March 10, 2009

2009-10 Budget Analysis Series

Federal Economic Stimulus Package:

Fiscal Effect on California

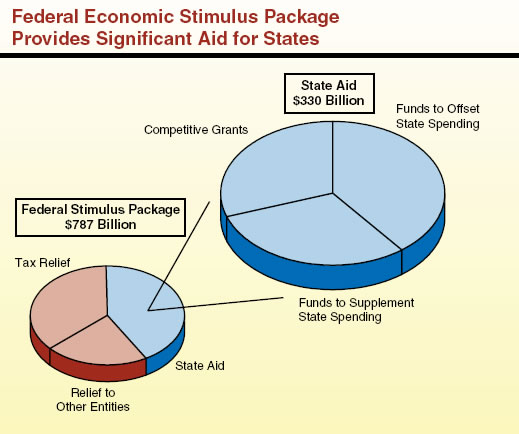

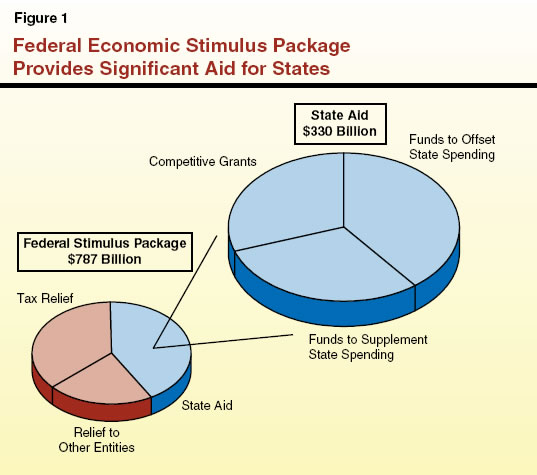

The recently enacted federal economic stimulus package—titled the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA)—commits a total of $787 billion nationwide. As reflected in the figure below, this funding provides: (1) $330 billion in aid to the states, (2) about $170 billion for various federal projects and assistance for other non–state programs, and (3) $287 billion for tax relief.

This report focuses on the state aid component of the stimulus package, as it consists of the federal dollars with which the Legislature will be most involved. As the figure shows, the state aid “pie” also consists of three pieces: (1) federal dollars that can be used to address budget shortfalls, (2) funds that supplement existing state spending, and (3) competitive grants. We estimate that California will receive over $31 billion from the first two components (see table below) and billions more in competitive grants.

The State “Trigger”

A significant portion of the $31 billion in aid to California will be available to address the state’s budgetary problems. We estimate that, based on the enacted state 2009–10 budget, California can use $10.4 billion in new federal dollars for this purpose over the life of ARRA. Of that amount, $8 billion would be available in 2008–09 and 2009–10. The Director of Finance and State Treasurer will determine their own estimate of the latter amount by April 1 of this year. If the amount is less than $10 billion, then annual state program reductions of nearly $1 billion and revenue increases of about $1.8 billion adopted as part of the 2009–10 budget package will go into effect.

Given the state’s continuing economic struggles, however, it is possible that state revenues (and the Proposition 98 minimum funding level) may continue to fall. In that case, it may be possible to use additional federal education dollars for budgetary relief.

Key Considerations for the Legislature

The Legislature will need to take many actions in the coming months to ensure that the funds are used in ways that meet its priorities and preferences. To assist in this process, we offer the following considerations in making decisions regarding these new federal funds:

- Maximize the Benefit of Federal Funds to the General Fund Budget. In this report, we make specific recommendations about how to help the state’s budgetary situation under different scenarios.

- Recognize the Short–Term Nature of New Federal Funds. Most of the state aid coming to California is intended to supplement current state spending. There is the risk, however, that the higher levels of service provided by the federal dollars will create ongoing expectations of state support once the funding expires. We offer strategies to address this risk.

- Act Quickly in a Handful of Cases. In certain instances, the state will need to act rapidly to ensure it receives the maximum amount of relief or to use the funds in the most effective way possible. Addressing a Medi–Cal eligibility issue and providing direction on the use of transportation funds are two such examples.

- Use Next Few Months to Oversee Implementation of New Federal Spending. For most of the new federal dollars and programs, the Legislature will have more time to take necessary actions. For example, the Legislature can use its budget process to monitor the state’s revenue picture and take whatever actions are needed to use federal dollars to keep the 2009–10 budget in balance. Similarly, the Legislature can use policy and budget subcommittee hearings to craft needed legislation, specify its wishes as to how new dollars are to be spent and oversee the administration’s plans with regards to the new funds.

California Will Receive Over $31 Billion in State Aid |

(In Millions) |

Program Area |

Federal Fiscal Year |

Totals |

2008-09 |

2009-10 |

2010-11 |

Health |

$3,986 |

$4,026 |

$1,024 |

$9,036 |

Education |

— |

7,973 |

— |

7,973 |

Labor and workforce development |

3,498 |

2,420 |

79 |

5,997 |

Social Services |

1,500 |

1,441 |

577 |

3,518 |

Transportation |

1,302 |

1,302 |

— |

2,604 |

General purpose fiscal stabilization |

— |

1,100 |

— |

1,100 |

Resources/environmental |

597 |

— |

— |

597 |

Housing programs |

381 |

— |

— |

381 |

Criminal justice |

264 |

— |

— |

264 |

Other |

27 |

— |

— |

27 |

Totalsa |

$11,555 |

$18,262 |

$1,680 |

$31,497 |

|

a Does not include significant additional federal funds the state is likely to receive from competitive grants. |

On February 17, 2009, President Obama signed into law the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) of 2009, H.R. 1. The spending and tax–cut plan is intended to help stabilize state budgets and spur economic growth. The stimulus package commits a total of $787 billion nationwide, and it will have a significant fiscal impact on California.

One–Third of the Federal Funding Is for State Aid

Figure 1 shows how ARRA funding falls into three main categories. The stimulus package provides about $330 billion in federal funds in aid to states. A variety of tax provisions intended to boost the economy will cost the U.S. Treasury $287 billion more. Finally, about $170 billion is available to be spent by federal agencies on federal projects or for other non–state programs, such as direct grants to local entities.

State Aid Comes in a Variety of Forms

Of the roughly $330 billion in aid available nationwide for states:

- Almost $100 billion is available to supplant or offset states’ general fund spending.

- As much as $130 billion will be available to states to supplement or increase state spending on a wide variety of programs.

- States and other entities (such as local governments) will also be able to apply for up to $100 billion in competitive or discretionary grants.

All of the funding for state relief is provided on a temporary basis and generally will be only available for the next few years.

California Will Receive a Significant Amount of Additional Federal Funds

Of the $330 billion available under ARRA nationwide for state aid, we estimate that California will receive approximately $31 billion in additional federal funds during the current and the next two federal fiscal years (FFYs). As Figure 2 shows, the state’s health programs will receive the largest share of these federal funds, about $9 billion, and education–related programs will receive nearly $8 billion in additional federal funds. These programs are followed by labor and workforce development and social services programs, which will receive about $6 billion and $3.5 billion, respectively.

Figure 2

California Will Receive Over $31 Billion in State Aid |

(In Millions) |

Program Area |

Federal Fiscal Year |

Totals |

2008-09 |

2009-10 |

2010-11 |

Health |

$3,986 |

$4,026 |

$1,024 |

$9,036 |

Education |

— |

7,973 |

— |

7,973 |

Labor and workforce development |

3,498 |

2,420 |

79 |

5,997 |

Social Services |

1,500 |

1,441 |

577 |

3,518 |

Transportation |

1,302 |

1,302 |

— |

2,604 |

General purpose fiscal stabilization |

— |

1,100 |

— |

1,100 |

Resources/environmental |

597 |

— |

— |

597 |

Housing programs |

381 |

— |

— |

381 |

Criminal justice |

264 |

— |

— |

264 |

Other |

27 |

— |

— |

27 |

Totalsa |

$11,555 |

$18,262 |

$1,680 |

$31,497 |

|

a Does not include significant additional federal funds the state is likely to receive from competitive grants. |

In some of the program areas, the year–by–year flows of funds are estimates and may occur differently than depicted in Figure 2. In addition, this figure does not capture the unknown, but potentially significant additional federal funds that the state is likely to receive when it applies for competitive grant funding included in ARRA. Finally, given the complexity of this legislation, our estimates of the state’s allocations included in this report should be considered preliminary and subject to revision as more information becomes available.

Some Federal Funds Are Available To Offset General Fund Spending

2009–10 Budget Package Is Linked to Federal Fiscal Relief. The Governor signed the 2009–10 Budget Act and related legislation on February 20, 2009, to address the state’s projected $40 billion shortfall. Based on the administration’s estimates, the act assumes that the state will receive $8 billion in federal stimulus funds to offset General Fund expenditures. The Governor vetoed an additional $510 million from the universities’ budgets in anticipation that even more fiscal relief would be available to backfill that reduction.

LAO Estimates of Offsets Under Budget Package. Our estimates of federal funds that can offset General Fund costs under the 2009–10 budget package are similar to the administration’s. As Figure 3 shows, we project that state spending would be reduced by almost $8 billion through 2009–10, with an additional $2.4 billion in offsets in 2010–11.

Figure 3

Stimulus Funds Potentially Available to Offset General Fund Expenditures |

Based on Enacted Budget Package

(In Millions) |

|

State Fiscal Year |

2008-09 and

2009-10

Combined |

|

Program Area/Provision |

2008‑09 |

2009‑10 |

2010‑11 |

All Years |

General Purpose |

|

|

|

|

|

State Fiscal Stabilization Fund |

— |

$1,100 |

— |

$1,100 |

$1,100 |

Health |

|

|

|

|

|

Medi-Cal-related programs |

$2,631 |

$3,740 |

$1,957 |

$6,371 |

$8,328 |

Early Start program |

— |

53 |

— |

53 |

53 |

Labor and Workforce Development |

|

|

|

|

|

Workforce Investment Act discretionary funds |

— |

$37 |

$37 |

$37 |

$74 |

Unemployment Insurance—interest relief |

— |

30 |

209 |

30 |

239 |

Social Services |

|

|

|

|

|

CalWORKs Emergency Fund |

$40 |

$200 |

$190 |

$240 |

$430 |

Foster Care and Adoption Assistance programs |

33 |

45 |

24 |

78 |

102 |

Department of Child Support Services |

22 |

30 |

7 |

52 |

59 |

Totalsa |

$2,726 |

$5,235 |

$2,424 |

$7,961 |

$10,385 |

|

a The General Fund impact of the education American Recovery and Reinvestment Act funds is addressed later in this report. |

These amounts capture offsets in General Fund expenditures that occur “on the natural” or with the state making relatively minimal changes to existing programs to receive the funds. For example, the single greatest source of relief comes from the increase in the percentage of program costs funded by the federal government for the state’s Medicaid program, known as Medi–Cal in California. This source of funding and the others shown in Figure 3 are discussed in more detail later in this report.

Federal Stimulus and the State Trigger

The budget package requires the State Treasurer and the Director of Finance to determine by April 1, 2009 if ARRA makes available by June 30, 2010 additional federal funds that may be used to offset at least $10 billion in General Fund expenditures. If they determine that federal fiscal relief reaches that $10 billion threshold, then nearly $1 billion in cuts to various programs and a 0.125 percentage point increase in personal income tax rates included in the budget package would trigger off—that is, not go into effect.

Language Open to Interpretation. The language in the 2009–10 Budget Act describing what needs to happen in order for the trigger to be reached is somewhat open to interpretation. For example, the language states that the federal legislation must “make available” by June 30, 2010, federal funds “that may be used” to offset $10 billion in General Fund expenditures. This wording raises such questions as whether $10 billion must actually be used to offset state General Fund costs, or whether this requirement would be satisfied if funds of this amount were identified that theoretically could be used in this way.

Our estimate of $8 billion in federal funds being available to offset General Fund expenditures, shown in Figure 3, excludes offsets the state might achieve from education–related federal funds. This is because our estimate is based on the level of state revenues assumed in the 2009–10 Budget Act and the corresponding level of support provided for state education programs. The state’s continuing economic struggles, however, suggest that revenues (and the Proposition 98 minimum guarantee) may continue to fall. Under such a scenario, it may be possible to use additional federal education funding to offset a greater amount of General Fund spending for state education programs, as we discuss in the “Education” section of this report. Ultimately, the interpretation of this provision of statute is a matter for the Director of Finance and the State Treasurer to decide. The administration has indicated that its preliminary conclusion is that the available federal funds will be insufficient to avoid the tax increase and cuts contained in the February budget package.

As noted earlier, the federal economic stimulus package will provide about $31 billion in additional federal dollars directly to the state for a wide array of programs. In response, the Legislature will need to take many actions in the coming months to ensure that the funds are used in ways that meet its priorities and preferences. To assist in that process, we discuss below some key considerations in making decisions regarding these new federal funds.

Maximize the Benefit of Federal Funds on the General Fund Budget. Given both the deteriorating economic situation and the gloomy out–year state budget forecast, we believe the Legislature must maximize the use of stimulus dollars to offset General Fund expenditures. In this report, we make specific recommendations about how to do so. Some federal dollars may only be available for General Fund relief in certain situations (such as certain education funds if state revenues decline further).

Recognize the Short–Term Nature of New Federal Funds. Most of the state aid coming to California is intended to supplement current state spending. There is the risk, however, that the higher levels of service provided by the federal dollars will create ongoing expectations of state support once the funding expires. There are ways to limit this risk:

- The Legislature should dedicate this limited–term federal assistance as much as possible to limited–term purposes. For instance, we recommend using some of the education funds to pay for one–time mandate costs and data systems development.

- For ongoing programs receiving supplemental funding, the Legislature could spread out dollars over three years (instead of one or two), thereby reducing the level of new spending. In addition, the Legislature could make explicit that the supplemental funding is in effect only for the duration of the added federal funds.

- The Legislature could also use the near term to explore and implement program reforms that often take several years to achieve savings. For example, the Legislature could expand “pay for performance” programs that provide fiscal incentives for Medi–Cal providers that could ultimately save tens of millions of dollars annually. By starting now, the state would be more likely to have in place programmatic savings that could offset the loss of supplemental federal funds in the out–years.

Act Quickly in a Handful of Cases. In certain instances, the state will need to act rapidly to ensure it receives the maximum amount of relief or to use the funds in the most effective way possible. We have identified the following situations where quick action is needed:

- To receive major new federal funding for the Medi–Cal Program, California must make a change in state law regarding eligibility by July 1, 2009.

- The Legislature should provide direction on its preferred approach to distributing new federal dollars for transportation and input on the federal government’s plans regarding the allocation of high–speed rail funds.

- To fully access state clean waters monies, legislation must authorize specific types of financial assistance.

Use Next Few Months to Oversee Implementation of New Federal Spending. For most of the new federal dollars and programs, the Legislature will have more time to take necessary actions. For example, the Legislature can use its budgetary process to monitor the state’s revenue picture and take whatever actions are needed to use federal dollars in keeping the 2009–10 budget in balance. Similarly, the Legislature can use policy and budget subcommittee hearings to:

- Address any needed legislation related to the use of new federal dollars.

- Oversee departments’ plans and efforts in applying for competitive grants and spending supplemental funds.

- Ensure that the use of federal stimulus dollars is consistent with existing state policies.

- Provide any needed assistance to local governments regarding their use of new federal dollars.

Below, we describe by program the additional federal funding the state will be receiving and major issues for legislative consideration.

As Figure 4 shows, ARRA will provide California with almost $8 billion in state–administered education funding. The ARRA also allows the state to apply directly for billions of dollars in additional grants and subsidized bonds. In addition, ARRA offers the potential for California to benefit indirectly from billions more in competitive grants, tax credits, and subsidies to individuals, colleges, and local educational agencies (LEAs).

Figure 4

California to Receive Large Boost in Federal Funding for Education |

(In Millions) |

Program |

Funding |

Description |

State Fiscal Stabilization Fund |

|

|

Education |

$4,875a |

Generally mitigates K-12 and higher education cuts. |

State Incentive Grants |

—b |

Competitive program supports states that demonstrate need in certain

education areas (including teacher quality, student data systems, and

assessment systems) and presents innovative ways to address those needs. |

Subtotal |

($4,875) |

|

K-12 Education |

|

|

Title I |

$1,511c |

Supplemental services for low-income students and support for low-performing schools. |

Individuals With Disabilities Education Act |

1,268 |

Supplemental services for special education students. |

Child Care and Development Block Grant |

220 |

Approximately $28 million is earmarked for specific activities. The rest must supplement state funding for child care for low-income families. |

Enhancing Education Through Technology |

71 |

Classroom use of technology. Funds may be used for hardware, software,

infrastructure improvement, and professional development. |

McKinney-Vento Homeless Assistance |

18 |

School districts' efforts to educate homeless youth. |

Child Nutrition |

10 |

Assistance to high-need districts in purchasing meal-related equipment. |

Institute of Education Sciences Grant |

—b |

Competitive program to help state develop/expand a statewide longitudinal

student database. |

School Construction Subsidies |

—b |

Tax credit bonds for public school construction or repair. |

Qualified Zone Academy Bonds |

—b |

Interest-free tax credit bonds for qualified infrastructure efforts. |

Impact Aid |

—b |

Facility cost funding for districts with high percentages of students living on

federal land. |

Title V Innovation and Improvement |

—b |

Competitive program to help districts and states develop performance-based compensation systems for teachers and administrators. Funds do not pass through state. |

Subtotal |

($3,098) |

|

Total Education Funding |

$7,973 |

|

|

a An additional $1.1 billion is provided for other government services. |

b Total benefit for California is unknown at this time. |

c Consists of $1.1 billion in basic grants, $45 million in Program Improvement Grants, and $383 million in School Improvement Grants. |

Major Provisions

State Fiscal Stabilization Fund

Nationwide, ARRA provides $54 billion for state fiscal stabilization. Funding allocations are based on states’ school–age and total populations. The majority of stabilization funding will support education (82 percent), with the remainder set aside for other government services.

California Will Receive Almost $5 Billion to Support K–12 and Higher Education. According to the most recent U.S. Department of Education (USED) estimates, California will receive $4.9 billion in fiscal stabilization funds for K–12 and higher education. States must follow specific rules for distributing this funding between K–12 and higher education, as well as allocating funding within those sectors.

California Will Receive Additional $1 Billion for Other Government Services. The state also will receive almost $1.1 billion for “public safety and other government services.” This funding is relatively free of federal constraints. While funding does not need to be used for K–12 or higher education, the law specifically permits such uses, including school building modernization, renovation, and repair. The 2009–10 budget package assumes that these funds will be used to offset General Fund costs.

California Could Receive More Education Funding Through Competitive Grants. Of the $54 billion in ARRA stabilization funding nationwide, the act sets aside $5 billion for K–12 education incentive grants. The USED is to award these grants on a competitive basis. While LEAs will apply directly for some of these grants ($650 million nationwide), states will apply for the remainder ($4.4 billion nationwide). The portion going to states will be distributed according to their identified fiscal and program needs. At least 50 percent of the state money must be distributed to LEAs based on their Title 1 counts (number of low–income students).

Law Establishes Minimum Level of State Spending on Education. To receive fiscal stabilization funds, the state must maintain at least the same level of state support for K–12 and higher education as in 2005–06. If the state were to experience a “precipitous” decline in financial resources that threatens its ability to maintain sufficient state support, however, the U.S. Secretary of Education can waive or modify this requirement.

Funding Must First Be Used to Mitigate State Funding Cuts. Fiscal stabilization funds must first be used to mitigate state funding cuts for K–12 and higher education in 2009, 2010, and 2011. Funds for K–12 education must be allocated based on existing funding formulas, whereas states have discretion in how they allocate funds for higher education. If a federal award is greater than needed to reach 2008 or 2009 state funding levels (whichever is higher), then remaining funds are to be allocated to K–12 education based on schools’ Title I counts. If a federal award is less than needed to restore education funding to 2008 or 2009 levels, then funds must be allocated in proportion to the relative shortfalls that exist for K–12 and higher education.

K–12 Education

As Figure 4 shows, ARRA funds 11 targeted K–12 programs—with California expected to receive at least $3.1 billion, plus the opportunity to apply for various competitive grants The majority of available monies provide supplemental funding on top of existing base federal grants. The ARRA funding typically is intended to be used consistent with existing program rules. It also funds several one–time opportunities for state or local improvements to K–12 infrastructure and systems.

Title I. The ARRA provides California with a $1.5 billion augmentation to the existing Title I program to support supplemental services for low–income students. As a condition of receiving these funds, the California Department of Education (CDE) must provide the USED with information on the current per–pupil distribution of state and local funds.

- Formula Grants. The bulk of the Title I money ($1.1 billion) is to be allocated using certain formulas that are based largely on LEAs’ concentration of low–income students. Schools must use funds to target services to low–income students who are not meeting or are in danger of not meeting academic proficiency standards. If more than 40 percent of students at a school are low–income, then the school may run a “schoolwide” program, in which funding may be used for the benefit of all students rather than targeting only specific at–risk students. Of the $1.1 billion, the state must set–aside 4 percent, or $45 million, to support LEAs and schools in Program Improvement or PI. (LEAs and schools enter PI when they have failed to meet federal performance targets for two consecutive years.) Funding may be used for general LEA and school improvement activities.

- School Improvement Grant (SIG).

The remaining funds ($383 million) would be provided through a SIG, which is somewhat more restrictive. The SIG funding can only fund LEAs with schools in PI for specific school–level improvement activities. The SIG rules also specify minimum and maximum grants of $50,000 and $500,000, respectively, per PI school, but states can decide how to prioritize SIG funding among PI schools.

Special Education Funding. The ARRA provides a $1.3 billion augmentation in Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) funding for special education. Of this amount, $1.2 billion is for K–12 education and $41 million is for preschool. Consistent with IDEA, funding must be used to ensure that special education students receive a free and appropriate education as determined by their individualized education programs. Also consistent with IDEA, LEAs may use up to 50 percent of any year–over–year increase in IDEA monies to reduce their local maintenance–of–effort (MOE) requirement. Local savings resulting from a MOE reduction must be used for federal education priorities.

Child Care and Development Block Grant (CCDBG). The ARRA provides California $220 million to supplement state funding for child care for low–income families. These CCDBG funds are intended to allow the state to provide care to more children than otherwise would have been possible. Allowable uses include funding more child care slots, reducing family fees for child care, supplementing provider fees, lowering eligibility requirements to enable more families to use services, and professional development and recruitment of providers. Funds may not be used to construct facilities. Of the total funding, we estimate about $28 million must be used to improve the quality and availability of child care, including $10 million to improve the quality of infant and toddler care.

Enhancing Education Through Technology (EETT). The ARRA provides California $71 million for supplemental support of the existing EETT program. Generally, EETT funds are intended to improve the use of technology in the classroom. Funds may be used to purchase hardware or software, undertake professional development, and support instructional technology staff and services at the local level.

McKinney–Vento Homeless Assistance. The ARRA provides California $18 million for supplemental support of the existing McKinney–Vento Homeless Assistance program. Generally, these funds are intended to help districts improve the enrollment, attendance, and success in school of homeless children.

Child Nutrition Equipment. The ARRA provides California $9.7 million for National School Lunch Program equipment assistance (a new one–time funding grant). The CDE is required to allocate these funds to LEAs through a competitive process based upon need for equipment assistance. Priority is to be given to schools with at least 50 percent of the student population eligible for free or reduced price meals.

Student Longitudinal Data System Grants. The ARRA includes $250 million nationwide for competitive grants from the Institute of Education Sciences (IES) to support the development of statewide student longitudinal data systems that include postsecondary education and workforce information. Up to $5 million of the funds nationally may be used for state data coordinators and for awards to public or private organizations to improve data coordination. Presumably, these grants will be similar to previous IES grants such as the one California used for the development of the California Longitudinal Pupil Achievement Data System (CALPADS).

New Subsidized School Construction Bonds. The ARRA includes $22 billion nationwide for a new type of subsidy for school construction bonds issued in calendar years 2009 and 2010. These bonds may be issued by state or local governments for (1) construction, rehabilitation, or repair of public school facilities; or (2) the acquisition of land on which a public school will be constructed. The amount of new bonds that states (including local governments within the state) can issue is based upon the number of children living below the poverty line in each state. Based on this criterion, California could issue about $3 billion in subsidized bonds. (A portion of this amount is reserved for large school districts to issue bonds directly.)

Qualified Zone Academy Bond. The ARRA provides a $1.4 billion augmentation nationwide to the existing Qualified Zone Academy Bonds (QZAB) program. These subsidized bonds can be used to improve facilities or provide teacher training for school districts in certain high poverty areas. To participate, school districts must partner with a local business and develop an academic program that better prepares students for college or the workforce.

Impact Aid. The ARRA provides $100 million nationwide for supplemental support of the existing Impact Aid program. The ARRA requires that 40 percent of this funding be distributed via formula grants directly to eligible districts and 60 percent be available for competitive grants. Impact Aid monies are intended to fund facility costs for districts with high percentages of students living on military bases and Native American reservations.

New Teacher Performance–Based Compensation Grants. The ARRA provides $200 million nationwide for competitive grants intended to promote the development and implementation of performance–based compensation systems for teachers and administrators. States or districts with innovative program ideas in this area may apply for the grants.

Higher Education

The federal stimulus package funds five targeted higher education programs, which will provide benefits directly to California colleges or students. None of these programs require state administration.

Higher Education Tax Credits.

Under current law, the federal Hope tax credit reimburses eligible students for the enrollment fees they pay for college. The stimulus package replaces the Hope credit with the American Opportunity tax credit, which is larger and available to more students. Figure 5 summarizes these added features.

Figure 5

New Federal Tax Credit Expands Hope Credit |

Hope Credit (2008 Tax Year) |

American Opportunity Credit (2009, 2010) |

• Directly reduces tax bill. |

• Directly reduces tax bill and/or provides partial tax refund to students without sufficient income tax liability. |

• Covers 100 percent of the first $1,200 in tuition payments.

Covers 50 percent of the second $1,200 (for maximum tax credit of $1,800). |

• Covers 100 percent of the first $2,000 in tuition payments and textbook costs. Covers 25 percent of the second $2,000 (for maximum tax credit of $2,500). |

• Designed for students who:

—Are in first or second year of college.

—Attend at least half time.

—Are attempting to transfer or acquire a certificate or degree. |

• Designed for students who:

—Are in first through fourth year of college.

—Attend at least half time.

—Are attempting to transfer or acquire a certificate or degree. |

• Provides full benefits at adjusted income of up to $96,000 for married filers ($48,000 for single filers) and provides partial benefit at adjusted income of up to $116,000 ($58,000 for single filers). |

• Provides full benefits at adjusted income of up to $160,000 for married filers ($80,000 for single filers) and provides partial benefit at adjusted income of up to $180,000 ($90,000 for single filers). |

Pell Grants. The federal Pell Grant program provides grants to low–income undergraduate students to help them with the costs of attending college. The ARRA increases the maximum Pell Grant from $4,731 in 2008–09 to $5,350 in 2009–10, and expands eligibility for the program. We anticipate that students at California public colleges and universities, including community colleges, will receive about $500 million in additional Pell Grant funds in 2009–10.

Other Programs. Under ARRA, California universities are eligible for hundreds of millions of dollars in competitive grants for scientific research. Public and private colleges and universities in the state will receive an estimated $21 million in additional federal work–study funds in 2009–10. Changes to the rules for Section 529 college savings plans will allow students to count computer equipment and technology and services, including Internet access, as qualified higher education expenses in 2009 and 2010. Additional teacher quality grants and Public Health Service Corps training funds for health care providers will benefit California higher education students and institutions. As we discuss in the “Labor and Workforce Development” section of this report, the federal economic stimulus package directs funds to workforce investment boards for job training purposes. It is likely that community colleges and adult education programs will receive a portion of these funds to carry out such activities.

Issues for Legislative Consideration

In this section, we discuss various opportunities the state has for using federal education funds to achieve General Fund relief. We also describe several other opportunities the state has for maximizing the benefit of these funds—for example, by using them to restore reductions made in the 2009–10 Budget Act, mitigate deeper reductions in 2010–11 or 2011–12, or bolster existing state education initiatives.

Using Federal Funds to Offset State Education Expenditures

The 2009–10 budget package was premised on the use of only $510 million of education federal stimulus funds to offset state costs. If the Proposition 98 minimum guarantee were to drop from the enacted level due to declining revenues, however, the state could be in the position to use billions more in federal funds for budgetary solutions. This is due to the way that the stabilization requirements are structured. As shown in Figure 6, we identify almost $7 billion in potential offsets to state education spending across the next three years assuming more pessimistic state revenues. Of this amount, approximately $3.5 billion could be achieved in 2009–10 (or $3 billion more than the current budget). In addition to the options listed in the figure, the state has an opportunity to reduce significantly its existing special education mandate obligations.

Figure 6

Potential Federal Offsets to State General Fund

Education Expenditures |

(In Millions) |

|

State Fiscal Year |

|

Program |

2009‑10 |

2010‑11 |

2011‑12 |

Totals |

Education Stabilization Funds |

$3,321 |

$1,554 |

— |

$4,875 |

Title I, Basic Grants |

— |

946 |

$182 |

1,128 |

Title I, School Improvement Grants |

— |

192 |

192 |

383 |

Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), state special schools |

85 |

85 |

85 |

256 |

IDEA, residential placements |

59 |

65 |

72 |

196 |

Totals |

$3,466 |

$2,842 |

$531 |

$6,838 |

Use Education Stabilization Funding to Maximize General Fund Relief. California appears to have options for using most, if not all, education stabilization funding for state General Fund relief. The exact timing of such relief, however, would depend on several factors, including the interpretation of various formulas in the federal law and the final determination of the 2009–10 Proposition 98 minimum guarantee. For example, if revenues fell substantially below the level assumed in the budget, California could use more than $3 billion in federal stabilization funding to offset 2009–10 state education expenditures and avoid having to make deeper cuts to education programs. In this case, approximately $1.5 billion in stabilization funding would remain available to aid the state in 2010–11.

Options for Using Other Federal Funds. If revenues were to deteriorate further, the state has additional options to achieve state General Fund relief by substituting federal funds for General Fund spending. Under this approach, programs would receive the same total amount of funding envisioned in the enacted 2009–10 budget, but more federal and less state funding would be used. These options include:

- Title I/Economic Impact Aid (EIA). The state EIA program provides funding for supplemental services for educationally disadvantaged students and English Learners (EL). Because EIA is partly based on Title I counts (and Title I counts overlap significantly with EL counts, the other EIA factor), EIA is a natural candidate for such a funding swap. This option would result in up to $1.1 billion in General Fund (Proposition 98) savings spread across the next few years.

- Title I/Quality Education Investment Act (QEIA). The state QEIA provides funding to 487 schools for school improvement efforts. Given that the vast majority of these schools are in federal PI and are implementing specific school–level improvement strategies consistent with SIG rules, SIG funding could be used to fund QEIA. This option would provide the state with up to $383 million in General Fund (non–Proposition 98) savings spread across the next few years.

- IDEA/State Special Schools. The CDE operates three state special schools (the Fremont School for the Blind, the Fremont School for the Deaf, and the Riverside school for the Deaf) and three regional diagnostic centers (North, Central, and South). The state special schools and diagnostic centers are funded with Proposition 98 ($47 million) and non–Proposition 98 ($39 million) General Fund monies. The state could use IDEA funds to cover these costs over the next three years—resulting in total General Fund savings of $256 million ($140 million Proposition 98 and $116 million non–Proposition 98).

- IDEA/Residential Placement. The Department of Social Services covers residential costs for special education students who have been diagnosed with serious emotional disorders and require residential placement. The state covers a share of these costs. The state could use IDEA funds to cover these costs over the next three years—resulting in total General Fund savings of $196 million (non–Proposition 98).

Use IDEA Funding to Pay Retroactive Special Education Mandate Claims. In 1994, three school districts filed a claim with the Commission on State Mandates arguing that Chapter 959, Statutes of 1990 (AB 2586, Hughes), constituted a reimbursable mandate by regulating the types of behavioral interventions that could be used for special education students. The administration recently negotiated a settlement with districts. Under the terms of the settlement, districts would receive $520 million to cover retroactive claims. (Of this amount, $10 million would be paid in 2009–10, with the remainder paid in $85 million increments over the course of six years, beginning in the 2011–12 fiscal year.) We instead recommend using IDEA funding provided under ARRA to reimburse districts in 2009–10 for these retroactive claims in one lump sum. Under this approach, a dollar–for–dollar reduction in the state’s outstanding mandate obligations would be achieved.

Other Opportunities for Maximizing Benefit of Federal Education Funds

Several other opportunities exist for the state to maximize the benefit of federal education funds.

Apply for State Incentive Grant, Use to Support Certain Education Programs. As described above, the state will need to apply if it is to benefit from any of the $5 billion available nationwide for education incentive grants. While relatively little is known about the criteria that the U.S. Secretary of Education will use to evaluate grant proposals, federal law suggests grants must be used to improve academic achievement, especially at low–performing LEAs. Given this requirement, the state could use grant funds to restore some funding for certain education programs that were reduced in the 2009–10 Budget Act. For example, the budget reduces funding for alternative high schools, supplemental instruction related to failing the high school exit exam, EL programs, Foster Youth programs, state assessments, and an alternative teacher–training program. Incentive funding also might be reserved to mitigate future cuts in these areas.

Use Title I Set–Aside Funding to Benefit All Schools Serving Low–Income Students. Federal funding available to help low–income schools in need of academic improvement has exceeded identified program costs in recent years. As a result, the state has built up substantial carryover funding. Thus, we recommend using the additional $45 million in ARRA Title I set–aside funding to benefit all low–income students. To this end, we recommend allocating the additional funds using the basic Title I formulas, which would ensure funds are spread broadly across Title I schools. Title I regulations allow states to distribute set–aside funds in this manner when such funds are found to exceed PI needs.

Child Care and Development Block Grant. Due to the state budget situation, the 2009–10 Budget Act made various reductions to child care and development programs. The one–time increase in federal CCDBG funding comes with relatively restrictive rules requiring states to spend above existing levels. The funds, however, could be used to backfill cuts already made. Specifically, provider reimbursement rates, family fee rates, and/or the number of child care slots could be partly restored to prior–year levels. The $220 million in available CCDBG funding would be sufficient to sustain some of these restorations through 2010–11. The restorations could be specifically linked to the duration of the availability of the federal funds.

Enhancing Education Through Technology. In recent years, the Legislature has considered various proposals to provide funding to LEAs to prepare for implementation of CALPADS. The Legislature has recognized that while CALPADS will be of benefit both to the state and LEAs, the new system will require much work at the local level to collect and maintain reliable data. The limited–term federal EETT funding is an ideal source of funding for these activities. The EETT funding can be used for efforts to improve local infrastructure in preparation for CALPADS, train local staff on education data quality, and conduct various other related activities that generally will help prepare educators to use data and technology more effectively at the school–site level. In short, this one–time federal funding could offset the need for the state to provide additional funding for LEAs and/or allow for faster implementation of CALPADS.

Statewide Education Database Grant. California used a $3.2 million IES grant to help fund the development of CALPADS, which will be fully implemented in the 2009–10 school year. While CALPADS will significantly improve the state’s longitudinal student data system, it does not yet meet all of the federal criteria delineated for such systems. For example, recently enacted federal legislation requires such systems to include data from preschool through postsecondary education. CALPADS, however, currently is designed only to include K–12 student information. We recommend the state pursue additional IES funding to begin a CALPADS improvement project that would meet these federal requirements. (Such a project also could address California–specific issues highlighted in a recently released report, Framework for A Comprehensive Education Data System. This report, developed by McKinsey and Company at the request of CDE and the Governor, recommends a multi–phased approach for expanding CALPADS to include preschool and postsecondary data as well as undertaking additional improvements to maximize security and data quality.)

Federal Tax Credits to Increase College Funding. In the 2009–10 Budget Analysis Series: Higher Education, we noted that additional revenue could be raised through California Community Colleges (CCC) fees with minimal net effect on student costs. This is because financially needy students are exempt from fees, and most other students would be fully or partly reimbursed through federal tax credits. Because ARRA expands the size and availability of these tax credits, middle– and upper–income students would be even better protected from the effect of CCC fee increases. The Legislature, thus, could increase revenue received by community colleges through fees, while having only a minimal effect on college affordability. In effect, raising fees would be an effective strategy for leveraging more federal money for higher education.

In addition, the Legislature may wish to consider modifying the community college fee waiver program into a no–interest loan program for needy students who could fully repay the loan with federal tax reimbursements. This action would add hundreds of millions of dollars in CCC revenues each year—without affecting affordability.

Adjust Campus Financial Aid Funding for Increases in Pell Grants. Both University of California (UC) and California State University (CSU) employ campus–based financial aid grant programs to help their students pay their education costs. In general, the campus–based aid programs seek to cover those costs that the student is unable to meet through family contributions, loans, and grants (such as Cal Grants and the Pell Grant). Because the size of Pell Grants will be increasing under ARRA, this will reduce the amount of aid to be covered by campuses. As noted by the Governor, this has the effect of providing fiscal relief to the campuses. The Legislature may wish to take this fiscal relief into consideration as it determines the level of state funding needed to cover university operations.

One of the largest portions of federal fiscal relief to states will come in the form of an increased federal share of costs for state Medicaid programs (known as Medi–Cal in California). Below, we summarize and discuss the increased federal share and other key health–related components of ARRA.

Increased Federal Share of Funding for Medi–Cal

The federal government pays a certain percentage of the cost of each state’s Medicaid program. This percentage is known as the federal medical assistance percentage or FMAP. The ARRA temporarily increases the FMAP for all states retroactively to October 2008 and continuing through December 2010, subject to certain requirements and restrictions, which we discuss below. The ARRA provides a base FMAP increase of 6.2 percentage points for all states, plus additional increases determined by a formula that incorporates each state’s unemployment rate and current federal share.

Significant Funding for California. Based on recent employment data, California likely would qualify initially for the highest unemployment–based FMAP increase available under ARRA. Thus, our preliminary estimate is that Medi–Cal will receive an FMAP increase of 11.6 percentage points, equivalent to $10.1 billion in additional federal funds for the state through December 31, 2010. This amount will be distributed among several state departments that administer portions of the Medi–Cal Program, as well as to local governments, who also share in the cost of some Medi–Cal services. Figure 7 summarizes our estimates of state and local savings. The state portion of the federal funds, $8.3 billion, will reduce state General Fund costs over the period.

Figure 7

State and Local Savings From

Increase in Federal Share of Medi-Cal Costs |

(In Millions) |

|

2008‑09 |

2009‑10 |

2010‑11 |

Total |

State Departments |

|

|

|

|

Health care services |

$1,973 |

$2,838 |

$1,482 |

$6,293 |

Social services (IHSS) |

282 |

389 |

206 |

876 |

Developmental services |

234 |

313 |

163 |

710 |

Other departments |

143 |

200 |

106 |

449 |

Subtotals |

($2,631) |

($3,740) |

($1,957) |

($8,327) |

Other Entities |

|

|

|

|

Local government |

$305 |

$408 |

$203 |

$916 |

Public hospitalsa |

293 |

361 |

179 |

833 |

Subtotals |

($598) |

($769) |

($382) |

($1,749) |

Total Federal Fund Relief |

$3,229 |

$4,508 |

$2,339 |

$10,077 |

|

a Includes University of California hospitals. |

IHSS = In-Home Supportive Services. |

Requirements and Restrictions. In order to receive the enhanced FMAP, states must comply with certain requirements and restrictions. The most significant of these are the following:

- Eligibility. States may not receive the FMAP increase after July 1, 2009, unless they maintain eligibility levels and procedures that were in place as of July 1, 2008. The FMAP increase is not available for Medicaid eligibility expansions enacted after July 1, 2008 or for certain health programs that already receive enhanced federal matching funds.

- “Prompt Pay.” As of June 1, 2009, states are not eligible for the enhanced FMAP for days during which they do not meet federal prompt pay requirements. These requirements specify, among other provisions, that state Medicaid programs pay 90 percent of noninstitutional medical claims within 30 days. The ARRA would apply these provisions to nursing homes and hospitals as well.

- “Rainy Day Funds.” States may not use funds attributable to the increased FMAP as deposits into a rainy day fund or reserve.

State Currently Does Not Qualify for Enhanced FMAP. Based on our review of the ARRA provisions affecting Medicaid, California currently does not qualify for the FMAP increase due to a procedural change to Medi–Cal Program eligibility rules the state enacted as part of the 2008–09 Budget Act. This change required children to submit a midyear status report to confirm their continuing eligibility for Medi–Cal every six months, along with their parents, who were already required to submit this report. In order to receive the new federal funds, the state would need to reverse this policy prior to July 1, 2009. This reversal would result in additional General Fund costs to the state of $70 million in 2009–10 (as estimated at the enhanced FMAP rate). Based on our review and our discussions with the state Department of Health Care Services (DHCS), which administers Medi–Cal, the state currently meets all other ARRA requirements.

State Policy Change Needed to Access Increased Federal Funds. The federal government made increased FMAP funding available as of February 25, 2009 for six months of prior expenses. The department indicated in discussions that it will be ready to begin drawing down the additional funds as soon as mid–March. However, DHCS also reported that it must certify to the federal government that California has reversed its new midyear status report requirement before the state can access these funds. Therefore, we recommend that the Legislature enact legislation as soon as possible to reverse the children’s midyear reporting requirement.

Other Medicaid Provisions

In addition to the FMAP enhancement, the federal economic stimulus package includes other funding for state Medicaid programs that we discuss below. We summarize the major provisions in Figure 8. None of these provisions are likely to offset General Fund expenditures in the Medi–Cal Program, but some may increase state costs.

Figure 8

Other Key Medicaid Provisions in Federal Economic Stimulus Package |

Provision |

Fiscal Effects |

|

Nationwide |

California |

Health information technology |

$2 billion appropriated for grants, $15 billion estimated spending for Medicaid incentive payments, and $22 billion for Medicare incentives. |

Unknown. |

Disproportionate Share Hospital (DSH) funding |

Estimated $548 million. |

Direct increase of $54 million in federal DSH funds for public hospitals. Also

results in increase of $9 million

(General Fund) for other hospitals. |

Transitional Medi-Cal expansion |

Estimated $1.3 billion. |

Costs of $59 million (General Fund)

if California implements optional

expansion. |

Delay in various Medicaid

regulations |

Potential savings. |

Potential savings. |

Health Information Technology (HIT). The ARRA provides an estimated $15 billion nationwide over nine years to pay most of the costs to implement and administer electronic health records for qualifying Medicaid providers, such as children’s hospitals and physicians who serve a minimum percentage of Medicaid enrollees in their practice. Only technologies that meet certain standards will be eligible for funding, and the state would need to administer a HIT oversight program to ensure that providers receiving federal funds adhere to ARRA’s specified criteria.

The ARRA provides an estimated $22 billion nationwide over nine years for similar incentives in the federal Medicare program, and $2 billion for a variety of grants and other assistance to promote various health information technologies. The grant and other assistance programs require varying levels of nonfederal funding to draw down this federal assistance—in some cases as little as $1 of nonfederal funding for every $10 received from the federal government. These nonfederal shares could be provided by states or potentially by local governments or other entities. The federal grants will be awarded based on a competitive application process, and the details of the distribution are not yet established.

In our recent report, the 2009–10 Budget Analysis Series: Health (see "Health Information Technology"), we discuss how increasing the adoption of HIT among health care providers holds the potential to reduce the costs and increase the quality of health care in California. We recommend that the state seek to identify nonstate sources of funding from private health care organizations or provider organizations in order to participate in the proposed HIT programs to the extent possible. We further recommend that the state Office of Health Information Integrity be directed to take the lead in these efforts.

Disproportionate Share Hospital (DSH) Payment Increase. Under the federal DSH program, the federal government provides a pool of funds each year to supplement Medicaid reimbursements to hospitals that serve a disproportionate number of Medicaid or other low–income patients. The ARRA increases DSH funding by 2.5 percent a year for two years. We estimate this will result in additional federal payments of $54 million over that period to public hospitals in the state, including hospitals operated by the UC. The nonfederal share needed to access these DSH funds is provided by the public hospitals themselves in the form of costs they incur to deliver services. The federal DSH increase will result in automatic increases in payments to certain other hospitals by an estimated $9 million in General Fund costs ($24 million total funds) over the next two years due to current provisions in California law.

Transitional Medi–Cal. Current federal law requires states to provide an additional 12 months of coverage to families enrolled in Medi–Cal who increase employment income beyond a certain level. Under the ARRA, for a two–year period ending December 31, 2010, states could elect to (1) loosen restrictions on retaining this Medi–Cal coverage by automatically enrolling these families in 12 months of coverage and (2) waive the minimum enrollment period now needed to qualify for transitional coverage. We estimate that the state would incur General Fund costs of $59 million (assuming the enhanced FMAP provided in the ARRA) over two years to automatically provide the additional coverage for the approximately 150,000 current transitional enrollees. The state also would incur unknown costs as a result of waiving the minimum enrollment period requirements, as it is unclear how many enrollees might become eligible to receive the extended period of benefits. Given the state’s severe fiscal problems, we would recommend that the Legislature not expand this program.

Delay of Certain Medicaid Regulations. The ARRA extends through June 30, 2009, the current moratoria on certain federal regulations that could otherwise increase state and local costs for the Medi–Cal Program. For example, one regulation would limit the opportunity for the state to use so–called provider taxes to fund rate increases and achieve General Fund savings. It also imposes a new moratorium through June 30, 2009, on a regulation regarding outpatient hospital facility services. Lastly, ARRA expresses Congress’ intent that certain pending federal regulations should not be issued. If these federal regulations were in effect, the state and local agencies and health care providers would face potentially significant adverse fiscal impacts.

Other Health Provisions

In addition to the Medicaid provisions described above, the federal economic stimulus package includes additional funding for other health–related provisions. We summarize the most significant of these in Figure 9, and discuss them further below.

Figure 9

Other Major Health-Related Provisions in Federal Economic Stimulus Package |

Provision |

Fiscal Effects |

Available to

Offset General Fund Spending? |

Nationwide |

California |

Grant money for public health centers |

$2 billion for construction, certain technology, and general purposes. |

Unknown. |

No |

Health workforce funding |

$500 million for health workforce

development. |

Unknown. |

No |

Additional federal grants for Early Start program |

$500 million for the federal Individuals with Disabilities Education Act Part C grants. |

About $50 million for the Early Start Program. |

Yes |

Prevention and Wellness Fund |

$1 billion for various prevention and wellness programs. |

$34 million for vaccinations. Unknown for other programs. |

Unknown |

Supplemental funding for Women, Infants, and

Children |

$500 million for nutrition assistance programs, including $100 million for information systems. |

Unknown. |

No |

Safe Drinking Water State Revolving Fund |

$2 billion. |

$160 million to the state for drinking water projects that can begin construction before February 17, 2010. |

No |

Continuing employer-sponsored health

coverage (COBRA) |

Unknown. |

Unknown. |

No |

|

COBRA = Consolidated Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act. |

Grant Money for Public Health Centers. The ARRA provides $2 billion in grant money nationwide to qualified health centers, including federally qualified health centers. Of the $2 billion, $1.5 billion is for construction and renovation of facilities, and the purchase of HIT. The remaining $500 million is available to support new or existing health center sites or service areas and to provide supplemental payments for spikes in uninsured populations. At the time this report was prepared, the federal government had not established how it would distribute these funds.

Health Workforce Funding. The ARRA provides $500 million nationwide to support health care workforce development programs. Included in this amount is $300 million for the federal National Health Service Corps, which provides medical education scholarships and loan replacement funds as well as grants to medical training programs. The Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development currently administers various health care workforce development programs, including medical education support funded in part through $1 million annually from the National Health Service Corps. At the time this report was prepared, information was unavailable regarding how these funds will be distributed or how much California might receive.

Additional Federal Grant Funds for Early Start Program. The ARRA provides about $50 million in grant funding in FFY 2009–10 for the federal IDEA Part C early intervention programs, known in California as the Early Start program. This funding can likely be used to offset General Fund support of Early Start, which is administered by the state Department of Developmental Services. Some IDEA Part C funds support Early Start requirements in other departments including CDE and the Office of Administrative Hearings. At the time this analysis was prepared, it was unclear what process the federal government will follow to distribute these funds.

Prevention and Wellness Fund. The ARRA provides $1 billion nationwide for prevention and wellness efforts, including: (1) $50 million to prevent heath care–associated infections, (2) $300 million in grants to state and local health departments to vaccinate certain eligible children and adults, and (3) $650 million for clinical and community–based strategies that are proven to reduce chronic disease rates. The state is expected to receive $34 million of the $300 million for the vaccination program. A federal spending plan has not yet been announced for the remaining $700 million. Some funds will likely be distributed through grants, with guidelines for such grants announced by May 2009.

Supplemental Funding for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC). The ARRA provides supplemental funding of $500 million for the WIC nutrition assistance program, including $100 million for information systems. Although the state–by–state allocation of these funds has not been announced, it is likely that California will receive a portion of this supplemental funding in order meet the increasing demand for WIC services in the state.

Safe Drinking Water State Revolving Fund (SDWSRF). The ARRA provides an estimated $160 million to the state for “shovel–ready” drinking water projects that can begin construction before February 17, 2010. The state Department of Public Health (DPH) has already begun to solicit applicants and proposals for this funding and anticipates posting a list of eligible projects by April 2009. The DPH anticipates that, once the list is posted, it will begin awarding funding to eligible projects on a first–come, first–served basis until all funds are allocated.

Provisions to Continue Employer–Sponsored Health Insurance. The federal Consolidated Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act (COBRA) allows employees and/or their family members to temporarily extend their coverage in a group health plan when coverage would be lost due to certain events, such as loss of a job. This program can provide coverage up to 36 months. An individual must pay the entire monthly premium. Under ARRA, persons who lost employer–based health coverage between September 1, 2008 and January 1, 2010 due to job loss would be eligible for a federal subsidy. The subsidy would last for nine months and would cover 65 percent of the premium, with the individual responsible for the remaining 35 percent. The subsidy would be phased out for higher–income persons.

Below, we discuss how ARRA impacts workforce development programs and the unemployment insurance system in California.

Workforce Investment Act (WIA)

The federal WIA provides funding for a range of workforce development activities through statewide and local agencies. The WIA has separate funding streams for youth, adults, and dislocated workers. Pursuant to federal law, 85 percent of the state’s total WIA funds (an estimated $427 million in 2009–10) is allocated to local Workforce Investment Boards (WIBs). The remaining 15 percent ($64 million in 2009–10) is available for state discretionary purposes such as administration, statewide initiatives, and competitive grants for employment and training programs.

Additional WIA Funds. As shown in Figure 10, ARRA provides additional WIA funds of about $494 million for California. We estimate that about $420 million will be allocated to local WIBs to administer local workforce development activities, while an estimated $74 million will be available for state discretionary purposes. These additional WIA funds would be available for expenditure over the 2009–10 and 2010–11 state fiscal years.

Figure 10

Additional WIA Funds for California |

(In Millions) |

Category |

Estimated Allocation |

Adult |

$81 |

Youth |

188 |

Dislocated workers |

225 |

Total |

$494 |

|

WIA = Workforce Investment Act. |

Competitive Grants for WIA Funds. The ARRA also includes the following WIA discretionary grants for state, local WIBs, and other providers and agencies:

- $200 million available nationally for additional dislocated worker assistance.

- $50 million available nationally for YouthBuild activities, specifically targeting individuals who have dropped out of high school and re–enrolled in an alternative school.

- $750 million available nationally for competitive grants for worker training and placement in high growth and emerging industry sectors, including $500 million targeted for preparing workers for careers in energy efficiency and renewable energy.

Use WIA Funds for General Fund Relief. In the past, the Legislature has used the 15 percent state discretionary funds for new initiatives and to achieve budget solutions by offsetting General Fund costs for employment and training programs in other state departments. Given the state’s fiscal situation, we recommend that the Legislature direct all of the additional $74 million in discretionary funds to offset employment and training program General Fund costs in either the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation or the California Conservation Corps.

Other New Employment And Training Funds

Currently, the state receives about $80 million in Wagner–Peyser Act (WPA) to support employment services to individuals and employers at “one–stop” locations throughout the state. In addition, California receives about $10 million for Trade Adjustment Assistance (TAA), which targets training services to workers who have lost employment as a result of increased imports.

New Employment and Training Funds. The ARRA provides an additional $45.5 million in WPA funds to California for state employment services. The ARRA specifies that about $28 million be used to provide reemployment services for Unemployment Insurance (UI) claimants. We expect these additional WPA funds to be available in FFY 2008–09. The ARRA also provides additional TAA training funds through December 2010. Specifically, we estimate that California will receive an additional $17.3 million in FFY 2008–09, $17.3 million in FFY 2009–10, and $4.3 million in FFY 2010–11.

Unemployment Insurance

The UI program is a federal–state program that provides weekly UI payments to eligible workers who lose their jobs through no fault of their own. To be eligible for benefits, a claimant must be able to work, be seeking work, and be willing to accept a suitable job. Regular UI benefits can be paid for a maximum of 26 weeks, while federally funded extended benefits may be available to workers who have exhausted regular UI benefits during periods of high unemployment. The regular UI program is financed by unemployment tax contributions paid by employers for each covered worker.

As we discussed in the 2009–10 Budget Analysis Series: General Government (see "Restoring Solvency to the Unemployment Insurance Fund"), the UI fund is currently insolvent. The Governor has introduced a proposal to restore solvency to the UI fund, which remains under consideration by the Legislature. We find that the Governor’s plan has merit in that it restores solvency to the UI fund. The Employment Development Department, which administers the UI program, has already obtained a federal loan to cover projected fund deficits, which means there will be no interruption in benefit payments.

Figure 11 summarizes the major impacts of ARRA on the UI program. As the figure shows, we estimate that California could receive approximately $5.4 billion, with most funds going directly to recipients of unemployment benefits.

Figure 11

Unemployment Insurance (UI)—Major Fiscal Impacts |

(Through 2011-12, in Millions) |

Provision |

Amount |

Extended UI benefits now available through 2009 |

$3,200 |

Temporary increase of $25 in weekly benefits through 2009 |

1,000 |

Incentive payment if the state implements UI eligibility changes |

844 |

Temporary relief of state interest payments for UI federal loans |

314 |

Additional funds for UI administration |

60 |

Total |

$5,418 |

Extended and Increased UI Benefits. The ARRA extends the Temporary Emergency Unemployment Compensation (TEUC) program through the end of calendar year 2009. Eligible workers in California can receive up to 33 weeks of extended benefits under TEUC, which had been scheduled to terminate in March 2009. Our preliminary estimates indicate that the extension of TEUC will result in about $2.2 billion of extended benefit payments for eligible claimants in FFY 2008–09 and about $1 billion in FFY 2009–10.

The ARRA increases regular and extended benefits by $25 per week for claims filed by December 31, 2009. The federal government would fund this additional temporary benefit increase. Our preliminary estimates indicate that this temporary benefit increase will result in about $700 million in additional benefit payments for eligible claimants in FFY 2008–09 and about $300 million in FFY 2009–10.

Temporary Relief of UI Interest Costs for Federal Loan. As discussed above, states may receive federal loans to cover UI benefit payments when their funds are insolvent. Short–term federal loans are generally interest–free, but longer–term loans must be repaid with interest. While the principal amount of borrowed funds is repaid automatically from the UI fund whenever the fund has a positive balance, any interest charges must be paid with other state funds (usually the General Fund). The ARRA includes temporary relief of these interest payments for states with federal UI loans through December 31, 2010.

Additional Funds for UI Administration. The ARRA includes additional funds for state UI administration. We estimate that California will receive about $60 million of these funds in FFY 2008–09. These additional funds can only be used for certain UI administration purposes, including expenses for implementing federal options for UI modernization discussed below.

Our preliminary estimates indicate that ARRA‘s provision to temporarily waive UI federal loan interest costs will result in General Fund savings of $30 million, $209 million, and $75 million in state fiscal years 2009–10 through 2011–12, respectively. We note that these interest amounts depend on the nature of any corrective action to address the UI fund insolvency and/or the economy.

Incentive Payments Tied to Significant UI Program Changes. The ARRA includes incentive payments for states that choose to “modernize” their UI programs by expanding eligibility. These changes would essentially allow more low–wage, part–time, or other unemployed workers to be eligible for UI benefits. States can receive the first one–third of the incentive payment by adopting an alternative base period (ABP) for individuals who otherwise would not earn enough money to qualify for UI benefits using the existing base period. States can receive the remaining two–thirds of the incentive payment by adopting the ABP, as well as at least two of four provisions related to part–time workers, individuals who separated from their job for compelling family reasons, individuals enrolled in training programs, and dependent allowances. California’s estimated share of the incentive payment is about $844 million.

Potential State Fiscal Impacts. California currently provides part–time worker coverage and extended UI benefits for individuals in training programs, thus meeting two of the four requirements related to the two–thirds portion of the UI incentive payment discussed above. To receive any of the incentive payment, however, the state would have to adopt legislation implementing the ABP for determining UI eligibility.

Preliminary estimates indicate that the additional payments for individuals qualifying for UI benefits under the ABP would total about $70 million per year. In addition to the cost of these new benefit payments, implementing the ABP could be a timely and/or labor–intensive process, as it would require changes to the existing UI automated database. These one–time automation costs could be between $30 million and $40 million, but the state could use the additional UI administrative grant discussed above to cover these costs.

If the state implements an ABP in accordance with the federal requirements and receives an incentive payment of about $844 million, there could be several potential state fiscal impacts. It is our understanding that if a state’s UI fund is insolvent, it must use the incentive funds to pay UI benefits. This could result in a reduction in future General Fund costs if the fund continues to be insolvent past December 2010. This is because the incentive funds would reduce the state’s UI fund deficit, resulting in interest savings once the interest forgiveness period ends.

Conversely, if the UI fund were solvent, the incentive payment funds may be available for other purposes. These could include paying for administrative or capital expenditure costs (including automation) in the UI program or state employment services. Some of these actions could result in state General Fund savings.

When considering the ABP and the new federal incentive payments, we recommend that the Legislature examine these issues within the broader context of addressing the UI insolvency.

For social services programs and beneficiaries, ARRA provides an estimated $5.3 billion in federal funding for California from FFY 2008–09 through FFY 2010–11, as shown in Figure 12. About $2.8 billion is in the form of direct payments to individuals—mostly recipients of Supplemental Security Income (SSI), Social Security, and/or food stamps. With respect to state– and county–funded social services programs, ARRA provides about $2.2 billion in additional funding, much of which can be used to offset General Fund costs. Finally, ARRA provides about $300 million in additional funds to existing programs which have no state General Fund participation. Below, we describe how ARRA affects various social services programs.

Figure 12

Social Services—Summary of Impacts in California |

(In Millions) |

Programs/Provisions |

Amount |

Description |

Payments to Individuals |

One-time retiree payment |

$1,500 |

A one-time $250 payment to recipients of Social Security,

Railroad Retirement, and certain veterans benefits. |

One-time SSI payment |

320 |

A one-time $250 payment to about one million SSI recipients. |

Food stamps benefits |

970 |

A 13.6 percent increase in food stamps benefits. |

Subtotal |

($2,790) |

|

State Programs With General Fund Costs |

IHSS, ADHC, and MSSP |

$1,356a |

FMAP relief of 11.6 percent applies to these programs. |

CalWORKs |

450 |

New 80 percent federal financial participation for increased benefit costs since 2007. |

Child support enforcement |

175 |

Federal incentive funds eligible for 66 percent federal match. |

Adoption Assistance Program |

97 |

FMAP relief of 6.2 percent for state/county costs. |

Foster Care |

72 |

FMAP relief of 6.2 percent for state/county costs. |

DOR—Vocational Rehabilitation |

57 |

Additional funds to assist disabled individuals obtain and retain employment. |

DOR—Independent living services |

7 |

Additional funds for independent living centers and blind services. |

Food stamps administration |

22 |

Additional funds for state/county food stamps administration. |

CDA—Nutrition |

13 |

Additional funds for home-delivered and congregate meals. |

Subtotal |

($2,249) |

|

State Programs With No General Fund Costs |

DCSD—Weatherization |

$192 |

Grants to local agencies to assist low-income individuals with weatherization projects to reduce utility costs. |

DCSD—Local block grant |

89 |

Formula grants to localities to assist low-income individuals in becoming self-sufficient. |

CDA—Employment |

10 |

Additional funds for senior community service employment