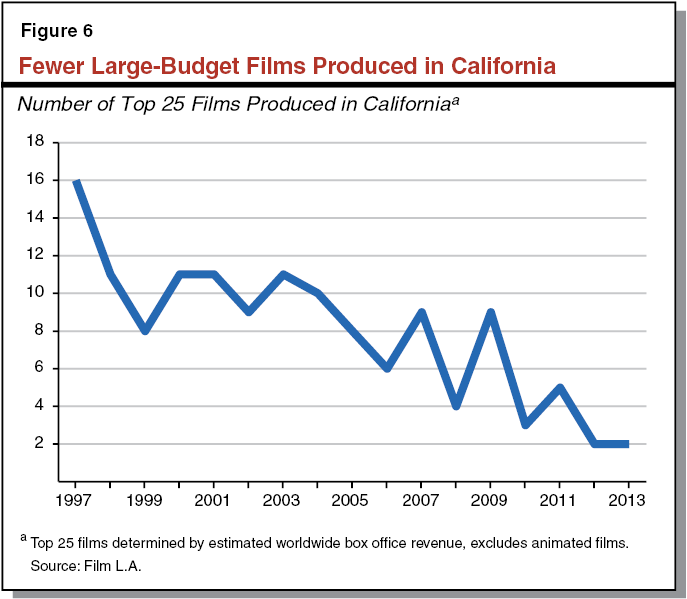

Studies Report Fewer Major Films and Television Drama Programs Made in California. Film L.A. staff and other industry experts assert that there has been a shift in the composition of production from larger budget films and television programs—with more spending and hiring per production day—to smaller budget productions that employ fewer people. Film L.A. observes that, in terms of budget size, the films made in Los Angeles in 1993 were larger than those being made in 2013. While Film L.A. does not track data on production budget or crew size, there have been some attempts to measure these changes. In 2014, Film L.A. and the Los Angeles County Economic Development Corporation (LAEDC) each issued reports measuring the decline in the production of large–budget, feature–length films in California. Film L.A. researched the primary production location of the top 25 live–action feature–length films determined by the highest worldwide box–office. As shown in Figure 6, they found that the number of the top 25 films for which California was the location of principal photography has declined from 16 in 1997 to 2 in 2013. While 1997 may have been an anomalous year—the average number of top 25 films made in California from 1998 to 2004 was 10—the recent negative trend for large–budget films is clear. The LAEDC researched the locations of principal photography for the 41 live action feature–length films released between July 2012 and June 2013 that had an estimated production budget of more than $75 million. Of these, only 2 were made entirely in California and 9 used California as a secondary location. For 30 of these films—or 73 percent—principal photography occurred entirely outside of California.

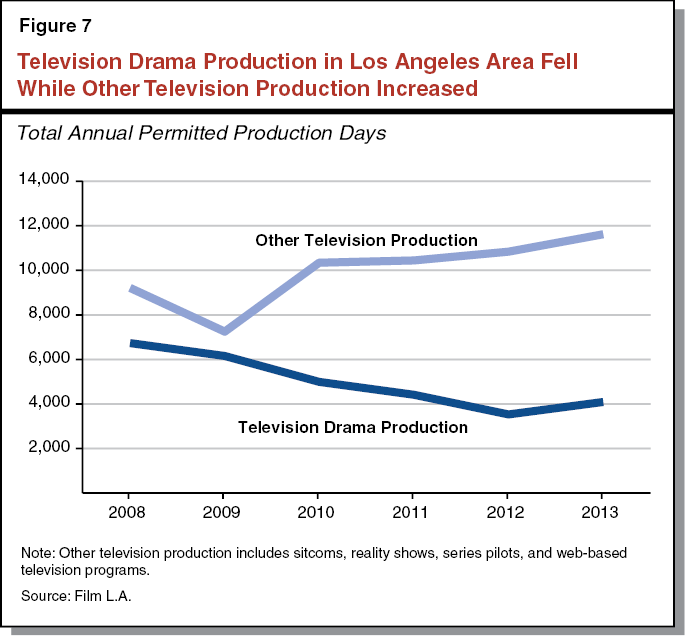

Since 2008, Film L.A. has captured more detailed data on the types of television programs filming on–location in the Los Angeles region than it did previously. Figure 7 shows that television dramas—which typically have larger budgets than other types of television programs—have sharply reduced the number of production days on–location in Los Angeles. Other data collected by the California Film Commission (CFC) show that, in 2012, California had a 34 percent share of all one–hour long television series, down from a 65 percent share in 2005. This decline in certain types of television series was at least partially offset by the production of other types of television programs including basic cable drama series, sitcom series, and reality television series.

In reviewing these data, it is important to note that most of the types of productions that declined—large–budget films and one–hour television series—are not eligible to apply for the state’s tax credit. However, these types of productions typically are the focus of other jurisdictions’ subsidy programs.

There Are Reasons for Concern About Runaway Production. After reviewing all of the available data, we find it difficult to arrive at a strong conclusion regarding the extent to which runaway production has harmed the California motion picture industry. This uncertainty is due to (1) the poor quality of the available data and (2) various other factors affecting the industry. Nonetheless, there are reasons for concern.

The number of film and television production jobs in California declined from a peak of 122,800 in 2004 to the present level of 107,400. (Overall employment in California, in contrast, increased between 2004 and present.) Concurrently, California’s share of national film and television production jobs declined from about 65 percent in 2004 to just over 50 percent in 2012. While total permitted production days have increased over the long–run, there was a significant decline—between the peak in 2007 of 38,300 jobs to 26,200 jobs in 2009—during a period when many states, as we discuss below, were adopting new film and television production subsidies.

States Are Actively Competing for Productions

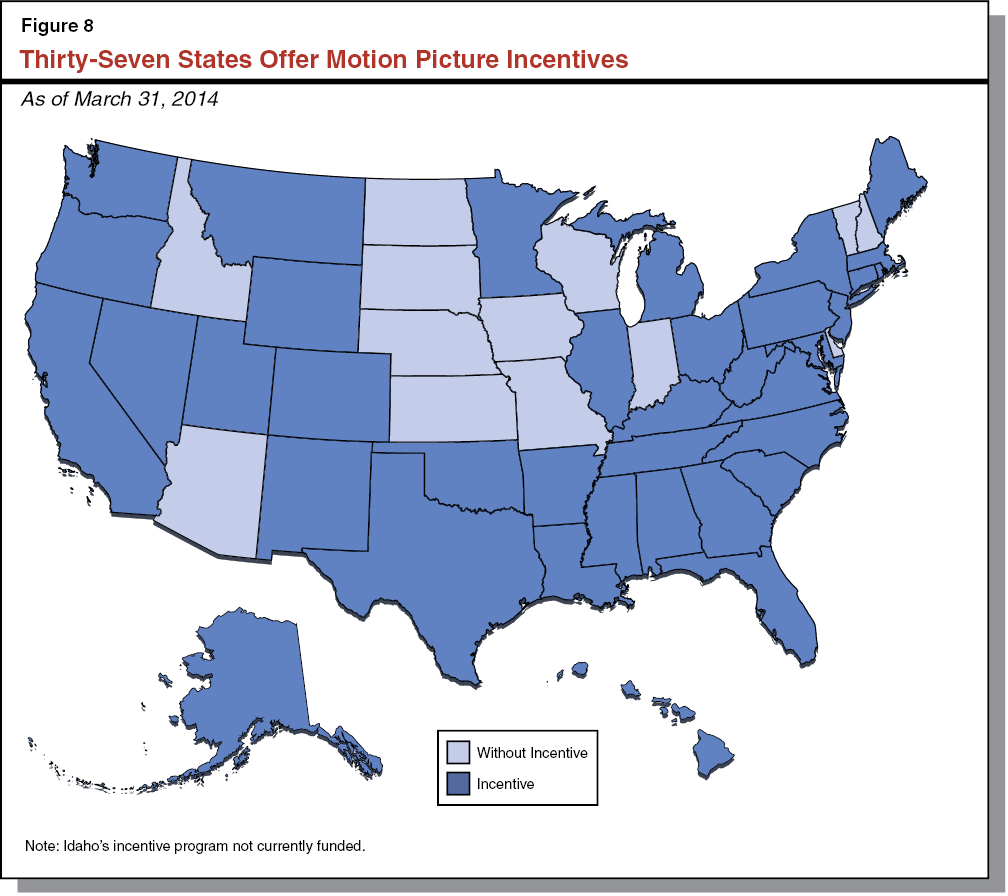

Over the last 15 years, many states have established subsidies intended to encourage the development of local motion picture production industries and to stimulate tourism. We note that some of these subsidy programs were established at the urging of the motion picture industry. As more states have begun to offer these incentives—typically tax credits or cash grants—competition across the states has escalated. Some states, such as Maryland, have expanded their programs. (We describe Maryland’s recent expansion of its tax credit program in the nearby box.) A few other states, such as Arizona and Iowa, have discontinued theirs, choosing not to compete. As shown in Figure 8, 37 states currently offer and fund some sort of film and television production incentive.

Maryland Recently Extended Film and Television Production Subsidy

Maryland, like many states, competes to attract film and television productions. The state offers a refundable income tax credit on qualified production spending and an exemption from the sales tax for production–related purchases made in the state.

During the first two seasons of its production, Maryland provided the one–hour drama series House of Cards a total of $26 million in income tax credits. For the upcoming season, however, Maryland had only $4 million in tax credits available under current law to allocate to the series. Seeking to receive $15 million in tax credits, the show’s producers sent a letter to state officials informing them that filming of the program’s third season would be delayed pending legislative action on the tax credit. In a letter to Maryland’s Governor, the show’s producer wrote:

We know that the General Assembly is in session, and understand legislation must be introduced to increase the program’s funding. . .

In the meantime, I wanted you to be aware that we are required to look at other states in which to film on the off chance that the legislation does not pass, or does not cover the amount of tax credits for which we would qualify. I am sure you can understand that we would not be responsible financiers and a successful production company if we did not have viable options available.

We wanted you to be aware that while we had planned to begin filming in early spring, we have decided to push back the start date for filming until June to ensure there has been a positive outcome of the legislation. In the event sufficient incentives do not become available, we will have to break down our stage, sets, and offices and set up in another state.

In April 2014, the Maryland Legislature approved (and the Governor agreed to sign) legislation providing the House of Cards $11.5 million in tax credits for the upcoming season. The producers indicated they will start filming the third season of the show in Maryland within a few months. The series airs on Netflix, an online video streaming service whose parent company is based in Los Gatos, California.

Subsidies in Some States Very Generous. State film and television production incentives typically have key elements in common. Most programs provide corporate and sales tax benefits. Some states, such as Texas and Michigan, provide a cash grant or rebate to qualified film and television productions instead of a tax credit. In most states, the tax credit is transferable or refundable because most production companies and their parent corporations would not have a sufficiently large tax liability in the state to offset the full tax credit. The value of the incentive usually is based on a percentage of production expenses. These expenses typically are qualified in some way. For example, nearly all states allow only so–called “below–the–line” wages to count towards the credit; however, several states allow some or all “above–the–line” expenses to also qualify. (Above–the–line expenses are the wages and fees paid to the leading actors, the writer, and the director and below–the–line wages are for crew, some cast, and most production staff.) Figure 9 compares California’s tax incentive program with the other programs in the top ten states providing the most funding for film and television production subsidies. New York and Louisiana offer a subsidy worth up to 35 percent of qualified expenditures. New York has capped its program at $420 million per year, and we do not know if that amount will be exhausted this year. Louisiana’s program has no annual cap and it allocated $236 million of tax credits in 2012.

Figure 9

California’s Film Tax Credit Program Ranks Fifth in Nation in Annual Cost

(Dollars in Millions)

|

State

|

Incentive Percenta

|

Incentive Refundable?

|

Incentive Transferable?

|

Annual Costb

|

|

New York

|

30 – 35

|

Yes

|

No

|

$420

|

|

Louisiana

|

30 – 35

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

236

|

|

Georgia

|

20 – 30

|

No

|

Yes

|

140

|

|

Florida

|

20 – 30

|

No

|

Yes

|

131

|

|

California

|

20 – 25

|

No

|

Noc

|

100

|

|

Texasd

|

5 – 20

|

—

|

—

|

95

|

|

North Carolina

|

25

|

Yes

|

No

|

77

|

|

Connecticut

|

10 – 30

|

No

|

Yes

|

64

|

|

Pennsylvania

|

25 – 30

|

No

|

Yes

|

60

|

|

Michigand

|

20 – 35

|

—

|

—

|

50

|

|

Total

|

|

|

|

$1,373

|

Other Countries Offer Subsidies Too. California’s most significant competitors may be certain Canadian provinces and the United Kingdom. In addition to offering generous film and television production subsidies, Canada and the United Kingdom also possess high–quality soundstages, experienced crews, and post–production facilities with many specialized suppliers and vendors located near their major production centers.

California’s Response

California Offers a Film and Television Production Subsidy. California’s film tax credit program is the fifth largest in the U.S. in terms of available funding. The film tax credit program has a $100 million annual funding cap and the CFC allocates the credits by lottery. On the first day of the 2013 application period, the CFC received 380 applications and allocated a tax credit to 34 projects.

California’s program provides a tax credit for 20 percent of qualified expenditures for eligible film and television projects. Television series relocating to California from other jurisdictions and “independent” films are eligible for a tax credit of 25 percent of qualified expenditures. While this is less than the 30 percent or more that some other states offer, many industry experts we spoke with indicate that other cost advantages of filming in California offset this difference. Under current law, only certain types of productions are eligible to apply for and receive a tax credit.

- A film with a production budget less than $75 million (and more than $1 million).

- A television film (“movie–of–the–week”) or a television mini–series with a production budget more than $500,000.

- A new television series with a production budget of more than $1 million that is licensed for original distribution on “basic cable.” (This term does not include television series distributed through a broadcast television network, such as ABC, or a premium cable network, such as Showtime.)

- An independent film.

- A television series that relocated to California.

Independent film productions, which account for at least 10 percent of the tax credits, are allowed to sell their credit to another taxpayer. (Independent films are defined by statute as having a budget between $1 million and $10 million and are not produced by a company that is publicly traded or a company in which a publicly traded company owns more than 25 percent of the independent production company.) As we discuss in the box below, California provides some additional tax benefits to the motion picture industry. (Some other states provide similar tax benefits.)

Sales Tax Exemptions. California provides the motion picture industry with tax benefits in addition to the $100 million film tax credit. California imposes a sales tax on retailers selling tangible personal property and levies a property tax on personal property. Leases of motion picture films and video tapes for exhibition or broadcast are exempt from the sales tax. In addition, there are several other sales tax exemptions affecting the motion picture industry.

Personal Property Tax Assessed Only on Media, Not Content. Personal property, which includes films and videos owned by businesses, is assessed each year at market value, which accounts for depreciation. In California, personal property taxes are levied only on the tangible materials upon which such motion pictures are recorded, and not on the full market value of the film or television program.

Frequently Cited Limitations of California’s Tax Credit Program. Several recent studies have noted several key limitations of the California film tax credit program. Perhaps the most frequently cited limitation is that the program turns away nine out of ten qualified applicants due to the $100 million funding cap. The amount available for new film and television series effectively is somewhat less than $100 million because any television series that received a tax credit allocation in the prior year is first in line to receive a credit in the following year.

Figure 10

Factors to Consider When Reviewing the Film Tax Credit

|

|

- Film and television production in California could decline anyway.

|

- Responding to other jurisdictions’ subsidies could be very expensive.

|

- Interstate and international competition could stoke a “race to the bottom.”

|

- For state government, the film tax credit does not “pay for itself.”

|

- Subsidizing one industry sets an awkward precedent.

|

- It will be difficult to evaluate the effectiveness of the film tax credit.

|

Another frequently cited limitation of the tax credit program is that, under current law, the most economically desirable types of productions—typically considered to be large–budget films and network and premium cable television series—are not eligible to apply for a tax credit. This is because the tax credit program was designed to attract or retain certain types of productions that had been considered most vulnerable to being produced outside of California when the credit was established.

CFC Provides Additional Assistance to Filmmakers. The CFC promotes the state to the motion picture industry and administers the film tax credit program. The commission also provides filmmakers with other services, including assistance in finding a suitable location, information about state regulations, and assistance on other topics such as “green” filmmaking. The CFC serves as a one–stop shop for issuing permits to crews filming on state property. Unlike in many other states, film and television productions in California do not pay fees to get state permits. Rather, the state General Fund pays all of the operating costs of the CFC, including costs related to permit processing. The commission, however, has statutory authority to charge fees to cover the costs of filming on state property and state employee services.

Local Government Fees and Incentives. Most local governments in California charge fees for permits and specific costs related to motion picture production, such as for street closures. Some local governments in California offer local film and television production incentives. San Francisco, for example, refunds all fees and payroll taxes paid to the city, up to $600,000 per film or television episode. Santa Clarita refunds film permit fees and 50 percent of the transient occupancy taxes collected in the city. Other cities in other states also offer some incentives.

Ideally, States Would Not Compete On the Basis of Subsidies

In our view, states ideally would not use subsidies to compete for film and television productions—or for any other specific industry. We generally view industry–specific tax expenditures—such as these film tax credits—to be inappropriate public policy because they (1) give an unequal advantage to some businesses at the expense of others and (2) promote unhealthy competition among states.

Advantage Some Businesses Unequally. The ten states shown in Figure 9 collectively give film and television production companies about $1.4 billion per year. Twenty–seven other states give the industry additional sums. These subsidies give businesses in the motion picture industry an economic advantage that other businesses do not receive. Instead, all other businesses and taxpayers effectively pay a higher tax rate than they would otherwise because the costs of running the state, including paying these subsidies, are raised from fewer taxpayers. We would generally only recommend the Legislature provide a subsidy when an industry’s activities yield distinct societal benefits that would otherwise be produced at a lower than economically optimal level. For example, subsidies for basic research and development may be justified at the federal level because of the broad social benefits of that research.

Promote Unhealthy Competition Among States. When government does not offer industry subsidies, businesses in those industries generally locate their economic activities based on where they would be best suited. For example, agriculture generally plants crops where they are most productive and manufacturing generally locates where it has most advantageous access to inputs, labor, and markets. State film and television subsidies shift an activity from where it would otherwise locate to somewhere else without necessarily improving the output or yielding any greater social benefit. At the same time, these subsidies reduce funds available for other state priorities, including spending on programs or reductions in tax rates that would benefit all taxpayers equally.

But There Are Reasons for California to Consider Subsidies

Reasonable Considerations to Extend or Expand Credit. Many observers—including our office—have raised concerns about whether industry–specific subsidies are good public policy. Nonetheless, we recognize that some factors might reasonably lead the Legislature to extend or expand California’s film tax credit. Specifically, (1) the motion picture industry, including production and post–production, are a flagship California industry, (2) the motion picture industry is a major employer in Los Angeles, paying high wages, and (3) other states are aggressively competing for this industry and, in some cases, industry representatives are threatening to move production to other jurisdictions if public subsidies are not provided.

Flagship California Industry. The motion picture industry is a key part of the state’s “brand” and identity. For example, the industry is frequently highlighted in state and private–sector marketing strategies for tourism and economic development purposes. Many tourists visit the Los Angeles area either primarily or in part because of attractions related to current or historical film and television production. California’s motion picture industry is not going to disappear overnight because of other jurisdictions’ subsidies, but there may be a long–term risk that California could lose a significant share of this flagship industry. It is reasonable for the Legislature to want to take action to prevent this.

High–Paying Los Angeles–Focused Industry. We also note that the motion picture industry is a large employer in Los Angeles County and pays significantly higher than average wages. Later in the report, we express serious concerns with the economic impact studies that overstate the economic benefits of the film tax credit. However, the hundreds of thousands of Californians directly or indirectly employed as a result of the industry deserve serious consideration.

Interstate and International Competition. In some cases, industry representatives have aggressively promoted film and television production subsidies in other states, and these states (and other countries) are offering subsidies to lure productions away from California. These subsidies appear to have negatively affected the volume of film and television production in California. In some cases, industry representatives are threatening to move production to other jurisdictions if public subsidies are not provided, and these threats are sometimes credible. Given that other states and countries are offering subsidies, it may be difficult for California not to provide subsidies and still retain its leadership position in this industry. That is, it may be reasonable for California to provide subsidies to “level the playing field” and eliminate the economic incentives to locate productions outside of California. Of the three factors discussed in this section, the aggressive interstate and international competition may be the most compelling because its focus is on correcting an economic distortion.

Issues to Consider if California Offers a Film Tax Credit

If the Legislature wishes to continue or expand the film tax credit, we suggest that it do so cautiously. In Figure 10, we highlight six key factors for consideration by the Legislature as it reviews film tax credit proposals.

California Film and Television Production May Decline Anyway

The motion picture industry is confronting many pressures and undergoing many changes that are affecting the level and locations of film and television production.

Film and Television Production in the U.S. Facing Many Pressures. The available economic and employment data on film and television production and post–production, while limited, suggests that the U.S. industry may be growing somewhat more slowly over the past decade than it did during the preceding decades. The industry may also be growing more slowly than the overall U.S. economy. There are likely various reasons this is so, as the industry is facing many pressures. Thus, even in the absence of other states’ and countries’ subsidies, the level of film and television production activity in California might decline or grow slowly.

Various Factors Encourage Filming Outside of California. While there are practical and economic reasons for the motion picture industry to cluster in the Los Angeles area, there are also various practical and economic reasons that may encourage filming outside of California. Some of the technological changes discussed earlier in this report have made it easier and less costly to film outside of the Los Angeles area. The motion picture industry is also a global industry and is becoming increasingly global. Like many other industries, some production may relocate to other countries for reasons unrelated to subsidies.

Responding to Other Jurisdictions’ Subsidies Could Be Very Expensive

California’s current film tax credit program costs the state about $100 million per year. Critics suggest that the film tax credit has not effectively countered the efforts of other states to lure production away from California because the program:

- Funds only one out of ten eligible applicants.

- Disqualifies a large portion of the industry’s products, including large–budget films and most television series.

Broadly Expanding the Film Tax Credit Could Increase Annual Cost by Several Billion Dollars. Revising the current film tax credit to fully respond to these criticisms would be very expensive. Providing the tax credit to all projects that are currently eligible could increase the annual cost by about $1 billion. Expanding the eligibility criteria to include a very broad array of productions would further increase the cost of the program—perhaps by several billion dollars. California’s share of the film and television industry is so large, that it would be infeasible to provide subsidies to all productions.

Rationing Tax Credits Reduces the Fiscal Impact, Leads to Counterproductive Distortions. Given budget limitations, a reasonable response is to restrict eligibility to certain types of productions—as the current program does. However, choosing which types of productions to subsidize is difficult and has consequences. Legislators should be mindful of these potential consequences. Before the film tax credit program was adopted, for example, large–budget films and network and premium cable television series commonly were filmed in California. It is our understanding that when the current program was designed, smaller productions—believed to be more budget–conscious—were thought to be most likely to relocate to other states because of subsidies. Thus, the California film tax credit specifically targeted these smaller productions. Since then, it appears that the state has attracted television movies and one–hour basic cable series, but far fewer large–budget films and one–hour network and premium cable television series are filmed in California. While various factors may have contributed to this trend, it is likely in part a consequence of the state’s decision to target tax credits to certain types of productions.

Expansion May Lead to Other Changes in Film Tax Credit. The current tax credit is not refundable and is transferable only for independent productions. If the tax credit were expanded significantly, production companies might not have a sufficiently large tax burden against which to offset these tax credits. This, in turn, might increase calls for the Legislature to expand transferability or allow for refundable tax credits.

Local Governments Could Share the Cost of an Expanded Tax Credit. Continuing or expanding the tax credit program would reduce state tax revenues—affecting all residents of the state—while largely benefiting a single region of the state. A reasonable response might be to request the affected local governments to share the burden. We fully expect that motion picture production in California will remain heavily concentrated in the Los Angeles area, such that the state’s leaders may wish to discuss cost sharing with city and county governments there.

Could Stoke the “Race to the Bottom”

The unhealthy competition between states mentioned above also seems to have become increasingly aggressive over time. As states compete amongst each other to attract film and television productions, the amount of the subsidy offered by each state may increase. This is demonstrated by the actions states have taken in recent years to increase their initial subsidies—from 20 percent to 25 percent and from 25 percent to 30 percent of qualified expenditures—in an effort to attract, and then retain, film and television productions in the face of increasingly aggressive interstate competition.

Were California to increase its subsidy, it is possible that competitors in other states and abroad would further increase theirs as well. This sort of competition can be characterized as a race to the bottom. It is unclear how these sorts of competitions end. In responding to other states increased subsidy rates, California may only stoke this race to the bottom without making any real headway in terms of increasing its share of film and television productions. Meanwhile, the expense of the film tax credit program would increase.

For State Government, the Film Tax Credit Does Not Pay For Itself

Some advocates of the film tax credit argue that it pays for itself, in terms of increased tax revenues to government, and that the film and television production spending it attracts trickles through the economy generating significant economic gains. While these considerations are important, there are other economic and fiscal effects to take into account. Moreover, we have found that the analyses used to support the film tax credit vastly overstate their findings.

2012 Analysis Aggregated State and Local Tax Revenue. In 2012, our office reviewed a study produced by the LAEDC that calculated that every $1 of tax credit returned $1.06 in state and local tax revenue. We concluded at the time that, since this amount included local tax revenue and the costs of paying for the tax credit program fall entirely on state government, the program probably did not produce enough state government revenues to pay for itself. Nothing that we have learned since that date alters our assessment.

Analysis Suggests Film Tax Credit Returns to State 65 Cents per $1 of Tax Credit. In March 2014, the LAEDC revised its calculations based on additional data. This new study calculated that every $1 of tax credit returned $1.11 in state and local revenue. We requested more detailed information from the LAEDC and, from that information, we learned that the $1.11 includes all payments to state and local government—including fees, permits, and unemployment insurance payments. In our view, the analysis overstates the tax credits’ fiscal effect because it assumes that all credit recipients otherwise would have located in another state. The analysis also overstates the fiscal benefit to the state government—the entity providing these credits—by including local tax revenue, fees for services, and payments for unemployment benefits. Were it to have reported the data in a disaggregated fashion, the LAEDC’s data would have shown that for each $1 received in state tax credits, California productions return about:

- $0.65 to the state in sales and use tax, personal income tax, corporation tax, and other tax revenue that the state receives or that directly reduces state costs.

- $0.35 to local governments in property taxes, motor vehicle license fees, and the local share of sales taxes. (Most property taxes allocated to schools and community colleges are included above in the state total.)

- $0.08 in state and local fees for services.

- $0.03 in federal and state social insurance taxes such as unemployment insurance and Social Security.

A return of $0.65 in state tax (excluding unemployment insurance) revenue for each $1 in tax credits may or may not be a good return compared with other state programs. However, it is incomplete—and, arguably, not accurate—to claim that the tax credit program pays for itself based on the LAEDC data. The state government receives far less revenue back than it spends on the tax credit, according to the study.

Economic Benefits Overstated. Film and television productions attracted by the subsidy generate economic activity in the state by hiring crew and purchasing goods. The LAEDC studies estimate the economic benefits resulting from California’s tax credit program. As we have stated in the past in reviewing these types of studies, there is nothing inherently wrong with the economic modeling tools used to attempt to estimate these economic effects. However, the methodology used usually overstates the net economic benefits. If a film project was attracted to the state because of the tax credit, and would not have otherwise filmed in the state, the economic benefit of the film is calculated based on how its spending trickles through the economy—a phenomenon called the multiplier effect. However, the existence of a multiplier effect does not imply that the subsidy generates economic gains that are greater than its costs.

In its economic impact studies, the LAEDC offsets the total estimated economic benefits only by the $100 million per year fiscal cost of the credits to the state. This is different and smaller than the economic cost, which includes (1) the economic impact of the best alternative use of the $100 million (called the “opportunity cost”) and (2) other economic costs related to film and television production. For example, the state could have used the $100 million instead to provide additional funding for other state programs, such as early childhood education or inmate rehabilitation. And just like the subsidy, any alternative funding decision would have created economic benefits through an economic multiplier effect. This is important because it is possible that an alternative funding decision could have a greater economic benefit than the film tax credit. Also, in order to be comprehensive, these studies should consider other economic costs of increased film production. When the film and television industry uses labor and other productive inputs, those inputs are not available for other uses, which may negatively affect other industries.

We note that many other economic studies of state policies (not just film tax credits) have similar defects. Economic analyses of the multiplier effects of proposed policies can provide useful information regarding the potential economic benefits, but it is unusual for these studies to estimate the “net” economic effect of a policy—which fully accounts for economic costs. Therefore, these studies rarely can establish in and of themselves whether a policy is the “best” choice for the public.

Sets an Awkward Precedent

As we note above, the Legislature may wish to provide a tax credit to this industry because of the generous subsidies offered by other states. We note, however, that other industries—such as manufacturing or software development—also could become the target of aggressive state subsidies. If this were to occur, would California also provide subsidies to retain these businesses? Doing so could be prohibitively expensive. Instead of approaching economic policy on an industry–by–industry basis, the Legislature may take actions that encourage all businesses to stay or relocate to California, such as broad–based tax reductions or regulatory changes.

Film Tax Credit Effectiveness Will Be Difficult to Evaluate

Due to (1) the many ongoing pressures and changes confronting the motion picture industry, (2) incentive programs offered by other states and countries, and (3) the limitations inherent in economic statistics available to measure industry productivity and employment, it will be difficult for the Legislature to evaluate the effectiveness of the film tax credit (or any other policies adopted to encourage production in California). This will especially be the case if the effect is small or if the industry changes in other significant ways. Such data limitations often will be present in evaluating industry–specific subsides. The Legislature should anticipate the likelihood of having to make ongoing decisions regarding the film tax credit without the benefit of conclusive evidence. We expect, for example, that our office’s statutorily required report on the program will lack such conclusive evidence.