April 11, 2025

The 2025-26 Budget

SB 678 County Probation Grant Program

Background

Probation Departments Have Key County Felony Supervision Responsibilities. County probation departments conduct investigations to provide presentencing reports to the courts after a conviction, supervise people in the community to ensure they comply with the terms of their supervision, and refer people to programs intended to help them avoid committing new crimes and improve their lives. They perform the following types of county felony supervision:

Mandatory Supervision is the community supervision portion of a split sentence, which is a felony sentence divided between county jail and community supervision.

Post Release Community Supervision (PRCS) is the supervision of certain people in the community (those whose current offense is nonserious and nonviolent) after they have served a felony sentence in state prison. (People whose current offense is serious or violent, as well as certain others, are supervised in the community by state parole agents.)

Felony Probation is the supervision of people in the community which is carried out in lieu of those people serving a felony sentence in prison, jail, or through a split sentence.

Community Supervision Violations Can Lead to Incarceration. People who violate the terms of their county felony supervision can be punished in various ways. People on PRCS and mandatory supervision can be placed in jail for violations. People on felony probation who violate the terms of their supervision can be required to serve the typical term for their crime in prison if they are on probation for a prison-eligible crime. Otherwise, people violating felony probation can be required to serve the typical term for their crime in jail or through a split sentence. People on all forms of county felony supervision can be sent to prison if they commit a new prison-eligible crime.

State Established a Grant Program for County Felony Supervision. Chapter 608 of 2009 (SB 678, Leno)—also known as the Community Corrections Performance Incentives Act of 2009—established a grant program to achieve three primary goals: (1) reduce the rate at which county probation sends people on county felony supervision to state prison, (2) create state savings, and (3) improve public safety. It did this by rewarding counties with a portion of the state savings created for each person on county felony supervision diverted from prison. The number of people diverted was estimated by comparing the rate at which each county actually sent people on county felony supervision to prison in a given year with a historical baseline rate at which they previously did so. If counties sent people at a lower rate than the historical baseline rate, they received a portion of the resulting state savings based on a formula. Examples of how the original formula estimated state savings to be shared with counties are shown in Figure 1. (The original formula applied only to felony probation as the other forms of county felony supervision had not yet been created.) Notably, SB 678 requires counties to spend the funds they receive on probation programs and practices that are evidence-based, meaning research has shown they are effective at reducing re-offending.

Figure 1

Example of Estimated State Savings Under Original

SB 678 Formula

|

County A |

County B |

County C |

|

|

Felony probation population |

5,000 |

10,500 |

5,000 |

|

Baseline |

|||

|

Baseline failure‑to‑prison ratea |

15% |

10% |

1.3% |

|

Baseline failures to prison |

750 |

1,050 |

65 |

|

Actual |

|||

|

Actual failure‑to‑prison rate |

10% |

8.57% |

1.2% |

|

Actual failures to prison |

500 |

900 |

60 |

|

People diverted from prison (baseline ‑ actual) |

250 |

150 |

5 |

|

State Savings Createdb |

$7,250,000 |

$4,350,000 |

$145,000 |

|

aCalculated as the average felony probation failure‑to‑prison rate between 2006 and 2008. bState savings were calculated at about $29,000 per person diverted from prison and parole. |

|||

SB 678 Formula Modified to Account for Sentencing Changes. The SB 678 formula has been frequently modified since it was first implemented in response to various sentencing and policy changes. These include the 2011 public safety realignment, which created the other forms of county felony supervision, among other changes, and Proposition 47 (2014), which reduced various drug and property crimes from felonies to misdemeanors. The modifications to the formula were generally made in an attempt to prevent county grant awards from changing for reasons unrelated to performance. The most recent modification to the formula occurred in 2015-16. (Hereafter, we refer to this version as the modified formula.) The modified formula was put on hold in 2021-22 through 2024-25, again due to concerns that other factors—such as the COVID-19 pandemic—would cause awards to artificially fluctuate. As a result of this hold, counties received a set amount each year irrespective of performance. The state allocated a total of $123.8 million each year from 2021-22 through 2023-24, and $117.1 million in 2024-25. Under current law, the hold will expire and the modified formula would again be used starting in 2025-26.

Governor’s Proposal

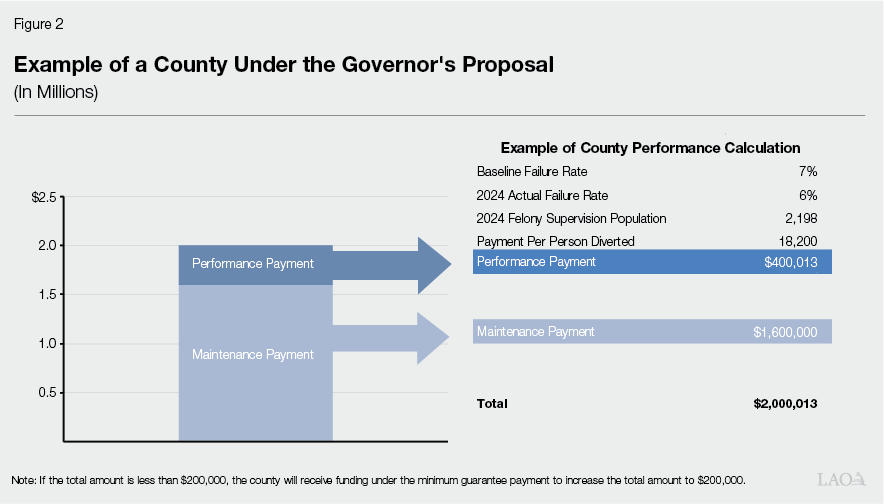

Newly Proposed SB 678 Grant Formula Consisting of Three Payments. The Governor proposes that the modified formula be replaced with a new SB 678 grant formula beginning in 2025-26. The proposed formula has three different payments: (1) a performance payment, (2) a maintenance payment, and (3) a minimum guarantee payment. These payments would determine each county’s total SB 678 grant award. Below, we provide additional details about each of the proposed formula’s payments.

Performance Payment. The performance payment compares a county’s most recent annual county felony supervision failure-to-prison rates with the county’s average failure-to-prison rates in 2021, 2022 and 2023—known as the baseline rates. Each county has a different baseline rate for each of the three county felony supervision populations (mandatory supervision, PRCS, and felony probation). If the failure-to-prison rate for a specific county felony supervision population is lower than the baseline rate, the county receives a share of state savings per person diverted—similar to the original SB 678 formula. The performance payment is intended to incentivize reductions in the county felony supervision failure-to-prison rates.

Maintenance Payment. Under the maintenance payment, counties would receive a set amount irrespective of their performance. This would total $103.7 million in 2025-26. Through this payment, each county would receive about 89 percent of what it received in 2024-25, irrespective of the county’s performance. The maintenance payment is intended to provide counties with stable funding for evidence-based practices.

Minimum Guarantee Payment. If the total amount that a county receives under the performance and maintenance payments is less than $200,000, the county will receive funding under the minimum guarantee payment to increase the total amount to $200,000 irrespective of their performance.

The administration indicates that the proposed formula would provide a total of $127.5 million in grant awards in 2025-26. This is $10.4 million (8.9 percent) more than the 2024-25 amount. Figure 2 provides an example of how a county grant award would be calculated.

New Methodology for Calculating State Savings Per Person Diverted. The Governor’s proposed formula includes a new methodology for calculating the amount the state is estimated to save for each person diverted from state prison and parole. This new methodology would affect award amounts under the performance payment of the proposed formula. Specifically, counties would receive 25 percent of the average of the state’s average annual per person cost for prison and parole, or about $18,200 per person diverted. The administration indicates that the costs would be updated annually.

Includes a Funding Growth Adjustment. Under the proposed formula, the amount of funding allocated through the maintenance payment grows annually starting in 2026-27. The growth adjustment would be based on the growth of 2011 realignment revenue provided to the counties. Because the 2011 realignment shifted responsibility for various correctional populations from the state to the counties, it also shifted a portion of sales tax revenue to counties to support this workload. Accordingly, the SB 678 maintenance payment would grow annually at a similar rate as sales tax revenue. The administration indicates a growth adjustment is necessary to account for inflation costs over time.

Assessment

Changes to the Modified Formula Are Warranted. Without a change, SB 678 grant awards will be calculated using the modified formula beginning in 2025-26 due to the expiration of the hold currently in place. In our publication, Achieving the Goals of the SB 678 County Probation Grant Program, we found that the modified formula may not be effectively achieving the goals of the program. This is because (1) the effects of the formula on the prison population, crime, and state savings are difficult to distinguish from other policy changes; (2) components of the modified formula do not align with the original goals of the program; and (3) it is unclear whether counties are actually implementing evidence-based practices, which is important for achieving the goal of improving public safety. Accordingly, we concur with the administration that a change is needed. However, the administration’s proposed formula has several notable drawbacks described below.

Proposed Baseline for Performance Payment Is Problematic. The administration’s proposal to measure county performance against baselines using failure-to-prison rates from 2021 through 2023 has a key drawback. Specifically, including 2021 data is problematic because failure-to-prison rates during 2021 were artificially low due to factors related to the COVID-19 pandemic rather than county performance. For example, because state prisons were not admitting people for a portion of 2021 to prevent the spread of the virus, some people who should have been counted in failure-to-prison rates were not. This could have the effect of making it more difficult for counties to demonstrate improvement relative to the proposed baselines, artificially lowering grant awards through the performance payment. Additionally, the administration indicates it does not anticipate proposing future changes to the baseline. This means it would not be adjusted for policy changes such as Proposition 36 (2024). Proposition 36 increased punishment for various theft and drug crimes, which could make it easier for people to fail-to-prison while on county felony supervision. In other words, it might make future county failure-to-prison rates high for reasons that are outside of the control of the probation departments, again artificially lowering grant awards through the performance payment. These factors could lower their funding for evidence-based practices—which could harm public safety, undermining a key goal of the SB 678 grant program.

Methodology for Estimating State Savings Per Person Diverted Has a Few Drawbacks. The methodology proposed by the administration to estimate the amount the state saves when people are diverted from prison—and by extension the amount counties receive through the performance payment—has the following drawbacks:

Uses Average Rather Than Marginal Cost. The proposed formula uses the state’s average cost to house a person in state prison to estimate the amount the state saves when such people are diverted. We find that using the marginal cost is a more reasonable approach. The marginal cost better captures how much the state saves when one fewer person enters prison, such as savings on food, clothing, and medical care. In contrast, the average cost includes costs that often are only saved when entire facilities are closed, such as facility or correctional staffing costs. We estimate the prison marginal cost to be about $20,000 per person per year, whereas the administration estimates the average cost to be about $128,400 per person per year. Similarly, the administration uses the average cost to supervise someone on parole—about $17,000 per person per year, while we estimate the parole marginal cost to be about $11,000 per person per year. As a result, this part of the proposed methodology would overestimate state savings.

Assumes All People Are Released to Parole. The proposed formula also assumes that the state saves parole-related costs every time someone is diverted from prison. However, this is not the case because generally only people with current serious or violent offenses can be placed on parole. Historically, only about half of the people released from prison have been released to parole and the other half to PRCS. As a result, this part of the proposed methodology would overestimate state savings.

No Adjustment for Amount of Time in Prison or on Parole. The proposed formula does not take into account the amount of time people serve in prison or on parole. For example, there is no adjustment for the fact that people who are ultimately released to parole serve, on average, nearly six years in prison and around two years on parole. As a result, this part of the proposed methodology would underestimate state savings.

On net, we find that the administration’s methodology underestimates the amount of state savings for each person diverted and—since this estimate determines the amount of performance payments—it has the effect of reducing counties’ incentive to divert people from prison. Specifically, after adjusting for the issues discussed above, we estimate that 25 percent of the amount the state saves for each person diverted is about $21,000—or $2,800 higher than under the administration’s proposed formula.

Aspects of Maintenance Payment Are Problematic. We find that aspects of the maintenance payment are problematic for several reasons.

Unclear Rationale for Amount. First, we find that the rationale for the amount of the maintenance payment is unclear. The maintenance payment ($103.7 million) reflects a roughly $20.1 million reduction (16 percent) from the amount counties received in 2023-24 when the formula was placed on hold. In 2023-24, each county received their highest SB 678 grant award from the prior three fiscal years (2018-19, 2019-20, or 2020-21) due to concerns that grant awards would fluctuate for reasons unrelated to performance. It is not clear why this amount is the most reasonable to base funding on—particularly given that it makes up over 80 percent of counties’ total grant awards under the proposed formula.

Does Not Support Program Goals. Second, it is not clear which specific SB 678 goal the maintenance payment is connected to or what incentive counties have to achieving a specific goal with these funds. For example, the maintenance payments to counties are not connected to actual state savings, any specific reduction to prison commitments, or any specific evidence-based practice shown to yield positive results. As a result, the maintenance payment does not support the original goals of the program.

Growth Adjustment Not Tied to Actual Growth in County Costs and Would Have Less Oversight. We also find that the maintenance payment’s growth adjustment is problematic. First, it is not tied to increases in county supervision costs, rather it is tied to growth in realignment revenues, which has no bearing on county costs. This could provide more funding to county probation departments than necessary to run effective and efficient county supervision programs in some years and less funding than necessary in other years. Second, the maintenance payment’s growth adjustment reduces legislative oversight. This is because it would provide additional funding to counties without the administration having to directly request it. This is particularly problematic since the program would no longer be structured in a way to ensure it generates net state savings.

Minimum Guarantee Disconnects Actual State Savings From Performance. The minimum guarantee of $200,000 to counties undermines the goal of generating state savings and reducing prison commitments. This is because a county could continue to receive SB 678 funds despite not diverting anyone from prison. This disconnects actual state savings from performance, thereby providing little incentive for improvement for some counties with lower performance.

No Proposed Changes to Oversight. While counties are required to use SB 678 funds on evidence-based practices, there are no required audits or assessments of the evidence-based practices counties are using. This makes it difficult for the Legislature to assess whether counties that report funding evidence-based practices and programs are in fact doing so. This is concerning given one of the goals of the program is to improve public safety by incentivizing the use of these practices.

Recommendations

Below, we recommend changes to the Governor’s proposed SB 678 grant formula that would help address the issues we identified above. These changes would result in a system that would better achieve the stated goals of the program. We note that if all of our recommended changes are adopted, it would result in the formula described in our publication, Achieving the Goals of the SB 678 County Probation Grant Program.

Modify Performance Payment

We concur with the administration that providing payments based on performance is an important way to achieve the original goals of the SB 678 grant program. The Governor’s proposal gets the state closer to achieving those goals. However, we recommend the following changes to the Governor’s proposed performance payment to address the concerns we identified above. We find that these steps would allow the state to better assess the actual state savings generated, preserve the formula’s fiscal incentives, and continue sharing state savings with counties at a level the Legislature finds appropriate.

Use 2022 and 2023 as the New Baseline and Consider Future Updates. We recommend that the new baseline be based on years that fully reflect all of the policy changes that have impacted county felony supervision failure-to-prison rates. As noted above, 2021 failure-to-prison rates were likely artificially low due to COVID-19. By excluding 2021, the baseline rates would be less impacted by COVID-19. This would make estimates of performance more accurate and potentially more achievable for some counties. Although making this change might only result in modest changes to the statewide performance payment, compared to the Governor’s proposal, it may have a larger impact on smaller, more rural, counties that are more affected by small changes in failure-to-prison rates. The Legislature could also consider updating the baseline in the future after Proposition 36 is fully implemented to the extent it—or other significant changes—impact county performance.

Update State Savings Methodology. We recommend making three changes to the Governor’s proposed methodology: (1) use the marginal costs to incarcerate someone in state prison and supervise someone on state parole, (2) adjust the formula to account for the fact that not everyone is released to parole, and (3) adjust for the average amount of time people spend in prison and parole. Under this methodology, the estimated amount the state saves for each person diverted from prison would be about $84,000.

Consider What Portion of State Savings to Transfer to Counties. The Legislature could consider adopting the Governor’s proposal that 25 percent of state savings be transferred to counties. If our method for estimating state savings was used, this would increase the amount allocated to counties through the performance payment by a few million dollars. However, the Legislature could choose a higher or lower amount. A higher percentage provides greater incentive and resources to the counties to reduce prison commitments, but reduces the amount of state savings achieved. A lower percentage does the opposite. Determining the amount ultimately depends on how the Legislature weighs the goal of achieving state savings versus reducing prison commitments.

Modify Maintenance Payment

If the state only provides funding based on performance, then SB 678 grant awards would likely decline significantly. Such a reduction in funding could be problematic if it results in counties spending less on evidence-based practices that successfully reduced prison commitments. Accordingly, we concur with the administration that some funding similar to the proposed maintenance payment is necessary. However, we recommend an alternative maintenance payment that pays only for specific evidence-based practices that will improve public safety and does so in ways that are more likely to generate state savings—two of the key goals of the original program. As we discuss below, this will likely take time. If the Legislature would prefer to implement a more permanent maintenance payment immediately, we also outline simple changes the Legislature could make to the Governor’s proposed maintenance payment that would address some—though not all—of our concerns.

Key Steps for Implementation of Maintenance Payment for Specific Evidence-Based Practices.

Identify Practices to Be Funded. We recommend that a group of experts, be convened to identify evidence-based practices that are likely to reduce the number of prison commitments from the county felony supervision population. Only these practices would be eligible for funding through this portion of the grant. We recommend tasking the Board of State and Community Corrections (BSCC) with convening this group.

Estimate Level of Savings and Award Amount for Each Evidence-Based Practice. We recommend directing BSCC to collaborate with experts to estimate the savings likely to be created by each evidence-based practice identified in the previous step. The Legislature could then determine what portion of the cost of the practice would be covered through the grant by weighing its preference for expanding evidence-based practices against its interest in creating state savings. If the cost of these practices increases in future years, the administration could request that the Legislature increase the amount of funding available for implementing them accordingly.

Establish Total Amount for Grant and Determine Allocation. The Legislature would need to establish the total amount it is willing to spend on additional grants for specific evidence-based practices and determine a county allocation formula. This amount could be set such that the two portions of the grant would be roughly similar to the amount provided in recent years or proposed by the Governor. One option for a formula allocation would be to base each county’s maximum share of funds on the overall county felony supervision population. A county would then receive an award for each evidence-based practice it uses, up to this maximum.

Establish Oversight for Use of Evidence-Based Practices. We recommend requiring BSCC, which is responsible for promoting effective state and local corrections efforts, to have an oversight role of the program. Specifically, BSCC would be required to audit counties to ensure compliance with the selected evidence-based practices and to ensure outcomes at the local level are regularly evaluated. The BSCC budget would have to increase to account for its new duties related to the grant. We estimate that this could require a few million dollars annually. We note that this amount could be paid from the state savings created by the program.

Provide Interim Funding While Maintenance Payment for Specific Evidence-Based Practices Is Being Implemented. Because carrying out the steps above will take time, we recommend, for at least two years, providing the maintenance payment as proposed by the Governor, with the simple modifications we describe in the next section.

Alternatively, Consider Simple Modifications to Governor’s Proposed Maintenance Payment. If the Legislature would prefer to implement a more permanent maintenance payment immediately, we recommend adopting the Governor’s proposed maintenance payment with the two following revisions.

Reject Proposed Growth Adjustment. Given that the growth adjustment is not based on actual increases in county costs and would result in less oversight in this area, we recommend the Legislature reject it. To the extent SB 678 grant awards are no longer keeping up with county costs to operate effective and efficient supervision programs, the administration could request increases based on actual costs in the future.

Ensure Counties Use Evidence-Based Practices. Given that the Governor’s proposal does not include changes to oversight of the program, we recommend tasking BSCC with ensuring counties use SB 678 grant awards for evidence-based practices. Counties found to be out of compliance could be provided with technical assistance to make the changes or risk losing SB 678 grant awards. The BSCC budget would have to increase to account for its new duties related to the grant. We estimate that this could require a few million dollars annually. This could be paid for by correspondingly reducing the amount available for grants.

Reject Minimum Guarantee Payment

Minimum Guarantee Payment Disconnects Awards From Performance. Because we find that the minimum guarantee payment disconnects awards from performance, we recommend rejecting this payment. This would maintain the incentive for improvement among counties with lower performance.