May 12, 2009

Department of Real Estate:

Opportunities to Improve Consumer Protection

Executive Summary

(Short video summary)

In California, there are approximately 533,000 state–licensed real estate agents and brokers. Californians rely on these licensees to provide sound advice in millions of real estate transactions annually, valued in the billions of dollars. The mission of the Department of Real Estate (DRE) is to protect consumers in real estate transactions by ensuring that licensees are competent and trustworthy, investigating consumer complaints, and taking disciplinary actions against licensees who violate the law. The department is also responsible for protecting consumers through consumer education.

In this report, we identify a number of deficiencies in the department’s Licensing and Education Program and Enforcement and Recovery Program that we have concluded reduce the overall level of protection being provided to real estate consumers. For example, our review finds that there is (1) a mismatch between the educational requirements for entry into the real estate field and the broad range of activities authorized by the license, (2) a lack of focus in the department’s enforcement activities on real estate transaction crimes, and (3) an onerous and time–consuming process for taking disciplinary actions against licensees who violate the law.

To address these concerns, we offer a series of recommendations, summarized in Figure 1, for the Legislature’s consideration. Our recommendations would: tighten existing educational requirements, increase licensee accountability for violations of the real estate law, improve department accountability for program outcomes, and expand consumer access to—as well as oversight of—the Recovery Account, which was established to enable consumers to recover damages resulting from fraud by real estate licensees.

Figure 1

Summary of LAO Recommendations for Improving

Real Estate Consumer Protection |

|

Tighten Education Requirements |

Require study on upgrading education requirements. |

Require continuing education to be completed annually. |

Require continuing education course providers to electronically submit student information. |

Strengthen Enforcement of Real Estate Law |

Reduce Commissioner’s burden of proof in administrative hearings. |

Expand sanctions available to Commissioner. |

Establish minimum standards for criminal convictions. |

Require report on SAFE Act implementation. |

Increase Department Accountability |

Require report on program measures. |

Update Consumer Education Materials |

Develop plan to expand and update materials. |

Expand Access to and Oversight of Recovery Account |

Eliminate requirement for civil judgment or restitution order in certain cases. |

Establish Recovery Account as stand-alone fund. |

Introduction

In California, there are approximately 533,000 state–licensed real estate agents. These licensees assist Californians in millions of real estate transactions annually valued in the billions of dollars. The primary mission of DRE is to protect the public in real estate transactions. This report examines the department’s licensing and enforcement programs to determine the department’s effectiveness in protecting consumers. We first provide background information on the licensing and enforcement programs, then discuss our findings and offer recommendations to improve the effectiveness and efficiency of these programs.

Licensing Real Estate Agents and Brokers

The primary mission of the DRE is to protect consumers from unskilled, incompetent, or unethical real estate practitioners. The department carries out this mission through its Licensing and Education, Enforcement and Recovery, and Subdivisions programs:

- The Licensing and Education Program processes applications for licensure—mainly as real estate agents and brokers—and conducts examinations to ensure that individuals who wish to enter the business meet specific statutory requirements.

- The Enforcement and Recovery Program conducts audits of licensees, investigates complaints, and prosecutes licensees in cases of unprofessional conduct.

- The Subdivisions Program issues public reports with relevant information on subdivided lands for sale.

This report focuses on the licensing and enforcement components of the department’s mission.

Figure 2 shows the number of positions and amount of spending associated with each of these programs in 2008–09. In total, the department has 336 staff positions and a budget of about $45 million to support its operations in 2008–09.

Figure 2

Department of Real Estate

Summary of 2008‑09 Operations |

(Dollars in Millions) |

Programs |

Personnel-Years |

Expenditures |

Licensing and Education |

62.2 |

$9.4 |

Enforcement and Recovery |

168.4 |

28.2 |

Subdivisions |

53.8 |

7.1 |

Administration (distributed) |

51.6 |

— |

Totals |

336.0 |

$44.7 |

Real Estate Fund. The DRE’s expenses are covered entirely by industry fees (primarily license and examination fees). Revenues from these fees are deposited into the Real Estate Fund to support department operations. A portion of the revenues, however, is set aside in two subaccounts: the Education and Research Account, and the Recovery Account. Specifically, up to 8 percent of license fee revenues may be deposited into the Education and Research Account to support education and research to advance the field of real estate. Another 12 percent of license fee revenues is required to be deposited into the Recovery Account to compensate victims of fraud by real estate licensees.

Real Estate Law. The state’s Real Estate Law, as it is generally known, exists primarily for the protection of the public in real estate transactions involving the services of an agent. To this end, it establishes the department and the Commissioner as executive director of the department, as well as rules that govern the qualifications and conduct of licensees. The law, among other things, requires the Commissioner to enforce its provisions and grants him/her the authority to take disciplinary actions against licensees who violate the law. In particular, the Commissioner may revoke or suspend a license, or issue a monetary penalty for noncompliance with the law.

Licensing and Education

Real Estate Salesperson and Broker Licenses. California, like most other states, issues two types of real estate licenses: the salesperson and broker licenses. Both licenses have a four–year term. State law establishes the education and training requirements for each license, as shown in Figure 3. The key function of the Licensing and Education Program is to ensure that individuals who work in the real estate industry meet these requirements. To this end, the program’s main activities are to process applications for original and renewal licenses (including verifying that the applicant completed the required courses), administer state licensing examinations, issue licenses, and certify courses for continuing education. The department also publishes educational brochures and other materials for licensees and consumers.

Figure 3

Current Requirements for Real Estate

Salesperson and Broker Licenses |

Salesperson License |

|

Broker License |

18 years of age |

|

18 years of age |

Proof of legal residence in the United States |

|

Proof of legal residence in the United States |

Criminal background check |

|

Criminal background check |

9 units (semester) in Real Estate |

|

24 units (semester) in Real Estate |

Passage of written state examination |

|

Passage of written state examination |

|

|

Two years experience as a licensed salesperson

(or a bachelor’s degree) |

|

|

|

Required Courses |

|

Required Courses |

Real Estate Practice |

|

Real Estate Practice |

Real Estate Principles |

|

Legal Aspects of Real Estate |

One course from list below: |

|

Real Estate Appraisal |

— Legal Aspects of Real Estate |

|

Real Estate Financing |

— Real Estate Appraisal |

|

Real Estate Economics or Accounting |

— Real Estate Financing |

|

Three courses from list below: |

— Real Estate Economics or Accounting |

|

— Advanced Legal Aspects of Real Estate |

— Business Law |

|

— Advanced Real Estate Finance |

— Escrows |

|

— Advanced Real Estate Appraisal |

— Property Management |

|

— Business Law |

— Real Estate Office Administration |

|

— Escrows |

— Mortgage Loan Brokering and Lending |

|

— Real Estate Principles |

|

|

— Property Management |

|

|

— Real Estate Office Administration |

|

|

— Mortgage Loan Brokering and Lending |

Both license types authorize the holder to engage in the full range of real estate transactions. However, the salesperson license permits licensed activity only while in the employ of a broker. The specific activities authorized by the licenses are property management, real property sales (including sales of residential, commercial, and industrial properties, as well as raw land), mortgage loan brokerage services, mortgage lending, loan servicing, and escrow services.

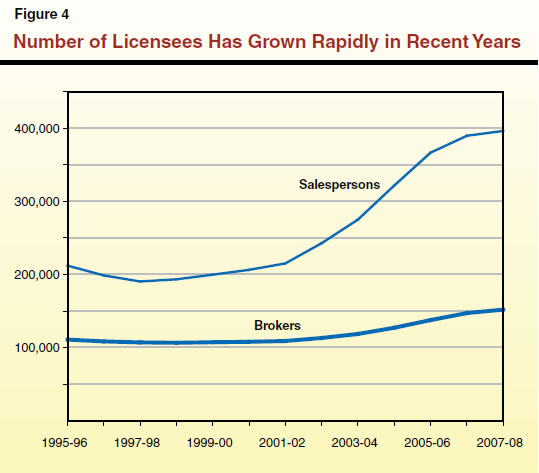

Licensing Workload. As of December 2008, there were approximately 533,000 real estate licensees. Of this number, about 153,000 were brokers, and 380,000 were salespersons. As Figure 4 shows, beginning in about 2001–02, California experienced a major influx of individuals into the real estate business. This surge in licensees generally coincided with the uptick in the residential real estate market. Since 2001–02, DRE has issued on average about 57,000 new licenses a year—more than 2.5 times the number issued annually in the preceding six–year period. The total licensed real estate workforce grew from 324,000 (in 2001–02) to 542,000 licensees (in 2007–08), an increase of 218,000 licensees, or 67 percent. The total licensees peaked at about 549,000 in November 2007. Recent data show that the number of real estate licensees has since started to decline, in response to the downturn in the real estate market. For example, at the end of December 2008, the 533,000 licensees represented a 3 percent decline from the peak reached 13 months earlier.

Enforcement and Recovery

Under state law, the Real Estate Commissioner is responsible for enforcing all real estate laws “in a manner that achieves maximum protection” (emphasis added) for the public. The Commissioner, who functions as the director of DRE, has the authority to investigate the real estate activities of any licensee or person conducting business that requires a real estate license. If the Commissioner determines a violation of the Real Estate Law has occurred, he/she may—after an administrative hearing—suspend or revoke the real estate license.

The main activities of the program include: (1) investigations of applicants and licensees with criminal convictions, (2) investigations of written consumer complaints, (3) proactive audits and investigations of licensees, and (4) formal disciplinary actions against licensees who violate the law. The department has 168 staff to carry out these activities, with a budgeted support level of $28 million in 2008–09.

The Recovery Account. The Recovery Account is a subaccount of the Real Estate Fund established to pay consumers who are victims of licensee fraud, misrepresentation, or deceit for any “actual and direct loss” resulting from a real estate transaction. Under current law, a person who wins a monetary judgment against a real estate licensee based on a loss suffered because of a fraud committed by the licensee may file a claim with DRE for payment from the Recovery Account. However, the individual must first seek to recover payment directly from the licensee and any other responsible party. A portion of the annual license fee revenue collected from real estate licensees is deposited into the account to pay such claims.

Real Estate Consumer Protection Needs Improvement

Overall, our review of the Licensing and Education Program, as well as the Enforcement and Recovery Program shows that there are significant deficiencies in both programs. In the Licensing and Education Program, for example, we find that there is a mismatch between the education requirements and the knowledge and skills actually needed to practice real estate. As regards the Enforcement and Recovery Program, our review finds that most of DRE’s investigations and disciplinary actions do not involve violations of the real estate law or involve real estate transactions. In the following section, we discuss in detail these and other concerns we have identified regarding the way DRE performs these important functions. Our findings are based on academic research, department data, and discussions with department staff and other experts in the real estate field.

Licensure Little Guarantee Of Competency

The purpose of licensure is to ensure that individuals who practice in the profession of real estate are qualified and competent. This is why license applicants are required to complete a certain minimum level of real estate education, and, in some cases (such as for the broker license), have specific work experience in the industry. The state, by granting the license, in effect assures consumers that license holders possess the requisite knowledge and skills deemed necessary by the state to competently handle the myriad of real estate transactions for which a license is required. However, our review suggests there is a fundamental mismatch between the educational requirements for the license and the knowledge and skills actually needed to practice real estate.

State Law and Exam Only Require Rudimentary Understanding of Real Estate. Our review indicates that the DRE’s education requirements—particularly for the salesperson license—cover only the basics of real estate. Specifically, the three courses (nine units) required for the salesperson license consists of two required introductory courses in real estate and one elective course in a chosen area of focus—for example, property management. In general, these survey courses touch briefly on key topics of the broad field of real estate, with an emphasis on residential sales. The state exam for a salesperson similarly is designed to require prospective licensees to demonstrate only a basic understanding of real estate with an emphasis on residential sales.

Real Estate License Covers Many Activities. In contrast with the limited scope of DRE’s real estate educational requirements and testing, the real estate licenses issued by DRE authorize individuals to engage in a broad range of activities, including some specialties and types of transactions that require a relatively high level of expertise to competently advise and protect a consumer. In particular, real estate finance and mortgage loan brokerage, are examples of areas of real estate practice that have become very complex, with the availability of a multitude of financing options and products. Many real estate licensees provide this service, with some even working exclusively in mortgage brokerage services. Yet, there is no requirement that licensees wishing to offer (or specialize in) mortgage loan brokerage services take a related course. Moreover, the state examination—for both the salesperson and broker license—is not designed to test competency in this aspect of real estate transactions.

No Experience Required for Some Real Estate Broker Applicants. The real estate profession relies heavily on the expertise and experience of, as well as supervision by, real estate brokers. In order to be licensed as a real estate broker, individuals are generally required to take more real estate courses than required for the salesperson license, pass a more difficult state examination, and have at least two years of full–time real estate experience. However, some applicants for the broker license, notably individuals with a bachelor’s degree (or higher) from an accredited college or university, are exempt from the experience requirement. Therefore, an individual with a bachelor’s degree and no related work experience conceivably could complete the required real estate courses, pass the state broker’s examination, and open a real estate brokerage firm in less than one year.

Concerns With Continuing Education Requirements

Real estate licensees are required to complete 45 hours of continuing education to renew the four–year license. The department’s key responsibilities related to continuing education are to (1) review and approve courses for continuing education credit and (2) enforce the requirement of 45 hours of such coursework. Licensees who fail to complete the continuing education courses must cease to conduct business upon expiration of their license. The objective is to ensure that licensees remain up to date on practices and related laws in the real estate business. The requirement is particularly important in light of the limited education and experience required to obtain the license. We identified two weaknesses in the way the state implements the continuing education requirement for real estate professionals. One is related to the term of the license and the other to the department’s process of verifying completion. We discuss these weaknesses below.

Continuing Education Is Not Continual. California’s real estate license is a four–year license. As noted above, under current practice, licensees are allowed up to four years to complete the required 45 hours of continuing education. The courses can be taken any time within the four–year period; therefore, a licensee could conceivably wait until the fourth year of the license before taking any continuing education courses. When this occurs, it works against the primary objective of the continuing education requirement which is to protect consumers by requiring licensees to remain up to date on practices and laws in the real estate business. Because the educational requirements for entry to the field are fairly minimal, it seems particularly important that continuing education be carried out throughout the four–year period. Notably, California is one of only three states that offer a four–year license. (The others are Georgia and Arizona.) Most states offer a two–year license, and thus require licensees to complete continuing education requirements within a shorter period.

Continuing Education Verification Process Lacking. Each continuing education course approved by DRE is assigned a unique eight–digit code. Upon completion of a DRE–approved course, licensees typically receive a certificate that includes the course code. Then, as part of the license renewal application, DRE requires licensees to provide the course code, date, and location of the course, and certify under penalty of perjury that the information is true. The department checks the information supplied by the licensee against information in its database regarding the course code and where and when the course is offered. If the information matches, the licensee is presumed to have successfully completed the course. This process, however, does not attempt to ascertain if the licensee actually completed the required course.

Moreover, the process is vulnerable to cheating because any licensee who actually completes a continuing education course can share with others the information required to claim credit for the course. This loophole in the verification process potentially allows licensees to evade the continuing education requirements intended to protect consumers.

Broad Scope of License Presents Challenge for Enforcement

Mortgage Loan Brokerage Difficult to Regulate. California is unique in that real estate licensees are authorized to serve as a mortgage broker who, in addition to facilitating the sale of real property, can also negotiate loans secured by liens on real property. In most other states, mortgage brokers are regulated by the state’s banking departments rather than their real estate regulators. This is because historically mortgage loan brokerage has been regarded as more of a financial service than a real estate service.

In recent years, particularly in the years leading up to and immediately following the subprime mortgage fallout, the DRE experienced an increase in the number of complaints related to mortgage brokers and has attempted to respond by focusing its enforcement efforts on licensees who provide those services. However, it has real challenges in doing so effectively. That is because all licensees can engage in any of the activities authorized by the license—including mortgage loan brokerage—yet most are not required to provide ongoing reports on the nature of their real estate practices. As a result, the department does not know at any given time how many of its licensees are providing these services. Therefore, it can neither assess the overall level of risk to consumers nor determine the best allocation of its enforcement resources.

Federal Legislation Would Improve State Oversight of Mortgage Brokers.

In July 2008, the U.S. Housing and Economic Recovery Act was signed into law. Title V of the act, known as the Secure and Fair Enforcement for Mortgage Licensing Act of 2008 (or SAFE Act), establishes a national licensing and registration system for “loan originators.” While key implementation details are still being worked out by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, the act has the potential to improve the regulation of mortgage brokers in California, and in so doing provide a higher level of consumer protection. The act requires mortgage brokers to complete pre–license and continuing education specific to mortgage loan brokerage, which is not required under current state law. The act also calls for the creation of a database of individuals who provide mortgage loan brokering services that would allow state regulators to more effectively monitor the activities of mortgage brokers. We discuss the federal legislation in detail in the text box below.

Federal Law Sets New Rules for Mortgage Brokers The Secure and Fair Enforcement for Mortgage Licensing Act of 2008 (or SAFE Act) was enacted in response to problems related to the subprime mortgage crisis. The measure aims to strengthen consumer protections in the real estate lending market by creating a single Internet–based licensing system that would be used by all states to license individuals as loan originators. Key Provisions of the SAFE Act of 2008 As some of its key provisions, the SAFE Act: - Requires Mortgage Brokers to Be Licensed as Loan Originators. The act prohibits individuals from engaging in mortgage loan brokerage activities without first becoming licensed as a “loan originator.” The act defines a loan originator as any individual who (1) takes a residential loan application, and (2) offers or negotiates the terms of a residential mortgage loan for compensation or gain. It does not include clerical or administrative staff, or an individual or entity that only provides real estate sales services.

- Establishes National Mortgage Licensing System and Registry. The act encourages states, in consultation with the Conference of State Bank Supervisors and the American Association of Residential Mortgage Regulators, to establish a national mortgage licensing system that would be used by state regulatory agencies to license and register loan originators. Individuals wishing to become licensed as a loan originator in any state would apply and annually register using the Internet–based system. States retain authority to approve, deny, suspend, or revoke licenses for loan originators.

- Sets Minimum Licensing Standards for Loan Originators. At a minimum, individuals are required to: (1) complete 20 hours of pre–license education; (2) pass a written examination; (3) submit fingerprints to the Federal Bureau of Investigations for a background check; and (4) show financial responsibility through a surety bond, net worth statement, or by contributing to a state fund. In order to renew the license, individuals would be required to annually complete eight hours of continuing education. States could enact higher licensing standards for loan originators.

- Provides HUD “Backup Authority” for Noncompliant States. Under the act, California has until July 2009 to comply with the act, but may request an extension of up to two years from the secretary of the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD). In the event a state does not comply, the HUD secretary has the authority to establish a system for individuals in non–compliant states to meet the licensing and registration requirements of the act.

Licensing of Mortgage Loan Brokers in California California, like most other states, already regulates mortgage lending activities covered by the federal act. There are four licenses under which an individual (or entity) can legally provide some level of mortgage brokerage services. These are the real estate salesperson and broker licenses administered by DRE, and the finance lender license and residential mortgage broker licenses administered by the Department of Corporations (DOC). While DRE licenses individuals, the DOC mostly licenses entities. The SAFE Act would require DRE licensees, as well as some individuals who are employed by the entities licensed by DOC, to become licensed under the act. Under the SAFE Act, some employees of state–chartered banks and credit unions are also required to register. |

Most Investigations Do Not Involve Real Estate Transactions

As discussed earlier, the Enforcement and Recovery Program investigates three types of cases: (1) consumer complaints, (2) so–called “rap cases,” and (3) petitions for reinstatement of a license that previously has been restricted or suspended. The consumer complaint investigations focus on alleged violations of the Real Estate Law by a licensee or unlicensed individual. These typically involve consumer allegations of fraud or dishonesty by a licensee in a real estate transaction.

A rap case is an investigation into a licensee or applicant who has pled guilty or no contest to a charge, or been found guilty or convicted of a felony or another type of crime “substantially related to the qualifications, functions, and duties of a real estate licensee.” Rap cases most often do not involve crimes committed as part of a real estate transaction, but rather involve a variety of misdemeanors and felonies, including such crimes as driving under the influence of alcohol, domestic violence, or petty theft. Many rap cases involve a license applicant (rather than a licensee) and thus are concerned primarily with who is allowed to obtain a license. Consumer complaints, in contrast, focus on monitoring real estate transactions by those who already have a license. An individual whose license has been suspended or restricted may petition the Commissioner for full reinstatement of the license.

How Does DRE Track Criminal Convictions? Under current law, applicants for an original real estate license are required to provide fingerprints for a criminal background check by the State Department of Justice (DOJ). They are also asked to provide information regarding any prior convictions on the license application. Any convictions revealed in the application or by the criminal background check would trigger a rap investigation. The DOJ also uses the fingerprints provided at the time of application to notify DRE of any subsequent arrests or convictions by licensees.

Our review of department workload data shows that in recent years investigations of rap cases have accounted for the majority of the department’s enforcement efforts. Figure 5 shows DRE Investigations Unit workload by type of case from 2004–05 through 2007–08. As the figure shows, rap cases represented 55 percent to 60 percent of the total investigations workload. Consumer complaints represented 37 percent to 42 percent of total workload. With the downturn in the real estate market over the last couple of years, the number of applicants has already dropped significantly. As a result, we would anticipate that the department will soon begin to experience a decline in the number of rap cases.

Figure 5

Investigations Unit Workload |

Number of Cases by Type |

|

2004‑05 |

2005‑06 |

2006‑07 |

2007‑08 |

Consumer complaints |

3,148 |

3,297 |

4,113 |

4,509 |

Rap investigations |

4,309 |

5,246 |

6,539 |

5,889 |

Petitions for reinstatement |

275 |

222 |

440 |

322 |

Totals |

7,732 |

8,765 |

11,092 |

10,720 |

|

|

|

|

|

Complaints as share of total |

41% |

38% |

37% |

42% |

Raps as share of total |

56% |

60% |

59% |

55% |

The workload generated from investigations varies by the type of case. In general, consumer complaint investigations take longer than the other types of investigations as they often involve follow–up interviews with the complainant(s), interviews with various witnesses, as well as reviews of related mortgage documents. Moreover, depending on the nature of the complaint and the initial findings of the investigation, complaints may also lead to audits of licensee records. In contrast, rap investigations mostly involve reviewing court–certified documents and other paperwork submitted by the applicants to determine if the crime is substantially related to the business of real estate.

Based on the average number of investigation hours reported by DRE for each case type, Figure 6 shows our rough estimate of the way DRE’s investigative staff has been allocated among the different types of cases. Overall, we estimate that rap cases and consumer complaints demanded roughly equal portions of the department’s investigative resources. In two of the four years reported, rap investigations required more staff resources than the other types of cases.

Figure 6

How Resources Are Allocated for DRE Investigations |

Estimated Positions by Caseload Type |

|

2004‑05 |

2005‑06 |

2006‑07 |

2007‑08 |

Consumer complaints |

20 |

20 |

25 |

28 |

Rap investigations |

18 |

22 |

28 |

25 |

Petition for reinstatement |

3 |

3 |

5 |

4 |

Totals |

41 |

46 |

59 |

57 |

|

Detail may not total due to rounding. |

What Drives Rap Caseload? The relatively high number of rap cases partly reflects growth in the number of applicants and licensees during the recent real estate boom. The department has little control over such trends. However, the size of the rap caseload also partly reflects the lack of specificity in state law as to the minimum license qualifications for honesty and integrity. For example, rather than outright prohibiting individuals who have been convicted of a felony from obtaining a license, state law grants the Commissioner discretion to deny an applicant based on a conviction for a felony or other crime substantially related to real estate. As a result, the Commissioner has to make judgments on a broad range on crimes, and must determine how the crimes relate to the practice of the real estate business. This has led to an overly complex and cumbersome process that requires significant resources and which diverts resources that could be used to conduct additional or more in–depth investigations of consumer complaints.

Disciplinary Actions Rare, and Few Involve Real Estate Transactions

Based on the findings of an investigation, the Commissioner may seek to revoke or suspend a license, issue a restricted license, or publicly reprimand (or “reprove”) a licensee. In addition, when notified of pending disciplinary actions, some licensees voluntarily surrender their license. Figure 7 shows the frequency of these types of outcomes of investigations.

Figure 7

Frequency of Disciplinary Actions |

Number of Cases |

|

2003‑04 |

2004‑05 |

2005‑06 |

2006‑07 |

2007‑08 |

License revoked |

139 |

236 |

227 |

247 |

376 |

License suspended |

120 |

110 |

102 |

113 |

136 |

License restricted |

165 |

250 |

168 |

147 |

122 |

Voluntary surrenders |

73 |

60 |

38 |

46 |

72 |

Public reprovals |

3 |

6 |

23 |

10 |

4 |

Totals |

500 |

662 |

558 |

563 |

710 |

As share of licensees |

0.13% |

0.15% |

0.11% |

0.10% |

0.13% |

Roughly 0.1 Percent of Licensees Affected by Disciplinary Action. As the figure shows, the number of disciplinary actions has varied somewhat from year to year. In 2007–08, there were 710 disciplinary actions, somewhat more than in previous years. The two most common disciplinary actions were license revocations and license suspensions. Overall, disciplinary action is very rare. For instance, as shown in Figure 7, disciplinary actions affected about only 0.1 percent of existing licensees.

Most Disciplinary Actions Not Result of Real Estate Transactions. Given that the department’s mission is to protect consumers engaged in real estate transactions, one might expect the department to focus more of its enforcement efforts on these types of transactions to resolve complaints as well as deter misconduct by licensees. However, this is not the case. As we discussed above, most of DRE’s investigations do not involve such crimes, but rather focus on other types of crimes not directly related to any real estate transaction. The available data on DRE disciplinary actions reflect this fact.

Figure 8 summarizes DRE disciplinary actions by type of violation for a recent one–year period—from March 2007 to February 2008. As the figure shows, of all the disciplinary actions brought by DRE during that period, 379, or 59 percent, involved a licensee who was arrested and convicted (mostly by local authorities) of one or more crimes. Thus, the majority of disciplinary actions are not the result of consumer complaints, or crimes directly related to real estate transactions, but instead involve various other crimes (such as resisting arrest, driving under the influence of alcohol, spousal abuse, theft, burglary, and assault with a deadly weapon).

Figure 8

Disciplinary Actions by Type of Violation |

March 2007 Through February 2008 |

|

License

Revocation |

License

Restriction |

Suspension |

Suspension With Stay |

Totals |

Criminal convictiona |

278 |

101 |

— |

— |

379 |

Real estate transaction violationsb |

86 |

52 |

5 |

116 |

259 |

Totals |

364 |

153 |

5 |

116 |

638 |

|

a Disciplinary actions based on raps. |

b Based on consumer complaints. |

The data also indicate that licensees with such a local criminal conviction were more than twice as likely to have their license revoked than licensees disciplined for other reasons. While 73 percent of licensees with a criminal conviction had their license revoked, only 33 percent of licensees disciplined for other reasons were subject to license revocations. Based on these statistics, it appears licensees are more likely to lose their license for a charge of driving under the influence of alcohol, for example, than for misrepresentation in a real estate transaction.

While we would acknowledge that disciplinary actions against licensees for these types of crimes do in fact provide some protection to consumers, consumers might be better served if the department focused more of its enforcement efforts on crimes or violations committed as part of a real estate transaction.

Many Real Estate–Related Disciplinary Actions Are for Technical Violations. Our review suggests that many of the disciplinary actions taken because of real estate transactions are based on “technical violations,” rather than defrauding or making substantial misrepresentations to consumers. Some examples of technical violations include failure to comply with trust fund accounting regulations or failure to post a license at the office. These types of violations are typically identified as part of a DRE audit, and frequently have no identifiable victim. The actual number of such technical violations is unknown because of the manner in which the department collects and reports data on disciplinary actions. However, our review of available data on DRE audits and disciplinary actions suggests that technical violations potentially account for 30 percent to 40 percent of real estate–related disciplinary actions.

Complaints by Department on Decline

According to the department, some of its investigations are based on news stories or other informal sources of information. In these cases, the DRE is considered the complainant. These proactive investigations are intended to increase the department’s presence in the field, and in so doing, provide an added incentive for licensees to comply with the Real Estate Law. Figure 9 compares the number of complaints filed by DRE and consumers during two successive four–year periods to examine the long–term trend. As the figure shows, the number of complaints filed by DRE against real estate licensees dropped from 27 percent of all complaints to 16 percent of complaints in the most recent period. Overall, the data suggest that the department’s proactive efforts have declined while the number of consumer complaints have increased in total and as a proportion of those filed.

Figure 9

DRE Filing Fewer Complaints Against Licensees |

Complaints by Type |

|

1999‑00 to 2002‑03 |

2003‑04 to 2006‑07 |

DRE complainant |

2,387 |

26.9% |

1,331 |

15.8% |

Public complainant |

6,474 |

73.1 |

7,094 |

84.2 |

Totals |

8,861 |

100.0% |

8,425 |

100.0% |

Lengthy Disciplinary Process Limits Consumer Protection

Average Case Processing Time Exceeds One Year. When a consumer complaint is filed, the department conducts a complaint investigation. Depending on its findings, the investigation could lead to an audit, further evidence–gathering, a review by the department’s legal section, and, finally, an administrative hearing on charges against a licensee. Most complaints do not go through the entire process, as many drop out after the initial investigation—typically for lack of evidence. However, DRE estimates the average processing time to be about 420 days (or 14 months) for a complete case to go from complaint investigation through an administrative hearing. The department’s goal is to complete the disciplinary process within a year. As of January 31, 2009, about 27 percent of cases (or 1,860 cases) were more than a year old.

Why Does the Processing Time Exceed One Year? The type and complexity of complaints, and the experience and skill of DRE investigators, have a significant impact in determining the length of time needed to resolve these DRE cases. Our review shows that two other major factors also play a role. These are:

- High Standard of Proof Set for DRE Disciplinary Actions.

State law requires the Commissioner to follow certain procedures to take a formal disciplinary action against a licensee, including filing an accusation against the licensee and having a formal hearing before an administrative law judge pursuant to a state law known as the Administrative Procedures Act. The administrative hearing process is designed to protect the rights of the individuals involved. In cases involving disciplinary action against a licensee, DRE has the burden of proof, and is required to prove by clear and convincing evidence to a reasonable certainty that there was a violation of the Real Estate Law. This legal standard of proof is the highest evidentiary standard in a civil court. According to DRE staff, this high standard of proof in administrative hearings partly explains why investigations take a long time, as well as why some complaints are dismissed due to lack of sufficient evidence. In the text box below, we discuss in more detail current practice related to the standard of proof in administrative hearings.

Competing Priorities. As we discussed earlier, the department’s enforcement workload is comprised mostly of consumer complaints and rap cases. The length of time to process consumer complaints is determined in part by the allocation of staff resources between these two activities. Conceivably, the department could process more complaints if more resources were aimed at those types of investigations as opposed to rap investigations. As we noted earlier, only about one–half of the department’s investigative staff resources are spent handling consumer complaints investigations. Since consumer complaints involve actual real estate transactions, this means that only one–half of the department’s enforcement activities are geared toward monitoring individuals who are actually licensed and currently engaged in real estate transactions.

Is “Clear and Convincing Evidence” the Appropriate Standard of Proof for Real Estate Agents? Standards of Proof in Administrative Hearings Differ. The state Office of Administrative Hearings (OAH) conducts administrative hearings on charges filed against various types of licensees, including doctors, lawyers, and real estate salespersons and brokers. The OAH applies two differing standards of proof in such hearings to determine whether to revoke or suspend a license: (1) the preponderance of the evidence, which is analogous to “the majority” of the evidence, and (2) the much higher standard of clear and convincing evidence to a reasonable certainty. In general, the lower standard—preponderance of the evidence—applies to state occupational licenses that do not have education and training requirements, while the higher standard applies to licenses that do require education and training. According to OAH, since statute—with few exceptions—does not provide guidance as to which standard to apply for the different licensed occupations, its approach is based on case law (particularly, Ettinger v. Medical Board of California). The courts have ruled that the standard of clear and convincing evidence is the appropriate standard for licenses that require extensive education and training (such as doctors or lawyers). The court rationale for this higher standard is that it is appropriate based on (1) the “quasi–criminal” nature of the proceeding and (2) the “vested interest rights” of the license holder. Consumers Disadvantaged. Our analysis found some problems with the way that this standard of proof is being applied by OAH to real estate licensees as well as certain other types of professions licensed by the state. For example, the OAH process does not account for the fact that education requirements for different types of occupational licenses vary significantly. The real estate salesperson license, which requires only nine units of prelicensure education, is now getting the same standard of legal protection in disciplinary hearings as the physician’s license, which requires far more formal education and training at a much greater expense to the licensee. According to DRE, the difficult challenges posed by application of the clear and convincing proof standard partly explain why many consumer complaints are dismissed for lack of sufficient evidence, and why investigations of consumer complaints take 14 months on average to close. What Can the Legislature Do? The Legislature has expressly provided that licenses for certain businesses may be revoked or suspended using a preponderance of evidence standard of proof. For example, under state law, licenses to provide child care, substance abuse treatment, and health care may be suspended or revoked based on the preponderance of the evidence standard. As regards licenses that have education requirements, the Legislature may want to evaluate each license and determine based on the level of required education (and the amount of time and expense required to attain such education) which standard of proof should apply. |

Consumer Complaints Understated

Cases Not Always Reported to DRE. Our review indicates DRE consumer complaint data understate the level of real estate consumer complaints and consumer dissatisfaction. Many local law enforcement agencies—namely district attorneys, sheriffs, and police departments—take consumer complaints on real estate transactions, but some do not routinely report these cases to DRE. Consequently, the extent to which complaints are understated is unknown, but could potentially be significant.

In addition, our analysis suggests that the data about these cases are also understated because some consumers probably choose not to file a complaint for a host of reasons, including most notably the fact that consumers often have little to gain by filing a complaint. Even if DRE finds evidence of fraud and revokes the agent’s license, it does not have the authority to order the licensee to pay damages, refund the consumer, or cancel a contract. Another potential factor that could be suppressing real estate–related complaints is a lack of awareness of consumers of their rights and what they should expect of their real estate agent.

No Effort to Identify Trends. The department’s database of consumer complaints could be a useful tool in monitoring emerging trends in the real estate business, as well as identifying the need to shift priorities and resources between and within programs in order to provide effective consumer protection. Our review and discussions with the department suggest, however, that the department does not use its complaint data to identify trends or to guide how the department could most effectively direct its resources. This probably explains why little or no effort is made by DRE to identify real estate complaints filed locally.

Consumer Education Materials Not Consumer–Friendly

In addition to its licensing and enforcement activities, the department also publishes educational material for licensees and consumers. The materials cover a range of topics, and are available in the department’s field offices, as well as on its Internet Web site. In reviewing the department’s educational materials, we noted a couple of areas of concern.

Some Materials Hard to Read. We found most of the publications cumbersome to read. In particular, most DRE publications are not user–friendly or consumer–oriented. Specifically, they lack concise explanations of often–technical real estate industry terms or charts that make it easy for consumers to find specific information.

Key Information Missing. Our review showed that DRE’s consumer materials mostly focus on specialized topics, such as living in common–interest developments (condominiums), purchasing a mobile home, and reverse mortgages. While we think such information is useful to consumers, we noted an absence of consumer–oriented materials that focus more generally on the consumer’s rights in the process of purchasing a home or other real estate, and the fiduciary responsibility of the real estate agent in that process.

We also found that the department’s Web site does not provide certain key information about the Recovery Account. For example, the department does not provide specifics as to the types of expenses that are reimbursed by the account, or how a consumer may obtain the legal services required to obtain a monetary judgment. Many other states provide this and other key information in a “frequently asked questions” display on their Web site. Without such basic information, some real estate consumers may lack the understanding necessary to help protect themselves against fraud or misrepresentation. Moreover, the department’s enforcement efforts are limited to some extent since many consumers potentially are not informed about when there may be a basis for filing a complaint with DRE.

Access to Recovery Account Limited

As we noted earlier, the Recovery Account provides a source of funds to pay damages to consumers who become victims of fraud by a real estate licensee. Under state law, the Commissioner is required to deposit 12 percent of license fee revenues into the account for payment of claims. Beginning January 2009, the maximum allowable payment is $50,000 for a single real estate transaction, and a total of $250,000 per licensee.

Historically, Few Claims Filed. In recent years, the number of claims filed has been relatively low compared to prior years. For example, during the past five years (2003–04 to 2007–08), the department received an average of about 50 claims per year, as compared to an average of 80 claims per year for the preceding five–year period (1998–99 to 2002–03). During the past 12 years, the highest number of claims filed in a single year was 165, and the highest number of claims paid in a single year was 106. The dollar value of these claims is also very small on a statewide basis—less than $300,000 a year.

Inaccessible to Many Consumers. Several factors explain why so few claims are filed or paid from the Recovery Account. In order to seek payment from the fund, a consumer must have obtained a civil judgment or criminal restitution order against a real estate licensee, and tried unsuccessfully to satisfy the judgment. Our discussions with attorneys who handle real estate cases suggest that such a lawsuit could easily cost tens of thousands of dollars. This sum of money most likely puts litigation—and thus the Recovery Account—out of reach for many Californians, particularly individuals who may have recently purchased a home or other piece of property.

Legislation Raises Award Limits. The maximum award of $20,000 per transaction is low compared to both the cost of bringing a lawsuit and the value of property in California. This may also explain in part the small number of Recovery Account claims. Chapter 279, Statutes of 2008 (AB 2454, Emmerson), increases the maximum claim payment for any one transaction from $20,000 to $50,000 for claims filed after January 1, 2009. It also increases from $100,000 to $250,000 the maximum amount paid on behalf of any licensee. For aggrieved consumers who can afford to bring a lawsuit in civil court, the higher claim limits may provide a greater incentive to seek payment from the Recovery Account.

Fund Balance Was Excessive. The laws governing the account establish a minimum and maximum level of funds that should be in the account at any given time. The minimum amount is $200,000, and the maximum amount is $3.5 million. If the Recovery Account balance is less than $200,000 at the end of the year, the license fee automatically increases by $7 for the broker license and by $4 for the salesperson license, with the additional revenues generated accruing to the account. If, at the end of the fiscal year, the account balance exceeds $3.5 million, the excess amount is credited to the Real Estate Fund. The law also provides the Commissioner some flexibility to transfer funds into and out of the Recovery Account, depending on the resources needed to pay victim claims.

Our review of the department’s financial data suggests that the department has not managed the Recovery Account in a fashion consistent with the requirements of state law. Specifically, at the end of 2007–08, the department reported that the Recovery Account had a fund balance of $15 million—an amount far in excess of the current $3.5 million statutory maximum. While the Commissioner has the authority to transfer into the account “any amounts as are deemed necessary,” the low level of victim claims in recent years (less than $300,000 annually) would not have substantiated such a transfer.

Notably, shortly after we asked the department about this discrepancy between the statutory requirements for the Recovery Account balance, and its reported fund balance, the excess funds were transferred to the department’s main operating fund.

Defrauders Allowed to Walk Away From Debt to Recovery Account. Under the Recovery Program, the agent loses his/her license until the Recovery Account is repaid for any payments made to victims on their behalf. The data suggest that many real estate licensees do not make these repayments. Our discussions with the department suggest that it makes little, if any, effort to collect this money. For example, the department could not provide information on the total repayments due to the fund. Its approach has been not to require defrauders to repay unless and until these individuals want to restore their license privileges. The flaw in this approach, in our view, is that it effectively reduces the level of personal responsibility that licensees bear for their actions, and is therefore counterproductive to the laws designed to protect consumers and deter fraud by licensees.

In addition, to the extent that these individuals do not repay the account, it potentially creates some pressure to raise license fees to maintain the solvency of the account. For example, under current law, if the Recovery Account fund balance falls below $200,000, license fees are automatically increased. In effect, under these circumstances, real estate licensees who abide by the Real Estate Law bear an additional financial burden caused by those who have defrauded real estate consumers.

Recommendations to Improve Oversight, Enforcement, and Consumer Protection

As discussed in this report, we have identified a number of shortcomings in the licensing and enforcement efforts by the department. We believe there are actions that can be taken to address these shortcomings and improve the overall level of consumer protection in the real estate market. To this end, we offer below a set of recommendations designed to tighten existing educational requirements for real estate licensees, increase licensee accountability for violations of the Real Estate Law, and improve department accountability for program outcomes. We further recommend that the department update and expand consumer education materials to help increase consumer awareness of their rights and the obligations of real estate licensees.

Education Requirements Could Be Tightened

Require Report on Education Requirements. We recommend that the Legislature examine the potential benefits and costs of increasing the current educational requirements to obtain the real estate salesperson and broker licenses. As we discussed, our review suggests that current state law requires licensees to have only a rudimentary understanding of the profession despite the fact that real estate encompasses some complex activities, such as real estate finance and mortgage loan brokerage services.

We think the education requirements of the SAFE Act partially address our concerns, particularly those related to mortgage brokers. In addition, however, we recommend that the department be directed to commission a study to evaluate the adequacy of the state’s current education requirements, and to report its findings to the Legislature. We recommend that the study evaluate the potential benefits and trade–offs of such an action. On the one hand, increasing the educational requirement could potentially increase the competency of real estate professionals. On the other hand, such a change could make it more difficult for some individuals to enter the real estate profession, reducing competition and consumer choice in the selection of licensed salespersons and brokers. The funding now available in the Education and Research Account should be sufficient to pay for such a study.

Require Continuing Education to be Completed Annually. As discussed, under current law licensees are allowed to complete the continuing education requirements any time within the four–year license period, which allows them to delay participation in such coursework for several years. Because real estate and related state and federal laws are constantly changing, this potentially places the consumer at greater risk of selecting a real estate professional who is not aware of current real estate practices or legal requirements. We recommend that the Legislature amend the law to require licensees to annually complete a certain share of their continuing education credits. This would be similar to the requirements for real estate licensees in other states, as well as for loan originators subject to the new federal SAFE Act. Requiring each licensee to complete courses in such a manner would promote continuous training, and thus provide a greater assurance that agents in fact remain up to date on real estate business practices and state laws designed to protect consumers.

Require Providers to Submit Information on Licensees Who Complete Courses. We found that California’s Department of Insurance, as well as licensing agencies in several other states, require continuing education providers to submit to the licensing authority the names and license numbers of individuals who successfully complete their course offerings. In Texas, for example, course providers submit the information electronically, and the system automatically updates licensee records to reflect the completion of continuing education requirements. We think adopting a similar approach at DRE would be a significant improvement over the department’s current system, since the process would be less vulnerable to abuse. As such, it would provide a higher degree of consumer protection than the current continuing education verification process. For these reasons, we recommend that the Legislature enact legislation requiring the providers of real estate continuing education courses to submit the names and license numbers of individuals who successfully complete their course offerings. We believe the cost of establishing such as system would be minor.

Strengthen Enforcement of Real Estate Law

Reduce Commissioner’s Burden of Proof in Administrative Hearings. As discussed above, the DRE faces a high burden of proof in administrative hearings to revoke or suspend a real estate agent’s license—one requiring proof by clear and convincing evidence to a reasonable certainty. This standard seems to be out of line with other types of state licensees with limited educational requirements. According to the department, this partly explains why many consumer complaints are dismissed for lack of sufficient evidence, as well as why few complaints result in disciplinary actions against licensees. We think that the deterrent effect of the department’s enforcement activities is probably diminished by the low rate of disciplinary action for violations of the Real Estate Law.

Our discussions with DRE staff and administrative law judges indicate that reducing the burden of proof from “clear and convincing” to “a preponderance of the evidence” would make it easier for the department to hold more licensees accountable for violations of the law, and thus provide licensees more of an incentive to comply with the law. This may also reduce the average time required to take disciplinary actions against dishonest or incompetent licensees.

Authorize Additional Sanctions. We recommend that the Legislature adopt legislation to broaden the Commissioner’s authority to enforce additional types of sanctions and penalties (such as fines) for lack of compliance with the real estate laws. The Legislature should also require the Commissioner to develop a schedule of these alternative sanctions designed to deter unwanted behavior and to provide a swift disciplinary response to violations of the law.

Establish Minimum Standard for Criminal Convictions. State law requires license applicants to provide fingerprints for purposes of a background check, and grants the Commissioner broad discretion to approve or deny applications based on a review of past criminal convictions. This has resulted in a significant number of rap investigations, particularly during periods of high real estate market activity when applications increase. This diverts resources away from monitoring licensees, and investigating consumer complaints, which has resulted in extended processing times for consumer complaints. We recommend the adoption of legislation to establish a more definitive standard for criminal convictions than exists under current law.

Rather than grant the Commissioner broad discretion as it relates to prior criminal convictions, we recommend that state law instead explicitly prohibit individuals with one of certain specified felony criminal convictions (or with any felony conviction within the five–year period preceding the date of application for licensing) from obtaining the license. This would likely reduce the number of rap investigations and free up DRE staff resources to monitor existing licensees and investigate consumer complaints. The level of reduced rap investigations and freed up resources would depend on the extent to which the Legislature chose to make offenders with specified criminal convictions explicitly ineligible for a real estate license.

Require Report on Implementation of SAFE Act. The SAFE Act was enacted in response to the subprime mortgage crisis. The measure aims to strengthen consumer protections in the real estate lending market by creating a single Internet–based licensing system that would be used by all states to license individuals as loan originators. We think the federal law provides an opportunity to improve state oversight of loan origination. At the time this report was prepared, however, DRE and the Department of Corporations had not released their plans to comply with the new federal law. We recommend that the Legislature require these departments to report to the fiscal and policy committees of the Legislature on options to comply with the federal SAFE Act.

Increase Department Accountability

Require Report on Program Performance Measures. We recommend that the department be required to report to the policy and fiscal committees of the Legislature on key performance indicators, including information on program inputs, outputs, and overall outcomes. For program inputs, we recommend the department at a minimum report on the number of cases it received by types (raps, petitions, consumer complaints, and Recovery Account claims) and the personnel resources devoted to these different types of cases. For program outputs, we recommend the department report at a minimum on the number of cases closed by type, the average time it took to process these different types of cases (including any cases that took more than one year to resolve), the number and types of disciplinary actions it has taken (with an accounting separately for the technical violations), and payouts made to consumers from the Recovery Account. As regards broader program outcomes, we recommend that DRE track and periodically report on consumer and licensee satisfaction with the services provided by the department (such as the way complaints are handled, and the helpfulness of its Web site), as well as consumer satisfaction with his/her agent.

Finally, we recommend the department be required to provide a written assessment of the trends its observes from these data and regarding how it has adjusted its enforcement activities to protect real estate consumers. For example, the department should report on actions it has taken to realign its caseload so that its workload is focused to the maximum extent feasible on potential violations of the Real Estate Law, rather than on criminal convictions for other types of crimes.

Update Consumer Education Materials

Develop Plan to Expand and Update Material. As discussed above, the DRE’s consumer education materials are lacking because they do not answer some of the fundamental questions of many real estate consumers and often are not user–friendly. We have concluded that improving and expanding the subjects covered in consumer education materials would improve consumer protection, as well as strengthen the enforcement program. Consumers would gain a better understanding of what to expect from real estate agents, and would be better able to determine if the real estate licensee is providing quality service. We therefore recommend the Legislature require the Commissioner to develop a plan to expand and update the department’s consumer education materials to make them more user–friendly and accessible, and better inform real estate consumers about (1) the process of purchasing a home or other property, (2) their rights and options as consumers, (3) the legal obligations of a real estate licensee toward consumers, (4) the process for filing a complaint with the DRE, and (5) the types of expenses that are reimbursable from the Recovery Account.

Expand Access and Oversight of Recovery Account

Eliminate Requirement of Civil Judgment or Restitution Order. As we discussed, access to the Recovery Account has been limited. Our review suggests that this is partly explained by excessive litigation costs associated with obtaining a civil judgment or restitution order against a real estate agent. Those costs make the Recovery Account inaccessible to many consumers.

We recommend that the Legislature consider expanding access to the account by eliminating the requirement that consumers obtain a restitution order, particularly for cases in which a DRE investigation has determined that the agent or broker has committed an act of fraud or other significant misrepresentation that resulted in consumer damages. This would expand consumer access to the Recovery Account, as well as potentially increase licensee accountability for their actions (since license privileges are suspended until the account is repaid).

Establish Recovery Account as Separate Stand–Alone Fund. Under current law, the Recovery Account is essentially a subaccount of the Real Estate Fund. The Commissioner is authorized to transfer funds between these accounts without any notification to the Legislature or the administration, making it a challenge for either branch to exercise oversight of department expenditures. Moreover, as discussed above, we found that in recent years the department has not closely tracked Recovery Account balances nor observed the statutory rules governing the account. In light of these issues, we recommend that the Legislature adopt legislation to establish the Recovery Account as a separate special fund, and require the department to notify the Legislature of any transfers between the funds. We further recommend that the Legislature adopt budget bill language directing the Department of Finance to include a fund condition statement for the newly created fund in the documents published by the administration each January displaying the Governor’s initial budget proposal for DRE. This would greatly improve legislative oversight of department expenditures and allow the Legislature to better track expenditures for recovery payments to victims of fraud.

Conclusion

The DRE’s primary mission is to protect consumers in real estate transactions. It seeks to accomplish this mission mainly through its licensing and enforcement activities. However, we have identified several shortcomings in the department’s programs that reduce the overall level of consumer protection. Our recommendations to address these concerns are summarized in Figure 10.

Figure 10

Summary of LAO Recommendations for Improving

Real Estate Consumer Protection |

|

Tighten Education Requirements |

Require study on upgrading education requirements. |

Require continuing education to be completed annually. |

Require continuing education course providers to electronically submit student information. |

Strengthen Enforcement of Real Estate Law |

Reduce Commissioner’s burden of proof in administrative hearings. |

Expand sanctions available to Commissioner. |

Establish minimum standards for criminal convictions. |

Require report on SAFE Act implementation. |

Increase Department Accountability |

Require report on program measures. |

Update Consumer Education Materials |

Develop plan to expand and update materials. |

Expand Access to and Oversight of Recovery Account |

Eliminate requirement for civil judgment or restitution order in certain cases. |

Establish Recovery Account as stand-alone fund. |

|

Acknowledgments This report was prepared by

Greg Jolivette and reviewed by

Dana Curry . The Legislative Analyst's Office (LAO) is a nonpartisan

office which provides fiscal and policy information and advice to the Legislature.

|

LAO Publications To request publications call (916) 445-4656. This report and others, as well as

an

E-mail subscription service, are

available on the LAO's Internet site at www.lao.ca.gov. The LAO is located at 925

L Street, Suite 1000, Sacramento, CA 95814.

|

Return to LAO Home Page