LAO Contacts

- Medi-Cal

- In-Home Supportive Services (IHSS)

- County Financing

February 27, 2017

The 2017-18 Budget

The Coordinated Care Initiative:

A Critical Juncture

- Introduction

- Background

- CCI Results and Challenges to Date

- Governor’s Proposal

- LAO Assessment of Governor’s Proposal

- Should the Legislature Adopt the Governor’s Proposal?

- Should the Legislature Enhance the Governor’s Proposal?

- Conclusion

- Appendix: How Ending the IHSS MOE Affects 1991 Realignment

Executive Summary

Medi‑Cal and Medicare Jointly Provide Health Care and Long‑Term Services and Supports (LTSS) to Many Seniors and Persons With Disabilities (SPDs). About 2.1 million SPDs are enrolled in Medi‑Cal, the state‑federal program providing health care and LTSS to low‑income persons. LTSS include, among other supports and services, institutional care in skilled nursing facilities and home‑ and community‑based services (HCBS) such as those provided by the In‑Home Supportive Services (IHSS) program. About two‑thirds of SPDs are also eligible for Medicare, the federal program that provides health care services to qualifying persons over age 65 and certain persons with disabilities. The SPDs who are eligible for both Medi‑Cal and Medicare are known as “dual eligibles” and receive services paid by both programs.

Coordinated Care Initiative (CCI) Implemented to Improve Coordination of Health Care and LTSS for SPDs and Reduce Overall Costs. The CCI is a joint state‑federal demonstration project that was implemented beginning in 2012‑13, and designed to improve the coordination of health care and LTSS and reduce the overall costs of providing care for SPDs. The CCI made a variety of changes in the seven “demonstration counties” where it was implemented, including: (1) integrating Medi‑Cal and Medicare benefits for dual eligibles opting for managed care through a program known as Cal MediConnect, (2) mandatorily enrolling dual eligibles in managed care for their Medi‑Cal benefits, (3) integrating LTSS under Medi‑Cal managed care, (4) introducing state‑level collective bargaining for IHSS providers, and (5) creating a universal assessment tool for all HCBS LTSS. On a statewide basis, the CCI replaced counties’ historical 35 percent share of nonfederal costs of the IHSS program with a maintenance of effort (IHSS MOE) that required counties to maintain their 2011‑12 IHSS expenditure levels, with the addition of an annual growth factor of 3.5 percent and the costs of locally negotiated IHSS wage increases. Included in CCI‑related legislation is a “poison pill” provision that automatically discontinues all components of the CCI if the administration determines that the CCI does not generate net General Fund savings.

CCI Discontinued Following Administration’s Determination That CCI Does Not Generate Net General Fund Savings. With the release of the Governor’s 2017‑18 budget, the administration estimated that the CCI generates net General Fund costs of $278 million in 2016‑17 and $42 million in 2017‑18. The major factor causing the CCI to generate net General Fund costs rather than savings in the administration’s determination was the IHSS MOE. In accordance with state law, this determination automatically ends the program.

However, the Administration Proposes Continuing Certain Major CCI Components. Despite the automatic termination of the CCI, the Governor’s budget proposes continuing certain major CCI components, including: (1) Cal MediConnect, (2) mandatory enrollment in managed care for dual eligibles for their Medi‑Cal benefits, and (3) the integration of LTSS other than IHSS under managed care. In effect, the Governor proposes continuing the CCI absent its IHSS components. By ending the CCI and not proposing to continue the IHSS MOE, the Governor would restore the counties’ historical share of IHSS costs.

End of IHSS MOE Provides Significant General Fund Relief While Significantly Increasing Costs for Counties. The termination of the IHSS MOE and restoration of the prior IHSS cost‑sharing ratio is projected to shift over $600 million in IHSS General Fund costs back to counties in 2017‑18. This shift in costs will create significant short‑ and long‑term fiscal challenges for counties.

Legislature Might Consider Providing Fiscal Relief to Counties. Counties have limited ability to absorb the costs of ending the IHSS MOE. Accordingly, the Legislature might consider providing some form of fiscal relief to counties to mitigate these fiscal challenges. While the administration has signaled an intent to work with counties, the Governor has not released a plan for providing fiscal relief to counties. Short‑term fiscal relief could entail a one‑time grant or loan from the General Fund. However, because the end of the IHSS MOE also creates long‑term fiscal challenges for counties, the Legislature might consider ongoing modifications to counties’ share of costs for the IHSS program.

Governor’s Proposal to Continue Parts of the CCI Is Appropriate . . . The steps taken under the CCI to enhance the coordination and integration of health care and LTSS are steps in the right direction. As such, we are supportive of the Governor’s proposal to extend certain major components of the CCI.

. . . However, the Legislature Might Build on the Governor’s Budget by Considering Ways to Include IHSS Integration in the CCI Pilot. The Governor’s action to terminate the CCI and proposal to extend certain CCI components presents an opportunity for the Legislature to provide its vision for how health care and LTSS should be integrated in the future. As an enhancement to the Governor’s scaled‑down version of the CCI, the Legislature could consider changes that build upon the gains that have been made under the CCI. Specifically, the Legislature may want to consider ways to include IHSS integration in the CCI pilot. These could range from providing some level of funding for continued care coordination between managed care plans and counties to piloting a fuller integration of IHSS within managed care in some counties. Depending on the level of IHSS integration within managed care plans, there are various trade‑offs and financing considerations that would need to be considered.

Introduction

Over two million seniors and persons with disabilities (SPDs) are enrolled in California’s Medicaid program (known as Medi‑Cal), the state‑federal program providing medical services and long‑term supports and services (LTSS) (including In‑Home Supportive Services [IHSS]) to low‑income persons. The majority of SPDs are also eligible for Medicare, the federal program that provides medical services to qualifying persons over age 65 and certain persons with disabilities. The SPDs who are eligible for both Medi‑Cal and Medicare are known as dual eligibles and receive services paid by both programs. In 2012‑13, a demonstration project known as the Coordinated Care Initiative (CCI) began implementation. The intent of the CCI was to improve the coordination of health care and long‑term care for SPDs and, in doing so, reduce the overall costs of providing care for this population that is generally expensive to serve. To achieve these goals, the CCI made a number of changes in demonstration counties related to the delivery of care to SPDs. Although the Governor originally proposed statewide expansion of CCI to all 58 counties within three years, the CCI was ultimately implemented in seven demonstration counties. On a statewide basis, the CCI also replaced counties’ historical share of cost for the IHSS program with a maintenance‑of‑effort (IHSS MOE) requirement. State law includes a “poison pill” provision that gives the Department of Finance (DOF) authority to discontinue the CCI without having to seek legislative approval if the CCI is shown not to generate net General Fund savings.

In conjunction with the release of the Governor’s 2017‑18 budget, the DOF made the determination that the CCI was not generating net General Fund savings, leading the Governor to eliminate the CCI pursuant to the poison pill provision. However, the Governor has also proposed an extension of certain major CCI components. In effect, the Governor proposes to continue the components of the CCI unrelated to IHSS. The Governor’s proposal therefore eliminates the IHSS MOE, shifting over $600 million in IHSS costs from the General Fund to counties in 2017‑18.

In this report we provide (1) background on the health care and LTSS issues that the CCI was intended to address, (2) an update on the CCI’s results and challenges to date, (3) an assessment of the Governor’s elimination of the CCI and budget proposal to extend certain CCI components, and (4) options for the Legislature on how to move forward. As ending the IHSS has major, and rather complex, implications for 1991 realignment, we include a technical appendix at the end of this report that provides an in‑depth analysis of these implications.

Background

Fragmented System of Care for SPDs

In this section, we describe the multiple systems of care that low‑income SPDs and dual eligibles must navigate to access their health care and LTSS benefits. This fragmented system of care creates challenges around care coordination as well as some perverse fiscal incentives. The CCI was intended to address these challenges. In this section, we describe the multiple systems of care, the challenges resulting from fragmentation, and how the CCI was intended to address these challenges.

Medicare and Medi‑Cal Both Serve SPDs

Medicare Is a Federal Health Coverage Program for the Elderly. Medicare is the federal health insurance program for qualifying persons over age 65 and certain people with disabilities, and is overseen by the federal Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare pays for most physician and hospital care and pharmacy benefits for program beneficiaries. Medicare also covers certain mental health services, including outpatient treatment and most acute inpatient psychiatric admissions. Medicare beneficiaries generally pay for their benefits through cost‑sharing arrangements such as premiums, deductibles, coinsurance, and copayments.

Medi‑Cal Is a Joint State‑Federal Health Coverage Program for Low‑Income Californians. Medi‑Cal is a joint state‑federal health care program that provides health care services for low‑income residents, including SPDs. Medi‑Cal’s health‑related services include hospital inpatient and outpatient care, doctor visits, and coverage of prescription drugs and durable medical equipment. Medi‑Cal also provides substance abuse treatment services and an array of mental health services for beneficiaries with mild and serious mental illnesses. The federal government and the state share the costs of the Medi‑Cal program. For most Medi‑Cal enrollees, including SPDs, California receives a 50 percent Federal Medical Assistance Percentage—meaning the federal government pays for one‑half of these enrollees’ Medi‑Cal costs.

Counties’ Roles in Medi‑Cal. Counties play a major role in the Medi‑Cal program, for example, by conducting eligibility determinations; directly providing or overseeing the delivery of certain Medi‑Cal benefits such as mental health and substance use disorder services; and, in some counties, administering their own Medi‑Cal managed care plans. As discussed later, counties share in some nonfederal Medi‑Cal costs.

LTSS. In addition to the health care services described above, Medi‑Cal provides a variety of LTSS that are commonly categorized into two types: (1) institutional care, such as care in skilled nursing facilities (SNFs); and (2) home‑ and community‑based services (HCBS) aimed at maintaining SPDs in the community and preventing unnecessary hospitalizations and SNF stays. Major Medi‑Cal LTSS include:

- SNF Care. SNFs provide nursing, rehabilitative, and medical care to facility residents. Generally, SNF residents receive their medical care and social services at the facility.

- IHSS. The IHSS program provides in‑home and community‑based personal care for people who cannot safely remain in their own homes without such assistance. Examples of services provided through IHSS include assistance with such tasks as bathing, dressing, housework, and meal preparation.

- Community‑Based Adult Services (CBAS) Program. The CBAS program is an outpatient, facility‑based service program that provides services to program participants by a multidisciplinary staff. Services provided through CBAS include professional nursing services; physical, occupational, and speech therapies; mental health services; therapeutic activities; social services; personal care; meals and nutritional counseling; and transportation to and from the participant’s residence.

- Multipurpose Senior Services Program (MSSP). The MSSP benefit provides both social and health care case management services for Medi‑Cal recipients aged 65 or older who meet the eligibility criteria for a SNF.

Services Are Provided Through Two Main Systems. Medi‑Cal and Medicare provide health care through two main delivery systems: fee‑for‑service (FFS) and managed care. In an FFS system, a health care provider receives an individual payment for each medical service provided. In a managed care system, managed care plans receive a per member per month (“capitated”) payment in exchange for providing health care coverage to enrollees. Managed care plan capitated payments cover the expected costs of their members’ covered services, which places plans at risk and provides an incentive for plans to discourage unnecessary utilization of health care services. (We note that managed care plans are required to provide all medically necessary health care services and LTSS for which they receive payment.) For most Medi‑Cal beneficiaries, enrollment in managed care is mandatory. However, for Medicare beneficiaries, enrollment in managed care is voluntary.

LTSS Historically a Medi‑Cal FFS Benefit. LTSS have historically been delivered as Medi‑Cal FFS benefits, meaning that Medi‑Cal managed care plans have not been paid or been responsible for coordinating and delivering LTSS for their enrollees.

Dual Eligibles Have Historically Been Exempt From Mandatory Managed Care Enrollment. As discussed earlier, dual eligibles are SPDs with health care coverage through both Medi‑Cal and Medicare. While Medi‑Cal‑only SPDs have been mandatorily enrolled in Medi‑Cal managed care since 2012, dual eligibles have historically been exempt from mandatory managed care enrollment. Accordingly, dual eligibles have historically been able to utilize either the FFS or the managed care delivery system for the Medi‑Cal portion of their health care and LTSS benefits.

SPDs Are an Expensive Population to Serve. Generally, SPDs are much more expensive to serve than other Medi‑Cal beneficiaries because of the higher prevalence of complex medical conditions and greater functional needs within this population.

Interaction Between Medicare and Medi‑Cal. Under federal law, Medi‑Cal is the payer of last resort for all covered services. This means that all other third party sources of health care and LTSS coverage for Medi‑Cal beneficiaries, including Medicare, must be exhausted prior to any Medi‑Cal reimbursement for health care. Accordingly, Medicare pays for most physician, hospital, and prescription drug (pharmacy) benefits for dual eligibles, with Medi‑Cal covering a smaller portion of these costs—known as “wraparound coverage.” However, Medi‑Cal pays for some benefits that Medicare does not cover, such as extended stays in SNFs and other LTSS.

IHSS Is County‑Administered. IHSS is generally a Medi‑Cal FFS benefit administered by county welfare agencies. Accordingly, county social workers carry out IHSS eligibility determinations and redeterminations and assess IHSS recipients for their level of need for service hours. While the IHSS recipient is considered the employer of his or her provider, counties have historically been responsible for setting provider wages and benefits through collective bargaining.

IHSS Funded With a Combination of Federal, State, and Local Funds. As previously mentioned, the IHSS program is primarily delivered as a Medi‑Cal benefit. Accordingly, around 50 percent of IHSS program costs are paid for by the federal government. The nonfederal costs of the IHSS program are shared by the state and counties. Historically, the state paid for 65 percent of nonfederal program costs and counties paid for the remaining 35 percent. There are some IHSS costs that are not shared according to the historical state‑county cost‑sharing arrangement. For example, pursuant to state law, the state only participates in funding IHSS provider wages and benefits up to $12.10 per hour, placing the responsibility on counties to fund 100 percent of the nonfederal costs of IHSS provider wages and benefits above $12.10 per hour.

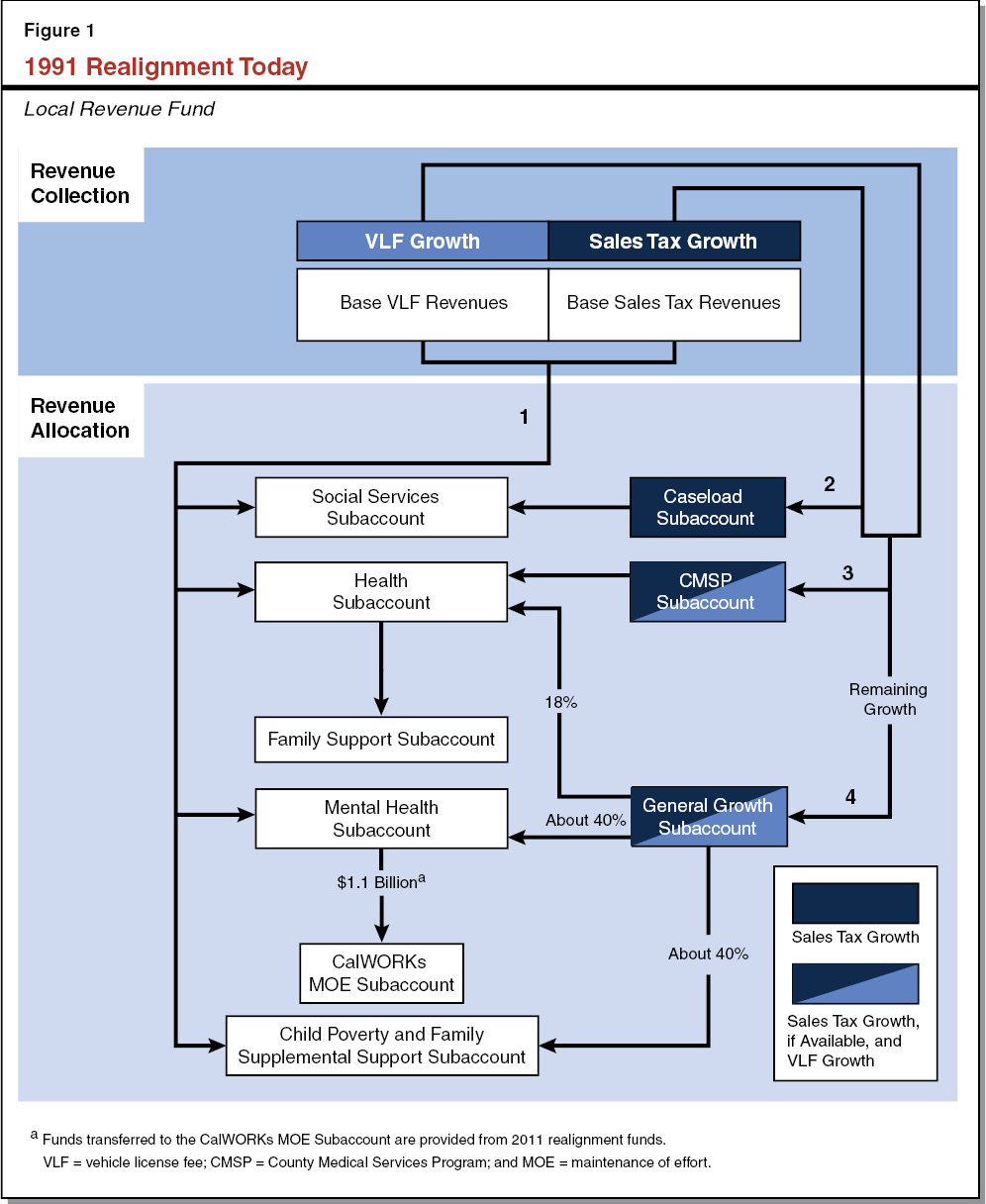

Local Funds for IHSS Primarily Come From 1991 Realignment Revenues. In 1991, the state enacted a major change in the state and local government relationship, known as realignment. The 1991 realignment package: (1) transferred several programs from the state to the counties, including indigent health, public health, and mental health programs; (2) changed the way state and county costs are shared for certain social services and health programs, including IHSS; and (3) increased the sales tax and vehicle license fee and dedicated these increased revenues for the increased financial obligations of counties. In the case of the IHSS program, 1991 realignment increased the county share of nonfederal costs to 35 percent. For a more complete explanation of 1991 realignment and revenue allocations, particularly as regards IHSS, please see Section 1 of the Appendix.

Implications of the Fragmented System of Care

We outlined above the distinct systems of care that low‑income SPDs must navigate to access their health care and LTSS benefits. The fragmented system of care introduces a number of challenges for the state, managed care plans, and beneficiaries, which we outline below.

Multiple Systems of Care Result in Deficient Care Coordination. SPDs, and dual eligibles in particular, generally do not have a single entity that coordinates the medical services and LTSS needed to maintain or improve their health status. SPDs often must act as their own care coordinator, or attempt to find someone who can assist them in making medical appointments, determining when they need to see a specialist, and identifying HCBS that may help them avoid unnecessary SNF stays.

Moreover, the multiple systems of care often use their own assessment tools to determine LTSS eligibility and benefits levels. In addition to the social worker and beneficiary time lost due to conducting multiple assessments of SPDs’ medical and daily‑living needs, the differing program assessment tools might fail to evaluate the whole person’s needs and, in some cases, deliver inconsistent results.

No Fiscal Incentives to Reduce Hospitalizations . . . In addition to contributing to a lack of coordination of services for dual eligibles, the current system creates an incentive for each program to “cost shift.” Cost shifting occurs when one entity or program takes actions that have impacts—positive or negative—on a separate entity or program. Because the impacts are not borne by the entity taking action, that entity has limited financial incentive to limit overall costs or maximize overall benefits. For example, Medi‑Cal pays for the majority of LTSS costs for dual eligibles, but a relatively small portion of the costs of hospitalizations, which are paid primarily by the federal government under Medicare. Therefore, the state has limited financial incentive to provide additional LTSS that would potentially reduce hospital utilization for dual eligibles, since the savings resulting from avoided hospitalizations would largely accrue to the federal government.

. . . Or SNF Placements. Cost‑shifting is similarly present within Medi‑Cal when different Medi‑Cal benefits are administered by different entities. For example, counties, which administer and partially fund IHSS, do not receive any financial benefit if the services they provide decrease SNF and hospital utilization. This is because, to the extent savings are achieved in SNFs and hospitals, they are realized by the state and federal government, not by the counties. This lack of a fiscal incentive could lead to an overutilization of SNF care, which increases overall costs for the state and adversely impacts beneficiaries who prefer to stay in the community.

CCI Intended to Improve Care and Reduce Costs

In 2012‑13, in response to concerns with the fragmented system of care and misaligned financial incentives described above, the state implemented the CCI. The CCI is a joint state‑federal demonstration project designed to reduce the fragmentation of care for Medi‑Cal and Medicare beneficiaries, thereby improving health care and long‑term care while potentially reducing Medi‑Cal and Medicare costs for the SPD population. The CCI mostly made changes that apply to the counties participating in the demonstration project, known as the “demonstration counties.” While originally intended to be implemented in eight counties, seven counties ultimately participated. The seven CCI demonstration counties are Los Angeles, Orange, Riverside, San Bernardino, San Diego, San Mateo, and Santa Clara.

Policy Changes in Demonstration Counties

The CCI made the following major policy changes in the seven demonstration counties:

- Integration of Medi‑Cal and Medicare Benefits Under Cal MediConnect. The CCI enabled dual eligibles to receive their Medicare benefits through the same Medi‑Cal managed care plans that provide their Medi‑Cal benefits. This component of the CCI is known as Cal MediConnect. Initially, dual eligibles were passively enrolled in Cal MediConnect health plans, meaning they were automatically enrolled in Medi‑Cal managed care plans for their Medicare and Medi‑Cal benefits unless they made the initial choice to opt out. Passive enrollment began in 2014 and ended in 2016. Once enrolled in a Cal MediConnect health plan, enrollees are free to opt out in any given month and return to receiving their Medi‑Cal and Medicare benefits through separate systems of care.

- Mandatory Enrollment of Dual Eligibles in Medi‑Cal Managed Care. The CCI requires most dual eligibles in the seven demonstration counties to enroll in managed care plans to access their Medi‑Cal benefits, including their LTSS benefits. Because participation in Cal MediConnect is optional, dual eligibles mandatorily enrolled in Medi‑Cal managed care may continue to receive their Medicare benefits, such as doctor visits and hospitalizations, separately.

- Integration of LTSS Under Medi‑Cal Managed Care. In addition to authorizing the duals demonstration, the CCI shifted SNF, IHSS, CBAS, and MSSP benefits from Medi‑Cal FFS to Medi‑Cal managed care for most dual eligibles and Medi‑Cal‑only SPDs.

- State‑Level Collective Bargaining for IHSS Providers. The CCI transitioned collective bargaining over IHSS provider wages and benefits from the local level to the state, creating an entity known as the California IHSS Authority, or Statewide Authority, for the demonstration counties.

- Universal Assessment. The CCI established a stakeholder workgroup to develop a universal assessment tool that would be piloted in select counties to assess for IHSS, CBAS, and MSSP. The workgroup was tasked with building on the IHSS assessment process, the MSSP assessment process, and other appropriate HCBS assessment tools to develop a single assessment tool that could be used to determine a person’s level of need for all three HCBS programs.

Managed Care Rate Structures Under the CCI. The CCI required a new financing structure for Medi‑Cal managed care because of the incorporation of new Medi‑Cal and potentially Medicare benefits under Medi‑Cal managed care. What was ultimately adopted were two separate rate structures—one for Medi‑Cal‑only SPDs who were required to receive LTSS through managed care under the CCI and the second for dual‑eligibles, regardless of whether they were enrolled in Cal MediConnect.

- Managed Care Rates for Medi‑Cal‑Only SPDs. For Medi‑Cal‑only SPDs in CCI counties, Medi‑Cal managed care plans are paid higher capitated rates that incorporate the FFS costs of their enrollees’ major LTSS. Because the managed care plans are paid the actual FFS costs of the long‑term care services (which include SNF placements) their enrollees utilize, they are not generally placed at risk for higher or lower utilization and therefore have limited financial incentive to actively manage these LTSS benefits.

- Managed Care Rates for Dual Eligibles. The structure of managed care rates for dual eligibles differs significantly from the structure for Medi‑Cal‑only SPDs receiving their LTSS benefits under Medi‑Cal managed care. Managed care plans are paid risk‑based, capitated payments for dual eligibles (with the exception of payments for IHSS, discussed below), which provide some incentive for the plans to encourage preventive health care and home‑ and community‑based LTSS in favor of hospitalizations and SNF placements for their members. In addition, managed care capitated rates for dual eligibles include efficiency factors, which means the rates are reduced by certain percentages to account for savings that managed care plans are expected to achieve through more effective management of their members’ health care and LTSS utilization.

Limited Integration of IHSS Financing Under Managed Care. Regardless of whether an SPD in a CCI county is enrolled in Cal MediConnect, IHSS practically remained an FFS Medi‑Cal benefit under the CCI. While payment for IHSS is included in Medi‑Cal managed care plans’ per member per month payments, the IHSS payment corresponds to the costs of the service rather than as a risk‑based capitated payment that places the managed care plan at risk and provides an incentive for the plan to appropriately manage the benefit. Counties retained administrative control over the IHSS benefit—continuing to determine eligibility and assess recipients for their service needs. As a result, managed care plans were not given authority to actively manage the IHSS benefit under the CCI. While financing did not change, increased care coordination between managed care plans and county welfare departments has been reported.

Statewide Policy Change

County IHSS MOE Replaced Counties’ Share of IHSS Program Costs. The CCI replaced counties’ share of IHSS program costs (historically 35 percent of the nonfederal portion of costs) with a maintenance‑of‑effort, known as the county IHSS MOE. Effective July 1, 2012, all counties were required to maintain their 2011‑12 expenditure levels for IHSS, to which an annual growth factor of 3.5 percent was applied in subsequent years. Added to the growth factor were any IHSS costs associated with locally negotiated IHSS wage increases. The state General Fund assumed the remaining nonfederal IHSS costs.

Poison Pill Provision

Elimination of CCI if the Demonstration Does Not Result in Net General Fund Savings. The CCI contains a poison pill provision that automatically discontinues all components of CCI (including changes in demonstration counties and the IHSS MOE) if the DOF determines that the CCI does not generate net General Fund savings and is therefore not “cost‑effective.” The DOF assesses the net General Fund savings by conducting a CCI savings analysis by January 10 of every fiscal year in which the CCI is in effect. While the CCI statute mandates the inclusion of certain components within the CCI savings analysis, the statute generally gives DOF broad discretion in estimating the costs and savings of the CCI.

Back to the TopCCI Results and Challenges to Date

CCI implementation began in 2012‑13. The potential benefits of the CCI are more long term in nature. As such, three years of experience under the CCI is insufficient to provide a full assessment of the merits of the enhanced health care and LTSS coordination. Nevertheless, the CCI appears to be achieving some initial, positive results, while also experiencing a number of challenges, both of which we outline below.

Some Policy Benefits Realized, While Challenges Continue

Cal MediConnect Has Shown Initial Promise in Reducing Hospitalizations and SNF Placements. A principal intent of the CCI is to improve care and reduce costs by avoiding unnecessary hospitalizations and SNF placements. Based on analyses carried out by participating managed care plans, between April 2014 and June 2016, Cal MediConnect has helped achieve reductions in hospital and SNF utilization. Managed care plans have reported making use of enhanced care coordination as well as HCBS to help SPDs avoid unnecessary SNF stays and hospitalizations. Because SNF stays and hospitalizations are, on average, so costly compared to HCBS, these avoided SNF placements and hospitalizations have potentially resulted in savings for the state and federal governments and for managed care plans.

Relatively High Cal MediConnect Member Satisfaction. A 2016 beneficiary satisfaction survey jointly carried out by the University of California, Berkeley and the University of California, San Francisco compared the experiences of Cal MediConnect members, dual eligibles who opted out of Cal MediConnect, and dual eligibles in non‑CCI counties. In general, the survey shows relatively high satisfaction on the part of Cal MediConnect members. Cal MediConnect members, for example, were more likely than nonmembers to know they have someone coordinating their care, to report that the quality of their care has improved since the CCI began, and to not have unmet needs for personal care assistance. The survey also showed there is room for continued improvement. For example, the survey identified some disruptions in the continuity of care during the transition to Cal MediConnect.

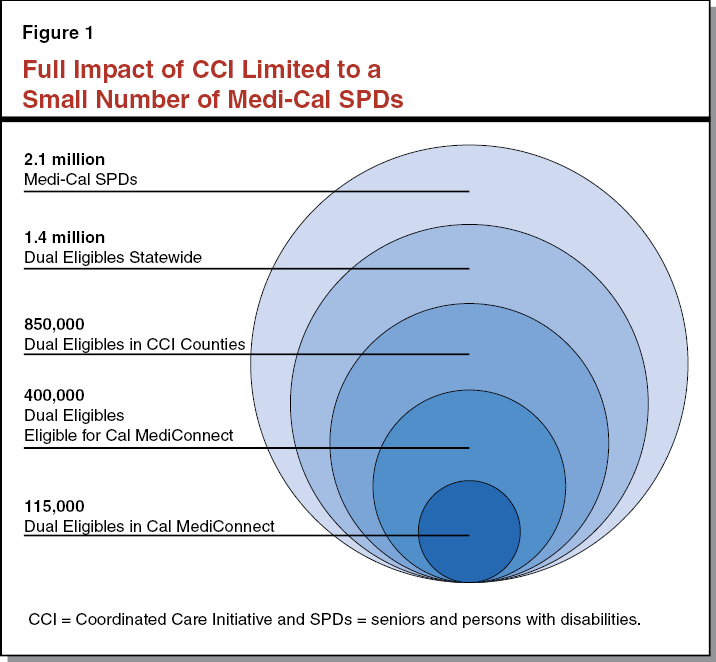

Opt Outs From Cal MediConnect an Ongoing Challenge. Enrollment in Cal MediConnect has fallen short of the state’s initial goals. While we estimate that over 400,000 dual eligibles live in CCI counties and are eligible for Cal MediConnect, only about 115,000 are enrolled. (The number of opt outs was significant both during and after the passive enrollment phase, in particular for Medi‑Cal enrollees who utilize IHSS.) Moreover, state law excludes certain dual eligibles from participating in Cal MediConnect—for example, dual eligibles living in rural areas are excluded from participation—and caps participation in Los Angeles County to 200,000 members. These restrictions, combined with disenrollments, have resulted in Cal MediConnect serving only a small subset of the 850,000 dual eligibles who live in CCI counties. Figure 1 shows the small proportion of SPDs in Medi‑Cal statewide who, for multiple reasons, are enrolled in Cal MediConnect.

Since savings from the CCI depended in large part on the improved outcomes achievable through Cal MediConnect, low enrollment in Cal MediConnect was a factor that decreased the CCI’s potential to generate savings. Over the last six months, the state has made efforts to streamline Cal MediConnect enrollment by allowing managed care plans to directly enroll their members into Cal MediConnect, should their members choose to opt in. Previously, dual eligibles hoping to enroll in Cal MediConnect had to take the extra step of enrolling through their managed care plan and the Department of Health Care Services (DHCS). The state and managed care plans are reporting that streamlined enrollment has resulted in improved Cal MediConnect enrollment.

CCI Has Improved Collaboration Between Managed Care Plans and the IHSS Program . . . Prior to the CCI, managed care plans had limited experience with HCBS, such as IHSS. As such, it has taken time for these plans to develop relationships with LTSS providers and understand how these programs can best be utilized to reduce hospital and SNF costs. While coordination between managed care plans and IHSS program administrators has been reported as being slow to start in the first half of the demonstration period, considerable improvements in coordination between the two systems of care over the second half of the demonstration period have been reported. For example, at least one managed care plan has begun colocating county IHSS staff at the plan to allow improved communication, coordination, and mutual learning. Over the course of the CCI, the same plan reported a reduction from 120 days to 30 days in the amount of time it takes for a potential recipient to receive an IHSS eligibility and service needs assessment, aiding the managed care plan’s efforts to ensure that HCBS are available when the beneficiary needs them. Other benefits that came out of the improved coordination between IHSS county administrators and managed care plans under the CCI include an increase in referrals to IHSS from managed care plans, suggesting better identification of beneficiaries who could benefit from IHSS services.

Moreover, as a part of the CCI, the state funded county IHSS social workers to participate in interdisciplinary care team meetings that included managed care plans and IHSS providers as a means of improving care coordination for IHSS recipients’ health care services and LTSS. As a result of these team meetings, some IHSS recipients experienced an increase in authorized IHSS hours and expedited assessments.

. . . But the Benefits and Trade‑Offs of a Fuller Integration Were Not Tested. As we have pointed out, by design, the integration of IHSS as a managed care benefit was limited under the CCI. This is primarily because making the IHSS program a managed care benefit presents several unique challenges due to the administrative and programmatic structure of IHSS. As a result, the CCI to date has not tested the potential merits and trade‑offs of an IHSS program that is more fully integrated within managed care. For example, under the CCI, county social workers continued to assess IHSS recipients for eligibility and their level of need for service hours. A fuller integration would have granted more authority to managed care plans to assess recipients to determine IHSS service hours in order to allow them to better manage their financial risk for long‑term care. For example, plans could have used this authority to immediately ramp up service hours for recipients who may need increased hours following a hospital stay. There would have been trade‑offs, however, associated with a more integrated IHSS program that were not tested under the CCI program. For example, at the time the CCI was introduced, managed care plans had very limited experience in conducting functional need assessments for this type of nonmedical program, and it is unknown how they would have handled this new responsibility.

IHSS MOE Has Had a Major Fiscal Impact on State and Counties

IHSS MOE Resulted in Significant New General Fund IHSS Costs. The IHSS MOE has had a major impact on General Fund costs for the IHSS program. Under the IHSS MOE, county costs that exceeded the fixed 3.5 annual growth factor (plus the cost of locally negotiated wages) were shifted to the General Fund. Over the five years in which the IHSS MOE was in effect, the shift of IHSS costs from counties to the General Fund significantly increased, from an initial estimated $36 million in 2012‑13 to an estimated $558 million in 2016‑17. (We note that the administration is currently updating these estimates to reflect actual costs.) As shown in Figure 2 (see next page), the General Fund was responsible for an increasing share of IHSS nonfederal costs under the IHSS MOE. In addition to the IHSS MOE, a number of other factors, including state and federal policy changes, have contributed to the increasing IHSS General Fund cost growth. (Please see the box below for more information on the major drivers of recent increases in IHSS state costs.)

Total IHSS Program Costs Have Increased Significantly in Recent Years

Federal and State Policies Have Greatly Contributed to Increasing General Fund IHSS Cost Growth. Since the maintenance‑of‑effort (MOE) was instituted, the General Fund has borne an increasing share of In‑Home Supportive Services (IHSS) program costs, growing from $1.7 billion in 2012‑13 to an estimated $3.5 billion in 2016‑17. In addition to the IHSS MOE, natural program caseload growth and other state and federal policies contributed to the increased growth in overall program costs and thus General Fund IHSS program costs:

- Implementation of Federal Labor Regulations. In February 2016, in response to new federal labor regulations, the state implemented overtime pay and newly compensable work activities (travel time and accompaniment to medical appointments). Revised estimates indicate that the implementation of the new federal regulations represents roughly 30 percent of the growth in General Fund IHSS expenditures from 2014‑15 to 2015‑16. (For more information on the implementation of the new federal labor regulations for IHSS providers, see the online post, The 2017‑18 Budget: Analysis of the Human Services Budget.)

- Restoration of IHSS Service Hours. In 2013, the Legislature approved a 7 percent reduction in each IHSS recipient’s authorized service hours, effective July 1, 2014. In 2015‑16, the Legislature provided about $240 million from the General Fund to restore service hours from the previously enacted 7 percent reduction. We estimate that the initial costs to restore IHSS service hours accounted for about one‑quarter of the growth in General Fund IHSS expenditure from 2014‑15 and 2015‑16.

- Wage Increases. IHSS provider wages generally increase in two ways—(1) increases that are collectively bargained at the local level and (2) increases that are in response IHSS‑related state minimum wage increases. In 2015‑16 and 2016‑17, the IHSS program experienced both of these types of growth in wages. Between 2011‑12 and 2014‑15, the average wage for IHSS workers increased from $9.75 to $10.30 (6 percent). Between 2014‑15 and 2016‑17, average wages are estimated to grow from $10.30 to $11.45 (11 percent).

- Caseload Increases and Increases in the Average Hours Per Case. Recent growth in caseload and hours per case have exceeded historical growth rates (about 2 percent in annual growth for the past ten years). However, although elevated, the recent average annual growth in caseload (5 percent) and hours per case (6 percent) account for less than 10 percent of the General Fund growth in IHSS costs between 2015‑16 and 2016‑17.

Additional IHSS Cost Pressures on the Horizon. Minimum wage increases will continue to drive IHSS costs as more counties experience increased IHSS wages due to future scheduled state minimum wage increases. Additionally, the federal requirements to develop an electronic time sheet verification system by 2019 and state requirements to implement paid sick leave for IHSS providers in 2018‑19 present additional cost pressures for General Fund IHSS expenditures in the out years.

IHSS MOE Reduced Growth in Counties’ IHSS Costs. County IHSS program costs have increased at an average rate of around 4 percent annually under the IHSS MOE. Moreover, as shown in Figure 2, under the IHSS MOE counties paid a smaller share of IHSS nonfederal costs (24 percent), relative to the historical 35 percent of IHSS nonfederal costs. As a result, over the lifetime of the IHSS MOE, counties’ costs for IHSS were hundreds of millions of dollars lower than they would have otherwise been under the cost‑sharing ratios of 1991 realignment.

Figure 2

Increasing Use of General Fund for IHSS Program Under County IHSS MOE

(Dollars in Millions)

|

2011‑12a |

IHSS County MOE |

2017‑18a |

|||||

|

2012‑13 |

2013‑14 |

2014‑15 |

2015‑16 |

2016‑17 |

|||

|

Total IHSS Nonfederal Costs |

$2,652 |

$2,650 |

$2,879 |

$3,220 |

$3,815 |

$4,646 |

$4,933 |

|

General Fund |

1,726 |

1,706 |

1,926 |

2,215 |

2,737 |

3,529 |

3,154 |

|

County |

926 |

945 |

953 |

1,005 |

1,078 |

1,117 |

1,779 |

|

Share of Nonfederal Cost |

|||||||

|

General Fund |

65% |

64% |

67% |

69% |

72% |

76% |

64% |

|

County |

35 |

36 |

33 |

31 |

28 |

24 |

36b |

|

aReflects established state‑local cost‑sharing relationships for IHSS when the Coordinated Care Initiative, and thus the IHSS MOE, was not operative. bCounty ratio includes higher county costs related to wages and benefits above $12.10 per hour and other IHSS programmatic costs, resulting in a slightly higher county share of nonfederal costs than the statutory rate of 35 percent. |

|||||||

|

Note: 2016‑17 and 2017‑18 reflect estimates from the 2017‑18 Governor’s budget proposal. |

|||||||

|

IHSS = In‑Home Supportive Services and MOE = maintenance‑of‑effort. |

|||||||

Absent IHSS MOE, Counties Would Have Faced Higher Costs. Historically, 1991 realignment revenue generally has covered counties’ costs for the realigned programs. Had the IHSS MOE not been in place over the past five years, however, counties would have had to pay the increased IHSS costs borne by the General Fund since 2012 ($558 million in 2016‑17). The revenue available from 1991 realignment would have been able to cover about one‑third—or roughly $200 million—of these increased costs. To make up the difference, counties would have had to make cuts to realigned social services programs and/or use local general fund revenues to cover the remaining IHSS costs. Given these significant impacts on counties, the state likely would have taken actions to mitigate the effects—such as by limiting counties’ exposure to rising program costs.

Under IHSS MOE, Other Realignment Programs Received Increased Funding. Due to the IHSS MOE, much of the roughly $200 million in realignment funding that would have supported increased IHSS costs instead went to other realigned programs. In particular, other social services programs (such as Child Welfare and the California Work Opportunity and Responsibility to Kids [CalWORKs] program), health, and mental health received increased funding. In addition, the state redirected a portion of the funds to support CalWORKs grant increases that absent the IHSS MOE likely would not have been feasible within the 1991 realignment fiscal structure. (We discuss these changes and the fiscal implication of the IHSS MOE in greater detail in the Appendix.)

Back to the TopGovernor’s Proposal

The Governor’s 2017‑18 budget terminates the CCI but proposes a two‑year continuation of major CCI components. We detail the administration’s actions and CCI proposal below. Despite the termination of the CCI, the administration has communicated that it encourages counties and managed care plans to continue to work together to coordinate the IHSS benefit. In addition, the administration has recognized the fiscal challenges that ending the IHSS MOE presents to counties and has signaled an intent to work with counties to mitigate these fiscal challenges.

Administration Terminates CCI Pursuant to Poison Pill Provision . . .

Administration Determined That the CCI Does Not Generate Net General Fund Savings. In conjunction with the release of the Governor’s 2017‑18 budget, the DOF has estimated that the CCI will generate net General Fund costs of $278 million in 2016‑17 and $42 million in 2017‑18.

IHSS County MOE Was the Primary Factor in the Administration’s Determination. The primary reason the CCI has been determined not to result in net General Fund savings is the IHSS MOE, which, as we previously discussed, transferred significant cost growth in the IHSS program from counties to the General Fund. Because of the IHSS MOE, General Fund spending in 2016‑17 on IHSS is almost $600 million higher than it would have been under the former state‑county cost‑sharing rules. Savings from other components of the CCI savings calculation did not fully offset the increases in General Fund spending resulting from the IHSS MOE (and other, less significant cost pressures under the CCI), leading to the administration’s determination that the CCI does not generate net General Fund savings.

Determination Automatically Ends the CCI. In accordance with state law, the DOF’s determination that the CCI does not generate net General Fund savings automatically ends the program. The administration does not need the Legislature’s approval to terminate the program.

. . . But Proposes Continuation of Major Components of the CCI

Recognizing the merits of the policy goals behind the CCI, the Governor’s budget proposes the continuation of major components of the CCI. Although budget‑related legislation detailing the Governor’s proposal is not yet available, we understand that the Governor is proposing the continuation of (1) Cal MediConnect, (2) mandatory enrollment in managed care for dual eligibles, and (3) integrated LTSS other than IHSS under managed care. Continuation of any components of the CCI will require statutory authorization from the Legislature. In Figure 3, we summarize the timeline for when the various major components of the CCI become inoperative under current law given the January 2017 determination by DOF that the CCI does not generate net General Fund savings. The Governor proposes to continue the following major CCI components:

- Cal MediConnect. The Governor’s budget proposes a two‑year continuation of Cal MediConnect. Without this extension, Cal MediConnect would end in January 2018.

- Mandatory Enrollment of Dual Eligibles in Managed Care for Their Medi‑Cal Benefits. The Governor’s budget proposes a two‑year extension of mandatory enrollment in Medi‑Cal managed care for dual eligibles’ Medi‑Cal benefits. Without this extension, this component of the CCI would end in January 2018.

- Integration of LTSS Other Than IHSS Under Medi‑Cal Managed Care. The Governor’s budget proposes to continue the integration of LTSS other than IHSS under Medi‑Cal managed care. This would include SNF care, CBAS, and MSSP. The Governor proposes to delay the integration of MSSP under managed care from January 2018 to January 2020.

Figure 3

Timeline of When Major CCI Policies Become Inoperative Under Current Lawa

|

January 2017 |

Return of responsibility for bargaining for IHSS wages and benefits to the CCI counties. |

|

End of development of home and community‑based services universal assessment tool. |

|

|

July 2017 |

Elimination of IHSS Maintenance‑of‑Effort and return to historical IHSS state‑county cost‑sharing ratio. |

|

January 2018 |

Disenrollment of members from Cal MediConnect.b |

|

End of mandatory managed care enrollment for dual eligibles.b |

|

|

Removal of IHSS financing from managed care. |

|

|

aGiven the January 2017 determination by the Department of Finance that the CCI does not generate net General Fund savings. bThese are elements we expect to be proposed for continuation under the Governor’s proposal. |

|

|

CCI = Coordinated Care Initiative and IHSS = In‑Home Supportive Services. |

|

Removal of IHSS From the CCI

By eliminating the CCI but proposing to continue certain CCI components, the Governor would effectively remove the IHSS components from the demonstration. This would result in the following changes:

- Restoration of the Historical State‑County IHSS Cost‑Sharing Arrangement. As they did prior to the IHSS MOE, counties will pay 35 percent of nonfederal IHSS program costs and the state will pay the remaining 65 percent beginning July 1, 2017. The DOF estimates that this will transfer approximately $600 million in IHSS costs from the General Fund to the counties in 2017‑18.

- Termination of State‑Level Bargaining for IHSS Provider Wages and Benefits. Bargaining for IHSS wages and benefits in CCI counties reverts from the state to the counties. Since no agreements for increased wages were negotiated or approved by the Statewide Authority, all IHSS bargaining responsibilities have already shifted back to the seven CCI counties.

- End of Development of Universal Assessment Tool. Efforts to develop a universal assessment tool have ended. To date, a full universal assessment tool has not been constructed or piloted, although the workgroup established by the CCI has carried out significant work in the early development of the tool.

- Elimination of Funding for Care Coordination. The Governor’s budget proposal eliminates funding that was provided under the CCI for IHSS social workers to participate in interdisciplinary team meetings that included managed care plans and IHSS providers. Although funding is eliminated, the administration has stated that it intends to “encourage” continued coordination between managed care plans and the IHSS program.

LAO Assessment of Governor’s Proposal

Finding That the CCI Does Not Generate Net General Fund Savings

Determination Follows Statute. Overall, the DOF’s methodology for determining whether CCI generates net General Fund savings appears in line with statute and generally accounts for the full set of policy changes that were included in the final CCI legislative package. As we previously discussed, the CCI’s poison pill statute gave the DOF fairly broad discretion to conduct the CCI savings analysis. The DOF established a methodology for the CCI savings analysis and maintained use of the same overall methodology through January 2017. As we discuss below, however, the determination that the CCI does not generate net General Fund savings is not indicative of certain components of the CCI’s potential to reduce costs and/or achieve better outcomes for the state’s SPDs.

Cost Determination Not Reflective of Certain CCI Components’ Potential to Achieve Programmatic Savings. While the administration determined that the CCI does not generate net General Fund savings, the methodology used by DOF, though generally reasonable, includes factors that are not necessarily related to whether or not the integration of health care and LTSS under managed care can generate programmatic savings. As previously discussed, DOF included in the CCI savings analysis the statewide costs associated with the IHSS MOE—the primary factor in DOF’s determination that the CCI does not generate net General Fund savings. However, a statewide IHSS MOE is not an essential policy component in the integration of health care and LTSS under Medi‑Cal managed care, particularly when the demonstration is limited to certain counties. As such, integrating health care and LTSS remains a promising strategy to reduce the programmatic costs of caring for the state’s SPDs.

Governor’s Proposal to Extend Major Components of the CCI

Integration of Health Care and LTSS Remains a Worthy Policy Goal. As the administration recognizes by proposing to continue parts of the CCI, the integration of health care and LTSS remains a worthy policy goal that we believe the state should continue to pursue. As previously discussed, there are early positive signs related to care coordination and potentially related reduced costs under the CCI, and more time is needed to fully evaluate the outcomes achieved by the CCI.

Proposal Will Allow Dual Eligibles to Maintain Joint Medi‑Cal and Medicare Coverage Through Cal MediConnect. Based on our understanding, the Governor’s proposal to continue Cal MediConnect will allow the state to continue to test the integration of Medicare and Medi‑Cal and prevent Cal MediConnect members from experiencing a disruption in their care. It is our understanding that without a continuation of Cal MediConnect, dual eligibles in Cal MediConnect would be automatically disenrolled from Medi‑Cal managed care for the Medicare portion of their benefits.

Proposal Will Preserve the Financial Alignment of Medi‑Cal and Medicare Under Cal MediConnect. Cal MediConnect was established, in part, to improve financial alignment by preventing cost shifting between Medicare and Medi‑Cal. Cost shifting can occur outside of Cal MediConnect because Medicare is largely financially responsible for health care while Medi‑Cal is primarily financially responsible for LTSS. This results in Medicare, for example, bearing the costs but none of the benefits of providing preventive health care that helps an SPD avoid SNF placements. Because, under Cal MediConnect, Medi‑Cal managed care plans are financially responsible for their dual eligible members’ health care and certain LTSS, the plans bear the costs and benefits of preventive care that reduces more costly institutionalizations. The continuation of Cal MediConnect will preserve the financial alignment created under Cal MediConnect.

Integration of LTSS Under Managed Care Retains Some Promise Despite Removal of IHSS. Care in SNFs would remain a managed care benefit for most dual eligibles and SPDs in CCI counties, as opposed to becoming a benefit that is accessed through the Medi‑Cal FFS delivery system. By continuing the partial integration of LTSS under managed care, managed care plans should continue to gain experience in coordinating this benefit for their members.

Proposal to Remove IHSS Financing From Managed Care Will Have Limited Impact on Recipients and Providers. Despite the CCI’s new financing arrangement related to IHSS, IHSS effectively remained a Medi‑Cal FFS benefit under the administrative control of county welfare agencies. (In CCI counties, the FFS costs of enrollees’ IHSS benefits were added to managed care plans’ monthly capitated payments.) While there have been reports of improvements around IHSS care coordination between managed care plans and county welfare agencies, IHSS was not in essence converted into a managed care benefit under the CCI. (It should be noted that this result was by the design of the CCI authorizing statute.) As a result, for most IHSS recipients in CCI counties, the IHSS program would generally operate the same as prior to and during the CCI if its financing is removed from managed care in January 2018, consistent with the Governor’s proposal. The primary change will be that the FFS costs of IHSS recipients’ IHSS benefits will no longer be added to managed care plans’ monthly capitated payments before being passed on to counties for the full costs of administering the benefit. Removing IHSS financing from managed care does not change the fact that county welfare agencies will continue to have administrative control over IHSS. However, it is important to note that some of the benefits of increased care coordination described earlier might not continue.

Elimination of the IHSS MOE

Below, we summarize the major implications of ending the IHSS MOE and returning to the historical state‑county cost‑sharing arrangement. We provide additional detail in Section 3 of the Appendix.

Ending the IHSS MOE Provides Significant Relief for the General Fund While Significantly Increasing Costs for Counties. Specifically, by returning to the 1991 realignment cost‑sharing ratios, counties’ 2017‑18 costs for IHSS will increase by the same amount of General Fund savings (over $600 million).

1991 Realignment Revenues Will Not Be Sufficient to Pay for Counties’ Increased IHSS Share of Cost. The revenues that fund counties’ IHSS program costs under 1991 realignment will not be sufficient to cover the increases in IHSS county costs—creating immediate and ongoing challenges for counties in the hundreds of millions of dollars. (There will be other implications of the increased county costs in IHSS resulting from the elimination of the IHSS MOE. We discuss this further in Section 3 of the Appendix.)

Back to the TopShould the Legislature Adopt the Governor’s Proposal?

We believe that the Governor’s proposal to continue major components of the CCI is appropriate. Actions taken to date toward coordinated care and the alignment of financing for health care and LTSS have been steps in the right direction and, accordingly, we are supportive of the Governor’s proposal to continue components of the CCI that can achieve these aims.

Absent from the Governor’s proposal, however, is a plan to mitigate the fiscal effects on counties resulting from the termination of the IHSS MOE. The administration has signaled an intent to work with counties to provide some form of relief to the fiscal challenges resulting from the elimination of the IHSS MOE. There are a number of issues for the Legislature to consider in returning to the 1991 realignment cost shares. We outline these considerations below, and note that the state‑county fiscal relationship is worthy of reexamination, whether or not the Legislature accepts the Governor’s proposal in whole.

The Governor’s proposal also presents an opportunity to consider whether the state should test a continued and potentially enhanced service‑integration pilot. As we highlighted earlier, the CCI did not fully integrate the IHSS program within managed care. As such, we believe some level of continued or enhanced service integration, potentially including IHSS, is worthy of consideration. We outline what this could look like in the last section of the report. We also discuss how the Legislature could consider IHSS cost sharing under a reenvisioned service‑integration model.

Fiscal Considerations

This section discusses the fiscal issues for the Legislature to consider in implementing the termination of the IHSS MOE. First, we discuss options for the Legislature to consider in the short term to mitigate county fiscal challenges in 2017‑18. Second, we lay out options for long‑term changes to the cost‑sharing ratios. Each of these options—both in the short and long term—can be phased in in different ways depending on the Legislature’s priorities and counties’ ability to adjust to a new structure.

Short‑Term Considerations

Counties’ Costs Will Increase by Hundreds of Millions of Dollars in 2017‑18. As discussed earlier, returning to the 1991 realignment IHSS cost‑sharing ratio shifts hundreds of millions of dollars of costs to counties that under the IHSS MOE were paid by the General Fund in 2016‑17. Moreover, because under 1991 realignment counties are paid in arrears, the fiscal structure will not adjust for these increased costs until 2018‑19 (and even then, the funding will not be sufficient to fully cover counties’ increased share of IHSS costs). Generally, the 1991 realignment structure was designed to provide counties with sufficient resources to cover their share of costs for the realigned programs. Counties’ ability to absorb these additional costs for IHSS—outside of the 1991 realignment fiscal structure (likely from their general funds)—is limited. As a result, the administration’s determination ending the CCI, and therefore the IHSS MOE, results in immediate, significant increases in county costs that will not be covered by realignment. Absent state action, counties would have to reduce spending on 1991 realignment social services programs to the extent feasible and/or provide local general fund resources. (For more information on the 1991 realignment fiscal structure, see the Appendix.) To mitigate this fiscal effect on counties, we offer two short‑term options for the Legislature to consider:

- Provide One‑Time General Fund Relief. The Legislature could consider providing counties a one‑time grant or loan from the General Fund to cover all—or part—of the IHSS cost increase in 2017‑18. We would note that one‑time fiscal relief might not be sufficient since 1991 realignment will not adjust for these higher costs for many years.

- Provide Decreasing Levels of General Fund Relief Over a Few Years. Another option to provide some level of short‑term fiscal relief for counties would be to provide General Fund support to cover the difference between counties’ costs for IHSS and the funding available from 1991 realignment for a few years. As the growth funding available in 1991 realignment increases, the General Fund support could decline. A longer transition would provide the Legislature more time to consider changes to the 1991 realignment structure (and provide counties more time to adjust to these higher costs).

Long‑Term Considerations

Changes to the 1991 Realignment Structure. As discussed earlier (and in greater detail in the Appendix), the 1991 realignment fiscal structure will not be able to cover the costs of returning to the original cost‑sharing ratios for IHSS for many years. Some of this shortfall is due to the changes made to the realignment structure during the years the IHSS MOE was in place. Consequently, counties will have to either use their general fund resources to pay for these increased costs and/or reduce spending on social services programs to the extent feasible. Alternatively, changes could be made to the cost‑sharing ratios for IHSS.

State Policy Changes Have Increased Total IHSS Program Costs. As discussed earlier, during the time the IHSS MOE was in effect, the state made various policy decisions that increased overall IHSS program costs. Specifically, the state approved increases to the minimum wage (to a scheduled $15 per hour over a period of several years), implemented federal overtime provisions, and restored service hours that had been reduced in prior years. At the time of these changes, the state General Fund largely covered these cost increases. As such, the Legislature may want to consider changing the cost‑sharing ratio for IHSS to reflect the changes the state made to increase the level of cost for the program while the IHSS MOE was in place.

Principles for Reconsidering State‑County Cost Sharing. When considering appropriate levels of state and county cost shares for programs, fiscal responsibility for a program should be matched with the level of control over that program. Matching fiscal responsibility with the level of control gives both the state and counties an incentive to manage costs to the extent possible. The state (and federal government) have the majority of the control over eligibility and basic service provision requirements in IHSS. Counties are tasked with administering the program because they are well positioned to determine individual service‑level needs (for example, they determine the number of hours of care needed by beneficiaries) and can arguably provide easy access to services for beneficiaries. Additionally, collective bargaining for wages and benefits has historically occurred at the county level. Thus, as has been recognized since 1991 realignment, counties should share in the costs of the program, but the state should bear the majority of the costs.

Options for Changing IHSS Cost‑Sharing Ratios. We believe the Legislature may want to consider changing the 1991 realignment IHSS cost‑sharing structure, for two reasons. First, the funding provided by 1991 realignment will not be sufficient to cover counties’ increased IHSS costs under the original cost‑sharing ratio in either the short or the long term. Second, the state implemented changes to IHSS over the course of the IHSS MOE that increased costs significantly. There are various options for changing the cost‑sharing structure:

- Increase State Share to Reflect Recent Policy Changes. Given the state paid IHSS costs above the IHSS MOE when the minimum wage, overtime, and service‑hour policy changes were made, the Legislature could consider increasing the state’s share of cost to account for these policy decisions. We estimate that if the Legislature took on all the costs associated with the state minimum wage and federal overtime rules, the cost‑sharing ratio for nonfederal costs would change from 35/65 county/state to roughly 32/68 county/state in 2017‑18. (The cost‑sharing ratios would have to be adjusted as costs associated with these policies increase over time.)

- Remove Requirement for Counties to Cover Wages Above $12.10. As described earlier, counties are responsible for wage costs above $12.10 per hour. Given that under the new state minimum wage schedule, the minimum wage will increase to $12 per hour in 2019, we recommend that the Legislature change this threshold. In our view, the wage cap should be set at the statewide minimum wage in any particular year.

- Reconsider Overall 1991 Realignment Fiscal Structure. As described earlier (and in greater detail in the Appendix), the 1991 realignment fiscal structure will not generate sufficient revenue to cover counties’ share of costs for IHSS. Over the past 25 years, the programs covered by 1991 realignment have changed substantially. Rather than simply adjusting the IHSS cost‑sharing ratio, the Legislature may want to consider whether 1991 realignment has reached the end of its useful life. Not only is the system extremely complex, but also largely is based on historical caseloads that likely no longer reflect counties’ needs. Fundamentally changing the fiscal structure for these programs could take a few years. In this case, the Legislature would want to consider a short‑term mitigation strategy for counties that would account for IHSS costs during the restructuring.

Should the Legislature Enhance the Governor’s Proposal?

The Governor’s action to eliminate the CCI and proposal to extend certain CCI components presents an opportunity for the Legislature to provide its vision for how health care and LTSS should be integrated in the future. Below, we discuss ways the Legislature could enhance the Governor’s scaled‑down version of the CCI, thereby building upon the gains that have been made under the CCI.

Enhance the Existing Elements Of the Governor’s Proposal

Consider Ways to Improve Cal MediConnect Enrollment. Cal MediConnect has generated tangible benefits while also experiencing challenges, particularly around enrollment. The Legislature might consider ways to improve enrollment in Cal MediConnect, on top of the changes that have recently been made by the administration to streamline Cal MediConnect enrollment. One option the Legislature might consider is introducing ongoing passive enrollment into Cal MediConnect for Medi‑Cal managed care enrollees turning 65, the age they become eligible for Medicare. While preserving the opportunity to opt out of Medi‑Cal managed care for their Medicare benefits, this policy change would likely bring two significant benefits: (1) boost enrollment in Cal MediConnect and thereby increase potential state savings and (2) improve continuity of care for Medi‑Cal managed care enrollees who otherwise would have to take action to opt in to Cal MediConnect in order to avoid having to begin accessing their health care from an entirely new system of care (Medicare). It should be noted, however, that passive enrollment would require new dual eligibles who prefer to receive their Medicare benefits separately to take action to disenroll from Medi‑Cal managed care for their Medicare benefits. Alternatively, the Legislature might consider providing funding for outreach and engagement activities that encourage Cal MediConnect enrollment by outlining the benefits of coordinated care through Cal MediConnect. Recent outreach efforts carried out by managed care plans are reported to have had a positive effect in boosting Cal MediConnect enrollment.

Modifications to SNF Financing for Medi‑Cal‑Only SPDs Might Improve Outcomes and Generate Savings. As previously discussed, managed care plans are reimbursed for the actual costs of providing SNF care to their Medi‑Cal‑only SPDs, rather than receiving fully risk‑based capitated payments that provide plans an incentive to avoid unnecessary SNF placements. The Legislature might consider directing the DHCS to develop a new payment methodology that places managed care plans at a higher level of risk for the SNF utilization of their members. This would help expand the gains in terms of lower SNF utilization that have occurred in Cal MediConnect to the Medi‑Cal‑only side of the CCI demonstration.

Consider the Potential for IHSS Under the CCI Going Forward

Because IHSS has the potential to play a uniquely important role as a home‑ and community‑based alternative to care in an institutional setting such as a SNF, there are benefits from greater coordination of the IHSS benefit with SPDs’ other health care services and LTSS. Accordingly, removing IHSS fully from the CCI is problematic because it reverses some of the improvements in care coordination between managed care plans and county welfare departments that have been achieved under the CCI. (We again note that the administration has stated that it encourages continued coordination between managed care plans and county IHSS programs/IHSS providers, but has not proposed funding for such activities.) Instead, the Legislature might consider ways to maintain and build off the improvements in IHSS care coordination that have occurred under the CCI.

In this section, we first describe some of the trade‑offs that the Legislature would have to consider should it wish to pursue greater coordination or integration of IHSS and managed care. Second, we lay out a range of ways in which greater coordination or integration could be pursued. The range includes, on one end, providing funding to encourage continued IHSS coordination between managed care plans and county welfare agencies. On the other end, the range includes testing more robust integration of IHSS under managed care, better aligning financing and programmatic control.

Carefully Consider the Trade‑Offs of Fuller Integration. In choosing whether and how to enhance the coordination or integration of IHSS and managed care, there are a number of critical issues for the Legislature to consider at the outset. These involve difficult decisions for the Legislature, as it must balance legislative control and oversight with the desire to give managed care plans enough control to effectively manage the IHSS benefit and their associated risk. In a nutshell, fuller integration of IHSS and managed care necessarily requires giving managed care plans more administrative control while reducing counties’ control. The extent of integration deemed appropriate by the Legislature would depend on the extent of the Legislature’s willingness to cede control to managed care plans.

For instance, the Legislature would have to consider which IHSS administrative responsibilities—such as for eligibility determinations and needs assessments—would remain with counties and which would transfer to managed care plans. Should the Legislature opt for greater coordination of the IHSS benefit between county IHSS staff and managed care plans (similar to the level of coordination that occurred under the CCI), most or all IHSS administrative responsibilities would remain with the counties. Should the Legislature choose to pursue greater integration of IHSS under managed care, many or even all IHSS administrative responsibilities (such as eligibility determinations and needs assessments) would come under the control of managed care plans. As a result, greater integration would significantly reduce counties’ role in IHSS.

Moreover, the Legislature would have to consider which longstanding IHSS policies and practices should be maintained, and which IHSS policies and practices could be allowed to change, were IHSS to become a managed care benefit. For example, the Legislature would need to consider the level to which managed care plans would have the authority to adopt their own policies related to the IHSS utilization of their members, the scope of benefits, and recipients’ authority to hire and fire their IHSS providers. Alternatively, the Legislature could consider whether these policies should be governed by statute. For example, IHSS recipients are currently authorized to hire any individual who successfully completes the statutory provider enrollment process. Should the Legislature wish to preserve this aspect of the program, it could require managed care plans to do so.

Align Financing Structure With Level of County Administrative Control. As previously discussed, programmatic control is an important factor to consider in choosing a state‑county financing structure. Accordingly, if changes to current law have the effect of preserving counties’ administrative role in the IHSS program, then a county share of cost for IHSS would remain appropriate. On the other hand, if the changes result in a significant reduction of county administrative control over the IHSS program, then replacing counties’ share of IHSS costs with an alternative financing structure, such as a maintenance‑of‑effort, would make sense.

Provide Funding to Encourage Coordination Between Managed Care Plans and the IHSS Program

As previously stated, under the CCI, the state provided funding for IHSS social workers to participate in interdisciplinary care team meetings that included managed care plans and IHSS providers. In part as a result of this care coordination, some IHSS recipients received increased IHSS hours and expedited assessments at the request of their managed care plans. The Governor’s budget proposal eliminates funding for participation in interdisciplinary care team meetings, potentially reversing these improvements in care coordination that occurred under the CCI. Should the Legislature wish to enhance coordination between IHSS and managed care plans but not move towards fuller integration, it might consider continuing to fund participation by IHSS social workers in interdisciplinary care team meetings. This could preserve the improved communication between managed care plans and IHSS social workers that occurred under the CCI and continue to enhance the coordination of health care and LTSS going forward.

Test Fuller Integration of IHSS Under Managed Care

As previously discussed, managed care plans participating in the CCI were not put at direct financial risk for the IHSS utilization of their members nor were they given authority to determine their members’ level of IHSS utilization. In practice, IHSS remained a Medi‑Cal FFS benefit administered separately from managed care. This was largely due to the difficult choices that would have had to have been made in order to facilitate the integration of IHSS within managed care. As a result, the state has not had a meaningful opportunity to test what IHSS would look like as a managed care benefit. Below, we summarize two of the primary rationales for greater integration of IHSS under managed care. We then lay out how the Legislature could consider implementing various levels of IHSS integration.

Potential for Cost Shifting Remained Under CCI. As we discussed in the background of this report, maintaining IHSS as a FFS Medi‑Cal benefit administered and funded (in part) by counties separately from Medi‑Cal managed care allows for cost shifting to occur between managed care plans—responsible for health care and SNF care—and counties—responsible for the state’s principal HCBS benefit, IHSS. Integrating IHSS under managed care would more fully align the financing of institutional care and HCBS, and could encourage managed care plans to judiciously manage these benefits in ways that are potentially beneficial both for the consumer and for federal, state, and local finances. Because IHSS serves as a less costly and more consumer‑centered alternative to SNF care, and because managed care plans would be responsible for paying for either IHSS or SNF care, managed care plans would have an incentive to encourage appropriate utilization of IHSS in order to avoid potentially unnecessary SNF placements.

Managed Care Plans Lack Authority to Manage the IHSS Utilization of Their Members, Limiting Coordination Potential. As previously discussed, county welfare agencies remained responsible for carrying out IHSS needs assessments under the CCI. However, a greater role in the IHSS assessment process would allow managed care plans to better coordinate IHSS with the other health care and LTSS benefits for which they are responsible. For example, with an increased role, plans could have greater authority to ramp up IHSS hours immediately following a member’s discharge from the hospital when they might want to closely monitor the member’s recovery. Following the member’s recovery, they could then reduce IHSS hours accordingly. Under the CCI, plans did not have the ability to directly alter hours in this manner. (Plans did work with county social workers to initiate IHSS reassessments after changes in beneficiaries’ health status.)

Granting managed care plans a greater role in IHSS assessments could be done in a way that makes the referral and assessment process more streamlined and standardized. For example, managed care plans could conduct IHSS needs assessments themselves. Alternatively, requirements could be established that standardize the process by which managed care plans refer their members to the IHSS program for an assessment or reassessment. For example, new rules (and funding for counties) could be established that require a needs assessment or reassessment to occur within a time period following a request by a managed care plan. This latter requirement could help ensure that an IHSS assessment occurs quickly in response to the transition of an SPD back to the community from placement at a SNF, allowing IHSS services to be quickly established and thereby helping to ensure a successful transition back to the community.

Consider Testing Fuller Integration of IHSS Under Managed Care in Certain CCI Counties. The Legislature could consider testing fuller integration of IHSS under managed care. The Legislature might select one or more managed care plans to participate in an IHSS integration pilot based on the plan’s successful experience coordinating LTSS benefits under the CCI and the local county welfare agency’s desire to participate in an integration pilot. Fuller integration would entail (1) giving managed care plans a significant level of authority to manage the benefit and (2) paying plans risk‑based, capitated payments that incorporate the IHSS benefit. Under a test of fuller integration of IHSS under managed care, the Legislature might consider (1) how to provide oversight of and evaluate the pilot and (2) what the state and county IHSS financing responsibilities should be, both of which we describe below.