February 12, 2015

The 2015-16 Budget:

Analysis of the Health Budget

Overview of Health Budget. The Governor’s budget proposes $21 billion from the General Fund for health programs—a 5 percent increase above 2014–15 estimated expenditures. For the most part, the year–over–year changes reflect implementation of previously enacted policy changes as well as changes in caseload, utilization of services, and costs as opposed to new policy proposals. The Governor’s budget proposal for health programs reflects significant fiscal uncertainty in a number of programmatic areas related to federal actions. For example, the President’s recent executive action on immigration would have a highly uncertain fiscal impact on health programs.

Programmatic and Spending Trends Since 2007–08. Our review of trends in the major health programs since 2007–08 (the last budget developed before the most recent recession) finds that total spending is up by 94 percent. By far the largest factor accounting for this growth in total spending is the increase in federal funding of $37.2 billion, in part reflecting the enhanced federal share of costs for the Medi–Cal expansion population under the federal Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA), also known as federal health care reform. While funding for some program reductions made during recessionary times has been fully or partially restored, other program reductions remain today. In addition, the Legislature has made some health program augmentations since 2007–08, mainly related to ACA implementation.

Proposed Restructuring of Managed Care Organization (MCO) Tax. A letter from the federal Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services indicates that taxes structured like California’s existing MCO tax are inconsistent with federal Medicaid law and regulations, thereby putting over $1 billion in federal funding to the state at risk in future years if the tax were extended in its current form. The Governor proposes a new MCO tax structure intended to comply with federal requirements while funding two objectives: (1) restoring service hours previously reduced in the In–Home Supportive Services Program and (2) maintaining the General Fund offset from the current impermissible tax. We find the Governor’s proposed MCO tax would likely meet federal requirements, but note that in doing so, the proposal would in part resemble an actual tax on commercial health coverage (in addition to being a typical Medi–Cal financing scheme to leverage federal funding), with broader economic and social implications. While we recommend the Legislature adopt core features of the Governor’s proposal by August 2015, we find that permanent authorization of the proposal in its current form is not warranted.

Federal Funding for Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) Uncertain. The amount of federal CHIP funding available in 2015–16 is uncertain, pending actions by Congress to appropriate additional funds for CHIP beyond September 30, 2015. Further, the longer–term future of CHIP remains uncertain as the federal government weighs the potential for transitioning children currently covered by CHIP into other sources of health coverage, such as subsidized coverage through Covered California. We recommend the Legislature begin weighing various options for children’s coverage should CHIP be discontinued.

Additional Capacity in Department of State Hospitals May Be Unnecessary. The Governor’s budget includes several proposals—including a $35.5 million capital outlay project—to expand treatment capacity for incompetent to stand trial patients in state hospitals. We find that the proposed increase in capacity may be unnecessary given recent policy changes and the department’s existing capacity. We recommend the Legislature not approve funding for the proposed capacity and request additional information from the department justifying the need for it in light of these concerns. To the extent the Legislature finds additional capacity to be necessary, we recommend the Legislature prioritize the most cost–effective options for providing services. We recommend that the Legislature reject the proposed capital outlay project due to its high cost.

Department of Public Health Licensing and Certification (L&C). Recent incidents of inconsistent and inadequate oversight, monitoring, and enforcement of L&C standards for health facilities have gained the attention of the media and the Legislature. In response, the Governor’s budget plan includes four proposals to take steps to improve the quality of the L&C Program and increase L&C staffing. We find the Governor’s approach of adding more resources to the L&C Program makes sense in order to address the backlog of L&C workload and complaint investigations. However, a key report from the administration is overdue, and without the report, the Legislature is not in a position to determine whether the Governor’s proposals are the most cost–effective approach to addressing workload backlog issues.

California’s major health programs provide a variety of health benefits to its citizens. These benefits include purchasing health care services, such as primary care, for qualified low–income individuals, families, and seniors and persons with disabilities (SPDs). The state also administers programs to prevent the spread of communicable diseases, prepare for and respond to public health emergencies, regulate health facilities, and achieve other health–related goals.

The health services programs are administered at the state level by the Department of Health Care Services (DHCS), Department of Public Health (DPH), Department of State Hospitals (DSH), the California Health Benefit Exchange (known as Covered California or the Exchange), and other California Health and Human Services Agency (CHHSA) departments. The actual delivery of many of the health care services provided through state programs often takes place at the local level and is carried out by local government entities, such as counties, and private entities, such as commercial managed care plans. (Funding for these types of services delivered at the local level is known as “local assistance,” whereas funding for state employees to administer health programs at the state level and/or provide services is known as “state operations.”)

Overview of Health Budget Proposal. The Governor’s budget proposes $21 billion from the General Fund for health programs. This is an increase of $992 million—or 5 percent—above the revised estimated 2014–15 spending level, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1

Major Health Programs and Departments—Budget Summary

General Fund (Dollars in Millions)a

|

|

2013–14 Actual

|

2014–15 Estimated

|

2015–16 Proposed

|

Change From 2014–15

|

|

Amount

|

Percent

|

|

Medi–Cal—Local Assistance

|

$16,488

|

$17,843

|

$18,610

|

$767

|

4.3%

|

|

Department of State Hospitals

|

1,463

|

1,563

|

1,576

|

13

|

0.8

|

|

Department of Public Health

|

115

|

120

|

124

|

4

|

3.3

|

|

Other Department of Health Care Services programs

|

60

|

169

|

268

|

99

|

58.6

|

|

High–cost medicationsb

|

—

|

100

|

200

|

100

|

100.0

|

|

Emergency Medical Services Authority

|

7

|

8

|

8

|

—

|

—

|

|

All other health programs (including state support)c

|

166

|

159

|

168

|

9

|

5.7

|

|

Totals

|

$18,299

|

$19,962

|

$20,954

|

$992

|

5.0%

|

Summary of Major Budget Proposals and Changes. The year–over–year increase of $992 million General Fund over the estimated 2014–15 spending level is largely comprised of increased expenditures in three areas. (We discuss each of these increases in more detail later in this report.)

- Medi–Cal Local Assistance. The net year–over–year increase in Medi–Cal local assistance of $767 million General Fund is due to several factors—including caseload adjustments, changes in benefits and utilization, and technical adjustments.

- High–Cost Drugs. The budget plan provides $100 million General Fund in 2014–15 and $200 million in 2015–16 to pay for new drugs used to treat Hepatitis C. These funds are not allocated to specific departments or programs, but are reserved for the state’s costs in treating some individuals infected with Hepatitis C—including inmates in state prisons, patients in state hospitals, and Medi–Cal and AIDS Drug Assistance Program beneficiaries.

- Backfill Reduced Federal Funds for Certain DHCS Family Health Programs. In response to an anticipated reduction in federal funds (used to support certain state–only programs) resulting from the expiration of the state’s current Section 1115 Medicaid waiver in October 2015, the budget plan proposes to increase General Fund support for the California Children’s Services program by $59 million and the Genetically Handicapped Persons Program by $51 million.

Budgetary Uncertainty Due to Federal Actions. The Governor’s budget proposal for health programs reflects significant fiscal uncertainty relating to federal actions in a number of programmatic areas. We describe the major uncertainties in Figure 2 and discuss them in greater detail later in this report.

Figure 2

Health Programs Budgetary Uncertainty Related to Federal Actions

|

Issue

|

Budgetary Uncertainty

|

|

Presidential executive action on immigration

|

If the President’s executive action is implemented, some undocumented immigrants may newly qualify for state health programs, including full–scope Medi–Cal. The potential cost increase to the state’s health services programs is highly uncertain.

|

|

Renewal of Medi–Cal managed care organization (MCO) tax

|

The state currently imposes a 3.9 percent tax on Medi–Cal MCOs’ gross receipts. This tax is used to leverage federal Medicaid funding. Recent federal guidance indicates that California’s tax on MCOs is inconsistent with federal Medicaid regulations and advised California—by no later than the end of this legislative session—to make changes to bring its tax structure into compliance. The budget assumes a General Fund offset from the tax of $803 million in 2014–15 and $1.1 billion in 2015–16. The budget would address this uncertainty by proposing a replacement tax that would comply with federal law.

|

|

Medi–Cal Section 1115 waiver renewal

|

California’s current Medi–Cal Section 1115 waiver, “Bridge to Reform,” expires in October 2015. The Department of Health Care Services will seek a five–year renewal of the waiver to continue to support implementation of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA), also known as federal health care reform, and other programmatic goals. The budget assumes continuation of some of the funding available in the current waiver. However, the federal Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services has indicated that some funding, such as federal fund support for certain state–only health programs, is unlikely to continue.

|

|

Federal reauthorization of Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) funding

|

Currently, federal funding for CHIP is only appropriated through federal fiscal year (FFY) 2015 which ends September 30, 2015, but ACA authorizes a higher level of CHIP federal funding beginning in FFY 2016. Congress must appropriate additional funds to continue CHIP and provide this higher level of funding. The budget assumes federal funding for CHIP will continue at the current level in 2015–16.

|

Members of the Legislature have expressed interest in the issue of the level of the state’s spending on health programs today compared to pre–recession levels (the 2007–08 state budget was the last budget developed before the recent recession). As with all areas of the budget, significant General Fund budget reductions were made in the health area to help balance the budget during the recessionary years. This section is intended to provide information to the Legislature to be able to make a meaningful comparison between (1) the state’s spending and programmatic service/benefit levels in health programs in the 2007–08 budget and (2) the level of spending and programmatic service/benefit levels for such programs proposed in the 2015–16 Governor’s Budget. We discuss caseload trends, changes in how programs are funded, changes in eligibility and service/benefit levels, and other drivers, such as federal policy changes—all of which help explain the difference between 2007–08 and 2015–16.

California’s state–federal Medicaid program, known as Medi–Cal, is a major source of health coverage for millions of Californians, and is by far the largest state–administered health program in terms of annual caseload and expenditures. Medi–Cal has undergone a major programmatic transformation as a result of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA), that has resulted in a major influx of new federal funding to provide health coverage to a newly eligible Medi–Cal population. There has also been some expansion of Medi–Cal health benefits under ACA. Throughout this section, as we discuss these various changes to Medi–Cal, we assume some basic familiarity with the program’s financing and delivery. To obtain this background information, see the “Medi–Cal” section of this report.

As shown in Figure 3, when all funding sources flowing through the state budget are considered (including federal funds), total spending in health programs has grown by 94 percent between 2007–08 and the Governor’s 2015–16 budget proposal. In real (inflation–adjusted) terms, total spending in health programs has grown by 75 percent from 2007–08 to 2015–16. Total spending was adjusted for inflation using the gross domestic product price index. This adjusts for economywide inflation, providing an indication of how the amount of state and federal resources devoted to spending in health programs has changed from 2007–08 to 2015–16 in real dollars. This adjustment does not account for many other factors specific to health spending, such as the population served, benefit design, technological changes, and the growth in health care prices above overall price inflation.

Figure 3

Health State Budget: Pre–Recession Versus 2015–16 Proposal

(Dollars in Billions)

|

Fund Source

|

2007–08 Actual

|

2015–16 Proposed

|

Change From 2007–08 to 2015–16

|

|

Amount

|

Percent

|

|

General Fund

|

$17.4

|

$21.0

|

$3.6

|

21%

|

|

Federal fundsa

|

20.2

|

57.4

|

37.2

|

184

|

|

Realignment revenues

|

2.8

|

3.5

|

0.7

|

25

|

|

Other special funds

|

6.9

|

10.0

|

3.1

|

45

|

|

Totals (All Funds)

|

$47.3

|

$91.9

|

$44.6

|

94%

|

By far the largest factor accounting for the growth in total spending between 2007–08 and 2015–16 is the increase in federal funding of $37.2 billion, in large part reflecting the enhanced federal share of costs for the Medi–Cal expansion population under ACA. We note that embedded in the total spending increase over this period are some other changes in how health programs are funded. For example, in 2011–12 and 2013–14, costs for certain health programs were realigned to the counties resulting in lower General Fund costs for the state. The Legislature also implemented a tax on managed care organizations (MCOs) that: (1) increases Medi–Cal managed care rates by an amount that offsets the tax paid by MCOs and (2) funds state health programs.

The growth in total spending for health programs between 2007–08 and 2015–16 was largely driven by the implementation of ACA, which was enacted in 2010. However, prior to that time, the Legislature enacted a number of significant spending reductions in the health area in response to declining state revenues brought about by the recession. We briefly turn to a discussion of them now, before focusing our attention on how ACA has transformed the state’s health programs.

Here we provide a high–level overview of major reductions that have been the focus of recent legislative budget hearings. Most of these reductions were made in 2008–09 and 2009–10—in response to the recession and the state’s budget problem—and some remain in effect.

Reduced Some Payments to Medi–Cal Providers. The Legislature and Governor took some significant actions regarding provider rates during a February 2008 special legislative session held to address the state’s fiscal crisis. Legislation enacted at that time, Chapter 3, Statutes of 2008 (ABX3 5, Committee on Budget), reduced most Medi–Cal provider rates by 10 percent as of July 1, 2008, for an estimated savings of $291 million. Some Medi–Cal provider groups challenged the legality of these rate reductions in court, and on August 18, 2008, a federal judge issued an injunction blocking enforcement of these rate reductions for certain types of services provided on or after that date. The state later prevailed in court. While funding for some of the rate reductions was fully or partially restored for certain types of providers, most rate reductions remain in effect.

Eliminated Some Optional Medi–Cal Benefits. The February 2009 budget package eliminated certain optional benefits for adults effective July 2009 for savings of $122 million General Fund. The bulk of the savings came from the elimination of adult dental services, which were later partially restored at an estimated annual cost of $85 million General Fund. However, savings continue from the elimination of incontinence creams and washes, acupuncture, and other services.

Reduced Public Health Spending. In 2008–09, through a combination of legislative actions ($43 million General Fund) and Governor’s veto ($16 million General Fund) a total of $59 million General Fund was cut from various public health programs. In 2009–10, the budget further reduced General Fund spending on public health programs by a total of $154.2 million General Fund ($80.4 million General Fund from Governor’s veto). The major public health programs affected by this reduction were: (1) HIV/AIDS programs; (2) Maternal, Child and Adolescent Health program; (3) domestic violence shelters; and (4) immunization local assistance. Most of these reductions remain in effect although the 2014–15 budget restores $7 million General Fund for the Black Infant Health Program and HIV demonstration projects.

In 2010, the ACA became law. This is far–reaching legislation intended to provide increased access to health care. In part, the ACA is designed to create a health coverage purchasing continuum that makes it easier for persons to access, purchase, and maintain coverage. As individuals’ incomes rise and fall; as they become employed, change employers, or become unemployed; and as they age, they are to have access to different sources of coverage along the continuum. Since the passage of ACA, the Legislature has dedicated significant time and resources towards its implementation.

Establishment of a Health Benefit Exchange. Chapter 655, Statutes of 2010 (AB 1602, J. Perez), and Chapter 659, Statutes of 2010 (SB 900, Alquist and Steinberg), established the California Health Benefit Exchange, known as Covered California, along with a governing board. Through Covered California, individuals and employees of small businesses (50 employees or less) that choose to offer coverage through Covered California are able to enroll in subsidized and unsubsidized health coverage. Covered California provides federally funded tax subsidies to keep the cost of health coverage affordable for eligible individuals. Coverage offered through Covered California must include a minimum set of benefits, known as the “essential health benefits.”

The ACA implementation has had many different fiscal effects—some major and some minor—associated with implementing various provisions of state and federal law related to ACA. Here we describe the major effects.

Major Investments With Federal Support to Prepare for Implementation. In November 2010, the state secured a five–year agreement with the federal government to receive significant funding and support for the state’s preparations to implement the ACA. This agreement is known as the Bridge to Reform Section 1115 waiver. (In general, Section 1115 waivers allow states to operate demonstration projects that further the goals of the Medicaid program.) By demonstrating that changes under the waiver would be budget–neutral to the federal government, the state has drawn down over $10 billion in additional federal funding over the five–year span of the waiver. Among the major uses of these funds were (1) early initiatives—overseen by counties—to provide coverage to populations that would become newly eligible for Medi–Cal under the ACA, (2) incentive payments for public hospitals to improve and ready their health systems for these incoming enrollees, and (3) offsets to state spending for certain state–only health programs. The waiver was also the main vehicle for obtaining federal approval to shift various Medi–Cal populations into the managed care system, which we describe below. The Bridge to Reform waiver expires in November 2015, and the state is currently preparing to submit its proposal for a new waiver.

Expanded Eligibility and Enrollment. Under the ACA, beginning January 1, 2014, California expanded Medi–Cal eligibility to include over 1 million adults with incomes up to 138 percent of the federal poverty level (FPL). This is known as the optional expansion. For three years the federal government will pay 100 percent of the costs of health care services provided to the newly eligible population. Beginning January 1, 2017, the federal share of costs associated with the expansion will be decreased over a three–year period until the state pays for 10 percent of the expansion and the federal government pays the remaining 90 percent. The estimated cost in 2015–16 for providing Medi–Cal services to the roughly 2 million persons who will enroll in the program under the optional expansion is $14.3 billion (all federal funds except for $7.5 million General Fund).

Several factors—such as enrollment simplification, publicity, and outreach—will increase Medi–Cal enrollment among individuals who were previously eligible, but unenrolled—often referred to as the mandatory expansion. Generally, the state will continue to be responsible for 50 percent of the costs of providing services to mandatory expansion enrollees. The estimated cost in 2015–16 for providing Medi–Cal services to the roughly 1 million persons who will enroll in the program under the mandatory expansion are $2 billion total funds ($961 million General Fund). See the “Medi–Cal” section of this report for more information on this ACA–related caseload.

Made It Easier to Enroll and Remain Covered. The ACA and recent state legislation contain several provisions that are expected to simplify Medi–Cal eligibility and streamline the enrollment and redetermination processes, including:

- ACA Simplified Methodology Used to Determine Financial Eligibility. The ACA generally simplified the standards used to determine financial eligibility for most beneficiaries—excluding certain populations, such as SPDs. The two major changes to the methodology include requiring the use of Modified Adjusted Gross Income (MAGI) to calculate income and not requiring asset tests.

- Use of Electronic Data to Verify Eligibility. Pursuant to the ACA, many pieces of information needed to determine an applicant’s eligibility are required to be verified electronically by accessing existing state and federal databases. Consumers are only to be asked to provide physical verification of eligibility if reasonably compatible electronic verification is not available.

- “No Wrong Door” Approach for Applications. The state adopted a no wrong door approach for Medi–Cal applications. This allows applicants to apply: online through Covered California’s website, by calling either Covered California’s service center or county Medi–Cal eligibility offices, in person at county Medi–Cal eligibility offices, or through the mail.

- Other Streamlined Enrollment Processes. The state has also taken advantage of other options under the ACA to streamline the enrollment process, including hospital presumptive eligibility and express lane enrollment. Both are streamlined processes that allow certain individuals to enroll in Medi–Cal without completing a full application.

- Simplified Annual Redeterminations. The ACA and state legislation created a new annual redetermination process that reduces the amount of information that must be provided by beneficiaries and, instead, relies on available electronic data.

The combined effect of all of the changes described above to simplify Medi–Cal eligibility and streamline the enrollment and redetermination processes is to make it easier for Medi–Cal enrollees to obtain and maintain coverage. This has likely increased enrollment and associated spending in the program.

Since 2007–08, managed care has overtaken and surpassed fee–for–service (FFS) as the primary Medi–Cal service delivery system. While managed care has covered the majority of Medi–Cal enrollees for over a decade, until recently, the majority of General Fund spending was in FFS. This was because the most expensive populations and services—such as SPDs and long–term services and supports (LTSS)—remained in FFS.

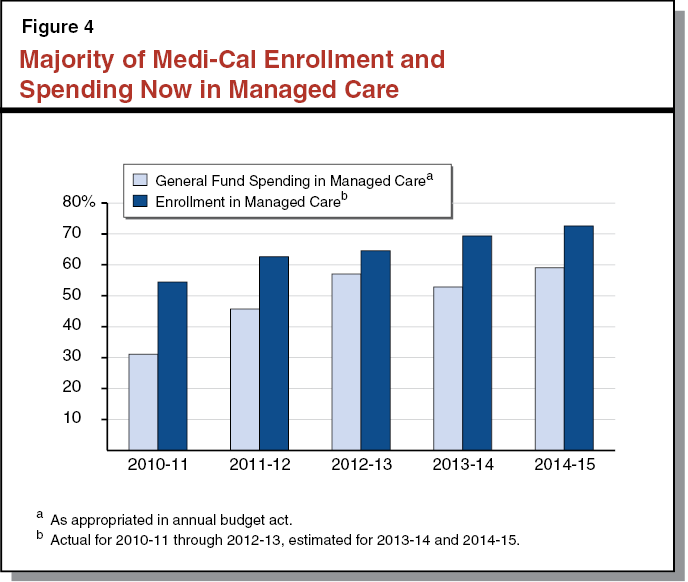

As Figure 4 shows, the bulk of both General Fund spending and enrollment has shifted from FFS to managed care. This is the result of a series of policies to move various groups of beneficiaries and services from FFS and managed care, often (but not always) via mandatory enrollment. From the state’s perspective, the major goals of these transitions have been to (1) improve care quality, efficiency, and access for the affected populations; and (2) provide budgetary predictability via capitated rate–setting. Below, we highlight the most significant Medi–Cal managed care transitions from the past five years.

Shift of Medi–Cal–Only SPDs to Managed Care. The first major transition occurred from June 1, 2011 through May 2012, when the state shifted 240,000 Medi–Cal–only SPDs (that is, SPDs who do not also receive coverage under Medicare) from FFS to Medi–Cal managed care in 16 counties.

Rural Expansion. From September to November 2013, the state expanded Medi–Cal managed care into 28 counties where managed care did not previously exist—generally rural counties. This first wave of the rural managed care expansion covered over 400,000 enrollees from the families and children population. In December 2014, the state began to shift 20,000 Medi–Cal–only SPDs in 19 of these rural counties into managed care.

Coordinated Care Initiative (CCI). The 2012–13 budget package authorized CCI as an eight–county demonstration project consisting of three main components: (1) integrating Medi–Cal and Medicare benefits for SPDs who are enrolled in both programs—known as “dual eligibles”—under the same managed care plans, (2) requiring mandatory enrollment of dual eligibles into managed care for their Medi–Cal benefits (dual eligibles are passively enrolled into these plans for Medicare benefits, meaning they will be enrolled unless they actively opt out), and (3) making LTSS available exclusively through managed care. Up to 426,000 dual eligibles are eligible for passive enrollment into the Medi–Cal–Medicare portion of the demonstration. Enrollment for CCI began in April 2014 and will continue through January 2016.

As described earlier, the Legislature eliminated certain Medi–Cal benefits during the economic downturn. However, the Legislature also has taken action since 2007–08 to add new benefits to the Medi–Cal program, particularly in the area of behavioral health. In many cases, the Legislature expanded these benefits as part of the state’s broader implementation of the ACA.

Alignment of Essential Health Benefits With Medi–Cal Benefits. Some non–specialty mental health and substance use disorder Medi–Cal benefits were enhanced to make them comparable to the essential health benefits provided by plans offered through Covered California. Aligning Medi–Cal benefits with the essential health benefits helps ensure that low–income persons moving back and forth between Medi–Cal and health coverage offered through Covered California will continue to receive comparable benefits as they move between sources of coverage. As of January 1, 2014, Medi–Cal managed care plans provide these non–specialty mental health and substance use disorder services to eligible Medi–Cal enrollees. (Specialty mental health services are provided through county mental health plans and other substance use disorder services are provided through Drug Medi–Cal [DMC]). The budget includes $276 million General Fund in 2015–16 to provide these services.

Behavioral Health Treatment (BHT). As of September 15, 2014, Medi–Cal managed care plans are required to provide medically necessary BHT services to eligible children and adolescents up to age 21 with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD). The budget includes $151 million General Fund in 2015–16 for the provision of BHT services. This benefit and its associated costs are discussed further in the “Medi–Cal” section of this report.

DMC Waiver Changes. The DHCS is currently seeking a DMC Organized Delivery System Waiver from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). This waiver seeks to demonstrate that organized substance use disorder care improves outcomes for DMC beneficiaries. Counties that opt–in to the waiver would provide a continuum of care to DMC beneficiaries and would provide additional benefits that are not available currently, such as residential treatment services. We note that the state is currently awaiting approval from CMS prior to implementing these changes. The budget includes $19.6 million General Fund to provide residential treatment services under this waiver in 2015–16. No other General Fund costs associated with the waiver are assumed in the budget.

Beginning mostly in 2012–13, the Legislature enacted legislation to eliminate three state departments and shift programmatic and administrative responsibility for several programs between departments. Generally, programs that provide health care services, such as treatment for illnesses, have been shifted from other departments to DHCS. The policy rationale for making some of these shifts is to allow DHCS to better integrate the physical health care provided by Medi–Cal with the care provided by other programs and identify administrative efficiencies by placing the state–level administration of programs that purchase health care services all within the same department. In addition, the policy rationale for shifting the DMC benefit and specialty mental health services (both Medi–Cal benefits formerly administered by other departments) to DHCS is to allow DCHS to better integrate substance use programs and specialty mental health care with the physical health care provided through Medi–Cal. Overall, the effect is to consolidate programs within fewer departments. The net overall fiscal effect of the department eliminations and program shifts is largely budget neutral. The major departmental eliminations and programmatic shifts were:

- Managed Risk Medical Insurance Board (MRMIB). The MRMIB was eliminated effective July 1, 2014. In 2012–13 and 2013–14, enrollees in California’s federal Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), known as the Healthy Families Program (HFP), were shifted from HFP into Medi–Cal. Effective July 1, 2014, MRMIB was eliminated and programmatic and administrative responsibility for the remaining three programs administered by MRMIB (Major Risk Medical Insurance Program, Access for Infants and Mothers, and County Health Initiative Matching Fund Program) were shifted from MRMIB to DHCS.

- Department of Alcohol and Drug Programs (DADP). The DADP was eliminated effective July 1, 2013. State–level oversight of the DMC program was shifted from DADP to DHCS effective July 1, 2012. The DADP’s other programmatic and administrative responsibilities were transferred to other departments effective July 1, 2013.

- Department of Mental Health (DMH). The DMH was eliminated effective July 1, 2012. The DSH was created to administer the state hospitals, in–prison programs, and the conditional release program. State–level oversight for the bulk of community mental health programs, such as Medi–Cal specialty mental health services and Proposition 63 activities, was shifted from DMH to DHCS during 2011–12. Programmatic and administrative responsibility for the remaining DMH programs were transferred to various departments.

- Direct Health Care Service Programs Shifted From DPH to DHCS. Effective July 1, 2012, the budget plan transferred the following programs from DPH to DHCS: (1) Every Woman Counts, (2) Family Planning Access and Treatment, and (3) the Prostate Cancer Treatment Program. All of these programs provide direct health care services, similar to direct health care provided through other programs administered by DHCS.

The implementation of ACA has been the primary driver behind the expansion of health programs in California between 2007–08 and 2015–16. In particular, the Medi–Cal program, by far California’s largest health program in terms of enrollment and funding, has been subjected to a major programmatic transformation under ACA. Accordingly, our summary of the main takeaways from our analysis of programmatic and spending trends in the major health services programs since 2007–08 is focused on Medi–Cal as follows:

- Spending Up Significantly, Funding Mix Changed. While total spending has gone up by about 94 percent, there have been changes in how programs have been funded. Specifically, the amount of federal funds, as a percent of total health spending, has increased from 43 percent in 2007–08 to 62 percent in 2015–16. This is mainly due to increases in federal funding for Medi–Cal provided under ACA.

- Caseload Up. Caseload in the state’s Medi–Cal program has increased from 6.6 million in 2007–08 to 12.2 million in 2015–16. Major factors contributing to this increase in caseload include: (1) the shift of over 750,000 from the state’s CHIP, formerly known as HFP, to Medi–Cal; (2) the enrollment of an estimated 2 million newly eligible persons under the optional expansion; (3) the enrollment of an estimated 1 million previously eligible persons under the mandatory expansion, and; (4) the simplification of Medi–Cal eligibility determination criteria and the streamlining of enrollment and eligibility redetermination processes.

- Some Reductions Continue, but There Have Also Been Augmentations. There were a number of programmatic reductions made during the recessionary period. While funding for some of these reductions has been fully or partially restored, several of the reductions continue today. For example, certain optional benefits and provider rate reductions have not been restored. On the other hand, mainly as part of ACA implementation, there have been a number of program augmentations since 2007–08. Generally, these augmentations, such as adding new Medi–Cal managed care benefits, have been intended to align state program benefits, enrollment systems, and eligibility requirements in order to create a continuum of health care services for persons obtaining health insurance through public health care services programs such as Medi–Cal and Covered California.

In California, the federal–state Medicaid program is administered by DHCS as the California Medical Assistance Program (Medi–Cal). Medi–Cal is by far the largest state–administered health services program in terms of annual caseload and expenditures. As a joint federal–state program, federal funds are available to the state for the provision of health care services for most low–income persons. Until recently, Medi–Cal eligibility was mainly restricted to low–income families with children, SPDs, and pregnant women. As part of the ACA, beginning January 1, 2014, the state expanded Medi–Cal eligibility to include additional low–income populations—primarily childless adults who did not previously qualify for the program.

Financing. The costs of the Medicaid program are generally shared between states and the federal government based on a set formula. The federal government’s contribution toward reimbursement for Medicaid expenditures is known as federal financial participation (FFP). The percentage of Medicaid costs paid by the federal government is known as the federal medical assistance percentage (FMAP).

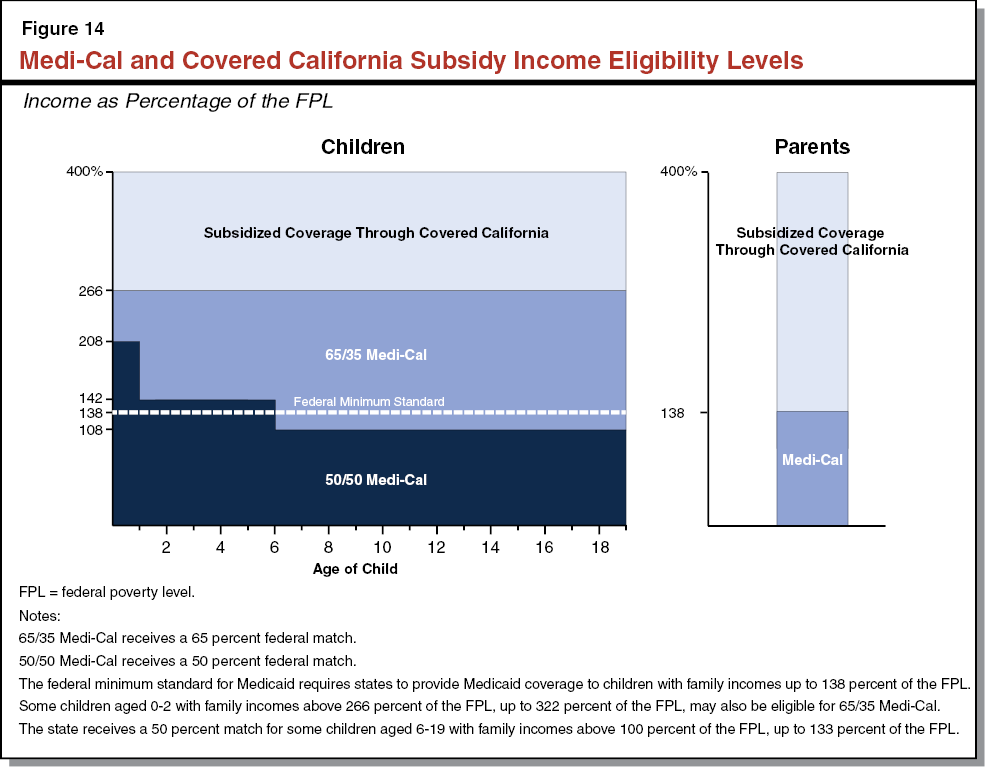

For most families and children, SPDs, and pregnant women, California generally receives a 50 percent FMAP—meaning the federal government pays one–half of Medi–Cal costs for these populations. However, a subset of children with higher incomes qualify for Medi–Cal as part of the state’s CHIP. Currently, the federal government pays 65 percent of the costs for children enrolled in CHIP and the state pays 35 percent. Finally, under the ACA, the federal government will pay 100 percent of the costs of providing health care services to the newly eligible Medi–Cal population from 2014 through 2016; the federal matching rate will phase down to 90 percent by 2020 and thereafter.

Delivery Systems. There are two main Medi–Cal systems for the delivery of medical services: FFS and managed care. In a FFS system, a health care provider receives an individual payment from DHCS for each medical service delivered to a beneficiary. Beneficiaries in Medi–Cal FFS generally may obtain services from any provider who has agreed to accept Medi–Cal FFS payments. In managed care, DHCS contracts with managed care plans, also known as health maintenance organizations, to provide health care coverage for Medi–Cal beneficiaries. Managed care enrollees may obtain services from providers who accept payments from the managed care plan, also known as a plan’s “provider network.” The plans are reimbursed on a “capitated” basis with a predetermined amount per person, per month regardless of the number of services an individual receives. Medi–Cal managed care plans provide enrollees with most Medi–Cal covered health care services—including hospital, physician, and pharmacy services—and are responsible for ensuring enrollees are able to access covered health services in a timely manner. (In some counties, Medi–Cal managed care plans also provide LTSS, including institutional care in skilled nursing facilities [SNFs], and home– and community–based services.) The number and type of managed care plans available vary by county, depending on the model of managed care implemented in each county. Counties can generally be grouped into four main models of managed care:

- County Organized Health System (COHS). In the 22 COHS counties, there is one managed care plan available to beneficiaries that is run by the county.

- Two–Plan. In the 14 Two–Plan counties, there are two managed care plans available to beneficiaries. One plan is run by the county and the second plan is run by a commercial health plan.

- Geographic Managed Care (GMC). In GMC counties, there are several commercial health plans available to beneficiaries. There are two GMC counties—San Diego and Sacramento.

- Regional. Finally, in the Regional model, there are two commercial health plans available to beneficiaries across 18 counties.

Imperial and San Benito Counties have managed care plans that do not fit into one of these four models. In Imperial County, there are two commercial health plans available to beneficiaries and in San Benito, there is one commercial health plan available to beneficiaries.

According to the Medi–Cal Eligibility Data System (MEDS), there were over 11 million people enrolled in Medi–Cal as of September 2014. This count includes 2 million enrollees—mostly childless adults—who became newly eligible for Medi–Cal under the optional expansion. A substantial number of families and children who were previously eligible—known as the mandatory expansion—are also assumed to have enrolled as a result of eligibility simplification, enhanced outreach, and other provisions and effects of the ACA. The Governor’s budget assumes that following the large influx of enrollees in 2014–15, ACA–related caseload levels will stabilize during 2015–16. The budget also assumes modest underlying growth for baseline enrollment within the families and children and SPD populations. Below, we briefly review the administration’s methodology for forecasting Medi–Cal caseload to provide background and context for our assessment of these projections.

Base Forecast. The DHCS builds its total caseload estimate for Medi–Cal by separately estimating, then combining, two distinct forecasts. The first forecast is known as the base. The base relies on historical trends from actual enrollment data in MEDS. (For the Governor’s January budget proposal, the base reflects MEDS data that is current through August 2014.) The department studies movements in caseload from past periods, then applies statistical techniques to extrapolate future trends from these patterns. The base represents DHCS’ view of the underlying trend—that is, how caseload would evolve absent major shifts (such as the HFP transition) and policy changes in the program.

Policy Change Forecast. The second type of forecast estimates the effect of the aforementioned shifts and policy changes. These policy changes generally consist of new proposals in the Governor’s budget, or enacted policies that DHCS determines are too new or complex to be reliably reflected in the base, mainly due to insufficient historical enrollment data. In particular, policies with long and complicated implementation schedules—or wide–ranging effects that may take years to stabilize—are likely to be estimated through DHCS’s policy change forecast, at least over several budget cycles. When DHCS analysts forecast policy changes, they typically do not use the formal statistical techniques that characterize the base. Instead, each policy change estimate relies on the analyst’s assumptions, judgment, and information obtained outside of formal statistical modeling.

Administration Continues to Project ACA Caseload Mainly Through Policy Change Forecast. The Governor’s budget contains no new policy proposals that are assumed to affect Medi–Cal caseload. Instead, all major policy changes that impact the caseload estimate outside of the base are associated with ongoing provisions and effects of the ACA. There were eight months of post–ACA enrollment data (January through August 2014) available to DHCS at the time of the budget’s preparation. The DHCS indicated that despite additional data, ACA–related enrollment trends have not stabilized enough to be fully incorporated into statistical modeling for the base.

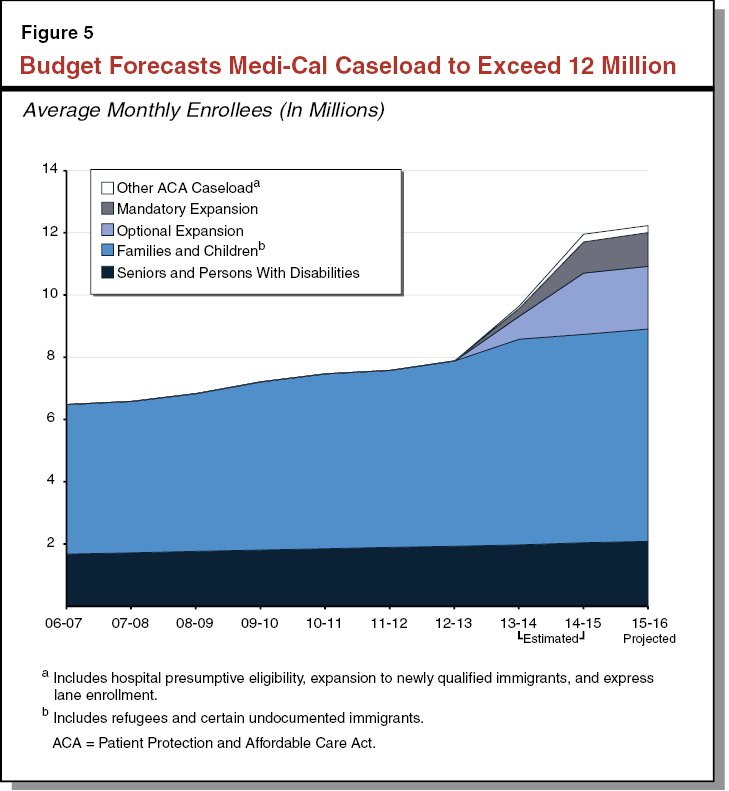

Figure 5 displays a decade of observed and estimated caseload for each major category of enrollment in Medi–Cal, beginning with (1) historical caseload through 2012–13, followed by (2) the administration’s revised estimate for caseload in 2013–14, and (3) the budget’s projections for 2014–15 and 2015–16. The families and children caseload grew at 4 percent annually between 2006–07 and 2010–11 (the onset of the Great Recession through the sluggish phase of the recovery), while SPD enrollment grew at about 2 percent annually over the same period. The further uptick in families and children through 2013–14 reflects the shift of HFP to Medi–Cal. Between January and November 2013, this transition added over 750,000 children to Medi–Cal’s caseload. (Later, we show that absent the HFP transition, the underlying trend for families and children caseload actually flattened in 2012–13.) Later, we take a closer look at these underlying trends prior to ACA implementation, and how they compare to the administration’s outlook for 2014–15 and 2015–16.

The Governor’s budget assumes total annual Medi–Cal caseload of 12.2 million for 2015–16. This is a 2 percent increase over the revised caseload estimate of 12 million for 2014–15. As noted earlier, the administration continues to isolate the ACA’s effect through its policy change forecast. Below, we break out the Governor’s caseload projections by the portion associated with ACA–related policies, and the remaining portion that is mainly captured in DHCS’s base forecast.

ACA Caseload. The budget assumes that compared to 2013–14—which reflected the first six months of implementation for ACA–related expansions—the combined annual caseload from the optional and mandatory expansions will have tripled in 2014–15. Following this steep climb, the budget assumes that in 2015–16, the optional and mandatory expansions will remain flat at 2 million and 1 million enrollees, respectively. The budget estimates that combined caseload from other ACA–related policies, such as express lane enrollment and hospital presumptive eligibility, will be 250,000 in 2014–15 and 220,000 in 2015–16.

Non–ACA Caseload. The administration projects that annual Medi–Cal caseload in the base forecast—absent the effects of the ACA—will be 8.8 million in 2014–15 and 8.9 million in 2015–16—a 2 percent year–over–year increase. Between the two years, the budget also implies that the underlying trend for both SPDs and families and children is 2 percent growth.

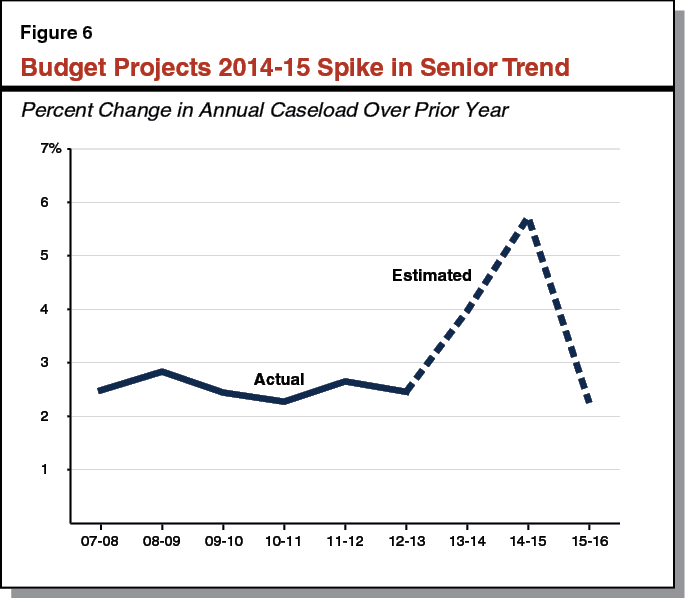

Senior Trend Raises Questions. Figure 6 displays historical annual growth rates for Medi–Cal’s senior caseload (enrollees aged 65 and older), followed by the administration’s estimated growth trend from 2013–14 onward. The DHCS projects the senior caseload to increase 5.7 percent in 2014–15, yet only 2.3 percent in 2015–16. According to the department, MEDS data through August shows senior enrollment being considerably higher than was assumed under the 2014–15 Budget Act. The department also indicated that the estimated spike in 2014–15 may reflect the delay in Medi–Cal redeterminations that occurred from January through June 2014 and the modified renewal process that occurred from July through December 2014. (Under the modified process, counties maintained eligibility for all enrollees who submitted a completed renewal form, regardless of whether these enrollees actually continued to meet eligibility criteria.) These policies may have led to more seniors staying enrolled in Medi–Cal than would have otherwise been the case.

The spike has a material impact on spending in 2014–15. Most seniors enrolled in Medi–Cal are dually eligible for Medi–Cal and Medicare. For 2014–15, the budget’s updated estimate of the number of dual eligibles enrolled in the Medicare prescription drug benefit is higher by 5 percent, leading to a $95 million increase in General Fund spending compared to the 2014–15 Budget Act. (The state makes monthly payments to the federal government for providing Medicare prescription drug coverage to dual eligibles.)

In terms of underlying trends, seniors represent the fastest–growing segment of Medi–Cal caseload, due to the state’s large cohort of baby boomers passing age 65. Over the two–year period, DHCS’s implied annual growth rate for seniors is 4 percent, which is more in line with our expectations. As suggested by the department, the delay in redeterminations, modified renewal process, or other temporary factors could explain the 2014–15 spike as a one–time anomaly. However, without more current data on enrollment, we cannot rule out the other possibility that the spike could signal an upward shift in the underlying trend for seniors, due to demographic changes or other fundamental factors.

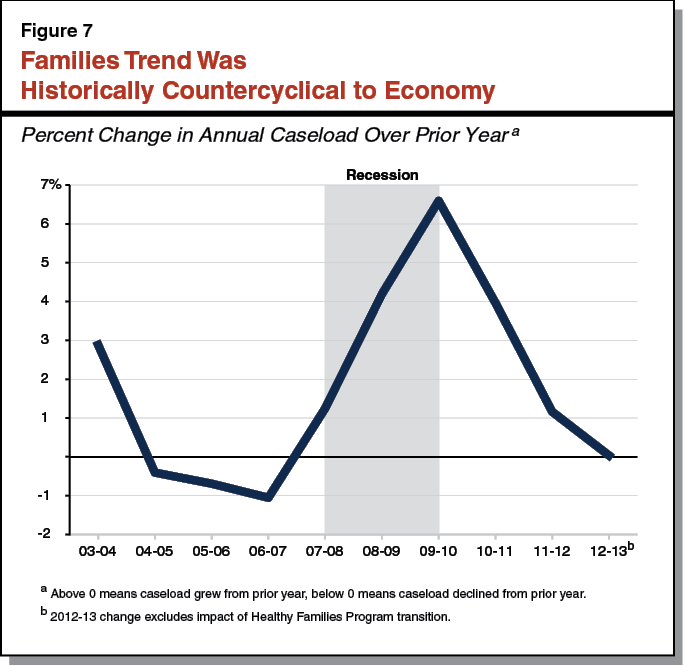

Assumes Underlying Growth for Families and Children, Despite Improving Economy. Excluding the caseload associated with the ACA, the budget implies 1 percent growth in base caseload for families and children in 2014–15, rising to 2 percent growth in 2015–16. However, Figure 7 shows that prior to the ACA, Medi–Cal enrollment among families and children moved countercyclical to the economy. (This means that families enrollment tends to go up during an economic downturn and go down during an economic expansion.) We note that caseload for California Work Opportunity and Responsibility to Kids (CalWORKS)—a means–tested program that overlaps with Medi–Cal in terms of the families enrolled—has declined steadily since 2011–12. (For more information on the CalWORKS budget, see our report The 2015–16 Budget: Analysis of the Human Services Budget.)

As stated in our November report The 2015–16 Budget: California’s Fiscal Outlook, we expect the underlying trend for Medi–Cal’s families caseload (absent ACA impacts) to transition to a slight decline as the economy expands. Historically, there has usually been some lag between the onset of an economic recovery and a turning point in the families caseload for Medi–Cal. However, the economy is well into the sixth year of the current expansion. All else equal, we would have expected the underlying trend for families to be declining—particularly since the trend showed signs of leveling off just prior to the beginning of ACA–related enrollment.

Budget staff at DHCS indicated that they, too, expect the families trend to slow and reverse if the economy continues to strengthen. Nonetheless, their approach is to maintain a modest growth rate in the base model for the families caseload until the MEDS data shows clear signs of a downward trend. If an obvious turning point occurs, they will adjust their base model. This “wait–and–see” approach is a conservative approach driven in part by the administration’s desire to avoid a deficiency in the program. For example, projecting a 1 percent decline rather than a 2 percent increase for the underlying trend would translate into 200,000 fewer enrollees in the families category, or about $240 million less in General Fund appropriations for 2015–16 (assuming a 50 percent federal matching rate). However, as described later, interpreting the underlying trend in the current data is very difficult given the ACA–related mandatory expansion.

ACA Caseload Estimates Subject to Uncertainty. The ACA–related caseload increase that occurred in 2014–15 was much larger than expected. While some data are available regarding ACA–related caseload, the ACA is a major policy change, and additional months of data are necessary to further clarify these enrollment trends. As noted earlier, according to MEDS data, there were over 2 million people enrolled through the optional expansion as of September 2014. This is higher than initial estimates of the total population eligible for the optional expansion. Therefore, we find the administration’s assumption that the optional expansion population will remain relatively flat at just over 2 million in 2015–16 to be reasonable. However, we find the mandatory expansion estimates to be more uncertain, as it is no longer possible to parse out this population in MEDS data. We discuss this in more detail immediately below.

Unpacking the Mandatory Expansion Estimate. Families and children newly enrolled in Medi–Cal as of January 1, 2014 were enrolled through the simplified eligibility criteria required by ACA (referred to as “MAGI standards”). In developing the caseload estimate that was adopted in the June 2014 budget, DHCS identified previously eligible families and children in the MEDS data as being part of the mandatory expansion population on the basis of being enrolled in Medi–Cal through MAGI standards. The department used its policy change forecast to project enrollment growth for these mandatory expansion families and children. Families and children who were enrolled prior to 2014 and had not yet gone through a redetermination, could be identified in the MEDS data as having been enrolled through pre–ACA eligibility criteria. These pre–ACA families and children remained in the base forecast, where DHCS applied its modest growth trend. However, as of January 1, 2014, most families and children who undergo a Medi–Cal eligibility renewal will be eligible under the post–ACA MAGI standards. This means it is no longer possible to distinguish families and children who enrolled post–ACA with those who were enrolled before the ACA. Thus, in the 2015–16 budget, DHCS was forced to incorporate all families and children, including those enrolled under MAGI standards, into the base data.

To account for this change, the DHCS states that for the 2015–16 budget proposal, 65 percent of the caseload estimate for the mandatory expansion is now reflected in the base. However, the budget still forecasts the total caseload estimate for the mandatory expansion using its policy change forecast. This has key implications.

- Underlying Trend for Families and Children May Be Decreasing. The underlying trend for families and children caseload could well be decreasing as the economy gains traction. Even if so, it may be impossible to tell as Medi–Cal coverage for more individuals is renewed through MAGI standards, blurring the distinction between first–time and renewing applicants. The DHCS’s default assumption for base families caseload is modest growth, and it appears that the department will maintain this trend as long as the ACA continues to add more enrollees to the base and obscures any signs of an underlying turning point.

- Mandatory Expansion Designation May No Longer Be Appropriate. The “mandatory” designation may have made sense at the early stages of ACA–driven enrollment. However, the label now seems arbitrary, as both pre–ACA and post–ACA families and children are enrolled through MAGI standards. The logic behind independently projecting the mandatory expansion in the policy change forecast is hard to follow and may be increasingly removed from reality.

We withhold recommendation on the administration’s caseload estimates at this time. We have outlined a number of issues that prevent us from getting a clear reading of the underlying trend for major categories of enrollment. While uncertainty is inherent in all caseload estimates—and not by itself a reason to withhold recommendation—normally we would have had a sense of the trend’s overall direction to comment on whether the administration’s assumptions seemed reasonable. Part of this was due to our ability to draw from sources of enrollment data outside the budget estimate. As described below, this supplementary information is no longer available to us.

Our overall advice for the Legislature is to wait for the May Revision, which will incorporate MEDS data through February 2015. By then, a number of issues complicating the 2014 data—such as the effect of the redetermination delay and modified renewal process—should be significantly (though not entirely) mitigated. Meanwhile, we have recommendations on how the Legislature can improve the state of available caseload information leading up to the May Revision.

Require Administration to Resume Monthly Caseload Reports. Prior to 2014, DHCS released monthly reports on Medi–Cal caseload levels and trends. Although these reports came with certain caveats, they were useful for keeping abreast of the overall direction of statewide Medi–Cal enrollment. In March 2014, DHCS stated that “[a]mid the initial stages of implementing the [ACA], current Medi–Cal enrollment information is volatile and initial datasets may provide misleading information.” The department went on to announce the temporary suspension of its monthly caseload reports. Since that time, the department has also indicated that it is working through its internal procedures to comply with federal health data privacy rules and ensure that any data released is sufficiently aggregated.

Nearly a year later, DHCS has not resumed any regular reporting on actual caseload. In lieu of these updates, the only publicly available documents on total and categorized Medi–Cal enrollment are the Governor’s biannual budget estimates. In this analysis, we are limited to citing preliminary MEDS data from September 2014. We obtained this data near the end of October by submitting a special request to DHCS.

Caseload data is fundamental to estimating the financing and delivery costs of health and human service programs. (We note that the Department of Social Services posts monthly caseload updates for CalWORKS on its website.) We recognize there was indeed ACA–related volatility when DHCS made its initial decision to halt monthly reporting, due to the first open enrollment and the ensuing backlog of Medi–Cal applications. However, with much of the backlog now resolved, the Legislature continues to operate in a five–month information vacuum with respect to caseload. We recommend the Legislature require DHCS to report at budget hearings on options for releasing statewide monthly enrollment data, aggregated at the level of families and children, SPDs, and childless adults.

Ask Administration About Future Treatment of Mandatory Expansion. It is clear that the ACA, through enrollment simplification and outreach, has led to greater Medi–Cal uptake among those previously eligible. However, continuing attempts to parse out this segment from the overall caseload estimate seem abstract and potentially misleading, as more data accumulate and any definable distinction between mandatory and nonmandatory caseload fades. The DHCS indicated that the May Revision will likely continue to project the mandatory expansion as part of its policy change forecast. We recommend that the department report at budget hearings about this forecasting decision and how it interacts with the projection for the underlying trend in families and children caseload.

In Addition to ACA, Begin Refocusing on Underlying Trends. While the ACA has had an important and sudden impact on total Medi–Cal enrollment, in this analysis we have also raised the issue of underlying enrollment trends for the Legislature’s consideration. We recommend the Legislature explore this issue during budget hearings. For example, we suggest the Legislature ask the administration to describe its outlook for the economy’s effect on the families caseload. We agree that budgeting for some downside risk is prudent. Outside of budgeting, however, there are policy reasons to be interested in caseload’s future trajectory, such as access and capacity within the program. Finally, we recommend the Legislature require the department to report on sustained increases in costlier Medi–Cal populations that are not driven by the ACA, such as the underlying trend for seniors.

BHT Services Added as a Medi–Cal Benefit After 2014–15 Budget Act Enacted. Chapter 40, Statutes of 2014 (SB 870, Committee on Budget and Fiscal Review), the health trailer legislation for the 2014–15 Budget Act, requires DHCS to add BHT services, such as Applied Behavioral Analysis (ABA), as a covered Medi–Cal benefit to the extent required by federal law. Subsequent to the enactment of the 2014–15 Budget Act, the federal government issued guidance indicating that BHT should be a covered Medicaid benefit for eligible children and adolescents with ASD. In response to the guidance, DHCS is in the process of obtaining federal approval for the provision of BHT services to Medi–Cal beneficiaries under age 21 with ASD. In the interim, as of September 15, 2014, Medi–Cal managed care plans are required to provide medically necessary ABA services for eligible children and adolescents with ASD.

Budget Includes Preliminary Cost Estimates for BHT. The Governor’s budget includes $89 million General Fund in 2014–15 that was not included in the 2014–15 Budget Act and $151 million General Fund in 2015–16 for the provision of BHT services to eligible children with ASD. The DHCS is still in the process of reviewing data on cost and utilization of BHT services; therefore, the estimated costs of BHT services included in the Governor’s budget are preliminary. The DHCS expects to provide updated estimates for the cost of BHT services at the time of the May Revision.

Some Medi–Cal Enrollees Currently Receive BHT Services Through Department of Developmental Services (DDS). There are about 7,500 children and adolescents enrolled in Medi–Cal who receive BHT services through DDS. With the addition of BHT services as a Medi–Cal benefit, as new children enroll in Medi–Cal and existing enrollees are provided BHT services, they will receive them through Medi–Cal and not through DDS. This is consistent with the policy that DDS is the payer of last resort for services it provides to developmentally disabled individuals. Additionally, DHCS expects those children and adolescents currently receiving BHT services through DDS to transition to receiving BHT services through Medi–Cal managed care during 2015–16. The current cost associated with providing BHT services through DDS is roughly $70 million General Fund annually and is included in the Governor’s budget for DDS. There is no funding in the Medi–Cal budget to reflect the anticipated transition of costs from DDS to Medi–Cal for BHT as children and adolescents transition to receiving BHT services through Medi–Cal.

Implementation of BHT Benefit in Early Stages. While Medi–Cal–enrolled children and adolescents with ASD have been able to access BHT services since September, DHCS is in the early stages of implementing the BHT benefit. The number of children and adolescents receiving services is slowly ramping up. At the time of this analysis, 420 children and adolescents are receiving BHT services through Medi–Cal managed care plans and an additional 1,200 are in the process of being screened and evaluated for eligibility for BHT services. There are likely several thousand additional children and adolescents who will access BHT services through Medi–Cal. This is in addition to the 7,500 Medi–Cal enrolled children and adolescents receiving BHT services through DDS.

LAO Assessment. Based on the rate of the ongoing phase–in of BHT services and our review of the preliminary data used to estimate the cost of BHT services in the Governor’s budget, we expect that the estimated costs to provide BHT services (excluding costs in the DDS budget) in 2014–15 and 2015–16 are likely to be lower at the time of the May Revision than the current estimate of $89 million General Fund in 2014–15 and $151 million General Fund in 2015–16. We will review the administration’s updated estimates in May and provide the Legislature with our recommendations if we find adjustments to the Governor’s estimates are warranted.

The MCO tax is an important source of funding for the state’s Medi–Cal costs. The administration estimates that revenues from this tax will offset General Fund spending for Medi–Cal local assistance by $800 million in 2014–15 and $1.1 billion in 2015–16. Under existing law, the tax expires on July 1, 2016. In July 2014, CMS issued a letter to states indicating that taxes structured like California’s MCO tax are inconsistent with federal Medicaid law and regulations. The CMS’s letter advises California to bring its MCO tax structure into compliance by no later than August 30, 2016. If the state were to extend the tax beyond this deadline without addressing CMS’s concerns, it could risk losing over $1 billion in federal Medicaid funds annually.

The MCO tax is an important part of the Governor’s budget plan because (1) it provides significant General Fund relief for the Medi–Cal budget and (2) the Governor proposes to use some of the funding for additional purposes in the In–Home Supportive Services (IHSS) Program. In this analysis, we provide a framework for the Legislature to understand the potential effects of the Governor’s proposal and recommend how the Legislature should respond to it.

Health Care–Related Taxes Are Defined in Federal Law. Federal Medicaid law defines a health care–related tax as a licensing fee, assessment, or other mandatory payment that is related to the provision of or payment for health care services or items. In many cases, states collect these payments from health care providers to help finance the nonfederal share of their Medicaid expenditures.

Federal Requirements for Health–Care Related Taxes. Health care–related taxes must meet three major requirements to be deemed permissible under federal Medicaid law. Figure 8 outlines these requirements. Federal law also defines 19 classes of health care providers for the purposes of applying the broad–based requirement. These classes include hospitals, SNFs, and MCOs. Therefore, to satisfy the broad–based requirement, a state that levies a health care–related tax on some MCOs must levy the same tax on all MCOs under its jurisdiction—unless the state obtains a federal waiver, which we describe shortly.

Figure 8

Three Requirements for Health Care–Related Taxes

|

Broad–Based. The tax is broad–based if it is imposed on all providers within a specified class of providers.

|

|

Uniform. The tax is uniform if it is applied at the same rate for all payers of the tax.

|

|

No Hold Harmless. The state may not provide a direct or indirect guarantee that providers receive their tax payment back (or be “held harmless” from the tax).

|

States Can Receive Waivers of Broad–Based and Uniform Requirements. Federal Medicaid rules permit some health care–related taxes that do not meet the strict definitions of “broad–based” and “uniform.” (Federal law does not allow for any waivers of the no–hold–harmless requirement.) Thus, some permissible taxes may exempt certain providers and/or vary the tax rate across providers. To ensure such a tax is treated as permissible, a state must formally request CMS to waive the broad–based and uniform requirements. Within this waiver request, the state must demonstrate that its tax structure is generally redistributive. In practice, this means the state has to provide certain calculations to show that the tax—like a strictly broad–based and uniform tax—would tend to transfer revenue from non–Medicaid to Medicaid providers. Therefore, if the state attempted to exempt all non–Medicaid providers from the tax, the tax would likely fail to be generally redistributive and be denied a waiver from CMS.

A waiver of broad–based and uniform requirements for health care–related taxes—if approved—is effective the first day of the quarter the waiver is received from CMS. (For example, a waiver received at the end of September would be retroactively effective to the beginning of July.) California has secured waivers for two of its largest permissible health–care related taxes: the hospital quality assurance fee and the SNF quality assurance fee. Both fees exempt certain facilities and vary their rates based on the size or type of facilities.

Requirements Can Create “Losers” Among Taxed Providers. Because health care–related taxes must be broad–based or generally redistributive, they must include providers that do not participate much (or at all) in Medicaid. These providers are unlikely to receive sufficient Medicaid payments to fully offset the amount of tax they owe.

Impermissible Taxes Result in Loss of Federal Medicaid Reimbursement. States must report their quarterly Medicaid expenditures to CMS to document the amounts that qualify for federal reimbursement. If CMS finds that a state has received revenues from impermissible health care–related taxes, then CMS will deduct these revenues from the state’s allowable Medicaid expenditures. In effect, this reduces the amount of FFP that the state would otherwise be entitled to receive.

California’s Current MCO Tax. Chapter 33, Statutes of 2013 (SB 78, Committee on Budget and Fiscal Review), imposes a sales tax on the “sellers” of Medi–Cal managed care plans—for the privilege of selling Medi–Cal health care services at retail—until July 1, 2016. (The terms “managed care plan” and “MCO” are often used interchangeably. In our view, this usage conflates the basis for the tax with the actual entity that pays the tax. For purposes of this analysis, we define managed care plan as a particular health coverage product, and MCO as the licensed carrier offering this product. For more information on how we classify MCOs and managed care plans throughout this analysis, see the nearby box.)

Chapter 33 establishes the MCO tax as 3.9 percent—equal to the sales and use tax rate—of the total operating revenue an MCO receives through its Medi–Cal managed care plan. The state Board of Equalization (BOE) collects the tax from MCOs in quarterly installments and deposits the proceeds into a special fund. At a high level, the tax can be thought of as drawing down enough FFP to hold MCOs harmless and offset other General Fund costs. The actual process, however, works somewhat in the opposite direction. Below, we provide more information about the process.

Throughout this analysis, we use the term “MCO” to refer to a health coverage carrier whose licensure and activities are governed under the Knox–Keene Health Care Service Plan Act of 1975. These carriers contract to provide or arrange for all medically necessary covered services for their enrollees, in return for fixed monthly prepayments. (This approach is sometimes referred to as the “promise to provide care.”) With the exception of Gold Coast Health Plan in Ventura County, all MCOs are licensed and regulated by the Department of Managed Health Care (DMHC) for at least some of their products. The MCOs are commonly known for operating health maintenance organizations (HMOs), although some also operate preferred provider organizations (PPOs) that are regulated by DMHC. In contrast, other PPOs and indemnity health insurance companies contract to cover a specific dollar loss or percentage of loss related to their policyholders’ medical expenditures. (This approach is sometimes referred to the “promise to pay.”) This type of health insurance is regulated by the California Department of Insurance (CDI). Over 21 million Californians, or more than half of the state’s population, are enrolled in DMHC–regulated MCO products. By comparison, around 2 million Californians have health insurance regulated by CDI.

A single MCO may contract with a variety of payers to provide health coverage. These may include (1) individuals who purchase coverage for themselves or their families, (2) businesses and public agencies that purchase coverage for their employees, and (3) government programs like Medi–Cal and Medicare that outsource care delivery for their beneficiaries. By “managed care plan,” we mean an MCO’s contract to provide services to a particular payer within a particular health coverage product. For example, in our nomenclature, Anthem Blue Cross is an MCO, while Anthem’s HMO contract with the Department of Health Care Services to enroll and provide care for Medi–Cal beneficiaries is the MCO’s “Medi–Cal managed care plan.”

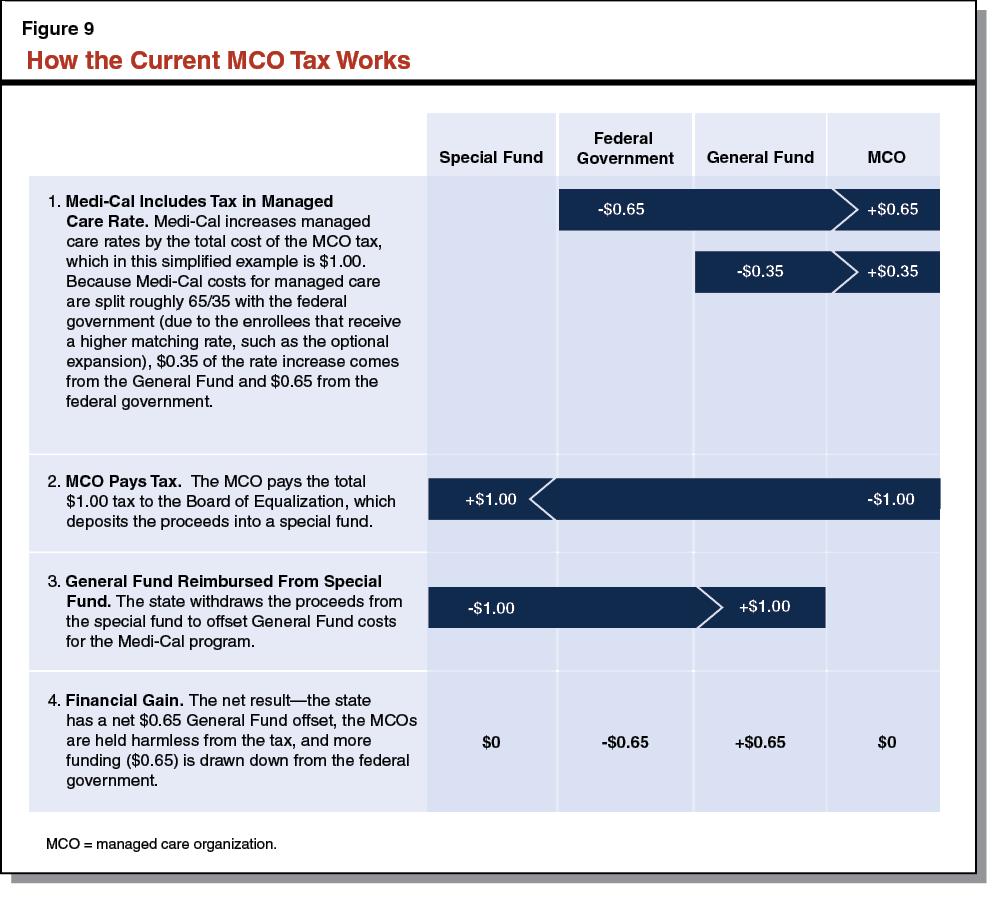

As shown in Figure 9, the state initially pays its share of Medi–Cal capitation rates—which include the built–in cost of the MCO tax—from the General Fund. These payments draw down federal funds at the relevant matching rate. Meanwhile, BOE collects the tax based on MCOs’ projected Medi–Cal revenues, which include the federal and state shares. (The BOE reconciles these collections with MCOs’ actual Medi–Cal revenues in the following tax year.) Thus, as MCOs make tax payments to BOE, they are simultaneously made whole through higher Medi–Cal payments that incorporate the cost of the tax. Finally, DHCS withdraws most of the tax proceeds from the special fund as quarterly reimbursement for (1) the state’s share of capitation increases for the cost of the tax, and (2) other General Fund costs in the Medi–Cal program.

Figure 10 shows the administration’s revised estimates for the flow of funds in 2014–15. The combined amount of General Fund and federal funds for capitation increases—$1.4 billion—is equal to the amount of MCO tax revenue collected. (The federal funds amount is higher than the General Fund amount due to the enhanced matching rate for certain populations and services, such as the optional expansion.) The difference between the General Fund’s contribution to and reimbursement for capitation increases is due to the timing lag between BOE’s collection of the tax and DHCS’s request for funding adjustments.

Figure 10

Funding Flow of Current MCO Tax in 2014–15

|

Inflows/(Outflows), (In Millions)

|

Special Fund

|

General Fund

|

Federal Funds

|

|

Capitation increases for Medi–Cal managed care

|

—

|

($510.8)

|

($922.0)

|

|

MCO tax revenue collection

|

$1,433.3

|

—

|

—

|

|

Reimbursement of General Fund for capitation increasesa

|

(466.0)

|

466.0

|

—

|

|

Reimbursement of General Fund for other Medi–Cal costsa

|

(802.8)

|

802.8

|

—

|

Current MCO Tax Likely Impermissible. In its July 2014 letter, CMS clarified its interpretation of federal requirements governing health care–related taxes. Specifically, CMS indicated that taxes structured like California’s current MCO tax will likely be considered health care–related taxes from the federal perspective, meaning that California’s tax would need to meet the various Medicaid requirements for health care–related taxes (unless an available waiver is obtained). Of the state’s nearly 70 full–service MCOs, over half do not contract with DHCS to provide Medi–Cal managed care plans and therefore do not pay any MCO tax. Clearly, within the provider class of MCOs, the tax is neither broad–based (a fundamental requirement for health care–related taxes) nor generally redistributive (a condition to obtain a waiver from this requirement). Therefore, it is likely impermissible under federal Medicaid rules.

If the tax is extended in its current form past CMS’s deadline for states to reform their tax structures, California would risk the entire amount of FFP attached to the tax. However, because (1) CMS’s deadline is the end of states’ legislative sessions—August 31, 2016 for California—and (2) the current MCO tax sunsets on July 1, 2016, we believe the FFP amounts generated by the tax in 2014–15 and 2015–16 are not at risk, even if the state took no further action to extend or modify the tax. The administration estimates this FFP to be $922 million in 2014–15 and $1.2 billion in 2015–16.

IHSS Legal Settlement Agreement. In 2013, the administration agreed to a settlement with plaintiffs who had brought two class–action lawsuits against the state related to previously enacted IHSS budget reductions. The terms of the IHSS settlement agreement led to the implementation of the 7 percent reduction in IHSS hours in 2014–15. The settlement agreement’s terms also require the administration to pursue CMS approval for an “assessment”—with the resulting revenue used to provide the nonfederal share of funding needed to restore service hours from the current 7 percent reduction. The terms of the IHSS settlement agreement—recently amended by both parties—further specify that the administration must submit the assessment (if approved by the Legislature) for CMS approval no later than April 1, 2015. If this deadline is missed, the parties to the settlement agreement will discuss next steps, which ultimately could result in going back to the court for a resolution and court–ordered remedies.

The Governor proposes to restructure the MCO tax to conform to federal Medicaid requirements as clarified by the recent CMS guidance. The administration will pursue a tax structure that meets the criteria for a broad–based and uniform waiver—including a generally redistributive structure—as well as the no–hold–harmless requirement. The Governor proposes that the new structure, in addition to being federally permissible, be designed to raise enough revenue to fund two objectives. Below, we list these objectives in descending order of funding priority, as specified in the administration’s draft language.

- Fund 7 Percent Restoration in IHSS. The first objective is to fund the nonfederal share of payments needed to restore IHSS hours that were eliminated as a result of the current 7 percent reduction. The nonfederal cost for restoring the hours is estimated to be $216 million in 2015–16.

- Maintain Current General Fund Offset in Medi–Cal. The second objective is to maintain the General Fund offset from the current tax. This offset is estimated to be $1.1 billion in 2015–16.

Next, we discuss key features of the Governor’s proposed MCO tax structure.

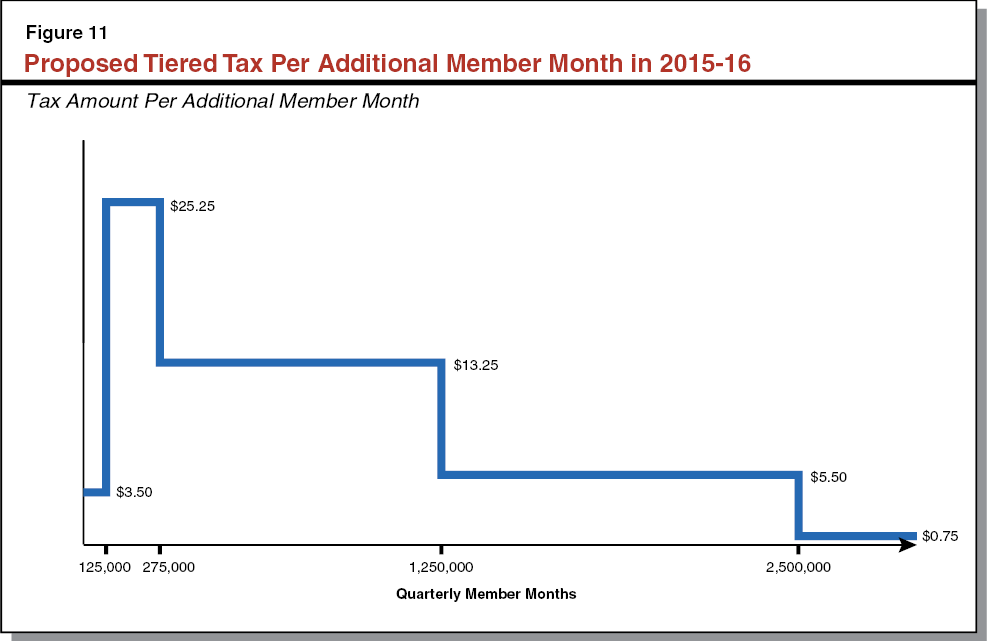

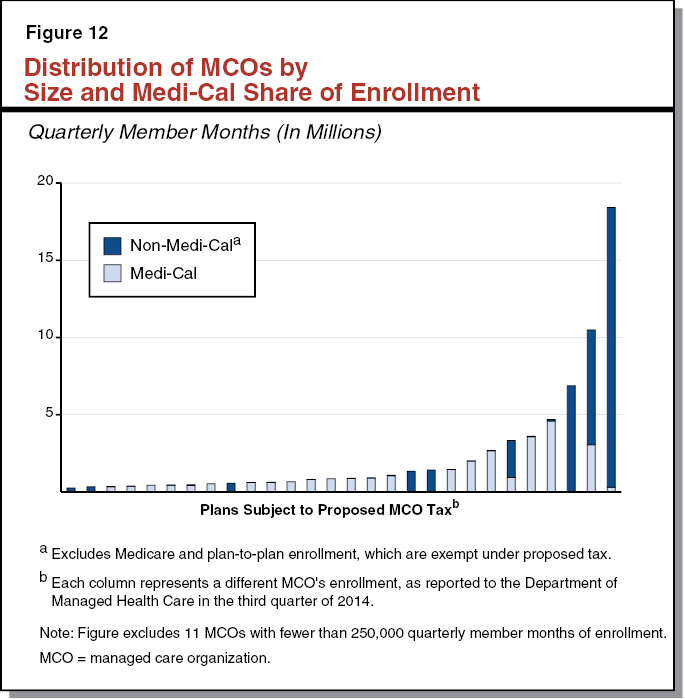

Impose Tax on Most MCOs. To establish a generally redistributive structure, the Governor proposes to impose the new tax on most MCOs, defined as full–service health plans regulated by the Department of Managed Health Care (DMHC) or DHCS. (For a more detailed description of the types of entities covered by the proposed tax, see the box on page 25.) As described below, the Governor proposes to exclude Medicare managed care plans from the restructured tax base (as allowed under federal rules), which effectively exempts MCOs that only offer these types of products. The proposal would also exempt specialized MCOs that offer only limited services such as vision and dental coverage, and health insurance products regulated by the California Department of Insurance. Finally, the proposal would exempt several full–service MCOs that provide cross–border coverage to enrollees in Mexico. This last exemption requires a CMS–approved waiver of the broad–based requirement. After accounting for these specific and effective exemptions, 39 MCOs would be subject to the restructured tax, compared to 27 that are subject to the current tax.