November 18, 2015

The 2016-17 Budget:

California's Fiscal Outlook

Executive Summary

In this report, we describe our office’s current projections for the state budget through 2016–17 and discuss the budget’s condition through 2019–20 under a few different scenarios.

Outlook Assumes Current Policies. To produce this report, we must make numerous assumptions about the future. One key assumption is that the state’s current revenue and spending policies stay in place. In making this assumption, we are not predicting that current policies will stay in place. The Legislature will—and should—change state policies in the future, consistent with its priorities. The projections in this report are intended to help the Legislature understand its fiscal flexibility in considering such changes.

The Budget Situation Through 2016–17: Decidedly Positive. The state budget is better prepared for an economic downturn than it has been at any point in decades. In 2015–16, we project that the state’s “Big Three” General Fund revenues—principally the personal income tax—will exceed June 2015 budget assumptions by $3.6 billion, with most of that gain to be deposited into the Proposition 2 rainy day fund. In 2016–17, we project that revenues will exceed spending under current policies, resulting in even further improvement in the state’s fiscal situation. Assuming no new budget commitments are made, we estimate 2016–17 would end with reserves of $11.5 billion. Of this total, the Legislature would have control over $4.3 billion in the Special Fund for Economic Uncertainties, the state’s traditional budget reserve, with the rest of the reserves held for future budget emergencies by Proposition 2.

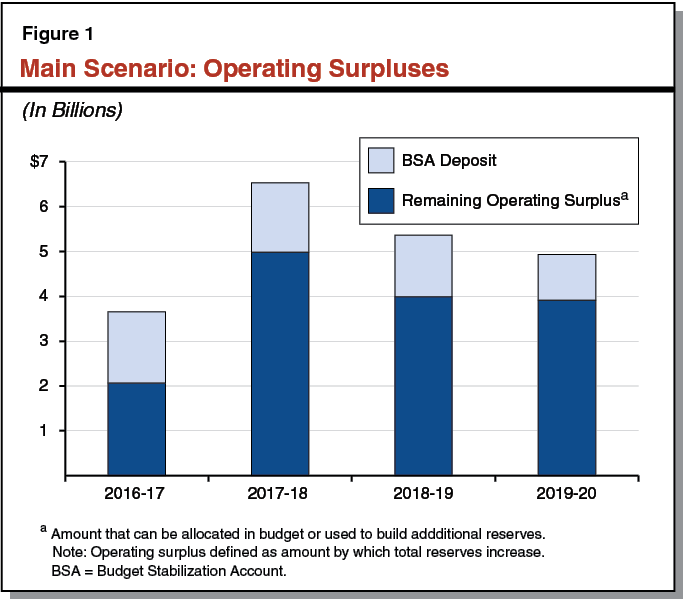

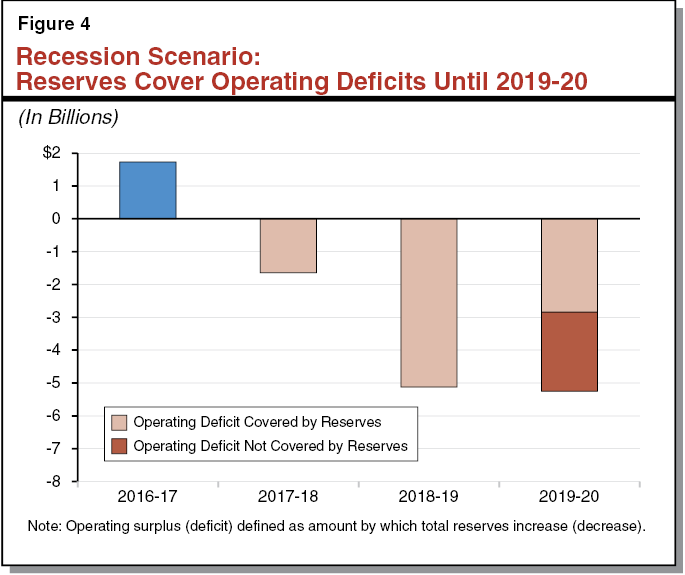

After 2016–17: Risks to Consider. The above estimates are based on our main economic scenario, which assumes the economy continues to grow through 2019–20. This scenario generates significant annual operating surpluses and budget reserves in future years. As such, the state has the capacity under this scenario to make some new budget commitments—whether spending increases or tax reductions. An economic or stock market downturn, however, is possible during our outlook period. To illustrate this economic uncertainty, we provide projections under alternative economic scenarios. Projected reserves provide a major cushion against such economic risks. The more new budget commitments are made in 2016–17, however, the more likely it is that the state would face difficult choices—such as spending cuts and tax increases—later. As such, the Legislature faces the fundamental trade–off between the benefits of new commitments now versus fewer difficult budget decisions later. A sizable reserve is the key to making it through the next economic downturn with minimal disruption to public programs.

Chapter 1: The General Fund Through 2016–17

This report summarizes our office’s assessment of California’s economy and budget condition. Our main economic scenario assumes the economy will continue to grow moderately, although many other scenarios—both stronger and weaker—are possible. In this chapter, we present our estimates of the near–term budget condition. In Chapter 2, we discuss key revenue trends and our assessment of the economy. Chapter 3 presents our main scenario outlook for state spending over the next few years. Finally, we discuss the longer–term outlook for the budget condition in Chapter 4. Because the current economic expansion will not last forever, in Chapter 4 we compare our main scenario to alternate sets of assumptions—including an economic slowdown and a recession. The nearby box discusses some key information needed to understand this report.

Keys to Understanding This Report

This Outlook Relies on Many Assumptions. In producing this report, we make assumptions about the future. Many of our decisions about which assumptions to include or exclude inherently involve judgment. As a result, different assumptions are also reasonable. Understanding our assumptions and their implications is crucial to understanding the limitations of this report.

Outlook Based on Current State Policies. Our outlook assumes the state’s current revenue and spending policies will remain in place. For example, we assume the temporary taxes passed by voters in Proposition 30 expire, consistent with current law. We also assume the continuation of recent budget practices, such as funding increases for universities and state employee pay increases. This does not mean we believe these policies will or should stay the same. On the contrary, the essence of budgeting is making year–to–year adjustments to spending to accommodate changing legislative priorities. As a result, our outlook is geared toward helping the Legislature think about its options for crafting a 2016–17 budget. Can it continue to afford its current policies? Can it afford additional commitments—whether they be one–time or ongoing spending increases or tax reductions?

Our Main Scenario Is One of Many Possible Scenarios. We develop economic scenarios in order to produce our budget outlook. Consistent with standard conventions in economic projections, our main scenario assumes that the economy continues to grow moderately through 2019–20. This, however, is only one of many possible scenarios. Because the current expansion will not last forever, we discuss alternative scenarios in Chapter 4, including: (1) a slowdown scenario in which the economy grows more slowly, and (2) a recession scenario. Future economic conditions, however, could be stronger than our main scenario or weaker than our recession scenario, resulting in very different budgetary outcomes.

Different Economic Outcomes Will Affect Future State Budgets. Spending in two programs, which accounts for over half of the General Fund’s budget, is calculated using formulas that rely on unpredictable economic variables. Specifically, Proposition 98 and Proposition 2 depend on fluctuations in state tax revenues and patterns in the stock market. Both of these variables are inherently volatile and unpredictable. As a result, these constitutional requirements—and therefore nearly half of the General Fund budget—cannot be predicted with any precision in the later years of our outlook.

Outlook for the 2016–17 Budget

Figure 1 displays our main scenario estimate of the General Fund condition through 2016–17. Based primarily on higher revenue estimates than were assumed in the 2015–16 Budget Act, our projections of reserve levels are much higher. We now estimate that 2015–16 will end with $7.9 billion in reserves, a $3.3 billion increase over the budget act’s assumptions. Assuming no new commitments are made in the 2016–17 budget, we estimate that reserves will increase to $11.5 billion at the end of 2016–17, up by $3.7 billion over 2015–16 levels. The $11.5 billion reserve would consist of $4.3 billion in the Special Fund for Economic Uncertainties (SFEU)—the state’s traditional budget reserve—and $7.2 billion in the Budget Stabilization Account (BSA). Below, we explain the basis for these estimates.

Figure 1

LAO General Fund Condition Under Main Scenarioa

(In Millions)

|

2014–15 |

2015–16 |

2016–17 |

|

|

Prior–year fund balance |

$5,253 |

$2,157 |

$3,210 |

|

Revenues and transfers |

112,244 |

116,315 |

123,183 |

|

Expenditures |

115,340 |

115,262 |

121,119 |

|

Ending fund balance |

$2,157 |

$3,210 |

$5,274 |

|

Encumbrances |

–$971 |

–$971 |

–$971 |

|

SFEU balance |

$1,186 |

$2,239 |

$4,304 |

|

Reserves |

|||

|

SFEU balance |

$1,186 |

$2,239 |

$4,304 |

|

BSA balance |

1,606 |

5,641 |

7,234 |

|

Total Reserves |

$2,793 |

$7,880 |

$11,537 |

|

aIncludes Education Protection Account created by Proposition 30 (2012). SFEU = Special Fund for Economic Uncertainties (the General Fund’s traditional budget reserve) and BSA = Budget Stabilization Account. |

|||

2015–16: $3.3 Billion Increase in Reserves

The improvement in the 2015–16 year–end reserves—$3.3 billion—is the result of the factors described below.

2014–15: $266 Million Net Erosion. Under the state’s complex accrual policies, revenue estimates for 2013–14 and 2014–15 continue to change. These revisions and others affect the current budget situation. The 2015–16 budget plan assumed that 2014–15 would end with an SFEU balance of $1.5 billion. We now estimate the SFEU balance at the end of 2014–15 was $1.2 billion, representing a $266 million erosion. This erosion is the combination of (1) $937 million higher revenues and transfers, (2) $889 million higher required General Fund spending on the Proposition 98 minimum guarantee for schools and community colleges, (3) $22 million lower net spending on other programs, and (4) a $337 million downward adjustment to the entering fund balance for 2014–15.

2015–16: $3.5 Billion Higher Revenues. The 2015–16 budget package assumed that receipts from the state’s “Big Three” revenues—the personal income tax (PIT), sales and use tax (SUT), and corporation tax (CT)—would total $113.3 billion in 2015–16. We now estimate that these revenues will total $116.8 billion, an increase of $3.6 billion. The difference is due to $4 billion higher PIT revenues, $269 million lower SUT revenues, and $144 million lower CT revenues. In addition, we estimate that other revenues and transfers—excluding the Proposition 2 BSA deposit—will be $100 million lower than 2015–16 budget assumptions.

Proposition 98 Less Sensitive to Changes in Revenues. The 2015–16 budget package assumed that the minimum guarantee would be $68.4 billion in 2015–16. We now estimate the guarantee to be $69.1 billion, an increase of $739 million. In recent years—most notably 2012–13 and 2014–15—incremental increases in state General Fund revenues have been almost entirely offset by higher required General Fund spending on Proposition 98. This was because maintenance factor was owed in these “Test 1” years, which can result in nearly a dollar–for–dollar increase in Proposition 98 spending relative to revenues. In 2015–16, Proposition 98 offsets comparably little of our higher revenue estimates because we estimate that the remaining maintenance factor is repaid and Proposition 98 spending is driven by changes in per capita personal income rather than state tax revenues. In addition, most of this increase is covered by our higher estimates of local property taxes. As a result, state General Fund costs increase only $27 million above budget assumptions.

Lower Net Spending Across Rest of the Budget ($134 Million). We estimate that spending on non–Proposition 98 programs would be net $134 million lower than June 2015 budget assumptions. Most notably, we estimate lower spending in Medi–Cal ($47 million) and California Work Opportunity and Responsibility to Kids (CalWORKs) ($90 million). We discuss these spending estimates in greater detail in Chapter 3.

Two–Thirds of Higher Revenues Deposited in BSA. Proposition 2—approved by the voters in 2014—changed state rules for budget reserves and requires the state to pay a minimum amount of debt each year through 2029–30. The June 2015 budget plan—which incorporated the Governor’s May 2015 revenue estimates—required $3.7 billion in total Proposition 2 payments (split evenly between BSA deposits and debt payments). Under Proposition 2’s “true up” provisions, the Legislature will revisit the 2015–16 estimates twice—in the 2016–17 and 2017–18 budgets. We now estimate total Proposition 2 requirements for 2015–16 to be $5.9 billion, requiring a $2.2 billion true up deposit to the BSA. This true up deposit brings the BSA balance to $5.6 billion at the end of 2015–16. (Our reading of Proposition 2’s true up provisions is based on our understanding of legislative intent. An alternate reading of the measure would result in a roughly $900 million smaller true up deposit.)

Main Scenario Outlook: 2016–17 Ends With $11.5 Billion Reserve

We estimate that growth in total General Fund revenues and transfers (5.9 percent) outpaces growth in General Fund spending (5.1 percent) in 2016–17. The difference between revenues and spending increases the SFEU balance by $2.1 billion in 2016–17. Accordingly, we estimate that the SFEU would end 2016–17 with $4.3 billion. In addition, based on our assumption of a somewhat weaker stock market, we estimate the Proposition 2 BSA deposit would be $1.6 billion in 2016–17. This would grow reserves in that fund to $7.2 billion. All told, we estimate that 2016–17 would end with $11.5 billion in total reserves, assuming no new fiscal commitments are made in or before next year’s budget.

Revenues and Transfers Grow 6 Percent. We estimate that revenues and transfers increase $6.9 billion, or 5.9 percent, in 2016–17. Revenues from the state’s three largest taxes collectively grow 3 percent in 2016–17 under our main scenario. This is mainly driven by our assumption of a somewhat weaker stock market, which results in just 3 percent growth in the PIT. In addition, we estimate that CT revenues grow nearly 5 percent, while SUT revenues grow modestly at under 2 percent due to the expiration of Proposition 30’s SUT rate increase. While we estimate that the state’s Big Three revenues grow only moderately, the year–over–year decrease in the size of the Proposition 2 BSA deposit increases total revenues and transfers, as shown in Chapter 2.

General Fund Spending Grows 5 Percent. Under our main scenario, General Fund spending grows by $5.9 billion, or 5.1 percent, in 2016–17. Nearly half of this is the result of significant growth in Medi–Cal costs. Specifically, we estimate that Medi–Cal expenditures will grow $2.5 billion, or 14 percent, in 2016–17. Of this increase, over $1 billion is explained by our assumption that the tax on managed care organizations expires after 2015–16. We also estimate that General Fund spending on Proposition 98 will increase by $770 million. In addition, legislation in 2014 changed state contributions to the California State Teachers’ Retirement System (CalSTRS), causing another $533 million increase in estimated General Fund spending.

LAO Comments

Bright 2016–17 Budget Outlook. It will be several months before the Legislature adopts a revenue estimate for the 2016–17 state budget. The interim period includes three key collection months for PIT revenues—December, January, and April. While the revenue picture will become clearer by June 2016, revenues could be a few billion dollars above or below our main scenario estimates. To provide a sense of the range of outcomes possible, we estimated total reserves assuming revenues were over $4 billion higher or lower than our main scenario estimates for 2014–15 through 2016–17 combined. Under these alternative assumptions, total reserves could lie between $8 billion and $15 billion at the end of 2016–17 assuming no new budget commitments were made. Our main scenario outlook for the 2016–17 budget is, therefore, decidedly positive.

The $11.5 billion in total reserves projected under our main scenario for the end of 2016–17 reflects the steady, significant progress that the state has made in improving its budget situation. Proposition 2’s rules require that nearly two–thirds of these reserves be held in the BSA solely for future budget emergencies. The Legislature, however, has complete control over the remaining $4.3 billion that we show as the SFEU balance.

Future Risks to Consider. As we describe in Chapter 4, if the economy continues to grow and no additional budget commitments are made, our main scenario suggests that the state budget would be in surplus through 2019–20. Various factors, however, could reduce or eliminate these surpluses. If the economy were weak, revenues could be billions of dollars below our main scenario estimates. If the state’s two key pension boards lower their assumptions concerning future investment returns, state contributions to the California Public Employees’ Retirement System and CalSTRS could be billions of dollars higher than our main scenario estimates by 2019–20. Prefunding retiree health care benefits for state employees could increase state General Fund costs by hundreds of millions of dollars. (We note, however, that Proposition 2 could help to absorb some of these retirement–related costs.) We describe these and other risks for the budget in greater detail in Chapter 4.

Key Considerations for 2016–17. The state is better prepared for an economic downturn than it has been at any point in decades. Given our estimates of state revenues, expenditures, and reserves, the state can generally maintain its current policies over the outlook period even under some more pessimistic economic scenarios. On the other hand, if the Legislature were to make new commitments in the 2016–17 budget, it would be more likely to face difficult choices—such as spending cuts and tax increases—later. As such, the Legislature is confronted with the fundamental trade–off between the benefits of new commitments now versus fewer difficult budget decisions later.

Chapter 2: The Economy and Revenues

The Economy

A budget outlook for California must make assumptions about the future of the economy. As discussed below, however, there are many uncertainties about the economy now (and, for that matter, at any given point in time). As such, our ability to make accurate “predictions” about the economy—difficult even in the near term—declines with each subsequent year in our fiscal outlook period. Especially for years shown after 2016, one should regard any multiyear economic projection in this publication, including our main scenario, merely as one of many possible scenarios. The key economic measures assumed in our main scenario through 2020 are summarized in Figure 1. Figure 2 compares the key variables in this main scenario with those from our office’s May 2015 main scenario and the administration’s May 2015 economic projections.

Figure 1

LAO Economic Assumptions: November 2015 Main Scenario

Percent Change Unless Otherwise Noted

|

United States |

2014 |

2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

2018 |

2019 |

2020 |

|

Real gross domestic product |

2.4% |

2.5% |

3.2% |

3.2% |

2.6% |

2.0% |

1.7% |

|

Personal income |

4.4 |

4.3 |

5.2 |

6.0 |

6.0 |

4.7 |

3.9 |

|

Wage and salary employment |

1.9 |

2.1 |

1.9 |

2.2 |

1.9 |

1.1 |

0.5 |

|

Unemployment rate (percent) |

6.2 |

5.3 |

5.0 |

4.7 |

4.5 |

4.6 |

4.8 |

|

Consumer price index |

1.6 |

0.2 |

2.1 |

2.8 |

3.1 |

2.8 |

2.4 |

|

Core PCE price index |

1.5 |

1.3 |

1.6 |

2.5 |

2.9 |

2.7 |

2.2 |

|

Federal funds rate |

0.1 |

0.2 |

0.9 |

2.3 |

3.8 |

3.7 |

3.7 |

|

Housing starts (thousands) |

1,052 |

1,183 |

1,466 |

1,697 |

1,626 |

1,535 |

1,602 |

|

S&P 500 (annual average) |

1,931 |

2,046 |

2,031 |

2,105 |

2,191 |

2,280 |

2,372 |

|

California |

2014 |

2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

2018 |

2019 |

2020 |

|

Personal income |

4.9% |

5.8% |

5.8% |

6.2% |

6.2% |

5.3% |

4.8% |

|

Wage and salary employment |

3.1 |

3.0 |

2.5 |

2.3 |

2.0 |

1.7 |

1.5 |

|

Unemployment rate (percent) |

7.5 |

6.3 |

5.5 |

5.0 |

4.6 |

4.5 |

4.5 |

|

Consumer price index |

1.8 |

1.7 |

2.1 |

2.8 |

3.1 |

2.8 |

2.4 |

|

Housing permits (thousands) |

85.1 |

98.3 |

98.3 |

100.8 |

103.8 |

106.9 |

110.1 |

|

Single–unit permits |

36.4 |

46.5 |

51.1 |

53.9 |

56.6 |

58.8 |

60.9 |

|

Multifamily permits |

48.6 |

51.7 |

47.2 |

46.9 |

47.2 |

48.2 |

49.2 |

|

Population growth |

0.9 |

0.9 |

0.8 |

0.7 |

0.7 |

0.7 |

0.7 |

|

Note: Based generally on Moody’s Analytics October 2015 U.S. macroeconomic outlook (“baseline” scenario). This November 2015 main scenario reflects a California state macroeconomic scenario developed by the LAO and lowers Moody’s Analytics’ (a) U.S. personal income growth outlook for 2015 through 2018 and (b) S&P 500 assumptions throughout the period beginning in late 2015. Core PCE = Personal consumption expenditures excluding food and energy. |

|||||||

Figure 2

Comparing Recent Economic Outlooks

|

2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

|||||||||

|

DOF May 2015 |

LAO May 2015 |

LAO Nov. 2015 |

DOF May 2015 |

LAO May 2015 |

LAO Nov. 2015 |

DOF May 2015 |

LAO May 2015 |

LAO Nov. 2015 |

|||

|

United States |

|||||||||||

|

Percent change in: |

|||||||||||

|

Real gross domestic product |

2.8% |

2.8% |

2.5% |

2.7% |

2.7% |

3.2% |

2.7% |

2.7% |

3.2% |

||

|

Personal income |

3.9 |

3.9 |

4.3 |

4.5 |

4.5 |

5.2 |

5.3 |

5.3 |

6.0 |

||

|

Wage and salary employment |

2.1 |

2.1 |

2.1 |

1.5 |

1.5 |

1.9 |

1.2 |

1.2 |

2.2 |

||

|

Consumer price index |

0.0 |

–0.4 |

0.2 |

2.2 |

2.1 |

2.1 |

2.1 |

2.4 |

2.8 |

||

|

Unemployment rate |

5.5 |

5.5 |

5.3 |

5.2 |

5.2 |

5.0 |

5.2 |

5.2 |

4.7 |

||

|

Federal funds rate |

0.3 |

0.3 |

0.2 |

1.2 |

1.2 |

0.9 |

2.9 |

3.0 |

2.3 |

||

|

S&P 500 (annual average) |

2,106 |

2,101 |

2,046 |

2,196 |

2,166 |

2,031 |

2,264 |

2,233 |

2,105 |

||

|

California |

|||||||||||

|

Percent change in: |

|||||||||||

|

Personal income |

4.8% |

4.7% |

5.8% |

5.2% |

5.3% |

5.8% |

5.1% |

6.0% |

6.2% |

||

|

Wage and salary employment |

2.6 |

2.9 |

3.0 |

2.4 |

2.2 |

2.5 |

2.3 |

1.8 |

2.3 |

||

|

Unemployment rate |

6.5 |

6.4 |

6.3 |

6.0 |

5.7 |

5.5 |

5.8 |

5.4 |

5.0 |

||

|

Housing permits (thousands) |

99 |

92 |

98 |

111 |

86 |

98 |

127 |

87 |

101 |

||

How Long Will Growth Continue?

All Budget Outlooks Based on Economic Assumptions. All projections of state revenues and expenditures rely—implicitly or explicitly—on many assumptions about the economy and demographics. Figure 1 displays the key economic assumptions in our main scenario. That scenario—consistent with standard convention—assumes economic growth through our multiyear outlook period ending in 2020. There is a good chance, however, that growth will stall before 2020. Even if growth continued throughout this period, its year–by–year pattern will vary significantly from today’s assumptions. As we discuss elsewhere in this publication, state budgetary conditions will differ—either positively or negatively—as a result of economic conditions that differ from our main scenario.

How Long Will Expansion Continue? As shown in Figure 3, the current economic expansion is the fifth longest on record in this country. Since World War II, U.S. expansions have tended to be longer than before. Still, history suggests we may now be past (or well past) the midpoint of the current economic expansion. There is no reliable tool to predict the timing or the severity of a recession far in advance. State leaders are advised to consider the possibility of a recession in the near future when finalizing any state budget plan.

Figure 3

Current Economic Expansion Already Among Longest in U.S. History

Data Since 1854

|

Economic Expansion |

Number of Months |

|

April 1991 to March 2001 |

120 |

|

March 1961 to December 1969 |

106 |

|

December 1982 to July 1990 |

92 |

|

July 1938 to February 1945 |

80 |

|

July 2009 to present |

77 (so far) |

|

December 2001 to December 2007 |

73 |

|

April 1975 to January 1980 |

58 |

|

April 1933 to May 1937 |

50 |

|

Average Economic Expansion, 1945 to 2009 |

58 |

|

Source: National Bureau of Economic Research. |

|

Other Challenges and Uncertainties

As discussed above, a major uncertainty is how long the current economic expansion will last. The California and U.S. economies also face a variety of major challenges and uncertainties that raise questions concerning future economic growth. These issues include:

- Aging. The population is aging rapidly. This has contributed to declining participation levels in the labor force. In future decades those declines may become more noticeable and dampen growth in economic output. What unanticipated economic changes will these major demographic shifts bring?

- Energy. With much of the world, California is changing how it consumes energy to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, with both costs and benefits for the state. How will these changes play out here and elsewhere?

- China and the Global Economy. The economic health of China—a growth powerhouse in recent years—is in question, with possible effects (both positive and negative) for other parts of the global economy. What will happen to growth in China? As growth there wanes, will it cause limited or more significant economic effects here in California?

- Federal Policies. In 2016, voters will elect a new President and a new Congress. Will the 2016 elections pave the way for major changes in corporate tax, defense, immigration, or trade policies? Will there be major changes to federal health care policies? Will the campaign introduce other major new proposals that could affect the economy?

- Wages and Incomes. Significant increases in minimum wages are under consideration at the federal, state, and local levels here in California and elsewhere. At the same time, many are concerned about limited wage growth for middle–income families. How will public policy changes to address these issues affect the economy?

- Monetary Policy and Growth. In 2008, responding to the collapse of the world economy, the Federal Reserve lowered its federal funds rate—one of its key monetary policy instruments—to essentially zero. It has remained at that level ever since. This has been an unprecedented period for monetary policy, so it is difficult to know what will happen as the federal funds rate is raised (beginning in December, in our assumptions). Our main scenario assumes inflation levels that are somewhat higher than the Federal Reserve’s targets for a few years as monetary policy aims to stimulate employment and wage growth. Some think that the anticipated tightening of monetary policy will dull future growth in what they view as an already fragile economy.

- The Bay Area and Housing. As discussed in more detail below, California’s economy currently is quite reliant on growth in the San Francisco–Oakland and San Jose metropolitan regions, where home prices and rents have risen markedly recently. What will happen when recent strong growth in the Bay Area subsides? There and elsewhere, what will happen to demand and supply in California’s housing sector?

All economic projections, including our own, rely on past data and experience to estimate what will unfold in the future. Therefore, new trends and unprecedented changes, such as some of those listed above, may limit the reliability of economic projections.

The Bay Area

California’s economy and the state budget now are quite reliant on the San Francisco Bay Area, as discussed below.

Now Among Nation’s Leading Regions for Job Growth. As summarized in Figure 4, parts of the Bay Area have led the state in job growth over the past year. Unemployment rates there are below the rest of the state. As we have discussed recently on our office’s California Economy and Taxes blog (accessible from the LAO home page), the San Jose metropolitan area’s job growth rate has ranked first among all large metro areas in the nation over the past year. California’s job growth has been fairly strong recently, and that is largely because of the robust growth in the Bay Area’s technology sector.

Figure 4

Recent Job Data for Largest Metropolitan Areas

Not Seasonally Adjusted Data, as of September 2015

|

Region |

Counties in Region |

Job Growth Over Past Year |

Unemployment Rate |

|

San Jose MSA |

Santa Clara/San Benito |

4.8% |

3.7% |

|

San Francisco MDa |

San Francisco/San Mateo |

4.7 |

3.1 |

|

San Rafael MDa |

Marin |

4.5 |

3.1 |

|

San Diego MSA |

San Diego |

3.5 |

4.6 |

|

Anaheim MDb |

Orange |

3.0 |

4.0 |

|

California |

Statewide |

2.9 |

5.5 |

|

Inland Empire MSA |

Riverside/San Bernardino |

2.8 |

6.1 |

|

Sacramento MSA |

Sacramento/El Dorado/Placer/Yolo |

2.6 |

5.2 |

|

Fresno MSA |

Fresno |

2.5 |

8.1 |

|

Oakland MDa |

Alameda/Contra Costa |

2.1 |

4.3 |

|

Los Angeles MDb |

Los Angeles |

2.0 |

6.2 |

|

United States |

Nationwide |

1.9 |

4.9 |

|

Oxnard–Thousand Oaks–Ventura MSA |

Ventura |

1.5 |

5.3 |

|

Bakersfield MSA |

Kern |

–0.2 |

8.4 |

|

aThis metropolitan division (MD) is a part of the San Francisco–Oakland Metropolitan Statistical Area (MSA). bThis MD is a part of the Los Angeles–Long Beach–Anaheim MSA. Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. |

|||

Residents Pay Significant Share of State Taxes. As shown in Figure 5, the per capita (per person) personal income taxes (PIT) assessed on Bay Area residents far exceed those of any other large region in the state. Currently, on a per capita basis, Bay Area tax filers pay more than double the statewide average. Put another way, the Bay Area’s population totals 17 percent of the statewide total, but its residents paid 36 percent of the state’s PIT in 2013. The key reason for this is that Bay Area residents’ average incomes and effective tax rates are well above statewide averages. Under California’s income tax structure, higher–income people pay higher marginal tax rates on their income.

Figure 5

California Personal Income Tax (PIT) Base Varies Regionally

2013 Data, Residents’ Tax Returns

|

Region |

Per Capita PIT Assessed |

Total Tax Assessed (Billions) |

Total Adjusted Gross Income (Billions) |

Average Effective Tax Rate |

Population (Millions) |

|

San Francisco/Oakland/San Jose MSAs |

$3,119 |

$19.9 |

$314.3 |

6.3% |

6.38 |

|

Orange County |

1,724 |

5.3 |

102.0 |

5.2 |

3.10 |

|

Statewide |

1,460 |

55.7 |

1,109.5 |

5.0 |

38.16 |

|

Ventura County |

1,360 |

1.1 |

25.2 |

4.5 |

0.84 |

|

San Diego County |

1,355 |

4.3 |

91.0 |

4.7 |

3.18 |

|

Los Angeles County |

1,345 |

13.5 |

267.3 |

5.0 |

10.01 |

|

Central Coasta |

1,208 |

1.7 |

36.6 |

4.6 |

1.40 |

|

Napa, Solano, and Sonoma Counties |

1,187 |

1.3 |

29.4 |

4.3 |

1.05 |

|

Sacramento MSA |

964 |

2.1 |

54.9 |

3.9 |

2.20 |

|

North Stateb |

542 |

0.7 |

20.9 |

3.2 |

1.22 |

|

San Joaquin Valleyc |

541 |

2.2 |

67.0 |

3.3 |

4.07 |

|

Riverside and San Bernardino Counties |

530 |

2.3 |

77.5 |

3.0 |

4.34 |

|

Other residentsd |

— |

1.3 |

23.6 |

5.6 |

— |

|

aIncludes Monterey, San Luis Obispo, Santa Barbara, and Santa Cruz Counties. bIncludes all counties north of San Francisco, Napa, Sonoma, Vallejo–Fairfield, and Sacramento MSAs. cIncludes Fresno, Kern, Kings, Madera, Merced, San Joaquin, Stanislaus, and Tulare Counties. dIncludes California resident tax returns with (1) an address in another California county or (2) an out–of–state address. Returns with out–of–state addresses collectively had $1.1 billion of tax assessed, with an average effective tax rate of 6.5 percent. Excludes nonresident tax returns, which collectively had $2.3 billion of tax assessed. MSA = metropolitan statistical area. |

|||||

When Will Growth Subside? Given California’s economic and fiscal reliance on the Bay Area, a key question now arises: when will the Bay Area’s current, technology–fueled growth subside? Moreover, when growth subsides, will it merely slow down or will it undergo a more severe downturn akin to what happened after the dot.com bubble burst nearly 15 years ago? Finally, as growth subsides, will other large regions, especially Los Angeles, be poised for stronger growth that helps pick up the Bay Area’s slack? Our main scenario is consistent with a slowdown in Bay Area economic growth, but a more severe downturn could put more strains on the economy than we now assume.

Housing

Trends in housing costs affect every Californian and many aspects of state and local budgets. Trends in home buying and rents, therefore, may affect the pace and length of California’s current economic expansion. As we discuss below, there are some key uncertainties about the future of California’s housing market.

Continued Growth in House Prices and Rents. California’s house prices have risen rapidly in recent years, as demand for housing has far outpaced its supply. Since bottoming out in late 2011, California’s median house price has increased by 45 percent—or about 10 percent per year—reaching around $450,000 as of September 2015. House price growth, however, appears to have moderated during the past year. House prices increased by 5 percent over the past 12 months, compared to 13 percent in 2014 and 17 percent in 2013. Despite this slowdown, California’s house prices are still growing slightly faster than the rest of the country.

Rents also have been on the rise in California, albeit at a somewhat slower pace than house prices. California’s median rent rose from around $1,200 in 2011 to around $1,350 in 2014, an increase of 13 percent. Rents have risen somewhat slower than prices in recent years in part because rents did not decline as much as prices did during the Great Recession. Rents, therefore, have experienced less of a rebound than house prices.

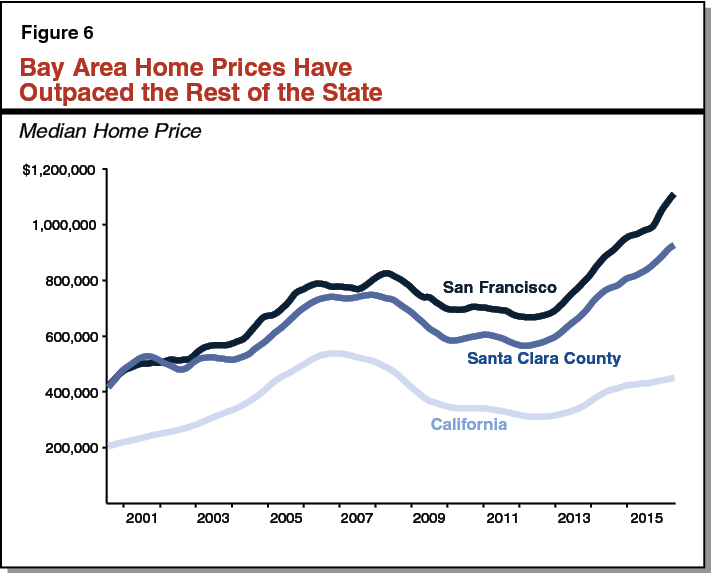

Bay Area Has Experienced Exceptional Growth in Prices and Rents. House prices and rents have increased significantly faster in the Bay Area than in the rest of the state. Figure 6 shows the 15–year trend of median home prices in San Francisco and in Santa Clara County, which includes San Jose. Median house prices in San Francisco ($1.1 million) and Santa Clara County ($926,000) grew by 15 percent and 13 percent, respectively, over the past year. Since 2011, house prices in these counties have grown by over 60 percent. Rents in San Francisco and Santa Clara similarly rose by over 30 percent between 2011 and 2014.

Building Remains Below Historical Levels Despite Price and Rent Growth. Residential building permits appear to be on pace to total roughly 98,000 in 2015, a notable increase over building levels in the prior two years (around 85,000 per year). Despite this increase, residential building remains below historical levels, as well as below what recent population growth would suggest. During the 2000s, building permits averaged 146,000 units per year. Our main scenario assumes permits will continue to climb over the next few years, but remain below historical levels. It is not entirely clear why building has not returned to historical levels. Several factors, however, likely play some role. Data suggests that household formations—for example, when younger people move out of parents’ homes—have fallen in recent years. As discussed in our March 2015 report, California’s High Housing Costs: Causes and Consequences, it is also possible that local government resistance to building is preventing developers from increasing production of new housing. Some reports also suggest that builders are experiencing labor shortages in certain markets.

Pluses and Minuses for Government Budgets and Economy. Recent growth in house prices and rents has contributed to robust growth in state and local revenues—particularly property taxes. Statewide assessed property values increased by 6 percent in both 2014–15 and 2015–16, compared to an average annual rate of less than 0.5 percent over the preceding five years. We anticipate this robust growth to continue in the near term, with assessed values projected to grow by just over 6 percent in 2016–17.

Nonetheless, high house prices and rents present some risks to the state’s economy. Rising housing costs force Californians to spend more of their income on housing, leaving less available for other purchases. High housing costs also can deter workers from moving to the state’s most productive regions—where housing costs tend to be the highest—constraining business recruitment and expansion. In the long term, future growth in the economy and state and local revenues could be dampened if new housing production continues to fall short of demand.

Revenues

Figure 7 summarizes our main scenario revenue outlook for California’s General Fund through 2019–20. Figure 8 shows how our key revenue numbers differ from June 2015 state budget assumptions (which were based on the Governor’s May 2015 revenue estimates). Below, we discuss some key issues concerning (1) the personal income tax (PIT), which generates about two–thirds of General Fund revenues, and (2) the state’s other key taxes.

Figure 7

LAO Revenue Summary: November 2015 Main Scenario

General Fund and Education Protection Account Combined (Dollars in Millions)

|

2014–15 |

2015–16 |

2016–17 |

2017–18 |

2018–19 |

2019–20 |

|

|

Personal income tax |

$76,400 |

$81,676 |

$84,274 |

$88,946 |

$90,057 |

$91,122 |

|

Sales and use tax |

23,709 |

24,971 |

25,351 |

25,980 |

26,808 |

28,091 |

|

Corporation tax |

9,714 |

10,198 |

10,685 |

10,842 |

11,089 |

11,557 |

|

Subtotal, “Big Three” Revenues |

($109,823) |

($116,844) |

($120,311) |

($125,768) |

($127,953) |

($130,770) |

|

Percent growth from prior year |

11.8% |

6.4% |

3.0% |

4.5% |

1.7% |

2.2% |

|

Insurance tax |

$2,444 |

$2,493 |

$2,582 |

$2,682 |

$2,796 |

$2,903 |

|

Other revenues |

1,993 |

2,094 |

1,727 |

1,889 |

1,990 |

2,090 |

|

Transfers to Budget Stabilization Account |

–1,606 |

–4,035 |

–1,593 |

–1,550 |

–1,368 |

–1,016 |

|

Other net transfers in (out)a |

–409 |

–1,082 |

156 |

0 |

–34 |

–257 |

|

Total Revenues and Transfers |

$112,244 |

$116,315 |

$123,183 |

$128,789 |

$131,337 |

$134,490 |

|

Proposition 2 Inputs |

||||||

|

Taxes on capital gains |

N/A |

$13,940 |

$12,488 |

$12,604 |

$11,990 |

$10,557 |

|

As percent of General Fund taxes |

N/A |

11.6% |

10.1% |

9.7% |

9.1% |

7.8% |

|

aFor 2016–17 through 2019–20 (unlike prior fiscal years), no special fund loan repayments are included in this line as transfers out. To the extent those repayments are to be made in future years, they are assumed to occur as Proposition 2 debt payment expenditures. |

||||||

Personal Income Tax

Our main scenario PIT estimates continue to be higher than the administration’s projections from earlier this year, as summarized in Figure 8.

Figure 8

Comparing Key LAO and Administration Revenue Numbers

General Fund and Education Protection Account Combined (In Millions)

|

2014–15 |

2015–16 |

2016–17 |

|||||||||

|

LAO Nov. 2015 |

Admin. June 2015 |

Change |

LAO Nov. 2015 |

Admin. June 2015 |

Change |

LAO Nov. 2015 |

Admin. June 2015 |

Change |

|||

|

Personal income tax |

$76,400 |

$75,384 |

$1,016 |

$81,676 |

$77,700 |

$3,976 |

$84,274 |

$81,652 |

$2,623 |

||

|

Sales and use tax |

23,709 |

23,684 |

25 |

24,971 |

25,240 |

–269 |

25,351 |

25,761 |

–410 |

||

|

Corporation tax |

9,714 |

9,809 |

–94 |

10,198 |

10,342 |

–144 |

10,685 |

11,073 |

–388 |

||

|

“Big Three” Revenues |

$109,823 |

$108,877 |

$946 |

$116,844 |

$113,281 |

$3,564 |

$120,311 |

$118,485 |

$1,825 |

||

Historical Growth Patterns. The PIT generally is the key revenue source to consider when thinking about the prospects for state revenue growth. We estimate that the PIT grew by an extraordinary 14 percent in 2014–15, with an additional 7 percent increase now expected for 2015–16. Since 2000–01, the annual growth of PIT has, on average, been about 5 percent. (This calculation includes some tax policy changes that have occurred, as well as two recessions.) PIT growth has exceeded 5 percent in eight fiscal years since 2000–01 and fallen short of that threshold in seven years. Those seven years include ones affected by (1) the bust of the dot.com stock bubble in the early 2000s, (2) the bust of the housing bubble in the mid–2000s and the subsequent recession, and (3) the decline in taxable income in 2013 (associated with the federal “fiscal cliff”) when high–income taxpayers accelerated financial transactions to 2012 in order to avoid later federal tax increases. Accordingly, in a year unaffected by an income tax cut, an economic slowdown, or a stock market drop, the state’s elected leaders reasonably can expect something like 5 percent (or more) PIT growth.

Slow Growth Assumed for 2016–17. Our main scenario anticipates slower PIT growth in 2016–17—only 3.2 percent. The key underlying reason for the slow growth rate in our 2016–17 PIT estimate is our assumption about stock prices. Specifically, we assume that the average closing price of the S&P 500 stock index during the current quarter will be 1,993—below the 2,100 level posted for much of early 2015. This level was consistent with the S&P 500 index as of October 14, when we were finalizing our main scenario assumptions. With the price–to–earnings ratio of the S&P 500 now above 20—somewhat high historically, but below some prior “bubble” periods—we assume very slow future growth of stock prices, consistent with our practices in recent years. Under our main scenario, therefore, the S&P 500 does not return to the 2,100 level until the middle of 2017. This causes our estimate of net capital gains income on California resident tax returns to fall from around $150 billion in 2015 to around $130 billion in each of the next three years. That drop in capital gains—resulting from our S&P 500 stock price assumption—causes our slow estimated PIT growth rate for 2016–17.

The assumed trend for wage income offsets somewhat the impact of our capital gains assumptions. Wages make up the large majority of taxable income, and our main scenario assumes robust growth in wages and salaries reported on California PIT returns of about 7 percent per year in 2016 and 2017.

It is impossible to predict future stock and capital gains growth and difficult to precisely project wage growth. Therefore, actual PIT results in 2016–17 (and even 2015–16) could result in revenues being billions of dollars above or below our main scenario estimates. Yet, in fulfilling its constitutional responsibility to determine a state revenue estimate annually for the budget, the Legislature must make assumptions about wages and uncertain stock prices and capital gains taxes.

Scheduled Expiration of Proposition 30. Proposition 30’s temporary PIT rate increases on the highest–income Californians expire at the end of 2018. As a result, 2018–19 essentially reflects a half year of those revenues in our main scenario, and 2019–20 includes no Proposition 30 PIT revenues. (The scheduled expiration of Proposition 30’s sales tax rate increase slows anticipated revenue growth in 2016–17 and 2017–18, as discussed below.) In this main scenario, with continuing economic growth, there continues to be no “cliff effect” as Proposition 30 revenues end. The expiration of Proposition 30 slows, but does not stop, PIT growth in our main scenario. If, however, an economic slowdown were to occur around 2019, the fall off of Proposition 30 revenues would exacerbate any slowdown or decline in PIT revenues.

As this publication was being drafted, initiative proposals to extend Proposition 30’s PIT increases were being introduced. This publication’s scenarios, however, all assume that Proposition 30 expires because that is the tax policy in current state law.

Other Key Taxes

While legislative discussions about revenue estimates recently have focused on the PIT, the two other key state taxes—the sales and use tax (SUT) and the corporation tax (CT)—together make up around one–third of General Fund revenues. As such, the SUT and CT also play important roles in determining the state’s annual revenue estimate.

Sales and Use Taxes. Estimated General Fund SUT revenue totaled $23.7 billion in 2014–15, $25 million higher than the amount assumed in the state’s 2015–16 budget plan. In our main scenario, SUT revenues grow to $25.0 billion in 2015–16, about $270 million lower than the assumption in the 2015–16 budget. Under this scenario, SUT revenues then grow more slowly as the one–quarter cent Proposition 30 SUT increase ends in December 2016. This results in slower General Fund SUT growth—around 2 percent per year—over the next two fiscal years, with this revenue source totaling an estimated $25.4 billion in 2016–17 and $26.0 billion in 2017–18.

Starting in 2014–15, certain sales of manufacturing or research and development equipment became exempt from the General Fund portion of the SUT. The administration initially projected that the new exemption would reduce General Fund revenue by $486 million in 2014–15 and by more than $500 million in subsequent years. The administration’s current estimate for 2014–15 is $128 million—about one–quarter of the amount initially projected. Our main scenario assumes that this amount grows to slightly less than $200 million per year in 2015–16 and 2016–17.

Corporation Taxes. While CT revenues have steadily grown since the 2011–12 fiscal year, the 2015–16 budget plan appears to have overestimated CT revenues in 2014–15 and, we expect, in 2015–16 as well. CT revenues totaled an estimated $9.7 billion in 2014–15, about $100 million less than the budget assumption. This was due largely to several hundred million dollars in refund settlements over the past several months. (Under the state’s complicated process for accruing, or assigning, revenues to specific fiscal years, these refunds generally are accrued to prior fiscal years.) While the refunds were not entirely unexpected, it is very difficult to predict their timing. In our main scenario, CT revenues are projected to total $10.2 billion in 2015–16, about $150 million below the 2015–16 budget assumption. That discrepancy, however, is relatively small, and estimated year–to–year growth in CT revenues currently reflects a fairly healthy and growing economy.

Corporate profits and CT revenue have both grown rapidly since the last recession. Our main scenario assumes that the rate of growth in corporate profits will slow considerably for several years beginning in 2017. This causes estimated CT revenue to grow relatively slowly after 2016–17, but these growth trends may differ substantially from actual results for a variety of reasons. In particular, there are many factors that determine the total amount of CT revenue in any year, including the use of tax deductions and tax credits. Two tax provisions in particular can have an enormous effect on final tax collections: net operating loss deductions and research tax credits. Each of these reduces aggregate tax liabilities by more than $1 billion per year. Corporations’ use of these provisions in any given year is highly uncertain and highly variable, and each can increase or reduce CT revenue from one year to another by hundreds of millions of dollars.

Litigation. There are always major revenue–related lawsuits and tax agency proceedings that affect state revenues. At the time this report was prepared, the state was awaiting an upcoming state Supreme Court decision concerning the apportionment of income between states by multi–state corporations. If the state loses that lawsuit, its potential liability could be hundreds of millions of dollars or more. (A recent state disclosure to bond investors said the potential exposure to refund claims in this case could exceed $750 million.) On the other hand, a recent appellate opinion could require health plans (such as Blue Shield and Anthem Blue Cross) to start paying the state’s insurance tax, with some net revenue gain possible for the General Fund. In cases like these, it is difficult to know how soon revenue gains or losses will materialize for the state. Large tax cases tend to result in long appeals and multiple proceedings spread out over many years. Our main scenario assumes no changes to state revenue due to these or other ongoing lawsuits and tax agency proceedings.

Chapter 3: Spending Outlook

Main Scenario Estimates Reflect Economic Assumptions. Figure 1 displays our main scenario spending estimates through 2019–20. Our main scenario assumes that current spending laws and policies are not changed and that the economy grows steadily throughout the period. Should the economy fall into recession in the next few years, or if the economic growth pattern differs from our assumptions, spending in many programs could be very different. For example, state spending on Proposition 98 education programs depends on changes in personal income (a broad measure of the economy), local property taxes, and state General Fund revenues. Because we cannot precisely “predict” how these factors will change, Proposition 98 spending in the future could be quite different from that shown in the figure.

Figure 1

General Fund Spending Under LAO Main Scenario

Includes Education Protection Account (Dollars in Millions)

|

Estimates |

Outlook |

Average Annual Growtha |

||||||

|

2014–15 |

2015–16 |

2016–17 |

2017–18 |

2018–19 |

2019–20 |

|||

|

Education Programs |

||||||||

|

Proposition 98b |

$50,497 |

$49,444 |

$50,213 |

$52,110 |

$52,376 |

$52,992 |

1.7% |

|

|

UC |

2,991 |

3,136 |

3,261 |

3,391 |

3,527 |

3,668 |

4.0 |

|

|

CSU |

2,763 |

2,988 |

3,121 |

3,257 |

3,393 |

3,534 |

4.3 |

|

|

Student Aid Commission |

1,527 |

1,614 |

1,786 |

1,935 |

2,045 |

2,160 |

7.6 |

|

|

Child carec |

822 |

942 |

950 |

965 |

984 |

1,005 |

1.7 |

|

|

Health and Human Services |

||||||||

|

Medi–Cal |

17,521 |

17,993 |

20,504 |

20,915 |

22,567 |

24,133 |

7.6 |

|

|

CalWORKs |

619 |

588 |

266 |

178 |

135 |

127 |

–31.9 |

|

|

SSI/SSP |

2,790 |

2,811 |

2,846 |

2,883 |

2,920 |

2,958 |

1.3 |

|

|

IHSS |

2,193 |

2,802 |

2,788 |

2,883 |

3,008 |

3,140 |

2.9 |

|

|

DDS |

3,130 |

3,496 |

3,550 |

3,651 |

3,760 |

3,920 |

2.9 |

|

|

DSH |

1,498 |

1,537 |

1,542 |

1,546 |

1,551 |

1,551 |

0.2 |

|

|

Other major programsd |

1,997 |

2,173 |

2,159 |

2,168 |

2,184 |

2,199 |

0.3 |

|

|

CDCR |

9,499 |

9,530 |

9,500 |

9,523 |

9,549 |

9,568 |

0.1 |

|

|

Judiciary |

1,409 |

1,511 |

1,515 |

1,548 |

1,580 |

1,613 |

1.7 |

|

|

CalSTRS |

1,486 |

1,935 |

2,468 |

1,728 |

1,674 |

1,679 |

–3.5 |

|

|

Infrastructure Debt Servicee |

5,250 |

5,353 |

5,602 |

5,524 |

6,083 |

6,041 |

3.1 |

|

|

Proposition 2 Debt Paymentsf |

— |

227 |

1,593 |

1,550 |

1,368 |

1,016 |

— |

|

|

Other Programs |

9,347 |

7,183 |

7,454 |

8,048 |

8,642 |

9,272 |

6.6 |

|

|

Totals |

$115,340 |

$115,262 |

$121,119 |

$123,804 |

$127,345 |

$130,575 |

3.2% |

|

|

Percent change |

— |

–0.1% |

5.1% |

2.2% |

2.9% |

2.5% |

— |

|

|

aFrom 2015–16 to 2019–20. bReflects the General Fund component of the Proposition 98 minimum guarantee. Average annual growth in the minimum guarantee—the General Fund and local property tax revenue combined—is 2.9 percent over the period. c Stage 1 child care costs included in CalWORKs. A portion of State Preschool costs is reflected in Proposition 98. d Includes DHCS family health and state operations, DPH, DCSS, and DSS programs not itemized above. Smaller health and human services programs are included in “other programs.” eDebt service on general obligation and lease–revenue bonds generally used for infrastructure. Does not include: (1) lease–revenue debt service for community colleges, which is included under Proposition 98, or (2) UC’s and CSU’s debt service, which is included in their respective line items. fFor 2015–16, includes $96 million UC pension payment, $84 million loan repayment to the Transportation Investment Fund, and $47 million in interest on special fund loans. Other Proposition 2 debt payments in 2015–16 are reflected in revenues and transfers. Beginning in 2016–17, reflects our estimate of debt payments required under Proposition 2. The Legislature could choose to spend these amounts on additional special fund loan repayments, Proposition 98 “settle–up,” or paying down unfunded liabilities for pension and retiree health benefits. IHSS = In–Home Supportive Services; DDS = Department of Developmental Services; DSH = Department of State Hospitals; DHCS = Department of Health Care Services; DPH = Department of Public Health; DCSS = Department of Child Support Services; and DSS = Department of Social Services. |

||||||||

Moderate Spending Growth Under This Scenario. Under our main scenario, General Fund spending increases over the period at an average annual rate of 3.2 percent. Two key programs—Proposition 98 and Medi–Cal—experience very different growth patterns. General Fund spending on Proposition 98 programs grows slowly over the period at an average annual rate of 1.7 percent, largely due to two factors. First, the gradual expiration of Proposition 30’s temporary taxes slows General Fund revenue growth over four fiscal years. Second, healthy growth in local property taxes offset state spending on Proposition 98. On the other hand, our main scenario reflects 7.6 percent average annual growth on Medi–Cal, the second largest General Fund program. The growth patterns in these two key programs explain the moderate General Fund spending growth reflected in our main scenario.

Education

Education Spending. In this section, we focus on Proposition 98, the universities, student financial aid programs, and child care programs. The Proposition 98 section estimates combined spending for a large portion of the state’s subsidized preschool program, elementary and secondary education (commonly referred to as K–12 education), and the California Community Colleges. The next section estimates spending for the University of California and the California State University. The financial aid section estimates spending for the Cal Grant program, Middle Class Scholarships, and a few small specialized programs. The last section estimates spending for the rest of the state’s preschool program as well as child care programs.

Proposition 98

Proposition 98 Minimum Guarantee for Schools and Community Colleges. State budgeting for schools and community colleges is governed largely by Proposition 98, passed by voters in 1988. The measure, modified by Proposition 111 in 1990, establishes a minimum funding requirement, commonly referred to as the minimum guarantee. Both state General Fund and local property tax revenue apply toward meeting the minimum guarantee. In addition to Proposition 98 funding, schools and community colleges receive funding from the federal government, other state sources (such as the lottery), and various local sources (such as parcel taxes).

Calculating the Minimum Funding Guarantee. The Proposition 98 minimum guarantee is determined by one of three tests set forth in the State Constitution (see Figure 2). These tests depend upon several inputs, including changes in K–12 average daily attendance (ADA), per capita personal income, and per capita General Fund revenue. Though the calculation of the minimum guarantee is formula–driven, a supermajority of the Legislature can vote to suspend the formulas and provide less funding than they require. This happened in 2004–05 and 2010–11. In some cases, including as a result of a suspension, the state creates an out–year obligation referred to as a “maintenance factor.” The state is required to make maintenance factor payments when year–to–year growth in state General Fund revenue is relatively strong. Though in most years the state has provided an amount at or close to the minimum guarantee, the state has discretion to provide any amount above the minimum guarantee.

Figure 2

Constitution Sets Forth Three Tests for Calculating Proposition 98 Minimum Guarantee

|

Test 1—Share of General Fund. Ensures Proposition 98 programs receive at least 40 percent of state General Fund revenue. This test applies only when it results in a higher funding level than Test 2 or Test 3. Test 1 has been operative 4 of the last 27 years. |

|

Test 2—Growth in Personal Income. Adjusts prior–year Proposition 98 funding for changes in K–12 attendance and per capita personal income. This test applies when higher than Test 1 but lower than Test 3. Test 2 has been operative 14 of the last 27 years. |

|

Test 3—Growth in General Fund Revenue. Adjusts prior–year Proposition 98 funding for changes in K–12 attendance and per capita General Fund revenue. This test applies when higher than Test 1 but lower than Test 2. Test 3 has been operative 7 of the last 27 years. |

|

Note: In 2 of the last 27 years, the state suspended Proposition 98. |

2014–15 and 2015–16 Updates

2014–15 Minimum Guarantee Up $1.3 Billion From Budget Act Estimate. Of this amount, $889 million is covered by state General Fund and $409 million by higher local property tax revenue. Test 1 remains the operative test in 2014–15. Test 1, when coupled with maintenance factor application, results in the minimum guarantee going up virtually dollar for dollar with increases in General Fund revenue. As shown in Figure 3, the $904 million increase in applicable state General Fund revenue increases the minimum guarantee by $889 million. Part of this increase results from a higher required maintenance factor payment ($541 million). The remainder of the increase in the guarantee is due to an upward revision in local property tax estimates. A portion of the property tax revision ($243 million) is due to an increase in the amount of ongoing revenue shifted to schools and community colleges from the dissolution of redevelopment agencies. (The state dissolved these agencies in 2011 and provided for a gradual shift of their revenue to schools and other local governments as their debts are retired.) Higher–than–expected collections from several smaller components of property tax revenue account for the remainder of the increase. Although local property tax revenue normally offsets the General Fund share of Proposition 98 funding, Test 1 years are exceptions, with Proposition 98 funding increasing with increases in local revenue.

Figure 3

Updating Estimates of 2014–15 and 2015–16 Minimum Guarantees

(Dollars in Millions)

|

2014–15 |

2015–16 |

||||||

|

2015–16 Budget Plan |

November LAO Estimate |

Change |

2015–16 Budget Plan |

November LAO Forecast |

Change |

||

|

Minimum Guarantee |

|||||||

|

General Fund |

$49,608 |

$50,497 |

$889 |

$49,416 |

$49,444 |

$27 |

|

|

Local property tax |

16,695 |

17,104 |

409 |

18,993 |

19,704 |

711 |

|

|

Totals |

$66,303 |

$67,601 |

$1,298 |

$68,409 |

$69,148 |

$739 |

|

|

Key Information |

|||||||

|

General Fund tax revenuea |

$112,068 |

$112,972 |

$904 |

$116,619 |

$120,119 |

$3,500 |

|

|

K–12 average daily attendance |

5,994,522 |

5,981,073 |

–13,449 |

5,995,889 |

5,974,494 |

–21,395 |

|

|

Operative test |

1 |

1 |

— |

3 |

2 |

— |

|

|

Maintenance factor paid |

$5,402 |

$5,942 |

$541 |

— |

$195 |

$195 |

|

|

aReflects General Fund revenue that counts toward the Proposition 98 calculation. |

|||||||

Spike Protection Results in Smaller Increase to Ongoing Funding Level. In most years, Proposition 98 funding builds upon the level provided in the prior year. This dynamic means that increases in the guarantee in one year usually carry forward and result in a comparable increase the next year. In 2014–15, however, only the increase associated with the maintenance factor payment carries forward into 2015–16. The remaining increase is excluded due to a provision in the State Constitution known as spike protection. This is intended to prevent very large one–time spikes in revenue from increasing the guarantee to an unsustainably high level moving forward. Since its adoption in 1990, spike protection has been applied to the guarantee twice (in 2012–13 and 2014–15).

2015–16 Minimum Guarantee Up $739 Million From Budget Act Estimate. Two main factors account for this increase. First, the $541 million maintenance factor payment from 2014–15 carries forward, increasing the 2015–16 guarantee by a similar amount. Second, we estimate that General Fund revenue is up $3.5 billion compared with the budget plan estimate. With Test 2 projected to be operative, the guarantee is determined largely by growth in per capita personal income and is not directly affected by changes in General Fund revenue. The additional revenue does, however, require the state to make a $195 million maintenance factor payment. Upon making this payment, the state will have eliminated its entire maintenance factor obligation, ending the year with no maintenance factor outstanding for the first time since 2005–06.

Further Changes in Revenue Would Have Little Effect on 2015–16 Guarantee. In 2015–16, the guarantee is relatively insensitive to changes in revenue. Under our main scenario, with Test 2 the operative test and no further maintenance factor payments required, the 2015–16 guarantee no longer depends directly on growth in state revenue. We estimate that General Fund revenue could increase by as much as $8 billion above our projections with no corresponding increase in the guarantee. Conversely, General Fund revenue could fall below our projections by as much as $4 billion with the only Proposition 98 effect being that the state no longer would be required to make the remaining $195 million maintenance factor payment in 2015–16. This dynamic contrasts notably with the situation in 2014–15, under which the guarantee changes nearly dollar for dollar with any change in state General Fund revenue.

Virtually All $739 Million Increase Covered With Higher Property Tax Revenue. Though the 2015–16 guarantee is up $739 million, the General Fund share of the guarantee is up only $27 million. Increases in local property tax revenue cover the remaining $711 million increase. About half of this amount ($334 million) is due to higher–than–expected ongoing revenue from the dissolution of redevelopment agencies. The remainder is due primarily to higher assessed property values. Whereas the budget plan assumed assessed values would grow statewide by 5.5 percent, the latest available data from county assessors indicates that the increase will be about 6 percent.

Drop in K–12 ADA Frees Up Some Funding Within Guarantee. Compared to budget act assumptions, we estimate K–12 ADA has fallen by about 13,000 in 2014–15 and by about 21,000 in 2015–16. Due to a two–year hold harmless provision in the State Constitution, these ADA declines do not affect the guarantees in 2014–15 and 2015–16. The ADA drops, however, reduce the cost of many educational programs, including the Local Control Funding Formula (LCFF), thereby freeing up roughly $300 million across the two years for other Proposition 98 priorities.

About $2.3 Billion Available for One–Time Purposes. For 2014–15 and 2015–16 combined, the minimum guarantee has increased a total of $2 billion (see Figure 3). Given the 2014–15 fiscal year is already over and districts are well into their 2015–16 fiscal year, this additional funding in practical terms is available for one–time purposes. Combined with the $300 million in ADA–related savings from 2014–15 and 2015–16, the state has about $2.3 billion to allocate for its one–time priorities. Over the past few years, the state has used one–time funding to support a range of activities including (1) implementation of the Common Core State Standards, (2) career technical education, (3) teacher training and support, and (4) paying down several outstanding K–14 obligations. As of the 2015–16 budget plan, the state had retired some of these latter outstanding obligations but had not entirely paid down the K–14 mandates backlog. In recent years, the state has reduced the K–14 mandates backlog considerably (by more than $4 billion), but we estimate the state still has an unaudited backlog of about $2 billion ($1.7 billion for schools and $300 million for community colleges).

2016–17 Budget Planning

2016–17 Guarantee $2.3 Billion Higher Than Revised 2015–16 Guarantee. We project the minimum guarantee will grow from $69.1 billion in 2015–16 to $71.4 billion in 2016–17, an increase of $2.3 billion (3.3 percent). Test 3 is operative, with the change in the guarantee driven primarily by projected growth in per capita General Fund revenue. Other factors affecting the guarantee include a slight decline in K–12 attendance (0.3 percent) and the requirement for the state to make a $618 million supplemental payment. (A state law requires a supplemental payment whenever Test 3 is operative and Proposition 98 funding would otherwise grow less quickly than the rest of the state budget.) Given the guarantee is still growing more slowly than our projected 5.3 percent growth in per capita personal income, the state creates a $1.1 billion maintenance factor obligation.

Two–Thirds of Increase Covered With Higher Local Property Tax Revenue. Of the $2.3 billion increase in the 2016–17 guarantee, the General Fund share is $770 million. A $1.5 billion increase in local property tax revenue covers the remainder of the increase in the guarantee, with local property tax revenue up 7.8 percent over the 2015–16 level. Two main factors account for this increase:

- Assessed Property Values Projected to Grow at Relatively Strong Rate. We project assessed values will increase by 6.3 percent in 2016–17, largely reflecting the strong recovery in the housing market that has occurred over the past several years. This growth rate equates to a $1.1 billion increase in local property tax revenue for schools and community colleges.

- Final Shift of Revenue From End of “Triple Flip.” The triple flip is phasing out during the 2015–16 fiscal year, with the associated local property tax revenue beginning to flow back to schools and community colleges. The total revenue involved is about $1.6 billion on an ongoing basis. Schools and community colleges will receive $1.2 billion of this amount in 2015–16 and the remainder (about $400 million) in 2016–17. (The triple flip was a complex financing mechanism under which the state diverted local sales tax revenue to pay off certain state bonds, backfilled cities and counties with property tax revenue, and backfilled schools and community colleges with state General Fund.)

$3.6 Billion Available for Proposition 98 Priorities in 2016–17 Under Main Scenario. As shown in Figure 4, the 2015–16 Budget Act included $68.4 billion in spending to meet the minimum guarantee (as estimated at that time). Of this amount, $67.9 billion was ongoing spending and $551 million was one–time spending. Given projected growth in the 2016–17 guarantee to $71.4 billion, the state has $3.6 billion available for its 2016–17 Proposition 98 priorities.

Figure 4

$3.6 Billion Increase in Proposition 98 Funding Projected for 2016–17

LAO Main Scenario (In Millions)

|

2015–16 Budget Act Spending Level |

$68,409 |

|

Back out one–time actions: |

|

|

Secondary school career technical education grantsa |

–$250 |

|

CCC mandate backlog |

–117 |

|

CCC maintenance and instructional equipment |

–100 |

|

K–12 Internet infrastructure grants |

–50 |

|

K–12 mandate backlog |

–31 |

|

CCC Cal Grant B administration |

–3 |

|

Total One–Time Actions |

–$551 |

|

2015–16 Ongoing Spending |

$67,858 |

|

Annualize preschool slotsb |

$31 |

|

New Funds Available in 2016–17c |

$3,558 |

|

2016–17 Minimum Guarantee |

$71,447 |

|

a In 2015–16, this program received an additional $150 million from one–time funds. b Funded beginning January 1, 2016. c The state has committed to spend $300 million in 2016–17 for the second year of the secondary school career technical education grants. The state could cover this cost using any available Proposition 98 funding from any fiscal year. |

|

2016–17 Guarantee Is Somewhat Sensitive to Changes in State General Fund Revenue. Whereas the 2014–15 guarantee was highly sensitive to changes in state General Fund revenue and the 2015–16 guarantee is highly insensitive to changes, the 2016–17 guarantee is moderately sensitive. Relative to our main scenario, a $1 increase or decrease in General Fund revenue in 2016–17 would cause a corresponding increase or decrease in the guarantee of about 50 cents. If General Fund revenue were to increase by $2 billion above our main scenario, the guarantee would increase by about $1 billion. (If revenue were to increase beyond this level, however, the guarantee would be unlikely to increase further. This is because Test 2 would become operative, with the guarantee then linked to per capita personal income rather than state revenue.) If General Fund revenue were to decline by $5 billion from our main scenario, the guarantee would decline by about $2.5 billion, dropping below the prior–year funding level.

In Past Several Years, State Has Minimized Risk by Designating Some Funding for One–Time Activities. Given the difficulty of predicting recessions, stock market slowdowns, and other events that can reduce General Fund revenue, the state over the past few years has dedicated some available Proposition 98 funding to one–time activities. If the guarantee falls below projections, the expiration of prior–year, one–time funding provides a buffer, reducing the likelihood of potential cuts to ongoing K–14 programs. Allocating a portion of available funding for one–time priorities would mitigate the effect of a decline in the guarantee from 2016–17 to 2017–18. For example, under the recession scenario we discuss in Chapter 4, General Fund revenue declines by nearly $8.5 billion (7 percent) from 2016–17 to 2017–18. (By comparison, during the last two recessions, the state experienced much larger year–over–year declines.) Under the recession scenario, the 2017–18 guarantee would experience a year–over–year decline of $4.6 billion. If the state were to designate some available 2016–17 funding for one–time activities, it would reduce the magnitude of potential reductions to ongoing programs in 2017–18.

Outlook for Later Years

Although both the Legislature and schools likely view near–term Proposition 98 issues as the most pressing, a number of significant issues unfold over the forecast period. Most notably, these issues include the phase out of the Proposition 30 taxes, the phase in of LCFF funding increases, and the cost pressures associated with increased contributions to the California State Teachers’ Retirement System (CalSTRS). Members of the Legislature also have asked whether a deposit in the state school reserve might occur in the coming years, thereby triggering the associated caps on school district reserve levels. Below, we describe the Proposition 98 outlook through 2019–20 under our main scenario and examine the above issues in more detail.

Under Main Scenario, Guarantee in 2019–20 More Than $8 Billion Higher Than 2015–16. Figure 5 shows our Proposition 98 projections under our main scenario from 2015–16 through 2019–20. As shown in the figure, Proposition 98 funding grows from $69.1 billion in 2015–16 to $77.5 billion in 2019–20, an annual average growth rate of 2.9 percent. General Fund costs grow more slowly, from $49.4 billion in 2015–16 to $53 billion in 2019–20. This slower growth in the General Fund share of Proposition 98 results from the relatively fast growth in local property tax revenue, which increases from $19.7 billion in 2015–16 to $24.5 billion in 2019–20. The average annual growth over the period is 1.7 percent for the General Fund and 5.6 percent for local property tax revenue.

Figure 5

Proposition 98 Outlook

LAO Main Scenario (Dollars in Billions)

|

2015–16 |

2016–17 |

2017–18 |

2018–19 |

2019–20 |

|

|

Minimum Guarantee |

|||||

|

General Fund |

$49.4 |

$50.2 |

$52.1 |

$52.4 |

$53.0 |

|

Local property tax |

19.7 |

21.2 |

22.5 |

23.4 |

24.5 |

|

Totals |

$69.1 |

$71.4 |

$74.6 |

$75.8 |

$77.5 |

|

Change From Prior Year |

|||||

|

Total guarantee |

$1.5 |

$2.3 |

$3.2 |

$1.2 |

$1.6 |

|

Percent change |

2.3% |

3.3% |

4.4% |

1.6% |

2.2% |

|

General Fund |

–$1.1 |

$0.8 |

$1.9 |

$0.3 |

$0.6 |

|

Percent change |

–2.1% |

1.6% |

3.8% |

0.5% |

1.2% |

|

Local property tax |

$2.6 |

$1.5 |

$1.3 |

$1.0 |

$1.0 |

|

Percent change |

15.2% |

7.8% |

5.9% |

4.3% |

4.4% |

|

Maintenance Factor |

|||||

|

Amount created (+)/paid (–) |

–$0.2 |

$1.1 |

$0.1 |

$2.6 |

$2.1 |

|

Total outstandinga |

— |

$1.1 |

$1.3 |

$4.0 |

$6.3 |

|

Operative Test |

2 |

3 |

3 |

3 |

3 |

|

Growth Rates |

|||||

|

K–12 average daily attendance |

–0.1% |

–0.3% |

–0.3% |

–0.5% |

–0.3% |

|

Per capita personal income (Test 2) |

3.8 |

5.3 |

4.9 |

5.6 |

5.3 |

|

Per capita General Fund (Test 3)b |

5.9 |

2.7 |

4.4 |

1.6 |

2.1 |

|

K–14 cost–of–living adjustment |