February 27, 2013

Overview of Health and Human Services Budget. The Governor’s budget proposes $20.3 billion from the General Fund for health programs—a 3.4 percent increase over 2012–13 estimated expenditures—and $8 billion from the General Fund for human services programs—a 7.9 percent increase over 2012–13 estimated expenditures. For the most part, the year–over–year budget changes reflect caseload changes, technical budget adjustments, and the implementation of previously enacted policy changes, as opposed to new policy proposals. On the health side, the budget reflects a net increase of $354 million from the General Fund for Medi–Cal, in part reflecting (1) increased enrollment among the currently eligible, but unenrolled, Medi–Cal population under the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) and (2) the shift of Healthy Families Program (HFP) enrollees to Medi–Cal that is currently underway. On the human services side, the budget reflects General Fund expenditure increases in all major programs, especially in the California Work Opportunity and Responsibility to Kids (CalWORKs) program—a $341 million, or 21.4 percent, increase that includes increased spending on employment services.

Fiscal Impact of Proposed Medi–Cal Expansion Not Reflected in Budget. While the Governor has proposed that the state adopt the optional Medi–Cal expansion under ACA, the budget does not reflect the fiscal effects from such expansion. Please see our February 2013 report, The 2013–14 Budget: Examining the State and County Roles in the Medi–Cal Expansion, for our analysis of the proposed expansion. The budget also does not reflect potential costs and savings related to other ACA provisions. These fiscal effects largely depend on pending policy decisions.

Medi–Cal—Uncertain Budgetary Savings. The Governor’s Medi–Cal budget proposal assumes General Fund savings from (1) prior–year budget actions that are currently being challenged in litigation or for which federal approval has not been obtained, (2) a new proposal to achieve managed care efficiencies, (3) the proposed reauthorization of the gross premium tax on managed care plans, and (4) the proposed extension of the hospital quality assurance fee. Accordingly, the level of savings assumed in the Governor’s proposal is subject to significant uncertainty and contingent on legislative action to reauthorize or extend taxes or fees.

HFP Transition to Medi–Cal Generally Proceeding as Planned, With Some Delays. We find that the administration has generally complied with various statutory requirements guiding the transition of HFP enrollees to Medi–Cal. The budget reflects erosion of the initially projected General Fund savings from the transition, in part due to implementation delays to address concerns about potential interruptions to continuity of care and other issues.

Developmental Centers (DCs) Need Improved Oversight. While several governmental and private entities perform oversight to ensure the health and safety of residents of the state’s DCs, there have continued to be allegations and findings of resident abuse and deficiencies in the management, training, and staffing of DCs. To strengthen oversight of the DCs, we recommend that the Legislature create an Office of the Inspector General (OIG), organizationally independent from the Department of Developmental Services (DDS), to oversee the DCs.

CalWORKs Budget Reflects Implementation of Recent Major Program Changes. Several recent changes to CalWORKs are being implemented currently or are scheduled to be implemented in 2013–14. These changes include the phase–out of exemptions from welfare–to–work (WTW) requirements and the introduction of a new 24–month limit on adult eligibility for CalWORKs benefits under state work participation rules that are more flexible than the federal rules that apply after 24 months. The budget reflects a number of strategies to help the state meet federally required work participation rates, and we think that the administration’s approach is a reasonable one. While we recommend that the Legislature augment CalWORKs employment services funding, we recommend that it determine the amount of such augmentation by considering the level of service it expects given its recent policy actions and the level of funding it deems appropriate in light of its priorities for the CalWORKs program.

In–Home Supportive Services (IHSS) Budget Proposal Has Risks. The Governor’s budget for IHSS assumes that the state will ultimately prevail in ongoing litigation regarding a 20 percent across–the–board reduction in IHSS service hours (triggered as a result of the 2011–12 budget package), allowing this budget savings solution to be implemented beginning on November 1, 2013. We think that the Governor’s budget assumption is subject to significant uncertainty. In light of the fiscal and policy concerns that we identify with respect to the 20 percent reduction, we recommend that the Legislature repeal the 20 percent reduction and instead continue a 3.6 percent across–the–board reduction that would otherwise sunset at the end of 2012–13. This action should have a better chance at achieving savings than the Governor’s proposal.

Background on Health Programs. Many of California’s major health programs are administered at the state level by several different departments. Some departments administer more than one health program. For example, the Department of Health Care Services (DHCS) administers Medi–Cal—California’s version of the federal Medicaid Program—as well as the California Children’s Services Program and other programs. The programs administered by state departments provide a variety of benefits to California’s citizens, including purchasing health care services for qualified low–income persons and performing various public health functions.

Most state health programs are administered at the state level by one of the following five departments: (1) DHCS, (2) Department of Public Health (DPH), (3) Managed Risk Medical Insurance Board (MRMIB), (4) DDS, and (5) Department of State Hospitals (DSH). The actual delivery of many health services often takes place at the local level and is carried out by local government entities, such as counties, and by private entities, such as commercial health plans. (Funding provided for these types of services delivered at the local level is known as “Local Assistance.”) However, there are significant exceptions to the local service delivery model. For example, DSH operates five state hospitals for the mentally ill and DDS operates four DCs that provide developmentally disabled individuals with 24–hour care. Both the state hospitals and the DCs are staffed with state employees who directly provide services to the residents of these state institutions.

Overview of Health Budget Proposal. The 2013–14 Governor’s Budget proposes $20.3 billion from the General Fund for health programs. This is an increase of $668 million—or about 3.4 percent—above the revised estimated 2012–13 spending level as shown in Figure 1. The net increase reflects increases in caseload and changes in utilization of services as well as the impact from major ongoing initiatives.

Figure 1

Major Health Programs and Departments—Budget Summary

General Fund (Dollars in Millions)

|

|

2011–12 Actual

|

2012–13 Estimated

|

2013–14 Proposed

|

Change From 2012–13

|

|

Amount

|

Percent

|

|

Medi–Cal—Local Assistance

|

$15,097

|

$14,897

|

$15,251

|

$354

|

2.4%

|

|

Department of Developmental Services

|

2,563

|

2,604

|

2,759

|

155

|

5.9

|

|

Department of State Hospitals

|

1,329

|

1,321

|

1,457

|

136

|

10.0

|

|

Healthy Families Program (HFP)—Local Assistancea

|

271

|

163

|

19

|

–144

|

–88.0

|

|

Department of Public Health

|

125

|

131

|

114

|

–17

|

–13.0

|

|

Department of Alcohol and Drug Programs (DADP)b

|

37

|

34

|

—

|

–34

|

—

|

|

Other Department of Health Care Services programs

|

59

|

136

|

130

|

–6

|

4.4

|

|

Emergency Medical Services Authority

|

7

|

7

|

7

|

—

|

—

|

|

All other health programs (including state support)

|

146

|

346

|

570

|

224

|

64.7

|

|

Totals

|

$19,634

|

$19,639

|

$20,307

|

$668

|

3.4%

|

Summary of Major Budget Proposals and Changes. As shown in Figure 1, the Governor’s proposed General Fund expenditures for 2013–14 reflect state–level organizational changes in the departments that will administer certain health programs. General Fund spending for HFP decreases from a revised estimate of $163 million in the current year to $19 million in the budget year, to account for the shift of HFP enrollees from HFP to Medi–Cal that is currently underway. There is a corresponding increase in the Medi–Cal budget to reflect this ongoing shift. Similarly, the General Fund spending for the Department of Alcohol and Drug Programs (DADP) decreases from a revised estimate of $34 million in 2012–13 to no expenditures in 2013–14 to reflect the department’s proposed elimination and transfer of all substance use disorder programs to DHCS. (The DADP’s Office of Problem Gambling would be transferred to DPH under the Governor’s plan.) We discuss the shift of HFP to DHCS and the proposed elimination of DADP in more detail later in this analysis.

The budget plan reflects the fiscal effects of recently adopted major policy initiatives, including the Coordinated Care Initiative (CCI) that was adopted as part of the 2012–13 budget package. Broadly, the CCI is intended to better coordinate the care of about 560,000 Medi–Cal beneficiaries who are also eligible for Medicare (known as dual eligibles) by shifting them from fee–for–service (FFS) to managed care beginning in 2013–14. The budget plan reflects both costs and savings associated with implementing the CCI. For information on CCI implementation, please see our report,

The 2013–14 Budget: Coordinated Care Initiative Update. The budget plan also reflects some, but not all, of the costs associated with the implementation of ACA also known as federal health care reform. For example, it includes a “placeholder” of $350 million General Fund for increased costs associated with additional enrollment among the currently eligible, but unenrolled Medi–Cal population as a result of changes to the eligibility determination process under ACA. However, the budget plan does not adjust for the fiscal impact to the state of the optional expansion of Medi–Cal eligibility that the Governor has committed to implement in January of 2014 and some other ACA implementation issues. For information on ACA implementation of the optional Medi–Cal expansion, please see our report,

The 2013–14 Budget: Examining the State and County Roles in Medi–Cal Expansion.

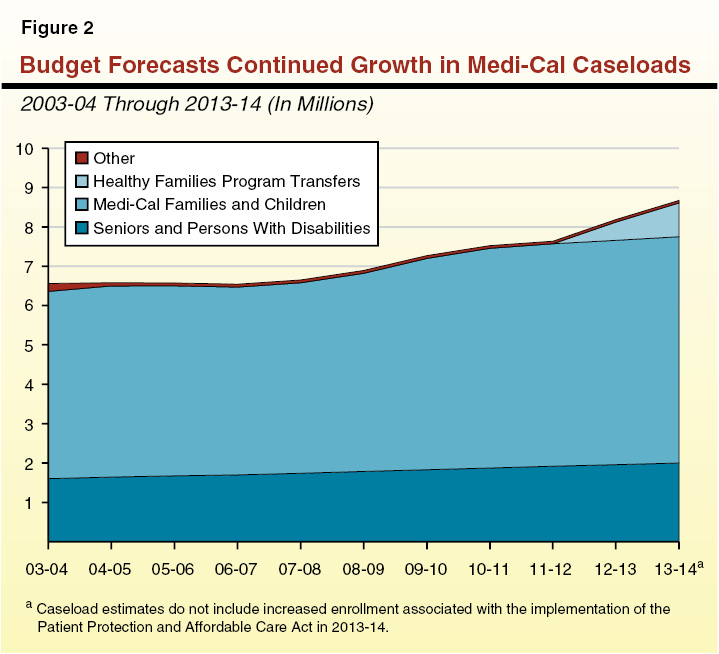

Caseload trends are one important factor influencing state health care expenditures. Below we highlight the caseload trends assumed in the Governor’s budget for Medi–Cal—by far the largest state–administered health program.

Medi–Cal Caseload. Figure 2 illustrates the budget’s projected caseload trends for Medi–Cal, divided into four groups: (1) families and children, (2) seniors and persons with disabilities (SPDs), (3) HFP transfers, and (4) others. The Governor’s budget plan assumes that the 2012–13 caseload for Medi–Cal will increase by about 153,000 compared to the number assumed in the 2012–13 Budget Act. The Governor’s budget plan also assumes a large increase in caseload will occur during 2013–14. Specifically, the overall caseload is expected to increase by about 486,000 average monthly eligibles (5.9 percent) to a total of about 8.7 million in 2013–14. This year–over–year increase can mainly be attributed to the HFP program transfers. The budget plan assumes that about 393,000 HFP enrollees will shift to Medi–Cal in 2013–14. This is in addition to the 465,000 HFP enrollees that the budget plan assumes will shift from HFP to Medi–Cal in 2012–13.

Background on Human Services Programs. California’s major human services programs provide a variety of benefits to its citizens. These include income maintenance for the aged, blind, or disabled; cash assistance and welfare–to–work services for low–income families with children; protecting children from abuse and neglect; providing home care workers who assist the aged and disabled in remaining in their own homes; collection of child support from noncustodial parents; and subsidized child care for low–income families.

Most social services are administered at the state level by DSS, the Department of Child Support Services, and the other Health and Human Services Agency (HHSA) departments. The actual delivery of many services takes place at the local level and is carried out by 58 separate county welfare departments. The major exception is Supplemental Security Income/State Supplementary Program (SSI/SSP), which is administered mainly by the U.S. Social Services Administration.

As a result of 2011 legislation, certain state program responsibilities and revenues in the human services area have been realigned to local governments (primarily counties). Specifically, beginning with the 2011–12 budget, the budget reflects shifts to counties of about $1.1 billion of General Fund costs in the CalWORKs program and about $1.6 billion in child welfare and adult protective services General Fund costs. As a result of these changes, the state’s role with respect to child welfare and adult protective services is largely one of oversight of county administration of these program areas.

Overview of Human Services Budget Proposal. The Governor’s budget proposes expenditures of $8 billion from the General Fund for human services programs in 2013–14. As shown in Figure 3, this reflects an increase of $585 million—or 7.9 percent—above revised General Fund expenditures in 2012–13.

Figure 3

Major Human Services Programs and Departments—Budget Summary

General Fund (Dollars in Millions)

|

|

2011–12 Actual

|

2012–13 Estimated

|

2013–14 Proposed

|

Change From

2012–13 to 2013–14

|

|

Amount

|

Percent

|

|

SSI/SSP

|

$2,721.6

|

$2,764.8

|

$2,817.4

|

$52.6

|

1.9%

|

|

CalWORKs

|

1,156.9

|

1,590.3a

|

1,930.8b

|

340.5

|

21.4

|

|

In–Home Supportive Services

|

1,725.9

|

1,723.2

|

1,808.2

|

85.0

|

4.9

|

|

County Administration and Automation

|

569.4

|

699.6

|

769.4

|

69.8

|

10.0

|

|

Department of Child Support Services

|

306.6

|

307.1

|

312.9

|

5.8

|

1.9

|

|

Department of Rehabilitation

|

54.5

|

55.3

|

56.6

|

1.3

|

2.4

|

|

Department of Aging

|

31.8

|

32.1

|

32.2

|

0.1

|

0.3

|

|

All other social services (including state support)

|

232.3

|

244.0

|

273.6

|

29.6

|

12.1

|

|

Totals

|

$6,799.0

|

$7,416.4

|

$8,001.1

|

$584.7

|

7.9%

|

Summary of Major Budget Proposals and Changes. As shown in Figure 3, the budget reflects a growth in General Fund expenditures across all major human services programs. The 21.4 percent increase ($341 million) in CalWORKs General Fund expenditures can largely be explained by two factors—a $143 million proposed augmentation for employment services (to some extent driven by policy reforms adopted in the 2012–13 budget package) and a $139 million year–over–year increase in the amount of federal Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) monies transferred to the California Student Aid Commission (CSAC). (The latter item increases the proposed CalWORKs General Fund expenditures by a like amount, but does not increase overall CalWORKs program expenditures.) We discuss both of these budget changes in further detail below.

The 10 percent increase ($70 million) in General Fund expenditures in the County Administration and Automation budget line item largely reflects a $44 million proposed augmentation for two welfare automation projects, also discussed further below.

Finally, the 4.9 percent net growth ($85 million) in IHSS General Fund expenditures reflects a multitude of budget adjustments—both on the cost and savings fronts—that do not signify new policy proposals of the Governor. For example, on the cost front, the budget includes General Fund increases in IHSS of (1) $59 million to restore funding due to the one–time nature in the 2012–13 enacted budget of a 3.6 percent across–the–board reduction in service hours and (2) about $49 million due to caseload growth. These and various other additional costs in IHSS are partially offset by the budget’s assumption that the 20 percent across–the–board reduction in service hours that was triggered by the 2011–12 budget package will begin to be implemented in November of 2013, generating partial–year savings of $113 million in 2013–14.

Varied Growth Through Recession. While caseload grew for most of the state’s human services programs during the recent recession, there was substantial variability in the growth rate across programs. (One key exception is the state’s foster care caseload, which has declined since 2001 and through the recession. In part, this reflects the creation of the Kinship Guardian Assistance Payment program in 2000 that facilitates a permanent placement option for relative foster children outside of the foster care system.) For example, over the 2007–08 to 2011–12 period, the CalFresh (formerly Food Stamps) and CalWORKs caseloads increased by a total of 97 percent and 27 percent, respectively, while the IHSS caseload—less susceptible to economic fluctuations—increased by a total of 8 percent. The SSI/SSP caseload grew modestly during this time period (a total of 3.4 percent)—in part reflecting recent grant reductions that in effect reduced the eligible population—and is projected to grow relatively modestly in 2013–14.

We now turn more specifically to caseload trends in the IHSS and CalWORKs programs and the budget’s assumptions regarding caseload for these two programs in 2013–14.

IHSS Caseload Projected to Decrease Modestly in 2013–14. The budget projects the average monthly caseload for IHSS to be 418,890 in 2013–14—a 1 percent decrease below the most recent estimate of the 2012–13 caseload. We discuss the administration’s projection in further detail below in the IHSS write–up in this report. For historical perspective, the IHSS caseload has remained relatively flat throughout most of the five–year period from 2009–10 to 2013–14, in part reflecting policy changes that constrained caseload growth.

Recent CalWORKs Caseload Decline Projected to Reverse During 2013–14. In the midst of the recent recession, the CalWORKs caseload rose substantially. The recent–year caseload peaked in June of 2011 at over 597,000 cases. Since that time, due to enacted policy changes and a slowly improving labor market, the caseload has been declining. The administration projects the average monthly caseload in 2012–13 to decline to 563,000 cases. In contrast, the average monthly caseload in 2013–14 is projected to increase by 1.5 percent to over 572,000, in part reflecting various policy changes in the enacted 2012–13 budget (discussed under the CalWORKs write–up elsewhere in this report) that should result in fewer case exits. In general, we find the administration’s caseload estimate for 2013–14 to be reasonable. In the long run, the caseload should continue to show a downward trend as the labor market continues to improve.

As part of his 2012–13 budget proposal, the Governor proposed shifting all enrollees in HFP—administered by MRMIB—to Medi–Cal—administered by DHCS—over a nine–month period beginning in October 2012. The administration stated that the proposal would have several benefits, including (1) generating General Fund savings, (2) improving continuity of care by reducing the number of children who transition between Medi–Cal and HFP on an ongoing basis, and (3) implementing some requirements of ACA early. (Under ACA, a portion of the HFP enrollees will become eligible for Medi–Cal on January 1, 2014.) (For more information on the Governor’s 2012–13 budget proposal for HFP, and extensive background information on HFP and Medi–Cal, please see our report,

The 2012–13 Budget: Analysis of the Governor’s Healthy Families Program Proposal.) In response, the Legislature enacted Chapter 28, Statutes of 2012 (AB 1494, Committee on Budget), to implement a modified version of the Governor’s proposal to shift all HFP enrollees into Medi–Cal (hereinafter referred to as the “transition”). Notably, the Legislature’s plan delayed the start of the transition to January 2013, included direction on how the transition is to be conducted, and provided for legislative oversight. This report provides a status update on the transition.

At the time this analysis was prepared, some children had shifted from HFP to Medi–Cal, while other children remained in HFP. Throughout this analysis, we will refer to all children who meet the eligibility requirements for the federal Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) as the CHIP population, regardless of whether they are currently enrolled in HFP or Medi–Cal. We provide more information on CHIP in the background section of this analysis below.

Summary of Analysis. In this analysis, we begin by providing a brief overview of HFP. We then summarize key provisions of Chapter 28 including: (1) the timeframe for the transition, (2) reporting requirements to ensure network adequacy and continuity of care, and (3) requirements involving stakeholder involvement and written notices to HFP enrollees. We then describe the erosion of assumed General Fund savings in 2012–13 and 2013–14 due to delays in the implementation of the transition and other factors. We also analyze recent caseload trends and recommend that the administration be required to report at budget hearings on the causes of the recent decline in the CHIP population and its potential fiscal impact.

The HFP Is California’s CHIP. The CHIP provides health coverage to children in families that are low income, but with incomes too high to qualify for Medicaid. (In California, the federal Medicaid Program that provides health care services to qualified low–income persons is known as Medi–Cal.) Under the CHIP, for every dollar the state spends, the federal government provides roughly a two–dollar match.

As of December 31, 2012 (prior to the shift of some HFP enrollees to Medi–Cal, which began on January 1, 2013), HFP provided health insurance for 852,600 children up to age 19 in families with incomes above the thresholds needed to qualify for Medi–Cal, but below 250 percent of the federal poverty level (FPL). (The FPL is currently $22,050 in annual income for a family of four.) The MRMIB provides coverage by contracting with health plans that provide health, dental, and vision benefits to HFP enrollees. All HFP enrollees are enrolled in managed care plans. (Under managed care, health plans provide coverage and are reimbursed on a capitated basis. The health plans assume some financial risk, in that they may incur costs to deliver the necessary care that are more or less than the capitated rate. Most HFP plans are regulated by the Department of Managed Health Care (DMHC), which monitors financial solvency, evaluates provider network adequacy, conducts quality performance audits, and responds to beneficiary grievances.)

States Have Option to Combine Medicaid and CHIP Programs. A state may use federal CHIP funds to create a stand–alone program, such as HFP, or expand its Medicaid Program to include children in families with higher incomes. In both options, states receive the two–dollar federal match for every state dollar to provide coverage for the CHIP population.

Chapter 28 authorized the transition and divided it into four phases. Additionally, it contained several provisions to ensure legislative oversight, continuity of care, network adequacy, and stakeholder involvement. We describe these provisions in more detail here.

The Health Coverage Transition Will Take Place in Four Phases. When the 2012–13 Budget Act was enacted, the CHIP population was projected to be almost 880,000 by the time of the transition. This population was scheduled to be shifted to Medi–Cal managed care in four phases.

- Phase One. The first phase is authorized to begin no earlier than January 1, 2013 and includes children enrolled in HFP managed care plans that also contract with Medi–Cal. Generally, the children who are most likely to be able to stay with their current primary care provider will transition to Medi–Cal first. When the 2012–13 Budget Act was enacted, this phase was expected to include about 415,000 children.

- Phase Two. The second phase is authorized to begin no earlier than April 1, 2013 and includes children enrolled in HFP managed care plans that subcontract with a Medi–Cal managed care plan. When the 2012–13 Budget Act was enacted, this phase was expected to include about 249,000 children.

- Phase Three. The third phase is authorized to begin no earlier than August 1, 2013 and includes children enrolled in HFP managed care plans that do not contract with Medi–Cal or subcontract with a Medi–Cal plan. When the 2012–13 Budget Act was enacted, this phase was expected to include about 173,000 children.

- Phase Four. The fourth phase is authorized to begin no earlier than September 1, 2013 and includes children enrolled in HFP health care plans who live in a county where Medi–Cal managed care is not available. They will be transitioned into Medi–Cal FFS, unless a Medi–Cal managed care plan becomes available. (In Medi–Cal FFS, a health care provider receives a payment from DHCS for each medical service provided to a Medi–Cal beneficiary. Beneficiaries generally may obtain services from any provider who has agreed to accept Medi–Cal patients.) When the 2012–13 Budget Act was enacted, this phase was expected to include about 42,800 children.

Written approval from the federal Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) is required prior to implementing each phase of the transition. (As discussed below, CMS approval for phase one implementation was obtained prior to January 1, 2013.) After the transition is complete, the administration must apply for federal approval to administer the CHIP program as an integrated program with Medi–Cal. For more information on the how the federal government is monitoring the transition, see the nearby box.

As part of the federal approval process, the Department of Health Care Services has worked with Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services to develop a framework for monitoring the transition. This monitoring will include collecting data on children who have transitioned from the Healthy Families Program to Medi–Cal. The monitoring framework has several objectives, including:

- Maintaining access to health care, dental care, behavioral and mental health services, and alcohol and substance use services.

- Providing continuity of care for children who are transitioning.

- Ensuring that the Children’s Health Insurance Program populations applying for Medi–Cal will be enrolled quickly and accurately into Medi–Cal.

Metrics will be collected on a monthly, quarterly, or annual basis to measure whether these objectives are achieved.

Dental Coverage Will Be Transitioned Concurrently With Health Coverage. Under Chapter 28, the HFP enrollees will transition their dental coverage at the same time that their medical coverage transitions. The transition will occur differently for those HFP enrollees located in Los Angeles and Sacramento counties and those HFP enrollees located elsewhere.

- HFP Enrollees Outside of Los Angeles and Sacramento Counties Shift to Denti–Cal. The HFP enrollees living outside of Los Angeles and Sacramento counties will receive dental care through Denti–Cal, Medi–Cal’s FFS dental program.

- HFP Enrollees in Los Angeles County Shift to Dental Managed Care andDenti–Cal. About 215,700 HFP enrollees live in Los Angeles County. If the enrollee is enrolled in an HFP dental plan that is also a Medi–Cal dental managed care plan, they will be enrolled in that plan. If their HFP dental plan is not a Medi–Cal dental managed care plan, they will be able to choose a new dental managed care plan or choose to be enrolled in Denti–Cal.

- HFP Enrollees in Sacramento County Shift to Dental Managed Care. About 27,500 HFP enrollees live in Sacramento County. If an HFP enrollee is enrolled in an HFP dental managed care plan that is also a Medi–Cal dental managed care plan, they will be enrolled in that plan. If their HFP dental plan is not a Medi–Cal dental managed care plan, they shall select a Medi–Cal dental managed care plan. If they do not choose a Medi–Cal dental managed care plan, they shall be assigned one which contracts with their current provider.

The Administration Is Required to Submit Several Reports to the Legislature. Under Chapter 28, several reports are required to be submitted to the Legislature throughout the implementation of the transition. These reports include:

- Strategic Transition Plan. The California HHSA is required to work with MRMIB, DMHC, DHCS, and stakeholders to develop a strategic plan for the transition and submit it to the Legislature by October 1, 2012. The intent of the strategic plan is to serve as an overall guide for the development of a plan for each phase of the transition and to ensure clarity and consistency in approach to enrollee continuity of care. The strategic plan is required to address several key transition issues, including: (1) administrative readiness at the state and local levels, (2) stakeholder engagement, (3) monitoring managed care health plan performance, (4) implementation timelines and key milestones, and (5) the transfer of the HFP Advisory Board to DHCS.

- Implementation Plans Are Required for Each Phase. Implementation plans are required 90 days prior to each phase of the transition. The plans are to be developed to ensure state and county system readiness, an adequate network of providers in each health plan, and continuity of care, with the goal of ensuring that there is no disruption of service and there is continued access to coverage for all transitioning enrollees.

- Network Adequacy Assessment Is Required. An assessment of network adequacy is required to be completed 60 days before the first shift of HFP enrollees to Medi–Cal.

- Monthly Status Reports Due Beginning February 15, 2013. Monthly status reports on the transition must be submitted to the Legislature beginning no later than February 15, 2013. These reports must include information relating to access to care, continuity of care, changes to provider networks, and eligibility performance standards. A final comprehensive report is due within 90 days of the conclusion of the transition.

Certain Performance Measures Must Be Integrated Into Medi–Cal Managed Care. Chapter 28 requires certain health plan performance measures be in place before children can be shifted from HFP to Medi–Cal. For example, Chapter 28 requires the integration of managed care performance measures with the HFP performance standards—which include the child–only Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set.

Stakeholder Involvement and Written Notices to HFP Enrollees. Under Chapter 28, the DHCS is required to provide a process for ongoing stakeholder involvement and consultation and make information on the transition publicly available. The DHCS and MRMIB are required to work collaboratively to develop notices for HFP enrollees shifting to Medi–Cal. These written notices are required to be sent at least 60 days prior to the transition of individuals.

2012–13 HFP Budget Included an Unallocated Reduction. The 2012–13 Budget Act includes a $183 million unallocated General Fund reduction to HFP. A proposed extension of a tax imposed on managed care organizations (MCOs) used to offset General Fund costs would have provided an equivalent amount of money for the support of HFP in 2012–13, but it was not enacted into law. (For more information on the MCO tax, see the “Medi–Cal” section of this report.) The unallocated reduction of $183 million General Fund was revised downwards to $131 million in the Governor’s 2013–14 budget proposal due to changes in caseload and other factors.

2012–13 Shortfall in HFP Budget. On January 7, 2013, the Department of Finance (DOF) sent a letter to the Joint Legislative Budget Committee (JLBC) notifying the JLBC that MRMIB would expend all of its available resources for HFP in January 2013. To address this shortfall, MRMIB requested $15 million from Item 9840 of the 2012–13 Budget Act. (The Legislature appropriated $20 million General Fund in this item to be available to fund unanticipated expenses, subject to certain conditions specified in the 2012–13 Budget Act.) The DOF’s letter stated that MRMIB will seek legislation this year to cover the remainder of its shortfall in HFP as of January and the remainder of the fiscal year—estimated to total about $116 million. The Governor has proposed an MCO tax as part of the 2013–14 budget, and if such a tax were implemented, it could potentially offset the General Fund expense to fund the HFP shortfall in 2012–13. We note that failure to fund HFP would likely violate federal maintenance–of–effort (MOE) requirements, putting at risk billions of dollars in federal funding for CHIP and Medi–Cal.

When the 2012–13 Budget Act was enacted, it assumed General Fund savings of $13.1 million in 2012–13 as a result of the transition, and at that time the administration projected about a $58 million savings in 2013–14 and about $73 million in full–year General Fund savings annually thereafter. The administration has revised its estimates of the savings that will be achieved through implementation of the transition. Under the revised estimates, $129,000 in savings will be achieved in 2012–13, $43 million in 2013–14, and $38 million annually thereafter. These are the net result of several different adjustments, including changes in caseload, per member per month costs, and administrative costs.

We note that the administration’s revised estimate of the 2012–13 General Fund savings from the transition is based on a CHIP caseload of about 871,000 enrollees. However, as we describe in the next section of this analysis, the most recent caseload information suggests actual CHIP caseload will be lower than 871,000—by about 10,000 to 20,000 fewer enrollees. As a consequence, the estimates of the fiscal impacts of the transition will need to be further revised.

We find that the administration has generally complied with the requirements laid out in Chapter 28 as described above. The administration has submitted the required strategic plan, implementation plans, and network adequacy assessment reports. Written notices informing enrollees of the transition have been developed and sent to families. The DHCS has provided a process for ongoing stakeholder involvement and consultation and has made information, such as the required reports, publicly available.

The HFP transition is generally proceeding as planned, but with some delays. The DHCS worked with CMS to develop a framework for monitoring the transition and obtained federal approval of phase one of the transition on December 31, 2012. (Federal written approval is required prior to the implementation of each phase.) However, as we describe below, phase one was delayed for certain HFP enrollees due to concerns about network adequacy and continuity of care.

Prior to implementation of phase one of the transition, DHCS and DMHC completed network adequacy assessments and implementation plans for enrollees transitioning in phase one and phase two. During those assessments, potential interruptions to continuity of care for some transitioning HFP enrollees were identified.

- Particular Health Plan Had Low Provider Overlap Between HFP and Medi–Cal Networks, Raising Network Adequacy Issues. The first transition issue involved a particular health plan in phase one that had a low percentage of provider overlap between the HFP and the Medi–Cal networks and was unable to report how many primary care physicians would continue to see HFP enrollees after they shifted to Medi–Cal. To allow for an adequate network assessment, the transition of about 90,700 HFP enrollees enrolled in this plan was delayed. The DMHC and DHCS have indicated that HFP enrollees who are not able to remain with their current primary care provider under this plan may be given the choice to select a new plan or provider, rather than being reassigned automatically to this plan.

- Enrollees of a Particular Health Plan Shifted From Phase One to Phase Two Transition. The second transition issue involved a particular health plan that, while originally considered a “phase one” plan, was later recategorized as a “phase two” plan because it does not have a direct contractual relationship with Medi–Cal (instead, it subcontracts with a plan that contracts with Medi–Cal). Accordingly, about 14,600 HFP enrollees enrolled in this plan will transition to Medi–Cal at a later date than initially assumed.

- Some Enrollees Were Not Assigned Primary Care Physicians. The third transition issue involved HFP enrollees (mainly in rural areas with few doctors) who were not assigned to a primary care provider, although some of these HFP enrollees do have an ongoing relationship with a physician or other provider. If no primary care provider is assigned to an enrollee, claims data will be used to assign that enrollee to a provider that they have previously seen. The inability to identify a primary care provider for roughly 3,000 HFP enrollees enrolled in a particular plan in one county initially raised concerns about the administration’s ability to minimize disruptions to continuity of care. The administration has since determined that the network of Medi–Cal providers is adequate to receive transitioning HFP enrollees. The administration has determined that these enrollees can be transitioned on March 1, 2013, the second subphase of phase one.

Following the network adequacy assessments that we described above, the children who had been scheduled to transition in the first phase were further subdivided into three groups to reflect missing data from some plans and the concern that some HFP enrollees in phase one may not be able to remain with their primary care provider. Accordingly, the transition schedule was adjusted and the first two phases of the transition are now occurring as follows (CHIP caseload numbers have been updated since the 2012–13 Budget Act was enacted).

- Phase one, which includes approximately 402,000 children, has now been further broken up into three subphases, as follows:

- The first subphase began January 1, 2013. About 197,000 children in eight counties have transitioned to Medi–Cal.

- The second subphase will begin March 1, 2013. About 95,000 children in 15 counties will transition to Medi–Cal.

- The third subphase will begin April 1, 2013. About 110,000 children currently enrolled in a certain health plan in seven counties will transition to Medi–Cal.

- Phase two will begin on April 1, 2013 and include approximately 261,100 children that reside in 15 counties.

- There are no changes planned to phases three and four at this point. (Network adequacy assessments and implementation plans have not yet been completed for these later phases.)

Some Children Who Enrolled in HFP in November Will Transition in Later Phases. Some HFP enrollees who enrolled in HFP in November and December of 2012, and who would otherwise have been transitioned in phase one, enrolled too late to receive timely notices advising them of the transition. Staff at DHCS state that they do “look backs” to determine when sufficient time will have elapsed between notification and the transition to ensure that state and federal requirements regarding notification are met.

In June 2012, at the time the 2012–13 Budget Act was enacted, HFP had about 873,000 enrollees. As shown in Figure 4, the total number of enrollees has decreased steadily between May and December of 2012. By December 2012 (prior to the transition), HFP had 852,600 enrollees. It is not clear why caseload has declined. Monthly new enrollment in HFP since May 2012 has generally been below the monthly new enrollment seen in 2011.

Figure 4

Healthy Families Program Caseload Has Decreased Steadily in Recent Months

|

Total Number of

Enrollees in 2012

|

|

Change From

Prior Month

|

|

Month

|

Caseloada

|

Amount

|

Percent

|

|

May

|

874,890

|

|

966

|

0.1%

|

|

June

|

872,968

|

|

–1,922

|

–0.2

|

|

Julyb

|

868,709

|

|

–4,259

|

–0.5

|

|

August

|

863,033

|

|

–5,676

|

–0.7

|

|

September

|

859,909

|

|

–3,124

|

–0.4

|

|

Octoberb

|

858,500

|

|

–1,410

|

–0.2

|

|

November

|

857,090

|

|

–1,410

|

–0.2

|

|

December

|

852,592

|

|

–4,498

|

–0.5

|

Given the unanticipated decline in the CHIP caseload—which dropped from 874,900 in May 2012 to 852,600 in December of 2012—we recommend that DHCS and MRMIB report at budget hearings on the causes for the unanticipated decline in caseload. Additionally, we recommend that DHCS and DOF report at budget hearings on its updated projections of 2012–13 and 2013–14 General Fund savings and full–year General Fund savings beginning in 2014–15 from the transition, including a discussion of what is driving differences between these updated projections and what was assumed when the 2012–13 Budget Act was enacted.

As part of his 2012–13 budget plan, the Governor proposed to eliminate DADP by July 1, 2012 and shift its programs and administrative functions to other departments. The administration provided the following rationale for its proposal: (1) co–locating substance use disorder services with physical health programs administered by DHCS is a step toward integrating services to create a continuum of care and (2) the transfer of the programs to other state departments will better align a program’s mission with that of the department receiving the new program(s). The Legislature rejected the Governor’s proposal to eliminate DADP by July 1, 2012, delaying any potential elimination of DADP until July 1, 2013, in order to allow for additional stakeholder input and the development of a transition plan for shifting DADP programs and functions to other HHSA departments.

In this analysis, we provide a brief overview of DADP and then describe the Governor’s 2013–14 proposal for the elimination of DADP and the transfer of its programs and administrative functions to other departments (hereinafter referred to as the transition). We provide a description of the requirements imposed on the transition process by Chapter 36, Statutes of 2012 (SB 1014, Committee on Budget and Fiscal Review), and find that the administration has generally complied with these requirements. We recommend that DADP, DHCS, and DPH be required to report at budget hearings on various aspects of the transition of DADP programs and functions to other departments in order to ensure continued legislative oversight.

The DADP directs and coordinates the state’s efforts to prevent or minimize the effects of alcohol–related problems, narcotic addiction, drug abuse, and gambling. As the state’s alcohol and drug addiction authority, the department is responsible for ensuring the collaboration of other state departments, local public and private agencies, providers, advocacy groups, and program beneficiaries in maintaining and improving the statewide service delivery system. The DADP operates data systems to collect statewide data on drug treatment and prevention, and performs functions and administers programs in the following areas: (1) substance abuse and prevention services; (2) substance abuse treatment and recovery services; (3) licensing adult alcoholism, drug abuse recovery, and other treatment facilities; (4) drug courts and parolee services; and (5) problem gambling.

The Governor’s revised estimated total spending for DADP in 2012–13 is $322 million ($34 million General Fund). The Governor’s budget entirely eliminates funding for DADP in 2013–14 and shifts its functions, programs, and positions to other departments as follows.

- Various Programs Shift From DADP to DHCS. The budget shifts almost $314 million in all funds ($34 million General Fund) and 225.5 positions from DADP to DHCS to reflect the shift of the following programs and functions: (1) federal grants administration, (2) licensing activities, (3) Driving Under the Influence Program, (4) narcotic treatment programs, and (5) parolee services programs.

- Office of Problem Gambling Shifts From DADP to DPH. The budget shifts $3.7 million (all funds) and four positions from DADP to DPH to reflect the transfer of the Office of Problem Gambling from DADP to DPH. The DPH also requests $5 million in special funds expenditure authority and two, two–year limited–term positions to continue implementation and data collection of the Problem Gambling Treatment Services Pilot Program.

The budget assumes that the year–over–year net fiscal effect of the shift of DADP’s functions, programs, and positions as proposed by the Governor is neutral. Under the Governor’s proposal, costs resulting from the transition, such as the transfer of information technology (IT) systems and relocation of staff, will be absorbed within the existing resources of DADP, DHCS, and DPH.

Instead of adopting the Governor’s proposal in his 2012–13 budget to eliminate DADP by July 1, 2012, the Legislature enacted Chapter 36 to plan for implementation of the transition by July 1, 2013. However, the ultimate placement of DADP’s programmatic and administrative functions is contingent upon enactment of the 2013–14 Budget Act and implementing legislation. Chapter 36 requires HHSA—in consultation with stakeholders and affected departments—to develop a plan to be submitted as part of the Governor’s 2013–14 budget package. (The plan has been submitted by the administration.) The plan is intended to ensure that the transfer will achieve several goals, such as improving access to alcohol and drug treatment and ensuring appropriate state and county accountability through oversight and outcome measurement strategies.

Under Chapter 36, the transition plan prepared by HHSA shall include the following:

- Rationale. A detailed rationale for the transfer of administrative and programmatic functions from DADP to other departments.

- An Analysis of Transition Costs and Activities. A cost and benefit analysis for each transfer of a program or function from DADP to another department and for the proposal as a whole, showing fiscal and programmatic impacts of the changes.

- Continuity of Service Assessment. A detailed assessment of how the transfer of DADP functions and programs will affect continuity of service for providers, consumers, local government counterparts, and other major stakeholders.

- Coordination Across Departments. If the plan proposes to transfer functions from DADP to more than one department, then the plan should include details on how a smooth transition across departments will be ensured and how ongoing program and policy functions will be coordinated across departments.

- A Stakeholder Outreach Process. A detailed description of the process to include stakeholders in the development of the plan.

Overall, we find that the administration has acted in good faith to comply with the requirements set forth in Chapter 36 regarding stakeholder outreach and the submission of a transition plan. A total of three stakeholder workgroup meetings were convened in September and October of 2012 in order to obtain input from parties that would be affected by the elimination of DADP. In January 2013, HHSA submitted the transition plan to the Legislature as part of the Governor’s 2013–14 budget plan. We have reviewed the plan and find that it broadly meets the requirements set forth in Chapter 36.

In order to ensure continued legislative oversight over the elimination of DADP and the shift of its programs and functions to other HHSA departments, we recommend that DADP, DHCS, and DPH report at budget hearings on how the transition is proceeding. Specifically, the departments should report on how the transition will achieve the following goals set forth in Chapter 36 to:

- Improve access to alcohol and drug treatment services for consumers, including a focus on recovery and rehabilitative services.

- Effectively integrate the implementation and financing of services.

- Ensure appropriate state and county accountability through oversight and outcome measurement strategies.

- Provide focused, high–level leadership within state government for alcohol and drug treatment services.

In California, the federal Medicaid Program is administered by DHCS as the California Medical Assistance Program (Medi–Cal). As a joint federal–state program, federal funds are available to the state for the provision of health care services for low–income pregnant women, families with children, and for SPDs. California receives a 50 percent Federal Medical Assistance Percentage—meaning the federal government pays one–half of most Medi–Cal costs. Medi–Cal is by far the largest state–administered health services program in terms of annual caseload and expenditures.

There are two main Medi–Cal systems administered by DHCS for the delivery of medical services: FFS and managed care. In a FFS system, a health care provider receives an individual payment for each medical service delivered to a beneficiary. Beneficiaries generally may obtain services from any provider who has agreed to accept Medi–Cal payments. In managed care, DHCS contracts with managed care plans, also known as health maintenance organizations, to provide health care coverage for Medi–Cal beneficiaries. Managed care enrollees may obtain services from providers who accept payments from the health plan, also known as a plan’s “provider network.” The health plans are reimbursed on a “capitated” basis with a predetermined amount per person, per month regardless of the number of services an individual receives. Unlike FFS providers, the health plans assume financial risk, in that it may cost them more or less money than the capitated amount paid to them to deliver the necessary care.

The budget proposes $15.3 billion General Fund in 2013–14 for local assistance under the Medi–Cal Program, including the provision of health care services and county administration costs. This is a $354 million net increase, or 2.4 percent, over estimated 2012–13 expenditures. Generally, the level of expenditures and changes in year–over–year spending are driven by various factors, including:

- The total enrollment of beneficiaries in the program and per–person cost of providing health care services, which is affected by both the price and level of utilization for individual services.

- Policy changes that affect the level of spending for health care services, such as changes to the amount of payment to providers and managed care plans.

- Technical changes that result from the timing of receipt or payment of funds.

Later in this write–up, our analysis focuses on the fiscal impact on the Medi–Cal budget of prior and proposed policy changes, many of which are intended to create General Fund savings.

Caseload. The budget projects a monthly average of 5.8 million Medi–Cal beneficiaries will be enrolled in managed care during 2013–14 (67 percent of this total), while a monthly average of 2.9 million (33 percent) will be enrolled in FFS. Together, these projections—totaling 8.7 million beneficiaries—represent a 6 percent increase over the 2012–13 average total monthly caseload of 8.2 million beneficiaries. As mentioned in the “Overview” section of this report, most of the growth in caseload is due to the shift of HFP subscribers to Medi–Cal. (Please see our earlier write–up in the “Crosscutting Issues” section of this report for a detailed update on the HFP transition to Medi–Cal.)

We have reviewed the above baseline caseload projections—absent any changes associated with ACA, also known as federal health care reform—and do not recommend any adjustments at this time. If we receive additional information that causes us to change our assessment, we will provide the Legislature with an updated analysis at the time of the May Revision.

It is important to note that the budget’s caseload projections exclude two major populations expected to significantly increase enrollment in Medi–Cal under the ACA.

- Currently Eligible but Not Enrolled Population. Individuals who (1) are currently eligible but not enrolled in Medi–Cal and (2) take up Medi–Cal coverage due to provisions related to eligibility, enrollment, retention, and other changes under the ACA.

- Newly Eligible Population. Individuals who become newly eligible for Medi–Cal, if the state adopts the option under the ACA to expand coverage to low–income adults who are not currently eligible for Medi–Cal.

There is significant uncertainty about the magnitude of these ACA–related caseload changes. To a large degree, additional enrollment among the currently eligible depends on behavioral responses that are difficult to predict, such as responses to the individual mandate and simplified enrollment processes. In addition, major state policy decisions about how to implement the expansion, such as whether to adopt a state– or county–based expansion, would have very different effects on the state’s Medi–Cal caseload. When the administration provides updated Medi–Cal caseload estimates that incorporate these ACA–related changes, we will provide the Legislature with an updated assessment.

Special Session Will Address Medi–Cal–Related Issues. The Governor recently called for an extraordinary special session of the Legislature on health care to address ACA implementation issues, including conforming to federal eligibility and enrollment rules and other issues that may affect Medi–Cal take–up among individuals who are currently eligible but not enrolled. Later in this write–up, we discuss the budget’s $350 million General Fund placeholder for costs associated with this population.

Governor Proposes to Adopt Optional Expansion. The administration has stated its commitment to opting in to the optional expansion and the budget outlines a state– and county–based approach to expansion, but does not provide an estimate of the fiscal impact on the state for either approach. For a detailed analysis of fiscal and policy issues surrounding the optional expansion, please see our report, The 2013–14 Budget: Examining the State and County Roles in the Medi–Cal Expansion.

The CCI. The budget also proposes changes to the implementation plan for the CCI, a significant policy initiative that cuts across Medi–Cal, IHSS, and other health and human services program areas.

In the remainder of this write–up, we analyze and provide our assessment of (1) risks to savings assumed under prior budget actions, (2) new fiscal and policy proposals in the Medi–Cal budget, (3) fiscal effects associated with ACA implementation, and (4) the administration’s requests for additional resources.

The Medi–Cal budget includes some key assumptions about the ongoing General Fund savings associated with recently enacted budget actions. Below, we describe two assumptions and the level of associated General Fund risk assumed in the Governor’s Medi–Cal budget.

Provider Payment Reductions of Up to 10 Percent. In 2011, budget–related legislation authorized a reduction in certain Medi–Cal provider payments by up to 10 percent. Several months later, a U.S. District Court issued preliminary injunctions preventing DHCS from implementing most of the provider payment reductions. In December 2012, a Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals panel reversed the district court’s decisions and vacated the preliminary injunctions. However, on January 28, 2013, the plaintiffs petitioned the court for a rehearing and the state is currently prohibited from implementing the reductions.

The Medi–Cal budget assumes the injunctions will be lifted in March 2013 and the state can begin to implement the payment reductions for managed care in April 2013 and FFS in June 2013. It also assumes that, beginning September 2013, the state will begin to retroactively recoup a portion of payments made to FFS providers during the period in which the reductions were enjoined. The budget assumes $152 million General Fund savings in 2012–13 and $573 million in 2013–14 from implementing the provider payment reductions.

Analyst’s Assessment. Given the uncertainty regarding the timing and outcomes of legal proceedings, there is some risk that part or all of these savings will not be achieved as assumed in the Governor’s budget. We recommend that DHCS report at budget hearings on the status of the litigation so the Legislature can assess the likelihood of achieving these savings.

Medi–Cal Copayments. The 2011–12 budget authorized mandatory copayments for Medi–Cal beneficiaries on physician visits ($5), dental visits ($5), prescription drugs ($3 or $5), emergency room visits ($50), and hospital inpatient visits ($100 per day). The state was unable to obtain approval from the federal CMS to implement the mandatory copayments at the levels authorized in the 2011–12 budget. The 2012–13 budget assumed $20 million in General Fund savings from a revised proposal to implement lower copayment amounts for certain prescription drugs ($3.10 per filled prescription) and nonemergency use of emergency rooms ($15 per visit) for beneficiaries in managed care.

As part of the 2013–14 budget, the administration has revised its plan to implement copayments for Medi–Cal beneficiaries. The administration now proposes to implement only the $15 copayment for managed care enrollees who utilize the emergency room for nonemergency services. It is no longer proposing to implement copayments for certain prescription drugs. The budget assumes the copayment for nonemergency use of emergency rooms would be implemented in January 2013—saving $8 million General Fund in 2012–13 and $17 million General Fund in 2013–14.

Analyst’s Assessment. At the time of this analysis, we did not have any issues to raise with the administration’s revised copayment proposal for nonemergency care provided in the emergency room. However, we note that the revised copayment proposal has not been approved by the federal government. Since the budget assumed a January 2013 date of implementation, there is already some erosion to the 2012–13 savings assumed in the budget.

In addition, we note that recently proposed federal rules allow copayments of up to $8 for nonemergency use of emergency rooms for enrollees with income up to 150 percent of FPL. Since the $15 copayment is more than the $8 allowed under federal rules, the proposal requires federal approval of a waiver amendment rather than a state plan amendment (SPA). Generally, it is easier for the state to obtain federal approval for a SPA than for a waiver. The Legislature may want to consider directing DHCS to seek federal approval of a SPA for a nonemergency copayment of $8—an amount that would reduce General Fund savings, but that may have a greater likelihood of receiving federal approval—if it does not receive approval for the waiver amendment.

Governor’s Proposal. The administration indicates its desire to improve the quality and efficiency of the Medi–Cal delivery system. The proposed budget assumes savings of $135 million General Fund in 2013–14 by incorporating “efficiency adjustments” into managed care plan rates. At the time of this analysis, the administration had not provided detail about how these efficiency adjustments would be incorporated into managed care rates and how the estimated savings would be achieved. The administration indicates that these savings could be achieved under existing state law such that no statutory changes would be needed.

Analyst’s Assessment. Generally, we agree with the administration’s goal of structuring payments in a way that incentivize lower health care spending and improved health outcomes. However, at this time, the details of how the administration would achieve these outcomes are unclear. We recommend against the Legislature assuming the savings associated with this proposal, unless the administration can provide additional detail about this proposal, including:

- How it plans to incorporate efficiency adjustments into managed care plan rates.

- How the changes will reduce General Fund costs.

- How the changes would potentially impact the quality of care and access to care for Medi–Cal enrollees.

Governor’s Proposal. In recent years, the state’s gross premiums tax on insurers was expanded to include Medi–Cal managed care plans. A portion of the tax revenue from Medi–Cal managed care plans was matched with federal funds and used to increase the rates at which Medi–Cal managed care plans are reimbursed to offset the cost of the tax. The remaining revenue was used to offset state General Fund costs. The tax expired on June 30, 2012. The budget proposes permanently reauthorizing the gross premiums tax on Medi–Cal managed care plans, resulting in General Fund savings of $131 million in 2012–13 and $227 million in 2013–14.

Analyst’s Assessment. At the time this analysis was prepared, we did not have any issues to raise with the administration’s proposal to permanently reauthorize the gross premiums tax on Medi–Cal managed care plans. Generally, we support the concept of leveraging additional federal funding to offset state General Fund costs. If we receive additional information on this proposal that causes us to change our assessment, we will provide the Legislature with an updated analysis.

Background on the Hospital Quality Assurance Fee. The hospital quality assurance fee (hereinafter referred to as the fee) finances the state’s share of some increases to Medi–Cal payments to private hospitals. The state assesses the fee for each inpatient day at each private hospital. The fee varies depending on payer type, with the highest fees assessed on Medi–Cal inpatient days and lower fees assessed on days paid for by other payers, such as private insurance. Private hospitals pay the fee in quarterly installments, and the state uses most of the proceeds to draw down federal matching funds. The combination of fee revenue and federal matching funds allows the state to increase Medi–Cal FFS and managed care payments to private hospitals without incurring additional General Fund costs. Each quarter, the state also retains a portion of the fee revenue and uses it to offset General Fund costs for providing children’s health coverage, thereby achieving General Fund savings.

Governor’s Proposal. Under current law, the fee expires on December 31, 2013. The administration has proposed a three–year extension of the fee through December 31, 2016. The Medi–Cal budget assumes $310 million in savings during the last six months of 2013–14 from using the fee revenue to offset General Fund costs for children’s health care coverage. The administration has indicated that it will pursue extension of the fee through legislation that will be introduced in the policy committee rather than budget–related legislation. At the time of this analysis, draft legislation to implement the fee extension had not been provided by the administration.

Analyst’s Assessment. Because the administration has not introduced legislation to extend the fee at the time of this analysis, we were unable to assess the likelihood of whether the $310 million of General Fund savings assumed in the budget would be achieved under the administration’s proposal. The administration’s assumed savings are based on the amount of General Fund savings under the current fee arrangement during the first six months of 2013–14. These savings were achieved through a series of budget and policy actions.

- Under Chapter 286, Statutes of 2011 (SB 335, Hernandez), the fee’s authorizing statute, the state retained $97 million in quarterly fee revenue to offset General Fund costs for children’s health care coverage.

- Under the 2012–13 Budget Act, the Legislature adopted $117 million in savings from reductions (over six months) to fee–funded managed care payments and direct grants to public hospitals.

The administration has not identified whether the actions described above, or some other actions, would be adopted under the proposed fee extension to achieve $310 million in General Fund savings. We note that the assumed savings implies $155 million in quarterly General Fund savings from the new fee revenue—60 percent greater than the quarterly amount originally authorized under Chapter 286. When evaluating legislation to extend the fee, the Legislature will need to consider various policy issues, including:

- The schedule of fee rates for each inpatient day, by payer type.

- The process for using fee revenue to achieve General Fund savings and its varying impact on different categories of hospitals, such as public and private hospitals.

As the Legislature determines the appropriate amount of General Fund savings to adopt under an extended fee, it should weigh the total expected fee revenue and the net benefit to hospitals over the proposed extension period. For example, enrollment in Medi–Cal is expected to increase under the ACA. If more Medi–Cal beneficiaries receive inpatient care at private hospitals as a result, the amount of fee revenue available for both payments increases and General Fund savings may grow correspondingly.

Generally, we support the concept of leveraging provider fees in lieu of General Fund to increase Medi–Cal payments to providers without additional costs to the state. We recommend the Legislature enact an extension of the hospital quality assurance fee for this purpose. We also advise a limited–term fee extension, since this provides flexibility for the Legislature to restructure the fee in response to future changes that may occur in important areas, such as (1) Medi–Cal inpatient utilization and (2) federal requirements on states’ use of provider fees. However, since the administration has not submitted draft legislation at the time of this analysis, we were unable to comment on the details of administration’s proposal. The fee is a complex financing mechanism whose design has both fiscal and policy implications for the Medi–Cal Program. Therefore, we believe the policy committees are the appropriate venue for the Legislature to deliberate over important policy decisions related to the implementation of the fee—including the projected amount of fee revenue over a three–year extension and the portion of revenue used to fund hospital payment increases—before adopting the savings amount assumed in the Governor’s budget.

Governor’s Proposal. Currently, Medi–Cal managed care enrollees may change plans on a monthly basis. The budget proposes to allow certain Medi–Cal managed care beneficiaries to change health plans only during specified periods of the year. Certain populations would be exempt from this requirement, such as SPDs. New Medi–Cal enrollees would have an initial 90–day period during which they could change plans. Existing enrollees would be allowed to change plans during an annual 60–day “open enrollment” period. The administration estimates General Fund savings of $1 million in 2013–14 from implementing the open enrollment period.

Analyst’s Assessment. At the time this analysis was prepared, we did not have any issues to raise with the administration’s proposal. Open enrollment periods are a common requirement for individuals with private insurance coverage. If we receive additional information on these proposals that causes us to change our assessment, we will provide the Legislature with an updated analysis.

Governor’s Proposal. The Medi–Cal budget includes a $350 million General Fund placeholder for costs associated with increased enrollment of individuals who are currently eligible for Medi–Cal, but not enrolled in the program, until a more refined estimate can be developed. The ACA contains several provisions that will likely increase enrollment among individuals who are currently eligible for Medi–Cal, including simplified eligibility and enrollment procedures, enhanced outreach activities, and the individual mandate to obtain health coverage. The state will be responsible for 50 percent of the costs associated with the increased enrollment of individuals who are currently eligible.

Analyst’s Assessment. The short– and long–term costs from additional enrollment among the currently eligible Medi–Cal population under the ACA are subject to significant uncertainty. Some of the major areas of uncertainty include: (1) the size of the eligible, but not enrolled population, (2) the percent of the eligible population that will enroll (take–up rate), and (3) the cost of providing services to each additional enrollee. Figure 5 shows a range of estimated costs for these additional enrollees under three different scenarios. Under a moderate–cost scenario that we think is most likely, we estimate that the health care costs associated with this population would be $104 million in 2013–14—significantly less than the $350 million included in the Governor’s budget. Using different, but still plausible, assumptions, we estimate state costs could potentially be as low as $30 million or as high as $254 million in 2013–14. Therefore, even under a set of assumptions that would result in relatively high state costs, our near–term cost estimates are almost $100 million lower than the placeholder in the Governor’s budget. However, we estimate annual costs may be over $350 million within a few years—potentially ranging from the low hundreds of millions to nearly a billion dollars annually.

Figure 5

Range of Estimated Annual Medi–Cal Costs for Health Care Services to Currently Eligible but Unenrolled Population Under the ACAa

(In Millions)

|

State Fiscal Year

|

Low–Cost Assumptions

|

|

Moderate–Cost Assumptions

|

|

High–Cost Assumptions

|

|

Total Cost

|

Federal Fundsb

|

State Funds

|

Total Cost

|

Federal Fundsb

|

State Funds

|

Total Cost

|

Federal Fundsb

|

State Funds

|

|

2013–14

|

$65

|

$35

|

$30

|

|

$222

|

$118

|

$104

|

|

$540

|

$286

|

$254

|

|

2014–15

|

180

|

98

|

83

|

|

618

|

328

|

290

|

|

1,517

|

804

|

714

|

|

2015–16

|

222

|

120

|

102

|

|

765

|

407

|

359

|

|

1,897

|

1,005

|

893

|

|

2016–17

|

245

|

145

|

101

|

|

849

|

482

|

367

|

|

2,127

|

1,198

|

929

|

|

2017–18

|

259

|

157

|

103

|

|

901

|

522

|

379

|

|

2,279

|

1,309

|

970

|

|

2018–19

|

274

|

165

|

109

|

|

958

|

554

|

404

|

|

2,447

|

1,404

|

1,043

|

|

2019–20

|

289

|

174

|

115

|

|

1,015

|

587

|

429

|

|

2,620

|

1,501

|

1,119

|

|

2020–21

|

305

|

184

|

122

|

|

1,080

|

623

|

457

|

|

2,814

|

1,610

|

1,204

|

|

2021–22

|

323

|

194

|

129

|

|

1,150

|

663

|

487

|

|

3,027

|

1,731

|

1,297

|

|

2022–23

|

341

|

205

|

136

|

|

1,222

|

703

|

518

|

|

3,248

|

1,855

|

1,393

|

|

Key Assumptions

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Eligible population in 2014

|

2.4 million

|

|

|

|

2.5 million

|

|

|

|

3.1 million

|

|

|

Average take–up ratesc

|

8%

|

|

|

|

20%

|

|

|

|

33%

|

|

|

Annual average cost per new enrollee in 2014

|

$1,169

|

|

|

|

$1,440

|

|

|

|

$1,694

|

|

Fiscal Estimates Are Incomplete. There are several potential costs and savings related to ACA implementation that are not included in the Governor’s budget. As discussed above, the budget does not assume any state savings or costs associated with the optional Medi–Cal expansion that the administration has stated it is committed to adopting. In addition, the budget does not assume savings from reduced enrollment in certain state health programs—such as the Family Planning, Access, Care, and Treatment Program and the Breast and Cervical Cancer Treatment Program—that may result from the additional health coverage options made available under the ACA, or administrative costs or savings associated with changes in the standards and processes used to determine Medi–Cal eligibility. To a large degree, these fiscal effects depend on important policy decisions that remain to be made. The Legislature will need to account for these and other ACA–related fiscal effects in the 2013–14 spending plan.

Key ACA Policy Decisions Remain. In addition to decisions about whether or not to adopt the optional expansion and whether to adopt a state– or county–based approach, the state has several other major ACA–related policy decisions that have yet to be made—many of which have potential fiscal effects in 2013–14. Some of the key decisions facing the Legislature include:

- Selecting the benefits that would be provided to the Medi–Cal expansion population if a state–based approach to the optional expansion were adopted.

- Determining how to implement the new Medi–Cal eligibility standards and enrollment processes as required by the ACA.

- Evaluating whether to modify or eliminate existing state health programs that provide services to persons who would become newly eligible for Medi–Cal or other health coverage in 2014.

- Whether or not to establish a Basic Health Program, a “Bridge Program” between Medi–Cal and the California Health Benefit Exchange (as proposed by the Governor), or some other program, with the intent to make coverage more affordable for populations with incomes too high to qualify for Medi–Cal.

These and other important ACA policy decisions may be informed by additional federal guidance that is expected in the coming months. As the Legislature considers these policy decisions, it will also need to consider any related fiscal effects as it constructs the state’s 2013–14 budget.

Governor’s Proposal. The Governor’s budget requests an increase of 333.5 positions for DHCS and $42.8 million ($4.3 million General Fund) in related state operations funding. The majority of the requested positions are related to the planned elimination of DADP and the related transfer of DADP programs to DHCS (238.5 positions and $28.7 million in state operations). (For more information on the elimination of DADP and the shift of its functions and programs to DHCS and the DPH, see our analysis on DADP in the “Crosscutting Issues” section of this report.) The remaining 95 positions are requested to support a variety of functions and programs administered by DHCS, including Medi–Cal waiver projects, CCI, the California Medicaid Management Information System replacement project, hospital financing, and other department workload activities. Of these 95 positions, the majority (76) are existing limited–term positions that the administration is requesting to extend on a limited–term basis.

Overall Analyst’s Assessment of Staffing Requests. We have reviewed the Governor’s requests for additional staffing for DHCS and, with the exception of one proposal described below, we find the Governor’s requests reasonable. If we receive additional information on the Governor’s proposals that causes us to change our assessment, we will provide the Legislature with an updated analysis.