Will Owens

June 12, 2025

An Update on the Public Health Laboratory System After the Pandemic

Introduction

The public health system in California includes multiple public and private entities, and a key component is the public health laboratories. The state and several local health jurisdictions (LHJs)—mostly counties and a few cities—have laboratories that provide public health laboratory testing services. (When referring to counties and LHJs, we are also referring to these city LHJs.) For example, public health laboratories perform wastewater testing to monitor disease outbreaks or provide environmental testing for dangerous contaminants following a natural disaster. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, local public health laboratories experienced flat or declining funding levels and workforce challenges that led to a number of laboratory closures. In response to the gaps in the public health infrastructure identified during the COVID-19 pandemic, the state and federal government provided public health laboratories with additional funding and established new initiatives to improve laboratory capacity. Some of these additional resources were temporary in nature, however, the state provided about $300 million in new ongoing resources for public health efforts starting in 2022-23 (reduced to $276 million beginning in 2024-25 and ongoing).

This post provides background on the role of the public health laboratory system and changes that occurred during and in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. We also provide a framework for the Legislature to use to assess the capacity of the laboratory system and whether any capacity gaps warrant further action.

Background

The Public Health System

What Is the Public Health System? In California, the public health system is operated by state and local governments to promote healthy behaviors, prevent disease, and respond to emergencies that impact the health of Californians. Public health is distinct from health care in that it focuses primarily on the health of communities rather than treating individuals for their specific health issues.

Public Health Services Are Primarily the Responsibility of Counties. Since 1991 realignment, counties have received additional funding and been responsible for providing the majority of public health services within their jurisdictions, including communicable disease control, immunizations, public health outreach and education, and public health laboratory services. LHJs will often tailor the focus of their public health services to the specific needs of their communities.

The California Department of Public Health (CDPH) Is Responsible for a Number of Statewide Public Health Initiatives and Provides Guidance and Funding to LHJs. The CDPH performs a wide variety of public health activities including licensing and certification for a number of health facilities, prevention and response to infectious diseases, childhood lead poisoning prevention, and tobacco cessation efforts. While LHJs are responsible for many of the public health services directly received by Californians, CDPH focuses primarily on population-wide public health initiatives such as education campaigns or coordinating statewide disease outbreak responses. In addition, CDPH has a significant role in providing guidance and technical assistance to LHJs. In 2024-25, CDPH’s budget is approximately $5.3 billion, with about $1 billion General Fund and the remaining funding from federal funds, special funds, and other sources. Approximately 37 percent of CDPH’s budget is for state operations, with the remainder going to LHJs.

The Structure and Funding of the Public Health Laboratory System

Public Health Laboratories Are a Key Component of Public Health Infrastructure. Many of the public health services performed by the state and LHJs require laboratory services. Public health laboratories are highly regulated entities that provide laboratory testing services to advance public health objectives, including wastewater testing to monitor disease outbreaks, genetic sequencing of unknown pathogens, and environmental testing for certain contaminants following a natural disaster. Public health laboratories often act as the first entity involved in identifying disease outbreaks in the state and are key in informing subsequent public health responses from CDPH and LHJs.

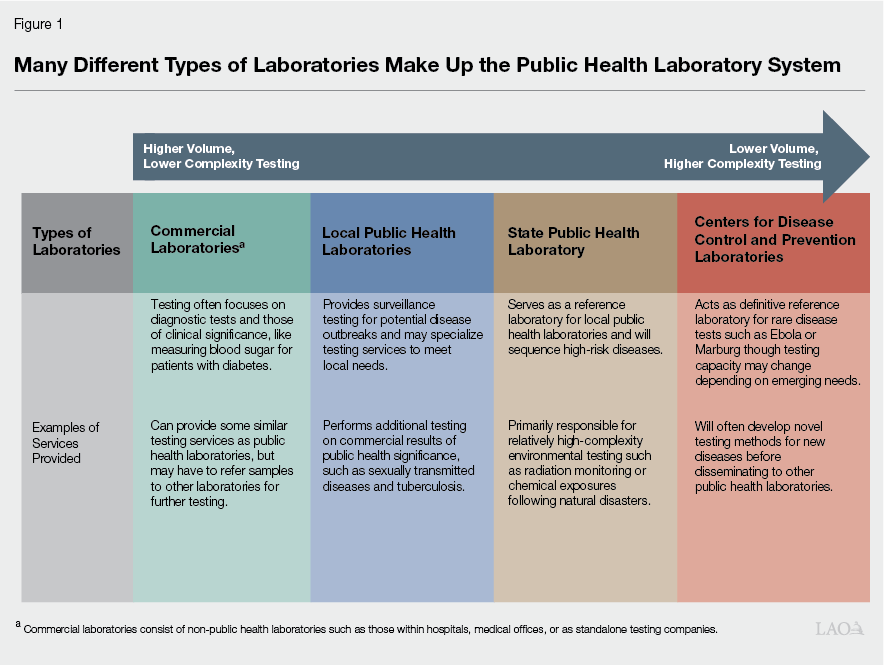

Public Health Laboratory System Includes Many Public and Other Entities. The public health laboratory system is made up of federal, state, local, and commercial laboratories that each perform different testing services at varying levels of complexity and volume. (Commercial laboratories are other entities that are not designated as public health laboratories, but perform testing services that inform public health testing.) Figure 1 describes, at a high level, the role of the different types of laboratories that provide testing services for the state’s public health system.

Local Public Health Laboratories Are Responsible for Majority of Public Health Testing. There are 28 local public health laboratories in California that, in general, are the primary testing entity for disease surveillance and outbreak monitoring in the state. This can take a few forms:

Commercially Identified Pathogens. Commercial laboratories are required to report results of certain pathogens that may have wider public health implications to local public health laboratories (and/or to CDPH in some cases depending on the pathogen). Once local public health laboratories receive test results from commercial laboratories they may perform higher-complexity tests to further characterize the disease and help inform other public health agencies.

Potential Outbreaks. In some cases, once a pathogen is detected, local public health laboratories may supplement their testing services with assistance from other laboratories or the state public health laboratory, particularly in cases where there is an unexpectedly high volume of tests needed or an outbreak of a novel disease.

Local Needs. Local public health laboratories may also perform testing that is specific to the characteristics of the jurisdiction they serve. For example, local public health laboratories along the coast may perform wastewater testing while those in rural areas of the state may perform more tests for diseases that impact livestock.

State Public Health Laboratory Provides Enhanced Testing Services and Local Public Health Laboratory Support. The state public health laboratory has six branches that specialize in different testing services, and in 2023, five of these were reorganized into the Center of Laboratory Sciences (CLS), which provides direct oversight of almost all state laboratory testing. These laboratory branches include specializations such as food and drug testing, environmental health testing, genetic testing, and infectious disease testing and surveillance. The state public health laboratory acts as the reference laboratory for the state, and as such, provides more complex testing services needed to further characterize pathogens identified at the local level. For example, a local public health laboratory may identify an influenza outbreak, but depending on its capacity, may require the state public health laboratory to test what specific strain is the source of the outbreak to better identify the appropriate response. The state public health laboratory also provides relatively complex environmental and chemical testing services that are generally not performed by local public health laboratories. The state public health laboratory may also provide technical assistance or supplies needed for certain tests to local public health laboratories.

State and Local Public Health Laboratories Participate in Several Networks to Strengthen Testing Capabilities. In addition to providing general public health testing services, public health laboratories will often participate in networks that specialize in testing for, and reporting on, different diseases. Certain networks operate among public health laboratories in California, while other networks work nationally with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and public health laboratories in other states. By participating in these networks, certain public health laboratories may receive supplemental funding or supplies as well as be among the first laboratories to implement new testing methodologies for emerging diseases.

Public Health Laboratories Are Governed by State, Federal, and Laboratory Network Requirements. California statute requires all public health laboratories to receive a specified federal certification, and the state public health laboratory is responsible for ensuring that local public health laboratories meet this certification and enforce other regulations related to public health laboratories. Public health laboratory directors and public health microbiologists are also regulated occupations and make up the core of public health laboratory staff. All laboratories must also report certain diseases of public health significance to state and local public health laboratories, a list of which is laid out in California regulations. Many public health laboratories also participate in laboratory networks, some of which have specific requirements for laboratory staffing and capacity in order to perform the appropriate testing.

State and Local Public Health Laboratories Are Supported by Multiple Funding Sources. In 2024-25, approximately 60 percent of CLS’s budget of $77 million (total funds) is supported by the General Fund, with the balance coming from a mix of federal funds and state special funds. Local public health laboratories receive a mix of 1991 realignment funding, local assistance from CDPH, federal funding, and other county funds. Local public health laboratories may also collect laboratory fees or receive reimbursements from the state Medicaid program for certain tests. However, these represent a relatively small portion of public health laboratory budgets. Comprehensive data on local public health laboratory funding is not available, however. Counties have significant discretion in how they allocate 1991 realignment funding for health, only a portion of which may support laboratories (in addition to other public health activities, 1991 realignment health funds also can support indigent health care). The state has not required counties to report on most public health spending or how much is provided to public laboratories, which limits the ability of the Legislature to assess how much total funding is used to support laboratory services.

COVID-19 Pandemic Highlighted Testing Gaps

Public Health Laboratories Faced Challenges Prior to COVID-19 Pandemic

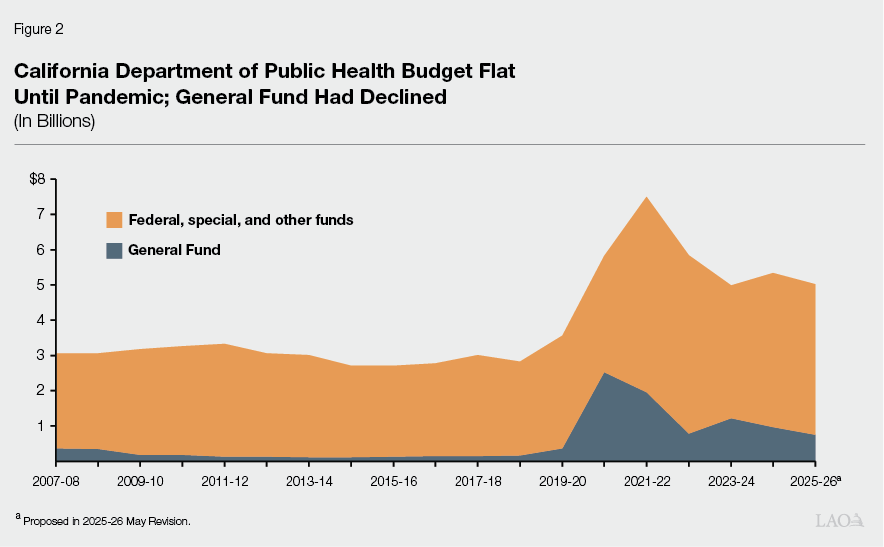

Overall State and Federal Funding for Public Health Remained Flat for Decade Prior to COVID-19. Between 2007-08, when CDPH became a standalone department (it was formerly a division within the then Department of Health Services), and the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2019-20, the overall CDPH budget was relatively flat and was about $3.4 billion (total funds) at its highest. (As noted above, a substantial portion of CDPH’s funding—ranging from 67 percent to 83 percent prior to the pandemic—is distributed to LHJs. In addition, LHJs have local sources of funding, like 1991 realignment.) General Fund support in the CDPH budget declined significantly in 2009-10 (during the Great Recession) and was never fully restored before the pandemic. (Overall funding remained relatively flat due to federal and special funding sources.) Lower General Fund support limited the ability of CDPH, and consequently LHJs, to fund more general or broad-based public health activities that were not subject to the spending constraints of categorical funding sources (federal and special funds that are limited to only certain uses). The most support that CDPH’s budget received from the General Fund prior to the pandemic was in its first year as a standalone department: $361 million in 2007-08. Figure 2 shows these pre-pandemic funding trends, as well as funding trends during and after the pandemic (discussed later).

Many Local Public Health Laboratories Had Closed in Years Prior to the COVID-19 Pandemic. Beginning in 1999 and through the pandemic, 12 local public health laboratories (out of a total of 40 laboratories at their peak) closed or become inactive for a variety of reasons including insufficient funding, staffing shortages, decreased demand for services, and challenges in recruiting public health laboratory directors. LHJs that no longer operate a public health laboratory contract with other local health laboratories and the state’s public health laboratory for testing services. Public health laboratories indicate that during this period many laboratories did not receive funding to modernize infrastructure, limiting their ability to adopt new technology or scale testing services during emergencies.

Onset of COVID-19 Pandemic Highlighted Critical Role of Public Health System and Exposed Gaps in the Laboratory Infrastructure. State and local public health laboratories mobilized at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, setting up networks of laboratories to track and sequence outbreaks of the virus. As the COVID-19 pandemic unfolded, however, the state’s public health systems quickly became overwhelmed. CDPH and LHJs did not have enough staff to respond and the demands placed on information technology (IT) systems and public health lab testing quickly exceeded their capacity. Outdated laboratory IT systems made it difficult for the state public health laboratory to collect laboratory results necessary to track COVID-19 outbreaks across the state and limited its ability to manage testing inventory. Many local public health laboratories had to perform manual data entry or acquire and conduct training on completely new testing systems early on in the pandemic, significantly hampering the state’s ability to track and respond to outbreaks.

Recent Federal and State Initiatives Supporting Public Health Laboratories

As shown in Figure 2, the state and federal government provided a significant amount of supplemental funding in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. This supplemental funding supported a wide variety of activities to respond to a surge in the level of demands on the public health system. This funding included support to CDPH and LHJs for contact tracing, vaccine distribution, increased testing capacity, and other services. In addition, a share of the funding provided to CDPH and LHJs during this time was ongoing to develop and improve public health capacity more broadly. This section describes some of those initiatives, as well as ongoing efforts to support public health and laboratories after the pandemic.

Local Public Health Laboratories Received Supplemental Federal Funding During COVID-19 Pandemic. Public health laboratories have typically received regular funding from the federal government through the Epidemiology and Laboratory Capacity (ELC) grant program. In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, the federal government enhanced this grant program to bolster public health agencies as well as public health laboratories in California and across the country. Local public health laboratories used this temporary supplemental funding to upgrade equipment and hire staff to bolster laboratory capacity during the pandemic. This capacity-building funding has allowed some local public health laboratories to begin providing other testing services they did not have the technology for in the years prior. There is currently around $70 million in supplemental ELC funding that remains available for expenditure by local public health laboratories in California through 2026-27. (At the time of this post, the CDC has issued an order to rescind at least a portion of these funds prior to their original end date.)

Recent State Workforce Programs Target Public Health Laboratory Workforce. The 2022-23 budget enacted a health workforce package that spanned multiple departments and supported various workforce initiatives focused on health and home care, behavioral health care, primary care, public health, and reproductive health care. Of the public health workforce initiatives, two directly targeted public health laboratory workforce needs: the LabAspire Fellowship Program and the Public Health Microbiologists Training Program. The workforce package included around $10 million for each program. The LabAspire program provides fellowship opportunities that help to facilitate a pipeline of qualified individuals to act as public health laboratory directors for local public health laboratories in the state. This program has trained or is training 17 graduates, 12 of whom are currently serving as laboratory directors in local public health laboratories. The Public Health Microbiologists Training program provides six months of no-cost training for individuals to become a certified public health microbiologist, one of the key occupational classifications needed to staff local public health laboratories. Since the passage of the 2022-23 budget, there have been 58 graduates of this program. In the Governor’s proposed May Revision, approximately $3.4 million for these programs is proposed for reversion.

Future of Public Health (FoPH) Funding Supplements State and Local Public Health Laboratory Funding on an Ongoing Basis. The COVID-19 pandemic highlighted the gaps in the public health system and, following a report issued by CDPH, LHJs, and other public health entities, CDPH released a spending plan to bolster the public health system with additional General Fund support. The 2022-23 budget included $300 million General Fund ongoing for state and local health departments, though this amount was reduced to $276 million General Fund ongoing as part of a budget solution in the 2024-25 budget. CDPH receives $92 million to support six foundational spending areas, including 25 positions in CLS, and is responsible for providing coordination, planning, and technical assistance to LHJs as they build up their infrastructure. LHJs receive the remaining $184 million for which they submit spending plans to CDPH detailing how the funds will be used to support public health and of which at least 70 percent of which must be used on staffing. Based on LHJs spending plans, 76 of the 1,253 proposed new public health staff are for public health laboratories. However, how much of the FoPH funding is used for non-staff public health laboratory infrastructure is unknown.

Public Health IT Initiatives Support Laboratory Operations. In addition to the FoPH funding supporting public health workforce and service capacity, the 2022-23 budget included funding and position authority to maintain and implement a dozen IT systems involved in—or developed specifically for—the state’s COVID-19 response. Below, we describe a few of the major IT projects that support public health laboratories for which planning, development, and/or implementation began during or after the pandemic.

Surveillance and Public Health Information Reporting and Exchange (SaPHIRE). During the COVID-19 pandemic, the state had difficulties managing the high volume of laboratory data associated with the pandemic and local public health laboratories did not have a consistent system to report COVID data. In response, the state developed the California COVID Reporting System (CCRS) to better handle the high volume of data as well as be interoperable with other COVID systems such as case investigation and contact tracing. In 2022, CDPH expanded the scope of CCRS to include other reportable diseases and renamed it SaPHIRE. In addition to local public health laboratories, commercial laboratories and healthcare providers can directly upload test results to the system. The Governor’s 2025-26 budget proposes $27 million General Fund in 2025-26, $20.4 million General Fund in 2026-27, and $16.3 million in 2027-28 and ongoing to support the system.

Laboratory Data Exchange (LDX) Project. CDPH received a $10 million grant from the CDC for the LDX project, an effort to modernize the state’s electronic laboratory data exchange systems. The project aims to connect laboratory inventory management, emergency response activities, and laboratory results reporting between state and local public health laboratories. While SaPHIRE facilitates reporting to the state’s primary disease surveillance system, LDX would connect all components of public health laboratory systems and provide data exchange between local public health laboratories as well. LDX would also help to automate a number of laboratory reporting functions to further reduce staff time spent on submitting and processing test results. CDPH is in the process of developing and testing a number of components for the project, but a final time line for completion is unknown.

Revamp of the California Reportable Disease Information Exchange (CalREDIE) in Early Stages. The CalREDIE system is the state’s central disease surveillance system that collects a wide variety of public health data from other IT systems (including laboratory results from SaPHIRE and the state’s contact tracing system) and connects those data. During the pandemic, CalREDIE was unable to handle the high volume of data collected and has had difficulty interfacing with new systems that have been developed since the onset of the pandemic. The state is currently working on a new disease surveillance system that would mitigate the problems that arose during the pandemic including improving its capacity to process large amounts of data; reducing the amount of manual data entry; and allowing public health officials to access real-time, consolidated disease outbreak information. The project is still in the early stages of the IT project approval process and no cost estimate exists.

Issues for Legislative Consideration

What Are the Resource Requirements for Public Health Laboratories?

While the State’s Recent Augmentations Appear to Have Improved Public Health Laboratory Capacity… The COVID-19 pandemic highlighted the gaps in the state’s public health system, in particular, public health laboratories required significant supplemental funding to respond to the pandemic while simultaneously upgrading existing systems and maintaining ongoing public health activities. In response, the Legislature prioritized providing additional funding for state and local public health laboratories through the FoPH funding, public health laboratory workforce initiatives, and IT system modernization efforts. This additional state support, along with supplemental federal funding, appears to have helped to increase public health laboratory capacity and resulted in improved responses to recent outbreaks such as the H5N1 outbreak of avian influenza.

…Data to Fully Assess Those Improvements Is Lacking. Although there is evidence that one-time, temporary, and new ongoing support to public health laboratories has improved laboratory operations, the state does not collect systematic data to assess laboratory funding and capacity. Absent this information, the Legislature cannot determine whether the improvements to the laboratory system—including new technologies and reporting systems—are sufficient. Below, we lay out a framework that, provided sufficient data, could inform the Legislature’s assessment of public health laboratory resource requirements.

What Is the Total Funding for Local Public Health Laboratories? Although the state has some insight into federal and state sources of funding for public health laboratories, there are some gaps. Specifically, the state does not collect data on the share of 1991 realignment funds flowing to laboratories, nor does the state collect data on other funding sources—like fees or county funds—laboratories could receive. Collecting this data would be necessary in order to assess the fiscal landscape of the public health laboratories.

What Is the Capacity of the Laboratory System? While there is no single metric to assess the laboratory system capacity, there are a few metrics that could inform an assessment of the system’s abilities. These include: (1) staffing resources; (2) laboratory equipment resources and the types of tests that can be performed; (3) the number and types of tests performed annually over the last several years; and (4) if applicable, the extent to which existing levels of staffing and equipment allow for testing above current levels. Combining these metrics with similar information for the state laboratory would give a high-level view of the current capacity of the public health laboratory system as a whole. While some of the data related to local public health laboratories is already collected, such as LHJ’s spending plans for FoPH funding, these data have not yet been used to inform an assessment of the public health laboratory system’s overall capacity.

Does the Laboratory System’s Capacity Meet Core Responsibilities? Based on the assessment of the laboratory system’s capacity, the Legislature could assess whether that capacity appears to be sufficient to meet the system’s core responsibilities. (These responsibilities are broad, but are laid out in Sections 101150 - 101165 of the Health and Safety Code and Sections 1075 - 1084, Title 17 of the California Code of Regulations.) This assessment also could look at potential regional capacity differences and the extent to which laboratories can handle novel disease testing or high volumes of testing during an outbreak.

With Data in Hand, the Legislature Can Assess if There Is a Capacity Gap. Based on the data collection and assessments laid out in the framework above, the Legislature would be able to determine if there are any capacity gaps. That is, whether the public laboratory system is able to meet its core responsibilities at its existing funding level. To the extent there are gaps, the Legislature could determine what resource level might be required to address them. Understanding the resource level needed for the state’s public health laboratory system may be particularly important given recent federal actions or proposals to reduce or revert funding for the public health system more broadly. In addition, the Legislature could assess whether the level of “surge” capacity is sufficient based on potential risks. While collecting this data and conducting this assessment could be challenging, we advise the Legislature to consider giving CDPH this reporting requirement over the next year or so.

Updated Public Health IT Systems Important Piece of Public Health Laboratory System

Recently Developed and Planned IT Systems Can Help Improve Public Health Laboratory Functions. Outdated and fragmented public health IT systems proved to be a major hurdle in the state’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic, and as a result, the Legislature has appropriated significant funding in recent years to upgrade these systems. Public health laboratories rely, more than other parts of the public health system, on complex IT systems that can process and synthesize a high volume of data. Some of the systems developed during the pandemic, such as SaPHIRE, have had a major impact on how public health laboratories report laboratory results to the state and has the potential to significantly improve this function. Additionally, some of the department’s planned IT projects, such as the LDX and revamped disease surveillance system, have the potential to dramatically change, as well as improve, how public health laboratories collect, report, and monitor data. CDPH is currently in the process of developing a strategic plan for its IT systems and its IT projects at various stages of development. Given the important role that IT systems play in public health laboratory operations, the Legislature may consider working with the administration to ensure these projects are developed in alignment with legislative priorities for the public health laboratory system as a whole.

Public Health Laboratory IT Systems Help in Evaluating Laboratory System Capacity. Aside from the role recently developed IT systems play in current public health laboratory functions, these systems—when complete and fully integrated—could significantly assist in evaluations of the system’s ongoing capacity. The end of limited-term supplemental support from the federal government, in particular, may impact the development of public health laboratory IT systems. Without these upgraded systems, the state’s ability to assess the capacity of the public health laboratory system would be constrained.