Executive Summary

The Supplemental Report of the 2010–11 Budget Act directed our office to study school district consolidations and determine whether the state should more actively promote consolidating small districts into larger districts. Currently, about 40 percent of public school districts in California are "small" (serving fewer than 1,000 students), and about 10 percent of all districts are "very small" (serving fewer than 100 students). Under state law, minimum district size is very low—average daily attendance (ADA) of six for an elementary district and 11 for a high school or unified district. Under state law, California also currently leaves the decision over whether to consolidate school districts up to local communities, with local stakeholders required to initiate the consolidation process and ultimately a majority of the local electorate required to approve the merger.

Assessing the Merits of Consolidation. In this report, we investigate the competing claims made in support and opposition of consolidation. Whereas proponents of consolidation argue that combining smaller districts into larger districts would lead to savings, more overall efficiency, and a better academic experience for students, opponents of consolidation suggest that small districts already operate efficiently, offer an enhanced educational experience for students, and are important components of local communities. To analyze the merit of these contrasting claims, we compare fiscal and student outcome data for districts of different sizes.

Slight Differences in Spending Patterns and Student Performance in Small Districts, Notable Issues for Very Small Districts and Schools. Our review finds that while small districts tend to spend more on overhead costs and have slightly lower student achievement compared to midsize districts, the differences are not large. We find that the operational demands and limitations of being very small, however, are substantial. Specifically, compared to larger districts, very small districts tend to dedicate a significantly bigger share of their budgets to covering overhead costs and a smaller share to instructional staff and leaders. Moreover, very small districts are more difficult to hold accountable for student outcomes because their small enrollments do not yield statistically significant results. This is also a problem for very small schools.

Substantial Funding Advantages and Certain Disincentives Keep Small Districts From Opting for Consolidation. Despite some inherent challenges, small districts still tend not to pursue consolidation. In large part, we find this is because the state provides both fiscal incentives for districts to remain small and certain disincentives for districts to consolidate. Specifically, the state encourages districts (and schools) to remain small by providing them substantial funding advantages. These benefits are especially evident in very small school districts, which on average receive more than twice as much funding per pupil compared to midsize and large districts. Additionally, certain state laws, including those related to environmental reviews and district staffing, coupled with community preferences for small districts, serve as disincentives for districts to consolidate.

Recommend State Maintain Locally Based Decision–Making Structure...Neither the academic research nor our own review offers persuasive evidence that consolidating small districts would necessarily result in substantial savings or notably better outcomes for students. Thus, we recommend the state neither force all small districts to consolidate nor provide special fiscal incentives (particularly given the state's current budget problems) to encourage such consolidation. Instead of a one–size–fits–all response to school district configuration, we recommend the state generally maintain California's long–standing policy of letting local constituencies decide how to best structure their local districts.

…But Make Important Changes to Encourage Efficiencies and Improve Accountability. While our findings suggest the state has little justification for requiring all small districts to consolidate, they also suggest the state should not discourage districts from consolidating. Specifically, we recommend the state eliminate the substantial fiscal advantages that enable districts to remain small, often as single–school districts—particularly since we find little proof that being small leads to better student outcomes. We also recommend the state remove existing disincentives for districts to consolidate, including those related to environmental reviews and district staffing. In addition to removing both the fiscal incentives to remain small and the disincentives to consolidate, our review indicates that extreme inefficiencies and concerns about accountability do justify changing state policy regarding very small districts and schools. Specifically, we recommend the state increase the minimum threshold for districts to at least 100 students and consider establishing a minimum size for schools.

Introduction

The state's recent budget problems have prompted the Legislature to consider various ways to reduce costs for K–12 education. One frequently mentioned idea involves consolidating small school districts into larger districts. The Supplemental Report of the 2010–11 Budget Act directed our office to examine this issue.

In this report, we investigate the competing claims made in support and opposition of district consolidation. Proponents of consolidation claim that small districts lack economies of scale and, as a result, inherently face higher costs per pupil and are unable to offer the range of curricular opportunities available to students who attend larger districts. As such, some argue that combining smaller districts into larger, consolidated districts would lead to savings, more overall efficiency, and a better academic experience for students. Additionally, some emphasize that having fewer school districts would make state management and oversight easier, better, and less costly. In contrast, opponents of consolidation suggest that small districts not only find ways to operate efficiently but also offer an enhanced and personalized educational experience for students. Moreover, because many small districts are located in rural areas, some argue they are important and necessary components of those local communities.

This report first provides some background information on California's and other states' experiences with district consolidations. We then compare fiscal and student outcome data for districts of different sizes, and discuss our associated findings regarding the merit of the various claims made in support and opposition of consolidation. Lastly, we offer recommendations for how the Legislature could provide better fiscal incentives and stronger accountability for small districts and schools. (The Supplemental Report also requested that we examine options for greater regionalization of county offices of education [COEs]. Please see the Appendix for this discussion.)

Background

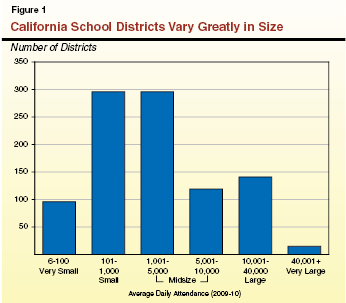

Size of California School Districts Varies Dramatically. As shown in Figure 1, California's nearly 1,000 school districts vary greatly in size. The state has a very low threshold for minimum district size—ADA of six for an elementary district and 11 for a high school or unified district. As a result, the state has an exceptional number of small districts. Almost three–quarters of all California school districts have fewer than 5,000 ADA. However, together these 688 districts contain just 15 percent of total ADA in the state. Moreover, 230 of the state's districts contain only a single school. At the other extreme, 15 very large districts with over 40,000 ADA educate about one–quarter of all students in the state, with one district—Los Angeles Unified—representing about ten percent of total state ADA.

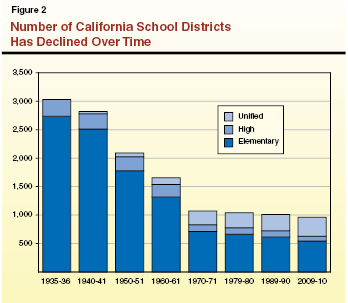

Historically, State Has Encouraged Districts to Consolidate, Reducing the Overall Number of Districts. Although California continues to have many small school districts, the total number of districts in the state has declined over time. Figure 2 shows the number of school districts in the state by type—elementary, high, and unified—over the past 75 years. As shown in the figure, the state has about half as many districts as it did 50 years ago (963 in 2009–10 compared to 2,091 in 1950–51), largely due to state efforts to encourage district consolidation. Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, the state provided a series of fiscal incentives for consolidation, including increasing the per–pupil funding rate for unified districts and paying for excess costs of student transportation associated with merging school districts. One piece of legislation—Chapter 132, Statutes of 1964 (AB 145, Unruh), since repealed—expressly stated legislative intent to form unified K–12 school districts and "that this form of organization be ultimately adopted throughout the state." Correspondingly, as shown in the figure, these years reflect the most dramatic drop in the overall number of districts and increase in the number of unified districts. The figure also shows that the pace of consolidation has slowed in recent decades since the state stopped providing explicit incentives for districts to unify.

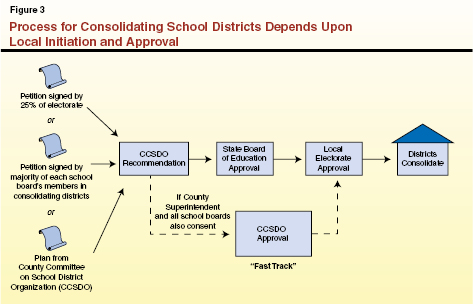

Decision to Consolidate School Districts Resides Primarily at Local Level. While the state has provided some fiscal incentives for districts to consolidate and the State Board of Education (SBE) typically weighs in on consolidation applications, the state delegates most district configuration decisions to the local level. State law calls for each county to establish a County Committee on School District Organization (CCSDO), made up of county school board members or their designees, to facilitate and coordinate any attempts to consolidate school districts. As shown in Figure 3, local stakeholders must initiate the process of consolidating school districts—either through citizen petition, agreement amongst affected school boards, or plan from the CCSDO—and ultimately a majority of the local electorate must vote to approve the consolidation. In 2009, the Legislature authorized a "fast track" process by which the CCSDO could approve the consolidation application in lieu of the SBE—provided the County Superintendeant of Schools and a majority of each affected local school board concurs with the proposal—with the final decision still subject to voter ratification. To be approved, the application must demonstrate that the consolidation would not have a negative effect on the districts' student populations, facilities, educational programs, or local communities.

Some Other States Have Recently Adopted More Assertive Consolidation Policies. In contrast to California's locally based approach to district configuration, some other state governments recently have implemented more assertive state–level policies to consolidate small school districts. One of the most sweeping examples is Maine, which in 2007 passed legislation requiring that all school districts enroll at least 2,500 students or face fiscal penalties (with an adjusted minimum of 1,000 students for geographically isolated districts). In the subsequent three years, the number of Maine school districts has dropped by one–third, from 290 to 179, although about half of the smaller districts in the state (representing about 10 percent of all students) have not yet conformed to the consolidation mandate. Several other states, including Arkansas and Vermont, have also recently passed legislation to encourage school district consolidation.

Findings

To assess the potential benefits of district consolidation, we analyze operational costs and performance data for districts grouped by size. Figure 4 summarizes our primary findings. We find some evidence indicating small school districts (those that serve 1,000 or fewer students) have higher per–student operational costs. We also find that small districts and schools are more difficult to hold accountable for student outcomes. Despite these challenges, small districts still tend not to pursue consolidation. In large part, we find this is because the state not only allows but also encourages both districts and schools to remain small by providing them substantial funding advantages. These findings are especially evident in very small school districts (those that serve 100 or fewer students).

Figure 4

Summary of Major Findings

|

|

- Small districts find ways to economize but still face fiscal and personnel challenges.

|

- District size has some effect on student performance, but very small districts are difficult to monitor.

|

- Small districts have substantial funding advantages.

|

- Disincentives keep school districts from consolidating.

|

- Very small schools also are enabled by extra funding and lack accountability.

|

Small Districts Find Ways to Economize but Still Face Fiscal and Personnel Challenges

Small districts claim they employ a number of creative arrangements such that they already achieve some of the fiscal benefits typically sought through consolidation. Our research reveals some support for this assertion. We find that small districts typically pool their funding with other local educational agencies to generate economies of scale, and they often maximize their limited staff resources so that fewer personnel are necessary. However, we also find that the operational demands and limitations of being small, particularly very small, are substantial and can constrain the resources these districts are able to dedicate to instruction.

Small Districts Create Economies of Scale Through COEs and Consortia. Most state and federal school funding formulas are based on student counts—that is, they provide school districts with a certain amount of funding for each pupil that they serve. Districts combine these funding streams in various ways to pay for their administrative, instructional, and operational services. Because districts with smaller enrollments do not generate considerable amounts of overall funding through per–pupil formulas, many small districts pool their resources with other districts and COEs to achieve the economies of scale they lack on their own, particularly for noninstructional activities. Although these arrangements differ across the state, Figure 5 displays some of the administrative and support services most commonly shared among districts. Some extremely small districts also share superintendents and/or business officials. Additionally, COEs coordinate instructional support services for their local districts, including curriculum development, professional development, and services for special populations of students. (The state provides additional "direct service" funding to COEs to offer more intensive assistance to smaller districts that have fewer internal resources.) While natural fiscal incentives exist for this type of economizing, differing circumstances and desire for local control mean not every small district chooses to pool resources to the degree one might expect.

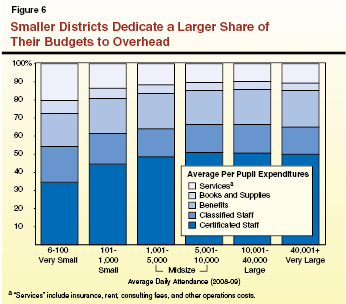

Despite Partnerships, Very Small Districts Spend Larger Proportion of Funding on Overhead. Even after strategizing to pool resources as much as possible, inherent diseconomies of scale typically require that small districts, and especially very small districts, dedicate a larger share of their budgets to covering overhead costs and a smaller share to instruction. Specifically, Figure 6 shows that very small districts spend, on average, about 35 percent of their per–pupil allotments on instruction and instructional support (certificated staff, including teachers and administrators) and 40 percent on overhead (including classified staff such as clerical and maintenance employees, and "services" or basic operational costs). By comparison, districts with over 1,000 students typically spend, on average, about half of their allotments on instruction and about 25 percent on overhead. These findings suggest that even though small school districts typically receive generous funding advantages (as described later), their operational requirements tend to limit the share of funding that can be dedicated to instruction.

Small Districts Multi–Task, but Not Without Affecting Instructional Programs. One way that small districts manage these budget limitations is to "stretch" the responsibilities of their certificated staff, having one employee fulfill responsibilities that normally would be tasked to several different people at a larger district. For example, it is not uncommon for the superintendent of a very small district to simultaneously serve as principal, budget officer, and teacher. Proponents for small districts highlight this as an efficient use of staff resources, arguing that consolidating small school districts could actually result in higher costs based on the need to hire additional staff to accomplish these numerous jobs. Nevertheless, interviews with affected superintendents suggest that juggling innumerable administrative responsibilities makes dedicating sufficient time to instructional leadership difficult. While multi–tasking may be efficient—and essential—for small school districts, it may not always be the most effective use of staff skills and expertise. Furthermore, fewer staff means more limited opportunities for professional collaboration and peer–to–peer learning compared to districts that employ larger cadres of teachers.

District Size Has Some Effect on Student Performance, but Very Small Districts Are Difficult to Monitor

One argument for consolidating small school districts is that the limitations of their academic programs—such as multigrade classrooms and less variety in upper–division coursework—result in an inferior education for students. While our review of California student performance data and the relevant academic literature indicates some correlation between district size and student outcomes, the evidence does not show especially strong support for the assumption that small districts inherently are worse for students. However, we are concerned that state and federal accountability systems cannot draw meaningful conclusions about student performance in very small school districts.

Student Performance Appears Slightly Better in Midsize Districts. Our review of data from the 2010 Academic Performance Index (API) suggests that, after controlling for student characteristics, midsize school districts (2,000 to 10,000 students) have, on average, better student performance than smaller districts (under 2,000 students). The difference, however, is slight, with smaller districts scoring only six API points lower than midsize districts. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the data suggest that midsize districts also outperform exceptionally large districts. These findings are consistent with academic research, which has shown that districts with 2,000 to 6,000 students tend to outperform other school districts. The policy implications of this research, however, are complicated. Most notably, researchers suggest that school size may be driving some of the student performance trends, with students in smaller schools outperforming their peers (which could partially explain the findings for exceptionally large districts, as they also tend to contain exceptionally large schools).

Very Small Districts Much Harder to Hold Accountable for Overall Student Outcomes. While our review of API data suggests that smaller school districts perform only slightly worse than midsize districts, we have concerns that these data do not tell the whole story. This is because the number of students being tested in very small districts is too small to ensure results are statistically accurate. State API reports display scores for very small districts with an asterisk, indicating the scores are of questionable reliability. In a slightly different approach, federal performance targets are adjusted for districts with fewer than 100 test–takers. Given the statistical uncertainty associated with their scores, very small districts are allowed additional latitude for meeting federal accountability benchmarks. For example, a district with 50 test–takers can meet a 55 percent federal proficiency target with only 19 students (or 38 percent) scoring at the proficient level. These issues raise questions as to whether the local community, as well as state and federal governments, truly are getting an accurate reflection of student achievement in very small districts.

Smaller Districts Also Not Accountable for Important Subgroups of Students. In addition to overall district performance, most school districts are held accountable for the outcomes of particular subgroups of students, including economically disadvantaged students, English learners, and students with disabilities. However, the state does not hold districts accountable for subgroup performance if they have fewer than 100 students overall or 50 students in a particular subgroup because these groups do not have numerically significant populations. As such, these districts do not face performance targets, monitoring, or sanctions related to how these specific student populations may perform. This is another example of how the state and federal accountability systems do not fully apply to smaller districts, making it difficult for the state to monitor and intervene if a district is struggling to meet the needs of certain student populations.

Small Districts Have Substantial Funding Advantages

As discussed, many small school districts argue that consolidation would offer them few fiscal benefits because they already maximize resources through consortia and creative arrangements. However, our review of district fiscal data suggests it is more than these partnerships that enable small school districts to operate even without economies of scale. Specifically, we find that the state and federal governments provide substantially more funding per pupil to smaller school districts compared to larger districts. It is these fiscal advantages that allow small districts to opt against consolidation.

Small Districts Receive Special Fiscal Allowances. As noted earlier, per–pupil funding formulas may not generate sufficient revenue to support even basic school operations at very small districts. For example, the state's general purpose funding formula—known as "revenue limits"—provides districts with roughly $5,000 per student. For a district with fewer than 40 students, this formula would generate less than $200,000 to cover salary and benefits for district personnel and all of the district's overhead costs—an unworkable amount. In acknowledgement that they generally lack economies of scale and cannot stretch per–pupil allocations to cover all of their costs—even with the creative arrangements described earlier—the state and federal governments provide extra funding for small districts. Figure 7 describes some of these special fiscal allowances. Given the proportion of funding they already spend on operational costs, it seems certain that many small districts—particularly very small districts—could not afford to operate without these significant funding advantages.

Figure 7

Special Fiscal Allowances for Small School Districts

2009–10

|

Allowance

|

Description

|

Number of Districts Receiving

|

Statewide Total (In Thousands)

|

Average Per–Pupil Amount

|

|

Necessary small school supplement

|

Provides higher fixed grant amounts instead of per–pupil revenue limits to small districts that contain small schools.

|

144

|

$39,773a

|

$7,300a

|

|

Categorical program minimum grants

|

Provides higher fixed grant amounts instead of the normal per–pupil allocation to small districts.b

|

Varies by program

|

Varies by program

|

Varies by program

|

|

Federal Small Rural Schools Achievement Fund

|

Provides additional funding to districts with under 600 students that are located in rural areas (federally funded).

|

281

|

5,606

|

257

|

|

County direct services

|

Funds COEs to provide additional services to small districts free of charge.c

|

397

|

7,987

|

61

|

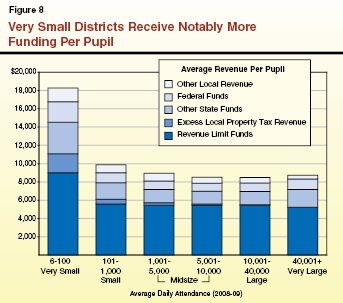

Very Small Districts Receive Notably More Per Pupil Compared to Other Districts. Due primarily to these additional allowances, very small school districts receive substantially more funding per pupil than do larger districts. Specifically, as shown in Figure 8, districts with fewer than 100 students receive, on average, more than $18,000 per enrolled student, or more than twice as much as districts that enroll at least 1,000 students. They receive more revenue from each of their funding sources—revenue limits (due primarily to the necessary small school [NSS] supplement discussed later in this report), excess property taxes (discussed in the nearby box), federal funds, other state funds (mostly reflecting categorical program funding), and other local revenues (including fees, interest, and parcel tax revenues). Compared to larger districts, small districts with somewhat larger enrollments (between 100 and 1,000 students) also receive more per pupil across all funding categories, but to a much lesser degree than very small districts.

Charter Schools Differ From Small Districts. One of the frequently asked questions we faced while researching this report was whether there is a contradiction in the state investigating options for consolidating smaller school districts while simultaneously continuing to allow districts and independent operators to open new, often small, charter schools. While there may be some overlapping policy concerns, we believe there are several key differences between small school districts and charter schools. First, in contrast to the special fiscal allowances it provides to smaller districts, the state does not offer special, higher funding rates to charter schools. Second, in many cases, charter schools are more similar to other schools than districts, in that they have a larger oversight entity handling administrative responsibilities and generating economies of scale (either the authorizing district/COE or a charter school management organization). Third, while it may be hard to hold very small charter schools accountable for student outcomes at the school level, performance for locally funded charter schools is accurately tracked within the district–level systems as long as their authorizing district/COE is large enough to yield statistically significant data. (Direct–funded charter schools are not included in district–level performance results, and therefore those that are very small are affected by some of the same accountability problems as very small school districts.) Finally, the authorizing entity has the authority to close a low–performing or fiscally unsound charter school, whereas the state generally does not have this option for a similarly struggling school district. As such, we believe that fiscal and policy concerns regarding small school districts are somewhat distinct from those related to charter school oversight and accountability.

Many Small School Districts Supported by Excess Local Property Tax Revenues

While not a fiscal allowance created specifically for small districts, excess local property tax revenues play an important role in financing small districts in many areas of the state. This fiscal advantage further enables small districts to opt against consolidation.

Most California school districts receive general purpose funding (or revenue limits) from a combination of local property tax revenues and state aid. In some areas of the state, however, property tax revenues alone exceed the district's per–pupil revenue limit entitlement. These districts can keep the "excess" local revenue and use it for any educational purpose. This occurs in districts that have highly valued property within their boundaries—such as nuclear power plants, oil wells, large receipts of timber taxes, or very expensive homes—and, in most cases, relatively smaller student enrollments across which to spread these revenues. In 2009–10, there were 120 such districts in the state, with excess property tax revenues ranging from $10 per pupil to over $26,000 per pupil. These districts, commonly referred to as "basic aid districts," tend to be smaller—about 85 percent served fewer than 5,000 students, and 20 percent served fewer than 100 students. Moreover, in general, the fewer students the district served the more excess revenue it received per pupil. Very small basic aid districts (serving fewer than 100 students) received an average of almost $8,600 in excess tax revenues per pupil, compared to about $4,600 for small basic aid districts (between 100 and 1,000 students) and about $2,800 for midsize basic aid districts (between 1,000 and 5,000 students).

|

Disincentives Keep School Districts From Consolidating

In addition to the fiscal advantages that help some districts remain small and opt against consolidation, we find several other disincentives for districts to consolidate. Perhaps most importantly, under existing state laws, districts can experience other funding losses and some higher costs if they consolidate. The extensive process and uncertain outcomes of consolidation also function as disincentives. In addition, strongly entrenched community preferences for school districts to remain small can thwart consolidation efforts.

Consolidating Can Lead to Loss of Funding and Additional Costs. In addition to losing funding, consolidating can lead to higher costs for districts, both in the short term (such as the administrative costs of the consolidation process) and longer term (such as the pressure to increase staff compensation to match that of the most generous consolidating district). Figure 9 summarizes potential fiscal disincentives for a district considering consolidation. While the state provides some funding to assist consolidating districts—including providing an ongoing revenue limit "bump" to help in blending employee salary schedules, offering short–term loans for start–up costs, and reimbursing some qualifying administrative costs through the state mandate claiming process—it typically is not sufficient to cover all associated costs. Interviews suggest the requirement that many consolidations necessitate a California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA) study can be especially costly.

Figure 9

Potential Fiscal Disincentives to Consolidate

|

|

- Loss of Special Fiscal Allowances. Consolidated districts may become too large to qualify for Necessary Small School supplements, categorical program minimum grants, federal Small Rural Schools Achievement Fund grants, or funded direct services from the county office of education.

|

- Loss of Excess Property Tax Funding. The newly drawn district's jurisdiction might not benefit from as much—or any—"excess" local property tax funds.

|

- Loss of Parcel Tax Revenue. When districts consolidate, any existing parcel taxes for component districts are nullified unless or until the newly formed district's electorate reauthorizes them.

|

- Lower Base Revenue Limit (RL) Rate. A newly consolidated district's RL rate is the weighted average of component districts' RL rates. This means a district with a higher RL rate could see its rate leveled down.

|

- Cost Pressure to Level–Up Salaries and Benefits. Employees typically expect the consolidated district to adopt the most generous compensation package of the component districts. While the state generally gives the consolidated district a RL "bump" to address this issue, it often is not sufficient to fully meet local cost pressures.

|

- Costs of Consolidation Process. Administrative costs associated with consolidation include California Environmental Quality Act studies, conducting analyses and compiling documentation for the application, holding hearings and elections, and the start–up costs associated with running a new district.

|

- Inability to Realize Savings From Potential Efficiencies. Current law prohibits newly formed districts from laying off or reducing the salaries of classified employees from component districts until two years post consolidation.

|

Non–Fiscal Disincentives Can Also Inhibit Consolidation Efforts. In addition to these fiscal disincentives, there are a number of other reasons that districts opt against consolidation. Among these are the local community's perceived benefits of smaller districts, apprehension about the lengthy and elaborate process described in Figure 3 (see page 7), fear that district consolidation could lead to school closures or loss of jobs, and the conflict of interest inherent in tasking school board members with approving consolidation efforts. (On this last point, interviewees note the difficulty of expecting local school board members to approve a merger that ultimately will result in one governing board rather than several, thereby potentially voting themselves out of a job.)

Local Communities Often Prefer Small Districts. Interviewees cite a number of advantages unique to smaller districts, which for many local communities outweigh the fiscal efficiencies and enhanced curricular offerings that might be available within larger districts. In rural areas, districts typically play a vital role in the community, with the school site serving as the center of civic activity. While district consolidation does not always necessarily equate to school consolidation and school closures, the research shows that this can frequently ensue. This tends to lead communities, which under current law must initiate and approve any consolidation effort, to be skeptical of potential long–term consequences for their local schools. Interviewees also claim that staff and leadership typically are more accessible and responsive to community and parent input in smaller districts, leading to widespread parent involvement in both day–to–day operations and long–term planning. Stakeholders argue this increases family engagement and engenders a deeper sense of belonging in small districts compared to what parents and students typically experience in larger districts.

Very Small Schools Also Are Enabled by Extra Funding, Lack Accountability

While the primary focus of this report is small school districts, there are overlapping fiscal and student performance issues related to small schools, particularly because so many small districts consist of one or two small schools. This overlap is especially evident in the NSS supplement—which is provided to small districts based on their very small schools—because it serves as one of the primary fiscal allowances that enable small districts to opt against consolidation. We find that the primary issues of concern regarding very small districts, including substantially higher funding rates and insufficient accountability for student outcomes, also apply to very small schools. Moreover, very small schools are notably limited in the educational programs they can afford to offer.

State Provides Additional Funding for Small Schools it Deems "Necessary." State law specifies the conditions that establish school eligibility for the NSS supplement. The eligibility criteria include size (elementary schools must have fewer than 101 ADA and high schools must have fewer than 301 ADA; both must be in districts with fewer than 2,501 ADA), distance (for example, if as many as five elementary students would have to travel more than ten miles one way to attend the nearest other school within that district), or other condition (for example, if nearby roads are typically impassable for more than two weeks a year). The base statutory NSS grant amounts (in lieu of revenue limits) provide $138,000 for each group of up to 24 elementary students and $500,000 for high schools with up to 19 students and three teachers. (In recent years, these amounts have been deficited commensurately with revenue limit reductions.) Figure 10 provides some information about districts receiving the NSS grant based on their exceptionally small schools. As shown in the figure, how much additional funding the supplement provides can vary significantly based on school size. (If it yields them more funding, districts with larger NSS–eligible schools may opt to receive per–pupil revenue limits instead of the NSS grant.) Of the 203 schools generating the NSS supplement, 74 serve fewer than 20 ADA, with 58 of these schools serving fewer than 15 ADA.

Figure 10

Supplement Provides Additional Funding to"Necessary" Small Schools

2009–10

|

Number of entities funded:

|

|

|

Districts

|

144

|

|

Schools:

|

203

|

|

Elementary

|

(127)

|

|

High

|

(72)

|

|

Middle

|

(4)

|

|

School Size:

|

|

|

Average

|

56

|

|

Maximum

|

252

|

|

Minimum

|

2

|

|

Total ADA funded

|

11,848

|

|

Per–Pupil Supplement:a

|

|

Average

|

$7,300

|

|

Maximum

|

$194,000

|

|

Minimum

|

$34

|

Some NSS Are of Questionable Necessity. Presumably, the goal of the NSS supplement is to enable exceptionally small schools to operate in remote areas of the state so that children do not have to spend excessive time in transit. These funds, however, also are subsidizing very small schools that qualify not because they are geographically isolated, but simply because the local community has chosen to maintain a small single–school district. Because the current statutory definition of whether a school is "necessarily small" does not require looking beyond district boundaries, single–school districts can qualify for the additional funding even if there is another public school just down the street—provided that school is in another district. This practice is particularly evident in counties that have numerous adjacent, single–school districts, including Siskiyou (20 NSS), Humboldt (19 NSS), and Mendocino (13 NSS). The geographic proximity of many of these schools calls into question whether all of them truly are "necessary" and deserving of additional funding allowances.

Very Small Schools Also Hard to Hold Accountable for Student Outcomes. The previously discussed problems with applying federal and state accountability systems to very small school districts also pertain to very small schools. Because the overall student population and/or particular subgroups may be too small to produce statistically significant results, it is difficult to get an accurate picture of student performance at very small schools. This problem is less severe for small schools located in larger districts because at least outcome data become significant and can be reliably tracked at the district level once aggregated with the district's other schools. It is more difficult to ensure accountability for the outcomes of students attending very small schools located in very small districts. Moreover, for the 230 single–school districts in the state, there is no difference between school–level and district–level accountability.

Very Small Schools Offer Limited Educational Programs. With few enough students that a single instructor might teach multiple grades and/or courses simultaneously, small schools often are unable to offer the variety of courses—particularly for high school students—that are standard in larger schools. As such, many small schools enroll students in distance learning courses via the internet, which can allow students access to specialized and advanced coursework schools cannot afford to offer without generating additional staff or transportation costs. However, options for digital coursework approved by the University of California for high school credit currently are somewhat limited. Additionally, an estimated 37 districts and 174 schools still lack the "last mile" high–speed internet connectivity necessary for students to take advantage of virtual learning opportunities. Distance learning also cannot make up for all of the offerings smaller schools often lack, including courses in visual and performing arts.

Recommendations

Our review does not convincingly substantiate most of the claims in support of district consolidation. Although the data suggest that midsize districts can allocate a greater proportion of their funding for instruction and tend to have slightly better student achievement, the differences are not large. Moreover, neither the academic research nor our own review offers persuasive evidence that consolidating small districts would necessarily result in substantial savings or notably better outcomes for students. (Indeed, poorer student outcomes at exceptionally large districts raise cautions about the potential downside of too much district consolidation.) Thus, while it might be easier for the state to have fewer agencies to oversee, the data do not convincingly support a dramatic change to current state policy such that small districts—those serving between 100 and 1,000 ADA—be forced to consolidate. Likewise, dedicating scarce funding resources to provide new fiscal incentives to promote greater district consolidation does not appear justified.

While our findings do not suggest the state should actively pursue greater district consolidations, nor do they support the current system that implicitly discourages districts from opting to consolidate. Specifically, we do not find evidence to justify the state's current practice of providing substantial fiscal advantages to districts that have opted to remain small, often as single–school districts—particularly since we find little proof that being small leads to better student outcomes. Additionally, we believe the data do justify changing state policy regarding very small districts. As such, we recommend the state remove some current disincentives for districts to consolidate, including unwarranted fiscal incentives to remain small, and make moderate changes to current minimum size thresholds. We also recommend the state apply some of these principles to very small schools.

Figure 11 lists our specific recommendations. Adopting these recommendations could result in some modest savings for the state. Because the amount of additional funding supporting the affected districts is relatively small, however, we believe the state–level savings might only be in the tens of millions of dollars. Yet these changes would remove problematic fiscal incentives and contribute to a more rational and equitable school funding system. Furthermore, we believe our recommendations would encourage small districts and schools to opt for greater efficiencies and accountability, while preserving the state's commitment to locally based decision–making. In this section, we discuss each of these recommendations in more detail.

Figure 11

Summary of Recommendations

|

|

- Increase minimum threshold for district size to at least 100 students.

|

- Eliminate fiscal incentives for districts to remain small.

|

- Eliminate some additional fiscal disincentives for districts to consolidate. Specifically:

|

- Clarify that most consolidations can waive California Environmental Quality Act review requirements.

|

- Eliminate statutory two–year salary and position protections for classified staff.

|

- Strengthen eligibility requirements to ensure state provides extra funding only to small schools that truly are necessary.

|

- Consider instituting minimum threshold for school size.

|

Increase Minimum Threshold for District Size to at Least 100 Students. Because they spend notably larger proportions of their budgets on overhead costs and are difficult to hold accountable for student performance, we recommend the state change its policies regarding very small districts. Specifically, we recommend the state increase the minimum size for districts from ADA of six for elementary and 11 for high school and unified to at least 100 ADA for all types of districts. We believe this still is an extremely low threshold, and the state could certainly consider a higher minimum requirement. However, we estimate that just moving to a minimum of 100 ADA would eliminate roughly 100 (or one in ten) districts in the state. (The state could use the current policy for districts that do not meet existing minimum size requirements, which allows them to "lapse" and immediately merge into a neighboring district without undertaking the formal consolidation process.) The state could maintain an option for districts to petition for a waiver if they are just under the cut–off point or if they exceed the minimum but still wish to merge into a neighboring district without the formal consolidation process.

Eliminate Fiscal Incentives for Districts to Remain Small. Because we find no rationale for why a community that has chosen not to consolidate their small districts deserves fiscal advantages, we recommend the state stop providing extra funding to districts based solely on their small size. Specifically, we recommend eliminating the practice of providing minimum grants for certain state categorical programs. Current programs with minimum grants include the Economic Impact Aid (EIA) program, Gifted and Talented Education, the Supplemental Counseling program, the School Safety Block Grant, and the Arts and Music Block Grant. (With the exception of EIA, all of these programs are part of the state's current categorical flexibility initiative.) Some of the funding advantages small districts receive, such as excess tax revenues and some other local revenues, are somewhat outside of the state's jurisdiction. However, the state could recognize the excess property tax revenue that basic aid districts receive and provide those districts commensurately less state aid for categorical programs in an effort to "level the playing field" with nonbasic aid districts.

Eliminate Some Additional Fiscal Disincentives for Districts to Consolidate. Besides the unattractive possibility that they would lose special funding advantages, districts also are reluctant to undertake consolidation because of potential associated costs and the possibility that it would not yield much savings. We recommend the state make two changes to address these issues:

- Clarify That Most Consolidations Can Waive CEQA Review Requirements. Currently, district consolidations are viewed as CEQA "projects," often necessitating a costly and lengthy review process that can serve as a deterrent to consolidating. Because district consolidations do not typically have significant environmental impacts, we recommend the Legislature remove the requirement that a CEQA study be undertaken (though in particular instances, a review may still be warranted, for example if the consolidation would necessitate building a new school).

- Eliminate Statutory Two–Year Salary and Position Protections for Classified Staff. Currently, districts are prohibited from laying off or reducing the salaries of classified employees (such as clerical, custodial, or other support personnel) until two years post–consolidation, even if an employee's position and its associated responsibilities are no longer necessary. This can prohibit newly consolidated districts from realizing all the potential savings that greater efficiencies and economies of scale might yield. We recommend the Legislature repeal this statutory provision.

Strengthen Eligibility Requirements to Ensure State Provides Extra Funding Only to Small Schools That Truly Are Necessary. We recommend the Legislature revise the statute that defines eligibility for the NSS supplement to incorporate students' ability to access other nearby schools, even if they are in other districts. We do not believe the state should pay more for small, costly schools simply because a community has chosen to maintain a single–school district when there are other public schools and districts within close proximity. Moreover, we recommend the state simplify and increase the statutory distance thresholds for how far students would need to travel to get to another public school before their local school is declared "necessary" to generate the supplement.

Consider Instituting Minimum Threshold for School Size. We recommend the Legislature consider establishing a minimum school size—perhaps 20 students—to encourage greater efficiencies and opportunities for students, with an option for waivers based on extreme circumstances. While we do not believe the state should maintain exceptionally small school districts, there is a persuasive rationale for why some remote schools are necessarily small—and therefore costly. However, we remain uncertain as to whether some schools might also be too small. The state currently does not have a minimum threshold for school size, and funds 75 schools that serve fewer than 20 students, with 40 of these schools serving fewer than ten students. Even if they are sufficiently geographically isolated to qualify for the NSS supplement under our revised eligibility criteria, we question whether exceptionally small schools make sense—for the state or for students. Because of the statistical limitations related to their small size, it is difficult to draw conclusions as to the performance outcomes of students who attend these schools. It is clear, however, that students at exceptionally small schools with few teachers and few peers are getting a different educational experience compared to most students in the state. Comparing the student benefits of avoiding extensive transit time and receiving a more individualized program against the drawbacks of more limited opportunities and notably higher state costs is a difficult policy decision that we believe merits further review.

Conclusion

The issue of school district consolidation is fraught with difficult policy questions, including debates over ideal district size, the role of the state in deciding local district configurations, the relationship between cost efficiencies and educational programs, and the best structure for delivering education in rural and geographically isolated communities. In most cases, these questions lead to inconclusive answers that can vary on a case–by–case basis. This report does not attempt to define a one–size–fits all response to school district configuration, but rather defaults to California's long–standing policy of letting local constituencies decide how to best structure their local districts. While our recommendations to restructure certain fiscal allowances and make a moderate increase to the state's minimum district size threshold would affect some small districts, we do not recommend a fundamental shift in the state's locally based decision–making structure. Instead, our recommendations are intended to assist the Legislature in creating school funding and accountability systems that are fair and effective for all of the state's districts. These improvements can, in turn, encourage local communities to opt for the most efficient and effective structure for delivering education to their students.

APPENDIX

Regionalization of County Offices of Education

In addition to district consolidations, we were directed to explore options for consolidating county offices of education (COEs) within regions in order to achieve greater efficiencies. Currently, COEs play an intermediary role between the state and local districts. Due to the expanse and diversity of the state, we would not recommend eliminating COEs. (However, we are uncertain about the added value of the seven COEs located in counties that maintain only one school district.) While we think more regionalization for certain initiatives likely has some advantages, we also believe changes in COE responsibilities should be part of a broader discussion on educational governance and service delivery in California.

Not All COEs Created Alike. Each of the state's 58 counties maintains a county superintendent of schools and associated COE. In general, COEs offer certain support services (such as professional development for teachers and administrators), operate educational programs for specific student populations (such as alternative schools and special education services), and provide local school districts with fiscal and academic oversight and technical assistance. However, the specific roles, activities, and capabilities of these offices can vary greatly across the state depending upon local characteristics. For example, the COEs operating in counties with numerous school districts and/or particularly small districts meet different needs compared to those in counties with few and/or large districts. Moreover, the nature of the services individual COEs can provide is affected by their funding levels, which differ based on historical factors and the number of children in the county. Interview responses suggest that COEs can also differ in the quality of the services and assistance they provide to local districts. In addition, some COEs have developed unique and entrepreneurial services, including insurance pools, legal services, and extensive teacher resource centers. Finally, in the seven counties that contain only one school district, the role of the COE is not as clearly defined, with it typically serving more as an extension of the district office rather than a regional coordinating entity.

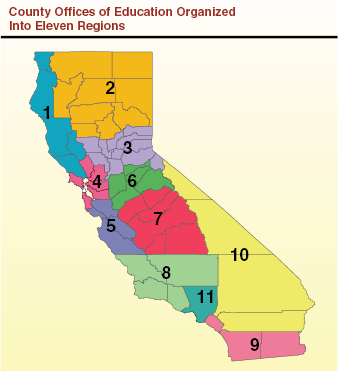

Regional Service Model Has Both Promise and Limitations. Because they operate countywide, COEs already represent a regional approach to providing academic and support services. However, the state has explored even higher level service delivery by implementing some initiatives through 11 consortia of COEs. The figure shows a map of these 11 regions. Examples of existing regional initiatives include the Statewide System of School Support (support for low–performing schools and districts), the California Technology Assistance Project, and the California Preschool Instructional Network. Interviews suggest this regional approach yields both fiscal and programmatic efficiencies. Greater economies of scale allow regions to pool resources and take full advantage of a certain county's comparative advantages, allowing all districts in the region to have access to expert services regardless of their local COE's capacity. To expand this approach, the state could consider making strategic investments to develop regional centers of expertise for additional programmatic areas. However, given the expanse and diversity of the state, the regional model is not appropriate for all initiatives—particularly those requiring greater responsiveness to unique local needs.

Regionalization of COE Services Should Be Part of Larger Conversation on Education Governance. While there is value in exploring expansion of the regional model, we believe this is merely one component of a broader discussion on the state's system of educational delivery. The role of the COEs is inextricably linked to the role of the California Department of Education (CDE) and the appropriate division of responsibilities between the state and local educational agencies. In an effort to bring services closer to districts, the state has devolved a number of technical assistance, monitoring, and intervention responsibilities from CDE to COEs. We believe the state should undertake a serious discussion of which types of educational activities are most appropriately conducted at each level of government—state, region, county, and district—then align responsibilities and funding correspondingly. An explicit focus on regionalizing COEs absent this larger discussion would be shortsighted and likely counter–productive.