LAO Contact

May 9, 2019

The 2019-20 Budget

Analysis of the Governor’s Mental Health Workforce Proposal

Summary

Governor Proposes $50 Million in One‑Time General Fund for Mental Health Workforce. To ameliorate what the Governor considers to be statewide and regional shortages of mental health professionals, the Governor has proposed a $50 million one‑time General Fund augmentation for existing state programs that provide scholarships and student loan repayment for mental health professionals who agree to work in underserved areas. This brief analyzes the Governor’s proposal.

Mixed Evidence of Statewide Mental Health Workforce Shortages . . . First, we provide basic background on mental health services delivery, funding, and workforce. Following our preliminary review, we find mixed evidence of a statewide shortage for mental health professionals overall. While certain mental health workforce projections show the state is likely to experience a shortage, other evidence we reviewed does not suggest this to be the case. That said, we find stronger evidence that the state could be experiencing a shortage of psychiatrists.

. . . But Regional Disparities in the Supply of Mental Health Professionals Exist. While the evidence is mixed regarding the presence of a statewide mental health workforce shortage, the evidence is strong that significant regional disparities exist in the supply of mental health professionals. Notably, regions such as the Inland Empire and the San Joaquin Valley have significantly fewer mental health professionals per capita than the state as a whole.

Options for Legislative Consideration. We provide several options for the Legislature to consider as it decides whether to approve the Governor’s proposal. The first option is to take pause and identify the state’s most critical mental health workforce needs and the most cost‑effective strategies for ameliorating them. Exercising this first option would involve delaying funding until many of the outstanding uncertainties related to the state’s mental health workforce strategies are better understood. The second option is to approve the Governor’s proposal, but add parameters to ensure the funding is targeted toward the areas of greatest need. The third option is to provide funding but through approaches that differ from the Governor’s. Examples of alternative approaches include (1) funding programs that more specifically support the education and training of new mental health professionals—such as funding new psychiatry residency slots—or (2) giving counties flexible funding for the delivery of mental health services.

Introduction

The Governor proposes a $50 million one‑time General Fund augmentation for existing mental health workforce programs that are administered by the Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development (OSHPD). This brief (1) provides background on the state’s mental health workforce, (2) gives an overview of existing programs and funding aimed at improving the state’s mental health workforce, (3) summarizes and assesses the Governor’s proposal, and (4) provides options for legislative consideration.

Background

In this section, we provide a brief overview of public community mental health services delivery and funding in California. We then provide background on the various professions that provide mental health services. Finally, we briefly summarize the history of mental health workforce funding in the state.

Community Mental Health Services

Defining Community Mental Health. Mental health services include the diagnosis and treatment for individuals experiencing mental illness. Common mental health diagnoses include depression and schizophrenia. Common treatments include therapy, crisis intervention and stabilization, medication, and inpatient psychiatric services. As used in this report, “community mental health services” generally comprise all mental health services delivered in community settings, thereby excluding those delivered in certain other settings, notably correctional settings. Community mental health services are commonly paid for by both private and public health insurance. According to 2015 national estimates, private sources—such as commercial health insurance—paid for about one‑third of mental health services. Medicaid accounts for another one‑third of spending and Medicare and other public sources comprise the remaining one‑third.

In California, Public Community Mental Health Services Are Primarily Delivered and Funded Through Counties. In California, counties play a major role in the funding and delivery of public mental health services. In particular, counties are generally responsible for arranging and paying for community mental health services for low‑income individuals with the highest mental health needs. Counties deliver these services through a mix of county mental health staff and contracted providers. In 2018‑19, counties are receiving $9.3 billion in funding for community mental health services. About half of funding for county mental health services is provided through block grants that grow on an annual basis in line with state tax revenues. Federal Medicaid funding makes up most of the remaining funding.

Recent Policy Changes Have Likely Led to an Increase in Demand for Mental Health Services and Providers. Demand for community mental health services has very likely increased over the last several years, in large part due to the federal Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA), implemented in 2014. Under the ACA, California has experienced significant increases in the number of residents with health insurance, which has likely increased state residents’ willingness and capacity to seek mental health services. Funding for public community mental health services has also increased in recent years. Since the ACA was implemented, total annual funding for county mental health services has increased by 71 percent, from $5.5 billion to $9.3 billion.

Mental Health Professions

A Variety of Professions Provide Mental Health Services. In an effort to ensure quality care, state laws restrict the delivery of mental health services to licensed providers. Such licensure requirements generally impose minimum education and work‑experience standards for providers to be allowed to practice independent of supervision. State law permits a variety of professions to deliver mental health services and establishes scope of practice rules for which types of services different professions may provide. For example, psychiatrists may prescribe medicine and provide a variety of diagnostic and therapeutic services. Psychologists, by contrast, may not prescribe medicine but may provide a similar array of diagnostic and therapeutic services as psychiatrists. Figure 1 summarizes the professions specializing in the delivery of mental health services.

Figure 1

A Variety of Professions Specialize in the

Delivery of Mental Health Services

|

Profession |

Education Requirement |

|

Can Prescribe Medication |

|

|

Psychiatrist |

Medical degree |

|

Psychiatric nurse practitioner |

Master’s or doctorate |

|

Cannot Prescribe Medication |

|

|

Psychologist |

Professional doctorate |

|

Clinical counselor |

Master’s |

|

Clinical social worker |

Master’s |

|

Marriage and family therapist |

Master’s |

|

Psychiatric mental health registered nurse |

Master’s |

|

Psychiatric technician |

High school diploma |

Existing Mental Health Workforce Programs

State Administers a Variety of Mental Health Workforce Programs. Since even before the ACA, state policymakers have had concerns about the capacity of the state’s mental health workforce to meet demand for services. To address these concerns, the state and counties administer a variety of programs aimed at improving the overall supply, geographic distribution, and diversity of the state’s mental health workforce. Often, these existing programs offer (1) scholarships or stipends (as high as $25,000) for prospective mental health professionals still completing their education or (2) student loan repayment (as high as $105,000) for practicing mental health professionals. In general, these existing programs are designed to support the workforce needs of the public community mental health system as well as some types of private providers that largely serve low‑income populations. These existing programs include service obligations where recipients must work at an eligible location for a specified period of time—typically one‑to‑two years—or otherwise repay the scholarship, stipend, or loan repayment assistance. Eligible locations include practice sites located in designated shortage areas as well as certain safety‑net clinics that serve low‑income and other high‑need populations, regardless of whether they are located in designated shortage areas. Other existing state programs are aimed at improving educational and training capacity. These programs, for example, provide funding for residency programs or clinical rotations—a necessary component in the training of at least certain mental health professionals.

Funding Specifically Dedicated to State Mental Health Workforce Programs Largely Expired in 2017‑18. The Mental Health Services Act (MHSA), approved by voters in 2004, places a 1 percent surtax on incomes over $1 million and dedicates the revenue to mental health services. A total of $445 million in MHSA revenues from the act’s initial years was set aside on a limited‑term basis to fund state and county workforce initiatives. Roughly half of this funding was administered at the state level (most recently, by OSHPD), with the other half going directly to counties to administer. The state and counties had through 2017‑18 to spend this $445 million. To continue funding into 2018‑19, the Legislature appropriated $11 million in one‑time MHSA funding for state mental health workforce programs.

OSHPD Is Responsible for Creating Five‑Year Mental Health Workforce Plans. In addition to operating mental health workforce programs, OSHPD is responsible for developing five‑year plans outlining strategies to meet the state’s mental health workforce education and training needs. OSHPD’s most recent five‑year plan was released in early 2019. Historically, the MHSA funding described in the previous paragraph supported the funding priorities outlined in the five‑year plans. Given the expiration of the MHSA funding in 2017‑18, there is no longer funding specifically dedicated to supporting the 2019 five‑year plan.

Counties Free to Dedicate up to 15 Percent of MHSA Revenue to Local Workforce Programs. The MHSA authorizes, but does not require, counties to spend a portion of their MHSA revenues on workforce development activities. The maximum amount of MHSA revenues that counties can spend on workforce development activities is around 15 percent of total MHSA revenues, though we would note that this 15 percent ceiling includes the total funding counties may dedicate to certain other purposes as well—namely to capital and technology acquisition and development and prudent reserves. Were counties to devote one‑third of allowable MHSA funding to workforce programs, for example, almost $100 million annually in MHSA funding could be used. It is our understanding that counties have not generally chosen to devote significant MHSA funding to local mental health workforce development. In large part, this is likely due to the fact that the MHSA specifically dedicated a significant portion of MHSA revenues from the act’s early years to workforce development.

Governor’s Proposal

$50 Million One‑Time General Fund to Improve Mental Health Workforce. The Governor’s budget proposes $50 million in one‑time General Fund for existing state mental health workforce programs administered by OSHPD. Figure 2 lists the mental health professions that the funding would support. The funding would be available through 2025‑26. The funding is intended to ameliorate what the Governor considers to be statewide and regional shortages of mental health professionals.

Figure 2

A Variety of Mental Health Professionals Would

Receive Support Under the Governor’s Proposal

|

Student Loan Repaymenta |

Scholarshipb |

|

|

Clinical counselor |

✓ |

|

|

Clinical social worker |

✓ |

✓ |

|

Community health worker/ promotora |

✓ |

✓ |

|

Consumer/ peer counselor |

✓ |

|

|

Marriage and family therapist |

✓ |

|

|

Medical assistant |

✓ |

✓ |

|

Mental health administrative staff |

✓ |

|

|

Physician assistant |

✓ |

✓ |

|

Psychiatric mental health registered nurse |

✓ |

✓ |

|

Psychiatric nurse practitioner |

✓ |

✓ |

|

Psychiatrist |

✓ |

|

|

Psychologist |

✓ |

|

|

Rehabilitation counselor |

✓ |

|

|

aStudent loan repayment programs that would receive funding under the Governor’s proposal include the Advanced Practice Healthcare Loan Repayment Program, Allied Healthcare Loan Repayment Program, Licensed Mental Health Services Provider Education Program, Mental Health Loan Assumption Program, State Loan Repayment Program, and Steven M. Thompson Physician Corps Loan Repayment Program. bScholarship programs that would receive funding under the Governor’s proposal include the Allied Healthcare Scholarship Program and Advanced Practice Healthcare Scholarship Program. |

||

Assessment

In this section, we provide our assessment of the magnitude and geographic distribution of potential mental health workforce shortages and the likely impact of the Governor’s proposal in ameliorating these potential shortages.

Mixed Evidence of Statewide Mental Health Workforce Shortages

Projections From Academic Researchers Predict the State Could Face a Shortage of Mental Health Professionals. Researchers at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) project that, unless the total number of people entering mental health professions in the state increases, California would face a shortage of mental health professionals between 2016 and 2028. If the total number of people entering mental health professions does not increase, these projections show that the supply of mental health professionals could fall short of demand for mental health professionals by between 12 percent and 40 percent by 2028. As we describe below, the state has recently experienced growth in the number of masters‑ and doctoral‑level professional mental health graduates. (Professional mental health graduates generally include those intending to pursue careers in clinical care as opposed to research.)

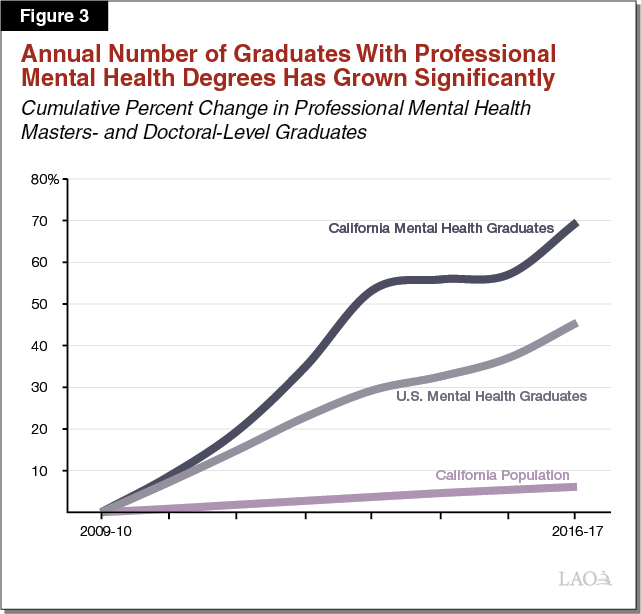

Recent Growth in Professional Mental Health Graduates Brings Uncertainty to Whether the State Is Facing a Shortage. To see whether the number of people entering mental health professions has in fact remained constant in recent years (which would suggest that the education and training of new mental health professionals is likely not meeting the state’s workforce needs), we reviewed data on the number of individuals graduating with professional masters or doctoral degrees in mental health‑related fields from California universities. As shown in Figure 3, from 2009‑10 to 2016‑17, the annual number of professional degree graduates in the fields of clinical psychology, social work, counseling, and psychiatric nursing increased from 4,700 to around 8,000—a 70 percent increase. (Over this same time period, California’s resident population increased by about 6 percent.) If sustained, this increase in the number of graduates may, but is not guaranteed to, significantly ameliorate the projected mental health workforce shortage that does not necessarily assume an increase. More than 80 percent of the increase in professional mental health graduates is from graduates of private universities in the state, which do not rely on augmentations in state funding to grow enrollment.

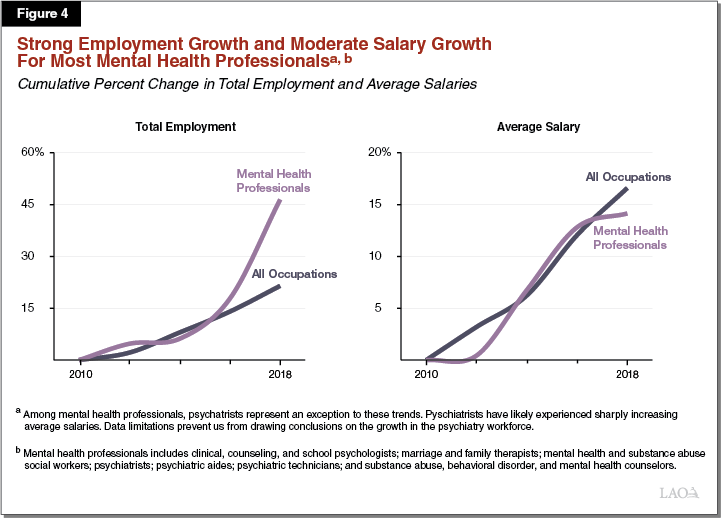

Moderate Salary Growth for Mental Health Professionals Does Not Suggest There Is a Statewide Shortage. In addition, we would expect that a shortage of mental health professionals might lead to sharply rising salaries for mental health professionals as hospitals, clinics, counties, and other organizations compete to fill needed mental health positions. We reviewed data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics, which showed that between 2010 and 2018 mental health professionals’ average salaries have increased in California at about the same rate as all occupations throughout the California economy, contrary to what we would expect under a shortage. Moreover, over this same time period, the number of mental health professionals has increased by about 50 percent. Figure 4 displays these trends for mental health professionals compared to all occupations. These trends overall do not suggest that the state is facing a statewide shortage of mental health professionals.

Stronger Evidence of Inadequate Supply of Psychiatrists Statewide. Evidence from a variety of sources suggest that California may currently or in the near future face a shortage of psychiatrists. UCSF researchers found that a significant number of psychiatrists are nearing retirement age. In addition, Bureau of Labor Statistics data do not show an increase in the number of psychiatrists in the state between 2010 and 2018. At the same time, average psychiatrists’ salaries appear to have increased to a much greater degree than all occupations throughout California, suggesting there could be significant competition for a potentially limited number of psychiatrists in the state. We would note that non‑psychiatrists, such as psychologists and psychiatric technicians, can perform some of the same diagnosis‑related and therapeutic tasks as psychiatrists. As such, hospitals, clinics, counties, and other organizations can utilize non‑psychiatrists in place of psychiatrists. However, other than psychiatric nurse practitioners (whose statewide employment numbers and salaries we were not able to obtain data to evaluate), psychiatrists are one of the only specialized mental health professionals whose scope of practice allows them to prescribe medication. Accordingly, psychiatrists play a critical role in the mental health services delivery continuum.

Regional Disparities Exist in the Mental Health Workforce

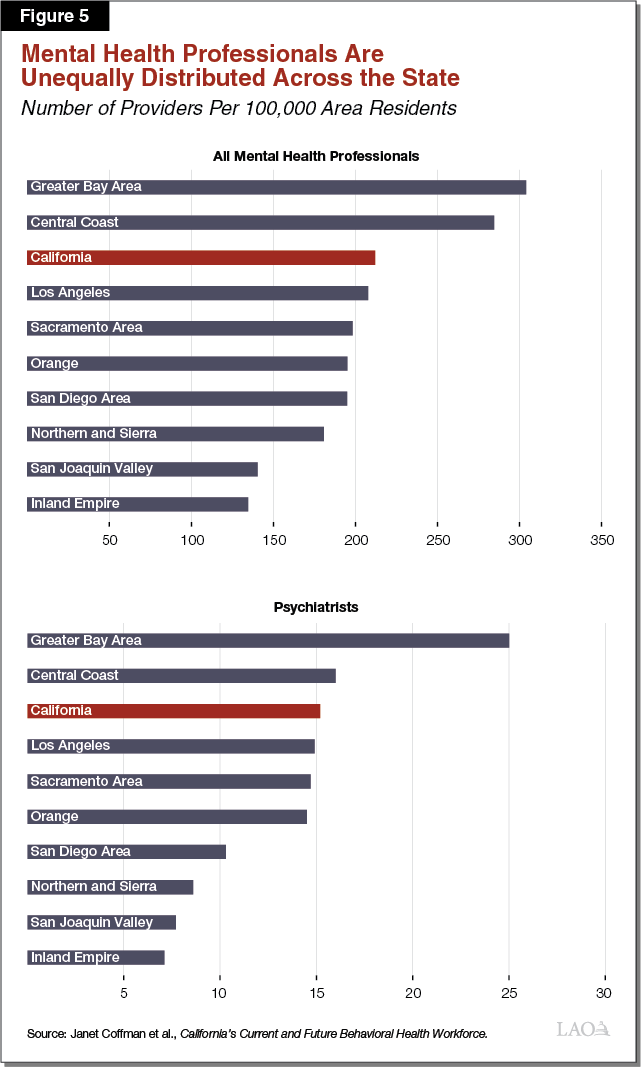

Regional Disparities Exist Among Mental Health Professionals Overall. Although we find mixed evidence of a statewide shortage of most mental health providers, we do find strong evidence that mental health professionals are unequally distributed across the state. Figure 5 shows certain regions have a high number of overall mental health professionals per 100,000 residents relative to the state average. For example, the Greater Bay Area has almost 50 percent more mental health professionals on a population basis than the statewide average. Other regions, such as Los Angeles and the Sacramento area, have comparable numbers of mental health professionals to the statewide average. Certain regions, however, have very low numbers of mental health professionals. The Inland Empire and San Joaquin Valley regions have about two‑thirds as many mental health professionals on a population basis as the statewide average, or about half as many mental health professionals on a population basis as the Greater Bay Area.

Distribution of Psychiatrists Throughout the State Is Particularly Disparate. Regional disparities of psychiatrists are greater than for mental health professionals overall. While the Greater Bay Area has 70 percent more psychiatrists than the statewide average, the Inland Empire and San Joaquin Valley have only about 50 percent of the statewide average on a population basis.

Unclear to What Extent Regional Disparities Reflect Differences in Demand for Mental Health Services. While there is strong evidence of regional disparities in terms of the supply of mental health professionals, it is unclear to what extent different regions have different demand or needs for mental health services. For example, the population of the Greater Bay Area may desire or need more mental health services than the population of San Diego. Accordingly, while the disparities in the supply of mental health professionals suggest some regions may be experiencing relatively more acute workforce shortages, additional analysis is needed to determine which regions are facing workforce challenges relative to the demand or need for mental health services.

Potential Impact of Funding Under the Governor’s Proposal Is Uncertain

Detail Lacking on How Governor’s Proposed Funding Would Be Allocated. Key details are missing on how the $50 million in one‑time General Fund proposed by the Governor would be allocated among existing mental health workforce programs. For example, the administration has not released a plan for how the funding would be allocated among scholarship and student loan repayment programs. In addition, it remains unclear how much funding would be allocated to the different state programs, each of which supports different sets of mental health professionals. For example, funding the Steven M. Thompson Program would support only psychiatrists while funding for the Mental Health Loan Assumption Program would support a broad range of professionals from clinical social workers to psychiatric nurse practitioners. The administration has shared that while OSHPD is evaluating various potential allocation strategies, it is not certain whether a detailed allocation proposal will be released at the time of the May Revision.

Governor’s Proposal Is Not Linked to a Long‑Term Mental Health Workforce Plan. As previously noted, earlier this year, OSHPD released a five‑year plan outlining the state’s vision and strategies for improving the state’s mental health workforce. Unlike previous plans, the five‑year plan did not specifically come with any attached funding. The $50 million proposed by the Governor, while in many ways consistent with both the current and previous five‑year mental health workforce plans, is not explicitly tied to the long‑term plan. According to the administration, the reason the plan and the funding are not more closely linked largely relates to the plan being released after the Governor’s budget. In addition, in our view, OSHPD’s plan does not contain sufficient detail to be used specifically as a funding plan. For example, the plan does not identify which regions and which mental health professions are experiencing the most acute mental health workforce needs. Rather, it lays out the general vision and goals of the administration as it pertains to mental health workforce.

Certain Existing State Programs Would Not Receive Funding Under the Governor’s Proposal. Not all existing mental health workforce programs would receive an augmentation under the Governor’s proposal. Primarily, the Governor’s proposal excludes existing programs, also administered by OSHPD, aimed at improving the state’s educational and training capacity for mental health professionals, such as those that support residency programs and clinical rotations.

Uncertainty Around Whether Existing State Programs and Strategies Have Been Effective. Overall, existing state mental health workforce programs may have had some positive impact in increasing the overall number of mental health professionals throughout the state. However, in the time available to perform this analysis, we were unable to perform a comprehensive evaluation of the impact that existing state mental health workforce programs have had on the overall supply and distribution of the state’s mental health workforce. It is our understanding that OSHPD, which oversees the mental health workforce issues and programs, has not released a comprehensive analysis of the programs’ impact. We did, however, review data on where recipients of mental health workforce stipends or student loan repayments worked after their service obligations had expired. As Figure 6 shows, this data showed little relationship between the regions of the state experiencing the greatest workforce challenges and the work location of award recipients following the completion of their service obligations.

Figure 6

Regions With the Smallest Mental Health Workforces

Have Not Seen the Largest Workforce Gains Under OSHPD’s Programs

|

Region |

Rank |

|

|

Region With the Smallest |

Region With the Most |

|

|

Inland Empire |

1 |

8 |

|

San Joaquin Valley |

2 |

5 |

|

Northern and Sierra |

3 |

1 |

|

San Diego Area |

4 |

6 |

|

Orange |

5 |

7 |

|

Sacramento Area |

6 |

4 |

|

Los Angeles |

7 |

3 |

|

Central Coast |

8 |

2 |

|

Greater Bay Area |

9 |

9 |

|

aNumbers reflect the ranking of regions in terms of the size of their mental health workforces, controlling for their population sizes. A ranking of 1 applies to the region with the smallest mental health workforce and a ranking of 9 applies to the region with the largest mental health workforce. bNumbers reflect the ranking of regions in terms of where beneficiaries of OSHPD mental health workforce, education, and training programs practice following the completion of their service obligations (controlling for the regions’ population sizes). A ranking of 1 applies to the region where the most awardees practice and a ranking of 9 applies to the region where the fewest awardees practice. OSHPD = Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development. |

||

Options for the Legislature

In this section, we provide several options for legislative consideration related to the Governor’s proposed $50 million in one‑time General Fund for mental health workforce: (1) take pause and study the underlying workforce issues further before appropriating funding, (2) adopt the Governor’s proposal with parameters designed to improve effectiveness, and (3) adopt the Governor’s proposed level of funding in 2019‑20 but allocate the funds adopting an alternative approach. We describe these options further below.

Take Pause to Identify Workforce Needs and Cost‑Effectiveness of Strategies

Identify Workforce Needs and Strategies Before Providing New State Funding. We have a number of outstanding questions related to (1) the magnitude, geography, and causes of any current or future mental health workforce shortages and (2) the effectiveness and associated trade‑offs of alternative policy solutions to addressing potential mental health workforce shortages. For example, an important, open question that our analysis was unable answer is what impact psychiatric health nurses and nurse practitioners have in mitigating potential mental health workforce shortages throughout the state. Given this and other outstanding questions and uncertainties, the Legislature could reject the Governor’s proposed funding and instead direct OSHPD or another qualified entity to study the state’s mental health workforce and recommend policy solutions to ameliorate any identified issues.

In Meantime, Counties Can Use Local MHSA Funding to Meet Local Workforce Needs. To the extent that counties wish to dedicate funding to mental health workforce programs, they could use a portion of their local MHSA funding to support local mental health workforce programs. We would note that until 2018‑19, most funding for mental health workforce comprised local MHSA funding redirected by the state to mental health workforce programs.

Approve Funding, but Establish Parameters for How Funding Is Allocated

Under the Governor’s proposal, the administration would have significant discretion to allocate the funding among existing state OSHPD programs and, in turn, for example, how much financial support different professions would receive. Provided the Legislature wishes to provide funding for existing mental health scholarship and student loan repayment programs administered by OSHPD, the Legislature could consider what parameters it would like to set for the appropriation. The following bullets provide parameters that the Legislature might consider including in budget‑related language:

- Prioritize Regions With Most Acute Shortages. As previously noted, our preliminary analysis has revealed that certain regions of the state—most notably the Inland Empire and the San Joaquin Valley—are likely experiencing the most acute shortages. Nevertheless, existing mental health workforce programs at OSHPD have not necessarily proven effective in increasing the workforce in these potentially high‑need regions. To ensure this funding goes to the areas with the highest need, the Legislature might consider directing OSHPD to prioritize regions with acute shortages in future funding rounds.

- Target Funding Toward Prescribing Professions. As discussed earlier, our preliminary analysis suggests potentially greater shortages among psychiatrists compared to non‑psychiatrist mental health professionals. As such, the Legislature might consider dedicating a significant portion of the $50 million in funding to programs targeting the recruitment of psychiatrists. The Legislature could also consider targeting the funding toward psychiatric nurse practitioners since, given their ability to prescribe medication, they can also provide a key specialized service delivered by psychiatrists.

- Extend Service Obligations. As previously noted, existing state mental health workforce programs generally require one‑to‑two year service obligations by awardees in designated shortage areas and other specified locations. Anecdotally, we have heard that awardees sometimes fulfill their service obligations and soon thereafter move to other practice locations and/or private practice to earn higher pay. To slow the rate of exit from the public mental health system as well as from high‑need regions of the state, the Legislature could consider extending awardees’ service obligation requirements beyond one‑to‑two years.

- Ensure Against Awarding Transfers From High‑Need Regions. Currently, awardees may have previously worked in one county facing a mental health workforce shortage and moved to work in another—and be eligible for an award. In such a case, the award would help to change which county is facing a workforce challenge but not relieve the state’s workforce issue as a whole. The Legislature might consider restricting eligibility for awards to individuals moving from out‑of‑state or from regions of the state facing less severe shortages.

Provide Funding, but Adopt Alternative Approach

Several Different Options Available to Legislature. The Legislature could also consider alternative approaches to that of the Governor, whose proposal would largely utilize scholarships and student loan repayment strategies to improve the mental health workforce. Potential alternative approaches include:

- Flexible Funding for Counties Facing Workforce Challenges. The Legislature could consider redirecting the Governor’s proposed $50 million to instead provide flexible funding to counties facing workforce challenges, which counties could use in accordance with local needs and conditions. For example, rather than or in addition to scholarships or student loan repayment, counties could choose to use such funding to support local education and training programs or to improve pay in areas that are facing acute recruiting challenges. Under this approach, the funding could be directed to counties in regions potentially facing the most acute mental health workforce issues.

- Expand the Mental Health Workforce Pipeline. While scholarship and student loan repayment programs may have some positive impact in growing the overall supply of mental health professionals, they potentially are most effective in determining the regional distribution and practice location of new professionals. Other approaches aimed at improving educational capacity may be relatively more effective in increasing the overall supply of mental professionals throughout the state. Given our analysis of existing workforce issues, we recommend the Legislature consider prioritizing any pipeline augmentations for psychiatrists and psychiatric nurse practitioner programs. Examples of potential interventions include funding for psychiatric residency programs and psychiatric nurse practitioner clinical rotation programs.