An Extraordinary Moment in California's Fiscal History

April 11, 2019

Gabriel Petek

Gabriel Petek

Legislative Analyst

California is at an extraordinary moment in its fiscal history. Even after taking into account the state’s various constitutional spending requirements, caseload growth, and inflation, we project the state to have more than $20 billion in discretionary resources—also referred to as a surplus—in the coming budget year. The Legislature deserves credit for working with the prior administration throughout the economic expansion to make the state’s currently very strong budget situation possible. Far from inevitable, this required the Legislature to be selective about making commitments to new spending while dedicating significant resources to one-time purposes and reserves. Talk of the state’s surplus, however, should distinguish between that which is expected in the upcoming budget year and its operating surplus, which is the annual amount of revenue in excess of spending in future years. While our $20 billion estimate for 2019-20 includes both one-time and ongoing resources, nothing approaching this amount is likely to be available on an ongoing basis. In our 2018 November fiscal outlook, for example, we projected that by 2022-23 the operating surplus would shrink to $3 billion. If the Governor’s programmatic proposals were enacted and his revenue assumptions hold, the Department of Finance forecasts that the operating surplus will dwindle to just $3 million over the same time horizon.

Crucially, at this point the surpluses discussed above are also only projections. As such, they are based on forecasts of revenues and expenditures, both of which are subject to considerable uncertainty. Our office as well as the administration will provide updated revenue forecasts in May. Currently, we think a modest downward revision to our November revenue forecast is more likely than an upward one. On the other hand, several highly anticipated initial public offerings could result in higher than previously anticipated personal income in the state which could give rise to an even larger surplus. Still, regardless of whether the updated forecast indicates a larger or smaller surplus, most of the surplus will be one time. Consequently, we generally believe the Governor’s emphasis on paying down debt, building reserves, and restricting most new spending to one-time outlays is appropriate.

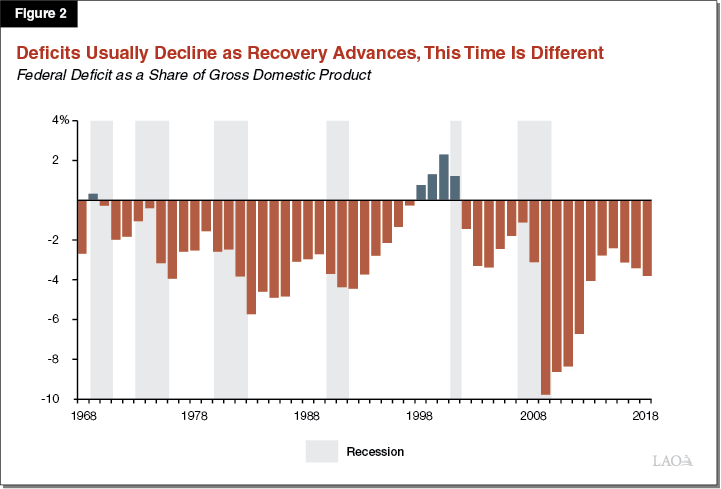

To the extent the Legislature agrees with the Governor’s approach to deploying the surplus, we offered some more cost-effective policy options for its consideration in our report, The 2019-20 Budget: Structuring the Budget: Reserves, Debt and Liabilities. Specifically, we suggest that instead of using money today to repay low-interest budgetary debts (loans to the General Fund from special funds), the Legislature could achieve a higher return on its investment by making larger supplemental contributions toward its unfunded pension liabilities, which accrue at higher interest rates. Another worthy consideration would be to put more funds into the state’s budget reserves rather than unwind certain expenditure deferrals. In our 2018 November fiscal outlook, we estimated that in order to cover the budget problem associated with a moderate recession without cutting programs or raising taxes, the state would require budget reserves of $25 billion. At $18 billion, total budget reserves under the Governor’s plan—while high from a historic standpoint—still fall short of this amount (see Figure 1). Yet, while higher reserves would reduce the need for program reductions in the next recession, doing so necessitates larger upfront deposits now, meaning there is less to spend on programs in the budget year. Although we acknowledge this is a difficult trade-off, we recommend the Legislature remain vigilant in its efforts to prepare for the next economic downturn.

Categorizing LAO Recommendations to Governor’s Programmatic Proposals

On the programmatic front, the Governor’s budget is ambitious and puts forward a range of new initiatives, as well as proposed expansions or changes to existing programs affecting early childhood education, health care, housing and homelessness, natural resources, the state tax code, and other areas. While our recommendations to the Legislature regarding the Governor’s various proposals are detailed in our more than two dozen reports that make up our 2019-20 budget series, we can generally categorize them in five main ways.

First, we believe the Legislature should consider adopting numerous of the Governor’s proposals, particularly where their objectives are clear and consistent with legislative priorities. Examples include the Governor’s proposal to fund deferred maintenance needs in the California State University and University of California systems. Likewise, we concur with the plan to fund and implement a 2018 legislative package designed to improve forest health and reduce wildfire risk and strengthen the state’s capacity to respond to wildfires.

A second category of proposals are those where the Governor’s proposals are broadly consistent with established legislative goals but would alter the timing and structure of plans the Legislature previously put in place. For these, we recommend the Legislature be clear-eyed about its policy objectives. For instance, the Governor’s proposal to increase California Work Opportunity and Responsibility to Kids (CalWORKs) grants is directionally aligned with the Legislature’s stated goals. However, the Governor proposes a single across-the-board grant increase to all recipients in 2019-20 whereas the Legislature’s plan provides varying grant increases—specifically, larger increases for the smallest families—phased in across three years. Notably, the Governor’s proposal would cost $60 million less in 2019-20 and, absent proposals from the administration to make additional grant increases in subsequent years, the Legislature’s plan would also cost significantly more in future years as well. In K-12 education, the Governor proposes capping the cost-of-living adjustment for the Local Control Funding Formula and repealing the Proposition 98 true-up account created last year. Ultimately, the Legislature may agree with the Governor’s approach in these areas, but it should first recognize that they represent changes from plans on which it embarked in 2018-19.

Third, we believe some of the Governor’s proposals could benefit from additional refinement. In these cases, we have tended to suggest that the Legislature request more information from the administration to better estimate their potential fiscal impact or policy implications. For example, we believe the Governor’s proposal to expand Medi-Cal coverage to income-eligible young adults regardless of immigration status may overstate the likely costs, especially in the first year. Conversely, the administration’s estimate of the cost of removing the work requirement for full-day State Preschool is likely understated. We believe reasonable cost estimates are of vital importance for the Legislature especially considering that some of the proposals, such as the examples cited above, represent new ongoing commitments.

A fourth group of the Governor’s proposals warrant serious consideration but are linked together with other proposals in ways that lack compelling justification. For example, the Governor proposes instituting a mandate that most Californians either maintain health insurance coverage or pay a penalty. Under the Governor’s plan, revenues from the penalty would be used to fund subsidies for those purchasing health insurance through Covered California. We noted (The 2019-20 Budget: The Governor’s Individual Health Insurance Market Affordability Proposals), however, that to the extent the individual mandate policy succeeds in its objective of increasing coverage, there will be less penalty revenue available for the subsidies. There are merits to both ideas, but we recommend the Legislature consider not limiting the financial support for the subsidies solely to the penalty revenues. In another example, the Governor proposes expanding the California Earned Income Tax Credit (CalEITC) program. The administration would pay for CalEITC with the additional revenue that would result from conforming the state tax code to various federal tax code provisions. Again, while there are good arguments in favor of both proposals, apart from both affecting the state tax code, we see no inherent policy reason for why they should be linked.

Finally, we recommend that the Legislature reject some of the Governor’s proposals. A notable example is the Governor’s $700 million in grants to local governments intended to incentivize the production of housing units and facilities to ameliorate homelessness. Evidence suggests the efficacy of such incentives is questionable and may wind up delivering a windfall to governments already planning to undertake such initiatives. Therefore, while we commend the Governor for signaling his intent to confront the problem of California’s severe shortage of affordable housing, we offered some alternative options. We also recommend rejecting the Governor’s proposed $750 million in grants to school districts for the conversion of part-day kindergarten programs to full-day programs. A similarly structured, though smaller, $100 million grant program from 2018-19 is instructive. Among the districts that applied for grants in that program, we estimate 76 percent already offered full-day programs. It is also unclear whether the grants are necessary to achieve the Legislature’s goals. Existing funding sources enabled districts to raise the share of students in full-day programs to 70 percent, from 43 percent, over the last ten years. Given this demonstrable progress toward the goal of expanding full-day kindergarten, we believe the Legislature can find higher impact uses for these resources. We also recommend that the Legislature “reject” the Governor’s lack of a proposal in the budget to extend the package of tax changes on managed care organizations (MCOs) currently scheduled to lapse at the end of the fiscal year. Because the MCO tax package leverages federal Medicaid matching funds, the Governor’s nonproposal in this area has the effect of leaving money on the table. Therefore, we think the Legislature should strongly consider extending the MCO tax package even in the absence of a proposal to do so from the Governor.

Assessing the Net Fiscal Impact

In total, the Governor’s budget proposal would increase General Fund program spending by $7.8 billion, of which $5.1 billion would be for one-time purposes and $2.7 billion for new ongoing commitments (growing to $3.5 billion by 2022-23). On balance, our recommendations would trim this back by $1.7 billion (one time), while extending the MCO tax package would provide $1.5 billion in ongoing benefit to the General Fund. With $3.2 billion in additional budget capacity, the Legislature could put more resources to its spending priorities (or other uses) and add more materially to its budget reserves.

Consider the Macroeconomic Backdrop

While there is little to suggest that a recession is imminent, most indicators point to slowing economic growth. Lower gross domestic product (GDP) growth rates imply less distance to outright contraction and raise the risk that unforeseen events could more easily tip the economy into a downturn. California’s practice in recent years of increasing its budget reserves is prudent and akin to taking out an insurance policy against the inevitable revenue shortfalls that will accompany the next recession. However, our recession scenario analyses suggest that the state’s budget reserves—despite their historically large balances—are insufficient to cover all revenue losses.

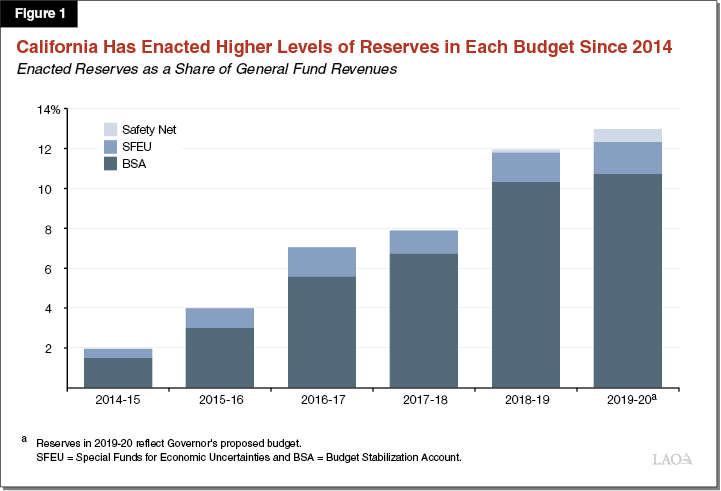

One reason to consider staying the course on adding to reserves is the degree to which the federal government’s fiscal position has deteriorated over the past one-to-two years (see Figure 2). Measured against U.S. GDP, federal deficits are approaching unprecedented levels for a nonrecessionary peacetime setting. In addition, despite having raised the Federal Funds Rate seven times in 2017 and 2018, the Federal Reserve’s policy rate remains low (2.25 percent to 2.5 percent). Therefore, in the event of recession, federal fiscal and monetary policy officials may find they have less countercyclical firepower at their disposal than they did in prior recessions. Simply put, unlike what happened following the onset of the last two economic contractions, the Legislature cannot assume extraordinary federal aid will be forthcoming. This means that the brunt of the next downturn is likely to fall more squarely on the state than in those prior episodes. By building even more reserves than it already has, the Legislature could mitigate the need for program cuts, tax increases, or spending deferrals when the next recession strikes.