In This Report

LAO CONTACTS

Forestry and Fire, Parks, and Recycling

Cap-and-Trade, Climate Change

Water

Conservation, Conservation Corps, and Toxics

Overall Resources and Environment

February 16, 2016

The 2016-17 Budget

Resources and

Environmental Protection

Executive Summary

In this report, we assess many of the Governor’s budget proposals in the resources and environmental protection areas and recommend various changes. We provide a complete listing of our recommendations at the end of this report.

Budget Provides $9 Billion for Programs

The Governor’s budget for 2016–17 proposes a total of $9 billion in expenditures from various sources—the General Fund, various special funds, bond funds, and federal funds—for programs administered by the Natural Resources ($5.3 billion) and Environmental Protection ($3.7 billion) Agencies. This total funding level in 2016–17 reflects numerous changes compared to 2015–16, the most significant of which include (1) decreased bond spending, largely attributable to major one–time appropriations for water– and flood–related activities in the current year; (2) increased special fund spending, particularly for programs designed to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions; and (3) increased General Fund support for resources departments for debt–service costs and drought–related activities.

Governor Proposes Large Increase in Cap–and–Trade Expenditures

The Governor’s budget includes a $3.1 billion cap–and–trade expenditure plan. An estimated $1.2 billion would be continuously appropriated for specified programs consistent with current law, and $1.9 billion would be allocated among numerous agencies for programs designed to reduce GHG emissions. We find that in many cases the administration’s proposals provide limited information that the Legislature can use to prioritize among the various options for spending the auction revenues. We recommend that the administration provide additional information that can be considered in this year’s budget deliberations. We also recommend establishing an expert committee to provide guidance that would help ensure the Legislature has better information in future years.

Water Policy Continues to Be Important Focus of Budget

The budget includes several notable proposals intended to continue and extend recent efforts related to the ongoing drought and implementation of Proposition 1 (2014).

Drought–Related Funding. As described in greater detail in our recent publication, The 2016–17 Budget: The State’s Drought Response, the budget includes $323 million for drought–response efforts in 2016–17. We recommend approving most of this funding, specifically the components focused on the most urgent human and environmental drought–related needs. We further recommend requiring the administration to submit two formal reports in coming years that would provide (1) data measuring the degree to which drought response objectives were met and (2) a comprehensive summary of lessons learned from the state’s response to this drought.

Proposition 1—2014 Water Bond. The Governor’s budget includes two major new Proposition 1 spending proposals—implementing statewide water–related commitments and restoring the Los Angeles River. In our view, the proposals represent a reasonable starting place, but the specific spending levels requested for each activity are not without trade–offs. We recommend the Legislature adopt a Proposition 1 spending package that reflects its priorities.

Budget Emphasizes Infrastructure

The budget—and the California Five–Year Infrastructure Plan—includes multiple significant new infrastructure proposals for resources departments.

California Conservation Corps (CCC) Residential Center Expansion. The Governor’s budget for 2016–17 proposes $400,000 from the General Fund to fund the acquisition phase for three residential centers. This represents the first stage of a major facility expansion with eight new centers identified in coming years. The administration estimates that construction of the first six centers would cost roughly $170 million (General Fund and lease revenue bonds) over the next five years, yet would result in only a modest increase of 220 total corpsmembers. We recommend approval of acquisition phase funding for the Ukiah center which would replace an existing center, but recommend that the Legislature defer approval of any other centers until CCC provides more information about expansion–related benefits.

Deferred Maintenance. The budget includes $187 million from the General Fund for deferred maintenance of state facilities managed by resources departments. While the proposal addresses an important state need for these departments, the proposal lacks important details necessary for legislative oversight. We recommend the Legislature require the administration to submit specific lists of projects that would be undertaken before approving the requested funding, as well as require departments to report on the causes of and planned strategies for addressing their deferred maintenance backlogs.

Opportunities for Legislative Oversight

In addition to the issues above, the Governor’s budget raises several issues that we believe merit greater legislative oversight. We recommend the Legislature take steps to ensure that the proposals are likely to be consistent with its priorities.

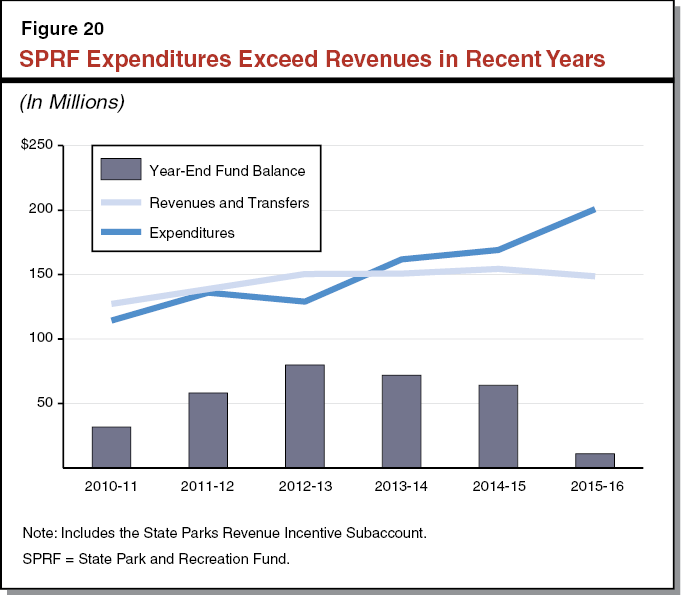

Motor Vehicle Fuel Account Transfer to State Parks. We find that the budget proposal to provide another one–time augmentation to maintain the Department of Parks and Recreation’s current operations level makes sense, but the Legislature will want to make a policy decision regarding whether to fund such an augmentation from a special fund benefiting off–highway vehicle recreational users or the General Fund. We also recommend the Legislature require the department to report on the status of various budgetary and programmatic reforms at budget hearings this spring.

Environmental License Plate Fund (ELPF). The Governor’s budget provides a package of options for addressing the ELPF structural deficit, including shifting some programs to General Fund support, raising the personalized license plate fee, and creating a new fee for those seeking certain environmental permits. We find that the administration’s approach is reasonable, but the Legislature also should consider other available options and approve a funding package based on its priorities for where spending reductions or fee increases should be borne.

Overview of Governor’s Budget

Governor’s Budget Proposal

Total Proposed Spending of $9 Billion in 2016–17. The Governor’s budget for 2016–17 proposes a total of $9 billion in expenditures from various sources—the General Fund, various special funds, bond funds, and federal funds—for programs administered by the Natural Resources and Environmental Protection Agencies. Specifically, the budget includes $5.3 billion for resources departments and $3.7 billion for environmental protection departments.

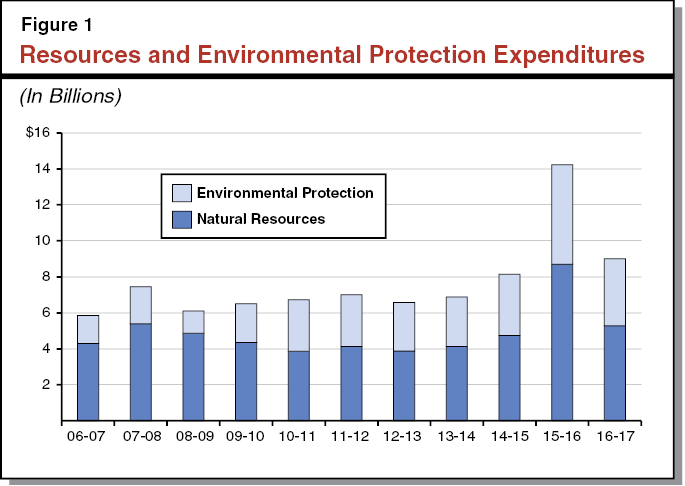

Budget Reflects Growth Since Recession. As shown in Figure 1, total spending for resources and environmental protection programs had stayed between about $6 billion and $7 billion from 2008–09 through 2013–14. Since then, these programs have experienced significant increases with actual expenditures of about $8 billion in 2014–15, estimated expenditures of over $14 billion in 2015–16, and $9 billion proposed for 2016–17. This growth has been driven by several factors, including General Fund spending on costs for fighting wildfires and debt service for general obligation bonds, as well as spending of special fund revenues to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions.

Reduction in Budget Year Largely Reflects Lower Bond Expenditures. The proposed budget reflects a decrease of $5.2 billion, or 37 percent, below estimated expenditures for the current year. This reduction in proposed spending is mostly related to spending from bond funds. Specifically, the budget proposes bond expenditures of $538 million in 2016–17 for resources and environmental protection departments, a decrease of $5.4 billion, or 91 percent, from estimated bond expenditures in 2015–16. Much of this decrease reflects two factors. First, in 2015 (as part of the 2015–16 budget and separate legislation), the Legislature made significant new bond appropriations, including $2.1 billion from Proposition 1 (2014) for water–related projects and $1.1 billion from Proposition 1E (2006) for flood control projects. Second, some of the apparent budget–year decrease is related to how bonds are accounted for in the budget, making year–over–year comparisons difficult. Specifically, bond funds that were appropriated but not spent in prior years are assumed to be spent in the current year. The 2015–16 bond amounts will be adjusted in the future based on actual expenditures.

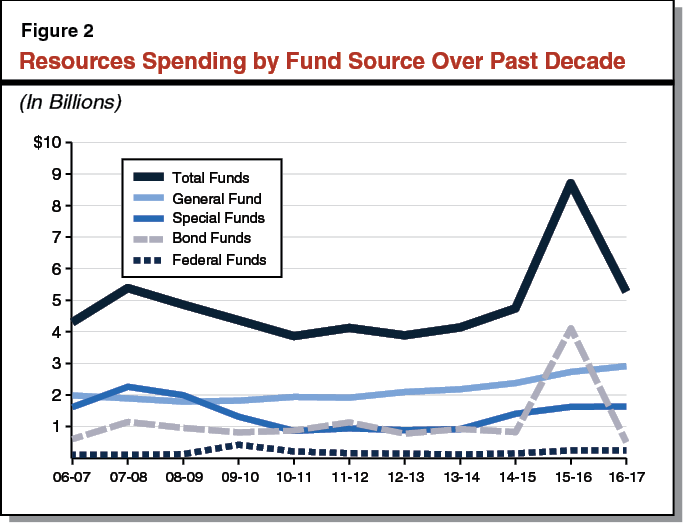

Resources Programs

Budget Continues Modest General Fund Increases for Resources Departments. Figure 2 shows spending by fund source for all resources departments since 2006–07. Aside from the current year, which included significant increases in bond funds (discussed above), about half of resources spending has come from the General Fund in recent years. The Governor’s budget for 2016–17 continues a recent trend of increasing General Fund expenditures, providing an additional $179 million from the General Fund for these departments compared to 2015–16. This General Fund increase largely reflects (1) increased general obligation bond costs ($75 million), (2) an increase in drought–related funding for the Department of Water Resources (DWR) and the Department of Fish and Wildlife (DFW) ($65 million), and (3) a new proposal to provide California Energy Commission (CEC) with funding to conduct climate change research in the transportation sector ($15 million). (The budget also includes a separate one–time appropriation of $187 million from the General Fund for deferred maintenance at resources facilities.) The Governor’s budget proposes no net increase in special and federal fund expenditures in the budget year.

Spending on Largest Resources Departments. Figure 3 shows spending from selected fund sources for the state’s five largest resources departments. As the figure shows, the most significant change is a large decrease—$3.2 billion—in bond funds for DWR. In addition, the proposed budget includes funding increases from the Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund (GGRF)—totaling $322 million—for the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection (CalFire), DFW, and CEC to implement and expand programs designed to reduce GHG emissions in the state.

Figure 3

Budget Summary for Largest Resources Departments—Selected Funding Sources

(Dollars in Millions)

|

Department |

2014–15 Actual |

2015–16 Estimated |

2016–17 Proposed |

Change From 2015–16 |

|

|

Amount |

Percent |

||||

|

Water Resources |

|||||

|

General Fund |

$123 |

$106 |

$153 |

$47 |

45% |

|

State Water Project funds |

605 |

2,026 |

2,036 |

11 |

1 |

|

Electric Power Fund |

972 |

962 |

928 |

–33 |

–3 |

|

Bond funds |

532 |

3,420 |

252 |

–3,168 |

–93 |

|

Other funds |

33 |

25 |

84 |

59 |

237 |

|

Totals |

$2,265 |

$6,538 |

$3,454 |

–$3,084 |

–47% |

|

Forestry and Fire Protection |

|||||

|

General Fund |

$945 |

$1,291 |

$1,297 |

$6 |

0.5% |

|

Reimbursements |

427 |

453 |

477 |

25 |

5 |

|

Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund |

39 |

3 |

182 |

180 |

6,524 |

|

Public Buildings Construction Fund |

20 |

68 |

95 |

27 |

40 |

|

SRA Fire Prevention Fund |

74 |

80 |

76 |

–4 |

–5 |

|

Other funds |

38 |

74 |

69 |

–5 |

–7 |

|

Totals |

$1,544 |

$1,969 |

$2,197 |

$229 |

12% |

|

Parks and Recreation |

|||||

|

General Fund |

$118 |

$117 |

$118 |

$0.2 |

0.2% |

|

Parks and Recreation Fund |

162 |

188 |

180 |

–9 |

–5 |

|

Off–Highway Vehicle Trust Fund |

123 |

115 |

92 |

–24 |

–21 |

|

Harbors and Watercraft Fund |

38 |

63 |

61 |

–1 |

–2 |

|

Bond funds |

58 |

70 |

32 |

–38 |

–55 |

|

Other funds |

53 |

166 |

126 |

–40 |

–24 |

|

Totals |

$552 |

$720 |

$608 |

–$112 |

–16% |

|

Fish and Wildlife |

|||||

|

General Fund |

$96 |

$86 |

$97 |

$11 |

13% |

|

Fish and Game Fund |

121 |

132 |

122 |

–11 |

–8 |

|

Bond funds |

24 |

107 |

73 |

–34 |

–32 |

|

Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund |

22 |

3 |

60 |

57 |

2,161 |

|

Oil Spill Prevention Fund |

31 |

37 |

35 |

–2 |

–5 |

|

Other funds |

147 |

201 |

199 |

–1 |

–1 |

|

Totals |

$440 |

$567 |

$586 |

$20 |

3% |

|

Energy Commission |

|||||

|

Electric Program Investment Charge |

$183 |

$290 |

$145 |

–$146 |

–50% |

|

ARFVTF |

149 |

153 |

110 |

–43 |

–28 |

|

Energy Resources Program Account |

68 |

86 |

89 |

2 |

2 |

|

Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund |

— |

— |

85 |

85 |

— |

|

Other funds |

120 |

105 |

112 |

7 |

6 |

|

Totals |

$521 |

$635 |

$540 |

–$95 |

–15% |

|

SRA = State Responsibility Area and ARFVTF = Alternative and Renewable Fuel and Vehicle Technology Fund. |

|||||

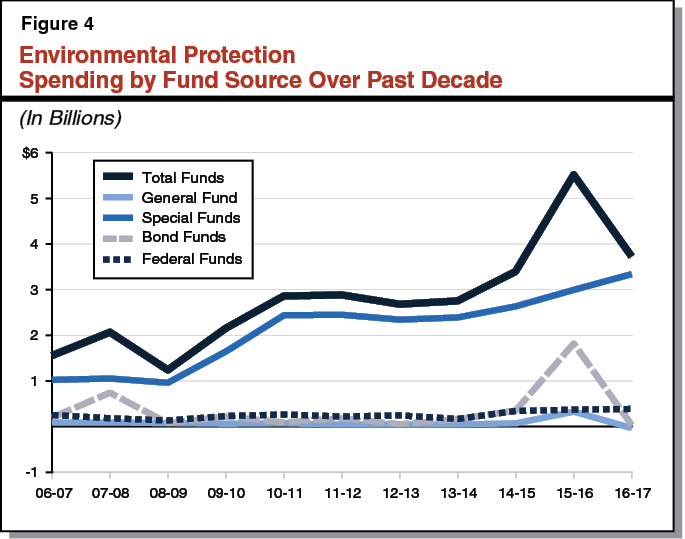

Environmental Protection Programs

Budget Continues Recent Spending Increases From Special Funds. Figure 4 shows spending on environmental protection departments since 2006–07. Historically, most environmental protection funding has come from special funds, usually derived from fees. The Governor’s budget provides 90 percent of environmental protection funding from special funds and reflects a net increase of $342 million from various special funds, particularly the GGRF.

Spending on Largest Environmental Protection Departments. Figure 5 shows spending and fund source information for the largest departments under the California Environmental Protection Agency. Notable changes include a total increase of $484 million from the GGRF for the Air Resources Board (ARB) and the Department of Resources Recycling and Recovery (CalRecycle) to implement and expand programs to reduce GHG emissions. In addition, the budget includes a reduction of $360 million in General Fund spending for CalRecycle. This decrease reflects one–time expenditures in the current year for debris removal following wildfires that occurred in 2015. These costs are then partially offset by federal reimbursements in the budget year. The budget also reflects a reduction of $1.8 billion in bond funds for the State Water Resources Control Board. This largely reflects the current–year appropriation of Proposition 1 funding.

Figure 5

Budget Summary for Largest Environmental Protection Departments—Selected Funding Sources

(Dollars in Millions)

|

Department |

2014–15 Actual |

2015–16 Estimated |

2016–17 Proposed |

Change From 2015–16 |

|

|

Amount |

Percent |

||||

|

Resources Recycling and Recovery |

|||||

|

General Fund |

— |

$243 |

–$117 |

–$360 |

–148% |

|

Beverage container recycling funds |

$1,325 |

1,313 |

1,308 |

–5 |

–0.3 |

|

Electronic Waste Recovery |

93 |

102 |

102 |

0.2 |

0.2 |

|

Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund |

19 |

2 |

100 |

98 |

6,004 |

|

Other funds |

112 |

141 |

134 |

–6 |

–5 |

|

Totals |

$1,549 |

$1,800 |

$1,528 |

–$272 |

–15% |

|

State Water Resources Control Board |

|||||

|

General Fund |

$36 |

$47 |

$48 |

$1 |

2% |

|

Underground Tank Cleanup |

196 |

300 |

294 |

–7 |

–2 |

|

Waste Discharge Fund |

117 |

125 |

127 |

2 |

2 |

|

Bond funds |

348 |

1,822 |

34 |

–1,788 |

–98 |

|

Other funds |

415 |

620 |

504 |

–116 |

–19 |

|

Totals |

$1,112 |

$2,914 |

$1,006 |

–$1,908 |

–65% |

|

Air Resources Board |

|||||

|

Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund |

$130 |

$187 |

$573 |

$386 |

206% |

|

Motor Vehicle Account |

131 |

137 |

134 |

–3 |

–2 |

|

Air Pollution Control Fund |

112 |

118 |

116 |

–3 |

–2 |

|

Other funds |

132 |

122 |

133 |

11 |

9 |

|

Totals |

$506 |

$565 |

$956 |

$391 |

69% |

|

Toxic Substances Control |

|||||

|

General Fund |

$27 |

$27 |

$29 |

$2 |

7% |

|

Hazardous Waste Control |

58 |

64 |

61 |

–2 |

–4 |

|

Toxic Substances Control |

46 |

66 |

57 |

–9 |

–13 |

|

Other funds |

80 |

74 |

70 |

–4 |

–5 |

|

Totals |

$210 |

$230 |

$218 |

–$13 |

–5% |

|

Pesticide Regulation |

|||||

|

Pesticide Regulation Fund |

$85 |

$88 |

$94 |

$6 |

7% |

|

Other funds |

3 |

3 |

3 |

–0.01 |

–0.3 |

|

Totals |

$88 |

$91 |

$97 |

$6 |

7% |

Cross–Cutting Issues

Cap–and–Trade Expenditures

LAO Bottom Line. In many cases, the administration’s budget proposals provide limited information that can be used to prioritize among the various options for spending billions of dollars of cap–and–trade auction revenues. We recommend the Legislature direct the administration to provide additional information that can be considered in this year’s budget deliberations. We also recommend establishing an expert committee to provide guidance that would help ensure the Legislature has better information in future years about how to target funds most efficiently.

Background

AB 32 and Cap–and–Trade. The Global Warming Solutions Act of 2006 (Chapter 488 [AB 32, Núñez/Pavley]), commonly referred to as AB 32, established the goal of reducing GHG emissions statewide to 1990 levels by 2020. The legislation directed ARB to adopt regulations to achieve the maximum technologically feasible and cost–effective GHG emission reductions by 2020. As shown in Figure 6, the plan adopted by ARB includes a wide variety of regulations intended to help the state meet its GHG goal, including cap–and–trade, the low carbon fuel standard (LCFS), energy efficiency programs, and the renewable portfolio standard.

Figure 6

Regulations Expected to Help State Meet 2020 Greenhouse Gas Emissions Goal

|

Regulations |

MMTCO2E Reduction |

|

Cap–and–trade |

23 |

|

Low carbon fuel standard |

15 |

|

Energy efficiency and conservation |

12 |

|

33 percent renewable portfolio standard |

12 |

|

Refrigerant tracking, reporting, and repair deposit program |

5 |

|

Advanced clean cars |

3 |

|

Reductions in vehicle miles traveled (SB 375) |

3 |

|

Landfill methane control |

2 |

|

Other regulations |

5 |

|

Total |

78 |

|

MMTCO2E = million metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent. |

|

One of the primary regulations adopted by the ARB intended to ensure the state meets these goals is the cap–and–trade regulation. The cap–and–trade regulation places a “cap” on aggregate GHG emissions from large GHG emitters, such as large industrial facilities, electricity generators and importers, and transportation fuel suppliers. Capped sources of emissions are responsible for roughly 85 percent of the state’s GHG emissions. The cap declines over time, ultimately arriving at the target emission level in 2020. To implement the cap–and–trade program, ARB issues carbon allowances equal to the cap, and each allowance is essentially a permit to emit one ton of carbon dioxide equivalent. Entities can also “trade” (buy and sell on the open market) the allowances in order to obtain enough to cover their total emissions.

Auctions Generate Billions of Dollars in State Revenue. One important aspect of implementing a cap–and–trade program is determining how to distribute allowances. In theory, allowances can be issued in one of three general ways: (1) they can be given away for free, (2) they can be auctioned by the state, or (3) some portion can be freely allocated while the other portion is auctioned. In 2015, ARB auctioned about half of 2015 allowances and gave about half away for free. The ARB has conducted 13 quarterly cap–and–trade auctions since November 2012—generating roughly $3.5 billion in state revenue. These revenues are deposited in the GGRF, which ARB is responsible for administering.

State Law Requires Auction Revenue Be Used to Reduce GHGs. Statutes enacted in 2012 direct the use of auction revenue. For example, Chapter 807 of 2012 (AB 1532, Perez) requires auction revenues be used to further the purposes of AB 32. Revenues must be used to facilitate GHG emission reductions in California. In addition to reducing GHGs, to the extent feasible, funds must be used to achieve other goals, such as:

- Maximize overall economic, environmental, and public health benefits to the state.

- Complement efforts to improve air quality.

- Lessen the effects of climate change on the state (also known as climate adaptation).

- Direct investment toward the most disadvantaged communities and households in the state.

In addition, Chapter 830 of 2012 (SB 535, de León) requires that at least 25 percent of auction revenue go to projects that benefit disadvantaged communities (as determined by the Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment) and at least 10 percent go to projects located within disadvantaged communities.

There is currently a court case challenging whether the state can continue collecting revenue from auctions. In a lawsuit against ARB, plaintiffs argue that the Legislature did not provide ARB the authority to auction allowances and collect state revenue. They further argue that even if the Legislature gave ARB the authority to collect auction revenue, such revenue constitutes an illegal tax. In November 2013, the superior court ruled that the charges from the auction have characteristics of a tax as well as a fee, but that, on balance, the charges constitute legal regulatory fees. This ruling has been appealed, and final decisions from the appellate courts on these issues may take years. If the courts’ final decision on these questions is to determine that ARB has the authority to collect auction revenue, it is likely that the courts would establish some limits on how revenues can be used. The courts would likely require the state to target spending to GHG reduction activities since that is the primary goal of AB 32. The extent to which the courts would allow the state to use the funds in a way that is intended to achieve other AB 32 goals (such as improving air quality and minimizing costs for households) or for activities with less certain effects on GHGs is unclear.

How Has Auction Revenue Been Spent So Far? As illustrated in Figure 7, auction revenue has been used to fund various programs and projects. For revenue collected in 2015–16 and beyond, statute continuously appropriates (1) 25 percent for the state’s high–speed rail project, (2) 20 percent for affordable housing and sustainable communities grants (with at least half of this amount for affordable housing), (3) 10 percent for intercity rail capital projects, and (4) 5 percent for low carbon transit operations. The remaining 40 percent is available for annual appropriation by the Legislature. Statute also requires that an outstanding loan of $400 million in auction revenues to the General Fund be repaid to the high–speed rail project when needed by the project.

Figure 7

Cap–and–Trade Revenue Expenditures

(In Millions)

|

Program |

2013–14 |

2014–15 |

2015–16a |

|

High–speed rail |

— |

$250 |

$600 |

|

Affordable housing and sustainable communities |

— |

130 |

480 |

|

Transit and intercity rail capital |

— |

25 |

240 |

|

Transit operations |

— |

25 |

120 |

|

Low carbon transportation |

$30 |

200 |

90 |

|

Low–income weatherization and solar |

— |

75 |

70 |

|

Agricultural energy and operational efficiency |

10 |

25 |

40 |

|

Urban water efficiency |

30 |

20 |

20 |

|

Sustainable forests and urban forestry |

— |

42 |

— |

|

Waste diversion |

— |

25 |

— |

|

Wetlands and watershed restoration |

— |

25 |

— |

|

Other administration |

2 |

10 |

31 |

|

Totals |

$72 |

$852 |

$1,691 |

|

aBased on LAO projection of $2.4 billion in revenue in 2015–16. The fund balance is projected to be $1.6 billion by the end of 2015–16. |

|||

Administration Required to Provide Two Major Reports to Inform Spending Decisions. State law directs the administration to submit two major reports to the Legislature intended to guide cap–and–trade spending decisions: (1) a three–year investment plan intended to provide general guidance for how to target funding and (2) an annual March report on project outcomes. As part of the investment plan, the administration must:

- Identify the state’s near–term and long–term GHG reduction goals and targets by sector.

- Analyze gaps in current state strategies to meeting the state’s GHG emission reduction goals.

- Identify priority investments that will facilitate the achievement of feasible and cost–effective GHG reductions.

The annual March report must include information about the status of projects funded and their outcomes, including a description of how agencies have met the requirements to provide benefits to disadvantaged communities.

Administration Recently Released an Updated Investment Plan. On January 25, 2016, the administration released an updated investment plan. The plan identifies three major priority areas of spending: (1) transportation and sustainable communities, (2) clean energy and energy efficiency, and (3) natural resources and waste diversion. Within each category, the plan identifies many different programs that could potentially help reduce GHG emissions and achieve other goals. It also identifies two potential cross–cutting approaches—local “integrated projects” in disadvantaged communities and “efficient financing mechanisms” for GHG reduction projects. Integrated projects could include several different components that potentially reduce GHGs. For example, an integrated project might include a combination of affordable housing near transit, a new transit line, zero emission busses, bicycle and walking paths, and tree planting. Efficient financing mechanisms for GHG emission reduction projects could include such things as revolving loan funds and loan guarantee programs.

Governor’s Proposal

The Governor’s 2016–17 budget includes a $3.1 billion cap–and–trade expenditure plan, as shown in Figure 8. The expenditure plan generally provides funding for programs that are identified as priority areas in the Investment Plan. An estimated $1.2 billion would be continuously appropriated consistent with current law. The remaining $1.9 billion in expenditures included in the budget are described below.

Figure 8

Governor’s 2016–17 Cap–and–Trade Expenditure Plan

(In Millions)

|

Continuous Appropriationsa |

$1,200 |

|

High–speed rail |

500 |

|

Affordable housing and sustainable communities |

400 |

|

State transit assistance |

200 |

|

Transit and intercity rail capital |

100 |

|

Transportation |

1,025 |

|

Low carbon vehicles |

460 |

|

Transit and intercity rail capital |

400 |

|

Low carbon road program |

100 |

|

Biofuel production subsidies |

40 |

|

Biofuel facilities capital support |

25 |

|

Carbon Sequestration |

280 |

|

Healthy forests |

150 |

|

Wetland and watershed restoration |

60 |

|

Urban forestry |

30 |

|

Green infrastructure |

20 |

|

Carbon sequestration in soils |

20 |

|

Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy |

200 |

|

Low–income energy efficiency and solar |

75 |

|

UC and CSU energy efficiency |

60 |

|

Energy efficiency for state buildings |

30 |

|

I–Bank energy financing program |

20 |

|

Conservation Corps energy efficiency |

15 |

|

Short–Lived Climate Pollutants |

195 |

|

Waste diversion |

100 |

|

Wood stove replacement |

40 |

|

Dairy digesters |

35 |

|

Refrigeration unit replacements |

20 |

|

Local Climate Program |

100 |

|

Water Efficiency |

90 |

|

Water efficiency technology |

30 |

|

Agricultural water efficiency |

20 |

|

Rebates for efficient clothes washers |

15 |

|

Low–income household water efficiency upgrades |

15 |

|

Commercial and institutional water efficiency |

10 |

|

Total |

$3,090 |

|

aContinuous appropriations based on Governor’s $2 billion revenue estimate. GHG = greenhouse gas; CSU = California State University; and UC = University of California. |

|

Transportation ($1 Billion). The Governor’s plan includes over $1 billion for programs intended to reduce transportation–related GHG emissions. These programs are:

- Low Carbon Vehicles. The ARB would receive $460 million largely to continue existing programs that provide incentives for zero–emission vehicles (such as electric cars) and clean trucks and buses. The ARB estimates that up to $90 million would be used to provide rebates to households, businesses, and governments that will be put on a waiting list in 2015–16 due to insufficient funds in the current year. The remaining amount would be used to provide rebates and grants through 2016–17.

- Transit and Intercity Rail Capital. The California Transportation Agency would be provided with $400 million in funding to expand the transit and intercity rail capital program. (This amount is in addition to the amount that would be continuously appropriated under current law.) This proposal is part of the Governor’s transportation funding package.

- Low Carbon Road Program. The California Department of Transportation would be allocated $100 million to provide funding for a new program to support city and county transportation projects that reduce vehicle emissions. Eligible projects could include installing roundabouts, optimizing traffic signals, and projects that promote pedestrian and bicycle safety.

- Biofuel Production Subsidies. The ARB would receive $40 million for a new program that would provide a subsidy to in–state biofuel facilities for each gallon of low–carbon fuels they produce. Biofuels are fuels produced from living matter, such as plants or animal waste.

- Biofuel Facilities Capital Support. The CEC would receive $25 million to expand a program that supports construction or expansion of in–state biofuel facilities. The funds would be added to the roughly $20 million from the CEC’s existing Alternative and Renewable Fuel and Vehicle Technology Program that supports similar activities.

Carbon Sequestration ($280 Million). The Governor’s plan includes $280 million for projects intended to reduce GHGs in the atmosphere largely by sequestering carbon dioxide.

- Healthy Forests. CalFire would be allocated $150 million for a variety of activities intended to improve forest health in order to improve forest carbon sequestration and reduce wildland forest fire fuels to avoid emissions associated with wildfires. This program expands and combines existing programs that focus on certain types of forest health activities, such as reforestation and forest pest control activities. Under the new program, CalFire would fund large landscape–level forest health projects that might include several different types of projects.

- Wetland and Watershed Restoration. The DFW would receive $60 million to continue to restore Delta and coastal wetlands and mountain meadows, as well as expand the program to include desert ecosystems.

- Urban Forestry. CalFire would be allocated $30 million to continue to assist local governments, special districts, and nonprofits with urban forestry by providing grants for and technical assistance with tree planting, biomass diversion projects, and reclamation of blighted urban land for urban forestry purposes.

- Green Infrastructure. The California Natural Resources Agency (CNRA) would be provided with $20 million to reduce GHGs through investments in green infrastructure, such as green roof projects to reduce energy usage and projects that mitigate storm water runoff to reduce water needs. This program is modeled after a program that funded similar activities with bond funds.

- Carbon Sequestration in Soils. The California Department of Food and Agriculture (CDFA) would be allocated $20 million to implement a new Healthy Soils Program designed to reduce GHG emissions and increase carbon sequestration through alternative soil management practices, such as mulching and adding organic matter to the soil.

Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy ($200 Million). The Governor’s plan includes $200 million for programs that promote energy efficiency in buildings and renewable energy. These programs are:

- Low–Income Energy Efficiency and Solar. The Department of Community Services and Development (CSD) would be allocated $75 million to continue a program that supports weatherization, solar installation, and other energy efficiency projects for low–income households. Project examples include insulating homes, repairing and replacing windows, and upgrading heating and cooling systems.

- UC and CSU Energy Efficiency. The budget includes a total of $60 million for the state’s university systems—including $35 million for California State University (CSU) and $25 million for the University of California (UC)—to perform energy efficiency upgrades in existing buildings. Projects could include such things as installing new insulation and lighting.

- Energy Efficiency for State Buildings. The Department of General Services would be provided $30 million to expand a loan program for energy efficiency retrofits in state buildings, such as replacing heating and cooling systems and lighting. These loans are repaid using the energy savings achieved by the projects.

- I–Bank Energy Financing Program. The Governor’s Office of Business and Economic Development would receive $20 million to expand the I–Bank’s California Lending for Energy and Environmental Needs loan financing program for public energy efficiency and infrastructure improvement projects that reduce GHGs and conserve energy.

- Conservation Corps Energy Efficiency. The proposal provides the California Conservation Corps (CCC) with $15 million to expand the Energy Corps Program. This program focuses on performing energy efficiency and water conservation surveys in public buildings and performing retrofit projects that save energy.

Short–Lived Climate Pollutants ($195 Million). The Governor’s budget proposes $195 million for programs intended to reduce short–lived climate pollutants (SLCPs). These pollutants are a type of GHG that have a relatively short lifetime in the atmosphere compared to carbon dioxide (the most common GHG). The Governor’s proposals are:

- Waste Diversion. CalRecycle would receive $100 million to continue grants, demonstration projects, and loans to divert waste from landfills to recycling facilities, anaerobic digesters, or composting facilities with the goal of reducing methane emissions from landfills (methane is an SLCP).

- Wood Stove Replacement. The plan provides $40 million to ARB for a new residential wood burning device replacement incentive program to reduce GHG emissions from wood smoke. Wood smoke is source of black carbon, which is an SLCP. The incentive program would be based on past programs implemented at the local level.

- Dairy Digesters. The CDFA would receive $35 million to continue the Dairy Digester Research and Development Program. Dairy digesters are designed to reduce GHGs by capturing methane emitted from dairy operations and converting it into energy in the form of electricity and renewable fuel.

- Refrigeration Unit Replacements. The ARB would be allocated $20 million to provide incentives for commercial grocery stores and markets in disadvantaged communities to replace their refrigeration systems with units that leak fewer GHGs.

Local Climate Program ($100 Million). The Governor’s plan includes $100 million to fund integrated local projects intended to reduce GHG emissions in disadvantaged communities.

Water Efficiency ($90 Million). The Governor’s plan includes $90 million for programs intended to improve water efficiency and save energy. A significant amount of energy is used to pump, transport, heat, and treat water. Therefore, reducing water consumption or improving the energy efficiency of existing water–related activities can reduce energy consumption and GHGs. The water efficiency programs included in the cap–and–trade expenditure plan are:

- Water Efficiency Technology. The CEC would receive $30 million to fund a new program for innovative water efficiency technologies. The program would provide incentives for three different areas of emerging technologies that, according to the administration, are not yet widely deployed: (1) agricultural water efficiency; (2) industrial, commercial, and residential water efficiency; and (3) energy efficiency in desalination facilities.

- Agricultural Water Efficiency. The CDFA would be allocated $20 million to continue funding for the Statewide Water and Efficiency Enhancement Program. This program was developed to reduce GHGs and save water by providing incentives for (1) efficient irrigation methods that reduce the need to pump water, (2) energy efficient water pumps, and (3) other measures.

- Rebates for Efficient Clothes Washers. The CEC would receive $15 million for a new program that would provide $100 rebates to households that purchase water and energy efficient clothes washers. This program would be similar to an appliance rebate program that operated several years ago as part of the federal stimulus package.

- Low–Income Household Water Efficiency Upgrades. The CEC, in partnership with CSD, would be provided with $15 million to install water and energy efficient appliances, shower heads, and faucets in low–income households. The CEC would design the new program and provide funding to CSD, which would perform the installations at the same time as its other low–income energy efficiency upgrades described above.

- Commercial and Institutional Water Efficiency. The DWR would receive $10 million to provide grants for water management projects and programs. According to DWR, the program would focus on projects within the commercial or institutional buildings—such as schools, hospitals, or government buildings—that result in more efficient water and energy use. This would be a modified version of an existing program that largely funds residential water efficiency projects.

Governor’s Revenue Estimates Slightly Lower, but Reasonable

As shown in Figure 9, our office’s estimates of cap–and–trade revenues are similar to those of the administration. The primary difference is that our 2016–17 estimate ($2.3 billion) is a few hundred million dollars higher than the Governor’s ($2 billion). Our estimates assume that all of the allowances offered for sale at auctions will sell for the minimum price established by the ARB. Under the Governor’s estimated revenues and proposed expenditures, there would be a $500 million fund balance remaining at the end of 2016–17. Under our revenue estimate, the fund balance would be $120 million higher and 60 percent of the higher revenues would be dedicated to the continuously appropriated programs ($180 million).

Figure 9

Comparison of Administration and LAO Cap–and–Trade Revenue Estimates

(In Millions)

|

LAO |

Administration |

Difference |

|

|

2015–16 |

$2,400 |

$2,400 |

— |

|

2016–17 |

2,300 |

2,000 |

$300 |

Interactions With Regulations Has Implications for Evaluating Spending Options

Understanding and estimating the net benefits of different GHG reduction programs is difficult for many reasons. One factor contributing to the difficulty is that, in certain cases, spending funds on GHG reduction activities interacts with other climate regulations. Such interactions can be complex, but they have important implications for how the Legislature might want to target spending and how it evaluates the net benefits of different projects. Below, we describe the interaction that spending has with one key regulation—the cap–and–trade regulation—and the implications it has for evaluating different spending options.

Current Requirement to Spend on GHGs Creates Policy Challenges. In a report issued in January 2016, we described and assessed the relationship between the cap–and–trade regulation and the auction revenue that is generated as a result of the program. (For more details, see our report Cap–and–Trade Revenues: Strategies for Promoting Legislative Priorities.) In this report, we describe how, from a policy standpoint, the cap–and–trade regulation is key to ensuring that the state meets its GHG goals cost–effectively. In contrast, the revenues generated from the cap–and–trade auctions can be considered more of a byproduct of the program rather than as a primary goal of the program.

At first glance, spending on activities that reduce GHGs would appear to encourage additional emission reductions. However, spending auction revenue on GHG emission reductions in the capped sector can interact with the cap–and–trade regulation in somewhat complicated and perhaps unexpected ways. As a result, the current legal requirement creates several policy challenges.

- Spending Likely Not Needed to Meet GHG Goals. As long as the cap is limiting emissions, subsidizing an emission reduction from one capped source—including transportation fuels and electricity generation—will simply free–up allowances for other emitters to use. The end result is a change in the sources of emissions, but no change in the overall level of emissions.

- Spending Likely Increases Overall Costs of Emission Reductions. The cap–and–trade regulation generally creates a financial incentive for households and businesses to find the least costly mix of emission reductions. Therefore, using state funds to encourage a different mix of GHG emission reductions would likely be more costly.

- Limits Flexibility to Achieve Other Goals. The requirement to spend on GHG reductions limits the Legislature’s flexibility to use the revenue in a way that could achieve its non–GHG goals, such as (1) reducing costs for energy users; (2) promoting other climate–related goals, such as climate adaptation; and (3) promoting other legislative priorities unrelated to climate change, such as improving the state’s transportation infrastructure.

To address these challenges, one option for the Legislature would be to remove the legal requirement to spend on GHG reductions by reauthorizing cap–and–trade with a two–thirds vote. This would give the Legislature greater flexibility to return the revenue directly to households and businesses and/or use the funds to address its highest priorities. Moreover, as long as the cap is in place, the state will likely achieve its GHG goals from major sources of emissions. Alternatively, if the requirement to spend on GHG reductions remains in place, the Legislature might want to consider a mix of the following strategies as a way to maximize different legislative priorities: (1) spend on emission reductions from uncapped sources to achieve net GHG reductions, (2) target spending to reduce overall costs of emission reductions, (3) prioritize projects that also achieve non–GHG goals, and (4) offset other types of state spending to enable greater budget flexibility.

Analyses That Can Help Legislature Target Spending Under Requirement to Reduce GHGs. Although the requirement to spend on activities that reduce GHGs creates some challenges, the funds can still be used to provide significant benefits. However, allocating the funds in a way that achieves the greatest level of benefits should be informed by reliable information about the degree to which different projects help achieve desired benefits, as well as how those benefits are distributed to different households and businesses. Below, we outline two general types of analyses that, in our view, could help the Legislature evaluate various cap–and–trade spending proposals.

- General Framework for Spending. It is important to first establish a general framework for evaluating spending options. In our view, such a framework should be based on an analysis of how the spending interacts with the cap–and–trade regulation, as we described above, and other regulations. This analysis could then inform the development of strategies for targeting spending in ways that achieve different priorities. For example, if the priority is to encourage net GHG reductions, a framework might identify the types of programs that most likely help achieve this goal, such as targeting uncapped sources of emissions. The analysis could also identify efforts that would target emissions from capped sources in ways that minimize the overall costs of reductions. To the extent that a priority is to address other goals—such as reducing costs for businesses or households in disadvantaged communities or improving co–benefits like air quality—the framework could identify ways for funds to be targeted that help achieve these goals most effectively. Currently, the three–year investment plan is intended to be the document that provides such a framework. However, as we discuss below, we find that the investment plan currently does not provide a robust analytical framework.

- Reliable Estimation of Net Benefits of Specific Programs or Projects. A general framework for spending can provide guidance for evaluating different spending options and identifying categories of spending that achieve different state priorities most effectively. However, in the end, the Legislature will have to allocate funds to specific programs based on its assessment of which programs provide the greatest overall benefits. In our view, accurate and reliable estimates of the net benefits—including of both GHG and non–GHG benefits—associated with different programs could inform such decisions.

Proposal Lacks Key Information to Help Legislature Prioritize Spending

Many of the proposals offered by the administration might have significant merit. However, in our view, the Governor’s plan lacks a robust analytical framework and reliable estimates of benefits. This missing information makes it difficult to evaluate which programs provide the greatest overall benefits. The analysis that would be needed to provide reliable information is difficult and likely requires expert knowledge of different regulatory and market conditions, as well as a general understanding of the programs being considered. Furthermore, there is an inherent level of uncertainty around the benefits of new programs and new types of technologies. Despite these challenges, given the significant amount of funding that would be allocated under this year’s expenditure plan—as well as the billions of dollars that will be available in future years—we think the Legislature would benefit from more reliable information in these areas.

Investment Plan Lacks Robust Analysis Needed to Develop Framework for Spending. In our view, the investment plan does not provide a robust analytical framework for evaluating spending options. This is evident in the “gaps and needs assessment” included for each category of spending. The gap assessment describes different types of programs that could reduce GHGs within the priority areas of spending identified by the administration. However, the administration does not provide a clear analytical justification for why spending of auction revenues on each of these programs is likely to achieve state priorities most effectively compared to alternative options. In particular, the investment plan does not include the following analyses:

- Assessment of How Spending Options Interact With Cap–and–Trade Regulation. The plan does not discuss the interactions with the cap–and–trade program and its implications for assessing different spending options. As a result, it fails to identify strategies for targeting spending in ways that achieve additional net GHG emission reductions or promote the most cost–effective mix of emission reductions from capped sources.

- Assessment of How Spending Options Interact With Other Regulations. The investment plan does not explicitly address how new programs might interact with existing regulations or programs. For example, biofuel production is identified as one potential priority area for investment. Financial support for biofuel production likely interacts with the LCFS regulation. The LCFS is another market–based mechanism administered by ARB that requires a 10 percent reduction in the carbon intensity of fuels by 2020. Increased biofuel production is expected to be one of the primary ways the regulated communities will comply with the regulation. Providing additional state subsidies for biofuel production might not change the overall carbon intensity of the fuel. Instead, it might simply reduce the costs for businesses that would produce biofuels under the regulation. While there may be a strong rationale for supporting biofuel production, the investment plan does not discuss this type of interaction when evaluating the role of spending in the context of other regulations.

Certain Budget Proposals Lack Details About Projects. Some of the new or significantly modified proposals lack details about what types of projects will be funded and which types of projects will be selected. For example, the overall mix of forestry projects that will be selected as part of CalFire’s new landscape–scale forest health proposal is unclear. In addition, the Strategic Growth Council program for local climate projects in disadvantaged communities provides very little detail about what types of projects are funded. In this case, the lack of detail is largely due to the design of the program—which is to rely on local communities to make proposals that identify the types of projects that are likely to provide the greatest overall benefits to that specific community. Other programs for which the types of projects will be funded is somewhat unclear include DWR’s commercial and institutional water efficiency program and the Low Carbon Road Program. These programs could have significant merit, but the lack of information about what types of projects will be implemented makes it particularly difficult to assess the potential benefits and outcomes.

Expected Benefits of Proposals Are Often Unclear or Uncertain. Even when the characteristics of the projects are relatively clear, the expected outcomes often are either unclear or subject to considerable uncertainty. First, the administration has not provided estimated benefits—including GHG reductions or co–benefits—for several of the programs, including the wetland restoration or urban forestry proposals. Other proposals include GHG estimates, but do not provide information about the expected co–benefits. For example, the CCC Energy Corps proposal includes estimates of GHG reductions, but not financial savings from improved energy efficiency that would accrue to building owners or occupants.

Second, even in instances when the administration provides estimates of benefits, we frequently identified limitations associated with the methods used to produce such estimates. For example, a couple of the methodological concerns that we identified are:

- No Accounting for Interactions With Existing Regulations or Programs. As described above, some of these programs likely interact with other regulations, such as the cap–and–trade program and the LCFS. For example, ARB’s biofuel production subsidies and CEC’s funding for capital investments for biofuel facilities might not change the overall amount of biofuel consumed in California. Rather, these programs might simply reduce the costs of biofuel production that would have occurred under the incentives provided by the LCFS. While the Legislature might consider reducing companies’ compliance costs a valuable use of cap–and–trade revenue, the administration fails to mention or account for this likely interaction when estimating and describing GHG reductions and net benefits. Thus, the GHG reductions associated with these proposals are likely overstated.

- No Accounting for “Free–Riders.” It is likely that some portion of the grants or rebates funded under the Governor’s plan would go toward activities that would have occurred anyway. In economic terms, households or businesses that access government rebates or subsidies for activities they would have undertaken anyways are sometimes referred to as free–riders. The administration’s estimates of benefits do not account for free–riders and, consequently, likely overestimate GHG reductions and co–benefits. For example, the CEC estimates of water savings and GHG reductions from the clothes washer rebate program assume that every household that receives a rebate would have purchased a less efficient model without the rebate. However, a recent study evaluating a similar appliance rebate program several years ago found that over 90 percent of the rebates went to households that would have purchased the more efficient clothes washer anyway. By ignoring free–riders, the administration likely overstates GHG reductions and water saving benefits. Furthermore, ignoring potential free–riders could lead to missed opportunities to target the funds in a way that are more likely to encourage changes in behavior.

Accounting for interactions with other regulations and free–ridership can be difficult. However, these factors can have significant implications for the overall type, level, and distribution of benefits of a particular program.

No Comprehensive Approach to Maximizing Benefits for Disadvantaged Communities. State law requires a minimum of 25 percent of funds go to projects that benefit disadvantaged communities and a minimum of 10 percent go to projects located in disadvantaged communities. Some proposals indicate the portion of program funds that will be targeted to disadvantaged communities. For example, the CCC indicates that it plans to use at least 60 percent of the funding to improve energy efficiency in public buildings located in disadvantaged communities. However, the administration has not provided a comprehensive plan for how it will achieve the overall disadvantaged communities goal. Furthermore, the administration has not provided an estimate of the disadvantaged community benefits for each proposal, the total amount of funding that will be used for projects that benefit disadvantaged communities, the types of benefits that will be provided, and how those benefits will be distributed across different households and regions. Without this information, it is difficult to evaluate the degree to which the Governor’s plan is consistent with legislative direction.

LAO Recommendations

Based on our assessment, we recommend the Legislature (1) direct the administration to provide more robust estimates of benefits, (2) allocate funds based on policy priorities and level of confidence in outcomes, and (3) establish an expert advisory committee to help target future spending.

Direct Administration to Provide More Robust Estimates of Benefits. In the short run, we recommend the Legislature direct the administration to report the following information for consideration in budget hearings: (1) detailed estimates of GHG and co–benefits associated with each proposal, including the methodologies used to produce such estimates, and (2) what portion of these benefits will accrue to households located in disadvantaged communities. This information could help the Legislature evaluate the degree to which each program promotes legislative priorities. As always, our office would be available to assist in evaluating the information provided by the administration.

Allocate Funds Based on Policy Priorities and Level of Confidence in Outcomes. Ultimately, the Legislature’s allocation of funds in the 2016–17 budget will depend on its assessment of the expected benefits associated with different programs, as well as the relative weight it gives to GHG emission reductions versus other co–benefits. There is some inherent level of uncertainty about the outcomes that will be achieved by each of these programs. Therefore, for programs where the types of projects would be funded are unclear—such as for new programs—and for programs where expected outcomes are most uncertain, the Legislature might want to consider allocating a relatively small amount of funds in the first year and waiting for program outcomes to be available prior to allocating additional funds in future years.

Establish a Committee to Develop a More Robust Investment Plan. We recommend the Legislature establish an independent advisory committee consisting primarily of economic experts and scientists to assist the administration in developing a more robust strategy for targeting funds in future years in ways that encourage the most cost–effective GHG reductions and promote other co–benefits. In particular, greater economic expertise could help provide guidance about how to target funds most cost–effectively under existing market and regulatory conditions. The committee could also provide recommendations regarding the methods that could be used to estimate benefits prior to awarding funds and evaluate the outcomes of different types of projects after they have been implemented.

State’s Drought Response

Recent Report Summarized State’s Response, Recommended Next Steps. Our recent publication, The 2016–17 Budget: The State’s Drought Response, contains a detailed assessment of the Governor’s 2016–17 drought package. The report (1) describes the current drought and its impacts across the state, (2) summarizes the state’s drought response appropriations and activities thus far, (3) assesses the Governor’s drought–related budget proposals for 2016–17, and (4) recommends steps the Legislature can take to address drought both in the coming year and the future. Below, we summarize our major findings.

Background

State Experiencing Exceptionally Dry Period. California has been experiencing a serious drought for the past four years. In fact, by some measures the current drought actually began in 2007, with one wet year—2011—in the middle. While there are optimistic signs that El Niño weather patterns will bring California a wet winter in 2016, how much precipitation will fall as snow in the state’s northern mountain ranges—a major source of the state’s water throughout the year—remains uncertain. Moreover, the cumulative deficit of water reserves resulting from multiple years of drought is sufficiently severe that some degree of drought conditions likely will continue at least through 2016. Scientific research also suggests that climate change will lead to more frequent and intense droughts in the future.

State Has Employed Multifaceted Response to Current Drought. The state has deployed numerous resources—fiscal, logistical, and personnel—in responding to the impacts of the current drought. This includes appropriating $3 billion to 13 different state departments between 2013–14 and 2015–16. In addition to increased funding, the state’s drought response has included certain policy changes. Because current drought conditions require immediate response but are not expected to continue forever, most changes have been authorized on a temporary basis, primarily by gubernatorial executive orders or emergency departmental regulations. For example, one of the most publicized temporary drought–related policies has been the Governor’s order (enforced through regulations) to reduce statewide urban water use by 25 percent.

Governor’s Proposal

Governor Proposes $323 Million for Drought Response Activities in 2016–17. The Governor’s budget proposal provides $212 million from the General Fund, $90 million from GGRF—auction revenues from the state’s cap–and–trade program—and $21 million from other special funds for drought response efforts in 2016–17. This funding would primarily support the continuation of initiatives funded in recent years that address emergency drought response needs. For example, the proposal includes funding for increased wildland firefighting, to provide various forms of human assistance in drought–affected communities (such as drinking water, food, financial assistance, and housing and employment services), and to monitor and assist at–risk fish and wildlife. The GGRF monies would fund four conservation programs intended to improve water and energy efficiency—two new, one existing, and one modified.

LAO Recommendations

Adopt Most of Governor’s Drought–Related 2016–17 Budget Proposals. We believe the Governor’s approach to focus primarily on the most urgent human and environmental drought–related needs makes sense. The severity of enduring drought conditions supports the continued need for these response activities. As such, we recommend the Legislature adopt the components of the Governor’s drought package that meet essential human and environmental needs and that are likely to result in immediate water conservation. This would include all of the proposals supported by General Fund ($212 million) and non–GGRF special funds ($21 million). We believe additional information is needed, however, before adopting the Governor’s four GGRF–funded conservation proposals. Whether these proposals represent the best approach to achieving water and energy savings and reducing GHGs is unclear. We therefore recommend the Legislature delay deciding on whether to fund these programs until the administration has provided additional information to justify the request.

Learn Lessons to Apply to Future Droughts. Given the certainty that droughts will reoccur, and the possibility that subsequent droughts might be similarly intense, we recommend the Legislature continue to plan now for the future. Such planning can be facilitated by (1) learning from the state’s response to the current drought, (2) identifying and sustaining short–term drought–response activities and policy changes that should be continued even after the current drought dissipates, and (3) identifying and enacting new policy changes that can help improve the state’s response to droughts in the future. We recommend the Legislature spend the coming months and years vetting various drought–related budget and policy proposals for their potential benefits and trade–offs, and enacting changes around which there is widespread and/or scientific consensus. This could include both changes that remove existing barriers to effective drought response, as well as proactive changes that improve water management across the state. The Legislature can gather such information through a number of methods, including oversight hearings and public forums, but we also recommend the administration submit two formal reports: one that provides data measuring the degree to which intended drought response objectives were met, and one that provides a comprehensive summary of lessons learned from the state’s response to this drought.

Proposition 1—2014 Water Bond

LAO Bottom Line. The Governor’s two major new 2016–17 Proposition 1 spending proposals—implementing statewide water–related commitments and restoring the Los Angeles River—represent a reasonable starting place, but the specific spending levels he has selected for each activity are not without trade–offs. We recommend the Legislature adopt a Proposition 1 spending package that represents its priorities.

Background

Proposition 1 Provides $7.5 Billion in General Obligation Bonds. In November 2014, voters approved Proposition 1, a $7.5 billion water bond measure aimed primarily at restoring habitat and increasing the supply of clean, safe, and reliable water. Most of the projects funded by Proposition 1 will be selected on a competitive basis, based on guidelines developed by state departments. While the measure prohibits the Legislature from allocating funding to specific projects, a few spending categories are subject to more legislative discretion, as discussed below.

Bond Included Certain Accountability Provisions. The bond measure also included some accountability provisions, including a requirement that CNRA annually publish a list of all program and project expenditures on its website. This website is also to include fields to display project outcomes based on pre–determined performance metrics, such as acreage of land restored or volume of water recycled. This is similar to how the agency reported on a previous resources bond (Proposition 84).

State in Midst of Implementing Proposition 1. As shown in Figure 10 , the bond provides funding for eight categories of activities. These funds will be distributed across 16 state departments (including ten state conservancies). As shown in the figure, the Legislature already has appropriated a combined $2.1 billion of available bond funding. Specifically, $270 million was appropriated via emergency drought legislation in March 2015 (Chapter 1 of 2015 [AB 91, Committee on Budget]) and $1.8 billion via the 2015–16 Budget Act. The $2.7 billion for water storage projects is not subject to legislative appropriation but rather is continuously appropriated to the California Water Commission (CWC). As such, $2.8 billion in authorized Proposition 1 funding remains for the Legislature to appropriate.

Figure 10

Summary of Proposition 1 Bond Funds

(In Millions)

|

Purpose |

Implementing Departments |

Bond Allocation |

Prior Appropriationsa |

2016–17 Proposed |

|

Water Storage |

$2,700 |

$5 |

$4 |

|

|

Water storage projects |

CWCb |

2,700 |

5 |

4 |

|

Watershed Protection and Restoration |

$1,496 |

$173 |

$605 |

|

|

State obligations and agreements |

CNRA |

475 |

— |

465 |

|

Watershed restoration benefiting state and Delta |

DFW |

373 |

37 |

37 |

|

Conservancy restoration projects |

Conservancies |

328 |

98 |

44 |

|

Enhanced stream flows |

WCB |

200 |

39 |

39 |

|

Los Angeles River restoration |

Conservancies |

100 |

— |

11 |

|

Urban watersheds |

CNRA |

20 |

<1 |

9 |

|

Groundwater Sustainability |

$900 |

$844 |

$1 |

|

|

Groundwater cleanup projects |

SWRCB |

800 |

784 |

— |

|

Groundwater sustainability plans and projects |

DWR |

100 |

60 |

1 |

|

Regional Water Management |

$810 |

$232 |

$57 |

|

|

Integrated Regional Water Management |

DWR |

510 |

33 |

55 |

|

Stormwater management |

SWRCB |

200 |

102 |

2 |

|

Water use efficiency |

DWR |

100 |

98 |

— |

|

Water Recycling and Desalination |

$725 |

$342 |

$1 |

|

|

Water recycling |

SWRCB |

725 |

292 |

— |

|

Desalination |

DWR |

50 |

1 |

|

|

Drinking Water Quality |

$520 |

$469 |

$5 |

|

|

Drinking water for disadvantaged communities |

SWRCB |

260 |

244 |

2 |

|

Wastewater treatment in small communities |

SWRCB |

260 |

225 |

2 |

|

Flood Protection |

$395 |

— |

— |

|

|

Delta flood protection |

DWR and CVFPB |

295 |

— |

— |

|

Statewide flood protection |

DWR and CVFPB |

100 |

— |

— |

|

Administration and Oversight |

— |

$1 |

$1 |

|

|

Administrationc |

DWR and CNRA |

— |

1 |

1 |

|

Totals |

$7,546 |

$2,066 |

$673 |

|

|

aIncludes $267 million from Chapter 1 of 2015 (AB 91, Committee on Budget) and $1.8 billion from the 2015–16 Budget Act. bWith staff support from DWR. cBond does not provide a specific allocation for bond administration and oversight, but allows a portion of other allocations to be used for this purpose. CWC = California Water Commission; CNRA = California Natural Resources Agency; DFW = Department of Fish and Wildlife; WCB = Wildlife Conservation Board; SWRCB = State Water Resources Control Board; DWR = Department of Water Resources; and CVFPB = Central Valley Flood Protection Board. |

||||

Of the $2.8 billion from Proposition 1 remaining for the Legislature to appropriate, $1.8 billion represents funding to continue activities initiated in 2015–16. (Departments do not plan to submit formal funding requests in future budget change proposals for this $1.8 billion unless they wish to deviate from the multiyear plan described below.) The remaining $1 billion represents funding for new activities that are not yet underway and for which the Legislature has not yet approved any appropriations. These three activities are: (1) statewide obligations and agreements ($475 million), (2) Los Angeles River restoration ($100 million), and (3) flood protection ($395 million).

Administration Has Developed Multiyear Appropriation Schedule. Figure 11 displays the administration’s multiyear funding plan for spending Proposition 1 bond funds. As shown, funding for many categories was “front–loaded,” with large appropriations in the current year and smaller amounts expected to be apportioned in subsequent years. Two primary exceptions are water storage and flood protection, for which the administration expects most funding will be allocated after 2019–20. This lag is because the CWC still is in the process of developing specific eligibility criteria for potential storage projects and because the state still has significant funding available for flood protection from prior bond measures.

Figure 11

Administration’s Multiyear Proposition 1 Funding Plan

|

Category |

Bond Allocation |

2014–15 and 2015–16 |

2016–17 |

2017–18 |

2018–19 |

2019–20and After |

|

Water storage |

$2,700 |

$5 |

$4 |

$418 |

$411 |

$1,808 |

|

Watershed protection and restoration |

1,495 |

173 |

605 |

173 |

136 |

379 |

|

Groundwater sustainability |

900 |

844 |

1 |

35 |

1 |

1 |

|

Regional water management |

810 |

232 |

57 |

302 |

7 |

197 |

|

Water recycling and desalination |

725 |

342 |

1 |

133 |

233 |

2 |

|

Drinking water quality |

520 |

469 |

5 |

24 |

4 |

8 |

|

Flood protection |

395 |

— |

— |

— |

— |

387 |

|

Totalsa |

$7,545 |

$2,066 |

$671 |

$1,085 |

$791 |

$2,782 |

|

aAppropriation amounts exclude $151 million to pay for statewide bond costs, including $1.4 million in 2016–17. |

||||||

Bond Sets Aside $475 Million for Certain Statewide Commitments. The largest portion of Proposition 1 funding remaining for the Legislature to appropriate consists of $475 million for statewide obligations and agreements (from the section of the bond that dedicates funds for watershed protection and restoration). These funds are intended to help meet water–related commitments into which the state has entered. The bond explicitly identifies four such agreements for which the funding can be used—the Central Valley Project Improvement Act (CVPIA), the Salton Sea Restoration Act, the San Joaquin River Restoration Settlement Act, and the Tahoe Regional Planning Compact. In addition, Proposition 1 states that funding for statewide commitments can be used for a multiparty agreement that meets a number of specific characteristics, all of which the Klamath Hydroelectric Settlement Agreement meets. (Drafters of the bond indicate that the Klamath agreement was considered as a prime candidate for this funding. As such, we describe that agreement below.) The bond did not specify how much—if any—of this funding should be allocated to each commitment. Moreover, as noted in the descriptions below, the total cost to fulfill all of these commitments greatly exceeds $475 million. Proposition 1 left it to the Legislature to determine how best to allocate this funding amongst the five potential commitments.

- CVPIA. Enacted by Congress in 1992, the CVPIA included numerous changes for federal water operations in California. Among these was a commitment to provide a guaranteed annual water supply to 19 state, federal, and privately owned wildlife refuges in the Central Valley that serve as critical wetland habitat to numerous wildlife species. The federal government committed to providing the baseline amount of water needed by the wildlife (“Level 2”), and to paying 75 percent of the costs of providing the optimal amount of water needed (“Level 4”). The legislation included a commitment for California to contribute the remaining 25 percent towards the costs of providing Level 4 water supplies (which can be met through in–kind contributions such as staff support). Despite the more than two decades since enactment of the CVPIA, not all of the refuges have acquired permanent Level 4 water supplies. According to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, government agencies struggle to acquire the additional water because “usually there are too few willing sellers, too little funding to buy their water, or both.” Additionally, some locations still lack the infrastructure needed to convey all the water mandated by CVPIA to the refuges. The administration states that because of accounting difficulties with the federal agencies involved, estimates are not available for the total cost of ensuring Level 4 water supplies, the state’s share of that cost, or the amount the state has contributed thus far.

- Salton Sea Restoration Act. In 2003, the Legislature ratified a collection of agreements—referred to as the Quantification Settlement Agreement (QSA)—that both reduced and reallocated the state’s share of Colorado River water. Because this agreement requires the transfer of water from primarily agricultural users in the Imperial Valley to other areas of Southern California, one result will be a reduction in the amount of agricultural runoff that historically has fed the Salton Sea—the state’s largest lake. Reducing this inflow is expected to dramatically shrink the lake (exposing toxic dry soils and damaging air quality) and increase its already high salinity levels (ruining the habitat for fish and migrating birds). As such, the state required that water continue to flow into the lake for several years so that a mitigation plan could be developed. The full transfers (and the corresponding decrease in runoff to the lake), however, are scheduled to begin phasing–in in 2017. As a component of the QSA, the state assumed responsibility for paying most of the costs to mitigate the air quality impacts resulting from the transfer. After many years of study and numerous proposals, in fall 2015 a task force convened by the Governor recommended steps for addressing the Salton Sea. These included an immediate short–term goal of undertaking 9,000 to 12,000 acres of habitat creation and dust suppression projects at the lake. The CNRA still is in the process of developing a long–term plan for managing the lake, along with associated funding estimates and sources. (Earlier proposals for restoring the lake had associated costs of several billions of dollars.) An earlier bond measure, Proposition 84, provided $47 million for initial restoration efforts and planning at the Salton Sea.