LAO Contact

March 30, 2023

Nonreporting Entities’

Information Security Compliance

- Introduction

- Background

- Assessment of Nonreporting Entities’ IS Compliance

- Options to Improve Nonreporting Entities’ IS Compliance and Maturity

- APPENDIX: Major Authorities Relevant to the Report

Executive Summary

Report Satisfies Supplemental Report Requirement. The Legislature adopted supplemental report language (SRL) in 2022 directing our office to publish a report on nonreporting entities’ information security (IS) compliance. (A nonreporting entity is a state entity that is not under the direct authority of the Governor and, therefore, generally is considered to be outside of the California Department of Technology’s [CDT’s] IS authority.) Specifically, the SRL required the report to identify each of the nonreporting entities, consider whether some of them could benefit from compliance with and reporting on IS policies and procedures similar to those set by CDT, and provide options for the Legislature to consider to improve nonreporting entities’ IS compliance and achieve a certain IS maturity level (that is, how prepared state entities’ IS programs are to prevent and/or respond to a cyberattack and/or threat). The publication of this report satisfies the requirements of the SRL.

Report Identifies 22 Nonreporting Entities Based on One Statutory Interpretation. Our office, in consultation with CDT, created a list of nonreporting entities based on one possible interpretation of state statute. We identified these entities based on specific definitions in statute, along with reviews of constitutional and statutory authorities for these entities. However, this list is not definitive or exhaustive as other statutory interpretations, such as a different interpretation of a state entity’s reporting relationship with the Governor, could add or remove an entity from the nonreporting entities list. These alternative statutory interpretations highlight a problematic ambiguity in state IS authority. Therefore, we recommend the Legislature amend statute to clearly identify which entities are nonreporting for the purposes of IS.

Chapter 773 of 2022 (AB 2135, Irwin) Addresses Some Compliance and Governance Issues Considered in SRL Report. Assembly Bill 2135 requires nonreporting entities to perform IS compliance and reporting activities similar to those required of reporting entities. These include using certain federal authorities for their policies, procedures, and standards; certifying compliance with IS requirements annually; and undergoing biennial independent security assessments. While some of the benefits and improvements in nonreporting entities’ IS compliance will depend on AB 2135 implementation, we consider some of the compliance and governance issues in the SRL to be addressed to a significant extent by AB 2135. The remainder of our report focuses on the results of our research on nonreporting entities’ IS programs across the three topics of IS governance, IS compliance, and IS/information technology infrastructure and staffing.

Evaluation of Nonreporting Entities’ IS Programs Presents Options to Improve Their Compliance and Maturity. The two figures below summarize (1) the findings of our analysis and (2) options for legislative action based on those findings. Our analysis included interviewing 34 entities (including 17 of 22 nonreporting entities); meeting with entities in the state’s IS governance structure; reviewing federal and state IS policies, procedures, and standards; and assessing nonreporting entity IS documentation.

Summary of Findings on Nonreporting Entities’ IS Programs

|

Topic |

Findings |

|

IS Governance |

Significant differences in nonreporting entity functions, roles, and size. |

|

Majority of nonreporting entities cited state IS policies, procedures, and standards as primary framework for IS programs. |

|

|

Many nonreporting entities receive and use threat intelligence information from Cal‑CSIC, but only some sought Cal‑CSIC and CDT’s guidance on Cal‑Secure implementation. |

|

|

Many nonreporting entities found CDT’s IS resources difficult to use. |

|

|

Some entities said statutory ambiguity impacted IS program decision‑making. |

|

|

IS Compliance |

Nearly all nonreporting entities underwent an ISA in the past several years. |

|

Some nonreporting entities voluntarily comply with state IS policies, procedures, and standards. |

|

|

Some nonreporting entities in voluntary compliance cited a lack of documentation review by CDT. |

|

|

Some nonreporting entities required to perform additional IS compliance activities by cyber insurance providers. |

|

|

Some nonreporting entities identified the lack of certification and education opportunities for existing staff to improve compliance. |

|

|

IS/IT Infrastructure and Staffing |

Several nonreporting entities use CDT IS and IT service offerings, but some nonreporting entities said private vendors offered better levels of service and pricing for IS and IT services. |

|

Nearly all nonreporting entities cited significant challenges hiring, training, and retaining IS staff. |

|

|

Smaller nonreporting entities raised concerns about procurement delays. |

Summary of Options to Improve Nonreporting Entities’ IS Compliance and Maturity

|

Topic |

Options |

|

IS Governance |

Consider amending CDT’s IS authority to address statutory ambiguity of state agency and state entity definitions and use. |

|

Recommend monitoring nonreporting entities’ compliance with and implementation of AB 2135.a |

|

|

Consider directing CDT to improve ease of use of IS‑related guidance, information, and templates. |

|

|

Consider directing Cal‑CSIC to increase outreach to nonreporting entities implementing Cal‑Secure. |

|

|

IS Compliance |

Consider opportunities to condition state funding on compliance with federal and state IS policies, procedures, and standards. |

|

Consider directing Cal‑CSIC and CDT to report to the Legislature on Cal‑Secure implementation. |

|

|

Consider requiring CDT to develop centralized IS training hub for IS compliance certification and education. |

|

|

Consider requiring an evaluation of major cyber insurance products to understand compliance requirements. |

|

|

IS/IT Infrastructure and Staffing |

Consider expanding use of shared service contracts for IS services. |

|

Consider directing administration to expand on existing recruitment, training, and retention efforts to increase size of IS workforce. |

|

|

Consider monitoring State Data Center rate reassessment process for IT services. |

|

|

Consider mandating certain network traffic be directed to CDT’s SOC for monitoring. |

|

|

Consider directing administration to evaluate division of IT procurement responsibilities. |

|

|

aChapter 773 of 2022 (AB 2135, Irwin). |

|

|

IS = information security; Cal‑CSIC = California Cybersecurity Integration Center; CDT = California Department of Technology; ISA = independent security assessment; IT = information technology; and SOC = Security Operations Center. |

|

Introduction

Report Satisfies Supplemental Report Requirement. The Legislature adopted supplemental report language (SRL) in 2022 directing our office to publish a report on nonreporting entities’ information security (IS) compliance. (We define nonreporting entities and provide more information on IS compliance in the “Background” section.) Specifically, the SRL required the report to, at a minimum, identify each of the nonreporting entities, consider whether some of them could benefit from compliance with and reporting on IS policies and procedures similar to those set by the California Department of Technology (CDT), and provide options for the Legislature to consider to improve nonreporting entities’ IS compliance to be comparable with reporting entities and achieve a certain IS maturity level. The publication of this report satisfies the requirements of the SRL.

Report Maintains Confidentiality of Information as Required by State Law. The SRL also required our office to maintain the confidentiality of the information collected from nonreporting entities in compliance with state law. For example, Government Code Section 7929.210 limits disclosure of state IS documents if their disclosure “would reveal vulnerabilities to, or otherwise increase the potential for an attack on,” state information technology (IT) systems. In addition, Government Code Section 8592.45 prohibits disclosure of state IS information on critical infrastructure IT systems. This report complies with state law and the SRL requirement, as well as legal and policy guidance from CDT on publication of the list of nonreporting entities.

Background

In this section, we provide definitions for terms we use throughout the report, specifically nonreporting and reporting entities, and relevant background information across three different topics—IS governance, IS compliance, and IS/IT infrastructure and staffing.

Definitions of Nonreporting and Reporting Entities. A nonreporting entity is a state entity that is not under the direct authority of the Governor and, therefore, generally is considered to be outside of CDT’s IS authority. In contrast, a reporting entity is under the direct authority of the Governor, is subject to CDT’s IS authority and, therefore, is directed by CDT to manage risk and security according to its policies, procedures, and standards. The distinction between entities based on their reporting relationship with the Governor comes from interpretations of different statutory definitions in CDT’s IS authority—that is, the definition of “state agency” (Government Code Sections 11000 and 11546.1[e][1]) and “state entity” (Government Code Section 11546.1[e][2]). Whereas one definition of state agency applies to all executive branch entities, including nonreporting entities, the two other definitions of state agency and state entity within CDT’s IS authority list specific agencies and types of entities subject to their authority that is narrower than the preceding definition of state agency. In the “Major Authorities” appendix on pages 21‑23 of the report, we provide more information about these statutory definitions as well as other IS‑related authorities that are relevant to this report.

IS Governance

Definition of IS Governance. In this report, we define IS governance as the structure that is responsible for the coordination of statewide cybersecurity strategy and development of state IS policies, procedures, and standards. Key entities in the state’s IS governance structure that are relevant to this report include the California Cybersecurity Integration Center (Cal‑CSIC) and CDT’s Office of Information Security (OIS). We acknowledge that there are other entities, such as federal entities and industry organizations, involved in IS governance. While the focus of our IS governance section is on the state’s IS governance structure, we will discuss other entities’ roles in IS governance as needed in the report.

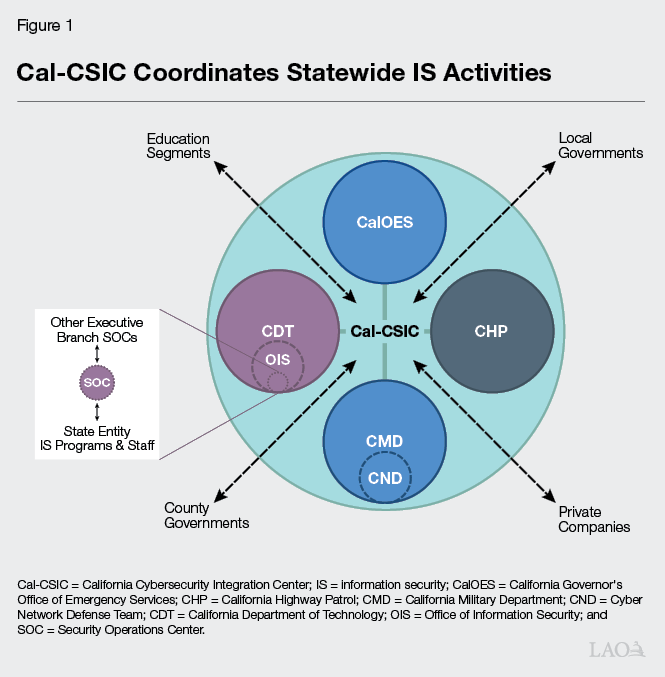

Cal‑CSIC Provides Statewide IS Leadership. Cal‑CSIC is the lead entity for coordinating statewide IS activities; gathering and disseminating threat intelligence to state entities from the federal government, county and other local governments, and private companies; and responding to cybersecurity incidents. Cal‑CSIC is a partnership of four state entities: the California Governor’s Office of Emergency Services, which administers Cal‑CSIC; CDT; the California Highway Patrol; and the California Military Department (CMD). Figure 1 provides a graphical representation of Cal‑CSIC and its partners.

OIS Sets Policies, Procedures, and Standards for Reporting Entities. OIS is responsible for the creation of IS policies, procedures, and standards that reporting entities must follow. OIS formalizes IS policies, procedures, and standards in the State Administrative Manual (SAM) and Statewide Information Management Manual (SIMM). Nearly all of the IS sections in SAM and SIMM use Federal Information Processing Standards (FIPS) and/or National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) Special Publication (SP) 800‑53 as their sources for the state’s policies, procedures, and standards. More information about the IS sections of SAM and SIMM, FIPS, and NIST SP 800‑53 is provided in the “Major Authorities” appendix on pages 21‑23 of the report.

Cal‑CSIC and OIS Work Together on Implementation of State’s Multiyear IS Roadmap. OIS, in collaboration with other Cal‑CSIC partners, published the state’s first five‑year IS roadmap—referred to as Cal‑Secure—in October 2021. The administration’s intent is for the roadmap to prioritize reporting entities’ cybersecurity initiatives and technical capability investments over the next five years. Nonreporting entities also can voluntarily opt into Cal‑Secure implementation. State entities have begun requesting additional funding and/or positions to acquire capabilities and lead initiatives (as identified by the roadmap). Our understanding is that there are no reporting requirements specific to Cal‑Secure; rather, reporting entities will report to CDT OIS on Cal‑Secure progress as part of their routine reporting requirements, and nonreporting entities will not report their progress. More information about Cal‑Secure is provided in the “Major Authorities” appendix on pages 21‑23 of the report.

Nonreporting Entities’ IS Governance Varies. Historically, nonreporting entities generally have not been subject to the state’s IS governance structure. There have been exceptions, however. For example, nonreporting entities are required to submit technology recovery plans for critical infrastructure controls and information to CDT pursuant to Government Code Section 8592.35. Also, pursuant to Government Code Section 8586.5, some nonreporting entities are represented within Cal‑CSIC such as the Department of Justice. In addition, a number of nonreporting entities are governed by other federal entities and industry organizations and, therefore, are subject to their specific IS policies, procedures, and standards.

Recently Enacted Legislation Provides Some IS‑Related Requirements for Nonreporting Entities and Adds Legislature to State’s IS Governance Structure. Chapter 773 of 2022 (AB 2135, Irwin) requires nonreporting entities to use FIPS 199; FIPS 200; and NIST SP 800‑53, Revision 5 (and all of their successor publications) as sources for their IS policies, procedures, and standards. These sources largely are the same sources for the IS sections of SAM and SIMM which contain the policies, procedures, and standards that reporting entities must follow. However, unlike reporting entities, nonreporting entities must annually certify their compliance with legislative leadership. (We discuss the compliance certification processes for nonreporting and reporting entities in more detail in the “IS Compliance” section immediately below.) Therefore, AB 2135 added the Legislature to the state’s IS governance structure specifically for nonreporting entities. More information about AB 2135 and its amendments to Government Code Section 11549.3 is provided in the “Major Authorities” appendix on pages 21‑23 of the report.

IS Compliance

Definition of IS Compliance. In this report, we define IS compliance as the mechanisms within the IS governance structure that are used to oversee state entities’ implementation of IS policies, procedures, and standards, and ensure remediation of assessment and audit findings. We again acknowledge that there may be other entities involved in nonreporting entities’ IS compliance, but we focus our IS compliance section on the state’s IS compliance requirements.

OIS Enforces Reporting Entity IS Compliance. OIS requires all reporting entities to submit annual IS compliance documentation. Two important compliance documents are (1) the IS and privacy program compliance certification, and (2) the risk register and plan of action and milestones (POAM). A compliance certification attests that a reporting entity is compliant with the policies, procedures, and standards in the IS sections of SAM and SIMM. A risk register and POAM identifies a reporting entity’s deficiencies and risks, and explains to OIS how those deficiencies and risks are being addressed and/or mitigated. Unlike compliance certifications, which are annually submitted, OIS requests quarterly updates on risk registers and POAMs. More information about the relevant SIMM sections for compliance certifications and risk registers and POAMs is provided in the “Major Authorities” appendix on pages 21‑23 of the report.

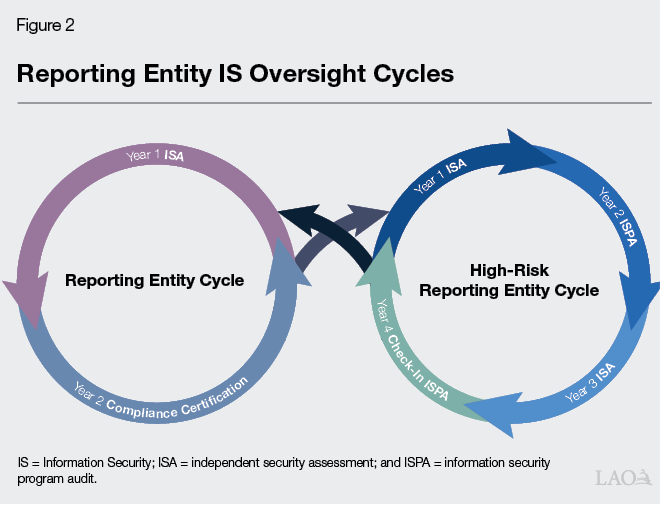

Independent Security Assessments (ISAs) and IS Program Audits (ISPAs) Used by OIS to Oversee Reporting Entity Compliance... In addition to the annual IS compliance documentation, OIS uses two other primary mechanisms to oversee IS compliance: ISAs and ISPAs. ISAs are technical analyses of an entity’s cybersecurity defenses that assess whether both networks and systems are configured to prevent attacks. These analyses simulate attacks to see whether networks and systems can be compromised and data modified and/or stolen. ISAs of reporting entities typically are performed by CMD, but can be performed by third‑party vendors with OIS approval. ISPAs instead first review an entity’s IS policies, procedures, and standards, and then interview staff and test networks and systems to assess whether practice matches IS requirements under the authorities that apply to that entity. ISPAs typically are performed by OIS.

…But Frequency of ISPAs Based on OIS’ Determination of Reporting Entity’s Risk. ISAs are required for all reporting entities every two years (with limited exceptions). However, CDT cannot perform ISPAs for all reporting entities due to a lack of resources. To prioritize ISPAs, OIS uses specific criteria (such as the sensitivity of the data maintained by an entity) to decide whether reporting entities are high risk. Based on the criteria, OIS currently identifies 52 reporting entities as high risk. OIS requires that high‑risk reporting entities complete ISAs and ISPAs in alternating years. Reporting entities that are not determined by OIS to be high risk can annually certify their IS practice matches authorities in place of an ISPA (though an ISPA may be requested by OIS at some point). Figure 2 provides a visual representation of these oversight cycles based on OIS’ determination of reporting entities’ level of risk.

Nonreporting Entities’ IS Compliance Requirements Vary. Nonreporting entities largely are not subject to the state’s IS compliance requirements under state law, except as directed under AB 2135 and discussed in more detail below. However, as discussed above, nonreporting entities have been required in the past to submit at least some IS compliance documentation (such as technology recovery plans) to CDT. Nonreporting entities also might be governed by other federal entities and industry organizations that require periodic IS assessments and audits, some of which are similar to state ISAs and ISPAs. Some of the larger nonreporting entities also might purchase cyber insurance coverage, which might require entities to undergo periodic IS assessments and audits to maintain their policies. Guidance and information on cyber insurance providers and their IS compliance requirements may be provided to state entities by, for example, the Department of General Services’ (DGS’) Office of Risk and Insurance Management (OIRM).

AB 2135 Requires Nonreporting Entities to Submit IS Compliance Documentation to Legislature. Assembly Bill 2135 requires nonreporting entities to certify their compliance with FIPS 199; FIPS 200; and NIST SP 800‑53, Revision 5 (and all of their successor publications) annually to legislative leadership. To certify compliance, nonreporting entities must submit some of the same IS compliance documentation to legislative leadership as reporting entities submit to CDT—that is, the IS and privacy program compliance certification and the POAM. Unlike reporting entities, however, nonreporting entities do not need to submit quarterly updates on their POAMs and the information requested in the POAM (an older template) is slightly less comprehensive than in the current POAM used by reporting entities.

IS/IT Infrastructure and Staffing

Definition of IS/IT Infrastructure and Staffing. In this report, we define IS/IT infrastructure and staffing as the IT processes, services, systems, and staff that support state IS programs. We focus on certain processes such as the division of IT procurement responsibilities between CDT and DGS; certain services and systems such as CDT’s statewide and shared service contracts (that is, consolidated contracts for IT services managed by CDT and offered to multiple state entities), Security Operations Center (SOC), and State Data Center; and, certain staff‑related issues such as Cal‑CSIC incident response staff, IT staff classifications, and IS staff recruitment and training efforts.

Cal‑CSIC Staff Provides Statewide Incident Response. Cal‑CSIC staff support IS and IT staff at state entities (along with other entities statewide) to respond to cybersecurity incidents and data breaches. State entities also can submit requests for assistance to Cal‑CSIC if there are attacks and/or threats identified by entities’ IS and IT staff that need remediation. The level of response from Cal‑CSIC staff varies based on the severity of the data breach and/or incident, and on the other IS resources available to the state entity. For example, Cal‑CSIC might respond to a serious data breach and/or incident with the whole of its incident response team and request that additional IS and IT staff, as well as subject matter experts, from the affected entity also respond. Lower‑severity data breaches and/or incidents might only require a few Cal‑CSIC staff, and rely more on internal entity IS and IT staff for incident response and remediation efforts.

CDT Operates the State SOC and State Data Center. CDT operates the state SOC, which continuously monitors and reacts to threats on the California Government Enterprise Network (CGEN), the state government’s primary enterprise network. Many reporting entities connect to CGEN, which allows CDT’s SOC to identify and respond more quickly to attacks and/or threats to these entities. CDT’s SOC also transmits any information about attacks and/or threats to Cal‑CSIC to determine if, for example, education segments, other government entities, and/or private companies are responding to similar attacks and/or threats. CDT also maintains the State Data Center, which hosts a number of state entities’ IT infrastructure (including some of the nonreporting entities’ applications and systems) and monitors it for attacks and/or threats.

CDT Also Procures and Manages Statewide and Shared Service Contracts, Including for IS. CDT also procures and manages both statewide and shared service contracts for state entities, including a small number of IS‑related contracts. Statewide contracts managed by CDT allow vendor‑hosted subscription services—IT services provided and primarily supported by private vendors—used by most state entities to be provided to all entities at a lower cost than they might be able to negotiate with vendors as individual entities. One example of a statewide contract is the state’s Microsoft 365 contract. Shared service contracts managed by CDT also allow for certain IT services to be provided, but typically are for a smaller number of state entities using a specific type of service to reduce their current expenditures on similar services. One example of a shared service contract is security information and event management software that provides a group of state entities with several capabilities prioritized in Cal‑Secure.

Shared IT Procurement Process Responsibilities Between CDT and DGS. Public Contract Code Sections 12100‑12113 divide state IT procurement process responsibilities between CDT and DGS. CDT is responsible for contracts for IT goods and services related to IT projects (that is, a set of activities required to plan, develop, and implement an IT system) as well as telecommunications goods and services, while DGS is responsible for contracts for all other IT goods and services (such as the replacement of computers, mobile devices, and other hardware). Authority over state IT procurement policy and procedures also is divided between CDT and DGS based on their separate responsibilities. More information on Public Contract Code Sections 12100‑12113 is provided in the “Major Authorities” appendix on pages 21‑23 of the report.

State Entities Hire IS and IT Staff Using Consolidated IT Classifications Approved in 2018. In 2018, the State Personnel Board approved the consolidation of 36 IT classifications into nine new classifications to be used to hire both IS and IT staff across state entities. Six IS and IT functional areas are used to further specify workload for these positions, including IS engineering and system engineering, but there are no IT classifications specific to IS.

State Engaged in Number of Efforts to Recruit and Train IS Staff. Cal‑CSIC and CDT—in collaboration with the California Department of Human Resources (CalHR), the Government Operations Agency (GovOps), and other state entities—have set up several programs to recruit and train IS staff to work in state entities. For example, the IT Cybersecurity Non‑Traditional Apprenticeship Program began in September 2021 to train current non‑IS state staff for up to two years to qualify for IS staff positions. Also, the Work for California campaign launched in 2023 specifically recruits recently laid off IS and IT workers at private companies on behalf of state entities. State entities also recruit from colleges and universities and, in some cases, set up programs in collaboration with colleges and universities to recruit and train future IS and IT staff for state entities. Finally, CDT’s Office of Professional Development and Training Center works with the department’s OIS on centralized and subscription‑based IS training.

Nonreporting Entities’ IS/IT Infrastructure and Staff Varies. Generally, unlike reporting entities, nonreporting entities are not required to use specific IS/IT infrastructure and staff under state law. A number of nonreporting entities choose to use CDT’s SOC, host at least some of their IT applications and systems on the State Data Center, and use services provided through both statewide and shared service contracts procured and managed by CDT. Other nonreporting entities, however, maintain their own IS and IT infrastructure to meet industry‑ or program area‑specific needs and/or to ensure their independence from entities under the direct authority of the Governor.

Assessment of Nonreporting Entities’ IS Compliance

The first portion of this section lays out our research methodology. We then discuss how nonreporting entities are defined for the purposes of this report and recent effects of AB 2135 on IS programs. Lastly, we provide our evaluation of nonreporting entities’ IS programs.

Research Methodology

Interviews With Nonreporting Entities’ IS Programs. Our office conducted a total of 34 one‑hour interviews, primarily with staff of nonreporting entities’ IS programs. We asked a standardized set of interview questions about IS governance, IS compliance, and IS/IT infrastructure and staffing to code nonreporting entities’ responses. Out of the 22 entities we identified as nonreporting entities (which we provide later in the report), our office interviewed 17 nonreporting entities. We did not interview some of the remaining five entities primarily because these were entities where their IT infrastructure is hosted by other entities (some of which we interviewed) or they have no IT infrastructure. A few entities, however, did not respond to our requests for an interview. We also scheduled an additional 12 interviews with reporting entities and entities outside of the executive branch.

Meetings With Entities in State’s IS Governance Structure. Our office also held several meetings with Cal‑CSIC, OIS, and CMD. We discussed a number of topics including possible definitions for nonreporting entities (including the one used for the nonreporting entities list in this report), their understanding of nonreporting entities’ IS governance and compliance activities, and their IS/IT infrastructure and staff training offerings for state entities. We also held meetings with the Department of Finance (DOF) to discuss their analysis of IS‑related budget proposals from nonreporting entities.

Review of Nonreporting Entities’ IS Documentation. Our office requested IS governance and compliance documentation from nonreporting entities in advance of the interviews. Some examples of the documentation we requested included a list of the IS assessments and audits performed over the last five years; all of their IS policies, procedures, and standards; and recent IS and IT budgets with position information. We reviewed this documentation to inform our questions during the interviews and our analysis in this report. Any confidential information that was contained in this documentation was maintained in a manner consistent with the relevant Government Code sections and SRL requirement described in the “Introduction” section.

Review of Federal and State IS Authorities and Literature. We reviewed federal and state IS policies, procedures, and standards, including those in the “Major Authorities” appendix. We also reviewed available literature on specific topics related to the report, such as specific compliance requirements in certain critical infrastructure sectors.

Identification of Nonreporting Entities

One Statutory Interpretation Used in Report to Create Nonreporting Entities List… In consultation with CDT, we created a list of nonreporting entities based on one possible interpretation of state statute. First, we identified entities based on the broad definition of state agency in Government Code Section 11000. (There are narrower definitions in other code provisions.) Then, we identified which of those entities are not under the direct authority of the Governor and, therefore, would not be defined as state entities under Government Code Section 11546.1(e)(2). Our determination as to the reporting relationship with the Governor required, for example, a review of the constitutional and statutory authorities governing these entities. This list is provided below in Figure 3 as the list of nonreporting entities requested in the SRL. The publication of this list conforms with legal and policy guidance from CDT.

Figure 3

Nonreporting Entities Based on

One Statutory Interpretation

|

Board of Equalization |

|

Citizens Compensation Commission |

|

Commission on Peace Officer Standards and Training |

|

Commission on State Mandates |

|

Department of Education (Superintendent of Public Instruction) |

|

Department of Insurance (Insurance Commissioner) |

|

Department of Justice (Attorney General) |

|

Education Audit Appeals Panel |

|

Gambling Control Commission |

|

Health Benefit Exchange (Covered California) |

|

Little Hoover Commission |

|

Office of Tax Appeals |

|

Office of the Inspector General |

|

Office of the Lieutenant Governor |

|

Privacy Protection Agency |

|

Public Utilities Commission |

|

Secretary of State |

|

State Auditor |

|

State Controller |

|

State Lottery |

|

State Treasurer |

|

Summer School for the Arts |

…But Other Statutory Interpretations Could Change List of Nonreporting Entities. The list of nonreporting entities in this report is based on one statutory interpretation used to identify entities that are not under the direct authority of the Governor and, therefore, generally are considered to be outside of CDT’s IS authority. This list is not definitive or exhaustive. For example, we removed those entities for which we could not determine the exact reporting relationship with the Governor (such as independent entities in statute that are organized under state agencies identified in Government Code Section 11546.1[e][1] in order to focus solely on those nonreporting entities clearly covered by the SRL. In contrast, CDT identified some of the entities on the list as “voluntarily complying” with state IS policies, procedures, and standards. We kept these entities on the list because of potential noncompliance in the future. We acknowledge alternative approaches would result in differences with our list. As we describe below, we recommend the Legislature amend statute to clarify both the definitions and use of state agency and state entity in order to clarify CDT’s IS authority.

Impacts of AB 2135 on IS Programs

AB 2135 Requires Nonreporting Entities to Follow Federal IS Authorities and Undergo ISAs Much Like Reporting Entities. Assembly Bill 2135 requires nonreporting entities to use certain FIPS and NIST SP 800‑53, Revision 5 (and all of their successor publications) as sources for their IS policies, procedures, and standards. These sources largely are the same sources for the IS sections of SAM and SIMM which contain the policies, procedures, and standards that reporting entities must follow. Assembly Bill 2135 also requires nonreporting entities to certify compliance with their IS policies, procedures, and standards to legislative leadership annually. To certify compliance, nonreporting entities must submit some of the same IS compliance documentation to legislative leadership as reporting entities submit to CDT—that is, the IS and privacy program compliance certification and the POAM.

AB 2135 Addresses Some Governance and Compliance Issues That SRL Asked Us to Consider. The SRL asked our office to consider whether some of the nonreporting entities could benefit from compliance with and reporting on IS policies and procedures similar to those set by CDT, and to provide options for the Legislature to consider to improve nonreporting entities’ compliance to be comparable with reporting entities and achieve a certain IS maturity level. (An entity’s IS maturity level is how prepared state entities’ IS programs are to prevent and/or respond to a cyberattack and/or threat.) We find that some of the governance and compliance issues raised in the SRL are addressed by AB 2135. For example, federal IS authorities that nonreporting entities must follow under AB 2135 are similar to those set by CDT, and the reporting on their compliance with those authorities to legislative leadership is similar to what is required by CDT (with the exception of annual POAM updates to the Legislature instead of quarterly updates required by CDT for reporting entities). Also, the biennial ISAs required by AB 2135 for nonreporting entities are completed by CMD or third‑party vendors in much the same way as for reporting entities, thereby helping nonreporting entities to improve their IS compliance and increase their IS maturity level. Figure 4 shows how specific IS compliance requirements for nonreporting and reporting entities compare after enactment of AB 2135.

Figure 4

Comparison of Entities’ Specific IS Compliance Requirements After Enactment of AB 2135a

|

IS Compliance Requirement |

Reporting Entities |

Nonreporting Entitiesb |

|

Primary Governing Statutory Authoritiesc |

SAM and SIMM sections 5300 (largely using FIPS and NIST SP 800‑53 as the sources for their policies, procedures, and standards). |

FIPS 199, FIPS 200, and NIST SP 800‑53. Nonreporting entities also may choose to voluntarily adopt reporting entities’ primary governing statutory authorities. |

|

Assessments and Audits |

Biennial ISAs by CMD, and biennial ISPAs for high‑risk reporting entities. ISAs also can be completed by a third‑party vendor, if approved by CDT. |

Biennial ISAs and as‑needed ISPAs from CDT. ISAs may be completed by CMD or a third‑party vendor. |

|

Compliance Certification and Reporting |

Submission of annual compliance certifications and other IS compliance documentation (such as POAMs) to CDT. POAMs must be updated quarterly. |

Submission of annual compliance certifications and POAMs to legislative leadership. |

|

aChapter 773 of 2022 (AB 2135, Irwin). bNonreporting entities subject to these requirements might depend on which statutory interpretation is used for the definitions of “state agency” and “state entity” in CDT’s IS authority. cFor more information on the governing statutory authorities we reference in this figure, please refer to the “Major Authorities” appendix at the end of the report. |

||

|

IS = information security; SAM = State Administrative Manual; SIMM = Statewide Information Management Manual; FIPS = Federal Information Processing Standards; NIST = National Institute for Standards and Technology; SP = Special Publication; ISAs = independent security assessments; CMD = California Military Department; ISPAs = information security program audits; CDT = California Department of Technology; and POAM = plan of action and milestones. |

||

Assembly Bill 2135, when fully implemented, likely will provide increased oversight of nonreporting entities that, while not required by state law to follow IS requirements set by OIS, are state government entities largely funded with appropriations approved by the Legislature. We find it is important, therefore, that these entities be subject to some of the same accountability for and governance of their IS programs as reporting entities.

Remainder of Assessment and Options Consider Other Issues Affecting Nonreporting Entities’ Compliance and Maturity. Therefore, in light of AB 2135, the remainder of our assessment focuses on the results of our research on nonreporting entities’ IS programs across the topics of IS compliance, IS governance, and IS/IT infrastructure and staffing. Similarly, the options we provide in our report focus on issues and needs identified in our research that have not already been addressed in AB 2135, but could improve nonreporting entities’ IS compliance and maturity.

Evaluation of Nonreporting Entities’ IS Programs

To protect the confidentiality of the information received from nonreporting entities through our documentation review and interviews, we use descriptive language to summarize our review and their responses rather than naming entities and providing the number of responses from nonreporting entities that apply to each finding.

IS Governance

Significant Differences in Nonreporting Entity Functions, Roles, and Size. The term nonreporting entity might be useful when considering whether or not an entity is considered to be outside of CDT’s IS authority but the term does not identify the relative risk for these entities. Moreover, in light of AB 2135, the term is less helpful when considering if there are benefits from additional compliance and reporting requirements or other resources to improve such an entity’s IS compliance and maturity. There are significant differences, for example, in the types of programs and services each nonreporting entity provides, in the roles they serve on behalf of the state, and in the size of their budgets and staff. To illustrate these differences in terms of the latter, Figure 5 provides the total fund budgets and number of positions approved for these entities in the 2022‑23 Budget Act, sorted from largest to smallest budgets.

Figure 5

Budgets and Positions at Nonreporting Entities in 2022‑23 Budget Act

|

Nonreporting Entities |

Total Funds |

Positions |

|

Public Utilities Commission |

$1,889,094 |

1,501 |

|

Department of Justice (Attorney General) |

1,166,144 |

5,791 |

|

State Lottery |

1,110,199 |

1,080 |

|

Health Benefit Exchange (Covered California) |

759,469 |

1,465 |

|

State Controller |

361,530 |

1,591 |

|

Department of Insurance (Insurance Commissioner) |

325,698 |

1,400 |

|

Gambling Control Commission |

154,717 |

40 |

|

Secretary of State |

152,396 |

592 |

|

Department of Education (Superintendent of Public Instruction) |

110,267 |

2,566 |

|

Commission on Peace Officer Standards and Training |

110,166 |

263 |

|

Commission on State Mandates |

71,876 |

17 |

|

State Auditor |

46,752 |

217 |

|

State Treasurer |

46,360 |

252 |

|

Office of the Inspector General |

42,275 |

214 |

|

Board of Equalization |

32,563 |

194 |

|

Office of Tax Appeals |

27,138 |

117 |

|

Privacy Protection Agency |

10,000 |

34 |

|

Summer School for the Arts |

4,273 |

4 |

|

Office of the Lieutenant Governor |

2,708 |

15 |

|

Little Hoover Commission |

1,292 |

7 |

|

Education Audit Appeals Panel |

1,177 |

5 |

|

Citizens Compensation Commission |

10 |

— |

This figure shows that while some nonreporting entities receive hundreds of millions of dollars and employ thousands of staff, others receive millions of dollars or less and employ few (if any) staff. Furthermore, the roles of some entities (for example, some of the constitutional officers) are critical to the performance of certain state functions (for example, accounting and cash management) whereas other entities, while serving important oversight functions, do not perform central state functions and roles. Therefore, the findings and options in this report generally cannot be applied across all nonreporting entities. In many cases, our findings and options are specific to a subset of nonreporting entities based on their functions, roles, and size.

Majority of Nonreporting Entities Cited State IS Policies, Procedures, and Standards as Primary Framework for IS Programs. A majority of the nonreporting entities we interviewed either provided documentation showing, or confirmed in their responses, that SAM and SIMM Sections 5300 as well as NIST SP 800‑53 are the principal authorities for their own IS policies, procedures, and standards. If these were not their principal authorities because, for example, they adopted other federal or industry IS authorities as their primary framework, some entities still cross‑referenced the policies, procedures, and standards they adopted with SAM and SIMM Sections 5300 and/or NIST SP 800‑53. Some nonreporting entities were required to adopt other authorities specific to their programs and services that, in many cases, were more prescriptive than state authorities. Many nonreporting entities also cited Cal‑Secure as guiding their cybersecurity initiatives and technical capability investments. Altogether, these findings indicate nonreporting entities’ significant adoption and awareness of state IS policies, procedures, and standards.

Many Nonreporting Entities Receive and Use Threat Intelligence Information From Cal‑CSIC… Many of the nonreporting entities we interviewed mentioned that they receive and use threat intelligence information from Cal‑CSIC to, for example, block malicious Internet Protocol addresses—that is, unique identifiers associated with internet or network devices engaged in hacking attempts or spamming activities—and monitor their networks for known threat actors—that is, organizations or people known to engage in cyberattacks. Therefore, even though nonreporting entities are not governed by the state’s IS governance system, many of them are taking advantage of resources from the state’s IS governance entities.

…But Only Some Sought Cal‑CSIC and CDT’s Guidance on Cal‑Secure Implementation. Although many nonreporting entities cited Cal‑Secure as one of the frameworks guiding their cybersecurity initiatives and technical capability implementations, only some of them said in their interviews that they actively sought guidance from Cal‑CSIC and CDT on Cal‑Secure. Some of the entities may not have included their consultation with Cal‑CSIC and CDT in their responses to us, but to some degree, nonreporting entities may be using Cal‑Secure without much guidance from Cal‑CSIC and CDT to inform their implementation of the roadmap.

Many Nonreporting Entities Found CDT’s IS Resources Difficult to Use. A majority of the nonreporting entities that use SAM and SIMM Sections 5300 and/or NIST SP 800‑53 as principal authorities for their IS programs said they found implementation of the framework to be difficult because guidance, information, and templates made available by CDT were hard to understand and not necessarily relevant to their program areas. We understand from CDT that some of the guidance, information, and templates are intentionally general to allow a wider range of state entities to use them, but some nonreporting entities considered the lack of specificity in CDT’s documentation to be problematic. A number of nonreporting entities also found CDT’s recommendations on hardware, software, and/or tools to implement state IS policies, procedures, and standards to be too expensive and/or too limited given their constrained IS budgets. In sum, while a majority of nonreporting entities adopt and/or are aware of state IS policies, procedures, and standards, many of these entities struggle to implement them based on current supporting materials from CDT.

Some Entities Said Statutory Ambiguity Impacted IS Program Decision‑Making. Some entities we interviewed were not able to provide definitive answers to our questions about their reporting relationship with the Governor and, thus, were unsure if they were nonreporting entities. Some of them had communicated with Cal‑CSIC and CDT to clarify whether or not they are nonreporting entities, but a number of them told us they were unable to resolve this uncertainty. Some said the ambiguity in statute about their status made their decisions on IS governance and, by extension, compliance more difficult. We find the inability of some entities to determine whether or not they are nonreporting entities because of the ambiguities in CDT’s IS authority to be problematic as it leaves oversight of these entities in limbo. Furthermore, it could affect the implementation of AB 2135, limiting the accountability for and governance of state government entities largely funded with appropriations approved by the Legislature.

IS Compliance

Nearly All Nonreporting Entities Underwent an ISA in the Past Several Years. According to our documentation review, and verified by entities’ responses to our interview questions, we found that nearly all nonreporting entities underwent an ISA in the past two to three years. Some of the nonreporting entities did wait several years between ISAs, citing difficulty obtaining funding for an ISA every two years. However, for larger nonreporting entities, biennial ISAs were only one of several IS assessments and audits undertaken, some of which were required by federal authorities, industry organizations, and some cyber insurance providers. A number of nonreporting entities cited AB 2135, as of 2022, as a reason for their decision to undergo an ISA. Consistent with CDT’s requirement that reporting entities undergo ISAs once every two years (with some limited exceptions), nonreporting entities appear to be undergoing ISAs at a comparable rate consistent with the intent of AB 2135.

Some Nonreporting Entities Voluntarily Comply With State IS Policies, Procedures, and Standards. As mentioned earlier, some nonreporting entities voluntarily choose to comply with state IS policies, procedures, and standards. Voluntary compliance means these entities undergo ISAs and ISPAs (if deemed high risk) and submit IS compliance documentation to OIS just as reporting entities do. However, unlike reporting entities, nonreporting entities can choose to stop their compliance with state IS policies, procedures, and standards at any time. None of the nonreporting entities we interviewed indicated they would stop their voluntary compliance. Some did mention, however, that they decided internally to fully adopt some state policies and standards but modify others because, for example, their alternative approach to implementation was not explicitly allowed or their budgets could not cover full implementation of a state policy or standard. Therefore, voluntary compliance shows nonreporting entities’ willingness to follow state IS policies, procedures, and standards, but does not guarantee full compliance.

Some Nonreporting Entities in Voluntary Compliance Cited a Lack of Documentation Review by CDT. A small number of nonreporting entities that are in voluntary compliance with state IS policies, procedures, and standards submitted IS compliance documentation with CDT, but received little to no feedback on their submissions. These entities said the lack of response from CDT made it difficult to, for example, determine whether deficiencies identified in ISAs had been addressed consistent with state authorities and guidance. As a result, some of these entities might not be able to verify that their IS compliance and maturity is improving due to a lack of responsiveness from CDT. If some nonreporting entities decide in the future to consider voluntary compliance with state IS requirements, this lack of response also might discourage them from agreeing to continue with voluntary compliance.

Some Nonreporting Entities Required to Perform Additional IS Compliance Activities by Cyber Insurance Providers. Some nonreporting entities we interviewed said several of their IS compliance activities were required by their cyber insurance providers to maintain their policies, including certain IS assessments and audits like ISAs. A small number mentioned they had to adopt certain IS policies, procedures, and standards as well, and certify their compliance with particular requirements that were set by their cyber insurance providers. While cyber insurance providers are not a formal part of the state’s IS governance structure, it appears that, at least for some nonreporting entities, cyber insurance providers play a key role in their decisions to engage in certain IS compliance activities.

Some Nonreporting Entities Identified the Lack of Certification and Education Opportunities for Existing Staff to Improve Compliance. Some nonreporting entities were unaware of how to achieve compliance with state IS policies, procedures, and standards, and requested that CDT provide certification and education opportunities to help existing IS and IT staff learn how to improve their compliance efforts and train others. A small number of entities sought external training on some authorities that inform the state’s framework (for example, NIST SP 800‑53) to help them with state IS compliance activities, but said external training was not always tailored to state IS policies, procedures, and standards. We identify other staff training‑related findings from our research under the “IS/IT Infrastructure and Staffing” topic in the next section, but found the request for official certification of compliance knowledge from CDT to be noteworthy.

IS/IT Infrastructure and Staffing

Several Nonreporting Entities Use CDT IS and IT Service Offerings... According to CDT, several nonreporting entities use some combination of the department’s SOC and State Data Center IT services. Some entities connect to CGEN, for example, and/or host specific applications and/or systems on the State Data Center. Other nonreporting entities decided on more novel approaches to working with CDT’s SOC. For example, at least one nonreporting entity directed a portion of its network traffic to the department’s SOC, while maintaining their own separate entity SOC for internal network traffic. We understand from CDT that nonreporting entities’ use of its SOC and State Data Center gives the department more visibility into nonreporting entities’ IS activities and, consequently, allows CDT to help these entities improve their IS compliance and maturity.

…But Some Nonreporting Entities Said Private Vendors Offered Better Levels of Service and Pricing for IS and IT Services. While some nonreporting entities cited an interest in CDT’s SOC and State Data Center IT service offerings, these entities decided that their contracts with private vendors offered comparable or better levels of service and pricing. While we were not able to compare service contracts and rates in our research, it seems at least possible based on our assessment of certain budget proposals related to the State Data Center that rates for some IT services offered by CDT are not competitive with private vendor rates.

Nearly All Nonreporting Entities Cited Significant Challenges Hiring, Training, and Retaining IS Staff. In nearly every one of our interviews with nonreporting entities, entities expressed difficulty recruiting, training, and retaining IS staff. Several entities described their efforts to improve staff recruitment, training, and retention, but these efforts achieved mixed results. Some examples of these efforts included the aforementioned IT Cybersecurity Non‑Traditional Apprenticeship Program, similar internal entity apprenticeships to retrain existing staff into IS staff, college outreach to create pipelines from IS‑related degree programs into nonreporting entity IS offices, and internship and student assistant programs.

Many nonreporting entities used cybersecurity training software offerings to conduct at least annual cybersecurity awareness training and perform mock phishing exercises—that is, e‑mails or messages sent by internal IS staff to attempt to mislead an entity’s employees into, for example, clicking a link or downloading a file that contains malware. Nonreporting entities cited the success of these efforts as one reason for their increased IS compliance and maturity, but also repeatedly mentioned a lack of qualified IS staff as one of the barriers to further improvement of their IS programs.

Several nonreporting entities also mentioned lower wages for state IS staff relative to the private sector, and some entities described the current IT staff classifications as too broad (even with the more specific functional areas like IS engineering) to attract staff with the proper qualifications and work experience. CalHR’s 2021 California State Employee Total Compensation Report shows average turnover and vacancy rates for entry‑level IT specialist staff are comparable to rates for other state staff. However, wages for entry‑level IT specialist staff are at least 20 percent lower relative to the private sector in March 2021. Total compensation, including health care and retirement benefits, appears to be more comparable between private sector companies and state government, however. Consequently, whether recruiting and retaining IS professionals is more challenging than other state positions (at least for entry‑level IT specialist staff) is somewhat unclear. However, since March 2021, when these data were collected and published, the state’s labor market has improved dramatically, making it more difficult to attract and retain qualified IS staff. Nationally, businesses and governments today are only able to fill about half of the needed technology job openings, whereas they could regularly fill most positions prior to the pandemic. At the same time, the state’s unemployment rate has decreased from 8.4 percent to 4.3 percent (as of February 2023). Moreover, inflation has increased at rates notably higher than recent state salary adjustments. Of the issues identified across the three topics in this report, we find that IS staff‑related issues might be some of the most important to address if nonreporting entities (and state entities in general) are to improve their IS compliance and maturity.

Smaller Nonreporting Entities Raised Concerns About Procurement Delays. Some of the smaller nonreporting entities we interviewed raised issues with the division of IT procurement responsibilities between CDT and DGS pursuant to Public Contract Code Sections 12100‑12113. This includes procurement of IT goods and services that are needed to remediate deficiencies and weaknesses identified through, for example, ISAs and ISPAs. These entities cited DGS’s lack of IT expertise as one barrier to more expeditious procurement of IT goods and services, as well as unnecessarily low dollar thresholds for routine purchases. A small number of these entities said they did not have enough staff to dedicate to procurements for IT goods and services, which can take months or in some cases years, and instead sought improvements to streamline IT procurement processes (particularly for smaller purchases).

Options to Improve Nonreporting Entities’ IS Compliance and Maturity

Consistent with the requirements of the SRL, we provide options for legislative consideration in this section that could improve nonreporting entities’ IS compliance to be at least comparable to reporting entities and to achieve a certain IS maturity level. We present these options to the Legislature based on our assessment of their benefit to nonreporting entities’ IS compliance, in order from highest to lowest emphasis and impact. However, as we discussed in our assessment, there are significant differences in the types of programs and services each of the nonreporting entities provide, the roles they serve on behalf of the state, and the size of their budgets and staff. Therefore, while we do generally emphasize options that could benefit all nonreporting entities, we also offer options that might benefit only some subset of nonreporting entities. As with our assessment, we organize our options across the topics of IS governance, IS compliance, and IS/IT infrastructure and staffing.

IS Governance

Consider Amending CDT’s IS Authority to Address Statutory Ambiguity of State Agency and State Entity Definitions and Use. One option for legislative consideration to improve IS governance of nonreporting entities is to amend CDT’s IS authority to address the current ambiguity in the definitions and use of state agency and state entity, and make clear whether state entities are nonreporting or reporting. Amendments to this authority would include changes to the relevant paragraphs in Government Code Section 11546.1, but also to other sections of the department’s authority such as Government Code Sections 11549‑11549.4 (OIS) and other statutes that cross‑reference CDT’s IS authority. In addition, the Legislature could consider whether to direct CDT to provide accompanying legal and policy guidance to any state entity affected by the statutory changes to confirm whether or not they are now subject to the state’s IS governance structure. We emphasize this option as one potential solution to the question of whether or not an entity is reporting or nonreporting and to any statutory interpretations that lead to inconsistencies in the implementation of the state’s cybersecurity efforts and strategy.

Recommend Monitoring Nonreporting Entities’ Compliance With and Implementation of AB 2135. We recommend monitoring nonreporting entities’ compliance with and implementation of AB 2135. Assembly Bill 2135 added the Legislature to the state’s IS governance structure. How legislative leadership (and any other Members and legislative staff) use the IS compliance documentation submitted by nonreporting entities to assess whether nonreporting entities are indeed in compliance could be critical to the longer‑term success of the law. For example, implementation of AB 2135 may require analysis of the IS compliance documentation to determine whether nonreporting entities are making progress in remediating some of their identified deficiencies and weaknesses. This analysis, depending on how it is performed, could require additional legislative resources and expertise or further clarification of the responsibilities of legislative leadership (and others) in statute.

Consider Directing CDT to Improve Ease of Use of IS‑Related Guidance, Information, and Templates. One other option for the Legislature to consider to improve IS governance is to direct CDT to make their IS‑related guidance, information, and templates both simpler and more specific to different program areas. Materials that are difficult to understand and use could be one potential barrier to more adoption of and compliance with state IS policies, procedures, and standards by nonreporting entities. For example, materials could provide clearer guidance on how to prioritize existing funding, staff, and time if new requirements are implemented without additional funding or positions. Also, CDT could consider providing guidance to state entities on how long it will take to hear back from them on their reviews of compliance documents and, if state entities have not heard back, provide the relevant contact information to address the issue. This guidance would help, for example, nonreporting entities in voluntary compliance with state requirements better understand the documentation review process. Furthermore, CDT could consider providing more varied recommendations on hardware, software, and tools with different levels of service and prices to accommodate the wide range of nonreporting entity budgets.

Consider Directing Cal‑CSIC to Increase Outreach to Nonreporting Entities Implementing Cal‑Secure. Another option for the Legislature to consider is to direct Cal‑CSIC to increase its outreach to nonreporting entities known to be implementing Cal‑Secure to actively offer guidance on the implementation. Cal‑CSIC could work with CDT and DOF to identify nonreporting entities that are requesting funding and positions to implement Cal‑Secure, and coordinate meetings and/or workshops for these entities to ask Cal‑CSIC questions about the cybersecurity initiatives and technical capabilities in the roadmap.

IS Compliance

Consider Opportunities to Condition State Funding on Compliance With Federal and State IS Policies, Procedures, and Standards. One option the Legislature could consider is to request that Cal‑CSIC, CDT, and DOF evaluate the use of provisional budget bill language for nonreporting entities’ IS‑related budget requests to condition the expenditure of funding on compliance with certain IS policies, procedures, and standards. For example, nonreporting entities are requesting funding to implement some of the cybersecurity initiatives and technical capabilities in Cal‑Secure. The administration could evaluate whether demonstrated progress towards implementation of these capabilities and initiatives as a requirement to receive some amount of additional funding might benefit statewide efforts to improve IS compliance and maturity.

The Legislature also might consider whether its monitoring of AB 2135 compliance and implementation could be used to inform its analysis of budget requests. For example, if deficiencies or weaknesses are identified in nonreporting entities’ POAMs, the Legislature might condition funding on their remediation and request more frequent updates on their POAMs. The coordination of this analysis by the Legislature across different program areas during the budget process also might warrant consideration of internal organizational changes to facilitate broader IS discussions (for example, the creation of a new budget subcommittee focused on these and other capital outlay and IT issues). We emphasize these options as important opportunities for the administration and the Legislature to obtain additional information through the budget process about nonreporting entities’ IS compliance and to guide the development of their IS programs.

Consider Directing Cal‑CSIC and CDT to Report to the Legislature on Cal‑Secure Implementation. Another option the Legislature could consider, consistent with a recent recommendation of our office on IS proposals in the Governor’s 2023‑24 budget, is to direct Cal‑CSIC (in consultation with its partners) to report annually to the Legislature on the implementation of Cal‑Secure initiatives and technical capabilities. This option could improve the Legislature’s oversight of Cal‑Secure implementation, including nonreporting entities’ efforts using funding and/or positions approved through the budget process.

Consider Requiring CDT to Develop Centralized IS Training Hub for IS Compliance Certification and Education. The Legislature also might consider requiring CDT to develop a centralized IS certification and training hub that helps educate and certify all state entity IS staff on current and forthcoming state IS policies, procedures, and standards. This centralized IS training hub could build on current IS training programs led by CDT’s Office of Professional Development and Training Center, but also focus on certification of compliance knowledge so that IS staff across state entities could easily demonstrate their understanding of federal and state IS policies, procedures, and standards. The Legislature also might consider whether specific measurable goals or outcomes for training efforts through this hub, including the number of staff from nonreporting entities that were trained, might help it monitor CDT’s progress in this area.

Consider Requiring an Evaluation of Major Cyber Insurance Products to Understand Compliance Requirements. One other option the Legislature could consider is to request that DGS’s OIRM, in consultation with CDT, provide an evaluation of the major cyber insurance products currently available to state entities to determine which products have IS compliance requirements that might improve the IS compliance and maturity of nonreporting entities. The Legislature also might consider directing DGS, in consultation with CDT and other relevant state departments such as the Department of Insurance, to develop criteria to recommend cyber insurance products to state entities that incorporate as one of the goals improved IS compliance and maturity for nonreporting entities.

IS/IT Infrastructure and Staffing

Consider Expanding Use of Shared Service Contracts for IS Services. One option the Legislature could consider, consistent with a recent recommendation on IS proposals in the Governor’s 2023‑24 budget, is to require CDT to prioritize shared service contracts for IS services as part of its IT contract consolidation efforts to reduce service costs and generate savings. (Government Code Section 11546.45(a)(4) requires CDT to implement a plan to establish centralized contracts for at least some shared services, including IS services.) The Legislature also could consider amending current reporting requirements in statute to require that CDT identify any shared services assessed, procured, and advertised to state entities in its annual report. Shared IS service contracts available to state entities at a lower cost may incentivize additional nonreporting entities to use these services, which could provide CDT with increased visibility into those entities’ IS programs.

Consider Directing Administration to Expand on Existing Recruitment, Training, and Retention Efforts to Increase Size of IS Workforce. One other option the Legislature could consider is to direct Cal‑CSIC, CalHR, CDT, GovOps, and other relevant state agencies and entities to consider expanding their existing efforts to recruit, train, and retain IS staff. The Legislature could consider whether to direct these agencies and entities to evaluate the effectiveness of existing efforts based on, for example, the number of new IS staff recruited, trained, and/or retained and report back to the Legislature with a plan on how to expand and/or improve these efforts.

The Legislature also could consider whether to expand the scope of the evaluation to include considerations of employee compensation, IT staff classifications, and other human resources‑related topics that might affect the ability of the state to recruit and retain IS staff. These employees are represented at the bargaining table by Service Employees International Union, Local 1000. The state’s labor agreement with Local 1000 is scheduled to expire June 30, 2023. Without a new agreement, these employees will not receive a compensation increase in 2023‑24. The Legislature likely will be asked to ratify a new labor agreement with Local 1000 at some point this year. While we will not know the content of a future agreement with Local 1000 until it has been submitted to the Legislature for review, it is possible that such an agreement could include provisions aimed at addressing recruitment and retention issues among these staff.

Given the consistent responses we received from nonreporting entities about the difficulties in recruiting, training, and retaining IS staff, this option could have broader benefits to other state entities that may be facing similar challenges.

Consider Monitoring State Data Center Rate Reassessment Process for IT Services. Another option the Legislature could consider is to monitor the progress of the rate reassessment process for the State Data Center that is currently underway to verify that IT services hosted by the State Data Center will be comparable both in levels of service and price to major private vendors. Similar to the previous option, we offer this option because nonreporting entities’ hosting of applications and systems on the State Data Center increases CDT’s visibility into those entities’ IS programs.

Consider Mandating Certain Network Traffic Be Directed to CDT’s SOC for Monitoring. Another option the Legislature could consider is to request that CDT, in consultation with nonreporting entities, evaluate what network traffic from nonreporting entities could be directed to its SOC. Network traffic directed from nonreporting entities to CDT’s SOC can be monitored for potential cyberattacks and threats. However, nonreporting entities might deem some network traffic to be confidential and/or sensitive. Given the need to balance more visibility into some network traffic with the need to maintain the confidentiality of other traffic, the Legislature could request that the evaluation be presented to relevant budget/policy committee staff and propose next steps for legislative consideration.

Consider Directing Administration to Evaluate Division of IT Procurement Responsibilities. Another option the Legislature could consider, particularly for smaller nonreporting entities with fewer procurement staff but consistent interaction with DGS for routine IT purchases, is to request that CDT and DGS evaluate their current division of IT procurement responsibilities and identify opportunities to streamline routine IT procurements. These opportunities could include the consolidation of IT goods and services procurement authority under CDT, increases in the dollar amount thresholds to delegate more IT goods and services purchases back to state entities, and other administrative changes that could reduce the amount of time to complete IT procurements. The Legislature also could request that CDT and DGS present the results of their evaluation to relevant budget/policy committee staff and propose next steps for legislative consideration.

APPENDIX: Major Authorities Relevant to the Report

In this appendix, we provide federal and state authorities that are relevant to this report. We acknowledge that there are other authorities from federal entities and industry organizations that state entities (including nonreporting entities) must follow. We focus on major authorities that inform our assessment and options for legislative consideration.

Federal Authorities

Federal Information Processing Standards (FIPS). FIPS are guidelines and requirements for federal computer systems developed by the National Institute for Standards and Technology (NIST). Many state and local government entities, as well as private companies, voluntarily use these standards to guide the development and implementation of their information security (IS) programs. Reporting entities follow several state IS policies, procedures, and standards based on FIPS, while nonreporting entities are required by Chapter 773 of 2022 (AB 2135, Irwin) to follow the two FIPS below:

- FIPS 199. FIPS 199 contains standards for federal agencies to use in categorizing the importance of their information and information systems based on their need for the information or systems’ availability, confidentiality, and integrity if compromised.

- FIPS 200. FIPS 200 specifies minimum security requirements for federal information and information systems, and provides a risk‑based process for selecting the security controls that are needed to meet these requirements.

NIST Special Publication (SP) 800‑53. NIST SP 800‑53 catalogues privacy and security controls for information systems to protect against a variety of cyber risks and threats. Some examples of categories for these controls include account management, information exchange, and remote access. Some examples of controls in these categories include disabling accounts based on certain criteria; verifying individual or system authorization before transferring data; and documentation of remote access implementation guidance, requirements, and restrictions prior to authorization, respectively. The latest revision to NIST SP 800‑53 is Revision 5. As with FIPS, reporting entities follow many state IS policies, procedures, and standards based on NIST SP 800‑53, while nonreporting entities are required by AB 2135 to follow Revision 5 of NIST SP 800‑53 and all successor publications.

State Authorities

Relevant Government Code Sections. Several sections of the Government Code are relevant to the definition of “state agency” and “state entity” in the California Department of Technology (CDT) Office of Information Security’s (OIS’) statutory authority. Other sections establish the California Cybersecurity Integration Center (Cal‑CSIC) and require Cal‑CSIC to develop a statewide cybersecurity strategy.

- Section 8586.5. Government Code Section 8586.5 contains the statutory authority for Cal‑CSIC. This section identifies the Governor’s Office of Emergency Services as its administrator and leader; names a number of Cal‑CSIC representatives from federal law enforcement entities, Cal‑CSIC partner entities (that is, CDT, the California Highway Patrol, and the California Military Department [CMD]), state education segments, and other state entities; and requires that Cal‑CSIC develop a statewide cybersecurity strategy, which is reflected in the state’s first five‑year IS roadmap—Cal‑Secure. While reporting entities are subject to the state’s IS governance structure and, thus, must report to Cal‑CSIC and follow Cal‑Secure, nonreporting entities largely are not subject to this structure. However, based on our research (which we discuss in more detail in the report), many nonreporting entities receive and use threat intelligence from Cal‑CSIC and use Cal‑Secure to guide their cybersecurity initiatives and technical capability investments.

- Section 11000. Government Code Section 11000 provides the definition of a state agency used across the executive branch’s agencies and departments. The statute states that “‘state agency’ includes every state office, officer, department, division, bureau, board, and commission.” Assembly Bill 2135 uses this definition to avoid any statutory interpretations that could lead to inconsistencies in the application of the bill’s amendments to Government Code Section 11549.3 (that are discussed in more detail below). This definition of state agency applies to both reporting and nonreporting entities across the Government Code except, for example, in OIS’ statutory authority where different definitions of state agency and state entity are used (as we define below).

- Section 11546.1. Part of OIS’ larger authority, Government Code Section 11546.1 requires each state agency and state entity to have a chief information officer and information security officer with specific roles and responsibilities. More importantly for this report, paragraph (e) includes two subparagraphs with definitions for state agency and state entity. These definitions are cross‑referenced in key sections of OIS’ statutory authority. For example, Government Code Section 11549.3, which we describe in more detail below, requires state entities meeting the definition in Section 11546.1(e)(2) (and not defined as state agencies in paragraph [e][1]) to comply with state IS policies, procedures, and standards. We provide more information about the definitions below:

- Definition of State Entity in OIS’ Statutory Authority. Paragraph (e)(2) defines a state entity as “an entity within the executive branch that is under the direct authority of the Governor, including, but not limited to, all departments, boards, bureaus, commissions, councils, and offices that are not defined as ‘state agency’ pursuant to paragraph (1).” Different statutory interpretations of the phrase “under the direct authority of the Governor” lead some entities to assert their independence from the authority of OIS including IS policies, procedures, and standards issued by the office under Government Code Section 11549.3. (Government Code Section 11549.3 refers to “[a]ll state entities defined in Section 11546.1.”) As we discuss in more detail in our report, we only include nonreporting entities on our list for which it is clearer based on constitutional or statutory authorities that they are not “under the direct authority of the Governor.”