November 19, 2025

The 2026-27 Budget

Medi‑Cal Fiscal Outlook

Summary

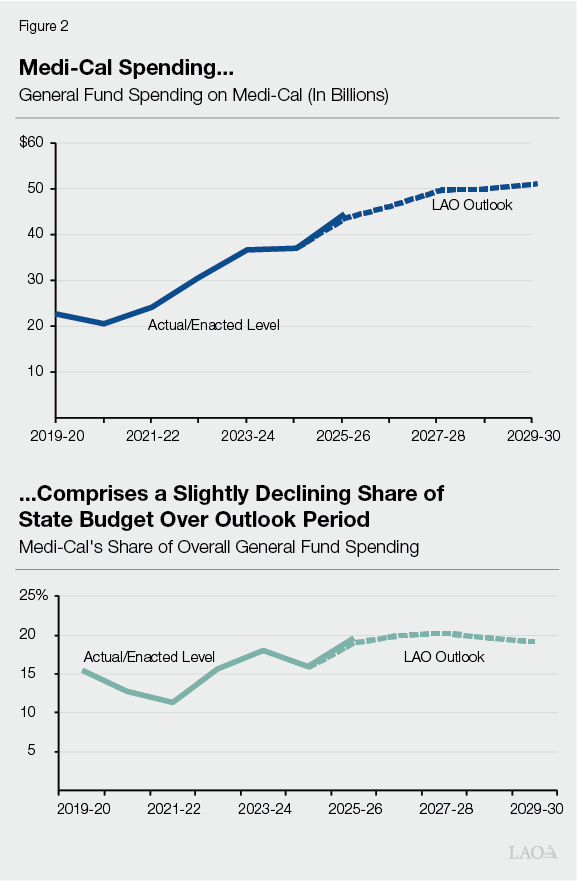

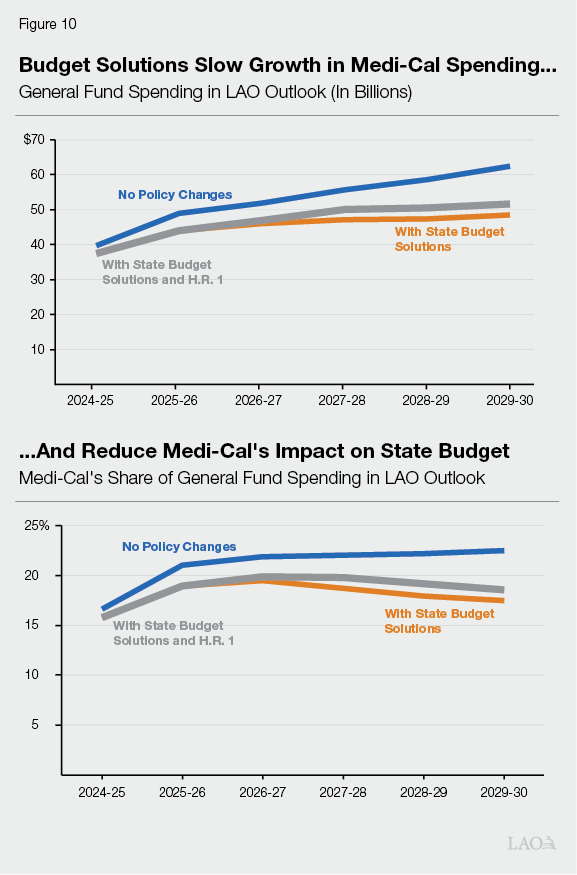

Medi‑Cal Spending Increases in LAO Outlook. The 2025‑26 Budget Act provided Medi‑Cal $44.9 billion General Fund support, an all‑time high for the program. Under our outlook, this level grows to $51.6 billion by the end of the outlook period in 2029‑30 (an increase of $6.7 billion). This increase, however, is slower than the growth rate in the rest of the state budget, with Medi‑Cal’s share of overall General Fund spending at 19 percent by 2029‑30 (slightly lower than the share in the 2025‑26 enacted budget).

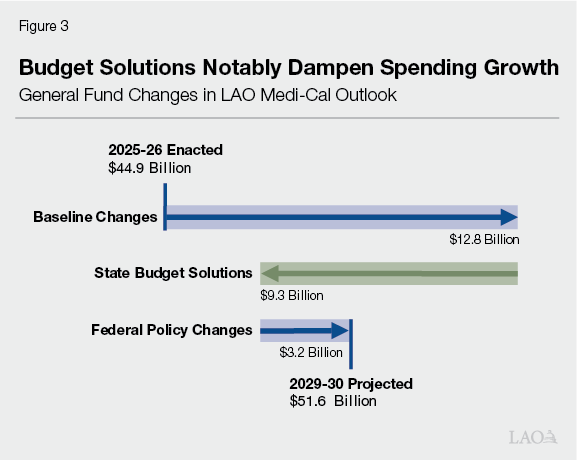

Baseline Spending Drives Increases. The largest driver of growth ($12.8 billion) comes from baseline spending increases (before state and federal policy changes). Increases in enrollee utilization and provider rates cause most of this trend. Most of the remaining growth comes from a rising senior caseload. By contrast, caseload for most other Medi‑Cal populations falls over time, continuing recent trends.

State Budget Solutions Notably Curb Spending Growth. Beyond baseline spending trends, Medi‑Cal is facing a series of upcoming policy changes. The state enacted many of these changes in the 2025‑26 Budget Act in June 2025 as budget solutions intended to slow growth in Medi‑Cal spending. Our outlook estimates the state’s budget solutions mitigate much ($9.3 billion) of the increase in baseline spending through 2029‑30.

Federal Policy Changes, in Turn, Drive Up Spending Further. In July 2025, Congress enacted H.R. 1, which significantly changes federal Medicaid eligibility and financing policies. We estimate the new federal legislation will increase state spending (net $3.2 billion) over the outlook period, partially offsetting the savings from state budget solutions. These new costs come from financing policies that result in less provider tax revenue and federal cost sharing ($5.1 billion). Our outlook also estimates that eligibility changes in H.R. 1 will reduce Medi‑Cal caseload by 1.6 million people by 2029‑30, partially offsetting costs ($1.9 billion).

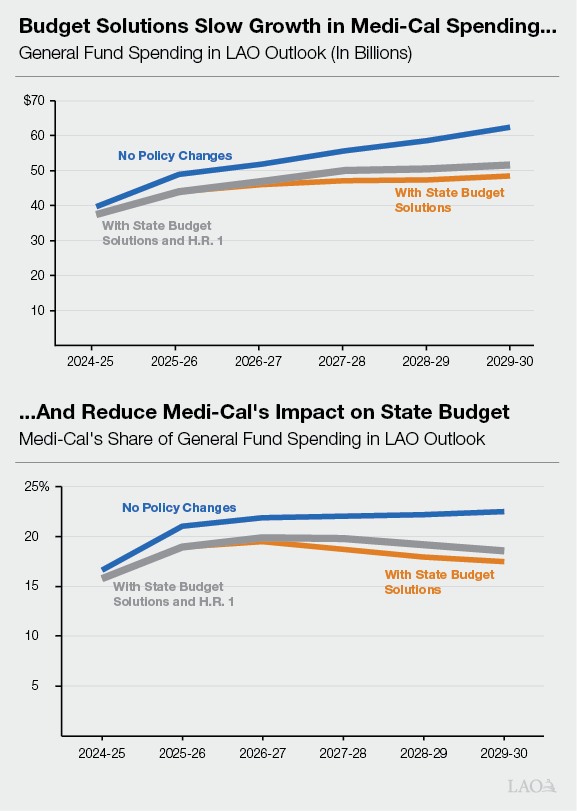

Medi‑Cal Outlook Remains Uncertain. As the figure below shows, our outlook suggests that recently adopted state budget solutions will be critical to slowing Medi‑Cal spending. That said, Medi‑Cal spending probably will rise on net after considering both state and federal policy changes (absent any other future actions by the Legislature or Congress). The timing and size of this net increase, however, is uncertain. General Fund spending in the out‑years could be several billion dollars higher or lower than what we project in our outlook. With so many moving pieces, and with the state’s overall fiscal situation still heading in the wrong direction, the Legislature may need to continue considering its Medi‑Cal priorities in the coming years.

Introduction

Brief Is Companion to Two LAO Reports. This brief summarizes our annual November outlook for General Fund spending on Medi‑Cal, California’s Medicaid program. We recommend reading this brief in conjunction with two other recent LAO reports. The first—The 2026‑27 Budget: California’s Fiscal Outlook—summarizes our overall outlook for the state’s General Fund. The second report—Considering Medi‑Cal in the Midst of a Changing Fiscal and Policy Landscape—provides more information on many of the federal policy changes that drive this year’s Medi‑Cal outlook.

Brief Consists of Three Sections. First, we provide background on the Medi‑Cal program, recently adopted state budget solutions, and recently enacted federal Medicaid policy changes. Next, we summarize the key drivers of our outlook. We then conclude with risks and uncertainties to our outlook estimates.

Background

Medi‑Cal Is a Key Part of State Budget. Medi‑Cal is a sizable federal‑state program, covering health care for nearly 15 million low‑income people. On a total fund basis, Medi‑Cal is the largest program in the state budget, with its nearly $200 billion budget comprising 40 percent of spending across all sources (including federal funds). More than half of this amount comes from federal funds. General Fund spending on Medi‑Cal is $44.9 billion in 2025‑26, reflecting an all‑time high for the program and around 20 percent of overall General Fund spending. Medi‑Cal’s share of General Fund spending historically hovered at about 15 percent, but ticked upward recently due to rising costs in the program.

Last Year’s Budget Adopted Many Policy Changes in Medi‑Cal as Budget Solutions. To slow growth in Medi‑Cal spending and help address a structural deficit in the state budget, the Legislature enacted several policy changes to Medi‑Cal in June 2025. These changes tightened eligibility rules, eliminated certain benefits, and reduced costs in other ways. Many changes are not effective yet. Instead, the budget structured most changes to begin in 2026 and onwards, granting the state and beneficiaries time to adjust to the new policies.

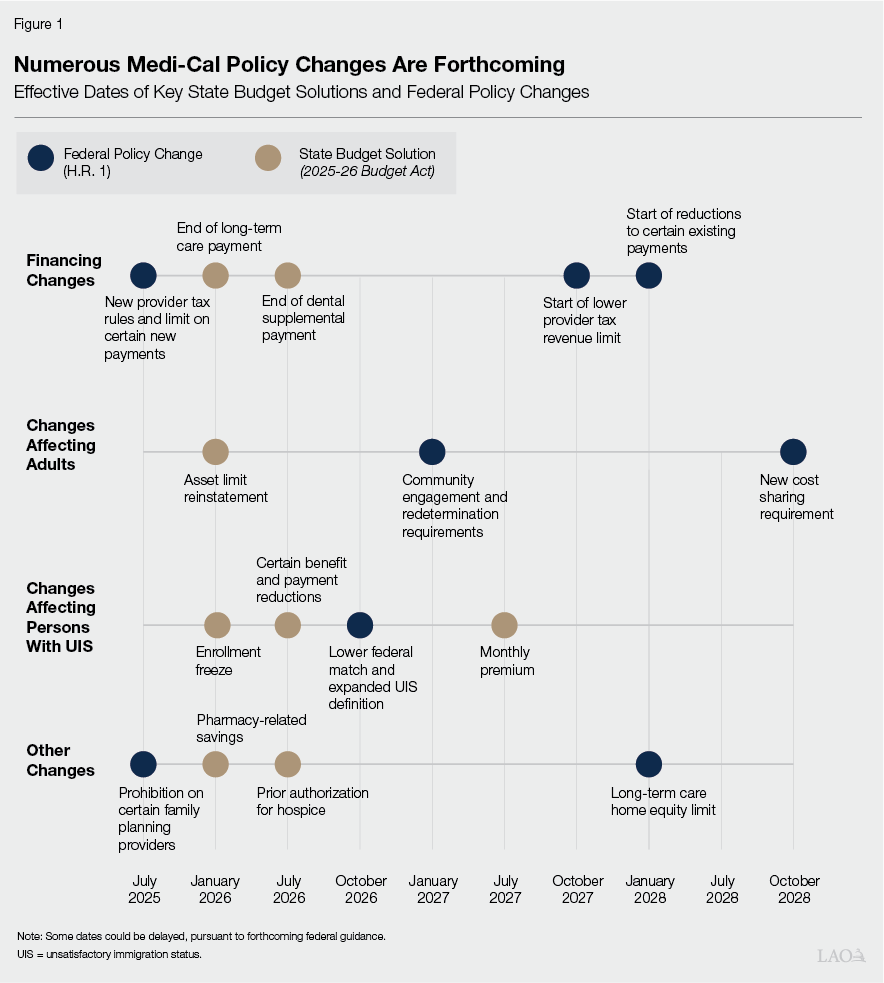

Federal Policy Changes Will Impact Medi‑Cal’s Budget, Reducing Funding to the State. After the state’s enactment of the 2025‑26 Budget Act in June 2025, Congress enacted H.R. 1 in July. Among other areas, H.R. 1 makes several significant changes to federal Medicaid policy with the aim of reducing federal costs. Much like the state budget solutions, many changes are scheduled to become effective in the near future. As a result, as Figure 1 shows, Medi‑Cal faces a steady flow of major state and federal policy changes over the coming years.

LAO Fiscal Outlook

In the coming years, Medi‑Cal’s budget will be driven by baseline changes (underlying trends before the impacts of policy changes), the effects of the state’s budget solutions, and the effects of the federal H.R. 1 legislation. Our outlook for Medi‑Cal reflects all three factors. Below, we summarize the overall trends in our Medi‑Cal outlook and provide more detail on each of the three contributing factors.

Overall Trends

Medi‑Cal Spending Down in Current Year… Under our outlook, General Fund spending on Medi‑Cal spending in 2025‑26 is $43.9 billion. This amount is $1 billion (2.2 percent) lower than the amount adopted in the 2025‑26 Budget Act.

…But Up in Multiyear. After the current year, General Fund spending increases steadily each subsequent year. The amount rises to $47.3 billion in 2026‑27, ultimately reaching $51.6 billion by 2029‑30. The Medi‑Cal growth rate over the outlook period (averaging 3.5 percent annually) is lower than the average annual growth rate for the overall state budget. As a result, as Figure 2 shows, Medi‑Cal comprises 19 percent of overall General Fund spending by the end of our outlook period—slightly lower than the 20 percent share in the 2025‑26 enacted budget.

Baseline Changes, State Budget Solutions, and H.R. 1 Have Differing Effects. From the 2025‑26 enacted level through 2029‑30, General Fund spending increases $6.7 billion on net. As Figure 3 shows, baseline changes—underlying factors before the effects of state budget solutions and federal policy changes—are the primary drivers of growth ($12.8 billion). New costs under H.R.1 also contribute to the growth ($3.2 billion). A sizable portion ($9.3 billion) is offset by the recently adopted state budget solutions.

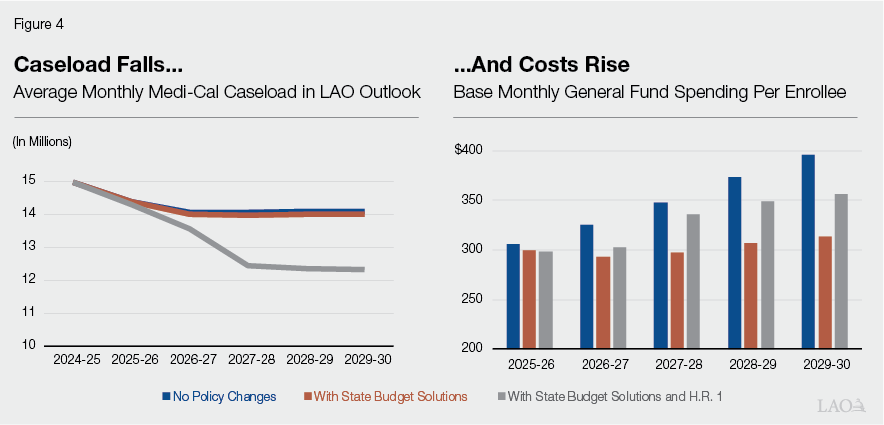

Over Time, Medi‑Cal Will Enroll Fewer People at Higher Cost. Our outlook estimates Medi‑Cal will enroll fewer people over time, with caseload falling from nearly 15 million people in 2024‑25 to nearly 12 million people by 2029‑30. Monthly per‑enrollee General Fund spending, by contrast, rises from $298 in 2025‑26 to $355 in 2029‑30, a $57 (19 percent) increase. This result is consistent with past LAO outlooks and reflects long‑term Medi‑Cal cost trends. Recently enacted state and federal policy changes also influence caseload and cost trends. As Figure 4 shows, we project H.R. 1 policies will particularly reduce caseload, while costs continue to rise.

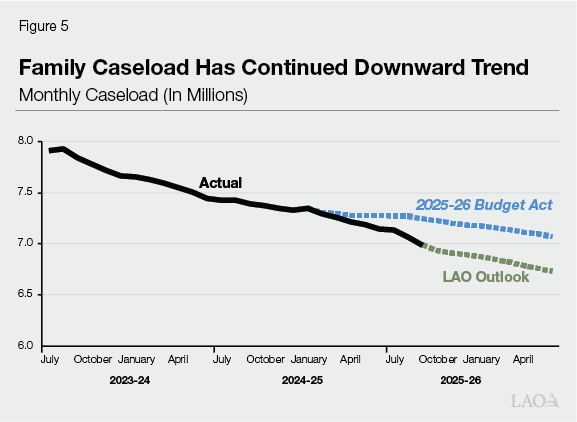

Effects of Baseline Trends

Baseline Spending Falls in 2025‑26 Due to Lower Family Caseload. The net growth in baseline spending over the multiyear ($12.8 billion) is driven by a few factors. Initially, spending falls in 2025‑26 ($760 million), largely from a reduction of nearly 500,000 people (3.3 percent) in Medi‑Cal compared to enacted levels. Families and children account for most of this downward revision (with childless adults comprising most of the remainder). As we noted in May, the administration’s caseload estimates reflected assumptions regarding the unwinding of COVID‑19‑related continuous coverage policies and the resumption of standard redetermination processes. The state assumed that certain flexibilities (authorized through June 2025) would mitigate disenrollments during this time. Eight months of additional data suggest otherwise in the case of families, however. As Figure 5 shows, family caseload continued to fall during this time, despite the availability of flexibilities. We assume this trend continues through the remainder of 2025‑26.

Spending Notably Rises After 2025‑26, Primarily Due to Rates and Utilization… After 2025‑26, baseline spending rises. Most of this increase ($11.1 billion) comes from annual increases in provider rates and beneficiary utilization of services. This reflects annual growth of around 4 percent to 5 percent, primarily based on past trends.

…And Senior Caseload. While our outlook anticipates caseload decreases for most Medi‑Cal populations over the multiyear, the senior caseload increases. This projection generally aligns with anticipated state demographic changes. Seniors are costlier to cover than most other groups (for example, coverage for seniors is around three times the cost of families and children). As a result, the cost from increased senior caseload more than offsets savings from other declining groups, resulting in net General Fund costs over the multiyear ($3.1 billion).

General Fund Backfill Needed Due to Proposition 35 (2024). Our baseline outlook also projects costs to rise due to Proposition 35. The measure made a longstanding provider tax on health plans (known as the Managed Care Organization [MCO] Tax) permanent in state law. It also includes rules for how the state is to spend the associated tax revenue. Beginning in 2027, the measure generally requires the state to allocate a larger share of health plan tax funds toward Medi‑Cal provider rate increases, rather than using revenues to fund existing Medi‑Cal program costs. This requires a General Fund backfill to cover existing program costs previously funded by health plan tax revenues, resulting in an increase in spending over the multiyear ($1.3 billion).

Handful of Other Adjustments Results in Net Reduction. Our baseline outlook includes other smaller adjustments that, on net, slightly offset some of the spending increases over the multiyear ($1.9 billion). These adjustments include ramped down limited‑term spending and increases in the state’s private hospital fee that offset General Fund spending, among other factors.

Effects of State Budget Solutions

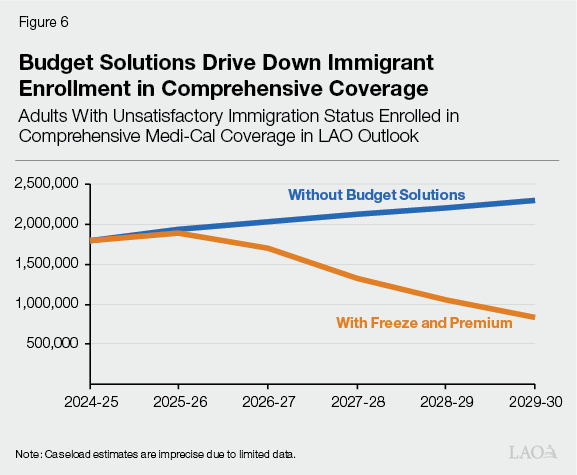

Most Savings Come From Solutions Based on Immigration Status… The net multiyear savings from state budget solutions ($9.3 billion) reflect the combined effect of ongoing and one‑time actions. Of the ongoing solutions, the largest savings ($10.6 billion) come from eligibility policy changes related to adults with unsatisfactory immigration status (UIS). (The UIS population primarily consists of undocumented immigrants, as well as certain documented immigrants.) Coverage for this group tends to be more expensive to the state, as federal cost sharing is only available for limited coverage (emergency and pregnancy‑related services). Accordingly, the state focused many solutions to address this population’s General Fund costs. Most notably, the state will freeze eligibility for comprehensive coverage (for undocumented adults only) and charge monthly premiums on those who remain in comprehensive coverage (for all adults with UIS, ages 19‑59 years old). As Figure 6 shows, we estimate that these policies reduce UIS adult participation in comprehensive coverage, with 1.5 million (64 percent) fewer people by 2029‑30 relative to the baseline. We assume those who leave comprehensive coverage remain enrolled in Medi‑Cal with limited coverage. Other UIS‑related solutions include a change in clinic payments for services delivered to this population and the end of dental coverage for adults.

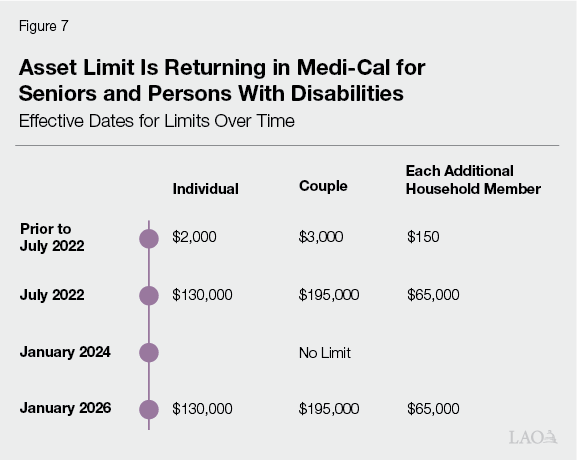

…And Other Ongoing Savings. We estimate that the remaining ongoing budget solution savings ($2.7 billion) over the multiyear will mainly come from two key areas. First, the state enacted several policy changes to reduce pharmacy spending. These include the end of coverage of certain weight loss drugs, plans to negotiate for higher drug rebates, and plans to implement new utilization management strategies. Second, as Figure 7 shows, the state will reinstate a limit on assets for seniors and persons with disabilities. We estimate this reinstatement will result in about 90,000 fewer seniors (4 percent) in Medi‑Cal by 2029‑30 relative to the baseline. Our estimates are informed by previous analyses on the effect of the asset limit elimination.

Savings Are Partially Offset by End of Limited‑Term Solutions. The ongoing multiyear savings are partially offset by the end of limited‑term solutions ($4 billion). Most of this effect comes from a substantial one‑time cash loan to Medi‑Cal that helps offset costs in 2025‑26. With no further loan planned under current law in 2026‑27, the General Fund will need to cover costs moving forward (the current state spending plan envisions gradually paying off this loan over more than a decade). Our outlook also reflects the phase‑down of a two‑year plan to use additional Proposition 35 funds to offset General Fund spending.

Ongoing Solutions Dampen Growth in Per‑Enrollee Costs. In our outlook, the state budget solutions mostly save money by reducing per‑enrollee costs. This is because, other than the asset limit reinstatement, the solutions generally are utilization management strategies, benefit reductions, and provider rate reductions—all ways to curtail spending without directly affecting caseload. (This includes the UIS‑related solutions, as those who leave comprehensive coverage remain enrolled in Medi‑Cal, but with substantially scaled back benefits.) The decrease in monthly General Fund per‑enrollee costs relative to the baseline is substantial, resulting in an $83 reduction (21 percent) by 2029‑30. While this amount might appear small in isolation, it yields significant savings when applied over 12 months to millions of enrollees. We estimate that every $1 reduction in the monthly per‑enrollee cost represents between $150 million and $180 million in General Fund savings, depending on the year.

Effects of Federal Policy Changes

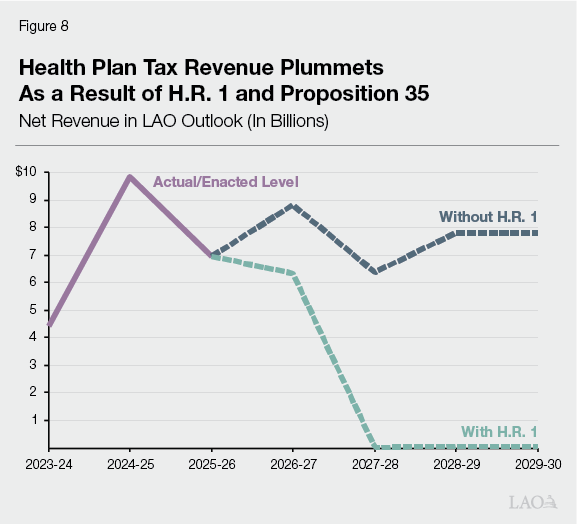

General Fund Backfill Needed Due to Lower Health Plan Tax… Four key factors drive the net increase in spending from H.R. 1 policies ($5 billion). The largest factor ($3.3 billion over the multiyear) is a sizable reduction to the state tax on health plans. As the nearby box explains, this reduction is due to an interaction between H.R. 1’s new rules and a limit required by Proposition 35. For the purposes of our outlook, we assume this change takes effect in January 2027, when the state must renew its federal waiver authority for the tax. As Figure 8 shows, annual net revenue from the tax plummets to around tens of millions of dollars in our outlook. The sizable reduction means that very little tax revenue will be available to help cover existing Medi‑Cal costs, requiring a substantial General Fund backfill to maintain existing spending levels (excluding provider rate increases supported by the existing tax).

Why Does the Health Plan Tax Decline Under H.R. 1?

Existing Health Plan Tax Disproportionately Taxes Medi‑Cal Enrollment. The existing tax on health plans (also known as the Managed Care Organization Tax) charges rates on every monthly Medi‑Cal and commercial enrollee. The current rate on Medi‑Cal enrollment ($274 per month in 2025) is more than 100 times larger than the rate on commercial enrollment ($2 per month in 2025). This rate structure is intended to draw down substantial federal funds while imposing a small cost on the taxpayers themselves. This is because the cost of the Medi‑Cal tax effectively falls on the federal government, whereas the cost of the commercial tax effectively falls on health plans and their consumers.

Federal Law Now Further Limits Disproportionality. Under H.R. 1, states are prohibited from charging higher tax rates on Medicaid services than on non‑Medicaid services. This means that, moving forward, the state’s health plan tax will no longer be able to charge such a disproportionate tax. H.R. 1 states that the new prohibition is effective July 2025, though states can qualify for an up to three‑year transition period at the discretion of the federal Department of Health and Human Services.

Proposition 35 (2024) Limits Tax Rates, Necessitating a Proportionate Tax to Be Smaller. In concept, the state could adjust to H.R. 1’s new rule by decreasing the Medi‑Cal rate, increasing the commercial rate, or a combination of the two actions. Proposition 35, however, limits the state’s ability to increase the commercial rate. This is because the measure limits the commercial tax rate at about its existing level. That is, to make the health plan tax more proportionate under Proposition 35, the state will need to notably reduced the Medi‑Cal tax rate. (As we note in our report on the changing landscape for Medi‑Cal, the Legislature could consider amending Proposition 35 to potentially allow for a large, proportionate tax, thereby mitigating some of the General Fund cost pressure.)

…And Private Hospital Fee. The second key factor is a reduction to another sizable state provider tax—a fee on private hospitals (known as the Hospital Quality Assurance Fee). Similar to the health plan tax, we assume H.R. 1’s relevant policies also begin to affect this fee in January 2027. The ways that federal policy changes will affect the private hospital fee, however, are even more uncertain than for the health plan tax. As the nearby box explains, this is because three different H.R. 1 policies could affect its size in the coming years. Also, there are fewer legal limits on the state to restructure the fee. Keeping these factors in mind, our outlook reflects a decline in the private hospital fee, with annual revenue falling from nearly $10 billion to several billion dollars. Pursuant to state law, most of the decline in revenue will affect supplemental payments to private hospitals, with only a portion (around 25 percent) resulting in less money for existing Medi‑Cal costs. In our outlook, the latter effect results in higher General Fund costs to backfill the lost revenue in Medi‑Cal ($600 million).

What H.R. 1 Policies Will Affect the Private Hospital Fee?

Proportionality Rule. Similar to the tax on health plans, the private hospital fee (also known as the Hospital Quality Assurance Fee) charges higher rates on Medicaid services than on non‑Medicaid services. H.R. 1’s new proportionality rule could put pressure on the state to reduce the size of the fee. This effect is not certain, however. The current fee is not nearly as disproportionate as the health plan tax. Moreover, state law provides more leeway to adjust the fee levels.

Lower Revenue Limit. Federal law currently limits the overall revenue generated by provider taxes to 6 percent of providers’ overall net patient revenue. This limit is intended to prevent states from adopting very high taxes and placing more cost on the federal government. Under H.R. 1, this limit will be gradually reduced beginning in Federal Fiscal Year 2028, reaching 3.5 percent by Federal Fiscal Year 2032. Our understanding is that California’s hospital fee, which is pending federal approval for 2025, is at around 5 percent. This means that the state will need to gradually reduce the hospital fee in the future to comply with the new limit.

Lower Payment Limit. Prior to H.R. 1, federal rules limited managed care payments to hospitals at the average rate paid in the commercial market. H.R. 1 reduces this limit down to the rates paid in the federal Medicare program. For new payment programs, this limit became effective July 2025. For existing payments, H.R. 1 allows states to gradually ramp down to the new limit beginning in January 2028. Much of the hospital fee program supports additional managed care payments to private hospitals, and some of these payments were anticipated to exceed the Medicare limit in the 2025 fee program. Thus, as the state ramps down to the new payment limit, it likely will need to correspondingly reduce the fee.

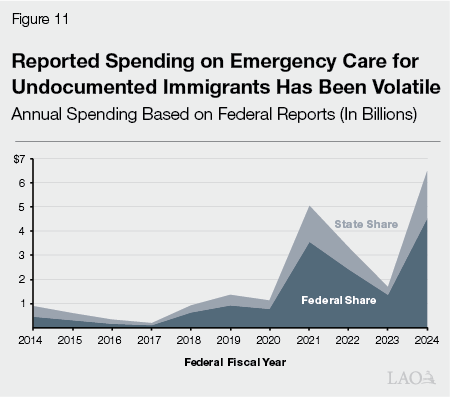

General Fund Backfills Lower Federal Cost Sharing for Immigrant Emergency Services. The third key H.R. 1‑related effect over the multiyear is from reduced federal funding for emergency services provided to undocumented immigrants ($1.2 billion). Under H.R. 1, the federal match for these services will decrease from 90 percent to 50 percent for certain undocumented adults, requiring a backfill from the General Fund to maintain existing services.

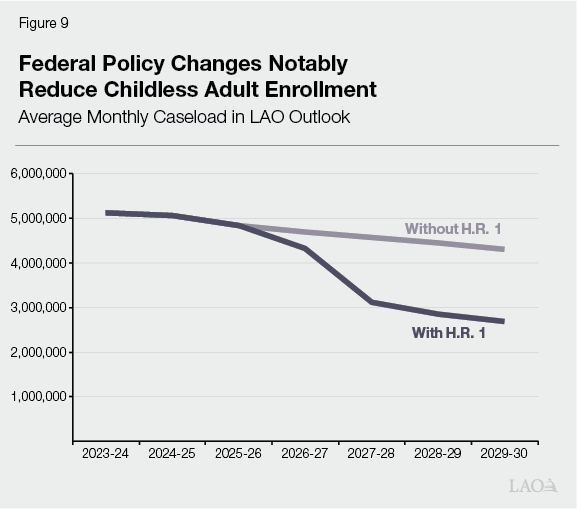

New Eligibility Requirements Notably Reduce Childless Adult Caseload… Programmatically, some of the most substantial changes to Medi‑Cal in H.R. 1 are from two new eligibility policies largely targeted at childless adults. The first is a new community engagement requirement, which conditions Medi‑Cal eligibility on completing 80 hours of work, school, or community service each month. The second is an increase in the frequency of required eligibility determinations from every 12 months to every 6 months. Both changes likely will notably reduce the number of childless adults enrolled in Medi‑Cal. As Figure 9 shows, we estimate these changes will bring the childless adult caseload to 2.7 million people by 2029‑30, a 1.6 million reduction (around 40 percent) from the baseline. This disenrollment represents a 4 percentage‑point reduction in the share of California residents who participate in Medi‑Cal (from 35 percent to 31 percent).

…But Caseload Reductions Yield Relatively Limited State Savings. The savings from this substantial reduction in caseload reflect the fourth key H.R. 1‑related driver in our outlook. We estimate the associated savings to be limited, however, relative to the size of the caseload reduction ($1.9 billion over the multiyear). This reflects the fact that the childless adult population is a relatively inexpensive population for the state, as the federal match is much higher for childless adults (90 percent) relative to most other groups (50 percent in most cases). As such, most of the savings from these disenrollments will accrue to the federal government, rather than the state.

Risks and Uncertainties

Budget Solutions Likely Will Slow—but Probably Not Fully Offset—Spending Growth. Our outlook suggests that the budget solutions adopted by the Legislature this year will help slow Medi‑Cal spending growth. As Figure 10 shows, we estimate that baseline Medi‑Cal spending—without the budget solutions in place—would outpace overall General Fund spending, with Medi‑Cal’s share of state spending rising to 23 percent in 2029‑30, 4 percentage points higher than with the solutions in effect. That said, baseline cost increases, coupled with new costs associated with H.R. 1, probably will exceed these savings from state budget solutions.

Timing and Size of Effects Is Uncertain. Though increased net spending is probable, the size and timing of the increase are highly uncertain. Due to this uncertainty, General Fund spending in the out‑years could be several billion dollars higher or lower than what we project in our outlook.

Two Key Questions Drive Uncertainty. In last November’s Medi‑Cal outlook, we noted a number of issues that caused heightened uncertainty around Medi‑Cal’s budget. While some of these issues remain, new factors are also at play. Specifically, both the timing and size of effects from state budget solutions and H.R. 1 will help shape Medi‑Cal spending in the coming years. Below, we describe each area of uncertainty.

When Will Federal Policy Changes Take Effect?

Timing of Some Effects Depends on Forthcoming Federal Guidance. Very few policy changes under H.R. 1 are currently in effect. Most will begin in the coming years, pursuant to starting dates specified by the legislation. In some cases, however, the legislation allows the federal Department of Health and Human Services to grant states more time for implementation. Whether or not California qualifies for this additional time will depend on federal guidance, much of which is still emerging.

Timing of Provider Tax Changes Are Unclear. From a fiscal perspective, the most significant uncertainty is around the timing of new rules for the health plan tax and private hospital fee. We assume that the state has until January 2027 (when it must renew federal approval of the health plan tax) to make the required adjustments. However, H.R. 1 allows for other potential starting times, ranging from as early as July 2025 to as late as 2028. This timing will affect when the state incurs higher General Fund costs. (Shortly before the release of our outlook, federal administrators issued preliminary guidance suggesting the state would have until July 2026 to adjust the health plan tax and July 2028 for all other provider taxes.)

State Could Have More Time to Implement New Federal Eligibility Requirements. The H.R. 1 legislation also allows a transition period of up to two years for states to implement the new community engagement requirement. California would have to demonstrate a good faith effort toward complying with the new requirement to qualify for such a period. Were this flexibility granted, California could have until January 2029, rather than January 2027 (as assumed in our outlook), to fully implement the requirement. Were California to qualify, the two‑year extension could shift the associated savings from disenrollments over a longer period of time.

How Large of an Effect Will State and Federal Policy Changes Have?

Savings Are Particularly Sensitive to Effects of UIS‑Related Solutions. Of the state budget solutions, the most notable uncertainties concern the immigrant‑related solutions. This is because relatively small changes to our assumptions yield billions of dollars in higher or lower savings, particularly over the multiyear. As the box nearby explains, there are many potential reasons that the effects of budget solutions could be different than assumed in our outlook.

What Are the Key Unknowns Around Immigrant‑Related Budget Solutions?

Immigrant Caseloads and Costs. Until recently, the Department of Health Care Services provided little data on caseloads and costs for people in Medi‑Cal with unsatisfactory immigration status (UIS). In recent years, the department began reporting monthly caseloads of undocumented people with comprehensive coverage in Medi‑Cal. The cost of services to this population, however, is difficult to track with existing data sources. Moreover, data generally are not readily available to estimate monthly caseloads and costs of other UIS populations. Without better data at hand, projecting costs for adults with UIS is inherently imprecise.

Short‑ and Long‑Term Effect of Freeze. The freeze on comprehensive coverage for undocumented adults, slated to begin in January 2026, also has uncertain effects. In the short run, the policy could encourage more adults with UIS to enroll in comprehensive coverage before enrollment closes. This effect is uncertain, however, as take‑up of comprehensive coverage may have already been quite high before the state enacted this solution. In the long run, the freeze’s effect will depend on the number of remaining enrollees that exit from comprehensive coverage over time.

Effect of Premiums. Previous research on the disenrollment effects of premium increases in Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program informs our assessment of California’s impending policy change. That said, we are not aware of research that has examined the impacts of premium changes specifically on the undocumented population. This population could be particularly sensitive to higher costs, yielding larger exits than suggested by available research. On the other hand, the freeze could incentivize some undocumented adults to pay the premium to avoid being permanently locked out of comprehensive coverage. The interplay between these two budget solutions is challenging to predict.

Implementation of New Clinic Finance Change. Another large solution, expected to save just over $1 billion General Fund annually, reduces payments to safety‑net clinics for serving adults with UIS. At the time this solution was adopted, however, stakeholders raised key implementation hurdles that could potentially erode savings. For example, this change might require clinics to track their patients’ immigration status—a practice that many clinics generally do not undertake. Any implementation challenges resulting from such hurdles could delay the timing of savings or reduce the long‑term effect altogether.

Administrative Requirements of Reinstated Asset Limit Could Increase Disenrollments. The exact savings from reinstating an asset limit on seniors and persons with disabilities also is uncertain. At a minimum, the new policy will disenroll affected beneficiaries who possess assets in excess of the new limit. The administrative requirements of demonstrating compliance with the new limit also could discourage participation among those who would otherwise still qualify. As such, our outlook attempts to capture a mix of disenrollments from both asset values and administrative requirements. The latter effect is not certain, however. Moreover, it is difficult to disentangle the effects of the asset test elimination from other factors occurring at the same time, such as the unwinding of continuous coverage and approved federal flexibilities. This makes our assessment of its effects—which informs our projection of its reinstatement—somewhat imprecise.

Pharmacy‑Related Savings Depend on Several Factors. As we have noted in previous publications, predicting pharmacy spending is inherently uncertain given the dynamic nature of the prescription drug market. Many of the pharmacy‑related budget solutions are subject to this uncertainty. Some solutions also rely on the state’s ability to negotiate higher rebates, which could be more or less successful than assumed in our outlook.

Community Engagement Requirement Will Be New to Medi‑Cal. Medi‑Cal has not previously required adults to demonstrate employment to remain eligible, making the effect of the new community engagement requirement uncertain. Experience in other states suggests—much like for the asset limit—that the new requirement will disenroll some working adults due to administrative burden. As such, our outlook includes disenrollment effects from lack of employment as well as administrative burden. These effects, however, depend on the way that the state and counties will implement the new requirements, which is unknown today.

Spending on Emergency Care for Immigrants Has Fluctuated Notably. As part of a broader reporting requirement, the state annually reports to the federal government on the cost of covering emergency care for undocumented immigrants. This reporting provides a reasonable basis to estimate the effects of a decreased federal match under H.R. 1. As Figure 11 shows, however, the trend in spending has been quite volatile. Most of this trend is likely due to federally required changes to the state’s reporting processes. These recent changes in reporting resulted in much higher estimates compared to past years. Our outlook is based on the more recent, higher estimates of emergency care spending. While this higher level likely is more indicative of future spending, there is a chance that utilization of emergency services might also be somewhat volatile in the future, particularly given the forthcoming changes affecting eligibility for undocumented adults in full coverage Medi‑Cal. As a result, the cost to the state due to the change in the federal cost‑sharing ratio is subject to some uncertainty.

Flexibilities Could Mitigate Some Effects of Federal Changes. H.R. 1 grants states some flexibility to implement its policy changes. For example, states can choose to exempt additional groups from certain eligibility changes, such as the community engagement requirement. Adopting these exemptions could mitigate some disenrollments and associated savings.

Effects of Federal Policy Changes Yet to Be Fully Understood. The federal H.R. 1 legislation contains dozens of policy changes to Medicaid programs. In our estimation, the four core changes included in our outlook (health plan tax changes, private hospital fee changes, eligibility changes, and federal cost sharing for emergency care) will be the most fiscally significant. However, given the breadth of H.R. 1, it likely will take years before the associated net fiscal effects are fully understood. At this time, we cannot rule out the possibility that other H.R. 1 provisions will have noteworthy fiscal effects. The nearby box describes other key H.R. 1 changes.

What Are Some Other Key Changes in H.R. 1 to Track?

Change in Unsatisfactory Immigration Status (UIS) Definition. Under H.R. 1, more immigrant groups (such as refuges and asylees) will have UIS beginning October 2026. This means that federal cost sharing will only be available for limited coverage (emergency and pregnancy‑related care). With federal cost sharing no longer available for remaining services (such as primary care and mental health), the state will either need to reduce coverage for these groups or backfill the lost federal funds from the General Fund. Data on Medi‑Cal members with UIS are currently too limited to estimate the potential fiscal effects of this policy.

New Home Equity Limit. California asset limit policies historically disregarded someone’s primary residence and vehicle from the calculation. Under H.R. 1, California will now need to include a home equity limit of $1 million for certain members accessing long‑term care beginning January 2028. Our outlook does not incorporate the effects of this new policy. Were it to further drive down caseload relative to our outlook, the policy could yield additional savings.

Family Planning Payment Prohibition. From July 2025 through June 2026, H.R. 1 prohibits Medicaid payments on certain family planning providers that also provide abortion services. The policy likely bars Planned Parenthood from drawing down federal funds. Other providers could be affected too. This policy has already placed some budget pressure on the state to help backfill the lost federal funding. For example, budget‑related legislation in August 2025 (Chapter 105 of 2025 [AB 144, Committee on Budget]) created a new Abortion Access Fund to support abortion providers, with funds coming from certain excess monies in Covered California plan accounts.

Cost Sharing for Childless Adults. H.R. 1 requires states to impose cost sharing, not to exceed $35 per service, on most benefits to childless adults with incomes above the federal poverty level. The new requirement becomes effective October 2028. In concept, cost sharing could limit utilization, resulting in more savings than estimated in our outlook. As the federal government pays for the cost of most services to this population, however, the savings to the state likely would be limited.

Moratorium on Certain New Rules. H.R.1 places a ten‑year enforcement moratorium on two recently finalized federal rules aimed at streamlining Medicaid eligibility practices and policies. This moratorium comprises a substantial portion of the estimated federal savings in Congressional fiscal scoring sheets. These savings occur because not implementing the new rules limits Medicaid caseload growth. How much of these savings accrue to California, however, is uncertain. California could choose to continue streamlining eligibility policies, even absent federal enforcement of the new rules.

Recoupments for Excess Payments. Under current federal law, federal administrators must recoup funds from states when more than 3 percent of Medicaid payments are in error. Federal administrators, however, can waive recoupments if a state makes a good faith effort to reduce its error rate. Beginning October 2029, H.R. 1 prohibits such waivers. This policy could lead to more repayments to the federal government, depending on California’s error rate in the future. This effect is uncertain, however, and would not occur until the end of the outlook period.

Conclusion

Our outlook projects that the spending reductions adopted as part of the 2025‑26 Budget Act will slow the growth in Medi‑Cal spending, which otherwise would have grown far above average rates. The extent of these savings, however, are fairly uncertain, and could be bigger or smaller relative to our outlook. Compounding this uncertainty, the full fiscal and programmatic implications of H.R. 1 are still emerging as the federal government releases its guidance. With so many moving pieces, and the state’s overall fiscal situation still heading in the wrong direction, the Legislature may need to continue considering its Medi‑Cal priorities in the coming years.