General Fund expenditures are forecast to decline from $91.8 billion in 2008–09 to $89.3 billion in 2009–10—a decline of 2.7 percent. This is much less than the budgeted 7.6 percent decrease in expenditures that was expected in July—due principally to our projection that several major departments and programs, such as Medi–Cal and the prison system, are unable to achieve budgeted reductions and that there will be an increase in the Proposition 98 funding guarantee. General Fund expenditures in 2009–10 are billions of dollars below their normal levels due to one–time or temporary actions, including (1) the use of about $10 billion of federal stimulus funds, (2) over $3.6 billion of local government funds benefiting the state under the provisions of Proposition 1A (2004) and a fund shift related to redevelopment agencies, (3) over $1 billion from state employee furloughs that end on June 30, 2010, and (4) over $900 million from delaying the June 30, 2010 state payroll by one day.

In the sections that follow, we provide a more detailed discussion of the expenditure outlook for individual major program areas.

State spending for K–14 education—K–12 education and the California Community Colleges—is governed largely by Proposition 98, passed by the voters in 1988. Proposition 98 obligations are funded from the state General Fund and local property taxes and account for about two–thirds of total support for K–14 education.

Figure 2

Proposition 98 Forecast

(Dollars in Millions)

|

|

2009–10

|

2010–11

|

2011–12

|

2012–13

|

2013–14

|

2014–15

|

|

Minimum Guarantee

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

General Fund

|

$35,977

|

$36,706

|

$34,907

|

$38,725

|

$41,801

|

$44,410

|

|

Local property tax

|

15,406

|

14,343

|

14,150

|

14,335

|

14,702

|

15,260

|

|

Totals

|

$51,383a

|

$51,049

|

$49,057

|

$53,060

|

$56,502

|

$59,670

|

|

Percent change

|

—

|

–0.7%

|

–3.9%

|

8.2%

|

6.5%

|

5.6%

|

|

Proposition 98 "Test"

|

2

|

2

|

3

|

2

|

2

|

2

|

|

Maintenance factor created/paid (+/–)

|

–$2,108

|

–$823

|

$2,622

|

–$2,467

|

–$1,135

|

–$679

|

|

Underlying Forecast Factors (Percent Growth)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

K–12 average daily attendance

|

–0.27%

|

0.05%

|

0.24%

|

0.41%

|

0.48%

|

0.38%

|

|

CCC full–time equivalent students

|

1.40

|

0.90

|

0.80

|

0.60

|

0.60

|

0.50

|

|

Per capita personal income (Test 2)

|

0.62

|

–2.30

|

0.99

|

2.71

|

3.85

|

4.01

|

|

Per capita General Fund (Test 3)

|

6.03

|

0.10

|

–4.47

|

8.63

|

6.56

|

5.62

|

|

Funding Relative to Baseline Costs

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Year–to–year change

|

—

|

$630.2b

|

–$1,991.6

|

$4,002.9

|

$3,387.4

|

$3,064.1

|

|

K–14 COLA—Percent

|

—

|

–0.35%

|

1.62%

|

1.67%

|

1.92%

|

2.28%

|

|

K–14 COLA—Cost

|

—

|

–$178.3

|

$841.0

|

$817.2

|

$1,013.7

|

$1,274.0

|

|

K–14 attendance

|

—

|

116.9

|

181.3

|

234.5

|

280.3

|

264.8

|

|

Difference

|

—

|

$691.6

|

–$3,013.9

|

$2,951.3

|

$2,093.5

|

$1,525.3

|

Current–Year Minimum Guarantee On the Rise

Increase in Current–Year Funding Requirement of $1 Billion. One of the major drivers of the Proposition 98 forecast is General Fund revenues. While the enacted 2009–10 Budget Act reflected fairly accurate final 2008–09 tax revenues, Proposition 98 calculations used May estimates that did not capture a large fall off of revenues in the year‘s closing months. Consequently, actual General Fund tax proceeds will be about $2 billion lower than the figures used for the 2008–09 Proposition 98 calculations. In addition, our estimates of tax proceeds in 2009–10 are $400 million lower than budget estimates. Although these changes reflect a further deterioration of state revenues, they actually increase the Proposition 98 minimum requirement in 2009–10. This is because the Proposition 98 calculation is determined in part by the year–to–year change in state revenues. The larger drop in revenues in 2008–09 compared to 2009–10 results in a higher rate of revenue growth. This higher growth rate, in turn, results in a $1 billion increase in the Proposition 98 minimum guarantee.

Three Options for Addressing Increase in 2009–10 Minimum Guarantee. Considering the volatility and unpredictability of the state’s revenues, the Legislature likely will want to wait until revised revenue estimates are released next May before taking further 2009–10 action. Assuming that our forecast holds, the Legislature has various options for addressing the increase in the 2009–10 minimum guarantee.

- Pay Now. The state could provide the additional $1 billion at the end of 2009–10 in a lump sum. Given the state’s huge budgetary shortfall, however, even greater reductions would have to be made to other state programs to free up the resources to provide the additional funds to K–14 education.

- Create Settle–Up, Pay Later. Rather than paying this fiscal year, the Legislature instead could recognize a “settle–up” obligation and create an out–year payment plan (for example, paying $200 million annually over five years, beginning as early as 2010–11). Creating a settle–up obligation would provide a near–term budget solution to the state (as it would allow the state to postpone the $1 billion payment) but no long–term benefit (as it would not reduce the base for calculating the 2010–11 Proposition 98 requirement and would necessitate out–year settle–up payments).

- Suspend Guarantee. Alternatively, the Legislature could suspend the Proposition 98 minimum guarantee and maintain the existing funding level. This would achieve $1 billion in 2009–10 budget solution and, because a suspension reduces the base for calculating the 2010–11 minimum guarantee, an additional $4 billion in cumulative solutions over the forecast period. It would, however, result in a future maintenance factor obligation of $1 billion. (The extra $1 billion obligation likely would not need to be paid during the forecast period.) This option would not reduce the amount of funding schools expected to receive based on the enacted 2009–10 budget.

Next Two Years Suggest Additional Reductions

Minimum Guarantee Projected to Decrease in 2010–11 and 2011–12. Assuming the state fully funds the Proposition 98 minimum guarantee in 2009–10, we project a small decrease in the funding requirement in 2010–11, with a larger drop in 2011–12. The 2011–12 drop is largely a result of projected declines in state revenues due to the phase–out of the temporary tax increases adopted as part of the February 2009 budget agreement. Prior reductions to education spending in 2008–09 and 2009–10 were tempered by the flow of $6 billion in federal funding from the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA), which helped prevent additional reductions to school district budgets. Thus, if the state funds at the minimum level in 2010–11 and 2011–12 and does not “backfill” these ARRA funds, K–12 school districts and community colleges would face even more difficulty as they also are experiencing decreases in federal funding.

Growth Once the Economy Rebounds

Strong Growth for 2012–13 Through 2014–15. For the remaining three years in the forecast period, we project significant increases in the Proposition 98 minimum guarantee due to stronger General Fund revenue growth. By 2013–14, the minimum funding requirement would return to pre–recession levels. As the bottom part of Figure 2 shows, during the latter three years of the forecast period, the year–to–year increases in the Proposition 98 funding level would be more than sufficient to fund annual COLAs.

Higher Education

(View a brief video summary of our forecast for Higher Education.)

In addition to community colleges (which are discussed above as part of the Proposition 98 forecast), the state’s public higher education entities include the University of California (UC), the California State University (CSU), and the California Student Aid Commission (CSAC).

UC and CSU Expenditures

Our forecast assumes the universities’ operating costs will be roughly even at about $5.3 billion over the course of the forecast period. This amount is substantially higher than state spending in 2009–10, which takes advantage of one–time federal stimulus funds that offset state costs. We discuss the stimulus funds in more detail below.

Link Between State Funding and Enrollment Has Been Disrupted. In previous years, the state budget specified a level of student enrollment for UC and CSU that the Legislature expected would be accommodated with budgeted resources. For the past two years, however, the state budget has not specified university enrollment levels, instead giving the universities flexibility to adjust their enrollment to match available resources. Both university systems have indicated that they plan to reduce their enrollment for the next few years (see nearby box). Moreover, we project that underlying college–age population growth will slow to about zero by the end of the forecast period. For these reasons, we do not project any state augmentations for enrollment growth during the forecast period.

Universities Plan Enrollment Reductions

Both the University of California (UC) and the California State University (CSU) are reducing enrollment in response to budget constraints. Each system has already reduced fall 2009 freshman admissions, and CSU is eliminating spring 2010 admissions—primarily affecting community college transfer students. The UC has expressed its intent to maintain freshman admissions at their current level and increase transfer admissions for 2010–11, but these plans will no doubt evolve as the fiscal year takes shape. The CSU plans significant reductions in the tens of thousands for 2010–11 freshman and transfer admissions. In addition to employing traditional enrollment management tools, one CSU campus has announced that it will no longer provide a local admission guarantee to qualified applicants from its region. |

Fees Projected to Continue Rising. A significant portion of core operating costs at the universities is covered by student fees. The state has no expressed policy for annual adjustments to these fees, which are set by the universities’ governing boards. For 2009–10, UC raised student fees by 9.3 percent, and at the time this report was prepared the Regents were considering a midyear increase of an additional 15 percent. By comparison, the CSU raised its student fees by 32 percent for 2009–10. Recent actions and statements by the universities suggest that student fees will continue to increase for the next few years. We assume that these fee increases will cover various new costs, such as inflation and expansion of institution–based financial aid programs, that are not covered in our General Fund forecast.

Expanded federal, state, and institutional student aid programs will offset a significant proportion of fee increases, particularly for financially needy students. However, uncertainty about future fee levels, as well as “sticker shock” from higher fees, may discourage some from even applying for admission.

Federal Funds Provided One–Time Budget Solution. The Governor vetoed $255 million from each of the universities’ 2009–10 General Fund support, with the expectation that this funding would be replaced with one–time federal stimulus funding. The 2009–10 budget also included additional one–time reductions of $50 million for each university, linked to the availability of federal stimulus funding. We assume that these two cuts, totaling $305 million for each university, would be restored to the universities’ base General Fund support in 2010–11. We assume that the remainder of the federal stimulus funding received by the universities was used to backfill 2008–09 reductions (and therefore does not need to be restored in 2010–11). We also assume that other base reductions made to the universities are ongoing, rather than one–time.

Key Choices Facing Legislature. Given that state General Fund resources are likely to be severely constrained for the next several years, the Legislature faces key questions with regard to the higher education budget.

- How Much Enrollment Should Be Accommodated? The state’s Master Plan for Higher Education directs UC and CSU to accept all eligible applicants in the top one–eighth and one–third of high school graduates, respectively. The number of applicants depends upon a variety of factors, including the number of high school graduates, the cost of attendance, and alternative options such as employment. As discussed above, it is unclear how much enrollment the state budget currently is expected to fund. It is also unclear how the segments’ enrollment decisions interact with one another. The Legislature may wish to provide direction to the universities in this regard.

- How Much Should Higher Education Cost? As noted above, the universities are likely to be increasing student fees at double–digit annual rates for at least the next several years. Not only does this affect the cost of education for students, it also increases state costs for the Cal Grant financial aid programs. The Legislature may wish to provide direction to the universities with regard to the share of education cost that non–needy students should be expected to pay.

- How Should the Universities Reduce Operating Costs? Recent budget constraints have spurred the universities to consider a variety of cost–savings measures, including some designed to increase efficiency. The Legislature may wish to express expectations with regard to efficiency efforts such as student–faculty ratios, student remediation rates, articulation of course sequences, student assessment and placement, caps on number of course units to be subsidized by the state, use of summer session, and other considerations.

CSAC

Cal Grant Programs. Most of the state’s direct General Fund support for student financial aid is directed through the Cal Grant programs, which provide fee coverage and subsistence grants to eligible students. These costs increase with expanded program participation and fee increases. Based on these factors, we project that Cal Grant costs will increase from $1 billion in 2010–11 to $1.3 billion at the end of the forecast period.

Health

California’s major health programs provide health coverage and additional services for various groups of eligible persons—primarily poor families and children as well as seniors and persons with disabilities. The federal Medicaid program, known as Medi–Cal in California, is the largest state health program both in terms of funding and number of persons served. In addition, the state supports various public health programs, substance abuse treatment, community services and state–operated facilities for the mentally ill and developmentally disabled, and health care insurance for children through the Healthy Families Program (HFP).

Phase–Out of Enhanced Federal Match. One factor that increases state costs for some health care programs over the forecast period is the phase–out of the enhanced federal medical assistance percentage (FMAP) provided under ARRA. Historically, the state and federal government share most Medi–Cal costs on a roughly equal basis. However, ARRA temporarily increased the federal share for California to almost 62 percent for benefit costs beginning in October 2008 and continuing through December 2010. When the enhanced FMAP ends, it will reduce federal funding for programs in the departments of Health Care Services, Developmental Services, Mental Health, and Social Services, among others. Our forecast assumes that the reductions in federal funding will be backfilled with General Fund spending. Notably, this has the effect of increasing the year–over–year percentage growth in General Fund spending for these programs during the phase–out period.

While ARRA is in effect, the state is required to maintain its eligibility levels and procedures that were in place as of July 1, 2008. Our forecast assumes no such changes in eligibility.

We discuss other major federal funding changes that could affect the state’s major health programs in the nearby box.

Two Major Proposals Could Have Broad Impact On Health Programs

Two major proposals currently under consideration could have a major effect on state health program expenditures. First, Congress is debating nationwide health care reform legislation that could significantly overhaul the health care system. Among the issues being considered are a potential expansion of the Medicaid program, changes to reimbursement to providers for services, and mandates that individuals obtain insurance coverage. Second, a Medicaid waiver which restructured the state’s hospital financing system expires on August 31, 2010. The Department of Health Care Services, together with stakeholders is developing a waiver renewal request. Depending on the structure of the new waiver, it could have wide policy and fiscal implications for the state’s Medi–Cal Program. Due to the uncertainty as to whether federal health care reform legislation will be enacted, as well as regarding the final terms of the waiver, we have not incorporated the effects of these proposals into our forecast. |

Medi–Cal

We estimate that General Fund spending for Medi–Cal local assistance in the current year will amount to almost $11.8 billion, or about 8 percent, more than appropriated in the 2009–10 Budget Act. We project that General Fund support will grow to $14 billion in 2010–11, a 19 percent increase from current–year expenditures, and will reach $19.2 billion by the end of the forecast period in 2014–15. The three biggest factors contributing to the projected spending growth are: (1) changes in the FMAP discussed above that result in the need for the state to backfill lost federal funds with General Fund over the next two fiscal years; (2) increases in caseload, utilization of services, and rising costs for those services; and (3) the erosion of some budget savings assumed in the 2009–10 budget plan.

Key Program Cost Drivers. A significant forecast factor is our assumption that the cost per person of Medi–Cal health care services will grow at an average rate of 4.5 percent annually. We also project that the overall Medi–Cal caseload will grow nearly 2 percent annually commensurate with increases in the state population and other underlying trends, but that the aged and disabled caseload will grow faster during the projection period.

Erosion of Assumed Budget Savings. The 2009–10 budget plan assumes $1 billion in General Fund savings from the receipt of additional federal funds and obtaining additional flexibility to reduce program costs. The budget plan also includes an unspecified reduction in Medi–Cal local assistance of $323 million from the General Fund. Our forecast assumes that $500 million in savings from federal flexibility will be achieved due to expected (1) federal approval of amendments to the current hospital waiver program and (2) adjustments that would increase the federal funding the state would receive under a current waiver program for family planning services. However, we assume that none of the $323 million unspecified reduction will be achieved.

Developmental Services

We estimate that General Fund spending for developmental services in 2009–10 will total about $2.5 billion. This is $138 million more than the amount appropriated in the 2009–10 Budget Act in order to backfill Public Transportation Account (PTA) funds with General Fund due to a court decision that PTA funds cannot be used to pay for regional center (RC) transportation costs.

We project that General Fund support will grow to more than $2.8 billion in 2010–11, almost a 13 percent increase from current–year expenditures, and will reach $3.8 billion by the end of the forecast period in 2014–15. This projected growth is largely due to increased caseload, utilization of services, and rising costs for those services, as well as the phase–out of the enhanced FMAP rate provided under ARRA. Our forecast assumes that RC caseloads will grow at an average annual rate of 4.2 percent, and that costs overall will grow at an average annual rate of 7.6 percent.

HFP

We estimate that $323 million from the General Fund will be spent for support of HFP in 2009–10. An additional $81 million provided by the California Children and Families Commission brings total state support for the program in 2009–10 to $405 million. (We assume these are one–time monies only.) We estimate that General Fund spending for HFP will grow to $431 million in 2010–11 and reach $543 million by the end of our forecast period in 2014–15. Chapter 157, Statutes of 2009 (AB 1422, Bass), raises $97 million in revenues from an assessment on managed care plans. While these revenues are deposited in the General Fund, they are intended to offset HFP costs.

Enrollment Rebound Expected. In 2009–10, HFP initially faced a significant shortfall due to reductions in state funding, and the program was closed to new enrollment for two months. Funding was largely restored by September 2009, but the program closure resulted in a steep decline in enrollment. We project that enrollment will largely rebound throughout 2009–10, and caseload will continue to grow throughout the forecast period.

Other Cost–Drivers. Our forecast assumes increased costs for provision of health care due to general growth in medical costs, but does not account for potential further increases in costs associated with implementation of the U.S. CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2009 (CHIPRA). Although the act contains several provisions which may increase state costs, such as requirements for new and enhanced services, there is considerable uncertainty at this time regarding what specific actions will be required of the state in order to comply with CHIPRA.

Social Services

California’s major social services programs provide a variety of benefits to its citizens. These include income maintenance for the aged, blind, or disabled; cash assistance and welfare–to–work services for low–income families with children; protecting children from abuse and neglect; providing home–care workers who assist the aged and disabled in remaining in their own homes; and subsidized child care for families with incomes under 75 percent of the state median. Although state departments oversee the management of these programs, the actual delivery of many services at the local level is carried out by county welfare and child support departments. Most social services programs are supported by a mix of state, federal, and county funds. (In the box below, we also discuss the rising General Fund costs of the federal–state unemployment insurance program.)

California’s Other Budget Deficit: Unemployment Insurance

The Unemployment Insurance (UI) program is a federal–state program that provides weekly UI payments to eligible workers who lost their jobs through no fault of their own. The UI program is financed by unemployment tax contributions paid by employers for each covered worker.

Insolvency. As we discussed in our 2009–10 Budget Analysis Series: General Government, the UI fund is currently insolvent. In its most recent fund forecast, the Employment Development Department (EDD) projects that the fund will experience a year–end deficit of $7.4 billion in the 2009 calendar year, rising to $18.4 billion in 2010 and $27.2 billion in 2011.

Federal Loans. Because of the insolvency, EDD obtains federal loans on a quarterly basis to cover projected fund deficits. To date, the state has borrowed about $4 billion, permitting California to make benefit payments to UI claimants without interruption. Federal loans lasting more than one year generally will accumulate interest charges of about 5 percent per year on the outstanding balance.

Temporary Federal Relief. The federal economic stimulus package enacted earlier this year, the U.S. American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, relieves states from making interest payments for UI loans through December 31, 2010. The EDD estimates that the waived interest costs are about $120 million for 2009 and $560 million for 2010. After December 2010, the state must resume making interest payments. The EDD also estimates that the interest amount due in September 2011, for nine months of interest accruing from January 2011 through September 2011, is about $730 million.

Addressing the Insolvency. To restore solvency, the state must increase employer taxes, reduce benefits, or do some combination of the two. The Governor introduced a proposal in November 2008 to restore solvency to the UI fund largely through tax increases and very modest benefit reduction. In addition, two bills were introduced earlier this year to address the insolvency. However, no such legislation has been enacted so far in 2009.

Budget Forecast. Absent corrective action, the UI fund will remain insolvent for the foreseeable future, and interest costs will continue to grow significantly—to about $1.5 billion by the final year of our forecast, 2014–15. Under federal law, these interest charges may not be paid from the UI fund. Our forecast assumes that these interest payments become a General Fund cost beginning in 2011–12. |

Overall Spending Trends in Social Services. Based on current law requirements, we project that General Fund spending will increase from a revised $8.8 billion in 2009–10 to $11.8 billion in 2014–15, an increase of $3 billion. About $1 billion of this increase is attributable to backfilling federal funds from ARRA with support from the General Fund. Most of the remaining $2 billion increase is attributable to caseload growth in CalWORKs, In–Home Supportive Services (IHSS), and SSI/SSP.

Costs of Providing COLAs. If the Legislature elected annually to provide the discretionary California Necessities Index COLAs for social services benefits, total General Fund costs in 2014–15 would increase by about $600 million. This approach would provide an additional $367 million to CalWORKs, $166 million to SSI/SSP, and $67 million to Foster Care. Similarly, if the Legislature elected to provide the counties, which administer most of these programs, with annual inflationary adjustments, total General Fund costs in 2014–15 would increase by about $375 million. The cumulative costs of these COLAs are relatively low compared to prior years because we anticipate that inflation will remain modest during the forecast period.

CalWORKs

Overall Spending Trends. From an estimated 2009–10 spending level of $2 billion, we project that General Fund support for CalWORKs will increase by over $600 million in each of the next two fiscal years. Spending is expected to increase modestly for two more years and then decline in the final year of the forecast, 2014–15, to a total of $3.5 billion. The $1.5 billion spending increase over the forecast period is largely attributable to three factors: (1) backfilling federal ARRA funds, (2) caseload growth, and (3) the fixed federal Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) block grant, which does not adjust for caseload increases. The Legislature made substantial short– and long–term policy changes, as discussed below. Their fiscal effects are reflected in the forecast.

Backfill for Loss of Federal Funds. Because federal support for CalWORKs from the TANF Emergency Contingency Fund (ECF) ends in September 2010, the forecast assumes a backfill of about $430 million from the General Fund in 2009–10, increasing to about $580 million in 2011–12. (The ARRA authorized the ECF, which provides 80 percent funding for increases in grant costs.)

Caseload Costs Affected Mainly by Economic Conditions. The forecast reflects some significant assumptions about how the CalWORKs caseload and the state’s economy will change during the next five years. During 2008–09, the caseload increased by about 8 percent and was forecasted to increase by 14 percent in 2009–10 as the state suffered a severe recession. More recent monthly trends suggest that the caseload growth rate may have peaked as of December 2008. For this reason, we forecast a caseload increase of about 10 percent during 2009–10, with a gradual decline in the growth rate in the subsequent years as the state’s economy improves, followed by an outright decline in caseload in 2014–15.

State, Rather Than Federal Government, Bears Caseload Costs. Although General Fund support for CalWORKs is only $2 billion in 2009–10, total program costs, including federal funds, are approximately $6 billion. Once the ARRA funding expires in September 2010, each 1 percent increase in caseload results in state costs of about $60 million per year, because the TANF block grant is fixed.

Short–Term Policy Changes. For 2009–10 and 2010–11, the Legislature (1) exempted families with very young children or families with two or more preschool children from work participation requirements and (2) reduced associated county block grants for employment services and child care by $375 million. Our forecast reflects complete restoration of these reductions in 2011–12 and provides some “ramp–up” funds during 2010–11 for these activities.

Long–Term Changes. Commencing in 2011–12, the Legislature created a system of (1) shortened time limits for most families on aid, (2) increased sanctions, and (3) new county service obligations for families affected by these new policies. The net impact of these changes is very hard to estimate, but our forecast assumes net savings of about $200 million annually beginning in 2011–12.

SSI/SSP

State expenditures for SSI/SSP are estimated to amount to nearly $3 billion in 2009–10. We project that General Fund support for SSI/SSP will increase by about $85 million each year, reaching $3.4 billion in 2014–15.

Caseload Driven Heavily by Aging Population. The spending increases that we project in SSI/SSP are primarily due to expected caseload growth ranging from 1.9 percent to 2.3 percent annually. In our forecast, the primary driver of the caseload increase is the anticipated growth of the aged population.

IHSS

For 2009–10, we estimate that General Fund spending for IHSS will be about $1.5 billion, roughly $300 million above the appropriation. We project that General Fund support for IHSS will increase to $1.6 billion in 2010–11 and to over $2.3 billion in 2014–15.

Backfill for Loss of Federal Funds. The projected increase in General Fund support for IHSS is due in large part to the expiration of the ARRA relief funds (discussed above in the “Health” section of this chapter). Specifically, as ARRA relief ends in December 2010, the forecast assumes a General Fund backfill of $183 million in 2010–11, increasing to $366 million in 2011–12.

Court Cases Reducing Estimated Savings. Budget legislation for 2009–10 reduced state participation in provider wages and restricted eligibility and program services. However, a federal judge has blocked the implementation of these measures. As a result, we assume no savings from these budget reduction measures in the current year. We assume the state addresses the issues raised in the litigation and is able to achieve these savings beginning in 2010–11. However, we assume that these policies will be implemented beginning in fall 2010 and result in about $200 million in General Fund savings in 2010–11, growing to about $240 million as of 2011–12.

Antifraud Savings Likely Lower Than Assumed. Budget legislation included several antifraud activities that were estimated to result in General Fund savings of $162 million (about 10 percent of program costs) in 2009–10. Based on our knowledge of the program and the implementation to date of these changes, our forecast assumes that about 25 percent, or about $40 million, of the savings are achievable in the budget year.

Judiciary and Criminal Justice

The major state judiciary and criminal justice programs include support for two departments in the executive branch—the CDCR and the Department of Justice—as well as expenditures for the state court system.

CDCR

(View a brief video summary of our forecast for Corrections)

Our forecast assumes that General Fund spending for the support of CDCR operations will increase from $8.9 billion in 2009–10 to $10.8 billion in 2014–15. The projection reflects actions taken to reduce correctional spending in the 2009–10 budget and additional costs to staff and operate new prison facilities that are expected to be constructed during the forecast period.

As discussed below, we estimate that state spending on corrections will be about $1.4 billion higher than the budgeted amount for 2009–10, primarily due to the erosion of planned savings and increased expenditures for inmate medical care.

Full Budget Savings Not Achievable. The 2009–10 budget assumed about $1.2 billion in savings in CDCR’s budget from various policy actions to reduce the inmate and parole populations (such as by increasing the credits that inmates can earn to reduce their stay in prison), as well as from other administrative and programmatic changes. Our forecast assumes that slightly less than half of the $1.2 billion in savings will be realized in the current year. This is primarily due to implementation delays and the absence of a complete plan to achieve the full level of savings. Moreover, our forecast also assumes that a separate $231 million reduction in the 2009–10 budget to the federal Receiver’s medical services operations will not be achieved as planned.

General Fund Offsets Were One–Time Budget Solutions. As part of the 2009–10 budget package, one–time federal stimulus funds were used to offset $358 million in General Fund costs for state prisons. Similarly, funding from a local government finance shift will offset $588 million in state prison costs in 2009–10. Our forecast assumes that the General Fund will replace the total of $946 million in one–time offsets from these two funding sources in the budget year and future years.

Ongoing Operating Costs Projected to Increase. In 2008–09, $487 million was provided from the General Fund on a one–time basis for increased contract medical expenditures for inmates, such as for specialty medical care provided outside of prison. Based on the level of contract medical costs in recent years and the absence of a detailed plan to control such costs in future years, we assume that the prior–year level of contract medical spending will be maintained during the forecast period.

Chapter 7, Statutes of 2007 (AB 900, Solorio), authorizes the construction of thousands of additional prison beds. Our projections assume that about 15,800 additional prison beds will be constructed pursuant to AB 900 during the forecast period, resulting in an estimated $800 million in additional General Fund expenditures to staff and operate the new facilities. As the new facilities are built, the Legislature will need to make policy and budgetary decisions regarding the level of programming and staffing to be provided at these facilities, which will determine the actual increase in operational costs.

Impact of Pending Litigation Not Included in Projections. On August 4, 2009, a federal–three judge panel issued a ruling requiring the administration to provide a prison population plan to the court that will reduce the inmate population to 137.5 percent of design capacity—which is roughly 40,000 inmates—within two years. Although the administration submitted an inmate reduction plan on September 18, 2009, the court rejected that plan and on October 21, 2009 ordered that a revised plan be submitted within 21 days. Given that the three–judge panel has not specifically ordered a reduction in the inmate population at this time, and that the administration continues to appeal the panel’s orders in court, our forecast does not reflect the savings that could result from such a massive population reduction. If the inmate population were to be reduced to 137.5 percent of design capacity, we estimate that annual General Fund expenditures could decline by about $600 million in 2014–15 relative to our baseline forecast for CDCR, depending on the specific actions taken to reduce the population. This estimate takes into account the population reduction proposals approved as part of the 2009–10 budget package and the new prison facilities that are expected to be constructed in the forecast period.

Inflationary Adjustments Not Included in Projections. As discussed earlier in this report, our forecast assumes no price adjustments for CDCR operating expenses. If the Legislature were to provide such adjustments each year, we estimate that the department’s operating expenditures would increase by about $490 million annually by the end of the forecast period, relative to our baseline projections.

Judicial Branch

General Fund spending for the support of the judicial branch is projected to remain relatively flat at roughly $2.4 billion from 2010–11 through 2014–15. This amount, however, is substantially higher than the amount the state will spend in 2009–10. As part of the 2009–10 budget package, funding from a local government fund shift will offset about $1.5 billion in General Fund costs for the courts in the current year. Our forecast assumes that the General Fund will replace the $1.5 billion in the budget year and future years.

Inflationary Adjustments Not Included in Projections. As discussed earlier in this report, our forecast assumes no inflationary adjustments to the operating budget of trial courts. If the Legislature were to provide such adjustments, we estimate that operating expenditures for trial courts would increase by roughly $200 million annually by the end of the forecast period, relative to our baseline projections.

Other Programs

Employee Compensation

The 2009–10 Budget Act assumes over $2.5 billion in cost reductions from various actions affecting state employee pay and benefit costs, including state employee furloughs and a one–day delay in the June 30, 2010 state payroll. Almost all of these savings are one–time in nature, including the Governor’s furlough program, which ends June 30, 2010.

Future State Employee Costs to Be Decided by Policymakers. Our forecast assumes virtually no growth in employee costs through 2014–15 (similar to our treatment of COLAs and inflation adjustments elsewhere in the forecast). Many factors make it difficult to project future employee compensation costs at this point in time. New labor agreements with state employee bargaining units, however, could increase costs for compensation. An adverse court ruling on the legality of the furlough program or the changes in overtime and holiday policies could result in judgments of hundreds of millions of dollars. On the other hand, action by the Governor and/or the Legislature to (1) extend the furlough program, (2) lay off a significant number of state employees and curtail the services they currently provide, or (3) cut state employee salaries could reduce annual General Fund costs in the hundreds of millions of dollars.

Public Employee Retirement Costs

Our forecast reflects an increase in the state’s annual payments to four major public employee retirement programs: pension programs for state and CSU employees, the teachers’ pension program, state and CSU retiree health benefit programs, and pension programs for judges. (The teachers’ pension program is administered by the California State Teachers’ Retirement System [CalSTRS], and the other three programs are administered by the California Public Employees’ Retirement System [CalPERS].) The state’s required contributions to CalPERS for state and CSU pensions are about $3 billion (all funds) in 2009–10. In our forecast, these payments to CalPERS grow to over $4 billion during the forecast period. The General Fund pays just under 60 percent of these costs. The state’s required payments to CalSTRS are estimated to be $1.2 billion in 2009–10, all of which is paid from the General Fund. We forecast that these payments to CalSTRS grow to $1.7 billion in 2014–15—in part to restore the system’s funding level due to the effects of the large drop in stock and other investment values that affected all pension systems in 2007 and 2008. The state’s retiree health contributions to CalPERS are forecast to grow from $1.3 billion in 2009–10 to $2 billion in 2014–15.

Rate–Setting Method, State Payroll, and Stock Prices Drive CalPERS Costs. Our forecast assumes that CalPERS continues to use its current pension rate–setting methodology. Several years ago, after the value of its investments fell 22 percent between 2000 and 2002, CalPERS chose to spread higher state and local government payments over many more years. Due to the system’s huge investment declines in 2007–08 and 2008–09, the CalPERS board already has decided to delay payments even further for local governments. The board is expected to decide whether to delay payments for the state at its December 2009 meeting. This decision could mitigate our projected payment increases in some years of the forecast. Our forecast, however, assumes no significant increase in state payroll during the forecast period. Since pension contributions are based on a percentage of payroll, salary increases for state employees would increase pension contributions above our forecast. The forecast also assumes that CalPERS meets its annual investment return target of about 8 percent each year.

Unfunded Liabilities Will Persist. The state’s retirement programs are expected to have significant unfunded liabilities of over $100 billion combined for much or all of the period through 2014–15. Based on current law, the state will be making payments on these unfunded liabilities each year in our forecast. The lingering unfunded liabilities will contribute to rising costs over the long term as well.

No Additional State Payments for UC Retirement Programs Assumed. Consistent with past funding practices, our forecast assumes no additional state contributions between 2009–10 and 2014–15 to cover costs of UC’s pension and retiree health programs. Both have unfunded liabilities, and currently, no significant contributions are being paid by UC or its employees to the pension program. Unless UC identifies non–state funding sources for these programs soon, their costs will escalate significantly over the long term.

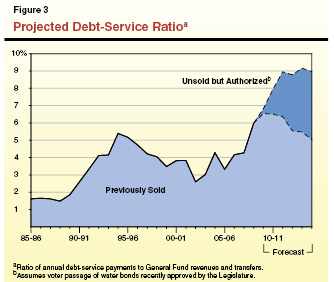

Debt Service on Infrastructure Bonds

The General Fund incurs debt–service costs for both principal payments and interest owed on two types of bonds used to fund infrastructure—voter–approved general obligation bonds and lease–revenue bonds approved by the Legislature. We estimate that General Fund costs for debt service on infrastructure bonds will be $6 billion in 2009–10 and $7 billion in 2010–11. The relatively high pace of debt–service growth in the forecast period—projected to be 8.4 percent annually between 2010–11 and 2014–15—is due in part to the increase in bond sales from the large general obligation bond authorizations in 2006 and 2008, as well as the start of issuance of AB 900 lease–revenue bonds for the prison system. Our forecast assumes the planned sale schedule of bonds that have already been authorized, including the recently approved water bonds (which still require voter approval).

Debt–Service Ratio (DSR) Expected to Rise. The DSR for infrastructure debt—that is, the ratio of annual General Fund debt–service costs to annual General Fund revenues and transfers—is often used as one indicator of the state’s debt burden. There is no one “right” level for the DSR. The higher it is and more rapidly it rises, however, the more closely bond raters, financial analysts, and investors tend to look at the state’s debt practices, and the more debt–service expenses limit the use of revenues for other programs. Figure 3 shows what California’s DSR has been in the recent past and our DSR projections for the forecast period.

The DSR we are projecting—over 9 percent at its peak—is considerably higher than it has been in the past. In part, this reflects the sharp, recent fall–off in General Fund revenues, which drives up the ratio for a given level of debt service. To the extent additional bonds are authorized and sold in future years beyond those already approved, the states debt–service costs and DSR would be higher than projected in Figure 3.

|

Acknowledgments

The Legislative Analyst's Office (LAO) is a nonpartisan

office which provides fiscal and policy information and advice to the Legislature.

|

LAO Publications

To request publications call (916) 445-4656. This report and others, as well as

an E-mail subscription service, are

available on the LAO's Internet site at www.lao.ca.gov. The LAO is located at 925

L Street, Suite 1000, Sacramento, CA 95814.

|

Return to LAO Home Page