LAO Contact

- Edgar Cabral

- Deputy Legislative Analyst: K-12 Education

- Michael Alferes

- Attendance Recovery and Instructional Continuity

- Jackie Barocio

- Education Workforce

- Education Technology

- Sara Cortez

- School Nutrition

- Kenneth Kapphahn

- The Minimum Guarantee

- K-12 Spending Plan

February 15, 2024

The 2024‑25 Budget

Proposition 98 and K‑12 Education

- Executive Summary

- Introduction

- The Minimum Guarantee

- K‑12 Spending Plan

- School Nutrition

- Education Workforce

- Attendance Recovery and Instructional Continuity

- Education Technology

Executive Summary

In this report, we assess the architecture of the Governor’s overall Proposition 98 budget and analyze his major proposals for K‑12 education.

Overall Proposition 98 Budget

$13.7 Billion in Solutions and Reductions Affecting Schools. Proposition 98 (1988) sets aside a minimum amount of funding for schools (and community colleges) based upon a set of constitutional formulas. Due to reductions in state revenue, the Governor’s budget estimates this funding requirement is down significantly over the 2022‑23 through 2024‑25 period. To align spending with these lower estimates, the Governor proposes $13.7 billion in reductions and other solutions affecting schools. The largest proposal is a funding maneuver that would “accrue” $7.1 billion in previous payments to schools (and $910 million in previous payments to community colleges) to future years. Under this proposal, schools would retain these payments but the state would take the associated costs off its books for several years. The other significant proposal is a $4.9 billion withdrawal from the Proposition 98 Reserve to cover school spending in 2023‑24 and 2024‑25. The budget also recognizes savings from lower student attendance ($1.2 billion) and proposes a one‑time reduction to preschool funding that would otherwise go unused ($446 million).

$1.4 Billion in New Proposition 98 K‑12 Spending Proposals. Of this amount, $784 million is for ongoing increases and $599 million is for one‑time activities. The largest ongoing proposal is to cover a 0.76 percent cost‑of‑living adjustment (COLA) for existing programs and the largest one‑time proposal is to provide additional funding for zero‑emission school buses.

Overall Messages

Recommend Alternative Approach That Prioritizes Core Programs and Budget Stability. The Governor’s budget avoids immediate reductions to school programs but relies heavily on solutions that shift expenditures into the future. Specifically, the budget would worsen future state budget deficits (through the funding maneuver) and set up future shortfalls in ongoing school programs (by using reserves and other one‑time funds to cover ongoing costs). This approach positions the state poorly—making spending commitments the state would have difficulty sustaining and setting up more difficult choices next year. We recommend an alternative approach that prioritizes core school programs and also promotes budget stability and aligns school spending with the funding available under Proposition 98.

Plan for Further Decreases in Proposition 98 Funding by June. State revenue collections have been notably weak since the release of the Governor’s budget. Based upon our most recent forecast (released in February), we estimate that funding for schools under Proposition 98 is $5.2 billion lower than the Governor’s budget level in 2023‑24 and $2.5 billion lower in 2024‑25. We recommend the Legislature use the coming months to establish its priorities and examine the additional reductions and solutions that would be needed to address these decreases.

Significant Concerns With Proposed Funding Maneuver, Recommend Rejecting. Under this proposal, the state would be using its cash resources to finance payments to schools and creating an obligation to recognize the underlying budgetary cost in the future. In addition to worsening future budget deficits, the proposal sets a problematic precedent by decoupling payments to schools and state recognition of costs for an extended period. As an alternative, we recommend using Proposition 98 Reserve withdrawals to cover the costs of these payments.

Proposed COLA Adds to Ongoing Program Shortfall, Recommend Rejecting. The 2023‑24 enacted budget relied upon nearly $1.6 billion in one‑time funds to pay for ongoing school programs, and the proposed COLA in the Governor’s budget would increase this shortfall to $2.2 billion in 2024‑25. Given that the current Proposition 98 funding level cannot even support the cost of existing programs, we recommend rejecting the proposed COLA.

Other Ongoing and One‑Time Increases Unaffordable, Recommend Rejecting. We recommend rejecting virtually all of the other increases in the Governor’s budget. These proposals do not seem urgent enough to justify their additional costs amidst tight fiscal times.

Explore Additional Solutions. We recommend the Legislature consider these options:

- Reductions to Unallocated Grants. We estimate the state has about $4.5 billion in funding set aside for competitive grants that have not yet been awarded. Rescinding some of these grants would generate one‑time savings.

- Temporary Reductions to Certain Programs. The state has a few ongoing programs for which districts have significant amounts of unspent carryover funding. The state could temporarily reduce funding for these programs with the expectation that districts would support the underlying activities with unspent local funds.

- Ongoing Reductions to Certain Programs. The state has provided significant increases for the Expanded Learning Opportunities Program, State Preschool, school nutrition, school transportation, and transitional kindergarten staffing in recent years. The Legislature could restructure these programs to reduce their costs.

- Ongoing Reductions to Antiquated Add‑Ons. The state could obtain savings and reduce funding disparities among districts by phasing out funding that it allocates to districts based on programs they operated decades ago.

Messages on Specific Programs

In addition to our overall message on spending, we discuss several other issues that are either not specifically connected to budget proposals or have no associated costs.

School Nutrition. Given recent changes in federal regulations, we recommend the Legislature remove the mandatory participation requirement for schools newly eligible for the federal Community Eligibility Provision option. We also provide several options the Legislature may want to consider for containing future cost growth of the school nutrition program.

Educator Workforce. The Legislature may want to more carefully consider the trade‑offs associated with the proposed new authorization for teaching arts in elementary schools. The proposal may make it easier for schools to hire arts teachers, but these teachers may not be as prepared to teach in an elementary and early childhood setting.

Attendance Recovery and Instructional Continuity. Although the Governor’s budget does not include any funding associated with these proposed new programs, they likely would result in ongoing cost increases. If the Legislature is interested in implementing these programs, we recommend delaying them for at least one year. We also identify several associated implementation issues for the Legislature to consider.

Education Technology. Instead of providing additional Proposition 98 funding, we recommend the Legislature maximize the use of grantee reserves and carryover funds to offset operational costs of the California College Guidance Initiative and K‑12 High Speed Network.

Introduction

In this report, we analyze the Governor’s Proposition 98 proposals in K‑12 education. The first section analyzes the administration’s estimates of the Proposition 98 minimum guarantee and explains how the guarantee is likely to change in the coming months. The second section describes the Governor’s plan for allocating Proposition 98 funding to schools, assesses the merits of this approach, and provides our recommendations for the Legislature to consider. The four remaining sections of this report examine the Governor’s major proposals involving K‑12 education. Specifically, we analyze his proposals for (1) school nutrition, (2) the education workforce, (3) attendance recovery and instructional continuity, and (4) education technology.

The Minimum Guarantee

Proposition 98 (1988) established a minimum funding requirement for schools and community colleges commonly known as the minimum guarantee. In this section, we (1) provide background on the guarantee, (2) analyze the administration’s estimates of the guarantee, and (3) explain how the guarantee is likely to change in the coming months.

Background on the Guarantee

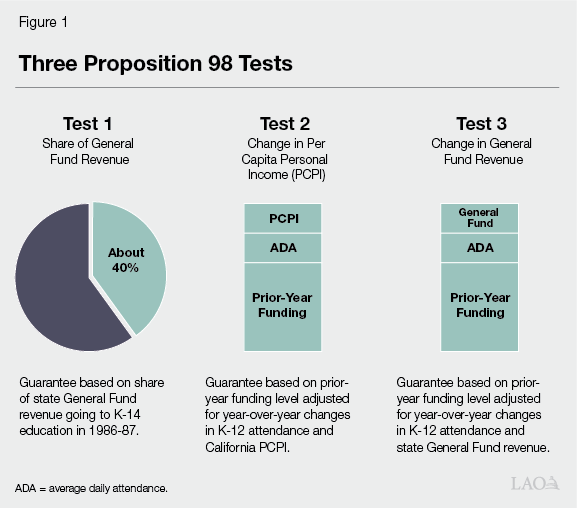

Minimum Guarantee Depends on Various Inputs and Formulas. The California Constitution sets forth three main tests for calculating the Proposition 98 minimum guarantee. Each test takes into account certain inputs, including General Fund revenue, per capita personal income, and student attendance (Figure 1). Test 1 links school funding to a minimum share of General Fund revenue, whereas Test 2 and Test 3 build upon the amount of funding provided the previous year. The Constitution sets forth rules for comparing the tests, with one of the tests becoming operative and used for calculating the minimum guarantee that year. Although the state can provide more funding than required, it usually funds at or near the guarantee. With a two‑thirds vote of each house of the Legislature, the state can suspend the guarantee and provide less funding than the formulas require that year. The guarantee consists of state General Fund and local property tax revenue.

At Key Points, the State Recalculates the Minimum Guarantee. The state makes an initial estimate of the guarantee when it enacts the annual budget, but this estimate typically changes as the state updates the relevant Proposition 98 inputs. Specifically, the state recalculates the guarantee at the end of the year based on revised estimates of these inputs, followed by a second recalculation at the end of the following year. When the guarantee exceeds the initial budget estimate, the state must make a one‑time payment to “settle up” for the difference. If the guarantee drops, the state can reduce spending to the lower guarantee. After making these revisions, the state finalizes its calculation of the guarantee through an annual process called “certification.” Certification involves the publication of the underlying Proposition 98 inputs and a period of public review. The most recently certified year is 2021‑22.

Proposition 98 Reserve Sets Aside Funding for Tighter Times. Proposition 2 (2014) created a state reserve specifically for schools and community colleges—the Public School System Stabilization Account (Proposition 98 Reserve). The Constitution generally requires the state to deposit Proposition 98 funding into this reserve when the state receives high levels of capital gains revenue and the minimum guarantee is growing relatively quickly. The Constitution also requires the state to withdraw funding from the reserve under certain conditions—generally when funding is growing slowly relative to inflation and student attendance. If the Governor declares a budget emergency, the Legislature can make discretionary withdrawals. Unlike other state reserve accounts, the Proposition 98 Reserve is available only to supplement the funding schools and community colleges receive under Proposition 98.

Proposition 98 Reserve Linked With Cap on School Districts’ Local Reserves. A state law enacted in 2014 and modified in 2017 caps school district reserves after the Proposition 98 Reserve reaches a certain threshold. Specifically, the cap applies if the funds in the Proposition 98 Reserve in the previous year exceeded 3 percent of the Proposition 98 funding allocated to schools that year. When the cap is operative, medium and large districts (those with more than 2,500 students) must limit their reserves to 10 percent of their annual expenditures. Smaller districts are exempt. The law also exempts reserves that are legally restricted to specific activities and reserves designated for specific purposes by a district’s governing board. In addition, a district can receive an exemption from its county office of education (COE) for up to two consecutive years. The cap became operative for the first time in 2022‑23 and remains operative in 2023‑24.

Administration’s Estimates of the Guarantee

Major Downward Revision to Revenues in 2022‑23. The state receives most of its revenue from the personal income tax, corporation tax, and sales tax. The state ordinarily receives these revenues on a predictable schedule and adjusts its future revenue estimates based on trends in the tax collection data. To conform with federal action, the state delayed the deadline for some personal income and corporation tax payments that normally would have been due in the spring and summer of 2023 until November 16, 2023. The delay obscured significant weakness in state revenue collections that otherwise would have been evident earlier. Specifically, the delayed payments show that state tax collections for 2022‑23 were nearly $26 billion lower than the levels the state estimated in June 2023.

Proposition 98 Guarantee Revised Down Substantially in 2022‑23. Compared with the estimates from June 2023, the administration revises its estimate of the guarantee down nearly $9.1 billion for 2022‑23 (Figure 2). Test 1 is operative, meaning the guarantee increases or decreases nearly 40 cents for each dollar of higher or lower General Fund revenue. In Test 1 years, changes in local property tax revenue also have dollar‑for‑dollar effects on the guarantee. The reduction in the guarantee primarily reflects the significant drop in General Fund revenue, but is offset slightly by a small increase in property tax revenue. This downward revision is the largest reduction to the guarantee in a prior year since the passage of Proposition 98 in 1988. By contrast, previous downward revisions to the prior‑year guarantee have never been larger than a couple hundred million dollars.

Figure 2

Tracking Changes in the Prior‑ and Current‑Year Proposition 98 Guarantee

(In Millions)

|

2022‑23 |

2023‑24 |

||||||

|

June 2023 Estimate |

January 2024 Estimate |

Change |

June 2023 Estimate |

January 2024 Estimate |

Change |

||

|

General Fund |

$78,117 |

$68,563 |

‑$9,554 |

$77,457 |

$74,633 |

‑$2,824 |

|

|

Local property tax |

29,241 |

29,742 |

501 |

30,854 |

30,953 |

99 |

|

|

Totals |

$107,359 |

$98,306 |

‑$9,053 |

$108,312 |

$105,586 |

‑$2,725 |

|

|

General Fund tax revenue |

$204,533 |

$178,952 |

‑$25,581 |

$201,213 |

$193,185 |

‑$8,028 |

|

Moderate Reduction in the Guarantee in 2023‑24. The administration anticipates a relatively rapid recovery for state revenues in 2023‑24. Specifically, the Governor’s budget assumes an 8 percent increase in General Fund revenue relative to the lower 2022‑23 level, including a 12 percent increase in personal income tax receipts. Under this assumption, state revenues would be moderately below the June 2023 estimate and the Proposition 98 guarantee would be $2.7 billion (2.5 percent) below the enacted budget level. Test 1 remains operative in 2023‑24, with the change in the guarantee reflecting the decrease in General Fund revenue and a small offsetting increase in property tax revenue.

Moderate Growth in Guarantee in 2024‑25. The administration estimates the guarantee is $109.1 billion in 2024‑25, an increase of $3.5 billion (3.3 percent) over the revised 2023‑24 level (Figure 3). Test 1 is operative in 2024‑25, with modest increases in General Fund revenue and local property tax revenue both contributing to growth in the guarantee. Nearly half of the increase, however, is due to two special adjustments. First, the state adjusts the guarantee up by more than $930 million to account for the arts education program established by Proposition 28 (2022). Second, it makes a further upward adjustment of more than $630 million to account for the continued expansion of eligibility for transitional kindergarten (TK). (In 2022‑23, the state began implementing plan to make TK available to all four‑year old children over a four‑year period. As part of the plan, the state is adjusting the guarantee upward for the additional students enrolling in the program each year.) Mechanically, the state implements these two adjustments by increasing the minimum share of General Fund revenue reserved for schools under Test 1 from 38.6 percent in 2023‑24 to 39.5 percent in 2024‑25.

Figure 3

Proposition 98 Key Inputs and Outcomes Under

Governor’s Budget

(Dollars in Millions)

|

2022‑23 |

2023‑24 |

2024‑25 |

|

|

Minimum Guarantee |

|||

|

General Fund |

$68,563 |

$74,633 |

$76,894a |

|

Local property tax |

29,742 |

30,953 |

32,185 |

|

Totals |

$98,306 |

$105,586 |

$109,080 |

|

Change From Prior Year |

|||

|

General Fund |

‑$15,190 |

$6,070 |

$2,261 |

|

Percent change |

‑18.1% |

8.9% |

3.0% |

|

Local property tax |

$2,942 |

$1,211 |

$1,232 |

|

Percent change |

11.0% |

4.1% |

4.0% |

|

Total guarantee |

‑$12,248 |

$7,281 |

$3,493 |

|

Percent change |

‑11.1% |

7.4% |

3.3% |

|

General Fund Tax Revenueb |

$178,952 |

$193,185 |

$194,941 |

|

Growth Rates |

|||

|

K‑12 average daily attendance |

0.9% |

0.1% |

‑0.03% |

|

Per capita personal income (Test 2) |

7.6 |

4.4 |

4.8 |

|

Per capita General Fund (Test 3)c |

‑17.9 |

8.6 |

1.4 |

|

Operative Test |

1 |

1 |

1 |

|

aIncludes adjustment for arts education funding under Proposition 28 (2022). bExcludes nontax revenues and transfers, which do not affect the calculation of the guarantee. cAs set forth in the State Constitution, reflects change in per capita General Fund plus 0.5 percent. |

|||

|

Note: No maintenance factor is created or paid over the period. |

|||

Moderate Growth in Property Tax Revenue Anticipated. The most important factor affecting local property tax revenue is the rate of growth in assessed property values. Three main factors drive this growth: (1) construction of new properties, (2) sales of existing properties (and their subsequent reassessment to market value), and (3) the annual 2 percent adjustment in the assessed value of all other properties. The administration estimates assessed values will grow 5.1 percent in 2023‑24 and 4.7 percent in 2024‑25. This growth assumption is somewhat below the historical average of about 5.5 percent. The administration also anticipates that some smaller property tax components will grow more slowly. Accounting for all of these factors, the overall increase in local property tax revenue is about 4 percent in each year.

Guarantee Estimated to Grow Slowly in 2025‑26. Under the administration’s multiyear forecast, the Proposition 98 guarantee would grow to $111.9 billion in 2025‑26, an increase of $2.8 billion (2.6 percent) from the 2024‑25 level. This relatively small increase builds upon underlying assumptions of minimal growth in General Fund revenue (0.5 percent) and moderate growth in property tax revenue (4.3 percent). Approximately $1.1 billion of this increase in the guarantee is attributable to an adjustment for TK.

Assessing Estimates of the Guarantee

State Tax Collections Through January Have Been Weak. Whereas the Governor’s budget anticipates a relatively strong rebound in General Fund revenue for 2023‑24, state tax collections through January point to continuing weakness. Tax receipts from regular income tax withholding (the largest portion of the personal income tax) came in $1 billion (11 percent) below the estimates in the Governor’s budget. Receipts from the quarterly estimated payments (the other major contributor to personal income tax revenue) were even worse, coming in $3 billion (27 percent) below the Governor’s budget estimate. The state experienced additional weakness in its two other major revenue sources, with corporation tax payments significantly below projections and sales tax revenue slightly below projections. Consistent with these trends, economic indicators that are important for state revenue collections also have remained weak. For example, investment in California startups and technology companies remains depressed, and relatively few California companies are going public (selling stock to public investors for the first time).

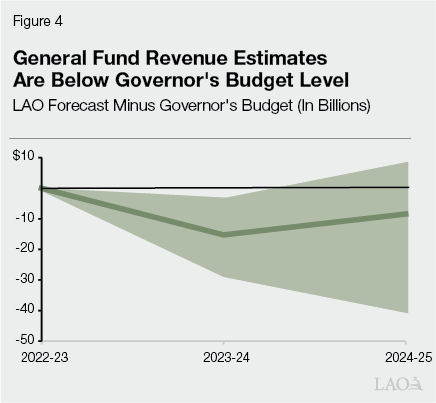

Our February General Fund Revenue Estimates Are Well Below the Governor’s Budget Level. Based on the recent tax collection data, we see a high level of downside risk to the revenue estimates in the Governor’s budget. Specifically, our updated estimate of General Fund revenue (released in February) is $15.3 billion lower than the administration anticipates in 2023‑24 and $8.4 billion lower in 2024‑25. (Across both years, these estimates are $8.4 billion lower than the estimates from our December outlook.) As Figure 4 shows, uncertainty remains for both years and final tax receipts could be higher or lower than we anticipate. Despite this uncertainty, our assessment of the most plausible scenarios (represented by the shaded area in the figure) indicates a low probability that revenues approach the levels in the Governor’s budget.

Our Local Property Tax Estimates Are Slightly Above the Governor’s Budget Level. Whereas our estimates of General Fund revenue are well below the levels in the Governor’s budget, our estimates of property tax revenue are somewhat higher. Specifically, the estimates from our December outlook are $590 million higher in 2023‑24 and $682 million higher in 2024‑25. Approximately one‑third of this difference is due to our higher estimates of growth in assessed property values, another one‑third is due to our higher estimates of supplemental taxes (taxes levied on properties sold during the year), and the remaining one‑third is due to various differences in several smaller property tax components. Preliminary data suggest that property tax revenues are tracking closer to our higher estimates. Most notably, recent data from the Board of Equalization show that assessed property values grew nearly 6.7 percent in 2023‑24, compared with the estimate of 5.1 percent in the Governor’s budget.

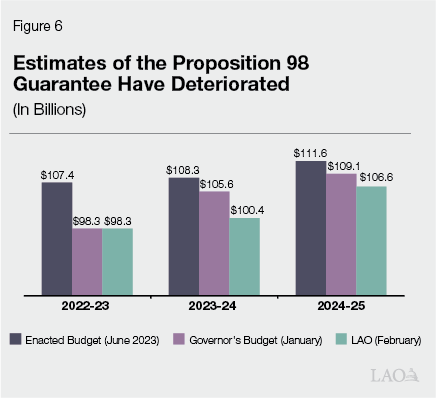

Our Estimates of the Guarantee Are $7.7 Billion Below the Governor’s Budget Level. In Test 1 years like 2023‑24 and 2024‑25, changes in General Fund revenue and local property tax revenue both have direct effects on the Proposition 98 guarantee. Specifically, our lower General Fund revenue estimates reduce the guarantee by nearly 40 cents for each dollar of lower revenue. Increases in local property tax, however, increase the Proposition 98 guarantee on a dollar‑for‑dollar basis. Accounting for our February estimates of General Fund revenue and our December 2023 estimates of local property revenue, we estimate the Proposition 98 guarantee is $7.7 billion lower than the Governor’s budget level over the period. Specifically, our estimates are $5.2 billion lower in 2023‑24 and $2.5 billion lower in 2024‑25 (Figure 5). For 2022‑23, our estimates are unchanged from the Governor’s budget level. As Figure 6 shows, our estimates of the guarantee represent even steeper reductions when measured against the levels the state anticipated in June 2023.

Figure 5

LAO Estimates of Proposition 98 Guarantee Below Governor’s Budget Estimates

(In Millions)

|

2022‑23 |

2023‑24 |

2024‑25 |

Three‑Year Totals |

|

|

Governor’s January Budget |

||||

|

General Fund |

$68,563 |

$74,633 |

$76,894 |

$220,091 |

|

Local property tax |

29,742 |

30,953 |

32,185 |

92,881 |

|

Totals |

$98,306 |

$105,586 |

$109,080 |

$312,972 |

|

LAO February Estimates |

||||

|

General Fund |

$68,563 |

$68,815 |

$73,702 |

$211,081 |

|

Local property tax |

29,742 |

31,543 |

32,867 |

94,153 |

|

Totals |

$98,306 |

$100,358 |

$106,570 |

$305,234 |

|

Change From Governor’s Budget |

||||

|

General Fund |

— |

‑$5,818 |

‑$3,192 |

‑$9,010 |

|

Local property tax |

— |

590 |

682 |

1,272 |

|

Totals |

— |

‑$5,228 |

‑$2,510 |

‑$7,738 |

K‑12 Spending Plan

In this section, we analyze the Governor’s plan for allocating Proposition 98 funding to schools. First, we describe the Governor’s overall approach and review the major spending‑related solutions and proposed increases. Next, we assess the merits of this approach and analyze the most significant proposals. Finally, we provide our recommendations for the Legislature to consider. In contrast to most previous years, the largest proposal in the Governor’s K‑12 plan has significant implications for the rest of the state budget. The nearby box summarizes the overall condition of the state budget to provide context for this proposal. (We analyze proposals affecting community colleges separately in a forthcoming report.)

Overall Condition of the State Budget

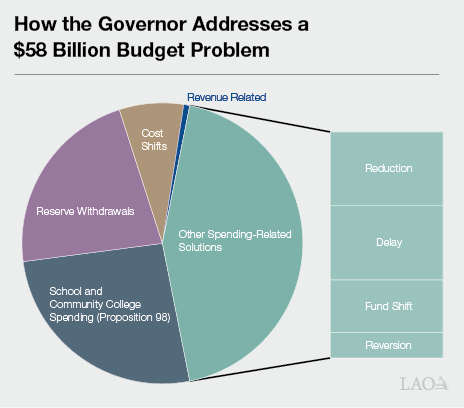

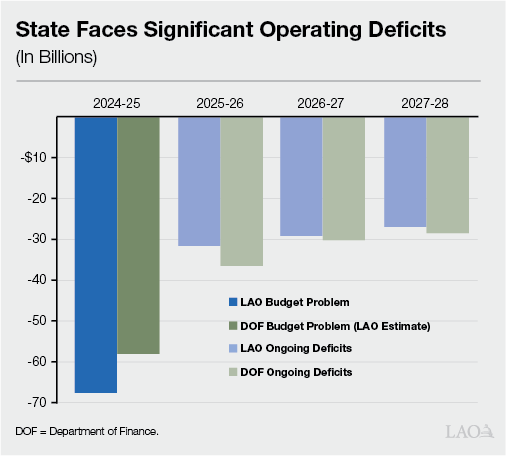

State Facing Serious Budget Problem. A budget problem arises when the resources for an upcoming budget are insufficient to cover the costs of currently authorized services. As we explain in The 2024‑25 Budget: Overview of the Governor’s Budget, we estimate that the Governor had to solve a budget problem totaling $58 billion. The figure below shows the actions the Governor proposes to address the problem. The largest set of solutions are spending related and include a mix of outright reductions, expenditure delays, shifts of costs from the General Fund to other funds and future years, and the recapture of unspent funds (reversions). These solutions are broad‑based and affect nearly all areas of the budget. The Governor also proposes withdrawing funds from state reserve accounts and reducing school and community college spending to the constitutional minimum level.

Large Operating Deficits Anticipated Over the Next Several Years. Although the Governor proposes a number of spending‑related solutions, the budget is likely unsustainable moving forward. As the figure below shows, both our office and the Department of Finance anticipate deficits of roughly $30 billion per year beginning in 2025‑26. To place these deficits in context, they represent about 15 percent of the General Fund revenue the state expects to collect each year of the period. In terms of spending, these annual deficits are larger than the annual amount the state currently spends on the University of California, California State University, university financial aid, and child care programs combined. Although state revenues potentially could exceed our estimates for the next several years, they are unlikely to approach the level required to eliminate these deficits altogether. Moreover, if the Legislature were to adopt the Governor’s budget, the state would enter future years with fewer tools to manage these deficits (such as reserves) than it has available today.

Governor’s Budget

Below, we explain the major components of the Governor’s plan for K‑12 education. We begin by explaining the overall approach, then describe the specific solutions and proposed increases.

Overall Approach

Governor’s Budget Funds at the Estimates of the Minimum Guarantee. The Governor’s budget proposes to reduce General Fund spending on schools to align with the lower estimates of the minimum guarantee. The budget implements these reductions primarily through cost shifts and other one‑time solutions that would not have any immediate effect on school district budgets. The proposed solutions also free‑up Proposition 98 funding for several one‑time and ongoing funding increases. Figure 7 lists all of the Proposition 98 solutions and spending proposals affecting schools.

Figure 7

Governor’s K‑12 Proposition 98 Package

(In Millions)

|

Solutions and Reductions |

|

|

Shift prior‑year costs to future budgets |

‑$7,097 |

|

Discretionary reserve withdrawal |

‑4,946 |

|

LCFF attendance changesa |

‑1,217 |

|

State Preschool savings |

‑446 |

|

Total |

‑$13,705 |

|

Ongoing Increases |

|

|

LCFF COLA (0.76 percent) |

$564 |

|

Universal school meals |

122 |

|

COLA for select categorical programs (0.76 percent)b |

64 |

|

Training for literacy screenings |

25 |

|

CA College Guidance Initiative |

5 |

|

Inclusive College Technical Assistance Center |

2 |

|

Homeless Education Technical Assistance Centers |

2 |

|

Total |

$784c |

|

One‑Time Increases |

|

|

Green school bus grants (second round) |

$500 |

|

2023‑24 universal school meals increase |

65 |

|

Training for new mathematics framework |

20 |

|

Item bank for science performance tasks |

7 |

|

Instructional continuity |

6 |

|

FCMAT long term planning |

1 |

|

Science safety handbook |

—d |

|

Total |

$599 |

|

aConsists of a $2.6 billion reduction from the continuing phaseout of pre‑pandemic attendance funding, partially offset by a $796 million increase related to transitional kindergarten. bApplies to Adults in Correctional Facilities, American Indian programs, Charter School Facility Grant Program, Child and Adult Care Food Program, Child Nutrition program, Equity Multiplier, Foster Youth Program, K‑12 mandates block grant, and Special Education. cThe budget also proposes $2 million ongoing for a program supporting state parks access for fourth graders. This program is an existing pilot the state funded previously with non‑Proposition 98 funds. dReflects $150,000. |

|

|

LCFF = Local Control Funding Formula; COLA = cost‑of‑living adjustment; and FCMAT = Fiscal Crisis and Management Assistance Team. |

|

Budget Solutions

Budget Contains $13.7 Billion in K‑12 Spending Solutions. The Governor’s budget contains four main solutions that would reduce General Fund spending by $13.7 billion across 2022‑23 through 2024‑25. The largest solution is a funding maneuver that would move some prior‑year school spending to the non‑Proposition 98 side of the budget and delay budgetary recognition of the expenditure for several years. The budget also contains discretionary reserve withdrawals, baseline savings, and a one‑time reduction to unallocated preschool funds.

$7.1 Billion One‑Time Savings From Proposed Funding Maneuver. The school spending level the state previously approved for 2022‑23 exceeds the revised estimate of the Proposition 98 guarantee in the Governor’s budget by $7.1 billion. The largest solution in the Governor’s K‑12 plan is a proposal to “accrue” spending above the guarantee in 2022‑23 to future years. (The budget also proposes a similar shift affecting $910 million in community college spending.) Under the proposal, the state would reclassify the $7.1 billion above the guarantee as a non‑Proposition 98 expenditure. It would remove this expenditure from its books in 2022‑23, then recognize the expenditure gradually over a five‑year period, beginning in 2025‑26. The state would not reduce any previous payments to schools or attempt to recoup any of this funding in subsequent years. In effect, the state would be using its cash resources to finance payments to schools that exceed the Proposition 98 guarantee in the prior year and creating an internal obligation to recognize the underlying budgetary cost at some point in the future. Unlike a traditional loan, however, the state would not score this mechanism as borrowing, make payments to an external creditor, or accrue any interest. (The administration very recently released the trailer bill language associated with this proposal. We did not receive this language in time to review it for this analysis. However, this analysis reflects our best understanding of the proposal, which was confirmed by the administration.)

$4.9 Billion Discretionary Withdrawal From the Proposition 98 Reserve. The Governor proposes a $4.9 billion discretionary withdrawal to cover school spending that would otherwise exceed the minimum guarantee. Of this amount, the budget would use $2.8 billion for the Local Control Funding Formula (LCFF) in 2023‑24 and $2.1 billion for LCFF in 2024‑25. (The Governor also proposes a similar withdrawal of $722 million for community college programs.) These withdrawals would leave $3.9 billion in the reserve for future use. This balance exceeds the threshold triggering the cap on local school district reserves, meaning the cap would remain operative for at least another year.

$1.2 Billion Reduction in LCFF Costs From Lower Attendance. For the purpose of allocating funding under the LCFF, the state credits school districts with their attendance in the current year, previous year, or average of the three previous years (whichever is highest). Due to large decreases in attendance over the past few years, approximately 80 percent of school districts currently are receiving funding based on their three‑year average. Most of these districts will experience funding declines in 2024‑25 as their higher attendance levels from earlier years continue phasing out of their average. The Governor’s budget estimates this phaseout will reduce LCFF statewide by $2 billion (2.6 percent). Partially offsetting this reduction, the budget estimates an LCFF increase of $796 million related to the expansion of TK. This increase consists of $635 million for base, supplemental, and concentration grant funding generated by students who are newly eligible in 2024‑25 and $161 million to support lower staffing ratios for these students. Accounting for the attendance phaseout and the expansion of TK, the overall reduction in LCFF costs is $1.2 billion.

$446 Million One‑Time Reduction for State Preschool. The Governor’s budget proposes reducing Proposition 98 funding for State Preschool by $446 million on a one‑time basis in 2024‑25. This reduction reflects the administration’s estimate of State Preschool funds that would otherwise go unused. The proposal is not intended to reduce rates or slots. (The Governor also proposes a reduction of $172 million for non‑Proposition 98 State Preschool programs. This proposal also is intended to only reduce funds that would otherwise go unused.)

Spending Proposals

Budget Proposes Spending Increases Totaling $1.4 Billion. The Governor’s budget proposes $1.4 billion in new spending for K‑12 programs. Of this amount, $784 million is for ongoing increases and $599 million is for one‑time activities. From an accounting perspective, nearly all of the new spending is attributable to 2024‑25. The only exception is a portion of the increase for universal school meals ($65 million) that is attributable to 2023‑24.

$628 Million for 0.76 Percent Statutory Cost‑of‑Living Adjustment (COLA). The state calculates the COLA each year using a price index published by the federal government. This index accounts for changes in the cost of goods and services purchased by state and local governments across the country during the preceding year. For 2024‑25, the administration estimates the statutory COLA rate is 0.76 percent. (This rate is relatively low by historical standards, likely reflecting decreases in energy prices that have occurred since the summer of 2022.) The Governor’s budget provides an ongoing increase of $628 million to cover the associated cost for K‑12 programs—$564 million for LCFF and $64 million for various categorical programs.

$500 Million for Second Round of Green School Bus Grants. The June 2022 budget plan established a program to fund zero‑emission school buses and related infrastructure (such as charging stations). Trailer legislation requires the California Air Resources Board and the California Energy Commission to award grants to interested school districts on a competitive basis. The Legislature previously approved $500 million to fund the first round of grants under the program and adopted intent language to allocate additional funding in the future. The Governor’s budget provides $500 million for a second round of grants.

$187 Million for Universal School Meals. The state implemented a universal meals program in 2021‑22 that reimburses schools for the cost of serving two daily meals to every student. The Governor’s budget provides a one‑time allocation of $65 million in 2023‑24 and an ongoing increase of $122 million in 2024‑25 to support this program. As we explain in a later chapter, these increases are based on estimated growth in the number of meals served and an adjustment to align the state reimbursement rate with the federal rate.

$67 Million for Other Increases. The Governor’s budget proposes several smaller increases consisting of nearly $34 million for ongoing programs and nearly $34 million for one‑time activities. Most of these augmentations involve teacher training and professional development activities or education technology initiatives. The largest ongoing amount is $25 million to fund a new literacy screening mandate. The largest one‑time amount is $20 million to provide training for teachers on the state’s new mathematics framework.

Assessment

Below, we provide our assessment of the Governor’s budget. We begin with the overall architecture, then analyze the specific one‑time actions and ongoing proposals.

Overall Comments

Governor’s Plan Recognizes a Budget Problem and Introduces a Few Reasonable Ideas. The state faces a much larger budget problem now than the one it confronted when it adopted the June 2023 budget plan. The Governor’s plan for schools recognizes that the state likely cannot balance its budget without solutions that align school spending with the lower estimates of the Proposition 98 guarantee. Regarding the specific solutions, the budget sets forth a few reasonable ideas. Most notably, the Governor signals that he is willing to work with the Legislature to access funds in the Proposition 98 Reserve and identify savings in the State Preschool program. Although we critique some aspects of these ideas, they represent reasonable initial steps toward resolving the budget shortfall.

Major Concerns With Proposed Funding Maneuver. We have major concerns with the Governor’s proposal to allow schools to keep cash disbursements above the minimum guarantee without recognizing the budgetary cost of those payments. This proposal creates a new type of budget solution: effectively, an interest‑free loan from the state’s cash resources and, as such, it sets a problematic precedent. It also creates a binding obligation on the state—one which will worsen the state’s already large forecasted deficits, requiring even more difficult decisions by the Legislature in the future. It also raises transparency concerns by obfuscating the true condition of the budget. We discuss our concerns with this proposal in more detail in The 2024‑25 Budget: The Governor’s Proposition 98 Funding Maneuver.

Significantly More Budget Solutions Needed Address the Shortfall. Given the numerous drawbacks of the proposed maneuver, the Legislature likely will want to explore alternative solutions. To avoid this proposal entirely, the state would need to identify $7.1 billion in one‑time (or ongoing) K‑12 education solutions (and $910 million in community college solutions). In addition, the Proposition 98 guarantee is likely to decline further over the coming months. Under our latest estimates, the guarantee is $7.7 billion below the Governor’s budget level across the three‑year period. Assuming the state attributes 89 percent of this reduction to schools (and 11 percent to community colleges, consistent with its historical practice), the funding available for schools would be $6.9 billion lower. If the Legislature were to avoid the funding maneuver entirely and reduce funding to our lower estimates of the guarantee, the state would need to identify a total of $14 billion in reductions or solutions affecting schools. As we describe later, some of these solutions could consist of larger required reserve withdrawals. Even after accounting for larger withdrawals, however, the Legislature likely would need to explore a broad swath of options, make reductions in multiple areas, and reassess its approach to ongoing programs.

Districts Have Local Funds That Could Help Address Reductions in State Funding. Districts have three main sources of funding in their local budgets that could help address potential reductions in state funding: (1) two large and relatively flexible multiyear block grants, (2) general purpose reserves, and (3) unspent federal funds. Regarding the block grants, districts have received $6.8 billion from the Learning Recovery Emergency Block Grant (available through 2027‑28) and $3.4 billion through the Arts, Music, and Instructional Materials Discretionary Block Grant (available through 2025‑26). Regarding reserves, the available data show that as of June 30, 2022, districts held $10.4 billion in reserves designated for general purposes or economic uncertainty (equivalent to 11.5 percent of their annual expenditures). Although more recent data are not yet available, our understanding is that district reserves remained near these levels entering 2023‑24. Finally, the available data show that as of December 31, 2023, districts held nearly $5 billion in unspent federal funds from the American Rescue Plan Act. (These funds are available for expenditure through September 30, 2024.) These three fund sources represent a much larger cushion for districts compared with the amount of local funding available during previous downturns.

One‑Time Solutions

Discretionary Reserve Withdrawal Is Warranted—if Used as a Solution for 2022‑23. Discretionary withdrawals from the Proposition 98 Reserve are contingent upon the Governor declaring a budget emergency and the Legislature enacting a law authorizing the withdrawal. Although the Governor has not yet declared a budget emergency, the proposal for a withdrawal signals the Governor is open to using reserves as a solution. We share the Governor’s view that a reserve withdrawal is warranted, but have concerns about the way the budget would use these funds. Reserves generally provide the greatest benefit for the state budget—and for schools—when the state is facing a large, unexpected shortfall and would need to adopt disruptive alternatives if it did not withdraw reserves. The significant drop in the guarantee in 2022‑23 meets all of these conditions. The Governor’s budget, however, would use reserves to cover costs in 2023‑24 and 2024‑25, including to free‑up funding for spending increases. Using reserve withdrawals to support new spending seems contrary to the core purpose of the reserve—protecting existing programs—and diminishes an important tool that could mitigate the prior‑year shortfall. In addition, the estimate of the Proposition 98 guarantee is higher in 2024‑25, making the case for reserve withdrawals that year less compelling.

Formulas Could Require Withdrawal of Remaining Reserve Balance. The constitutional formulas governing the Proposition 98 Reserve generally require withdrawals when the Proposition 98 guarantee is growing slowly relative to changes in inflation and student attendance. Whereas the Governor’s budget anticipates relatively strong growth in the guarantee from 2022‑23 to 2023‑24, our estimate of the guarantee in 2023‑24 reflects notably weaker growth. Assuming the state uses a discretionary withdrawal to cover at least a portion of the drop in 2022‑23, the constitutional formulas likely would require the state to withdraw the remaining balance in 2023‑24. Whereas the Governor’s budget has $3.9 billion remaining in the reserve, the state under our estimates would have to allocate this amount for programs.

State Preschool Reduction Is Reasonable, but Needs Additional Monitoring. The proposed reduction for State Preschool is intended to align the budgeted amount with anticipated costs of the program. While a reduction is reasonable, the Legislature will want to wait for additional program data before determining the amount necessary to continue covering program costs. One uncertainty is program enrollment. If program enrollment increases, the costs associated with providing certain payments in 2024‑25 will increase. Alternatively, the state could identify other unspent funds the administration has not yet included, such as funds set aside for unallocated slots in the current year.

State Could Achieve Additional One‑Time Savings by Reducing Unallocated Grants. Over the past three years, the state has approved more than $18 billion for one‑time grants supporting various school activities. As of January 2024, we estimate that about $4.5 billion of this amount remains unallocated (Figure 8). The unallocated funds generally consist of competitive grants for which the state has either not finished reviewing applications or not yet disbursed funding. The grant with the largest amount of unallocated funds is the Community Schools Partnership Program ($2.6 billion). Many of the other grants with unallocated funds involve teacher training and professional development initiatives. In contrast to the approach for most other areas of the budget, the Governor does not propose revisiting any of these one‑time allocations or reverting unspent funds. If the Legislature were to reduce any of these unallocated grants, it could use the savings as a one‑time budget solution.

Figure 8

Estimate of Unallocated One‑Time Grants

LAO Estimates (In Millions)

|

Program |

Amount available |

|

Community schools |

$2,594 |

|

Green school bus grants (first round) |

500 |

|

Golden State Pathways Program |

475 |

|

Teacher and counselor residency grants |

330 |

|

National board certification grants |

205 |

|

Inclusive Early Education Expansion Program |

163 |

|

Dual enrollment access |

122 |

|

Other |

108 |

|

Totals |

$4,495 |

Ongoing Spending

Growing Shortfall in Ongoing Programs Sets Up Difficult Decisions Next Year. Turning to ongoing programs, the Governor’s budget would expand the state’s reliance on one‑time Proposition 98 funding to cover ongoing program costs. Under the June 2023 budget plan, the state used nearly $1.6 billion in one‑time funds to cover ongoing costs in 2023‑24. This shortfall increases under the Governor’s budget, growing to nearly $2.2 billion in 2024‑25. (This shortfall reflects the $2.1 billion reserve withdrawal and an additional $37 million from other one‑time funds.) Entering 2025‑26, the state would need to make up this shortfall before it could fund other priorities. Accounting for a similar use of one‑time funds for community college apportionments, the total shortfall across all K‑14 programs is $2.7 billion—equivalent to nearly all of the growth in the Proposition 98 guarantee the budget anticipates in 2025‑26. Having an ongoing shortfall places the state and schools in a relatively risky financial position and increases the likelihood the state is unable to maintain its commitments to existing programs next year.

Funding Statutory COLA Contributes to Ongoing Shortfall. State law automatically increases most ongoing programs by the statutory COLA rate unless the Proposition 98 guarantee is insufficient to cover the associated costs. In these cases, the law authorizes the Department of Finance (DOF) to reduce the COLA rate to fit within the K‑12 portion of the guarantee. Instead of invoking this exception, the Governor’s budget funds the full COLA in 2024‑25 even though the guarantee cannot even support existing program costs. This budgeting approach accounts for $628 million of the $2.2 billion shortfall in 2024‑25 and requires the state to rely even more heavily on one‑time solutions like reserve withdrawals. Moreover, it represents the second consecutive year in which the Governor has not aligned the COLA rate with the guarantee. Whereas the estimates of the Proposition 98 guarantee from May 2023 showed the state could cover a 5.1 percent COLA in 2023‑24, the Governor instead proposed funding an 8.22 percent statutory COLA. If the state had reduced the COLA rate for 2023‑24, it would face little or no ongoing shortfall in 2024‑25.

LCFF Cost Estimates Likely Too High. Separate from our assessment of the COLA, we think the baseline estimates of LCFF costs in the Governor’s budget are likely too high. Our latest estimates are about $1.8 billion lower—$690 million lower in 2023‑24 and $1.1 billion lower in 2024‑25. The largest contributing factor is our treatment of TK. Although our underlying attendance estimates are similar, the Governor’s budget scores the LCFF costs for these newly eligible students immediately. If a district receives funding based on its average attendance over the past three years, however, the full effect of this additional attendance will not materialize for several years. Given that most districts are funded this way, we anticipate that TK expansion will have only modest effects on LCFF costs in 2023‑24 and 2024‑25.

State Likely Could Achieve Additional Savings by Revisiting Recent Program Expansions. Over the past three years, the state has established or significantly expanded several large ongoing programs. Most notably, the state established the Expanded Learning Opportunities Program (ELOP), made all students eligible for free school meals, significantly increased funding for State Preschool, provided much larger reimbursements for school transportation, and funded lower staffing ratios for TK students. In 2023‑24, the state will spend more than $9 billion on all of these programs combined. The Governor’s budget does not propose any changes to these programs except for the one‑time reduction to State Preschool. If the Legislature were to revisit any of these programs, it could likely find ways of achieving its core goals at somewhat lower cost. Reductions to any of these programs would help the state help the state address the current budget problem and align its ongoing spending level with the funding available under Proposition 98.

Recommendations

Below, we provide our recommendations for addressing the budget shortfall. We begin by outlining an overall approach, then recommend specific one‑time solutions and ongoing actions consist with this approach.

Overall Approach

Build Alternative Budget Package That Prioritizes Core Programs and Budget Stability. The Governor’s budget would avoid immediate reductions to school programs, but it relies heavily on solutions that shift expenditures into the future. The Governor’s proposals would worsen future state budget deficits (through the funding maneuver) and increase the ongoing shortfall in LCFF (through reliance on one‑time funds). This budgeting approach positions the state poorly—making spending commitments the state would have difficulty sustaining and setting up more difficult choices for next year. We recommend the Legislature take a different approach—one that prioritizes core school programs but also promotes stability for the budget moving forward. Taking this approach would require the Legislature to make some difficult choices this year, but offers substantial advantages. Specifically, it would (1) reduce the overall state deficit and the shortfall in ongoing programs, (2) position the state to provide funding increases for schools in the future as state revenues improve, and (3) allow the Legislature to preserve its highest priorities. Figure 9 summarizes our recommendations.

Figure 9

LAO Recommendations for Addressing the

K‑12 Budget Shortfall

|

Overall Approach |

|

|

|

|

One‑Time Solutions |

|

|

|

|

|

Ongoing Spending |

|

|

|

|

|

Reject Funding Maneuver. The Governor’s proposed funding maneuver is bad fiscal policy, sets a problematic precedent, and creates a binding obligation on the state that will worsen future deficits and require more difficult decisions. We strongly recommend the Legislature reject it. The state has other options to achieve budgetary savings in 2022‑23 without the problematic downsides of this specific proposal.

Begin Identifying Additional Reductions and Solutions Now. We recommend the Legislature use its upcoming budget hearings to begin identifying the alternative reductions and solutions it would need to balance the budget. The next few months provide an opportune time to establish priorities, consider options, and assess trade‑offs. Waiting to begin this work in May, by contrast, would place the Legislature in a difficult position and provide little time for careful deliberation. Moreover, replacing the funding maneuver and addressing the drop in the guarantee would involve identifying up to $14 billion in alternatives—likely requiring the Legislature to sift through a large number of options. The rest of this report begins this process. Specifically, it critiques the Governor’s proposals with a view to reducing costs and introduces additional options that would provide a mix of one‑time and ongoing savings. Adopting more of these options reduces the likelihood that the Legislature would need to make reductions to core programs like LCFF to address the shortfall.

One‑Time Solutions

Use Reserve Withdrawal to Address 2022‑23 Shortfall. We recommend building a budget that (1) contains a discretionary reserve withdrawal and (2) directs the entire withdrawal toward addressing the shortfall in 2022‑23. Using reserves in this way would help the state accommodate the drop in the prior‑year guarantee without resorting to reductions in school programs. In contrast to the Governor’s funding maneuver, this alternative works within an existing legal framework, avoids setting a troubling fiscal precedent, and does not worsen future budget deficits. To the extent the state is required to withdraw any funds that remain in the reserve after covering the shortfall in 2022‑23, we recommend directing those funds toward existing program costs that would otherwise exceed the guarantee in 2023‑24. Using the reserve withdrawals in this way would help the state balance its budget with fewer disruptive changes for schools.

Reject All One‑Time Spending Increases. We recommend the Legislature reject all of the one‑time increases proposed in the Governor’s budget to achieve savings of $599 million. The largest proposal affected by this recommendation is the $500 million allocation for green school bus grants. Although the Legislature previously expressed its intent to provide additional funding for this program, the state has not yet awarded any grants from the initial $500 million it provided in previous budgets. In addition, federal grants (administered by the Environmental Protection Agency) and local funding (administered by air quality districts) are available to support the purchase of low‑ and zero‑emission school buses. Regarding the other one‑time increases, we do not think any of the proposals are urgent enough to justify the additional spending reductions or reserve withdrawals that would be needed to fund them in 2024‑25. We provide additional analysis and considerations for a few of these proposals later in this report.

Review Unallocated Funds and Reduce Lower‑Priority Grants. We recommend the Legislature review existing grants with unallocated funding and reduce or eliminate any grants that do not represent its highest priorities. One reasonable starting point would be to rescind some of the funding for community schools. For example, the Legislature could rescind $1 billion out of $2.4 billion currently set aside for future rounds of implementation grants and extension grants for current grantees. This would leave about $1.1 billion for providing implementation grants to roughly 400 grantees that are currently in the planning process and eligible for implementation grants this year and next year, as well as maintain $280 million for providing two‑year extension grants to current grantees. This reduction also accounts for the likelihood that in tighter fiscal times, districts are likely to have less interest in implementing the community schools model this grant is intended to support. Any savings the Legislature identifies from unallocated grants would help address the budget shortfall and reduce the likelihood of other reductions that districts might find more disruptive.

Explore One‑Time Reductions to Certain Ongoing Programs. For a few ongoing programs, the state likely could make one‑time reductions that districts could accommodate by drawing upon unspent carryover funding. Two of the programs for which we anticipate districts have unspent funds available are ELOP and the Special Education Early Intervention Grant. If the state were to reduce funding temporarily, most districts likely could continue to support the underlying activities by drawing upon their unspent funds from previous years. Temporary reductions to programs like these likely would be less disruptive than reductions to programs for which districts currently have little or no carryover funding. In March, the state will receive updated information about the amount of unspent funding districts had for each program at the end of 2022‑23. A related solution would be to pause new grants under existing programs. For example, the state could temporarily stop making new awards under the Career Technical Education Incentive Grant Program (the state currently provides $300 million per year for these grants).

Ongoing Spending

Reject Statutory COLA Increase. We recommend zeroing out the COLA for the upcoming year. Rejecting the COLA would reduce the ongoing shortfall by $628 million and help the state avoid committing to an ongoing spending level it would have difficulty maintaining in the future. An additional consideration is that a zero COLA for 2024‑25 would follow several years of very large funding increases for LCFF. Between 2019‑20 and 2023‑24, the state increased LCFF funding rates per student by nearly 30 percent.

Reject Most Other Ongoing Proposals. In addition to the COLA, we recommend rejecting most other ongoing increases in the budget, including the increases for school meals and the funding for literacy screeners. (We do not recommend delaying expansion of TK.) This recommendation would reduce ongoing costs by $156 million. Regarding the additional funding for school meals, the state could address the shortfall by prorating the reimbursement rate. Regarding literacy screening, we think the proposed increase is premature given that the state has not yet adopted the literacy screening tool.

Plan for Lower Attendance‑Related Costs. We recommend the Legislature (1) plan to adopt lower LCFF cost estimates than Governor’s budget anticipates for 2023‑24 and 2024‑25 and (2) use updated data that will be released within the next few weeks to calibrate its estimates. Related to these recommendations, we recommend ensuring these estimates account for the interaction between the expansion of TK and the three‑year rolling average attendance calculation. Under our latest estimates, the overall cost of LCFF would be $1.8 billion lower across 2023‑24 and 2024‑25. The updated data, however, easily could change these estimates by several hundred million dollars in each year. Adopting lower LCFF cost estimates would reduce the size of the budget problem the Legislature needs to address.

Explore Changes to Ongoing Programs That Could Generate Additional Savings. If the Legislature were to revisit some recent program expansions, it could likely find ways of achieving its core objectives in less costly ways. The ongoing savings the state identifies through this process would help the state address the current shortfall and ease future budget pressure. Below, we outline options for reducing costs in five large programs (the amounts in parentheses indicate total spending in 2023‑24):

- ELOP ($4 Billion). The state created this program in the 2021‑22 budget to further fund educational and enrichment activities for K‑12 students outside of normal school hours. ELOP allocations are based on attendance in elementary grades and calculated using two different per‑student rates. We understand that some districts are not on track to spend all of their ELOP funds in part due to challenges in hiring staff and given that, similar to other after school programs, not all students are participating. The state has an opportunity to reevaluate whether the ELOP funding model can be simplified and/or restructured to further incentivize student participation. One option is to strengthen the fiscal incentive for districts to serve more students by distributing funds based on actual student participation rather than assume 100 percent participation. Even a relatively modest change to assume 90 percent participation would reduce costs by several hundred million dollars. (Regardless of how the Legislature proceeds, we recommend the state require districts to report data on program participation to help the state gauge student interest and ensure alignment with overall program goals.)

- State Preschool ($1.8 Billion). The state made programmatic changes to State Preschool in 2021‑22 and 2022‑23. The actual costs associated with implementing these changes were less than budgeted, resulting in funds that were anticipated to go unused. The 2023‑24 budget package redirected these funds to cover costs associated with a new two‑year collectively bargained early education and parity agreement. Beginning 2025‑26, the state will again have anticipated unspent funds that could be used to ease future budget pressure. In a forthcoming brief, our office will discuss this issue in more detail.

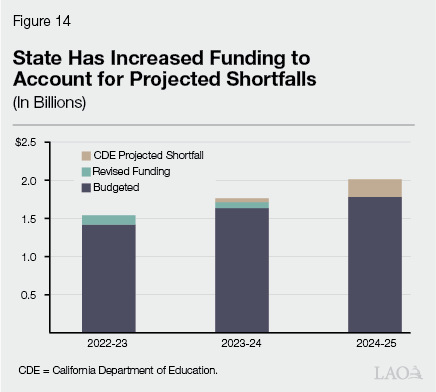

- School Nutrition ($1.7 Billion). The implementation of universal school meals in 2022‑23 and an increase in the reimbursement rate have resulted in an 827 percent increase in state funds provided to the program compared to 2018‑19 funding levels. Program costs are higher than anticipated and recent projections from the California Department of Education (CDE) indicate an additional state fund shortfall. In the “School Nutrition” section of this report, we discuss options to contain future cost growth in the program while maintaining the requirement for public schools to continue offering free meals to all their students. These options include setting rates at a lower level and revisiting the approach to COLA.

- School Transportation ($1.2 Billion). School districts historically received a fixed amount of funding for transportation based on the size of the programs they operated during the 1970s. The June 2022 budget plan significantly increased funding so that every district would receive an allowance equal to 60 percent of its transportation expenditures during the previous year. If the Legislature reduced the rate to 50 percent, the state could save approximately $200 million per year while still minimizing historical funding disparities among districts.

- TK Staffing Add‑On ($505 Million). In 2022‑23, the state began providing additional funding based on TK attendance. (This is in addition to funding the state already provided for these students through LCFF.) To receive this funding, districts must maintain an average of 1 adult for every 12 students in TK classrooms at each school site. Beginning in 2025‑26, districts must maintain an average of 1 adult for every 10 students. Our understanding is that the existing rates were calculated based on an assumption that TK classrooms would have 20 students, aligning with the policy to have 1 adult for every 10 students. The Legislature could modify the rates to align with the current ratio. If the Legislature were to fund based on the assumption that TK classrooms have 24 students (consistent with a 1‑to‑12 ratio), it would result in savings of about $100 million. Next year, the Legislature could assess its fiscal situation and determine whether higher staffing ratios and associated rates could be covered within its ongoing Proposition 98 funding levels.

Consider Reducing Funding Streams That Are Based on Antiquated Factors. Another way the Legislature could obtain ongoing savings is by revisiting three LCFF add‑ons that provide additional funding for certain districts based on historical factors. Unlike the core components of the formula, these add‑ons are not based on the number of students districts currently enroll or the needs and characteristics of those students. Instead, they provide additional funding based primarily on the size of certain programs districts operated decades ago. Eliminating or scaling back these add‑ons would reduce historical funding inequities among districts, simplify the LCFF, and provide ongoing savings. If the Legislature were concerned that eliminating these add‑ons immediately would be disruptive for district budgets, it could provide for a gradual phaseout. Below, we profile these three add‑ons (the parenthetical amounts indicate expenditures in 2023‑24):

- Targeted Instructional Improvement Block Grants ($855 Million). This add‑on provides additional funding for school districts that (1) operated desegregation programs during the 1980s, and/or (2) benefited from general‑purpose grants intended to equalize district funding levels during the 1990s. The add‑on is a fixed amount and unrelated to whether a district currently operates a desegregation program or the level of funding the district receives relative to other districts.

- Minimum State Aid ($356 Million). This add‑on provides additional funding for school districts and COEs with high levels of local property tax revenue per student. The add‑on amount is based on the level of state funding the district or COE received prior to the LCFF and is unrelated to the programs it currently operates or the characteristics of its students.

- Economic Recovery Targets ($61 Million). The state created this add‑on to ensure all districts would receive at least as much funding under the LCFF as they would have received if the state had retained its former funding system and increased it for the statutory COLA. Over the past decade, the state has provided multiple LCFF increases beyond the statutory COLA. Based on these increases, all districts are likely receiving more funding than they would have received under the former system, adjusted for COLA.

School Nutrition

In this section, we provide background on school nutrition in California, describe the Governor’s proposed augmentations, and offer options to reduce costs within the program.

Background

State Implemented Universal Meals in California. Trailer legislation related to the 2021‑22 budget package required that, beginning in 2022‑23, all public schools provide one free breakfast and one free lunch per school day to any student requesting a meal. (Under a temporary federal pandemic policy, schools had the option to provide free meals to all students prior to the enactment of state legislation.) The 2023‑24 budget includes $1.6 billion Proposition 98 General Fund and $2.6 billion federal funding to provide a projected 813 million school meals during the academic year.

Universal Meals Relies on School Participation in Both Federal and State Programs. To receive the state reimbursement rate, schools must participate in two federal nutrition programs—the National School Lunch Program and School Breakfast Program. These federal programs have many requirements that schools must follow, such as serving meals that meet certain nutritional standards. The federal government reimburses schools for each meal served. The state supplements federal funds with additional state funds.

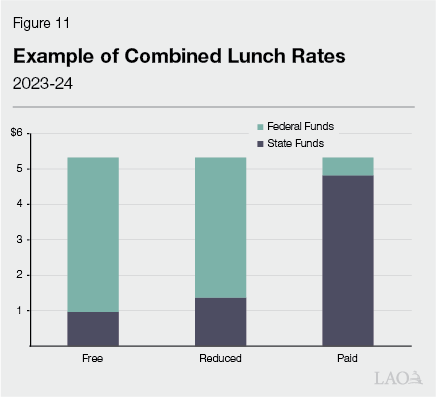

Federal Reimbursement Rate Varies by Household Income of Students Served. The federal nutrition programs reimburse schools based on the number of meals they serve, with the per‑meal reimbursement rate varying by student household income. Students from households with incomes at or below 130 percent of the federal poverty level ($32,318 annually for a family of three) receive meals reimbursed at the “free” rate. Students from households with incomes at or below 185 percent of the federal poverty level ($45,991 annually for a family of three) receive meals reimbursed at the “reduced” rate. All other meals are reimbursed at the “paid” rate. In 2023‑24, the federal government reimburses schools up to $4.35 for lunches served at the free rate and up to 50 cents for lunches served at the paid rate. Federal meal reimbursement rates are adjusted annually by a federal price index that reflects changes in the costs of meals purchased away from home.

Federal Government Gives School Districts Alternative Reimbursement Options. To be reimbursed by the federal government, schools typically must track which student is served a meal to determine the reimbursement rate. The federal government offers some alternative reimbursement options aimed at reducing administrative burden. The most common of these options is the Community Eligibility Provision (CEP), but there are three other provisions school districts can choose. Figure 10 illustrates how CEP works compared to the traditional approach. Most notably, CEP relies on an Identified Student Percentage (ISP), which is a calculation of the share of enrolled students “directly certified” for free meals. Students that are directly certified are automatically eligible for free meals due to their participation in CalFresh, CalWORKs, or Medi‑Cal. (These are state programs for low‑income individuals and families that provide food assistance, cash grants and supportive services, and health care services, respectively.) The state shares participation information with school districts, so these students do not need to fill out meal applications to determine eligibility.

Figure 10

Comparing Reimbursement Options

|

Traditional |

Community Eligibility Provision |

|

|

Site Eligibility |

All schools. |

In 2023‑24 and prior years, only schools with an Identified Student Percentage (ISP) at or above 40 percent. ISP is calculated by the share of students directly certified for free lunch, based on participation in certain programs. Beginning in 2024‑25, program is available to schools with an ISP at or above 25 percent. |

|

Method of Determining Student Eligibility |

Schools directly certify students and collect meal applications. |

Schools directly certify students. They do not collect meal applications. |

|

Federal Reimbursement Rates |

Schools reimbursed at free, reduced, or paid rate. Based on meal count and student household income. |

ISP is multiplied by 1.6 to determine the share of meals served that will be reimbursed at the free rate. All other meals will be reimbursed at the paid rate. |

|

Federal Reimbursement Example |

School A serves ten lunches to students with household incomes at the free level and ten lunches to students with household incomes at the reduced level. School A would receive meal reimbursement for 20 lunches, half at the higher free rate and half at the lower reduced rate. |

School B serves 20 lunches and has an ISP of 50 percent. School B would have 80 percent of meals served reimbursed at the free rate. School B would receive reimbursement for 16 meals at the free rate and 4 meals at the paid rate. |

If Eligible, State Requires Schools to Opt in to Federal Reimbursement Flexibility. To increase federal reimbursements, state law requires schools eligible for CEP to participate in either CEP or one of the other alternative reimbursement options. This has resulted in significantly higher CEP participation. In 2018‑19, 24 percent of schools participated in CEP, compared to 51 percent of schools in 2022‑23.

State School Nutrition Program Supplements Federal Reimbursement. State law sets a specific state rate for meals reimbursed by the federal government at the free rate. For meals reimbursed by the federal government at the reduced or paid rates, the state provides the amount of funds necessary to ensure the combined state and federal rate is equal to combined rate for free meals. This results in free, reduced, and paid meals generating the same total reimbursement for schools. Figure 11 shows a school lunch reimbursement example (the combined rate for breakfast is lower). A meal reimbursed by the federal government at the free rate receives the smallest amount of state funds whereas a meal reimbursed at the paid rate receives the largest amount of state funds.

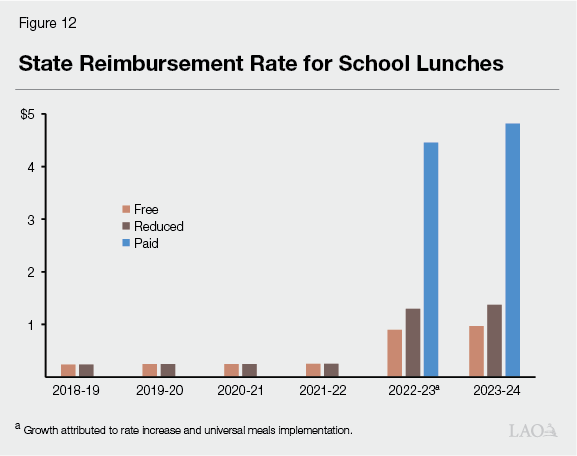

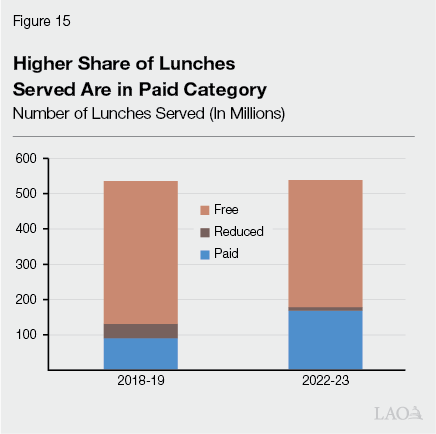

State Contribution to School Meals Has Grown Significantly in Recent Years. Prior to 2022‑23, the state contributed roughly 25 cents per free and reduced meal served (the state did not reimburse paid meals). In 2022‑23, the state provided a discretionary rate increase of 63 cents per meal—a 238 percent increase to the state rate for a free meal. Figure 12 shows the state contribution rate over the past six years. The state reimbursement rate for school meals is grown annually by the statutory COLA provided for LCFF and select K‑12 categorical programs.

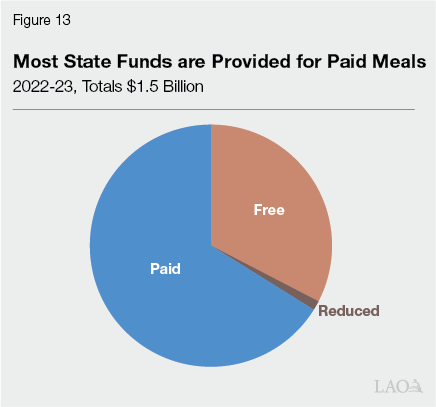

Total State Funds Provided for School Meals Has Increased Significantly. In 2018‑19, the last year of comparable data not impacted by the pandemic, the state provided $164 million for the state rate of school meals. This amount has grown to $1.5 billion in 2022‑23 (an 831 percent increase), due to both universal meal implementation and the 63‑cent rate increase. Of this amount $1.1 billion is for lunch reimbursements, with the remainder provided for breakfast reimbursements. As Figure 13 shows, most of the state funds provided in 2022‑23 ($1 billion), are to reimburse paid meals.

State Recently Established Automatic Backfill for School Nutrition. Beginning in 2022‑23, the budget included provisional language requiring DOF to augment the appropriation for school nutrition if expenditures are projected to exceed the amount available. CDE is to report to the administration and Legislature on or before January 20 whether the amount included in the budget is sufficient to address these costs. Prior to the inclusion of this provisional language, the Legislature had discretion over how to address the shortfall. If no additional funding was provided to address a shortfall, the state meal rate was to be prorated administratively. Since 2013‑14, the state meal rate was prorated three times, but the rate was restored in all three cases. In two instances, CDE determined there were enough funds to restore the rate once it received final meal counts. In one instance the Legislature provided additional funds to cover the shortfall.

New Federal Rule Expands CEP Eligibility. In the fall of 2023, the federal government enacted new regulations that lowered the eligibility threshold for schools to participate in CEP. Beginning in 2024‑25, a school can participate in CEP if it has an ISP of 25 percent or higher. Previously the requirement was an ISP of 40 percent or higher. This rule change means that schools with an ISP between 25 percent and 40 percent are now required under state law to participate in one of the federal alternative reimbursement options.

Governor’s Proposal

Increases Funding by $65 Million One Time in the Current Year. The Governor’s budget includes $65 million to cover an anticipated shortfall in 2023‑24. The bulk of this adjustment, $48 million, is attributed to an anticipated increase in meals served in 2023‑24 compared to the amount budgeted. The administration estimates lunches served will increase by 1 percent and breakfasts served will increase by 3 percent above 2022‑23 meals served. The Governor also proposes to backfill $12 million that was initially provided for 2023‑24 school meals, but was shifted to cover a shortfall in 2022‑23. Lastly the Governor’s budget includes $5 million to account for an increase in the federal COLA made available in July. An increase in the federal rate results in higher state costs for meals reimbursed at the paid rate.

Increases Funding by $122 Million Ongoing in 2024‑25. For 2024‑25, the Governor’s budget increases funding by $122 million compared to the 2023‑24 budgeted level, which is intended to cover the cost of the existing school nutrition program. Of this amount, $53 million is associated with the anticipated shortfall in 2023‑24 that is expected to carry forward into 2024‑25. The remainder of the growth ($69 million) is primarily attributed to the anticipated federal COLA that would increase the state contribution for meals at the paid rate. The Governor’s budget assumes the paid state rate will increase to $5.13 per lunch, reflecting a 6 percent increase from 2023‑24. The administration indicated this estimate will be revised as more data becomes available.

Increases Funding by $13 Million to Provide State COLA. The Governor’s budget also provides $13 million to provide a 0.76 percent COLA for school nutrition rates. This increases the state contribution for a free meal from 96.9 cents to 97.6 cents.

Assessment