The Governor’s Budget Proposal

On January 9, 2014, the Governor presented his 2014–15 budget proposal to the Legislature. As displayed in Figure 1, the Governor’s spending plan includes $151 billion in spending from the General Fund and special funds combined. This reflects an $11 billion—or 8 percent—increase over 2013–14 revised levels. Recent, sharp increases in personal income tax collections—driven largely by soaring stock prices in 2013—have improved the state’s budget condition significantly.

Figure 1

Governor’s Budget Expenditures

(Dollars in Millions)

|

Fund Type

|

2012–13 Revised

|

2013–14 Revised

|

2014–15 Proposed

|

|

Change From 2013–14

|

|

Amount

|

Percent

|

|

General Funda

|

$96,562

|

$98,463

|

$106,793

|

|

$8,331

|

8.5%

|

|

Special funds

|

37,724

|

41,153

|

43,979

|

|

2,826

|

6.9

|

|

Budget Totals

|

$134,286

|

$139,616

|

$150,772

|

$11,156

|

8.0%

|

|

Selected bond funds

|

$6,715

|

$8,181

|

$4,166

|

–$4,015

|

–49.1%

|

|

Federal funds

|

70,431

|

85,803

|

84,562

|

|

–1,241

|

–1.4

|

Administration’s Budget Forecast

Improved General Fund Condition. Figure 2 displays the administration’s projection of the General Fund condition. The June 2013 spending plan assumed that 2013–14 would end with a $1.1 billion reserve. The Governor’s budget now estimates a $3 billion reserve for the state at the end of 2013–14. The $1.9 billion increase in the 2013–14 reserve is largely explained by:

- Higher 2011–12, 2012–13, and 2013–14 Revenues. Over 2012–13 and 2013–14 combined, the administration now estimates General Fund revenues and net transfers to be $4.8 billion higher than budget act estimates. In addition, there is a $558 million upward fund balance adjustment for 2011–12 and prior years mainly related to revenue accruals.

- Higher General Fund Proposition 98 Spending. The administration’s estimated revenue gains are in large part offset by $3.6 billion in increased General Fund spending on schools and community colleges in 2012–13 and 2013–14. In addition, the administration has revised its non–Proposition 98 spending estimates for 2012–13 and 2013–14—changes that, on net, improve the budget condition by a small amount.

Governor Proposes $2.3 Billion Reserve at End of 2014–15. The Governor’s budget plan includes General Fund spending in 2014–15 that exceeds revenues by about $700 million. The budget, however, includes several one–time spending items, including a $1.6 billion one–time supplemental payment to retire the state’s outstanding economic recovery bonds (ERBs). The Governor can trigger this supplemental payment under Proposition 58 (2004), the state’s existing rainy–day fund requirement. (The supplemental payment will result in an early retirement of the ERBs, generating General Fund savings from expiration of the so–called “triple flip” in 2015–16—about one year earlier than otherwise would be the case.) The Governor proposes the state end 2014–15 with a total General Fund reserve of $2.3 billion—$700 million below the revised reserve level at the end of 2013–14. The 2014–15 reserve is a combination of $1.6 billion in the Proposition 58 rainy–day fund (known as the Budget Stabilization Account [BSA]) and $693 million in the General Fund’s traditional reserve, the Special Fund for Economic Uncertainties (SFEU).

Figure 2

Governor’s Budget General Fund Condition

Includes Education Protection Account (In Millions)

|

|

2012–13

|

2013–14

|

2014–15

|

|

Prior–year fund balancea

|

–$1,100

|

$2,254

|

$3,938

|

|

Revenues and transfers

|

99,915

|

100,147

|

106,094b

|

|

Total resources available

|

$98,816

|

$102,401

|

$110,032

|

|

Expenditures

|

$96,562

|

$98,463

|

$106,793c

|

|

Ending fund balance

|

$2,254

|

$3,938

|

$3,239

|

|

Encumbrances

|

$955

|

$955

|

$955

|

|

Reserved

|

$1,299

|

$2,983

|

$2,284

|

|

Budget Stabilization Account

|

—

|

—

|

$1,591

|

|

Special Fund for Economic Uncertaintiesd

|

$1,299

|

$2,983

|

693

|

Major Features of the Governor’s Budget

Figure 3 displays the major features of the Governor’s budget proposal. In recent years, the primary focus of the budget process has been on the General Fund. Until the 2013–14 budget deliberations, the state had faced a multibillion dollar General Fund shortfall in nearly every year over the preceding decade. Recently, however, the need for these actions has diminished, and this year the state is faced with choices on how to allocate several billion dollars of surplus General Fund resources. The Governor’s budget reflects this shift in focus away from the General Fund, as many of his major proposals are for special fund programs. Below, we describe the major proposals in the Governor’s budget plan.

Figure 3

Major Features of the Governor’s Budget

|

Reserve/Rainy–Day Fund

|

- End 2014–15 with $2.3 billion reserve (including $1.6 billion in Proposition 58 reserve).

- Create new rainy–day fund mechanism to replace existing Proposition 58 reserve with new Proposition 98 reserve.

|

|

Paying Down State Debts (One–Time Costs)

|

- Accelerate pay down of economic recovery bonds by about one year ($1.6 billion General Fund).

- Pay off remaining school and community college deferrals ($6.2 billion Proposition 98 funds).

- Repay $1.6 billion in special fund loans in 2013–14 and 2014–15 combined.

- Provide $188 million for school repairs.

|

|

Education

|

- Provide additional $4.5 billion for K–12 Local Control Funding Formula.

- Increase funding for community college student support ($200 million).

- Provide 3 percent increase for community college enrollment growth ($155 million).

- Provide unallocated base augmentations to UC and CSU ($142 million each).

- Create $50 million grant program for universities and community colleges to change service delivery.

- Shift debt–service payments into CSU’s budget.

|

|

Health and Human Services

|

- Exempt certain Medi–Cal providers from recoupment of prior–year payment reductions previously enjoined.

- Restrict overtime for IHSS workers in response to new federal regulations.

|

|

Infrastructure

|

- Deliver to Legislature first five–year infrastructure plan since January 2008.

- Provide $815 million in one–time funds (from General Fund and other funds) for deferred maintenance projects.

- Authorize $500 million in lease–revenue bond authority for jail construction.

|

|

Cap–and–Trade

|

- Allocate $850 million in cap–and–trade auction revenues to various programs, including: $250 million for construction of the high–speed rail system and $200 million for low–emission vehicle program.

|

|

Water

|

- Propose $618 million plan (almost all from special funds) for various water–related programs, including protecting groundwater basins, augmenting local water supplies, and improving flood protection.

- Transfer safe drinking water program from Department of Public Health to State Water Resources Control Board.

|

|

Judiciary and Criminal Justice

|

- Provide $105 million ongoing increase to judicial branch.

- Assume two–year extension of court–ordered population cap.

|

|

Other Programs

|

- Assume that most state employees receive at least 2 percent pay increase in 2014–15 ($173 million all funds).

|

Proposes $2.3 Billion Reserve. For the first time since 2007–08, the Governor’s budget reflects his intent to transfer funds to the BSA. (Under Proposition 58, the Governor determines whether the scheduled BSA transfer occurs annually.) Specifically, the budget plan shifts 3 percent ($3.2 billion) of General Fund revenues to this rainy–day fund. Half of these funds must go to accelerate repayment of the ERBs, which were used to finance state budget deficits of the early 2000s.

Includes New Rainy–Day Fund Constitutional Proposal. The Governor’s budget package proposes to replace ACA 4—the rainy–day fund measure currently scheduled for the November 2014 ballot—with an alternative measure. Specifically, the measure would base the required deposits into the rainy–day fund on projections of capital gains–related PIT—the state’s principal source of revenue volatility. In addition, the proposal would create a Proposition 98 reserve to attempt to reduce volatility within the Proposition 98 budget.

Pays Down State Debts. The Governor’s proposal reflects his continued focus on repaying items on the wall of debt. As discussed above, half of the transfer to the BSA will be used to accelerate the pay down of the ERBs. The Governor plans to use much of the large growth in Proposition 98 funding to pay off the remaining school and community college deferrals ($6.2 billion). The Proposition 98 package also includes $188 million for the Emergency Repair Program (ERP). Additionally, the plan provides funds to pay off $1.6 billion in special fund loans in 2013–14 and 2014–15 combined, including a $328 million Highway Users Tax Account loan and $100 million of the loan from the Greenhouse Gas (GHG) Reduction Fund. (As described later, the latter two repayments are related to the Governor’s infrastructure and cap–and–trade proposals.)

Includes $11.8 Billion for Proposition 98 Above 2013–14 Budget Act Levels. The Governor’s budget includes $11.8 billion in Proposition 98 spending increases—$7.6 billion attributable to 2014–15, $3.7 billion attributable to 2012–13 and 2013–14, and $503 million for earlier years. Of the $11.8 billion, $6.8 billion is designated for one–time purposes and $5 billion for ongoing purposes. Most of the one–time funding is allocated for paying off the school and community college deferrals ($6.2 billion). Of the ongoing funding, $4.5 billion is for the school district Local Control Funding Formula (LCFF).

Proposes Increased General Purpose Funding for Universities. The Governor proposes unallocated base budget increases of $142 million each for University of California (UC) and California State University (CSU) in 2014–15. These increases represent the second annual installment in a four–year funding plan proposed by the Governor last year. The Governor conditions his proposed annual funding increases for the universities on their maintaining tuition at current levels. Similar to last year, the Governor does not propose enrollment targets or enrollment growth funding for the universities.

Infrastructure Proposals Include $815 Million for Deferred Maintenance. According to the Governor’s Budget Summary, the administration intends to deliver to the Legislature the first five–year infrastructure plan since 2008. The budget plan includes major proposals related to infrastructure, including $815 million (mostly from special funds) for deferred maintenance projects. In addition, the budget proposes to shift $211 million in remaining bond authority from various school facility programs, such as seismic mitigation, to new school construction and school modernization. Similar to last year, the Governor proposes to shift debt–service payments into CSU’s main appropriation. The Governor’s budget plan also proposes $500 million in lease–revenue bond authority to help counties construct and modify jail facilities.

Proposes $850 Million Cap–and–Trade Spending Plan. In 2006, legislation was enacted to reduce GHG emissions statewide to 1990 levels by 2020. Among these efforts, the state’s cap–and–trade program places a “cap” on aggregate GHG emissions from entities responsible for roughly 85 percent of the state’s GHG emissions. The Governor’s budget includes a plan for allocating $850 million in cap–and–trade auction revenues, including $250 million for the state’s high–speed rail project.

Includes $618 Million Plan for Water Projects. In October 2013, the administration released a draft plan to address water challenges facing the state. These challenges include limited and uncertain water supplies, poor quality of surface water and groundwater, impaired ecosystems, and high flood risk. The Governor’s budget package includes $618 million to implement some aspects of the plan.

The Administration’s Multiyear Forecast

Forecasts Balanced Budgets Through 2017–18. The administration’s multiyear budget projection reflects both its updated revenue and expenditure projections, as well as projections of various proposals made by the Governor in his 2014–15 budget plan. It projects that General Fund revenues will annually exceed expenditures after 2014–15, resulting in an operating surplus of $1.7 billion in 2015–16, growing to $2.3 billion in 2017–18. Compared to our November forecast , these operating surpluses are much lower. This disparity results in large part from a few billion dollars in each year for wall of debt payments that are not included in our forecast. Even with these payments, the administration forecasts that 2017–18 would end with an $8.3 billion reserve—$4.6 billion in the BSA and $3.7 billion in the SFEU. Consistent with standard forecasting conventions—including our office’s—the administration’s multiyear forecast implicitly assumes continuation of the current economic expansion for several years.

LAO Comments

Governor’s Budget Would Continue California’s Fiscal Progress. California has made substantial progress in recent years in addressing its prior, persistent state budgetary problems. This progress has been facilitated by a recovering economy, a stock market that has been soaring recently, increased revenues from the temporary taxes of Proposition 30, and the state’s recent decisions to make relatively few new non–Proposition 98 spending commitments. Overall, the Governor’s proposal would place California on an even stronger fiscal footing and continue California’s fiscal progress. By allowing deposits to the state’s existing Proposition 58 rainy–day fund to resume, the state can begin to build a strong precedent for accumulating reserves during good revenue times. The Governor’s planned early repayment of the state’s deficit bonds would free up sales tax resources now dedicated to bond repayment to support the General Fund beginning in 2015–16 or so. The Governor also prudently proposes to continue paying down special fund loans and other wall of debt items, including his plan to pay off all school payment deferrals from Proposition 98 funds. Finally, the Governor proposes limited new spending outside of Proposition 98, some of which is one–time spending commitments such as his deferred maintenance proposal.

Governor Prudently Prioritizes Debt Repayments. In crafting his 2014–15 budget proposal, the Governor started with a possible surplus comparable in size to the one we estimated in our November 2013 Fiscal Forecast. (While the administration’s revenue estimates are somewhat lower, so are its Proposition 98 and some other spending estimates.) The Governor prioritized making wall of debt repayments in his proposal. In the budget summary, the administration estimates that the Governor’s plan would reduce the wall of debt by $11.8 billion in 2014–15. These reductions can be broken into three categories: (1) ERB wall of debt costs that are mandatory, which are about $2 billion in 2014–15; (2) Proposition 98 wall of debt reductions of about $6.7 billion—principally the Governor’s choice to propose pay downs of school payment deferrals (to be paid from the overall pot of state funds required to be provided to schools); and (3) the remaining $3 billion or so of wall of debt repayments in the Governor’s plan. This $3 billion consists mainly of the Governor’s planned $1.6 billion payment to retire the remaining ERBs one year early and his proposed $1 billion of payments to pay off past loans from the state’s special funds. While the Governor has the authority under Proposition 58 to trigger the accelerated ERB repayment, this decision and at least some of his proposed special fund loan repayments represent choices that he made in designing his budget proposal. In general, we think the Governor’s focus on debt repayments is a prudent one. The Legislature, however, has the ability to amend the Governor’s special fund loan repayment plan by adding different special fund loan repayments, deleting others, changing proposed repayment amounts, or adopting broader changes to fees and expenditures of the special funds involved.

Goals of Governor’s Rainy–Day Proposal Are the Right Ones. As described in the “Rainy–Day Fund” section of this report, regularly contributing to a larger rainy–day fund is exactly the direction the state should be taking at a time when revenues are soaring. The Governor’s proposal would base deposits into the rainy–day fund on capital gains related revenues—the principal source of state revenue volatility. The state’s experience with constitutional formulas, however, suggests that any formula–based proposal merits careful legislative consideration. In the “Rainy–Day Fund” section of this report, we discuss some of the factors the Legislature may wish to consider in weighing a constitutional rainy–day fund requirement.

Governor’s Overall Proposition 98 Plan Reasonable. We believe the Governor’s Proposition 98 plan provides a reasonable mix of one–time and ongoing spending. By retiring the $6.2 billion in outstanding K–14 deferrals, the Governor’s plan would eliminate the largest component of the school and community college wall of debt by the end of 2014–15. In addition to reducing outstanding one–time Proposition 98 obligations significantly, the Governor’s plan also would increase ongoing programmatic spending significantly by augmenting both the LCFF and community college programs. The mix of one–time and ongoing spending is particularly important in 2014–15 given the minimum guarantee likely will be very sensitive to volatility in General Fund revenues, with estimates of the guarantee potentially swinging widely over the coming months.

Governor’s Higher Education Proposals—Similar Concerns as Last Year. The Governor’s higher education budget plan is very similar to last year, with the continuation of most of his proposals relating to unallocated base budget increases; no specified expectations with regards to operations, facilities, or performance; and no enrollment expectations. As with last year, we remain concerned that his plan would lead to less responsiveness from the segments in meeting state priorities as well as diminished state guidance and oversight.

Focus on Deferred Maintenance Positive. As described earlier, the Governor’s budget proposes $815 million for deferred maintenance projects. We believe that it is important for the state to begin to address its accumulated deferred maintenance needs. While deferring annual maintenance lowers costs in the short run, it often results in substantial costs over the long run. The Governor’s plan is a positive first step towards dealing with an important and often ignored program.

Issues With Other Infrastructure Proposals. The Governor’s budget contains several infrastructure ideas and proposals, including ones relating to school facility funding, CSU debt service, and county jail construction. With regards to rethinking the financing of school facilities, the Legislature would have many issues to consider—from differences in local revenue–raising ability among districts to the distribution of any state funds among districts, the stability of that funding, and the incentives provided for districts to build and maintain facilities cost–effectively. Regarding the Governor’s CSU debt–service proposal, we are concerned that the approach diminishes the Legislature’s oversight over the university’s use of state funds. And with respect to the Governor’s proposal for $500 million in bond authority for county jail construction, we suggest that the Legislature seek from the administration additional information on county jail needs and other issues in considering the proposal.

Cap–and–Trade Proposal Unlikely to Maximize Emission Reductions. The Governor’s budget proposes a plan for using $850 million in auction revenues generated from the cap–and–trade program for various projects to GHG emissions. Most notably, the plan includes $250 million for the state’s high–speed rail project. As discussed later in this report, we are concerned that the Governor’s proposal likely would not maximize the reduction of GHG emissions.

Governor’s Integrated Approach for Water Has Merit. The Governor’s budget proposes $618 million to begin implementing a plan to address water challenges facing the state. We find that the Governor’s integrated approach has merit, though we lay out some policy considerations and funding issues that the Legislature may want to consider in weighing the Governor’s proposal.

Setting Aside Some Money for CalSTRS Now Would Be Smart. The Governor’s Budget Summary expressed an interest in working with school districts and teachers over the coming year to reach agreement on a long–term California State Teachers’ Retirement System (CalSTRS) funding plan that would fully fund the system over a 30–year period. We agree with the Governor regarding the key goal of a shared responsibility to achieve a fully–funded, sustainable teachers’ pension system within about 30 years. In the meantime, however, we suggest that the state set aside some money during the 2014–15 budget process—when the state is experiencing a significant influx of revenues—in anticipation of the state’s adoption of a long–term CalSTRS funding plan.

Planning for Possibility of Even Higher Revenue Estimates in May. In May, when the Governor presents his revised budget plan to the Legislature, both the administration and our office will release new economic and revenue estimates. Given recent economic and tax collection data, however, there is a significant possibility that 2013–14 and perhaps 2014–15 revenue estimates will rise by a few billion dollars. The state’s recent revenue gains are good news for state finances. These gains reflect the state’s continuing economic recovery, which seems to be accelerating somewhat. Nevertheless, a significant portion of the recent revenue surge probably results from capital gains–related PIT caused by large increases in stock prices throughout 2013. The Governor is prudent to warn Californians that this revenue surge may prove short–lived.

When a similar revenue surge materialized in the late 1990s, we now know that state leaders made spending and revenue commitments that contributed to the state’s financial problems throughout the last decade. We advise the Legislature to avoid making similar mistakes this year. The Governor’s plan contains a number of features that would help improve the state’s fiscal footing, including an emphasis on debt repayments and an effort to improve the state’s rainy–day fund requirements. By making relatively few ongoing new non–Proposition 98 spending commitments, the Governor is attempting to minimize, as much as possible, future budget pressures that could result from making such new commitments today.

In the event that revenue projections increase between now and May, the Legislature would face important decisions regarding how to allocate additional revenues. Much of any such revenue increases could be required to be spent on schools and community colleges under Proposition 98. After addressing these requirements, we believe the Legislature should give highest priority to increasing the size of the Governor’s proposed reserves and setting aside additional funds in anticipation of making bigger payments on the state’s key retirement liabilities (including payments to address CalSTRS’ unfunded obligations). In order to keep the state on a sound fiscal footing, we advise the Legislature to make only limited and targeted ongoing program commitments from additional revenues that may be identified this spring.

Administration’s Economic Forecast

Recovery Expected to Accelerate Somewhat. The administration’s 2014–15 Governor’s Budget economic forecast assumes that the current moderate economic recovery will accelerate in 2014, leading to broad–based improvements in both the U.S. and California economies over the next two years. This forecast incorporates the negative impact of the recent federal government shutdown—which caused most economists to lower expectations for 2013 economic growth—but assumes these effects were short–lived and therefore will not linger into 2014. The administration expects the U.S. economy (as expressed by real gross domestic product [GDP]) to expand 2.5 percent in 2014, accelerating to 3.1 percent growth in 2015. These growth rates are on par with rates seen typically during a mature economic expansion, reflecting the consensus outlook that U.S. economic growth is returning to more normal levels. Figure 4 summarizes the administration’s economic forecast for 2013 and 2014 and compares it with other recent estimates, including those from our office.

Figure 4

Comparing Administration’s Economic Forecast With Recent Forecasts

|

|

2013

|

|

2014

|

|

2013–14 Budget Act

|

LAO November 2013

|

DOF January 2014

|

IHS Economics January 2014

|

2013–14 Budget Act

|

LAO November 2013

|

DOF January 2014

|

IHS Economics January 2014

|

|

United States

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Percent change in:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Real gross domestic product

|

2.0%

|

1.5%

|

1.7%

|

1.9%

|

|

2.8%

|

2.5%

|

2.5%

|

2.7%

|

|

Personal Income

|

2.8

|

2.8

|

2.8

|

2.9

|

|

5.1

|

4.7

|

4.6

|

4.6

|

|

Employment

|

1.5

|

1.6

|

1.6

|

1.6

|

|

1.6

|

1.7

|

1.6

|

1.7

|

|

California

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Percent change in:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Personal income

|

2.2%

|

2.1%

|

2.6%

|

NA

|

|

5.7%

|

5.4%

|

4.6%

|

NA

|

|

Employment

|

2.1

|

1.7

|

2.1

|

NA

|

|

2.4

|

2.2

|

2.3

|

NA

|

|

Unemployment rate

|

9.4

|

8.9

|

8.9

|

NA

|

|

8.6

|

7.8

|

7.9

|

NA

|

|

Housing permits (thousands)

|

82

|

88

|

87

|

NA

|

|

121

|

120

|

114

|

NA

|

Recent Economic Improvements. In order to meet the Governor’s January 10 budget deadline, administration officials finalize some of their work on this economic forecast by mid–December. Economic data from December and January, including a strongly positive revision to GDP during the period coinciding with the federal government shutdown, suggest the U.S. economy may be performing somewhat stronger than previously estimated. This strength is reflected in the most recent economic forecast included in Figure 4 from IHS Economics (an economics advisory firm), which indicates the U.S. economy, as measured by real GDP, performed better in 2013 than either our office or the administration estimated when completing our most recent forecasts.

Federal Actions No Longer Seem a Significant Threat to Growth in 2014. The partial shutdown of federal government operations in October 2013 and uncertainty about whether Congress would increase the federal government’s so–called “debt ceiling” likely slowed economic growth somewhat in the final quarter of 2013. These risks—along with the automatic spending cuts known as sequestration and the Federal Reserve’s gradual tightening of monetary policy—constituted a threat to consumer, business, and investor confidence that could have slowed the modest recovery. Fortunately, these risks now appear to be fading for the following reasons: (1) the government shutdown does not seem to have affected economic prospects, (2) the debt ceiling was extended until early 2014, and debate on the issue appears less contentious than it was in 2013, (3) Congress passed a bipartisan budget agreement to soften the sequestration spending cuts, and (4) financial markets have reacted calmly to date upon announcement by the Federal Reserve that it would begin “tapering,” the gradual elimination of its unconventional bond purchase program.

Administration’s Revenue Forecast

As shown in Figure 5, the administration’s new revenue forecast projects the General Fund will book $100.1 billion of revenues and transfers in 2013–14 and $106.1 billion in 2014–15. (Administration summaries show estimated 2014–15 revenues of $104.5 billion. This is reduced by the amount of the Governor’s planned $1.6 billion transfer to the BSA, the state’s existing Proposition 58 rainy–day fund. We display all General Fund revenues in our summaries so that figures are more comparable to those of prior years.) Both Figure 5 and Figure 6 show how several key revenue metrics have been revised above levels in the state’s 2013–14 budget act (passed in June 2013) in both our office’s November 2013 revenue projections and the administration’s revised January 2014 projections.

Figure 5

Comparing Administration’s General Fund Revenue Forecast With Prior Forecastsa

General Fund and Education Protection Account Combined (In Millions)

|

|

2013–14

|

|

2014–15

|

|

2013–14 Budget Act

|

LAO November 2013

|

DOF January 2014

|

2013–14 Budget Act

|

LAO November 2013

|

DOF January 2014

|

|

Personal income tax

|

$60,827

|

$66,002

|

$64,287

|

|

$67,132

|

$71,363

|

$69,764

|

|

Sales and use tax

|

22,983

|

22,809

|

22,920

|

|

24,702

|

23,561

|

24,071

|

|

Corporation tax

|

8,508

|

8,278

|

7,971

|

|

9,095

|

8,851

|

8,682

|

|

Subtotals, “Big Three” Taxes

|

($92,318)

|

($97,089)

|

($95,178)

|

($100,929)

|

($103,775)

|

($102,517)

|

|

Insurance Tax

|

$2,200

|

$2,163

|

$2,143

|

|

$2,265

|

$2,343

|

$2,297

|

|

Other revenue

|

2,249

|

2,254

|

2,480

|

|

1,858

|

1,874

|

2,046

|

|

Transfers and loansb

|

331

|

342

|

346

|

|

–385

|

–375

|

–765

|

|

Total Revenues and Transfers

|

$97,098

|

$101,847

|

$100,147

|

$104,667

|

$107,617

|

$106,094

|

Figure 6

Change From 2013–14 Budget Act Revenue Projections to Those in Recent State Revenue Forecasts

General Fund and Education Protection Account Combined (In Billions)

|

|

2011–12 and Prior Years

|

2012–13

|

2013–14

|

2014–15

|

Change From 2013–14 Budget Act—All Four Years Combined

|

|

Personal Income Tax (PIT)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

LAO November 2013 forecast

|

–$0.5

|

$1.1

|

$5.2

|

$4.2

|

$10.1

|

|

Administration January 2014 forecast

|

0.1

|

1.4

|

3.5

|

2.6

|

7.6

|

|

“Big Three” PIT, Sales, and Corporation Taxes Combined

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

LAO November 2013 forecast

|

—

|

$1.5

|

$4.8

|

$2.8

|

$9.2

|

|

Administration January 2014 forecast

|

$0.5

|

1.6

|

2.9

|

1.6

|

6.6

|

|

Total Revenues and Transfers

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

LAO November 2013 forecast

|

—

|

$1.6

|

$4.7

|

$3.0

|

$9.4

|

|

Administration January 2014 forecasta

|

$0.5

|

1.7

|

3.0

|

1.4

|

6.7

|

Key Points

Revenue Forecast Now Significantly Above Budget Act Projections. As shown in Figure 6, the administration has increased its revenue forecast compared to the forecast used in the state’s 2013–14 budget plan. For the four fiscal years of 2011–12 through 2014–15 combined, the administration’s forecast of total General Fund revenues and transfers is now $6.7 billion higher than last year’s budget act forecast. About one–half of this increase ($3 billion) is the result of the administration’s new higher revenue and transfer estimates for 2013–14. Also included in the $6.7 billion total is $536 million of higher PIT and corporation tax (CT) revenue accruals and adjustments for 2011–12 and prior years, which the administration reports as an increase to the beginning 2012–13 General Fund balance. Compared to the administration’s budget act projections, the new revenue estimates include a net amount of $300 million more of transfers out of the General Fund across the four fiscal years—largely accelerated special fund loan repayments proposed by the Governor in his 2014–15 budget plan.

Higher Estimates Due Largely to Higher PIT Projections. Across the four fiscal years, the Governor’s budget forecast for PIT revenue is $7.6 billion above the 2013–14 Budget Act estimate, as shown in Figure 6. This total consists of higher estimates of $56 million in 2011–12 and prior years, $1.4 billion in 2012–13, $3.5 billion in 2013–14, and $2.6 billion in 2014–15. The improvement in the administration’s PIT revenue estimates is offset somewhat by lower estimates of CT revenue (a combined $517 million across the four fiscal years) and sales and use taxes ($452 million over the period).

Personal Income Tax

PIT Revenue Depends on Volatile Capital Gains. The PIT is the state’s largest revenue source, accounting for two–thirds of General Fund revenue in 2014–15 in the administration’s projections. In addition to traditional sources of income such as hourly wages and salaries, the tax is paid on realized capital gains, principally from the sale of stocks, bonds, and real estate. These types of assets are concentrated among high–income taxpayers in the state’s top marginal income tax brackets. The 1 percent of taxpayers with the most income typically have paid around 40 percent of PIT in recent years (rising to nearly 50 percent on occasion), a large portion of which is in the form of capital gains taxes. In addition to its concentration, capital gains are determined largely by sometimes turbulent and unpredictable stock prices. In the space of five years, for example, tax agency data shows that estimated PIT revenues from realized capital gains peaked at $10.9 billion in 2007, fell to $2.3 billion in 2009, and returned to $4.2 billion in 2011. Actual data on capital gains realizations and taxes lags by around a year and a half, meaning that 2012 data will become available this year.

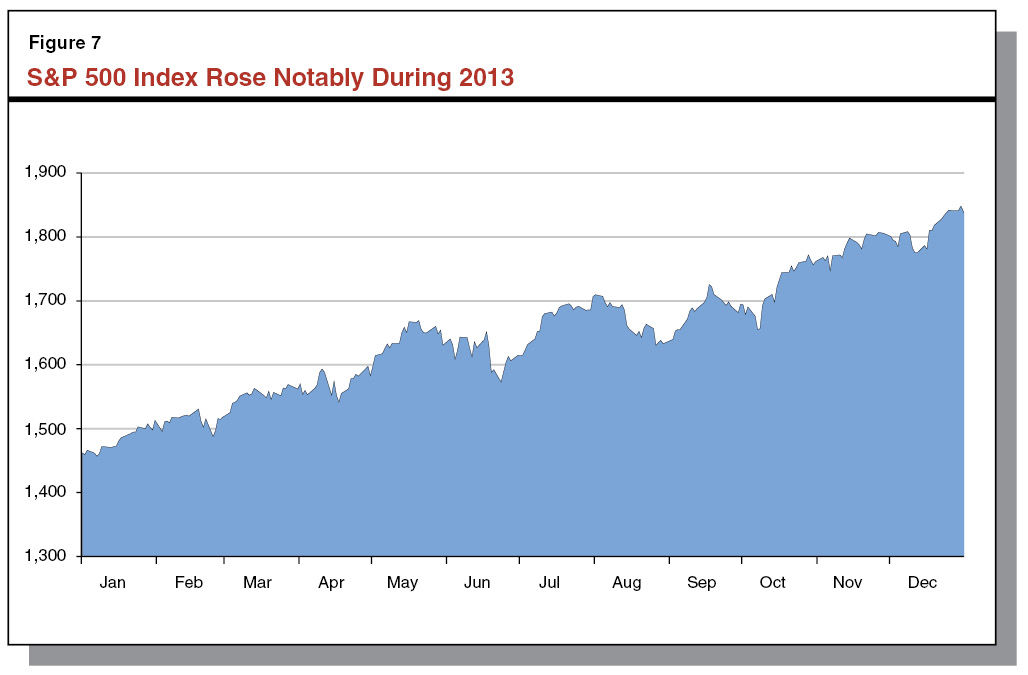

Recent Forecasts Account for 2013 Stock Gains. Figure 7 shows the upward trend of U.S. stock prices during 2013, as measured by the S&P 500 stock index. Both the administration’s revised PIT forecast and our office’s November 2013 forecast attempt to account for this development in their estimates of capital gains income. The administration’s upward PIT revenue adjustments in 2013–14 and 2014–15 result primarily from higher capital gains estimates.

Recent Data Suggest Potentially Higher PIT Revenue. Many high–income taxpayers make estimated payments throughout the year as their income materializes. December and January are important months for these payments, as year–end payments are due January 15th. December estimated payments—as well as PIT withholding—were stronger than we expected. In the next few days, we will have more information about January estimated payments. Based on recent tax collection trends, we would not be surprised at all if actual PIT revenues for 2013–14 exceeded the administration’s revised projections by a few billion dollars. This assessment definitely could change in the coming months if positive trends in stock prices were to change or if there were negative surprises in state tax collections between now and April. Nevertheless, we advise state leaders to plan for the significant possibility that revenue estimates for 2013–14 and perhaps 2014–15 will be higher when they are revised in mid–May.

State Has a Volatile Revenue System. Principally due to revenues from capital gains—paid mostly from the state’s highest–income taxpayers—the state’s revenue structure is volatile. In many years, the normal volatility of capital gains can result in annual revenues being a few billion above or below ours or the administration’s revenue forecasts. While our volatile revenue structure promotes strong growth in revenues over the longer term, its inherent uncertainty complicates budgetary planning. One of the most important tools the state can use to reduce budgetary volatility is its rainy–day reserve. Specifically, by setting aside revenues when times are good, the state can: (1) avoid ongoing spending commitments that cannot be sustained over time and (2) build up a reserve to cushion the impact of the next economic turndown.

State Constitution Contains Rainy–Day Fund Requirement. Proposition 58 (2004) created the state’s rainy–day fund, known as the BSA. Each year, Proposition 58 requires that 3 percent of estimated General Fund revenues be deposited into the BSA. Until the state’s prior deficit financing bonds are repaid, half of the annual deposit goes to accelerating the repayment of those bonds. The deposits continue until the BSA reaches either $8 billion or 5 percent of General Fund revenues, whichever is greater. Proposition 58 authorizes the Governor to suspend or reduce the amount of the deposit by executive order. The Legislature can transfer up to the entire balance of the BSA back to the General Fund by majority vote.

State’s Experience With Proposition 58. The state deposited funds into the BSA twice—in 2006–07 and 2007–08, for a total rainy–day fund of $1.5 billion—but the fund was emptied when revenues plummeted during the financial crisis. Since 2007–08, governors have suspended the BSA deposit each year.

ACA 4 Rainy–Day Fund Measure Scheduled for November 2014 Ballot. In 2010, the Legislature voted to place ACA 4 before voters. Assembly Constitutional Amendment 4 aims to increase the maximum size of the state rainy–day fund—to 10 percent of estimated General Fund revenues—when state revenues are experiencing strong growth and to limit the amount that can be withdrawn from the fund in any single year. These changes would tend to further mitigate budgetary volatility in the future. In addition, in certain circumstances, some of the funds transferred to the rainy–day fund could be used for one–time infrastructure–related purposes and for paying down other liabilities.

Deposits to Rainy–Day Fund Under ACA 4. Assembly Constitutional Amendment 4 includes two requirements for making deposits to the rainy–day fund. First, the measure continues the current practice of requiring a deposit equal to 3 percent of estimated General Fund revenues each September. Second, ACA 4 requires another deposit in May when the state is experiencing particularly strong revenue growth. Specifically, the May deposit would equal the amount by which annual estimated General Fund revenues were above (1) the historical trend of General Fund revenues or (2) the prior year’s General Fund expenditures adjusted for change in population and cost of living, whichever is less. The historical trend of General Fund revenues would be calculated each year by the Director of Finance. Specifically, the measure requires the calculation to be based on a linear regression—a statistical analysis technique—that involves adjustments to exclude the revenue effects of changes in tax policy that have been in effect for less than 20 years.

Governor’s Proposal

Budget Proposes to Replace ACA 4 With Alternate Measure. The Governor’s budget proposes a rainy–day fund that aims to reduce budgetary volatility by basing the size of a required deposit on capital gains–related revenues—the principal source of state revenue volatility. Our comments are based on the general description in the Governor’s Budget Summary and our discussions with administration staff. Specifically, the Governor’s proposal:

- Increases the Size of Rainy–Day Fund. The Governor’s proposal increases the size of the rainy–day fund to 10 percent of estimated General Fund revenues. This larger reserve would provide greater protection against unexpected revenue shortfalls.

- Amount of Deposit Based on Capital Gains Revenues. Compared with ACA 4, the Governor’s proposal uses a different method for determining the size of the annual required deposit. Specifically, we understand the Governor’s proposal would require certain projected capital gains income taxes exceeding 6.5 percent of annual General Fund revenues to be deposited to the rainy–day fund. Deposits would be “trued up” over the next two years as more capital gains and other formula data emerges.

- Creates a Proposition 98 Reserve. The Governor proposes that a portion of a required rainy–day fund deposit go into a Proposition 98 reserve (essentially, as we think of it, a dedicated reserve within the rainy–day fund). This portion would be determined by calculating the part of the increase in the Proposition 98 minimum guarantee caused by capital gains revenues over the 6.5 percent threshold described above. The Proposition 98 reserve deposit would count toward meeting the minimum guarantee in that year, but as the deposit would be held in reserve, total appropriations to schools and community colleges would be less than the minimum guarantee in the years when deposits are made. In a subsequent year, when year–to–year growth in the guarantee is insufficient to fund specified growth and cost–of–living adjustments (COLA), funds from the Proposition 98 reserve would be distributed to schools and community colleges. In this instance, the Proposition 98 reserve distributions would provide schools and colleges with funding above the minimum guarantee in some of the more difficult fiscal years. Because the minimum guarantee can be highly sensitive to changes in General Fund revenues, in some years with significant capital gains, most or all of the proposed rainy–day fund deposits under the Governor’s plan would go to the Proposition 98 reserve—meaning those funds would remain unavailable for non–Proposition 98 spending in the future.

- Limits Withdrawals. For any portion of the rainy–day fund outside of the Proposition 98 reserve, the Governor’s plan would limit the amount that can be withdrawn in the first year of a revenue downturn. Specifically, the state would be limited to withdrawing half of that part of the rainy–day fund in the first year of a downturn. For the Proposition 98 reserve itself, in certain instances, we understand that the Governor’s plan would allow the full amount to be withdrawn if needed to provide specified growth and COLA adjustments to schools and community colleges.

- Allows Funds to Be Used to Pay Down Various Liabilities. As described in the Governor’s Budget Summary, the proposal allows the amount otherwise required to be transferred to the rainy–day fund to instead be used to pay down various budgetary liabilities, such as those on the Governor’s wall of debt.

LAO Comments

Goals of Both ACA 4 and Governor’s Proposal Are the Right Ones. Assembly Constitutional Amendment 4 and the Governor’s proposal both provide mechanisms to “take money off the table” during good times in order to build larger rainy–day reserves. By doing so, either plan could reduce budgetary volatility, resulting in more predictable funding for state and local programs. The measures seek to make contributing to a rainy–day fund a regular feature of the budget process. We believe this is precisely the direction the state should be taking to improve its budgeting practices—particularly at a time when state revenues are soaring due in large part to rising stock prices.

State’s History With Constitutional Budgetary Formulas. California’s state budget system is already very complex. Formula–driven ballot measures have added considerably to this complexity. Proposition 98, as currently administered, is understood by a small number of insiders. The Gann limit, as amended by Proposition 111, has seldom played a significant role in the state budget process, and its detailed estimates—listed in obscure appendices of annual administration budget documents—are difficult to fathom. Given this experience, writing additional budgetary formulas into the Constitution could diminish the public’s already limited understanding of the state’s budget system.

Legislature Should Consider Formulas Carefully. As is likely to be the case with any rainy–day fund formula to be written into the State Constitution, both ACA 4 and the Governor’s proposal probably would produce unforeseen or unintended consequences for the state in the future. As described earlier, we understand the Governor’s proposal would require certain projected capital gains taxes exceeding 6.5 percent of annual General Fund revenues to be deposited to the rainy–day fund. As income distributions change in the future and as stock prices and capital gains grow or decline over time, this constitutional threshold could result in a stronger or weaker rainy–day fund requirement—in general, meaning less or more flexibility for the Legislature and the Governor to address their budget priorities during some periods of time. In the average and median fiscal year since the mid–1990s, capital gains taxes have made up around 7 percent of General Fund revenues. While 6.5 percent, therefore, currently represents something like a “normal year” for capital gains, that may not be the case over time. Similarly, ACA 4 contains a linear regression calculation that requires many adjustments and assumptions to be made to account for tax policy changes over the prior 20 years. We have concerns about the workability and reliability of this calculation. Given these concerns, we advise the Legislature to consider these proposed formulas carefully.

Formula–Based Decisions Often Made Using Imperfect Information. Various rainy–day fund proposals of recent years seem to assume that the data necessary to compute their formulas exists, is knowable with some certainty at a given point in time, and is not subject to interpretation. This is often not the case. For example, revenues for a given fiscal year remain uncertain for about two years, complicating calculations required by ACA 4. In addition, by May when the Legislature and Governor would finalize the estimate of capital gains and the amount of the deposit under the Governor’s proposal, the state would have no hard data on capital gains taxes for the fiscal year just ending and imperfect information for the year before that. Moreover, projections of future capital gains taxes are well known to be unreliable—a point the Governor has made forcefully during the past year. As such, locking a reserve formula into the Constitution based on capital gains projections should be considered carefully by the Legislature.

Concerns Regarding Possible Shift of Power to the Executive Branch. Under ACA 4 and the Governor’s measure, the amount of the deposits would be dependent on various estimates. Assembly Constitutional Amendment 4 contains formulas explicitly required to be compiled by the executive branch. While we understand the estimates in the Governor’s proposal would be subject to legislative review, future governors may well premise their approval of state budget bills on legislative agreement to their administrations’ formula calculations. In such a scenario, the Legislature would see more of its powers shifted to the executive branch.

Both Measures’ Effectiveness Likely Affected by Proposition 98 Interactions. Both ACA 4 and the Governor’s measure make choices regarding how Proposition 98 interacts with the non–Proposition 98 side of the budget. For example, some large influxes of revenues can result in little growth in the state’s rainy–day fund under ACA 4 due to Proposition 98. Under the Governor’s measure, in a similar year of revenue growth, nearly all of the revenues set aside for rainy–day fund purposes may sometimes go to the Proposition 98 reserve.

How Should the Legislature Proceed?

Possible Alternative Approaches. Despite our concerns, both ACA 4 and the Governor’s proposal foster a critical debate. Both aim to address one of the state’s most challenging budget problems—revenue volatility. While we think that both ACA 4 and the Governor’s proposal have meritorious features, other alternatives could be considered by the Legislature. If the Legislature wishes to place before voters a revised constitutional rainy–day fund requirement, the measure could focus on simple, incremental changes to the Proposition 58 requirement. Below, we list some options that the Legislature may wish to consider in this regard.

- Increase Size of Reserve. Increasing the size of the Proposition 58 reserve, the BSA, would provide the state greater protection against unexpected revenue shortfalls.

- Limit Amount of Withdrawals. Limiting the amount that can be withdrawn from the BSA in any single year could improve the state’s ability to mitigate budgetary shortfalls in multiyear recessions, but would diminish the ability to cover a significant budget shortfall in any single fiscal year.

- Limit Frequency of Withdrawals. Limiting the frequency of withdrawals to a specified number of years in any decade could increase the likelihood that the rainy–day fund would be used only when needed most.

- Limit Frequency of Suspensions. Limiting the frequency of BSA suspensions or reductions to a specified number of years in any decade could encourage more consistent rainy–day fund deposits.

- Consider Balance Between Proposition 98 and Other Expenditures. In amending Proposition 58—or in considering any rainy–day fund proposal—the Legislature will have to consider the extent to which the Proposition 98 and non–Proposition 98 sides of the budget, respectively, are constrained in periods when the rainy–day fund is being filled and aided when budgetary trends are weak.

- Ensure Reserve Deposit Plans Consistent With Annual Budget Agreements. Proposition 58 currently requires the Governor to decide whether to suspend or reduce scheduled transfers to the BSA no later than June 1. Yet, the Legislature passes the annual budget on June 15, and the Governor signs the budget plan on or before July 1. Proposition 58 could be amended to allow the Governor to alter his initial June 1 determination on or before July 1 to ensure the state’s rainy–day fund deposit plan is compatible with the budget plan adopted by the Legislature.

California Can Build Tradition of Sound Fiscal Stewardship. Assembly Constitutional Amendment 4 and the Governor’s proposal should lead to an important budgetary discussion by lawmakers. Regardless of the Legislature’s decision about a possible constitutional ballot measure, decisions made in this year’s budget process can begin a new tradition of setting aside revenues when times are good to provide a cushion for when revenues decline. The Governor’s budget proposal to reinstate the annual deposit to the BSA, for example, could create a strong precedent for accumulating reserves during good revenue times. Further, the proposal is evidence that the Proposition 58 mechanism can work. If revenue estimates rise even more between January and May, the Legislature and the Governor have the chance to build an even larger reserve than the Governor proposes this year. Through actions such as these, the state can establish a tradition of sound fiscal stewardship—with or without any proposed constitutional change.

Longstanding Funding Problems. CalSTRS has not been appropriately funded for much of its 100–year history. Simply put, CalSTRS is not funded enough to ensure its solvency over the long term. Moreover, state law does not even make clear who is responsible for providing more funding to the system: teachers, districts, or the state. The basic pension math is clear—CalSTRS must receive more money. In our view, now is the time for action to begin addressing this very difficult problem.

30–Year, Full–Funding Plan Should Be Focus Now. We agree with the Governor that the key goal of the state should be developing a plan of shared responsibility to achieve a fully–funded, sustainable teachers’ pension system within about 30 years. The CalSTRS board has stated that this is the “definitive approach” to addressing the system’s funding problem. This will be a very expensive proposition, potentially requiring around $5 billion per year initially (growing over time) in extra resources from some combination of the state, districts, and teachers. This amount will remain substantial over the long term regardless of the fact that stock prices have been growing recently.

Setting Aside Some Money Now Would Be Smart. The Governor suggests that state officials and the education community attempt to come to agreement on how the state, districts, and teachers respectively will fund CalSTRS over the long term. In the meantime, however, a portion of the state’s 2014–15 budget reserve could be set aside in anticipation of making the first deposit to CalSTRS after development of a new long–term funding plan over the next year or two. In any event, the responsibility to adopt a solution will in the end rest squarely with the Legislature and the Governor.

Over the Long Term, the State’s Role Should Change. The Governor’s budget summary comments that the state’s long–term role as a direct contributor to CalSTRS should be evaluated. We agree. Employers and employees should be partners in defined benefit pension systems, and the state is not the employer of California’s public school teachers. In our November 2011 publication on the Governor’s initial pension proposal, we noted that the state can—and probably should—play a key role in addressing the large unfunded liability that exists for past and current teachers’ benefits. We also have suggested that the state create a plan for future teachers’ benefits to be paid completely by districts and teachers over the long term.

Proposition 98 funds K–12 education, the California Community Colleges (CCC), preschool, and various other state education programs. The Governor’s budget includes $11.8 billion in Proposition 98 spending increases. Of that amount, $7.6 billion is designated as 2014–15 Proposition 98 spending, $3.7 billion is additional funding attributable to 2012–13 and 2013–14, and $503 million is attributable to earlier years. Of the $11.8 billion, $6.8 billion is designated for one–time purposes and $5 billion for ongoing purposes. Under the Governor’s budget, ongoing K–12 per–pupil funding would increase from $7,936 in 2013–14 to $8,724 in 2014–15—an increase of $788 (10 percent).

Changes to the Minimum Guarantee

2012–13 Minimum Guarantee Up $1.9 Billion. As Figure 8 shows, the administration’s revised estimate of the 2012–13 minimum guarantee is $58.3 billion, a $1.9 billion increase from the estimate made at the time the 2013–14 budget plan was enacted. Of the increase in the minimum guarantee, roughly $1.8 billion is due to General Fund revenues being $1.7 billion higher than assumed in the 2013–14 budget plan, and the remainder is due to an increase in baseline property tax revenues. (The 2012–13 minimum guarantee is a “Test 1” year, in which increases in property tax revenues result in higher funding for schools and community colleges.) Though the Governor’s estimate of the minimum guarantee has increased, his estimate of 2012–13 Proposition 98 spending is $130 million lower, primarily due to lower–than–expected student attendance. The higher minimum guarantee combined with lower–than–expected costs create a total “settle–up” obligation of $2 billion.

Figure 8

Increase in 2012–13 and 2013–14 Proposition 98 Minimum Guarantees

(In Millions)

|

|

2012–13

|

|

2013–14

|

|

Budgeted

|

Revised

|

Change

|

Budgeted

|

Revised

|

Change

|

|

Minimum Guarantee

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

General Fund

|

$40,454

|

$42,207

|

$1,752

|

|

$39,055

|

$40,948

|

$1,893

|

|

Local property tax

|

16,011

|

16,135

|

124

|

|

16,226

|

15,866

|

–361

|

|

Totals

|

$56,465

|

$58,342

|

$1,877

|

$55,281

|

$56,813

|

$1,532

|

2013–14 Minimum Guarantee Up $1.5 Billion. The administration’s revised estimate of the 2013–14 minimum guarantee is $56.8 billion, a $1.5 billion increase from the amount assumed in the 2013–14 budget plan. This increase is due to the higher 2012–13 minimum guarantee and higher year–to–year growth in per capita General Fund revenues, offset slightly by lower–than–anticipated growth in student attendance. Though the minimum guarantee is up $1.5 billion, the state’s General Fund Proposition 98 requirement is up by $1.9 billion due to estimates of local property tax revenues decreasing by $361 million. The Governor also has a revised estimate of 2013–14 spending, which is down $150 million primarily due to lower–than–expected student attendance. The higher minimum guarantee combined with lower–than–expected costs creates a 2013–14 settle–up obligation of $1.7 billion.

2014–15 Minimum Guarantee $4.7 Billion Above Revised 2013–14 Level. As Figure 9 shows, the Governor’s budget proposes $61.6 billion in total Proposition 98 funding for 2014–15. This is $4.7 billion higher than the revised 2013–14 spending level. The increase is driven by strong growth in General Fund revenue and increases in property tax revenues. (Test 1 is operative in 2014–15, such that marginal increases in property tax revenues—except for RDA asset revenues—are resulting in a higher Proposition 98 minimum guarantee.)

Figure 9

Proposition 98 Funding

(Dollars in Millions)

|

|

2012–13 Revised

|

2013–14 Revised

|

2014–15 Proposed

|

Change From 2013–14

|

|

Amount

|

Percent

|

|

Preschool

|

$481

|

$507

|

$509

|

$2

|

—

|

|

K–12 Education

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

General Fund

|

$37,740

|

$36,361

|

$40,079

|

$3,718

|

10%

|

|

Local property tax revenue

|

13,895

|

13,633

|

14,171

|

537

|

4

|

|

Subtotals

|

($51,634)

|

($49,995)

|

($54,250)

|

($4,255)

|

(9%)

|

|

California Community Colleges

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

General Fund

|

$3,908

|

$4,001

|

$4,396

|

$395

|

10%

|

|

Local property tax revenue

|

2,241

|

2,232

|

2,326

|

94

|

4

|

|

Subtotals

|

($6,149)

|

($6,233)

|

($6,723)

|

($489)

|

(8%)

|

|

Other Agencies

|

$78

|

$78

|

$77

|

–$1

|

–1%

|

|

Totals

|

$58,342

|

$56,813

|

$61,559

|

$4,746

|

8%

|

|

General Fund

|

$42,207

|

$40,948

|

$45,062

|

$4,115

|

10%

|

|

Local property tax revenue

|

16,135

|

15,866

|

16,497

|

631

|

4

|

Wall of Debt Proposal

One of the largest components of the Governor’s budget plan is his proposal to retire all wall of debt obligations, including school and community college obligations, by the end of 2017–18. The state currently has a total of $11.5 billion in such outstanding school and community college obligations—$6.2 billion in deferrals (late payments), $4.5 billion in unpaid mandate claims, $462 million for ERP, and $410 million for the Quality Education Investment Act (QEIA). (The state also has a $1.5 billion outstanding Proposition 98 settle–up obligation, which can be used to pay off the obligations mentioned above.) We discuss the Governor’s plan for retiring these obligations below.

Retires All School and Community College Deferrals by End of 2014–15. The Governor proposes to pay down all $6.2 billion in outstanding school and community college deferrals by the end of 2014–15. As Figure 10 shows, the Governor designates Proposition 98 funding from 2012–13, 2013–14, and 2014–15 to pay down these deferrals. Under the Governor’s plan, all higher Proposition 98 spending proposed in 2012–13 and 2013–14 is used for deferral pay downs. About one–third of the new spending proposed for 2014–15 is for deferral pay downs.

Figure 10

Governor Proposes to Pay Down All Outstanding K–14 Deferrals

(In Millions)

|

|

K–12

|

CCC

|

Totals

|

|

Pay down scored to:

|

|

|

|

2012–13

|

$1,813

|

$194

|

$2,007

|

|

2013–14

|

1,520

|

163

|

1,683

|

|

2014–15

|

2,238

|

236

|

2,474

|

|

Total Proposed Deferral Pay Down

|

$5,571

|

$592

|

$6,164

|

Makes Final $410 Million QEIA Payment. QEIA provides funding to low–performing schools for various improvement activities and to community colleges for career technical education. Through the QEIA program, the state is providing additional funds to schools and community colleges as part of a Proposition 98 settle–up agreement relating to 2004–05 and 2005–06. Although statute requires a $410 million payment to fully retire the state’s 2004–05 and 2005–06 settle–up obligations, the estimated costs of the QEIA program in 2014–15 are $316 million. (Fewer schools are now participating in the program.) The Governor proposes to redirect the $94 million in freed–up funds to the ERP (as discussed further below).

Provides $188 Million for ERP. The ERP was created in 2004 through legislation associated with the Williams settlement and is intended to provide low–performing schools with a total of $800 million for emergency facility repairs. Of the $188 million proposed for ERP in 2014–15, $94 million is being redirected from free–up QEIA funds (mentioned above) and $94 million is coming from unspent prior–year Proposition 98 funds. Under the Governor’s proposal, the state would have $274 million in outstanding ERP obligations at the end of 2014–15.

Retires Remaining Wall of Debt Obligations by End of 2017–18. The Governor proposes to retire all remaining wall of debt obligations in the following three years, with all obligations paid off by 2017–18. In 2015–16, the Governor would provide $1.5 billion to retire the state’s outstanding Proposition 98 settle–up obligation. Because settle–up payments can be provided to schools and community colleges for any purpose, the Governor proposes to dedicate these settle–up funds for repaying the remaining $274 million owed for ERP and paying off $1.2 billion in outstanding mandate claims. The remaining $3.2 billion in mandate–claim payments would be spread across 2016–17 and 2017–18.

Other Major Proposition 98 Proposals

Figure 11 shows all major changes to Proposition 98 spending in 2014–15. As the figure shows, the budget provides $7.6 billion in policy–related spending increases. Of this amount, $5.2 billion reflects program augmentations and $2.5 billion is for paying down the last of school ($2.2 billion) and community college ($236 million) deferrals. As shown in the figure, the largest programmatic augmentation is for the school district LCFF. We discuss this and other notable proposals below. For community colleges, we discuss the Governor’s Student Success and Support Program (SSSP) proposal later in the “Higher Education” section of this report and the Governor’s $175 million maintenance–related proposal later in the “Infrastructure” section.

Figure 11

Increases in 2014–15 Proposition 98 Spending

(In Millions)

|

Accounting Adjustments

|

|

|

Remove prior–year one–time actions

|

–$2,423

|

|

Fund QEIA program outside of Proposition 98

|

–361

|

|

Adjust energy efficiency funds

|

–101

|

|

Subtotal

|

(–$2,885)

|

|

Policy Changes

|

|

|

Fund increase in school district LCFF

|

$4,472

|

|

Pay down remaining deferrals (one–time)

|

2,474

|

|

Augment CCC Student Success and Support Program

|

200

|

|

Augment CCC maintenance and instructional equipment (one–time)

|

175

|

|

Fund 3 percent CCC enrollment growth

|

155

|

|

Provide 0.86 percent COLA to select K–14 programs

|

82

|

|

Increase funding for K–12 pupil testing

|

46

|

|

Fund increase in COE LCFF

|

26

|

|

Other changes

|

1

|

|

Subtotal

|

($7,631)

|

|

Total Changes

|

$4,746

|

Provides $4.5 Billion for LCFF Increases. The proposed $4.5 billion increase in LCFF funding reflects an 11 percent year–to–year increase and is estimated to close 28 percent of the remaining gap between school districts’ 2013–14 funding levels and the LCFF full implementation rates. Under the Governor’s proposal, we estimate the 2014–15 per pupil LCFF funding level would be approximately 80 percent of the full implementation rates. The Governor also proposes to add two categorical programs to the LCFF—Specialized Secondary Programs ($4.8 million) and agricultural education grants ($4.1 million). Under the Governor’s proposal, school districts receiving funding for these two programs in 2013–14 would have those funds count towards their LCFF targets beginning in 2014–15. (No change would be made to the LCFF target rates.) The currently required categorical activities would be left to districts’ discretion. The Governor’s plan also provides county offices of education (COEs) with an additional $26 million in LCFF funding. The administration projects that this increase will be sufficient to provide COEs their full LCFF target rates in the budget year.

Proposes New Automated Budget Formula for LCFF Funding. The Governor proposes statutory language requiring that a specified percentage of annual Proposition 98 funding automatically be dedicated to LCFF each year (the exact percentage has yet to be determined). Under current law, prior–year LCFF appropriations are continuously appropriated—that is, these appropriations are automatically made to school districts, even without an approved state budget. Increases in LCFF funding, however, are made at the discretion of the Legislature and must be approved in the annual budget. Under the Governor’s proposal, the Legislature effectively would have no role in making this key determination moving forward.

Other Changes to Existing Programs. The Governor’s budget plan includes several other notable changes. The budget provides $82 million to fund a 0.86 percent COLA for most K–12 categorical programs and community college apportionments. The Governor also provides a $46 million increase for pupil testing to reflect the higher cost of administering new standardized tests aligned to the Common Core State Standards. The budget also reflects a $101 million reduction in funding for Proposition 39 energy projects. (The Governor estimates that the amount of corporate tax revenues deposited into the Clean Energy Job Creation Fund in 2014–15 will be $101 million lower than assumed in the 2013–14 budget plan, thus requiring a corresponding reduction in funding.) To accommodate the reduction, the Governor provides no additional funding in 2014–15 for the revolving loan program ($28 million savings) and reduces school and community college grants by $65 million and $8 million, respectively. The Governor also proposes to add three mandates—Uniform Complaint Procedures, Public Contracts, and Charter Schools IV—to the Mandate Block Grant. Given none of the three mandates is relatively costly, the Governor’s plan does not provide an associated increase in block grant funding.

Proposes Simplification of Rules for Independent Study. To facilitate the use of online instruction, the Governor proposes to create a simplified independent study program for grades 9–12. Current independent study programs require that each student assignment within a course be translated into an equivalent number of classroom hours for purposes of generating funding. Under the Governor’s proposal, independent study programs alternatively could choose to translate each course into an equivalent number of hours for purposes of generating funding. The Governor also proposes to allow student–teacher ratios in these courses to exceed limits established by current law, provided these changes are collectively bargained by local education agencies.

Governor’s Overall Proposition 98 Plan Reasonable

Plan Contains Prudent Mix of One–Time and Ongoing Spending. We believe the Governor’s Proposition 98 plan provides a reasonable mix of programmatic funding increases and pay downs of outstanding obligations. By retiring the $6.2 billion in outstanding K–14 deferrals, the plan would eliminate the largest component of the school and community college wall of debt. Dedicating a substantial amount of new funding to one–time purposes also helps the state minimize any future disruption in school funding as a result of revenue volatility or an economic slowdown. Though a significant amount of funding is dedicated to one–time purposes in the Governor’s plan, his plan also significantly increases LCFF funding and provides a variety of community college augmentations, thereby building up ongoing programmatic support.

2014–15 Minimum Guarantee Very Sensitive to Changes in General Fund Revenues. Because 2014–15 is a Test 1 year in which a relatively large maintenance factor payment is required, marginal increases or decreases in General Fund revenues can result in dollar–for–dollar changes in the minimum guarantee. (As we’ve previously discussed, this is driven by the state’s approach to paying maintenance factor in Test 1 years.) As a result, estimates of the 2014–15 minimum guarantee will be highly sensitive to changes in General Fund revenues and could experience large swings over the coming months. This volatility and associated swings in the guarantee makes a prudent mix of one–time and ongoing support particularly important.

Concerns With Proposal to Automate Future LCFF Funding Increases. Though we believe the Governor’s overall Proposition 98 plan is reasonable, we have concerns with his proposal to set in statute the specific share of Proposition 98 funding that would be dedicated to LCFF each year moving forward. Though we believe the bulk of future K–12 funding increases should be dedicated to funding LCFF, we are concerned that such an approach would remove the Legislature’s discretion to appropriate funding and make key budget decisions. Given the considerable loss of associated legislative authority and discretion, we recommend the Legislature reject this proposal.

California’s publicly funded higher education system consists of UC, CSU, CCC, Hastings College of the Law (Hastings), the California Student Aid Commission (CSAC), and the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine (CIRM). As shown in Figure 12, the Governor’s budget provides $13 billion in General Fund support for higher education in 2014–15. This is $1.2 billion (10 percent) more than the revised current–year level.

Figure 12

Higher Education General Fund Support

(Dollars in Millions)

|

|

2012–13 Actual

|

2013–14 Revised

|

2014–15 Proposed

|

Change From 2013–14

|

|

Amount

|

Percent

|

|

University of California

|

$2,566

|

$2,844

|

$2,987

|

$142

|

5%

|

|

California State Universitya

|

2,473

|

2,789

|

2,966

|

177

|

6

|

|

California Community Collegesb

|

4,269

|

4,390

|

4,828

|

438

|

10

|

|

California Student Aid Commissionc

|

1,559

|

1,682

|

1,904

|

222

|

13

|

|

California Institute for Regenerative Medicine

|

53

|

97

|

284

|

187

|

193

|

|

Hastings College of the Law

|

9

|

10

|

11

|

1

|

13

|

|

Awards for Innovation in Higher Education

|

—

|

—

|

50

|

50

|

N/A

|

|

Debt–service obligationsd

|

(1,027)

|

(1,027)

|

(1,255)

|

(228)

|

(22)

|

|

Totals

|

$10,930

|

$11,812

|

$13,030

|

$1,218

|

10%

|

Major Higher Education Proposals

The majority of the new funding is for base increases at the universities, increases in apportionment funding and two categorical programs at the community colleges, repaying bonds that support CIRM research, as well as increased participation in Cal Grants and implementation of the new Middle Class Scholarship program.

Proposes Increase in General Purpose Funding for Universities. The Governor proposes unallocated base budget increases of $142 million each for UC and CSU in 2014–15. These increases represent the second annual installment in a four–year funding plan proposed by the Governor last year. Under this plan, the universities, which received 5 percent base funding increases in the current year, would receive the proposed 5 percent increase in 2014–15, followed by 4 percent increases in each of the subsequent two years. (The increases for both universities are based on 5 percent of UC’s support budget, resulting in an increase of 5.6 percent for CSU.) About $10 million of CSU’s increase is related to a new proposed process for funding capital projects (discussed later in the “Infrastructure” section of this report).

No Enrollment Targets for Universities. Similar to last year, the Governor does not propose enrollment targets or enrollment growth funding for the universities. The Governor’s budget documents show resident enrollment flat in the budget year at UC, growing by 2 percent at CSU, and decreasing by 8 percent at Hastings. (The administration indicates these enrollment levels are shown for “display purposes only and do not constitute an enrollment plan.”)

Assumes No Tuition Increases. Although the Governor acknowledges in his budget summary that college is relatively affordable for California’s public–college students (due to high public subsidies, relatively low tuition and fees, and robust financial aid programs), he conditions his proposed annual funding increases for the universities on their maintaining tuition at current levels. Under his plan, tuition levels, which have not increased since 2011–12, would remain flat through 2016–17.