Chas Alamo

July 10, 2025

Refocusing the Workers’ Compensation Subsequent Injury Program

- Introduction

- Workers’ Compensation Basics

- Subsequent Injury Benefit Trust Fund

- The SIBTF Expansion

- Consequences of an Expanded SIBTF

- Options to Refocus SIBTF on Its Original Purpose

Summary

Subsequent Injury Benefit Trust Fund (SIBTF) Started as a Narrowly Focused Benefit. The state’s SIBTF pays generous lifetime workers’ compensation benefits to injured workers who also have pre‑existing health issues. The state first enacted SIBTF to offset employers’ workers’ compensation costs for veterans and other workers whose serious pre‑existing disabilities made a new work injury more disabling and therefore more costly to the employer. The program has evolved since then and now rivals the size of the standard workers’ compensation system but with looser standards, broader eligibility, and more generous benefits. Nearly all claimants receive the state’s most generous disability benefit, $1,700 per week for life, a rarity in standard workers’ compensation. Most SIBTF claims cite common health issues as pre‑existing disabilities (rather than severe conditions as originally intended). These include hypertension, sleep apnea, arthritis, diabetes, headaches, acid reflux, asthma, allergies, and sexual dysfunction.

Employer SIBTF Tax Has Increased, but Nevertheless Understates Program Costs. Increased use of SIBTF has led to an increase in employer taxes that are used to fund benefits—from $35 million in 2014‑15 to $850 million in 2024‑25. This increase nevertheless understates employer costs. This is because, at present, the state processes about one‑fifth of incoming claims each year, leading to a backlog of about 25,000 claims for which employer taxes are not yet due. Employers likely face lifetime benefit costs of $2 billion to $3 billion for each annual cohort of claims.

SIBTF Not Aligned With Legislature’s Workers’ Compensation Structure. The broadened SIBTF benefit program is no longer aligned with the Legislature’s intended benefit structure for workers’ compensation. This is because many injured workers with less severe injuries eventually receive the most generous benefit under SIBTF when they otherwise would have received much smaller awards under the standard workers’ compensation benefit system as designed by the Legislature.

Influx of SIBTF Claims to Cause Further Delays. State processing staff have not been able to keep up with the rising number of SIBTF claims in recent years. As a result, claims processing that is already delay‑prone is set to drag on longer: workers submitting SIBTF claims today might expect to wait five to ten years.

Refocusing SIBTF. We suggest the Legislature look to refocus SIBTF to more closely align with its original purpose. To do so, the Legislature would need to reassess several dimensions of the program. Key options include: (1) establishing stricter criteria for pre‑existing conditions, (2) returning the eligibility threshold to only cover moderate and severe work injuries, (3) requiring that pre‑existing conditions were previously documented, (4) requiring claims to be reviewed by an agreed‑upon physician, (5) limiting SIBTF to pre‑existing disabilities that actually worsen the work injury, and (6) revisiting how multiple conditions are added together. We also recommend the Legislature consider fast‑tracking backlogged claims from workers with the most severe pre‑existing conditions.

Introduction

The Subsequent Injury Benefit Trust Fund (SIBTF) was created as a narrow supplement to California’s workers’ compensation system. The state first enacted SIBTF to offset employers’ workers’ compensation costs for veterans and other workers whose serious pre‑existing disabilities made a new work injury more disabling and, therefore, more expensive. The program had the effect of providing additional lifetime benefits to a small number of workers facing steep barriers to employment. Over time, however, SIBTF has grown dramatically in both size and scope. Today, it operates alongside the standard workers’ compensation system but with broader eligibility, less rigorous standards, and more generous benefits.

This growth has created both fiscal and administrative challenges. The program often pays out lifetime benefits at the state’s highest allowable level to workers with relatively common health conditions and less severe work injuries. The SIBTF tax on employers has grown rapidly, but nevertheless understates the true future cost of claims already filed. Current employer tax amounts understate the program’s full cost because taxes are owed on processed claims and the state’s processing capacity has not kept pace with incoming claims, leading to a backlog of more than 25,000 claims.

This report examines how SIBTF has evolved; how it no longer aligns with the Legislature’s intent for disability compensation; and what policy options could restore the program to its earlier, more targeted role.

Workers’ Compensation Basics

Workers’ Compensation System. California’s workers’ compensation system provides medical care and wage replacement to workers who are injured on the job. Workers with permanent injuries also receive a long‑term wage supplement. Employers must purchase insurance coverage (or self‑insure) and their insurance rates reflect their claims costs. Insurance coverage is more expensive for employers with higher workers’ compensation costs (and vice versa). Workers’ compensation insurance premiums are paid as a percentage of the employer’s payroll. After an injured worker files a workers’ compensation claim, the employer’s insurance company approves or denies the claim. If the worker disagrees with the insurer, they may appeal the decision to an administrative law judge with the state’s Workers’ Compensation Appeals Board (WCAB).

WCAB Reviews Workers’ Compensation Appeals. The state WCAB is a seven‑member judicial body that serves as the court of appeal for all workers’ compensation claims. In addition to reviewing appealed cases, the WCAB issues rulings to clarify the state laws about workers’ compensation eligibility and benefit levels.

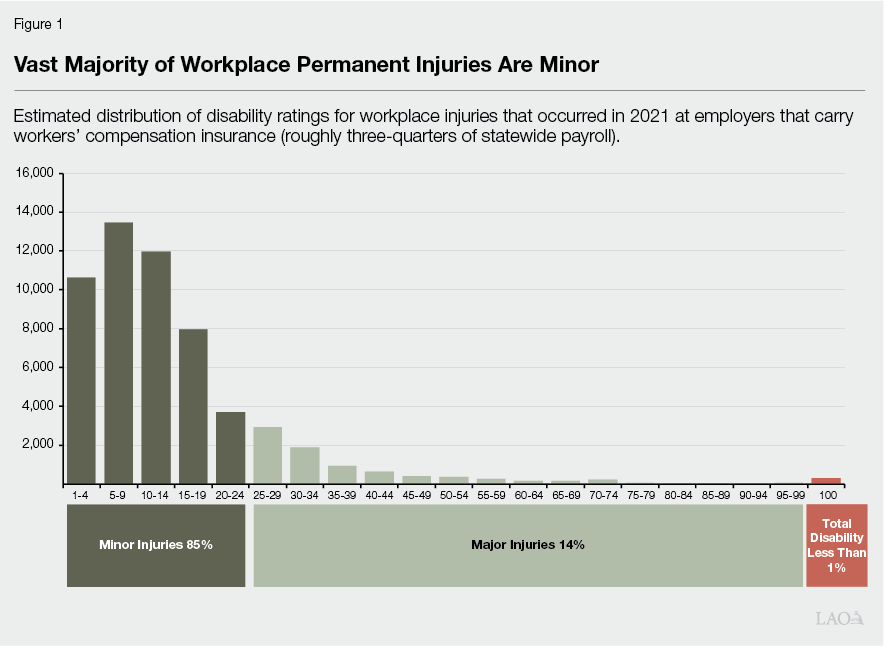

Permanent Disability in Workers’ Compensation. Most workers who are injured on the job receive medical care and temporary pay for lost wages while they get better. Their workers’ compensation case ends when they recover fully and return to work. In some cases, though, workers suffer more substantial injuries that leave them permanently disabled. Workers who suffer a permanent disability receive permanent disability benefits. The amount of permanent disability compensation a worker receives is set by measuring, or “rating,” the injured worker’s impairment. The rating percentage estimates how much the worker’s disability limits the kinds of work they can do. The permanent disability ratings range from 0 percent, which signifies no impairment, to 100 percent, which signifies total disability. As shown in Figure 1, the vast majority of permanent workplace injuries are rated below 25 percent (referred to as “minor injuries” in the workers’ compensation system). Total disability ratings of 100 percent are very rare in the state’s workers’ compensation system.

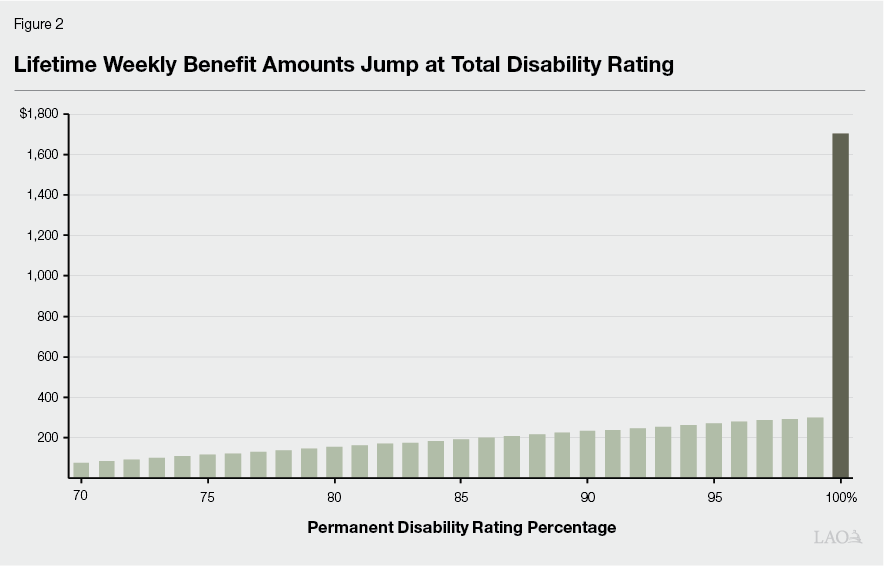

Workers’ Compensation Benefits for Permanent Disability. The amount of workers’ compensation benefits an injured worker receives depends on the worker’s permanent disability rating as shown in Figure 2. Workers with a permanent disability rating between 70 percent and 99 percent are considered partially disabled and therefore still able to continue working in some form. To compensate these workers for their work impairment, they receive a lifetime benefit of up to $290 per week to account for the worker’s lost earnings potential. As shown in the first figure below, benefits for 100 percent total disability claims are much larger—$1,704 per week for life. Figure 3 includes several examples of permanent disability ratings, the related underlying injury, and how state law structures benefits for each injury.

Figure 3

Workers’ Compensation Disabilty Benefit Examples

|

Permanent Disability Rating |

||||

|

Example of a 55 year old worker with $2,000 per week in average earnings who lives until age 81. |

18% |

50% |

71% |

99% |

|

Example Injury |

Hand and shoulder injury resulitng in limited motion and instability. |

Leg injury resulting in lower leg amputation. |

Arm, lower back, and leg injury resulting in back surgery and foot amputation. |

Severe traumatic brain injury resulting in substantial cognitive impairment. |

|

Number of weeks of benefit payments |

18 |

241 |

421 |

600 |

|

Weekly benefit amount |

$290 |

$290 |

$290 |

$290 |

|

Lifetime weekly benefit for serious injuries |

No lifetime benefit. |

No lifetime benefit. |

$85 |

$301 |

|

Total Workers’ Compensation Benefits |

$5,200 |

$70,000 |

$115,000 |

$410,000 |

What Other Financial Support Is Available to Injured Workers? In addition to workers’ compensation insurance and benefit payments, injured workers also access several alternative public resources depending on their work history and circumstances. The most common include the state’s temporary disability insurance program, which provides wage replacement for up to one year when a worker gets hurt, ill, or disabled outside of work. These benefits are paid for by a payroll tax on workers. Another alternative is the federal Social Security program, which provides early retirement benefit payments to workers who can no longer work due to illness or injury. Known as Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI), these benefits are available to workers with total disability conditions that significantly limit their ability to do basic work activities.

Subsequent Injury Benefit Trust Fund

SIBTF Established as a Narrowly Focused Benefits Program. The state created SIBTF shortly after World War II to encourage employers to hire returning veterans with pre‑existing disabilities. At the time, employers were reluctant to hire these workers due to potentially higher workers’ compensation costs. If a worker with a prior injury suffered a new workplace injury, the employer could be liable for costs related to both the old and new injuries. The SIBTF addressed this reluctance by instead covering the costs related to the prior injury, thereby spreading these costs across all employers. This had the effect of ensuring the current employer would not be solely liable for prior injuries.

How Do Workers Qualify for SIBTF Benefits? State law sets forth the requirements to be eligible for SIBTF benefits. They are:

- The worker has one or more pre‑existing health conditions or disabilities.

- The worker has suffered a second (“subsequent”) work injury rated at least at 35 percent disability.

- The worker’s overall disability rating (when combining the pre‑existing conditions and the subsequent injury) is greater than the subsequent injury rating alone.

- The worker’s combined disability rating is at least 70 percent.

Who Pays for SIBTF Claims? SIBTF claims are paid out of the state fund, but the fund itself is supported by a tax that employers pay on their workers’ compensation insurance premiums. (This tax is sometimes referred to as an assessment.) All employers pay the same tax rate, levied as a flat percentage of the employers’ insurance premium total. Insurers collect the tax as part of the premium payments and remit the collections to the state. Employers that self‑insure for workers’ compensation remit a commensurate payment to the state. The statewide SIBTF employer tax totaled $848 million in 2024‑25.

The SIBTF Expansion

In recent years, the SIBTF program has evolved from a narrowly focused benefit to support a small number of severely injured workers into a much larger and broader disability benefits program. Many more workers file claims with SIBTF today than a decade ago. These claims typically pay more generous benefits than standard workers’ compensation and many include compensation for common chronic illnesses, as opposed to severe pre‑existing disabilities. The result is a benefit program that now rivals standard workers’ compensation in size and that may no longer align with the program’s original legislative intent.

Number of SIBTF Claims Has Grown Substantially. Between 2005 and 2015, the state received about 1,000 SIBTF claims annually and was able to process roughly half of those claims each year. The number of injured workers submitting SIBTF claims has increased in recent years. The state now receives around 3,000 SIBTF claims per year, of which it has been able to process 500 to 1,000 claims annually. Submitted claims are held as “case inventory” until state staff can process and initiate benefit payments. The state’s case inventory of unprocessed SIBTF claims now sits at roughly 25,000 claims.

SIBTF Program Much More Generous Than Standard Workers’ Compensation. Total disability ratings of 100 percent are very rare in the standard workers’ compensation system but now account for more than 80 percent of SIBTF claims. To receive a 100 percent rating in the standard workers’ compensation system, an independent physician must deem the injured worker incapable of working in any capacity for the remainder of the worker’s life. This standard does not apply in SIBTF. Figure 4 compares the lifetime benefit award amounts of an SIBTF claim to the workers’ compensation figures listed earlier.

Figure 4

Workers’ Compensation Disabilty Benefit Examples

|

Permanent Disability Rating |

|||||

|

Example of a 55 year old worker with $2,000 per week in average earnings who lives until age 81. |

18% |

50% |

71% |

99% |

100% |

|

Example Injury |

Hand and shoulder injury resulitng in limited motion and instability. |

Leg injury resulting in lower leg amputation. |

Arm, lower back, and leg injury resulting in back surgery and foot amputation. |

Severe traumatic brain injury resulting in substantial cognitive impairment. |

Multiple pre‑existing chronic conditions plus new work‑related injury that need not be severe (via SIBTF) |

|

Number of weeks of benefit payments |

18 |

241 |

421 |

600 |

Lifetime |

|

Weekly benefit amount |

$290 |

$290 |

$290 |

$290 |

— |

|

Lifetime weekly benefit for serious injuries |

No lifetime benefit. |

No lifetime benefit. |

$85 |

$301 |

$1,704 |

|

Total Workers’ Compensation Benefit |

$5,200 |

$70,000 |

$115,000 |

$410,000 |

$2,300,000 |

|

SIBTF = Subsequent Injury Benefit Trust Fund. |

|||||

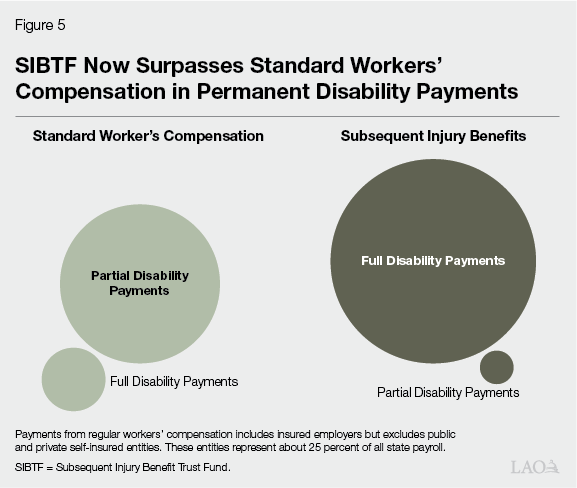

SIBTF Now Surpasses Standard Workers’ Compensation in Permanent Disability Payments. Insured employers pay roughly $1.4 billion in permanent disability payments. Self‑insured employers—private and public—likely add another $500 million to $1 billion. Together, total annual permanent disability payouts under the standard workers’ compensation system likely total about $2 billion. SIBTF, once a relatively small program, now pays more permanent disability payments ($2 billion to $3 billion) than the state’s core workers’ compensation program. Figure 5 compares insured employers’ workers’ compensation permanent disability payments to payments made under the state’s expanding SIBTF program.

Many Claims Built on Common Chronic Conditions. In recent years, the scope of SIBTF claims appears to have expanded beyond providing supplemental benefits to injured workers with severe disabilities. A majority of SIBTF claims now include one or more common, chronic health conditions as pre‑existing disabilities. These include hypertension, sleep apnea, arthritis, diabetes, headaches, acid reflux, asthma, allergies, and sexual dysfunction. SIBTF claims also often include psychiatric conditions such as anxiety, depression, and substance abuse. These conditions are much less common in the broader workers’ compensation system because they are not normally work‑related and work‑limiting. The Department of Industrial Relations (DIR) recently hired the RAND Corporation to study claim‑level data from the state’s SIBTF (California’s Subsequent Injuries Benefits Trust Fund: Recent Trends and Policy Considerations). Below, we highlight a few findings from data collected as part of the RAND study on SIBTF.

- Nearly 70 Percent of SIBTF Claims Allege Common Chronic Conditions. The RAND assessment of recent SIBTF claims found that nearly 70 percent of SIBTF claims alleged at least one condition that had been flagged by the DIR as a common, chronic health condition. The study also noted that 35 percent of claims listed two or more common, chronic conditions. These results may understate the occurrence of common conditions on SIBTF claims because allergies and hay fever were categorized as “Other conditions” and therefore not included in DIR’s grouping of common, chronic conditions.

- Acid Reflux and High Blood Pressure Two Most Common Pre‑Existing Conditions. The most common pre‑existing conditions listed on SIBTF claims are acid reflux and high blood pressure, which each appear on about one‑quarter of SIBTF claims. Other common conditions listed on SIBTF claims include: hearing issues (9 percent of SIBTF claims), blurry vision (8 percent), asthma (8 percent), sleep apnea (8 percent), diabetes (5 percent), and sexual dysfunction (2 percent).

What Led to the Expansion of SIBTF?

The current scope of SIBTF was not the result of deliberative steps by the Legislature to broaden the program. Instead, the expansion has occurred due to a confluence of factors, including court decisions that interpreted SIBTF law broadly, rule changes made by the state appeals board, and legislative reforms to the standard workers’ compensation system that indirectly affected the SIBTF program. Taken together, these factors make it substantially easier to receive benefits under SIBTF than standard workers’ compensation. We summarize these factors below.

Program Established With Limited Guardrails. State laws governing SIBTF do not include several guardrails that are part of the standard workers’ compensation system.

- Pre‑Existing Conditions Do Not Have to Be Work Related. Unlike workers’ compensation, SIBTF claims may include pre‑existing disabilities that were not caused by work and did not occur at work. While this difference is one of the key ways that SIBTF claims are less stringent than workers’ compensation claims, it also is a key feature of the original intent of SIBTF—to encourage employers to hire workers with pre‑existing disabilities, regardless of whether the disability was work related or not.

- Pre‑Existing Conditions Do Not Have to Be Work Limiting. In practice, pre‑existing disabilities may be included in an SIBTF claim even if they did not limit the worker’s ability to do their job. As a result, SIBTF covers asymptomatic pre‑existing conditions or pre‑existing conditions that did not affect the worker’s job.

- Pre‑Existing Conditions Can Be Documented After the Fact. Most pre‑existing disabilities included in SIBTF claims are documented when the SIBTF claims are submitted, in retrospect, based on historical medical records or the claimant’s recollection. Under state law, SIBTF pre‑existing disabilities do not need to be documented when they first arose.

- Pre‑Existing Conditions Not Subject to Independent Medical Review. In workers’ compensation, all parties operate under independent medical review, agreeing to use a neutral, state‑approved physician to assess the worker’s injuries. This requirement does not apply to SIBTF claims. In SIBTF claims, a worker’s physician evaluates and attests to the pre‑existing disability.

2012 Reform Indirectly Lowered SIBTF Eligibility Threshold. One key objective of the 2012 workers’ compensation reform was to increase benefits for injured workers. Rather than increasing the benefit schedule, however, the reform package achieved this objective by automatically increasing all impairment ratings by 40 percent. For example, under the reforms, an injury that previously would be rated as 25 percent disabling is now rated at 35 percent. One unintended consequence of this change was to indirectly lower the eligibility threshold for SIBTF claims—that the subsequent work injury be rated at least 35 percent disabling—to 25 percent in practice. This likely had the effect of allowing more work injuries to meet the initial SIBTF eligibility threshold.

Todd v. SIBTF Interpretation Further Lowered Threshold to Obtain Maximum Benefit. In the standard workers’ compensation system, the state adjusts disability ratings downward when a worker has multiple injuries. This approach accounts for overlap between injuries—for instance, injuries from a fall that caused foot, knee, hip, and shoulder trauma. The ratings are added up but each additional injury rating adds a smaller amount. Under this system, two injuries that are each rated 50 percent would result in a 75 percent disability rating (rather than 100 percent if the two were added together). However, the WCAB recently ruled in Todd v. SIBTF (2020) that multiple injuries in SIBTF claims are to be added together with no downward adjustment for overlap. The Todd decision had the effect of dramatically lowering the medical threshold for workers with SIBTF claims to receive 100 percent permanent disability.

Parties May Act Strategically to Minimize Direct Costs and Facilitate SIBTF Claims. Standard workers’ compensation cases are negotiated between the worker’s attorney and the insurance company’s attorney. Employers and their workers’ compensation insurance companies have a clear incentive to scrutinize workers’ compensation claims. This is because workers’ compensation settlement costs directly raise employers’ insurance premiums. On the other hand, SIBTF benefit payments are spread across all employers so do not lead to direct cost increases for the employer. The existence of the state’s generous SIBTF program may influence these negotiations. Specifically, injured workers may agree to settle for a smaller amount of money if the settlement agreement helps set up the worker’s SIBTF claim—for instance, by steering the injury assessment to highlight pre‑existing disabilities or magnify the portion of the injury attributable to non‑work factors. Both of these adjustments would lead to a more generous SIBTF claim.

Consequences of an Expanded SIBTF

Today, SIBTF operates alongside the standard workers’ compensation system but with looser standards, broader eligibility, and substantially more generous benefits. This dynamic raises some issues that warrant the Legislature’s attention.

Benefits No Longer Aligned With Schedule Established by Legislature

Significant Share of All Major Workplace Injuries File an SIBTF Claim. Relatively few workplace injuries occur each year that are severe enough to be rated at or above 35 percent permanent disability. In 2021, the most recent year for which we have injury data, we estimate that 3,500 workers suffered workplace injuries of this severity. Coincidentally, roughly the same number of workers have filed SIBTF claims annually in recent years. Each SIBTF claim is connected to a severe workplace injury that occurred at some point in the past. This suggests that a significant share of all major workplace injuries in recent years have or eventually will become SIBTF claims. Consistent with the claims trends seen recently, most of these claims will receive 100 percent disability benefits, despite the median major injury receiving a permanent disability rating of 47 percent in the standard workers’ compensation system.

Permanent Injury Compensation No Longer Aligned With Schedule Established by Legislature. In practical terms, a significant share of major injuries becoming SIBTF claims has the effect of altering the workers’ compensation benefits schedule set forth by the Legislature. As described above, the benefits schedule for standard workers’ compensation intends to provide gradually increasing compensation as the severity of a workplace injury increases. Instead, with the expanded role of SIBTF, many major workplace injuries will ultimately become 100 percent disability claims regardless of the severity of the underlying workplace injury.

Escalating Employer Costs

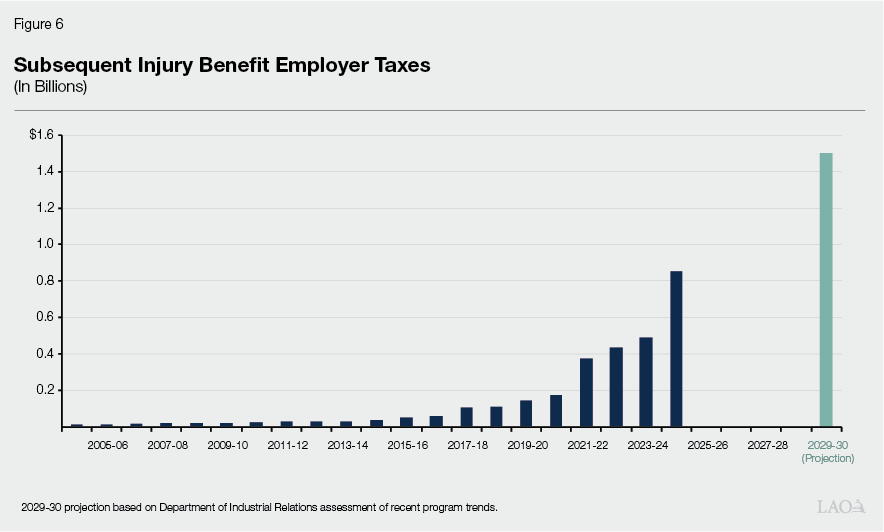

Employer Tax for SIBTF Has Increased Dramatically… SIBTF claim payments and associated medical and legal payments have increased rapidly in recent years, resulting in annual increases in the employer‑paid taxes that replenish the SIBTF. As shown in Figure 6, the 2024‑25 tax is expected to generate $850 million, nearly double the amount necessary to replenish the fund in the prior year.

…But Increase Only Reflects Processed Claims, Understating Full Costs. The recent employer tax increases account for SIBTF claims that the state has processed and begun paying. As such, the current employer tax does not fully capture employers’ financial exposure to SIBTF claims because most claims each year go unprocessed. In recent years, the state has processed between 500 and 800 claims annually, or roughly one‑fifth of all incoming claims. This means current employer tax rates only reflect a small portion of claims submitted, masking the full fiscal effect to come. Should the state progress through the backlog of SIBTF claims at a faster rate, employers’ annual taxes will grow commensurately.

Full Employer Costs Likely $2 Billion to $3 Billion Annually. Looking broadly at incoming claims each year, employers likely face lifetime SIBTF costs totaling $2 billion to $3 billion for each cohort of claims that injured workers submit each year. If the number of claims remains steady at around 3,000 per year and the state processes all incoming claims, the annual employer tax would climb to $2 billion to $3 billion before stabilizing near that level.

Recent Study Estimates $8 Billion in Total SIBTF Liabilities. As part of the recent RAND study, the authors estimated that the present discounted cost of all SIBTF claims totals $7.9 billion. (Discounted value is a measure of the value today of costs that will occur in the future, adjusted for the fact that a dollar now is worth more than a dollar years from now.)

Total SIBTF Liabilities Now Exceed RAND Estimates and Set to Rise Over the Coming Years. Employers’ liability for outstanding SIBTF claims now exceeds the figures published by RAND because those figures only included SIBTF claims submitted through May 2023. The current liabilities figure likely sits closer to $11 billion or $12 billion. Over the next few years, this figure will rise as additional lifetime benefit claims make their way through the SIBTF claims process. Looking ahead, it is entirely possible that outstanding employer SIBTF claims could exceed $20 billion within the next few years. As one point of reference, this is roughly equivalent in size to the state’s outstanding federal Unemployment Insurance loan taken out during the pandemic that employers are set to repay over the coming years.

Influx of SIBTF Claims Based on Chronic Conditions Straining State Capacity for Review

Incoming Claims Have Increased Much Faster Than State’s Processing Capacity. As discussed earlier, the state routinely received 700 to 1,000 cases annually until 2015. During this time, state staff were processing (and beginning benefit payments for) about half of these claims. As such, the case inventory was growing by about 500 cases per year, with about 7,000 pending cases as of 2015. Beginning in 2015, however, the number of incoming claims began to vastly outnumber the state’s processing capacity, with the state processing only one‑fifth of incoming claims each year. The case inventory grew from 7,000 in 2015‑16 to 22,000 in 2023‑24, while more recent trends suggests the case inventory now sits around 25,000 claims.

With Influx of Claims Driving Backlog, Today’s SIBTF Claimants Might Expect to Wait Ten Years. Injured workers must finalize their subsequent injury workers’ compensation case before proceeding with their SIBTF claim for additional benefits. A recent analysis of SIBTF cases found that, on average, an injured worker’s: (1) standard workers’ compensation claim for the subsequent injury took five years to finalize, (2) the worker filed for SIBTF benefits about one year after that, and (3) state staff took an additional five years to process their SIBTF claim. Moreover, one in four SIBTF claims remained in processing for more than eight years. These figures reflect claims that were submitted many years ago, when the case inventory was smaller, and have already been processed. Since then, incoming claims has grown substantially while processing capacity has stayed about the same. As a result, claims submitted in recent years, and to an even greater extent claims submitted in the future, are likely to face longer delays.

Options to Refocus SIBTF on Its Original Purpose

In light of the program’s recent expansion and rising costs, we suggest the Legislature look to refocus SIBTF to more closely align with its original purpose: providing a supplemental workers’ compensation benefit to workers with severe work‑limiting disabilities. The following options represent key policy levers the Legislature could consider to reset the program. No single option would be enough, but in combination they could help refocus SIBTF benefits to injured workers with severe work‑limiting disabilities.

- Establish Stricter Criteria for Pre‑Existing Conditions. The first option for the Legislature to consider is setting a minimum severity threshold for pre‑existing conditions to be eligible for SIBTF. Workers with more serious conditions would meet this higher standard—for instance, a previous workplace back injury that led to surgery, a severe congenital condition, or a partial limb amputation. In most cases, common, chronic conditions such as high blood pressure, early diabetes, or age‑related degenerative changes would not meet this threshold. A higher threshold would have the effect of resetting SIBTF claims to cover serious disabilities that substantially impact employability.

- Reset Initial SIBTF Eligibility Threshold to 35 Percent Disability Rating. The Legislature could consider undoing the indirect effect of the 2012 reforms that increased all impairment ratings by 40 percent. As discussed above, this had the indirect effect of lowering the severity threshold for SIBTF claims from 35 percent permanent disability to 25 percent. Restoring the original eligibility threshold would limit SIBTF claims to workers who have experienced a relatively serious workplace injury.

- Require Prior Documentation of Pre‑Existing Conditions. The Legislature could consider limiting SIBTF cases to pre‑existing conditions that were documented with the employer or a medical practitioner prior to the subsequent injury. Documentation could include a medical examination clarifying work limitations, a workplace accommodation, or a change in work roles due to the disability. This approach would help distinguish between longstanding disabilities and conditions first identified during the process to build an SIBTF claim.

- Align Medical Evaluation Rules With Standard Workers’ Compensation. The Legislature could consider requiring that disability ratings and evaluations in SIBTF cases be determined by an agreed‑upon physician, consistent with long‑standing practice in the standard workers’ compensation program. Historical evidence suggests that permanent disability ratings made by worker‑selected physicians were higher than those made by neutral physicians. This change would improve consistency and limit existing incentives to inflate disability ratings.

- Limit SIBTF Claims to Pre‑Existing Disabilities That Interact With the Work Injury. Under current program rules, workers can qualify for SIBTF benefits even if the pre‑existing condition does not interact with (or worsen the impact of) the work injury. The Legislature could instead require that pre‑existing conditions make the new injury worse or render the worker substantially less employable than they would have been without the pre‑existing condition.

- Revisit How Pre‑Existing Conditions Are Stacked Under Todd Decision. The final option to consider is reversing or narrowing the Todd case ruling that allows multiple pre‑existing conditions to be stacked, thereby making it easier to obtain 100 percent permanent disability benefits. One approach here would be to align SIBTF with the longstanding workers’ compensation policy of adjusting multiple combined impairments downward to account for functional overlap as is the practice in the standard workers’ compensation system.

- Additionally, Consider Options to Fast‑Track Urgent Claims in the Backlog. SIBTF claims processing delays may soon stretch to ten years. Mindful of the state’s limited capacity to immediately work through all backlogged claims, the Legislature could consider creating a fast‑track process for especially urgent or severe cases. (Over the longer term, additional state staffing could be contemplated to work through the remaining claims.) A similar approach is used by federal administrators of the SSDI program, which uses “compassionate allowances” to expedite benefits for workers with serious illnesses. A similar approach could identify SIBTF claimants with profound disabilities or extreme hardship and move their cases forward quickly.

Taken together, these options would better align the state’s SIBTF program with its original purpose. In our view, no single option would be enough to refocus SIBTF due to how far the program has drifted from that original purpose. Furthermore, any legislative changes will require close monitoring to ensure they have the desired effect and to correct any unintended consequences that emerge in practice.