Over the last five years, in response to severe state budget difficulties, the state has given most employees time off from work in exchange for reduced pay. The time–off policy began as administratively imposed furloughs and was replaced by the collectively bargained “Personal Leave Program” (PLP). Because furloughs and PLP are functionally the same policy, we refer to them as furloughs in this report.

California state workers historically have not used all of the time off they earn in a year. Thus, at the time the furlough policies were adopted, there was concern that state employees might not take off all the additional time provided under furloughs. This, in turn, would result in state workers carrying larger balances of unused vacation time and annual leave—triggering increased state costs when the employees separate from state service.

This report provides an overview of state leave and furlough policies and then examines the effect of the recent furloughs on leave balances. The second part of the report discusses whether large leave balances are a problem for the state and reviews the state’s options for reducing them or containing their growth.

Paid Time Off Is an Important Part of Employee Compensation. Research indicates that employees across the public and private sectors in the United States highly value paid time off and that employees who take time off are happier and more productive. As a result, the state of California and most other employers provide paid time off as part of their compensation packages to recruit and retain employees. The state’s employee compensation package includes salary, pension, health, and leave benefits.

State Offers Relatively Generous Leave Benefits. Based on surveys of other employers in the United States, the state of California appears to offer employees more paid days off each year than the average employer. The state’s relatively generous leave benefits—in addition to its pension and health benefits—likely make the state’s compensation package more competitive in recruiting and retaining staff who otherwise could receive higher salaries working for different employers.

State Employees Receive a Variety of Paid Days Off

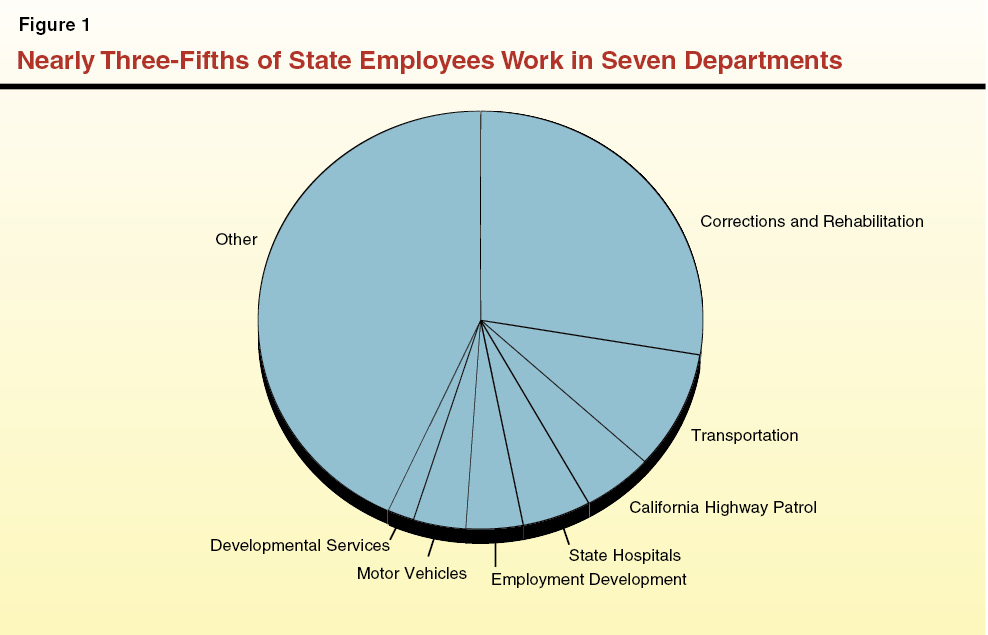

About 215,000 people work for a California state department or agency (excluding the state’s public universities). Figure 1 shows the major departments where these “executive branch” employees work. State workers receive a variety of days off in an ordinary year, including state holidays, professional development days (PDD), and personal holidays. These days off are established in memoranda of understanding (MOUs) or statute. Employees may use PDD and personal holidays for any purpose and at any time during the year, subject to management approval.

Vacation or Annual Leave. In addition to holidays and PDD leave, state employees may choose whether to earn vacation or annual leave. As Figure 2 shows, vacation and annual leave are earned on a monthly basis at rates determined by the employee’s seniority. If an employee chooses to earn vacation leave, he or she accrues 12 days of sick leave each year in addition to vacation. While vacation may be used for any purpose, sick leave may only be used for limited purposes. Employees who earn annual leave, conversely, do not earn sick leave—they use annual leave for vacation and sick days.

Figure 2

Number of Vacation or Annual Leave Days Earned Each Year Increases With Senioritya

|

Years of Service

|

Employee May Choose to Receive:

|

|

Vacationb

|

Annual Leave

|

|

Less than 3

|

10.5

|

16.5

|

|

3 to 10

|

15.0

|

21.0

|

|

10 to 15

|

18.0

|

24.0

|

|

15 to 20

|

19.5

|

25.5

|

|

More than 20

|

21.0

|

27.0

|

Leave Can Be “Banked,” “Cashed Out,” or “Burned Off.” Different rules apply to the different types of leave. As shown in Figure 3, most paid days off—as well as leave days provided under the furlough programs or earned by working on holidays or overtime—may be banked and used in future years. In addition, most leave may be burned off, a term that means that the employee collects a salary and benefits while not working in the period just before he or she separates from state service.

Figure 3

Rules Governing the Major Types of State Employee Leave

|

Leavea

|

Banked?

|

Burn Off?

|

Cash Out?

|

|

Vacation

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

|

Annual Leave

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

|

Holidays

|

No

|

Yes

|

No

|

|

Holiday and Overtime Credit

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

|

Professional Development Days

|

No

|

Yes

|

No

|

|

Sick Leave

|

Yes

|

No

|

No

|

|

Furlough

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

No

|

Finally, as an alternative to burning off leave, employees may cash out leave that is considered “compensable”—primarily, vacation, annual leave, and holiday and overtime credit. When an employee separates from state service, he or she receives a separation payment for any unused compensable leave. Separation payments are calculated by multiplying the number of unused compensable leave hours by the separating employee’s final salary at an hourly rate. Other days—such as furlough days and sick leave—are considered “non–compensable.” When an employee separates from state service, he or she does not receive compensation for unused non–compensable days. (In the case of sick leave, however, an employee retiring from state service can apply unused sick leave towards his or her service credit for purposes of calculating pension benefits.)

Unused Leave Creates Liabilities

Direct Costs, Overtime, and Productivity Losses. Under current law, virtually all unused leave poses some form of liability for employers when an employee separates from employment. Specifically, employers, including the state, incur:

- Costs when the employee cashes out compensable leave.

- Productivity losses when employees burn off leave.

- Additional costs if the employer pays another employee to cover for workers burning off leave. These costs sometimes accrue to employees as overtime wages—in which per–hour costs are higher than for the typical hour worked.

Certain Costs Tracked in Financial Statements. As a result, the state—like most public employers—tracks these liabilities and reports compensable leave balances in its annual financial statements. The state, however, does not set aside funds to pay these costs, but requires departments to pay them on a pay–as–you–go basis as state workers separate from employment.

Departments Leave Positions Vacant or Redirect Funds to Cover Costs. To cover these costs, departments typically leave positions vacant and/or redirect funds from other parts of their budgets. Depending on the amount of unused leave associated with employees separating from state service in any year, this approach can negatively affect a department’s (1) productivity (by causing it to leave many positions vacant or filled with absent staff members) or (2) ability to carry out its obligations within budgeted resources.

Caps on Leave Balances

Many Employers Limit Accumulation of Unused Vacation and Annual Leave Days. To minimize the financial risks associated with large leave balances, many public and private organizations adopt leave policies that limit the number of unused vacation/annual leave days employees may carry over from one year to the next. It is common for these limits to be between 20 days and 40 days of leave, meaning these caps typically prevent vacation/annual leave balance liabilities from exceeding between 8 percent and 15 percent of an employee’s annual salary costs. Many large public employers that we reviewed imposed a cap on the amount of vacation/annual leave employees may carry over. For example, the federal government limits most employee vacation/annual leave balances to 30 days, New York State limits these balances to 40 days, and Texas limits balances to between 23 days (for employees with less than two years of service) and 67 days (for those with more than 35 years of service). Here in California, the city of Los Angeles limits balances to the amount of vacation an employee earns over two years, the county of Los Angeles limits balances to 40 days, and San Francisco limits balances to between 40 days (for those with up to five years of service) and 50 days (for those with more than 15 years of service).

State Policy Caps Vacation and Annual Leave Balances. The state of California caps the amount of vacation/annual leave that most state workers may accumulate at 640 hours (80 days). The two significant exceptions to this rule pertain to the following nonmanagerial groups.

- California Highway Patrol (CHP) Officers. The CHP officers may accumulate up to 816 hours (102 days) of leave.

- Correctional Officers. These officers’ cap was 640 hours, but the cap was eliminated in their most recent MOU.

The state’s leave balance caps—established in regulations, statute, and MOUs—are the state’s main tools to manage state employees’ leave balances. When an employee approaches or exceeds the caps, managers are supposed to work with the employee to develop a plan to ensure that the employee is able to take time off to keep his or her leave balances below the applicable cap.

Many Employers Use Furloughs. When facing fiscal challenges, many employers—in state, federal, local government, and the private sector—have used furloughs as a way of maintaining their workforce while reducing employee compensation costs. Furloughs typically reduce workers’ pay by reducing the amount of time they work.

State Frequently Uses Them. The state of California has used furloughs in 8 of the last 30 fiscal years (1992–93, 1993–94, 2003–04, and 2008–09 through 2012–13), typically reducing state employee pay by about 5 percent and increasing employee allowed time off. The state also realizes other savings from furloughs because the pay cuts indirectly reduce its costs for employee benefits that are determined as a percentage of employee pay, such as contributions to Medicare, Social Security, and pensions. California, however, typically has chosen to apply its furlough policies in a manner that does not affect employees’ pension and other benefits—or the amount of vacation and other leave that employees earn.

Recently, State Has Imposed Five Years of Furloughs. The state began its recent series of furloughs in February 2009. The current furlough program is scheduled to end July 2013. Between February 2009 and July 2013, there have been only four months during which no state employee was furloughed (July 2010 and April, May, and June 2012). Throughout this five–year period, furloughed state employees received one, two, or three days of furlough each month, generally corresponding with 4.62 percent, 9.24 percent, or 13.86 percent cuts in pay, respectively. Figure 4 shows that as a result of this policy, the state reduced its employee compensation costs by about $5 billion between February 2009 and July 2013. Of this $5 billion, about $2.7 billion of savings accrued to the financially troubled General Fund. Furloughs, however, also were applied to employees supported in whole or part by other funds for administrative reasons and to prevent employee migration from General Fund departments.

Figure 4

Savings From Furloughs and Personal Leave Programs

(In Millions)

|

Fiscal Year

|

General Fund

|

Other Funds

|

Totals

|

|

2008–09

|

$322

|

$268

|

$590

|

|

2009–10

|

1,185

|

982

|

2,167

|

|

2010–11

|

601

|

519

|

1,120

|

|

2011–12

|

183

|

153

|

335

|

|

2012–13

|

373

|

445

|

818

|

|

Totals

|

$2,663

|

$2,367

|

$5,030

|

Furlough Policies Varied Considerably. At various points in time, certain classifications, bargaining units, and departments have been exempt from the furlough policy. As a result, there is significant variation in the number of furlough days employees received. In addition, during this period, furloughs for some employees were “self directed,” meaning that employees could choose when to use their furlough day, subject to management approval. In other cases, furloughs were compulsory on specified days, commonly called “Furlough Fridays.” For details on when each employee group was furloughed and background on how the furlough policy was administered during this period, please refer to the appendix.

To assess the effect of furloughs on state employee leave balances, we reviewed summary data regarding state compensable leave balances over the last few decades, met with selected departments, and examined department level leave balance data between September 30, 2008 (the earliest date for which detailed information was available) and June 30, 2012. Figure 5 summarizes the key findings from our review.

Figure 5

Major Findings

- Furloughs greatly increased employees’ available time off.

|

- State workers used most of their furlough days, but decreased their use of vacation and annual leave days.

|

- The state’s cap on leave balances was not effective.

|

- Leave liabilities and payments to separating employees are now at historic levels.

|

- Some furlough savings create long–term liabilities.

|

Furloughs Greatly Increased Employees’ Allowed Time Off

Most state employees received a significant number of days off in exchange for reduced pay during the recent furlough period. Figure 6 illustrates how many furlough days an employee received if the employee had been subject to the policies for their entire duration. As can be seen from the figure, the number of furlough days given to employees varies significantly by employee group.

Figure 6

Employee Groups Received Different Numbers of Days Off

2008–09 Through 2012–13

|

Employee Groupa

|

Furlough and Personal Leave Program (PLP) Days

|

|

Correctional officers, engineers, attorneys, park rangers, scientists, and stationary engineers

|

94

|

|

Employees represented by SEIU (Local 1000)

|

79

|

|

Managers and supervisors

|

79

|

|

Heavy equipment mechanics, maintenance workers, physicians, psychiatric technicians, and health and social services professionals

|

70

|

|

Firefighters

|

20

|

|

Highway patrol

|

12

|

For Average Worker, Allowed Time Off Increased by 50 Percent During Last Five Years. To put the number of furlough days in Figure 6 into perspective, it is helpful to compare them with the number of paid days off an average state worker receives in the absence of furloughs. Specifically, the average state employee earns 32 paid days off each year—18 vacation days and 14 days for state and personal holidays and PDD. The average worker received 79 furlough days between 2008–09 and 2012–13, averaging 16 days per year. The state’s furlough policy, therefore, increased the average employee’s total amount of available time off by 50 percent. This large increase in time off decreased the amount of time available to complete state work products. It is important to note that, in many cases, this significant increase in available time off and decrease in work time occurred without the state formally adjusting expectations for state department productivity.

State Workers Used Most of Their Furlough Days

Prison Workers, However, Used Less of Theirs. As of June 2012 (the latest data we reviewed), state employees had used about 95 percent of their furlough days and had, on average, three unused furlough days banked. The key exceptions were employees of the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR) and certain small departments. Specifically, while CDCR employees make up less than 30 percent of the state’s workforce, these employees account for nearly two–thirds of the state’s balance of unused furlough days. This is not entirely surprising given that CDCR employees (1) received the greatest number of furlough days, (2) work at 24–hour facilities where giving one employee time off often requires paying another overtime, and (3) had greater flexibility to bank furlough days under self–directed furloughs rather than Furlough Fridays.

Workers in Some Small Departments Used Less. Viewed in terms of balances of unused furlough days per employee, some of the state’s smallest departments reported the largest balances. In fact, employees in two of the state’s smallest departments—the Santa Monica Mountains Conservancy and Commission on State Mandates—reported having about 14 and 9 unused furlough days per employee, respectively. Staff from the commission and other small departments with whom we discussed our findings indicated that the limited number of staff in their departments made it difficult for any employee to take time off for lengthy periods.

Employees Decreased Use of Vacation and Annual Leave

Leave balances grow when employees do not use all of the days off that they earn. Larger leave balances result in higher long–term liabilities for the state. Prior to 2008–09, the average employee’s vacation/annual leave balance grew by about 2 percent annually. During the first four years of furloughs, in contrast, our review indicates that that the average employees’ vacation/annual leave balance grew by about 11 percent annually. This higher level of growth is equivalent to the average employee banking about 4 days of vacation/annual leave each year during the furlough period.

Growth in Balances Caused by Use of Furlough Days First. This growth in vacation/annual leave balances—at the same time that employees used most of their furlough days—stems from employee decisions to use furlough days first, before using vacation/annual leave days. This action is consistent with the administration’s policy that management approve the use of furlough days before other types of leave. We note that employees also have a personal financial incentive to use furlough days before vacation/annual leave. This is because separating employees have the option of burning off or cashing out unused vacation/annual leave—but may only burn off unused furlough days. By using furlough days instead of vacation/annual leave days, employees significantly increased the state’s leave balance liabilities.

Also Reflects Departmental Workload Issues. The decreased use of vacation/annual leave also may reflect the difficulties many departments experienced completing their workload with reduced staffing levels. There is significant evidence, for example, of departments denying or discouraging employee requests to take time off due to workload pressures. In addition, there is evidence of managers authorizing employees to take time off, but then rescinding the authorized use of leave, citing operational needs. Actions by management to deny the use of time off, in turn, appear to have created some tension in the workplace. We note, for example, that many of the 2012 MOU addenda that established the collectively bargained furlough program, the PLP, provide that an employee’s authorized use of PLP days cannot be rescinded more than twice even for operational needs.

State’s Cap on Leave Balances Is Not Effective

Ineffective Leave Cap Not a New Issue. As discussed earlier in this report, the state’s main policy tool to limit state leave balance liabilities is a cap on unused vacation/annual leave. For many years, there has been concern about the effectiveness of the cap on a statewide basis. We note, for example, that in 2005—a year without major budgetary constraints and workforce reductions—there were more than 900 nonmanagerial correctional officers and more than 10,000 other state employees whose vacation/annual leave balances exceeded the cap. During labor negotiations that year, the Schwarzenegger administration characterized these leave balances as “a huge unfunded liability for the State” and proposed actions to strengthen the effectiveness of the cap. These changes, however, were not included in any of the ratified MOUs.

Recently, Cap Seemed Totally Ineffective. During the furlough period, we found no evidence that the cap had an effect on containing state employee leave balances. Instead, the number of nonmanagerial correctional officers over the cap quadrupled to more than 3,700 by March 2011, when the state eliminated the cap for these workers. The number of other employees over the cap also grew quickly from more than 10,000 in 2005 to nearly 24,000 by January 2013.

Department staff with whom we spoke suggested that they took few, if any, steps to counsel employees reaching the cap or to modify workload to allow employees to take more time off. In some cases, supervisorial staff do not appear to receive regular reports of their staff’s leave balances. We also note that there does not appear to be any concerted or consistent effort by state control agencies to enforce the cap.

Leave Liabilities Now at Historic Levels

Vacation/Annual Leave Balances Were High Before Furloughs Started. During the 1980s and early 1990s, the state’s vacation/annual leave balances were about 22 days per employee. Leave balances of this size represent more than 8 percent of the employer’s annual salary cost. As discussed earlier in this report, most other employers limit the maximum vacation/annual leave balance for any single employee to be between 8 percent and 15 percent of salary costs. Thus, it is possible that the state’s average leave balance of 8 percent was somewhat similar to other employers’ liabilities during this period.

Later in the 1990s and early 2000s, however, the average state employee vacation/annual leave balance grew, partly as a result of personnel policy changes—such as extending the annual leave program (which offers a greater number of leave days) to all state employees (instead of limiting it to managers) and the furloughs of the early 1990s and 2003–04.

Shortly before the most recent series of furloughs, the average state worker had 35 days of banked vacation/annual leave. The state’s liability from this unused vacation/annual leave was about $1.9 billion, or about 14 percent of state salary costs.

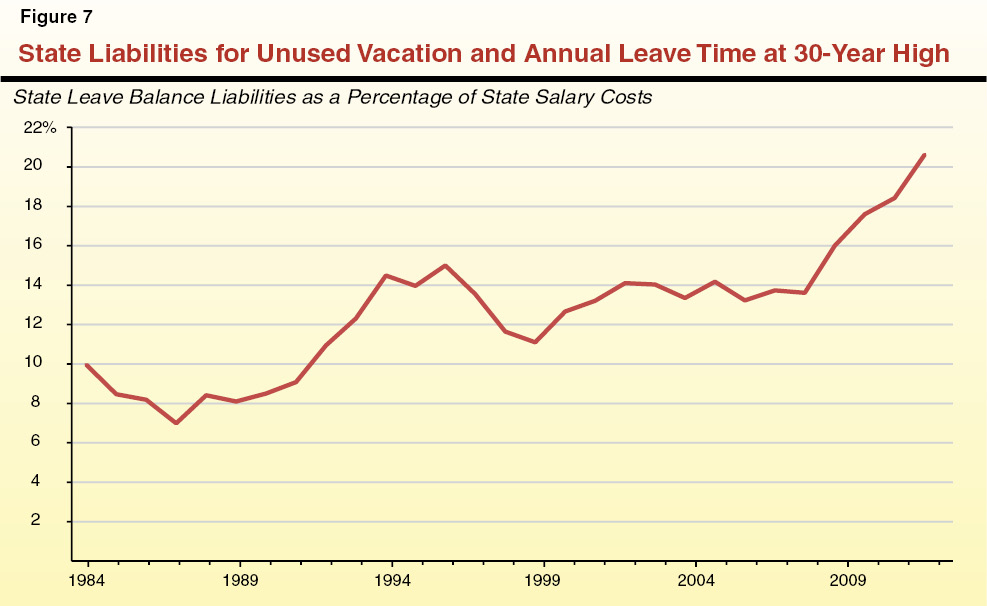

Vacation/Annual Leave Balances Grew Rapidly After Furloughs. After furloughs started, employees began using furlough days instead of vacation/annual leave days. By June 2012, the average state employee’s vacation/annual leave balance grew from 35 days to more than 53 days. The state’s liability from vacation/annual leave in 2012 was about $3 billion. This is equal to more than 20 percent of state employees’ salaries, considerably higher than the maximum range of vacation/annual leave balances allowable by most other employers and, as Figure 7 shows, over twice the level in 1984.

The state’s total compensable leave liabilities, however, actually are higher than those shown in Figure 7. This is because, in addition to vacation/annual leave, the state must reimburse separating employees for unused holiday credit, overtime, and certain other types of compensable leave balances. When all forms of compensable leave are included, the state’s leave balance liability in June 2012 was $3.9 billion (about $2.1 billion of which is attributable to the state’s General Fund). This $3.9 billion amount is about $1 billion higher than the state’s total compensable leave balance before furloughs. (Data limitations prevent us from discussing the changes over the decades in the state’s total compensable leave balances.)

CDCR Accounts for One–Third of Leave Balance Liabilities. Figure 8 shows the distribution of the state’s $3.9 billion liability across departments. As shown in the figure, CDCR employees account for about one–third of these liabilities, but CHP officers have by far the largest number of banked compensable leave days compared with the average employee at other major departments. We provide additional information regarding compensable leave balance liabilities on our website.

Figure 8

Leave Balances by Department as of June 30, 2012

|

Department

|

Banked Compensable Leave Days Per Employee

|

Liability From Compensable Leave (Millions)

|

|

Corrections and Rehabilitation

|

72

|

$1,237.4

|

|

Transportation

|

60

|

385.2

|

|

California Highway Patrol

|

91

|

314.5

|

|

Mental Health

|

51

|

154.8

|

|

Employment Development

|

39

|

89.6

|

|

Developmental Services

|

69

|

89.0

|

|

Justice

|

52

|

70.6

|

|

State Compensation Insurance Fund

|

55

|

69.2

|

|

Motor Vehicles

|

34

|

60.1

|

|

Social Services

|

50

|

50.5

|

|

Board of Equalization

|

42

|

49.5

|

|

Parks and Recreation

|

42

|

46.6

|

|

General Services

|

47

|

40.9

|

|

Industrial Relations

|

51

|

38.6

|

|

Fish and Game

|

53

|

37.7

|

|

All other

|

53

|

1,142.0

|

|

Totals

|

59

|

$3,876.2

|

$3.9 Billion Total Liability Likely to Grow. Going forward, we expect this $3.9 billion liability to grow because (1) most state employees will receive a 3 percent to 5 percent pay increase in July 2013, increasing the cost to cash out their leave balances, (2) most state employees have been furloughed for 12 months following June 2012, (3) employees have some banked furlough and other non–compensable days that they are likely to use in lieu of compensable leave, driving up their compensable leave balances, and (4) state employees historically have not used all of their leave time earned in a year even in the absence of furloughs. For these reasons, we estimate that the state’s compensable leave balance will exceed $4 billion by the start of 2013–14 and continue to grow in the foreseeable future. This growth will be moderated somewhat by a likely increase in the number of state employees retiring.

Payments to Separating Employees Now at Historic Highs

Affected Departments Typically “Absorb” Costs. Under state budget practices, when an employee separates from state service, the department that last employed the individual pays the employee’s full separation payment—regardless of where the employee accrued the leave balance. Departments typically are not budgeted to make these separation payments, but are expected to absorb them within existing resources.

In some cases, because workers have retired with extensive unused leave balances, separation payments have been large—sometimes hundreds of thousands of dollars. These large payments, in turn, have evoked controversy in news reports—particularly in cases when the employee received payments equal to many months of leave accrued in excess of the state leave cap.

Separation Payments at Highest Levels in 30 Years. The amount of money that state departments have paid in separation payments has increased significantly in recent years to the highest levels in 30 years. In 2011–12, state departments paid $270 million in separation payments—two–thirds more than they did during the year before furloughs. This sudden increase in separation payments is due to an increase in retirement rates and the rapid growth in employee compensable leave balances. Some departments have requested budgetary augmentations to cover these costs. As in the case with the state’s overall leave balance, we expect separation payments to remain at high levels for at least the next few years.

Some Furlough Savings Shifted Costs to Future Years

Roughly $1 Billion of Savings Carried Into Future as a Liability. While employers implement furloughs to achieve employee compensation savings, furloughs generally do not yield real savings unless workers actually take the time off. Specifically, if an employer reduces a worker’s pay but the employee works the same amount of time, the employer’s leave balance liability usually grows. The employer then must pay the employee when the worker separates from service. Furlough policies that reduce employees’ pay—without reducing their hours worked—shift compensation costs to future years when the employer must make larger separation payments.

Our analysis indicates that roughly $1 billion—more than $500 million General Fund—of the state’s $5 billion in furlough savings has been carried into future years as a liability from larger leave balances. The state will pay these liabilities when the employees separate from state service. We note the state also may have incurred other costs due to the furlough policy, such as increased overtime expenses or costs to pay growth in the state’s unfunded pension liabilities. These costs are not included in our $1 billion estimate.

About $4,000 Owed to Average Employee. Viewed from the perspective of an average state employee, the five years of furloughs reduced his or her $69,000 annual salary by a total of $21,000. The worker took off most of the furlough days, but banked some vacation days. The value of this increased leave is roughly $4,000 today and will grow, over time, as the employee’s salary increases. If the employee does not use this time in the course of his or her career, the state will pay the employee for this leave when the worker separates from state service.

The state’s liabilities associated with unused leave are large. Based on trends over the last 30 years, these liabilities likely will continue to grow. This, in turn, prompts the question: Should the state take actions to reduce employee leave balances or contain their future growth?

No “Right” Level of Employee Leave Balances. Our review indicates that there is no single right level of employee leave balances. Whether large leave balances pose fiscal or operational stress on a department depends on many factors. We note, for example, that California had relatively high employee leave balances for most of the 1990s and early 2000s. During this time, departments periodically requested midyear appropriations to cover separation payments, but the state’s leave balances did not appear to pose a major fiscal problem. That said, for the reasons discussed below, we think the Legislature should take steps to reduce the state’s leave balances—or at least contain their future growth.

Reduces Budget Transparency

How Departments Absorb Costs Often Not Known. Through the annual budget process, the Legislature appropriates money and authorizes positions for departments to achieve specified legislative priorities. Once the Legislature approves the budget package, however, departments modify their financial and operational plans to reflect the pressures related to separating employees’ leave balances, including making separation payments, holding positions vacant, and allowing staff to be absent. These changes generally are not reported to the Legislature. Thus, it is not possible for the Legislature to determine what priorities are not being fulfilled due to the pressures associated with separating employee leave balances.

Imposes Fiscal and Operational Stress on Some Departments

Can Negatively Affect Departmental Performance. The lack of budgetary transparency also makes it difficult for the Legislature to determine the extent of fiscal and operational stress that these liabilities impose on state departments. In our discussions with departments, we found that some perceive their ability to carry out their responsibilities has been negatively affected by large leave balances. For example, the Fair Political Practices Commission advises us that it kept its executive director position unoccupied for nearly eight months because the former executive director separated from the commission with leave balances approaching 70 percent of his salary. The separating employee burned off about two months of leave before separating from the commission with a separation payment worth over half of his salary. Similarly, CDCR indicates that it made separation payments totaling $300 million between 2009–10 and 2011–12 and projects it will make more than $100 million in separation payments in 2012–13. The CDCR indicates that these costs contributed to its need to seek midyear supplemental appropriations and its delay of special repairs and other essential activities, actions that can increase future CDCR operating costs.

Strains Management–Employee Relations

Hard to Allow Employees to Take All Allowed Leave Days. Through the recent furlough programs, the state reduced employees’ pay with the promise of giving them commensurate time off. In some cases, however, workload considerations caused management to deny state workers’ requests for time off—or led to workers not requesting the time off. In these cases, because workers do not receive the benefit promised by management on a timely basis, furloughs can negatively affect labor relations. Longer term, strained labor relations can impair the state’s productivity and the level of service provided to the public. In addition, the state’s reputation as an employer can be weakened, affecting its ability to recruit and retain desired talent from the labor market.

May Weaken Public Confidence in Management of State Workforce

Large Differences Between State and Other Employers. The public entrusts government to effectively and efficiently manage resources and the workers it hires. In assessing government’s management of its employees, residents and the media typically compare government’s personnel policies with those used in the private sector. When residents and the media find public sector personnel policies that appear to be more generous than those in the private sector, questions often arise as to whether government is spending public resources wisely.

The state’s personnel policies have led to large differences between the benefits offered to state and private sector workers when they separate from their employment. Specifically, compared with private sector employees, many state workers (1) receive larger separation payments and (2) collect salaries and earn benefits (including more leave time) for longer periods while burning off accumulated leave. The magnitude of the benefits provided to state workers is partly due to reasons that are not likely to encourage public confidence in the state’s management of its workforce. Specifically, as administered by the state, the furlough program did not reduce employee work time to levels that would prevent rapid growth in leave balance liabilities. In addition, the state has not enforced its primary policy to contain these future costs—the cap on accumulated vacation/annual leave. Looking forward, having state leave policies that are more similar to other employers—and enforced—may give the public greater confidence that the state is effectively and efficiently managing its resources.

In this section of the report, we discuss options available to the Legislature to reduce existing leave balances and contain their future growth. Most of the options involve difficult decisions and trade–offs—such as those between incurring near– and long–term state costs, and paying for employee leave benefits versus other forms of compensation. In addition, many of the options could have unintended consequences by modifying employee behavior. There is no perfect option. Each option has limitations, and no one option can resolve all of the concerns discussed in the section above. In fact, some of the options could address some of the concerns while worsening others—for example, reduce liabilities but further erode public confidence.

Options Limited Due to Contract Law. The state is limited in what it can do to reduce existing leave balances. Current law establishes that employees have a vested, contractual right to earned compensable leave. This means that once an employee earns compensable time off, the state cannot take it away without due compensation. The state must compensate employees for any compensable leave that is already earned by allowing employees to (1) take the time off or (2) cash out the unused leave. Below, we discuss two options available to the Legislature to reduce existing leave balance liabilities. These options would reduce the state’s long–term liabilities, but would reduce productivity or costs in the short term.

Focus Attention on Departments With Large Leave Balances

There are many approaches the Legislature could take to focus attention on departments with large leave balances. Below, we outline one approach the Legislature could use in the current budget cycle.

Spring 2013: Establish Targets for Reducing Leave Balances . . . Each department has unique circumstances that led to its employees accumulating large leave balances. To better understand why employees have large leave balances and what steps the state could take to reduce these liabilities, legislative budget or oversight committees could hold hearings with representatives from the Human Resources Department (CalHR), Department of Finance, and a representative sample of departments with large employee leave balances. To establish a baseline assessment of all departments and help the committees identify which departments should attend the hearings, the State Controller’s Office could report on the number of employees in each department with leave balances over a threshold amount, such as 640 hours, and the current value of this leave. The purpose of the legislative hearings would be to (1) identify why these departments’ employees have large leave balances and (2) establish reasonable targets for reducing these leave balances by spring 2014 and future years.

. . . But Give Special Consideration to Departments With 24–Hour Operations. In developing these leave reduction targets, we recommend the Legislature be realistic about departments with 24–hour operations. Specifically, unless the state provides more funding for staff at these departments or changes their workload requirements, it is likely that these departments will incur increased overtime costs to give their employees more time off. We also note that, in some cases, paying overtime so that other employees can use leave costs the state more than allowing workers to cash out their leave (either at the end of their career or through an authorized buyback program). The Legislature could use the hearings to explore options specifically oriented towards these departments.

Spring 2014: Assess Departments’ Progress. During the 2014–15 budget cycle and in subsequent years, CalHR could provide the Legislature an assessment of the state’s progress in reducing employee leave liabilities. Additionally, departments could report their individual progress at achieving the targets established by the Legislature.

Institute Buyback Program

Many public and private sector employers offer leave buyback programs to reduce leave balance liabilities. A buyback program gives employees the opportunity to cash out some of their existing compensable leave balances at their current salary level. While a leave buyback program increases employer costs in the short run, it reduces the employer’s outstanding long–term liabilities.

State Has Offered Buybacks in the Past. While the state has offered leave buybacks in the past, CalHR indicates that it has approved only one leave buyback program in the past ten years. Typically, buyback programs are limited to (1) specified employees, (2) a period of time during which eligible employees may cash out leave, and (3) a maximum number of hours that an employee may cash out. The last authorized leave buyback was available primarily to managers and supervisors between April and June 2007. Eligible employees could cash out up to 40 hours of compensable leave. A department, however, could choose to further limit the number of hours employees cashed out if departmental funds were limited. As discussed in press reports, in 2011, the Department of Parks and Recreation instituted a buyback program for which it did not have authorization. The department cashed out about $270,000 of employee leave under this unauthorized program.

Buyback Program Would Increase Short–Term Costs, but Reduce Long–Term Liabilities. The Legislature could direct the administration to authorize a leave buyback program. A buyback program could be administratively established for managers and supervisors, but probably would need to be collectively bargained for rank–and–file employees. Depending on how many employees were eligible to participate in a buyback program and how many hours they could cash out, a buyback program could result in significant up–front costs. For example, a buyback program that cashed out all leave in excess of the existing cap would cost the state about $270 million (or $330 million if nonmanagerial correctional officers were included). To control these costs, the Legislature would need to provide the administration guidance as to the design of the buyback program. The Legislature also would need to make decisions about how to fund it. For example, the Legislature could augment individual departmental budgets to provide funding for the expected costs or establish a separate item in the budget to pay these costs for all departments. Regardless of the funding mechanism, the costs associated with a buyback program would reduce the Legislature’s ability to provide resources to other programs in the state budget. Obviously, because of the up–front cost of a buyback program, such a program would be easiest during years without significant budgetary constraints.

Significant Flexibility for the State. The Legislature has a greater degree of flexibility to implement options that contain future unfunded liabilities from employee leave balances—ranging from changing budgeting practices to changing leave policies. Because employees only have a vested right to earned leave, the Legislature can change leave benefits on a prospective basis. Prospective benefit changes could be administratively imposed on managers and supervisors, but probably would need to be bargained for rank–and–file employees. Because 19 of the state’s 21 MOUs with state workers expire in July 2013, the administration could incorporate mechanisms to contain leave balance growth in labor agreements submitted to the Legislature for ratification. We note, however, that any action that reduces prospective leave benefits likely would put pressure on the state to augment other components of employee compensation—salary, pension, and health benefits.

Create a Use It or Lose It Cap on Leave Accruals

The Legislature could create a strict cap on prospective leave accruals. The cap could give employees the opportunity to use the time off they earn, but minimize the state’s liabilities from compensable leave balances. Such a cap could take many different forms. Most of the other states we looked at have some form of a strict cap on the amount of vacation/annual leave that employees may accumulate. Below, we describe the key elements of a cap that we think would be reasonable.

Establish an Accrual Limit. The limit should allow employees to have flexibility to take time off during the year but also be low enough to minimize the state’s liabilities. Most of the states that we looked at limit the amount of vacation/ annual leave that a state employee could carry year–over–year to about 40 days. This is half of the limit established by the cap that currently applies to most California state employees.

Specify No Vested Right to Leave Above Cap. Employees could continue to accrue a certain amount of time off each month based on vacation/annual leave accrual schedules; however, employees would have no vested right to any time off received in excess of the cap. For example, if the Legislature adopts an 80–day cap, an employee with 80 days of banked leave would still earn his or her normal vacation days, but these days would need to be used before the end of the year. The employee could only carry up to 80 days of leave year over year. For reasons we discussed earlier, we note that it may be difficult for employees at 24–hour facilities to use all of the vacation/annual leave that they accrue in a year. For these employees, the Legislature may wish to set a higher cap or take other actions to contain long–term liabilities, such as establish regular leave buyback programs.

Plan Carefully Before Giving New Furloughs or More Time Off

Inevitably, at some time in the future, the Legislature will consider proposals to furlough employees or give them additional holidays or other paid time off. Our review indicates that any additional time off—paid or not paid—can result in higher employee leave balances and larger state liabilities. Below, we explain some actions that the Legislature could take to minimize the effects of additional days off on future leave balance liabilities.

When Considering Future Furlough Proposals. Furloughs are a common tool used by employers to reduce employee compensation costs. To achieve savings, the employer reduces its workers’ pay but increases their amount of time off. Administering furloughs on specified days by shutting down operations, like Furlough Fridays, helps contain the growth in leave balances because it forces employees to work fewer hours. Some of the state’s largest departments, including CDCR and CHP, have 24–hour operations, however, and cannot shut down. Thus, extending a furlough program to include their workers does not change the amount of staff hours worked and, instead, increases state leave balance liabilities. In these cases, the Legislature has limited options. It can:

- Exempt workers in these departments from the furlough—an action that reduces by more than 60 percent state General Fund savings from the furlough.

- Reduce departmental workload or requirements so that these departments can operate with fewer workers—an action that would be difficult to implement in many cases due to federal, state, and other requirements.

When Considering Proposals for Additional Paid Days Off. In general, giving state employees additional paid days off augments their compensation package without increasing state costs in the short term. If the employees do not use the additional paid days off, however, state leave balance liabilities grow and the state makes higher separation payments in the future. The Legislature could minimize this potential fiscal effect by specifying that employees have no vested right to the new day. That is, it must be used in the same year given and included within a strict cap on leave accruals (discussed above).

Cash Out Leave When Employees Transfer Departments

Under current law, employees may not cash out their leave when transferring from one department to another. Further, when an employee separates from state service, the department of last employment is responsible for paying the employee’s entire separation payment. As a result, if an employee accrues a large leave balance while working at Department A and then works one year at Department B before retiring, Department B must pay the employee’s entire separation payment. This can create significant budgeting problems for Department B. To ensure that state departments realize the fiscal effects of their leave management policies, the Legislature could allow employees to cash out leave amounts above a certain threshold when transferring to a new departmental employer. These early cash outs also would (1) reduce future state liabilities and (2) provide more timely compensation to employees for leave they were not able to use.

Prefund Liabilities

The state does not prefund leave balance liabilities but instead makes separation payments on a pay–as–you–go basis. The Legislature could explore the option of prefunding leave balance liabilities. To prefund these liabilities, the Legislature would put money aside in a trust fund—perhaps in the range of hundreds of millions dollars each year initially—that would be invested. The state’s contributions and any growth in the fund from investments would be used to pay future separation payments. Annual contributions to this fund could be distributed across departments—similar to how the state prefunds employee pension benefit costs. Because liabilities from leave balances are constantly changing—employees receive pay increases, the size of the workforce changes, employees take off varying amounts of time year to year, and so on—the amount that the state contributes on an annual basis would need to be determined through an actuarial valuation that takes into account various assumptions. While prefunding these benefits increases the state’s costs in the short run, it would significantly reduce the state’s costs associated with separation payments in the long run.

Reduce Number of Days Off Available to Employees

The state’s employee compensation package provides employees a generous number of paid days off each year. If the state were to reduce the amount of time off included in the compensation package, employees likely would use a higher share of their compensable leave days in a given year. This would result in lower leave balance liabilities in the future, but, as discussed earlier, likely would increase pressure on the state to increase other forms of employee compensation.

Evaluate Workload and Staffing Levels at Departments With High Leave Balances

Persistently high leave balances may indicate that employees at a department do not take time off due to high workload. After furloughs end in July 2013 and the state workforce normalizes, the legislative budget subcommittees may wish to examine departments with high leave balances to determine whether additional staffing resources or changes in statutory duties may be merited.

Most employers have fiscal liabilities related to vacation and other leave that their employees have earned, but not used. These leave balance liabilities must be paid when an employee retires or separates from employment.

The state of California has carried large leave balance liabilities for decades. The last five years of state employee furloughs, however, have pushed its leave balances to unusually high levels. Our review indicates that that the state’s leave balances directly or indirectly have negative effects on the state, including: imposing fiscal and operational stress on departments, reducing transparency in state budgeting, straining management–employee relations, and weakening public trust in state government. For these reasons, we recommend the Legislature take steps towards reducing the state’s leave balances—or at least containing their future growth. In this report, we describe several options the Legislature could take to help achieve this goal.