Over the last 15 years, enrollment at the California’s public universities and community colleges increased by approximately 320,000 full–time equivalent students, or about 25 percent. As enrollment expands, campuses need to accommodate the space needs of more students, faculty, and staff. Likewise, the growing campus populations put pressure on the infrastructure of surrounding communities.

The California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA) requires each campus to identify measures for reducing the anticipated impacts of their expansion on surrounding communities. In recent years, the responsibility of paying to mitigate these effects has become a contentious issue between communities and campuses. In 2006, the California Supreme Court’s decision in City of Marina v. California State University Board of Trustees clarified that a campus is responsible, when feasible, for mitigating the significant environmental impacts of its expansion, even if the mitigation involves paying local agencies for off–campus infrastructure. As a result of the Marina decision, the higher education segments and other state agencies may need to reconsider how their growth plans affect surrounding communities and whether they have an obligation to provide payments to local agencies for infrastructure improvements.

In the following discussion, we provide an overview of the higher education segments’ environmental review process, discuss the Marina case and its implications, and offer our recommendations to the Legislature on how to address the local impacts of campus expansion.

All three public higher education systems require that their campuses develop land use plans that guide the physical development of the campus as its enrollment grows. Although the segments use different names for their campus plans, their processes for formulating these plans are similar, including final approval by each school’s governing body—the Regents of the University of California (UC), the Board of Trustees for California State University (CSU), and the local board for each California Community College (CCC)

district. The campus plans show existing and anticipated facilities

necessary to accommodate a specified enrollment level. Figures 1 and 2 provide summary information for UC, which refers to its documents as Long Range Development Plans (LRDPs), and for CSU, which refers to them as physical master plans. Each campus plan is an important policy document that outlines a campus’ development, growth, and priorities.

|

|

|

Figure 1

UC Long Range Development Plan Status |

|

Campus |

Approval Date |

Horizon

Year |

Headcount

Enrollment Ceiling |

2006 Fall Headcount |

|

Berkeley |

January 2005 |

2020 |

33,450 |

33,154 |

|

Davis |

November 2003 |

2015 |

30,000 |

28,369 |

|

Irvine |

November 2007 |

2025 |

37,000 |

24,621 |

|

Los Angelesa |

March 2003 |

2010 |

37,630 |

38,218 |

|

Merced |

January 2002 |

2025 |

13,966b |

1,286 |

|

Riverside |

November 2005 |

2015 |

25,000 |

16,826 |

|

San Diego |

September 2004 |

2015 |

29,900 |

25,229 |

|

Santa Barbara |

—c |

— |

25,000 |

21,082 |

|

Santa Cruz |

September 2006d |

2020 |

19,500b |

15,364 |

|

|

|

a All sites,

including the medical center. |

|

b Full-Time

equivalent students. |

|

c Developing

updated plan for Regents' approval in 2008 with 2025 horizon

year. Current plan created in 1990 with 2005 horizon year. |

|

d Plan and

associated Environmental Impact Report currently voided by Santa

Cruz County Superior Court decision. |

|

|

|

|

|

Figure 2

CSU Physical Master Plan Status |

|

Campus |

Most Recent

Approved Revision

To Master Plana |

Master Plan

Enrollment (FTEb) |

2006 FTE

Enrollment |

|

Bakersfield |

2007 |

18,000 |

6,554 |

|

Channel Islands |

2000 |

15,000 |

2,617 |

|

Chico |

2005 |

15,800 |

14,882 |

|

Dominguez Hills |

2005 |

20,000 |

8,435 |

|

East Bay |

2001 |

18,000 |

10,560 |

|

Fresno |

2007 |

25,000 |

18,399 |

|

Fullerton |

2003 |

25,000 |

26,587 |

|

Humboldt |

2004 |

12,000 |

6,797 |

|

Long Beach |

2003 |

25,000 |

27,845 |

|

Los Angeles |

1985 |

25,000 |

15,397 |

|

Maritime Academy |

2002 |

1,100 |

992 |

|

Monterey Bay |

2006c |

8,500 |

3,518 |

|

Northridge |

2006 |

35,000 |

26,029 |

|

Pomona |

2000 |

20,000 |

17,072 |

|

Sacramento |

2004 |

25,000 |

22,537 |

|

San Bernardino |

2004 |

20,000 |

13,226 |

|

San Diego |

2007 |

35,000 |

28,040 |

|

San Francisco |

2007 |

25,000 |

23,573 |

|

San Jose |

2002 |

25,000 |

23,156 |

|

San Luis Obispo |

2001 |

17,500 |

17,217 |

|

San Marcos |

2001 |

25,000 |

6,917 |

|

Sonoma |

2000 |

10,000 |

7,312 |

|

Stanislaus |

2006 |

12,000 |

6,724 |

|

|

|

a Not all

revisions increase enrollment ceiling. For example, CSU

Stanislaus has not increased its

enrollment ceiling in more than 20 years. |

|

b FTE= Full-time

equivalent. |

|

c Environmental

Impact Report (EIR) vacated by the Marina case. Expected

to submit revised EIR to

Board of Trustees in 2008. |

|

|

A previous LAO report entitled A Review of UC’s Long Range Development Planning Process (January 2007), outlined the campus planning process, specifically highlighting planning issues within the UC system. The report found that the UC’s planning process:

- Lacked state accountability and oversight.

- Lacked standardization in public participation.

- Provided minimal systemwide coordination for projecting future enrollments.

- Incurred higher costs and delays due to a lack of clarity in CEQA.

Below, we provide a closer examination of the role that CEQA and the environmental review process play in campus planning for all three segments.

Although campuses are exempt from local land use control in the development of a campus plan, they are subject to CEQA. The CEQA requires that state agencies prepare a comprehensive EIR for any proposed project with potentially significant environmental impacts. There are two types of EIRs depending upon the type of project:

- Program–Level EIR. Since a campus plan includes numerous projects, the accompanying EIR is typically referred to as a program–level EIR. Since the growth in enrollment and facilities outlined in a campus plan occurs in tiers or phases, a program–level EIR considers the cumulative environmental impacts of all the separate projects identified in the campus plan.

- Project–Level EIR. As each project covered by the campus plan begins implementation, CEQA requires that the campus prepare a project–level EIR. However, given the certification of a program–level EIR on the entire campus plan, these project–level EIRs are not required to be as detailed.

The program–level EIR must (1) provide detailed information about the likely effect of the envisioned expansion on the environment (such as traffic), (2) identify measures to mitigate significant environmental effects (such as mitigating traffic impacts by constructing physical improvements like traffic signals or roundabouts), and (3) examine reasonable alternatives to the proposed campus plan. Each campus must first prepare a preliminary EIR for public review and allow at least 30 days for public comment. The campus must then evaluate all comments and prepare written responses to them, which must be included in the final EIR. Under CEQA, UC Regents, CSU Board of Trustees, or the local board of trustees for individual CCC districts act as “the lead agency” which must certify the EIR before approving a campus plan.

As described above, the EIR identifies all of the significant environmental impacts of a campus plan. For each significant impact, the EIR

must either (1) describe one or more specific mitigation measures that could

be implemented to reduce the impact to a less than significant level or (2)

declare that the impact is �significant and unavoidable� (see the following box).

Mitigation of Off–Campus Impacts. A campus plan may identify significant environmental impacts not on the campus’ property, such as increased traffic in local communities or increased stormwater runoff into local waterways. Impacts on local communities can be mitigated in two ways:

- On–Campus Measures. If possible, the EIR can propose on–campus mitigation measures that can be implemented by the campus to reduce these off–campus environmental impacts, such as on–campus housing to reduce commuter traffic or on–campus catch basins to reduce stormwater runoff.

- Off–Campus Measures. In the event that on–campus mitigation measures cannot adequately mitigate the environmental impacts of a proposed campus plan, the EIR must attempt to identify mitigation measures to be performed off campus such as a new traffic signal or enlarged storm drains. Since such mitigation measures are performed on property outside of the campus’ jurisdiction, they must be carried out by the local government agency (city, county, or special district) responsible for improvements to local infrastructure.

Declaring an impact to be significant and unavoidable allows the lead agency to proceed with the project without mitigating that impact. In order to make such a declaration, the lead agency must adopt a Statement of Overriding Considerations which justifies how (1) economic, legal, social, technological, or other considerations render mitigation infeasible (for example, space constraints prevent the widening of a street to reduce traffic); and (2) the benefits of the project outweigh the significant and unavoidable effects on the environment (for example, the benefits to the state of increased college enrollment outweigh the impacts of increased traffic). When the lead agency certifies the EIR, it agrees as part of the implementation of the campus plan to perform all of the identified mitigation measures while the significant and unavoidable impacts may remain unmitigated.

Who Pays for Off–Campus Mitigation Measures? Campuses and their surrounding communities sometimes disagree about the responsibility for mitigation measures occurring outside of the university’s jurisdiction. For example, an EIR may identify a new signal light at a city intersection to mitigate traffic from campus expansion. While the city is responsible for constructing the new signal, it may expect the campus to provide a portion of the funding since the campus’ expansion is contributing to the traffic. However, the city and campus might disagree about how the costs should be shared. Such disagreements have led to numerous lawsuits between campuses and local communities. A recent California Supreme Court ruling on one of these lawsuits—City of Marina v. CSU Board of Trustees—clarified how CSU campuses must consider making payments for off–campus mitigation.

In 1994, CSU committed to establish a Monterey campus on a portion of the former Fort Ord military base as part of the Fort Ord Reuse Authority (FORA) Act. (The state Legislature created FORA—which includes Monterey County and the Cities of Monterey, Salinas, Carmel, Marina, and Pacific Grove—to manage the transition of the base from military to civilian use.) The CSU Board of Trustees in 1998 certified the new campus’ master plan and an accompanying EIR, which identified significant environmental impacts to various off–campus resources. Specifically, the EIR determined that the mitigation of some off–campus impacts—including increased traffic and a greater demand for fire protection services—was within the jurisdiction of FORA and therefore not the responsibility of CSU.

The CSU declared these off–campus impacts to be “significant and unavoidable” by filing a Statement of Overriding Considerations which made two assertions:

- Mitigation of off–campus impacts was legally infeasible because it would require payments to local agencies for infrastructure improvements, which constituted an illegal gift of public funds.

- The benefits of CSU’s educational mission outweighed these specific adverse effects on the environment.

The CSU maintained that funding for improvements to local infrastructure was the responsibility of local agencies such as FORA rather than CSU. Accordingly, CSU proceeded with the proposed developments without providing funding to FORA for mitigation of the off–campus environmental impacts.

In response, FORA and the City of Marina challenged the Trustees’ decision to certify the EIR as a violation of CEQA since it did not mitigate all of the identified impacts. In July 2006, the California Supreme Court reversed an earlier Court of Appeal’s decision by concluding that the Trustees had abused their discretion, and thus their approval of the EIR was not valid. Specifically, the Supreme Court ruled that:

- Off–Campus Impacts Must Be Mitigated When Feasible. The CEQA does not limit the CSU’s mitigation obligation to environmental effects on the university’s own property. Rather, the university is required to mitigate a project’s significant effects not just on its own property, but on the environment as a whole.

- Voluntary Payments Are a Feasible Form of Mitigation. If CSU cannot adequately mitigate off–campus environmental effects with mitigation measures on campus, then it can voluntarily pay a third party (such as FORA) to implement the necessary measures off campus. Such a payment is not a gift of public funds, as CSU had argued, because “while education may be CSU’s core function, to avoid or mitigate the environmental effects of its projects is also one of CSU’s functions.” As a way of meeting its CEQA obligation, the university may voluntarily contribute its proportional share of the cost of improvements to local infrastructure necessitated by a campus’ expansion.

- Lead Agency Has Authority to Determine Fair Share. As the lead agency, CSU has the discretion to determine the appropriate fair–share payment for off–campus infrastructure improvements. Thus, the Marina decision does not require CSU to contribute whatever amount cities, counties, and fire districts deem fitting for mitigation efforts. The CSU retains the responsibility for determining CSU’s share of the cost of implementing an off–campus mitigation measure. As described in the nearby box, the fair–share payment should be based on CSU’s actual impact on the local infrastructure.

The Marina decision prohibits the CSU Trustees, and potentially other governmental agencies, from certifying an EIR that does not provide mitigation for significant off–campus environmental impacts when feasible. Below, we describe how CSU has changed its policy in response to the decision. We also examine how the Marina decision might affect the growth of the other higher education segments and the construction projects of other state agencies.

In response to the Marina decision, the CSU has adopted new language relating to off–campus mitigation in its campus plan EIRs. In EIRs developed for campus plans completed since the Marina decision, CSU agrees to pay its fair share of the costs incurred by a local agency for implementing off–campus mitigation measures, provided that the Legislature appropriates money specifically for this purpose. The CSU uses an upfront approach that attempts to determine the appropriate fair–share payments for off–campus mitigation measures prior to certifying the EIR.

In many instances, a campus’ expansion is not the only contributor to environmental impacts on a locality. For example, nearby shopping malls or housing developments also contribute to increased traffic on local roadways. In such instances, California Environmental Quality Act guidelines state that a campus plan’s mitigation measures “must be roughly proportional to the impacts of the project.” Numerous court decisions, including the Marina decision, routinely refer to these as proportional–share or fair–share payments.

There is no standardized method for determining the proper fair–share payment. The most widely used approach is to determine the proportion of the impact that the campus is responsible for and to provide that proportion of the mitigation measure’s cost. For example, if the campus is responsible for 30 percent of the traffic on a local street, then the campus would contribute 30 percent of the cost of a new traffic signal. Determining a campus’ proportional share of the impacts is a subjective process dependent upon numerous assumptions and measurements. Reaching an agreement on the methodology for calculating the fair share often leads to disputes between a campus and community.

However, a lead agency could consider another method which accounts for the positive impacts the campus has on a surrounding community. Lead agencies have argued that fair–share payments should be less if it can be demonstrated that the project provides other offsetting benefits to the locality. For example, if a campus has open space that is used by local residents, this might provide a benefit that offsets some negative environmental impacts. However, it is unclear how impacts of a differing nature—such as traffic and open space—should be combined.

CSU Negotiates Fair–Share Contribution with Local Agencies. The CSU will enter into negotiations with local agencies to reach a consensus on the campus plan’s environmental impact and CSU’s fair share of mitigation. Under CSU’s process, if the parties reach an agreement, they enter into a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) which stipulates the fair–share amount or the process by which the fair–share amount will be determined. By outlining each party’s responsibilities for off–campus mitigation, the MOU seeks to avoid any future disputes over the amount of fair–share payment. The MOU is also useful because it estimates the mitigation costs the campus will incur as part of implementing the updated campus plan.

What If an Agreement Can’t Be Reached? Failure to reach an MOU with the local agency does not necessarily prevent CSU from proceeding with the project. As mentioned previously, CSU maintains the legal authority to determine the fair–share amount. If CSU and the local government cannot reach agreement on a mitigation payment, the CSU Board of Trustees can adopt the mitigation approach it feels is fair, certify the EIR, and adopt the campus plan.

The CSU’s decision, however, is not necessarily final. The local agency could challenge the EIR by arguing that the adopted mitigation plan does not cover CSU’s actual fair share of the necessary infrastructure improvements. If a court determines that the certified EIR does not provide CSU’s fair–share obligation, approval of the EIR could be vacated for abuse of discretion. The CSU would be required to adopt a new methodology for determining its fair share or abandon the projects causing the significant environmental impacts.

CSU Makes Fair–Share Payments Contingent on State Funding. The CSU’s interpretation of the Marina decision concludes that it is required to request funding for voluntary fair–share mitigation payments from the Legislature. According to EIR language and resolutions passed by the CSU Trustees, if CSU receives full funding for off–campus mitigation from the Legislature, it will provide that funding to local agencies as it proceeds with the proposed projects in its master plans. On the other hand, if CSU does not receive funding or receives only partial mitigation funding, it will continue with the proposed projects, but provide local agencies only whatever was appropriated, if anything, for the implementation of identified off–campus mitigation.

Each of CSU’s recently revised EIRs and MOUs include language that voids fair–share agreements with local agencies if the Legislature does not provide funding specifically for off–campus mitigation. The CSU asserts that without state funding the fair–share payments for off–campus mitigation are infeasible. This, in turn, allows them to reclassify adverse environmental impacts requiring off–campus mitigation as “significant and unavoidable” and therefore proceed with the project.

While the Marina decision directs CSU to request funds from the Legislature before declaring voluntary mitigation payments infeasible, it does not explicitly state that CSU is no longer responsible to mitigate off–campus impacts if the Legislature denies funding. Similarly, CEQA states that “All state agencies, boards, and commissions shall request in their budgets the funds necessary to protect the environment in relation to problems caused by their activities,” without clarifying what happens if such requests are not fully funded.

Mixed Results for CSU’s Fair–Share Language. The CSU Trustees have certified three EIRs containing fair–share language since the Marina decision. At the time this analysis was prepared, these EIRs have resulted in different outcomes:

- The EIR for CSU Bakersfield’s revised master plan included statements that the campus would negotiate its fair share for any necessary improvements to off–campus streets and intersections. The City of Bakersfield and CSU Bakersfield decided to postpone such negotiations until enrollment growth caused the traffic impacts to reach a significant threshold. As described above, the CSU Trustees’ certification of the EIR in September 2007 included a resolution that any fair–share payments would be contingent upon legislative funding.

- San Francisco State University (SFSU) signed an MOU with the City of San Francisco on its fair–share obligation for off–campus mitigation prior to the CSU Trustees’ certification of the campus’ EIR in November 2007. Under the agreement, SFSU agrees to provide $175,000 for intersection improvements and $1.8 million towards a public transit project. If the Legislature appropriates money for this purpose, SFSU will contribute the funds after the city begins implementation of the projects.

- San Diego State University (SDSU) reached an agreement with the City of La Mesa on fair–share payments but failed to reach an agreement in its negotiations with the City of San Diego. La Mesa and SDSU agreed to the cost of $45,686 for two intersection improvements, payable only if legislative action provided the funds. The City of San Diego asserted SDSU’s fair share for traffic improvements was at least $14 million, while SDSU estimated its fair share to be $6.4 million. The city also objected to CSU’s assertion that it was not required to pay for mitigation if the Legislature did not appropriate funding. The SDSU documented its efforts to negotiate with the city, and the CSU Board of Trustees, employing

its discretion as the lead agency, certified the EIR with a $6.4 million voluntary contribution to the city. At the time this analysis was prepared, the City of San Diego and other local agencies were preparing to legally challenge the CSU Trustees’ calculation of its fair–share payment for abuse of discretion.

The Marina decision also sets a precedent for other higher education lead agencies, including UC and CCC districts. Below, we discuss how these two segments approach off–campus mitigation with their host communities.

UC Uses Various Methods of Off–Campus Mitigation. The UC has adopted various formal and informal methods for compensating local communities for impacts on their infrastructure. Some examples include:

- UC Santa Cruz contributed $1.4 million to local agencies from 1991 to 2005 as part of “University Assistance Measures” identified in its 1988 campus plan.

- UC Berkeley, in response to a lawsuit challenging its 2005 LRDP and EIR, reached a settlement agreement with the City of Berkeley in May 2005 in which the campus agreed to provide $1.2 million annually to the city through 2020 for sewer and storm drain infrastructure, fire and emergency equipment, transportation and pedestrian improvements, and neighborhood projects.

- UC Santa Barbara, as part of the mitigation associated with its San Clemente Housing Project, is constructing $5 million in improvements to El Colegio Road as part of an agreement with Santa Barbara County.

- Additionally, UC has incorporated fair–share language for off–campus mitigation into its LRDPs developed since 2002. Unlike CSU, the UC does not attempt to negotiate these agreements prior to certifying the EIR, but waits until impacts reach their trigger points (such as an off–campus intersection reaching a certain level of congestion) before negotiating with local agencies. As a result, UC has not reached any fair–share agreements because the impacts requiring mitigation in LRDPs developed since 2002 (when UC adopted the fair–share language) have not yet reached their trigger points.

The UC’s strategy for compensating local governments for the environmental impacts of campus expansion has not shielded UC from controversy and litigation. As described above, the City of Berkeley’s legal challenge to UC Berkeley’s LRDP resulted in the annual settlement payment for off–campus mitigation, while UC Santa Cruz’s recently approved LRDP for campus expansion has been placed on hold by a Superior Court due to the inadequacy of its EIR in meeting CEQA obligations. Specifically, the court found that UC Santa Cruz’s EIR lacked specificity and an enforceability mechanism for its fair–share payments to the city and did not adequately analyze the significant impacts on water and housing supply.

UC Does Not Receive State Funds Earmarked for Off–Campus Mitigation. Rather than request funds from the Legislature specifically for off–campus mitigation, UC directs funding from within its budget (including nonstate funds) to compensate local agencies for off–campus infrastructure improvements. This means that UC’s EIRs do not contain any language that the funding of fair–share agreements is contingent upon legislative approval. However, since fair–share agreements are not negotiated until a trigger point is reached, many local agencies have expressed skepticism about UC following through when the mitigation becomes necessary.

CCC Process for Off–Campus Mitigation. The CCC Chancellor’s Office (CCCCO) views local college districts as responsible for negotiating with and funding fair–share payments to local governments. If a college’s new campus plan identifies off–campus mitigation measures that require fair–share payments, CCCCO directs the district to use local funds for those payments as the state generally will not provide funding for these costs. The CCCCO does provide districts with state funds for off–site development costs that it considers to be unrelated to CEQA—such as utility connections and improvements to the college’s side of immediately adjacent local streets.

Legal Challenge Implies Greater Costs for Local CCC Districts. The CCC also faced a legal challenge relating to off–campus mitigation payments—County of San Diego v. Grossmont–Cuyamaca Community College District (2006) in the California Court of Appeal. The district argued that its traffic impacts were “significant and unavoidable” because statutory restrictions prohibited it from expending funds on non–educational purposes and making improvements to streets that do not front the campus boundaries. The court found that the applicable provisions of the law did not prohibit improvements on non–adjacent streets and directed the district to comply with CEQA’s mandate to adopt all feasible mitigation measures. As a result of the Grossmont–Cuyamaca decision, the district was required to vacate its original campus plan and EIR and replace them with plans that provided the necessary off–campus mitigation funding. In November 2006, the district settled its dispute with the county by agreeing to contribute $858,000 from district funds to a county fund for road improvements. This contribution covers only the first two projects in the campus plan and payments for subsequent projects will be negotiated as they near construction.

Since the Grossmont–Cuyamaca and Marina decisions require CCC to mitigate all significant impacts, including those requiring off–campus mitigation measures, and CCCCO does not provide state bond funding for most off–site mitigation payments, local CCC districts must continue to rely on local funds (such as local bond proceeds) to cover any off–campus mitigation payments.

All state–funded projects are obligated to meet CEQA’s mitigation requirements, unless they are exempted in statute. Below, we discuss how the Marina decision potentially affects other state–funded projects outside of higher education.

K–12 Facilities. The State Allocation Board (SAB) provides state bond funds for the construction projects of local K–12 school districts. The regulations of the SAB limit off–site mitigation funds to adjacent streets. Specifically, the SAB only allocates state funds for half the cost of improvements on up to two streets immediately adjacent to the site. A reasonable interpretation of the Marina and Grossmont–Guyamaca decisions suggests that all significant impacts, adjacent to the site or not, must be mitigated by a lead agency. In fact, the language in the Education Code that SAB uses to justify providing funding for only two adjacent streets was rejected as a basis for limiting off–campus mitigation payments by the Court of Appeal in the Grossmont–Cuyamaca decision. This means that, absent a change in SAB policy, local school districts will have to provide mitigation payments for nonadjacent improvements solely with local funds (similar to local CCC districts).

Other State Facilities. In the construction of state office buildings and prisons, the state is also obligated to meet CEQA’s mitigation requirements. Even prior to the Marina decision, the Department of General Services (DGS) incorporated fair–share language into its EIRs and negotiated payments with local agencies. For example, DGS agreed to negotiate fair–share payments with the City of Sacramento for local intersections negatively affected by the state’s East End Office Complex project. Similarly, the state has negotiated its CEQA obligations with local communities in the construction of state prisons. Thus, we do not expect DGS’ policies to be affected by Marina.

As the preceding sections have shown, college campuses and the communities that host them have a shared stake in how the effects of campus expansion are accommodated, reduced, or avoided. The Legislature also can play an important role in planning for campus growth. This can take several different forms:

- Assessing the Need for Growth. The Legislature can limit the environmental impact and the associated mitigation costs of campus growth by requiring fuller utilization of facilities on a year–round basis and scrutinizing the segments’ assumptions about growth in campus plans.

- Clarifying CEQA. The Legislature can reduce the legal conflicts between campuses and communities by clarifying key provisions of CEQA. Even after the Marina decision, some parts of the law are the source of some disputes.

- Appropriating Mitigation Funding. The Legislature will be asked to address the off–campus mitigation costs associated with campus growth. It will confront difficult policy choices concerning the oversight, source, and timing of these payments.

Future student enrollment is one of the main drivers of a campus’ physical plan. For example, the demand for new academic facilities and housing units depends in part upon how many additional students enroll at the campus. Thus, a campus will develop a campus plan by first projecting the number of additional students it plans to enroll in future years.

The demand for mitigation payments to local agencies results from new campus plans that expand enrollments at California’s public colleges and universities. In order to minimize the mitigation costs of campus plans, the Legislature should consider if the expansion in capacity outlined in each campus plan is necessary. Specifically, the Legislature should consider whether (1) the envisioned level of growth in the campus plan is reasonable and (2) alternative methods of accommodating enrollment growth could have smaller environmental impacts.

Unlike enrollment in compulsory programs such as elementary and secondary schools, which corresponds almost exclusively with changes in the school–age population, enrollment in higher education responds to a variety of factors. Some factors, such as population growth, are largely beyond the control of the state. Others, such as financial aid policies, stem directly from policy choices. In general, enrollment growth corresponds to:

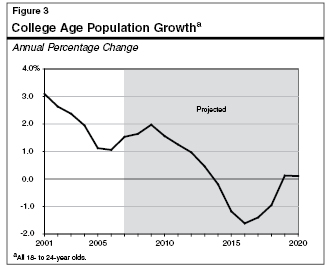

- Demographics—Population Growth. Other things being equal, an increase in the state’s college–age population causes a proportionate increase in those who are eligible to enroll in each of the state’s higher education segments. Enrollment projections, particularly for UC and CSU, are heavily affected by estimates of growth in the college–age “pool” (18–to 24–year old population). This population has grown modestly in recent years (see Figure 3). Annual growth rates will peak around 2009, and will slow thereafter. In fact, between 2014 and 2020, the state’s college–age population is projected to decline each year.

- Policy Choices and Priorities—Participation Rates. For any subgroup of the general population, the percentage of individuals enrolled in college is that subgroup’s college participation rate. However, projecting future participation rates is difficult because students’ interest in attending college is influenced by various factors (including student fees and the attractiveness of job opportunities). In addition, policy actions to expand outreach or financial aid can increase overall participation.

UC and CSU Enrollment Projections. The Legislature requested UC and CSU to provide systemwide enrollment projections through at least 2020 by March 25, 2008. Each segment is expected to explain and justify the assumptions and data used to calculate the enrollment projections. As mentioned above, assumptions about population growth, demographic changes, participation rates, and state funding will be important factors to consider in evaluating the segments’ enrollment projections.

CCC Enrollment Projections. Since community colleges tend to serve local populations, rather than the statewide population like UC and CSU, changes in statewide demographics and participation rates are not as useful in enrollment planning. For example, even if the college–age population is declining in the state as a whole, individual community college districts in rapidly growing areas may experience expanding enrollment demand. Consequently, any discussion about expanding enrollment capacity at community colleges should focus on projections for local demographic changes. As described below, however, even rapidly growing districts could consider other methods for accommodating growth in addition to expanding physical capacity.

Student enrollment increases do not necessarily require a proportionate expansion of facilities. This is because all three segments have unused capacity that can accommodate additional students. Some campuses could make fuller use of their existing space and accommodate more students during the traditional academic year without expanding physical capacity, while virtually all campuses could accommodate more students during the summer term. Prior to approving campus growth projects, the Legislature should evaluate if a campus is fully utilizing its existing facilities.

Operating campuses on a year–round schedule—which more fully utilizes the summer term—is an efficient strategy for serving more students while reducing the costs associated with constructing new classrooms, including any fair–share payments required for increasing campus capacity. Accordingly, the Legislature has encouraged both UC and CSU to serve more students during the summer term.

Over the last five years, UC has steadily increased summer enrollment, while CSU’s summer enrollment is still below its 2002 and 2003 levels. Both segments still have significant unused capacity in the summer. The UC’s summer 2006 enrollment was 21 percent of fall 2006 enrollment and CSU’s was 12 percent. As shown in Figure 4, the summer enrollment for each segment varied significantly by campus.

|

|

|

Figure 4

Year Round Operations at UC and CSU |

|

Campus |

Full-time Equivalent Students |

Summer As

Percent of Fall |

|

Summer 2006 |

Fall 2006 |

|

University of California |

|

|

|

Berkeley |

3,928 |

30,911 |

13% |

|

Davis |

5,676 |

25,419 |

22 |

|

Irvine |

6,684 |

23,358 |

29 |

|

Los Angeles |

7,620 |

31,052 |

25 |

|

Merced |

34 |

1,259 |

3 |

|

Riverside |

3,435 |

15,204 |

23 |

|

San Diego |

3,930 |

24,450 |

16 |

|

Santa Barbara |

5,847 |

19,567 |

30 |

|

Santa Cruz |

2,202 |

14,849 |

15 |

|

Totals |

39,356 |

186,069 |

21% |

|

California State University |

|

|

|

Bakersfield |

756 |

6,979 |

11% |

|

Channel Islands |

— |

2,640 |

— |

|

Chico |

330 |

15,025 |

2 |

|

Dominguez Hills |

1,207 |

8,640 |

14 |

|

East Bay |

4,253 |

10,979 |

39 |

|

Fresno |

— |

18,844 |

— |

|

Fullerton |

3,496 |

27,025 |

13 |

|

Humboldt |

465 |

6,876 |

7 |

|

Long Beach |

3,620 |

28,592 |

13 |

|

Los Angeles |

6,216 |

16,187 |

38 |

|

Maritime Academy |

— |

886 |

— |

|

Monterey Bay |

119 |

3,612 |

3 |

|

Northridge |

2,481 |

26,650 |

9 |

|

Pomona |

4,874 |

17,527 |

28 |

|

Sacramento |

1,395 |

23,153 |

6 |

|

San Bernardino |

3,146 |

13,776 |

23 |

|

San Diego |

2,753 |

28,920 |

10 |

|

San Francisco |

2,725 |

23,950 |

11 |

|

San Jose |

1,451 |

23,304 |

6 |

|

San Luis Obispo |

2,152 |

17,620 |

12 |

|

San Marcos |

586 |

7,089 |

8 |

|

Sonoma |

— |

7,466 |

— |

|

Stanislaus |

718 |

6,314 |

11 |

|

Totals |

42,741 |

342,055 |

12% |

|

|

Summer enrollment at CCC was approximately 30 percent of fall enrollment in 2005. The community colleges have many districts in growing areas of California experiencing increased enrollments that will have to be addressed. If these districts improve their year–round operation, their need to expand physical capacity will be considerably smaller. For example, eight CCC campuses with projects to expand their physical capacity in the Governor's budget have summer enrollments that are less than 20 percent of their primary–term enrollment.

Once the above issues concerning enrollment growth and increased utilization of facilities have been resolved, it is likely that some campuses would still need to increase their capacity in developing new campus plans. This leads to two additional issues that the Legislature will encounter—continued legal disputes over CEQA requirements and the structure of legislative appropriations for mitigation costs.

Generally, the Marina decision states that fair–share payments to local agencies are a feasible alternative for complying with CEQA’s requirement to mitigate off–campus environmental impacts, and that the lead agency retains responsibility for determining the size of that payment. However, parts of the Marina decision and the CEQA statute itself remain subject to conflicting interpretations, as discussed further below, and as highlighted by CSU’s adopted policy for off–campus mitigation (see “How Does the Marina Decision Affect CSU” discussed earlier in this write–up). The Legislature could clarify its intent through budget language or by amending the statute. In any event, we expect the following issues to be the focus of future legal conflicts between the higher education segments and local communities.

The Marina decision specified that a campus may make fair–share payments to localities as a means of mitigating off–campus impacts. There are, however, still points of dispute. For example, neither CEQA nor the Marina decision addresses how an EIR must define the amount or timing of fair–share payments. Is it sufficient to simply state in the EIR that the campus will contribute its fair share toward the cost of off–campus mitigation measures once they are triggered? Localities would likely prefer more specificity on how the campus’ fair share will be calculated and its method of payment, as well as some guarantee that the campus will follow through. This issue has already caused some host communities to file lawsuits challenging campus plans. In deciding one such suit, in August 2007, a Superior Court concluded there was inadequate specificity and enforceability in two mitigation measures identified in the EIR committing UC Santa Cruz to make fair–share payments for transportation improvements under the control of the City of Santa Cruz.

The language of CEQA and the Marina decision requires state agencies to mitigate significant impacts when it is feasible to do so, while simultaneously requiring them only to “request” funds in their budgets for those mitigation efforts. As mentioned previously, CSU has implemented a policy whereby it requests funds for off–campus mitigation payments, but will proceed with the implementation of campus plans whether or not the Legislature actually appropriates the funding. At the time this analysis was prepared, the City of San Diego was in the process of filing a lawsuit arguing that a campus plan should not be allowed to proceed if fair–share mitigation payments are not guaranteed.

CSU’s Policy Raises a Variety of Concerns. Although a court will ultimately evaluate CSU’s policy on legal grounds, CSU’s policy also raises serious policy concerns. First, CSU’s policy appears to ignore the Legislature’s intent concerning CEQA and the mitigation of environmental effects—that is, in the absence of legislative funding or in the event of partial funding, CSU’s policy allows projects to proceed without mitigating their environmental impacts. The CEQA is designed to ensure that government agencies consider the environmental effects of their development decisions. In view of this stated policy as well as the Marina decision, we think it is reasonable to treat mitigation costs for off–campus impacts as part of the cost of implementing the campus plan. The costs for off–campus mitigation are as much a part of the campus plan as the costs of constructing buildings and infrastructure. Considering these costs independently, as CSU proposes, means that environmental effects are not being considered equally with other development decisions as CEQA intends. Allowing a campus plan to proceed without mitigating the environmental impacts that are feasible, including off–campus mitigation costs, is inconsistent with CEQA.

The CSU’s policy regarding off–campus mitigation costs is also inconsistent with its policy for on–campus mitigation measures. That is, while CSU requires dedicated appropriations for off–campus mitigation payments, it does not require such appropriations for on–campus mitigation measures. It seems incongruous for CSU to require a specific legislative appropriation for one type of mitigation but not the other.

Lastly, CSU’s policy presumes that by declining to fund all or a portion of off–campus mitigation for a campus, the Legislature nonetheless intends for the campus plan to go forward without mitigating off–campus impacts. Although this could be its intent, the Legislature may deny funding because it expects CSU to use other funds for off–site mitigation or because it does not wish for CSU to proceed with implementation of the campus plan.

Legislature Has Many Options in Considering CSU’s Request for Mitigation Funding. Given the policy concerns noted above, it is important to recognize that the Legislature has many choices on how to respond to CSU’s (or other segments’) requests for off–campus mitigation funds. We discuss the range of choices below.

- Provide Fair–Share Funding with State Funds. If the campus’ growth is a state priority and the fair–share payment is reasonable, the Legislature may make a specific appropriation for off–site mitigation or redirect funds within a segment’s budget for this purpose.

- Share Funding with Segment’s Nonstate Sources. Since campus plans also include the development of nonstate funded buildings that contribute to environmental impacts, the Legislature could make funding contingent upon the segment contributing to off–site mitigation with nonstate capital funds.

- Reject the Request. The Legislature may find that the requested fair–share payment is unreasonably high or greater than the benefits of implementing the campus plan. It also may find that the campus plan does not reflect state priorities. The Legislature could then direct the segment to alter the campus plan or renegotiate the fair–share payment.

In view of CSU’s intention to proceed with campus plans if the Legislature does not approve its funding request, we recommend the Legislature adopt budget language clarifying its intent concerning each budget request for off–site mitigation funds. For example, if the Legislature elects to support a campus plan’s mitigation costs using both state funds and CSU’s nonstate capital funds, it should explicitly state that it expects CSU to meet the balance of off–site CEQA obligations from nonstate sources. Similarly, if the Legislature rejects a mitigation–funding request because it concludes the mitigation costs are not worth the project benefits, it should state its intent as well.

Alternatively, the Legislature could strengthen its role in overseeing mitigation efforts by amending CEQA to clarify that the lack of a specific state appropriation for mitigation shall not by itself allow a lead agency to declare an impact as “significant and unavoidable” and move forward with the project. This would require CSU to revise its policy and provide the Legislature with all the funding options outlined above.

The CEQA is designed to ensure that the costs of environmental protection are addressed when undertaking new developments. Current practices of the CCCCO and SAB only provide state funds for onsite mitigation costs and those on immediately adjacent streets. In view of the Marina decision and in order to better align CEQA with state policy, therefore, we recommend that the Legislature direct CCC and SAB to modify their regulations to allow all reasonable off–site mitigation costs to be covered with state bond funds.

If the Legislature decides to provide state funding to campuses as one source for fair–share payments to local agencies, it will encounter a number of difficult policy questions concerning the source and timing of payment.

The majority of offsite mitigation payments go toward capital investments such as road improvements. The useful lives of these projects make them appropriate for funding from state and local general obligation bonds. Other fair–share payments will be for services such as fire protection. These would most likely take the form of annual disbursements for personnel and operating costs. Current operations should be funded from the segments’ support budgets rather than general obligation bonds.

The Legislature should be aware of potential mitigation costs associated with a campus plan prior to approving any projects outlined in that plan. Determining the fair–share mitigation cost upfront is a good practice because it provides the Legislature and the public a better understanding of the true costs associated with a campus plan. Without such a calculation, a campus plan could move forward without discussion of significant future offsite mitigation costs. Disclosing the mitigation costs of a campus plan and its associated projects allows the Legislature to make project decisions with full information on all the costs associated with that project. An additional advantage is that it requires campuses and localities to meet and negotiate early in the process about the appropriate method for determining fair–share payments.

As described earlier, CSU has done this in its post–Marina campus plans by determining the total fair–share payments necessary for its recent updated Master Plans at SFSU and SDSU. The campuses negotiated with their host cities early in the process so that the CSU Trustees were aware of the off–campus mitigation costs and any disputes surrounding them prior to certifying the EIR and campus plan. Similarly, the mitigation costs and contentious issues can be presented to the Legislature as it considers the campus plans or the specific projects included in them. On the other hand, UC does not negotiate estimated costs with communities in the approval process for its campus plans. This practice prevents the Legislature from understanding the full costs of a campus plan under its consideration.

When an offsite mitigation payment is linked to a specific project such as in a project–level EIR, the timing of the funding is straightforward. The offsite mitigation costs for a single project such as a prison or office building should be included directly in the total project cost and appropriated along the same time frame as the phases of the project. Funds can be transferred to local agencies as they start the specific mitigation measures identified in the EIR.

The timing of funding is more complicated when an offsite mitigation measure is linked to a tiered or phased project with cumulative impacts—such as a campus plan. Such mitigation measures are not implemented until specific trigger points or levels of use are attained (for example, traffic at an intersection reaches a predetermined level of congestion). If a campus plan includes ten new projects that add capacity, it is difficult to determine if the trigger point will be reached after completion of the third building or the tenth building. The phasing of a campus plan’s implementation makes the timing of fair–share payments more complex:

- If the trigger point is reached at the addition of, say, the sixth building, should the project cost of that building include all the mitigation payments?

- Alternatively, should the mitigation payments be spread among all six projects since each contributed to the cumulative impact? Or even among all ten projects envisioned in the plan?

- What if funds are set aside for the mitigation payment and the trigger point is never reached because growth does not meet the expectations of the campus plan?

As a result of these uncertainties, the appropriate funding method for one campus plan might not be appropriate for another due to differing circumstances. Off–campus mitigation can be funded in a number of different ways. We identify three distinct approaches below.

The Upfront Funding Approach. If the estimated costs of off–campus mitigation payments are determined prior to the certification of the EIR and campus plan, one approach for the Legislature is to appropriate the entire payment to the segment upon the certification of the campus plan. The segment would hold the funds in reserve until the locality begins implementing the specified mitigation measures. An added value of this approach is that through the budget process the Legislature would have an opportunity to evaluate the details of the off–campus mitigation payments. Providing the appropriation upfront is also beneficial because it provides guaranteed funding to the segment and locality as they move forward with their capital plans. This approach of appropriating the lump sum amount upfront, however, has one significant disadvantage. Given the uncertainty of the timing of the trigger points and the locality’s schedule for starting the project, the funds could remain unspent while other pressing capital needs are unfunded.

The Incremental Funding Approach. This approach spreads the appropriations out over a number of years, most likely as an addition to the cost of each capital project. As projects move forward, the segment would build a mitigation reserve fund which could be transferred to locals as trigger points are reached. Alternatively, this approach would be appropriate for campuses that agree to make annual payments into a community’s local infrastructure fund. The incremental approach provides more certainty to the segments and localities that at least a minimum amount of funds will be available for mitigation as projects are approved. The incremental approach also reduces the amount of funds sitting in the reserve account for a long period of time. However, given the uncertainty of growth and trigger points, there could be insufficient money in the reserve fund to cover necessary mitigation payments at a given time.

The Trigger Point Funding Approach. The last alternative provides funding for offsite mitigation payments as the trigger points are reached and localities begin to implement the mitigation measures. The major advantage of this approach is that funds are made available when the actual timing and cost of the mitigation measures are known. From the segments’ and local governments’ budgeting perspective, however, this creates difficulties because there are no guarantees the funds will be available when the fair–share payment is necessary. Without providing a dedicated funding source like the upfront or incremental approach, local agencies cannot be certain about the ability to mitigate the impacts caused by the campus and may be hesitant to endorse the campus plan. From an oversight perspective, this approach also does not provide the Legislature with critical information at the appropriate time concerning the full cost of the projects that led to the campus reaching the trigger point. For instance, the Legislature could provide funding for five projects at a relatively low cost only to find that they cumulatively resulted in a large fair–share payment for which CEQA now requires payment.

Determine Funding Approach on a Case–by–Case Basis. As described earlier, the segments have different policies pertaining to fair–share negotiations for off–campus mitigation measures and the campuses have different relationships with their host communities. As a result, we conclude that the Legislature should consider state funding for off–campus mitigation on a case–by–case basis. Allowing each campus the flexibility to negotiate the payment methodology will accommodate the various relationships that exist between campuses and their host communities. Delaying the payment using the trigger point approach is more appropriate for campus plans such as SFSU that reach detailed agreements on the cost and timing of payment. Meanwhile, more contentious campus plans might benefit from the upfront approach so that the Legislature is aware of the approximate cost of the campus plan implementation and local governments are assured of a funding source.

This analysis of off–campus mitigation issues has highlighted the importance of the Legislature’s early involvement in planning for higher education enrollment growth. In our earlier report on UC’s campus planning, we recommended that UC and CSU provide draft campus plans to the Legislature, and that the Legislature hold hearings to review these draft plans in order to express any concerns about the plans before they become final. This process would allow the segments to amend the plan as needed to accommodate any legislative concerns.

In this analysis we have outlined how the Marina decision obligates the campuses of the UC, CSU, and CCC to consider—and most likely pay their fair share for—the negative environmental impacts that their growth has on surrounding communities. Depending upon the policy choices of the Legislature, CEQA requirements to mitigate off–campus impacts could result in significant costs to the higher education segments and the state. We continue to recommend greater legislative oversight over the campus planning process at all three segments—particularly, holding hearings on draft campus plans. Specifically, we recommend the Legislature consider the following issues in its review of campus plans:

- How Much Growth Is Necessary? Prior to expanding its enrollment ceiling, each campus should demonstrate evidence of enrollment demand and adequate year–round utilization of its facilities.

- What Are the Estimated Costs of Off–Site Mitigation? We recommend that the segments include a preliminary estimate of fair–share mitigation costs in order to provide the Legislature a better understanding of the true costs that would be associated with the implementation of the proposed plans.

- What Is the Status of Negotiations With Local Agencies? Given the potential for litigation to add costs and delays to the planning process, it is important for the campuses to initiate discussions with their host communities early in the planning process. Ideally, mitigation costs will be negotiated prior to the legislative hearing and the governing body’s approval of the campus plan and its EIR.

- How Will Mitigation Costs Be Funded? The segments should report on the sources of funding they will use for any off–campus mitigation payments, including any anticipated requests for state funding.

With greater oversight over the campus planning process, we envision that the Legislature will be able to develop campus plans that balance the state’s priorities of increasing college attendance and adequately addressing the concerns of surrounding communities. This approach should reap benefits in the future. Given the immediate effect of the Marina decision, however, we also highlight the following recommendations for the near term:

- Include Language Allowing Payments for Off–Campus Mitigation in Future Bond Proposals. The Legislature has many options in how it decides to pay for off–site mitigation costs. Allowing future bond proposals to provide payments for these costs ensures that the Legislature can include state bond funds as a policy option.

- Directly Address CSU’s Off–Campus Mitigation Policy. The CSU’s off–campus mitigation policy raises numerous concerns which the Legislature should address through budget language or statutory changes.

- Direct CCC and SAB to Allow State Funds for Off–Site Mitigation Costs. The current policies of CCC and SAB, which restrict state funds to specific mitigation costs, are inconsistent with the intent of Marina.

Return to Education Table of Contents, 2008-09 Budget AnalysisReturn to Full Table of Contents, 2008-09 Budget Analysis