- In This Report

Total Expenditures Down by 25 Percent—Due to Drop in Bond Spending. The Governor’s budget proposes $7.5 billion in expenditures from the General Fund, various special funds, bond funds, and federal funds for resources and environmental protection programs in 2013–14. The proposed budget includes $3.6 billion for the Department of Water Resources (DWR), $1.3 billion for the Department of Forestry and Fire Protection (CalFire), and $438 million for the Air Resources Board (ARB), in addition to funding for many other departments. This proposed level of expenditures for 2013–14 is a decrease of $2.4 billion, or 25 percent, below estimated expenditures for the current year. The proposed reduction in spending is almost entirely from bond funds.

Several Proposals Raise Legal Concerns. The budget proposes to use certain revenues for activities that may not be legally allowable given the revenue source. For example, the administration proposes to use funds generated by the recently enacted fire fee for certain fire–related activities that may not be permissible under existing law. As such, the administration proposes statutory changes to modify this fee into a tax. Similarly, the administration proposes to use revenues from the “AB 32 cost of implementation fee” and cap–and–trade auctions for new administrative activities. Given the legal constraints regarding the use of such revenues, we recommend that the Legislature seek Legislative Counsel’s guidance regarding the legal risks of these proposals.

Some Proposed Projects Likely to Commit State to Future Expenditures. The Governor’s budget also includes proposals to initiate projects that would impact state expenditures in future years. For example, the budget proposes $11.3 million for DWR to begin the remediation of the Perris Dam. We are concerned that the Legislature lacks sufficient information at this time to determine the most cost–effective approach to address problems at Lake Perris. The budget also requests $1 million annually from the State Parks Revolving Fund (SPRF) (the primary funding source for state park operations) to support ongoing maintenance and clean up at the Goat Canyon Sediment Basins at the Border Fields State Park. In the past, these activities were funded with other state sources. We are concerned that the Governor’s proposal would put greater fiscal pressure on the state parks system.

Opportunities for Legislative Oversight. The Governor’s budget raises several issues that we believe merit greater legislative oversight. For example, the budget includes various proposals totaling $192 million that would be funded from a new surcharge on investor–owned utility (IOU)electricity bills. Although the California Public Utilities Commission (CPUC) has been collecting this new surcharge since January 2012, it has not been authorized by the Legislature. We also note that a recent audit identified significant weaknesses with CPUC’s budgeting practices that negatively affect its ability to present accurate budget information. These findings raise questions about CPUC’s ability to effectively audit the records and accounts of the utilities that it regulates.

Billions in Appropriated Bond Funds Unspent. Our analysis finds that in many cases, departments in the resources and environmental protection area (such as DWR) have not spent appropriated funds in particular fiscal years as planned. We describe the primary reasons for this problem and recommend that the Legislature takes steps to help ensure better management of bond cash balances and that its priorities are met in terms of project delivery.

Total Spending Down by 25 Percent. The Governor’s budget for 2013–14 proposes a total of $7.5 billion in expenditures from various fund sources—the General Fund, various special funds, bond funds, and federal funds—for programs administered by the Natural Resources and Environmental Protection Agencies. This level is a decrease of $2.4 billion, or 25 percent, below estimated expenditures for the current year. The proposed reduction in spending is almost entirely from bond funds. Specifically, the budget proposes bond expenditures totaling about $1.3 billion in 2013–14—a decrease of $2.3 billion, or about 64 percent, below estimated bond expenditures in the current year.

Multiple Funding Sources; Special Funds Predominate. The largest amount of state funding for resources and environmental protection programs in the budget year—about $3.6 billion (or 49 percent)—would come from various special funds. This reflects a slight decrease of $38 million, or 1 percent, when compared to estimated special fund expenditures in the current year. The primary special funds that support resources and environmental protection programs include funds generated by beverage container recycling deposits and fees, an “insurance fund” for the cleanup of leaking underground storage tanks, the Environmental License Plate Fund, the Fish and Game Preservation Fund, and an electronic waste recycling fee.

General Fund Spending Growing Slowly. The Governor’s budget includes $2.1 billion in expenditures from the General Fund (28 percent of total expenditures) in 2013–14 for resources and environmental protection programs. This is a net increase of $40 million, or 2 percent, from 2012–13, reflecting both General Fund spending increases and decreases. On the increase side, the budget proposes to add $105 million to pay for resources–related bond debt–service costs, an increase of 12 percent above estimated current–year expenditures. The budget also proposes an increase of $28 million for emergency fire suppression and an increase of $17 million for the Wildlife Conservation Board (WCB) to meet a portion of the funding requirements of Proposition 117. On the decrease side, the budget includes a General Fund reduction of $94 million for various activities related to protecting Californians from fires. Most of this reduction ($87 million) is for emergency fire suppression, reflecting an estimated lower level of resources in the budget year after the current year’s fire season drove up spending beyond the amounts initially budgeted, as well as the use of revenues from the recently enacted lumber tax to offset certain costs for reviewing timber harvest plans (THPs) that were previously supported from the General Fund.

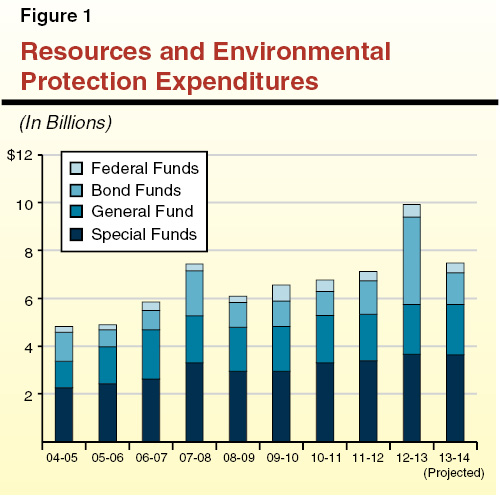

Overall Expenditure Trends. Figure 1 shows total expenditures for resources and environmental protection programs from special funds, the General Fund, bond funds, and federal funds since 2004–05. As indicated in the figure, total spending has generally grown steadily between 2004–05 and 2012–13, averaging roughly an 8 percent annual increase. The increase is mainly due to the availability of a greater amount of special fund revenues. The availability of bond funds also resulted in spikes in spending in certain fiscal years, such as in 2007–08 and 2012–13. As indicated above, the proposed reduction in total expenditures in 2013–14 primarily reflects a lower level of bond expenditures.

Figure 2 shows spending by selected fund sources for the state’s major resources programs and departments—that is programs within the jurisdiction of the Secretary for Natural Resources and the Natural Resources Agency. As the figure shows, total spending proposed for most resources programs is generally down in 2013–14 resulting from a reduction in bond fund expenditures. (We discuss the extent to which bond funds support particular resources programs and the related departments’ ability to spend these funds in a timely manner in greater depth later in this report.) For example, the budget proposes a reduction of $233 million, or 74 percent, in bond spending for the Department of Parks and Recreation (DPR).

Figure 2

Major Resources Budget Summary—Selected Funding Sources

(Dollars in Millions)

|

Department

|

Actual

2011–12

|

Estimated

2012–13

|

Proposed

2013–14

|

Change From 2012–13

|

|

Amount

|

Percent

|

|

Water Resources

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

General Fund

|

$89.6

|

$98.6

|

$97.4

|

–$1.2

|

–1.2%

|

|

State Water Project funds

|

1,074.0

|

1,231.9

|

1,295.9

|

64.0

|

5.2

|

|

Bond funds

|

623.7

|

1,973.3

|

1,072.3

|

–901.0

|

–45.7

|

|

Electric Power Fund

|

5,177.5

|

1,007.4

|

973.9

|

–33.5

|

–3.3

|

|

Other funds

|

89.7

|

148.0

|

139.2

|

–8.8

|

–6.0

|

|

Totals

|

$7,054.6

|

$4,459.2

|

$3,578.7

|

–$880.5

|

–19.7%

|

|

Forestry and Fire Protection (CalFire)

|

|

|

|

|

|

General Fund

|

$651.0

|

$772.3

|

$678.7

|

–$93.6

|

–12.1%

|

|

Other funds

|

383.5

|

468.6

|

580.3

|

111.7

|

23.8

|

|

Totals

|

$1,034.5

|

$1,240.9

|

$1,259.0

|

$18.1

|

1.5%

|

|

Parks and Recreation

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

General Fund

|

$121.2

|

$110.6

|

$114.6

|

$4.0

|

3.6%

|

|

Parks and Recreation Fund

|

136.0

|

148.1

|

130.3

|

–17.9

|

–12.1

|

|

Bond funds

|

273.2

|

311.9

|

79.3

|

–232.6

|

–74.6

|

|

Other funds

|

146.1

|

267.8

|

252.1

|

–15.7

|

–5.8

|

|

Totals

|

$676.5

|

$838.5

|

$576.3

|

–$62.2

|

–31.3%

|

|

Fish and Wildlife

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

General Fund

|

$61.1

|

$61.1

|

$62.7

|

$1.6

|

2.7%

|

|

Fish and Game Fund

|

97.7

|

113.1

|

110.1

|

–3.1

|

–2.7

|

|

Bond funds

|

28.2

|

99.2

|

20.2

|

–78.9

|

–79.6

|

|

Other funds

|

168.9

|

210.6

|

173.3

|

–37.3

|

–17.7

|

|

Totals

|

$356.0

|

$483.9

|

$366.3

|

–$117.6

|

–24.3%

|

|

Resources Secretary

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Bond funds

|

$97.2

|

$66.4

|

—

|

–$66.4

|

—

|

|

Other funds

|

10.5

|

24.6

|

$22.1

|

–2.5

|

–10.2%

|

|

Totals

|

$107.7

|

$91.1

|

$22.1

|

–$68.9

|

–75.7%

|

Despite an overall decline in proposed bond spending for DWR of $901 million, the budget includes the appropriation of new bond funds in 2013–14 for both existing and new programs. For example, the budget proposes to spend an additional $476 million in bond funds from Proposition 84 for grants to local agencies for multi–benefit water projects through the Integrated Regional Water Management (IRWM) program. The budget also proposes $203 million in bond funds from Proposition 1E for flood control projects mostly in Northern California, as well as for flood control planning and emergency response activities. Finally, the budget proposes expenditures of $11 million from Proposition 84 to fund access to recreation and fish and wildlife enhancement at State Water Project (SWP) facilities, specifically the Perris Dam and Reservoir. As we discuss later in this report, the total project at Lake Perris is estimated to cost about $290 million, of which $92 million is being proposed to be paid for with state funds over time.

Similar to Figure 2, Figure 3 shows spending and fund source information for the major environmental protection programs—those within the jurisdiction of the California Environmental Protection Agency (CalEPA). Most of the 17 percent reduction for the State Water Resources Control Board (SWRCB) reflects a reduction of $91 million in bond–funded expenditures and a reduction in spending of $48 million from the Underground Storage Tank Cleanup Fund due to the sunset of a fee increase in 2012. Most of the $60 million, or 24 percent, reduction in funding for the Department of Toxic Substances Control reflects declining revenue from an environmental fee imposed on certain businesses.

Figure 3

Major Environmental Protection Budget Summary—Selected Funding Sources

(Dollars in Millions)

|

Department

|

Actual 2011–12

|

Estimated 2012–13

|

Proposed 2013–14

|

Change From 2012–13

|

|

Amount

|

Percent

|

|

Resources, Recycling, and Recovery

|

|

|

|

|

|

Beverage container recycling funds

|

$1,182.7

|

$1,193.9

|

$1,196.4

|

$2.5

|

0.2%

|

|

Other funds

|

262.8

|

267.8

|

289.1

|

21.3

|

8.0

|

|

Totals

|

$1,445.5

|

$1,461.7

|

$1,485.5

|

$23.9

|

1.6%

|

|

State Water Resources Control Board

|

|

|

|

|

|

General Fund

|

$11.9

|

$14.9

|

$14.7

|

–$0.2

|

–1.1%

|

|

Underground Tank Cleanup

|

315.8

|

329.3

|

281.0

|

–48.3

|

–14.7

|

|

Waste Discharge Fund

|

101.5

|

100.7

|

106.3

|

5.6

|

5.6

|

|

Bond funds

|

51.8

|

137.1

|

45.7

|

–91.4

|

–66.7

|

|

Other funds

|

106.1

|

230.9

|

227.1

|

–3.7

|

–1.6

|

|

Totals

|

$587.1

|

$812.8

|

$674.8

|

–$138.0

|

–17.0%

|

|

Air Resources Board

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Motor Vehicle Account

|

$115.1

|

$116.3

|

$119.9

|

$3.6

|

3.1%

|

|

Air Pollution Control Fund

|

154.4

|

148.6

|

115.0

|

–33.6

|

–22.6

|

|

Bond funds

|

128.6

|

73.0

|

81.6

|

8.5

|

11.7

|

|

Other funds

|

49.1

|

83.8

|

121.2

|

37.4

|

44.6

|

|

Totals

|

$447.3

|

$421.7

|

$437.6

|

$16.0

|

3.8%

|

|

Toxic Substances Control

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

General Fund

|

$19.5

|

$22.2

|

$21.1

|

–$1.1

|

–5.2%

|

|

Hazardous Waste Control

|

45.3

|

48.2

|

51.0

|

2.8

|

5.8

|

|

Toxic Substances Control

|

49.1

|

46.5

|

42.9

|

–3.5

|

–7.6

|

|

Other funds

|

56.4

|

132.6

|

74.1

|

–58.5

|

–44.1

|

|

Totals

|

$170.3

|

$249.5

|

$189.1

|

–$60.4

|

–24.2%

|

|

Pesticide Regulation

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Pesticide Regulation Fund

|

$71.8

|

$75.1

|

$78.2

|

$3.1

|

4.1%

|

|

Other funds

|

6.8

|

7.4

|

2.8

|

–4.6

|

–62.3

|

|

Totals

|

$78.6

|

$82.5

|

$81.0

|

–$1.5

|

–1.8%

|

|

Environmental Health Hazard Assessment

|

|

|

|

|

|

General Fund

|

$2.1

|

$4.4

|

$4.6

|

$0.2

|

4.1%

|

|

Other funds

|

14.9

|

15.5

|

16.3

|

0.8

|

5.1

|

|

Totals

|

$17.0

|

$19.8

|

$20.8

|

$1.0

|

4.9%

|

Since 2000, nearly $20 billion in bond funds have been authorized by California voters for various programs, infrastructure projects, and land acquisitions in the resources and environmental protection areas. In many instances, much of these funds have been appropriated by the Legislature over the years as part of the annual state budget. For example, the Governor’s budget for 2013–14 proposes $1.3 billion in new bond appropriations for resources and environmental protection programs, including $1.1 billion for DWR. The expectation is that departments will spend the appropriated funds in particular fiscal years. However, it appears that billions of dollars in appropriated funds for resources and environmental protection programs remain unspent. Below, we describe the primary reasons for this problem and make recommendations to help ensure that legislative priorities are met and projects are completed.

What Is Bond Financing? Bond financing is a type of long–term borrowing that the state frequently uses to raise money to pay for capital outlay projects to construct or renovate facilities and to acquire land. The state borrows money from investors and then repays the borrowed money (principal) plus interest over a period of years—also called debt service. Debt service is generally paid by the state from the General Fund or a designated revenue source.

How Are Bond Funds Spent? The Legislature appropriates bond funds for projects to state departments during the annual budget process. The amounts of the appropriations are often for the estimated cost of projects over multiple years. Typically, appropriations are available for encumbrance, or commitment to a project, for three years and the encumbrance must be liquidated, or spent, within two years, at which time the unliquidated balance reverts and becomes available for appropriation once more.

In order to liquidate bond appropriations, state departments estimate how much cash is needed to meet expenditures between bond sales (typically every six months). Based on these estimates, the Department of Finance (DOF) determines the amount of bond funds needed, and the Treasurer sells the bonds to meet those needs. The cash from bond sales is deposited in the Pooled Money Investment Account (PMIA)—the state’s short–term savings account—until it is spent by departments on projects.

Departments used to be able to request short–term loans from the PMIA to finance bond–funded projects before the bonds that would pay for the projects had been sold. When bonds were eventually sold, the proceeds repaid the short–term loans, thus reimbursing the state’s cash reserves. However, in December 2008, these PMIA loans were stopped, in part due to the state’s cash flow needs, and bond sales were temporarily halted. Although bond sales resumed in March 2009, loans from the PMIA continue to not be provided.

Bond funds made available to resources and environmental protection programs have not been spent as quickly as anticipated. As a result, certain departments have requested the reappropriation of a significant amount of bond funds previously appropriated by the Legislature. This has particularly been the case for two resources and environmental protection bonds authorized by the voters in 2006. While lag time between when bond funds are appropriated and actually spent is natural, a consistent and extended lag could indicate problems with a department’s ability to deliver projects.

Departments Spend Bond Funds in a Variety of Ways. Departments in the resources and environmental protection areas spend bond funds in several ways: (1) for direct spending on capital outlay projects, (2) to provide grants to local agencies, and (3) to reimburse local agencies for work they have completed. Each of these tools for spending money include a variety of state processes, such as soliciting and awarding grant applications, completing environmental documentation, and locals submitting claims for reimbursement. In addition, there can be restrictions specified in the authorizing bond measure on how the funds must be spent, which can affect a department’s ability to spend bond funds in a timely manner.

Most Resources and Environmental Protection Bonds Appropriated, but Not All Encumbered or Spent. Nearly $20 billion in General Fund–supported bonds for resources and environmental protection programs have been approved by voters since 2000. Of that amount, $18 billion (90 percent) has been appropriated by the Legislature, as shown in Figure 4. However, significantly less has been encumbered and subsequently spent (funds are encumbered prior to being spent). Specifically, as of June 30, 2012, over $5.1 billion in bond funds has been appropriated, but not encumbered. Most of these funds are from the two most recent bonds—Proposition 1E (Disaster Preparedness and Flood Protection Bond Act) and Proposition 84 (Safe Drinking Water, Water Quality and Supply, Flood Control, River and Coastal Protection Bond Act). Both of these measures were approved in 2006. The majority of the unencumbered appropriations—$3.2 billion—are attributable to DWR, in part because much of the funding in Propositions 84 and 1E was allocated to DWR for flood control and IRWM grants.

Figure 4

Status of Resources Bonds

As of June 30, 2012 (In Millions)

|

|

Propositions

|

Totals

|

|

12 (2000)

|

13 (2000)

|

40 (2002)

|

50 (2002)

|

84 (2006)

|

1E (2006)

|

|

Total allocated

|

$2,100

|

$1,970

|

$2,600

|

$3,440

|

$5,388

|

$4,090

|

$19,588

|

|

Amount appropriated

|

2,034

|

1,769

|

2,476

|

3,359

|

4,550

|

3,518

|

17,705

|

|

Appropriations not spent or committed

|

59

|

63

|

214

|

645

|

2,158

|

2,010

|

5,149

|

Resources Departments Have Requested Many Reappropriations in Recent Years. Appropriations generally are intended to reflect the amount and timing of expected spending for both the department making the request and the Legislature approving the request. Therefore, another indicator of bond funds being spent slowly is when funds that were appropriated are not spent within the time allowed by the appropriation (typically within five years, as described above). In order to continue to use these funds for projects, departments must request a reappropriation of the funds from the Legislature. In recent years, departments in the Natural Resources Agency have requested significant reappropriations of bond funds because they have not been able to spend the funds in the allotted time, and thus, deliver the projects on time. In addition, based on current and historical levels of expenditure, the administration is likely to request significant reappropriations of unspent funds for departments in these programs in the spring of 2013.

Many Factors Contribute to Not Spending Bond Funds as Planned. According to the Natural Resources Agency, which provides oversight of bond spending for resources and related spending on environmental protection programs, many factors—both one–time and on–going—have contributed to departments, and in particular DWR, not spending bond funds in a timely manner. Two factors that have had a significant one–time effect on departments’ abilities to spend funds on projects are (1) the 2008 freeze on PMIA loans and temporary halt in bond sales that resulted in the stoppage of some projects until bond sales were resumed in March 2009 and (2) the wet winter that occurred in 2010–11 that resulted in a shortened construction season.

According to the Natural Resources Agency and DWR, some factors continue to contribute to the slow spending of bond funds. These ongoing factors include:

- Difficulty Securing Funding Commitments From Other Sources. In some cases, state cost–sharing obligations require state departments to obtain funding commitments from federal and local partners, rather than undertaking projects using only state funds. As a result, projects can be delayed if funding commitments from federal or local agencies are not readily available.

- Lack of Ability to Move Bond Funds to Other Projects. It can be difficult to move funding from one project to another when there are project delays, primarily because resources departments lack a “shelf” of readily available projects that have gone through preliminary design and cleared environmental reviews.

- Local Reimbursements Not Submitted. Some bond funds are set aside to reimburse local agencies for costs they have incurred, such as for some levee maintenance programs. According to the Natural Resources Agency, some local agencies are not seeking prompt reimbursement for project expenditures. At the time of this report, it is unclear to what extent this is occurring or why it is occurring.

Issues Related to Slow Spending. The failure to spend bond funds in a timely manner can result in issues of legislative concern, specifically:

- Legislative Priorities May Not Be Getting Completed. Much of the unspent cash balances have resulted from bond funds not being spent as quickly as anticipated on DWR’s flood control projects and the IRWM program. As a result, the goals identified in these areas in legislation enacted over the years may not be accomplished in a timely fashion. For example, the reduced risk to life and property from the planned flood control projects are not achieved as quickly as planned.

- Debt–Service Costs Incurred Prior to Benefits. As previously discussed, the state incurs debt–service costs when it sells bonds. Thus, if the bonds are sold but the cash is not spent on projects, the state pays debt service before the benefits of bond–funded projects are realized.

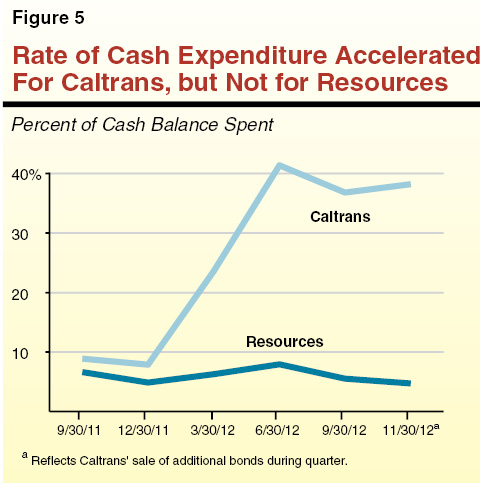

Other Departments Have Spent Bond Funds More Quickly. If departments have large amounts of cash from bond sellers on hand, it may be another indicator of problems with the ability to spend money and deliver projects. In the past, various departments across state government have held large amounts of cash. For example, in September 2011, the California Department of Transportation (Caltrans) and the Office of Public School Construction (OPSC), as well as DWR, were identified as departments having large balances of cash from bond sales that were not being spent. However, as shown in Figure 5, Caltrans has since increased the rate at which it spends its cash on projects and now spends at a much higher rate than resources departments, whose rates of spending have largely been unchanged. Specifically, Caltrans has reduced its outstanding cash balance from $2.3 billion in June 2011 to $540 million in September 2012. In part, this is due to Caltrans’ ability to shift certain bond funds to other projects. For example, Caltrans has a shelf of projects that have gone through preliminary design and received environmental clearances, so if a project is delayed it can shift funds to a project that is ready to begin construction. Similarly, the OPSC had large cash balances in 2011, but has spent them down by creating a prioritized list of projects and funding those projects that are shovel–ready.

Resources Agency Has Taken Steps to Reduce Cash Balances. . . The Natural Resources Agency has recently taken several steps to help reduce the amount of cash it has on hand. First, it has not requested proceeds from a bond sale since fall 2010. Second, the agency has shifted $300 million within various bond acts to other projects to better ensure that available funds are spent. The Natural Resources Agency has also internally begun testing an online cash management system to improve the tracking of cash requests and cash balances. In the coming months, the WCB and the State Coastal Conservancy (SCC) plan to use this new system on a pilot basis. Finally, DWR has started providing monthly updates on the status of projects to DOF and the Treasurer. The expectation is that this would reduce the time it takes for DOF and the Treasurer to approve requests from individual departments to shift cash to projects that are ready to proceed.

. . . But Expenditures Have Not Accelerated. In our view, the above actions are primarily intended to avoid large cash balances in the future. However, they do not appear to have significantly affected the underlying problem regarding the rate at which resources departments spend bond funds, as shown in Figure 5. This continued problem has caused further delay in the delivery of projects that the Legislature assumed—in most cases—would have already been completed.

Ensuring that appropriated bond funds are spent in a timely manner is important to meet legislative priorities. In addition, accurately estimating anticipated expenditures by departments in the resources and environmental protection areas for a specified period of time can help to reduce the amount of debt–service costs the state pays before cash is actually needed. In view of the ongoing problems we identified above, we recommend that the Legislature take steps to help ensure better management of bond cash balances and, more importantly, that its priorities are met in terms of project delivery. Specifically, we recommend:

- Require Report at Budget Hearings on Efforts to Accelerate Spending. We recommend the Natural Resources Agency and DWR report at budget subcommittee hearings this spring on their specific plans to accelerate bond fund expenditures. At the hearing, the agency and the department should identify burdensome reimbursement processes that could be streamlined or other reasons why locals may be slow to access funds that they are eligible to receive. These budget hearings also present a good opportunity for the Legislature to carefully consider reappropriations by inquiring about the status of projects, and hear from departments on why projects may not be moving as quickly as the Legislature would like.

- Hold Policy Committee Oversight Hearing on Project Delivery. We also recommend the Legislature hold an oversight hearing on the challenges to completing resources projects, with a focus on flood control and IRWM projects—the two areas with the largest unspent appropriations. At the hearing, DWR and the Natural Resources Agency could report on the problems that have contributed to slow expenditures of funds, possible solutions within existing departmental authority, and fixes that would require legislative changes. In addition, the oversight hearing could focus on existing delivery models for expending bond funds on projects and the strengths and weaknesses of each. For example, the hearing could explore how to effectively balance the trade–offs between expediting projects and maximizing state dollars by leveraging federal and local contributions.

- Require Supplemental Report on Cash Balances. We also recommend the Legislature adopt supplemental report language requiring the Natural Resources Agency to report by January 1, 2014, on the status of its cash balance, what steps it has taken to accelerate expenditures, and on the amount of expenditures per quarter—from June 2011 to June 2013—by bond allocation.

Under the state’s Z’Berg–Nejedly Forest Practice Act of 1973, timber harvesters must submit and comply with an approved THP. The THP describes the scope, yield, harvesting methods, and mitigation measures that the timber harvester intends to perform within a specified geographical area. The process of preparing a THP is functionally equivalent to preparing an environmental impact report (EIR). After the plan is prepared, it is reviewed and approved by the lead agency, CalFire, with assistance from the Department of Fish and Wildlife (DFW), the Department of Conservation (DOC), and SWRCB.

Prior to 2012–13, the above state regulatory activities were funded mainly from the General Fund. In addition, DFW and SWCRB also levied a few fees for various THP–related permits to support such activities. However, as a result of the state’s fiscal condition over the last ten years, General Fund support for THP–related activities was reduced. This was particularly evident at DFW, which resulted in DFW only conducting a minimal review of THPs. As a result, the Legislature adopted Chapter 289, Statutes of 2012 (AB 1492, Blumenfield), which authorized a tax on the sale of lumber products in California effective January 2013 to replace both the General Fund and fee support of THP regulatory activities. Revenues collected from this tax are deposited into the Timber Regulation and Forest Restoration Fund.

The Governor’s budget for 2013–14 proposes an augmentation of $6.6 million from the Timber Regulation and Forest Restoration Fund and 49.3 new, three–year limited term positions for THP regulation. As indicated in Figure 6, the proposed positions and funding would be allocated across the four departments responsible for reviewing THPs, as well as to the Natural Resources Agency. The current total level of staffing across the four departments is 142 positions and the addition of proposed staff represents a 35 percent increase from current staffing levels.

Figure 6

Positions Proposed for Timber Harvest Plan Regulation

|

Agency/Department

|

2012–13 Positions

|

Proposed Increase for 2013–14

|

|

Positions

|

Funding

|

|

Department of Fish and Wildlife

|

8.7

|

35.0

|

$4,306,000

|

|

CalFire

|

95.0

|

6.0

|

967,000

|

|

State Water Resources Control Board

|

26.4

|

4.3

|

620,000

|

|

Department of Conservation

|

12.1

|

2.0

|

515,000

|

|

Natural Resources Agency

|

—

|

2.0

|

217,000

|

|

Totals

|

142.2

|

49.3

|

$6,625,000

|

The proposed positions at DFW, SWCRB, and DOC would restore staffing for THP regulation at these departments to their 2007 staffing levels, in order to ensure that THPs receive the legally required reviews. The additional six positions requested for CalFire are intended to allow the department to complete additional reporting requirements and search for opportunities to increase efficiency, as required by Chapter 289. According to the administration, the two positions requested for the Natural Resources Agency will coordinate activities across the above resources departments and act as the point of contact for questions and information regarding the regulation of the state’s timber harvest industry.

We find that the requested positions and funding for THP regulation would help ensure that THPs receive the level of review required under existing state law, as well as meet the specific requirements of Chapter 289. Accordingly, we recommend that the Legislature approve the request for 49.3 positions and $6.6 million in funding from the Timber Regulation and Forest Restoration Fund. However, we would note that the workload associated with the THP program is consistent and ongoing, as is the proposed funding source. Thus, we further recommend that the Legislature approve the 47.3 requested positions for DFW, SWCRB, and DOC on a permanent basis, rather than on a three–year, limited–term basis as proposed by the Governor. Permanent position authority can help the departments attract a stronger pool of candidates, especially for the more technical positions such as foresters, geologists, and environmental scientists.

The state protects and preserves unique ecological features in ten conservancies through land acquisition and restoration. The conservancies are mostly supported through certain bond funds that have been authorized in various measures passed by the voters. However, most of the bond funds supporting the conservancies have already been appropriated and will be spent soon. For example, the Governor’s budget reflects significantly less in expenditures for the conservancies in 2013–14 compared to the 2012–13 level. Below, we (1) provide an overview of the structure and funding of the state’s conservancies and (2) discuss possible reorganizational strategies to maximize efficiency, ensure the best possible use of remaining funds, and improve the state’s system of land conservation.

Conservancies Focus on a Specific Geographic Area. The state’s ten conservancies focus on land conservation within very specific geographic areas of California specified in state law, as shown in Figure 7. Each conservancy is overseen by a separate governing board of 7 to 21 members. Board members include representatives from state and local governments, and sometimes the federal government. Conservancies focus their land acquisition and management efforts on a particular geographic area, such as Lake Tahoe, the San Diego River, and the state’s coastline. In addition to land acquisition, conservancies can facilitate the purchase of land by other entities (such as local governments or non–profit agencies) for conservation purposes. This could include awarding grants to other entities to purchase property for preservation purposes, as well as participating in transactions to trade or consolidate land parcels among various entities to make conservation efforts feasible. Although some state departments (such as WCB, DFW, and DPR) also acquire and manage lands to promote public access and preservation of fish and wildlife resources, these departments generally lack the local perspective inherent in the conservancies. The Natural Resources Agency is responsible for overseeing all land conservation activities and spending in the state.

Figure 7

State Conservancies and Their Jurisdictions

|

Conservancy

|

Year Established

|

Jurisdiction

|

Scope

|

|

State Coastal Conservancy

|

1976

|

Coastal Zone

|

1,100 miles of coast

|

|

Santa Monica Mountains Conservancy

|

1979

|

Santa Monica and Santa Susanna Mountains and Placerita Canyon in Los Angeles and Venture counties

|

551,000 acres

|

|

California Tahoe Conservancy

|

1984

|

Lake Tahoe Basin in El Dorado and Placer counties

|

148,000 acres

|

|

San Joaquin River Conservancy

|

1995

|

San Joaquin River Parkway in Fresno and Madera counties

|

5,900 acres

|

|

Coachella Valley Mountains Conservancy

|

1996

|

Coachella Valley in Riverside County

|

1.25 million acres

|

|

San Gabriel and Lower Los Angeles Rivers and Mountains Conservancy

|

1999

|

San Gabriel River and Lower Los Angeles River Watersheds in Los Angeles and Orange counties

|

569,000 acres

|

|

Baldwin Hills Conservancy

|

2001

|

Baldwin Hills area of Los Angeles County

|

1,200 acres

|

|

San Diego River Conservancy

|

2002

|

San Diego River Watershed in San Diego County

|

52 miles of river

|

|

Sierra Nevada Conservancy

|

2004

|

Sierra Nevada mountain range

|

25 million acres

|

|

Sacramento–San Joaquin Delta Conservancy

|

2009

|

Delta and Suisun Marsh in Yolo, Sacramento, Solano, and Contra Costa counties

|

832,000 acres

|

Conservancy Activities Driven by Bond Fund Allocations. General obligation bonds approved by the voters are the main source of funding for the land acquisition–related activities of the conservancies. For example, since 2000, the voters have approved four different bond measures—Propositions 12, 40, 50, and 84—that included funding for conservancies. Each bond measure specified a certain level of funding for each conservancy and contained restrictive parameters for how such funds could be spent, such as prohibiting the transfer of funding allocated for one conservancy to another conservancy or state agency. Generally, conservancies use bond funds for “opportunity purchases”—working off of a general conservation plan and purchasing related property as it becomes available. Since this type of purchase usually cannot be anticipated, the Legislature often approves bond appropriations that are not tied to specific projects or land acquisitions. In addition, under each of these bond measures, five percent of the bond funds allocated to a conservancy can be used to support the administration of the funds.

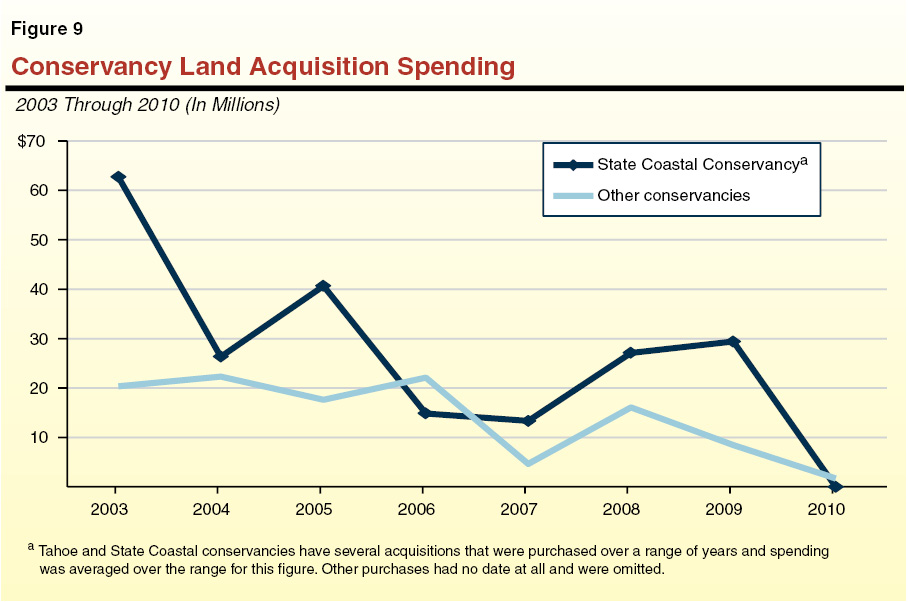

Most Bond Funds Have Been Appropriated. Figure 8 summarizes the status of the bond funds that have been allocated to each conservancy. As indicated in the figure, almost 80 percent of the bond funds recently allocated to conservancies from Propositions 12, 40, 50, and 84 have been appropriated. About 60 percent of the allocated funds have already been encumbered or spent. As a result of the diminishing funds, and other factors such as the state’s bond freeze in 2008, spending for land acquisitions declined significantly between 2003 and 2010. For example, as shown in Figure 9, land acquisition spending for the SCC declined from slightly more than $60 million in 2003 to nothing in 2010. The Natural Resources Agency predicts that individual conservancies will spend their remaining bond funds between 2014 and 2019.

Figure 8

Recent Bonds Have Allocated Significant Amount of Funding to Conservancies

(In Millions)

|

|

Allocation

|

Appropriated

|

Spent or Encumbered

|

Unappropriated

|

|

State Coastal Conservancy

|

$1,232.0

|

$942.8

|

$683.0

|

$279.3

|

|

Santa Monica Mountains Conservancy

|

186.6

|

151.0

|

144.4

|

35.6

|

|

California Tahoe Conservancya

|

166.0

|

163.5

|

144.5

|

2.5

|

|

San Joaquin River Conservancy

|

76.0

|

16.0

|

15.3

|

60.0

|

|

Coachella Valley Mountains Conservancy

|

61.0

|

60.6

|

40.6

|

0.4

|

|

San Gabriel and Lower Los Angeles Rivers and Mountains Conservancy

|

112.8

|

112.7

|

92.4

|

0.1

|

|

Baldwin Hills Conservancy

|

50.0

|

48.0

|

23.8

|

2.0

|

|

San Diego River Conservancyb

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

|

Sierra Nevada Conservancy

|

54.0

|

51.9

|

33.0

|

2.1

|

|

Sacramento–San Joaquin Delta Conservancyb

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

|

Totals

|

$1,938.4

|

$1,546.4

|

$1,176.9

|

$392.0

|

Governor’s Budget Reflects Availability of Fewer Bond Funds. Consistent with the decline in the amount of bond funds available for the state’s conservancies, the Governor’s budget proposes total spending of $23.5 million in 2013–14 for the ten conservancies. As shown in Figure 10, this amount is $25.6 million, or 52 percent, less than the 2012–13 spending level. The proposed expenditures for 2013–14 reflects appropriations for land acquisition, several reappropriations, and the reversion of bond funds to help pay for existing permanent positions at the conservancies.

Figure 10

Conservancies Budget Summary

(Dollars in Thousands)

|

|

Actual 2011–12

|

Estimated 2012–13

|

Proposed 2013–14

|

Change From 2012–13

|

|

Amount

|

Percent

|

|

State Coastal Conservancy

|

$70,745

|

$10,932

|

$8,745

|

–$2,187

|

–0.2%

|

|

Santa Monica Mountains Conservancy

|

2,661

|

957

|

814

|

–143

|

–14.9

|

|

California Tahoe Conservancy

|

8,861

|

10,064

|

4,922

|

–5,142

|

–51.1

|

|

San Joaquin River Conservancy

|

529

|

631

|

644

|

$13

|

2.1

|

|

Coachella Valley Mountains Conservancy

|

5,242

|

461

|

460

|

—

|

–0.2

|

|

San Gabriel and Lower Los Angeles Rivers and Mountains Conservancy

|

762

|

1,005

|

736

|

–269

|

–26.8

|

|

Baldwin Hills Conservancy

|

3,318

|

552

|

567

|

15

|

2.7

|

|

San Diego River Conservancy

|

344

|

358

|

331

|

–27

|

–7.5

|

|

Sierra Nevada Conservancy

|

4,150

|

22,639

|

4,794

|

–17,845

|

–78.8

|

|

Sacramento–San Joaquin Delta Conservancy

|

956

|

1,473

|

1,506

|

33

|

2.2

|

|

Totals

|

$97,568

|

$49,072

|

$23,519

|

–$25,553

|

–52.1%

|

Reduced Funding Shifts the Focus and Role of Conservancies. As a result of the decline in bond funds available for the state’s conservancies, the nature of the work performed by conservancies has been changing. Specifically, conservancies are becoming less and less responsible for acquiring new land or administering grant programs. Instead, they are now becoming more involved in (1) the ongoing management and restoration of state lands (either directly or by providing funds to local and private organizations), (2) maintaining and creating partnerships with local entities (such as nonprofits), and (3) planning for future acquisitions and activities to the extent that new bond funds become available in the future.

If additional bond funding is not authorized, the total workload activities of the conservancies will decline. We would note, however, that because most conservancies have few permanent staff, reductions in workload would likely result in fractions of positions (rather than entire positions) becoming unnecessary in the future.

The amount of bond funds available to conservancies is declining and the availability of future bond funds is uncertain. This creates an opportunity to reevaluate the state’s approach to land conservation to help ensure that statewide resources needs are defined and prioritized and that available funds are being used efficiently. Specifically, we note that maintaining a large number of geographically distinct, separately funded conservancies can make it difficult for the state to achieve its conservation goals. This is because each conservancy receives a portion of the limited statewide funding, even though higher state priorities may exist elsewhere. The California Performance Review’s report in 2005, for example, concluded that the state currently lacks a comprehensive and cohesive statewide land conservation plan. In addition, reorganization could create administrative efficiencies because under the current structure each conservancy incurs administrative costs in the hundreds of thousands of dollars, and higher, even for only a few staff. Consolidation of administrative functions across conservancies could reduce state costs and stretch bond funds further. For example, the SCC already performs some human resources work for small conservancies. This and other types of similar approaches could be expanded.

Below, we identify and review two possible options for reorganization that could help address these issues—specifically, the consolidation and the elimination of certain conservatories.

Consolidation of Existing Conservancies. As conservancies spend the remainder of their existing bond funds and their workload correspondingly declines, the Legislature could consider consolidating some or all of the state’s ten conservancies. This would allow the state to maximize its use of the remaining bond funds for conservancies by creating new efficiencies. For example, consolidating certain conservancies could reduce the amount they currently spend in total on administrative costs, given that there would be fewer governing boards to support. (As we discuss below, there could be some short–term challenges to shifting bond funds across conservancies.)

As indicated above, the current fragmentation of the state’s conservancies has made it challenging for the state to maintain a comprehensive statewide plan and goals for conservation. Such a fractured approach is apparent in the SCC, whose jurisdiction stretches across the state’s coastline. This is because other state conservancies—Baldwin Hills, Santa Monica Mountains (SMMC), San Diego River, and San Gabriel and Lower Los Angeles Rivers and Mountains (RMC) conservancies—are currently situated near or on the coast with some goals that overlap with the SCC. Consolidating the SCC with these other conservancies would reduce such overlap and allow the state to maintain a more effective and efficient approach regarding the conservation of the coastline. Similarly, the WCB acquires land on behalf of the San Joaquin River Conservancy (SJRC), and could be expanded to include the conservancy. Alternatively, the Legislature could consolidate all of the individual conservancies and create one conservancy board within the Natural Resources Agency.

While consolidation would help achieve efficiencies and provide a more statewide perspective towards land conservation, we recognize that some conservancies might not be well suited for consolidation given their unique roles—specifically the Tahoe and Delta conservancies. This is because the Tahoe Conservancy plays a key role in the state’s Tahoe compact with Nevada and the Delta Conservancy is designed to foster relationships among the disparate stakeholders of the San Joaquin River delta. In view of their critical roles within each of their regions, consolidating them with another conservancy could create more challenges than benefits.

We also note that any consolidation of existing conservancies should seek to help maintain local relationships. This is because conservancies were created separate from larger departments in the resources area partially due to their ability to connect with local governments and organizations. Opportunities for local input could be retained by making sure that any type of consolidation retains existing relationships with local joint power authorities or local advisory groups. We acknowledge, however, that there could be some short–term challenges in consolidating existing conservancies. For example, previously authorized bond acts restrict the use of a specified amount of bond funds for each conservancy. Such restrictions could make it somewhat difficult in the near term to achieve statewide prioritization of conservation activities and administrative efficiencies through consolidation (that is, until such bond funds are spent). Specifically, remaining bond funds must be spent based on their allocations, regardless of the state’s highest priorities. Additionally, administrative costs associated with bond spending—five percent of bond proceeds—must remain within the allocation for each bond and each conservancy. For example, if SMMC and other conservancies are consolidated into the SCC, economies of scale could allow fewer positions to manage one consolidated grants program, rather than having a grant manager function in each conservancy. However, it is possible that each position in this consolidated program would have to be funded from multiple conservancies’ bond allocations from within multiple bonds. Going forward, however, future bond measures could be designed in ways that provide for greater flexibility to use funds across conservancies so that the state can fund conservation priorities consistent with state conservation goals.

Elimination of Certain Conservancies. Another option would be to eliminate some conservancies, mainly those that may no longer be of great significance to the state given that their activities and governance maintain a local (rather than state) focus. For example, the Coachella, SJRC, Baldwin Hills, RMC, and SMMC conservancies currently focus on more local concerns and often have significant involvement of their respective local governments. As such, these particular conservancies could become joint powers authorities outside of the existing state board structure.

The decline in the availability of bond funds for state conservancies presents an opportunity for the Legislature to reevaluate the state’s land conservation efforts and ensure that all activities are efficient and cohesive. However, given the trade–offs we discussed above, any such reorganization should be done carefully to preserve the conservancies’ unique role of bridging local needs and interests with state protection and preservation of unique geographical features. Given, the Natural Resource Agency’s statewide role for land conservation, we believe that it is in an ideal position to evaluate various organizational options, including consolidation, to improve the role of conservancies in the state. Therefore, we recommend that the Legislature adopt supplemental report language directing the Natural Resources Agency to prepare a report that evaluates the advantages, disadvantages, and cost implications of various options for reorganization of the state’s ten conservancies by January 1, 2014.

Background. Chapter 485, Statutes of 2012 (AB 2443, Williams), requires the imposition of a quagga and zebra mussel infestation prevention fee on vessels. The measure states that the fee would be determined by the existing Department of Boating and Waterways, in consultation with a technical advisory group. (Under a larger reorganization plan adopted as part of the 2012–13 budget package, the Department of Boating and Waterways will become the Division of Boating and Waterways within DPR on July 1, 2013.) The revenue from the fee would be deposited in the Harbors and Watercraft Revolving Fund (HWRF) and used to administer invasive mussel monitoring, inspection, and infestation prevention programs. Specifically, the measure states that the funds are available to support a new grant program to provide entities that operate water reservoirs funding to defray the costs of developing and implementing mussel infestation prevention plans. This new program will be administered by the new Division of Boating and Waterways. The measure also states that the fees would support costs incurred by the division to determine an appropriate fee level and adopt regulations regarding the new grant program, as well as some current efforts of DFW to prevent mussel infestations in areas of the state where a prevention plan is not in place.

Positions and Funding Requested to Implement Chapter 485. The Governor’s budget proposes two positions and $361,000 from the HWRF in 2013–14 to support the mussel infestation prevention activities specified in Chapter 485. Specifically, the budget proposes:

- $150,000 for the Division of Boating and Waterways to assemble and facilitate a technical advisory group to determine the amount of the fee and other related activities.

- $85,000 and one position at the division to implement the new grant program and oversee the development of regulations for the program.

- $126,000 and one position at DFW to assist the Division of Boating and Waterways with the development of the grant program and to review grant applications.

In addition, under the budget proposal the level of funding proposed for 2013–14 would increase by $283,000 in 2014–15 to support eight temporary help employees to assist local operators that are implementing prevention activities. The Governor’s budget does not include any funding in 2013–14 for the actual grants that would be provided to entities that operate water reservoirs as part of the new program being developed by the Division of Boating and Waterways, as the initial grants will not be awarded until 2014–15.

Request for Staff at DFW Is Somewhat Premature. While most of the funding and positions proposed in the Governor’s budget for mussel infestation prevention activities appear justified on a workload basis related to Chapter 485, we find that the requested position at DFW is slightly premature. This is because the majority of the workload associated with the proposed position will not begin until grant applications are reviewed in late 2013–14 and grants are awarded in 2014–15. Thus, we recommend that the Legislature approve the position and funding on a half–year basis for 2013–14, resulting in savings of $75,000 from HWRF.

Background. Proposition 117, approved by voters in 1990, requires the state to provide $30 million annually for 30 years (from 1990–91 through 2019–20) to (1) WCB; (2) coastal, Tahoe, and Santa Monica Mountains conservancies; and (3) state and local parks programs. Under the measure, funds are to be used to acquire, enhance, or restore specified types of lands for wildlife or open space. The measure requires that a portion of the above funding requirement be met using 10 percent of the funds in the Proposition 99 (Tobacco Tax) “unallocated account.” The remainder is to come from existing environmental funds or the state General Fund. In recent years, environmental bond funds were used to help meet the Proposition 117 funding requirement, rather than the General Fund. For example, $24 million in Proposition 1E (Disaster Preparedness and Flood Protection Bond Act of 2006) funds were used to meet the current–year funding requirement.

Governor Proposes General Fund Support to Meet Proposition 117 Requirement. The Governor’s budget for 2013–14 proposes to appropriate $9 million in Proposition 99 funds to meet a portion of the proposition’s funding requirement in the budget year. The Governor proposes $21 million from the General Fund to meet the remainder of the $30 million funding requirement. Specifically, the budget provides $17 million to WCB and $4 million to SCC.

Bond Funds May Be Available to Meet Proposition 117 Requirement. Based on information we received from WCB and DWR, it is possible that funds from Proposition 1E are available to help meet the Proposition 117 funding requirement. Specifically, according to DWR there is at least $21.5 million in uncommitted funds from Proposition 1E that could be reverted and appropriated for this purpose.

At the time of the Governor’s May Revision to the 2013–14 budget, additional information will be available about how much of the uncommitted Proposition 1E funds identified above could be used to meet the Proposition 117 requirement. Accordingly, we recommend that the Legislature withhold action on the proposed $21 million in General Fund pending additional information this spring.

CalFire, under the policy direction of the Board of Forestry and Fire Protection, provides fire protection services directly or through contracts for timberlands, rangelands, and brushlands owned privately or by state or local agencies. These areas of CalFire responsibility are referred to as “state responsibility areas” (SRA) and represent approximately one–third of the acreage of the state. In addition, CalFire regulates timber harvesting on forestland owned privately or by the state and provides a variety of resource management services for owners of forestlands, rangelands, and brushlands.

Chapter 8, Statutes of 2011 (ABX1 29, Blumenfield), authorized a fee on all habitable structures within the SRA. The revenue collected from this fee is deposited in the SRA Fire Fund and generally used to support fire prevention activities within the SRA. Chapter 8 specifies that SRA fee revenue is available upon appropriation for three specific purposes: (1) fire prevention projects (includes projects authorized by the Board of Forestry and Fire Protection and grants to local agencies for projects), (2) inspections, and (3) mapping.

For 2013–14, the SRA fee is expected to generate about $90 million in revenue. Of this amount, the Governor’s budget proposes to allocate $73 million to: (1) support fire prevention activities within the SRA that were previously funded from the General Fund ($46 million) and (2) for state costs to collect and implement the SRA fee ($14 million). The proposed budget also includes two proposals to allocate $12.9 million from the fee for specific programs at CalFire. Below, we review and make recommendations on these two proposals.

Background. To provide fire protection in the SRA, CalFire engages in various activities to address fire severity, treatment, education, prevention, and planning (STEPP). For example, CalFire’s vegetation management program is a cost–sharing program between CalFire and local landowners that reduces the fuel that can potentially start fires by clearing brush, creating fuel breaks, and prescribed burns. The department also enforces defensible space requirements for structures within the SRA to reduce structural fire risks.

Chapter 311, Statutes of 2012 (SB 1241, Kehoe), requires local agencies to address fire risks in SRAs and very high fire hazard severity zones (VHFHSZ) in the safety element of their general plan by identifying available fire protection and suppression services. About 10 percent of the VHFHSZ are located in local responsibility areas, in which local agencies are responsible for fire prevention and protection. The remaining zones are located in SRAs.

Governor’s Proposal. The Governor’s budget proposes $11.2 million from the SRA Fire Fund to support 65.1 positions at CalFire, in order to perform STEPP activities and implement the provisions of Chapter 311. The budget also includes $513,000 to support six contracts with local agencies for fire prevention and protection activities. The 65.1 positions requested include:

- 14 permanent positions to, among other things, update SRA and VHFHSZ maps and assist local agencies in developing their general plan safety elements.

- 27.5 permanent positions to expand CalFire’s vegetation management program.

- 23.6 part–time positions to perform defensible space inspections.

Under the Governor’s plan, some of the requested funding and positions would be used to support activities outside of the SRA—specifically, lands adjacent to the SRA. As a result, the Governor also proposes budget trailer legislation to change the SRA fee into a tax, thereby allowing SRA fee revenue to be used in lands adjacent to an SRA.

SRA Fee Must Be Approved as a Tax to Fund Some of the Governor’s Proposal. Based on our analysis of the proposal and Chapter 8, if the proposed trailer bill is not approved with a two–thirds vote and the SRA fee is not converted into a tax, there would be serious legal concerns whether certain aspects of the Governor’s proposal could be legally funded with the SRA fee, specifically:

- One forester to develop forestry board policies related to local agencies’ general plan safety elements.

- Two battalion chiefs and eight fire captains to work with local agencies in their development of general plan safety elements.

- One forestry and fire protection administrator to oversee a statewide reporting database for local agencies’ general plans.

In addition, many of the proposed activities would benefit both the SRA and VHFHSZ. We estimate that there is about a 90 percent overlap in these jurisdictions. Therefore, if the SRA fee is not authorized as a tax (as proposed by the Governor), potentially only 90 percent of the following positions and activities could be legally funded with the SRA fee.

- One research program specialist and one research analyst for mapping activities.

- $500,000 to fund a contract to update vegetation and fuel maps.

- $439,000 in 2013–14 to develop web applications for general plan tracking, vegetation updates, and wildfire fuel updates.

Positions for Vegetation Management Program Lack Justification. Our analysis finds that the requested positions and activities are generally justified on a workload basis, particularly in regards to the implementation of Chapter 311. We are, however, concerned with the 27.5 positions proposed for the vegetation management program. This is because, at the time of this report, the department has not provided adequate justification to fully support the requested positions.

LAO Recommendation. Accordingly, we withhold recommendation for the 27.5 positions to expand CalFire’s vegetation management program pending the receipt of additional information.

Background. The civil cost recovery program within CalFire seeks to recover the costs of state fire suppression activities and related costs from anyone who starts a fire through negligent or unlawful actions. The program has been in place for many years and has resulted in net recoveries to the state’s General Fund in the millions of dollars annually. As part of the 2011–12 budget, CalFire received an additional ten positions on a two–year limited–term basis to increase the amount of civil costs recovered. Historically, activities related to the civil cost recovery program, including the additional ten limited–term positions, have been funded from the General Fund.

Governor’s Proposal. The Governor’s budget for 2013–14 requests permanent position authority for the ten positions initially provided in 2011–12 for the civil cost recovery program. The Governor proposes $1.7 million from the SRA Fire Fund to support these positions.

LAO Recommendations. The civil cost recovery program has been successful and has resulted in returning millions of dollars to the state’s General Fund. We recommend the Legislature approve the ten positions requested on a permanent basis to further these efforts. However, based on an opinion from Legislative Counsel, using SRA Fire Funds for this purpose is not legally permissible unless legislation is passed to change the SRA fee into a tax. This is because civil cost recovery–related activities are not specified in Chapter 8 as a permissible use. While the civil cost recovery program’s existence may deter future negligent behavior, thus reducing some fire risk, the program is not directly related to fire prevention and it is not limited to recovery within the SRA. Therefore, unless legislation is enacted changing the nature of the SRA charge, we recommend the Legislature fund these positions from the General Fund.

The DPR acquires, develops, and manages the natural, cultural, and recreational resources in the state park system and the off–highway vehicle trail system. In addition, the department administers state and federal grants to local entities that help provide parks and open–space areas throughout the state.

Background. The Border Fields State Park is on the Mexico border and includes the Tijuana Estuary—a significant wetland habitat—that runs through Mexico into the state park. In 2005, DPR constructed the Goat Canyon Sediment Basins in the park to help protect the estuary from the flow of water that washes in sediment and trash from Mexico. The basins, which are maintained by DPR, must be cleaned of the trash and maintained to comply with the California Environmental Quality Act and clean water regulations. In the past, such maintenance costs were funded by CalRecycle, as well as grants and donations from special interest groups. However, DPR indicates that these funding sources are no longer available to support such costs.

The DPR is part of the California–Mexico Border Relations Council’s Tijuana River Valley Recovery Team, which is a collaborative effort to keep the Tijuana watershed area free of trash and sediment. The team includes other state agencies and departments (such as CalEPA and the Department of Public Health), the federal and Mexican governments, and local and regional agencies. The team has historically relied on funding from various members to protect this area, in addition to federal grants. One of the challenges to securing ongoing funding is that there currently is no mechanism for seeking damages for environmental pollution from Mexico.

Funds Requested to Support Goat Canyon Park Clean–up. The Governor’s budget for 2013–14 requests $1 million annually from SPRF to support ongoing maintenance and clean–up at the Goat Canyon Sediment Basins at the Border Fields State Park. The SPRF is primarily funded by fee revenues and used to support the operations of the state park system.

Direct Department to Explore Other Funding Options. Last year, the state parks system faced serious funding challenges and the Legislature had to consider options to prevent the closure of up to 70 state parks. Since SPRF is one of the primary funding sources for park operations and maintenance, using these funds on an ongoing basis for clean–up activities (as proposed by the Governor) could put other parks in the system at risk of closure due to a lack of funding for operations. Moreover, DPR is not responsible for the accumulation of trash in the Border Fields State Park, and therefore the SPRF should not be the sole source of funding for the maintenance of the basins. Thus, we recommend that DPR present at budget committee hearings this spring an alternative proposal that includes funding from a variety of sources (such as other members of the Tijuana River Valley Recovery Team) for maintenance of the basins. In addition, the Legislature could pursue federal options to recover costs from Mexico, since Mexico is primarily responsible for the sediment and waste that flows into the park. Pending the additional information from DPR, we withhold recommendation on the Governor’s proposal to use $1 million from the SPRF to maintain the Goat Canyon Basins.

The DWR protects and manages California’s water resources. In this capacity, the department plans the development of the state’s water supplies and operates the SWP, which is the nation’s largest state–built water storage and conveyance system. The department also maintains public safety and prevents damage through flood control operations and supervision of dams.

Background. The IRWM program within DWR is an effort to encourage disparate water interests to share ideas on ways to improve all aspects of water management and develop projects that provide multiple benefits. Under the IRWM program, DWR competitively awards both planning grants to help organizations develop IRWM plans and implementation grants to construct specific projects. For example, through this program DWR funded a project in the Bay Area intended to improve water quality and reduce flooding by improving stormwater management.

The Water Security, Clean Drinking Water, Coastal and Beach Protection Act of 2002 (Proposition 50) established the IRWM program and allocated $250 million to DWR and $250 million to SWRCB. Proposition 84, approved by voters in 2006, allocated an additional $1 billion to DWR to support additional IRWM grants. The DWR has awarded all of the Proposition 50 funds allocated for planning and implementation grants and is currently soliciting applications for the second round of Proposition 84 implementation grants. (We note that some Proposition 50 funds for administrative purposes have currently not been allocated.) The department expects to award $131 million in Proposition 84 funds for the second round of grants in late 2013. Afterwards, DWR intends to begin the process for making a third round of grants. These particular grant awards are anticipated to be made in 2014–15.

Bond Funding for Grants and Program Administration Requested. The Governor’s budget for 2013–14 requests the following for the IRWM program:

- $472.5 million in Proposition 84 funds for the third round of grant funding, exclusively for implementation grants.

- $6 million in Proposition 84 funds over four years to fund existing positions to develop specific guidelines, solicit proposals, review technical details of IRWM plans and proposals, and manage award contracts.

- $1.5 million in Proposition 50 funds over three years to fund existing positions to evaluate project performance and continue oversight of the outstanding awards.

Deny Request For Grant Funding. We recommend that the Legislature deny the Governor’s proposal to provide $472.5 million in Proposition 84 funds for additional implementation grants. The requested funding is unnecessary in 2013–14 because DWR does not plan to award any of these implementation grants until 2014–15. However, we recognize the need to develop guidelines and review applications in the budget year. Therefore, we recommend approving the $7.5 million requested to support the positions that will manage the program.

Background. Lake Perris is a reservoir at the southern end of the SWP, which stores water for delivery to urban users in the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California, Coachella Valley Water District, and the Desert Water Agency. In addition, Lake Perris is a state park with roughly 600,000 visitors each year. In 2005, DWR identified potential seismic safety risks in a section of the foundation of Perris Dam and subsequently lowered the water level at the lake to ensure public safety. However, DWR indicates that the lake cannot remain at this lower level indefinitely because it is needed as an emergency supply storage facility for the SWP and serves as an important recreation area.

Proposal for Dam Remediation. The DWR proposes to remediate the dam and return the lake to its historical operating level. The estimated total cost of this project is $287 million, with the cost being split between the water agencies that contract with DWR to receive water from the SWP (contractors) and the state. The state’s share of costs is based on Chapter 867, Statutes of 1961 (AB 261, Davis)—the Davis–Dolwig Act—which states that the contractors should not be charged for the costs incurred to enhance fish and wildlife or provide recreation on the SWP (Davis–Dolwig costs). (We have previously raised concerns about DWR’s methodology for calculating Davis–Dolwig costs, such as in our 2009 report,

Funding Recreation at the State Water Project.) A recent recalculation of Davis–Dolwig costs by DWR determined the state’s share of Lake Perris repair costs would be about one–third of the total estimated cost, which amounts to $92 million.

The Governor’s budget for 2013–14 includes funding to begin the remediation of the Perris Dam as proposed by DWR. Specifically, the budget proposes $11.3 million from Proposition 84 for DWR to fund 11 existing positions and various costs, such as for final design, real property acquisitions, and environmental fees. The remaining state cost of $80 million would be partially supported by $27 million from Proposition 84 upon appropriation by the Legislature.

Proposed Project Raises Concerns. In reviewing the proposed project and funding requests, we have identified three primary concerns that merit legislative consideration. Specifically, we find:

- Project Costs Uncertain. The cost estimate cited by DWR for the project in the budget proposal is roughly $200 million lower than a previous study commissioned by the department in 2006, which estimated a total project cost of $488 million. However, the department has not been able to explain what specific factors account for this significant difference in cost. Thus, the actual cost of the project is unclear at this time. If the cost ends up being much closer to the previous estimate, the state’s share of the cost would be greater—$157 million.

- Funding Source for State Share Not Fully Identified. As indicated above, DWR proposes to use Proposition 84 funds to support $38 million of the total estimated state cost of $92 million. At this time, DWR has not identified a funding source for the remainder of the state’s share of the project costs. The administration plans to submit a proposal to fund the remaining state costs prior to spring budget hearings. In the past, the General Fund or other state funds (such as tidelands oil revenues) have been used to pay Davis–Dolwig costs.