Large Budget Problem Little Changed Since January. In the May Revision, the administration estimates that California must address a $17.9 billion gap between current–law resources and expenditures in the 2010–11 General Fund budget. In our view, the administration’s estimate is reasonable. While our tax revenue estimates are slightly higher than the Governor’s: $400 million in 2009–10 and $1 billion in 2010–11—overall, our view of the budget problem is similar.

Governor’s Proposal Relies Heavily on Spending Reductions. The Governor’s May budget package proposes $19.1 billion of solutions—enough to close the $17.9 billion shortfall and leave the General Fund with a $1.2 billion reserve. Program spending reductions make up two–thirds of the solutions proposed by the Governor. Compared to his January proposal, the May Revision assumes a more reasonable level of increased federal aid ($3.4 billion), although receipt of even that amount remains uncertain. Borrowing and fund shifts total about 10 percent of the Governor’s solutions. New revenues make up under 5 percent of the Governor’s package.

Significant New Spending Reduction Proposals. The May Revision includes major spending reduction proposals that were not included in the Governor’s base budget package in January. In particular, the Governor proposes eliminating the California Work Opportunity and Responsibility to Kids (CalWORKs) program, which provides cash grants and welfare–to–work services to over 1 million Californians in low–income families. He also would eliminate state funding for need–based, subsidized child care thereby eliminating slots for more than 200,000 children. The cuts mainly would be ongoing in nature. Still, even if the Legislature approved all these painful cuts and realized the savings assumed by their passage, a stubborn multibillion dollar operating deficit would persist in the years to come.

Throughout the spring, our office has offered alternative spending reduction proposals to the Legislature. In many areas, including health and social services programs, our alternatives reduce program spending by a lesser amount than the Governor in order to preserve core services for those most in need. In other cases, such as the universities, trial courts, and public safety local assistance grants, we believe there are opportunities for savings beyond those identified by the administration. We advise the Legislature to reject the Governor’s most drastic spending cuts, especially the elimination of CalWORKs and child care funding. Our alternative spending reductions—in conjunction with other budget actions—could help sustain critical components of these important programs.

More Revenues Could Ameliorate the Most Severe Cut Proposals. The Governor presents Californians with a clear vision of the types of severe program reductions that are necessary if the budget were balanced without some additional revenue increases this year. Alternatively, some of the most severe cuts proposed by the Governor could be avoided by adopting selected revenue increases—from fee increases and other nontax revenues, changes to tax expenditure programs, delays in previously scheduled tax reductions or expirations, and targeted tax increases. We urge the Legislature to put these types of solutions in the mix.

Given the state budget situation, there is a real question whether California can afford to fund the current–law Proposition 98 minimum funding level. Rather than adopt strained legal interpretations of the funding guarantee, as presented by the Governor, the Legislature should forthrightly suspend Proposition 98 if the minimum guarantee is above the level of funding that the state can afford.

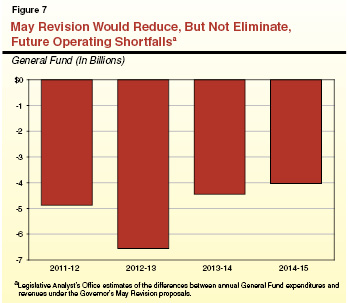

Even if the Legislature adopted all of the May Revision’s proposals and achieved the full estimated savings, the state would be left with a multibillion dollar (between $4 billion and $7 billion) annual operating shortfall. We believe that the Legislature should therefore adopt changes now that will help address the remaining problem. Major changes that would move the state in the right direction include a stronger state “rainy day fund,” realignment of certain state responsibilities and funding to local governments, changes to kindergarten and after school programs, and major pension and retiree health reform.

The last decade has provided some of the most challenging budget situations—including last year’s plan addressing roughly $60 billion in solutions. Yet this year’s budget situation may prove to be the most difficult. All of the major options available to the Legislature to close the budget gap will be difficult. The two basic avenues to balancing this budget—sharply lower spending in some programs and higher revenues—each result in negative consequences for the economy, jobs, and the Californians most directly affected. While much of the remainder of this budget process will focus on how to minimize the damage to taxpayers and program service levels, we urge elected leaders to use this crisis to better prepare the state to cope with future economic downturns and challenges.

Relatively Minor Changes Between January and May. When he submitted the 2010–11 Governor’s Budget to the Legislature on January 8 and called the Legislature into a fiscal emergency special session, the Governor identified an $18.9 billion current–law budget shortfall in the General Fund in 2010–11. (At that time, he proposed $19.9 billion of budget solutions to close the shortfall and leave the state with a $1 billion reserve.) Enacted special session legislation—which put in place the so–called “gas tax swap” (the elimination of the gasoline sales tax offset by an increase in the per gallon excise tax on gasoline)—reduced the 2010–11 budget problem by $1.4 billion according to administration estimates. (As described in the nearby box, enacted special session legislation also included laws to address the state’s serious cash flow problems.) In addition, the federal government agreed to apply an enhanced federal Medicaid match to the state’s Medicare Part D “clawback payments,” which resulted in $680 million of General Fund relief. Offsetting these positive developments were estimated cost increases of about $500 million and an estimated revenue decline of about $600 million. Accordingly, the administration now estimates that on net the size of the 2010–11 budget problem has declined $1 billion, to $17.9 billion.

|

Background. As we described in our January 2009 report,

California’s Cash Flow Crisis, the state suffers from a basic cash flow problem, even in good years. Most revenues are received during the second half of the fiscal year (January to June), while most expenses are paid in the first half of the fiscal year (July to December). When the state is unable to borrow—as occurred in February 2009 and during the summer 2009 budget impasse—the Controller sometimes must refrain from making some payments or issue “IOUs” so that the state’s “priority payments,” such as debt service and payroll, continue as scheduled. Issuing IOUs rattles investors and disrupts finances of state payment recipients. More flexibility to delay some payments helps prevent IOU issuance.

More Flexibility for State Cash Flow Management in 2010–11. As part of the special session, the Legislature passed two bills—ABX8 5 (Committee on Budget) and ABX8 14 (Committee on Budget)—that give the executive branch more flexibility to manage cash in 2010–11. These measures allow the state to delay roughly $5 billion of scheduled payments to schools, universities, and local governments at almost any given time. Assuming the state meets previously estimated revenue and expense targets in May and June 2010, it will enter 2010–11 with a $7 billion cash cushion (from available balances of special funds)—about the same as one year ago. The flexibility provided by the cash legislation, however, should help the state survive the first few weeks of the summer “cash drought” when expenses often far exceed receipts. Nevertheless, should a prolonged budget impasse or financial market disruptions delay the state’s routine annual cash borrowing past August or September, the Controller may again have to issue IOUs or implement unscheduled payment delays. |

Administration Withdraws Some January Proposals. In the May Revision, the Governor drops a few proposals he made in January. Specifically, following a major oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico, the Governor dropped his support for drilling for oil off the Santa Barbara coast (a $197 million solution in January). The administration withdrew certain criminal justice proposals, including a $317 million January solution that would have shifted specified non–serious felons to a maximum sentence of 366 days in county jails instead of state prisons. The Governor also backed off his proposal to suspend new competitive CalGrant financial aid (a $46 million January solution).

Figure 1 lists the Governor’s current budget proposals, including the changes made in his May Revision. Many proposals remain from the Governor’s January budget package—such as the $811 million January proposal to score savings in the Receiver’s inmate medical care operations remains. (Estimated savings from some of these proposals have been lowered due to assumed later enactment.) Major new or modified May Revision solutions are described below.

Figure 1

General Fund Budget Solutions Proposed by the Governor

2009–10 and 2010–11 Combined (In Billions)

|

|

Reduced Costs or

Increased Revenues

|

|

Expenditure–Related Solutions

|

|

|

Reduce Proposition 98 spending (including elimination of child care)

|

$4.3

|

|

Reduce state employee pay and staffing, and shift pension costs to employees

|

2.1

|

|

Eliminate CalWORKs program

|

1.2

|

|

Implement various changes to Medi–Cal

|

0.9

|

|

Reduce inmate medical care costs

|

0.8

|

|

Reduce IHSS spending (excluding enhanced federal match)

|

0.8

|

|

Reduce county mental health realignment funds by 60 percent

|

0.6

|

|

Redirect county savings from social services reductions

|

0.4

|

|

Commit certain offenders to county jails, not state prisons

|

0.2

|

|

Suspend or defer certain mandate reimbursementsa

|

0.2

|

|

Reduce spending in various health programs

|

0.2

|

|

Reduce spending in various social services programs

|

0.2

|

|

Reduce SSI/SSP grants for individuals to the federal minimum

|

0.1

|

|

Reduce other spending

|

0.3

|

|

Subtotal

|

($12.2)

|

|

Assumed Federal Funding and Flexibility Solutions

|

|

|

Assume more federal money or flexibility in Medi–Cal and other programs

|

$1.6

|

|

Assume extension of enhanced FMAP funding for Medi–Cal Program

|

1.4

|

|

Assume enhanced funding for other programs

|

0.4

|

|

Subtotal

|

($3.4)

|

|

Loans, Loan Extensions, Transfers, and Funding Shifts

|

|

|

Borrow from special funds

|

$1.1

|

|

Extend due dates for existing special fund loans to General Fund

|

0.5

|

|

Use remaining authorized hospital fees for Medi–Cal children’s health coverage

|

0.2

|

|

Use temporary federal retiree reinsurance funds to reduce state retiree health costs

|

0.2

|

|

Transfer special fund monies to the General Fund

|

0.1

|

|

Use excess Student Loan Operating Fund monies for Cal Grant costs

|

0.1

|

|

Adopt other funding shifts

|

0.4

|

|

Subtotal

|

($2.6)

|

|

Revenue Solutions

|

|

|

Score additional revenues from previously authorized state asset sales

|

$0.5

|

|

Authorize automated speed enforcement to offset trial court costs

|

0.2

|

|

Extend hospital fees

|

0.2

|

|

Levy 4.8 percent charge on all property insurance for emergency response activities

|

0.1

|

|

Subtotal

|

($0.9)

|

|

Total, All Proposed Solutions

|

$19.1

|

As shown in Figure 1, the Governor’s budget package includes $12.2 billion of expenditure–related solutions. Generally, these are budget solutions that would reduce program spending and result in a lower level of governmental services for affected residents. New or substantially modified expenditure–related solutions in the May Revision include the following.

Reduce Proposition 98 Spending ($4.3 Billion). A major change to the Governor’s Proposition 98 package in the May Revision is the proposed elimination of need–based, subsidized child care (not including preschool funding). The Governor’s proposed reductions in Proposition 98 spending are described later in this report.

Reduce State Employee Pay and Staffing, and Shift Pension Costs to Employees ($2.1 Billion). The Governor maintains his “5/5/5” employee compensation proposal from January—reducing state employee salaries by 5 percent, increasing state employee pension contributions by 5 percent for a like amount of state savings, and increasing departmental “salary savings” by 5 percent to reduce state payrolls. In total, the Governor’s January employee compensation package is scored as a $1.6 billion General Fund budget solution by the administration, and its provisions also generally apply to the state’s special funds. (Special funds generally are fee–driven accounts, such as the Motor Vehicle Account [MVA].) In the May Revision, on top of the 5/5/5 proposal, the Governor proposes a “mandatory personal leave program” (PLP), estimated to achieve $795 million ($446 million General Fund) of state savings. Under PLP, state employees in the executive branch would have their take–home pay reduced by the equivalent of eight hours of pay each month in 2010–11, and they would be credited with an equal number of PLP hours. Employees would have discretion when to use their PLP leave. In addition, furlough Fridays would end in June 2010.

Eliminate CalWORKs Program ($1.2 Billion). In the May Revision, the administration proposes the elimination of CalWORKs. Substantially funded by the federal government, CalWORKs provides cash grants and welfare–to–work services to low–income families. Currently, enhanced federal funding included in last year’s federal economic stimulus legislation (and assumed to be extended through 2010–11 in the Governor’s budget package) applies to CalWORKs. Accordingly, elimination of CalWORKs would result in a substantial loss of federal funding for the state.

Implement Various Changes to Medi–Cal (About $900 Million). The May Revision proposes a variety of additional changes to Medi–Cal, including enrolling seniors and people with disabilities in managed care ($179 million); imposing new copayment requirements for various services ($ 152 million), hospital stays ($73 million), and emergency room visits ($54 million); limiting physician or clinic visits to ten per year ($90 million); and freezing hospital rates ($85 million). The Governor’s budget assumes federal approval of a state plan amendment or waiver to achieve the assumed savings. Enhanced federal funding approved as part of the economic stimulus legislation is assumed to be extended through 2010–11. In addition to the types of proposals described above for the Medi–Cal Program, the Governor also proposes elimination of Drug Medi–Cal (except for perinatal and youth services programs). Drug Medi–Cal, funded in part by the federal government as part of California’s Medicaid program, pays for substance abuse treatment, including methadone.

Reduce IHSS Spending ($750 Million). With various prior In–Home Supportive Services (IHSS) reductions blocked by the courts, the administration now proposes to consult with stakeholders to achieve IHSS cost savings. While the full–year General Fund savings proposed is $750 million beginning in 2011–12, the net General Fund benefit in 2010–11 would be $637 million because of enhanced federal matching funds that resulted from the federal economic stimulus legislation. This proposal would reduce General Fund support of this program by roughly half.

Reduce County Mental Health Realignment Funds ($602 Million). Counties use mental health realignment funds—totaling about $1 billion under current law in 2010–11—to support a range of mental health services for indigent persons as well as Medi–Cal enrollees. Under the administration proposal, counties would no longer have to provide more than the minimum range of mental health services required by the federal government for participation in Medicaid, resulting in estimated savings of $602 million. (The remaining $435 million in mental health realignment dollars would be used to fund only these required services—such as early and periodic screening, diagnosis, and treatment; in–patient hospital psychiatric services; and medication.) The county savings, however, would be offset by increased county funding shares for certain social services programs. The state would realize savings from the correspondingly lower funding shares for these same social services programs. The Governor no longer proposes changes to Proposition 63—which provides about $1 billion per year for mental health services from a personal income tax (PIT) surcharge on taxable income in excess of $1 million.

Place Certain Offenders in County Jails, Not State Prisons ($244 Million). Under the May Revision proposal beginning July 1, 2010, non–serious, non–violent, non–sex offenders who are convicted of specified felonies and sentenced to three years or less would serve their sentence in a county jail instead of state prison. The administration estimates this would reduce the prison population by 10,600 inmates in 2010–11 and generate $244 million of savings. Beginning in 2011–12, the state would establish a public safety block grant program for counties to be funded using about one–half of the state’s prior fiscal–year savings from this shift. Also as part of the May Revision, the Governor proposes legislation to continuously appropriate $503 million annually from the General Fund for various local public safety programs beginning in 2011–12. The programs now are funded with revenues from the temporary vehicle license fee (VLF) increase that is set to expire on June 30, 2011. (Taken altogether, these proposals would help balance the 2010–11 budget, but would result in a net General Fund cost increase of nearly $300 million beginning in 2011–12.)

More Reasonable—Though Still Uncertain—Federal Funding Assumption ($3.4 Billion). In his January budget proposal, the Governor proposed a budget based on the assumption that the federal government would provide additional funding of about $6.9 billion in 2010–11, principally for health and social services programs. In the event that the federal government was not forthcoming with this aid, the administration proposed a “trigger” list of alternative revenue and expenditure solutions. As described above, the federal government already has provided $680 million of additional funding to the state related to the Medicare Part D clawback, and these funds are already factored into health program budgets in the May Revision. The Governor now assumes a much smaller amount of additional federal aid: $3.4 billion. About half of this would be provided through an assumed congressional extension of enhanced Federal Medical Assistance Percentage program and other funding originally approved in last year’s economic stimulus legislation. An additional $1.6 billion in the May Revision relates to unspecified future federal funding or flexibility in Medi–Cal and other programs. The May Revision—with this much smaller assumption of new federal funding—includes no trigger list of alternative proposals.

The Governor’s budget proposals, as amended by the May Revision proposals, include $2.6 billion of loans, loan extensions, transfers, and funding shifts. Major new proposals in this category are:

- Loans, Transfers, and Loan Extensions Related to Special Funds ($1.6 Billion). As described in the next part of this report on revenues, the budget includes $1.6 billion of one–time budget relief by using special fund dollars for General Fund purposes.

- Temporary Use of Federal Retiree Reinsurance Funds to Reduce Retiree Health Costs ($200 Million). The recent federal health care reform legislation included a temporary “early retiree” reinsurance program designed to assist employers in preserving existing health coverage for pre–Medicare retirees age 55 to 64. This program will be in place until the establishment of health care “exchanges” intended to provide more affordable health care options. The budget reflects an expectation that costs for the California Public Employees’ Retirement System’s state retiree health plans will be reduced $200 million in 2010–11 under this temporary program. (This is a preliminary estimate that will be refined in the coming weeks. Final savings, we expect, will be less than $200 million.)

As shown in Figure 1, the May Revision includes about $900 million of new revenues to help balance the 2010–11 budget, principally from the Governor’s January budget proposals. As described above, the Governor has abandoned one of his January revenue proposals that related to oil drilling at Tranquillon Ridge off the coast of Santa Barbara County.

2009–10: Huge Year–End Shortfall. As shown in Figure 2, the administration estimates that the General Fund would end 2009–10 with a negative reserve balance of $6.8 billion. Despite spending more than it took in, the state has continued operations through a variety of cash management measures in 2009–10, including borrowing from investors, loans from state special funds, payment delays, and (early in the fiscal year) IOUs.

Figure 2

Governor’s May Revision General Fund Condition

(Dollars in Millions)

|

|

Proposed

2009–10

|

|

Proposed for 2010–11

|

|

|

Amount

|

Percent Change

|

|

Prior–year fund balances

|

–$5,361

|

|

–$5,305

|

|

|

Revenues and transfers

|

86,521

|

|

91,451

|

5.7%

|

|

Total resources available

|

$81,160

|

|

$86,146

|

|

|

Expenditures

|

$86,465

|

|

$83,404

|

–3.5%

|

|

Ending fund balance

|

–$5,305

|

|

$2,742

|

|

|

Encumbrances

|

$1,537

|

|

$1,537

|

|

|

Reservea

|

–$6,842

|

|

$1,205

|

|

2010–11: $8 Billion Estimated Operating Surplus. The administration estimates that, under the Governor’s May Revision policies, General Fund revenue and transfers in 2010–11 will be $91.5 billion, while expenditures would be $83.4 billion. This results in an $8 billion operating surplus. That surplus would both address the $6.8 billion problem in 2009–10 and allow the state to end the 2010–11 fiscal year with a $1.2 billion reserve. This is a $200 million larger reserve than the Governor proposed in his January budget package.

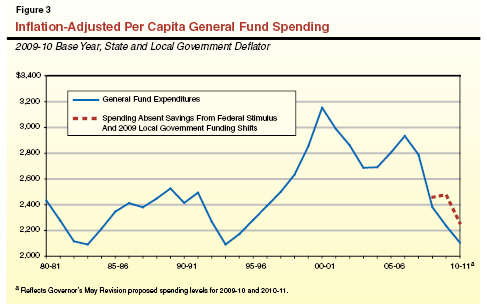

Per Capita Real General Fund Spending Would Drop to Mid–1990s Levels. As shown in Figure 3, the level of spending proposed by the administration would continue the recent drop in state spending, as adjusted for growth in population and inflation. In 2010–11, the inflation–adjusted per capita spending level would be similar to that of 1993–94—also at a low point due to a recession. Since 2008–09, large temporary boosts in federal stimulus funds and shifts of local government property taxes (lowering General Fund spending) have helped the state balance its budget. Even accounting for these factors, adjusted General Fund spending under the May Revision would be at its lowest level since 1995–96.

In addition to proposals to address the state’s large General Fund deficit, the May Revision includes proposals affecting state special funds, the use of bond proceeds, and other accounts. Major non–General Fund proposals in the May Revision include:

- Initial Appropriations From the Water Bond on the November 2010 Ballot. The May Revision proposes that the Legislature appropriate $1.1 billion of proceeds from the $11 billion water bond proposal before voters on the November 2010 ballot. The Governor proposes appropriating about $700 million of these proceeds for the Departments of Water Resources, Fish and Game, and Public Health for drought relief, groundwater, conveyance, desalination, Delta sustainability, and other projects. In addition, $419 million of bond proceeds are proposed to be appropriated for the Water Resources Control Board to fund water recycling and wastewater projects.

- Decrease of Funds for Caltrans Capital Outlay Support Program. The May Revision budgets a net decrease of $42 million for engineering workload in the Department of Transportation’s (Caltrans) capital outlay support program, including a reduction of 750 engineering and other positions and 102 overtime position–equivalents, as well as an increase of 69 contract staff. This will make more State Highway Account funds available for highway maintenance activities.

Forecast of Moderate Recovery. The economic forecast underlying the May Revision’s revenue estimates assumes that the state and national economies will continue to recover at a moderate pace from the deep recession of 2007 through 2009. State personal income growth is projected at 3.2 percent in 2010 and 4.5 percent in 2011—slightly lagging the forecast for the nation as a whole. The May Revision forecast reflects some positive economic developments since the release of the Governor’s budget, including the report that national gross domestic product grew 5.9 percent in the fourth quarter of 2009. As with its prior forecast, however, the administration expects that employment growth will be slow in bouncing back.

Modest Reduction in Tax Revenues Since January. Tax revenue receipts from December to March this year were well above those amounts assumed in the Governor’s January budget. These encouraging gains, however, were wiped out by April receipts, which fell more than $3 billion short of expectations. The sharp April decline—concentrated in PIT receipts—reflected a combination of (1) revenues coming in on a different timeline than originally expected and (2) somewhat worse receipts attributable to the 2009 tax year. Consequently, as shown in Figure 4, the May Revision estimates that current–year revenues from the state’s “big three” taxes will fall short of original expectations by more than $1.8 billion. For the budget year, the May Revision’s forecast for these taxes is just slightly ($226 million) above the January outlook. In both years, strong sales tax receipts are helping to offset expected PIT shortfalls. Taxable sales are projected to jump 7.8 percent in 2010–11, reflecting continued improved consumer spending after three straight years of decline.

Figure 4

May Revision Revenue Forecast Similar to January

(In Millions)

|

|

May Revision

|

|

Change From January Budget

|

|

|

2009–10

|

2010–11

|

|

2009–10

|

2010–11

|

|

Personal income tax

|

$44,021

|

$46,245

|

|

–$2,619

|

–$617

|

|

Sales and use tax

|

26,852

|

26,967

|

|

816

|

1,116

|

|

Corportation tax

|

9,386

|

9,779

|

|

–21

|

–273

|

|

Subtotals, “big three” revenues

|

($80,259)

|

($82,991)

|

|

(–$1,824)

|

($226)

|

|

Other revenues

|

5,815

|

7,347

|

|

243

|

261

|

|

Transfers/loans

|

447

|

1,116

|

|

19

|

1,642

|

|

Totals

|

$86,521

|

$91,454

|

|

–$1,562

|

$2,129

|

Budget Reflects New Loan Proposals. The primary reason that the administration’s new 2010–11 revenue forecast is $2.1 billion higher than its January outlook is the addition of $1.6 billion in proposed one–time revenues related to the use of state special fund dollars for General Fund purposes.

- New Loans. The Governor proposes $1.1 billion in new borrowing of special fund balances, including $650 million from fuel excise taxes and $250 million from the MVA.

- Delayed Repayment. The proposed loans would be added to the state’s existing outstanding balance of $1.8 billion in similar loans previously authorized by the Legislature. The May Revision proposes to delay the repayment of $494 million associated with these existing loans that otherwise would take place in 2010–11.

- New Transfers. The Governor also proposes transferring $82 million from special funds, primarily the MVA, to the General Fund. Transferred funds would not need to be repaid.

LAO Forecast Similar, But Slightly Higher. Our own updated economic and revenue forecasts are quite similar to those of the administration. They both reflect the consensus view that the state is pulling out of the recession’s doldrums—but slowly. Our economic outlook shows almost identical personal income growth rates in California over the next two years. As such, we believe the May Revision revenue forecast is reasonable and realistic. Under our forecast, we expect revenues to be slightly higher in the final two months of 2009–10 and leave the state about $400 million better off. In 2010–11, our expectation for the big three tax revenues is about $1 billion (1 percent) higher than the administration. The largest difference relates to the PIT and, specifically, capital gains. Our slightly more positive view of capital gains’ rebound in 2010 accounts for most of the revenue difference. Yet, our forecast still expects capital gains to be about one–half of their 2007 level.

June 2010 Will Be Key Month. Due to recent budget agreements to accelerate revenue collections, California taxpayers are now scheduled to make 40 percent of their estimated annual payments in the month of June. This policy change, combined with April’s weak receipts, means that June 2010 is now expected to be the state’s largest revenue collection month for 2009–10. How much the state will receive in June is difficult to assess given the recent acceleration change and uncertainty over the precise strength of the state’s economy. June’s actual receipts will help clarify the state’s revenue outlook for the upcoming year.

Estate Tax Assumption Looks Shaky. Based on the provisions of current federal law, the May Revision assumes $892 million in revenues from the federal estate tax in 2010–11, and our forecast also includes a similar amount. It appears increasingly unlikely, however, that the federal government will allow the restoration of the state estate tax exemption in 2011 (known as the state “pickup” tax) as provided for under current law. Both the President’s budget and pending congressional legislation would eliminate the state pickup tax. Unless Congress fails to act on this issue (thus leaving current law in place), we would expect that the state will not receive the estate tax revenues.

More Revenues Possible From Sale of State Buildings. The May Revision continues the January budget estimate of about $600 million in revenues from the sale of state office buildings authorized in the 2009–10 budget package. As we described in our April 2010 report

Evaluating the Sale–Leaseback Proposal: Should the State Sell Its Office Buildings?, we believe that the sale could net the state hundreds of millions of dollars more than this assumption. If the Legislature and the Governor finalize such a sale in the next few months, budget estimates could be adjusted considerably upward to reflect the final sale amount. Given the poor long–term fiscal policy of this proposal, however, we would encourage the Legislature to consider other alternatives for closing the budget gap.

Figure 5 shows the Governor’s May Revision Proposition 98 spending levels. Relative to the Governor’s January budget, the May Revision contains only a minor funding increase in the current year (due to various technical adjustments) but a substantial funding reduction in the budget year (due to the proposed elimination of child care programs). We describe these adjustments in more detail below.

Figure 5

Governor’s Proposition 98 Funding Proposal

(In Millions)

|

|

2009–10

|

|

2010–11

|

|

|

January Budget

|

May Revision

|

Change

|

|

January Budget

|

May Revision

|

Change

|

|

K–12 Education

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

General Fund

|

$30,844

|

$32,022

|

$1,178

|

|

$32,023

|

$30,927

|

–$1,096

|

|

Local property tax revenue

|

13,237

|

12,105

|

–1,133

|

|

11,950

|

11,529

|

–422

|

|

Subtotals

|

($44,082)

|

($44,127)

|

($45)

|

|

($43,974)

|

($42,456)

|

(–$1,518)

|

|

California Community Colleges

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

General Fund

|

$3,722

|

$3,722

|

—

|

|

$3,981

|

$3,991

|

$9

|

|

Local property tax revenue

|

1,953

|

1,962

|

$8

|

|

1,913

|

1,907

|

–6

|

|

Subtotals

|

($5,675)

|

($5,683)

|

($8)

|

|

($5,895)

|

($5,898)

|

($3)

|

|

Other Agencies

|

$94

|

$93

|

–$1

|

|

$85

|

$89

|

$3

|

|

Totals

|

$49,851

|

$49,903

|

$52

|

|

$49,954

|

$48,442

|

–$1,512

|

|

General Fund

|

$34,660

|

$35,837

|

$1,177

|

|

$36,090

|

$35,007

|

–$1,083

|

|

Local property tax revenue

|

15,191

|

14,066

|

–1,124

|

|

13,864

|

13,435

|

–428

|

Current–Year Proposition 98 Changes. Although the drop in 2009–10 General Fund revenues resulted in a drop in the minimum guarantee, the Governor’s proposed Proposition 98 spending level for 2009–10 remains virtually unchanged from January. As a result, the May Revision provides $503 million more than the Governor’s estimate of the Proposition 98 minimum guarantee. The Governor counts this overappropriation as a payment towards an $11.2 billion statutory obligation related to the 2009–10 budget package (with subsequent payments to resume in 2011–12). Despite the small change in Proposition 98 spending, the May Revision includes $1.1 billion in additional General Fund spending to offset a decline in local property tax revenue (due primarily to the Governor’s decision to use $877 million in one–time property tax revenues to support other parts of the state budget). Largely because of this increase in General Fund spending, the state would now meet the 2009–10 federal maintenance–of–effort (MOE) requirements for K–12 education.

Budget–Year Proposition 98 Changes. For 2010–11, the May Revision reduces Proposition 98 spending by $1.5 billion from the January level. Of the total reduction, $1.2 billion is achieved by eliminating all Proposition 98 support for state–subsidized child care programs (except state preschool programs). The Governor also proposes using $321 million in unspent prior–year funds, thereby achieving the same amount of ongoing Proposition 98 savings. The Governor maintains his January proposals to reduce K–12 revenue limits (by $1.5 billion) but no longer links these reductions to savings in contracting and administration. In 2010–11, the state would not meet its federal MOE requirement for K–12 education. Thus, it would continue to seek a waiver. (It appears to qualify for the waiver.)

To Achieve Budget–Year Savings, Governor Proposes “Rebenching” Proposition 98. To achieve additional budget–year savings without suspending the Proposition 98 minimum guarantee, the May Revision “rebenches” the guarantee to reflect the elimination of child care services. The rebenching essentially reduces the 2010–11 minimum guarantee by an amount equal to Proposition 98 child care spending in 2009–10. By rebenching the guarantee, the Governor essentially redefines expenditures counted towards Proposition 98 and the minimum percentage of General Fund revenues that the state must provide for Proposition 98 spending. This rebenching results in 2010–11 savings of $1.5 billion. The Governor does not rebench for the gas tax swap as required by the agreement enacted in March. Instead, he proposes to override a statutory “hold harmless” provision of that measure, thereby avoiding $686 million in additional state costs.

In our February analysis, we noted that the Governor’s overall Proposition 98 funding plan was tenuously held together. In particular, we raised concern that the Governor’s Proposition 98 approach was legally risky, as it assumed the state had no maintenance factor obligation (constitutionally required payments to restore education spending over time) entering 2009–10. Not only does the May Revision retain this questionable maintenance factor assumption, but it is further complicated by the proposed rebenching of the minimum guarantee due to the elimination of child care programs.

Legality Uncertain. The legality of rebenching for the elimination of state–subsidized child care is uncertain. This uncertainty is heightened due to the Governor’s assumption that some federally funded child care continues to be administered by existing providers. That is, under the Governor’s plan, no functional responsibility has been eliminated entirely or clearly shifted to a different set of entities. Moreover, unlike rebenching for local property tax shifts, the state has little experience with rebenching for the shift or elimination of a program once funded within Proposition 98.

The Governor’s May plan does not reflect a particularly useful architecture upon which to build the state’s K–14 education budget. Absent the Governor’s legal interpretations, his proposed spending level would require suspension of the Proposition 98 minimum guarantee. The May plan also is based on the Governor’s questionable policy decision to eliminate all state–subsidized child care immediately. (We discuss our recommended approach on child care in more detail later in this report.)

Current–Law Requirement Likely Unaffordable. Under current law, the state would need to provide substantially more money than the Governor proposes—$4.1 billion higher than the Governor’s May level and $2.9 billion higher than the Governor’s January level. As such, we believe the state cannot afford to support K–14 education at this level.

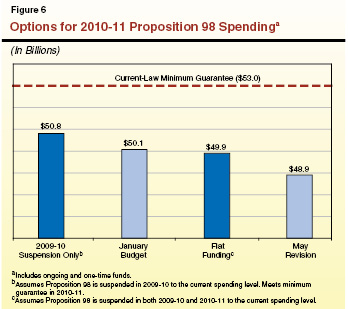

Take a Different Approach. Given these concerns, we recommend the Legislature take a different approach in building the K–14 budget. Figure 6 shows two budget–year Proposition 98 options in addition to the Governor’s January and May plans. Below, we discuss these budget alternatives in more detail. As discussed below, the key question for the Legislature in building its K–14 education budget will be how much it can afford given its other budget pressures.

Two Options Require Suspension in 2009–10. The two options identified in the figure as alternatives to the Governor’s proposal would require suspension of the minimum guarantee in 2009–10 to the current spending level (as allowed under the California Constitution). Despite the suspension, schools would be funded at the same level as proposed by the Governor and would not be subject to additional programmatic reductions in 2009–10 (beyond the reductions already imposed in the enacted budget). The primary reason for suspending Proposition 98 is to clarify that maintenance factor does exist upon entering 2009–10 (to the significant benefit of education over the long run). As a result, suspension potentially could resolve the maintenance factor issue in a straightforward manner. While signaling that maintenance factor exists, suspension also acknowledges that the state cannot afford to make an immediate payment. (In 2009–10, under current law, the state would need to make an additional maintenance factor payment of almost $1.3 billion absent suspension.) Suspending in 2009–10 also provides benefit to the state by lowering the minimum guarantee for 2010–11.

After suspending in 2009–10, the Legislature then would have two options for 2010–11:

- 2009–10 Suspension Only. Under this option, the state would fund the minimum guarantee in 2010–11 ($50.8 billion). While this option would provide notably less than required under current law, it is higher than the May Revision level by $1.9 billion (or $700 million, excluding the effect of the child care elimination).

- Flat Funding. Another option would be to suspend the guarantee to the current spending level in both years ($49.9 billion). Though Proposition 98 funding would remain flat year over year, the state still would need to cut $1.9 billion in K–14 Proposition 98 program spending. This is because the state used considerable one–time state monies in 2009–10 to support its ongoing programs. (Similarly, many school districts will experience additional program reductions because they used their one–time federal stimulus monies in 2009–10 to support ongoing programs.)

Make Targeted Reductions First. Whether the state adopts the one–year suspension option, the flat–funding option, or some other funding level, some reductions to K–14 education will be needed. We recommend that the Legislature first make targeted cuts before resorting to across–the–board reductions. For example, we recommend reducing funding for physical education courses offered by community colleges, aligning special education funding with revised student counts, and reducing the number of times the state administers the high school exit exam. We have identified more than $650 million in these targeted savings proposals. (We also have identified additional education–related savings outside of Proposition 98.)

Make Other Cuts, As Needed, From General Purpose Monies. Even if the state were to take all our targeted reductions, it likely still would need to make additional cuts. The Legislature could consider making these reductions, as needed, to K–12 revenue limits, California Community College (CCC) apportionments, and the K–12 flex item (or some combination thereof). For every 1 percent cut in these areas, the state would achieve about $435 million in savings ($310 million from K–12 revenue limits, $55 million from CCC apportionments, and $70 million from the K–12 flex item). As detailed in previous reports, we continue to recommend combining these additional cuts with additional flexibility for districts (both from categorical program requirements and education mandates).

Reasonable Estimates, Reasonable Revenue Assumptions. We believe that the administration’s estimate of the size of the state’s budget problem in 2010–11 is sound. As noted earlier, our own updated economic and revenue forecasts are very close to those of the administration. As such, we believe the May Revision revenue forecast is quite reasonable and realistic. Under our forecast, we expect revenues to be slightly higher in the final two months of 2009–10 and leave the state about $400 million better off. In 2010–11, our expectation for the big three tax revenues is about $1 billion (1 percent) higher than the administration. The largest difference relates to the PIT and, specifically, capital gains.

Stubborn Structural Deficit Would Persist. As we described in our November 2009 publication,

California’s Fiscal Outlook, under then–current law, the state faced a lingering General Fund budget gap around $20 billion through at least 2014–15. Little has changed since then to shrink that amount. As part of our review of the May Revision, we have estimated how this persistent long–term problem would change under the Governor’s proposals. Specifically, our forecast combines our assessment of revenue and expenditure trends with the assumption that all of the May Revision’s proposals are adopted by the Legislature. In addition, except in clear cases when a proposal is unworkable (such as the Governor’s proposed increase in pension contributions for current employees), we have given the administration the “benefit of the doubt” that its proposals will achieve the desired level of savings. Furthermore, consistent with current law, we generally assume no future cost–of–living adjustments for state programs or pay increases for state employees throughout the forecast period. Given these assumptions, our out–year forecast should be viewed as a very best case scenario.

Under these assumptions, the ongoing gap between General Fund revenues and expenditures would be significantly reduced but not eliminated. As shown in Figure 7, shortfalls would range between $4 billion and $7 billion through 2014–15. (The peak of the shortfall in 2012–13 reflects the repayment of the state’s $2 billion loan from local governments.) Given this ongoing shortfall even under the sharp spending reductions proposed by the Governor, it is unrealistic for the Legislature to eliminate the long–term problem entirely this year. We, however, urge the Legislature to consider the out–year implications of its 2010–11 budget decisions and aim to achieve roughly the same level of progress as the Governor in tackling the state’s structural deficit.

Any Budget Adopted This Year Will Include Some Risks. As has been the case in several recent budgets, the Governor’s budget proposals include several billion dollars of assumptions—both on the revenue and expenditure sides of the ledger—that carry with them moderate or major implementation risk. In fact, we cannot imagine any balanced budget solution this year that could avoid some level of risky assumptions. Federal MOE and similar requirements in various programs—including some related to provisions of last year’s economic stimulus legislation—limit the state’s budget options. In some other programs, such as those requiring changes in eligibility or caseloads, significant savings cannot be achieved quickly. It is clear that nearly all of the easy budget–balancing solutions for California are gone.

Legislature Can Take Actions to Mitigate Some of the Risks. The Legislature cannot control what Congress and the President do to extend enhanced federal funding for health and social services programs, nor can it control what the federal government does to affect the state’s estate tax revenues. It also cannot control what the voters decide in the November election, as described in the box below.

|

The Legislature has placed an $11 billion water bond proposal on the November 2010 ballot. In addition, although not all of them have officially qualified, it is now expected that the November 2010 ballot will include about ten initiatives. If approved by the voters, a number of these measures could directly affect the Legislature’s budget plans. Some would improve the budget situation, even as others could reverse budget–balancing decisions. Historically, the state budget has not assumed the passage of voter initiatives at upcoming elections, but the Legislature may wish to have contingency plans in place depending on the outcome for several November ballot measures. While we are still reviewing the measures for our analyses in the November 2010 ballot pamphlet, we highlight some of the key measures with budget implications below.

Two Proposed Initiatives Potentially Could Reverse Budget Decisions. A measure designed to protect local government revenues would apply its provisions to all legislative actions taken after October 20, 2009. As such, it might affect several major budget solutions provided in the gas tax swap package (Chapters 11 and 12, Statutes of 2009–10 Eighth Extraordinary Session [ABX8 6 and ABX8 9, Committee on Budget]) and the Governor’s May Revision proposals. These solutions total about $1.8 billion in General Fund relief in the current and budget years combined. The solutions include using revenues from fuel taxes to pay transportation debt service and to provide loans to the General Fund—uses that generally would not be permitted under the measure. The initiative also would limit the state’s authority to increase redevelopment payments to schools (beyond the $350 million required in 2010–11 under existing law) or make other changes in local finance.

Another measure would amend the Constitution to broaden the definition of a state tax, local special tax, and state tax increase to include many measures that the Legislature and local governing bodies currently may approve by a majority vote. Under the measure, more revenue measures would require approval by a two–thirds vote of the Legislature or two–thirds of the local electorate. By expanding the scope of what is considered a tax or a tax increase, the measure would make it more difficult for the state to enact a broad range of measures that generate revenues or modify existing taxes. The measure specifies that any state legislation enacted after January 1, 2010, that is inconsistent with its provisions would become inoperative 12 months after the state’s voters approve the initiative, unless the Legislature reenacts the legislation in compliance with the initiative’s provisions. (As such, any implications of the measure on enacted measures would not be felt until 2011–12.)

Other Initiatives Would Raise General Fund Resources. On the other hand, several proposed measures would improve the state’s fiscal condition by adding additional revenues. One measure would reverse recent budget actions that lower corporate tax revenues. If passed, the measure would increase corporate tax receipts by hundreds of millions of dollars in 2010–11, growing in subsequent years. In addition, a measure to impose a vehicle surcharge would allow a reduction in costs to operate state parks, and a measure to legalize marijuana–related activities could increase state tax revenues. |

In enacting a credible, balanced budget for 2010–11, however, the Legislature can take actions to mitigate some budget risks. Careful, clearly crafted trailer bills, particularly those relating to reductions in health and social services programs, can ensure that budget–balancing actions have the strongest possible chance of withstanding judicial scrutiny. Furthermore, if it assumes certain expenditure reductions, the Legislature needs to pass legislation to give departments a meaningful chance of actually achieving budgeted savings. For example, in our view, the prison medical care Receiver will have little chance of achieving the full $811 million of savings assumed in the Governor’s budget package unless the Legislature passes measures to assist him in doing so. In addition, lawmakers should not assume that the administration can achieve hundreds of millions or billions of dollars of General Fund personnel savings on its own without prompt enactment of legislation that (1) facilitates major changes in operations, sentencing, or staffing in the prison system (which is responsible for about two–thirds of non–university General Fund personnel costs), or (2) enacts reductions in state employee pay or health benefits. These pay and benefit reductions may result either from collective bargaining or the Legislature’s use of its constitutional powers to appropriate funds for state personnel costs.

The Governor’s May Revision proposes to eliminate the CalWORKs program effective October 1, 2010, and state–funded child care programs effective July 1, 2010. Combined with savings assumed in January, these proposals would reduce General Fund spending by over $2.5 billion. These programs are core pieces of the state’s safety net, and we therefore recommend that the Legislature reject these proposals.

Core Programs for State’s Neediest Families. Since the 1930s, CalWORKs, or its federally authorized predecessor program, has provided low–income families with children with cash assistance to meet their basic needs. Following enactment of the 1996 federal welfare reform legislation, the program added a substantial welfare–to–work component, whereby able–bodied adult recipients were provided with child care and/or other training and services so that they could enter the labor force. The cash grants, in combination with food stamp benefits, provide families with enough support to stay out of deep poverty (which is defined as 50 percent of the federal poverty level). Similarly, subsidized child care helps current and former CalWORKs recipients as well as other low–income families maintain employment, serving as an important complement to adults’ efforts to obtain and keep jobs. Because existing eligibility criteria restricts services to families earning less than 75 percent of the state median income, the child care program helps some of the neediest families in California.

Both Programs Provide Access to Large Federal Funding. By eliminating CalWORKs and child care, the state would be foregoing major amounts of federal funding. In CalWORKs, the state would forego the annual $3.7 billion federal Temporary Assistance to Needy Families (TANF) block grant. Moreover, California would forego hundreds of millions of dollars in Emergency Contingency Funds (ECF) authorized by the 2009 federal stimulus package. (The ECF provides 80 percent federal financial participation in costs for cash grants, nonrecurring short–term assistance, and subsidized employment which exceed their corresponding costs in 2007.) Although the ECF is scheduled to expire on September 30, 2010, both the President’s budget and the Governor’s budget assume it will be extended for one more year.

Despite the elimination of all state child care funding, the Governor assumes the state would continue to receive all anticipated federal funding for child care and could thereby continue to offer care to a small subset of currently served children. (Federal child care funds total about $660 million in 2010–11, including $550 million in ongoing federal block grant funds and $110 million in one–time stimulus funds.) It is unclear, however, if California could continue to receive the same level of federal funding given the absence of state funding. While California might be able to use state funding for preschool and applicable local funds to help meet some federal match requirements, the state could lose at least some federal funding.

Proposal Would Shift Costs to Counties and Elsewhere. Counties are responsible under state law for providing cash assistance to families who are both unable to support themselves and ineligible for other state and federal programs. The elimination of CalWORKs would make most low–income families eligible for county general assistance (GA) programs, potentially resulting in county costs exceeding $1 billion annually. It is not clear how counties would pay for this obligation—particularly in the context of the recession’s hit on counties’ own revenues and the Governor’s other proposals that would be financially detrimental to counties. Counties have no such obligation to provide welfare–to–work services and child care. Absent these services, however, it will be difficult for many families to become self–sufficient and exit county GA programs.

The administration’s proposal would also result in some eligibility determination costs being shifted from CalWORKs to Medi–Cal. The budget plan does not take this into account. We estimate these state costs to be roughly $200 million annually.

Programs Can Still Contribute Savings. While we recommend rejecting the complete elimination of these programs, we believe that the state can generate substantial General Fund savings in these two program areas. For example, the state could make targeted child care reductions while still providing subsidized care to the neediest families. Most notably, as outlined in our February report,

The 2010–11 Budget: Proposition 98 and K–12 Education, the state could reduce eligibility ceilings and provider reimbursement rates. While this would achieve notably less savings than completely eliminating subsidized child care, targeted reductions would allow the state to preserve services for the lowest income families. Moreover, by applying the same eligibility reforms across all child care programs, the state could address some existing inconsistencies between the state’s CalWORKs and non–CalWORKs child care programs. (Currently, former CalWORKs recipients who begin to earn more can continue to receive child care services even as children from lower income families linger on waiting lists.)

Given the 80 percent federal funding stream which is likely to exist through October 2011, we believe there is limited General Fund benefit from making substantial CalWORKs reductions during 2010–11. However, once the ECF expires, all savings from CalWORKs reductions accrue to the state General Fund with no loss of federal funds (because the block grant is fixed). Accordingly, given our projections of ongoing deficits, the Legislature may need to make substantial reductions in CalWORKs in 2011–12.

Throughout the spring, our office has provided alternative spending reduction proposals to the Legislature. (Our web site—www.lao.ca.gov—contains an online list of our updated

2010–11 budget findings and recommendations, as well as our published reports.) In many areas, our alternatives reduce program spending by a lesser amount than the Governor in order to preserve services for those most in need. In some areas of the budget, we recommend that the Legislature adopt more savings than imposed by the Governor. In particular, we believe the Legislature should achieve substantially more savings from the universities, trial courts, and public safety local assistance programs. These spending reductions—in conjunction with other budget actions—could facilitate maintenance of the state’s core programs.

More Revenues Could Ameliorate the Most Severe Cut Proposals. The Governor presents Californians with a clear vision of the types of severe program reductions that are necessary if the budget were balanced without some additional revenue increases this year. Alternatively, some of the most severe cuts proposed by the Governor could be avoided by adopting selected revenue increases—from fee increases and other nontax revenues, changes to tax expenditure programs, delays in previously scheduled tax reductions or expirations, and targeted tax increases. We urge the Legislature to put these types of solutions in the mix.

We have previously presented the Legislature with a menu of revenue options to consider from the following categories:

- Delays in Previously Scheduled Tax Reductions or Expirations. In its January trigger proposals (withdrawn as part of the May Revision), the administration suggested delaying the implementation of recent tax changes (such as the optional single sales factor) by one year. We recommend the Legislature consider delaying these provisions for two years in recognition of the 2010–11 budget challenges, as well as the loss of nearly $10 billion in other temporary taxes in 2011–12.

- Changes to Tax Expenditure Programs. Tax expenditures are credits, exemptions, and deductions intended to produce a particular policy benefit through the tax code. Yet, some of these programs have failed to prove their effectiveness—such as enterprise zones—and others result in a disparate treatment of income. As with programs on the spending side of the budget, we recommend that the Legislature eliminate those lower priority programs in order to preserve more critical ones.

- Fee Increases. Some fee increases benefit the General Fund and make sense from a policy perspective. For example, we have proposed the establishment of a wildland fire protection fee—an alternative to the Governor’s emergency response initiative proposal—that would place a charge on owners of structures in areas where the state has responsibility for wildland fire management. We also have recommended community college fee increases, which would not affect financially needy students (because they are eligible to receive full fee waivers) and would be fully offset for most middle–income students (who quality for federal tax credits).

- Targeted Tax Rate Increases. Finally, we have suggested the Legislature could consider targeted tax rate increases. Given the fragile state of the economy and the level of these taxes relative to other states, we discourage increasing the state’s broad–based big three taxes (personal income, sales and use, and corporation taxes) above their current levels. We have, however, suggested two proposals that would raise other tax rates while adhering to sound tax policy principles. First, many economists believe that taxes on alcohol do not fully compensate for the societal costs associated with drinking. Since alcohol tax rates have not been updated for inflation since 1991, such an adjustment could produce over $200 million of General Fund benefit. In addition, we suggest permanently aligning the VLF—currently increased temporarily under provisions of the February 2009 budget package—with local property tax rates, as it represents a tax on property.

The last decade has provided some of the state’s most challenging budget situations—including last year’s plan addressing roughly $60 billion in solutions. Yet this year’s budget situation may prove to be the most difficult in recent memory. All of the major options available to the Legislature to close the budget gap will be difficult. The two basic avenues to balancing this budget—sharply lower spending in some programs and higher revenues—each result in negative consequences for the economy, jobs, and the Californians most directly affected. While much of the budget process will focus on how to minimize the damage to taxpayers and program service levels, we urge elected leaders to use this crisis to better prepare the state’s budget and its government to cope with future economic downturns. By thinking now about the longer term, the Legislature and the Governor can help bring the long–term structural deficit down. Among the actions that policy makers could consider this year are:

- A Stronger State Rainy Day Fund. Along with others, we have proposed improved mechanisms for setting aside unexpected budget surpluses to build a stronger state rainy day fund.

- State–Local Realignment. The Governor has proposed to give local governments responsibility and funding for criminal justice programs that they can better administer. Our office, legislative leaders, and others have suggested additional shifts. For instance, the state–local relationship for the provision of some health and social services should be reconsidered, particularly within the context of federal health care reform.

- Actions Now That Can Reduce the Structural Deficit. With a continuing structural deficit, the state needs to adopt actions that may require implementation time but can save money later. For example, we recommend the state take actions now relating to kindergarten and after school programs that could achieve more than $900 million in savings in 2011–12. Similarly, sharply increasing pension and retiree health costs should prompt consideration of major changes in these benefits for future state and local hires, which would save billions in future decades.

Taking steps in these areas now would significantly improve the state’s future prospects.