LAO Contact

April 14, 2021

Improving Parolee Substance Use Disorder Treatment Through Medi-Cal

- Introduction

- Background

- Medi‑Cal SUDT Has Advantages Over CDCR’s SUDT for Parolees

- Recommend Increasing Utilization of Medi‑Cal for Parolee SUDT

- Conclusion

Executive Summary

Several Benefits to Providing Effective Substance Use Disorder Treatment (SUDT) to Parolees. People released from prison after serving a term for a serious or violent offense are generally supervised in the community by state parole agents. The state provides these parolees with access to a variety of rehabilitation services, including SUDT. Providing effective SUDT to parolees can have several benefits for both the people who receive these services (such as a lower risk of imprisonment and overdose) and the state (such as reduced prison costs). To be effective, SUDT must be delivered in a manner that is appropriate for the patient’s needs.

Parolee SUDT Primarily Provided Through California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR) Contracts. CDCR provides people who are on parole with access to CDCR‑funded rehabilitation programs by using its General Fund resources to contract with third parties to deliver specific services (such as SUDT). For example, Specialized Treatment for Optimized Programming (STOP) is a CDCR‑funded program that provides a range of services to parolees, but primarily focuses on SUDT. CDCR currently has agreements with four regional STOP contractors who (1)‑pay local providers to deliver services to parolees through subcontracts, (2)‑connect parolees with these providers, and (3)‑conduct oversight of the services provided to parolees.

Some Parolees Receive Medi‑Cal SUDT. Medi‑Cal (the state’s Medicaid program) provides funding to cover the costs of health care services—including SUDT—for low‑income families and individuals. The federal government provides reimbursement of up to 90‑percent of the cost for services provided to Medi‑Cal beneficiaries. Within the Medi‑Cal program, SUDT services are administered locally by counties. Counties generally pay for the costs of these services when they are provided and then submit their eligible expenditures to the state in order to receive federal reimbursement. Most parolees with a need for SUDT are eligible for treatment through Medi‑Cal.

Medi‑Cal SUDT Has Advantages Over CDCR’s SUDT for Parolees. Specifically, Medi‑Cal SUDT is better equipped to (1)‑provide medically appropriate SUDT to parolees for various reasons, such as offering a wider range of treatment options; (2)‑ensure continuity of service as it is available when people are discharged from parole; and (3)‑leverage federal funding to reduce state costs.

Recommend Increasing Utilization of Medi‑Cal for Parolee SUDT. Specifically, we recommend that the Legislature (1)‑direct CDCR to refer all parolees to medically appropriate SUDT, (2)‑require STOP providers to provide parolees with Medi‑Cal‑funded SUDT, (3)‑structure funding for parolee SUDT to streamline billing and reduce workload, and (4)‑use a portion of freed‑up funding to ensure costs are not shifted to counties and nonreimbursable services for parolees are maintained. We estimate that doing so will allow the state to achieve net savings of as much as $25‑million to $50‑million annually by leveraging federal reimbursements while also increasing the quality of services provided to parolees.

Introduction

When people are released from prison, they are generally supervised in the community for a period of time—usually between one to three years. While some of these people are supervised by county probation departments, people convicted of a serious or violent offense are generally supervised by state parole agents. The state provides these parolees with access to a variety of rehabilitation services, including substance use disorder treatment (SUDT).

As of February 28, 2021, there were 53,500 people on parole. Roughly 36,000 (or about two‑thirds) of those people are estimated to have a need for SUDT. Several studies have found that upon release from prison, people with substance use disorders have notably high risks of overdose relative to the general public—particularly in the first two weeks following release. In addition, untreated substance use disorders can also increase the likelihood of a person committing a new offense after being released from prison (known as recidivating).

Providing effective SUDT to inmates and parolees can have several direct and indirect benefits for both the people receiving the service and the state. Research has demonstrated that effective SUDT improves the lives of inmates and parolees by helping them avoid crime and the health effects of substance use—including death from overdose. In addition, effective SUDT has been found to reduce crime. This creates fiscal benefits for the state including reduced incarceration costs—as offenders will not return to prison—as well as reduced costs in providing various assistance to victims of crime. Moreover, when SUDT is provided in an effective manner, these benefits have been found to outweigh the costs of providing the service. To be effective, SUDT must be delivered in a manner that is appropriate for the patient’s needs. In addition, research has found that SUDT is more likely to be effective for people released from prison if it is provided both in prison and after they have been released.

In this report, we (1) provide background information on the various ways parolees access SUDT through providers who are typically either funded by the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR) or through Medi‑Cal (the state’s Medicaid program), (2) assess the trade‑offs between these two approaches, and (3) recommend steps to provide SUDT services to parolees in a more cost‑effective manner.

Background

Overview of Substance Use Disorder Treatment

Methods of Treating Substance Use Disorders. There are various methods of delivering SUDT treatment (typically called “modalities”). Each modality is geared to different types of patients’ needs and varies in the intensity and manner of service it provides. The major modalities include:

- Outpatient. Outpatient SUDT typically lasts a few months and consists of services provided for fewer than 9 hours per week—although some patients receive intensive outpatient SUDT that provides up to 20 hours of services per week. During this time, patients attend individual or group therapy sessions. For example, patients might attend cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT)—a form of therapy that is intended to help patients identify and adjust their thought processes regarding substance use to avoid future use. Patients generally do not need to live on‑site when receiving outpatient services.

- Residential. Residential SUDT typically lasts for a few months to up to a year based on patient needs. During this time, patients live on‑site and receive a structured schedule of services throughout the day. Treatment can include individual and group therapy sessions as well as additional services such as assistance from clinicians who monitor patient conditions while they go through withdrawal.

- Medication Assisted Treatment (MAT). People who are addicted to certain substances such as opioids or alcohol can develop a chemical dependency. This can result in strong physical cravings, withdrawal that interferes with treatment, and/or medical complications. MAT is intended to combine the services described above (such as CBT) with medications that address chemical dependencies to alcohol or opioids. Various types of medications can be used to provide MAT. Some of these medications can reduce the likelihood of a relapse by blocking the effects of the substance and potentially reducing cravings. In addition, some medications serve as a substitute to the substance to minimize the impacts of withdrawal while the patient works toward sobriety. Some patients receive medications for a short period of time to help gain medical stability, while other patients continue to receive MAT for many years to help maintain sobriety.

Overview of California’s SUDT Programs for Inmates and Parolees

In this section, we describe the SUDT services CDCR provides to both inmates and parolees, including how the type of in‑prison services inmates receive help determine the service they are referred to when they are released to parole.

CDCR Provides In‑Prison SUDT Programs

Historical Provision of SUDT in Prison. Until recently, CDCR’s in‑prison SUDT consisted primarily of CBT sessions a few hours a week for several months. Similar to other rehabilitation programs in CDCR, inmates were generally assigned to SUDT based on whether they had a “criminogenic” need for the program—meaning the inmate’s substance use disorder could increase their likelihood of committing a future crime if untreated. To determine criminogenic needs, nonmedical staff at CDCR use an assessment tool called the Correctional Offender Management Profiling for Alternative Sanctions (COMPAS). (This tool is also used for placement into other rehabilitation programs, such as anger management.) When administering COMPAS, staff collect an inmate’s basic demographic data, criminal history, and responses to dozens of interview questions that seek additional background information (such as the inmate’s education and work history). COMPAS uses this information to determine whether the inmate has a low, moderate, or high need for certain rehabilitation programs. In addition to placement based on criminogenic need, some inmates could be required to attend SUDT if they were caught using alcohol or illegal substances in prison.

New Integrated Substance Use Disorder Treatment Program (ISUDTP). As part of the 2019‑20 budget package, CDCR received funding to establish ISUDTP. When fully implemented, ISUDTP is intended to provide a continuum of care to inmates to address their SUDT and other rehabilitative needs. Accordingly, ISUDTP services include education, CBT, intensive outpatient treatment, and MAT when appropriate.

Under ISUDTP, inmates are assigned to SUDT based on whether they have a medical rather than criminogenic need. While there is significant overlap between inmates with a medical and criminogenic need for SUDT, the process for identifying the need and developing a treatment plan is different. To identify a medical need for SUDT, health care staff screen inmates for substance use disorders with the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) Quick Screen. The NIDA Quick Screen consists of a series of scored questions about prior substance use. The total points accrued indicate whether a treatment plan needs to be developed to address an inmate’s need.

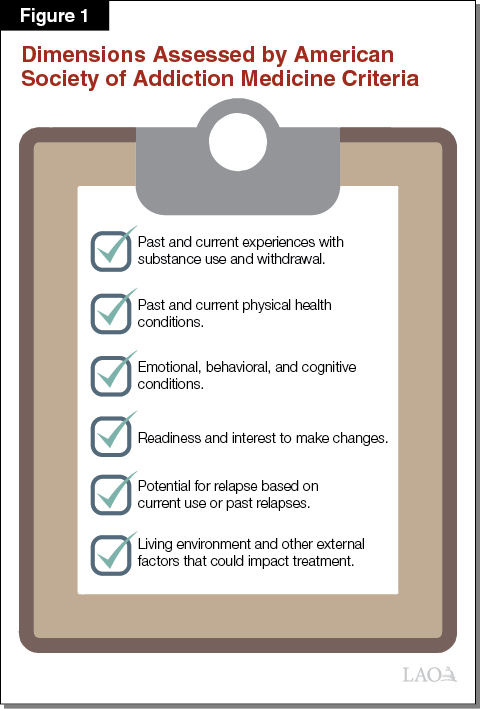

Treatment plans are developed utilizing the American Society of Addiction Medicine (ASAM) Criteria. The ASAM Criteria is a diagnostic tool that allows clinicians to assess six dimensions—such as the presence of other related medical and behavioral health conditions—that research has found can impact the effectiveness of SUDT modalities, as shown in Figure 1. By using the ASAM Criteria, medical staff are able to determine what treatment options are most appropriate for each patient, including whether they would benefit from MAT. CDCR has estimated that out of the total inmate population of about 112,000 inmates in 2019‑20, 67 percent had a substance use disorder and 32 percent could potentially benefit from MAT.

CDCR‑Funded Contracts Provide SUDT to Parolees

As previously mentioned, people released from prison after serving a term for a serious or violent offense are generally supervised in the community by state parole, with the remainder of people released generally supervised by county probation under what is known as Post‑Release Community Supervision. In addition to supervision, CDCR provides people who are on state parole with access to CDCR‑funded rehabilitation programs by using its General Fund resources to contract with third parties to deliver specific services (such as SUDT).

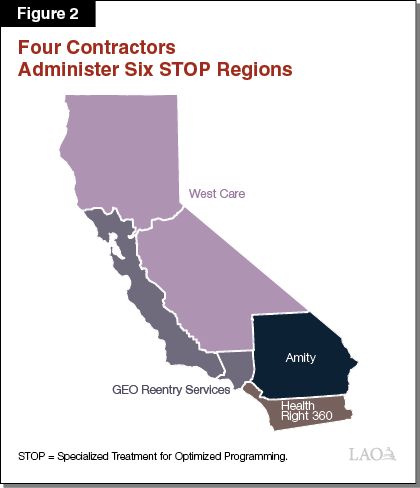

Specialized Treatment for Optimized Programming (STOP) Provides Most Parolee SUDT. STOP is a CDCR‑funded program that provides a range of services to parolees, but primarily focuses on various SUDT modalities. These modalities include residential and outpatient services but exclude MAT. CDCR currently has agreements with four nonprofit and private contractors that administer STOP at a regional level. These regional contractors (1) pay local providers to deliver services to parolees through subcontracts, (2) connect parolees with these providers, and (3) conduct oversight of the services provided to parolees. As shown in Figure 2, there are currently six STOP regions in California administered by these four contractors. For example, West Care currently serves as the regional contractor in most of Northern and Central California and subcontracts with various local providers in those counties to provide services to parolees.

Upon placement in STOP, parolees can receive services for up to 180 days. However, these services can be extended up to an additional 185 days if parolees are nearing the end of their initial treatment period and the provider and CDCR agree that additional SUDT is necessary. For example, a provider might identify that a parolee who is nearing the end of a 180‑day residential treatment period could benefit from additional time in residential or outpatient SUDT provided through STOP. The provider and regional STOP contractor would then submit a request to extend treatment to CDCR for approval.

The program’s total budget for 2020‑21 is $68 million General Fund. The cost per participant and the number of parolees who are served in a given year varies considerably. For example, CDCR reported serving about 8,000 parolees at a cost of roughly $8,300 per parolee in 2017‑18. In comparison, CDCR reported serving about 15,000 parolees at a cost of roughly $5,600 per participant in 2018‑19. These variations are due to a number of factors including (1) the modality of SUDT services provided, (2) the number of parolees who leave before completing the program thereby freeing up space for another parolee, and (3) the number of parolees who have their treatment extended beyond 180 days.

Other CDCR‑Funded Programs Offer Limited SUDT Services. While STOP is the main provider of SUDT services funded by CDCR, some parolees receive outpatient‑level SUDT through other programs provided under contract with CDCR, including day reporting centers (DRCs). DRCs operate in 21 counties and provide outpatient services for a variety of parolee needs in addition to SUDT. The program served about 8,900 parolees in 2018‑19, though many received non‑SUDT services, such as anger management. In addition, CDCR offers parolee service centers and transitional housing programs. These programs, which served about 2,000 parolees in 2018‑19, pair housing with reentry services such as job training and offer a limited amount of rehabilitation services which can include outpatient‑level SUDT.

Some Parolees Get SUDT Through Medi‑Cal Instead of CDCR‑Funded Programs

Overview of Medi‑Cal SUDT Services. Some parolees—particularly those receiving MAT—receive SUDT services outside of CDCR’s contracts. Usually these services are funded through Medi‑Cal, which is overseen by the state Department of Health Care Services (DHCS). Medi‑Cal provides funding to cover the costs of health care services for low‑income families and individuals. Medi‑Cal services are partially reimbursed by the federal government. The federal reimbursement rate for California is generally at least 50 percent of the costs for eligible services. However, the federal government provides reimbursement of up to 90 percent of the cost for services provided to certain Medi‑Cal beneficiaries. For example, the federal government currently pays 90 percent of the cost for services provided to Medi‑Cal beneficiaries who gained coverage in 2014 as a result of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA). The ACA provided states with the option to expand Medicaid eligibility to childless adults—through what became known in California as the ACA expansion. This group of Medi‑Cal beneficiaries is known as the “expansion population” and includes childless adults who make less than 138 percent of the federal poverty level.

Most people being released from prison qualify for Medi‑Cal and are often part of the expansion population. CDCR screens inmates before release and, as of 2019‑20, submits Med‑Cal applications for about 82 percent of inmates. Between July 2018 and June 2019 (the most recent data available), Medi‑Cal applications were submitted for about 29,900 of the 36,400 inmates who were released. Of the 29,900 applications submitted, about 24,000 (80 percent) were approved, 90 (less than 1 percent) were denied, and the remaining 5,700 (19 percent) were pending at the time of release.

Within the Medi‑Cal program, certain behavioral health care services, including SUDT, are administered locally by county behavioral health departments. Counties generally pay for the costs of these services when they are provided and then submit their eligible expenditures to DHCS in order to receive federal reimbursement.

Counties Work With Various Medi‑Cal‑Funded SUDT Providers. Similar to the regional STOP contractors, counties contract with providers who offer various SUDT modalities such as outpatient and residential services. In order to enter a contract with a county, providers must first be licensed and certified by DHCS.

Medi‑Cal‑Funded SUDT Also Available Outside County Contracts. In addition to these county‑contracted providers, parolees can also receive outpatient SUDT and MAT through Medi‑Cal from other providers in the community. These providers include:

- Community health centers provide many parolees with health care (which can include SUDT). These centers utilize various federal, state, and local funding sources—including Medi‑Cal—to provide services to people. We note that some community health centers choose to become county‑contracted providers.

- Other community providers, such as private primary care providers, can offer parolees SUDT services so long as the provider accepts Medi‑Cal and is authorized to provide those services. For example, in order for a provider to be authorized to provide MAT to an eligible parolee, they must meet federal requirements for prescribing the medication.

We note that some providers, including many of the community health care centers, participate in a network that tailors services to address the needs of people recently released from prison.

Services Eligible for Federal Reimbursement Vary by County. The types of SUDT services eligible for federal reimbursement through Medi‑Cal vary by county based on which Medi‑Cal delivery system is used. Specifically, counties can choose from one of the two following systems:

- Standard Drug Medi‑Cal. In standard Drug Medi‑Cal counties, federal Medicaid reimbursement for residential SUDT services is limited to services provided to perinatal women in facilities with no more than 16 beds. Rates providers receive for SUDT services are based on the costs of providing services up to a statewide maximum. For example, as of 2018, the maximum rate for residential services is about $90 per day. To the extent a particular provider’s costs exceed this maximum rate, they may choose not to provide services to Medi‑Cal patients.

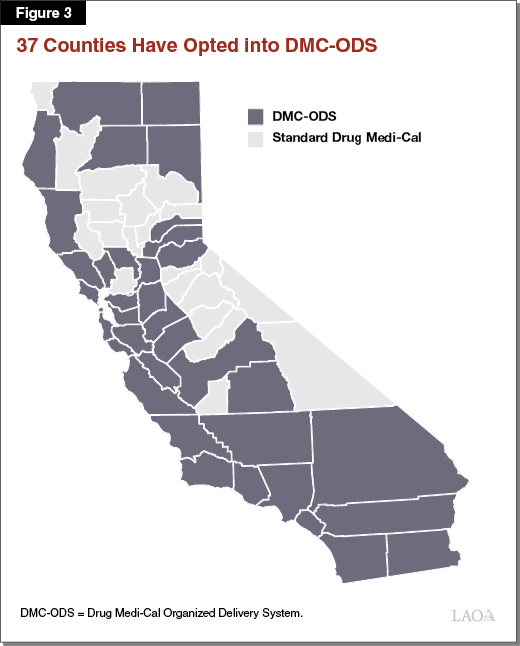

- Drug Medi‑Cal Organized Delivery System (DMC‑ODS). Counties that have opted into DMC‑ODS operate under a waiver of certain federal rules that allow them to draw down federal funding for SUDT services not eligible for reimbursement under standard Drug Medi‑Cal. This allows counties to offer a wide variety of additional SUDT services, including case management, withdrawal management, and several forms of MAT medication not available under standard Drug Medi‑Cal. Treatment plans are developed based on the ASAM criteria. The waiver also allows for residential SUDT facilities to have more than 16 beds. Counties that opt into DMC‑ODS also have the ability to propose county‑specific rates that ensure they cover the costs of providing SUDT. This provides counties with greater flexibility to adjust their rates based on local costs—allowing counties in high cost areas to attract more providers. For example, in one DMC‑ODS county, the median rate for residential services was $124 per day, which is much higher than the $90 daily reimbursement for standard Drug Medi‑Cal. As shown in Figure 3, DMC‑ODS has been widely adopted throughout California. Currently, 37 counties have opted into DMC‑ODS. Roughly 95 percent of parolees live in these counties.

Referral and Placement Into Parolee SUDT Programs

In this section, we describe how parolees are referred and placed into SUDT services in the community, which depends on a variety of factors.

Referral Process

There are three main ways that a person being released from prison into parole supervision can be referred to SUDT. Before leaving prison, inmates being released to parole go through a pre‑release planning process, which can include referrals to SUDT providers in the community. Typically, these referrals are to CDCR‑funded providers. In addition, CDCR is in the process of implementing a separate process (known as enhanced pre‑release planning) to refer certain inmates—such as those receiving MAT—to a broader range of SUDT providers—including Medi‑Cal‑funded providers. Finally, after being released from prison, parolees can also be referred to SUDT by their parole agents or by navigating the process on their own.

Standard Pre‑Release Planning Process. Inmates being released to parole typically go through a pre‑release planning process once they are within 90 to 210 days of release. (When inmates enter prison, a similar process is used to place them into in‑prison programs.) Specifically, a Parole Services Associate (PSA) meets with the inmate to develop a case plan for addressing the inmate’s criminogenic needs once they are on parole as identified by COMPAS Reentry (an assessment similar to COMPAS but designed for parolees). While COMPAS Reentry determines whether a person has a low, moderate, or high criminogenic need for SUDT, it does not provide guidance on the treatment modality that is appropriate for that person. For example, COMPAS Reentry does not indicate whether a parolee’s need for SUDT would be best addressed through an outpatient or residential program or whether MAT is appropriate.

Enhanced Pre‑Release Planning. Because some inmates released to parole need services (such as MAT) that are not available through CDCR‑funded SUDT programs, CDCR currently takes steps on a case‑by‑case basis to ensure that these inmates are connected to appropriate services in the community and are approved for Medi‑Cal when applicable. As part of ISUDTP, CDCR is in the process of creating a more formal enhanced pre‑release planning process intended to provide more comprehensive pre‑release planning services including connecting inmates to programs in the community—such as Medi‑Cal funded programs—that are not under contract with CDCR. This process would be focused on certain inmates, including those who (1) currently receive MAT, (2) have a high medical need for SUDT as identified by medical staff using the NIDA Quick Screen and ASAM criteria, and/or (3) have been convicted of crimes with a nexus to substance use disorder and who do not have an SUDT placement by the time they are within 90 days of release. This process would involve a multidisciplinary team—including nursing staff and social workers (rather than just a PSA)—conducting a comprehensive plan for the rehabilitative and health care services that the inmate will receive upon release. As part of these planning activities, the team would ensure inmates are enrolled in programs like Medi‑Cal and referred to either CDCR‑funded or Medi‑Cal‑funded SUDT providers in the community by the time of their release. According to CDCR, it has started working with all 58 counties to help ensure that the process will allow for inmate needs to be met once they are released.

Referral Processes While on Parole. In addition to being referred to SUDT programs prior to being released from prison, parolees who are already in the community can be referred to SUDT by their parole agent or choose to access these services on their own. Parole agents can refer them to CDCR‑funded SUDT programs under a number of circumstances, including in response to a request from the parolee or in response to a substance use related parole violation. Parole agents also have the flexibility to refer parolees to non‑CDCR‑funded programs such as Medi‑Cal‑funded SUDT providers. However, CDCR lacks a formal process for making or keeping track of referrals to non‑CDCR‑funded SUDT. In addition, parolees can also choose to access non‑CDCR‑funded SUDT on their own. For example, as county residents, parolees can seek out treatment through county behavioral health departments without first being referred by their parole agents.

Placement Into Services

Once a parolee has been referred to a provider, the provider determines what services should be offered to the parolee. This placement process varies depending on whether the provider is funded by CDCR or Medi‑Cal.

Placement Into CDCR‑Funded SUDT. CDCR provides limited guidance to the providers it funds on how they should determine what services to provide parolees. As a result, providers take different approaches when placing parolees into services. For example, while some CDCR‑funded providers administer COMPAS again or similar tools to identify criminogenic need, others might use tools such as the ASAM Criteria to develop a treatment plan.

Placement Into Medi‑Cal‑Funded SUDT. When parolees are referred to a Medi‑Cal provider, they are assessed to determine what services are appropriate based on medical necessity and then placed into treatment based on the assessment like any other Medi‑Cal patient. In addition to ensuring the parolee gets the appropriate services, making treatment decisions based on medical necessity is required in order to ensure the services are reimbursable through Medi‑Cal. For example, in DMC‑ODS counties, providers are required to use the ASAM Criteria when developing treatment plans.

Medi‑Cal SUDT Has Advantages Over CDCR’s SUDT for Parolees

As discussed above and summarized in Figure 4, there are key similarities and differences between CDCR and Medi‑Cal SUDT services for parolees. Based on our review of the differences, we find that SUDT provided through Medi‑Cal has several advantages over CDCR‑funded SUDT. Specifically, Medi‑Cal‑funded SUDT (1) provides care based on medical necessity, (2) allows care to continue beyond parole, and (3) makes greater utilization of federal funding.

Medically Appropriate Levels of Care

CDCR‑Funded SUDT Does Not Always Result in Medically Appropriate Level of Care. We find that CDCR’s ability to provide medically appropriate care to parolees through its SUDT programs is limited. This is primarily due to three factors:

- Referrals Not Based on Medical Necessity. Referrals based on COMPAS Reentry focus on criminogenic need rather than medical necessity. In addition, PSAs have indicated that they do not always rely on COMPAS Reentry and sometimes make referrals to residential SUDT programs based on other nonmedical factors, such as a whether an inmate has a need for temporary housing upon release.

- Medically Appropriate Treatment Plans Not Always Developed. Once a parolee is referred to CDCR‑funded SUDT, providers are expected to develop treatment plans. However, there is a lack of consistency between providers when developing these plans. As previously discussed, this is because providers receive limited guidance from CDCR on how to make treatment decisions. Accordingly, some providers utilize criminogenic assessments that are not designed to create medically appropriate treatment plans. For example, COMPAS Reentry cannot determine whether outpatient or residential treatment is appropriate for a particular parolee.

- Certain Services Not Available. CDCR‑funded SUDT for parolees does not provide certain SUDT services such as MAT, case management, and post‑treatment care after a parolee completes the program. In order to receive these services, a parolee needs to seek treatment outside of the CDCR‑funded providers, such as by going to a Medi‑Cal‑funded provider. While CDCR is currently establishing a process to connect some inmates to Medi‑Cal services prior to release from prison, this process would not apply to parolees who are already in the community. Furthermore, as we discuss in the nearby box, the Legislature recently adopted legislation to incentivize parolees to participate in MAT. This will likely result in more parolees being interested in MAT—making it even more important for them to be able to easily access this service.

Incentive for Parolees to Participate in Medication Assisted Treatment (MAT)

Chapter 325 of 2020 (AB 1304, Waldron) established an incentive program for certain people on parole to participate in substance use disorder treatment (SUDT) programs including MAT. For each six months of treatment completed, eligible parolees can receive a 30‑day reduction in the length of their parole—up to a maximum of 90 days. As such, this program could result in more parolees seeking Medi‑Cal‑funded SUDT since the SUDT programs funded through the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation do not provide MAT.

As a result of the above factors, many parolees may not be receiving SUDT modalities that are appropriate for their needs. Providing an inappropriate level of service not only results in an ineffective use of resources, it can also be counterproductive. For example, a parolee referred to residential SUDT based on a need for housing might not need that level of SUDT. In fact, the structured nature of residential SUDT could make it more challenging for the parolee to engage in other activities that are critical to success, such as seeing their family, going to school, or working. In addition, because the number of parolees who can be treated in residential SUDT is limited, it could prevent another parolee who does have a need for residential treatment from receiving services.

Medi‑Cal Services Provide Medically Appropriate Levels of Care. Unlike CDCR‑funded SUDT for parolees, referrals and treatment plans for Medi‑Cal services must be medically appropriate. This ensures that patients receive the correct level of care and that treatment decisions are made in a consistent manner based on the needs of the patient rather than varying based on the PSA or provider. Moreover, because Medi‑Cal providers can offer a range of services beyond those funded by CDCR, they are better equipped to provide medically appropriate SUDT. For example, Medi‑Cal providers in DMC‑ODS counties can provide MAT, case management, and post‑treatment recovery services (such as follow‑up calls from the provider after completing outpatient or residential services).

Continuity of Service

CDCR‑Funded Services Only Available During Parole Term. Once individuals are discharged from parole, they generally can no longer receive services from their CDCR‑funded provider. If these individuals need to continue or resume services due to unresolved SUDT needs or a relapse, it is ultimately their responsibility to find treatment. This is problematic because when left untreated, substance use disorders and relapses can have serious health or criminal consequences. In particular, relapse following treatment can result in an increased likelihood of overdose. This is because, after treatment, people generally have lower tolerances for their drugs of choice. Moreover, as discussed in the box below, recent legislation that reduces the amount of time people spend on parole could have implications for continuity of care. This is because people will have less time to access or resume CDCR‑funded SUDT before being discharged from parole.

Reduced Length of Parole Terms

Chapter 29 of 2020 (SB 118, Committee on Budget and Fiscal Review) established an opportunity for parolees to earn early discharge after one year of parole based on good behavior. Chapter 29 also established maximum parole terms of two or three years for most parolees. (Previously, parole terms were generally set at three or more years.) Due to the reduced length of parole, there is a greater likelihood for parolees to be discharged from parole before having their substance use disorder treatment needs fully met. To continue treatment after being discharged from parole, these people will need to seek treatment elsewhere, such as from Medi‑Cal providers.

Medi‑Cal Services Have Potential Continuity of Care Advantages. Because Medi‑Cal is not specifically for parolees, people who receive Medi‑Cal‑funded SUDT while on parole could continue or resume those services after being discharged from parole. For example, if people receive Medi‑Cal‑funded SUDT while on parole, their coverage for SUDT continues even after being discharged from parole. As such, people discharged from parole could continue receiving services such as case management and aftercare from the same provider they were receiving services from while on parole. In view of the above, Medi‑Cal is better equipped to help ensure continuity of care following parole discharge and potentially for several years after. This could help prevent further serious health or criminal consequences resulting from substance use disorders.

Currently, residential SUDT provided to adults through Medi‑Cal is typically limited to no more than two nonconsecutive 90‑day periods in a year, in contrast to STOP services, which can be provided for as long as a full year. However, as part of the Governor’s California Advancing and Innovating Medi‑Cal (CalAIM) proposal—a far‑reaching set of reforms to expand, transform, and streamline Medi‑Cal service delivery and financing—the administration proposes to remove this restriction on the provision of Medi‑Cal residential SUDT services. If approved, Medi‑Cal residential SUDT services could be provided for longer periods of time than STOP services if medically necessary. (In addition to approval from the Legislature, this change would also require federal approval. More information about CalAIM can be found in our publication The 2021‑22 Budget: CalAIM: The Overarching Issues.)

Utilization of Federal Funding

CDCR Does Not Utilize Federal Funding. While most parolees are eligible for Medi‑Cal and many SUDT services provided through STOP are similar to Medi‑Cal funded services that receive federal reimbursements, CDCR does not draw down any federal funding for parolee SUDT. According to CDCR, it attempts to leverage Medi‑Cal when applicable and some STOP providers have a number of beds set aside to provide Medi‑Cal‑funded treatment to eligible patients including parolees. However, the department is unable to provide information on the number of parolees placed into the Medi‑Cal‑funded beds and does not have a process to ensure providers use Medi‑Cal funding before seeking funding through CDCR. Moreover, contractors who administer STOP in multiple regions of the state indicate that it is uncommon for providers within their networks to offer Medi‑Cal‑funded beds. This means that the state must bear the full cost of these services instead of drawing down federal funding through Medi‑Cal to cover a portion of the cost.

Medi‑Cal Funded Programs Draw Down Additional Federal Funding. Up to 90 percent of Medi‑Cal‑funded SUDT expenditures are reimbursed by the federal government, resulting in the state and local governments paying substantially less than the full cost of the service provided. For example, in Santa Barbara County, the full cost of providing outpatient SUDT is relatively similar between STOP and Medi‑Cal—$135 for one session through STOP and $130 (median rate) for one session through Medi‑Cal. However, the nonfederal share of the Medi‑Cal funded session is $65 if the federal government reimburses 50 percent of the cost and only $13 if the federal government reimburses 90 percent of the costs. (As discussed earlier, most parolees are part of the Medi‑Cal expansion population, for which the federal government reimburses 90 percent of the costs.) In either case, after federal reimbursements, the nonfederal share of a Medi‑Cal‑funded outpatient session is substantially less expensive than the session provided through STOP. As such, leveraging Medi‑Cal to provide parolees with SUDT would likely be considerably less costly to the state than CDCR’s current approach of paying the full cost of SUDT directly.

Recommend Increasing Utilization of Medi‑Cal for Parolee SUDT

In order to capitalize on the advantages of Medi‑Cal‑funded SUDT programs for parolees, we recommend a series of steps to increase the utilization of these programs as compared to the CDCR‑funded SUDT programs. Specifically, we recommend that the Legislature (1) direct CDCR to refer all parolees to medically appropriate SUDT, (2) require STOP providers to provide parolees with Medi‑Cal‑funded SUDT, (3) structure funding for parolee SUDT to streamline billing and reduce workload, and (4) use a portion of freed‑up funding to ensure costs are not shifted to counties and nonreimbursable services for parolees are maintained. We find that these steps will improve parolee SUDT while allowing the state to draw down additional federal funding.

Connect All Parolees With Medically Appropriate SUDT. In order to connect all parolees with medically appropriate SUDT, we recommend the Legislature require CDCR to:

- Ensure that all eligible inmates entering parole are enrolled in Medi‑Cal.

- Conduct all parolee SUDT referrals for inmates preparing for reentry and parolees already in the community in a manner consistent with ISUDTP. Specifically, CDCR and providers should use the NIDA Quick Screen and ASAM Criteria when identifying needs and creating treatment plans.

- Ensure that the prerelease planning processes being established as part of ISUDTP are robust enough to accommodate all parolees and ensure there is no gap in SUDT services when parolees are released from prison.

- Refer all parolees with SUDT needs to Medi‑Cal providers—including parolees who would not typically be eligible for Medi‑Cal. This would ensure that all parolees receive the benefits of medically appropriate SUDT while also eliminating the need to maintain two separate SUDT systems. As we discuss below, this approach would have some implications on providers and funding for SUDT.

Require STOP Providers Become Medi‑Cal Providers and Ensure Continuity of Care. We recommend that the Legislature direct CDCR to require all STOP providers to become Medi‑Cal‑funded providers. This would help ensure that there are sufficient Medi‑Cal‑funded providers in the community and that parolees receive medically appropriate SUDT based on their needs. We also recommend directing CDCR to require that STOP providers take steps to help ensure continuity of care after parolees are discharged from parole. The Legislature could implement these changes by requiring CDCR to include provisions in the regional STOP contracts requiring the regional contractors to only subcontract with providers that:

- Provide services in a manner that is consistent with Medi‑Cal, including placing parolees in services based on medical necessity.

- Become licensed and certified by DHCS to provide residential SUDT.

- Become contracted Medi‑Cal providers through county departments of behavioral health.

- Help ensure continuity of care by working with parolees to develop a plan for continued access to services after completion of parole as necessary.

We note that implementing these changes could result in additional workload and costs for providers who switch over to Medi‑Cal. For example, providers might need to make adjustments to their operations such as such as switching over from CDCR’s administrative processes to Medi‑Cal processes. In addition, there could be funding implications for providers due to potential differences in the Medi‑Cal rates set by counties and the rates providers currently receive from the regional STOP contractors. However, we note that counties generally set Medi‑Cal rates based on the costs of providing services and have processes to adjust these rates to reflect changes in provider costs.

Structure Funding to Streamline Billing and Reduce Workload. Currently, STOP providers submit their expenditures for reimbursement to the regional STOP contractors who then bill CDCR. Instead, we recommend requiring these providers to submit their expenditures for reimbursement to county behavioral health departments who would then submit their expenditures to DHCS for either state or federal reimbursement. This is the process currently used by Medi‑Cal and would ensure that Medi‑Cal eligible services are being billed appropriately. In addition, this approach minimizes potential workload increases for providers because they would only need to bill the counties rather than having to bill some services through the counties and some services through the regional STOP contractors. This would eliminate the need for funding for services provided to parolees to pass through the regional STOP contractors. However, CDCR would continue to need to use these contractors to connect parolees with providers upon release and conduct oversight of the non‑SUDT services provided to parolees.

Under this funding structure, expenditures on parolee SUDT would shift from CDCR to Medi‑Cal. As such, CDCR would no longer need the full $68 million (General Fund) currently allocated to the STOP program. (We note that CDCR would continue to need some of this funding to contract with regional STOP contractors, with the amount depending on negotiations between CDCR and the contractors.) Shifting parolee SUDT costs to Medi‑Cal would result in an increase in Medi‑Cal spending. However, utilizing Medi‑Cal would allow for federal reimbursements for a significant portion of these costs. The actual amount of reimbursements available would depend on (1) the level of expenditures on parolee SUDT in a given year, (2) the percent of those costs eligible for federal reimbursement, and (3) the extent to which parolees qualify for federal reimbursement at a rate of 50 percent or 90 percent. Assuming parolee SUDT expenditures remain at around $68 million, we estimate that federal reimbursements could cover between roughly $25 million and $50 million of parolee SUDT costs.

Ensure Costs Are Not Shifted to Counties and Nonreimbursable Services Maintained. Currently, the nonfederal share of Medi‑Cal SUDT costs is paid for with a combination of state and county funding. However, in order to avoid passing the nonfederal share of parolee SUDT costs onto counties, the Legislature could direct DHCS to pass any costs to CDCR for STOP services that are billed through Medi‑Cal and not eligible for federal reimbursement. We estimate that the nonfederal share of these services currently could be between $18 million and $43 million annually. A portion of CDCR’s current allocation for STOP of $68 million could be used to pay for these costs. These costs include:

- The nonfederal share of costs for Medi‑Cal eligible services provided to parolees—which would be 10 percent of the cost of SUDT services for most parolees.

- Costs for SUDT services provided to parolees who are not eligible for Medi‑Cal.

- Key services generally not covered by Medi‑Cal, such as temporary housing for parolees participating in residential SUDT and any services providers offer to address non‑SUDT criminogenic needs, such as anger management.

Conclusion

Parolees with untreated substance use disorders can experience negative health impacts and are at increased risk of recidivism. However, effectively providing SUDT has been found to reduce these impacts. Moreover, the benefits of effectively providing SUDT often outweigh the costs. As we discuss in this report, providing SUDT through Medi‑Cal has multiple advantages over the CDCR‑funded SUDT. Specifically, providing SUDT through Medi‑Cal ensures parolees receive medically appropriate care while also drawing down additional federal funding. As such, by increasing the utilization of Medi‑Cal for parolee SUDT, we estimate that the state can achieve net savings of as much as $25 million to $50 million annually by leveraging federal reimbursements while also increasing the quality of services provided to parolees.