LAO Contact

March 29, 2022

The 2022‑23 Budget

Department of Developmental Services

Summary. In this post, we provide an overview of the proposed 2022‑23 Department of Developmental Services (DDS) budget and assess the three main new discretionary proposals. We then raise oversight issues for legislative consideration.

Background

Eligibility for DDS Services

Lanterman Act Lays Foundation for “Statutory Entitlement.” California’s Lanterman Developmental Disabilities Services Act (Lanterman Act) originally was passed in 1969 and substantially revised in 1977. It amounts to a statutory entitlement to services and supports for individuals ages 3 and older who have a qualifying developmental disability. Qualifying disabilities include autism, epilepsy, cerebral palsy, intellectual disabilities, and other conditions closely related to intellectual disabilities (such as a traumatic brain injury) that require similar treatment. The disability must be substantial, expected to continue indefinitely, and start before the age of 18. There are no income‑related eligibility criteria. DDS currently serves about 325,000 Lanterman‑eligible individuals and another 1,600 children ages 3 and 4 who are provisionally eligible (described later in this post).

California Early Intervention Services Act Ensures Services for Eligible Infants and Toddlers. DDS also provides services via its Early Start program to any infant or toddler under the age of 3 with a qualifying developmental delay or who are at risk of developmental disability. There are no income‑related eligibility criteria. DDS currently serves about 48,000 infants and toddlers in the Early Start program.

Regional Center (RC) Service Coordination

RCs Coordinate and Pay for Individuals’ Services. DDS contracts with 21 nonprofit RCs, which coordinate and pay for the direct services provided to “consumers” (the term used in statute). Services are delivered by a large network of private for‑profit and nonprofit providers.

Statute Stipulates Caseload Size for RCs’ Service Coordinators. Statute sets the following average service coordinator‑to‑consumer ratios for RCs:

- 1:62 for consumers enrolled in Medicaid waiver programs.

- 1:62 for consumers who transitioned from a developmental center into a community setting at least 12 months ago.

- 1:45 for consumers who transitioned from a developmental center into a community setting fewer than 12 months ago.

- 1:62 for infants and toddlers under age 3.

- 1:25 for consumers who have complex needs.

- 1:66 for all others.

In addition, the 2021‑22 budget approved funding for caseload ratios of 1:40 for consumers who have a low level or no services purchased by RCs (on the basis that these consumers may be underserved). However, this caseload ratio was not stipulated in statute.

Processes for Children Under Age 5

Toddlers in Early Start Transition to Schools at Age 3. While the Early Start program receives the large majority of its support from the General Fund, it also receives federal funding from the Medicaid program and from Part C of the Individuals With Disabilities Education Act (IDEA). At age 3, the toddlers who continue to need services to address developmental delays or disabilities transition from Part C to Part B of IDEA at age 3. The California Department of Education (CDE) manages Part B and schools provide the services, which include evaluation and screening; special education; speech, physical, and occupational therapies; and communications assessments and adaptive communication equipment. California must adhere to federally established Part B and Part C time lines and other rules as a condition of receiving IDEA funding.

Provisional Lanterman Act Eligibility for Children Ages 3 and 4. At age 3, toddlers also may be assessed by RCs for Lanterman Act eligibility. If eligible, they could then receive DDS services, which at that age could include respite, durable medical equipment, home health care, or day care, among other services. For some children, however, determining at age 3 whether they have a substantial, indefinite, and qualifying disability is difficult, and yet they may benefit from receiving additional DDS services. Addressing this issue, the 2021‑22 budget began allowing RCs to grant provisional Lanterman Act eligibility for children ages 3 and 4 whose disability status is ambiguous and to reassess them at age 5. Currently, DDS is serving about 1,600 children with provisional eligibility.

Consumer Employment Issues

California Is an “Employment First” State. State and federal policy have shifted in recent years toward promoting competitive integrated employment (CIE) for individuals with developmental disabilities. (In this context, “competitive” means market rate wages.) Chapter 667 of 2013 (AB 1041, Chesbro) created California’s employment first policy, which makes CIE the highest priority for working age consumers, regardless of the severity of their disability. In 2014, Congress passed the Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act, which promotes CIE and increased training and supports (particularly for those age 24 and younger), and generally prohibits employers from paying less than minimum wage to employees with developmental disabilities.

Chapter 339 of 2021 (SB 639, Durazo) Phases Out Subminimum Wage. Currently, about 3,800 consumers who are working earn less than minimum wage. About 3,600 of these consumers are served in work activity programs (WAPs), where they earn a wage based on their specific level of productivity. Paying subminimum wage to an individual with a disability requires a federal certificate issued under the Fair Labor Standards Act. Chapter 339 phases out the use of these certificates in California by January 1, 2025 (or when the required multiyear phaseout plan led by State Council on Developmental Disabilities is released, whichever is later).

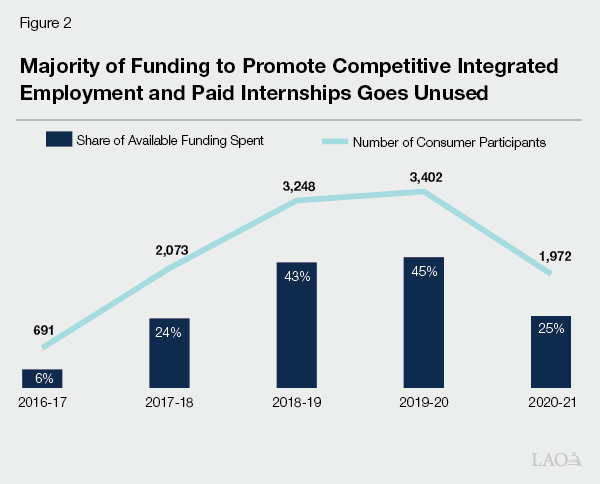

State Funds CIE Incentives and Paid Internship Programs to Encourage Employment. Chapter 3 of 2016 (AB X2 1, Thurmond) provided DDS an annual $20 million General Fund augmentation to support (1) incentive payments for supported employment providers and (2) consumers’ paid internships in CIE environments.

Recent Budget Included $10 Million General Fund for Employment‑Related Grants. The 2021‑22 budget provided $10 million one‑time General Fund to DDS to support grants to organizations developing innovative strategies to increase CIE among consumers.

Major Federal Rule Change Affecting Home‑ and Community‑Based Services (HCBS) Taking Effect in 2023

Nearly All Types of RC‑Coordinated HCBS Services Are Eligible for Federal Funding. HCBS services are considered services and supports that allow an individual to live in community‑based settings, rather than in institutional settings. They include residential services, independent and supported living services, day programs, transportation, supported employment, and respite. Nearly all types of RC‑coordinated services are considered HCBS and are eligible to receive federal HCBS funding (when provided to a consumer enrolled in Medi‑Cal, the state’s Medicaid program).

Service Provider Compliance With New Federal Rule Required to Draw Down Federal Medicaid Funding. The federal Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services approved a new rule in 2014 that requires states to ensure that any Medicaid‑funded HCBS services promote person‑centered planning, individual choice, and increased independence and are provided in the most integrated setting possible. The rule, originally set to take effect in 2019, has been pushed back twice and now is set to take effect on March 17, 2023. California’s service providers must be in compliance with the final HCBS rule for the state to draw down Medicaid funding for HCBS services.

State Funds Grants to Assist Providers in Reaching Compliance. Chapter 3 provided DDS $11 million General Fund annually beginning in 2016‑17 to support grants for service providers to modify their programs and services to make them compliant with the final HCBS rule.

Proposed 2022‑23 DDS Budget

Overview

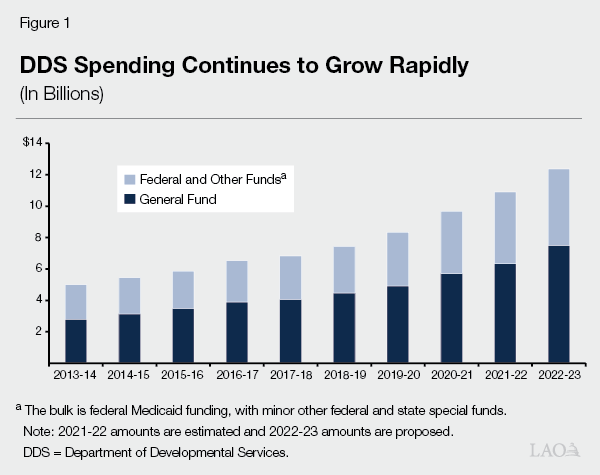

Proposed Budget Reflects Significant Growth. The Governor’s budget proposal includes $12.4 billion total funds in 2022‑23, up $1.5 billion (13.6 percent) over the revised 2021‑22 level ($10.9 billion). Of the proposed 2022‑23 total, $7.5 billion is from the General Fund, up $1.2 billion (18.4 percent) over the revised 2021‑22 level ($6.3 billion General Fund). This significant year‑over‑year growth in DDS spending follows the spending growth trend over the past ten years, as shown in Figure 1. Primary drivers of the year‑over‑year General Fund growth include: growth in caseload, increased utilization of services, additional costs for ramping up 2021‑22 initiatives, and the cost of a temporary 6.2 percentage point increase in federal Medicaid funding ending. (The latter assumes the temporary increase, which is tied to the federal public health emergency declaration, ends June 30. If the federal declaration is extended further, General Fund costs will be lower than assumed in the budget.)

New Proposals Are Relatively Small in Number and Total Cost. New discretionary proposals—including increasing the number of service coordinators for young children, conducting communications assessments for consumers who have hearing impairments, and developing a pilot project for individuals transitioning from WAPs—total $73 million General Fund in 2022‑23, declining to $61 million in 2023‑24, and to $59 million in 2024‑25 and ongoing.

Caseload Estimates Appear High. Caseload estimates for 2021‑22 and 2022‑23 appear slightly high and we would expect a downward revision in May. Such a downward revision could reduce General Fund spending by more than $200 million across 2021‑22 and 2022‑23.

Proposal for Early Childhood and Transition to Schools

The proposal includes $65.5 million total funds ($45.1 million General Fund) in 2022‑23 and $82.5 million total funds ($55.8 million General Fund) in 2023‑24 and ongoing and includes three components:

- Caseload Ratios. The proposal includes $51.1 million total funds ($31.9 million General Fund) in 2022‑23 and $68.1 million total funds ($42.6 million General Fund) in 2023‑24 and ongoing to reduce the average service coordinator‑to‑consumer caseload ratio at each RC to 1:40 for children ages 5 and under. As noted earlier, the current statutory ratio for children under 3 is 1:62. (Caseloads for children under age 3 averaged 59 per service coordinator across RCs as of March 2021.) Currently, there are no statutory caseload rules based specifically on ages 3 through 5. The current proposal notes potential positive outcomes that could result from smaller service coordinator caseloads, such as service coordinators having more encounters with the family and attending the school individual education plan (IEP) meetings with the family.

- RC and DDS Specialists. The proposal includes $4.4 million total funds ($3.2 million General Fund) in 2022‑23 and ongoing for one IDEA specialist per RC and six childhood specialists at DDS, several of whom would focus primarily on early childhood (including the transition from IDEA Part C to Part B). RC specialists would train and support service coordinators working with children exiting Part C to move to Part B and would provide technical assistance to the RC and the school providing infant and toddler services.

- Preschool Inclusion and Accessibility. The proposal includes $10 million General Fund ongoing to improve the inclusion of children with developmental disabilities at preschools. For context, the CDE budget includes funding for related proposals requiring state preschools’ enrollment to include at least 10 percent of students having a disability.

The proposal complements one‑time projects funded with American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) funds ($23.9 million) provided July 1, 2021 and available through September 2023. The one‑time projects supported with ARPA funds focus on training for earlier intervention service providers to provide more culturally and linguistically sensitive services, supporting families when they first receive their child’s disability diagnosis, outreach and education to underserved populations (to increase Early Start take‑up rates), and providing technology tools related to screening and assessments.

Assessment. There are known problems with DDS meeting federal IDEA time line requirements in its Early Start program and in transitioning children from Part C to Part B. A statutorily required workgroup, including CDE and DDS, recently examined ways to improve Part C to Part B transitions. It recommended maximum Early Start caseloads of 45 per RC service coordinator (but noted additional research may be needed). The Governor’s budget in 2020 also proposed caseload ratios of 1:45 for ages 3, 4, and 5, but the proposal was withdrawn once the pandemic hit. While the administration’s justification for selecting a 1:40 ratio is fairly reasonable, DDS also may achieve the desired results with a 1:45 ratio—as recommended by the workgroup—at a lower cost (we estimate about $14 million General Fund less in the first year and nearly $19 million General Fund less annually thereafter).

We also note that the administration’s proposed trailer bill language does not include a provision requiring RCs to implement the 1:40 ratio for children ages 5 and under. Instead, the language indicates that DDS would handle caseload ratios for this age group administratively, through its contracts with RCs. This approach deviates from previous practice and we suggest the Legislature codify in statute the final agreed‑upon ratio. Having the ratio in statute provides a benchmark the Legislature can use in its oversight of DDS, particularly given that the administration believes these smaller caseloads will improve the quality of RC service and outcomes for young children.

The Legislature also might consider whether the trailer bill should specify additional activities that would be required, rather than just encouraged, of RC service coordinators. While the language would require quarterly meetings between the service coordinator and family, it does not specify other activities, such as attending IEP meetings with families (if families consent). The concern being that some of these activities might not always be done if they are not required.

The proposal to add IDEA specialists at each RC (there currently are no such dedicated specialists required) makes sense, particularly to support the transition to schools that takes place at age 3. However, given that RCs vary significantly—in the number of young children served (and thus service coordinators who would need support), in demographic traits and number of languages spoken, and in the number of schools in the area—we question whether having the same number of IDEA specialists (one) at each RC is the best approach. For example, might the larger and more complex RCs warrant more than one specialist?

The DDS proposal to make preschools more inclusive lacks sufficient detail to assess it; consequently, we withhold a recommendation. For example, the proposal as written does not identify whether the preschools include only state preschools or all preschools of any type. (DDS subsequently indicated the proposal would include non‑state preschools, particularly those in underserved areas, although the preschool inclusion proposal and implementation details are not part of the proposed Part C to Part B trailer bill language.) The DDS proposal does not define what “disability” means in terms of inclusion. (In contrast, CDE’s proposal would require the child to have an individualized family service plan or IEP and be receiving associated services.) The DDS proposal does not explain how the $10 million estimate was developed, how it would use the funding to create inclusive preschools, or exactly how it would coordinate efforts with CDE. The Legislature could continue to press the administration for additional detail about this proposal, such as:

- How will DDS identify and reach out to providers that need support to ensure their programs are inclusive?

- What would constitute inclusion for a preschool to receive support from DDS?

- Why is the administration proposing $10 million for this purpose? How many and what share of preschools is this amount meant to help? What exactly will this $10 million be used for?

Proposal to Develop Alternatives to Subminimum Wage Employment of Consumers

Proposal. The proposal includes $8.3 million total funds ($5 million General Fund) one time, available over three years, and one DDS position to pilot an alternative service model to WAPs and to implement Chapter 339. The DDS proposal would focus on alternatives for individuals currently served in WAPs or just graduating from high school.

Assessment. In concept, the proposal has merit for several main reasons. First, Chapter 339 and the HCBS final rule effectively eliminate most WAPs, so alternatives will be needed. Second, for some individuals served in WAPs, quickly finding a new job that constitutes CIE may be difficult. In such a case, the individual currently served in a WAP is at risk of losing employment altogether as WAPs are phased out. Consequently, phasing out WAPs and providing employment alternatives deserve careful consideration. Third, this proposal is consistent with state and federal policy direction. In 2019, we recommended DDS take a more deliberative approach to planning the phase out of outmoded service models like WAPs.

Despite its merits, the proposal raises a couple of issues. First, the pilot would not include individuals making subminimum wage who are served in other programs, such as day programs or group supported employment programs, meaning that alternatives to those programs also will need to be developed. Second, the timing of the pilot raises some concerns. Although the HCBS final rule takes effect in March 2023 and subminimum wage should be fully phased out by January 2025, this three‑year pilot would not begin until December 2022 and end until December 2025. This raises the following questions:

- Will all WAPs be closed by March 2023 when the HCBS final rule takes effect? If so, what will happen to the individuals currently served in these programs if they have not found alternatives?

- What options will be available to individuals who are not participating in the pilot given the timing of both the HCBS final rule and phase out of subminimum wage?

- If some WAPs remain operational following March 2023, but are found to be out of compliance with the HCBS final rule, does DDS expect the General Fund to backfill lost federal funds?

Proposal for Resources to Support Individuals Who Are Deaf

Proposal. The proposal includes $14.3 million total funds ($8.4 million General Fund) one time to conduct communications assessments to inform individual program planning for the estimated 14,300 consumers who are deaf or hard of hearing. Communications assessments in this context ascertain the ways an individual with a developmental disability and who is deaf or hard of hearing best expresses themselves and receives information. It also identifies the supports and adaptive technology they will need to communicate (including identifying the competencies support staff will need) as well as assesses an individual’s communication potential (including recommendations for what they need to increase their success in communicating). This proposal comes on the heels of a 2021‑22 ongoing augmentation of $2.4 million total funds ($1.6 million General Fund) to support one deaf service specialist at each RC and one deaf specialist at DDS. It also is related to litigation by Disability Rights California on behalf of deaf consumers who allege discrimination by RCs for not providing sufficient accommodation and supports to engage in community life, resulting in isolation and lack of meaningful communication.

Assessment. This proposal appears to be a good step toward providing better service to consumers who are deaf or hard of hearing.

DDS Oversight Issues

In recent years, the DDS system has undergone some significant changes that warrant the Legislature’s oversight of their implementation and related outcomes. Below, we discuss two broad sets of changes to frame this discussion: (1) major new spending initiatives in recent years and (2) governance and process changes intended to better identify and address system challenges. Given these recent actions, we pose some questions for legislative consideration. As DDS will continue to implement significant new programs and policies over the next several years, considering some of these questions now could help in the process of identifying implementation challenges and possible solutions to ensure these resources and programmatic changes are having the intended effect.

Recent Major Spending Initiatives

Major New Spending Initiatives in Recent Years Are Meant to Improve Consumer Outcomes and Sustain Service Provider Network. The 2021‑22 budget—and the spending plan associated with federal HCBS funding provided by ARPA—included at least 21 fully new efforts in the DDS system. Among others, these include rate reform and the associated quality incentive program, which together are meant to sustain the service provider network while improving consumer outcomes. They also include programs meant to improve the quality and equitable delivery of services, such as direct service provider training and certification, an RC performance incentive program, and RC implicit bias training. The General Fund cost of these 21 initiatives will continue to ramp up significantly, as follows:

- $250 million in 2021‑22.

- $524 million in 2022‑23.

- $896 million in 2023‑24.

- $923 million in 2024‑25.

- $1.45 billion in 2025‑26 and ongoing.

The 2021‑22 budget also augmented several other initiatives that began in recent years, including the Self‑Determination Program (SDP), forensic diversion, and RC crisis training.

In addition, resources have been targeted in recent years to address several specific issues, including in the area of CIE and HCBS compliance (as noted earlier) and in the areas described below.

Racial/Ethnic Disparities in the Per Person Amount Spent on Services. $11 million General Fund annually since 2016‑17 for grants to RCs and community‑based organizations ($66 million cumulatively to date) to close disparities in spending.

Implementation of SDP. $6.8 million General Fund in each of 2021‑22, 2022‑23, and 2023‑24, and declining to $2.2 million General Fund annually thereafter for the ongoing implementation of the SDP. In addition, $1 million General Fund annually was provided beginning in 2021‑22 for a new Office of the SDP Ombudsperson. Chapter 683 of 2013 (SB 468, Emmerson) established the SDP, yet the program did not begin until 2018 when DDS received federal approval allowing the state to draw down federal funds for the program.

Recent Governance and Process‑Related Changes

Governance/Process‑Related Changes Intended to Increase Transparency/Accountability and Improve Decision‑Making. The 2019‑20 budget included funding for a significant reorganization of DDS headquarters to help the department align resources with new or expanded responsibilities and modernize the department to reflect changing expectations of individuals with developmental disabilities. Over the past several years, DDS has increased the amount of publicly available data and information about its programs and the individuals served to provide greater transparency into its activities. It also has improved the online display and interactive features of some of this information, including for example, data about the purchase of services, results from the National Core Indicators survey, and select information about RCs.

Budget‑related legislation from 2019‑20 included new reporting requirements for both RCs and DDS and also shifted the focus of quarterly briefings for legislative staff to the broader DDS system. (Previously, these quarterly briefings were focused on the closure of developmental centers.) Both of these changes were meant to increase accountability and enhance legislative oversight.

DDS also recently expanded and reformulated its Developmental Services Taskforce and created or reorganized numerous workgroups. The membership within each of these groups is meant to reflect the geographic and demographic diversity of the DDS system and include consumers, family members, RCs, service providers, and other stakeholders. DDS relies on these groups to understand issues, develop new ideas, and inform key decisions.

Ongoing Issues and Challenges Persist

Despite some of the recent efforts and targeted funding to address particular issues, our review of available data finds that there are ongoing issues and challenges that persist. We discuss a number of these below.

Racial/Ethnic and Other Disparities in Spending Persist. Despite DDS’s numerous recent initiatives and grants to address inequities, disparities in spending across racial/ethnic groups persist. The 2021‑22 budget approved funding for DDS to evaluate the various small projects supported with the targeted funding, which could potentially identify scalable promising practices to improve equity in the system. Nevertheless, the most recently available statewide spending data from 2020‑21 shows that the average per person amount spent on services for white consumers ($28,000), for example, is more than twice that spent on services for Latino consumers ($12,100). Some of this disparity can be explained by more Latino than white consumers living in the family home rather than in a group home or on their own (which is more costly), but it does not explain all of the disparity. For example, in 2020‑21, all but one RC spent more (on average, 23 percent more) on white consumers living with their parents than on Latinos consumers living with their parents. Every RC spent more (on average, 61 percent more) on independent or supported living services for white consumers living on their own relative to Latino consumers in similar situations. There has not been a formal research study to understand the major causes and nuanced underlying reasons as to why RCs spend more on some consumers than on others.

DDS Consumer Employment Rates Remain Low. According to Employment Development Department data presented on DDS’s RC Oversight Dashboard, the employment rate for people with developmental disabilities in California has remained below 17 percent since 2016‑17, and it worsened during the COVID‑19 pandemic, dropping from 16 percent in 2019 to 13.5 percent through the first half of 2020. Figure 2 shows that of the funding provided for CIE incentives and paid internships each year, a majority goes unused.

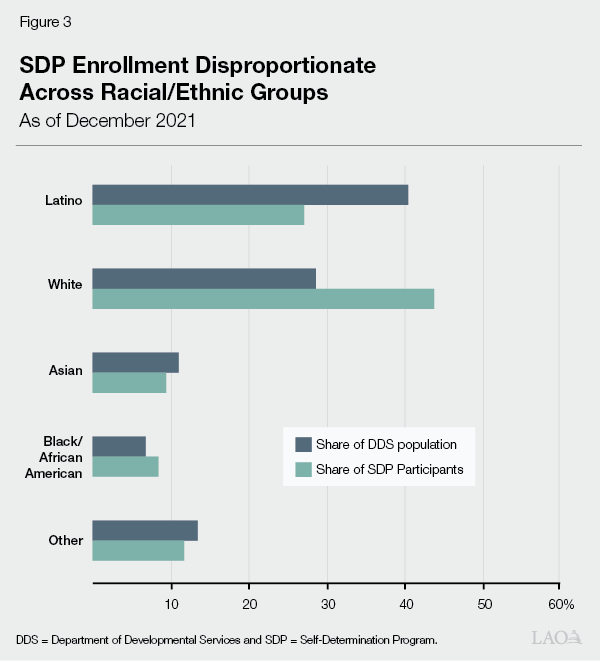

SDP Rollout Continues to Lag. Chapter 683 created a phase‑in period for SDP, limiting enrollment during the first three years to 2,500 individuals. During these first three years (July 2018 through June 2021), DDS and RCs enrolled just 625 participants, with two RCs enrolling fewer than ten people. Per Chapter 683, the program was made available to all interested consumers as of July 2021. As of December 2021, 1,102 people were enrolled and this group did not reflect the racial/ethnic composition of the DDS consumer population. Figure 3 shows that the plurality of participants is white (44 percent), despite whites making up 29 percent of all DDS consumers. By comparison, Latinos comprise only 27 percent of SDP participants, but 40 percent of all DDS consumers.

Many Providers Still Are Not in Compliance With HCBS Final Rule Set to Take Effect in March 2023. As of October 2021, 43 percent of the 9,050 providers of which DDS required a self‑assessment or on‑site assessment reported they do not meet or only partially meet all federal requirements, as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4

Many Service Providers Not Yet in Full Compliance With HCBS Final Rule

As of October 1, 2021

|

Service Type |

Completed Assessment? |

Meet All Federal Requirements? |

|||

|

Identified for Assessment |

Completed Assessment (%) |

Yes (%) |

No or Meet Some (%) |

||

|

Residential |

6,401 |

77% |

62% |

38% |

|

|

Day Service |

2,405 |

82 |

49 |

51 |

|

|

Supported Employment |

168 |

89 |

35 |

65 |

|

|

Work Activity Program |

76 |

79 |

25 |

75 |

|

|

Overall |

9,050 |

78% |

57% |

43% |

|

|

HCBS = home‑ and community‑based services. |

|||||

Recommended Reporting

Recommend Legislature Ask DDS to Report on the Following Topics. We cite some of the examples above as a cautionary note when overseeing the new programs approved in 2021‑22 and significant levels of funding approved to flow to DDS over the next several years. We recommend the Legislature continue to ask DDS for ongoing updates about the implementation of these programs and recommend it ask DDS some of the following questions as a way to understand any implementation challenges and identify any changes that may be helpful to ensure the success of these programs.

- What Is DDS’s Plan for Making Iterative Improvements in New Programs? Questions could include: As DDS implements rate reform and the quality incentive program, are any statutory or rate model changes needed now to improve a rate‑setting system that presumably will be in place for some time? How will DDS identify and address needed refinements in rate‑setting, the quality incentive program, and the RC performance incentive program going forward?

- What Is DDS’s Process for Identifying and Addressing Problems in Service Delivery? Questions could include: What methods does DDS use to understand why certain problems (such as racial/ethnic disparities, low employment, or low SDP participation) persist? Has it identified the particular causes of these problems? Has DDS sought the advice of other states that have been more successful in certain areas (if that is the case)? How does DDS use the currently available data and information to understand issues and propose solutions? How is workgroup input used in developing policy and procedures? How is data used in tandem with workgroup input to refine proposals and programs?

- Do DDS, RCs, and Service Providers Have Capacity Challenges? Do DDS, RCs, and service providers have capacity problems that limit their ability to achieve desired outcomes and to implement the many new programs and projects created in the past several years to address system challenges? How much of an impact do capacity limitations have on the success of a project or program?

- What Is DDS’s Plan for Overhauling Two Key Information Technology Systems? The spending plan associated with HCBS ARPA funds included planning dollars to overhaul two important data systems—the consumer records management system and the uniform fiscal system (which supports invoicing and payment of service providers). The Governor’s budget proposal for 2022‑23, however, provides no detail about this effort. These systems will be vital to implementing the two performance‑based programs approved in 2021‑22 and to understanding system trends, including consumer outcomes, consumer service needs, gaps in service provider availability, performance of RCs and service providers, equity in the purchase of services, and spending trends. We have been recommending better data systems since 2017. What can DDS tell the Legislature about its planning process, time line, and goals for these systems and about their desired functionality? Who does DDS intend to include in planning conversations? Will all users—from DDS program staff to RC staff and service coordinators to families and consumers and service providers—be allowed to provide input? What currently available software has or will DDS consider, such as software used in other states or by other human services programs? How will DDS implement performance‑based programs without these systems in place?