May 2, 2006

In 2004, California temporarily extended, from 90 days to one year, the time that recently purchased vessels, vehicles, and aircraft must be kept out of California in order to avoid the state�s use tax. This report looks at the economic and fiscal impacts of the law change. We find that (1) the law change has resulted in a sharp reduction in out-of-state usage exemptions and an increase in sales and use tax revenues, and (2) the negative economic impacts arising from the measure do not appear to be particularly large.

This report has been prepared in response to Chapter 226, Statutes of 2004 (Senate Bill 1100, Committee on Budget and Fiscal Review). Among other things, Chapter 226 temporarily increases-from 90 days to one year-the period that a vessel, vehicle, or aircraft purchased by a California resident must be kept out of California following an out-of-state purchase in order to be exempted from the use tax. This extended one-year period applies to purchases made between October 1, 2004 and June 30, 2006, after which the out-of-state period reverts back to 90 days. The measure requires the Legislative Analyst�s Office to study the economic impact of the temporary law change and report its findings to the Legislature by June 30, 2006.

In this report, we provide background on the sales and use tax (SUT) as it applies to vessels, vehicles, and aircraft; discuss our findings relating to economic and fiscal effects of the measure; and then highlight some of the key policy issues raised by the application of Chapter 226.

The key findings from our analysis of Chapter 226 are as follows:

With regard to yachts and recreational vehicles, the measure has resulted in a sharp decline in out-of-state usage exemptions, and a corresponding increase in taxable sales, and SUT revenues (roughly $45 million a year). We believe that the measure also may have resulted in some declines in total sales and related economic activity in the state relative to what would have otherwise occurred. However, any such effects do not appear to be particularly large.

With regard to general aviation aircraft, Chapter 226 has had only minimal, if any, identifiable effects on the level of sales, exemptions, or revenues from the SUT. The negligible effect is partly due to the growing importance of the large business aircraft segment of the general aviation industry. These aircraft are often eligible for alternative exemptions (namely, those for common carriers and aircraft used in interstate commerce). As a result, the loss of the out-of-state usage exemption has not resulted in an increase in the proportion of purchases that are subject to California�s SUT.

From a tax policy perspective, we believe that the longer one-year use test is more appropriate than the 90-day test, in that it results in more accurate taxation based on the actual usage of a vessel, vehicle, or aircraft.

While the Governor has proposed a one-year extension of the Chapter 226 provisions, we believe it would be preferable to make the key provisions of Chapter 226 permanent. Otherwise, the state will be creating uncertainties and incentives for buyers to defer purchases in anticipation of more favorable tax provisions in the future.

California imposes a SUT on the final sale of tangible personal property. (The state does not tax the purchase of intermediate goods that are subsequently incorporated into final products.) The main component of the SUT is the sales tax, which is collected by retailers on most purchases made in California. The second component, the use tax, is applied to nonretail sales occurring inside California as well as purchases made outside of California involving goods which are then brought into California for storage or use in this state.

Vessels, vehicles, and aircraft purchased in California from licensed dealers are usually subject to the sales tax, which is collected at the time of purchase. In contrast, purchases from private parties made inside of California, as well as all purchases made outside of California for use in this state, are legally subject to the use tax. (In cases where the purchaser has already paid a sales tax to another jurisdiction, a credit is allowed against the use tax owed in California.)

Vessels of less than 26 feet (as well as some larger vessels used in inland waterways) and vehicles are registered in California with the Department of Motor Vehicles (DMV). As part of this registration process, DMV collects the use tax on behalf of the California State Board of Equalization (BOE). However, ocean-going vessels in excess of 26 feet are not registered in California, but rather are documented by the U.S. Coast Guard. Similarly, most private aircraft of any size are registered by the U.S. Federal Aviation Administration (FAA).

One implication of the federal registration of large vessels and aircraft is that, unlike the case for vehicles and smaller boats, there is no mechanism for the more-or-less automatic collection of the use tax. This is because neither the federal agencies nor other states involved collect use taxes on behalf of California. Instead, it is up to the buyer to submit the use tax revenues that are due to the state. Given that over 85 percent of such buyers have historically not voluntarily made tax payments at the time of the purchase (whether intentionally or unintentionally), BOE is faced with a major task in enforcing the use tax and ensuring that buyers of large vessels and aircraft comply with the tax law by submitting the use tax monies owed to the state. This is done through a multi-stage process, where:

The BOE�s Consumer Use Tax Section identifies �leads� from federal Coast Guard and FAA databases.

The board then initiates contact with potential taxpayers by sending them a return if they have not already voluntarily submitted one.

The purchaser then either pays the tax, provides evidence that he or she is not subject to the tax, or seeks one of the allowable exemptions from the tax.

The BOE reviews the application and either grants or denies the request.

As a general rule, the use tax is due either (1) within one year of the purchase date of an item or (2) by the end of the month following the date the buyer is contacted by BOE about having a tax liability, whichever comes first. Late payments are subject to interest and, in some cases, penalties.

The key point of the above situation from the perspective of evaluating the economic and fiscal impacts of Chapter 226 is that this enforcement process can easily take several months, and sometimes even years, to complete. As a result, use tax information is a less-precise and less-timely indicator of current sales trends for the involved commodities than are collections data for commodities subject to the sales tax, which is immediately collected by the dealer.

This potentially long time lag, coupled with the limited time period that has passed since the implementation of Chapter 226, means that the actual use tax collections data that are available at this time provide only a preliminary indication of sales trends that have occurred for the involved commodities since the revised use-tax exemption test became operative in October 2004. This is a significant limitation, given that, in the case of vessels, over three-fourths of overall sales activity is attributable to these nonretail transactions. As a result, our assessment below of the economic and fiscal effects of Chapter 226 necessarily involves rough estimates.

Chapter 226 deals with a key exemption to the SUT-out-of-state usage. The changes made by this act to the exemption are summarized in Figure 1 and discussed below. The accompanying box compares California�s laws with respect to vessels to other key yachting regions.

|

Figure 1 Use Tax Changes Made by Chapter 226 |

|

Vessels, Vehicles, and Aircraft Purchased Prior to October 2004 |

|

» Out-of-state purchases subject to the use tax if brought into California within 90 days of purchase. |

|

»

Use tax does not apply if vessel, vehicle, or aircraft

is used outside of |

|

» Provisions apply to both residents and nonresidents. |

|

Vessels, Vehicles, and Aircraft Purchased Between |

|

» Residents. Out-of-state purchases subject to use tax if brought into California within one year of purchase. |

|

»

Nonresidents. Out-of-state purchases

subject to use tax if used or stored in California

for more than six months of the first year of |

|

» Presumptions. Use tax presumed to apply if: |

|

� Owner is a California resident. � Purchase is subject to California registration fees (in case of vehicle) or property taxes (in case of vessel or aircraft). � Purchase is used or stored in California more than one-half of the time during the first 12 months of ownership. |

|

»

Repair Exemptions.

Exemption for purchases brought into state for |

What Are the Laws in Other Regions?One concern expressed about Chapter 226 is that it could put California at a competitive disadvantage with other major boating regions inside and outside of the United States. State Tax PoliciesOther states have a variety of policies regarding the taxation of vessels, vehicles, and aircraft. Some states with large yacht-building industries, such as Missouri and Rhode Island, exempt the majority of yacht purchases from their sales and use taxes (SUTs). However, as noted in the accompanying figure, tax policies in Washington and Florida-which are considered to be competitors with California-generally require that vessels used in state waters be subject to the use tax. Regarding specific provisions and exemptions, some in Florida and Washington are less rigid than in California, while others are more rigid. For example:

International Tax PoliciesForeign tax treatment relating to the SUT on yachts and other commodities varies a great deal from country to country. With regard to countries neighboring the U.S., key provisions affecting potential U.S. yacht purchasers are as follows:

|

Prior to October 2004, any vessel, vehicle, or aircraft purchased out of state was generally subject to the SUT if it was either purchased in California or if it was brought into California within 90 days of its purchase date (the so-called �90-day test�). Property held outside of California for the initial 90-day period was presumed to have been purchased for out-of-state use, and thus was exempt from taxation. In addition, if the property was brought into California before the 90-day period was up, it could still be exempt if it was subsequently used and stored outside of California at least one-half of the time during the six-month period immediately following its initial entry into the state (the so-called �principal-use test�).

Over time, a growing number of purchasers-particularly of yachts and recreational vehicles (RVs)-used the 90-day test to claim the out-of-state usage exemption. In the case of vessels, this often involved taking possession more than three miles offshore, sailing the vessel directly to Ensenada or other sites near the U.S. border, and then storing it for 90 days or more before returning to California. In the case of RVs, it often involved taking possession in Arizona, Nevada, or Oregon, then using or storing the vehicle outside of California for at least 90 days before returning to the state. The enactment of Chapter 226 was in response to concerns about growing usage of this exemption and the belief that this involved assets that would subsequently be used on an ongoing basis in California instead of outside of the state.

General Provisions. Under the act, vessels, vehicles, or aircraft purchased by California residents between October 1, 2004 and June 30, 2006, are subject to the use tax if the property is brought into California within one-year after its purchase (the so-called �one-year test�). Nonresidents can bring the property into California within the first year of purchase, but to be exempt from taxation they are required to store or use the property outside the state more than six months during the first year. The measure also establishes a presumption that any vessel, vehicle, or aircraft purchased by a resident or nonresident outside California is for use in this state if the property is subject to California registration or property taxes in the first twelve months of ownership. This presumption can be overturned with documentation of purchase, registration, and usage outside the state.

Repair, Retrofit, or Modification Exemptions. Under Chapter 226, aircraft or vessels brought into California within the first 12 months for repair, retrofit, or modification (RRM) are not subject to the use tax, if the flying or sailing time logged by the owner (or the agent of the owner) during the RRM period is 25 hours or less. This 25-hour limit does not apply to travel time needed to leave the state after the repairs or modifications are completed.

In order to assess the impacts of changes to the out-of-state usage exemption, it is important to understand both the frequency with which it is used, as well as other exemptions that are available to buyers of vessels, vehicles, and aircraft. Altogether, there are 13 exemptions in the use tax law, ranging from purchases between family members to transfers between related businesses. However, in addition to the exemption for out-of-state usage (the subject of Chapter 226), there are three other exemptions of major relevance to purchasers of vessels, vehicles, and aircraft. These are the exemptions for (1) commercial fishing, (2) interstate commerce, and (3) being a common carrier. The key provisions of these three exemptions are highlighted in Figure 2.

|

Figure 2 Other Key Exemptions

Used by Buyers of |

|

|

|

» Commercial Deep Sea Fishing |

|

�

Provided for vessels principally used outside the

three-mile territorial |

|

�

Numerous requirements to satisfy exemption, including

minimum |

|

» Interstate and Foreign Commerce |

|

�

Provided for vessels, vehicles, or aircraft which are

engaged in |

|

�

Examples include charters or sight-seeing tours

involving stops in |

|

» Common Carrier |

|

� Provided for aircraft used as a �common carrier� of passengers or cargo during the first 12 months of operational use. |

|

� Includes aircraft used for charters or in business. |

|

�

Numerous requirements, including Federal Aviation

Administration |

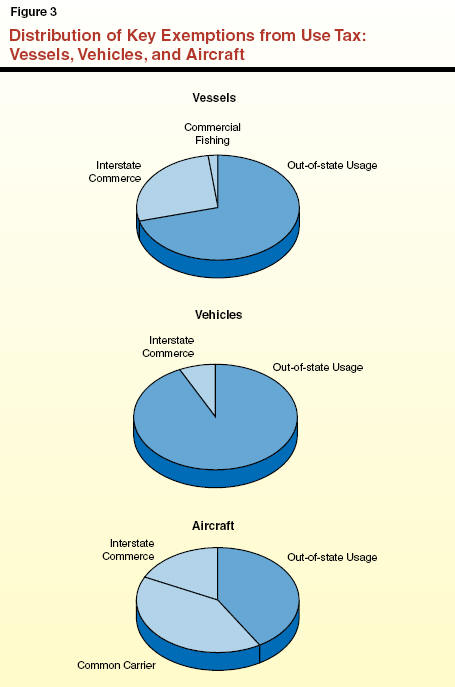

Figure 3 shows the distribution of exemptions granted over the past five years for out-of-state usage, commercial fishing, being a common carrier, and interstate commerce. It shows that the out-of-state usage exemption accounted for:

Roughly two-thirds of the total value of exemptions claimed for vessels, with the interstate commerce exemption accounting for most of the remaining one-third.

About 90 percent of the total value of exemptions claimed for vehicles.

Roughly 40 percent of the total value of exemptions claimed for aircraft, with the other 60 percent split between the interstate commerce and common carrier exemptions.

One question related to Chapter 226 and its impacts is whether purchasers, no longer qualifying for the out-of-state usage exemption, can find other means to avoid the use tax. If this were to occur frequently, the added revenue from the limits placed on the out-of-state usage exemption might be largely or even entirely negated. This can occur through two avenues-(1) the use of an alternative exemption or (2) utilizing certain other provisions of the tax law, such as changing the organizational form of a business.

This avenue involves a taxpayer substituting the use of the out-of-state exemption for one of the other exemptions allowed for in the use tax and noted above.

Aircraft. Based on our review, we conclude there definitely is potential for such substitution to occur in aviation-related purchases, where many of the larger general aviation aircraft already qualify for more than one exemption. For example, an aircraft purchased by a multiregional company may have been exempted from the California use tax under the out-of-state usage test, but may also have qualified for the interstate commerce exemption (to the extent it was being used to transport company employees to out-of-state destinations) and/or common carrier exemption (to the extent it was being used in charter flights). Board staff report that they have received additional claims for interstate commerce and common carrier exemptions since the enactment of Chapter 226.

Vessels and Vehicles. The opportunities for purchasers of private vessels and vehicles are more limited than for aircraft, partly because of the stringent requirements needed to qualify for these alternative exemptions. For example, in order to receive the commercial fishing exemption, owners must provide substantial evidence of commercial fishing activities, including global positioning satellite (GPS) readings to establish that the activities took place in international waters, income tax returns showing profits from fishing activities, and photographs of the vessel showing that it is equipped for commercial fishing activities.

Beyond claiming allowable exemptions other than for out-of-state usage, buyers in some circumstances have other options to minimize or avoid the impact of Chapter 226. For example, residents of California could form an out-of-state corporation for the purpose of purchasing a vessel, vehicle, or aircraft. The property involved would then be subject to less stringent nonresident tests. It is our understanding that these alternative options are used less extensively than exemptions as a means of avoiding use taxes, as they can involve significant expenses and a variety of legal issues.

By lengthening the time that purchasers need to keep vessels, vehicles, and aircraft out of state in order to fulfill the requirements for an out-of-state usage exemption, Chapter 226 was expected to result in fewer exempt sales and an increase in SUT revenues to California. At the same time, however, industry representatives asserted that the law changes would have negative impacts on California business activities and profitability. These concerns were most notable with respect to the yachting industry, where it was argued that Californian�s would be put at a competitive economic disadvantage with those in other yachting regions, such as the northwest and Florida. Given these concerns, our analysis below focuses first and foremost on the impacts of Chapter 226 on the yachting industry. We then turn to discussions of the measure�s impacts on vehicles (mostly RVs) and aircraft.

California is home to roughly one million boats, yachts, and other vessels, making it the third largest boating state in the nation behind Florida and Michigan. This total includes about 250,000 private watercraft (such as jet skis), 714,000 boats registered with DMV, and 26,000 vessels documented with the U.S. Coast Guard. While in theory, the out-of-state usage exemption could apply to any vessel, as a practical matter, it applies mostly to a subset of the 26,000 vessels documented by the U.S. Coast Guard. Vessels less than 26 feet are not very good candidates for offshore purchases because of the cost, time, and effort needed to complete such a transaction. According to maritime attorneys we spoke to, the threshold price level where offshore transactions made sense was roughly $100,000 under the 90-day test, or about the price of a typical three-year-old 30-foot yacht. The level is now about $500,000 under the one-year test (about the price of a typical three-year-old 45-foot yacht).

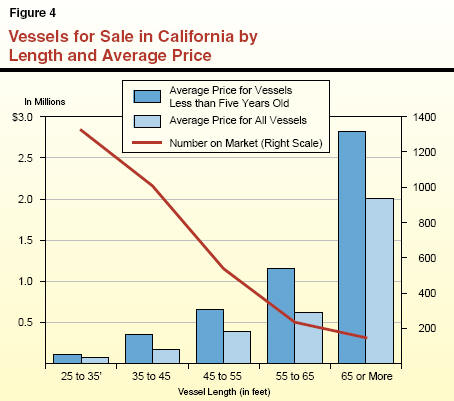

As indicated in Figure 4, prices of yachts for sale in California in the 25-to-35 foot range average about $70,000 ($115,000 for yachts less than five years old). The average price rises up to $615,000 for vessels in the 55 to 65 foot range ($1.1 million for those less than five years old). At the very high end, �mega-yachts� can easily run into the tens of millions of dollars. The figure also shows that, not surprisingly, the majority of yachts on the market are in the 25-foot to 45-foot range, with a relatively small proportion of yachts in excess of 65 feet.

The comparatively small number of high-end yachts on the market has significant implications for the potential economic and fiscal effects of Chapter 226. Even if buyers of high-end yachts have the resources and mobility to keep their yachts out of state long enough to meet the extended one-year test, they represent only a small share of the total yacht market.

For these reasons, the state is likely to gain substantial revenues from Chapter 226 even if it results in a loss of some business activity associated with the operation of high-end yachts.

California has a large number of businesses involved directly or indirectly in yachting-related activity in California. These include boat dealers, yacht brokers, marina operators, vessel repair facilities, lenders, and insurance providers. The state also has a significant number of businesses involved in parts manufacturing, boat design, and building. While the state has some facilities involved in yacht building, it is not one of the major locations of such activity. California�s largest shipyard (National Steel and Shipbuilding in the San Diego area) is involved in the building of large commercial and naval vessels.

The industries with potentially the greatest exposure to impacts arising from Chapter 226 would be those that are most dependent on local sales and operations, such as brokers, dealers, and lenders. Boat builders, designers, and parts manufacturers are less likely to be affected because their markets are primarily nationwide and worldwide in scope. Some types of companies, such as vessel repair facilities, fall somewhere in between, in that they could serve both local and national (or in some cases international) markets.

By extending the period that purchasers must keep vessels out of state to avoid taxation, Chapter 226 raises the after-tax cost of purchasing a vessel for those who would otherwise have taken offshore possession. This cost increase would be the lesser of the added expense of paying the SUT or the value of the added time and other costs needed to keep the vessel out of California to meet the one-year test. The impacts of this change on governmental revenues and economic activity would depend on how prospective buyers reacted to the after-tax price increase.

The potential range of impacts on individuals from Chapter 226 can be demonstrated using a hypothetical example. In this example, we assume that a California resident plans to make an offshore brokered purchase of a 50-foot yacht costing $750,000. Following the 90-day period, the buyer then plans to bring the vessel back into California for permanent use and storage. The buyer also plans to invest about $75,000 in upgrades and renovations undertaken in California within the first year. The yacht is assumed to be used roughly two-to-three days per month during the first year after its purchase, incurring normal operating costs for fuel and maintenance. Finally, we assume a combined state and local SUT rate of 8 percent.

Under Chapter 226, this buyer can no longer use the 90-day test, and thus would be faced with four basic options:

Option A-Buy the Same Vessel and Pay the Use Tax in California. If the individual were to take possession of the vessel in California, and keep the yacht in the state the full first year, the state would gain $60,600 in SUT revenues and the local economy would benefit from about $15,600 in new expenditures in the first year (see Figure 5). Most of the SUT increase is from use taxes due to the elimination of the exemption on the yacht sale, although a small portion is related to sales of fuel and other taxable items made during the additional three months that the yacht is in California during the first year (since the buyer is no longer storing it in Mexico for 90 days). Under this scenario, there would be no ongoing economic and fiscal implications, since the law change would have no impact on ongoing usage or storage of the yacht.

|

Figure 5 Illustrative Effects

of Chapter 226 on a |

|||||

|

(In Thousands) |

|||||

|

|

Effect on the |

|

Effect on |

||

|

|

First Year |

Ongoing |

|

First Year |

Ongoing |

|

Option A—Purchase original vessel in state |

$60.6 |

— |

|

$15.6 |

— |

|

Option B—Purchase smaller vessel in state |

55.3 |

-$0.2 |

|

14.3 |

-$5.7 |

|

Option C—Meet one-year test |

-4.7 |

— |

|

-121.9 |

— |

|

Option D—Cancel purchase |

-4.7 |

-2.3 |

|

-214.9 |

-62.6 |

|

|

|||||

|

a Assumes $750,000

yacht purchased through a broker and one-time renovations equal to

10 percent of purchase price. Includes one-time expenses associated

with legal and closing costs, as well as |

|||||

Option B-Purchase a Smaller Vessel and Pay the Use Tax in California. If the individual were to purchase a smaller and less expensive yacht in California in response to the after-tax price increase caused by Chapter 226, the state would still benefit from collecting use taxes on the initial purchase, although the amount would be less than under Option A. For example, if the price were reduced by the full amount of the use taxes due under Option A, first-year taxes would be $55,300 under Option B. In addition, because of the lower operational costs associated with a smaller yacht, both sales taxes and new local business-related expenditures would decline modestly in subsequent years. (A somewhat related effect would occur if the increased yacht-related tax costs were partly absorbed by yacht sellers in the form of lower pre-tax sales prices.)

Option C-Comply With the One-Year Test. If the buyer decided to keep the yacht outside of California for the full year and make the $75,000 in planned renovations elsewhere, the state would lose about $4,700 in sales taxes and about $122,000 in business-related expenditures in the initial year. These reductions would be related to the loss of the one-time in-state renovations and the nine months of operational-related expenditures during the first year. There would be no ongoing effects, assuming the yacht was used in California on a permanent basis.

Option D-Cancel Purchase Altogether. If the law change were to result in a cancellation of the purchase, the state would lose about $4,700 in sales taxes in the first year and about $2,300 on an ongoing basis. The reduction would be related to the taxable portion of the vessel�s renovations and operational expenses that are no longer being made. The loss in business receipts would be about $215,000 in the first year-related to lost broker fees, renovation costs, and operational expenses.

The above illustrates how individuals might respond to Chapter 226. Next, we consider how these responses-in aggregate-might affect the state�s revenue and economy. After that, we discuss available evidence on these issues.

The aggregate impact of Chapter 226 would depend on the mix of these responses in California. At one extreme, if the great majority of buyers simply went ahead and purchased the vessel in California, then the measure would result in a large increase in revenues and a modest increase in economic activity. At the other extreme, if the main effect was a cancellation of buyer plans, then Chapter 226 would result in less revenues and economic activity.

The actual mix of reactions would depend on such factors as the sensitivity of buyers and sellers to changes in after-tax vessel prices, and the mobility of buyers-that is, their ability to shift purchases and usage of a vessel from California to other regions.

Although economists generally believe that demand for yachts and other luxury goods is �price elastic� (that is, sensitive to after-tax price changes), historical experience does not provide a clear picture of the exact degree of this price sensitivity. For instance, there is considerable dispute over how much spending on yachts and other luxury goods was affected by the 10 percent luxury tax imposed by the federal government in the early 1990s. At the time, many industry observers asserted that the luxury tax was sharply depressing spending on the affected items, and as a result, it was raising much less revenue than anticipated. However, a retrospective study by the Joint Tax Committee (JTC) of the U.S. Congress found that luxury tax collections attributable to yacht sales were actually greater than expected. The JTC was not, however, able to isolate the exact reason for the greater-than-expected level of collections-for example, whether it was due to smaller-than-expected behavioral responses. Other studies similarly concluded that it was not possible to disentangle the behavioral effects of the law change from other factors (such as changing wealth and income levels) affecting the estimate.

While historical experience does not provide a clear guide as to the specific aggregate effects of Chapter 226, the illustrative effects shown in Figure 5 do demonstrate a couple of important points about the probable impact of the measure:

First, in terms of revenues, they show that the SUT revenue gains associated with a shift from an out-of-state to an in-state purchase-even if the buyer purchases a smaller vessel-vastly outweigh the revenue losses associated with buyers extending their out-of-state usage times or canceling sales. This is simply a reflection of the fact that the operational expenses subject to the sales tax are only a fraction of the sales price of the vessel. This would be the case even if those extending their out-of-state usage periods were predominantly owners of the more expensive yachts. Thus, we would expect the measure to result in SUT revenue increases unless a very high proportion of buyers react to Chapter 226 by canceling purchases or extending their time outside of California.

Second, in terms of economic activity, expenditures in yachting-related industries would increase modestly in the first year if the predominate effect of Chapter 226 was an increase in in-state vessel sales (largely because yacht owners would no longer operate and store their yachts outside of California during the first 90 days after purchase). However, they would decline modestly if the predominate effect was buyers settling for smaller yachts, and more significantly if the predominant effect was a cancellation of sales in the state.

Based on the data available so far, it appears that the measure has resulted in major declines in the out-of-state usage exemption, an increase in sales subject to California�s SUT, and thus a roughly $20 million annual increase in SUT receipts from vessel-related purchases. The measure may have also reduced business activity and sales receipts in the yacht-related industries in the state relative to what would have otherwise occurred. However, there is no evidence that these reductions have been particularly large.

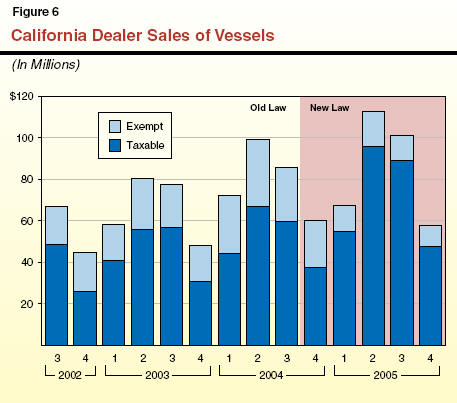

Figure 6 shows BOE data on sales of licensed boat dealers, as well as the breakout between in-state (and thus taxable) and out-of-state (and thus tax-exempt) purchases. The data include sales of all sizes of vessels sold through dealers, including smaller craft that would not be candidates for offshore delivery, as well as boating equipment and supplies sold through their outlets. Consequently, it is a far-from-perfect measure of the high-end yacht sales potentially affected by Chapter 226. However, it is at least a reasonable indicator, in that it includes a significant number of dealers selling high-end yachts. The figure shows:

Retail Sales Up. The figure shows that sales fluctuate a great deal over the year, with spring and summer months generally accounting for the bulk of annual sales. Despite this considerable quarter-to-quarter variation, the overall trend remained on an upward track in 2005, the first full calendar year following the implementation of Chapter 226. Total retail sales (both taxable and exempt) were up 6.8 percent between 2004 and 2005.

Retail Sales Exemptions Down. The figure also indicates that exempt sales dropped from 34 percent of total sales in 2004 to 15 percent in 2005, suggesting a large drop in out-of-state usage exemptions.

Net Result-Higher Taxable Sales and Revenues. The combination of higher retail sales and reduced exemptions caused an increase in both taxable sales and sales tax revenues associated with vessels in 2005. Specifically we estimate that taxable sales were up almost 40 percent and that sales tax receipts were up by about $5 million because of the law change.

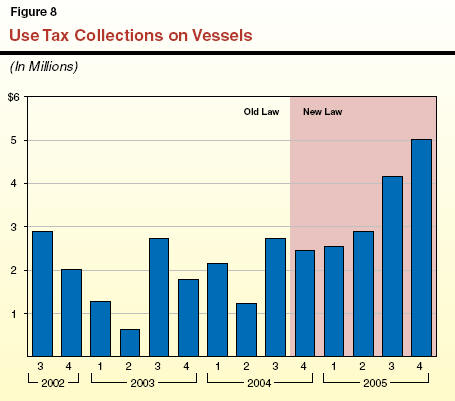

As indicated earlier, most large yachts are �brokered� sales rather than dealer sales. These transactions are potentially subject to the use tax. Information provided by BOE on use tax revenues, though preliminary, shows two striking trends.

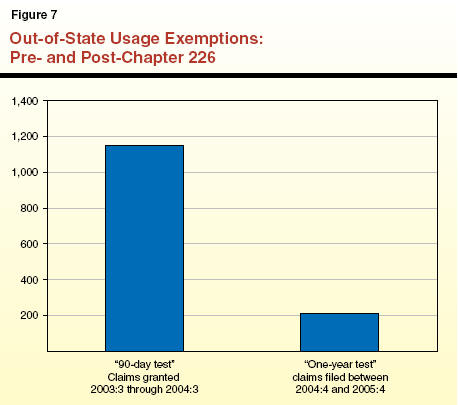

Use Tax Exemption Claims Down. As shown in Figure 7, BOE granted a total of 1,150 out-of-state usage exemptions during the five quarterly periods preceding the operative date of Chapter 226. In the five quarterly periods since the measure�s implementation, the number of claims filed under the one-year test was just 209, a drop of over 80 percent.

Use Tax Collections Up. Figure 8 shows use tax collections on vessels from the third quarter of 2002 through the fourth quarter of 2005. The figure shows a sharp increase in quarterly collections beginning in the latter part of 2005, which we believe is related to the fewer exemption claims and relatively steady level of sales occurring after the operative date of Chapter 226. As noted earlier, payments often do not occur until several months after the actual sale, due to the time lags associated with identification and notification of the taxpayer by BOE. As the figure shows, quarterly payments reached about $5 million by the end of 2005, more than twice the quarterly level one year earlier. This quarterly increase translates into an annual gain of about $10 million. Beyond this, we expect additional use tax receipts of up to $5 million associated with audits and delayed payments.

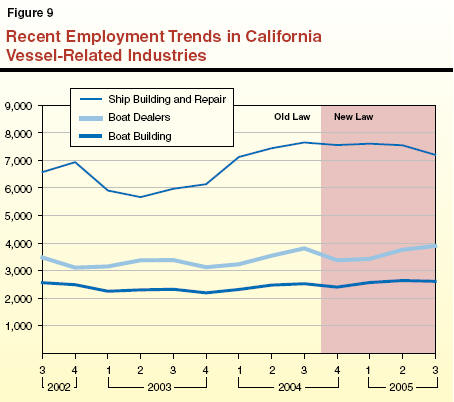

Other economic indicators we examined provide a somewhat mixed picture regarding activity in California�s yachting industry. In no cases, however, do the indicators reveal a major reduction in business. For example:

Employment Generally Healthy. Employment and wages of boat dealers increased in 2005 (see Figure 9). The job totals in the shipbuilding and repair industry are off slightly from their fourth quarter 2004 peak, but are still up substantially from their 2003 levels. (The same is true of their wage totals, which means that the job changes are not due to a shift toward increased part-time work.)

Southern California Marina Occupancy Rates High. Although there is some seasonal variation, demand for slip space is generally high, with many marinas reporting waiting lists (in some cases of over 10 years). Significant expansions are also being planned.

Marina Occupancy Rates Down in Mexico. This is particularly true in areas near Ensenada that had been dubbed �90-day yacht clubs� in light of the large population of U.S. owners of recently purchased yachts with very limited-term (three- or four-month) contracts.

Yacht Broker Licenses Up. The number of California yacht broker license issuances and renewals increased between 2004 and 2005.

In interpreting these developments, it is important to remember the difficulty in separating out the impacts on the yachting industry of law changes such as Chapter 226 from other factors like changes in the economy. As a result, we would stress that the generally positive sales and related indicators involving the yachting industry do not imply that Chapter 226 had no adverse impacts on it. Such adverse impacts may have been masked, for example, by the positive effects of rising wealth and income levels in the economy during 2005. It may well be the case that yacht-related industries, though generally healthy, were less robust than they would have been had Chapter 226 not been enacted. The various indictors cited above, however, suggest that any such adverse effects have not been particularly large.

In conjunction with our review of the economic, tax, and related indicators discussed above, we also contacted a number of individuals involved in various aspects of the yachting industry-particularly in Southern California. These included maritime attorneys, brokers, and representatives of dealers, lenders, and shipyard facilities. Individual responses regarding the perceived impact of Chapter 226 on the California yachting industry varied significantly, with some indicating only mild adverse effects and others indicating that the negative impacts have been substantial. Despite the diversity of responses, however, we found some recurring themes.

Consensus View-Business Generally Healthy in 2005 . . . Although many representatives expressed serious concerns about the negative impacts of Chapter 226, the majority of individuals we spoke to indicated that their own business had been reasonably good and that overall business conditions were generally positive in the industry during 2005. There were some notable exceptions to this view among yacht dealers, but in most cases, the perception was that business conditions were generally upbeat during the past year.

. . . But Not As Good As It Could Have Been. Several individuals indicated that, while business in California was reasonably strong, the state was nevertheless being adversely affected by the law change. In particular, there was a sense that California is losing market share to Florida and Washington. The concerns shared were mostly about high-end business, where buyers are quite mobile geographically and willing to purchase and use yachts in a variety of different regions.

Some Cooling Effect As June 30, 2006 Approaches. Although we did not hear of many specific examples of buyers postponing purchases in anticipation of the June 30, 2006 sunset date, some brokers indicated that, as the date approaches, there is increasing talk by prospective buyers about �going slow� in anticipation of the return to the 90-day test.

Ship and Repair Facilities Business Mixed. One of the key concerns voiced by industry representatives is that Chapter 226 is having adverse impacts on California�s ship yard and repair facilities. The concern has been that these facilities were already facing stiff competition from lower-cost yards in Mexico, and that the new law would make them even more vulnerable. This would occur to the extent that Chapter 226 reduced California sales or resulted in vessels being kept out of state longer to meet the one-year test. This is because repairs and renovations tend to be made most frequently in the period immediately following a vessel�s purchase.

The representatives we contacted from major boat repair facilities in Southern California indicated that their business was generally positive in 2005, with revenues up, in some cases by more than 10 percent between 2004 and 2005. At the same time, they indicated that some of their growth was from unusually large projects, and that some segments of their business may have been adversely impacted by Chapter 226.

Based on various tax-related sales data, discussions with industry representatives, and a variety of other indicators, we conclude that:

Chapter 226 has not resulted in the sharp reduction in vessel-related sales activity that some had feared. Dealer-related sales increased in 15 months following the operative date of the measure, and use taxes are up sharply.

The measure may have reduced sales and business activity in California from levels that would have otherwise occurred. Some reductions would not be surprising in view of the higher after-tax purchase prices faced by buyers that had planned to meet the 90-day test. The information available at this time does not permit us to draw any firm conclusions about the precise magnitude of these effects. We can say, however, that the effects do not appear to be particularly large.

The law change has resulted in a substantial decline in out-of-state usage exemptions and a corresponding increase in the amount of transactions which are taxable.

Given these factors, the Chapter 226�s changes have resulted in increases in state and local revenues-probably in the range of $20 million in 2005-06.

The second major product category affected by Chapter 226 is vehicles. Although this category includes trucks, buses, and automobiles, the main impact focus of the measure is on sales of RVs. According to the 2002 Economic Census of the United States, there were 326 retail RV dealers in California, accounting for $2.1 billion in sales, 5,140 workers, and $200 million in wages (each roughly 14 percent of the national total for the industry). The state also has 10 firms and over 2,600 employees involved in the manufacture of motor homes and parts, including the headquarters of the second largest RV manufacturer in the nation.

The average cost for new motor homes is around $180,000, with luxury models generally running in the $300,000 to $500,000 range, and a few selling for more than $1 million.

According to BOE data, about 28 percent of the dollar value of RV sales by California dealers during the five quarterly periods preceding the operative date of Chapter 226 were �interstate sales,� largely due to the out-of-state usage exemption.

In theory, Chapter 226 would have the same general types of effects on the RV market as on the yachting market in California. The longer one-year test period raises the cost of purchasing an RV to those prospective buyers that would have otherwise fulfilled the 90-day test and thereby been granted an exemption from the California SUT. The higher cost facing buyers would be somewhat less than the full sales tax amount, after taking into account the real and imputed costs associated with out-of-state transactions (including storage fees).

The increased after-tax costs would likely result in some decreases in California sales, as well as the substitution toward less-expensive models. The sales reductions would have ripple effects on other businesses, such as insurance, finance, repairs, and services. However, we would not expect the effects on California RV-related manufacturers to be particularly large, since their markets are national in scope.

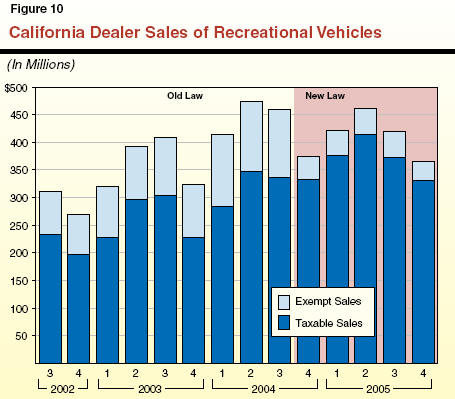

Figure 10 provides BOE data on retail sales of California RV dealers. It shows that:

Total sales increased significantly in 2003 and 2004, but then fell slightly in 2005.

The percentage of exempt interstate sales fell sharply, from an average of 28 percent during the five quarters preceding the effective date of Chapter 226 to an average of 11 percent during the five quarters following the effective date. As a result, the proportion of purchases that were taxable rose significantly during the period following the implementation of the act.

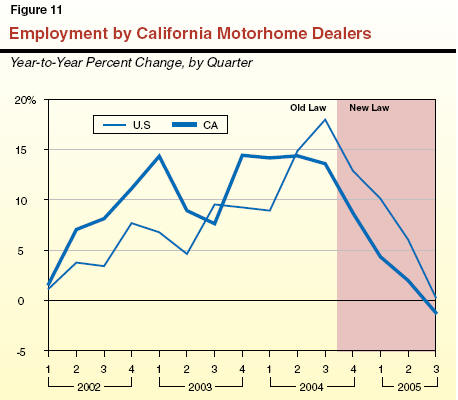

A key question is the extent to which the 2005 slowdown in RV sales was attributable to Chapter 226 versus other economic factors. While it is not possible to allocate precisely the sales decline to specific factors, it appears that the great majority of the slowdown is related to broad economic circumstances, as opposed to Chapter 226. RV sales have historically been heavily influenced by fuel costs, interest rates, and consumer confidence levels, and there were negative developments in all these areas in 2005. Fuel prices soared, interest rates rose significantly, and consumer confidence dipped in the middle of the year.

These developments led to a major slowdown in motor home sales across the nation. The U.S. wholesale shipments of motor homes to dealers fell by more than 10 percent in 2005, reflecting particularly large declines in the latter half of the year. As shown in Figure 11, employment associated with RV dealers slowed by about the same pace nationally as in California in 2005. In short, the slowdown in California RV sales appears to be consistent with national trends, suggesting that the role played by Chapter 226 was generally modest during this period.

Taking into account the sharp decline in out-of-state usage exemptions and our assessment that the impact of the law change on overall vehicle sales was fairly limited, we estimate that Chapter 226 resulted in a roughly $25 million increase in SUT revenues in 2005-06.

The third broad category of transactions affected by Chapter 226 is aircraft. Virtually all of the large commercial aircraft operated by scheduled airliners and cargo carriers are exempt from the SUT under the common carrier and interstate commerce exemptions. Thus, the potential effects of Chapter 226 would be limited mainly to the general aviation segment.

About 75,000 certificated private pilots, 38,000 registered general aviation aircraft, and 224 general aviation airports are located in California. In addition, the state has 30 commercial service airports which provide both scheduled passenger and general aviation services. There are also a large number of businesses related to the general aviation industry, including lending, insurance, flight training, aircraft fuel, repair, and maintenance.

California has a significant number of businesses involved in the design and production of aircraft parts, navigation equipment, and other avionics. However, there is not a significant presence within California of companies involved in the production of general aviation aircraft.

Business Related Activity Accounts for Majority of General Aviation Sales. There has been a general decline in the recreational portion of the aviation industry over the past 30 years. In addition, there has been more recent growth in the business-related segment, where prices of turboprops and jets can easily run in excess of $10 million (perhaps 100 times the value of a typical single-engine recreational aircraft).

Taxability of Sales. Historically, the majority of business-related aircraft have been exempt from California�s SUT. This is because they are often used to transport employees or officers to destinations between states (making them eligible for the interstate commerce exemption) or are purchased under lease-back arrangements with charter companies (making them eligible for common carrier exemptions). According to BOE, over 75 percent of all aircraft sales through California dealers during the five quarterly periods preceding the operative date of Chapter 226 were exempt from the SUT.

Given the large proportion of aircraft sales that qualify for the common carrier and interstate commerce exemptions, the potential effect of Chapter 226 would be inherently less for aircraft than for yachts and RVs.

As shown in Figure 12, total sales by California aircraft dealers rose slightly during the quarters following the implementation of the new law, and the share of exempt sales remained constant, near 75 percent. Preliminary data suggest that there were almost no increases in aircraft-related use tax collections following the law change. Thus, the associated revenue gains due to Chapter 226 are negligible.

Taking into account the economic and revenue impacts discussed above for vessels, vehicles, and aircraft, we estimate that the combined impact of Chapter 226 on SUT revenues is a revenue increase of about $45 million in 2005-06. The General Fund share of this total is about $28 million, with the remaining portion going to state special funds and localities. These amounts are modestly less than the original estimates of the Chapter 226 fiscal impact, which were $55 million for all funds, and $35 million for the General Fund. This estimation difference is related to revenues from aircraft sales. Specifically, BOE had anticipated that $11 million in additional revenues would be collected from the SUT on aircraft, but the initial data show no identifiable increase from this category.

There are several policy and technical issues related to Chapter 226 that the Legislature will need to consider as it evaluates the Governor�s proposal to extend the measure for one additional year. These key questions are discussed below.

What Is the Underlying Objective? The basic principle for determining the application of the use tax is whether the asset is being purchased for use in California. This determination can be a complicated issue for certain vessels, vehicles, and aircraft, which have long lives, are mobile, and thus may be used in numerous places over their lifetimes. While, in theory, use taxes could be apportioned to various different taxing jurisdictions over time based on where the assets are used, such a process would, in practice, be virtually impossible to administer and enforce by the state�s taxing agencies.

What Approach Makes Sense in Practice? In view of these complications, California and other states have adopted tests, which are rough approximations for determining whether property that is being purchased is, in fact, for use in California. As noted earlier in this report, prior to October 2004, California used the so-called 90-day test, meaning that the purchased item was presumed to be for usage in California unless it was kept outside the state for at least 90 days after its acquisition. Under Chapter 226, the test period was temporarily extended to one year. The basic tax policy question regarding Chapter 226 is whether the one-year test is a more appropriate measure for determining usage than the 90-day test. Our review suggests that:

Neither Test Is Perfect. For example, a taxpayer that purchased a vessel for use in California but then, because of changing circumstances, ended up using it elsewhere, would be disadvantaged by either the 90-day or one-year test. This is because he or she would have paid use taxes up front on an asset that was principally used outside of California.

However, a One-Year Test Is More Appropriate. Although any simple usage test has limitations, we believe that the one-year standard is a better approximation of actual usage than is the 90-day test. The striking decline in claims for the out-of-state usage exemption for vessels and RVs that occurred when the test was expanded to one year strongly suggests that the majority of the 90-day exemptions were made for assets that were purchased for use in this state. In this regard, we believe the one-year test is a better approximation of actual usage than is the 90-day test.

Even if the one-year test is more appropriate from a tax policy perspective, the question remains as to whether the change from a 90-day test to a one-year test has had an unduly harsh impact on the industries affected. As we reported above, it is likely that the extended one-year test has had some adverse effects on California�s yachting and RV industries. In instances where the state is competing with other states and countries for business, the Chapter 226 changes could also have adverse effects on California�s competitiveness. The initial data we have observed, however, suggest that these effects have not been particularly large.

If the Legislature chooses to postpone or eliminate the sunset date for Chapter 226, we believe that there are actions that it could take which would (1) address some of the concerns raised by the affected industries and (2) not weaken the basic intent of Chapter 226 regarding application of the use tax to vessels, vehicles, and aircraft. These actions include the following:

Connection of the Use Tax to the Property Tax Lien Date. Under Chapter 226, a nonresident owner of a vessel or aircraft is exempt from the use tax if the property is used outside of the state for more than six months during the first year. However, the vessel or aircraft is also presumed to be for use in California (and thus subject to the use tax) if it is subject to the property tax during the first 12 months of ownership. Thus, if a vessel owned by a nonresident is within a county on the January lien date, it would be subject to both the personal property tax and the use tax. While this linkage may help BOE establish use tax liabilities, we believe it creates a conflicting standard that could seriously disadvantage nonresidents that have fully met the out-of-state usage test, and yet find themselves subject to the use tax. Given this, the Legislature may wish to eliminate the provision in Chapter 226 which links the application of the use tax to the property tax.

Exemption for Fueling and Emergencies. As noted earlier, Chapter 226 includes an exemption from the use tax for vessels and aircraft for repair, retrofit, or modifications. The Legislature may wish to add similar exemptions for refueling and emergencies, since such activities do not necessarily imply regular usage in California.

Finally, the Governor has proposed that Chapter 226�s provisions be extended for one year. We believe that it would be preferable to permanently extend the key provisions of Chapter 226. The year-to-year extension of this tax law change would likely create behavioral incentives having negative consequences for both the industries involved and the state. As indicated above, there is some evidence that the July 2006 sunset date is starting to encourage the postponement of buying plans (as some prospective customers wait for the potential return of the 90-day test). This type of behavioral effect would likely continue if the expectation is that the one-year test will be in effect for just one additional year. We believe it would be preferable to settle the policy issues now and put in place a permanent set of standards so that buyers and sellers will know what the �ground rules� will be in the future.

|

Acknowledgments This report was prepared by Brad Williams, with contributions from David Vasch� and Mark Ibele, and data analysis by Robert Ingenito. The Legislative Analyst's Office (LAO) is a nonpartisan office which provides fiscal and policy information and advice to the Legislature. |

LAO Publications To request publications call (916) 445-4656. This report and others, as well as an E-mail subscription service, are available on the LAO's Internet site at www.lao.ca.gov. The LAO is located at 925 L Street, Suite 1000, Sacramento, CA 95814. |