LAO Contact

September 7, 2023

MOU Fiscal Analysis: Bargaining Units 1, 3, 4, 11, 14, 15, 17, 20, and 21 (SEIU Local 1000)

On Saturday, August 26, 2023, the administration released a proposed labor agreement between the state and the nine bargaining units represented by Service Employees International Union, Local 1000 (Local 1000). Local 1000 represents about one-half of the state’s rank-and-file employees. As of July 1, 2023, Employees represented by Local 1000 work under the terms and conditions of an expired memorandum of understanding (MOU). This analysis of the proposed agreement fulfills our statutory requirement under Section 19829.5 of the Government Code. The administration has posted on the California Department of Human Resources’ (CalHR’s) website the agreement, a summary of the agreement, and a summary of the administration’s estimates of the proposed agreement’s fiscal effects. Our State Workforce webpages include background information on the collective bargaining process, a description of these and other bargaining units, and our analyses of agreements proposed in the past.

Background

Local 1000 in Context of State Workforce

Nine Bargaining Units Represented by One Union. Local 1000 represents about one-half of the state workforce. The nine bargaining units that are represented by the union include a variety of different types of employees and each bargaining unit is different. Figure 1 summarizes some of these differences. As the figure shows, Local 1000 represents small bargaining units with only a few hundred members as well as the state’s largest bargaining unit, Unit 1, which represents more than 56,000 members. While most of the units are comprised of more than 50 percent women, Units 11, 14, and 15 are majority men. Overall, Local 1000 represents 70 percent of women in the rank-and-file state workforce. With the exceptions of Units 3 and 21, the bargaining units represented by Local 1000 are comprised mostly of people of color. Overall, Local 1000 represents 56 percent of the people of color in the rank-and-file workforce. While all of the bargaining units have a higher vacancy rate than the average for non-Local 1000 bargaining units of 18 percent, a handful of them have vacancy rates that are greater than 5 percentage points above this average (Units 11, 15, and 20).

Figure 1

Calendar Year 2022 Snapshot of Local 1000 Bargaining Units

|

Bargaining Unit |

Position Count |

Share Female |

Share Person of Color |

Average Years of Service |

Average Base Pay |

Pay Subject to Retirement |

Share of Unit at Top Step |

Vacancy Rate |

|

1 |

56,293 |

62% |

66% |

11 |

$78,899 |

$66,426 |

44% |

20% |

|

3 |

1,413 |

51 |

37 |

10 |

108,407 |

91,160 |

20 |

22 |

|

4 |

20,145 |

76 |

73 |

8 |

49,335 |

34,547 |

46 |

23 |

|

11 |

2,678 |

37 |

57 |

9 |

62,883 |

31,222 |

37 |

25 |

|

14 |

340 |

30 |

62 |

12 |

65,665 |

54,312 |

59 |

23 |

|

15 |

4,142 |

43 |

82 |

8 |

45,314 |

28,149 |

58 |

30 |

|

17 |

5,625 |

72 |

77 |

9 |

121,500 |

77,288 |

63 |

22 |

|

20 |

5,524 |

79 |

77 |

8 |

60,303 |

34,901 |

67 |

28 |

|

21 |

543 |

71 |

44 |

10 |

102,434 |

92,094 |

60 |

24 |

Unit 1: Administrative, Financial, and Staff Services. The largest of the state’s 21 bargaining units, employees perform many different types of jobs across numerous state departments. These employees include accounting officers, auditors, analysts, and other professional classifications.

Unit 3: Professional Educators and Librarians. Employees are teachers, education specialists, and librarians in state institutions. Two-thirds of these employees work for the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR).

Unit 4: Office and Allied. Employees work in many state departments in a variety of classifications. Employees include office technicians, Department of Motor Vehicles field representatives, office assistants, and program technicians.

Unit 11: Engineering and Scientific Technicians. Employees work across many state departments. The largest classifications include California Department of Transportation (Caltrans) engineering technician and scientific aid. About two-thirds of the unit work for either the Department of Fish and Wildlife or Caltrans.

Unit 14: Printing and Allied Trades. Employees work as printing trade specialists, graphic designers, and bookbinders. While some employees work in various departments, most work for the Department of General Services (DGS) at the Office of State Publishing where the state budget, bills and laws, and other state documents are printed.

Unit 15: Allied Services. Employees include custodians employed by DGS who work in various state buildings, laundry workers, supervising cooks, and food services workers in state prisons and other institutions. More than one-half of these employees work for the Department of State Hospitals, DGS, or CDCR.

Unit 17: Registered Nurses. Employees include nursing staff who work in state prisons, state hospitals, and veterans’ homes.

Unit 20: Medical and Social Services. Employees include various medical and social services specialists who work in state prisons, veteran’s homes, developmental centers, and state hospitals. The largest Unit 20 classifications include Licensed Vocational Nurse, Self-Help Sponsor, Dental Assistant, Certified Nursing Assistant, and Pharmacy Technician.

Unit 21: Educational Consultants and Library. Employees are educational consultants who work for state education programs within the California Department of Education or other noninstitutional settings. The largest Unit 12 classifications include Education Programs Consultant, Special Education Consultant, and Education Fiscal Services Consultant.

Represented Employees Work in Most State Departments, but CDCR Is Largest Employer Department. Though employees represented by Local 1000 work for virtually every state department, 18 percent of employees represented by Local 1000 work for CDCR. Employees represented by Local 1000 work in every county in California and some even work outside of the state; however, most of them work in Sacramento County.

Compensation Study

Local 1000 Represents Hundreds of Classifications. The state has about 4,500 unique job classifications. Each classification has a separate salary range. Many of these classifications are similar but are differentiated by specific characteristic (for example, being employed by a specific department). Local 1000 represents about 800 unique classifications.

Most Local 1000 Occupation Groups Included in Compensation Study Found to Be Compensated Above Market. As we describe in greater detail in our May 2023 analysis, state law requires CalHR to complete total compensation studies where the department compares the state’s salary and benefits with the compensation provided by other employers to similar employees. When conducting its study, CalHR organizes the state’s thousands of classifications into occupation groups. In the case of Local 1000, the most recent compensation study evaluated 30 occupation groups. Each of these occupation groups include multiple state job classifications. For example, the largest occupation group, Management Analyst, includes more than 50 state analyst classifications that are represented by Unit 1. Figure 2 summarizes CalHR’s findings. As shown by the figure, CalHR found that only nine of the 30 occupations lagged the market, meaning the state’s compensation is less than the median employer. Two occupation groups—Medical Assistants and Transportation Inspectors—were found to lag the market by more than 20 percent. While most of the occupation groups were found to be compensated above market, seven occupation groups were found to lead the market (or be compensated above the median) by greater than 20 percent.

Figure 2

Most Local 1000 Occupation Groups Compensated Above Market

(Total Compensation)

|

Bargaining Unit |

Occupation Group |

Lead (+) or Lag (‑) |

Share of Unit |

|

|

Wage Only |

Total Compensation |

|||

|

20 |

Medical Assistants |

‑54.9% |

‑42.9% |

6.8% |

|

11 |

Transportation Inspectors |

‑35.8 |

‑20.3 |

3.7 |

|

1 |

Management Analysts |

‑33.5 |

‑17.2 |

35.0 |

|

1 |

Urban and Regional Planners |

‑24.5 |

‑13.4 |

1.6 |

|

4 |

Legal Secretaries and Administrative Assistants |

‑19.5 |

‑10.9 |

4.4 |

|

4 |

Court, Municipal, and License Clerks |

‑8.2 |

‑3.8 |

22.8 |

|

4 |

Bookkeeping, Accounting, and Auditing Clerks |

‑12.9 |

‑3.5 |

3.7 |

|

11 |

Civil Engineering Technologists and Technicians |

‑17.6 |

‑2.4 |

38.2 |

|

1 |

Computer Systems Analysts |

‑19.9 |

‑0.3 |

13.5 |

|

17 |

Nurse Practitioners |

‑15.0 |

1.0 |

1.6 |

|

1 |

Accountants and Auditors |

‑8.3 |

6.0 |

10.9 |

|

20 |

Nursing Assistants |

‑0.3 |

7.4 |

24.0 |

|

17 |

Registered Nurses |

‑5.3 |

8.5 |

87.2 |

|

4 |

Office Clerks, General |

2.3 |

8.8 |

49.9 |

|

1 |

Compensation, Benefits, and Job Analysis Specialists |

‑3.1 |

9.1 |

1.2 |

|

1 |

Payroll and Timekeeping Clerks |

5.7 |

9.4 |

1.9 |

|

21 |

Librarians and Media Collections Specialists |

‑1.5 |

9.4 |

13.6 |

|

1 |

Eligibility Interviewers, Government Programs |

9.8 |

10.6 |

3.6 |

|

1 |

Claims Adjusters, Examiners, and Investigators |

‑0.7 |

10.8 |

3.0 |

|

1 |

Tax Examiners and Collectors, and Revenue Agents |

6.9 |

11.2 |

5.0 |

|

11 |

Architectural and Civil Drafters |

‑4.2 |

13.2 |

7.7 |

|

15 |

Janitors and Cleaners, Except Maids and Housekeeping Cleaners |

0.3 |

15.2 |

45.0 |

|

20 |

Pharmacy Technicians |

‑2.3 |

16.7 |

8.2 |

|

3 |

Adult Basic Education, Adult Secondary Education, and English as a Second Language Instructors |

24.1 |

20.6 |

60.2 |

|

20 |

Licensed Practical and Licensed Vocational Nurses |

5.5 |

22.0 |

39.3 |

|

14 |

Printing Press Operators |

14.7 |

22.2 |

26.2 |

|

14 |

Graphic Designers |

5.8 |

22.5 |

32.9 |

|

21 |

Instructional Coordinators |

23.3 |

27.1 |

86.4 |

|

15 |

Cooks, Institution and Cafeteria |

17.7 |

28.3 |

3.6 |

|

20 |

Dental Assistants |

27.9 |

33.2 |

10.3 |

|

Local 1000 = Service Employees International Union, Local 1000; Lead = compensation is above market; and Lag = compensation is below market. |

||||

|

Source: 2020 California State Employee Total Compensation Report performed by the California Department of Human Resources. |

||||

Largest Local 1000 Occupation Group Found to Be Compensated Below Market. The Management Analyst occupation group is the largest occupation group included in the compensations study—accounting for more than one-third of Bargaining Unit 1 classifications. The study found that occupation group to lag the market total compensation by 17 percent.

Proposed Agreement

Major Provisions

In the below section, we summarize only the major provisions of the agreement. For a more detailed description of all of the provisions, refer to the administration’s summary or the agreement itself.

Term. The agreement would be in effect from July 1, 2023 through June 30, 2026. This means the agreement would be in effect for three fiscal years: 2023-24, 2024-25, and 2025-26.

General Salary Increases (GSIs). The agreement would provide three GSIs over the course of the agreement, specified below.

3 Percent July 1, 2023. All employees represented by Local 1000 would receive a 3 percent pay increase in 2023-24.

3 Percent July 1, 2024. All employees represented by Local 1000 would receive a 3 percent pay increase in 2024-25.

3 Percent or 4 Percent July 1, 2025. All employees represented by Local 1000 would receive either a 3 percent or 4 percent pay increase in 2025-26. Specifically, the agreement specifies that employees would receive a 4 percent pay increase if the Director of the Department of Finance determines that there are sufficient funds at the time of the 2025-26 May Revision.

Special Salary Adjustments (SSAs) for Specified Classifications. The agreement would provide the below SSAs. Unlike a GSI, an SSA adjusts the salary range of only specified classifications.

Payments to Lower Paid Classifications. Under the agreement, various specified classifications represented by Units 1, 4, 11, 14, 15, and 20 would receive a 4 percent SSA. The identified classifications are among the lowest paid classifications in state service. The administration indicates that about 27,300 full-time equivalent (FTE) employees across these bargaining units would be eligible to receive this SSA.

Payments to Various Other Classifications. The agreement would provide specified classifications SSAs ranging from 2.5 percent to 15.8 percent. The administration indicates that about 21,300 FTE employees across the bargaining units would be eligible to receive one of these SSAs.

Monthly $165 Payment to Each Employee. All employees who are eligible to receive state health benefits would receive a monthly payment of up to $165 under the agreement.

Various Pay Differentials. The agreement would adjust or expand existing pay differentials or establish new pay differentials. In order to be eligible for a pay differential, employees must meet the specific requirement for each pay differential.

Reduction in State and Employee Contribution to Prefund Retiree Health Benefits. The agreement would reduce the amount of money that the state and employees contribute to prefund retiree health benefits. Specifically, effective the first day of the pay period following ratification, the contribution rate would be reduced from 3.5 percent of pay to 3 percent of pay. Beginning in 2024-25, the agreement specifies that the contributions would adjust to maintain the standard that the state and employee each pays one-half of the normal cost.

Retention Payment for Food Service and Cook Classifications. Effective the first day of the pay period following ratification, employees in specified food services classifications who work for CDCR would be eligible to receive specified pay differentials after specified milestones are met.

Longevity Payment to Registered Nurses. The agreement would provide registered nurses who have worked for specified numbers of years a specified longevity payment ranging from 3 percent of pay to 4 percent of pay. These longevity payments would be phased in over the course of the agreement. The payment would be considered compensation for purposes of determining employees’ pension benefits.

New Alternate Range for Custodians at Health Care Facilities. Effective the first day of the pay period six months following ratification, the minimum and maximum salaries of a new alternate range for custodian classifications will be established that is 10 percent above existing ranges for custodians who are employed by specified departments who have facilities that are required to be maintained at the hospital level of cleaning.

Unit 3 Health Benefits. With the exception of Unit 3, the state’s contribution to health premiums of employee represented by Local 1000 are adjusted automatically as health premiums change. In the case of Unit 3, the agreement specifies the dollar amount of the state’s contribution. The proposed agreement would increase the state’s contribution to Unit 3’s health premiums in order to maintain the current proportion of the average health premiums paid by the state.

Retention Pay for California Department of Social Services (DSS), Disability Determination Service Division. Effective the first day of the pay period six months following ratification of the agreement, five specified classifications in the DSS Disability Determination Service Division would receive specified payments of either $2,000 or $3,000 annually.

Revise CDCR Career and Technical Education Program Salary Schedule Criteria. Effective the pay period following ratification, Unit 3 teachers at the CDCR Career and Technical education program would have the ability to supplement education with years of experience in a trade and/or completion of trade school to move up through the established salary schedule.

Increase Professional Dues Reimbursement. Effective the first day of the pay period following ratification, Unit 21 classifications would receive an increase in the amount of reimbursement they receive for membership dues in job-related professional societies or associations from $75 to $200 per year.

Monthly Payment to Certified Nursing Assistants at Yountville and West Los Angeles Veterans Home. Effective July 1, 2023, Unit 20 employees in the Certified Nursing Assistants classification employed at the Yountville or West Los Angeles veterans homes would be eligible to accrue a stipend up to a maximum of $9,000 over the course of the agreement. The payments would be made in amounts of $1,500 in January 2024, August 2024, January 2025, August 2025, January 2026, and August 2026.

LAO Assessment

Administration’s Fiscal Estimate

Significant Fiscal Effect. As Figure 3 shows, the administration estimates that the agreement would increase state annual costs by nearly $1.5 billion ($670 million General Fund) by 2025-26. If the GSI in 2025-26 is 4 percent, the annual cost would be about $125 million higher. The administration estimates that extending provisions of the agreement to excluded employees associated with Local 1000 would increase annual state costs an additional $234 million ($101 million General Fund) by 2025-26.

Figure 3

Administration’s Estimated Cost of Proposed Local 1000 Agreement

(In Millions)

|

Proposal |

FY 2023‑24 |

FY 2024‑25 |

FY 2025‑26 |

|||||

|

General |

All |

General |

All |

General |

All |

|||

|

General Salary Increases (GSIs)a |

$157.6 |

$348.5 |

$323.0 |

$713.6 |

$493.4 |

$1,089.7 |

||

|

Special Salary Adjustments |

89.5 |

205.5 |

89.5 |

205.5 |

89.5 |

205.5 |

||

|

$165 Per Month Payment |

38.1 |

84.2 |

65.3 |

144.4 |

65.3 |

144.4 |

||

|

Various Pay Differentials |

4.8 |

8.3 |

6.4 |

11.6 |

6.4 |

11.6 |

||

|

Retention Payment for Food Service and Cook Classifications |

5.9 |

6.2 |

7.9 |

8.2 |

7.9 |

8.2 |

||

|

Longevity Pay to Registered Nurses |

0.0 |

0.0 |

4.2 |

4.4 |

5.6 |

5.9 |

||

|

New Alternate Range for Custodians at Health Care Facilities |

2.3 |

2.4 |

6.9 |

7.1 |

6.9 |

7.1 |

||

|

Unit 3 Health Rates |

0.8 |

0.8 |

2.1 |

2.2 |

3.4 |

3.7 |

||

|

Retention Pay for CDSS—Disability Determination Service Division |

0.4 |

0.7 |

1.2 |

2.1 |

1.2 |

2.1 |

||

|

Revise CDCR CTE Salary Schedule Criteria |

1.6 |

1.6 |

2.1 |

2.1 |

2.1 |

2.1 |

||

|

Uniform and Footwear Allowances |

1.1 |

1.2 |

1.4 |

1.7 |

1.4 |

1.7 |

||

|

Increase Professional Dues Reimbursement |

0.4 |

0.7 |

0.6 |

0.9 |

0.6 |

0.9 |

||

|

$250 Per Month Napa and West Los Angeles Veterans Home Payment |

0.7 |

0.7 |

1.3 |

1.4 |

1.3 |

1.4 |

||

|

Other Provisionsb |

0.8 |

2.4 |

1.4 |

3.9 |

1.4 |

3.9 |

||

|

Reduction to State Contribution to Prefund Retiree Health |

‑12.0 |

‑26.2 |

‑16.0 |

‑34.9 |

‑16.0 |

‑34.9 |

||

|

Totals |

$292.0 |

$637.0 |

$497.0 |

$1,074 .0 |

$670.0 |

$1,453.0 |

||

|

aAssumes Local 1000 receives a 3 Percent GSI in 2025‑26. Per the agreement, the Director of the Department of Finance could determine that Local 1000 would receive a 4 percent GSI in 2025‑26. If a 4 percent GSI were provided, the annual state costs would be $125 million ($56.8 million General Fund) more beginning in 2025‑26. bThe administration assumes that a portion of these costs could be paid from existing resources and would not require a new appropriation from the Legislature. |

||||||||

|

CDSS = California Department of Social Services; CDCR = California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation; and CTE = career technical education. |

||||||||

Inflation and Local 1000

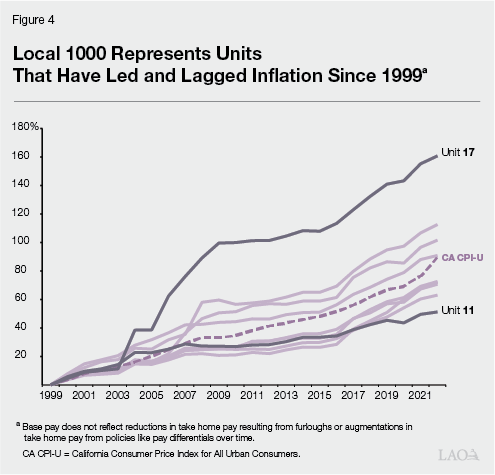

Wide Range of Effects of Inflation on Bargaining Units Represented by Local 1000. As Figure 4 shows, the nine bargaining units represented by Local 1000 have had different experiences with inflation since 1999. Specifically, the base pay for three Local 1000 units—Units 3, 17, and 20—grew at levels above inflation; Unit 14 kept pace with inflation; and five Local 1000 units—Units 1, 4, 11, 15, and 21—grew at levels below inflation.

The Proposed Agreement

Duration

Standing LAO Recommendation: Do Not Approve Agreements Longer Than Two Years. Since 2007, we have recommended that the Legislature not ratify labor agreements with durations longer than two years in order to maintain legislative flexibility and authority to respond to changing economic situations. An MOU establishes the state’s employee compensation policies and locks in state expenditures for the duration of the agreement. Though the Legislature has authority to modify economic provisions of ratified MOUs through its appropriation authority, in practice, it is difficult for the Legislature to exercise this authority.

Uncertainty Makes Legislative Flexibility Even More Important. By 2025-26—the last year of this agreement—General Fund revenues could be tens of billions of dollars higher or lower than current estimates. There is significant uncertainty about economic conditions by the end of this agreement. Inflation may remain elevated, in which case the pay increases provided by this agreement might not be sufficient to preserve employees’ purchasing power. Alternatively, if inflation continues to fall, the state could end up providing pay increases above the rate of inflation under the agreement, resulting in the state potentially paying more than might be necessary. Further, labor markets could remain tight or soften. While we cannot say with certainty how these economic conditions will unfold, we have advised the Legislature to remain cautious as key economic indicators—such as the treasury bond yield curve—have signaled an economic and revenue slowdown could be forthcoming.

Three-Year Agreement Locks-in State Costs and Limits Legislative Flexibility. Although future addenda or side letters may be established to address unforeseen issues that might materialize during the term of the MOU, the addenda review process established under Item 9800 of the annual budget act defers more authority to the Governor than the MOU ratification process. A shorter term allows the Legislature greater control over the state’s compensation policies.

Pay Increases

Proposed GSIs Close to Most Recent Inflation Levels. The most recent (July) California Consumer Price Index was 3.1 percent higher compared to the prior year. Since 2020, however, prices have risen 17 percent. GSIs provided by prior agreements to some bargaining units represented by Local 1000 did not keep pace with these increases, as noted above. Although the tentative agreements’ GSIs would maintain wages, they do not catch up to prior price increases. Moreover, if inflation remains elevated, state employees’ purchasing power likely will be further eroded by 2025-26. Alternatively, if inflation continues to fall, the state could provide GSIs above the rate of inflation, thereby potentially paying more than might be necessary at the time. If the agreements had shorter terms, the state could consider GSIs that reflect the economic conditions in a few years.

Agreement Provides Many SSAs. Typically, the state provides a GSI to all workers in a bargaining unit to account for inflation, whereas SSAs are provided to ensure wages for specific classifications are competitive with other employers. The agreement relies more heavily on SSAs than past agreements. These SSAs combined with the GSIs and other pay increases could make it so that many employees would not experience a loss in purchasing power if inflation were to persist at elevated levels.

Administration Offers No Justification for SSAs. Unlike a GSI, which provides the same pay increase to all classifications represented by a bargaining unit, an SSA provides specified pay increases to specified classifications. While a GSI can be justified by the rate of inflation, an SSA, on the other hand, requires further justification as it singles out one classification over another to receive a pay increase within the same bargaining unit. That being said, it is not clear what methodology, if any, was used to identify which classifications should receive SSAs and at what levels. While some of the specified classifications are part of occupation groups that were identified in the compensation study as being compensated below market, others were either found to be compensated above market or were not included in the compensation study. The administration does not provide a justification for the various SSAs, but states they are the result of the bargaining process. The significant use of SSAs with no justification from the administration reduces transparency and increases complexity of the agreement with only days to review. This limits the ability for both the Legislature and the public to understand why some state employee should receive higher pay increases than others.

Legislature’s Role in Bargaining Process

Legislature Is Ultimate Authority of Any Labor Agreement. Under the Ralph C. Dills Act, while the Governor negotiates terms and conditions of employment with bargaining units, the Legislature retains the ultimate authority to approve or reject agreements. The Legislature can reject an agreement either by (1) rejecting a tentative agreement that is submitted to the Legislature for ratification or (2) not appropriating sufficient funds to pay for the terms of an MOU that the Legislature has already ratified.

Administration’s Delivery of Agreement Does Not Allow for Sufficient Time for Legislative or Public Review. The administration submitted this agreement to the Legislature three days before the budget committees heard the agreement. Giving the Legislature such a constrained review period to review a proposal with such significant fiscal and policy implications is inappropriate. The public—including the members of the bargaining unit—also should have a greater opportunity to review the provisions of the agreement and provide input to the Legislature.

Budget Change Proposals of Far Smaller Size Would Require Justification From Administration, Legislative Deliberation, and Public Scrutiny. If ratified, the agreement will increase state costs by hundreds of millions of dollars each year. When budget proposals of far lesser value are submitted to the Legislature by the Governor during the budget process, they are subject to public and legislative review for a period of weeks or months, not days.

LAO Recommendations

Require Bargaining Cycle to Consider Legislative Calendar. The parties regularly submit labor agreements to the Legislature with a legislative deadline looming only days away. This is a long-standing problem and is not unique to this administration. In the case of this agreement, the parties reached agreement a week before the administration transmitted any documents to the Legislature—only days before the scheduled August 30 budget hearings. This time constraint is unnecessary. The legislative calendar is public and known far in advance. The legislative calendar and deadlines should be built into the administration’s planning such that the Legislature has sufficient time to consider labor agreements. As we have recommended in the past, we recommend that the Legislature adopt a standing policy to reject (1) any agreement that affects the compensation of state employees in the July pay period that is submitted to the Legislature after June 2 and (2) any agreement that is submitted to the Legislature fewer than two weeks before the end of session.