Heather Gonzalez

December 2, 2025

Disabled Veteran Business

Enterprise Program Review

Summary

As required by Chapter 80 of 2020 (SB 588, Archuleta), this brief reviews California’s Disabled Veteran Business Enterprise (DVBE) program, which is designed to support DVBEs by ensuring they receive a portion of state government purchasing contracts. The law requires state entities to set a goal of awarding at least 3 percent of their annual contract value to DVBEs. State law also establishes the Office of Small Business and Disabled Veteran Business Enterprise Services (OSDS) as the DVBE program administrator, directs it to implement policies to ensure that only eligible businesses participate, and requires it to track and investigate cases of program abuse and noncompliance.

DVBE Program Implementing Recent Changes, But Key Challenges Remain. Overall, the state has implemented some recent statutory changes successfully (such as the substitution process described below), but the program is in transition as it is still implementing other changes. One current limitation is inconsistent data and uneven adherence across state entities. For example, while the state as a whole met the 3 percent participation goal in nine of the past ten years, only 57 percent of state entities required to report to OSDS met the target individually in 2023‑24. Continued monitoring and improved reporting would enable a clearer evaluation of the program’s effectiveness and help inform decisions about future modifications.

Brief Provides Key Metrics Required by SB 588. Pursuant to the direction in SB 588, we reviewed the available data on the following program characteristics:

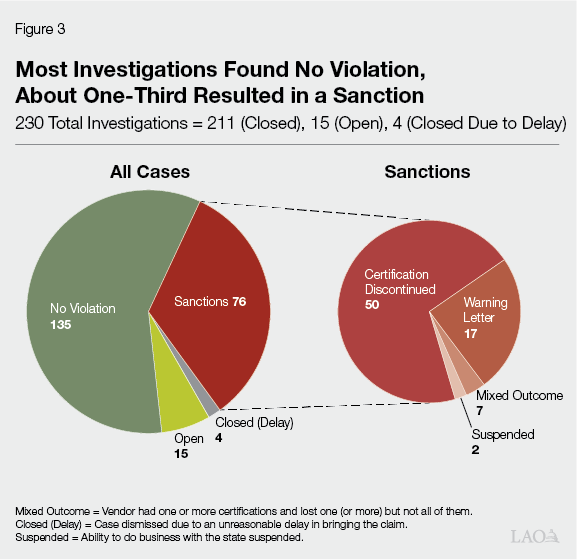

- Noncompliance and Program Abuse. Over roughly four years, OSDS investigated 230 cases of potential noncompliance. Underutilization—the failure of prime contractors (who are the entities directly awarded contracts) to provide the level of work committed to DVBE subcontractors—was the most commonly investigated violation. After OSDS investigations, roughly two‑thirds of all closed cases resulted in no violation; about one‑third resulted in sanctions, ranging from warnings to the loss of ability to do business with the state.

- Withholding Payments. Senate Bill 588 requires state entities to withhold up to $10,000 from final payment owed if prime contractors fail to certify certain DVBE participation information. Lack of data prevents us from determining the effects of the policy on prime contractors’ compliance with DVBE program rules. Additionally, stakeholders have raised concerns about the $10,000 withholding amount—arguing it may be too small to influence behavior on large contracts and too large for small businesses to manage—though current evidence is inconclusive.

- Substitutions. The state DVBE substitution process allows prime contractors to replace listed DVBE subcontractors with other DVBEs in certain cases. At least 50 prime contractors received approval for substitutions between 2021 and 2025.

- Notifications. A generally accepted best practice is for program administrators to notify a DVBE subcontractor when they are named on a prime contractor’s bid. For state entities using the Financial Information System for California (FI$Cal), such notifications occur automatically, with 3,070 issued in 2024. It is unclear how consistently state entities not using FI$CAL are issuing notifications.

Issues for Legislative Consideration. Going forward, we identify a few issues for the Legislature to consider:

- To the extent the Legislature wants more definitive conclusions on the program’s outcomes, it could request an audit focused on state entities’ compliance with DVBE policies, the effects of recent changes, and measures to improve data quality and consistency.

- If the Legislature wants to address stakeholder concerns about the $10,000 withholding, it could consider creating a sliding scale (with costlier penalties for larger contracts) or excluding small businesses from the policy. Alternatively, it could wait until more data has been collected showing the need for change.

- If the Legislature is concerned about state entities not achieving the 3 percent goal, it could request OSDS to provide information on which entities meet the goal (and why) and which struggle (and why) to inform potential program changes.

Introduction

Established in 1989, California’s Disabled Veteran Business Enterprise (DVBE) program is designed to support service‑disabled, veteran‑owned businesses by ensuring they receive a portion of state government purchasing contracts. However, two California State Auditor reports from 2014 and 2019 identified significant DVBE program deficiencies and recommended a list of reforms. These reforms included changes to data collection and reporting and the transfer of program oversight from the California Department of Veterans Affairs (CalVet) to the Department of General Services (DGS). In the years since the Auditor’s reports were released, state entities implemented the recommended changes to administrative practices while the Legislature made various statutory changes to the DVBE program. These include:

- Chapter 676 of 2019 (AB 230, Brough)—which, among other things, requires prime contractors (the entities directly awarded a contract) to use the DVBE subcontractors named in their original bids unless they receive approval from the state to substitute them. It also requires prime contractors to certify, at contract completion, (1) the percentage of work the prime contractor committed to provide to a DVBE subcontractor, and (2) that the DVBE subcontractor has been paid for that work.

- Chapter 80 of 2020 (SB 588, Archuleta)—which, among other things, directs state entities to withhold up to $10,000 from the final payment otherwise due to a prime contractor if that prime contractor does not certify various pieces of DVBE‑related information. This information includes the amount and percentage of work the prime contractor committed to provide initially and the actual amount paid to a DVBE subcontractor (as required by Chapter 676 and other provisions of existing law).

This brief is provided in response to provisions of SB 588 that direct our office to review the DVBE program. Specifically, SB 588 directs our office to provide information on:

- Noncompliance Reporting. Reports of noncompliance with the requirements of the DVBE program.

- Complaint Tracking. Whether DGS is tracking complaints of abuse of the program, and information about those complaints, if available, including the type of abuse, how it was reported or discovered, dates that specific actions were taken on the case, and preventive measures taken by awarding departments.

- Notifications to DVBE Subcontractors. Whether the awarding departments notified DVBE subcontractors when they were named on an awarded contract.

- Approval of DVBE Subcontractor Substitutions. Whether prime contractors received approval by DGS to replace DVBE subcontractors identified by the prime contractors in their bids or offers.

- Withheld Payments. Whether withholding payments has deterred prime contractors from failing to provide accurate certifications.

Our review of the DVBE program relies on data and information provided by DGS program staff, as well as discussions with various stakeholders and CalVet.

Background

California’s Program Structured to Support Service‑Disabled Veteran Businesses

California Has a Significant Number of Disabled Veterans. Over 1.2 million veterans—about 8 percent of the total U.S. veteran population—call California home. Approximately 380,000 California veterans (about 30 percent) have a service‑connected disability, which is defined as a disability that was caused (or made worse) by military service. Of California’s service‑disabled veterans, nearly half (approximately 174,000) have disability ratings exceeding 70 percent. (Higher disability ratings imply greater impacts on overall health and ability to function.)

The State’s DVBE Program Encourages State Entities to Purchase Goods and Services from Disabled‑Veteran Owned Businesses. The purpose of California’s DVBE program, as outlined in state law, is to “address the special needs of disabled veterans seeking rehabilitation and training through entrepreneurship and to recognize the sacrifices of Californians disabled during military service.” The law requires state entities to set a goal of awarding at least 3 percent of their annual contract value to service‑disabled veteran‑owned businesses. This is commonly known as the “3 percent participation goal.” State law also establishes the Office of Small Business and Disabled Veteran Business Enterprise Services (OSDS)—located within DGS—as the administrator of the DVBE program. Other states and the federal government also have programs designed to support DVBE firms. (For more information on these other programs, see the nearby box.)

Disabled Veteran Business Enterprise Contracting

Goals in Selected Other States and the Federal Government

- Illinois—State agencies and universities are encouraged to spend at least 3 percent of their procurement budgets with certified veteran‑owned businesses.

- Michigan—Michigan’s goal is to award at least 5 percent of total state expenditures for goods, services, and construction to qualified service‑disabled veteran‑owned companies.

- New York—The Service‑Disabled Veteran‑Owned Business program participation goal in New York is set at 6 percent.

- Washington—In Washington, state agencies have been charged with meeting a 5 percent veteran‑owned business participation goal overall. However, individual agencies receive a customized target goal that may be more or less than this amount.

- Federal—Between 1999 and 2024, the federal governments maintained an enterprise‑wide goal of awarding not less than 3 percent of the total value of all contracts (prime and subcontract) to certified Service‑Disabled Veteran‑Owned Small Businesses. In 2024, federal policymakers increased this percentage by two points, to 5 percent.

What Does OSDS Do in Support of the DVBE Program? Among other things, OSDS certifies DVBE vendor eligibility; manages and responds to complaints of program noncompliance, fraud, and abuse; provides education, training, and support to DVBEs; and provides guidance to state entities to help them meet their 3 percent participation goals. Since the passage of Chapter 730 of 2022 (AB 2019, Brough), OSDS must establish and take remedial actions when state entities have failed to meet their DVBE participation goals in three of five prior years. (Such remedial actions include removing purchasing authority; however, the list of proposed remedial actions was still under review in October 2025.) Additionally, OSDS prepares and publishes various reports on DVBEs and the state program.

How Does a Business Qualify as a DVBE? For the purposes of the state DVBE program, a “disabled veteran” is defined as a veteran of the U.S. military, naval, or air service, who has a service‑connected disability rating of at least 10 percent, and resides in California. Vendors wishing to qualify as a DVBE apply for state certification. Among other criteria, vendors must demonstrate that their businesses are:

- Majority owned (by at least 51 percent) by one or more disabled veterans; or, in a business whose stock is publicly held, at least 51 percent or more of the stockholders are disabled veterans;

- Managed and controlled by one or more disabled veterans; and,

- Located in the United States (and not a branch or subsidiary of a non‑U.S. business).

- Certified DVBEs must reapply for certification every two years.

What Are the Business Advantages of DVBE Certification? DVBE‑certified vendors receive the following financial and competitive advantages in the state procurement process:

- DVBE Option—The DVBE option is a procurement process that, under specified conditions, allows state entities to contract directly with a certified DVBE for goods and services without going through the typical competitive bidding process. To qualify, the contract award must be either: (1) between $5,000 and $250,000; or (2) for public works contracts, an amount as otherwise provided by the Director of Finance. State purchasers must receive price quotes from at least two certified DVBEs. This is intended to simplify the contracting process both for the state entity and the DVBE.

- DVBE Incentive—The DVBE incentive, on the other hand, provides a competitive advantage to bidders who include a certified DVBE subcontractor in their proposals. The incentive applies to most competitive state solicitations. Advantages to the bidder include bid price adjustments (in the case of lowest price contracts) or point increases (in the case of contracts awarded based on scoring criteria). For example, in contracts awarded based on the lowest price, a bidder’s “price” can be adjusted downward for the purpose of awarding the contract. (The actual price charged to the state if the contract is awarded does not change.) Similarly, in contracts awarded based on highest score, a bidder can receive additional points based on DVBE participation.

- Reciprocity Partners—These cities, counties, special districts, and other public entities agree to accept and recognize the state DVBE certification as a valid credential, which confers benefits similar to those above on DVBEs in their procurement processes. Key reciprocity partners include the City and County of Los Angeles and many California utility companies.

How Many DVBEs Are There in California? As of June 2025, California had 2,118 certified DVBEs. By comparison, the average number of certified DVBEs between the 2017‑18 and 2023‑24 fiscal years was 1,774—ranging from a low of 1,623 in 2018‑19 to a peak of 2,070 in 2020‑21. The number of certified DVBEs with active state contracts is somewhat unclear. This is because only state entities that use the Financial Information System for California (FI$Cal) are able to easily identify the number of unique DVBEs they contract with. In 2023‑24, 369 unique DVBEs were doing business as a prime contractor, and 220 were doing business as subcontractors, with state entities that use FI$Cal. However, the actual number of unique DVBEs with active state contracts may be higher because some departments that make significant use of DVBEs—such as the California Department of Transportation (CalTrans) and the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR)—do not use FI$Cal.

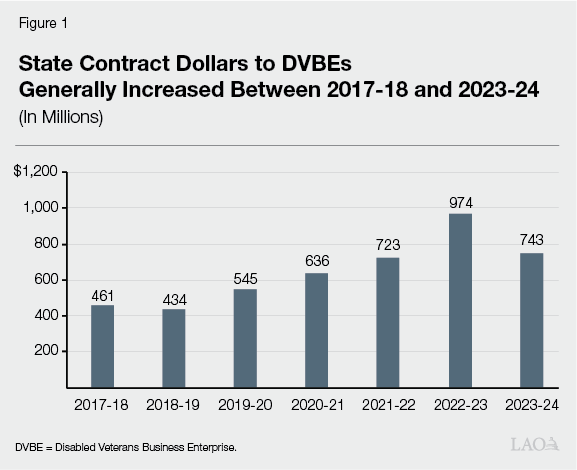

How Much State Funding Goes to DVBEs? The state awarded $743 million across 20,838 contracts to DVBEs in 2023‑24—or 4.6 percent of the $16 billion total reported contract dollars in that year. This amount includes $626 million from 150 state entities that must report DVBE participation under state law (such as state government departments and agencies, which OSDS refers to as “mandatory reporters”), and $117 million from 31 state entities that report voluntarily (such as universities, departments headed by constitutional officers and other independent state entities). As shown in Figure 1, reported state contract dollars received by DVBEs generally increased between 2018‑19 and 2022‑23. Notably, reported state contract dollars—both going to DVBEs and overall—reversed this general trend and decreased between 2022‑23 and 2023‑24. OSDS largely attributes this year‑over‑year decrease to a statewide expenditure reduction directive issued by the Department of Finance in December 2023 that was intended to help address the fiscal difficulties facing the state.

Is the State Meeting the 3 Percent Participation Goal? According to information provided by OSDS, in the aggregate across all reported contracts for mandatory reporters, the state met the 3 percent participation goal in nine of ten years between 2013‑14 and 2023‑24. However, although the state as a whole generally met the 3 percent participation goal, state entities are encouraged to achieve the goal individually and many do not. In 2023‑24, for example, 85 of 150 mandatory reporters (57 percent) met the DVBE participation goal while 58 (39 percent) did not. (Seven, or 5 percent, made no reportable awards.)

Ensuring Only Eligible Vendors Participate Has Been a Focus

Ensuring That Only Eligible Vendors Participate Has Been an Historical Challenge With Violations Ranging From Inadvertent to Fraudulent. One historical challenge for programs like the state’s DVBE program, which directs procurement contracts to certain types of vendors, is preventing ineligible vendors from participating. Ineligible participation can range from the inadvertent failure to comply with state law and policy (such as failing to submit correct paperwork), to program abuse (such as substituting a DVBE subcontractor without approval), to outright fraud (such as falsely claiming to be a disabled veteran). These categories are not exclusive and can overlap.

More Serious Instances of Program Abuse Have Typically Occurred in One of Two Ways. There are two primary means by which vendors may engage in program abuse or fraud. The first occurs when the business itself claims to be a DVBE when it is not. In such cases, the vendor represents their business as both owned and operated by one or more service‑disabled veterans when both conditions have not actually been met. The second occurs when prime contractors claim to be doing a stated amount of subcontracting with a DVBE when they are not. This could be done a number of ways, including:

- A prime contractor names a DVBE subcontractor as a project partner in order to win a bid, but that DVBE subcontractor may not know they were included in the application.

- A prime contractor substitutes an original DVBE subcontractor with a different subcontractor after winning the bid (without state approval).

- A DVBE subcontractor serves as a pass‑through entity to create the appearance of participation but the DVBE does not (in actuality) provide goods and services or perform the work as stipulated. (In other words, the DVBE must actually perform work and cannot simply lend its certification to another business to help win a bid.) This is called a “commercially useful function” or “CUF” violation.

- A prime contractor commits a certain portion of the work to a DVBE subcontractor as part of a bid, but then does not fully meet that commitment. This is known as “underutilization.”

Certain DVBE Program Elements and Policies Have Been Designed to Address Noncompliance and Program Abuse. Such elements and policies include:

- Certification Compliance Review is a process by which program staff look carefully at a vendor’s file to ensure all supporting documentation is present and accurate. This helps identify inadvertent noncompliance and helps catch vendors that may be misrepresenting their status.

- Notification Practices are designed to ensure that the state alerts DVBEs when they have been named as part of a bid. This helps the state catch vendors who might be misleading state procurement officials into thinking a DVBE subcontractor is involved in the bid when the DVBE is unaware they have been named.

- Substitution Limitations seek to prevent prime contractors from replacing a DVBE subcontractor named in a bid with a different vendor after winning the contract.

- Withholding Payment thwarts underutilization and CUF violations by allowing state contract managers to withhold a portion of a prime contractor’s final payment until that contractor certifies under penalty of perjury that the named DVBE subcontractor did the work and was paid as per the provisions in the bid.

Reports of Program Abuse and Noncompliance

Senate Bill 588 directs our office to review noncompliance reporting and complaint tracking. Below, we provide data on the number of cases of potential noncompliance and program abuse, the most common type of alleged abuse, how OSDS responds to these cases, and whether state entities take additional measures to prevent it. As described more fully below, OSDS has investigated over 200 cases of potential noncompliance and program abuse. The most commonly reported type of alleged program abuse was underutilization. Most cases resulted in a finding of no violation, but about one third resulted in a penalty or sanction of some kind.

OSDS Has Investigated 230 Cases of Potential Noncompliance and Program Abuse. Cases of potential noncompliance and program abuse may be identified through certification compliance reviews, complaints, or referrals. Certification compliance reviews generally start with OSDS program staff, who randomly audit DVBE certifications each month and recertify the eligibility of all DVBE firms every two years. Referrals and complaints of alleged DVBE program abuse can come from the public, state entities (including awarding departments), or OSDS program staff. Most commonly, reports of alleged DVBE program abuse come through state entity referrals. Prior to referring an allegation to OSDS, the awarding entity must investigate the alleged violation and prepare written findings. These findings are then submitted to OSDS. OSDS reviews the findings and determines an appropriate response, which could include, among other possibilities, a warning letter to the prime contractor, or referral to the Attorney General (for the most serious allegations). Of the 230 investigations initiated between January 2021 and April 2025, 163 were certification compliance reviews designed to ensure vendor certification files were current, complete, and in compliance; and 67 involved cases of alleged program abuse.

Underutilization Is the Most Common Type of Alleged Program Abuse Referred to OSDS. OSDS recognizes five categories of alleged program abuse violations: underutilization, illegal substitution, cases where both underutilization and illegal substitution occur, CUF, and certification fraud. As shown in Figure 2, of the 67 investigations into reported program abuse that were initiated between January 2021 and April 2025, the majority (34) were for underutilization.

Figure 2

Underutilization Was the Most Common Type of Alleged Violation

January 2021 to April 2025

|

Alleged Violation |

Definition |

Number of Cases Reported |

|

Underutilization |

Occurs when a prime contractor does not use a Disabled Veteran Business Enterprise (DVBE) subcontractor to the extent listed in the initial bid without a justified reason, such as a change in the scope of work. |

34 |

|

Illegal Substitution |

Occurs when a listed DVBE subcontractor is replaced by another DVBE subcontractor without state approval. |

8 |

|

Underutilization and Illegal Substitution |

Combination of these categories. |

11 |

|

Commercially Useful Function |

Occurs when a prime contractor lists a DVBE on the contract to give the appearance of participation, but the DVBE does not (in actuality) provide goods and services or perform the work as stipulated. |

7 |

|

Certification Fraud |

Occurs when a DVBE willingly obtains or maintains a certification despite knowing they do not meet certification requirements. |

7 |

OSDS Responded in Various Ways to Program Noncompliance and Abuse with Severe Penalties Being Rare. As shown in Figure 3, nearly two‑thirds (64 percent) of the closed certification compliance reviews and program abuse investigations resulted in a finding of “no violation.” About a third (33 percent) resulted in a sanction of some kind—that is, the vendor’s certification was discontinued, they received a warning letter, or (in the most egregious cases) a vendor’s executives were suspended from doing business with the state. A total of 3 percent of closed cases resulted in a mixed outcome—which means the firm lost one certification but kept others. As of December 2024, two DVBE firms were included on OSDS’ publicly available list of suspended firms.

Unclear If State Entities Take Additional Preventative Measures in Response to Case Data. Senate Bill 588 requires our office to review whether OSDS is tracking preventative measures taken by state entities in response to cases of program abuse and noncompliance, if available. Noncompliance and program abuse case data provided by OSDS does not link specific preventative measures taken by state awarding entities on a case‑by‑case basis with specific instances of confirmed program abuse. However, the primary means by which state entities prevent DVBE program abuse is through their overall compliance with statewide DVBE contracting policies and best practices, such as the withholding payments, substitution, and notification practices. Further, OSDS has various general mechanisms to capture feedback on state entity performance (such as surveys and reporting) and to improve state entity compliance (such as training in best practices and improvement plans). Therefore, while program abuse case data do not link changes in department policy or contracting rules on a case‑by‑case basis in response to specific instances of program abuse or noncompliance, these activities are occurring on a statewide level. (Below we provide more information about the implementation of some of these statewide preventative measures.)

Policies for Ensuring Eligible Vendors Participate

Senate Bill 588 directs our office to report on withheld payments, substitutions, and notifications. Overall, we found that a lack of consistently reliable data made it difficult to determine the programmatic effects of the withheld payments policy. We also found that the state has a process for substituting DVBE subcontractors; and—at least for state entities that use FI$Cal—a system to automatically notify DVBEs when they are included in a bid. The following sections describe these findings more fully.

Withholding Payments

Data Quantity and Quality Problems Prevent Us From Drawing Clear Conclusions About Policy Effects. In response to our request for information, OSDS provided data on deductions made from final payments owed to state contractors who had failed to certify the participation of their DVBE subcontractors at project completion in accordance with state law. This data serves as the basis for our analysis (as follows in this section) of the effects of the withholding payments policy. However, as we reviewed the data, we found several errors. We worked with OSDS on a case‑by‑case basis to correct these errors, but it is not clear how pervasive these problems are or if this data is reliable. Although we present the data in this section in an effort to be responsive to our statutory reporting requirements, we encourage readers to be mindful of the potential limitations of this information. In addition, OSDS reports that it took a few years to fully stand‑up the withholding policy and ensure that awarding entities were correctly withholding payments as required. As a result, only one year of data that is roughly comprehensive—encompassing the 2023‑24 fiscal year—was available for our review.

State Law Directs State Entities to Withhold Up to $10,000 from the Final Payment Due to Prime Contractors Working with DVBE Subcontractors. As previously noted, Senate Bill 588 directs state entities to withhold up to $10,000 from the final payment otherwise due to a prime contractor if that prime contractor fails to certify, under penalty of perjury, the identities of the DVBE subcontractors who participated in the performance of a state contract, the amount of work those subcontractors were supposed to do (and did), and payments made for that work. This certification is due upon completion of the contract, no later than final invoice. If the certification is not received when due, state entities must withhold up to $10,000 of the final payment. The withhold is temporary at this stage and the prime contractor can still receive these funds if they submit their certifications (called “curing”) within 30 days after notice. The withhold becomes permanent—and the prime contractor forfeits the withheld amount—if they fail to cure.

With Limited Data Available, About Half of Withholds Are Cured. In 2023‑24, state entities reported a total of 98 contracts with initial withholds, 11 of which became permanent. Of the remaining 87—that is, those withholds that had not (or not yet) become permanent—45 were cases where the prime contractor had met their commitment to their DVBE subcontractor, but there was a delay in the state’s receipt of this information. Based on the data provided, it appears these cases were cured (or should have been). The outcome in the remaining 42 withholds was indeterminate for a variety of reasons, including a lack of data, change in the scope of work, or the state entity was still waiting for certification. A total of 13 contracts—including 5 where the withhold had become permanent and 8 where the outcome was still indeterminate—were referred to compliance.

Unclear if Withholding Policy Has Deterred Prime Contractors From Failing to Provide Accurate Certifications. As noted above, the 2023‑24 withheld payments dataset contains many instances of prime contractors who failed to provide certification at contract completion as required. In response to this failure, state agencies withheld up to $10,000 of the final payment due to those contractors. About half of prime contractors appear to have cured, but we could not establish a causal link between the withheld payment and decision to cure based on the data provided. For example, prime contractors may have submitted certifications in direct response to the withheld payment—which suggests that the withheld payment deterred them from failing to certify. Or they may have just been slow to report or failed to understand reporting instructions. With respect to the accuracy of the certifications submitted by prime contractors, our findings are also indeterminate. Although we found instances of inaccurate reporting in the data, we could not determine if the inaccuracy stemmed from the prime contractor, the awarding state entity, or both.

Fixed $10,000 Withholding Limit May Have Limited Effect for Large Contracts… Senate Bill 588 established a $10,000 limit on state withholding authority, regardless of the size of the contract. For high dollar value contracts—often reaching $1 million or more—this amount of withholding could provide limited financial incentive to complete the certification process. For example, in such cases, it might be more cost‑effective for prime contractors to simply forego the $10,000 rather than utilize and pay for the full value of a DVBE subcontractor’s work. While such behavior seems plausible in theory, our review of the 2023‑24 data found no clear pattern of permanently withheld payments being disproportionately associated with high dollar value contracts.

…But May Be Challenging for Small Contracts. The $10,000 withhold could be a potential obstacle to partnerships between prime contractors and DVBEs on smaller contracts. (Smaller contracts, as used here, are those transactions worth less than $10,000.) Data provided by OSDS shows a precipitous reduction in the number of smaller contracts with DVBE subcontractors in the years after the withholding policy was adopted—dropping from 742 such transactions in 2020‑21 to 348 in 2023‑24 (53 percent). OSDS theorizes that this change may be driven by a drop in the number of partnerships between small business prime contractors and DVBEs. (Small businesses may not be able to pay their DVBE subcontractors in full at contract completion without full and final payment from the state, particularly in cases where total contract value is below the $10,000 threshold.) However, the data provided by OSDS were preliminary and do not conclusively demonstrate a uniquely negative effect on small businesses. Instead, the data also show a drop of equal magnitude in the number of smaller contracts involving DVBE subcontractors that are partnered with larger businesses. Unfortunately, OSDS did not provide more comprehensive data that could be used to verify or fully assess these trends, such as annual data going back several years before the policy was implemented. Further—even with a decline in small contracts—the payment withholding policy might not be the main reason for this change. One or more other factors—such as the change in state purchasing as a result of the COVID‑19 pandemic or changing economic conditions affecting businesses that compete for small contracts—might also be at play. As a result, the effect of the payment withhold policy on small firms or small contracts more generally to date is not clear.

Substitutions

At Least 50 Prime Contractors Received Approval for a DVBE Subcontractor Replacement via the State Substitution Process. Under the state DVBE substitution process, a prime contractor may replace the listed DVBE subcontractor with another certified DVBE subcontractor under certain conditions. Specifically, regulations authorize a substitution if the originally named DVBE subcontractor:

- Fails or refuses to execute the contract.

- Goes bankrupt or becomes insolvent.

- Fails or refuses to perform the work.

- Refuses or fails to meet bond requirements.

- Was listed as a result of inadvertent clerical error.

- Is not licensed.

- Has performed work that the awarding entity determines unsatisfactory.

- Is ineligible to work on a public works contract, or

- Has been determined to be irresponsible by the awarding entity.

The substituting DVBE vendor must perform work stated in the original bid and cannot start work until OSDS has issued an approval in writing. In general, the process for making such changes includes notifying the listed DVBE subcontractor, the proposed replacement subcontractor (which must also be a DVBE), and the awarding state entity. The listed, original DVBE can oppose the request to substitute. The request to substitute is reviewed by the awarding entity, and if tentatively approved, sent to OSDS for final review and decision. Substitutions occurred at least 50 times between January 2021 and April 2025.

Notifications

FI$Cal Automatically Sends Notifications to DVBEs When They Are Named on a Contract. Notifying subcontractors when they are named on a bid is a best practice, not a requirement. For state entities that use FI$Cal, DVBE notification occurs when the contract or purchase order is approved. FI$Cal automatically generates and sends letters to the DVBE subcontractors named on awarded contracts. In 2024, the FI$CAL system issued 3,070 such notifications.

Unclear if State Entities That Do Not Use FI$CAL Are Notifying DVBEs as Consistently. State entities that do not use FI$Cal process DVBE notifications manually. As a result, we were not able to determine how many such entities have adopted notification as a practice or how consistently it occurs. We asked two non‑FI$Cal agencies that tend to work consistently with DVBEs—CalTrans and CDCR—for the number of such notices they sent in the past five years. CalTrans reported that they had sent none, but noted that they post awarded construction contract information (including DVBE subcontractors) to their website. CDCR indicated that they notify DVBE subcontractors routinely, but that they could not easily track a total number of such notifications sent. CDCR estimated, based on the number of contracts awarded that included a commitment to a DVBE subcontractor, that they sent 18 notifications in calendar year 2024 and 20 in 2023.

Issues for Legislative Consideration

DVBE Program Changes Implemented Relatively Recently, May Benefit From Additional Assessment in the Future. The Legislature made several changes to the DVBE program in recent years. The program also received additional funding and staff in 2023‑24 to enable it to undertake these additional authorities and responsibilities. As many of these policy changes were still in progress or had only recently reached full implementation at the time this brief was being written, our findings reflect only a limited time under the new structure. Also, we identified several errors in some of the reported data on withheld payments. Previous reports from the State Auditor raised related concerns about state entity reporting. Accordingly, to the extent the Legislature wants more definitive conclusions on the implementation of the withholding payment policy by state entities or its effects on prime contractors who partner with DVBE subcontractors, it may wish to consider requesting a follow‑up audit focused on how well state awarding entities are complying with state DVBE policy overall, the effects of recent policy changes, and measures to improve the quality and consistency of data reported by awarding entities to OSDS (including withheld payments data and number of unique DVBEs with state contracts). The State Auditor is well positioned for this task given its previous experience auditing the program.

Various Options Available to Address Stakeholder Concerns About $10,000 Withheld Payment Limit. Although the preliminary data on the effects of the $10,000 withheld payment policy was inconclusive, stakeholders consistently reported that the $10,000 limit may be too low for large contracts. Similarly, with minimal data provided, there may be some indication that the $10,000 limit might be too high for small contracts. If the Legislature wanted to address these concerns its options could include a sliding scale (with costlier penalties for larger contracts) or excluding state‑certified small businesses from the withheld payments policy all together. However, the data supporting the need for such changes is comparatively weak. Accordingly, the Legislature could wait to make further changes to the withheld payment policy until OSDS has had time to collect a larger and better dataset on withheld payments.

Number of State Entities Not Meeting the 3 Percent Participation Goal is a Concern… Still Unknown if Recent Policy Changes Will Help. As noted above, 39 percent of mandatory reporter state entities did not meet the program’s 3 percent participation goals in 2023‑24. Policy changes made in recent years—such as those requiring state entities to make continuous efforts to expand the pool of DVBE bidders and giving OSDS the authority to establish remedial actions against state entities that fail to meet the 3 percent participation goal—may help but it is too early to know. The Legislature could benefit from additional information focused on which state entities have consistently succeeded in reaching their 3 percent goals (and why) and on which state entities consistently struggle (and why). Accordingly, the Legislature could direct OSDS to compile and report on this information to better understand opportunities and challenges in state DVBE contracting, which could, in turn, inform potential modifications to the program.