Caitlin O'Neil

June 12, 2025

Retail Theft in California

Looking Back at a Decade of Change

- Introduction

- What Is Retail Theft?

- How Has the Rate of Retail Theft Changed Over the Past Decade?

- What Changes in the Criminal Justice System Might Have Impacted Trends in Retail Theft?

- How Might These Criminal Justice System Changes Have Impacted Retail Theft?

- What State Law Changes Have Been Made to Address Retail Theft?

- What Are Key Questions for Legislative Oversight?

- Conclusion

Executive Summary

Retail Theft in California Has Increased in Recent Years. Over the past decade, the rate of reported retail theft ticked up slightly in 2015 before declining through 2021. About half of this decline occurred between 2019 and 2020, suggesting that factors such as temporary stay‑at‑home orders and closure of nonessential retail businesses in the early part of the COVID‑19 pandemic likely contributed. Subsequently, retail theft rebounded between 2021 and 2023. Over the entire ten‑year period—2014 to 2023—reported retail theft increased by about 11 percent, though some counties experienced differing trends. Despite the statewide increase, reported retail theft remains well below historical highs that occurred in the 1980s.

Various Changes in the Criminal Justice System Could Have Impacted Retail Theft Trends. Proposition 47 (2014) limited punishment for most types of retail theft involving $950 or less to a misdemeanor, when previously, some of these crimes could be punished as felonies. In doing so, Proposition 47 changed how these crimes are handled at certain key stages of the justice system. This is because law enforcement generally has more limited authority to arrest people for misdemeanors than felonies. In addition, many changes in the criminal justice system occurred during the COVID‑19 pandemic. Some were directly tied to public health responses (such as early releases from prison), while others just happened to coincide with the timing of the pandemic (such as a reduction in probation term lengths). Taken together, these changes may have impacted retail theft rates by reducing (1) the likelihood people are apprehended for crime and (2) the number of people incarcerated at a given time who might otherwise commit crime. Researchers found that Proposition 47 increased larceny (a category of crime that includes some forms of retail theft) though they were unable to determine the impact on retail theft specifically. Additionally, they found that pandemic‑era changes to the criminal justice system increased nonresidential burglary (a measure of some forms of retail theft) by reducing jail populations and the likelihood of arrest. However, the researchers were only able to explain about one‑third of the pandemic‑era increase in nonresidential burglaries. This suggests that factors outside the criminal justice system—such as changes in the retail environment—likely contributed to retail theft trends in California as well.

Legislature and Voters Recently Enacted Various Law Changes to Address Retail Theft. In response to growing concerns, the Legislature and voters have enacted several law changes aimed at reducing retail theft, including Proposition 36 (2024) and various bills, such as Chapter 168 of 2024 (AB 2943, Zbur). These changes seek to reduce retail crime by (1) increasing the authority for law enforcement to arrest and detain shoplifters, (2) elevating retail theft from a misdemeanor to a felony in some cases, (3) increasing term lengths for retail crime, and/or (4) increasing capacity to detect and respond to retail crime. For example, changing crimes from misdemeanors to felonies will cause people to spend a longer time incarcerated—reducing their subsequent opportunity to commit crime. This change could also make it more likely for people to be arrested given that law enforcement generally has greater authority to arrest people for felonies. This, in turn, could help deter people from engaging in retail theft if it causes them to perceive a higher likelihood of apprehension.

Legislature Can Ask Several Key Questions to Conduct Oversight of Recent Law Changes. Below, we identify key questions that the Legislature might want to ask as it conducts oversight of the recent law changes made to address retail theft:

- Are practitioners, stakeholders, and the public aware of the changes?

- Are practitioners and stakeholders using the new tools available to them?

- How are practitioners and stakeholders using the new tools?

- Are promising practices being captured and shared?

- Are the laws robust to technological change?

- Is reported retail theft going down?

- Are clearance rates (a measure of the likelihood of being apprehended) going up?

- Are there unintended consequences?

- How much have justice system costs increased?

- Do the benefits outweigh the costs?

Collecting answers to these questions will allow the Legislature to both monitor the implementation of the law changes and help it assess whether they are successful in reducing retail theft.

Introduction

Concerns about theft from retail businesses have become more prominent in recent years. Retail theft has implications for economic outcomes, as well as a sense of safety, well‑being, and fundamental quality of life for Californians. In response, the Legislature and the voters have approved several law changes intended to reduce retail theft. The purpose of this report is to provide background on trends in retail theft over the past decade, discuss some of the possible contributors to these trends, describe recent retail theft‑related law changes, and outline key questions that the Legislature may want to ask as it continues to provide oversight of this issue.

What Is Retail Theft?

Retail Theft Is a General Term That Includes Different Types of Crimes. While there is not a universally agreed upon definition of “retail theft,” the term typically refers to situations in which a retail business is a victim of a theft‑related crime. Depending on the specific circumstances of the crime—such as the value of property stolen or the method in which it was stolen—it can be reported and prosecuted as various specific crimes. Such crimes include burglary, shoplifting, embezzlement, vandalism, and robbery.

No Exact Measure of Retail Theft Incidents. The number of incidents in which retail businesses are victims of theft‑related crime is not tracked in statewide crime statistics. This is because statewide crime statistics are generally not tracked by the type of victim. For this report, we use reported incidents of shoplifting and burglary of a nonresidence as a way to approximate the level of retail theft. Shoplifting is defined as entering a commercial establishment during business hours with intent to steal $950 or less in merchandise. Burglary involves entering a house, store, vehicle, or other place with intent to steal, regardless of the dollar amount. State crime statistics track burglary of residences and nonresidences separately. Because retail businesses are typically not residences, we use just the subset of reported burglaries that are of nonresidences.

How Has the Rate of Retail Theft Changed Over the Past Decade?

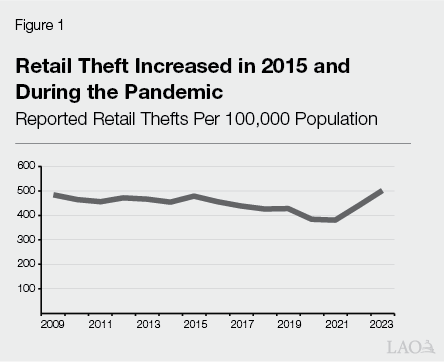

California’s Retail Theft Rate Increased in 2015 and Again During the Later Stage of the Pandemic. As shown in Figure 1, the annual rate of reported retail theft incidents has fluctuated. Between 2014 and 2015, retail theft increased slightly (5 percent) before declining by a total of 20 percent between 2015 and 2021. About half of this decline occurred between 2019 and 2020. Pandemic‑related factors—such as temporary stay‑at‑home orders and closure of nonessential retail businesses in the early part of the pandemic—likely contributed to the decline over this period. Subsequently, between 2021 and 2023, retail theft increased by 32 percent. Over the entire ten‑year period—2014 to 2023—reported retail theft increased by 48 crimes per 100,000 people, or 11 percent. Furthermore, an unusually large number of law enforcement agencies—whose jurisdictions include roughly 10 percent of the state population—did not report crime numbers for some or all of 2023. (For example, San Bernardino Sheriff’s Department did not report crime data for seven months of 2023.) Accordingly, crime data may understate the actual increase in retail theft that occurred in 2023.

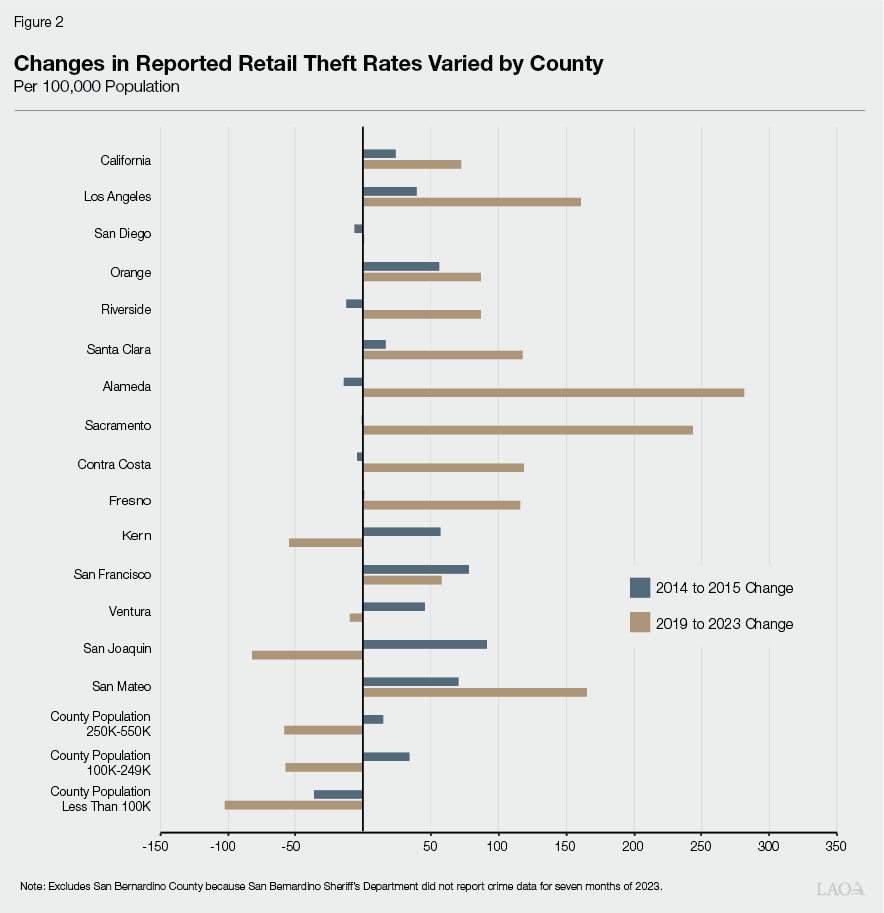

Some Counties, However, Experienced Different Trends Than California as a Whole. As shown in Figure 2, unlike the state as a whole, some counties experienced a decrease in retail theft rates between 2014 and 2015. In addition, county increases in retail theft during the pandemic era (which we measure as changes between 2019 and 2023) were primarily concentrated in larger counties, particularly Los Angeles, Alameda, Sacramento, and San Mateo Counties. In contrast, small counties tended to experience declines in retail theft over this period. The reason for these differences is unclear but could be tied to factors such as the concentration of retail establishments in each county.

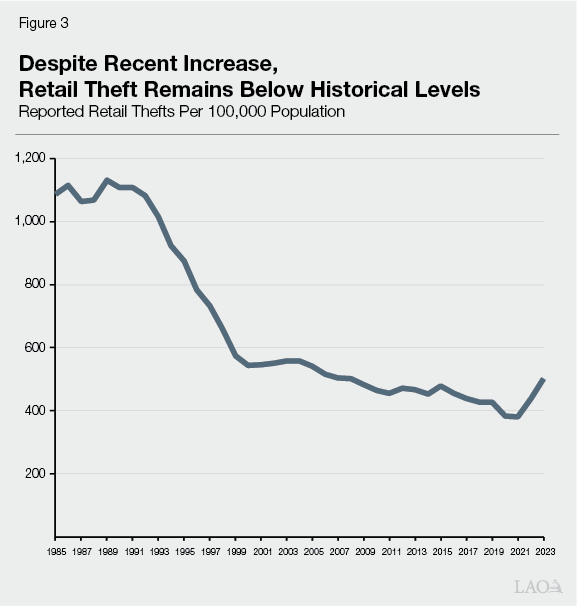

Retail Theft Remains Well Below Historical Levels. As shown in Figure 3, despite increases over the last decade, the retail theft rate remains well below historical highs that occurred in the 1980s. Specifically, between 1985 and 2023, the retail theft rate declined by 54 percent. (A similar decline occurred for all types of property crime during this period, including residential burglary and motor vehicle theft.)

What Changes in the Criminal Justice System Might Have Impacted Trends in Retail Theft?

A wide range of factors likely had some effect on retail theft trends over the past decade. This report focuses on changes in the criminal justice system. Below, we provide background on several notable changes in the criminal justice system—specifically Proposition 47 (2014) and pandemic‑era changes—that could have contributed to the trends in retail theft observed over the past decade. However, various economic, technological, and social changes outside of the criminal justice system could have also impacted trends in retail theft over the past decade. See the nearby box for a brief overview of these changes.

Changes Outside of the Criminal Justice System Likely Have Impacted Retail Theft Trends

Many different factors can affect the rate of retail theft, including those that are not directly related to the criminal justice system. Below, we identify a few examples of other types of factors that could have affected retail theft rates over the past decade.

Changes to the Retail Environment. It is possible that changes in the retail environment may have affected retail theft rates. For example, expansion of self‑checkout lines and store policies that direct staff not to physically confront shoplifters may have made some people feel that they have a higher chance of avoiding apprehension. In addition, pandemic‑era changes—such as the broader use of face masks enabling one’s identity to be concealed—could have further emboldened shoplifters.

Broader Technological Changes. Broader technological changes may have also impacted people’s decisions about whether and how to commit retail theft. For example, social media may be making it easier for people to organize theft schemes or share ideas for how to commit thefts without getting caught. Moreover, online marketplaces are being used to facilitate the sale of stolen goods.

Changes in the Broader Social Context. There could be various other contextual factors that affect people’s decisions to engage in retail theft. For example, some people experiencing homelessness may steal to acquire necessities like food or to trade stolen items for temporary housing. Also, people with substance use disorders may steal items to sell or trade for drugs in the illicit market. Accordingly, changes to homelessness, addiction, illicit drug markets, or other social factors could have impacted retail theft rates.

Proposition 47

Proposition 47, which was approved by the voters in November 2014, changed state sentencing law for several lower‑level drug and property crimes. In particular, it changed how certain retail theft crimes are handled in the criminal justice system. We provide an overview of these changes below. Subsequent law changes—discussed later in this report—reversed some of the changes made by Proposition 47.

Converted Certain Theft Crimes Involving $950 or Less From Wobblers to Misdemeanors. Proposition 47 converted several crimes from wobblers (which are crimes that can be treated as either felonies or misdemeanors) to misdemeanors. These reduced punishments did not, however, apply to defendants with prior convictions for certain severe crimes (such as murder) or crimes requiring registration as a sex offender. The specific crimes affected by Proposition 47 that are most applicable to retail theft are as follows:

- Shoplifting. Prior to Proposition 47, stealing $950 or less of money or property from a store was sometimes treated as a wobbler punishable by up to three years in jail or prison. For example, if the defendant entered the store with intent to commit theft—as evidenced, for example, by their possessing a bag designed to conceal merchandise—they could be charged with burglary. Also, if the defendant had certain previous theft‑related convictions, they could be charged with “petty theft with a prior.” Both burglary and petty theft with a prior are wobblers. Proposition 47 requires that shoplifting involving $950 or less in value always be charged as a misdemeanor punishable by up to six months in jail, though it is common for people convicted of misdemeanors to be supervised in the community rather than placed in jail. (Using force or fear in the process of stealing merchandise is still considered robbery, which is a felony, regardless of the dollar amount involved. In addition, damaging property in the process of shoplifting is still considered vandalism, which is punishable as a felony if the damaged property is valued at $400 or more.)

- Receiving Stolen Property. Prior to Proposition 47, knowingly buying, receiving, or selling property that had been stolen was a wobbler, regardless of the dollar amount involved. This means someone could have been charged with a felony and sentenced to up to three years in prison or jail if their crime involved property worth $950 or less. However, Proposition 47 requires that receiving stolen property worth $950 or less be charged as a misdemeanor, punishable by up to one year in jail.

Prohibited Legislature From Making Amendments Inconsistent With Its Intent. Proposition 47 specifies that the provisions of the measure may be amended by a two‑thirds vote of the members of each house of the Legislature and signed by the Governor so long as the amendments are consistent with and further the intent of the measure. However, it allows the Legislature—by majority vote—to further reduce the penalties for any of the offenses addressed by the measure.

Impacted Arrest and Pretrial Detention Procedures for Crimes Converted to Misdemeanors. By converting crimes to misdemeanors, Proposition 47 resulted in them being processed differently at the following key stages of the criminal justice system:

- Arrest. Peace officers can arrest someone for a felony or wobbler as long as they have probable cause to believe the person committed the crime. To arrest someone for a misdemeanor, one of the following circumstances must also apply: (1) the crime was committed in the officer’s presence, (2) the crime was committed in the presence of a private person and that person delegates their authority to make a private person’s arrest (also known as a citizen’s arrest) to the peace officer, or (3) a specific exception to the “in the presence of” requirement applies (such as for misdemeanor domestic battery). This means someone suspected of a felony or wobbler may be more likely to be arrested than someone suspected of a misdemeanor.

- Pretrial Detention. People arrested for misdemeanors are generally either (1) cited in the field and released or (2) taken to the jail, booked (meaning the details of their arrest are recorded), and then released. In contrast, people arrested for felonies or wobblers are more likely to be placed into jail and held until their first court proceeding, known as arraignment. At arraignment, judges determine whether people will be detained or can be released while their case is being resolved.

Pandemic‑Era Changes

Many changes in the criminal justice system occurred during the COVID‑19 pandemic. Some were directly tied to public health responses, while others just happened to coincide with the timing of the pandemic. We describe some of the notable changes below.

Temporary Public Health Responses. Numerous actions to prevent the spread of COVID‑19 in the community, courtrooms, correctional facilities, and other workplaces affected the criminal justice system in various ways, such as the following:

- Modified Law Enforcement Policies and Practices. Local law enforcement agencies implemented various temporary policies to reduce interactions with community members in order to mitigate the spread of the virus. Examples include taking police reports online or over the phone instead of in‑person, issuing warnings instead of making arrests, or delaying planned arrests unless doing so would have jeopardized public safety. In cases where interactions with the public did occur, precautions to mitigate the spread of the virus may have slowed down processes in various ways. For example, requirements to clean jail booking areas more frequently could have slowed down the booking process and meant that officers were kept away from patrolling the community longer than usual.

- Zero Dollar Bail Orders. In April 2020, the Judicial Council (the policymaking and governing body of the judicial branch) adopted a statewide emergency bail schedule that set bail for arrestees at $0 for most misdemeanors and low‑level felonies. Local bail schedules applied otherwise. However, judges retained the ability to deviate from the bail schedules. This change substantially increased the number of people who were immediately released from jail after being arrested. While Judicial Council repealed this statewide directive after several months, a number of trial courts temporarily maintained zero dollar bail for various offenses for longer periods of time.

- Early Releases From Prison. Between April 2020 and December 2021, the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR) released certain people up to 365 days before their normal release date. Eligibility for early release was determined based on people’s criminal history; likelihood of committing future crimes; risk of complications from COVID‑19; and the need to reduce capacity at the prisons where they were housed to create space for physical distancing, isolation, and quarantine efforts.

Other Changes That Coincided With the Pandemic Era. There were various policy changes that occurred around the same time as the pandemic, but were not direct responses to the public health emergency. Some of these changes remain in place. Below, we discuss some of the notable changes.

- Reduction of Prison Terms Due to Proposition 57 (2016). In 2016, voters approved Proposition 57, which, among other provisions, expanded CDCR’s authority to reduce people’s prison terms through credits. With this additional authority, CDCR has taken several steps to date to increase credits. Some of these steps occurred in the pandemic era. For example, in May 2021, CDCR modified its regulations to allow people with convictions for violent crimes to earn up to 33.3 percent off of their sentence (an increase from 20 percent) for maintaining good behavior. Implementation of Proposition 57 is driving a long‑term downward trend in the prison population.

- Reduction of Probation Terms. Chapter 328 of 2020 (AB 1950, Kamlager) reduced maximum probation terms to one year for misdemeanors and two years for felonies. Previously, misdemeanor probation terms could last up to three years and felony probation terms could last up to the greater of five years or the maximum sentence for the crime the person was on probation for.

- Additional Modifications to Pretrial Practices. In addition to the zero bail orders mentioned above, the state implemented various other changes to its pretrial release practices and processes. For example, the 2021‑22 budget package provided the judicial branch with $140 million—a portion of which was ongoing—to support programs and activities aimed at reducing pretrial detention of people in jail, including funding for pretrial monitoring services. This made a two‑year pilot program initially funded as part of the 2019‑20 budget package permanent and expanded it statewide. Such changes may have reduced the number of people detained in jail pretrial.

- Changes in Law Enforcement Priorities. Various factors can affect how law enforcement agencies choose to prioritize their resources. For example, during the pandemic era, California—and the nation as a whole—experienced an uptick in violent crime. This likely caused law enforcement to shift resources away from property crime and other lower‑level crimes to prioritize addressing the increase in violence.

How Might These Criminal Justice System Changes Have Impacted Retail Theft?

As discussed earlier, a wide range of factors can affect crime rates. Within the criminal justice system, the available research has generally found that two key mechanisms can affect crime rates: (1) the likelihood of apprehension for crime and (2) the number of people incarcerated at a given time who might otherwise commit crime. Below, we discuss both of these mechanisms in more detail, and how Proposition 47 and pandemic‑era changes could have impacted observed retail theft trends in California through these mechanisms. Then, we summarize research finding evidence that Proposition 47 increased larceny (a type of theft that includes shoplifting as well as non‑retail thefts), though it remains unclear whether and how it impacted retail theft specifically. We also describe research that suggests criminal justice system changes during the pandemic‑era likely contributed to a modest portion of the recent increase in retail theft by reducing clearance rates and jail populations.

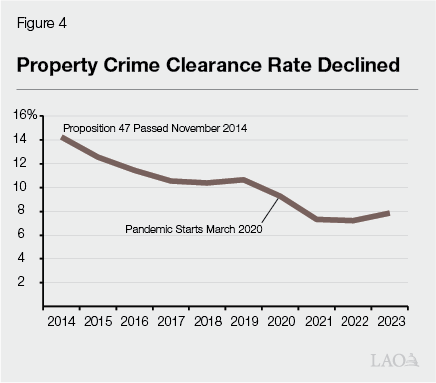

Decline in Likelihood of Being Apprehended Increases Willingness to Commit Crime. Generally, research on crime rates suggests that people are less likely to commit crime when they perceive that they have a higher chance of being apprehended. One measure of the likelihood of being apprehended for crime is the share of reported crimes for which police make an arrest and refer the arrestee for prosecution (or otherwise resolve the case). This is known as the “clearance rate.” As shown in Figure 4, California’s clearance rate for property crimes declined over the past decade from about 14 percent of reported crimes cleared in 2014 to about 8 percent in 2023. The decline was particularly sharp during the pandemic era. Proposition 47 and the pandemic‑era changes could have reduced clearance rates for various reasons. For example, as discussed above, by converting crimes from felonies to misdemeanors, Proposition 47 narrowed officers’ authority to make arrests for shoplifting. In addition, efforts to mitigate the pandemic may have reduced the likelihood that people would be arrested, particularly for lower‑level crimes, such as shoplifting.

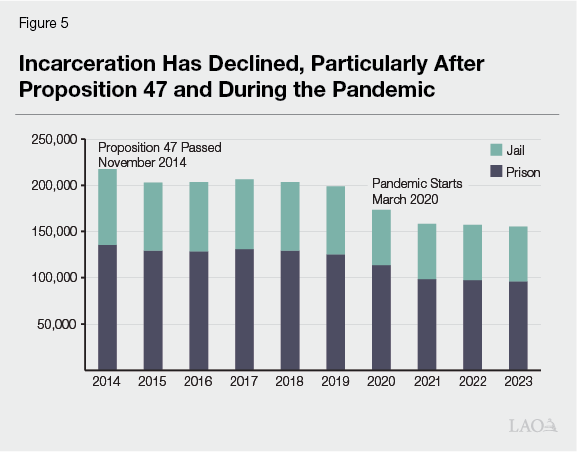

Reduced Incarceration Increases Some People’s Opportunity to Commit Crime. Generally, research evaluating crime rates across different locations and time periods has found that the level of incarceration is one mechanism through which criminal justice system changes can affect crime. In particular, when a policy lowers the level of incarceration—such as by reducing sentence lengths or changing pretrial detention practices—it leads to people having more time in the community and therefore more opportunity to commit crime. As shown in Figure 5, prison and jail populations have decreased substantially over the past decade, particularly as a result of Proposition 47 and the pandemic‑era changes. Specifically, the number of people incarcerated in either state prison or county jail declined by about 14,000 (7 percent) between 2014 and 2015 and by about 44,000 (22 percent) between 2019 and 2023. The people who did not have to spend time in prison or jail over this time period due to Proposition 47 and/or the pandemic‑era changes therefore had more opportunity to commit crimes—including retail theft.

Proposition 47 Likely Contributed to Increase in Larceny, Though Impact on Retail Theft Is Inconclusive. In a 2018 study, researchers at the Public Policy Institute of California (PPIC) found some evidence that Proposition 47 may have contributed to an increase in larceny. (Larceny is a type of theft that includes shoplifting as well as non‑retail thefts, such as stealing from a car.) Specifically, they found that the increase in California’s larceny rate immediately following Proposition 47 was 9 percent larger than that of similar states. In a 2024 study, PPIC researchers analyzed changes in prison and jail incarceration rates as well as property crime clearance rates to see if they were associated with changes in crime, including measures of retail theft. They were unable to reliably determine whether the changes in incarceration and clearance rates associated with Proposition 47 increased, decreased, or had no effect on retail theft. This was primarily because Proposition 47 changed the definitions of certain retail crimes, which may have affected whether and how the crimes were reported.

Pandemic‑Era Declines in Jail Population and Clearance Rates Partly Explain Retail Theft Trend. In their 2024 study, PPIC researchers found evidence that pandemic‑era changes impacted nonresidential burglary. Specifically, they found that the decline in the jail population and the decline in nonresidential burglary clearance rates during the pandemic era appear to have increased nonresidential burglaries by about 2 percent and 3 percent, respectively. (They did not find evidence of an impact of the decline in the prison population on retail theft.) Accordingly, consistent with the broader research, this study suggests that reductions in incarceration (in this case, the jail population specifically) and clearance rates likely contributed to increases in retail theft. However, the study was only able to explain about one‑third of the pandemic‑era increase in nonresidential burglaries, which suggests there are likely other key contributors to retail theft trends in California.

What State Law Changes Have Been Made to Address Retail Theft?

In response to growing concerns, the Legislature and voters have enacted several law changes aimed at reducing retail theft. In this section, we discuss several of these changes and the ways in which they might reduce retail theft. Figure 6 provides a summary of the changes. While some of these changes have been in effect for a few years, several were only recently enacted. Specifically, Proposition 36, approved by the voters in November 2024 became effective on December 18, 2024. In addition, a package of legislation signed into law in fall 2024 generally became effective on January 1, 2025.

Figure 6

Several Recent Law Changes Intended to Reduce Retail Theft

|

Primary Way(s) Changes Might Reduce Theft |

|||

|

Likelihood of Apprehension |

Incarceration |

||

|

Increased Authority for Law Enforcement to Arrest and Detain Shoplifters |

|||

|

Chapter 168 of 2024 (AB 2943, Zbur) |

Authorizes a peace officer to make a warrantless arrest for a misdemeanor shoplifting offense not committed in the officer’s presence if the officer has probable cause to believe that the person has committed shoplifting. |

✘ |

|

|

Chapter 803 of 2018 (AB 1065, Jones‑Sawyer) |

Adds conditions under which people arrested for shoplifting can be held in jail until arraignment, such as having previously been cited for theft from a store or vehicle in the last six months. |

✘ |

✘ |

|

Elevated Some Retail Theft Crimes From Misdemeanors to Felonies |

|||

|

Chapter 168 of 2024 (AB 2943, Zbur) |

Allows the dollar value of thefts committed by the same defendant against different retailers or in separate counties to be aggregated in order to achieve a felony conviction if they are substantially similar in nature or occur within a 90‑day period. |

✘ |

✘ |

|

Proposition 36 (2024) |

Allows the dollar value of thefts committed by the same defendant to be aggregated in order to achieve a felony conviction in all cases, including if the thefts are not similar in nature or do not occur within a 90‑day period. |

✘ |

✘ |

|

Chapter 165 of 2024 (AB 1779, Irwin) |

Allows the consolidation of theft charges that occurred in separate counties into a single trial if the district attorneys in all of the involved jurisdictions agree. |

✘ |

|

|

Chapter 803 of 2018 (AB 1065, Jones‑Sawyer) |

Establishes “organized retail theft” as a specific crime that involves working with other people to steal merchandise with an intent to sell it, knowingly receiving or purchasing such stolen merchandise, or organizing others to engage in these activities. If the value of the merchandise involved sums to more than $950 within a 12‑month period, such people can be charged with a felony. People who organize others to engage in retail theft can be charged with a felony, regardless of the dollar amount involved. |

✘ |

✘ |

|

Chapter 168 of 2024 (AB 2943, Zbur) |

Establishes “unlawful deprivation of a retail business opportunity” as a specific crime, punishable as a felony. The crime involves possessing more than $950 worth of stolen property with the intent to sell that property. For the purposes of determining if the $950 threshold has been met, the law allows the dollar value of multiple acts of possessing stolen property within a two‑year period to be aggregated. It also allows the dollar value of stolen property possessed separately by two people to be added if those people were working together. |

✘ |

✘ |

|

Proposition 36 (2024) |

Allows felony charges for people who commit shoplifting and have two or more past convictions for certain theft crimes (such as shoplifting, burglary, or carjacking). |

✘ |

✘ |

|

Increased Term Length for Some Retail Crimes |

|||

|

Chapter 168 of 2024 (AB 2943, Zbur) |

Allows a court to impose a two‑year term of misdemeanor probation for people convicted of shoplifting, as opposed to the standard one‑year term for misdemeanors. |

✘ |

|

|

Chapter 174 of 2024 (SB 1416, Newman), Chapter 220 of 2024 (AB 1960, Rivas), and Proposition 36 |

Allow increased sentences for people convicted of felonies in which the amount of property that was stolen or damaged is over $50,000, with longer enhancement terms as the dollar amounts increase. For example, if the affected property is worth more than $50,000 but not more than $200,000, a year can be added to the person’s sentence. If the property is worth more than $200,000 but not more than $1,000,000, two years can be added. |

✘ |

|

|

Proposition 36 (2024) |

Allows up to three years to be added to the sentences of people who worked with two or more other people to commit a felony involving theft or damage of property. |

✘ |

|

|

Increased Capacity to Detect and Respond to Retail Crime |

|||

|

Chapter 803 of 2018 (AB 1065, Jones‑Sawyer) |

Requires the California Highway Patrol to establish regional task forces to assist local law enforcement in addressing organized retail theft among other types of property crimes. |

✘ |

|

|

2022‑23 Budget Act |

Provided $85 million annually for three years to support competitive grants for local law enforcement to combat organized retail, motor vehicle, and cargo theft and $10 million annually for three years to support competitive grants to local prosecutors for vertical prosecution of organized retail theft. |

✘ |

|

|

Chapter 857 of 2022 (SB 301, Skinner) and Chapter 172 of 2024 (SB 1144, Skinner) |

Requires online marketplaces—platforms that enable third‑party sellers to sell goods directly to consumers—to collect information from certain high‑volume third‑party sellers and report sellers to law enforcement when there is reason to believe the seller is offering stolen goods for sale. |

✘ |

|

|

Chapter 169 of 2024 (AB 3209, Berman) |

Authorizes courts when sentencing a person for an offense involving theft, vandalism, or battery of an employee of a retail establishment, to issue a criminal protective order prohibiting that person from entering that retail establishment. Also authorizes prosecutors and attorneys representing a retail establishment to file a petition for the issuance of a criminal protective order against a person who has been arrested two or more times for any of these offenses at the same retail establishment. |

✘ |

|

Authority for Law Enforcement to Arrest and Detain Shoplifters Increased. Chapter 168 of 2024 (AB 2943, Zbur) expanded officers’ authority to arrest shoplifters and Chapter 803 of 2018 (AB 1065, Jones‑Sawyer) added conditions under which they can be held in jail until arraignment. This could help deter people from committing shoplifting if it causes them to perceive a higher likelihood of apprehension. Additionally, any time they spend in jail following arrest reduces their opportunity to commit more crime.

Retail Theft Elevated From Misdemeanor to Felony in Some Cases. Some law changes allow misdemeanor acts of shoplifting or possessing stolen property to be treated as felonies in certain cases. These felonies are punishable by up to three years in county jail or state prison depending on the person’s criminal history. By elevating punishments from misdemeanors to felonies, these changes will cause some people to spend a longer time incarcerated, which, in turn, could reduce crime by reducing people’s subsequent opportunity to commit crime. In addition, the changes could make it more likely for people who commit these offenses to be arrested and detained prior to arraignment given that law enforcement generally has greater authority to arrest and detain people for felonies. This could help deter people from engaging in retail theft if it causes them to perceive a higher likelihood of apprehension. We summarize these changes as follows:

- Aggregation of Multiple Incidents of Theft. Historically, the dollar value of multiple acts of shoplifting could generally not be aggregated to achieve a felony theft conviction (theft of over $950) unless it is proven that the separate acts of shoplifting are motivated by a common plan. Chapter 168 and Proposition 36 make it easier for the value involved in multiple acts of theft or shoplifting to be aggregated to meet the $950 threshold for a felony conviction. In addition, while it did not create a new crime, Chapter 165 of 2024 (AB 1779, Irwin) allows the consolidation of theft charges that occurred in separate counties into a single trial. This could facilitate aggregation of dollar values for thefts that occurred in multiple counties.

- Organized Retail Theft. Chapter 803 created the crime of “organized retail theft,” which allows some cases where people work together to commit retail theft to be charged as felonies instead of misdemeanors.

- Unlawful Deprivation of a Retail Business Opportunity. Chapter 168 created the crime of “unlawful deprivation of a retail business opportunity,” which allows the dollar value involved with multiple misdemeanor acts of possessing stolen property within a two‑year period to be aggregated into a felony.

- Shoplifting With Two or More Specified Prior Convictions. Proposition 36 established a new version of petty theft with a prior, which was previously generally eliminated under Proposition 47. This new law allows felony charges for people who commit shoplifting and have two or more past convictions for certain theft crimes (such as shoplifting, burglary, or carjacking).

Increased Term Lengths for Retail Crime. Some law changes increase the length of sentences or supervision for certain retail theft crimes. The most significant changes include:

- Misdemeanor Probation Term for Shoplifting. Chapter 168 allows a court to impose a two‑year term of misdemeanor probation for people convicted of shoplifting, as opposed to the standard one year for misdemeanors. It requires a court that imposes a term longer than one year to consider referring the defendant for services that are relevant to the underlying factors that led to their offense. (For example, someone stealing to support a drug addiction might be referred to substance use disorder treatment.) Being under probation supervision can increase the likelihood a person is arrested for crimes they commit or is referred to relevant services.

- Added Time for Certain Theft or Property Damage Felonies. Chapter 174 of 2024 (SB 1416, Newman), Chapter 220 of 2024 (AB 1960, Rivas), and Proposition 36 all added similar language to state law, which allows for increased sentences for people convicted of felonies in which the amount of property that was stolen or damaged is over $50,000, with longer enhancement terms as the dollar amounts increase. In addition, Proposition 36 allows up to three years to be added to the sentences of people who worked with others to commit a felony involving theft or damage of property. It is possible that these changes will reduce crime by causing people to spend a longer amount of time in jail or prison, thereby reducing their opportunity to commit crime. However, because these changes affect crimes that are already felonies, the affected people would already have been exposed to felony incarceration terms without these changes. These changes simply allow for them to be given longer incarceration terms.

Increased Capacity to Detect and Respond to Retail Crime. As discussed below, various other changes are intended to create increased capacity to detect and respond to retail crime with a focus on more sophisticated retail crime rings and people who engage in repeated and/or high‑volume thefts. These changes could reduce crime to the extent they increase the likelihood and/or perceived likelihood that people are arrested for retail crime. The most significant recent changes include:

- Establishment of State‑Level Task Forces. Chapter 803 required the California Highway Patrol (CHP) to establish regional task forces to assist local law enforcement in addressing organized retail theft among other types of property crimes. The Governor’s proposed budget for 2025‑26 includes $10.5 million from the General Fund (growing to $15 million in 2026‑27 and ongoing) to support these task forces.

- Grants to Local Law Enforcement and Prosecutors to Combat Organized Retail Theft. The 2022‑23 Budget Act provided $85 million annually for three years to the Board of State and Community Corrections (BSCC) to support competitive grants for local law enforcement to combat organized retail, motor vehicle, and cargo theft. In addition, the budget provided $10 million annually to BSCC for three years to support competitive grants to local prosecutors for vertical prosecution of organized retail theft. (Vertical prosecution is a strategy in which the same attorney is responsible for all aspects of a case from arraignment to disposition, which can promote consistency throughout prosecution of cases and the opportunity for attorneys to develop expertise in the content area.)

- Regulation of Online Market Places. Chapter 857 of 2022 (SB 301, Skinner) and Chapter 172 of 2024 (SB 1144, Skinner) require online marketplaces to collect information from certain sellers and report sellers to law enforcement when there is reason to believe the seller is offering stolen goods for sale.

- Retail Theft Restraining Orders. Chapter 169 of 2024 (AB 3209, Berman) authorizes courts to issue criminal protective orders prohibiting people from entering retail establishment where they have previously committed crimes. Chapter 169 also authorizes prosecutors and attorneys representing a retail establishment to petition for such orders against people who have been arrested two or more times at the same retail establishment. Protective orders allow employees to call law enforcement to have such people arrested before they commit additional crimes if they return to the establishment.

What Are Key Questions for Legislative Oversight?

Below, we identify key questions that the Legislature might want to ask as it conducts oversight of the recent changes made to address retail theft. First, we discuss questions intended to assist the Legislature in monitoring the implementation of recent law changes. Second, we discuss questions intended to assist the Legislature with monitoring key criminal justice system outcomes and costs to help it assess whether the changes were successful.

Oversight of Implementation

Are Practitioners, Stakeholders, and the Public Aware of the Changes? Recent law changes have given criminal justice system practitioners several new enforcement and prosecutorial tools. However, these tools will not be effective if these practitioners are not aware of them or do not fully understand them. Accordingly, the Legislature may want to ask representatives of law enforcement and prosecution agencies how they have been communicating with and training staff on these law changes. Similarly, some changes may require the awareness and collaboration of retailers in order to be effective. For example, to achieve a felony conviction by aggregating the dollar value of multiple thefts from different retailers, law enforcement will need each retailer to report the crime and provide evidence. If retailers are aware that their contribution could lead to a felony conviction under new laws, they may be more likely to dedicate the staff resources necessary for this collaboration. Finally, the Legislature may want to consider the extent to which the public is aware of the law changes. Broader public awareness of these new enforcement and prosecutorial tools could help deter people from committing retail theft by increasing the perception that they will get caught.

Are Practitioners and Stakeholders Using the New Tools Available to Them? Even if practitioners and stakeholders are aware of the new tools, the Legislature may want to assess the extent to which they are actually using these tools. For example, the Legislature may want to review conviction data or ask representatives of law enforcement agencies to determine how often the new crime of unlawful deprivation of a retail business opportunity is being used to arrest or prosecute in retail theft incidents. Similarly, it may want to consult with retailers to understand how often they choose to seek criminal protective orders under Chapter 169. If such tools are rarely being used, this could be a sign that they need to be modified. For example, it is possible that some laws may go unused because they are too onerous to be practical and may require revisions in order to achieve their intended effect. Alternatively, low utilization could be a sign that one of the other policy changes—such as Proposition 36—provided a broader authority for law enforcement and is therefore preferred by practitioners as a means to achieve the same ends.

How Are Practitioners and Stakeholders Using the New Tools? The Legislature may also want to get a sense of how the new tools are being used and how their use varies across the state. For example, Proposition 36 allows people who commit shoplifting to be convicted of a felony if they have two or more prior theft‑related convictions at any point in their past. However, some prosecutors’ offices may choose to ignore prior convictions that occurred more than a certain number of years in the past. Others may choose to consider all prior convictions. This implementation choice will help determine whether such felony convictions are broadly or narrowly applied. In addition, there could be variation in how the new tools are affecting different types of businesses. For example, new laws that allow separate acts of misdemeanor theft to be aggregated to achieve a felony conviction may be more helpful for corporate retailers with multiple stores operated by a single parent company than for franchises and small, independent businesses. This is because it is likely easier for parent companies to identify if the same individual has stolen from multiple locations so that they can be referred to law enforcement for felony charges.

Are Promising Practices Being Captured and Shared? Variation in local implementation could yield useful lessons about what strategies seem to be effective. In addition, some agencies—such as the recipients of the organized retail theft grant funds distributed by BSCC—may be farther ahead in developing enforcement and prosecution strategies. Accordingly, the Legislature may want to assess whether promising strategies are being captured and shared. For example, it could ask state‑level agencies—including BSCC, CHP, and the Department of Justice—or statewide associations—such as the California District Attorneys Association or the California Retailer’s Association—what venues or systems exist to facilitate capturing and sharing of promising practices.

Are the Laws Robust to Technological Change? Over the longer term, the Legislature may want to monitor whether the laws are robust to technological change. This is particularly relevant to the regulation of online market places to prevent the sale of stolen goods. This is a relatively new area of regulation and one that is likely continuing to evolve as new online platforms or criminal strategies for utilizing existing ones emerge.

Oversight of Key Outcomes

Is Reported Retail Theft Going Down? The primary goal of the law changes discussed above is to reduce retail theft. To determine whether these specific law changes—as opposed to other factors that can affect crime—cause retail theft to go down will likely require a relatively sophisticated academic study. Absent or until such a study is completed, monitoring rates of reported shoplifting and commercial burglary can still provide a helpful indication of whether crime is declining, regardless of cause. However, we caution that the law changes themselves may cause retailers to be more likely to report crime to law enforcement and/or may cause law enforcement to be more likely (or able) to arrest and prosecute people for the affected crimes. To the extent these dynamics occur, they could cause reported crime, arrests, or convictions to increase even if the actual underlying level of crime stays the same or declines. Accordingly, raw crime and arrest data must be interpreted with caution.

Are Clearance Rates Going Up? As discussed above, research suggests that crime can be reduced when the likelihood of apprehension increases. Monitoring burglary clearance rates can give the Legislature a sense of whether the likelihood of apprehension is increasing. However, again, we caution that if retailers become more likely to report crime as a result of the law changes, then clearance rates could go down even if the actual likelihood of apprehension increases.

Are There Unintended Consequences? As with any new policy, unintended consequences can occur. For example, directing increased enforcement resources toward retail theft could cause criminals to shift their focus to other illegal sources of revenue. While data limitations may make it difficult to directly detect such shifts at a statewide level, this is an area where the Legislature could engage representatives of local law enforcement or others who may have insight into crime dynamics. Another potential unintended consequence of these law changes is that they could have disproportionate effects on certain groups of people. For example, increased punishment for adults caught shoplifting could cause organized theft rings to recruit juveniles to shoplift for them under the expectation that they would be less likely to face increased punishments in the juvenile justice system. Accordingly, monitoring for potential disparate impact by age group, race/ethnicity, housing status, substance use disorder, or geographic region could provide the Legislature with greater insight into impacts of the law changes.

How Much Have Criminal Justice System Costs Increased? Many of the law changes increase state and local government costs—primarily by increasing the prison, jail, and probation populations. However, the actual increase in costs will depend on implementation decisions made by various actors. For example, the extent to which prosecutors apply their new sentencing tools in a narrow or broad manner will impact the number of cases affected by the increased punishment. In addition, decisions made by judges—such as whether to sentence people convicted of felonies to jail or prison as opposed to granting probation in lieu of incarceration—will impact system costs. Pinpointing cost increases tied directly to the use of these new enforcement and prosecution tools may be difficult due to both limited data and the challenge of knowing what costs would have been absent these law changes. However, the Legislature can monitor for notable increases in prison, jail, and probation populations. In addition, as the Legislature conducts oversight of implementation, it may uncover information—such as which tools are driving the most use of incarceration—that can yield avenues for further inquiry around cost.

Do the Benefits Outweigh the Costs? As the Legislature gathers answers to the above questions—such as through commissioning studies or engaging in dialogue with practitioners and stakeholders—some sense of the magnitude of benefits, costs and any unintended consequences should start to emerge. At that point, the Legislature will want to consider whether the increases in costs and or unintended consequences of these changes are justified by reductions in the crime rate and/or increases in the clearance rates. In particular, the Legislature may want to scrutinize the use of the most expensive interventions, such as incarceration, to ensure they are reserved for cases where research suggests they could yield a commensurate reduction in crime. For example, since incarceration can be relatively costly for the state or local governments, research suggests that adding time to felony jail or prison sentences is generally less likely to be cost effective than interventions that increase the likelihood of apprehension, such as increasing police presence.

Conclusion

In response to growing concerns, the Legislature and the voters recently approved several law changes intended to reduce retail theft. The potential effects of these law changes are complex and will depend heavily on implementation decisions made by local criminal justice system actors. We outline in this report how the recent law changes expanded the tools available for law enforcement and prosecutors to respond to retail theft, how research suggests these tools could potentially impact crime rates, and provide key questions about implementation and outcomes of these changes for the Legislature to ask as it conducts ongoing oversight of the issue of retail theft.