LAO Contact

- Local Control Funding Formula Kindergarten

- Career Technical Education

- Statewide System of Support "Inclusive Early Education" Expansion State Preschool

- K-12 Education in Context

- Special Education Staffing

- Overview of Governor’s Proposition 98 Budget Pension Costs

February 7, 2018

The 2018-19 Budget

Proposition 98 Education Analysis

- Introduction

- K‑12 Education in Context

- Overview of Governor’s Proposition 98 Budget

- Local Control Funding Formula

- Career Technical Education

- Special Education Teacher Proposals

- “Inclusive Early Education” Expansion

- State Preschool

- Kindergarten

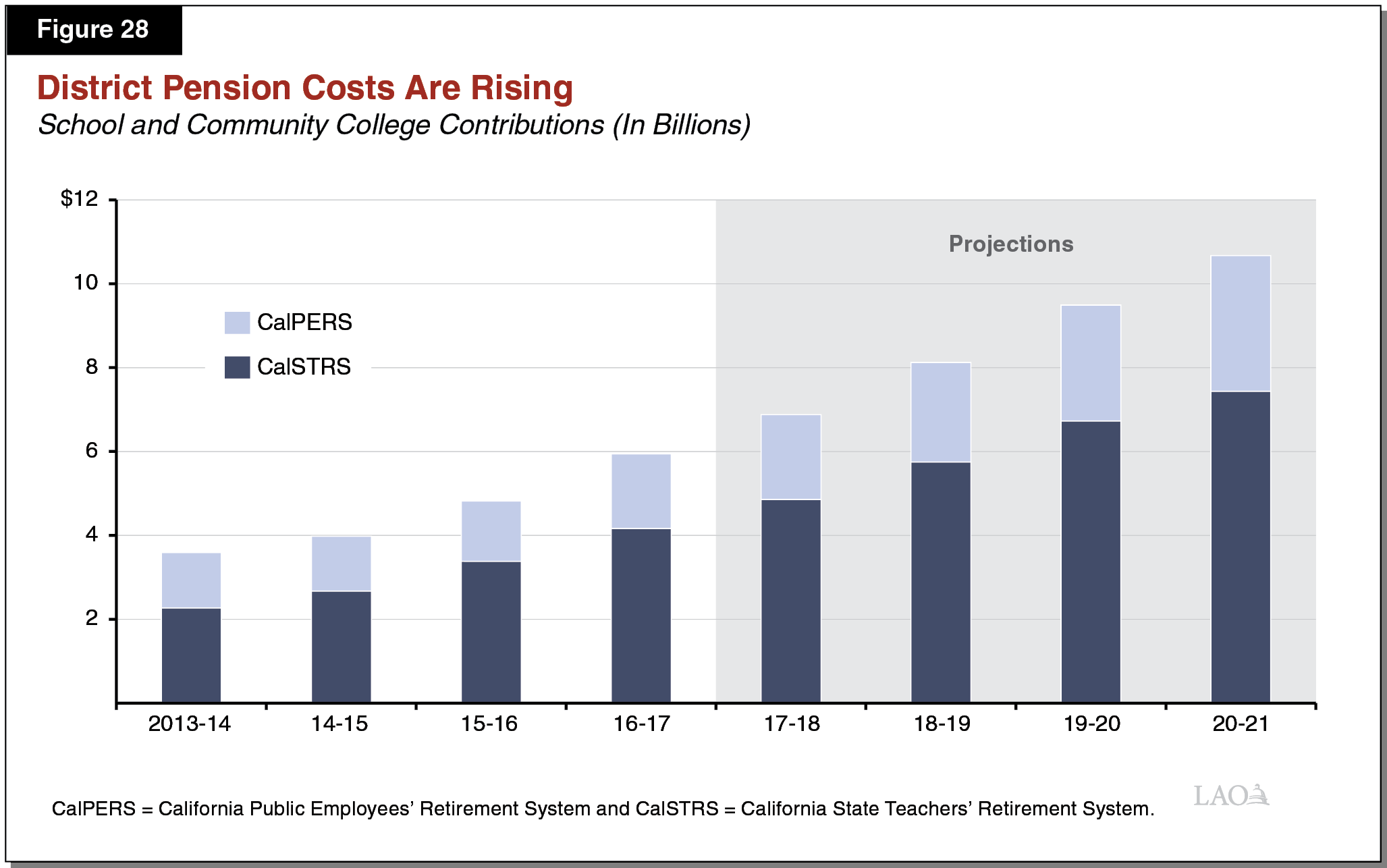

- Pension Costs

- Summary of Recommendations

Executive Summary

In this report, we analyze the Governor’s overall Proposition 98 budget package as well as his specific spending proposals for K‑12 education and early education.

Overall Proposition 98 Budget

Governor’s Budget Contains $6.3 Billion in Proposition 98 Spending Proposals. Of the new spending, almost $5 billion (78 percent) is for K‑12 education, $1.2 billion (19 percent) is for the California Community Colleges (CCC), and $193 million (3 percent) is for the California State Preschool Program. Across the three segments, $3.9 billion is for ongoing programs and $2.4 billion is for one‑time activities. Under the Governor’s budget, overall K‑12 funding per student increases from the revised 2017‑18 level of $11,165 to $11,628 in 2018‑19, an increase of $463 (4.1 percent).

Governor’s Overall Budget Approach Is Reasonable but Some Specific Proposals Do Not Address Root Issues. We think the Governor’s plan to allocate available Proposition 98 funding to a mix of ongoing and one‑time initiatives is reasonable. Including one‑time initiatives reduces the likelihood of programmatic cuts to schools if the state experiences an economic downturn after 2018‑19. Additionally, many of the Governor’s specific proposals—including those relating to the Local Control Funding Formula (LCFF), district support, special education staffing shortages, and career technical education (CTE)—focus on areas of interest to the Legislature. We are concerned, however, that several of the Governor’s proposals are unlikely to address longstanding and systemic underlying problems in these areas. In response to many of these proposals, we offer the Legislature alternatives designed to address root issues. In many cases, these alternatives can be structured to cost less than the funding levels proposed by the Governor.

Key Messages

Reaching Full Implementation of LCFF Creates Opportunity to Reflect. The Governor’s plan to dedicate most new ongoing K‑12 funding to LCFF implementation is consistent with the Legislature’s approach over the past five years. By continuing to prioritize LCFF implementation, the state would be fostering greater local control and flexibility while simultaneously providing more funding for disadvantaged students. Upon reaching full implementation, the Legislature will have many options to consider regarding next steps. We weigh the trade‑offs of six possible options: (1) increasing base rates, (2) increasing supplemental/concentration rates, (3) changing rules for how districts generate funding for English learner and low‑income (EL/LI) students, (4) raising the concentration threshold and rate to target funds to the highest‑poverty districts, (5) providing clearer guidance and/or more flexibility for how high‑poverty districts may use EL/LI funding, and (6) creating new categorical programs. Upon deciding its core policy objectives, the Legislature this year or in coming years might pursue one or more of these options.

Legislature Could Adopt a More Strategic Approach to Retiring the K‑12 Mandate Backlog. The Governor’s budget proposes $1.8 billion in one‑time discretionary grants to schools. The funds would be distributed on a per‑student basis and first applied to districts’ outstanding mandate claims. With two‑thirds of districts having no claims, the bulk of the $1.8 billion would have no effect on the backlog, with the backlog decreasing less than $300 million. As an alternative to the Governor’s approach, we recommend the Legislature identify an amount equal to or in excess of the remaining backlog (about $900 million) and distribute funds on a per‑student basis, but require districts receiving funds to write off all remaining claims. This approach would make substantially more progress toward eliminating the backlog without rewarding districts that have unusually costly claims.

Recommend Alternative Approach to System of Support. The Governor’s budget includes four proposals totaling $76 million that are focused on supporting districts recently identified as having performance issues. We have serious concerns with the Governor’s overall approach to designing this system of support as well as each of his four specific proposals. We recommend the Legislature consider an alternative approach centered around districts rather than county offices of education (COEs). We believe the alternative approach has many advantages. Perhaps most importantly, it promotes district ownership of improvement efforts by allowing districts to choose from multiple teams of experts specializing in their performance issues. It also promotes responsiveness by allowing the California Collaborative on Educational Excellence to contract with new teams of experts each year as new district performance issues emerge. Unlike the Governor’s approach, it does not silo support for general education and special education, provide COEs with additional funding for services that already are funded through their LCFF allocations, or create new regional entities with poorly defined roles. It also costs substantially less ($30 million compared to $76 million).

Recommend LCFF Approach to CTE, but Modify Existing CTE Program if Taking Categorical Approach. The Governor’s budget provides $212 million for a high school CTE program run out of CCC. The Governor’s primary objective of running the program out of CCC is to improve coordination between schools, community colleges, and industry partners. We recommend the Legislature fund CTE from LCFF. If the Legislature has concerns that schools will not offer CTE under the LCFF structure, the Legislature could consider modifying the formula (for example, increasing the high school base rate) or modifying the accountability system (for example, establishing separate college and career readiness indicators). Though we believe funding CTE within LCFF promotes more coherent planning as well as clearer and stronger accountability, the Legislature might consider creating a CTE categorical program. If the Legislature takes this approach, we recommend it reject the Governor’s Strong Workforce approach and instead modify the existing CTE Incentive Grant program. Specifically, we recommend the Legislature (1) set a minimum threshold of CTE coursework that must be aligned with regional workforce needs, (2) require school and college districts to share data and accountability for CTE student outcomes, and (3) fold in funding from four other high school CTE programs.

Recommend Comprehensive Approach to Addressing State’s Special Education Staffing Shortages. The Governor proposes two one‑time grant programs totaling $100 million to support special education teacher recruitment, training, and retention. While we commend the Governor for focusing on the longstanding problem of special education staffing shortages in the state, we are concerned that his proposals fail to address the root causes of these shortages—most notably a lack of pay differentials for special education teachers, and to a lesser extent, overly restrictive education and credentialing requirements. The Governor’s proposals also do not address the longstanding shortages of special education specialists (such as speech therapists). We recommend the Legislature reject both of the Governor’s proposals and instead pursue changes that address the root causes of these shortages. Specifically, we recommend schools establish ongoing pay differentials for special education teachers. At the state level, we recommend pursuing a variety of actions, including reducing the number of special education credentials, authorizing a four‑year degree pathway option for special education teachers, and providing targeted enrollment funding for the California State University to expand certain graduate specialist training programs.

Introduction

In this report, we analyze the Governor’s budget proposals for K‑12 education and early education. In the first section of the report, we provide background on public schools in California. We then provide an overview of the Governor’s Proposition 98 budget package. In the remaining sections of the report, we analyze the Governor’s specific school and early education proposals and examine a few related issues, including school pension costs. The report also contains two sections responding to statutory requirements. In these two sections, we examine (1) state funding rates for kindergarten and (2) health and safety standards for school districts offering State Preschool. In our forthcoming Higher Education Analysis, we provide background on the California Community Colleges, also funded by Proposition 98, and discuss the Governor’s specific community college proposals. On the “EdBudget” portion of our website, we post dozens of tables containing additional detail about the Proposition 98 budget.

K‑12 Education in Context

In this section, we answer many questions legislators and others commonly ask about K‑12 education in California. We begin by providing information on the main components of California’s public school system. We then review the state’s K‑12 accountability system. Lastly, we explain the basics of school finance in California.

California’s Public School System

Below, we describe California’s students, teachers and staff, local education agencies (LEAs), and state education agencies.

Students

California Has More Than 6 Million Public K‑12 Students. In 2016‑17, California’s public schools enrolled 6.2 million students, representing 12 percent of all public school students in the nation. About two‑thirds of these students were in grades kindergarten through eight, with one‑third attending high school. From the mid‑2000s through 2013‑14, K‑12 attendance remained essentially flat. Since 2014‑15, attendance has declined slightly each year.

Almost Six in Ten California Students Are Identified as Low Income. In 2016‑17, 58 percent of California’s public school students were eligible to receive a free or reduced price school meal under a large federal nutrition program. States frequently use this eligibility measure as an indicator of a student coming from a low‑income family. Qualifying students come from families earning no more than 185 percent of the federal poverty level. In 2016‑17, this level equated to $45,000 for a family of four. California’s rate of free or reduced price meal eligibility is above the nationwide rate of 52 percent.

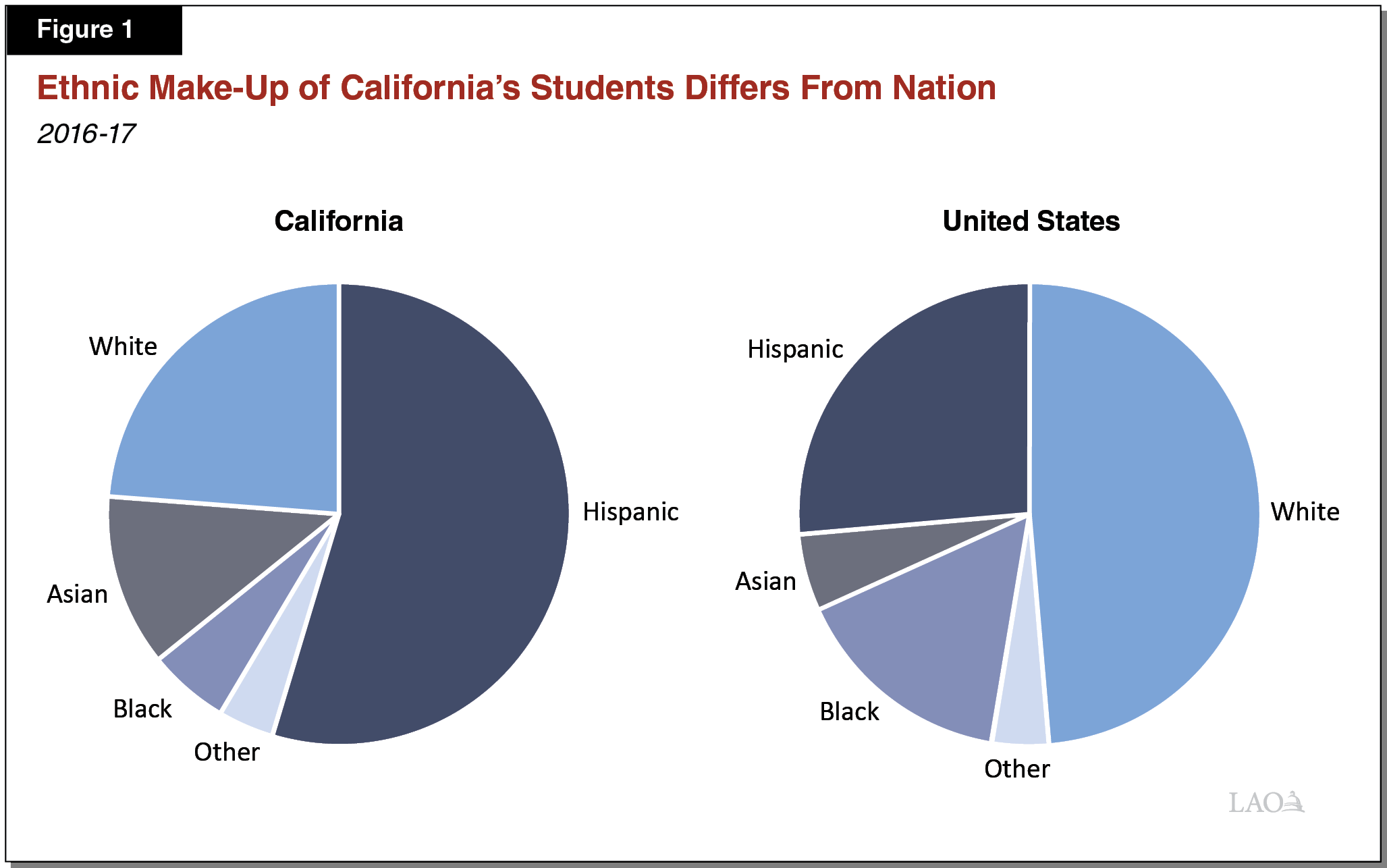

About Half of California Students Are Hispanic. As Figure 1 shows, the ethnic make‑up of California’s students differs notably from the nation. Whereas about half of California’s students are of Hispanic origin and about one‑quarter are white, in the United States those shares are flipped. Differences exist among other ethnic groups too, with Asian students comprising a larger share of students in California than the nation (12 percent and 5 percent, respectively), and black students comprising a smaller share (6 percent in California compared to 16 percent nationwide).

About One‑Fifth of California Students Are English Learners. Students are classified as English learners based on a home language survey and their performance on a test of English proficiency. In 2016‑17, 21 percent (1.3 million) of California students were classified as English learners—a higher proportion than in any other state. Three out of every ten English learners in the nation attend school in California. Even more California students—almost 2.7 million students overall—speak a primary language other than English at home, but almost half of these students are considered fluent in English. California students come from families speaking over 65 different home languages, although the vast majority (78 percent) speak Spanish, with Vietnamese the next most common language (3 percent).

About One in Ten California Students Are Identified as Having a Disability Affecting Their Education. In 2016‑17, about 754,000 California students (12 percent) were identified with a disability affecting their education. Pursuant to federal law, schools must provide these students with special education services. California identifies a slightly smaller proportion of students for special education than the rest of the nation (13 percent). Specific learning disabilities such as dyslexia are the most common diagnoses requiring special education services (affecting 5 percent of the state’s K‑12 students), followed by speech and language impairments (affecting 3 percent of California’s students). Although autism remains a relatively rare diagnosis (affecting 1.7 percent of California’s students), the number of students diagnosed with this disability has increased notably (from 14,000 children in 2000‑01 to 105,000 in 2016‑17).

Staffing

California Has Almost 300,000 Teachers. In 2016‑17, about 296,000 full‑time‑equivalent teachers were employed in California’s public school system. Roughly three‑quarters of teachers are women, similar to the share in other states. Compared to the student population, teachers are more likely to be white (66 percent of teachers compared to 24 percent of students) and less likely to be Hispanic (21 percent of teachers compared to 55 percent of students). Over the past five years, the state’s teacher workforce has increased at an average annual rate of 1.5 percent per year.

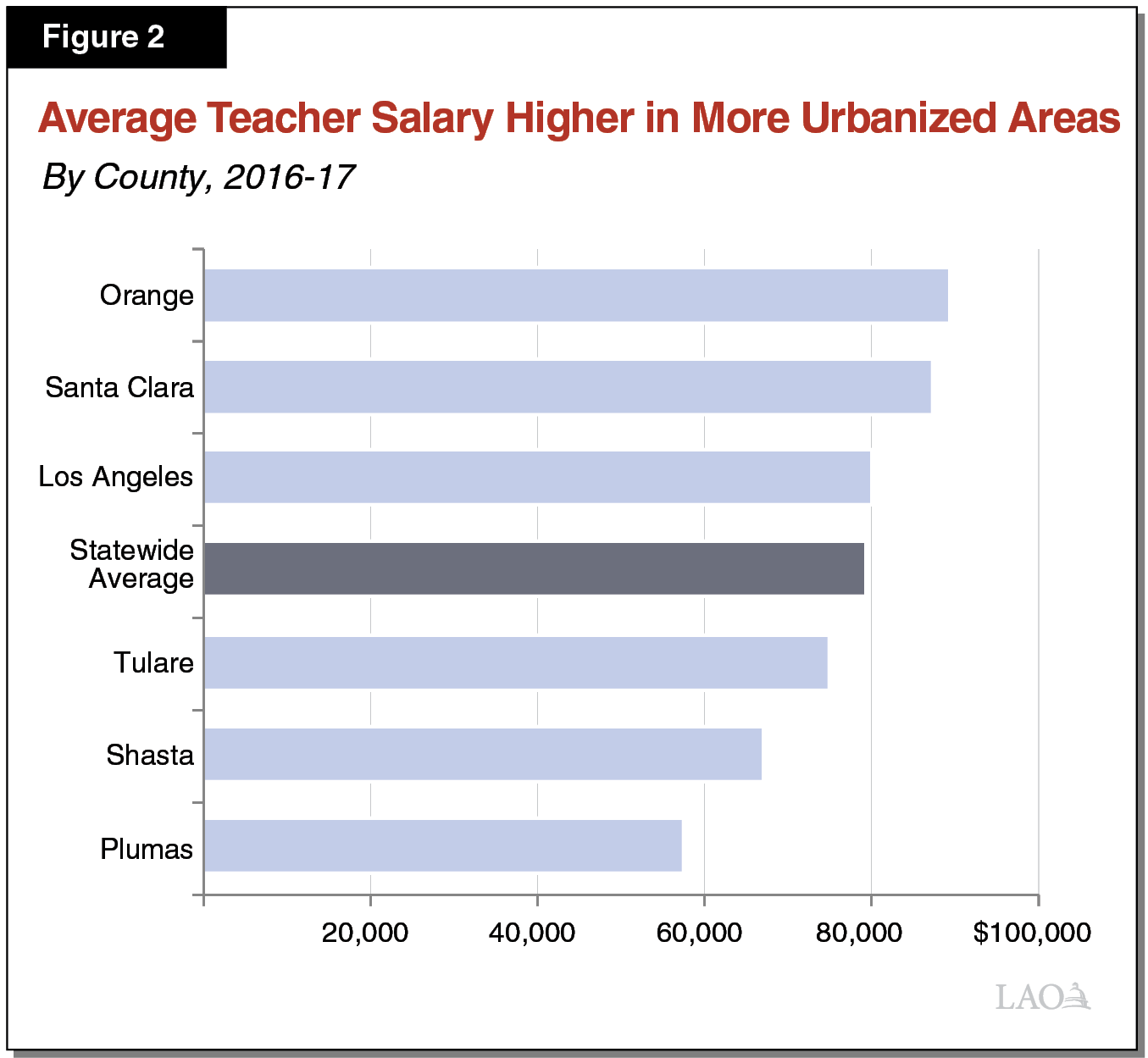

Teacher Salaries Vary Across the State, Are Higher on Average Than Other States. In California, the state requires most LEAs to set teacher salary levels through collective bargaining. As Figure 2 shows, teacher salaries vary widely across the state, with salaries generally higher in urbanized areas than rural areas. In 2016‑17, the average teacher salary was $79,100—34 percent higher than the national average. California consistently ranks among the top states for teacher salary, along with Connecticut, New York, New Jersey, and Massachusetts.

California Has Highest Student‑to‑Teacher Ratio in Nation. Though California’s teachers tend to be better paid than the rest of the nation, the state has comparatively fewer of them. Over the five‑year period from 2010 through 2014, the national average student‑to‑teacher ratio hovered at 16. California’s ratio was notably higher throughout this period, but it has been declining steadily since 2011‑12. In 2016‑17, California’s student‑to‑teacher ratio was 20.4.

California Has 306,000 Other School Staff. In addition to teachers, schools employed 306,000 full‑time‑equivalent staff in various administrative and support positions in 2016‑17. This number includes 26,000 principals, assistant principals, and other school administrators (equating to about 1 school manager for every 11 teachers). It also includes 29,000 pupil services personnel (primarily counselors, psychologists, and speech pathologists). Similar to teachers, both administrators and pupil services personnel must hold a state credential. The remaining 251,000 employees work in positions that do not require a credential. These employees—known as classified staff—include clerical workers, janitors, teacher aides, and bus drivers.

Local Education Agencies

School Districts and Charter Schools Provide Most Instruction. The public school system comprises many LEAs. In 2016‑17, 945 school districts and 1,248 charter schools operated in California—typically offering comprehensive educational programs for students in their local areas. In addition, county offices of education (COEs) operate certain types of schools for at‑risk students, including students who are incarcerated or have been expelled. Many COEs also operate special education, career technical education, adult education, and preschool programs. California’s public school system also includes seven state‑run schools—consisting of three special schools for blind or deaf students and four schools for students incarcerated at state juvenile justice facilities.

Size of California School Districts Varies Dramatically. As Figure 3 shows, California’s school districts vary greatly in size. One‑quarter of school districts are very small, serving 300 or fewer students. Another one‑third are small, serving between 301 and 2,500 students. Whereas these two sets of districts combined comprise more than half of all districts in California, they account for only 7 percent of all students. At the other extreme, 12 very large districts each serve more than 40,000 students and together educate one‑fifth of all students in the state. The number of school districts in each county also varies across the state, with seven counties containing a single district each, and the most populous county (Los Angeles) containing 80 districts.

Figure 3

California School Districts Vary Greatly in Size

2016‑17

|

District Sizea |

Number of Districts |

Percent of All Districts |

Total Students |

Percent of All Students |

|

Less than 300 |

242 |

26% |

28,986 |

1% |

|

301 to 2,500 |

311 |

33 |

347,203 |

6 |

|

2,501 to 5,000 |

132 |

14 |

485,979 |

9 |

|

5,001 to 10,000 |

110 |

12 |

816,719 |

15 |

|

10,001 to 40,000 |

138 |

15 |

2,588,579 |

48 |

|

40,001+ |

12 |

1 |

1,076,310 |

20 |

|

Totals |

945 |

100% |

5,343,776 |

100% |

|

aBased on average daily attendance. Excludes charter school attendance. |

||||

Charter Schools Are Fast Growing. Charter schools are publicly funded schools that are similar to traditional schools in that they must employ state‑certified teachers, teach the same state academic standards, and administer the same state assessments. They differ from district‑operated schools, however, in that they are exempt from certain state laws. In exchange for these exemptions, they must adhere to locally developed, approved, and periodically renewed charters. These local charters are intended to give schools more flexibility over the design of their education programs. While the total number of K‑12 students declined slightly over the past decade, charter school attendance nearly tripled, growing at an average annual rate of 11 percent. In 2016‑17, charter schools served 580,000 students (10 percent of the statewide total), up from 210,000 students (3 percent of the statewide total) in 2006‑07. In 2016‑17, charter schools ranged in size from 5 students to more than 5,000 students, with an average school size of 473.

COEs Typically Provide Countywide Support Services. In addition to providing some specialized forms of direct student instruction, COEs offer a variety of services to school districts. Many COEs, for example, operate countywide payroll systems and provide professional development for teachers and administrators. COEs also are required to review and approve school districts’ annual budgets, monitor the fiscal health of districts several times per year, and review districts’ strategic academic plans, known as Local Control and Accountability Plans (LCAPs). The COEs also will have a support role in helping school districts that do not meet performance standards, but this system remains in development.

State Education Agencies

California Department of Education (CDE) Administers Education Programs. The department monitors compliance with state education laws and regulations, collects and compiles education data, allocates funding, and provides support to LEAs. The department has an annual budget of around $270 million and about 1,600 employees—rendering it midsized compared with other departments within California state government. More than two‑thirds of CDE’s funding comes from federal funds, as many of CDE’s activities are associated with federal programs. The Superintendent of Public Instruction (SPI)—a nonpartisan position elected by the voters—oversees the department.

A Few Other State Agencies Involved in Major Aspects of K‑12 Education. In addition to CDE, the following state entities are involved in major aspects of K‑12 education:

- The State Board of Education (SBE) adopts regulations to implement certain state laws and reviews LEA waiver requests. In recent years, the board’s most significant decisions have related to LCAPs. The board has an annual budget of $2.6 million (state General Fund) and about ten employees.

- The Commission on Teacher Credentialing (CTC) is responsible for accrediting teacher preparation institutions, credentialing teachers, and investigating allegations of teacher misconduct. CTC has an annual budget of around $25 million (special fund) and about 140 employees.

- The Office of Public School Construction (OPSC), an office within the Department of General Services, reviews school facility projects to determine if they qualify for state bond funding. OPSC has an annual budget of around $9 million (bond funding) and about 50 employees.

State Contracts With Some COEs to Perform Statewide Functions. In addition to these state entities, the state contracts with some COEs to undertake activities that have statewide benefits. The Fiscal Crisis and Management Assistance Team (affiliated with the Kern COE) provides fiscal advice, management assistance, and other budget‑related training to school districts across the state. California School Information Services (also affiliated with the Kern COE) helps LEAs across the state with data management issues. The K‑12 High Speed Network (affiliated with the Imperial COE) assists schools with Internet connectivity. The California Collaborative for Educational Excellence or CCEE (affiliated with the Riverside COE), assists certain LEAs with improving their student outcomes. The state also contracts with the San Joaquin COE to maintain two websites (the California School Dashboard and the School Accountability Report Card) that make school district performance data publicly available. Additionally, the state sometimes competitively bids limited‑term contracts with select COEs to administer special initiatives, such as conducting statewide teacher recruitment campaigns and providing statewide training on salient issues.

Accountability

Below, we describe the state’s current academic standards and student assessments. We next review trends in student performance. We then explain how the state supports LEAs identified as underperforming.

Academic Standards

Like Most States, California’s Instruction Is Based on Common Core State Standards. In 2010, at the direction of the Legislature, SBE adopted the Common Core State Standards (with the addition of a few California‑specific standards) as the foundation for what students should know and be able to do in English language arts and math. In 2012, the state adopted standards aligned to the Common Core for English Learners. Forty‑two states and the District of Columbia have adopted the Common Core State Standards.

State Is Implementing New Science Standards. In 2013, California adopted the nationally developed Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS). California was a lead state partner in the development of these new standards. SBE adopted initial guidance on how to teach the new science standards in 2016. Some schools currently are field testing the new guidance and implementing the new science standards, with the plan to have all schools teach the new standards beginning in 2018‑19.

Student Assessments

Federal Law Requires States to Administer Standardized Tests. As a condition of receiving federal education funding, federal law requires states to assess students in English language arts and math in grades 3 through 8 and at least once from grades 10 through 12. In addition, federal law requires states to assess students in science at least once during: (1) grades 3 through 5, (2) grades 6 through 9, and (3) grades 10 through 12. States also are required to assess the English proficiency of English learners each year.

First Exams Aligned to Common Core State Standards Administered in Spring 2015. Although SBE adopted the Common Core State Standards in 2010, schools were not expected to have their instruction aligned with the new standards until 2014‑15. In spring 2015, the state replaced its previous testing program with new assessments aligned to the Common Core standards. The new assessments were developed by the Smarter Balanced Assessment Consortium (SBAC), a group of 17 states, with California a lead member. The SBAC assessments measure proficiency in reading, writing, and mathematics and are administered online using a computer or tablet. As an alternative to the Common Core assessments, students with the most severe disabilities take the California Alternate Assessments (CAAs)—first implemented in 2016‑17.

State Is Developing Several Other Exams. The state is in the final stages of developing the California Science Test (CAST). It plans to field test CAST in 2017‑18, with all districts administering CAST in 2018‑19. The state also recently created the English Language Proficiency Assessments for California (ELPAC). The ELPAC assesses the English proficiency of English learners. Districts are to administer the annual end‑of‑year ELPAC exams beginning in the spring of 2018 and the diagnostic component of ELPAC beginning in July 2018. The state is in the early stages of developing a Spanish language assessment aligned to the Common Core. Schools could use this optional exam for students receiving instruction in Spanish, English learners enrolled in school for less than 12 months, or other students interested in assessing their proficiency in Spanish.

Student Performance

Performance on New Assessments Improved in 2016, Remained Flat in 2017. In 2017, 49 percent of California students met or exceeded standards in English language arts. This rate was essentially unchanged compared with the 2016 exams but better than the first administration of the exams in 2015—when 44 percent of students met or exceeded standards. Performance on math followed a similar trajectory, with 38 percent of students meeting or exceeding standards in 2017, essentially unchanged from 2016, but higher than 2015 (33 percent).

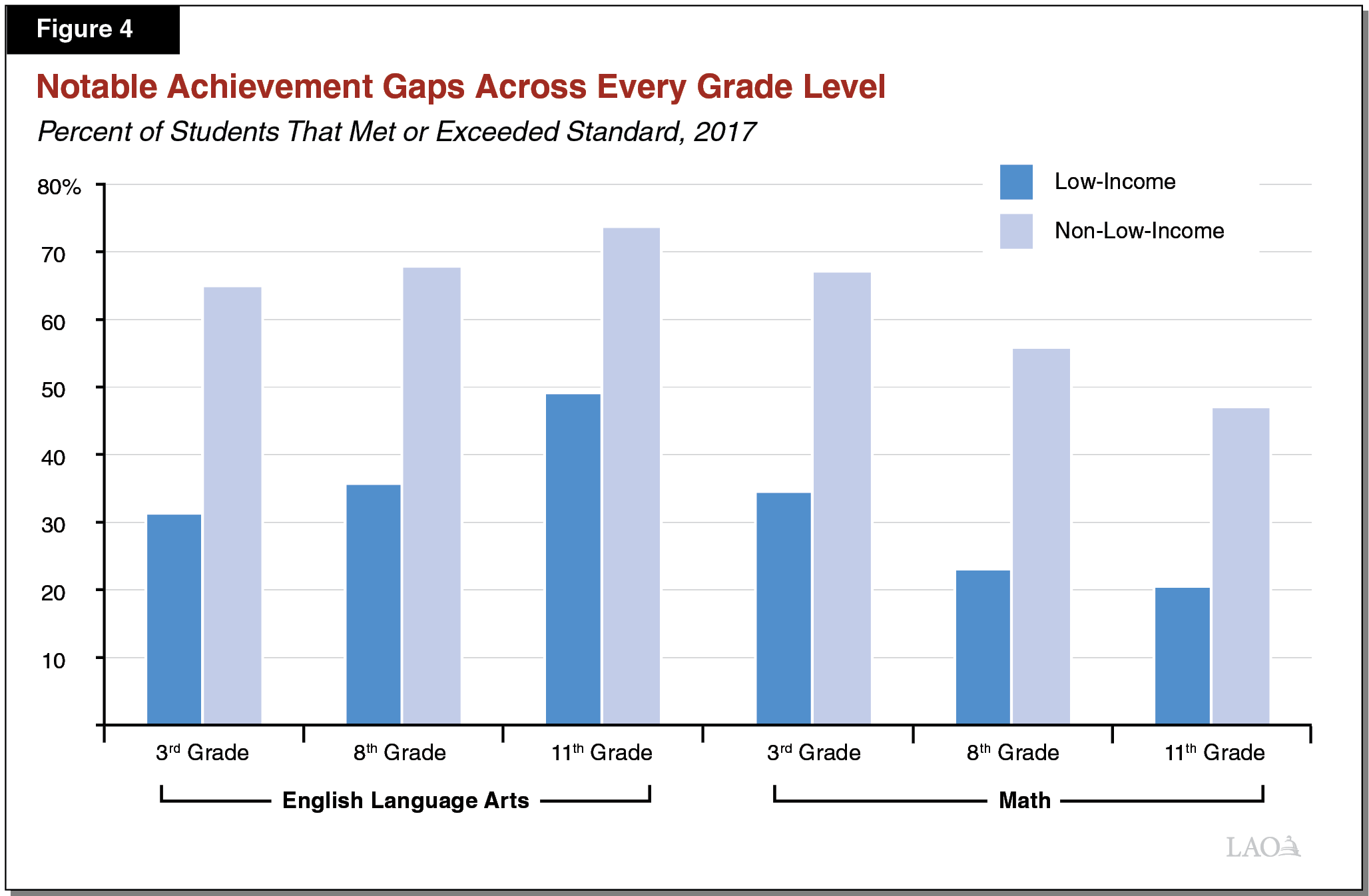

Large Achievement Gaps Exist. Results on the exams show significant achievement gaps between the scores of low‑income and non‑low‑income students. As Figure 4 shows, 36 percent of low‑income students met or exceeded the state standards in eighth grade English language arts, compared with 68 percent of non‑low‑income students. The gaps are similar at other grade levels and for math.

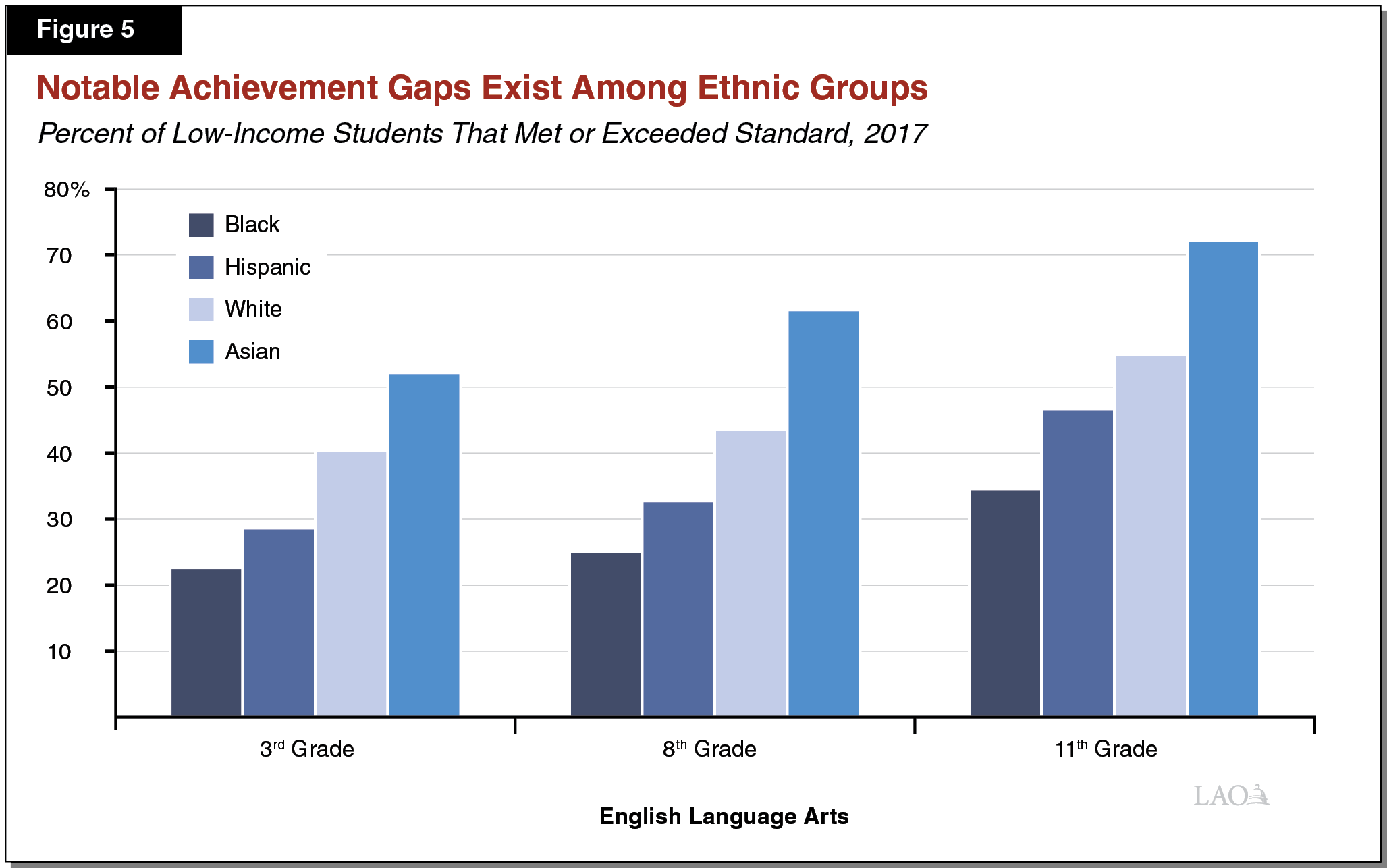

Outcomes Also Vary by Ethnicity. Results on statewide exams show significant achievement gaps among California’s four largest ethnic groups. These gaps persist even after controlling for income. As Figure 5 shows, low‑income black and Hispanic students have lower proficiency rates on eighth grade English language arts exams (25 percent and 33 percent, respectively) than low‑income white and Asian students (44 percent and 62 percent, respectively). Similar differences among groups exist in third and eleventh grade.

California Ranks Near the Bottom on National Tests. The federal government administers the National Assessment of Educational Progress every two years. The most recent assessment results (2015) show that California performs near the bottom in reading and math for fourth and eighth grades. The performance of non‑low‑income students in California (39th in eighth grade reading) ranks a little bit higher than the performance of low‑income students (45th in eighth grade reading). California’s performance compared to other states has not changed significantly in the past ten years. In addition to having lower performance compared to other states, California has among the largest achievement gaps between low‑income and non‑low‑income students. In fourth grade reading, for example, California’s achievement gap ranked 49th in the country (that is, 48 states had achievement gaps smaller than California).

Five in Six Students Graduate High School Within Four Years. Of the cohort of students that entered ninth grade in the 2012‑13 school year, 84 percent graduated within four years. Of the same cohort, 10 percent dropped out of school, 6 percent returned to school for a fifth year, and less than 1 percent received either a High School Equivalency Certificate (if they passed the General Educational Development Test) or a special education certificate of completion.

More Students Are Completing Coursework Required for University Eligibility. In 2016, 45 percent of California students graduated high school having completed the coursework required to be eligible for admission to the California State University and University of California. This proportion has been gradually increasing over the last 20 years. In 1996, 35 percent of California high school graduates completed such coursework. (To be eligible for university admission, students also must meet certain grade point average requirements and take college entrance exams.)

LEA Support

California in Midst of Developing a New Accountability System. The past few years the state has been developing a new system for measuring district performance and supporting districts identified as having poor performance. The state recently decided to use outcome data from the School Dashboard to identify school districts in need of support. Districts are identified when the School Dashboard data reveals poor performance for one or more student subgroups. To measure performance, the state currently looks at student test scores, English learner progress, graduation rates, and suspension rates. Beginning next year, the state also will look at chronic absenteeism and the rate of high school graduates prepared for college/career. In fall 2017, a total of 228 districts were identified for support. Of these districts, 164 (72 percent) were identified solely for poor performance of their students with disabilities.

California in Midst of Aligning Accountability System With New Federal Rules. Whereas the state’s new accountability system identifies districts in need of support, the federal Every Student Succeeds Act (2015) requires states to provide extra support to the lowest performing 5 percent of schools. Sometime in 2018, the state expects to have developed its methodology for identifying these schools.

Underperforming LEAs Are to Receive Extra Support. The state is in the process of determining how to support districts and schools identified as needing support. In developing the system of support, the state is considering the roles of districts, COEs, regional COE hubs, and CCEE. Many key decisions regarding this new system likely will be made in 2018.

Finance

Below, we describe how California funds its schools, explain its ranking on measures of per‑pupil spending, and describe how districts typically use their funding.

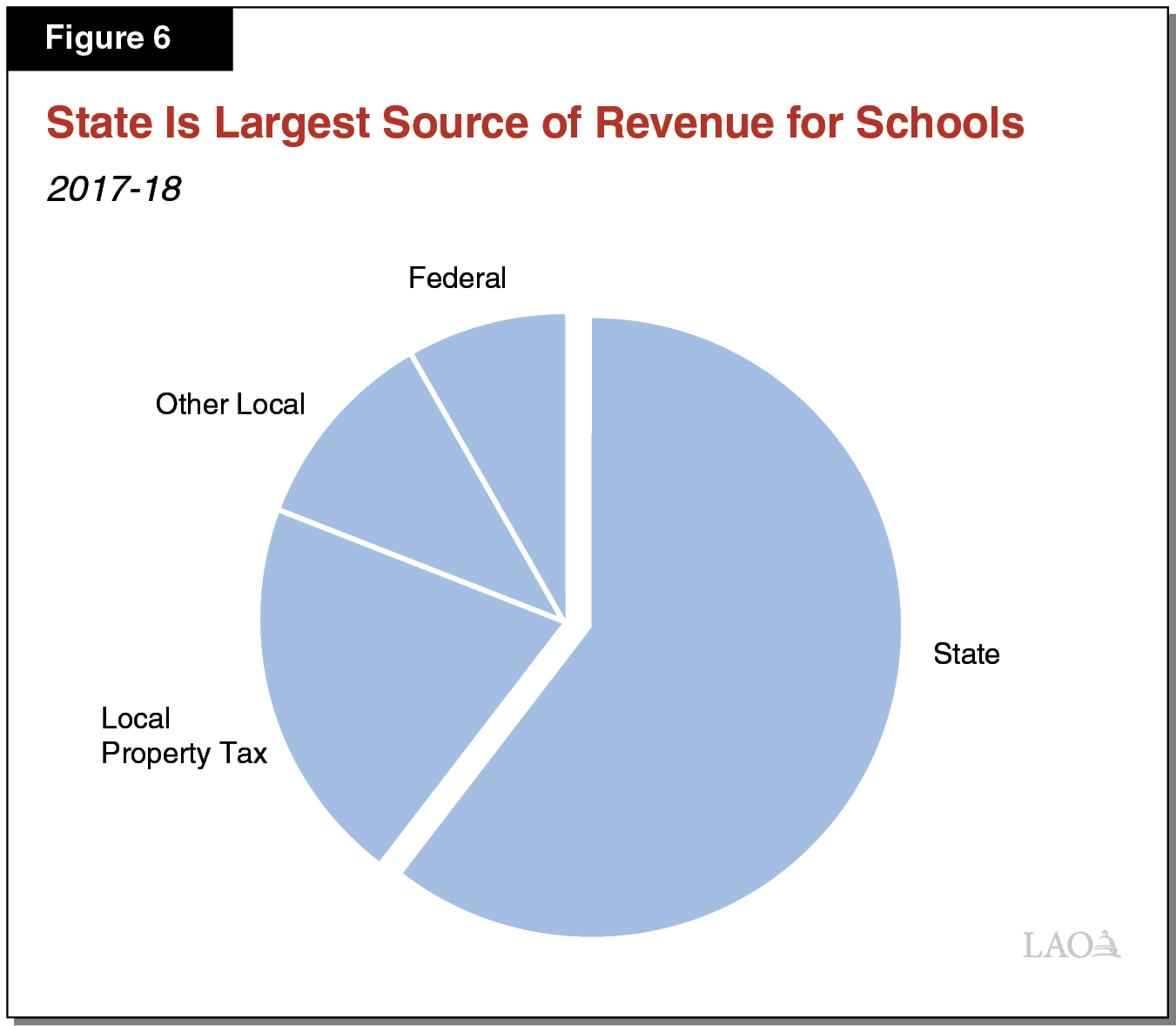

State Is Primary Source of Funding for Schools. In 2017‑18, schools received $93 billion in total funding from all sources. As Figure 6 shows, the largest share of school funding comes from the state, with smaller shares coming from local sources (primarily local property tax revenue) and the federal government. (Revenues from the state lottery account for 1 percent of all revenue.) These proportions differ from many other states, where local property tax revenue covers a much larger share of school funding. Unlike most other states, California’s State Constitution limits local property tax rates.

Per‑Pupil Funding Has Risen Notably in Recent Years. Most comparisons of school funding focus on state General Fund and local property tax revenue, the two revenue sources over which the state has the greatest control. The 2017‑18 Budget Act provided schools with $11,067 per student from these sources, an increase of about $2,400 (28 percent) over the level provided five years ago. Adjusted for inflation, per‑pupil funding is at its highest level in three decades (since the enactment of Proposition 98 in 1988).

California Per‑Pupil Spending Ranks in the Middle Among the States. Based on spending data from 2014‑15 (the most recent year for which national data are available), California ranked 29th in per‑pupil spending among the 50 states and the District of Columbia. Over the past decade, California has ranked as high as 23rd (in 2007‑08) and as low as 36th (from 2010‑11 through 2012‑13). Because California’s revenues are highly sensitive to changes in the economy, school spending tends to be more sensitive to recessions and recoveries than most other states. Given California has increased school funding significantly since 2014‑15, its ranking likely will increase as new data are released over the next few years. (Some organizations calculate per‑pupil spending with adjustments for regional costs. In these rankings, California typically ranks much lower.)

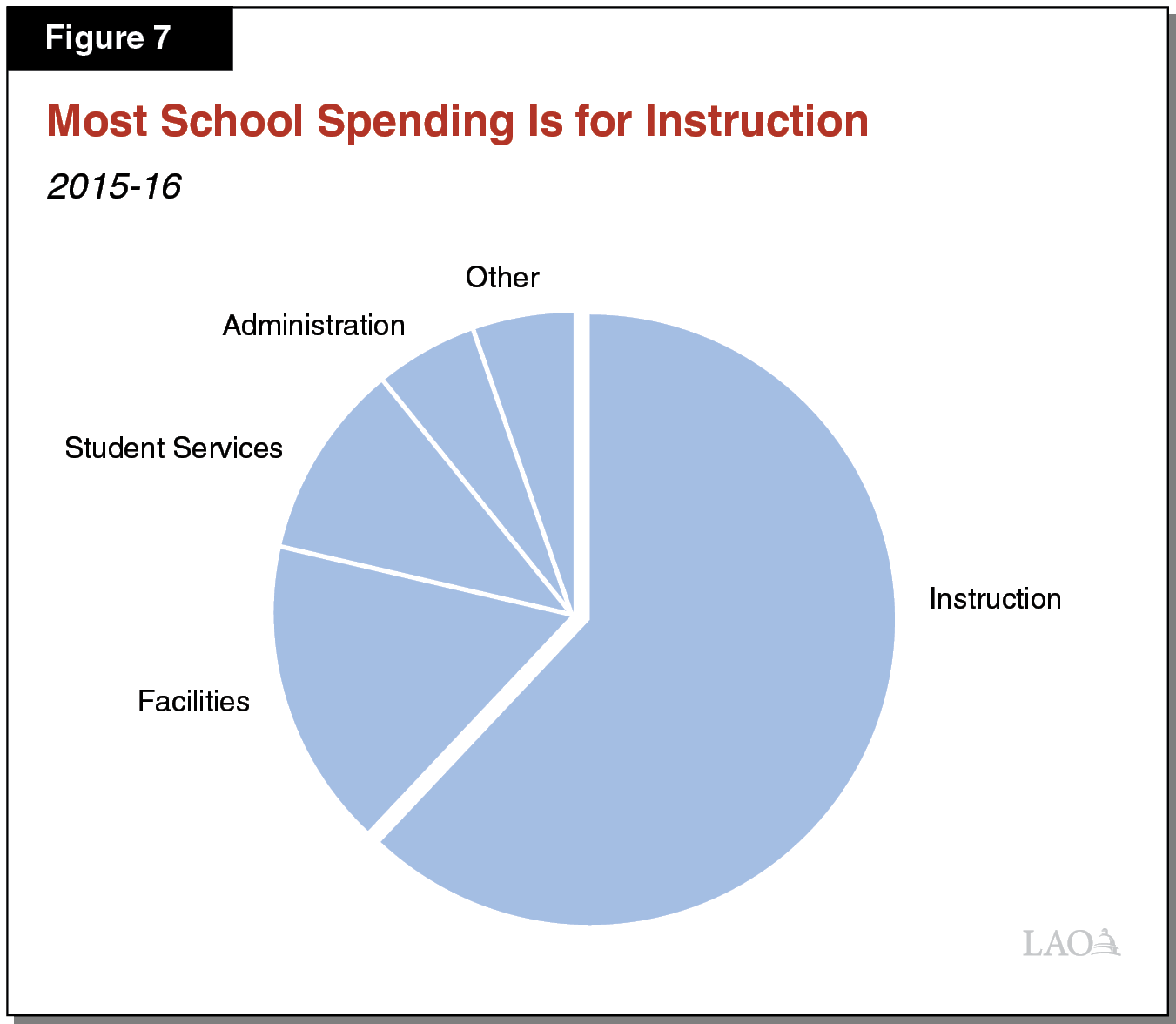

Most School Spending Is for Instruction. As Figure 7 shows, 62 percent of school expenditures in 2015‑16 related to instruction and instructional support—largely paying teacher salaries and benefits. Schools spent 17 percent of their funds on facilities, including land acquisition, construction, and maintenance. Schools spent 11 percent on student services, including school meals, pupil transportation, counseling, and health services. The remaining funds were spent on central administration, including the compensation of district superintendents; central business, legal, and human resource functions; and other expenses, including printing.

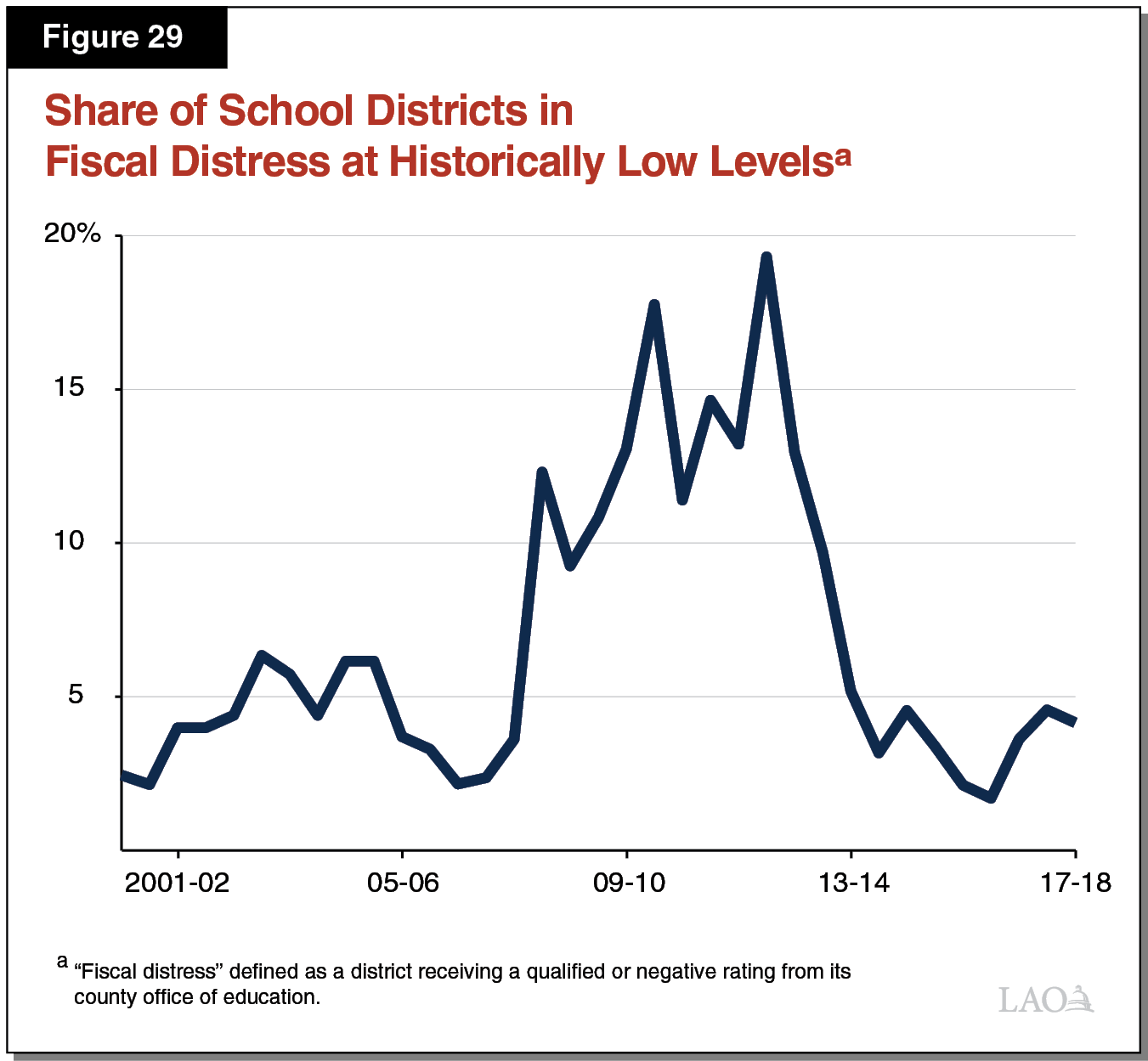

State Has Longstanding System for Monitoring Districts’ Fiscal Health. In 1991, the state established a fiscal oversight system requiring COEs to review the financial condition of their school districts at various points during the year. If a COE determines that a district is in fiscal distress, it can undertake additional oversight, such as assigning a fiscal expert or requiring more frequent financial reports from the district. If the district’s financial condition does not improve, the COE can take stronger action, such as rescinding the actions of the district’s governing board. When a district gets to the point of being unable to pay its bills, the state provides an emergency loan so that the district can continue to operate and appoints an administrator to manage the district while it implements a recovery plan. This fiscal oversight system generally has been effective, with only eight districts requiring emergency state loans since 1991. (By comparison, 27 districts required such assistance over the ten years preceding the adoption of the 1991 system.)

Overview of Governor’s Proposition 98 Budget

In this section, we provide a high‑level overview and assessment of the Governor’s Proposition 98 budget package. The first part analyzes the major spending proposals in the package and the second part analyzes the administration’s estimates of the Proposition 98 minimum guarantee.

Major Spending Proposals

Below, we describe the Governor’s Proposition 98 spending package and highlight his major proposals for K‑12 education and preschool. We also provide our assessment of the Governor’s overall spending approach.

Overview

Across Three Years, $6.3 Billion in Proposition 98 Spending Proposals. The Governor’s budget contains a total of $6.3 billion in new Proposition 98 spending proposals (see Figure 8). Of the new spending, almost $5 billion (78 percent) is for K‑12 education, $1.2 billion (19 percent) is for the California Community Colleges (CCC), and $193 million (3 percent) is for the California State Preschool Program. As the figure shows, the spending package consists of a mix of ongoing and one‑time proposals. Across the three segments, $3.9 billion is for ongoing programs and $2.4 billion is for one‑time activities.

Figure 8

Governor’s Budget Contains $6.3 Billion in Proposition 98 Spending Proposals

(In Millions)

|

K‑12 Education |

|

|

Ongoing |

|

|

Fund full implementation of LCFF |

$2,883 |

|

Provide 2.51 percent COLA for select categorical programsa |

106 |

|

Provide county and regional support for low‑performing districts |

76 |

|

Make other ongoing augmentations |

29 |

|

Subtotal |

($3,095) |

|

One Time |

|

|

Provide per‑student discretionary grants |

$1,757 |

|

Establish special education teacher residency program |

50 |

|

Provide grants for addressing special education teacher shortage |

50 |

|

Support Southern California Regional Occupational Center |

3 |

|

Subtotal |

($1,860) |

|

Total |

$4,954 |

|

California Community Colleges |

|

|

Ongoing |

|

|

Increase apportionment funding and implement new allocation formula |

$396 |

|

Fund high school CTE initiative through Strong Workforce Program |

212 |

|

Fund AB 19 fee waiver program and consolidated financial aid program |

79 |

|

Provide ongoing support for new online college |

20 |

|

Make other ongoing augmentations |

51 |

|

Subtotal |

($759) |

|

One Time |

|

|

Fund deferred maintenance and instructional materials |

$275 |

|

Provide one‑time support for new online college |

100 |

|

Fund other one‑time activities |

53 |

|

Subtotal |

($428) |

|

Total |

$1,186 |

|

Preschool |

|

|

Ongoing |

|

|

Increase Standard Reimbursement Rate by 2.8 percent |

$32 |

|

Provide 2.51 percent COLA |

28 |

|

Add 2,959 full‑day slots starting April 1, 2019 |

8 |

|

Subtotal |

($68) |

|

One Time |

|

|

Fund early education expansion |

$125 |

|

Total |

$193 |

|

Grand Total of All Spending Proposals |

$6,333 |

|

aApplies to special education, child nutrition, mandates block grant, services for foster youth, adults in correctional facilities, and American Indian education. LCFF = Local Control Funding Formula; COLA = cost‑of‑living adjustment; and CTE = career technical education. |

|

Per Student Funding Increases Notably. Figure 9 shows the distribution of Proposition 98 funding by segment across the period. Under the Governor’s budget, overall K‑12 funding per student (including preschool and other agencies) increases from the revised 2017‑18 level of $11,165 to $11,628 in 2018‑19, an increase of $463 (4.1 percent).

Figure 9

Proposition 98 Funding by Segment

(Dollars in Millions, Except Funding Per Student)

|

2016‑17 Revised |

2017‑18 Revised |

2018‑19 Proposed |

Change From 2017‑18 |

||

|

Amount |

Percent |

||||

|

Segment |

|||||

|

K‑12 education |

$62,048 |

$65,340 |

$67,695 |

$2,355 |

3.6% |

|

California Community Colleges |

8,283 |

8,654 |

9,207 |

553 |

6.4 |

|

Preschool |

975 |

1,122 |

1,338a |

216 |

19.2 |

|

Other agencies |

85 |

95 |

85 |

‑10 |

‑10.7 |

|

Totals |

$71,390 |

$75,211 |

$78,324 |

$3,114 |

4.1% |

|

Enrollment |

|||||

|

K‑12 average daily attendance |

5,960,037 |

5,961,253 |

5,944,090 |

‑17,163 |

‑0.3% |

|

Community college FTE students |

1,134,809 |

1,135,081 |

1,136,813 |

1,733 |

0.2 |

|

Funding Per Student |

|||||

|

K‑12 educationb |

$10,588 |

$11,165 |

$11,628 |

$463 |

4.1% |

|

California Community Colleges |

7,299 |

7,624 |

8,099 |

475 |

6.2 |

|

aIncludes $125 million for one‑time grants to fund the expansion of early education programs, including preschool. Excluding this amount, the increase from 2017‑18 is $91 million (8.1 percent). bPer‑pupil amount combines funding for K‑12 education, preschool, and other agencies. FTE = full‑time equivalent. |

|||||

K‑12 Education

Funds Full Implementation of LCFF. The Governor proposes a $2.9 billion increase for LCFF to close the remaining gap to the formula targets and provide a 2.51 percent cost‑of‑living adjustment (COLA). Reaching full implementation in 2018‑19 would be two years ahead of schedule. The budget also includes $106 million to provide a 2.51 percent COLA for several categorical programs that remain outside LCFF (most notably special education).

Funds New High School Career Technical Education (CTE) Program Through CCC Budget. The Governor proposes a new $212 million high school career technical education program funded through the existing Strong Workforce Program administered by the community colleges. Of this amount, $200 million is for existing Strong Workforce consortia consisting of colleges, school districts, and industry partners. The consortia, in turn, would allocate the new funds to school districts through competitive grants. The remaining $12 million would fund local industry experts who would provide technical assistance to school districts with CTE programs.

Funds New System of Support for School Districts. The Governor proposes a $76 million package of initiatives to support districts with performance issues. Of this amount, the majority ($55 million) would fund COEs to support districts identified for improvement under the state’s new accountability system. The package also includes $10 million for special education agencies to support districts identified for improvement due to special education performance issues, $7 million for CCEE to provide statewide assistance, and $4 million for selected COEs to serve as regional support leads.

Allocates $1.8 Billion for One‑Time Discretionary Grants. The Governor’s budget includes $1.8 billion for K‑12 discretionary grants. Similar to previous years, funds would be allocated to school districts, COEs, and charter schools on a per‑student basis. The $1.8 billion equates to about $300 per student. From each school district’s discretionary grant amount, the Governor proposes to deduct any outstanding obligations resulting from a settlement agreement over Medi‑Cal billing practices (see the nearby box). The remainder of each district’s discretionary grant amount would be attributed to any outstanding mandate claims. About one‑third of districts have such claims.

Medi‑Cal Billing Settlement

School Districts Are Eligible for Certain Medi‑Cal Reimbursements. Since the mid‑1990s, school districts in California have been eligible to receive a 50 percent federal reimbursement for the cost of administrative activities they perform in support of the Medi‑Cal program. Qualifying activities include outreach and referrals, facilitating Medi‑Cal applications, and arranging transportation to Medi‑Cal service providers. The California Department of Health Care Services (DHCS) administers these reimbursements in association with consortia of local education agencies and other entities.

One‑Time Discretionary Grants Reduced to Pay for Medi‑Cal Billing Settlement. In 2013, the federal government completed a review of the reimbursement program and concluded districts were submitting inflated claims. The DHCS agreed to implement a new reimbursement methodology starting in January 2015. It also agreed to use the claims data collected under the new methodology to adjust previously submitted claims from 2009‑10 through 2014. Any difference between a district’s original claims and the adjusted amounts are to be repaid to the federal government. Developing the procedures for this adjustment and collecting the necessary claims data has taken several years. The Governor’s budget estimates the associated statewide obligation is $222 million. To retire the obligation, the Governor proposes to deduct each district’s individual obligation from its one‑time discretionary grant allocation.

Funds Two One‑Time Initiatives Focused on Special Education Staffing Challenges. The budget funds two initiatives ($50 million each) to improve the recruitment and retention of special education teachers. The first initiative would fund teacher residency programs that pair new special education teachers with experienced mentor teachers. The second initiative would provide grants for locally developed efforts to address special education staffing challenges. The CTC would administer both initiatives as competitive grants.

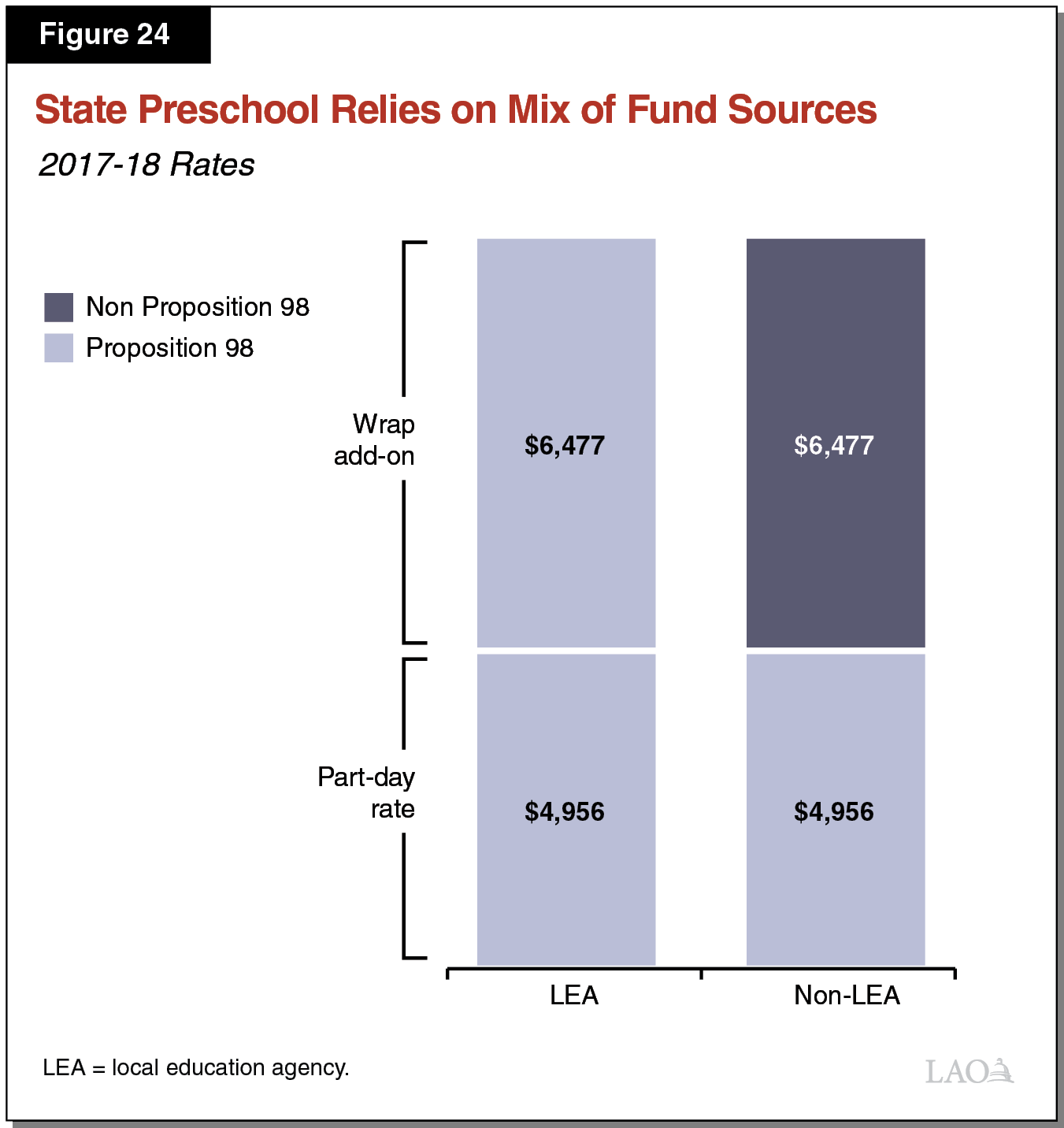

Preschool

Funds Additional Rate and Slot Increases Consistent With Multiyear Budget Agreement. The Governor’s budget includes $32 million Proposition 98 (and an additional $16 million non‑Proposition 98 General Fund) for a 2.8 percent rate increase. It also provides $8 million for an additional 2,959 full‑day State Preschool slots at school districts and COEs starting April 1, 2019. These increases represent the final augmentations associated with a multiyear child care and preschool budget agreement made by the Legislature and the Governor in 2016‑17. In addition, the budget allocates $28 million in Proposition 98 funding (and $22 million non‑Proposition 98 General Fund) to provide a statutory 2.51 percent COLA for certain preschool and child care programs.

Provides One‑Time Funding for Early Education Expansion. The Governor’s budget provides $125 million in Proposition 98 funding (and $42 million from the federal Temporary Assistance for Needy Families program) for a competitive grant to increase the availability of mainstream early education opportunities for children with disabilities from birth through age 5. The one‑time grant, open to school districts as well as other providers, could be used for a variety of purposes, including staff training and facility renovations.

Comments

Split Between Ongoing and One‑Time Initiatives Is Reasonable. We recommend the Legislature adopt a final budget plan that continues to rely upon a mix of ongoing and one‑time spending. The state has taken such an approach the past several years. Setting aside some funds for one‑time purposes helps the state avoid overcommitting to programs it might be unable to sustain during tighter fiscal times. If school funding were to drop in 2019‑20, the expiration of one‑time initiatives would provide a buffer mitigating reductions to ongoing programs such as LCFF and community college apportionments.

Governor Has Reasonable Set of Priorities, but Some Proposals Are Not Well Targeted. Many of the Governor’s proposals relate to issues of longstanding interest to the Legislature, including implementing LCFF, expanding CTE, improving support for low‑performing districts, addressing special education staffing challenges, and expanding early education. Many of the Governor’s proposals, however, would not address the root problems in the areas. For example, special education teacher shortages stem from several longstanding issues, ranging from a lack of pay differentials to overly restrictive education and credentialing requirements. One‑time grants for a specific type of teacher training program or discretionary local solutions are unlikely to resolve these issues. In response to many of the Governor’s proposals, we offer the Legislature alternatives designed to address root issues. In many cases, these alternatives can be structured to cost less than the funding levels proposed by the Governor.

K‑12 Discretionary Grants Continue an Inefficient Approach to Retiring the Mandate Backlog. We are concerned that the Governor’s per‑student funding approach likely will never eliminate the mandate backlog. With two‑thirds of districts having no claims, the bulk of the $1.8 billion included in the Governor’s budget would have no effect on the backlog. We estimate that the state would need to provide around $200 billion to eliminate the backlog using the Governor’s approach. Moreover, the remaining backlog does not reflect the average district’s claiming practices, but those of an increasingly small number of exceedingly high claimers. As an alternative to the Governor’s approach, we recommend the Legislature identify an amount equal to or in excess of the remaining backlog and distribute funds on a per‑student basis, but require districts receiving funds to write off all remaining claims. This approach would make substantially more progress toward eliminating the backlog without rewarding districts that have unusually costly claims.

Minimum Guarantee

Below, we provide background on the Proposition 98 minimum guarantee. We then explain the major drivers underlying the administration’s estimates of the minimum guarantee and discuss a few other adjustments that free‑up Proposition 98 funding. We conclude by offering high‑level comments about the calculation of the guarantee.

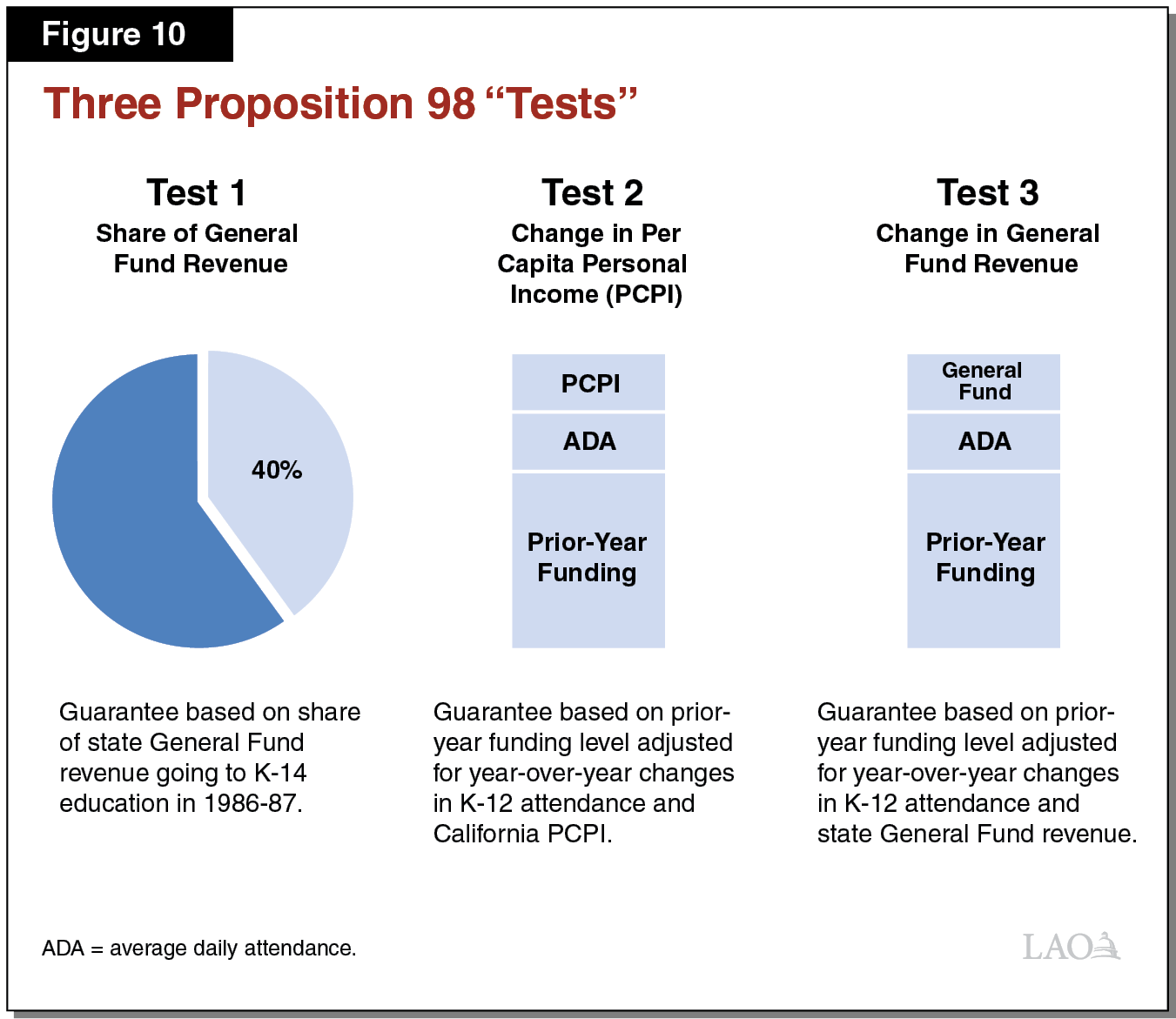

Background on Calculating Minimum Guarantee

Minimum Guarantee Calculation Depends on Various Inputs and Formulas. The Constitution sets forth three main tests for calculating the minimum guarantee. These tests depend upon several inputs, including K‑12 average daily attendance, per capita personal income, and per capita General Fund revenue (see Figure 10). Depending on these inputs, one of these tests will be “operative” and determine the minimum guarantee for that year. In most years, Test 2 or Test 3 is operative and the guarantee builds upon the level of funding provided the previous year. The state meets the guarantee through a combination of General Fund and local property tax revenue, with increases in property tax revenue usually reducing General Fund costs dollar for dollar. Although the state can provide more funding than required, in practice it usually funds at the guarantee. With a two‑thirds vote of each house of the Legislature, the state can suspend the guarantee and provide less funding than the formulas require that year.

“Maintenance Factor” Payments Required in Certain Years. In addition to the three main tests, the Constitution requires the state to track an obligation known as maintenance factor. The state creates a maintenance factor obligation when Test 3 is operative or when it suspends the guarantee. The obligation equals the difference between the actual level of funding provided and the Test 1 or Test 2 level (generally whichever is higher). Moving forward, the state tracks and adjusts the maintenance factor obligation each year for changes in K‑12 attendance and per capita personal income. In subsequent years, when General Fund revenue is growing relatively quickly, the Constitution requires the state to make maintenance factor payments until it has paid off the obligation. The magnitude of these payments is determined by formula, with stronger revenue growth generally requiring larger payments.

Estimates of the Guarantee Can Change After the Adoption of the Budget. The state does not finalize the minimum guarantee until the fiscal year is over. When the state updates the relevant inputs, the guarantee can change from the level initially assumed in the budget act. If the revised guarantee exceeds the initial estimate, the state makes a one‑time payment to “settle up” the difference for that year and uses the higher base for calculating the guarantee the following year. If the revised guarantee is below the initial estimate, the state can allow funding to remain at the higher level or make midyear adjustments to reduce funding to the lower guarantee. Typically, the state makes downward midyear adjustments, as the decision affects the ongoing level of the minimum guarantee moving forward.

Governor’s Estimates Of the Guarantee

2016‑17 Guarantee Down Slightly but Proposition 98 Funding Level Unchanged. Compared with estimates made in June 2017, the 2016‑17 minimum guarantee has dropped $63 million due to slightly lower estimates of K‑12 attendance and General Fund revenue. Despite this decrease, the Governor proposes to maintain Proposition 98 funding at $71.4 billion—the same level the state approved in the June budget plan. This proposed funding level is $542 million more than required to meet the revised estimate of the minimum guarantee. The budget also recognizes various minor adjustments—primarily lower LCFF costs—that reduce funding by $43 million. To offset these reductions and maintain funding at $71.4 billion, the Governor proposes to count $43 million of the funds associated with the K‑12 discretionary grants toward 2016‑17.

2017‑18 Guarantee Up $687 Million From Budget Act Estimates. The administration’s revised estimate of the 2017‑18 guarantee is $75.2 billion, an increase of $687 million compared with the June budget plan. This increase is mainly the result of an increase in General Fund tax revenue. This faster revenue growth requires the state to make an additional maintenance factor payment of $636 million (on top of the $536 million payment already included in the June budget plan). After making the $1.2 billion total maintenance factor payment, the state’s outstanding maintenance factor obligation at the end of 2017‑18 would be $228 million. The rest of the increase in the guarantee is attributable to a small increase in attendance. Whereas the June budget plan assumed 2017‑18 attendance would decline by 2,900 students (a 0.05 percent decline), the Governor’s budget estimates that attendance will grow by 1,200 students (a 0.02 percent increase).

2018‑19 Guarantee Up $3.1 Billion Over Revised 2017‑18 Level. The administration estimates that the 2018‑19 guarantee is $78.3 billion, an increase of 4.1 percent over the revised 2017‑18 level (see Figure 11). Test 3 is operative, with the increase in the guarantee attributable to growth in state General Fund revenue. The administration also estimates that K‑12 attendance will decline by 0.3 percent. Although the minimum guarantee usually is adjusted for changes in attendance, the Constitution contains a two‑year hold harmless provision that deems any decline in attendance to be zero unless attendance also declined during the two preceding years. Data from CDE show that attendance declined each year from 2014‑15 through 2016‑17. The administration’s estimate of a small attendance increase in 2017‑18, however, restarts the hold harmless provision and prevents any downward adjustment to the 2018‑19 guarantee. The administration also estimates that the state creates a new $83 million maintenance factor obligation in 2018‑19. This additional maintenance factor brings the state’s total outstanding obligation to $320 million by the end of 2018‑19.

Figure 11

Proposition 98 Key Inputs and Outcomes Under Governor’s Budget

(Dollars in Millions)

|

2016‑17 |

2017‑18 |

2018‑19 |

|

|

Minimum Guarantee |

|||

|

General Fund |

$49,993a |

$52,741 |

$54,564 |

|

Local property tax |

21,397 |

22,470 |

23,761 |

|

Totals |

$71,390 |

$75,211 |

$78,324 |

|

Change From Prior Year |

|||

|

General Fund |

$568 |

$2,747 |

$1,823 |

|

Percent change |

1.1% |

5.5% |

3.5% |

|

Local property tax |

$1,718 |

$1,074 |

$1,291 |

|

Percent change |

8.7% |

5.0% |

5.7% |

|

Total funding |

$2,287 |

$3,821 |

$3,114 |

|

Percent change |

3.3% |

5.4% |

4.1% |

|

Operative Test |

3 |

2 |

3 |

|

Maintenance Factor |

|||

|

Amount created (+) or paid (‑) |

$1,279 |

‑$1,172 |

$83 |

|

Total outstandingb |

1,350 |

228 |

320 |

|

Growth Rates |

|||

|

K‑12 average daily attendance |

‑0.2% |

0.02% |

‑0.3%c |

|

Per capita personal income (Test 2) |

5.4 |

3.7 |

4.3 |

|

Per capita General Fund (Test 3)d |

2.7 |

6.0 |

4.1 |

|

aIncludes General Fund provided on top of the minimum guarantee. bOutstanding maintenance factor is adjusted annually for changes in K‑12 attendance and per capita personal income. cUnder the two‑year hold harmless provision in the State Constitution, the 2018‑19 guarantee is calculated as though attendance is flat in 2018‑19. dAs set forth in the State Constitution, reflects change in per capita General Fund plus 0.5 percent. |

|||

Higher Local Property Tax Revenue Over the Period Reduces General Fund Cost Pressure. For 2016‑17, the administration revises its property tax estimate upward by $495 million to reflect updated data reported by county auditor‑controllers. For 2017‑18, the administration revises its property tax estimate upward by $578 million. The bulk of this increase reflects the prior‑year increase carrying forward. The administration also assumes assessed property values will grow slightly faster than 2017‑18 Budget Act estimates (rising 6 percent rather than the earlier estimate of 5.3 percent). For both 2016‑17 and 2017‑18, the upward revisions result in a dollar‑for‑dollar reduction in General Fund spending. For 2018‑19, the administration estimates property tax revenue will increase $1.3 billion from the revised 2017‑18 level (see Figure 11). This increase mainly reflects a 5.6 percent increase in assessed property values. The higher property tax revenue in 2018‑19 covers about 40 percent of the estimated increase in the minimum guarantee that year.

Additional Proposition 98‑Related Funding

Budget Includes $2.5 Billion in Additional One‑Time Funding. Separate from the increases in the 2017‑18 and 2018‑19 minimum guarantees, the Governor’s budget contains $2.5 billion in Proposition 98 funding attributable to other adjustments. The largest of these adjustments is the expiration of $2.2 billion in one‑time initiatives funded in 2017‑18, with the associated funding repurposed for new commitments in 2018‑19. In addition, the budget identifies and repurposes $214 million in unspent funds associated with previous years (primarily 2015‑16 and 2016‑17). The Governor also proposes to make a $100 million settle‑up payment related to meeting the 2009‑10 guarantee (scored as a Proposition 2 debt payment). This payment would reduce the state’s outstanding settle‑up obligation to $340 million. Finally, the budget recognizes various technical adjustments (primarily lower‑than‑expected costs for community college apportionments) that free up a net total of $37 million. The $2.5 billion associated with all these adjustments, combined with the $687 million increase in the 2017‑18 guarantee and $3.1 billion increase in the 2018‑19 guarantee, accounts for the $6.3 billion total spending included in the Governor’s Proposition 98 package.

Comments

2017‑18 Attendance Assumptions Have Significant Implications. The administration’s assumption of attendance growth in 2017‑18 is a significant development because it restarts the hold harmless provision and prevents a $230 million decline in the 2018‑19 guarantee that otherwise would occur. Under our November outlook, we projected that attendance would decline even faster than the administration assumes in 2018‑19, with the potential associated reduction in the guarantee equating to more than $400 million. We recommend the Legislature carefully scrutinize preliminary 2017‑18 attendance data—likely available in March—to determine whether growth is likely to materialize in 2017‑18. If growth does not materialize, the 2018‑19 guarantee could be several hundred million dollars below the level the administration currently assumes. The assumption about growth in 2017‑18 also has significant implications for estimates of the 2019‑20 guarantee, given that the hold harmless provision applies for two years and both our office and the administration assume attendance declines in 2019‑20.

Administration’s Property Tax Estimates Appear Reasonable. The administration’s property tax estimates for 2016‑17 generally reflect the latest available data and are likely close to the final amounts for the year. For 2017‑18 and 2018‑19, the administration’s estimated growth in assessed property values seems consistent with the continued strength of the state’s real estate market. Over the three‑year period, the administration’s estimates are $248 million above our November 2017 estimates, though this difference amounts to less than 0.4 percent of all property tax revenue collected during the period.

Further Upward Revisions to General Fund Revenue Unlikely to Increase Minimum Guarantee Significantly. In most years, increases in General Fund revenue lead to increases in the Proposition 98 minimum guarantee. These increases often reflect higher required Proposition 98 maintenance factor payments. The Governor’s budget, however, already assumes the state pays off most of its maintenance factor obligation by the end of 2017‑18. The Governor’s budget also assumes the guarantee is already growing at the same rate as per capita personal income in 2017‑18 and only slightly below this rate in 2018‑19. Under these conditions, increases in General Fund revenue tend to have only modest effects on the minimum guarantee. Given these factors, we estimate the 2017‑18 and 2018‑19 guarantees likely would not increase more than a few hundred million dollars even if revenues increased several billion dollars from the Governor’s January budget level.

Local Control Funding Formula

In this section, we focus on LCFF. The section has three parts. We first look at issues relating to the full implementation of LCFF. We then present data on how high‑poverty and low‑poverty schools have spent their LCFF funding increases in recent years. We end by discussing several options for allocating any Proposition 98 funding above the full implementation cost of LCFF.

Full Implementation

Below, we provide background on LCFF and analyze the Governor’s proposal to fully fund the formula in 2018‑19.

Background

State Enacted New School Funding Formula in 2013‑14. Five years ago, the state enacted major changes to the way it funds school districts and charter schools. Previously, the state allocated school funding through a combination of general purpose grants (called “revenue limits”) and more than 40 state categorical programs. Districts could use general purpose grants for any educational purpose but had to spend categorical funding on state‑prescribed activities. In 2013‑14, the state eliminated most categorical programs, replacing all the previous program‑specific funding formulas with one new formula.

LCFF Formula Has a Per‑Student Base Grant. The largest component of LCFF (accounting for about 80 percent of the formula’s total cost) is a base grant generated by each student. Base rates vary across four grade spans, with students in higher grades generally generating more funding than those in lower grades. In establishing the base rate for high school, the state built in an amount to recognize the shift of responsibility for career technical education from regional entities to school districts. In establishing the K‑3 base grant, the state built in an amount to recognize the desire for smaller class sizes in the early grades. In setting the initial target base rates for each grade span, the state increased funding over existing average levels by about $500 per student.

Formula Allocates Additional Funding for English Learners and Low‑Income (EL/LI) Students. In addition to the base grant, districts receive funding for serving EL/LI students. Under LCFF rules, a student who is only EL or only LI generates the same amount of funding as a student who is both EL and LI. For each EL/LI student, a district receives a supplemental grant equal to 20 percent of the base grant. This funding largely is intended to address the individual challenges EL/LI students face—for example, needing to learn English or having access to few learning materials at home. Districts serving a student population more than 55 percent EL/LI also receive a concentration grant funding equal to 50 percent of the base grant for each EL/LI student above the 55 percent threshold. This funding largely is intended to address broader challenges affecting higher‑poverty communities.

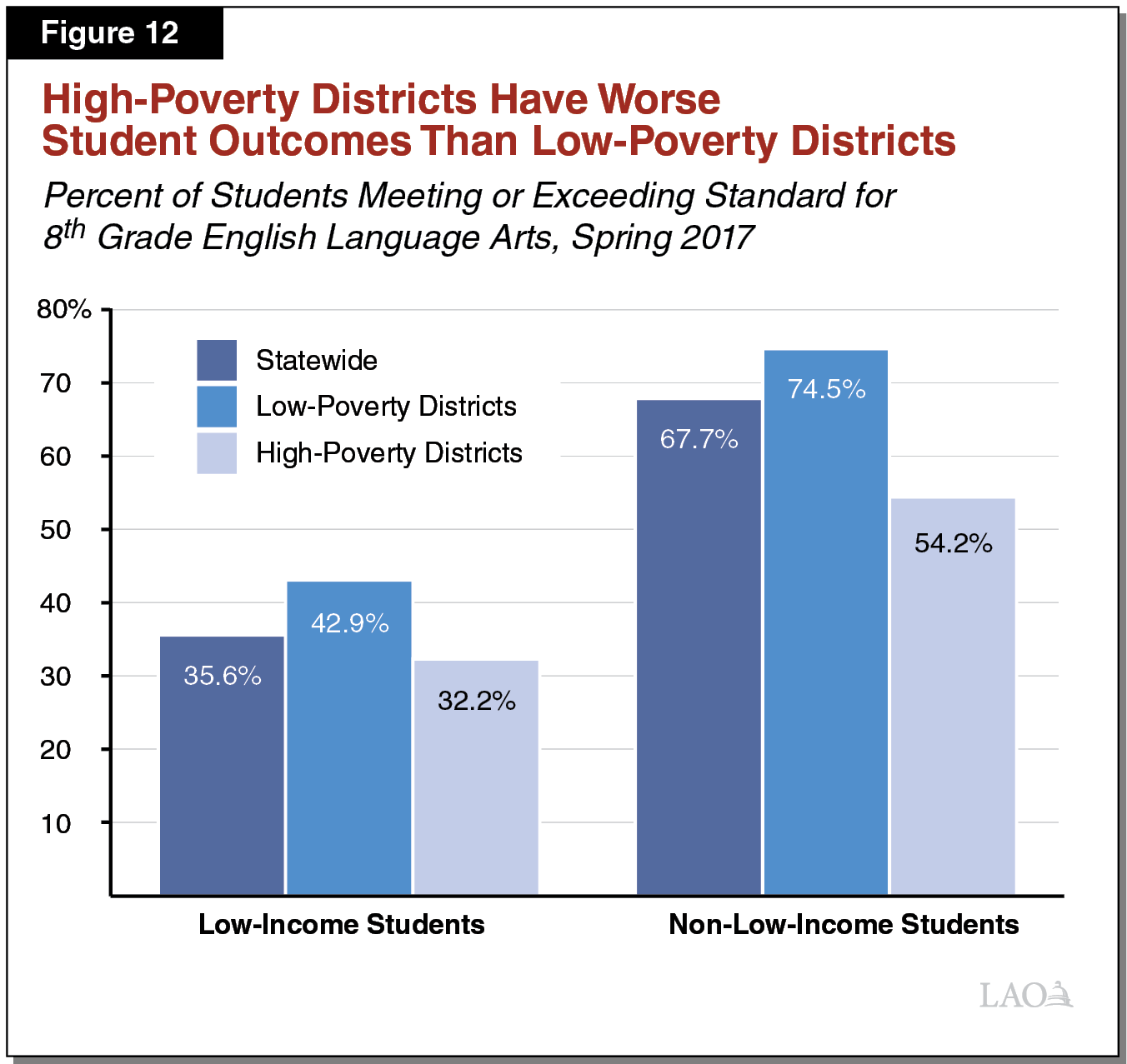

Both Individual and Community Factors Contribute to Achievement Gap. Figure 12 shows how both individual‑ and district‑level challenges contribute to the achievement gap. Although low‑income students perform worse than non‑low‑income students regardless of which districts they attend, both student groups in high‑poverty districts perform notably worse than peers in low‑poverty districts. (Throughout this section, we define high‑poverty districts as those serving more than 80 percent EL/LI students, and low‑poverty districts as those serving less than 50 percent EL/LI students. To isolate the effects of LCFF in our later analysis, we also exclude basic aid districts.) The relatively poor performance of high‑poverty districts widens the statewide achievement gap because low‑income students are disproportionately likely to attend such districts. An important caveat is that the state’s method for identifying low‑income students is broad and includes students of varied backgrounds. Low‑income students attending high‑poverty districts may face more individual‑level challenges than their peers attending low‑poverty districts. The same could be true for the non‑low‑income students attending these districts.

An Illustration of Two Districts’ LCFF Calculations. Figure 13 shows the LCFF calculation for two equally sized elementary school districts. Both districts serve the same number of students in each of the K‑3 and 4‑6 grade spans, so they generate the same amount of base funding. District A serves a notably higher share of EL/LI students than District B (91 percent compared to 50 percent) and thus generates more supplemental funding. District A also has a student population that is more than 55 percent EL/LI and thus generates concentration funding. Given these differences in student demographics, District A receives a total of $449,000 more than District B—$2,041 (24 percent) more per student.

Figure 13

Illustration of LCFF Calculation for Two Elementary Districts

Underlying Funding Rates Based on 2018‑19 Governor’s Budget

|

District A |

District B |

Difference |

|||

|

District Characteristics |

|||||

|

Grade K‑3 attendance |

100 students |

100 students |

— |

||

|

Grade 4‑6 attendance |

120 students |

120 students |

— |

||

|

EL/LI percentagea |

91% |

50% |

41% |

||

|

LCFF Funding |

|||||

|

Base funding |

$1,712,000 |

$1,712,000 |

— |

||

|

Supplemental funding |

312,000 |

171,000 |

$141,000 |

||

|

Concentration funding |

308,000 |

— |

308,000 |

||

|

Totals |

$2,332,000 |

$1,883,000 |

$449,000 |

||

|

aEL/LI students as a share of total enrollment. LCFF = Local Control Funding Formula and EL/LI = English learner/low‑income students. |

|||||

Regulations Restrict the Use of EL/LI Funding. State law directed SBE to develop specific regulations guiding the use of supplemental and concentration grant funding. These regulations require districts to use these funds for the benefit of EL/LI students. Districts could use the funds for supplemental services, such as counseling or after school programs for these populations. They also could use these funds on districtwide purposes (including across‑the‑board teacher salary increases) if they can document how these districtwide expenditures will benefit their EL/LI students. State law requires each district and charter school to document their use of supplemental and concentration grant funding in their LCAPs, which are reviewed by COEs to ensure the plans comply with state spending restrictions.

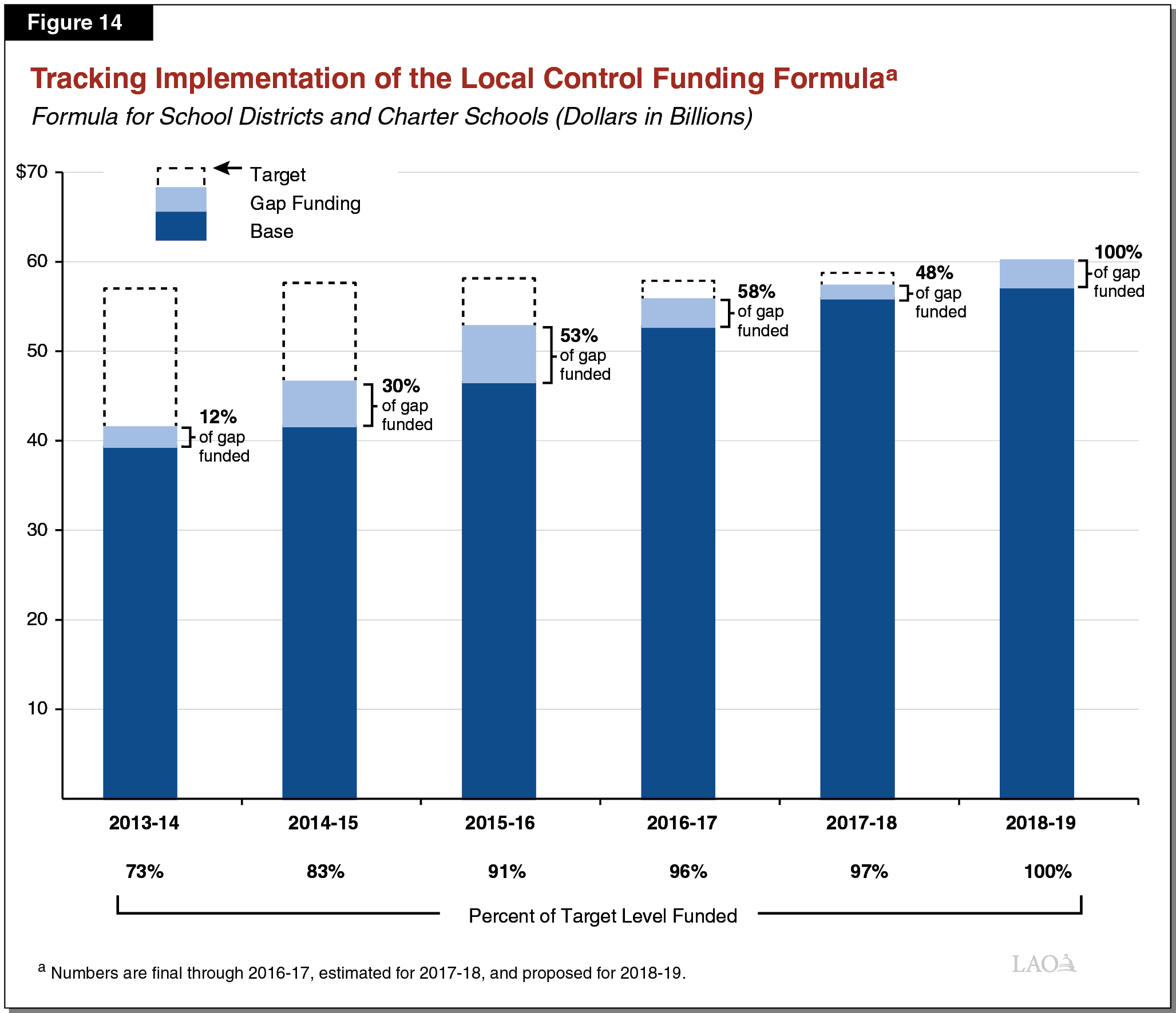

Full Implementation Was Expected to Take Several Years. Given the higher target funding rates under LCFF compared to the state’s former school funding system, full LCFF implementation initially was estimated to cost $18 billion more than the previous system. Starting in 2013‑14, the state augmented LCFF funding to close the difference (or gap) between prior‑year funding levels and the formula’s full implementation cost. Based on projections of growth in Proposition 98 funding, the administration estimated the state would reach full LCFF implementation in 2020‑21. Over the past five years, the state has provided $17.1 billion towards implementing the formula. As Figure 14 shows, LCFF was 73 percent‑funded in 2013‑14 and is 97 percent‑funded in 2017‑18.

Governor’s Proposal

Fully Implements LCFF. The Governor proposes a $2.9 billion (5.4 percent) augmentation in 2018‑19—bringing total LCFF funding to $60.3 billion. Of the $2.9 billion augmentation, we estimate $1.2 billion is necessary to cover a 2.51 percent COLA to the formula’s target rates. The remaining $1.7 billion covers 100 percent of the “gap” between last year’s funding level and the formula’s full implementation cost.

Proposes Addendum to District Budgets. The administration indicates it would like districts to improve how they show alignment between their budgets and their LCAP goals. Specifically, the administration proposes trailer bill language directing SBE to design a template for an addendum to district budgets. Districts would need to begin using the template starting in 2019‑20.

Assessment

Prioritizing LCFF Implementation Consistent With State’s Prior‑Year Actions. The Governor’s plan to dedicate most new ongoing K‑12 funding to LCFF implementation is consistent with the Legislature’s approach over the past five years. By continuing to prioritize LCFF implementation, both the Governor and the Legislature would be fostering greater local control and flexibility while simultaneously providing more funding for disadvantaged students.

Proposed Budget Addendum Adds Work but Little Value. State law already requires districts to align their budgets with their LCAP goals, and districts’ LCAPs already document how these goals are linked to specific expenditures. Although we agree with the administration that current LCAPs are difficult for most parents to digest, this is primarily because of their length (often running over 100 pages) and complexity. Adding an addendum to district budgets—another long and complex document—seems counterproductive. Consequently, we recommend the Legislature reject the Governor’s proposal and focus instead on simplifying LCAPs.

At Full Implementation, Districts Are Required to Show How All EL/LI Funds Benefit EL/LI Students. Prior to full implementation, regulations do not require districts to spend their entire supplemental and concentration grant allotments on EL/LI services. Rather, the regulations require districts to spend a growing portion of this funding on EL/LI services. At full implementation, the regulations no longer focus on incremental increases but on districts’ entire EL/LI allotments. Some school districts have expressed concern that at full implementation they will need to make major budget adjustments to ensure they are meeting the higher spending requirement.

At Full Implementation, Districts Unlikely to Have to Change EL/LI Spending Significantly. To evaluate these concerns, we reviewed approximately 100 LCAPs for the 2016‑17 school year. Specifically, for each LCAP, we identified the amount the district reported spending for EL/LI students. Although current regulations allow districts to spend less than their total EL/LI allotment on supplemental services, we found the average district already spent 84 percent of its entire supplemental and concentration grants on such services. To reach 100 percent at full implementation, districts statewide would have to increase spending on EL/LI students by about $1.5 billion over two years—2017‑18 and 2018‑19. This is a notable but seemingly manageable increase, as districts increased spending on these students by about $6 billion from 2013‑14 through 2016‑17—or about $1.5 billion per year.

Going Forward, Legislature Has Many Options for Allocating Additional Funding. In recent years, the Legislature has dedicated most new Proposition 98 funding to implementing LCFF. In 2018‑19, the Legislature has about $1 billion in new Proposition 98 funding above the cost of fully implementing LCFF. In some future years, the state likely will face a similar scenario, with growth in Proposition 98 funding outpacing growth in LCFF costs. In allocating additional funds, the Legislature will have many options to weigh. In the remaining two parts of this section, we provide context to inform these decisions—first providing a high‑level review of how LCFF affected school spending the past few years and then discussing various options for allocating additional funding moving forward.

A Look Back: School Spending Decisions

Legislators and advocates both have expressed interest in understanding how schools have spent the billions of dollars in new funding they have received under LCFF. In particular, many have asked to what extent the supplemental and concentration dollars generated by EL/LI students have been spent on supplemental services versus across‑the‑board increases in teacher salaries. Relatedly, many have asked whether and to what extent LCFF has helped close the achievement gap between EL/LI and non‑EL/LI students. Below, we address these questions by providing a high‑level comparison of how LCFF funding increases were spent by low‑poverty and high‑poverty districts and tracking the achievement gap over the past few years.

Findings

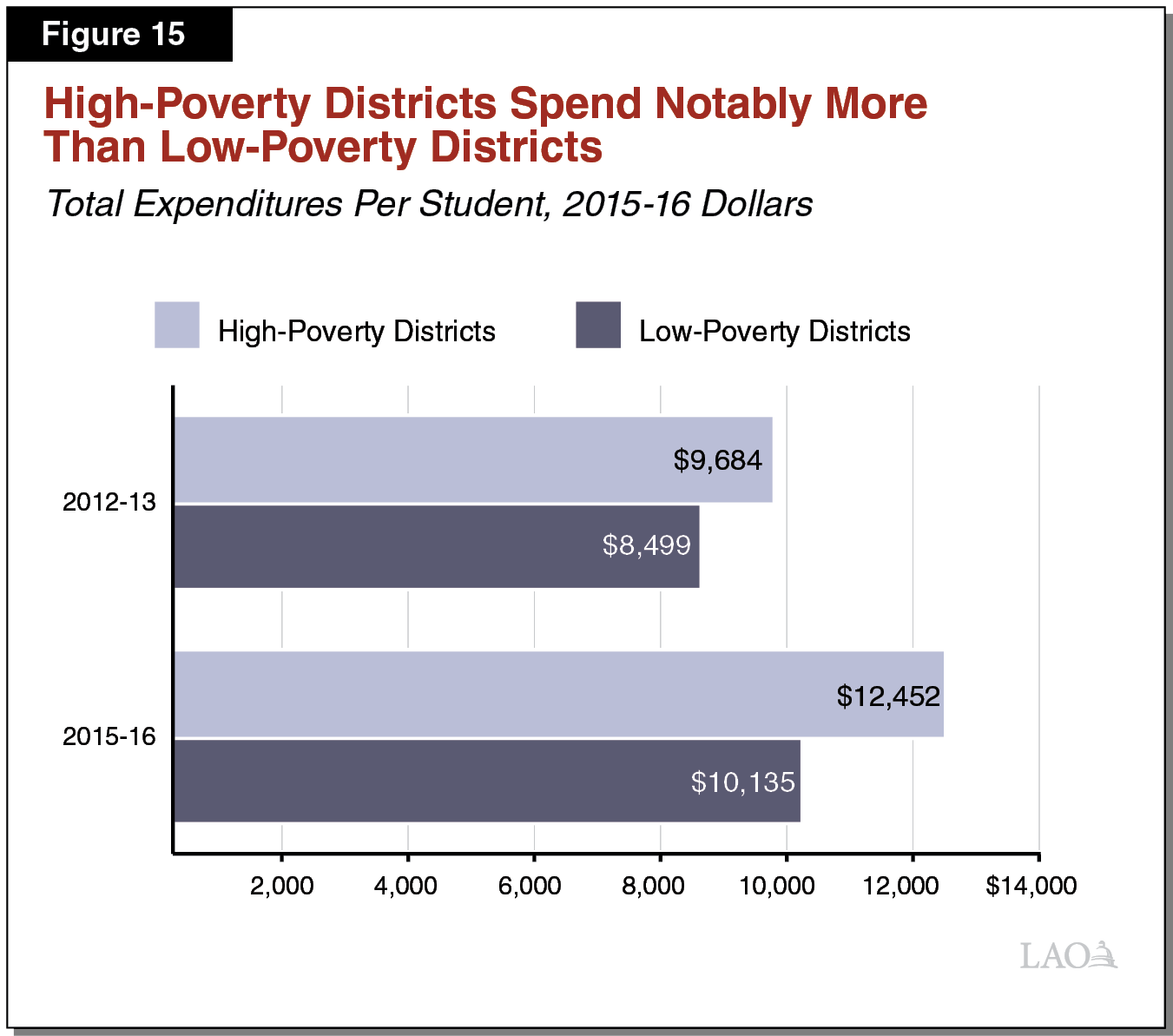

High‑Poverty Districts Have Seen Particularly Large Revenue Increases Since LCFF Was Enacted. Figure 15 compares the inflation‑adjusted, per‑student expenditures for low‑poverty and high‑poverty districts in 2012‑13 and 2015‑16, the most recent year for which LCFF expenditure data are available. Even before LCFF, high‑poverty districts spent on average 14 percent more than low‑poverty districts, primarily because they received state and federal categorical funding for serving EL/LI students. The LCFF directed even more state funding for EL/LI students such that, in 2015‑16, high‑poverty districts spent on average 23 percent more than low‑poverty districts.

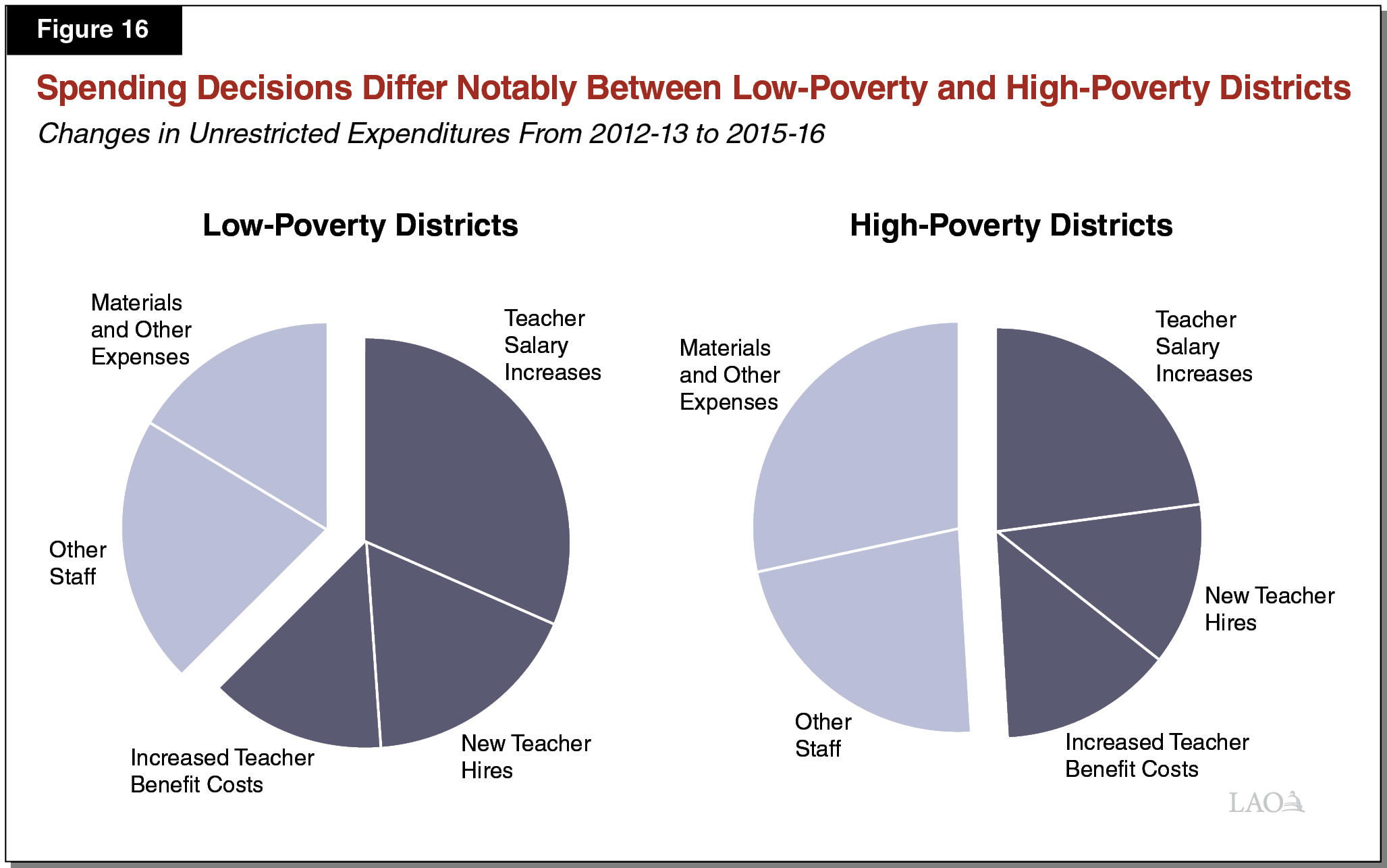

Spending Decisions Differ Notably Between Low‑Poverty and High‑Poverty Districts. Figure 16 shows how low‑poverty and high‑poverty districts spent their LCFF funding increases. Notably, whereas low‑poverty districts spent 63 percent of their increased funding on teachers, high‑poverty districts spent 49 percent of their increased funding on teachers. Low‑poverty districts also spent a notably smaller share of their funding increases on materials and other expenses (16 percent) than high‑poverty districts (28 percent).

LCAPs Indicate EL/LI Funding Primarily Funds Supplemental Services. The statewide expenditure data discussed above suggest high‑poverty districts have in many cases used supplemental and concentration grant funding for targeted EL/LI services rather than teacher salaries. Our review of the approximately 100 district LCAPs supports this finding. We found most LCAPs detailed using supplemental and concentration grant funding to purchase instructional materials for English learners, provide additional student support staff (such as counselors) for high‑poverty schools, and develop professional development for teachers serving EL/LI students, among similar uses.

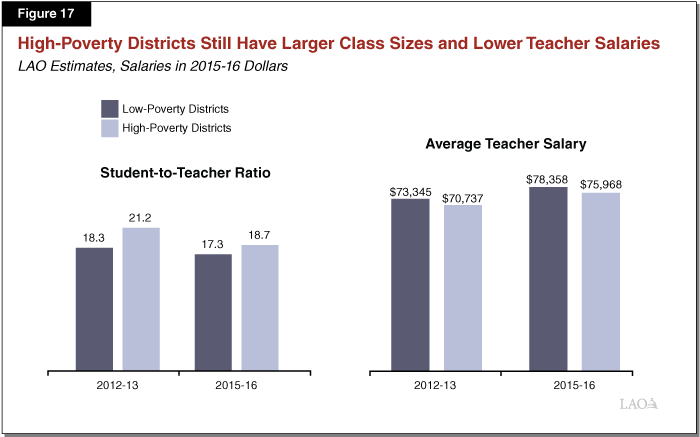

High‑Poverty Districts Continue to Have Larger Classes, Pay Lower Teacher Salaries. Despite having long received more funding per student than low‑poverty districts, high‑poverty districts traditionally have had both larger class sizes and less competitive teacher pay. Figure 17 shows these gaps persist despite the large funding increases high‑poverty districts have received under LCFF. The gaps, however, have narrowed somewhat. Though the student‑to‑teacher ratio declined for both groups of districts from 2012‑13 to 2015‑16, the percentage decline was greater for high‑poverty districts (12 percent) than low‑poverty districts (5 percent). Similarly, the average teacher salary increased for both groups of districts, but the percentage increase was slightly greater for high‑poverty districts (7.4 percent) than low‑poverty districts (6.8 percent).

Achievement Gap Persists Under First Few Years of LCFF. Despite relatively large funding increases for high‑poverty districts, EL/LI students continue to trail their non‑EL/LI peers on statewide assessments. For example, 36 percent of low‑income students met or exceeded state standards in eighth grade English language arts in 2017, compared with 68 percent of non‑low‑income students. The gaps are similar at other grade levels, for math, and also between English learners and non‑English learners. Achievement gaps have remained largely unchanged since the current statewide assessments were introduced in 2015‑16. California’s achievement gap between low‑income and non‑low‑income students also remained largely unchanged on the National Assessment of Educational Progress between 2012‑13 and 2015‑16.

A Look Ahead: Future Funding Decisions