LAO Contact

March 2, 2023

The 2023-24 Budget

Department of Water Resources

Summary

This brief analyzes the Governor’s budget proposals for the Department of Water Resources (DWR) related to flood management and ongoing implementation of the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act (SGMA).

Governor Proposes $175 Million in 2023‑24 for Flood Management. The Governor’s budget proposes $119 million from the General Fund in 2023‑24 to support numerous Central Valley flood projects and studies, most of which would be conducted in collaboration with the federal government. It proposes another $41 million for Delta levee projects and $16 million for flood management activities. Because the state currently is experiencing a budget problem, the Legislature will need to weigh the importance and value of proposed new activities against those to which it has already committed. In this context, we think the Legislature might want to consider approving the Governor’s proposed flood‑related spending because it would (1) help protect public safety and important water supplies, (2) help the state draw down federal funding, and (3) allow key projects that are already in progress to continue. Nearly all of the requests are one time in nature, even those for continuing projects, which would provide the Legislature with the flexibility to consider associated future spending within the context of a given year’s budget and available revenues.

Governor Proposes $14 Million in Ongoing General Fund to Support SGMA Program. The Governor’s budget proposes $14 million in ongoing funding for 11 new positions as well as to backfill expiring bond funds in order to continue supporting 29 existing positions. These positions would conduct ongoing SGMA implementation activities. The budget also includes $900,000 on a one‑time basis in 2023‑24 to develop a groundwater trading implementation plan. We find that the proposals should help the department better carry out its responsibilities and help ensure the success of local agencies in reaching groundwater basin sustainability. Given its importance in overall statewide water resource management and protecting vulnerable communities, we think the Legislature should consider approving the Governor’s proposals to provide additional resources to support successful SGMA implementation. We also recommend the Legislature continue to conduct robust oversight of ongoing SGMA activities.

Introduction

In this brief, we analyze the Governor’s budget proposals for DWR related to flood management and implementation of SGMA. The first section provides a summary of DWR’s overall proposed 2023‑24 budget. In the next section, we provide background about flood management, review the Governor’s flood‑related proposals, and provide our assessment and recommendations. In the final section, we describe the importance of groundwater to the state’s water system and the history of SGMA, detail the Governor’s proposal, and offer our assessment and recommendations.

Overview

DWR protects and manages California’s water resources. In this capacity, DWR plans for future water development and offers financial and technical assistance to water agencies for local projects. In addition, the department maintains the State Water Project (SWP), which is the nation’s largest state‑built water conveyance system. Finally, DWR performs public safety functions such as constructing, inspecting, and maintaining levees and dams.

Governor’s Budget Proposes $2.9 Billion for DWR in 2023‑24. As shown in Figure 1, the Governor’s 2023‑24 budget proposes $2.9 billion in total expenditures for DWR from all fund sources, including $900 million from the General Fund. Major budget fluctuations over recent years are due in large part to significant one‑time General Fund augmentations to respond to drought and build the state’s water resiliency. In addition, recent budgets included new energy‑related responsibilities for DWR, providing more than $2 billion from the General Fund in 2022‑23 to establish a new state energy reliability reserve. The proposed budget includes funding in 2023‑24 that was planned as part of 2021‑22 and 2022‑23 budget packages to address water resilience, energy, and nature‑based activities. The Governor proposes moderate spending reductions and delays for DWR, yielding $87 million in budget solutions in 2022‑23 and 2023‑24. (Please see our report, The 2023‑24 Budget: Crafting Climate, Resources, and Environmental Budget Solutions for more on these proposed budget solutions.) The budget includes several new General Fund spending proposals for DWR, primarily in the areas of flood management and SGMA implementation, as discussed below.

Figure 1

Department of Water Resources Budget Summary

(In Millions)

|

Fund Source |

2021‑22 |

2022‑23 |

2023‑24 |

Change From 2022‑23 to 2023‑24 |

|

|

Amount |

Percent |

||||

|

State Water Project fundsa |

$1,117b |

$1,271 |

$1,464 |

$193 |

15% |

|

Bond funds |

273 |

1,719 |

452 |

‑1,267 |

‑74 |

|

General Fund |

1,019 |

4,484 |

900 |

‑3,584 |

‑80 |

|

Special funds |

613 |

201 |

46 |

‑155 |

‑77 |

|

Federal funds |

7 |

31 |

35 |

4 |

14 |

|

Totals |

$3,028 |

$7,706 |

$2,897 |

‑$4,809 |

‑62% |

|

a Continuously appropriated outside of the annual state budget process. bThe State Water Project operates on a calendar year. Amount reflects actual expenditures for calendar year 2021. |

|||||

Flood Management

Background

California Faces Significant and Increasing Flood Risk. Estimates from a 2013 comprehensive statewide report, California’s Flood Future, suggest 7.3 million people (one‑in‑five Californians), structures valued at $575 billion, and crops valued at $7.5 billion are located in areas that have at least a 1‑in‑500 probability of flooding in any given year. According to a recent study by scientists at the University of California, Los Angeles, climate change has already doubled the likelihood of an extreme storm bringing catastrophic flooding in California, and this risk will continue to increase. Moreover, recent data reported in the 2022 Central Valley Flood Protection Plan (CVFPP) suggest that more than 1.3 million people and structures valued at more than $223 billion in the Central Valley region are at risk from flooding. These data suggest that without adequate investments in flood systems, annual deaths could more than double in the Sacramento River Basin and quadruple in the San Joaquin River Basin over a 50‑year period (2022 through 2072). The plan also estimates that failing to adequately prepare could cause annual economic damages to double in the Sacramento River Basin and more than quadruple in the San Joaquin River Basin.

State Has Special Responsibility for Flood Management in the Central Valley. California gave assurances to the federal government that it would oversee and maintain the State Plan of Flood Control (SPFC) along the main stem and certain tributaries of the Sacramento and San Joaquin Rivers, including parts of the Sacramento‑San Joaquin Delta. The SPFC includes 1,600 miles of levees, four dams, and seven flood bypasses. DWR is the state’s lead agency in flood‑related activities, while the Central Valley Flood Protection Board (an independent body housed administratively within DWR) has responsibility for overseeing the SPFC on behalf of the state. For most segments of SPFC levees, the state has developed formal agreements with local government entities (primarily local reclamation and levee districts) to handle regular operations and maintenance responsibilities. A court decision in 2003 found that the state was ultimately financially responsible for the failure of SPFC facilities, even when they had been maintained by local entities. State statute requires DWR to prepare, and the Central Valley Flood Protection Board to adopt, an update to the CVFPP every five years. The first version was adopted in 2012. The CVFPP guides flood management activities and funding for the SPFC and Central Valley region.

Many Levees Are at Risk of Failing. In addition to providing flood protection, levees located in the Delta region also are essential components of the state and federal water systems that convey water from the northern part of the state to Central and Southern California. As such, levee failures could put public health and safety as well as water supplies at risk. Given such importance, the current condition of statewide levees is concerning. Nearly 90 percent of Central Valley levee systems currently fail to meet federal performance standards, increasing the risk that they might fail. Reclamation districts’ recent five‑year plans (which assess current conditions and lay out plans for rehabilitation) have identified 500 miles on 75 Delta islands in need of improvement, with an estimated associated cost of $1.4 billion.

State Also Helps Ensure Delta Levees Remain Functional. Within the 1,100 miles of levees in the Delta, only 380 miles are part of the SPFC. The majority—730 miles—are instead privately or locally owned. Because of their importance, however, the state provides some funding to local agencies to support both SPFC and non‑SPFC Delta levees, generally through DWR’s Delta Levee System Integrity Program. This program, historically funded with Proposition 1E (2006) and Proposition 84 (2006) bond funds, includes two subprograms through which it allocates funds:

- Maintenance Subventions Program. This program provides an annual grant to local agencies, reimbursing them for up to 75 percent of their costs to maintain levees. DWR anticipates that claims will be higher this year due to recent storms.

- Special Flood Control Projects Program. This program provides grants to local agencies for projects that protect water conveyance systems (including roads and utilities) and water quality from flood hazards.

Recent State Budgets Have Committed Significant Funding for Flood Management. Over the past couple of decades, voter‑approved general obligation bond funding has been the primary funding source for flood projects—including levee repair and maintenance—and related state operations support. However, after several years of significant expenditures, the state has now expended most of the flood‑related bond funding that voters have authorized. Recent budget surpluses helped facilitate an unusually high level of General Fund support to help supplement the expiring bond funds. Specifically, recent budgets committed approximately $600 million General Fund from 2021‑22 through 2024‑25 to support numerous flood capital outlay projects, flood management activities, and dam safety projects. (An additional $140 million in bond funding was committed for these purposes over this same period.) This funding has provided support to numerous flood projects. For example, nearly all of the roughly $300 million in combined General Fund and bond funds appropriated in 2021‑22 has been committed to 14 different Central Valley flood or Delta levee projects in various stages of planning, development, or construction.

Federal Government Also Builds Capital Projects to Reduce Flood Risk and Helps Support Flood Emergency Response and Recovery. The federal government supports flood projects in California in two main ways.

- U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE). USACE authorizes and undertakes capital flood protection projects when authorized by Congress, generally in partnership with state and local agencies. USACE inspects federally constructed levees for compliance with federal standards, provides planning and assistance during flood events, provides funding to repair flood‑damaged levees, and establishes flood storage and release standards for certain reservoirs.

- Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). FEMA operates the National Flood Insurance Program, which includes developing flood hazard maps that define flood risk, establishing floodplain management standards, and offering federally backed insurance policies. It also provides coordination, assistance, and funding for federally declared flood disasters.

Federal Funds Will Help Pay For Damage From Recent Storms. State and local agencies can apply for FEMA reimbursement for eligible emergency‑related costs (such as debris removal) and repair or replacement of facilities damaged by the storms. Generally, FEMA reimburses at least 75 percent of eligible costs until funding is exhausted. The extent of the December 2022 and January 2023 storm damage is still being assessed and the timing for when public agencies will receive reimbursement is still unknown.

Governor’s Proposals

The Governor proposes funding for both flood management projects and studies as well as operational support.

Proposes $119 Million General Fund in 2023‑24 for Central Valley Flood Projects ($114 Million) and Studies ($5 Million). The Governor’s budget proposes $119 million General Fund in 2023‑24 and $35 million General Fund in 2024‑25 for various flood projects in the Central Valley. As noted in Figure 2, the funding would support five projects and two studies conducted in collaboration with USACE. It also would support two projects as part of the Urban Flood Risk Reduction (UFRR) Program. (UFRR projects are consistent with USACE feasibility studies, but can be conducted on a faster time line by the state. Additionally, USACE typically requires the state to contribute a share of the costs of undertaking federal projects in California, and UFRR expenditures can be credited toward these requirements on future USACE projects.) Finally, funding would support two additional state projects and one study.

Figure 2

Governor’s 2023‑24 Flood Project and Study Proposals

General Fund, Unless Otherwise Noted (In Millions)

|

Activity |

Proposed Funding |

Estimated Total Project Cost |

Estimated Future State Funding Needed |

Estimated Completion Date |

|

|

2023‑24 |

2024‑25 |

||||

|

Flood Management Projects |

$114 |

$35 |

$4,647 |

$577 |

|

|

Mossdale Tract Multibenefit Projecta |

$40 |

$35 |

$100 |

— |

2025 |

|

West Sacramento Projectb |

25 |

— |

1,130 |

$70 |

2030 |

|

American River Common Features Projectb |

20 |

— |

1,230 |

61 |

2026 |

|

Yolo Bypass Fix‑in‑Place Projects |

15 |

— |

40 |

45 |

2027/Ongoing |

|

Paradise Cut Bypass Expansion and Ecosystem Enhancement Project |

10 |

— |

300 |

180 |

2030 |

|

Lower Cache Creek Projectb |

1 |

— |

323 |

77 |

2036 |

|

Lower San Joaquin Projectb |

1 |

— |

1,240 |

135 |

2032 |

|

Marysville Ring Levee Projectb |

1 |

— |

193c |

10 |

2030 |

|

Smith Canal Gate Projecta |

1 |

— |

91d |

— |

2023 |

|

Flood Management Studiese |

$5 |

— |

$22 |

$8 |

|

|

Yolo Bypass‑Cache Slough Master Plan and Comprehensive Study |

$3 |

— |

$9 |

$6 |

2027 |

|

Yolo Bypass comprehensive studyb |

1 |

— |

8 |

1 |

2027 |

|

Reclamation District‑17 feasibility studyb |

1 |

— |

5 |

1 |

2027 |

|

Various Delta Levee Projects |

$41 |

— |

— |

— |

|

|

Delta levee special projects and state operations support |

$41f |

— |

— |

Unknown |

Ongoing |

|

Totals |

$159 |

$35 |

$4,669 |

$585 |

|

|

aUrban Flood Risk Reduction project. Project consistent with U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) feasibility study. Expenditures can serve as state cost share for a future USACE project. bUSACE project. Figure reflects state share of cost. cPreliminary estimate that could change based on the USACE Post Authorization Change Report, which will be completed by 2027. dConstruction is still ongoing and could result in additional cost increases. eFigure reflects costs to complete each study; subsequent projects will result in additional and more significant costs to complete. fIncludes $27 million from Proposition 1 (2014) bond funds. |

|||||

Proposes $41 Million in 2023‑24 for Delta Levees. Also shown in Figure 2, the Governor’s budget proposes $41 million for Delta levee special projects and state operations support. Specifically, it includes $27 million from Proposition 1 (2014) bond funds for local grants supporting multi‑benefit levee projects through the Special Flood Control Projects Program. In addition, it includes $11 million from the General Fund to backfill bond funding for state operations (to oversee and manage the Delta Levee System Integrity Program), as these funds will run out at the end of the current fiscal year. Finally, it includes $2 million from the General Fund for real estate acquisition and planning for previously funded projects to satisfy regulatory requirements.

Proposes $15.7 Million General Fund in 2023‑24 for State Operations Support and Several Related Activities. As shown in Figure 3, the Governor proposes $15.7 million General Fund in 2023‑24 for state operations support and other flood management activities. Some of these activities would have multiyear or ongoing costs, resulting in a four‑year funding commitment of $52 million through 2026‑27. The proposals include:

- State Operations Support for Urban Flood Projects ($10 Million One Time). This proposed funding would support DWR staff management costs for USACE/UFRR projects, which could include support on the specific projects displayed in Figure 2 as well as activities such as land acquisition, construction management, or closeout activities on previous USACE/UFRR projects. Funding would be available for expenditure until June 30, 2028.

- Preparation of Next Iteration of the CVFPP ($4.4 Million in 2023‑24; $36.9 Million Total Over Four Years). The Governor proposes providing $4.4 million in 2023‑24, $11 million in 2024‑25, $11.5 million in 2025‑26, and $10 million in 2026‑27 to prepare the next version of the CVFPP, which is due in 2027. Activities would include developing the main document, updating the status of all components of the SPFC system, conducting technical analyses of climate change impacts to the system, preparing a conservation strategy update for species recovery, developing a 30‑year investment strategy, conducting public engagement, and ensuring compliance with the California Environmental Quality Act and tribal policies.

- State Flood Maintenance and Operations Support ($655,000 Ongoing). The Governor’s budget proposes funding and authority for two environmental scientist positions to support ongoing flood maintenance and operations. These positions would be located at the two DWR maintenance yards to handle environmental permitting and tribal consultations. Funding also would support associated baseline costs, including consulting and professional services.

- Three Flood Board Engineer Positions ($623,000 Ongoing). The Governor’s budget proposes funding and authority for three new engineer positions at the Central Valley Flood Protection Board. These positions would be dedicated to addressing noncompliant levee encroachments (which are structures or features, such as landscaping, piping, or fencing, that cut into a levee). The purpose of this work is to help Central Valley levees retain or attain compliance with federal USACE standards.

Figure 3

Governor’s 2023‑24 Flood Management Operations and Related Proposals

General Fund (In Millions)

|

Proposal |

2023‑24 |

Totals: |

Term |

|

State operations support for urban flood projects |

$10.0 |

$10.0 |

One time |

|

2027 Central Valley Flood Protection Plan |

4.4 |

36.9 |

Through 2026‑27 |

|

State flood maintenance and operations support |

0.7 |

2.6 |

Ongoing |

|

Central Valley Flood Protection Board engineer positions |

0.6 |

2.5 |

Ongoing |

|

Totals |

$15.7 |

$52.0 |

Assessment

Higher Bar for Approving New Proposals Given General Fund Condition. The Governor’s new flood‑related proposals would commit the state to significant discretionary General Fund expenditures in 2023‑24. Importantly, the state currently is experiencing a budget problem, where General Fund revenues already are insufficient to fund existing commitments. In this context, every dollar of new spending in the budget year comes at the expense of a previously identified priority and requires finding a commensurate level of solution somewhere within the budget. The Governor “makes room” for proposed new spending on flood projects by making reductions to funds committed for other programs, including many in the climate and natural resources areas. We think the Legislature will want to apply a higher bar to its review of new spending proposals such as these than it might in a year in which the General Fund had more capacity to support new commitments, as it will need to weigh the importance and value of the proposed new activities against the activities to which it has already committed. Essentially, it will want to consider whether it wants to make reductions—either those proposed by the Governor or equivalent alternatives—to free up resources for these flood projects.

Flood and Levee Proposals Might Meet That Higher Bar. In our view, several reasons make the case for the Governor’s flood‑related proposals potentially meeting this high threshold for justifying new spending. As we discuss in more detail below, these proposals would (1) respond to various critical flood protection and risk management needs, (2) help the state draw down federal funding, and (3) allow key projects that are already in progress to continue. Additionally, although many of the proposals do support continuing projects, nearly all of the current requests are one time in nature. This structure provides the state with the flexibility to consider associated future spending within the context of a given year’s budget and available revenues.

Central Valley Flood and Delta Levee Projects Are Important Part of State’s Flood Management System. The Governor’s flood proposals focus on the Central Valley and the Delta. This makes sense because the state has particular responsibility for maintaining the SPFC and given that the reliability of Delta levees is essential for the continued operation of statewide water conveyance systems. Taking steps now to mitigate existing flood risk—as well as the increasing hazards expected to result from climate change—could prevent both significant and costly damage as well as threats to public safety in future years.

Share of Flood Project Funding Would Help State Draw Down Federal Support. The Governor’s proposed spending on flood management would not only help mitigate flood risk, but also would help the state generate significant federal support. Of the proposed $119 million for flood projects and studies, $50 million reflects the state’s required cost share for USACE projects. In addition, the two projects that are part of the UFRR program could generate credits toward state spending requirements for future USACE projects. Nearly all of these projects are already in progress and the proposed funding would allow the next phase to be completed. Therefore, the proposed $10 million to support state staff associated with oversight and management of these and other USACE/UFRR projects also merits consideration.

Funding for Delta Levees Would Prioritize the Most Critical Areas. We also find merit in the Governor’s proposed spending on Delta levee programs. The proposal would support multi‑benefit projects to improve levees and restore habitat in the Delta, providing flood protection benefits to the SWP. In addition, the General Fund portion of the request would backfill expiring bond funding for state operations and satisfy regulatory requirements for previously funded projects. Finally, although the proposed project funding ($27.4 million Proposition 1 bond funds) would only partially address what reclamation districts have identified as a $1.4 billion need for Delta levees, DWR indicates it would prioritize the funds for the most urgent projects. Specifically, it would first allocate funding to those projects on Delta islands or tracts deemed as “very high priority” in risk assessments developed by the Delta Stewardship Council. (The council used new levee geometry, hydraulic data, and projected impacts on vulnerable populations to develop these assessments.)

CVFPP Costs Appear Reasonable, in Line With Previous Iterations of the Plan. Average annual costs to prepare the CVFPP have been about $8.5 million since development of the first version, which was released in 2012. The current request, which would average $9.2 million annually for four years, is thus in line with historical costs. These costs may seem high for the development of a plan—especially one that is an update of several previous iterations. Generally this is because these updates involve detailed, comprehensive, and technical analyses, including modeling the potential impacts of climate change and related adaptation activities. Although the time and staffing resources to prepare the next plan seem reasonable, the Legislature might wish to ask if any of these activities or processes—such as modeling climate impacts—could be more streamlined or automated given that this plan has to be updated every five years.

Recommendation

Consider Approving Funding for Flood Management Projects, State Operations, and Related Activities. Approving General Fund for these proposals requires identifying commensurate reductions from other existing spending commitments, which the Governor does through his package of budget solutions. However, this funding would support important activities that help protect public health and safety by lowering risks to flood prone areas and protecting key water conveyance infrastructure. To help avoid the potential losses to life and property that can result from serious flood events, the Legislature might want to consider approving the funding despite the associated budget trade‑offs. The proposed funding would help draw down federal support for many of the projects and, because nearly all of it is one time in nature, the state could consider out‑year spending within the context of future fiscal conditions.

Sustainable Groundwater Management Act Implementation

Background

Groundwater Depletion Is Escalating. Groundwater is a key component of the state’s water supply. Water users rely less on groundwater in wet years—when surface water is more abundant—and more in dry years. In some smaller and more vulnerable communities that lack access to surface water, groundwater provides up to 100 percent of drinking water supplies. Overall, California uses more groundwater than is restored through natural or artificial means. This imbalance is leading to depletion (known as “overdraft”), failed wells, water quality problems, permanent collapse of underground basins, and land subsidence. The current drought has heightened the urgent need for sustainable groundwater management. And while recent storms may have helped recharge some shallow groundwater basins, years of overdraft in deeper basins mean it could take months or years to recharge groundwater in some areas.

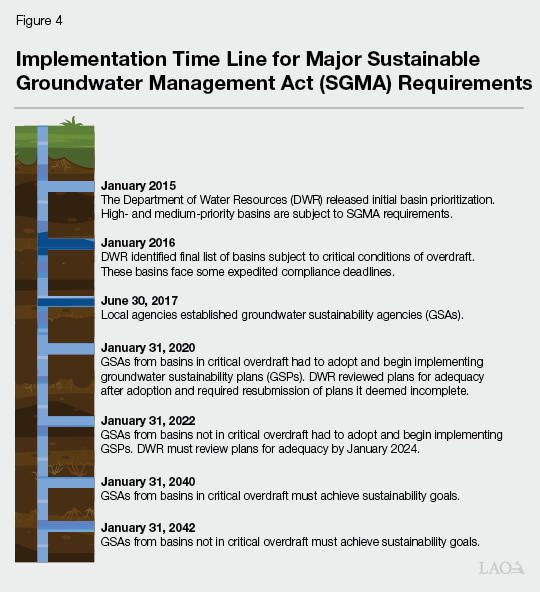

State Passed Major Legislation to Regulate Groundwater in 2014. In 2014, the Legislature passed and the Governor signed three new laws—Chapters 346 (SB 1168, Pavley), 347 (AB 1739, Dickinson), and 348 (SB 1319, Pavley)—collectively known as SGMA. With the goal of achieving long‑term groundwater resource sustainability beginning in 2040, the legislation represents the first comprehensive statewide requirement to monitor and operate groundwater basins to avoid overdraft. The act’s requirements apply to 94 of the state’s 515 groundwater basins that DWR has found to be “high and medium priority” based on various factors, including overlying population and irrigated acreage, number of wells, and reliance on groundwater. (The remaining 421 basins ranked as being lower in priority—generally smaller and more remote—are encouraged but not required to adhere to SGMA.) While comprising less than one‑fifth of the groundwater basins in California, the 94 high‑ and medium‑priority basins account for 98 percent of California’s annual groundwater pumping. Figure 4 displays the time line for meeting SGMA’s key requirements.

SGMA Required Local Agencies to Submit Groundwater Sustainability Plans (GSPs). SGMA assigns primary responsibility for ongoing groundwater management to local entities, through the required formation of groundwater sustainability agencies (GSAs). SGMA requires GSAs to develop and implement long‑term GSPs. These plans define the specific guidelines and practices that govern the use of individual groundwater basins, including potentially limiting extractions from these basins. Among the 94 high‑ and medium‑priority basins, DWR identified 21 as being “critically overdrafted,”which it defines as a condition where a “continuation of present water management practices would probably result in significant adverse overdraft‑related environmental, social, or economic impacts.” The GSAs managing groundwater in those basins were required to submit their GSPs to DWR for review by January 2020, while GSPs for the remaining basins were due by January 2022. SGMA allows DWR two years to review GSPs. Among the critically overdrafted basins, DWR deemed GSPs for 12 basins to be incomplete and required that they be resubmitted in July 2022. DWR continues to review new and resubmitted GSPs.

DWR Undertaking Numerous Key Activities. SGMA tasked DWR with several key responsibilities in the initial phases of the act’s implementation. As GSAs developed and have begun to implement their GSPs, DWR’s role has continued to grow. Figure 5 displays some of DWR’s key SGMA activities.

Figure 5

DWR’s Key Sustainable Groundwater

Management Act (SGMA) Implementation Activities

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

DWR = Department of Water Resources. |

The State Water Resources Control Board (SWRCB) also has certain responsibilities in implementing SGMA, such as to intervene when local entities do not follow the law’s requirements. If any basins ultimately fail to comply with SGMA, SWRCB is charged with taking over their management.

State Has Provided Significant Funding to Implement SGMA. As shown in Figure 6, the state has provided more than $800 million since 2014‑15 for SGMA implementation activities. This includes:

- State Operations. DWR has received $314 million ($84 million from Proposition 68 bond funds and $229 million from the General Fund) to support state management of the SGMA program.

- Local Planning Grants. The state has provided $93 million in Proposition 1 bond funds for planning grants, which supported local agencies as they formed GSAs and developed their GSPs.

- Local Implementation Grants. The state has provided $430 million ($134 million from Proposition 68 bond funds and $296 million from the General Fund) for local implementation grants. Examples of grant‑funded activities include developing ways to inject surface water into aquifers, expanding conveyance infrastructure to increase recharge, installing monitoring wells, and developing or upgrading infrastructure to increase the use of recycled water.

Figure 6

Sustainable Groundwater Management Act Resource History

(In Millions)

|

2014‑15 Through 2021‑22 |

2022‑23 |

Totals |

|||||

|

Proposition 1 |

Proposition 68 |

General Fund |

Proposition 68 |

General Fund |

|||

|

State operations |

— |

$68 |

$203 |

$16 |

$27 |

$314 |

|

|

Planning grants |

$93 |

— |

— |

— |

— |

93 |

|

|

Implementation grants |

— |

134 |

180 |

— |

116 |

430 |

|

|

Totals |

$93 |

$202 |

$383 |

$16 |

$143 |

$837 |

|

About 125 DWR Staff Currently Support SGMA Program. Currently, the SGMA program has authority for 69 positions. In addition, staff from other DWR programs are sometimes assigned to the SGMA program and typically are funded on a limited‑term basis. Currently, about 56 positions are on loan from other DWR programs. Of the 125 staff currently supporting SGMA, 31 are funded with Proposition 68 bond funds, while 94 are funded by the General Fund.

Governor’s Proposals

Proposes $14 Million in Ongoing General Fund to Support 40 Positions, 11 of Which Are New. The Governor’s budget proposes $14 million General Fund on an ongoing basis and authority for 11 new positions to support SGMA implementation activities. In addition to supporting the new positions, this funding would backfill expiring Proposition 68 funds in order to continue funding 29 existing positions. Overall, the proposal would sustain roughly the same current number of positions in the SGMA program, as most of the 11 new positions would backfill some of the current staff who were temporarily assigned to SMGA work but will be transitioning back to their other DWR responsibilities beginning in 2024‑25. The 11 new positions would be conducting:

- Enhanced Data Collection. DWR plans to increase the frequency at which it collects data from existing and new monitoring wells, particularly in high‑priority areas, such as areas in which vulnerable communities rely on domestic wells, areas identified for recharge projects, and areas where land is actively subsiding and dry well mitigation measures are taking place.

- Enhanced Basin Characterization. DWR plans to conduct higher resolution aerial and ground‑based geophysical surveys of groundwater basins. These surveys will benefit recharge projects by providing information about ideal recharge pathways and subsurface layers and land subsidence. They will also inform placement of additional groundwater monitoring stations.

- Enhanced Reporting. DWR plans to continue sharing information online, to aid in data‑informed decision making. In addition, it will more frequently update dry‑well susceptibility analyses and provide this information to all levels of government for drought, flood, and recharge planning and response.

Proposes $900,000 in One‑Time General Fund Support to Develop Groundwater Trading Implementation Plan. The budget proposes $900,000 General Fund on a one‑time basis to develop an implementation plan for groundwater trading that considers vulnerable users. The funding would support two DWR positions and engage consulting services to help complete the plan. The plan would be developed based on recommendations in the California Water Commission’s white paper, A State Role in Supporting Groundwater Trading with Safeguards for Vulnerable Users: Findings and Next Steps. This one‑time planning effort would include interagency coordination among DWR, Department of Fish and Wildlife, Department of Food and Agriculture, and SWRCB. It would consider impacts on disadvantaged communities, small and medium farmers, and the environment.

Assessment

Successful Implementation of SGMA Is Vital to State’s Water Supply, Community Drinking Water, and Agricultural Sector. The state relies heavily on groundwater, both for drinking water—particularly for small, vulnerable communities dependent on wells—and agricultural irrigation. As it grapples with periods of prolonged drought and a resulting lack of consistently adequate amounts of surface water, the importance of groundwater continues to grow. Successful implementation of SGMA’s requirements will help ensure that the goals envisioned by the Legislature are achieved and remain a priority. The past decade has included a number of key SGMA implementation milestones, including definition and prioritization of groundwater basins; formation of GSAs; data collection; and development, submission, and review of GSPs. The state has entered the next period of SGMA implementation—undertaking the activities articulated in the GSPs that will eventually lead to basin sustainability. DWR plays an important role in ensuring these activities are successful, and the proposed increase in SGMA program funding and position authority could help the department better carry out its responsibilities.

Having DWR Collect and Disseminate Key Data Makes Sense. DWR has taken on more responsibility for collecting and reporting groundwater data statewide than was originally envisioned. This seems appropriate, in that it leverages DWR’s economies of scale relative to having each local agency collect and report data. Moreover, having DWR collect key information, such as data about groundwater levels and land subsidence, not only ensures that the data and measurements are consistent across groundwater basins statewide, but that data are collected on a regular and frequent basis.

Expanding Role of DWR Would Benefit From Increased General Fund Support. Although SGMA implementation continues to move from planning to execution, DWR still has workload associated with reviewing GSPs and providing technical assistance to GSAs on their plans. DWR also will have ongoing workload associated with reviewing GSAs’ annual reports and regular five‑year GSP updates. Because Proposition 68 funds have mostly all been expended, DWR would not be able to continue these existing activities at the same level without more support. In addition, DWR is taking on an expanded role that should help facilitate better decision‑making and inform recharge, dry well mitigation, and flood projects.

Ongoing Legislative Oversight of SGMA Implementation Is Important. Given the state’s reliance on groundwater and the importance of SGMA to ensuring the sustainability of groundwater basins, ongoing oversight by the Legislature can help ensure implementation remains on pace and legislative priorities are being met. Legislative oversight also can help ensure that GSPs adequately account for equity concerns and that inequities are not exacerbated. For example, legislative oversight can shine a light on whether enough is being done in vulnerable communities that rely on domestic wells for their drinking water and where reports of dry wells have been increasing. The success of SGMA ultimately is not about whether deadlines are being met—although deadlines can help ensure progress—but whether groundwater use, banking, and recharge allow the state to actually reach sustainability.

Recommendations

Consider Approving Ongoing and One‑Time Funding and Positions. As discussed earlier, in the context of the state’s budget problem, we recommend the Legislature employ a higher threshold when considering new General Fund spending proposals, given that they necessitate making reductions to existing spending commitments. We find that the proposed funding and position authority for SGMA implementation activities could meet this higher bar, despite the associated trade‑offs. They would allow DWR to continue implementing SGMA activities that the Legislature has previously indicated are among its high priorities. Moreover, ensuring sustainable groundwater management is key not only to future water supplies and the state’s agricultural sector, but also to protecting drinking water for many vulnerable communities. The proposed funding would support DWR activities that are important to the success of local agencies in achieving statewide groundwater sustainability, and would allow the state to take advantage of economies of scale by supporting centralized data collection. We therefore recommend the Legislature consider approving the Governor’s proposals.

Continue to Monitor Successes and Challenges of SGMA Implementation. Given its importance in overall statewide water resource management and protecting vulnerable communities, we recommend the Legislature continue to conduct robust oversight of ongoing SGMA implementation. The Legislature could do this through a number of ways, including requesting updates at annual budget subcommittee hearings, conducting oversight hearings, or requesting additional reporting when warranted. For example, the Legislature could consider holding oversight hearings or requesting additional reporting at particular milestones, such as the completion of the groundwater trading implementation plan, DWR’s final determinations on all GSPs, or at the five‑year mark when GSAs must submit GSP updates.