LAO Contact

February 28, 2023

The 2023-24 Budget

California’s Film Tax Credit

- California’s Motion Picture Industry

- Film Tax Credit

- Economic Effects of the Credit

- Governor’s Proposal to Extend the Credit

- Conclusion

- References

Summary

California’s Film Tax Credit Created to Counteract Other States’ Efforts to Attract Hollywood. During the 2000s, California policy makers became concerned that the state may be losing motion picture production to other states. In response, the Legislature in 2009 created a film tax credit to encourage motion picture productions to locate here. The Legislature since has extended and expanded the credit multiple times. It currently is scheduled to expire in 2025.

Governor Proposes Five Year Extension of Film Tax Credit. The Governor’s budget proposes a five year extension of the film tax credit. The Governor also proposes to make the credit refundable—allowing production companies to claim credits in excess of the amount of taxes they owe.

Film Tax Credit Makes California’s Motion Picture Industry Bigger, but Effect on Overall Economy Is Unclear. Our review of research on state film tax credits suggests that state’s with film tax credits have larger motion picture industries. Whether or not this results in growth of the state’s overall economy, however, is unclear. This is because revenues forgone to the film tax credit could have been spent on other activities, which would have grown other parts of the economy. Existing evidence does not allow us to be confident that film tax credits lead to more economic activity than alternative uses of funds.

Decision on Extension Should Depend on How the Legislature Prioritizes the Importance of Hollywood. We do not recommend considering the film tax credit as a reliable mechanism to grow the state’s overall economy. Instead, how the Legislature assesses a potential extension should depend on how much it prioritizes the importance of maintaining Hollywood’s centrality in the motion picture industry.

If Extending the Credit, Refundability Worth Considering but With Modifications. If the Legislature elects to extend the credit, refundability is worth considering but with modifications to achieve some benefits of refundability (such as improved taxpayer equity) while limiting the downsides (such as increased costs and administrative complexity). These modifications include: specifying a schedule for the credit to be claimed over a period of years, reducing the annual allocation cap, and limiting other flexibilities in production companies’ use of the credit.

California’s Motion Picture Industry

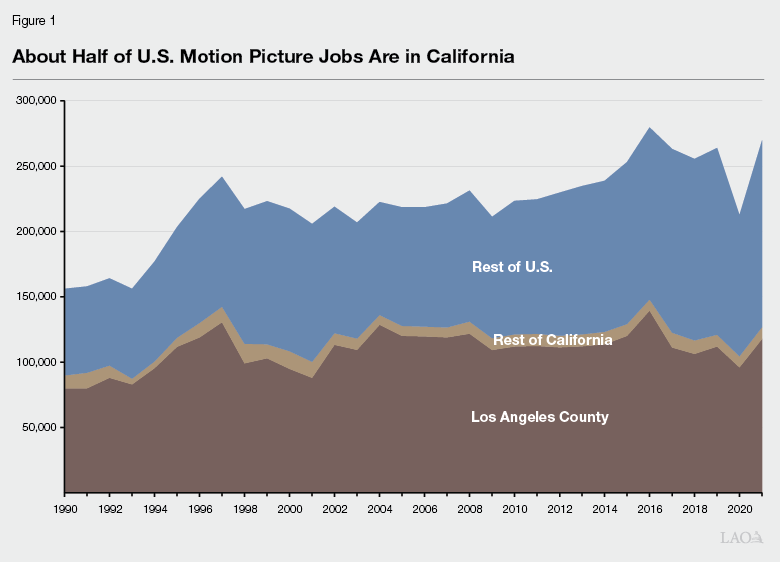

Los Angeles Remains the Center of U.S. Motion Picture Industry. The U.S. motion picture production industry is heavily concentrated in Los Angeles. A little under half of the industry’s jobs are located in and around Los Angeles. As shown in Figure 1, motion picture production employment in California has been steady at around 125,000 for the past two decades. Over the same time period, employment in the industry outside of California has increased gradually. As a result, California’s share of national employment in the industry has fallen from 52 percent a decade ago to 47 percent today. Nonetheless, California remains the preeminent state in motion picture production, with more than twice the jobs as the next largest state (New York).

Motion Picture Industry Pays Above Average Wages. California workers in the motion picture industry earned an average of $2,600 per week in 2021, nearly 60 percent higher than the average of all workers in the state. These earnings put motion picture workers on par with workers in sectors like banking, engineering, and advertising.

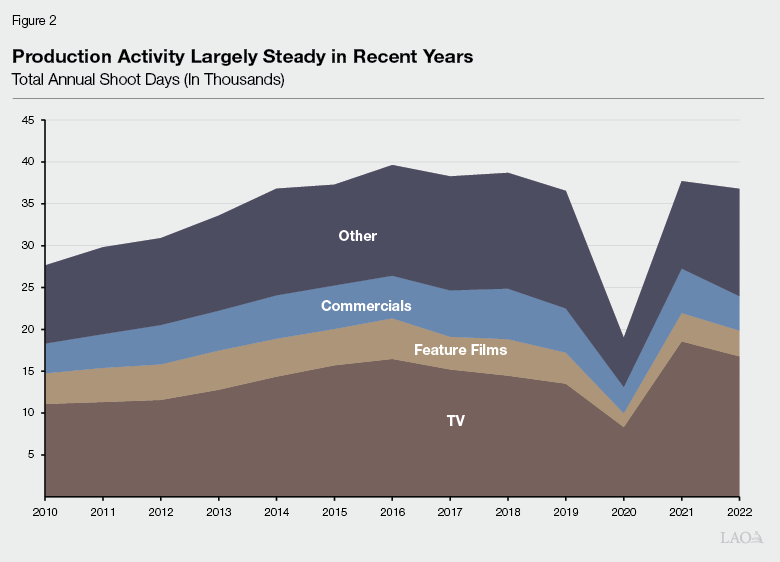

Motion Picture Production Activity Steady in Recent Years. Figure 2 shows one measure of motion picture production activity in California (total days of principal photography [shoot days] across all productions) for 2010 through 2022. As this figure shows, aside for a dramatic drop early in the pandemic, production activity has maintained a consistent level over much of the past decade.

Television Shows Are the Largest Category of Production. TV shows have made up between 40 percent and 50 percent of production in California in recent years. TV production in 2021 and 2022 is about 20 percent higher than the five years leading up to the pandemic. This increase is entirely attributable to reality TV shows. In contrast, feature film production has declined in recent years.

Film Tax Credit

Creation and Expansion of California’s Film Tax Credit

California Film Tax Credit Created in 2009. During the 2000s, California policy makers became concerned that the state may be losing motion picture production jobs to other states. In response, the Legislature in 2009 created a tax credit to reduce production companies’ tax liabilities by up to 25 percent of certain production expenses. Credits can be used to reduce corporation, personal income, or sales tax liabilities. The credit is nonrefundable (meaning a taxpayer cannot claim credits in excess of their tax liability) but can be carried forward and claimed over several years. Total credits were capped at $100 million annually statewide. The California Film Commission (CFC) allocates and issues the credits to eligible production companies.

Tax Credit Programs Expanded in 2015. The state’s film tax credit was expanded in 2015 to $330 million per year. The new program—referred to as Program 2.0—also made significant changes to how credits are allocated and provided an additional 5 percent tax credit for certain kinds of production spending, such as visual effects. The state film tax credit was set to expire in June 2020, but the 2018 budget package extended it for an additional five years (through 2025) and made relatively minor changes to the program—now referred to as Program 3.0. The 2021 budget package temporary increased the annual allocation of film tax credits under Program 3.0 by $90 million for fiscal years 2021‑22 and 2022‑23. Figure 3 compares the three iterations of the film tax credit.

Figure 3

Comparison of California Film Tax Credit Programs

|

Program |

First Film Tax Credit |

“Program 2.0” |

2018 Extension |

|

Years in Effect |

2009‑2017 |

2015‑2020 |

2020‑2025 |

|

Amount per Year |

$100 million |

$330 milliona |

$330 million |

|

Credit Allocation |

Lottery |

Jobs ratio score |

Modified jobs ratio score |

|

Allocation Categories |

10 percent of total credits reserved for independent films |

Credits allocated as follows: |

Credits allocated as follows: |

|

|

||

|

Credit Percentage |

Base: 20% of qualified spending. |

Base: 20% of qualified spending, plus additional: |

Base: 20% of qualified spending, plus additional: |

|

|

|

|

|

Independent films and relocating television: 25% |

|

||

|

Other Requirements |

Complete “career readiness” requirement. Provide a statement that credit was a significant factor in choice of location. |

In addition to the added requirements of Program 2.0, production companies must have a written policy against sexual harassment and provide a summary of programs to increase workplace diversity. |

|

|

aOnly $230 million was available in the first year of Program 2.0 because it was concurrent with the first credit. |

|||

Additional Funding for Productions Filmed at New or Renovated Soundstages. The 2021 budget package also included an allocation of $150 million in film tax credits for productions that are filmed at new or renovated soundstages. The credits are available for productions in 2022 through 2032. The CFC identifies and certifies qualified soundstage construction projects. Productions receiving credits under this program are required to set ethnic, racial, and gender diversity goals and to develop a plan to achieve those diversity goals. Those productions are eligible to receive an additional 4 percent tax credit if they meet or make a good faith effort to meet their diversity goals. This new program otherwise is similar to the broader film credit program.

Program Statistics

$646 Million in Credits Issued for First Film Credit. The state had expected to issue a total of $800 million in credits under the first version of the program. Of that amount, the CFC issued a total $646 million in tax credits. This amount is less than expected because some productions (1) were never made, (2) did not complete production on time, or (3) spent less on qualified expenses than anticipated.

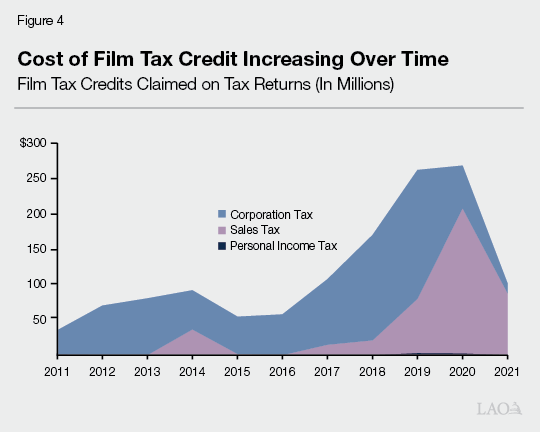

Most Credits Issued Under First Film Credit Have Been Claimed. Most credits from the first film tax credit program were used to reduce corporation tax payments. Figure 4 shows film tax credit claims from 2011 to 2021. To date, taxpayers have used $571 million of credits from the first program to reduce their corporation tax payments. Much of the remaining credits have been claimed against sale taxes.

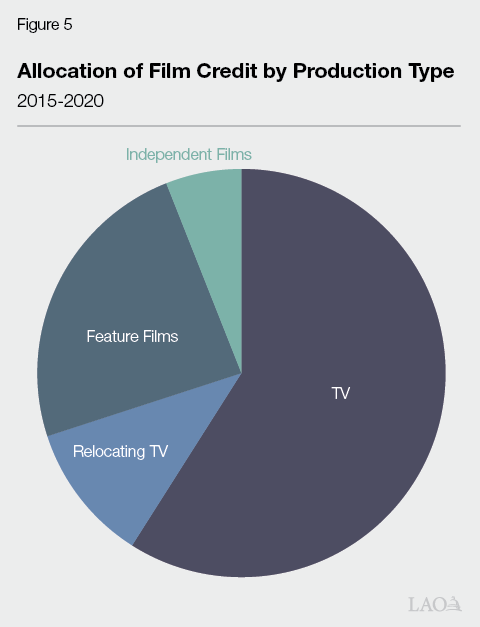

$1.55 Billion Allocated Under Program 2.0. The CFC allocated $1.55 billion in tax credits to 238 productions between 2015 and 2020. The average credit amount per production under Program 2.0 ($6.5 million) was notably higher than under the earlier program (about $2 million). Figure 5 shows the distribution of credits across types of production. TV received 70 percent of the credits, with 11 percent going to relocating TV shows. This contrasts with 55 percent under the first film tax credit program.

Credit Claims Shifting to Sales Tax. Whereas most of the credits from the first program were claimed against corporation taxes, claims against the sales tax have increased in importance during the time of Program 2.0. From 2017 to 2021, around $500 million in credits ($275 million from Program 2.0) have been claimed against corporation taxes. Over the same time period, around $300 million in credits were claimed against the sales tax. This shift may be due in part to actions taken in the 2020 budget package to limit taxpayers’ use of business tax credits in 2020 and 2021.

Limited Number of Taxpayers Benefit From the Credit. In tax years 2017 through 2019, 10 to 15 taxpayers annually used film tax credits to reduce their taxes.

Program 2.0 Demographics. Demographic data voluntarily submitted to the CFC by film tax credit recipients suggests that some demographic groups are underrepresented among the workforce on tax credit productions. In particular, the voluntarily reported statistics show men outnumbered women three to one on productions. Similarly, Latino and Asian American crew members make up a considerably smaller share of production workforce than their share of California’s overall population.

Competition From Other States

Most Other States Offer Film Tax Incentives. During the 2000s, state film tax incentives (primarily tax credits) expanded rapidly across the country. At the peak in 2010, 45 states had a film tax incentive. In the wake of the Great Recession, a number of states eliminated their programs. Nonetheless, 37 states currently have active film tax incentives.

Recent Expansions in Other States. According to the National Conference of State Legislatures, at least ten states created or expanded film tax incentives in 2021. Another five states did so in 2022.

Several State’s Credit Programs Are More Generous Than California. Several other states have film tax credit programs that are more generous (and expensive) than California’s. Whereas California caps film tax credit allocations at $330 million per year, some states—such as Georgia, Massachusetts, and Connecticut—do not have an annual cap on the amount of tax credits available to production companies. Similarly, while California’s film tax credit is nonrefundable, more than ten states provide refundable credits. This means a taxpayer can claim more credits than their tax liability, allowing them to receive a refund.

Economic Effects of the Credit

In this section we review existing research on the economic effects of film tax credits. Dozens of studies over the last two decades have examined the economic effects of film tax credits in California and other states. These studies have used a variety of methods and reached varying conclusions. While all of these studies have limitations, some approaches are more reliable than others. In particular, our review focuses on studies that (1) account for the fact that some productions would have selected the same location even without a tax credit, (2) consider both direct economic effects (such as wage paid to production workers) and indirect economic effects (such as wages paid to workers at businesses supporting motion picture production), and (3) avoid the use of statistical methods known to be unreliable.

States With Film Tax Credits Likely Have More Motion Picture Production. While some studies reach mixed or inconclusive findings, the balance of the evidence suggests that motion picture production increases in states with film tax credits. Our 2016 analysis of data on productions that applied for California’s film credit suggested that two‑thirds of recipients would not have filmed here without the credit. A similar study of California’s film credit found being offered a credit doubled the chances a production would be made in California (Workman [2021]). Another study examining location decisions of productions around the country found that state film credits meaningfully shifted the distribution of productions towards states with credits (Owens and Rennhoff [2020]). Multiple studies systematically comparing states with film credits to states without generally showed increased production activity in states with film credits (Bradbury [2019], Rickman and Wang [2020], and Button [2021]). Overall, this evidence suggests that film tax credits probably influence the location decisions of 25 percent to 75 percent of credit recipients.

California’s Motion Picture Industry Probably a Few Percentage Points Larger. The CFC reports around $2 billion in annual production spending associated with projects that received Program 2.0 credits. Adjusting for the share of productions that would have happened anyway suggests the Program 2.0 credits were associated with around $1 billion in additional production activity per year. This represents about 2 percent of California’s overall motion picture industry.

Unclear Effect on the Broader Economy. Although the film tax credit likely increased economic activity in California’s motion picture industry, whether it resulted in growth of the state’s broader economy is unclear. Forgone state tax revenue from the film tax credit could have been spent on other programs or services. This alternative spending similarly would have increased activity in some part of the state’s economy. Measuring the economic effect of any state spending (including film tax credits) is challenging. Nonetheless, the best available evidence suggests that we cannot be confident that the economic benefit of film tax credits exceeds alternative uses of state funds.

Comparing Film Credits to Some Alternatives. One of the more optimistic estimates from the studies mentioned above suggests that each dollar of film tax credit results in an increase of $2 to $4 in earnings for workers in that state. At the same time, research on other types of public spending—such as K‑12 education and workforce development—suggests comparable or better earnings benefits for workers (Heinrich et al. [2013], Jackson [2015], and Hollenbeck [2017]). This suggests the potential for at least similar economic benefits if state resources used for film tax credits were instead allocated to other purposes.

Does Not Pay for Itself. A recent study from the Los Angeles County Economic Development Corporation found that each $1 of Program 2.0 credit results in $1.07 in new state and local government revenue. This finding, however, is significantly overstated due to the study’s use of implausible assumptions. Most importantly, the study assumes that no productions receiving tax credits would have filmed here in the absence of the credit. This is out of line with economic research discussed above which suggests tax credits influence location decisions of only a portion of recipients. Two studies that better reflects this research finding suggest that each $1 of film credit results in $0.20 to $0.50 of state revenues (Owens and Rennhoff [2020]), Rickman and Wang [2020]).

Governor’s Proposal to Extend the Credit

Extend the Credit for Five Years. The Governor proposed to extend the film tax credit an additional five years, from July 2025 to June 2030. The annual allocation would remain $330 million.

Make Credit Refundable, but With Restrictions. The proposal also would make the film tax credit refundable. Production companies could receive a refund for a portion of their credits that exceed their tax liability. Specifically, a taxpayer may receive a refund equal to the lesser of: (1) 18 percent of the credit or (2) 90 percent of the portion of the credit exceeding their tax liability. A taxpayer electing to receive such a refund would forfeit a portion of their credit equal to the lesser of: (1) 2 percent of the credit or (2) 10 percent of the portion of the credit exceeding their tax liability.

Diversity Requirements. The proposal also includes diversity requirements that are similar to those that apply to productions filmed at new or renovated soundstages, with two key differences. First, whereas the soundstage requirement provides an additional 4 percent credit to productions that meet or make a good faith effort to meet their diversity goals, the Governor’s proposal would subtract 4 percent from baseline credit for productions failing to do so. Second, the requirements do not apply to independent films with qualified expenditures less than $10 million.

Assessment

Legislature’s Assessment Should Depend on How It Prioritizes Hollywood’s Importance. Based on our research review discussed above, we do not recommend considering the film tax credit as a reliable tool to grow the state’s overall economy. Extending the film tax credit likely would lead to California’s motion picture industry being a couple percentage points larger than otherwise. However, it is not clear that extending the film credit would expand California’s overall economy. Instead, the film tax credit’s most likely impact appears to be increasing the motion picture industry’s share of California’s economy. Given this, how the Legislature assesses the Governor’s proposal should primarily depend on how much it prioritizes the importance of maintaining Hollywood’s centrality in the motion picture industry.

Refundable Credits Have Some Advantages… Making the film tax credit refundable could have some advantages:

- Improved Taxpayer Equity. With the current nonrefundable credit, a taxpayer’s ability to claim the credit is tied to the amount of their state tax liability. This means their ability to claim credits can vary based on factors unrelated to motion picture production. For example, some taxpayers engage in other operations that result in sales tax liability, which allows them to claim additional credits. Similarly, some taxpayers may receive tax credits for other activities the state aims to encourage (such as research and development) which reduce their tax liability and limit their ability to claim film tax credits. Making the film tax credit refundable delinks credit claiming from tax liability and thereby lessens differential treatment of taxpayers.

- More Appealing to Production Companies. Refundable film tax credits would be more appealing to production companies. This is because it would allow companies to receive tax benefits sooner in many cases. The program is already fully subscribed, however, so increasing its appeal probably would not result in more productions taking advantage of the credit. However, refundability might change the composition of productions applying for and receiving credits. Some limited evidence suggests that refundable credits may be particularly appealing to larger production companies and productions with larger crews (Owens and Rennhoff [2020]). If so, this might further the goal of expanding the size of California’s motion picture industry.

…But Also Disadvantages. However, the potential benefits of a refundable film tax credit should be weighed against several disadvantages:

- Accelerated State Costs. A primary advantage for the state of the film tax credit being nonrefundable is that it spreads state costs for the credit over several years. For instance, looking at the first film tax credit program, we see that most of the allocated credits were eventually claimed but only over the course of many years. If the credit were made refundable, state costs instead would be incurred more quickly.

- Increased Costs. In addition, overall state costs for the credit would increase if it were refundable. With a nonrefundable credit, some taxpayers never have enough tax liability, even over multiple years, to fully claim theirs credits. Because of this, the administration estimates that making the credit refundable would increase state costs for the proposed extension by a total of $200 million across multiple years.

- Increased Administrative Complexity. California currently does not have any refundable business tax credits. For this reason, the Franchise Tax Board’s (FTB’s) procedures are designed only to allow taxpayers to receive refunds for payments they have made. Making the film tax credit refundable would necessitate administrative changes at FTB that would result in additional costs and complexity. Consistent with this, the Governor’s budget includes a request from FTB for $4.5 million in 2023‑24 and seven positions to prepare itself to implement refundable business tax credits in general. FTB anticipates additional costs specific to administration of a refundable film tax credit.

- Could Stoke “Race to the Bottom.” Ideally, the state would not feel a need to have a film tax credit to maintain its current motion picture industry. However, widespread competition from film tax credits in other states has caused the state to look to tax credits as a way to protect a prized industry. In this environment, a potential disadvantage of California adopting a refundable tax credit is that it could prompt competing states to further expand the generosity of their programs. This heightened interstate competition would be counterproductive to the film tax credit’s goal of protecting Hollywood.

Recommendations

If Extending the Credit, Refundability Worth Considering but With Modifications. Ultimately, whether or not the Legislature approves the proposed extension of the film tax credit depends on how it weighs the importance of Hollywood against its various other priorities. If the Legislature elects to extend the credit, however, refundability is worth considering but with modifications. Specifically, we suggest several modifications to achieve some benefits of refundability while limiting the downsides. Taking these steps to contain costs could especially make sense in an environment where the Governor’s budget anticipates shortfalls over the next several years.

Consider Making Fully Refundable. The Governor’s proposed rules to limit the amount of film tax credits refunded each year are unnecessarily complex and would increase administrative burden for applicants and FTB. We think there are more straightforward methods to limit state costs while making the film tax credit fully refundable, which we discuss below. Further, the proposed restrictions on refundability would lessen the extent to which the policy change would improve taxpayer equity. The proposed restrictions could be binding on certain taxpayers for reasons unrelated to their motion picture production activities—such as whether or not they have significant sales tax liability. As such, we suggest the Legislature consider making the credit fully refundable, but only in combination with the additional suggestions below.

Specify a Schedule of Credit Claiming. As mentioned above, an advantage of the nonrefundable film tax credit is that it spreads state costs over several years. The state could maintain this benefit while making the credit refundable by specifying that the credit be claimed in equal increments over a number of years. A similar approach is used for other tax credit programs, such as the state’s low‑income housing tax credit. Spreading credit claiming over five years would achieve the same benefits as the Governor’s proposal for partial refundability, but with less complexity.

Reduce Annual Credit Allocation for Cost Neutrality. The administration estimates that making the film tax credit refundable will increase total state costs by about 12 percent. An option to reduce this impact could be to reduce the annual allocation of credits commensurately, from $330 million to $290 million.

Eliminate Some Flexibilities in Claiming the Credit. Some flexibilities in claiming the film tax credit, such as allowing credits to be applied to sales tax liability or reassigned within a corporate filing group, primarily exist to lessen the constraint non‑refundability creates for taxpayers. As such, these flexibilities become unnecessary if the credit is made refundable. Further, these flexibilities add to the administrative complexity of the credit. For this reason, we suggest eliminating these flexibilities if the credit is made refundable.

Conclusion

Despite years of competition from other states, Hollywood remains the center of the U.S. motion picture industry. California’s film tax credit has been one of several contributing factors to the stability of the motion picture industry in the state. As such, it is somewhat understandable that the Legislature would consider extending the film tax credit through the end of the decade. In doing so, however, it is important for the Legislature to weigh the importance of maintaining Hollywood’s primacy against its many competing priorities, especially in an environment where the Governor’s budget anticipates shortfalls over the next several years.

Note: This report was prepared in fulfilment of the reporting requirement of Revenue and Taxation Code 38.9(a).

References

Bradbury, John Charles. “Can movie production incentives grow the economy? Evidence from Georgia and North Carolina.” Evidence from Georgia and North Carolina (August 4, 2019) (2019).

Bradbury, John Charles. “Do movie production incentives generate economic development?” Contemporary Economic Policy 38.2 (2020): 327‑342.

Button, Patrick. “Do tax incentives affect business location and economic development? Evidence from state film incentives.” Regional science and urban economics 77 (2019): 315‑339.

Button, Patrick. “Can tax incentives create a local film industry? Evidence from Louisiana and New Mexico.” Journal of Urban Affairs 43.5 (2021): 658‑684.

Heinrich, Carolyn J., et al. “Do public employment and training programs work?” IZA Journal of Labor economics 2 (2013): 1‑23.

Hollenbeck, Kevin, and Wei‑Jang Huang. “Net impact and benefit‑cost estimates of the workforce development system in Washington State.” (2017).

Jackson, C. Kirabo, Rucker C. Johnson, and Claudia Persico. “The Effects of School Spending on Educational and Economic Outcomes: Evidence from School Finance Reforms.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 131.1 (2016): 157‑218.

O’Brien, Nina F., and Christianne J. Lane. “Effects of economic incentives in the American film industry: An ecological approach.” Regional Studies 52.6 (2018): 865‑875.

Owens, Mark F., and Adam D. Rennhoff. “Motion picture production incentives and filming location decisions: a discrete choice approach.” Journal of Economic Geography 20.3 (2020): 679‑709.

Rickman, Dan, and Hongbo Wang. “Lights, Camera, What Action? The Nascent Literature on the Economics of US State Film Incentives.” (2020).

Swenson, Charles W. “Preliminary evidence on film production and state incentives.” Economic Development Quarterly 31.1 (2017): 65‑80.

Thom, Michael. “Lights, camera, but no action? Tax and economic development lessons from state motion picture incentive programs.” The American Review of Public Administration 48.1 (2018): 33‑51.

Thom, Michael. “Time to yell “cut?” An evaluation of the California Film and Production Tax Credit for the motion picture industry.” California Journal of Politics and Policy 10.1 (2018).

Thom, Michael. “Do state corporate tax incentives create jobs? Quasi‑experimental evidence from the entertainment industry.” State and Local Government Review 51.2 (2019): 92‑103.

Workman, Alec. “Ready for a close‑up: The effect of tax incentives on film production in California.” Economic Development Quarterly 35.2 (2021): 125‑140.