LAO Contacts

- State Prisons, County Jails, Sentencing

- Correctional Health Care, Rehabilitation Programs, State Hospitals, Community Corrections

- Managing Principal Analyst, Criminal Justice

March 1, 2017

The 2017-18 Budget

California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation

Overview

The California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR) is responsible for the incarceration of adult felons, including the provision of training, education, and health care services. As of January 18, 2017, CDCR housed about 129,000 adult inmates in the state’s prison system. Most of these inmates are housed in the state’s 35 prisons and 43 conservation camps. About 9,000 inmates are housed in either in-state or out-of-state contracted prisons. The department also supervises and treats about 44,000 adult parolees and is responsible for the apprehension of those parolees who commit new offenses or parole violations. In addition, 670 juvenile offenders are housed in facilities operated by CDCR’s Division of Juvenile Justice, which includes three facilities and one conservation camp.

Spending Proposed to Increase by $359 Million in 2017‑18. The Governor’s budget proposes total expenditures of $11.3 billion ($11 billion General Fund) for CDCR operations in 2017‑18. Figure 1 shows the total operating expenditures estimated in the Governor’s budget for the past and current years and proposed for the budget year. As the figure indicates, the proposed spending level is an increase of $359 million, or about 3 percent, from the estimated 2016‑17 spending level. This increase reflects higher costs related to (1) a proposed shift of responsibility for operating inpatient psychiatric programs in prisons from the Department of State Hospitals (DSH) to CDCR, (2) debt service payments for construction projects, and (3) a proposed reactivation of housing units that were temporarily deactivated due to inmate housing unit transfers made pursuant to the Ashker v. Brown settlement. This additional proposed spending is partially offset by various spending reductions, including reduced spending for contract beds.

Figure 1

Total Expenditures for the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation

(Dollars in Millions)

|

2015-16 Actual |

2016-17 Estimated |

2017-18 Proposed |

Change From 2016-17 |

||

|

Amount |

Percent |

||||

|

Prisons |

$9,118 |

$9,631 |

$9,959 |

$328 |

3% |

|

Adult parole |

534 |

575 |

584 |

9 |

2 |

|

Administration |

451 |

465 |

483 |

18 |

4 |

|

Juvenile institutions |

177 |

193 |

198 |

5 |

3 |

|

Board of Parole Hearings |

40 |

49 |

47 |

-2 |

-3 |

|

Totals |

$10,321 |

$10,913 |

$11,272 |

$359 |

3% |

Trends in the Adult Inmate and Parolee Populations

LAO Bottom Line. We withhold recommendation on the administration’s adult population funding request until the May Revision.

Background

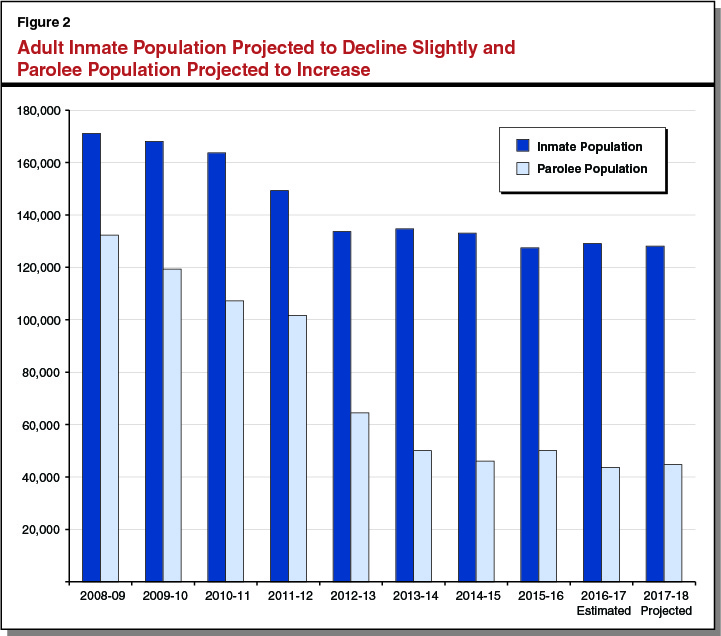

As shown in Figure 2, the average daily inmate population is projected to be 128,200 inmates in 2017‑18, a decrease of about 900 inmates (1 percent) from the estimated current-year level. Also shown in Figure 2, the average daily parolee population is projected to be 44,800 in 2017‑18, an increase of about 1,100 parolees (2 percent) from the estimated current-year level. The projected decrease in the inmate population and increase in the parolee population is primarily due to the estimated impact of Proposition 57 (2016), which makes nonviolent offenders eligible for parole consideration and expands CDCR’s authority to reduce inmates’ prison terms through credits.

Governor’s Proposal

As part of the Governor’s January budget proposal each year, the administration requests modifications to CDCR’s budget based on projected changes in the prison and parole populations in the current and budget years. The administration then adjusts these requests each spring as part of the May Revision based on updated projections of these populations. The adjustments are made both on the overall population of offenders and various subpopulations (such as inmates housed in contract facilities and sex offenders on parole).

The administration proposes a net decrease of $43.5 million in the current year and a net increase of $12.6 million in the budget year for population-related proposals. The current-year net decrease in costs is primarily due to the transition of certain inmates from security housing units to the general population as a result of the Ashker v. Brown settlement, as well as a projected decline in the department’s use of contract beds. These savings are partially offset by projected increases in spending on medical care and the number of inmates in state-operated prisons. The budget-year net increase in costs is primarily due to projected increases in spending on medical care and the parole population. These increased costs are partially offset by savings from a decrease in the use of contract beds.

LAO Recommendation

We withhold recommendation on the administration’s adult population funding request until the May Revision. We will continue to monitor CDCR’s populations and make recommendations based on the administration’s revised population projections and budget adjustments included in the May Revision.

Inmate Mental Health Programs

LAO Bottom Line. While the Governor’s proposed shift of the responsibility of inpatient psychiatric programs from DSH to CDCR is well intended, there is significant uncertainty regarding the extent to which the shift will actually achieve the desired outcomes. Accordingly, we recommend that the Legislature reject the Governor’s proposal and instead shift a limited number of beds on a pilot basis. Similarly, we also recommend the Legislature approve the Governor’s proposal to convert 74 existing outpatient mental health beds into CDCR-operated Intermediate Care Facility (ICF) beds at the California Medical Facility (CMF) on a limited-term, pilot basis, rather than on an ongoing basis as proposed. In addition, we recommend rejecting the proposals to construct two 50-bed Mental Health Crisis Bed (MHCB) facilities given that various factors could reduce the need for these beds.

Background

Overview of Inmate Mental Health Programs. About one-third of CDCR inmates participate in an in-prison mental health program. The care given to these inmates is subject to the oversight of a Special Master appointed as part of the Coleman v. Brown case. (For more information on the Coleman case, please see the nearby box.) Typically, these inmates can be treated in an outpatient setting, meaning they live in a prison housing unit and receive regular mental health treatment but do not require 24-hour care. However, under certain circumstances, some inmates may require more intensive inpatient treatment. For example, if inmates are suffering from severe symptoms of a serious mental health disorder that cannot be managed by an outpatient program, they are generally sent to MHCBs, which provide short-term housing and 24-hour care for inmates. If the inmate’s condition is stabilized in an MHCB, the inmate is generally sent back to his or her prison housing unit. If the inmate’s condition requires a more intensive level of treatment, the inmate may be admitted to an inpatient psychiatric program. Inpatient psychiatric programs provide intensive 24-hour care with the goal of preparing the inmate to return to an outpatient program. Below, we discuss both MHCBs and inpatient psychiatric programs in greater detail.

Coleman v. Brown

In 1995, a federal court ruled in the case now referred to as Coleman v. Brown that the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR) was not providing constitutionally adequate mental health care to its inmates. As a result, the court appointed a Special Master to monitor and report on CDCR’s progress towards providing an adequate level of mental health care. The Special Master has identified various areas of concern, including whether inmates have access to appropriate levels of mental health treatment, such as inpatient psychiatric care.

MHCBs. Due to their immediate need for treatment, inmates identified as needing MHCBs are supposed to be transferred to these beds within 24 hours. If a bed is not available, alternative accommodations must be found, such as placing the inmate on suicide watch. Under CDCR regulations that have been approved by the Coleman court, inmates are not supposed to stay in MHCBs for more than ten days. Currently, there are 427 MHCBs in the state prison system. The annual cost of operating one of these beds is around $345,000. Due to the limited number of such beds located throughout the state, there is a waitlist for these beds. As of January 2017, there were 70 inmates on the waiting list for an MHCB.

Inpatient Psychiatric Programs. Inpatient psychiatric programs are operated in both state prisons and state hospitals. There are a total of 1,547 inpatient psychiatric beds. There are two levels of inpatient psychiatric programs:

- ICF. ICFs provide longer-term treatment for inmates who require treatment beyond what is provided in CDCR outpatient programs. Inmates with lower security concerns are placed in low-custody ICFs, which are in dorms, while inmates with higher security concerns are placed in high-custody ICFs, which are in cells. There are 784 ICF beds, 700 of which are high-custody ICF beds in state prisons. In addition, there are 306 low-custody ICF beds in state hospitals.

- Acute Psychiatric Programs (APPs). APPs provide shorter-term, intensive treatment for inmates who show signs of a major mental illness or higher level symptoms of a chronic mental illness. Currently, there are 372 APP beds, all of which are in state prisons.

In addition to these beds, there are 85 beds for women and condemned inmates in state prisons that can be operated as either ICF or APP beds, as we discuss below. As of January 2017, there was a waitlist of over 120 inmates for ICF and APP beds.

DSH Inpatient Psychiatric Programs. Almost all inpatient psychiatric programs are operated by DSH. Specifically, DSH operates a total of 1,462 beds in both state prisons and state hospitals—all but the 85 beds for women and condemned inmates. The first inpatient psychiatric program in a state prison opened at CMF in Vacaville in 1988. At the time, the state hospitals, rather than CDCR, were given greater responsibility to provide treatment services to inmates because of their experience operating inpatient psychiatric hospitals. DSH currently operates inpatient psychiatric programs at three state prisons—CMF, California Health Care Facility (CHCF) in Stockton, and Salinas Valley State Prison in Soledad. In these prisons, DSH operates 1,156 ICF and APP beds at an annual cost of around $216,000 per bed. In state hospitals, DSH operates 306 ICF beds for low custody inmates (256 beds at DSH-Atascadero and 50 beds at DSH-Coalinga). We estimate that the annual cost to operate a low-custody ICF bed in a state hospital to be about $218,000.

CDCR Inpatient Psychiatric Programs. In 2012, CDCR began providing inpatient psychiatric programs for certain inmates with the operation of a 45-bed facility for women at the California Institution for Women in Corona. In 2014, CDCR began operating a 40-bed inpatient program for condemned inmates at San Quentin State Prison in Marin County. These programs provide both ICF and APP treatment to inmates housed in cells. In addition to being operated by CDCR instead of DSH, these programs are also different in that they serve specific inmate groups (women and condemned inmates), which could significantly affect program operations and costs. The annual cost for a bed in a CDCR-operated, inpatient psychiatric program is around $301,000.

Inpatient Psychiatric Program Referral Process. When CDCR seeks to place an inmate in a DSH inpatient psychiatric bed, DSH staff must agree with CDCR’s assessment that the inmate needs inpatient care. In addition, both CDCR and DSH must agree on the location the inmate should be served in. Once both departments agree on the placement, the inmate is supposed to be transferred within 72 hours. Under the current referral process, ICF referrals take 15 business days to complete while APP referrals take 6 business days to complete. However, if there are disagreements between the departments, the placement can take longer.

Governor’s Proposals

The Governor’s budget includes three proposals related to inmate mental health care: (1) shifting inpatient psychiatric programs from DSH to CDCR, (2) converting 74 existing outpatient mental health beds into ICF beds at CMF, and (3) constructing two new MHCB facilities.

Shift Inpatient Psychiatric Programs from DSH to CDCR ($250 Million). The administration proposes to shift responsibility for the three inpatient psychiatric programs DSH operates in state prisons to CDCR beginning in 2017-18. Accordingly, the Governor’s budget proposes a shift of $250 million (General Fund) and 1,978 positions from DSH to CDCR effective July 1, 2017. Almost 90 percent of these positions are for treatment staff, including 495 psychiatric technicians and 374 registered nurses. The remaining 10 percent are administrative positions. According to the administration, having CDCR operate these inpatient psychiatric programs would reduce the amount of time it takes for an inmate to be transferred to a program as only CDCR staff would need to approve referrals for the beds. Specifically, the administration expects that the time needed to process an ICF referral will decline from 15 business days to 9 business days and from 6 business days to 3 business days for APP referrals.

CDCR plans to operate the three inpatient psychiatric programs in the same manner as DSH for two years. For example, CDCR plans to use identical staffing packages and classifications to provide care and security. The department indicates that it will assess the current staffing model during these two years and determine whether changes to these programs are necessary. We note that the Governor does not propose shifting responsibility for the 306 beds in DSH-Atascadero and DSH-Coalinga that serve low-custody ICF inmates. According to the administration, CDCR does not currently have sufficient capacity to accommodate the inmates who are housed in these beds. However, the administration indicates that the long-term plan is to shift these inmates to CDCR when capacity becomes available.

Conversion to ICF Beds at CMF ($11.4 Million). The Governor’s budget proposes $11.4 million from the General Fund and 90 positions to convert 74 existing outpatient mental health beds into ICF beds at CMF. This is based on a per bed cost of about $154,000 for additional staff. This cost is not comparable to other inpatient psychiatric programs because it does not include the cost for existing staff at the facility that would be used to support the ICF beds. The proposed ICF beds would be operated by CDCR, consistent with the administration’s plan for CDCR to have full responsibility for all inpatient psychiatric beds.

Construct Two New MHCB Facilities ($112 Million). The Governor’s budget also proposes two capital outlay projects to increase MHCB capacity. First, the budget proposes $57 million in General Fund support to construct a 50-bed MHCB facility at the Richard J. Donovan (RJD) Correctional Facility in San Diego. Second, the budget proposes $55 million in General Fund support to construct a 50-bed MHCB facility at the California Institution for Men (CIM) in Chino. The administration estimates that the annual cost to operate each facility will be $24 million. We also note that the proposed facility at CIM would require the construction and staffing of guard towers because the facility would be built outside the existing electric fence. The department indicates that staffing the guard towers would cost an additional $3.9 million annually. The facilities would be completed by the end of 2020-21.

LAO Assessment and Recommendations on Proposed Shift to CDCR

Proposed Shift Could Achieve Notable Outcomes . . . Shifting the inpatient psychiatric programs from DSH to CDCR could reduce wait times and, as a result, allow inmates to be admitted to appropriate treatment programs sooner than otherwise. This could help improve the quality of care these inmates receive. In addition, the shift could generate state savings by reducing the number of days that inmates spend in MHCBs, which are more costly than inpatient psychiatric beds. The proposal could also achieve economies of scale by having only one department oversee inmate mental health beds. For example, it would reduce the need to maintain two administrative and supervisory structures and eliminate the need for staff involved in transferring inmates between CDCR and DSH.

. . . But Uncertain if Notable Outcomes Will Actually Be Achieved. While the Governor’s proposed shift in responsibility is well intended, there is significant uncertainty regarding the extent to which the shift will actually achieve the desired outcomes. Specifically, it is uncertain:

- What Will Happen to Program Costs? While the initial costs of operating inpatient psychiatric programs would not change once they are transferred to CDCR, it is uncertain how such costs might change in the long run. On the one hand, as discussed above, the proposal could reduce operational costs. On the other hand, there are reasons why it could increase costs. For example, DSH uses Medical Technical Assistants (MTAs) that combine nursing and custody responsibilities, which prevent the need for hiring two separate staff members for these functions. According to CDCR, it does not plan to use MTA positions in the long run, which would increase costs. Moreover, the cost per bed of the units currently operated by CDCR is $301,000 per year—well above the $216,000 cost per bed for the in-prison programs operated by DSH. This difference could be driven by various factors, including (1) the populations served by CDCR are very different from those served by DSH and (2) there could be economies of scale achieved by DSH by operating larger programs. Despite these notable differences, the much greater CDCR per-bed cost raises concern.

- How Will Quality of Care Be Affected? Given that the administration has not provided information regarding how these programs will be operated in the long term, it is unclear whether the programs will be as effective as the current programs operated by DSH. The department has indicated that it plans to operate the program differently after two years, such as by no longer using MTA positions, but it is uncertain what other changes might occur and how those changes would affect the level of service provided.

Recommend Rejecting Complete Shift and Instead Pilot Proposed Shift . Given the significant uncertainty on whether the proposed shift in responsibility would result in more cost-effective care being delivered, we recommend that the Legislature reject the Governor’s proposal and instead shift a limited number of beds over a three-year period. Specifically, we recommend the Legislature implement a pilot program in which CDCR would provide inpatient psychiatric care to a portion of inmates who would otherwise get their care from DSH. Such a pilot would allow the Legislature to determine (1) whether wait times for these programs decrease as expected, (2) what particular staffing changes need to be made and the cost of making those changes, and (3) the effectiveness of the treatment provided. We recommend that the pilot include both ICF and APP units and be operated at more than one facility. For example, CDCR could have responsibility for an APP unit at CHCF and an ICF unit at CMF. This would ensure that the pilot can test CDCR’s ability to operate multiple levels of care at multiple facilities. In addition, we recommend that the pilot include one unit that is currently being operated by DSH, and one new unit that would be operated by CDCR. (As we discuss below, we recommend the Legislature approve the Governor’s proposal to convert existing beds into ICF beds at CMF, but that the beds be operated by CDCR on a limited-term basis rather than on an ongoing basis as proposed.)

In order to ensure that the Legislature has adequate information after the completion of the pilot to determine the extent to which inpatient psychiatric program responsibilities should be shifted to CDCR, we recommend that the Legislature require CDCR to contract with independent research experts, such as a university, to measure key outcomes and provide an evaluation of the pilot to the Legislature by January 10, 2019. These key outcomes would include how successfully CDCR was able to return inmates to general population without additional MHCB or inpatient psychiatric program admissions, whether wait times decreased, and the cost of the care provided. We estimate the cost of this evaluation to be around a few hundred thousand dollars.

LAO Assessment and Recommendations on Proposed Conversion to ICF Beds at CMF

Additional Capacity Appears Justified. Given that there is currently a 120 inmate waitlist for inpatient psychiatric beds, the proposal to provide 74 additional beds appears justified on a workload basis. We also note that activating these additional beds could help reduce the amount of time that inmates on the waitlist spend in comparatively more expensive MHCBs.

Recommend Approving CMF Positions and Funding on a Pilot Basis. In view of our above recommendation to shift responsibility for some inpatient psychiatric programs from DSH to CDCR on a three-year pilot basis, we recommend that the Legislature approve the proposed funding and positions to convert outpatient mental health beds into CDCR-operated ICF beds on a three-year, limited-term basis. This would help the Legislature assess whether CDCR can successfully develop its own approach to staffing inpatient psychiatric units.

LAO Assessment and Recommendations on Proposed MHCB Construction

Possible Reduction in Need for MHCBs. There are two factors that could potentially reduce the need for MHCBs by the time the proposed beds at RJD and CIM would be activated by the end of 2020-21. First, the implementation of Proposition 57 is expected to reduce the inmate population, which could also reduce the mental health population and the need for MHCBs. For example, under the administration’s current plans to implement Proposition 57, some inmates in inpatient psychiatric programs who were not earning good-time credits—which reduce an inmate’s sentence for adhering to prison rules—or were earning these credits at lower rates, may become eligible to earn credits. Because this would reduce the population of these inmates, it could also reduce the need for MHCBs. Second, if the Legislature approves the ICF unit proposed at CMF, it could reduce the amount of time inmates spend in MHCBs waiting for admission to ICF beds.

CIM Project Appears More Costly Than Necessary. As discussed above, the proposed facility at CIM would require the construction and staffing of guard towers because the facility would be built outside the existing electric fence. The department indicates that staffing the guard towers would cost $3.9 million annually. While the department has not completed the analysis of whether an electric fence is feasible, it estimates the fence would cost between $13 million to $18 million on a one-time basis with minor ongoing maintenance costs. This means that it would be potentially much less expensive in the longer run to modify the electric fence to prevent the need for staffing the guard towers.

Recommend Rejecting Proposed MHCB Construction Projects. Given the uncertain need for additional MHCBs, we recommend the Legislature reject the Governor’s proposal at this time to build two 50-bed MHCB facilities at RJD and CIM. CDCR should monitor the effects of Proposition 57, the activation of the ICF unit proposed for CMF, and any shift in mental health program responsibilities on the need for additional MHCBs. If this information shows a continuing need for additional MHCBs, the department can make a new request at that time. To the extent that the department determines there remains a need for the CIM project, it will have time to complete a project cost estimate for the CIM facility using an electric fence as opposed to manned guard towers. If it is more cost-effective to use an electric fence, the department could adjust its request accordingly.

Other Issues

Video Surveillance at High Desert State Prison and Central California Women’s Facility

LAO Bottom Line. We recommend that the Legislature reject the Governor’s proposal to implement comprehensive video surveillance at High Desert State Prison (HDSP) and Central California Women’s Facility (CCWF) as it is premature until the current video surveillance pilot is completed. In addition, we recommend that the Legislature direct the department to report at spring budget hearings on alternative strategies that it is considering for addressing the problems at HDSP and CCWF.

Background

Staff Misconduct at HDSP. The Office of the Inspector General (OIG), which provides external oversight of CDCR, has raised numerous concerns about mismanagement and staff misconduct at HDSP. In a 2015 special review of HDSP, the OIG highlighted several areas of concern, including staff intentionally endangering inmates by disclosing their sex offender status to other inmates and staff tampering with inmate appeals and mail. In total, the OIG made 45 specific recommendations to CDCR, one of which was the installation of cameras in all inmate areas at the prison. This recommendation was made in response to three specific problems identified by the OIG:

Use of Excessive Force. Incident reporting data, staff and inmate complaints, rules violation reports, and Office of Internal Affairs’ investigations reviewed by the OIG suggest that HDSP staff have used excessive or unnecessary force on inmates at alarming rates.

Reluctance to Engage When Force Is Required. Despite the apparent excessive force used against inmates, the OIG learned from interviewing inmates and reviewing incident reports that HDSP staff may be delaying their response in some circumstances where use of force is necessary to stop serious harm to inmates who are victims of attack.

Lack of Reliable Eyewitness Accounts. The OIG argues that allegations of inappropriate use of force are very difficult to substantiate because of the practice among HDSP correctional officers of refraining from providing information that could implicate a fellow officer.

Comprehensive video surveillance, the OIG believes, would provide objective evidence needed for the department to identify and discipline staff who use force inappropriately and to exonerate staff who are wrongfully accused. We note that the OIG’s investigation at HDSP did not focus on inmate violence, contraband, or suicides, and did not recommend video surveillance cameras as a way to address those problems.

In 2016, the department launched a video surveillance pilot at HDSP in response to the OIG findings. To implement the pilot, the department installed 207 cameras in one portion of HDSP and purchased video monitoring software using existing resources. Researchers at the University of California, Irvine are currently evaluating these cameras for their impact on various metrics, including use of force incidents, rule violations, and attempted suicides. The evaluation is planned to be completed by August 2017.

Inmate Misconduct and Suicides at CCWF. According to CDCR, CCWF has experienced an increase in violence, attempted suicide, and contraband since the transfer of women offenders from Valley State Prison for Women to CCWF in 2012. For example, the department reports cell phone related rule violations increased at CCWF by 164 percent between 2012 and 2015. It also reports that in 2015-16, CCWF had 146 violent incidents and 1 riot, and 11 attempted suicides.

Video Surveillance at Other CDCR Institutions. Several of CDCR’s prisons currently have recorded video with varying degrees of institutional coverage. For example, California City Correctional Facility and CHCF have video coverage of all facilities, yards, and housing units.

Governor’s Proposal

The Governor’s budget proposes $11.7 million from the General Fund on a one-time basis and four positions to implement a comprehensive video surveillance program at HDSP and CCWF. These funds would support staff compensation, the purchase of video surveillance equipment, and other related costs. Under the proposal, $1.2 million will be needed annually beginning in 2018-19 to support maintenance of hardware and software. The department plans to assess ongoing staffing needs after the video surveillance systems are implemented.

CDCR expects the cameras to (1) provide objective evidence with which to investigate inmate allegations against staff, (2) reduce violent incidents, (3) reduce contraband entering secure perimeters, and (4) reduce attempted suicides.

LAO Assessment

Premature to Expand Video Surveillance Before Evaluation Complete. Given that CDCR has not completed the initial pilot project underway at HDSP to assess the effectiveness of video surveillance, we find it premature to expand the project. Moreover, CDCR has not provided any evidence—from either its use of video cameras already installed in several of its institutions or from other prison systems’ experiences with video surveillance—to suggest that the proposed expansion of video surveillance will address the problems it highlights at HDSP and CCWF.

Unclear How Video Surveillance Will Achieve Department’s Other Stated Goals. CDCR has argued that the problems at HDSP and CCWF are crises that necessitate the expansion of video surveillance at the institutions before the evaluation of the current pilot at HDSP is available. However, CDCR has not presented any explanation of how video surveillance could yield all of the department’s stated goals. While we think it is reasonable that video surveillance could provide objective evidence to inform investigations into staff misconduct, it is unclear how video surveillance might reduce violent incidents, contraband, and suicides. This is for two reasons:

- Lack of Monitoring Limits Ability to Respond to Incidents. First, CDCR is not proposing to monitor all cameras in real time or to watch all recorded video. As such, it is unclear how CDCR could use videos as a means to intervene in violent incidents, contraband smuggling, or attempted suicide.

- Limited Coverage Reduces Deterrent Effect. Second, CDCR argues that the mere existence of cameras could deter negative behaviors. However, we find it equally plausible that inmates or staff would simply move illicit activities or suicide attempts out of camera view.

In light of these concerns, it is possible that the use of video surveillance cameras may not be an effective way to address most of the problems at HDSP and CCWF that CDCR intends to address. As indicated above, the OIG recommended the installation of cameras at HDSP specifically to address inappropriate use of force by staff. Until the results of the video surveillance pilot at HDSP are available, the department should focus on the OIG’s other recommendations to address this concern, such as ensuring that supervisors are sufficiently scrutinizing incidents where inmates receive injury. In addition, the OIG’s investigation at HDSP did not focus on inmate violence, contraband, or suicides, and did not recommend video surveillance cameras as a way to address those problems. Until the results of the video surveillance pilot at HDSP are available, the department should develop its own strategies for addressing its concerns about inmate violence, contraband, and suicides at HDSP and CCWF.

LAO Recommendation

We recommend that the Legislature reject the Governor’s proposal to implement comprehensive video surveillance at HDSP and CCWF given that a pilot is currently underway and the department has not provided evidence or an explanation as to how cameras can address all of the problems it describes at these institutions. We recommend that the Legislature direct the department to provide it with the results of the pilot currently underway at HDSP once they are available in August 2017. If the pilot shows that video surveillance can effectively achieve some or all of the department’s goals, CDCR can request funding to expand video surveillance as part of the 2018-19 budget process. Finally, we recommend that the Legislature direct the department to report at spring budget hearings on other strategies that it is considering for addressing the problems at HDSP and CCWF.

Delayed Activation of Infill Facility at RJD

Background. The 2016-17 Budget Act included $25 million for the activation of a new infill facility at RJD in San Diego based on an assumption that the facility would be activated on August 1, 2016. The department indicates that, due to construction delays, the activation of the infill facility did not occur until December 12, 2016.

Governor’s Budget Does Not Reflect Savings From Delayed Infill Activation. The roughly four-month delay in the activation of the new infill facility at RJD should have reduced the workload for CDCR relative to what was assumed in the budget for the first part of 2016-17. This is because the department needed the correctional officers that were assigned to the prison for about four fewer months than previously assumed. However, the Governor’s budget for CDCR does not reflect any savings from such workload reductions.

LAO Recommendation. We recommend that the Legislature direct the department to provide it with an estimate of savings from the delayed activation of the infill facility at RJD no later than April 1 so that this adjustment can be incorporated into the department’s budget.

Health Care Access Officers

LAO Bottom Line. We recommend that the Legislature direct CDCR to provide additional information justifying the proposed reallocation of health care access staff. Based on this information, the Legislature would be in a better position to determine whether the proposed reallocation of health care access staff is warranted or whether it needs to be modified. If the department cannot provide this information, we recommend that the Legislature reject the proposed reallocation and reduce CDCR’s budget by 48.2 health care access positons and about $6 million in General Fund support.

Background

Housing Conversions. CDCR periodically converts housing units to accommodate fluctuations in the security requirements or needs of its inmate population, such as by converting administrative segregation beds (high security) to general population beds (lower security). When the department converts a housing unit, the unit’s staffing complement is adjusted to reflect the requirements of the new inmates to be housed there.

Health Care Access Staff. CDCR employs correctional staff who specialize in escorting and transporting inmates to receive health care. These staff escort inmates to health care appointments within the institutions, as well as transport and guard inmates who need medical services in the community. Health care access staff are allocated to institutions based on needs analyses conducted by CDCR’s Program Support Unit. The 2016-17 budget included $465 million and 3,395.4 positions for health care access staff.

Governor’s Proposal

Savings From Housing Unit Conversions. The Governor’s budget proposes to reduce General Fund support for CDCR by $42.4 million in 2016-17 and by $8.3 million in 2017-18 to account for net savings from the conversion of various housing units. According to the administration, a significant driver of conversions proposed in 2016-17 and 2017-18 is the implementation of the 2016 Ashker v. Brown settlement, which made the criteria for housing inmates in security housing units more stringent. (Security housing units are used to house inmates who the department considers to be the greatest threat to the safety and security of its institutions.) For example, at California Correctional Institution in Tehachapi, the administration is proposing to convert 469 security housing beds to 533 sensitive needs beds, which are reserved for inmates who cannot be housed in the general population due to concerns for their safety. Because security housing units require more custody staff than most other units, these conversions would result in net savings.

Reallocation of Health Care Access Staff. For each proposed housing unit conversion, CDCR is proposing a corresponding revision to the number of health care access staff. While some conversions will increase the need for health care access staff, on net, CDCR expects the proposed housing unit conversions to reduce the need for health care access staff by 48.2 positions and $6 million in 2017-18. However, CDCR reports that other housing units (that are not affected by the conversions) have an unmet need for health care access staff that is currently being met with overtime. Furthermore, the department reports that systemwide workload for health care access staff is increasing. Accordingly, the department is proposing to reallocate the 48.2 positions and $6 million made available by the housing unit conversions to units with the highest need for health care access staff in 2017-18 as identified by the Program Support Unit’s analysis.

LAO Assessment

Proposed Housing Unit Conversions Appear Reasonable. The department provided sufficient justification for the need to make the proposed housing unit conversions. Accordingly, we have no concerns with the proposed conversions and their corresponding General Fund savings in 2016-17 and 2017-18.

Lack of Justification Showing Need for Reallocation. CDCR has provided two justifications for its proposed reallocation of the 48.2 health care access staff and about $6 million in associated funding: (1) the currently high rates of overtime worked by other health care access staff and (2) the anticipated increase in the systemwide health care access workload. We note, however, that the administration has been unable to provide sufficient data on current and projected overtime worked by health care access staff at the institutions that would receive reallocated staff or the analysis done by CDCR’s Program Support Unit to assess the current and projected need for health care access staff at these institutions. As such, it is difficult for the Legislature to determine whether the proposed reallocation of health care access staff is justified.

Savings From Reduced Overtime Not Accounted for. To the extent that the positions do need to be reallocated to reduce overtime, we estimate that the 48.2 health care access staff could reduce overtime costs by as much as $4 million. Despite this, the administration has not proposed any reduction in the health care access overtime budget.

LAO Recommendation

Approve Housing Unit Conversions. We recommend that the Legislature approve the proposed housing unit conversions and the corresponding adjustments to the department’s budget.

Require Additional Information Before Taking Action. To assist the Legislature in its review of the proposed reallocation of health care access staff, we recommend that it direct CDCR to provide the following information by April 1: (1) the Program Support Unit’s data and analysis of current and projected need for health care access staff at institutions that would receive the reallocated staff and (2) current and projected health care access staff overtime rates at these institutions. With this information, the Legislature would be in a better position to determine whether the proposed reallocation of health care access staff is warranted or whether it needs to be modified. If the department is unable to provide the above information, we recommend that the Legislature reject the proposed reallocation and reduce CDCR’s budget by 48.2 health care access staff and $6 million in General Fund support.

Minimum Support Facility Perimeter Fence at California State Prison, Los Angeles County

LAO Bottom Line. We recommend that the Legislature reject the Governor’s proposal to raise the height of the Minimum Support Facility (MSF) fence at California State Prison, Los Angeles County (LAC) in Lancaster because the need for a higher fence has not been justified.

Background

LAC has an MSF, which houses CDCR’s lowest security level inmates outside of the institution’s electrified fence. The MSF is surrounded by an eight foot tall chain link fence topped with 30 inches of coiled razor wire. The loops of razor wire come within approximately six feet of the ground.

Governor’s Proposal

The Governor’s budget proposes a one-time General Fund augmentation of $299,000 to modify the MSF chain link fence in order to raise the clearance of the razor wire by two feet.

Need for Higher Fence Has Not Been Justified

According to CDCR, design criteria guidelines require the razor wire to be installed on a fence that is at least ten feet tall. CDCR reports that the razor wire on the fence at LAC, which comes within six feet of the ground, is a safety concern to inmates and staff. The department maintains that raising the fence to meet design criteria guidelines would both mitigate this safety concern and improve the security of the facility.

However, the department reports that no person has been injured by the razor wire and only one inmate has scaled the fence to successfully escape since the razor wire was installed in the mid-1990s. With no historical examples of injuries caused by the razor wire and a very low rate of escape, there is no reason to believe that injuries and escape are likely to occur in the future. Thus, we find that the current fence is adequate.

LAO Recommendation

We recommend that the Legislature reject the Governor’s proposal to provide General Fund support to raise the height of the MSF fence at LAC because the need for a higher fence has not been justified.

California Prison Industry Authority Retiree Health Benefits

LAO Bottom Line. We recommend the Legislature approve the administration’s proposed budget trailer legislation that clarifies that the California Prison Industry Authority (CalPIA) is only required to fund retiree health benefit and pension liabilities to the level established by the administration or as determined by the California Public Employees’ Retirement System (CalPERS). We also recommend the Legislature require CalPIA to report at budget hearings on how it was recently able to accumulate a significant amount of reserves—above what is necessary to support its programs

Background

CalPIA. CalPIA is a semi-autonomous state agency that provides work assignments and vocational training to inmates in California prisons and is funded primarily through the sale of the goods and services produced by the program. It is managed by the Prison Industry Board, which is composed of 11 members including the Secretary of CDCR, as well as several legislative and gubernatorial appointees. State law requires state agencies to purchase products and services offered by CalPIA whenever possible. Accordingly, the majority of goods and services produced by CalPIA are sold to other state departments. The largest purchaser of CalPIA goods—accounting for over half of CalPIA sales—is CDCR. For example, CalPIA provides janitorial services for CDCR health care facilities and sells the department tables for their cafeterias. In 2016-17, CalPIA expects to generate $232 million in revenue from the sale of its goods and services and to spend nearly $230 million to operate its programs.

Funds raised from the sale of goods produced by CalPIA are deposited in the Prison Industries Revolving Fund (PIRF) for the purchase of materials and equipment, salaries, and the administration of CalPIA programs. Section 2806 of the Penal Code requires the fund to be self-sufficient and maintain a balance of $730,000. If the PIRF has reserves beyond what is necessary to support its programs, state law authorizes the Secretary of CDCR and the Director of the Department of Finance to direct the State Controller to transfer funds from the PIRF to the General Fund. For the past three years, PIRF has carried a balance far in excess of $730,000. The last time any excess funds were transferred to the General Fund was in 2013, when the administration transferred $13 million from the PIRF to the General Fund.

While CalPIA is not subject to annual appropriation by the Legislature, it is required by statute to submit an annual report to the Legislature regarding (1) the financial activity of its programs, (2) significant changes to existing programs, (3) the development of new programs, and (4) the number of prison inmates working in existing programs.

State Retiree Health Benefits. As part of their compensation, eligible retired state employees receive state contributions towards their health premiums. Instead of setting money aside when employees earn the benefit over the course of their careers, the state has—until recently—paid for these benefits on a pay-as-you-go basis after employees retire.

This has resulted in a large—exceeding $70 billion and growing—unfunded liability for the state. Since 2015, the state has started implementing a plan to address this liability over the next few decades through: (1) regular state and employee contributions to a trust fund administered by CalPERS and (2) reduced benefits for future employees. (See our March 2015 report, The 2015-16 Budget: Health Benefits for Retired State Employees, for details on the unfunded liability and the state’s prefunding plan.)

Pursuant to established rules for reporting liabilities associated with retirement benefits, CalPIA began reporting its retiree health benefit liabilities, and other retirement liabilities, on its financial statements. While state agencies, including CalPIA, are required to report these liabilities, they are not required to prefund these liabilities, as these liabilities are being addressed through statewide policy.

However, CalPIA believes that the Penal Code requires it to remain solvent such that it must actually have cash reserves to pay any liability reported in its financial statements. On this view, if the reserves used to fund the liability were used for another purpose—such as being transferred to the General Fund—CalPIA’s reported liabilities would exceed reported assets, resulting in a deficit on its financial statements. Based on its interpretation, CalPIA chose to raise revenues so that it could report a cash reserve equal to the estimated liability associated with its employees’ earned retiree health benefits—about $63 million—to avoid reporting a deficit in its financial statements.

PIRF Balance Transferred to General Fund. The administration does not interpret the Penal Code to require CalPIA to prefund retiree health benefit liabilities outside of the statewide policy currently being implemented. Accordingly, in January 2017 the administration directed the State Controller to transfer the $63 million that CalPIA held in reserve to prefund retiree health benefit liabilities from the PIRF to the General Fund. After accounting for this fund transfer, the 2016-17 PIRF balance is estimated to be about $22 million.

Governor’s Proposal

The administration proposes budget trailer legislation that prevents CalPIA from establishing reserves to prefund retiree health benefit and pension liabilities in the future and clarifies that CalPIA is only required to fund retiree health benefit and pension liabilities to the level established by the administration or as determined by CalPERS.

LAO Assessment

CalPIA Does Not Need to Prefund Retiree Health Benefit Liabilities. While seeking to prefund retiree health liabilities is a laudable goal, we concur with the administration that CalPIA is not required to do so by maintaining a reserve in the PIRF. Instead, this liability will be addressed through the statewide retiree health benefit prefunding policy, consistent with the approach the state is taking for other departments.

CalPIA Has Maintained More Reserves Than Necessary to Support Its Programs. If CalPIA had not raised the revenue to prefund the $63 million liability, it might have been able to support the same level of CalPIA programs at a lower cost, which could have reduced the prices of CalPIA goods. This, in turn, would have reduced costs for the state agencies and other entities that purchase CalPIA goods and services. Alternatively, CalPIA could have used the funds for other purposes, such as repairing its infrastructure. This also could have reduced state costs. For example, CalPIA requested $1.8 million from the General Fund in 2016-17 to make repairs at San Quentin State Prison to expand its computer coding program. This request would not have been necessary if CalPIA dedicated a portion of the fund balance in the PIRF to this project.

LAO Recommendations

Approve Proposed Budget Trailer Legislation. We recommend that the Legislature adopt the administration’s proposed budget trailer legislation, as it clarifies that CalPIA is not required to prefund retiree health benefit and pension liabilities and prevents it from doing so in the future.

Report on How PIRF Balance Was Accumulated. We also recommend that the Legislature direct CalPIA to report at spring budget hearings on how it was recently able to accumulate a significant amount of reserves above what is necessary to support its programs, in order to fund its retiree health benefit liabilities. For example, CalPIA should report on the specific programs not funded in the past. In addition, CalPIA should report on how its programs will change moving forward given the proposed budget trailer legislation preventing it from building reserves to prefund retiree health benefit and pension liabilities. For example, CalPIA should report on (1) whether the pricing structure of CalPIA products will change, and (2) whether CalPIA will pursue new initiatives, projects, or programs in the future as a result of not having to set aside these funds. This information would allow the Legislature to determine if further changes should be made to CalPIA programs.