In this report, we provide an overview of the Governor’s higher education budget and then turn to the Governor’s specific proposals for: (1) the universities, (2) community colleges, (3) new higher education innovation awards, and (4) tuition and financial aid. In each of these four areas, we analyze the Governor’s proposals and offer recommendations for the Legislature’s consideration.

Provides $20 Billion in Core Funding for Higher Education. Under the Governor’s proposal, total core funding for higher education in 2014–15 is $20 billion—a $1.3 billion (7 percent) increase over the 2013–14 level. As shown in Figure 1, nearly all the increase in core funding is covered by the state General Fund. In addition to state General Fund support, the universities receive significant support from student tuition revenues. Under the Governor’s proposal, tuition levels at the universities would remain flat. (Total tuition revenue increases slightly at UC due to an increase in nonresident students. It increases slightly at CSU due to a projected 2 percent increase in enrollment.) For the community colleges, local property tax revenue and student fee revenue are other main sources of core funding. The Governor’s budget estimates that local property tax revenue will be up $94 million (4 percent) from the current–year level. Student fee revenue is budgeted to increase $13 million (3 percent) due to enrollment growth.

Figure 1

Higher Education Core Funding

(Dollars in Millions)

|

|

2012–13 Actual

|

2013–14 Revised

|

2014–15 Proposed

|

Change From 2013–14

|

|

Amount

|

Percent

|

|

University of California (UC)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

General Funda

|

$2,566

|

$2,844

|

$2,987

|

$142

|

5%

|

|

Net tuitionb

|

2,525

|

2,605

|

2,651

|

46

|

2

|

|

Other UC core fundsc

|

351

|

344

|

331

|

–13

|

–4

|

|

Lottery

|

30

|

38

|

38

|

—

|

—

|

|

Subtotals

|

($5,471)

|

($5,831)

|

($6,006)

|

($175)

|

(3%)

|

|

California State University (CSU)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

General Funda,d

|

$2,473

|

$2,789

|

$2,966

|

$177

|

6%

|

|

Net tuitionb

|

2,009

|

2,014

|

2,055

|

41

|

2

|

|

Lottery

|

40

|

56

|

57

|

1

|

2

|

|

Subtotals

|

($4,522)

|

($4,859)

|

($5,078)

|

($219)

|

(5%)

|

|

California Community Colleges (CCC)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

General Funda

|

$4,269

|

$4,390

|

$4,828

|

$438

|

10%

|

|

Local property tax

|

2,241

|

2,232

|

2,326

|

94

|

4

|

|

Fees

|

425

|

435

|

448

|

13

|

3

|

|

Lottery

|

157

|

182

|

182

|

—

|

—

|

|

Subtotals

|

($7,092)

|

($7,238)

|

($7,784)

|

($545)

|

(8%)

|

|

Hastings College of the Law (Hastings)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Net tuitionb

|

$33

|

$33

|

$30

|

–$2

|

–7%

|

|

General Funda

|

9

|

10

|

11

|

1

|

13

|

|

Subtotalse

|

($42)

|

($42)

|

($41)

|

(–$1)

|

(–3%)

|

|

California Student Aid Commission (CSAC)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

General Fund

|

$671

|

$1,042

|

$1,299

|

$257

|

25%

|

|

Student Loan Operating Fund

|

85

|

98

|

60

|

–38

|

–39

|

|

TANF funds

|

804

|

542

|

545

|

3

|

1

|

|

Subtotals

|

($1,559)

|

($1,682)

|

($1,904)

|

($222)

|

(13%)

|

|

California Institute for Regenerative Medicine

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

General Funda

|

$53

|

$97

|

$284

|

$187

|

193%

|

|

Awards for Innovation in Higher Education

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

General Fund

|

—

|

—

|

50

|

50

|

N/A

|

|

Totalsf

|

$17,685

|

$18,583

|

$19,893

|

$1,310

|

7%

|

|

General Fund

|

$10,041

|

$11,173

|

$12,425

|

$1,252

|

11%

|

|

Net tuition/feesf

|

3,936

|

3,919

|

3,930

|

11

|

—

|

|

Local property tax

|

2,241

|

2,232

|

2,326

|

94

|

4

|

|

Other

|

1,239

|

984

|

936

|

–48

|

–5

|

|

Lottery

|

228

|

275

|

276

|

1

|

—

|

Funding Per Student Would Increase at All Segments. Figure 2 shows another perspective on higher education funding—one that adjusts for enrollment levels and any accounting changes (such as payment deferrals) that otherwise would distort year–to–year programmatic comparisons. The figure focuses on the amount of funding generally available to support operational costs. As shown in the figure, funding per FTE student in 2014–15 under the Governor’s budget ranges from about $6,000 at CCC to nearly $42,000 at Hastings. (The difference in level of support largely reflects the segments’ different missions.) Year–over–year, the percentage increase in per–student funding ranges from 2 percent at UC to 6 percent at Hastings. (The increase at Hastings reflects a 2.6 percent reduction in total funding combined with an 8.1 percent decrease in enrollment.)

Figure 2

Higher Education Support Funding Per Full–Time Equivalent Studenta

(Dollars in Millions)

|

|

2012–13 Actual

|

2013–14 Revised

|

2014–15 Proposed

|

Change From 2013–14

|

|

Amount

|

Percent

|

|

Hastings College of the Law

|

$34,151

|

$39,535

|

$41,896

|

$2,361

|

6%

|

|

University of California

|

21,295

|

22,736

|

23,249

|

513

|

2

|

|

California State University

|

11,879

|

12,506

|

12,823

|

318

|

3

|

|

California Community Colleges

|

5,671

|

5,997

|

6,266

|

269

|

4

|

Governor Proposes 10 Percent General Fund Increase. The state is the largest source of core funding for UC, CSU, and CCC. As shown in Figure 3, the Governor’s budget includes $13 billion in total state General Fund support for higher education in 2014–15—a $1.2 billion (10 percent) increase over the revised 2013–14 level. (For this comparison, we include support from the Student Loan Operating Fund (SLOF) and the federal Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) program because these sources directly offset General Fund support for Cal Grants. In effect, these sources are interchangeable with General Fund.)

Figure 3

Higher Education General Fund Support

(Dollars in Millions)

|

|

2012–13 Actual

|

2013–14 Revised

|

2014–15 Proposed

|

Change From 2013–14

|

|

Amount

|

Percent

|

|

University of California

|

$2,566

|

$2,844

|

$2,987

|

$142

|

5%

|

|

California State Universitya

|

2,473

|

2,789

|

2,966

|

177

|

6

|

|

California Community Collegesb

|

4,269

|

4,390

|

4,828

|

438

|

10

|

|

California Student Aid Commissionc

|

1,559

|

1,682

|

1,904

|

222

|

13

|

|

California Institute for Regenerative Medicine

|

53

|

97

|

284

|

187

|

193

|

|

Hastings College of the Law

|

9

|

10

|

11

|

1

|

13

|

|

Awards for Innovation in Higher Education

|

—

|

—

|

50

|

50

|

N/A

|

|

Debt–Service Obligationsd

|

(1,027)

|

(1,027)

|

(1,255)

|

(228)

|

(22)

|

|

Totals

|

$10,930

|

$11,812

|

$13,030

|

$1,218

|

10%

|

Large Increases for Universities, Community Colleges, Student Aid. The Governor’s major proposed augmentations for higher education are: base increases at the universities, increases in apportionment funding and two categorical programs at the community colleges, Cal Grants growth, and implementation of the new Middle Class Scholarship program approved by the Legislature last year, as shown in Figure 4. (The Governor’s budget also contains a $187 million increase for debt service for bonds that support CIRM research. The increased payments are related to the timing of previous bond issuance.)

Figure 4

Governor’s Higher Education General Fund Spending Changesa

(In Millions)

|

2013–14 Budget Act

|

$11,564

|

|

Provide additional funds for CCC deferral paydown

|

$163

|

|

Backfill for CCC redevelopment agency revenue

|

38

|

|

Other adjustments

|

47

|

|

Total Change

|

$248

|

|

2013–14 Revised Spending

|

$11,812

|

|

Provide 5 percent base increases for UC, CSU, and Hastings

|

$286

|

|

Increase funding for CCC Student Success and Support program

|

200

|

|

Adjust debt–service payments

|

187

|

|

Increase CCC maintenance and instructional support

|

175

|

|

Fund 3 percent CCC enrollment growth

|

155

|

|

Implement Middle Class Scholarship program

|

107

|

|

Fund Cal Grant program growth

|

100

|

|

Fund new Awards for Innovation

|

50

|

|

Provide 0.86 percent CCC cost–of–living adjustment

|

48

|

|

Provide additional funds for CCC deferral paydown

|

43

|

|

Adjust employee compensation and benefits

|

24

|

|

Expand Cal Grant renewal eligibility

|

15

|

|

Remove one–time funding

|

–55

|

|

Adjust for anticipated CCC redevelopment agency revenue

|

–3

|

|

Other adjustments

|

–115

|

|

Total Change

|

$1,218

|

|

2014–15 Proposed Spending

|

$13,030

|

In this section, we start by providing background on major actions taken in last year’s budget for UC and CSU. Next, we discuss the Governor’s 2014–15 plan for the universities, assess the plan, and offer an alternative plan for the Legislature’s consideration. For the alternative, we rely on a number of guiding principles for developing university budgets that we lay out in our recent publication, A Review of State Budgetary Practices for UC and CSU.

Last Year Governor Proposed Multiyear Plan for Universities. Last year, the Governor proposed a four–year funding plan for the universities that included unallocated base budget increases of 5 percent each year for 2013–14 and 2014–15, followed by 4 percent increases in each of the subsequent two years. The plan also called for an extended tuition freeze. In addition, the plan proposed to increase the universities’ flexibility to allocate funds by (1) removing enrollment targets, (2) eliminating most earmarks (such as for student outreach programs), and (3) combining support and capital budgets.

Legislature Adopted Some Elements of Governor’s Plan, Rejected Others. The Legislature adopted the proposed 5 percent base increases for both universities, though it did not commit to out–year, unallocated funding increases or the extended tuition freeze. The Legislature also set enrollment targets and restored some earmarks. The Governor, however, vetoed the enrollment targets and nearly all the earmarks, citing a desire to give the universities greater flexibility to manage their resources. The Legislature approved the Governor’s proposal to combine UC’s support and capital budgets, but rejected this same proposal for CSU.

The Governor’s 2014–15 budget plan for the universities is largely a continuation of the multiyear plan he introduced last year, as detailed below.

Proposes Increase in General Purpose Funding for Universities. The Governor proposes unallocated base budget increases of $142 million each for UC and CSU in 2014–15. These increases represent the second annual installment in the four–year funding plan he proposed last year. About $10 million of CSU’s increase is related to a new proposed process for funding capital projects, discussed in the next paragraph. In addition, the Governor adjusted CSU’s budget for changes in debt service, retirement contributions, and retired employee health care costs.

New Capital Outlay Process for CSU. Similar to the new capital outlay process approved for UC last year, the Governor proposes to shift general obligation and lease–revenue bond–debt service payments into CSU’s main appropriation. Moving forward, CSU would be responsible for funding debt service from within this main appropriation. Under the proposal, the university would issue its own revenue bonds for various types of capital projects and could restructure its existing lease–revenue bond debt. To use its new authority, the university would be required to submit project proposals to the Joint Legislative Budget Committee (JLBC) and Department of Finance (DOF) for approval. The CSU’s capital projects no longer would be reviewed as part of the regular budget process.

No Enrollment Targets for Universities. Similar to last year, the Governor does not propose enrollment targets or enrollment growth funding for the universities. The Governor’s budget summary shows resident enrollment flat in the budget year at UC, growing by 2.3 percent at CSU, and decreasing by 8 percent at Hastings. (The administration indicates these enrollment levels are shown for “display purposes only and do not constitute an enrollment plan.”)

Assumes No Tuition Increases. The Governor once again conditions his proposed annual funding increases for the universities on their continuing to freeze tuition at 2011–12 levels. This proposal is discussed in more detail in the “Tuition and Financial Aid” section of this report.

Requires UC and CSU to Adopt Sustainability Plans. The Governor proposes budget bill language requiring the UC and CSU governing boards to adopt three–year sustainability plans by November 30, 2014. Under this proposal, the universities would project expenditures for each year from 2015–16 through 2017–18 and describe changes needed to ensure expenditures do not exceed available resources (based on General Fund and tuition assumptions provided by DOF). The segments also would project resident and nonresident enrollment for each of the three years and set targets for the performance measures approved as part of last year’s budget package. (This package included measures of enrollment, student progress, graduation, degrees awarded, funding per degree, and efficiency, with several of the measures disaggregated for undergraduate and graduate students, transfer students, low–income students, and students in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics disciplines.)

Similar to last year, we have serious concerns about the Governor’s overall budgetary approach for the universities and recommend the Legislature reject it. Most troubling, the Governor’s budget does not link university funding to state priorities. Although the Governor enumerates several higher education priorities in his budget summary (for example, reducing the cost of education and improving affordability, timely completion rates, and program quality), his funding plan includes large unallocated increases tied only to maintaining flat tuition levels. The budget requires the universities to set performance goals, but does not establish state performance expectations or link the universities’ funding to meeting these expectations. Further, the Governor’s approach to CSU capital outlay takes funding decisions out of the legislative budget process. This overall budgetary approach diminishes the Legislature’s role in key decisions and allows the universities to pursue their own interests rather than state–identified priorities.

Recommend Budgetary Approach That Designates Funding for Specific Purposes. In our recent publication, A Review of State Budgetary Practices for UC and CSU, we recommended the Legislature build the universities’ budgets based on enrollment growth, inflation, targeted set–asides, and capital outlay, while assuming that cost increases are shared by students and the state. We further recommended the Legislature incorporate performance measures into its budget decisions. Below, we lay out a specific alternative to the Governor’s plan that addresses each of these areas. For enrollment, we recommend funding growth at CSU and keeping enrollment flat at UC. We recommend funding inflationary cost increases at the universities and providing targeted augmentations for debt service, pensions, and retiree health costs. For capital outlay, we recommend rejecting the Governor’s proposal to remove CSU capital outlay from the regular budget process. For performance, we recommend the Legislature monitor the universities’ performance and use the results to inform budget decisions.

LAO Alternative Plan Provides Higher Support for UC and CSU, but Requires Less State Spending. Altogether, our alternative would provide $186 million ($108 million from the state General Fund and $78 million from increased student tuition) for UC and $209 million ($125 million from the state General Fund and $84 million from increased student tuition) for CSU. In total, our alternative would provide $62 million more than the Governor’s proposal for the universities. Because tuition would cover a share of the increased funding, however, the General Fund increase is $100 million less than the Governor’s proposed General Fund augmentation.

Enrollment

To determine how many enrollment slots to provide at UC and CSU, we consider information about demographic changes, college participation rates, freshman and transfer eligibility, and state workforce needs, as discussed below.

Demographic Projections Show College–Age Population Decreasing. One main factor to consider related to enrollment growth is demographic changes. In particular, changes in the traditional college–age population (comprised of 18– to 24–year olds) and changes in the number of California high school graduates are key drivers of enrollment at the universities. State demographic projections show the college–age population declining by about 1 percent from 2014 to 2015. State projections also show the number of California high school graduates decreasing by about 1.5 percent from 2013–14 to 2014–15. These downward trends suggest no pressures for enrollment growth from demographic changes in the budget year.

College Participation Rates More Difficult to Predict, Assume Remain Flat. Another factor that affects enrollment levels is college participation rates. This is the percentage of individuals in a particular demographic category (such as recent high school graduates or the 18– to 24–year old population) attending college. Increases in participation rates can drive increases in enrollment, while decreases in participation rates can result in less enrollment. The most recent data available on participation rates from the federal Department of Education show the percent of recent California high school graduates attending college decreasing from 65.4 percent in 2008 to 61.7 percent in 2010. Predicting future participation rates based on these past trends, however, is difficult. This is because students’ interest in attending college is influenced by a number of factors, including student fee levels, availability of financial aid, and the availability and attractiveness of other postsecondary options. Without better information to project future participation rates, we assume they remain flat in the near future.

State Lacks Reliable Data on Access. In addition to demographics and participation rates, another factor to consider is whether the universities are providing access to all eligible students. Under the state’s Master Plan for Higher Education, students in the top 12.5 percent and 33 percent of high school graduates are eligible to attend UC and CSU, respectively. Because student achievement levels and university admissions policies can change over time, the state in the past periodically conducted eligibility studies to identify the pool of high school graduates from which the universities were drawing. These studies then were used to help guide enrollment decisions. For instance, if UC and CSU were drawing from beyond their freshman eligibility pools, this would indicate that the universities needed to tighten their admissions criteria. Because the state’s last eligibility study was conducted in 2007—and the California Postsecondary Education Commission, the state agency that performed the studies, was closed down in 2011—the Legislature lacks a current freshman eligibility study to help guide its enrollment decisions.

UC Reports All Eligible Students Provided Access. Based on current admissions policies, UC indicates it has been admitting all eligible students in recent years. However, the university reports an increase in the number of students admitted to the system but not to the particular campuses to which they applied. These students are offered admission only to UC Merced.

CSU Reports Some Eligible Students Denied Access. Based on its current admissions policies, CSU indicates that about 26,400 students who met CSU’s eligibility criteria were denied admission for the fall 2013 semester. These students include an unknown mix of eligible students denied access to their local campus and eligible students not applying to their local campus. The latter group are students who may have applied only to campuses with high–demand programs outside their local service area.

Mixed Evidence on Need for Enrollment Growth Related to Workforce Needs. Chapter 367, Statutes of 2013 (SB 195, Liu), specified that state budget decisions should take into account several goals. One of the goals that pertains to enrollment decisions is state workforce needs. In recent years, some studies have suggested that states, including California, need to increase the number of bachelor’s degrees to meet future demand by employers. These studies come to this conclusion mainly by looking at past trends in the proportion of job–holders with a bachelor’s degree and extrapolating these trends into the future. For instance, one recent study concluded that whereas 34 percent of California job–holders had a bachelor’s degree in 2006, by 2025 this proportion would need to increase to 41 percent. At the same time, other studies suggest a surplus of bachelor’s degree–holders exists. For example, another recent study found that nationally nearly half of all job holders with bachelor’s degrees work in jobs for which they are overqualified. Given these conflicting findings, the Legislature may want to proceed cautiously as it begins to consider workforce needs as part of its enrollment decisions.

Available Data Suggest Different Approaches for UC and CSU. We recommend the Legislature weigh the above factors carefully in determining enrollment targets for the universities. Given some factors point in different directions—as well as the gaps in relevant information—the Legislature will need to exercise its professional judgment in crafting an enrollment plan for the universities. Below, we provide enrollment levels for UC and CSU the Legislature could adopt based on the available information. (In the nearby box, we discuss what enrollment targets the Legislature can use as a base from which to make adjustments, given no target was included in the 2013–14 budget.)

- Keep Enrollment Flat for UC in 2014–15. The available data does not suggest a need to increase enrollment at UC in the budget year. The university continues to admit all eligible students and demographic trends suggest enrollment demand could decrease slightly in the near future.

- Increase CSU Enrollment by 2 Percent in 2014–15. Though demographic trends also point to a decrease in demand for CSU enrollment, the university is reporting an inability to accommodate existing eligible students. Determining how much enrollment funding to provide to address this concern is difficult, given a lack of solid information on how many of the denied eligible students have been denied access to their local campus versus another campus in the system. Further complicating matters is an inability to accurately estimate how many of the denied eligible students actually would attend CSU if offered a slot. Taking these factors into consideration, we conclude increasing enrollment by 2 percent (or 7,000 FTE students) is a reasonable approach to address the issue. Further, to ensure that any enrollment growth is used to decrease the number of eligible students being denied admission, we recommend the Legislature include budget bill language requiring CSU to report next year on: (1) the number of eligible students denied admission, including how many of these students were denied admission to their local campus, and (2) the efforts it has made to increase the capacity of impacted campuses and programs.

What Should Base Enrollment Targets Be for UC and CSU?

Enrollment Funding Not Used on a Consistent Basis in Recent Years. As shown in the figure below, the state has not included enrollment targets in the state budget on a consistent basis over the last seven years. During this time, the universities both expanded enrollment when the state did not include an enrollment target in the budget and increased enrollment above the state target when one was included. As a result, both the University of California (UC) and California State University (CSU) assert they currently have “unfunded” students that they are serving. The universities believe that unfunded students should not be included in their state enrollment targets until funding is provided for them.

Recommend Using Current–Year Actual Enrollment Levels as Base for Targets. In our view, the concept of unfunded enrollment is unhelpful since in actuality state funding is spread out across as many resident students as the universities enroll. In other words, all students currently are supported with state funding. Because the so–called unfunded students already are enrolled at the universities, any funding that the state provides for them would not necessarily be used to expand enrollment. To avoid conflating funding for enrollment growth with funding for other purposes, we recommend the Legislature use current–year actual enrollment levels as the base enrollment target moving forward. If the universities feel that they lack adequate base funding for students they currently are serving, then they could come forward with budget requests in the spring that identify why they require more funding.

Enrollment Targets Not Used on a Consistent Basis in Recent Budgets

Full–Time Equivalent Students

|

|

2007–08

|

2008–09

|

2009–10

|

2010–11

|

2011–12

|

2012–13

|

2013–14

|

|

UC

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Enrollment target

|

198,455

|

None

|

None

|

209,977

|

209,977a

|

209,977a

|

None

|

|

Actual enrollment

|

203,906

|

210,558

|

213,589

|

214,692

|

213,763

|

211,212

|

210,986

|

|

Percent change in actual enrollment

|

|

3.3%

|

1.4%

|

0.5%

|

–0.4%

|

–0.5%

|

–0.1%

|

|

CSU

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Enrollment target

|

342,553

|

None

|

None

|

339,873

|

331,716a

|

331,716a

|

None

|

|

Actual enrollment

|

353,915

|

357,223

|

340,289

|

328,155

|

341,280

|

343,227

|

350,000

|

|

Percent change in actual enrollment

|

|

0.9%

|

–4.7%

|

–3.6%

|

4.0%

|

–0.4%

|

2.0%

|

Recommend Providing $42 Million for CSU Enrollment Growth. Using the state’s historical marginal cost formula, we calculate the state funding rate per CSU FTE student for 2014–15 to be $5,999. (The CSU recently has published a lower state funding rate, yet we have been unable to replicate the university’s calculation.) Using our calculated state funding rate, we estimate state costs of $42 million for 2 percent enrollment growth at CSU. In addition, because some of these new students would qualify for state Cal Grants, we estimate the associated costs for Cal Grants would increase by about $8 million.

Recommend Also Setting Out–Year Targets, Funding New Eligibility Study. In our recent publication reviewing state budgetary practices for UC and CSU, we also recommended: (1) setting targets for the year after the budget year to give the Legislature more influence over university enrollment decisions, and (2) funding a new eligibility study to provide updated information for the Legislature to make its enrollment decisions. Given the downward demographic trends in the college–age population, we recommend the Legislature express its intent for enrollment to remain flat at both UC and CSU in 2015–16. (This expectation presumes that the 2014–15 enrollment growth provided to CSU addresses the concern related to eligible students not being able to access their local campuses.) For the eligibility study, the Legislature would have to designate a state agency to perform this task (internally or by contract). These studies involve reviewing transcripts of high school graduates accepted to the universities and typically have included the participation of UC, CSU, and CDE. The last eligibility study conducted in 2007 cost about $600,000.

Inflation

Prices Expected to Increase 2.2 Percent in 2014–15. In 2014–15, prices for goods and services purchased by state and local governments are expected to increase by 2.2 percent. The state traditionally has augmented the universities’ budget to account for such inflation. This allows the universities to maintain their existing programs. In other words, the universities can use this funding to provide employee salary increases (to stay competitive with other employers) as well as to cover increased costs for supplies, materials, and equipment.

Recommend $68 Million Base Increase for UC. Increasing UC’s total core budget by 2.2 percent costs $118 million. (To perform this calculation, we exclude base funding for retiree health care and pensions, which we recommend funding separately.) As part of a share–of–cost policy, we assume that the state and students share this cost increase. Currently, state funding makes up about 58 percent of combined state and student funding (excluding institutional financial aid). Based on this ratio, we recommend the Legislature provide UC with a base increase of $68 million and assume the remaining $50 million comes from an increase in student tuition.

Recommend $53 Million Base Increase for CSU. Increasing CSU’s total core budget by 2.2 percent costs $85 million. (We exclude from this calculation funding for debt service, retiree health care, and pensions, which we recommend funding separately.) Similar to our approach for UC, we recommend the state provide its share of cost (62 percent) and students provide the remaining share. Accordingly, we recommend the state provide CSU with a base increase of $53 million and assume the remaining $32 million comes from an increase in student tuition.

Targeted Funding

Because some cost increases do not track with inflation, the state traditionally has provided a few separate budget adjustments for certain cost changes.

Recommend $25 Million for CSU Pension and Retiree Health Care Costs. Pension and retiree health care costs at CSU are expected to increase by $15.6 million and $24.3 million, respectively. Because CSU participates in the state’s retirement plans, it does not fully control these cost increases. For instance, CSU does not control the employer pension contribution rate or the health care premiums set by the state’s retirement system. Because similar factors drive retirement cost increases for CSU and other state agencies, and the state covers these cost increases for other state agencies, we believe covering CSU’s increased retirement costs too is reasonable. Pension and retiree health care cost increases total $40 million. Based on the state’s share of cost for CSU, we recommend the Legislature provide $25 million and assume the remaining $15 million comes from an increase in student tuition.

Recommend $39 Million for UC Pension and Retiree Health Care Costs. Unlike CSU, UC manages its own retirement plans. Though some differences exist between UC’s plan and the state’s plan, the university has been making changes in recent years that have made them more similar. For instance, starting in 2014–15, the university will increase its employees’ contribution rate from 6.5 percent to 8 percent of salary—the same rate currently paid by most state employees. Given these changes, we believe it is reasonable for the state to provide funding for UC’s retirement costs at this time. In 2014–15, UC expects its pension and retiree health care costs to increase by a total of $68 million. (These cost increases primarily are to address an unfunded liability in the pension plan.) Based on the state’s share of cost for UC, we recommend the Legislature provide UC with $39 million and assume the remaining $29 million comes from an increase in student tuition.

Recommend $5.3 Million for CSU for Debt Service. In 2014–15, lease–revenue debt–service costs for CSU are expected to increase by $8.5 million. Because this increase relates to capital projects previously approved by the state, we recommend the Legislature provide funding to cover this cost increase. Based on the state’s share of cost for CSU, we recommend the Legislature provide CSU with $5.3 million and assume the remaining $3.2 million comes from an increase in student tuition.

Performance

Set Targets, Monitor Performance, and Use Results to Inform Budget Decisons. As we discussed in our recent publication, we recommend the Legislature require UC and CSU to discuss their performance in specific areas (including student access and success) at budget hearings each spring. The Legislature could use this opportunity to learn more about each university’s performance and develop performance expectations moving forward. We further recommend the Legislature use the information reported at budget hearings regarding whether the universities are meeting state expectations to guide funding decisions. In order to do so, the Legislature would need to work with the universities to identify the reasons why they are or are not meeting expectations.

Focus on Ways to Become More Efficient. Under our alternative budget, the Legislature would be funding a workload budget—essentially covering cost increases for the universities. Because this workload budgetary approach does not encourage the universities to become more efficient, the Legislature could focus on efficiency through its performance measures, namely funding per degree. To start, we recommend the Legislature work with the universities to identify ways to increase productivity for a certain level of funding. To build upon efforts already in progress, we further recommend the Legislature require the universities to report on the results of their recent efforts to expand online and hybrid course offerings. The Legislature could then assess whether these new types of courses have succeeded in: (1) expanding access, (2) reducing costs per student, and (3) maintaining educational quality.

Summary of LAO Alternative Budget for UC and CSU

Taken together, we believe that the various aspects of our alternative budget provide a more rational and transparent way to fund the universities than the Governor’s approach. Figure 5 includes the various components of our alternative budgets for UC and CSU and compares them to the Governor’s budget. We discuss the two main implications of our alternative below.

Figure 5

Comparison of Governor’s Budget and LAO Alternative for UC and CSU

2014–15

|

|

UC

|

CSU

|

|

Governor’s Budget

|

|

|

|

Unallocated base increases

|

$142

|

$142

|

|

Retiree health

|

—

|

24

|

|

Pensions

|

—

|

16

|

|

Debt service

|

—

|

9

|

|

Totals

|

$142

|

$191

|

|

Student share

|

—

|

—

|

|

State share

|

$142

|

$191

|

|

LAO Alternative Budget

|

|

|

|

Enrollment growth

|

—

|

$76

|

|

Inflationa

|

$118

|

85

|

|

Retiree health

|

4

|

24

|

|

Pensions

|

64

|

16

|

|

Debt service

|

—

|

9

|

|

Totals

|

$186

|

$209

|

|

Student shareb

|

$78c

|

$84c

|

|

State shareb

|

108

|

125

|

|

Difference in General Fund From Governor’s Budget

|

–$35

|

–$66

|

Compared to Governor, Total Support Higher for Both Universities. As shown in the figure, our plan provides UC with $186 million in additional support in 2014–15, about $44 million more than the Governor’s proposal. The additional spending under our plan recognizes that certain cost increases, such as for inflation and pensions, will exceed the amount provided by the Governor. Our plan provides CSU with $209 million in total support, about $18 million more than the Governor. This is because our plan includes funding for enrollment growth in addition to inflation.

Relatively Modest Increase in UC and CSU Tuition Levels. To generate the additional tuition revenue assumed under our plan, UC would need to increase tuition by 2.5 percent and CSU by 3.3 percent. (If the universities wanted to generate additional funding for intuitional financial aid consistent with their past practice, they would need to increase tuition by 3.8 percent at UC and 5 percent at CSU.)

Slight Increase in Cal Grant Costs. Because our plan includes 2 percent enrollment growth at CSU, Cal Grant costs likely would increase by about $8 million. (This is because overall Cal Grant participation likely would increase.) Because UC and CSU would increase tuition under our plan, state Cal Grant costs also would increase as these awards cover full tuition at the universities. We estimate the cost of the higher awards would total about $30 million.

In this section, we summarize the Governor’s budget for community colleges; discuss his specific proposals related to enrollment growth, student support programs, and the CCC Chancellor’s Office; provide our assessment of those proposals; and offer associated recommendations for the Legislature’s consideration. (We discuss CCC deferrals, deferred maintenance, and mandates in other 2014–15 budget reports.)

Makes Three Notable Changes to the 2013–14 CCC Budget. As shown in the top part of Figure 6, the Governor proposes to increase CCC Proposition 98 spending in 2013–14 by $202 million to $6.2 billion. This increase consists of three notable changes: $163 million to pay down additional CCC deferrals; $38 million to shift a like amount of redevelopment agency–related revenues to the following fiscal year; and $9 million to meet Proposition 30’s requirement that CCC basic aid districts receive a minimum of $100 per FTE student from the Education Protection Account (which, in turn, is backfilled by General Fund).

Figure 6

Proposition 98 Spending Changes for Community Colleges

(In Millions)

|

2013–14 Budget Act

|

$6,032.0

|

|

Additional deferral pay down

|

$162.7

|

|

Redevelopment agency (RDA) shift

|

38.4

|

|

Proposition 30 funds related to basic aid districts

|

9.3

|

|

Technical adjustments

|

–8.9

|

|

Subtotal

|

($201.5)

|

|

2013–14 Revised Spending

|

$6,233.5

|

|

Back Out One–Time Actions

|

|

|

Deferral pay down

|

–$162.7

|

|

Maintenance/instructional support

|

–30.0

|

|

Adult education planning grants

|

–25.0

|

|

Technology initiative adjustment

|

–6.9

|

|

Subtotal

|

(–$224.7)

|

|

Technical Changes

|

|

|

Proposition 39 adjustment

|

–$11.0

|

|

Shift of funding for QEIA to non–Proposition 98

|

–48.0

|

|

Adjustment to RDA shift

|

–2.7

|

|

Adjustment to mandate block grant

|

–0.5

|

|

Other technical changes

|

–40.8

|

|

Subtotal

|

(–$103.0)

|

|

Policy Changes

|

|

|

Deferral pay down

|

$235.6

|

|

Enrollment growth

|

155.2

|

|

Cost–of–living adjustment (0.86 percent)

|

48.5

|

|

Student Success and Support Program

|

200.0

|

|

Maintenance/instructional support

|

175.0

|

|

New technical assistance program

|

2.5

|

|

Subtotal

|

($816.8)

|

|

2014–15 Proposed Spending

|

$6,722.6

|

Proposes to Increase CCC Proposition 98 Funding by $489 Million (8 Percent) in 2014–15. As shown in the main part of Figure 6, the Governor’s budget request for 2014–15 increases Proposition 98 funding for CCC to $6.7 billion. This is $489 million (8 percent) over the revised current–year level. As proposed by the Governor, CCC would receive 10.9 percent of total Proposition 98 funding in 2014–15.

Increases Funding for Both Apportionments and Categorical Programs. Figure 7 details Proposition 98 expenditures for CCC programs. As shown in the figure, 2014–15 apportionment funding would total $5.7 billion, which reflects an increase of $233 million (4.3 percent) from the revised current–year level. The Governor’s budget would increase total funding for categorical programs to $900 million, which is $268 million (42 percent) over the revised current–year level.

Figure 7

Community College Programs Funded by Proposition 98

(Dollars in Millions)

|

|

2012–13 Revised

|

2013–14 Revised

|

2014–15 Proposed

|

Change From 2013–14

|

|

Amount

|

Percent

|

|

Apportionments

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

General Fund

|

$3,351.0

|

$3,221.4

|

$3,360.0

|

$138.5

|

4.3%

|

|

Local property taxes

|

2,240.6

|

2,232.3

|

2,326.3

|

94.0

|

4.2

|

|

Subtotals

|

($5,591.6)

|

($5,453.7)

|

($5,686.2)

|

($232.5)

|

(4.3%)

|

|

Categorical Programs

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Academic Senate

|

$0.3

|

$0.5

|

$0.5

|

—

|

—

|

|

Adult Education planning grants

|

—

|

25.0

|

—a

|

–$25.0

|

–100.0%

|

|

Apprenticeship (community colleges)

|

7.2

|

7.2

|

7.2

|

—

|

—

|

|

Apprenticeship (school districts)

|

—

|

15.7

|

15.7

|

—

|

—

|

|

CalWORKs student services

|

26.7

|

34.5

|

34.5

|

—

|

—

|

|

Campus child care support

|

3.4

|

3.4

|

3.4

|

—

|

—

|

|

CTE Pathways Initiative

|

48.0

|

48.0

|

—b

|

–48.0

|

–100.0

|

|

Disabled Students Program

|

69.2

|

84.2

|

84.2

|

—

|

—

|

|

Economic and Workforce Development

|

22.9

|

22.9

|

22.9

|

—

|

—

|

|

EOPS

|

73.6

|

88.6

|

88.6

|

—

|

—

|

|

Equal Employment Opportunity

|

0.8

|

0.8

|

0.8

|

—

|

—

|

|

Financial Aid Administration

|

71.0

|

67.5

|

67.9

|

0.4

|

0.5

|

|

Foster Parent Education Program

|

5.3

|

5.3

|

5.3

|

—

|

—

|

|

Fund for Student Success

|

3.8

|

3.8

|

3.8

|

—

|

—

|

|

Nursing grants

|

13.4

|

13.4

|

13.4

|

—

|

—

|

|

Online/Technology initiative

|

—

|

16.9

|

10.0c

|

–6.9

|

–40.9

|

|

Part–time Faculty Compensation

|

24.9

|

24.9

|

24.9

|

—

|

—

|

|

Part–time Faculty Office Hours

|

3.5

|

3.5

|

3.5

|

—

|

—

|

|

Part–time Faculty Health Insurance

|

0.5

|

0.5

|

0.5

|

—

|

—

|

|

Physical Plant and Instructional Support

|

—

|

30.0

|

175.0

|

145.0

|

483.3

|

|

Student Success and Support Program

|

49.2

|

99.2

|

299.2

|

200.0

|

201.6

|

|

Student Success for Basic Skills Students

|

20.0

|

20.0

|

20.0

|

—

|

—

|

|

Technical assistance program

|

—

|

—

|

2.5d

|

2.5

|

—

|

|

Telecommunications and Technology Services

|

15.3

|

15.8

|

15.8

|

—

|

—

|

|

Transfer Education and Articulation

|

0.7

|

0.7

|

0.7

|

—

|

—

|

|

Subtotals

|

($459.6)

|

($632.2)

|

($900.2)

|

($267.9)

|

(42.4%)

|

|

Other Appropriations

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

District financial–crisis oversight

|

$0.6

|

$0.6

|

$0.6

|

—

|

—

|

|

Lease–revenue bond payments

|

63.7

|

63.6

|

63.8

|

$0.2

|

0.3%

|

|

Mandate block grant

|

33.3

|

33.3

|

32.8

|

–0.5

|

–1.5

|

|

Mandate reimbursementse

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

|

Proposition 39 (grant and loan program)

|

—

|

50.0

|

39.0

|

–11.0

|

–22.0

|

|

Subtotals

|

($97.6)

|

($147.5)

|

($136.2)

|

(–$11.3)

|

(–7.7%)

|

|

Totals

|

$6,148.8

|

$6,233.5

|

$6,722.6

|

$489.2

|

7.8%

|

Major Proposed Augmentations. The Governor’s budget contains several 2014–15 spending proposals for community colleges. His largest proposals include: $236 million (one–time) to retire all CCC deferrals, $200 million (ongoing) for the SSSP, $175 million (one–time) for the physical plant (maintenance) and instructional support program, and $155 million for enrollment growth. As discussed later, the Governor also proposes a new CCC Chancellor’s Office technical assistance program ($2.5 million Proposition 98 General Fund and $1.1 million non–Proposition 98 General Fund).

Requests Additional Categorical Program Flexibility. The Governor proposes to expand CCC flexibility by allowing districts to reallocate up to 25 percent of funds from three categorical programs that target financially needy and/or academically underprepared students to other programs that serve high–need students. These three programs are California Work Opportunity and Responsibility to Kids (CalWORKs), Extended Opportunity Programs and Services (EOPS), and Student Success for Basic Skills Students.

No Change to Enrollment Fee Levels. The Governor proposes no change to the current enrollment fee amount of $46 per credit unit (or $1,380 for a full–time student taking 30 units). Community colleges continue to offer noncredit instruction at no charge.

Background

Several Factors Influence CCC Enrollment. Under the state’s Master Plan for Higher Education and state law, community colleges operate as open access institutions. That is, all persons 18 years or older may attend a community college. (While CCC does not deny admission to students, there is no guarantee of access to a particular class.) Many factors affect the number of students who attend community colleges, including changes in the state’s population, particularly among young adults; local economic conditions; the availability of certain classes; and the perceived value of the education to potential students.

Enrollment Funds Allocated by CCC Chancellor’s Office Using Specified Formula. In most years, the state provides the CCC system with enrollment growth funds, which the CCC Chancellor’s Office historically has allocated to districts according to a set formula based largely on year–to–year changes in the local high school graduation and adult population rates. In allocating enrollment funding each year, the CCC Chancellor’s Office sets a limit or “cap” on the maximum number of FTE students each district will be funded to serve. (Districts decide the mix of credit and noncredit instruction they offer.) With some exceptions, a district enrolling students above this cap in a given year generally does not receive funding for the “overcap” students. On the other hand, a district that fails to meet its enrollment target in a given year loses the enrollment funds associated with the vacant slots the following year (though state law gives a declining district three years to earn back the lost funds).

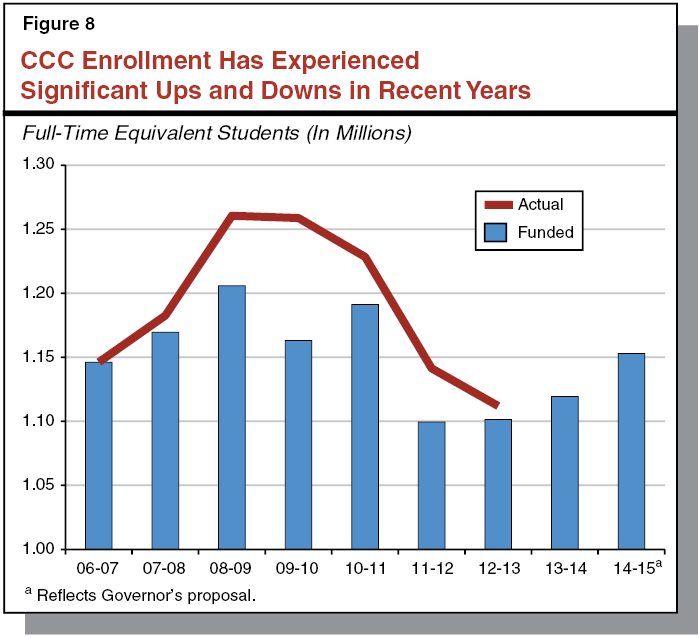

Enrollment Has Fluctuated Notably in Recent Years. Figure 8 displays enrollment trends since 2006–07. As the figure shows, enrollment demand and funding have been highly volatile in recent years. This volatility has stemmed primarily from the state’s economy and budget crisis, as discussed in the nearby box.

California Community Colleges (CCC) Enrollment Trends

Recession Brought Surge of Enrollment Demand. After a few years of modest growth during the mid–2000s, CCC enrollment surged beginning in 2007–08. This was due in large part to individuals choosing to attend college at a time of a tight job market. While the state provided enrollment growth funds in both 2007–08 and 2008–09, the amount was insufficient to accommodate the number of students served by the CCC system. By the end of 2008–09, actual enrollment had exceeded the funded level by over 50,000 full–time equivalent students (FTE) students.

2009–10 Budget Reduced Enrollment Funding. The 2009–10 budget included a $190 million (3.3 percent) cut to CCC apportionments. To maintain the same amount of enrollment funding per student, districts’ 2009–10 enrollment targets were reduced in proportion to the reduction in base apportionment funding. As a result, funded enrollment levels for each district declined by 3.3 percent (43,000 FTE student slots) from 2008–09’s budgeted level. Despite this reduction, the CCC system ended up serving a similar number of FTE students in 2009–10 as in 2008–09 (in large part by increasing class sizes and funding courses using district reserves). By the end of 2009–10, actual enrollment exceeded funded enrollment by about 95,000 FTE students (about 8 percent of funded FTE students). Additionally, as we discussed in The 2010–11 Budget: Higher Education, during this time an unknown but likely significant number of individuals attempted to enroll in courses at CCC but were unable to find an available slot.

Growth Monies in 2010–11 Budget Used to Reduce Enrollment Funding Gap. The 2010–11 budget provided community colleges with $126 million, which the CCC Chancellor’s Office allocated to districts on an across–the–board basis to partially restore the cut from the prior year. Because of the large disconnect between funding and enrollments, districts generally did not use this additional funding to increase the number of students served. Rather, the primary benefit of the new funds was to reduce districts’ gap between funded and actual enrollment.

2011–12 Budget Brought Second Round of Cuts to CCC. The largest reduction to community colleges came in the 2011–12 budget, when community colleges experienced a $385 million base apportionment cut. As with the 2009–10 budget, districts’ enrollment targets were reduced in proportion to this funding cut. As a result, funded enrollment levels in 2011–12 declined by 7.6 percent, or about 90,000 FTE students systemwide. To accommodate this reduction, districts further cut course section offerings. As we discussed in The 2012–13 Budget: Proposition 98 Education Analysis, virtually all types of instruction were affected during this period, with the biggest cuts concentrated in noncredit instruction and courses that were primarily recreational in nature (such as physical education). As a result of these reductions, actual enrollment dropped by 87,000 FTE students in 2011–12.

Recent Growth Funds for Restoration. After the significant base reduction in 2011–12, the 2012–13 Budget Act and 2013–14 Budget Act provided $50 million (0.9 percent) and $89 million (1.6 percent), respectively, in enrollment growth funds. As in 2010–11, these funds were allocated to districts on an across–the–board basis to give districts an opportunity to restore their share of prior–year reductions. In 2012–13, most community colleges met (or even exceeded) their enrollment target, collectively serving 10,000 FTE students above the funded level.

Governor’s Proposals

Proposes Enrollment Growth Funds and Implementation of New Growth Allocation Formula. For 2014–15, the Governor’s budget proposes $155 million for 3 percent enrollment growth (an additional 34,000 FTE students). In addition, the budget requires the CCC Chancellor’s Office to develop a new enrollment growth allocation formula for implementation in the budget year. The Governor’s budget summary describes a growth formula that “gives first priority to districts identified as having the greatest unmet need in adequately serving their community’s higher educational needs. All districts will receive some additional growth funding, and over time will be fully restored to pre–recession apportionment levels.”

Assessment

Information to Date Suggests Enrollment Growth Proposal Likely Too High. Though systemwide enrollment was somewhat above the budgeted level in 2012–13, more than a dozen districts failed to meet their enrollment targets—representing a total of $41 million in unfilled enrollment slots. Based on our discussions with a number of CCCs, this seems to be an increasing trend, whereby more districts are experiencing less demand and having trouble meeting their enrollment targets. (This reduction in demand may be tied at least in part to adults opting for employment as a result of an improved state economy.) As a result, the CCC system realistically may not be able to achieve 3 percent growth in 2014–15. In recognition of this strong possibility, the CCC Board of Governors (BOG) itself has only requested 2 percent enrollment growth ($110 million) for 2014–15.

Existing CCC Growth Allocation Formula Is Flawed. We agree with the Governor that CCC’s enrollment growth allocation formula needs to be revised. Some aspects of the existing formula (such as annual changes in local high school graduates) appear to be reasonably associated with enrollment demand within a CCC district. In other ways, however, the formula is problematic. For example, the formula’s inclusion of changes in the adult population takes into account adults of all ages—regardless of whether they are young adults or seniors of retirement age. This lack of differentiation may overstate CCC enrollment demand in areas with growing older–adult populations and understate demand in areas with a comparatively younger adult demographic.

Revised CCC Growth Formula Must Align With Adult Education Initiative. In addition, given the state’s current effort to restructure adult education, the Legislature will want to ensure the formula used to fund CCC enrollment growth is well aligned with the formula used to fund growth in adult education. Between 2013–14 and 2014–15, community colleges and school districts (through their adult schools) are conducting local needs assessments of adult education services (such as English as a second language instruction) and developing plans for integrating existing programs. The 2013–14 budget package includes intent language for the Legislature to appropriate new Proposition 98 funds in 2015–16 to expand adult education in the state, but the methodology for allocating such funds to adult education providers has not yet been determined. The Legislature will want to ensure the new funding formulas for adult education and apportionments are well tailored to their respective missions.

Recommendations

Use Better Information in Coming Months to Make Decision on Growth Funding. By late February, the CCC Chancellor’s Office will have systemwide and district–level data on enrollment trends in the current year. These data will show the extent to which districts are meeting, exceeding, or falling short of their enrollment targets in the current year. The Legislature will need to carefully assess these data to evaluate the need for an additional 3 percent enrollment growth in the budget year. If it decides the entire $155 million is not justified, the Legislature could use any associated freed–up funds for other Proposition 98 priorities.

Postpone Implementation of New Formula Until 2015–16 but Request Periodic Updates on Its Development. We recommend the Legislature reject the Governor’s proposal to have a new formula in place for 2014–15 and instead give the CCC Chancellor’s Office a reasonable period of time to develop a new allocation formula. During spring hearings, the Legislature could request the CCC Chancellor’s Office and DOF to share their initial ideas for the new enrollment growth allocation formula. In addition, the Legislature could request the CCC Chancellor’s Office and CDE to provide a list of potential growth allocation factors for adult education. Given the complexity of these two efforts and the need to ensure coordination, the Legislature likely will want to request additional status updates from the CCC Chancellor’s Office and CDE periodically throughout 2014. (A final plan probably will need to be adopted by December 2014, when preparation for the 2015–16 budget is occurring.)

Release 2014–15 Enrollment Growth Funds on Across–the–Board Basis. Given that a new CCC growth formula and new adult education allocation formula likely will not both be developed for a number of months, we recommend the Legislature direct the CCC Chancellor’s Office to allocate any 2014–15 enrollment growth funds to districts on an across–the–board basis. (The Legislature could use the new formulas thereafter.)

Background

In 2013–14, the community colleges are receiving $632 million in categorical funding. The majority of these categorical monies (about $400 million in 2013–14) fund various student support services—ranging from financial aid advising to campus child care to specialized assistance for students with disabilities. (The remaining CCC categorical programs serve various purposes unrelated to student support services, such as facilities maintenance and technology initiatives.) Figure 9 lists CCC’s eight student support categorical programs.

Figure 9

Community Colleges Have Eight Student Support Categorical Programs

|

Categorical Program

|

Description

|

|

Extended Opportunity Programs and Services (EOPS)

|

Provides various supplemental services (such as counseling, tutoring, and textbook purchase assistance) for low–income and academically underprepared students. (A subset of EOPS serves welfare–dependent single parents.)

|

|

Fund for Student Success

|

Consists of three separate programs: two programs that provide counseling, mentoring, and other services for CCC students from low–income or historically underrepresented groups who seek to transfer to a four–year college; and one program for students who attend high school on a CCC campus.

|

|

Student Success and Support Program

|

Funds assessment, orientation, and counseling (including educational planning) services for CCC students.

|

|

Student Success for Basic Skills Students

|

Funds activities such as counseling and tutoring for academically underprepared (basic skills) students, and curriculum and professional development for basic skills faculty.

|

|

Financial Aid Administration

|

Funds staff to process federal and state financial aid forms and assist low–income students with applying for financial aid.

|

|

CalWORKs student services

|

Provides child care, career counseling, subsidized employment, and other supplemental services to CCC students receiving CalWORKs assistance. (These services are in addition to those provided to all CalWORKs recipients by county welfare departments.)

|

|

Campus child care support

|

Funds child care centers at 25 community college districts. (This child care is unique to these 25 districts and not part of the state’s CalWORKs child care program.)

|

|

Disabled Students Program

|

Provides educational accommodations (such as sign language interpreters, note takers, and materials in braille) and other specialized support services for students with disabilities.

|

Categorical Program Funding Cut in 2009–10. In response to the state’s fiscal condition, the 2009–10 Budget Act reduced ongoing Proposition 98 General Fund support for CCC’s categorical programs by $263 million (37 percent) compared with 2008–09. Of this amount, a total of $181 million (38 percent) was cut from student support categorical programs. Of CCC’s eight student support categorical programs, two programs received a base cut of about 50 percent, five programs were cut roughly 40 percent, and one (Financial Aid Administration) received a slight augmentation.

2009–10 Reductions Accompanied by Some Flexibility. To help districts better accommodate these reductions, in 2009–10 the state combined more than half of CCC’s categorical programs (including two student support categorical programs) into a “flex item.” Through 2014–15, districts are permitted to use funds from categorical programs in the flex item for any categorical purpose. (Such decisions must be made by local governing boards at publicly held meetings.) By contrast, funding for categorical programs that are excluded from the flex item must continue to be spent on specific associated statutory and regulatory requirements. For example, funds in the campus child care program (within the flex item) may instead be spent on CCC’s CalWORKs program (outside the flex item), though CalWORKs categorical funds can only be spent for that program.

CCC Task Force Identifies Student Supports as Key Priority. It was during this period of categorical program cuts and flexibility that the Legislature and CCC system began rethinking the role of support services as they relate to student achievement. In response to ongoing concerns about low CCC completion rates, the Legislature passed Chapter 409, Statutes of 2010 (SB 1143, Liu). The legislation required the BOG to adopt and implement a plan for improving student success. It also required the BOG to create a task force to develop recommendations for inclusion in the plan. In response to the legislation, the board created the Student Success Task Force, comprised of 21 members from inside and outside the CCC system. After meeting for nearly one year, the task force released Advancing Student Success in California Community Colleges in December 2011. The report contained a number of recommendations, including establishing statewide enrollment (registration) priorities and creating a CCC “scorecard” that disaggregates student performance outcomes by racial/ethnic group. A key focus of the report was on the need to strengthen support services for students. In particular, the report stressed the importance of helping incoming students identify their specific educational goals as early as possible and develop a course–taking plan to reach those goals. To that end, the task force report highlighted the importance of CCC’s Matriculation program, which funds assessment, orientation, and counseling (including educational planning) services.

Legislature Backs New Student Success and Support Program. The BOG endorsed the Student Success Task Force’s report recommendations in January 2012 and presented its plan to the Legislature shortly thereafter. In an effort to implement the task force’s recommendations on student support, the Legislature passed Chapter 624, Statutes of 2012 (SB 1456, Lowenthal). Chapter 624 contained a number of provisions, including: (1) renaming the Matriculation program the SSSP; (2) requiring the BOG to establish policies around mandatory assessment, orientation, and educational planning for students; (3) calling for additional funding for SSSP; (4) requiring the BOG to develop a new methodology for allocating SSSP funds—from the current allocation model based solely on student enrollment to a new model based on factors such as the number of students developing an education plan; and (5) requiring each community college to create an SSSP plan. The SSSP plans are to contain information such as how colleges identify students who are “at risk” of academic probation and the strategies colleges use to help these students. The SSSP plans are to be coordinated with colleges’ student equity plans. (Student equity plans, which CCC regulations require each college to develop, identify enrollment and achievement gaps among certain demographic groups and include strategies for closing the gaps.)

2013–14 Budget Augments Funding for SSSP and Other Support Programs. After receiving a 50 percent cut in the 2009–10 budget, the 2013–14 Budget Act provided a $50 million increase for SSSP. This increase represented a doubling of base funding for the program. The budget also contained smaller increases for three other student support categorical programs—the Disabled Students Program, EOPS, and CalWORKs.

Governor’s Proposal

Increases Funding for SSSP by $200 Million. For 2014–15, the Governor proposes a $200 million augmentation to SSSP, which would triple the current–year funding level for the program. Of the $200 million, $100 million would be allocated to districts in support of all students, consistent with existing practice. The remaining $100 million would be allocated to districts specifically to serve “high need” CCC students. The Chancellor’s Office would be tasked with defining what constitutes high need as well as with developing a methodology for allocating these monies to districts. The Governor’s intent is for districts to use these additional funds to provide supplemental support services—beyond the base services provided by regular SSSP dollars—to reduce any student achievement gaps identified in colleges’ student equity plans. In addition, as a condition of receiving these supplemental SSSP funds, CCCs must explain in their student equity plans how they will improve coordination among the various student support categorical programs so as to improve service to high–need students.

Gives Partial Flexibility to Three Other Categorical Programs. In addition, the budget would permit districts to reallocate up to 25 percent of funds from three other student support categorical programs (CalWORKs, EOPS, and Student Success for Basic Skills Students) to other programs that serve high–need students.

Assessment

Governor’s Intent to Increase Funding for Student Support Is Laudable . . . Over the past several years, a number of reports have highlighted the relatively low success rates for CCC students. For example, the Institute for Higher Education Leadership and Policy has found that only about one–third of CCC students who seek to transfer or graduate with an associate degree or certificate actually do so. As a result of data such as these, the Legislature has shown a strong interest in improving student outcomes and, through legislation such as Chapter 624 and budget actions, has identified student support services—particularly SSSP—as a key means of improving student success. Given these factors, the Governor’s overarching goal of enhancing student supports is appropriate.

. . . Though Specific Funding Proposal Falls Short of Fully Addressing Student Needs. We have concerns, however, that the Governor’s emphasis on SSSP is too narrowly focused. As state and national research has shown, students often need a variety of support to succeed. Different types of students may need different support services and many students need multiple types of support that extend beyond assessment, orientation, and counseling. For example, a student with a learning disability (such as dyslexia) may require specialized assistance. A low–income student may need access to financial aid advising and orientation services. Our review of several student equity plans shows strategies that colleges themselves have recommended for implementation (such as the formation of small learning communities and additional professional development) extend beyond SSSP–funded activities. By placing the entire $200 million augmentation in SSSP, the Governor would limit the ability of CCCs to provide a more comprehensive set of effective services to students.

Additional Flexibility Proposed by Governor Moves In the Right Direction . . . We think the Governor’s stated goal of increasing coordination among CCC’s various student support categorical programs is laudable. As we have pointed out in past analyses, community college categorical programs tend to be highly prescriptive in terms of how funds can be spent. By requiring districts to spend funds for a specific purpose, categorical programs limit local flexibility to direct and combine funding in ways that address student needs most effectively and efficiently. (The Student Success Task Force came to a similar conclusion in its report, writing that “…the current approach results in organizational silos that are inefficient and create unnecessary barriers for students in need of critical services and detract from the need for local colleges to have control and flexibility over their student outcomes and resources.”) Categorical funds also are costly for districts and the CCC Chancellor’s Office to administer. Districts must apply for, track, and report the appropriate use of categorical funds, and the Chancellor’s Office must oversee districts’ compliance with numerous statutory and regulatory requirements. For all these reasons, we agree with the Governor that additional categorical flexibility is needed.

. . . But Specific Proposals Are Too Limited. We are concerned, however, that the Governor’s flexibility proposals do not go far enough. In particular, by proposing just partial flexibility for CalWORKs, EOPS, and Student Success for Basic Skills Students—and no flexibility for other support programs such as Financial Aid Administration and Fund for Student Success—the Governor’s approach would give community colleges only limited ability to tailor categorical services in ways that meet local needs.

Recommendations

Create CCC Student Support Block Grant. We recommend the Legislature consider providing greater flexibility to districts. A restructuring approach our office has recommended in the past is to consolidate categorical programs into broad thematic block grants. Block grants ensure that districts continue to invest in high educational priorities, while providing flexibility for districts to structure their programs in pursuit of these goals. For community colleges, we recommend the Legislature consolidate seven of CCC’s eight student support programs (excluding the Disabled Students Program) into a new Student Support block grant. (This consolidation would reduce state–level administrative work, thereby likely freeing up several positions and a few hundred thousand dollars in non–Proposition 98 General Fund within the Chancellor’s Office budget.) If the Legislature were to provide the Governor’s proposed $200 million augmentation for the block grant (rather than entirely for SSSP), total funding for the block grant would be $517 million in 2014–15.

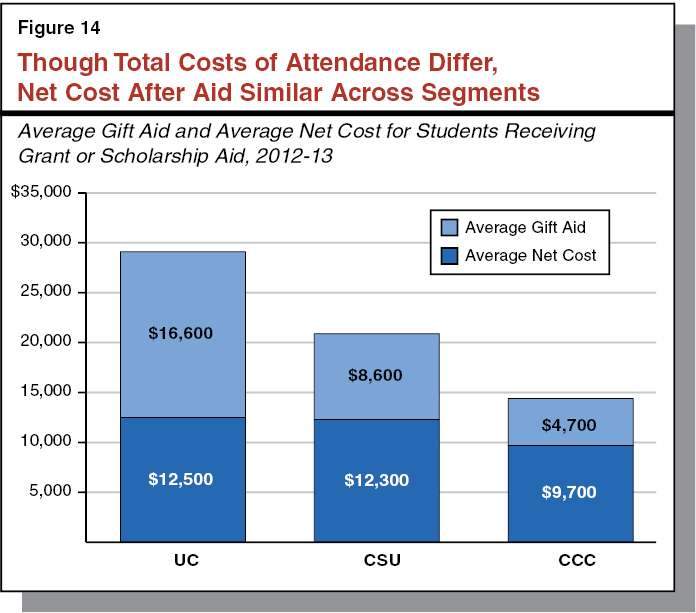

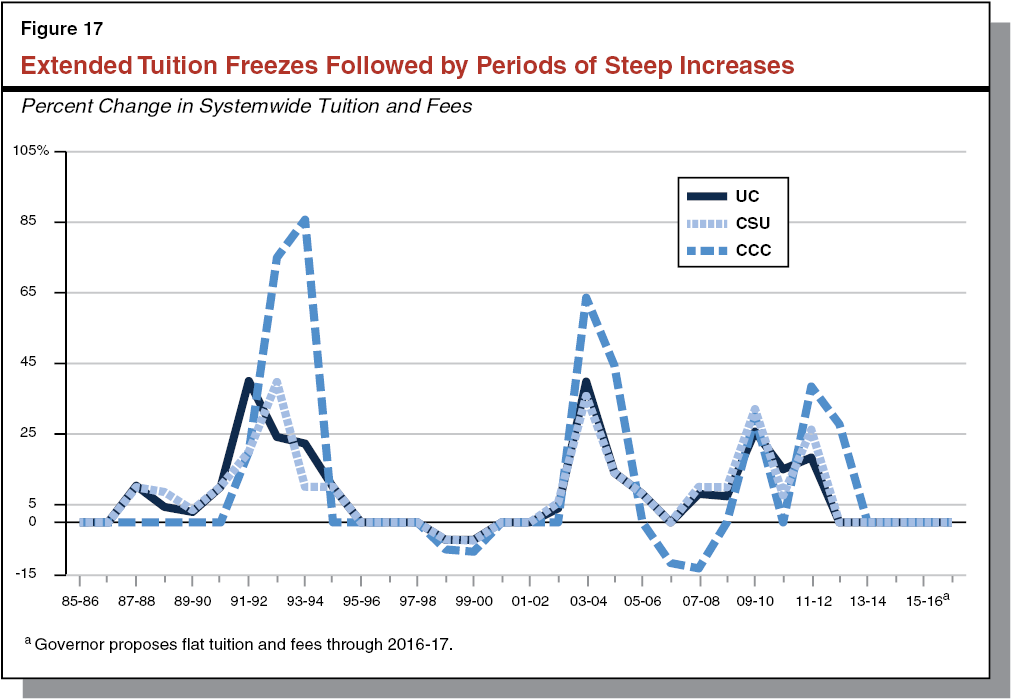

By combining funding for these programs into one block grant, community colleges would be able to allocate funding in a way that best meets the needs of their students—without being bound to specific existing programmatic requirements. With this funding, for example, districts could provide “wraparound” services such as assessment, orientation, counseling, financial aid advising, child care, tutoring and other activities designed to improve student completion. A block grant approach also could help districts operate their services more efficiently, such as by consolidating categorical programs’ various counseling functions (now provided through SSSP, Student Success for Basic Skills Students, the Fund for Student Success, and EOPS, among other programs). In addition, a block grant approach would be a more lasting option for providing districts flexibility (as the current flex item is scheduled to sunset at the end of 2014–15.)