LAO Contact

See These Related

2019-20 Budget Reports

February 20, 2019

The 2019-20 Budget

What Can Be Done to Improve Local Planning for Housing?

- Introduction

- Planning for New Housing Often Falls Short

- Governor Proposes Changes to State Oversight of Local Housing Decisions

- Proposed Short‑Term Building Goals Questionable

- Rethinking Long‑Term Planning Worthwhile

Summary

California’s cities and counties make most decisions about when, where, and to what extent housing will be built. The state requires cities and counties to carry out certain planning exercises in an attempt to ensure they accommodate needed home building. For a variety of reasons, this state oversight generally has been ineffective. For this reason—and others—too little housing has been built in many California communities, leading to a housing shortage and rising housing costs.

The Governor proposes changing state oversight of local housing decisions and proposes offering rewards to cities and counties to encourage them to plan for and approve housing. Specifically, the Governor proposes (1) establishing new short‑term housing goals for local communities and providing them funding to help them plan to meet these goals, (2) offering additional funding to communities that make progress toward meeting the short‑term goals, (3) revamping the state’s existing process for establishing long‑term housing goals for communities, and (4) linking receipt of funds for local streets and roads to communities’ progress toward meeting long‑term housing goals.

The Governor’s plan to establish state‑defined housing goals and have local governments carry out planning to meet these goals is not a new strategy. The state has carried out such a strategy for years with limited results. In addition, past state attempts to offer rewards to encourage communities to approve housing provide little assurance that such an approach will result in significantly more home building. Accordingly, we recommend the Legislature reject the Governor’s proposal for short‑term housing production goals and grants to locals.

Instead of focusing on the short term, the state may be better off focusing its scarce resources and efforts on boosting home building over the long term. Along those lines, the Governor’s proposal to revamp long‑term planning for housing is worthwhile. The Legislature has taken important steps in this areas in recent years. That being said, opportunities to improve the current system remain. We offer a package of changes to long‑term planning that we think should be considered: (1) better incorporating measures of housing demand into the calculation of housing goals, (2) lengthening the planning horizon, (3) further enhancing state oversight and enforcement, (4) preempting local land use rules if communities do not faithfully participate in long‑term planning, and (5) increasing financial incentives for locals to approve housing. We also discuss the pros and cons of linking transportation funding to local approvals of housing and offer one approach for Legislative consideration.

Introduction

As part of the 2019‑20 Governor’s Budget, the administration proposes changing state oversight of local housing decisions and proposes offering rewards to cities and counties to encourage them to plan for and approve housing. To help the Legislature in its consideration of the Governor’s proposals, this report: (1) explains the existing process through which local communities plan for housing, as well as its limitations and shortfalls; (2) describes the Governor’s proposal; (3) provides recommendations on the parts of the proposal aimed at increasing home building in the short term; and (4) offers a package of changes to improve the state’s existing long‑term planning process for housing.

Planning for New Housing Often Falls Short

California’s cities and counties make most decisions about when, where, and to what extent housing will be built. The state requires cities and counties to carry out certain planning exercises in an attempt to ensure they accommodate needed home building. For a variety of reasons, this state oversight has largely failed. In part because of this, too little housing has been built in many California communities, leading to a housing shortage. This housing shortage has, in turn, led to rising housing costs and declining affordability for many Californians.

Basics of Local Government Planning

Housing Element Outlines How a Community Will Meet Its Housing Needs. Every city and county in California is required to develop a general plan that outlines the community’s vision of future development. One component of the general plan is the housing element, which outlines a long‑term plan for meeting the community’s existing and projected housing needs. The housing element demonstrates how the community plans to accommodate its “fair share” of its region’s housing needs. To do so, each community establishes an inventory of sites designated for new housing that is sufficient to accommodate its fair share. Communities also identify regulatory barriers to housing development and propose strategies to address those barriers. State law generally requires cities and counties to update their housing elements every eight years.

Regional Housing Needs Allocation Process Defines Each Community’s Fair Share of Housing. Each community’s fair share of housing is determined through a process known as Regional Housing Needs Allocation (RHNA). The RHNA process has three main steps:

- State Develops Regional Housing Needs Estimates. To begin the process, the state department of Housing and Community Development (HCD) estimates the amount of new housing each of the state’s regions would need to build to accommodate the number of households projected to live there in the future. Household projections are based on an analysis of demographic trends and population growth estimates from the state Department of Finance (DOF). Each region’s housing needs are grouped into four categories based on the anticipated income levels of future households: very‑low, low, moderate, and above‑moderate income.

- Regional Councils of Government Allocate Housing Within Each Region. Next, regional councils of governments (regional planning organizations governed by elected officials from the region’s cities and counties) allocate a share of their region’s projected housing need to each city and county. Cities and counties receive separate housing targets for very‑low, low, moderate, and above‑moderate income households. Each council of government develops its own methodology for allocating housing amongst its cities and counties. State law, however, lays out a variety of requirements and standards these methodologies must meet.

- Cities and Counties Incorporate Their Allocations Into Their Housing Elements. Finally, cities and counties incorporate their share of the regional allocation into their housing element. Communities typically do so by demonstrating how they plan to accommodate their projected housing needs in each income category.

Zoning Key to Meeting Housing Needs. To carry out the policy goals in their general plans and housing elements, cities and counties enact zoning ordinances to define each property’s allowable use and form. Use dictates the category of development that is permitted on the property—such as single‑family residential, multifamily residential, or commercial. Form dictates building height and bulk, the share of land covered by buildings, and the distance of buildings from neighboring properties and roads. Rules about form effectively determine how many housing units can be built on a particular site. A site with one‑ or two‑story height limits and large setbacks from surrounding properties typically can accommodate only single‑family homes. Conversely, a site with height limits over one hundred feet and limited setbacks can accommodate higher‑density housing such as multistory apartments. By dictating how many sites housing can be built on and at what densities, zoning controls how much housing a community can accommodate. Zoning, therefore, must allow for new housing on a sufficient number of sites and at sufficient densities if a city or county is to meet its community’s housing needs.

Limitations of the Housing Element Process

Communities Often Reluctant to Plan for Housing. The process described above through which the state dictates housing goals that local governments incorporate into their housing elements and zoning rules has many shortcomings. Perhaps the most significant is that residents of many communities are reluctant to accommodate housing growth, fearing that such growth could bring about changes to the nature of their community. Reflecting this reluctance, many communities have not carried out the housing element process in a way that truly facilitates home building. Setting aside this concern, several other factors would limit how effective the housing element process could be even if communities were not reluctant to carry it out. We highlight some of these factors below.

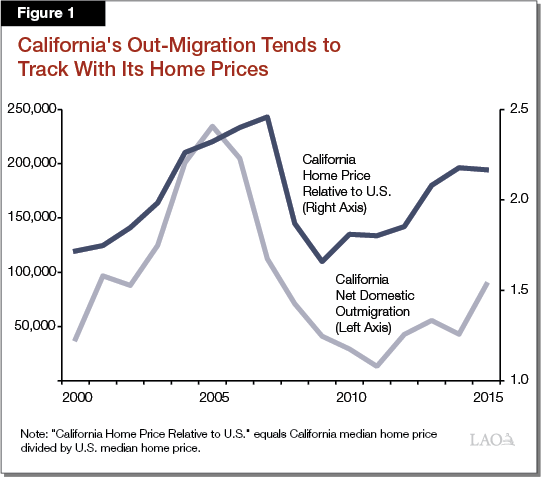

Demographic Projections Underestimate Housing Demand. Projections of household growth are a poor measure of future housing demand. These projections are based, in part, on extrapolations from past trends in population growth, migration, and household formation. Past demographic trends fail to capture the full extent of demand for housing. Many communities in California have significant housing shortages. These shortages mean that households compete for limited housing, bidding up home prices and rents. Households unwilling or unable to pay these high costs are forced to live somewhere else. Several studies have documented that movement into an area is lower when housing costs are higher. Consistent with this research, we see that California’s net out‑migration (out‑migration minus in‑migration) to other states is higher when housing costs are rising, as shown in Figure 1. Households forced to live somewhere else do not show up in a community’s past demographic trends and therefore are not reflected in RHNA calculations. They nonetheless contribute to the unmet demand for housing and resulting high housing costs. Ignoring these households when estimating housing demand is akin to assuming the number of people who wanted to go to a popular sold out concert is equal to the number of people who actually attended. Clearly, more people would have attended if the venue had been bigger and more tickets had been available. Similarly, more people would live in California if more housing were built for them.

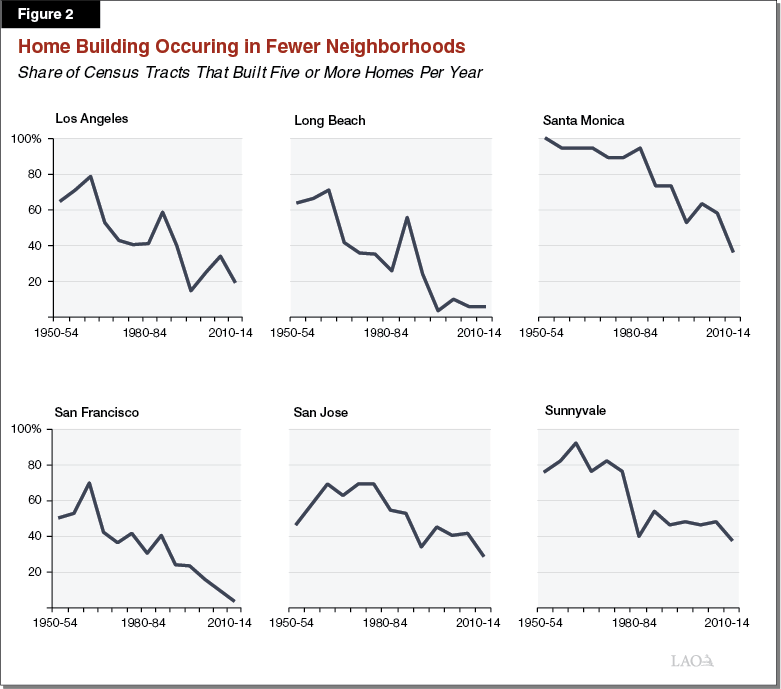

Time Period Covered by Housing Goals Is Too Short. Decisions that communities make today about housing will shape those communities for decades. Once built, most housing remains in place for decades. Further, once a certain type of housing—especially single‑family housing—becomes the norm in a neighborhood, it becomes very difficult to add new, different types of housing to the neighborhood. Despite this, the housing element process only requires cities to consider how their actions today will accommodate housing needs over the next eight years. This can be problematic. The history of housing development in California over the last several decades shows why. For decades, many cities allowed much of their land to be built up as relatively low‑density housing, primarily single‑family homes. Today, given resistance to add more dense housing to single‑family neighborhoods, many communities have very limited space on which to accommodate new housing. The share of neighborhoods experiencing any home building has dropped significantly over time in many cities, as shown in Figure 2. This concentration of building in a minority of neighborhoods limits opportunities for builders. It also contributes to tension in communities that can contribute to resistance to additional home building. Residents of the neighborhoods where housing is being built may push back wondering why they are being asked to accommodate growth while other residents are not.

Identifying Ideal Sites for Housing Is Difficult. The task of anticipating which particular sites will be profitable for developers to build on in the future is difficult. This is because developers’ decisions about which sites to build on and when are based on a multitude of considerations and require detailed analyses of economic, engineering, and political information. In addition, decisions of landowners can significantly influence which sites are developed. In some cases, planners and builders may agree that certain sites would be ideal for new housing but landowners may be unwilling to sell their land to home builders. As we discussed in our 2016 report, Common Claims About Proposition 13, this may be exacerbated by California’s property tax system which can encourage landowners to hold onto vacant or underutilized properties longer than they otherwise would.

There Are Practical Limits to State Oversight. Although HCD reviews each community’s housing element and inventory of sites, HCD lacks the capacity to thoroughly vet the thousands of potential housing sites identified in communities’ housing elements. Over the course of a few years, HCD staff are tasked with reviewing the housing elements of the state’s 58 counties and 482 cities. Many housing elements are lengthy and complex documents. Some housing site inventories contain thousands of properties—for example, the city of Los Angeles’ site inventory contains over 20,000 sites. To carry out this task, HCD historically has received funding in the millions of dollars per year. In contrast, local planning departments receive over $1 billion per year in funding from local sources. In addition to having far greater resources, local planning departments also have more insight into their local communities.

Affordable Housing Funding Insufficient for Locals to Meet Housing Goals. The housing element process aims to facilitate home build for households of all income levels. A key segment of this intended housing production is affordable housing for low‑income households. The most recent RHNA projects a need for 58,000 new low‑income affordable homes per year across the state. To build these affordable homes, builders typically need some type of subsidy because the rents and prices low‑income households are able to pay do not cover builders’ construction costs. Most often, this subsidy is provided through a combination of financial support from federal, state, and local governments. Currently, the amount of public funds available for affordable housing falls well short of what would be needed to finance the cost of 58,000 affordable homes per year. Just to cover the state’s typical share of affordable housing subsidies (about one‑fourth of total costs) likely would require an annual, ongoing funding stream of $4 billion to $6 billion. Despite recent increases, state funding for affordable housing currently totals about $2 billion per year. This mismatch of funding makes it unrealistic to expect local communities to meet their housing goals for lower‑income households.

Housing Element Process Falls Short of Its Goal

Evidence of Housing Element Shortfalls. In our 2017 report, Do Communities Adequately Plan for Housing?, we laid out evidence that the housing element process falls well short of its objective of ensuring that communities accommodate needed home building. Communities’ zoning rules often are out of sync with the types of projects developers desire to build and households desire to live in. Our review found that most housing built in recent years was on sites that were not identified in a communities’ housing element. Further, in several cities that we examined, most projects required a significant increase in the density allowed by local zoning rules. The failure of housing elements to identify and adequately zone feasible sites for housing creates a drag on home building. This has significantly contributed California’s major shortage of home building. As we discussed in California’s High Housing Costs: Causes and Consequences, California has for decades built only about half as much housing each year as needed to meet demand.

Recent Legislation Likely Will Improve Outcomes. Over the last two years, the Legislature has enacted several bills aimed at boosting home building through a variety of avenues. Some of this legislation included changes to procedures, standards of review, and enforcement for housing elements. Other legislation reformed the process through which housing needs are distributed to communities within a region. These changes likely will lead to improved outcomes. Nonetheless, opportunities remain to build on recent legislative actions to further improve long‑term planning for housing.

Governor Proposes Changes to State Oversight of Local Housing Decisions

In his 2019‑20 budget, the Governor proposed changes to state oversight of local housing decisions and proposed to offer rewards to cities and counties to encourage them to plan for and approve housing. As of now, these proposals are conceptual. In many cases, the administration has signaled its intent to engage stakeholders in the development of the final details. Below we describe the Governor’s proposal to date.

Develop Short‑Term Housing Goals for Cities and Counties. The HCD would develop new “short‑term” housing production goals for cities and counties. (The administration has not yet defined what time period these short‑term goals would cover.) Locals would then be expected to conduct planning and make necessary land use changes to achieve their new short‑term goals. To assist locals in doing so, the Governor’s budget proposes allocating $250 million General Fund to cities and counties that could be used for planning activities.

Offer Grants to Local Governments to Encourage Them to Meet Short‑Term Goals. The Governor’s budget also proposes making $500 million General Fund available for cities and counties to reward them for reaching “milestones” in their efforts to meet their short‑term goals. As a community reaches its milestone, it would receive a portion of the $500 million which it could use for any purpose.

Rethink Long‑Term Housing Goals. The administration also signals its intent to revamp the current housing element and RHNA process. As part of this effort, the administration would engage with stakeholders to develop a plan for linking funding for local streets and roads to communities’ progress toward their RHNA goals.

Proposed Short‑Term Building Goals Questionable

The Governor’s plan to establish state‑defined housing goals and have local governments carry out planning to meet these goals is not a new strategy. The state has carried out such a strategy for years via the housing element and RHNA processes with only limited success. The Governor’s plan hopes to encourage locals to participate by offering one‑time financial rewards. Prior state attempts to offer such rewards provide little assurance that doing so will significantly increase communities’ willingness to plan for and approve housing. All in all, it is unclear how the Governor’s plan differs significantly from past strategies that generally have fallen short of their goals.

We recommend the Legislature reject the Governor’s proposal for short‑term housing production goals and $500 million in incentive funds for cities and counties. Instead of focusing on the short term, the state may be better off focusing on opportunities to further improve long‑term planning and considering other policy changes aimed at boosting home building over the long term. California’s current housing situation is the culmination of decades of decisions to under‑prioritize home building. It will similarly take many years or decades to truly address. Should the Legislature reject the Governor’s plan to establish short‑term housing goals, there would be no need to provide $250 million to cities and counties for them to plan to meet these short‑term goals. That being said, if the Legislature pursues changes to the state’s long‑term planning policies, it could consider providing this funding to cities and counties to help implement those changes.

Benefit of Offering Rewards to Locals Is Unclear

Prior Programs to Reward Home Building. The Governor’s plan hopes to encourage locals to meet their housing goals by offering financial rewards. The state has tried this strategy before. A few state programs have offered cities and counties flexible funding that they could use for infrastructure projects as a reward for permitting housing. These programs include:

- Housing‑Related Parks Program. This program awarded cities and counties a total of $200 million over multiple years to reward them for permitting low‑income affordable housing during the years 2010 through 2016. Awarded funds could be used for creation or improvement of parks or recreation facilities.

- Workforce Housing Reward Program. This program awarded cities and counties a total of $75 million over multiple years to reward them for permitting low‑income affordable housing during the years 2004 through 2006. Awarded funds could be used for a variety of infrastructure or facilities projects.

- Jobs Housing Balance Incentive Grant Program. This program awarded a total of $25 million to cities and counties that increased the number of housing permits they issued (for all income levels) by 12 percent or more in 2001. Awarded funds could be used for a variety of infrastructure or facilities projects.

Rigorous Evaluation of These Programs Is Difficult. The design of these past programs makes rigorous evaluation of their outcomes difficult if not impossible. Ideally, to evaluate these programs’ effects we would compare the outcomes of eligible cities and counties to similar cities and counties that were not eligible. All cities and counties, however, were potentially eligible for these programs. This prevents us from using such an approach. We can turn to other evidence, however, that is less rigorous but still somewhat helpful. This evidence, which we discuss below, suggests the impact of these programs was limited at best.

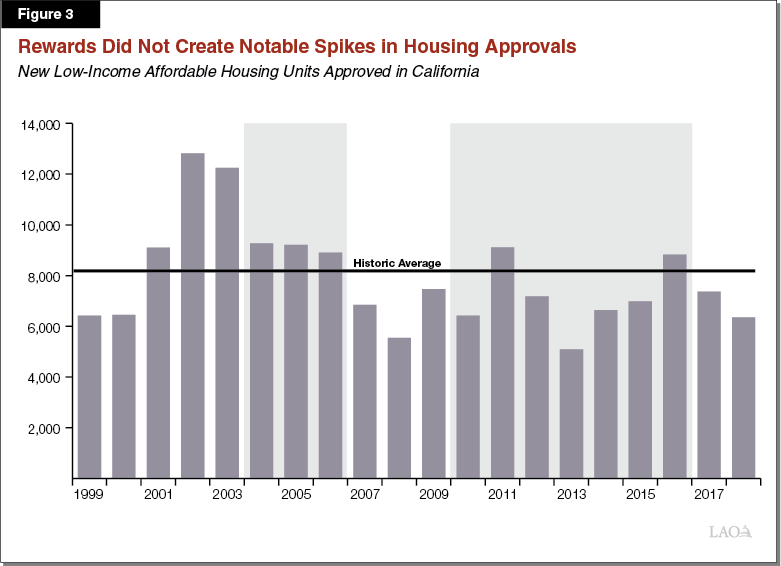

No Notable Spike in Affordable Housing Construction. If the Housing‑Related Parks Program and Workforce Housing Reward Program had significantly affected permitting of affordable housing, we would expect to see notable spikes in permitting in the years covered by these programs. This did not occur. This can be seen in Figure 3 which shows how many new affordable housing units were approved each year under the Low‑Income Housing Tax Credit Program (a key affordable housing finance source used as a component of most affordable developments) over the past two decades. While this observation does not allow us to conclude these programs had no effect on permitting, it suggests that the effect—if any—was small.

No Outsized Response From Cities Eligible for Larger Rewards. The Housing‑Related Parks Program offered larger rewards for housing permitted in “disadvantaged” neighborhoods. If the financial reward of this program influenced cities’ permitting decisions, we would expect to find that cities with more disadvantaged neighborhoods—and therefore more likely to receive the larger reward—were more responsive to the program. We do not find this to be the case. Although affordable housing approvals between 2010 and 2016 (the period covered by the Housing‑Related Parks Program) were down across the state relative to the preceding seven years, cities with the most disadvantaged neighborhoods (top fifth of all cities) saw a bigger decline—23 percent decrease compared to a 14 percent decrease in other cities.

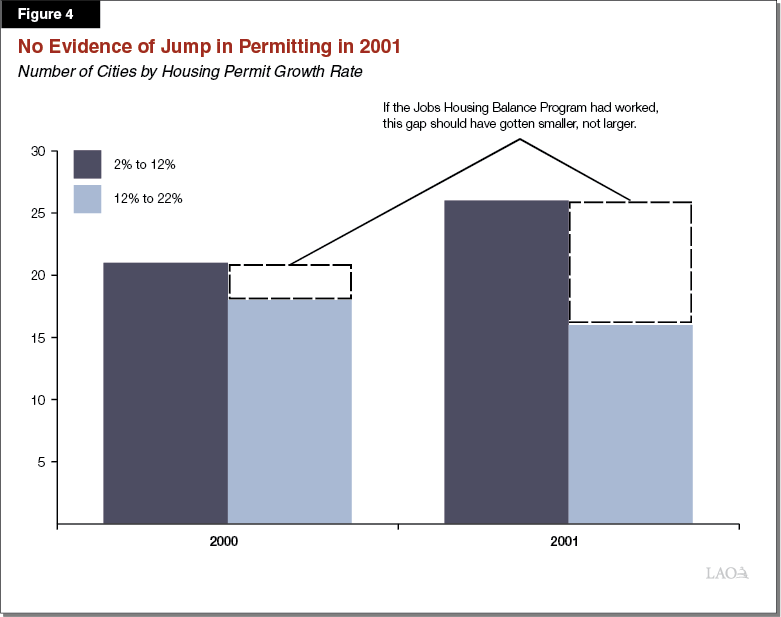

No Increase in Number of Cities With High Housing Permit Growth. If the Jobs Housing Balance Incentive Grant Program had encouraged cities to increase permitting in 2001 by at least 12 percent, we would expect to see more cities with permit growth above 12 percent in 2001 compared to past years. Similarly, we would expect to see fewer cities with permit growth below 12 percent. This is because some cities with past permit growth slower than 12 percent would increase their permit growth to above 12 percent. Comparing cities’ permit growth in 2000 to growth in 2001 we find no evidence of an increase in permitting. As Figure 4 shows, there were fewer cities with permit growth just above 12 percent in 2001 than in 2000. On the flip side, there were more cities with permit growth just below 12 percent in 2001 than in 2000. This evidence suggests that the program did not encourage cities to increase permitting. Instead, the program appears to have provided a windfall benefit to communities that would have increased permitting in 2001 even in the absence of the program.

Limited Compliance With Housing Element Procedures. In addition to attempting to increase permitting, past programs attempted to encourage cities and counties to comply with a relatively minor procedural requirement of the housing element process—submitting annual progress reports to HCD—by making compliance a condition of eligibility for funding. Many cities did not respond to this incentive. As of 2016, only about half of jurisdictions were in compliance. (More recently, compliance has increased significantly in response to legislation passed in 2017 which heightened the consequences for not reporting.)

$500 Million Is More Than Past Programs, Still Very Small Relative to Size of City and County Budgets. One possible reason for the apparent ineffectiveness of these past programs is that the funding made available to cities and counties was relatively minor compared to the size of city and county budgets. In 2016‑17, cities ($27 billion) and counties ($49 billion) received $76 billion in general purpose revenue. The $500 million proposed by the Governor is more funding than past programs. The Governor also proposes to allow more local flexibility in spending the funds. This might make his proposal more successful. On the other hand, $500 million is still relatively small compared to the size of city and county budgets. Under the Governor’s proposal, most local governments would receive a reward that would increase their general purpose revenues by a few percent for a single year. This may not be a sufficient financial incentive for local elected officials to take what would, in many cases, be very unpopular actions to boost housing.

Offering Rewards in Hopes of Increasing Home Building Would Be Risky. Based on the above evidence we cannot rule out that these prior programs had a small positive effect on home building, but we see no evidence that these programs significantly improved communities’ progress toward their RHNA goals. Given this, offering rewards to cities and counties in hopes of boosting housing production seems like a risky bet. If the Legislature were to allocate funding for rewards, it cannot be sure what effect, if any, such a program would have on home building. There are alternative uses of these funds which would yield more certain benefits. For example, providing $500 million in subsidies to affordable housing builders would almost certainly yield around 5,000 new units of housing. Given the uncertain benefits, we recommend the Legislature not appropriate $500 million for one‑time rewards for locals.

If Moving Forward With Governor’s Proposal, Structure Program to Yield Useful Information. Should the Legislature wish to move forward with a plan to offer rewards to locals, we suggest structuring the program in a way that would facilitate more rigorous evaluation of its outcomes. Specifically, we would suggest:

- Establish a Comparison Group. Within each region of the state randomly select half of jurisdictions to participate in the program. The other half would serve as a comparison group which could be used to judge the outcomes of the participating jurisdictions. While a random selection of participants would mean that not all communities would be able to benefit from the program, such a program structure would provide important information to the Legislature about the efficacy of offering financial rewards to local communities. This information could be used to improve future programs that could offer rewards to all communities.

- Base Rewards on Prospective Increases in Home Building. The program structure should be finalized and participants selected and notified in 2019‑20. Rewards should then be based on local community actions in 2020‑21 or beyond. This would give communities time to adjust their behavior in response to the financial incentives.

Rethinking Long‑Term Planning Worthwhile

While the Governor’s proposal to boost home building goals in the short term may be questionable, his plan to revamp state policies on long‑term planning is worthwhile. While the Legislature has taken important steps in this area in recent years, opportunities remain for further improvement. In this section, we offer some ideas for improvements in long‑term planning. We then offer comments on the Governor’s proposal to link transportation funding to communities’ progress toward longer‑term housing goals.

Options to Improve Long‑Term Planning

Incorporate Measures of Housing Demand Into Calculation of Housing Goals. Current demographic‑based RHNA projections could be adjusted to account for signs of unmet housing demand, such as high rents. Our modeling of California’s housing markets in California’s High Housing Costs: Causes and Consequences suggested that there is roughly a one‑to‑one relationship between the long‑term rate of growth in a community’s housing stock and the long‑term rate of growth in its home prices and rents. Consistent with this, one option could be to adjust upward RHNA goals for areas with high rent growth. This adjustment could be applied at the first step in the RHNA process, when the state determines housing goals for each region. Specifically, the basic steps of a new process could be:

- (1) Determine Household Growth Projections. The HCD would determine projections of total households for each county based on DOF demographic projections.

- (2) Adjust Household Growth Projections. The household projections from step 1 would then be adjusted upward for counties where past rent growth exceeded the national norm. This adjustment would be proportionate to the extent to which a county’s growth in median rent over the last 20 years exceeded the U.S. average. For example, if a county is projected to have 1 million households and its rents grew 20 percent faster than the U.S., its adjusted household number would be 1.2 million.

- (3) Compare Household Projections to Total Housing. The adjusted household projections from step 2 would then be compared to total existing housing units within the county. The difference between the two would be the county’s housing need.

- (4) Sum County Estimates by Region. The county housing need estimates would then be totaled by region and provided to the regional governments for allocation to cities and counties within each region pursuant to newly‑reformed state laws.

Lengthen Planning Period. Lengthening the planning period covered by the housing element process could help to avoid communities becoming locked into land use patterns that could prevent them from accommodating growth in the future. A longer planning window also could encourage a community to think about how its decisions on things like infrastructure or climate change adaptation affect its ability to accommodate housing growth well into the future. One option could be to have HCD determine projected housing needs for 20 years and have local communities develop plans and land use rules to meet those needs. Because 20 year projections would be imprecise, these projections and housing element plans would need to be updated frequently—such as every five years—based on the latest demographic and economic information. Under the current process, projections and plans are updated only once at the beginning of the eight year planning period.

Conduct Random Audits of Housing Sites Inventories. Determining whether a site is feasible for a certain type of housing requires a detailed analysis of relevant economic, engineering, and political information. It is not practical for HCD to conduct such in‑depth reviews of the thousands of housing sites slated for development in communities’ housing elements. As a compromise, HCD could conduct in‑depth reviews of a subset of randomly selected housing element sites. Other state agencies use random selection in enforcement activities—for example, state tax administration agencies randomly select business records for review in conducting an audit. Should these random in‑depth reviews determine that a community did not do its due diligence, HCD could declare the community’s housing element out of compliance. The potential of an audit with negative findings, coupled with heightened consequences for communities being out of compliance as discussed below, could encourage communities to more faithfully participate in the housing element process.

Preempt Local Zoning Laws if Locals Do Not Faithfully Carry Out Long‑Term Planning. Cities and counties currently have the ultimate authority to make decisions about zoning and other land use rules. One alternative to this approach is for the state to dictate zoning rules. For example, last year the Legislature considered a bill that would have exempted proposals for new housing near transit stops from a variety of local zoning rules, such as rules that limit building heights to fewer than five stories or create minimum parking requirements. Proposals for the state to dictate zoning rules historically have met fervent opposition. The assignment of land use authority to cities and counties reflects a deeply held desire of the state’s residents to control the environment of their communities. Many question how the state could make appropriate decisions about their community without intimate knowledge or their community. Such concerns have prevented the state from taking a more active role in zoning decisions. At the same time, restrictive local zoning rules are one of the primary causes of the state’s current housing shortage, arguing for more state involvement. A possible compromise could be for the state to preempt local zoning rules only in cases where communities are not faithfully participating in the housing element process. For example, the state could develop default zoning rules that would apply in any community that HCD has determined is out of compliance with housing element law.

Alter Allocation of Local Taxes. As we discussed in California’s High Housing Costs: Causes and Consequences, local communities face fiscal incentives that are adverse to new housing. Few city and county revenue sources grow proportionately with increases in population. This can lead to fears that accommodating new housing—and therefore new people—will increase demands for public services faster than the funding available to pay for those services. This can, in turn, amplify communities’ anxieties about allowing new housing. One approach the Legislature could consider to alleviate this concern is to alter the allocation of local government tax revenues—particularly property or sales taxes—so that these allocations better reflect population growth. One option could be to allocate some or all of future growth in local property and/or sales taxes within each county to jurisdictions based on their population growth. While such changes could be worthwhile, we caution that they would face several hurdles. The State Constitution significantly limits the Legislature’s ability to alter the allocation of local revenues. Also, past attempts to change the allocation of local property taxes or sales taxes have faced stiff resistance from local agencies concerned that such changes would create winners and losers and disrupt the financial health of some communities.

Should Funds Be Tied to Meeting RHNA Targets?

In 2017, the Legislature enacted Chapter 5 (SB 1, Beall) which increased state revenue for transportation by about $5 billion per year. Under this funding package, cities and counties receive around $1.5 billion annually to fund maintenance of local streets and roads. The Governor’s proposal to link these distributions for local streets and roads to communities’ progress toward meeting their RHNA targets would create a significant, ongoing financial incentive for communities to plan for and approve housing. These distributions are the largest funding stream to cities over which the state has control and, therefore, present the clearest opportunity for the state to shift the financial incentives faced by local communities. Such an approach, however, presents some problems.

Some Factors Are Outside of Local Communities’ Control . . . While cities have significant control over when, where, and how much housing is built, many other factors also are important. The health of the state’s economy, lending conditions, and decisions by builders and landowners are all beyond the control of local governments but significantly affect home building. While it is reasonable for the state to ask cities and counties to do all they can do to plan for and facilitate a particular amount of home building, holding them entirely accountable for outcomes that they do not completely control may be unreasonable.

. . . So Consider Gauging Performance Relative to Other Communities. A possible compromise could be to link funding to a community’s home building performance relative to other communities. Gauging a community’s performance relative to its peers instead of an absolute target would account for the impact of changes in economic and other factors that influence home building across all communities. One potential approach could be the following:

- (1) Reform RHNA Goals. Make the improvements to communities’ RHNA goals we discussed above.

- (2) Determine Each Community’s Progress Toward Their RHNA Targets. Each year, calculate each community’s progress toward their RHNA goals in each income category. Progress could be as measured by the percent of the RHNA goal that has actually been permitted. Then, average the percentages across all income categories to obtain a single progress rate.

- (3) Compare RHNA Progress to Statewide Average. Average the progress rates across all cities and counties. Then, calculate each community’s relative performance by dividing its progress rate by the statewide average. The larger the number, the better a community’s performance.

- (4) Adjust Local Streets and Roads Funding Allocations. Multiply each community’s allocation of streets and roads funding under existing law by the community’s relative performance calculated in step 3. For example, if the calculation in step 3 says a city has achieved twice as much progress as the state average its streets and roads funding would be doubled. Finally, multiply each community’s newly‑adjusted allocation by the ratio of total streets and roads funding under existing law to the sum of the newly adjusted allocations for all communities. This would ensure that the new allocations would fit within the existing pot of funding.

Transportation Funding Goals Could Be Undermined. A second concern with tying transportation funding to housing production is that doing so could undermine the state’s transportation goals. The funding allocation that best facilitates the maintenance of local streets and roads will almost certainly be different than the allocation that would result if funds were tied to housing production. There is no easy way of resolving this tension.