Introduction

In 2009, the Legislature adopted the California Private Postsecondary Education Act to protect the interests of students attending private universities, colleges, and technical schools in the state. The act set minimum standards for private postsecondary institutions operating in the state, created a new oversight bureau for these schools, and exempted several types of institutions from bureau oversight, including institutions accredited by any of six regional associations. The legislation directs our office to examine: (1) the extent to which regional and national accreditors oversee institutions and protect student interests, (2) whether that oversight results in the same student protections as oversight by the new bureau, and (3) whether current exemptions from bureau oversight should be continued, adjusted, or removed. This report fulfills that statutory requirement.

In the first half of the report, we describe different types of postsecondary schools, explain the basic framework for regulation of private postsecondary schools, and provide a brief review of California’s regulatory efforts over the last 35 years. The second half of the report contains our analysis of the oversight provided by accreditors and the bureau under California’s current regulatory system, as well as our recommendations for adjusting exemptions from oversight moving forward. The recommendations are intended to close a gap in oversight for certain now–exempt institutions while limiting the new regulatory burden placed on them. We also suggest allowing other institutions voluntarily to participate in the new, more limited state oversight process to help them meet certain new federal requirements.

Background

Postsecondary Schools

Two Main Types of Postsecondary Schools. Higher education institutions in the United States are classified into various sectors based on who controls the institution. The two main sectors are (1) the public (or state) sector, consisting primarily of community colleges, state colleges, and universities; and (2) the private sector, including nonprofit and for–profit schools. Most public and nonprofit colleges offer a wide range of academic programs in the liberal arts and sciences, as well as technical fields, and award various types of degrees. Nonprofit schools typically are founded by charitable or religious organizations. These institutions are accountable to volunteer governing boards whose members are prohibited by law from benefiting financially from the institutions. By comparison, for–profit colleges are more likely to focus on a narrower range of disciplines, be vocationally oriented, and offer programs of shorter length that result in certificates rather than baccalaureate degrees. For–profit institutions may be owned by individuals or families, stockholders of a publicly traded corporation, or private investors with large capital investments in a school or group of schools. Publicly–traded for–profit institutions are accountable by law for the financial returns they produce for their owners/shareholders.

Wide Range of Postsecondary Schools in California. California public institutions include the 112 California Community Colleges, 23 California State University campuses, and 10 University of California campuses. California has nearly 200 nonprofit schools (often referred to as independent institutions), including Stanford University, Saint Mary’s College, and the California College of the Arts. California has more than 1,000 for–profit colleges, including the University of Phoenix, ITT Technical Institute, Academy of Art University, and Citrus Heights Beauty College.

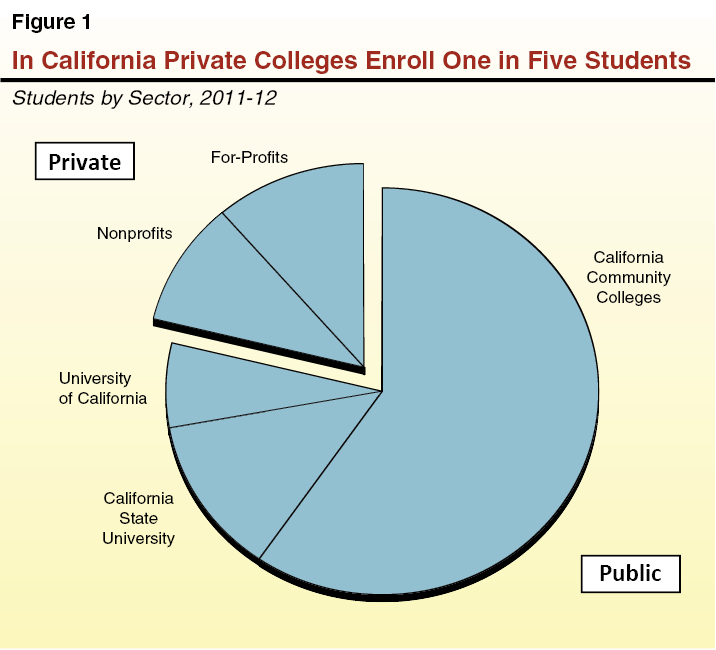

About One in Five College Students in California Attends Private Sector. In 2011–12, of 3.7 million students attending college in California, nearly 3 million were enrolled in the public sector and almost 800,000 (or 21 percent) were enrolled in the private sector. As reflected in Figure 1, 10 percent of college students were enrolled in nonprofit schools, with 11 percent enrolled in for–profit schools. The proportion of college students attending for–profit schools has grown in recent years while the share in each of the other segments has been declining slightly. In 2002–03, for example, the share of students enrolled in for–profit schools was 5 percent.

Concerns About For–Profit Colleges. For–profit colleges have received considerable attention in recent years. Some of this attention has been positive, including studies highlighting the role of these colleges in fostering innovation and increasing the number of graduates in California. Much attention, however, has been critical of the sector, with particular concern that the more intense business pressures that for–profit schools face sometimes adversely affect students. Regulators have determined that students are at greater risk of exploitation at for–profit institutions than at other postsecondary institutions. Investigations of for–profit schools suggest that some of these schools have offered low value educational programs at a high cost to students and taxpayers, resulting in poor academic and financial outcomes for students. For example, a United States Senate investigation noted that while for–profit schools enroll between 10 percent and 13 percent of postsecondary students nationally, they receive 25 percent of financial aid dollars and account for nearly half of all federal student loan defaults. Numerous other investigations, including inquiries by the United States Government Accountability Office and state attorneys general (AGs) have identified poor student outcomes, high costs, and misleading or deceptive recruitment practices at a number of for–profit schools.

Regulatory Triad

In the United States, three independently acting entities—the federal government, accrediting bodies, and state agencies—oversee postsecondary institutions. This regulatory structure is referred to as the regulatory triad. The purpose of this structure is to ensure that postsecondary institutions serve the interests of taxpayers, students, and employers.

The United States Department of Education (USED) Sets Standards for Institutions Participating in Federal Student Financial Aid Programs. The goal of the USED’s rules for institutional participation in federal student aid programs is to ensure that federal student aid is directed only to institutions and academic programs that meet minimum standards. These standards require financial stability, limit the proportion of an institution’s total revenue that may be federal aid, and set maximum student loan default rates for institutions, among other requirements. These federal rules strongly influence institutional behavior because federal financial aid (student loans, grants, and work study funds that cover tuition and other student expenses) affects schools’ ability to attract students.

Accreditors Verify Institutions Meet Acceptable Levels of Educational Quality. One of USED’s requirements for institutions participating in federal student aid programs is that they be accredited by a federally recognized accrediting agency. These accrediting agencies have two primary roles: (1) develop and enforce a set of minimal standards necessary for institutions to maintain accreditation (and by extension, eligibility for federal student aid programs), and (2) promote best practices and encourage continual improvement among accredited institutions.

Two Main Types of Accreditation. Institutions can be accredited by regional or national agencies. Federal authorities recognize six regional associations to accredit degree–granting institutions within specified areas of the United States. All public institutions and most degree–granting private nonprofit colleges are regionally accredited. These institutions serve the vast majority of college students. Increasingly, large for–profit institutions also are becoming regionally accredited. Six national accreditors, by contrast, oversee most non–degree granting, career–related postsecondary schools, in addition to many degree–granting but more specialized or vocationally oriented schools. These national accreditors are organized by discipline area or type of school—for example, career colleges or online institutions—instead of by geographic region. Nationally accredited schools serve less than 10 percent of all college students. In addition to these two types of institutional accreditors, a number of specialized and programmatic accreditors oversee specialty schools and programs within schools—such as stand–alone schools of nursing and departments of nursing within universities. Specialized schools serve less than 2 percent of college students. Figure 2 summarizes the different types of accrediting agencies recognized by USED.

Figure 2

Three Types of Accreditors

Federally Recognized Accrediting Agencies

|

|

Regional

|

National

|

Specialized

|

|

Number of Agencies

|

6

|

6

|

45

|

Types of Institutions

|

- Degree–granting colleges and universities

- All public schools and most nonprofit schools

|

- Mostly career–related schools

- Most for–profit schools

|

- Specialty schools, programs within schools

- Mix of school types

|

|

List of Agenciesa

|

Middle States Commission on Higher Educatio

|

Accrediting Commission of Career Schools and Colleges

|

Accreditation Commission for Education in Nursing

|

|

|

New England Association of Schools and Colleges

|

Accrediting Council for Continuing Education and Training

|

Commission on Accrediting of Association of Theological Schools

|

|

|

North Central Association of Colleges and Schools Higher Learning Commissio

|

Accrediting Council for Independent Colleges and Schools

|

Commission on Accreditation of National Association of Schools of Music

|

|

|

Northwest Commission on Colleges and Universities

|

Council on Occupational Education

|

Commission on Massage Therapy Accreditation

|

|

|

Southern Association of Colleges and School

|

Distance Education and Training Council

|

Legal Education Section Council of American Bar Association

|

|

|

Western Association of Schools and Colleges

|

Transnational Association of Christian Colleges and Schools

|

National Council for Accreditation of Teacher Education

|

States’ Main Role Is to Protect Students From Unfair Business Practices. State licensing agencies are responsible for overseeing most private postsecondary schools within a state, whether or not they are accredited. These agencies have three broad roles:

- Authorize private postsecondary schools to operate within the state.

- Enforce state regulatory requirements regarding postsecondary education. These regulations typically focus on traditional consumer protection issues, such as prohibiting unfair, deceptive, or abusive business practices and requiring bonds or tuition recovery funds to protect students when institutions close.

- Collect and resolve student complaints about authorized institutions.

For Some Institutions, State Sole Oversight Agency. Some institutions are unaccredited and thus ineligible for federal student aid. As a result, they are not subject to federal or accreditor oversight, leaving the state as the sole oversight body for these institutions. For this reason, state regulations for these agencies typically include minimum educational quality standards in addition to more traditional consumer protection standards.

New “State Authorization” Rule. Effective July 2014, USED will require states to take a more active role in approving schools. Specifically, under this new state authorization rule, USED will require an institution participating in its federal aid programs to receive explicit state approval. This means the state may no longer exempt institutions from state oversight based on accreditation, number of years in operation, or other comparable exemptions. The rule also requires the state to have a process for reviewing and acting upon student complaints about the institution.

California’s Long History of Struggling to Oversee Private Colleges

Two Diverging State Regulatory Philosophies. For more than three decades, California has struggled to provide effective oversight of private postsecondary schools. One of the reasons effective regulation has been difficult to establish is tension between distinct schools of thought about the goals of regulation. One perspective emphasizes student protection through performance standards, while another relies on public disclosure of costs and benefits. Under the first regulatory approach, institutions that fail to meet minimum standards for educational quality, student outcomes, and business practices are not permitted to operate. Under the second regulatory approach, institutions have broader latitude to operate regardless of student outcomes, but must disclose information about their costs, accreditation, and results, enabling students to make informed decisions about their schooling. Oversight frameworks typically incorporate aspects of both perspectives.

Three Major Regulatory Laws Enacted Between 1977 and 1989

Superintendent of Public Instruction (SPI) Was Responsible for Regulation Under 1977 Law. Chapter 1202, Statutes of 1977 (AB 911, Arnett), also known as The Private Postsecondary Education Act, charged the SPI with protecting the integrity of degrees and diplomas conferred by private postsecondary institutions. Chapter 1202 created an advisory council with equal representation from leaders of regulated institutions and members of the public. The SPI created a division within the California Department of Education to carry out regulatory duties. Under the 1977 law, the division reviewed unaccredited institutions for compliance with the law. It accepted accreditation in lieu of state review and oversight for licensure of accredited schools.

Over Ensuing Years, Several Significant Problems Highlighted. State reports regarding this period describe poor oversight of the unaccredited institutions and lax enforcement of regulations. By the late 1980s, a number of private institutions were granting degrees of questionable value, in some cases without requiring students to complete academic requirements, and California developed a reputation as the “diploma mill capital of the world.” Many schools were aggressively recruiting students without regard for their ability to complete or benefit from the schools’ educational programs. These schools often benefited significantly from public funding (by primarily using public financial aid grants to cover their costs) without providing commensurate public or student benefits.

New Regulatory Law Enacted in 1989 Transferred Oversight Responsibility to New Council. Responding to these concerns, the Legislature adopted Chapter 1307, Statutes of 1989 (SB 190, Morgan), also known as The Private Postsecondary and Vocational Education Reform Act (Reform Act). The Reform Act transferred responsibility from the SPI to a new, 20–member Council for Private Postsecondary and Vocational Education (Council) with 6 institutional representatives and 14 state officials and representatives of the public. The act established separate approval processes for degree–granting institutions and those granting only certificates or other credentials, and required schools to provide partial refunds to students withdrawing from programs. It also required institutions to provide prospective students of certain programs with a “school performance fact sheet” disclosing completion rates, passage rates for related licensure and certification exams, job placement, and average starting wages of program graduates. (While the act required disclosure of these outcomes, it did not set minimum standards for performance. These were established in companion legislation enacted in the same year.) The act contained a number of exemptions, including religion programs at nonprofit religious institutions; educational programs offered by trade, professional, or other associations solely for their membership; and institutions accredited by the Western Association of Schools and Colleges (WASC) if they were nonprofit schools or for–profit schools providing only degree programs of two or more years.

Companion 1989 Law Complemented Reform Act . . . In the same year, Chapter 1239, Statutes of 1989 (AB 1420, Waters), The Maxine Waters School Reform and Student Protection Act (Waters Act), also was adopted. This legislation complemented Chapter 1307 in that it established minimum performance standards in certain areas, including course completion and job placement.

. . . And Conflicted With Reform Act. Other provisions of the Waters Act, however, created duplicative or conflicting requirements. With both laws in place, the Education Code contained different and sometimes conflicting standards, sanctions, and refund requirements, depending on which provisions applied in a given situation. Some institutions were exempted from provisions of one act but not the other. The result was a fragmented regulatory structure that often was difficult to interpret. At times, the Council (and later a successor bureau) was unable to determine whether it had authority to act upon an institution’s application.

1989 Reforms Did Not Resolve All Existing Problems, Added New Ones. Despite two major legislative efforts to improve oversight of private postsecondary education in 1989, hundreds of unapproved institutions continued to operate in the state in violation of the law. Reviews determined that the Council provided inadequate student protection and lacked the enforcement authority and sanctions to bring schools into compliance with regulations. At the same time, regulated institutions raised objections to burdensome regulatory fees and the lack of an appeal process for Council decisions.

Oversight Transferred to New Bureau, but Problems Persisted. Chapter 78, Statutes of 1997 (AB 71, Wright), transferred the Council’s duties to a new bureau within the Department of Consumer Affairs (DCA). Difficulties, however, continued under DCA. Several reviews between 2000 and 2005 identified ongoing and new problems with nearly every significant component of the state’s regulatory program.

Laws Sunset, Followed by Period With No Regulation. Following two extensions of their sunset dates, the 1989 laws expired in July 2007. The expiration of these laws left the state without regulatory authority to oversee private postsecondary schools. During this time, legislation urged institutions to maintain voluntary compliance with the previous standards, even though the standards were no longer operative. In addition to schools that had been approved under the 1989 laws (or had been operating without approval), many new institutions began offering programs in California because of the regulatory vacuum.

2009 Legislation Created New Regulatory Structure

After a number of failed attempts to create a new regulatory structure, the Legislature and Governor passed Chapter 310, Statutes of 2009 (AB 48, Portantino), the California Private Postsecondary Education Act (Private Postsecondary Act). The new act created the current Bureau for Private Postsecondary Education (Bureau) under DCA to oversee the state’s private postsecondary schools and established a single set of rules for institutions subject to state oversight.

Three Major Goals of 2009 Legislation. The main goals of the Private Postsecondary Act are to: (1) ensure minimum educational quality standards at private postsecondary schools in the state, (2) provide meaningful student protections and an appropriate level of oversight, and (3) prevent public deception associated with fraudulent or substandard degrees. The legislation also aims to establish a governance structure that provides for accountability and legislative oversight, as well as a regulatory process that allows all stakeholders to have a voice.

Bureau’s Major Functions Reflect Goals. The Bureau is tasked with performing a number of oversight functions reflecting these goals:

- Licenses Institutions and Programs Meeting Minimum Standards. The Bureau licenses most private colleges in California. To be licensed, unaccredited institutions must demonstrate to the Bureau that they meet minimum educational quality and operating standards. Accredited institutions under Bureau oversight are subject to the same minimum statutory and regulatory standards. In practice, however, these institutions may gain approval through an abbreviated procedure (termed approval by means of accreditation) that relies on the accreditation process to ensure educational quality. For both types of schools, once they are approved, the Bureau conducts regular compliance inspections to ensure that they meet all Bureau standards including educational quality standards.

- Monitors Fair Business Practices. The Bureau oversees the business practices of private colleges, including their marketing and recruitment practices; disclosures through enrollment agreements, school catalogs, and performance reports; and tuition policies including prepayment, cancellations, and refund rules. In order to enforce regulations relating to fair business practices, the Private Postsecondary Act requires the Bureau to regularly conduct announced and unannounced compliance inspections at each regulated institution.

- Resolves Student Complaints. The Bureau is responsible for responding to and helping to resolve student complaints about the institutions it oversees. The Bureau can require an institution to pay restitution to students if it finds that the institution caused harm to those students by a violation of the Private Postsecondary Act.

All Regionally Accredited Postsecondary Schools Exempt From Bureau Oversight. Some private institutions are exempt from Bureau oversight. This means they do not need to be licensed to operate in the state. One of the main exemptions is based on an institution’s accreditation. As illustrated in Figure 3, the Private Postsecondary Act exempts regionally accredited schools from Bureau oversight. (Institutions accredited by one of the national accreditors, on the other hand, generally are subject to some Bureau oversight.)

A Few Other Types of Institutions Also Exempt. In addition to the exemption based on regional accreditation, the Private Postsecondary Act includes a number of other exemptions from Bureau oversight. Figure 4 lists all current exemptions from the act.

Figure 4

Institutions Currently Exempt From Bureau Oversight

|

Exemptions Relying on Some Form of Accreditation:

|

|

Colleges and universities accredited by Western Association of Schools and Colleges.

|

|

Institutions accredited by another regional accrediting agency.

|

|

Accredited nonprofit institutions that have operated in the state for at least 25 years, have student loan default rates below 10 percent, and meet certain other requirements, including maintaining specified financial ratios and refund policies.

|

|

Accredited nonprofit workforce development and rehabilitation services.

|

|

Law schools accredited or approved by the American Bar Association or Committee of Bar Examiners of the California State Bar.

|

|

Other Exemptions:

|

|

Schools sponsored and operating for a business, professional, or fraternal organization.

|

|

Federal– or state–operated institutions.

|

|

Purely avocational or recreational schools.

|

|

Religious schools not offering secular degrees.

|

|

Flight instruction schools that do not require prepayment in excess of $2,500.

|

|

Schools charging less than $2,500 for educational programs and not offering degrees.

|

|

Schools offering test or license examination preparation.

|

As a Result, Not All Schools Overseen by Bureau. As noted, an institution’s accreditation status determines the level of state oversight it receives. Regionally accredited schools are entirely exempt from Bureau oversight. Nationally accredited schools, while still subject to all Bureau requirements, are exempted from educational program reviews as part of the licensing process (but must demonstrate compliance with educational standards as well as all other minimum operating standards during periodic inspections). Unaccredited schools are subject to full Bureau oversight through licensing and compliance requirements.

No State Oversight of Online Schools. While some California colleges are exempted from Bureau oversight due to accreditation, another group of colleges—online colleges based in other states—is not subject to state oversight. The Private Postsecondary Act does not apply to these schools. As a result, they are not required to show the Bureau evidence of accreditation or approval by another state in order to serve California students. Oversight of these online colleges is discussed in a box later in this report.

Comparing Oversight of Bureau and Accreditors

The Private Postsecondary Act directs our office to examine the extent to which regional and national accrediting agencies provide the same level of student protection as that provided by the Bureau. Below, we compare the protection offered under the two systems. We find that accreditor oversight differs from Bureau oversight in several ways. The organizations have different structures, areas of focus, and review processes.

Different Structures and Authority

Bureau Provides Independent Oversight, Accreditation Is a Form of Self–Policing. The Bureau is an executive branch agency managed by civil servants who are independent of the postsecondary schools they oversee. It has an administrative hierarchy for decision–making at various levels, and decisions are guided by statutes and detailed regulations developed to protect public interests. Nearly all accreditors, by contrast, are voluntary, nongovernmental membership associations governed by the institutions (members) they accredit. They have a shared interest in holding members to certain standards because the reputation of each member institution is linked to the reputation of the group. They also have an interest in forestalling additional federal and state regulatory efforts by requiring their members to meet sufficiently high self–imposed standards. Accrediting associations delegate significant decision–making to peer reviewers from institutions within the association. Notably, accreditors’ funding derives largely from dues and accreditation fees paid by member institutions. The Bureau’s budget is similarly funded by fees from regulated schools, but Bureau–regulated schools do not have a choice of regulators, while schools sometimes have a choice of accrediting bodies.

Bureau Has Greater Enforcement Authority. Deriving from its statutory authorization, the Bureau has a number of enforcement powers it can bring to bear against institutions that are out of compliance with its requirements. The Bureau (sometimes in collaboration with the AG) can deny a school approval to open, put a school on probationary status, or require a school to stop offering a particular program or operating as a postsecondary institution. It can require a school to stop advertising and recruiting students, or prohibit a school owner from operating any schools for a specified period. The Bureau also can issue citations for a school’s violations of state law or regulations, assess a fine up to $50,000, require a refund to a student, or require other restitution.

Accreditors Have Fewer Formal Sanctions at Their Disposal. By contrast, accreditors have few sanctions available to them for minor violations. They may require institutions to submit corrective action plans and interim reports, as well as schedule additional site visits to monitor compliance. In the event of a more serious violation, an accreditor will typically give an institution a fixed amount of time to correct problems to avoid suspension or revocation of its accreditation. In practice, accreditors—especially the regional associations—rarely terminate the accreditation of their member institutions. (Recent actions by regional accreditors suggest this may be changing in response to increased federal scrutiny of accreditors. For example, in 2012 the WASC Senior College and University Commission initially denied accreditation to Ashford University, requiring extensive changes in practice before ultimately granting accreditation. Additionally, in 2013 the WASC Accrediting Commission for Community and Junior Colleges terminated accreditation for City College of San Francisco, effective July 2014.)

Different Areas of Focus

Accreditors Focus on Educational Quality. Regional and national accreditors focus primarily on program quality and student outcomes. For example, most accreditors require evidence of student learning as part of their review process, while the Bureau simply requires that institutions describe desired student learning outcomes. Accreditors typically require that teaching faculty possess an academic degree above the level of instruction, often specifying a master’s degree or higher, while the Bureau permits faculty at the same level of preparation as the course being taught. As well, accreditors have standards for faculty development and student support services such as academic advising, while the Bureau does not.

Bureau Emphasizes Protecting Students From Fraud. Consistent with its placement in DCA, the Bureau focuses more heavily on student protection from fraud and deceptive practices than on educational quality. One article in the Private Postsecondary Act pertains to operating standards (which address educational program content, faculty qualifications, and other aspects of educational quality), while the bulk of the legislation is dedicated to fair business practices, recordkeeping, recruitment, disclosures, refunds, and other consumer protection issues. In addition, the Bureau’s standards for student protection are generally more exacting than those of accreditors. For example, the Bureau specifies the format and content of written enrollment agreements that institutions must provide to each student detailing total charges, cancellation and refund policies, complaint procedures, and other required information. Regional accreditors do not require these agreements, and national accreditation standards lack the specificity—and some of the substantive requirements—of the Bureau’s standards.

Bureau Resolves Individual Student Complaints, Accreditors Focus on Complaint Process. One of the Bureau’s major responsibilities is responding to individual student complaints. The Bureau is required to determine the facts surrounding a complaint, conduct an investigation if needed, and take appropriate administrative enforcement action, including ordering the institution to provide restitution to any students who experienced damage or loss due to a school’s violation of the law. In contrast, most accreditors do not seek to resolve individual student complaints regarding the postsecondary schools they accredit. Instead, they require that institutions have appropriate complaint resolution processes in place and follow them. They also consider patterns of complaints that may reflect underlying issues regarding the institution’s compliance with the association’s standards.

Bureau and National Accreditors Enforce Specific Regulatory Standards, Regional Accreditors Use Continuous Improvement Approach. The Bureau focuses on ensuring that institutions meet objective standards that are clearly spelled out in legislation and regulations. These standards typically involve processes (such as disclosure) rather than outcomes. The approach is binary in most cases, and lends itself to checklists—an institution either meets or does not meet a particular standard. National accreditors also evaluate schools against minimal thresholds of compliance, but they are more likely than the Bureau to have specific, quantifiable benchmarks of minimally acceptable student outcomes. Regional accreditors, on the other hand, employ a continuous improvement approach. Although they have some explicit criteria institutions must meet, they typically look for areas in which institutions can improve their performance and evaluate progress in those areas. They tend to have guidelines instead of specific requirements in their standards and often evaluate progress qualitatively.

Program completion, job placement, and graduate earnings provide a good illustration of these different approaches. The Bureau requires institutions to disclose these data for each program using specified definitions and time frames, but it sets no minimum performance levels. In addition to requiring public disclosure of this information, the major national accreditors often set minimum acceptable levels of performance (for example, establishing minimum job placement rates) and take disciplinary action (up to and including withdrawing accreditation) when institutions fall below their benchmarks. Regional accreditors require institutions to monitor and publish graduation rates (but typically not job placement and earnings), benchmark them against the rates of peer institutions, and develop goals and plans for improvement if rates are poor. Unlike national accreditors, however, regional associations typically do not set minimum thresholds for these measures.

Bureau and Accreditor Standards in Remaining Areas Are Similar. Despite these differences, Bureau and accreditor standards overlap more significantly in several areas. These include many general operating standards. For example, both the Bureau and accreditors require schools to retain certain student records permanently, submit independently prepared or audited financial statements, and maintain financial viability as reflected by their assets–to–liabilities ratio.

Different Review Processes

Accreditor Reviews Are More Thorough. Reflecting their different objectives, the Bureau and accreditors differ in how they structure institutional reviews. The Bureau uses a relatively short, staff–driven process based on protocols and checklists. Regional accreditors (and to a lesser extent, national accreditors) rely on a far more extensive process using a team of peer reviewers (including faculty members, administrators, and other college staff) to determine institutional compliance with standards. The Bureau process for approval to operate—which involves an application, Bureau review of documents, and a determination—can be completed in a matter of months. At the Bureau’s discretion, it may assemble a visiting team to conduct an onsite review as part of the initial approval process, but this is not required. By contrast, one to three team visits are always central to the regional accreditation process, which may require several years to complete.

Bureau Conducts More Frequent Reviews. Institutions must renew their Bureau approval every five years and provide annual reports to the Bureau. In addition, statute requires the Bureau to conduct one announced and one unannounced compliance inspection at every institution at least every two years. (The new Bureau has not yet met these requirements.) Regional associations typically grant accreditation for five to seven years initially and ten years thereafter. National accreditors fall in between, requiring more frequent visits and reports than regional associations but less frequent than the Bureau.

Assessing Existing Oversight Structure

Our comparison of the oversight provided by accrediting agencies and the Bureau shows that these entities have different strengths and weaknesses. Accrediting agencies provide better educational oversight than the Bureau. In addition, these agencies require institutions to meet general operating requirements that typically are at least as rigorous as the Bureau’s requirements. In the areas of business practices and student complaints, however, accreditor oversight (both regional and national) falls short of Bureau oversight.

Oversight of Accrediting Agencies Sufficient in Two Areas

Accreditors Provide Greater Oversight of Educational Program Quality. With stricter educational program standards and more in–depth reviews by knowledgeable experts, regional and national accreditors generally provide greater scrutiny of institutions’ educational program quality than the Bureau. Moreover, accreditors and the Bureau both examine student learning outcomes, require monitoring and reporting of student graduation rates and certain other outcomes, and set minimum faculty qualifications. Given these factors, Bureau oversight activities related to educational program quality do not add significant value at nationally accredited institutions and likewise would not add value at the currently exempted regionally accredited institutions.

Accreditors Provide Similar Oversight of General Operations. Accreditors and the Bureau have similar practices in areas other than educational quality and business practices. Similarities exist particularly in general operating standards, such as those for record–keeping, facilities, and financial viability. Given these similarities, the Bureau could eliminate its oversight process in these areas for many of the institutions it reviews without adverse effect.

Oversight of Bureau Better in Two Areas

Bureau Provides Better Review of Business Practices. In the area of business practices, however, the Bureau has more exacting standards than both regional and national accreditors. In general, the business practices of regionally accredited institutions are the least well monitored given these institutions are exempt from Bureau oversight and regional accreditors focus more heavily on educational rather than business practices. Though national accreditors place more focus than regional accreditors on business practices, the standards they apply generally also are more lenient than the Bureau’s.

Bureau Provides Better Recourse for Student Complaints. Similarly, because most accreditors do not seek to resolve individual student complaints, students attending accredited, exempt institutions do not have comparable recourse for their complaints as students attending schools overseen by the Bureau.

Recent Changes Have Motivated Colleges to Improve in These Areas . . . In 2010 and 2011, USED published new rules to tighten standards for institutions participating in federal student aid programs with the intent of improving business practices generally. These rules prohibit incentive–based payments for recruiting, admitting, or awarding financial aid to students. The new rules also strengthen disclosure and performance standards for certain vocationally oriented programs. New disclosure requirements include graduation and job placement rates, total program costs, and median loan debt for graduates. Additional rules under development will establish maximum student debt levels relative to average graduate earnings for certain programs. These developments, along with tighter student loan default limits approved in 2008, provide incentives for all accredited schools participating in federal aid programs to improve their business practices and student outcomes. Several accreditors also have stepped up their own standards and enforcement—forcing schools with poor compliance to either improve or close.

. . .But Complaints Persist. A multistate task force of state AGs that monitors for–profit colleges reported in October 2013 that, despite these recent changes, complaints from students and alumni of for–profit colleges continue. Ten states, including California, currently have investigations pending against regionally and nationally accredited for–profit education companies.

State Oversight Required to Meet New Federal Rule. Irrespective of the relative strengths and weaknesses of accreditor and Bureau oversight, the new federal state authorization rule requires that institutions participating in federal student aid programs be authorized by the state in which they are located by July 1, 2014 and have a state complaint–resolution process in place. This requirement has created a challenge for some currently exempt colleges. While some of them have approval from state agencies other than the Bureau (such as Student Aid Commission approval to participate in Cal Grant programs), they do not have a state complaint–resolution process. Other exempt schools have neither state approval nor a state complaint–resolution process. Colleges failing to meet this new requirement could lose access to federal student aid programs on which they depend.

Recommendations

In this section, we make several recommendations. Specifically, we recommend eliminating Bureau oversight in the areas of educational quality and general operating practices for accredited colleges but requiring business practices review of some accredited colleges. We believe these changes would have the net effect of freeing up Bureau resources to focus on unaccredited institutions and a limited number of accredited institutions that require additional attention. In addition to modifying exemptions, we recommend the Legislature allow exempt institutions to receive limited Bureau review focused on business practices and student complaints to help them meet new federal requirements. We also recommend extending Bureau oversight to certain online colleges. Figure 5 summarizes our assessment and recommendations.

Oversight of Online Colleges

Some Online Colleges Serving California Students Not Regulated by Bureau. Because the Bureau regulates only schools with a physical presence in the state, California students enrolled in online programs offered by institutions based in other states do not benefit from the oversight provided by the Private Postsecondary Act. For example, these schools are not subject to the Bureau’s minimum standards for educational quality, general operations, or business practices, and their students do not have access to the Bureau’s complaint–resolution process. These institutions may be accredited or unaccredited and may be licensed by another state, but they currently are not required to show evidence of such approvals to offer courses to California students.

Federal Rule Likely to Require Bureau Oversight for These Schools. A recent federal rule would have required colleges providing distance education to be approved by each state in which they enroll students, but this rule was overturned on a technicality. Nonetheless, many states have proceeded to review and improve their oversight processes for out–of–state schools—both because policymakers believe regulating these schools is important and because the United States Department of Education plans to resubmit the regulation in 2014. If the rule is reinstated, the Bureau’s workload could increase substantially as many out–of–state schools seek state approval.

Rule Also Would Affect California Schools Offering Online Programs. In addition to requiring out–of–state schools enrolling California students to receive Bureau approval, the new rule would require California schools enrolling students in other states to be authorized by each of those states. Such state–by–state approval can be a barrier for institutions offering distance education because of the considerable complexity and cost of navigating differing requirements in multiple states.

States Forming Reciprocity Consortium. To address this challenge, a group of institutions, states, and policy organizations is developing the State Authorization Reciprocity Agreement (SARA) whereby accredited, degree–granting institutions approved by an oversight body in one participating state will be deemed automatically to have met approval requirements in other participating states. This agreement will facilitate multistate approval for institutions while providing each state assurance that participating colleges meet common standards and have meaningful accountability and complaint–resolution procedures in place.

Require State Approval for Out–of–State Schools Enrolling California Students. Extending Bureau oversight to out–of–state distance education providers enrolling California students would provide greater student protection for California students. To this end, we recommend the Legislature require online colleges serving California students to be approved by the Bureau.

Authorize Bureau to Participate in SARA. Through SARA, the Bureau could oversee online schools enrolling California students with minimal additional workload by recognizing approval from other participating states that meet mutually agreed–upon standards. We recommend the Legislature provide statutory authorization for the Bureau to participate in SARA and to grant reciprocal approval to institutions licensed in other states. In addition to facilitating better protection for California students, this would enable colleges overseen by the Bureau (including those volunteering for business practices review) to receive multistate authorization through an efficient process.

Figure 5

Summary of Assessment and Recommendations

|

Assessment:

|

Recommendations:

|

|

Educational Quality and General Operations

|

|

Regional and national accreditors provide more rigorous educational quality review than Bureau and have similar general operating standards.

|

- Continue to exempt regionally accredited schools from these components of Bureau review.

- Eliminate these components of Bureau review and inspections for nationally accredited schools.

|

|

Business Practices and Student Complaints

|

Regional and national accreditors provide less rigorous oversight of business practices than Bureau.

|

- Continue to exempt low–risk regionally accredited schools from Bureau’s business practices review. Subject only higher–risk regionally accredited schools to business practices review.

- Continue to conduct business practices review for all nationally accredited schools but reduce Bureau’s periodic inspections of low–risk nationally accredited schools in good standing.

- Focus freed–up Bureau resources on oversight of unaccredited schools and accredited schools with identified problems.

|

|

Accreditors do not provide comparable recourse as Bureau for resolving student complaints.

|

- Include oversight of complaint resolution in Bureau’s business practices review.

|

|

To be able to participate in federal financial aid programs, institutions are now required to (1) obtain state approval to operate and (2) have a state–run complaint–resolution process.

|

- As an option to meet new federal requirements, allow exempted schools volunteering for Bureau oversight to receive limited review focused on business practices and student complaints.

|

|

Oversight of Online Colleges

|

|

State does not oversee institutions that have no physical presence in California but that are enrolling California students through distance learning.

|

- Require online colleges serving California students to receive state approval to operate.

- Authorize Bureau to participate in new State Authorization Reciprocity Agreement and to grant reciprocal approval to schools authorized in other participating states.

|

Rely on Accreditors to Oversee Educational Quality and General Operations

Rely Solely on Accreditors for Educational Program Review. Given accreditors generally conduct more extensive education program reviews, we recommend the Legislature continue to exempt regionally accredited institutions from the Bureau’s education program reviews. For nationally accredited schools, we recommend eliminating the education–review components of the Bureau’s on–site inspections. As a result of eliminating these components of its reviews, the Bureau would not duplicate any of the education program review efforts of accreditors. Accreditors would be solely responsible for continuing to oversee certain minimum operating standards related to educational program quality.

Reduce Duplication in Reviews of General Operations. Likewise, we recommend the Legislature continue to exempt regionally accredited institutions from the Bureau’s reviews of general operations. In addition, we recommend the Legislature direct the Bureau to identify duplication between its operating standards and those of national accreditors and eliminate Bureau reviews of the overlapping areas.

Target Bureau’s Business Practices Review to Select Schools

Continue to Exempt Most Regionally Accredited Institutions From All Bureau Reviews. In general, we see no compelling reason for the Bureau to oversee most regionally accredited institutions. Although regional accreditors generally do not provide as rigorous oversight of business practices as the Bureau, most regionally accredited schools appear to have acceptable business practices.

Subject a Small Subset of Regionally Accredited Institutions to Business Practices Review and Complaint–Resolution Process. We do have a concern, however, about a small number of regionally accredited institutions. We recommend the Legislature bring this small subset of institutions under Bureau oversight but limit the scope of review to business practices and complaint resolution. Specifically, we recommend the Legislature establish criteria to distinguish low–risk from higher–risk institutions and subject only higher–risk institutions to oversight in these particular areas. To determine which regionally accredited institutions should be subject to Bureau review of business practices and complaint resolution, the state could consider various institutional proxies for risk, including:

- School ownership (nonprofit or for–profit).

- Types of programs offered (degree or nondegree programs, length of programs, and vocational orientation).

- Track record (such as operating in state for a minimum of 20 years in good standing and accreditation experience, including history of complaints and adverse findings).

- Performance criteria (including graduation and student loan default rates).

Match Bureau Reviews of Nationally Accredited Schools to Risk Level. Consistent with current state law, we recommend the Legislature maintain Bureau review of business practices and complaint resolution for nationally accredited institutions. However, the state could make a similar determination of low– and high–risk institutions to determine the extent of Bureau oversight. For example, the state could reduce the periodic inspection requirement for low–risk nationally accredited institutions that are approved based upon initial business practices review and remain in good standing. Schools could report certain data and if problems emerged through reporting or complaints, then the Bureau could reinstate frequent reviews and inspections until the school had several consecutive years without incidence. Higher–risk nationally accredited institutions could remain subject to ongoing business practices review and periodic announced and unannounced Bureau inspections.

Focus Bureau Resources on Overseeing Highest–Risk Institutions. Under our recommendations, the Bureau would be increasing its workload for a small set of regionally accredited institutions, but it would be reducing its workload for a larger set of nationally accredited institutions that would require only the more limited review focusing on business practices and complaints rather than extensive Bureau oversight that included reviews of educational quality and general operations as well as regular compliance inspections. The net effect of these oversight changes would be to free up time for the Bureau to focus on the highest–risk institutions (including unaccredited schools)—providing these schools more extensive and more frequent oversight. In short, under the revised oversight system, the Bureau generally would conduct inspections for low–risk accredited institutions only when triggered by complaints, poor performance, or other factors, while dedicating the bulk of its compliance resources to the remaining, highest–risk accredited and unaccredited institutions.

Colleges Voluntarily Opting for Bureau Review Would Benefit From Targeted Approach. Exempt institutions already have the option to submit to Bureau oversight voluntarily, pursuant to Chapter 28, Statutes of 2013 (SB 71, Committee on Budget and Fiscal Review). Two large for–profit college groups have done so—the University of Phoenix and DeVry University—to meet the new federal financial aid requirement that they be authorized by a state agency and have a state complaint resolution process in place. Under current law, these institutions are subject to the full range of Bureau requirements, resulting in substantial cost and effort, some of which duplicates existing accreditation requirements. Limiting such review to business practices could reduce this regulatory burden, making this option more attractive for colleges.

Conclusion

The Legislature reestablished oversight of private postsecondary schools by enacting the Private Postsecondary Act in 2009. A primary goal of the act is to provide meaningful student protections and an appropriate level of oversight for private colleges. The act called for our office to undertake a review of newly authorized exemptions from Bureau oversight. Based on our review of these exemptions, we believe that for the most part, current exemptions are consistent with the Legislature’s goals for the act. In a few areas, however, we identified ways the Legislature could adjust the exemptions to reduce duplication between Bureau and accreditor oversight and improve student protections. Taken together, we believe the recommended changes would improve student protections, promote an appropriate level of oversight for various types of colleges, target the Bureau’s limited resources to overseeing the highest–risk schools, and help a number of accredited colleges meet new federal requirements.