Introduction

A partnership between the state and the private sector is

sometimes used to finance, design, construct, operate, and maintain

state infrastructure projects (such as highways, mass transportation

systems, and state buildings). Such a P3 requires the state and the

private sector to collaborate when making decisions about a project.

By bringing external resources and specialized expertise to a

project, the state is expected to achieve certain benefits from a P3

that typically are not achievable when using a more traditional,

public sector procurement approach.

In recent years, California has entered into P3s with private

partners for two state infrastructure projects. Specifically, to

build and operate the Presidio Parkway transportation project in San

Francisco (also known as Doyle Drive) and to build and maintain a

new courthouse in Long Beach. Each of these agreements is for a

period of about 30 years. The combined estimated cost to the state

for both of these projects is about $3.4 billion. Given their

significant cost and the limited experience the state has had in

such partnerships, we identify in this report best practices for the

state to follow when using P3s and present recommendations for

maximizing the benefits to the state. In preparing this report, we

met with representatives from various state departments about their

experiences with P3s, as well as numerous P3 experts. We also

reviewed the literature regarding best practices for implementing

such partnerships.

Background

State Procures Infrastructure Projects in Various Ways

State law specifies the processes for reviewing and approving

proposed state infrastructure projects. In most instances, such as

for court facilities and state office buildings, the Legislature

must approve and appropriate funds for a state project. (They also

must receive approval from the State Public Works Board at various

subsequent stages.) However, the California Transportation

Commission (CTC) approves most state projects related to

transportation. The review and approval process for state projects

generally involves determining (1) the need for the project, (2) how

the project fits into existing infrastructure systems, (3) the

project's priority relative to other state infrastructure projects,

and (4) how the project will be funded. This process typically

consists of multiple reviews and approvals as a project's

development moves from concept to environmental review and

preliminary engineering, and then to design and construction.

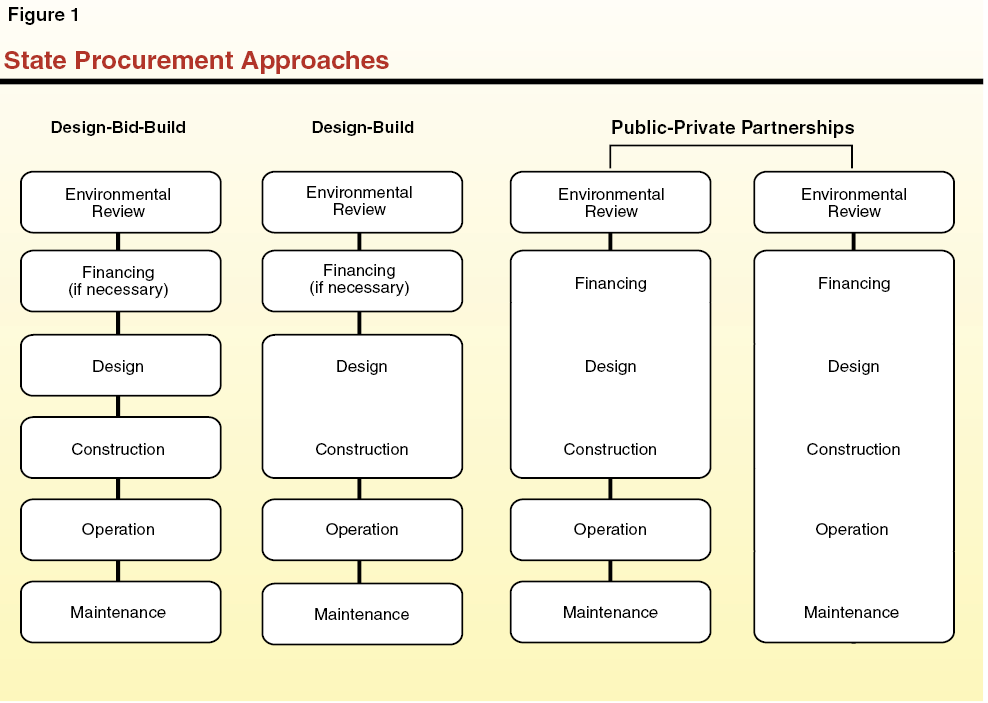

State law specifies three general types of procurement

approaches—design–bid–build, design–build, and P3—that state

departments can use to deliver infrastructure projects that have

been approved for construction. As summarized in Figure 1, each of

these procurement approaches involves varying ways of contracting

with the private sector for a project. We discuss each approach

in more detail below.

Design–bid–build. State departments can

use a design–bid–build approach to procure all types and sizes of

infrastructure. Under this approach, the work for each stage of a

project is performed separately. For example, a state department

will generally first award an architectural/engineering contract to

design the project based on subjective criteria of qualifications

and experience of the architect/engineer. In some cases, however,

state staff may design the project. After detailed project plans and

drawings are completed, the department then selects a contractor to

perform the construction work. Construction contracts are awarded

objectively based on competitive bidding, with the contract going to

the qualified bidder who submits the lowest price. Once construction

is completed, the state department is responsible for operating and

maintaining the facility. The state pays for the cost of

design–bid–build projects either up front with state funds or over

time by selling general obligation bonds or lease–revenue bonds.

Design–build. Under existing state law,

certain departments can use design–build procurement. With

design–build, the department typically contracts with a private

general contractor to both design and build the infrastructure

project. The department does not separately contract with an

architect/engineer for design. Rather, the general contractor is

responsible for subcontracting with other entities for design and

various construction work. The state awards a design–build contract

through a competitive bidding process that evaluates factors such as

price, design features, construction schedule, and community or

environmental outcomes. Under design–build, the state maintains

responsibility for financing, operating, and maintaining the

project.

Alternatively, another type of design–build involves the state

transferring design and construction risks to a specialized

construction manager, rather than a general contractor. This

approach is commonly referred to as "construction manager at risk

procurement." With construction manager at risk, the state awards a

contract based on a fee. The construction manager designs the

project and solicits bids from subcontractors and suppliers. The sum

of these bids, along with a surcharge, determines the total price

the state pays for the project.

P3s. Current state law authorizes three

state departments—Caltrans, AOC, and the High–Speed Rail Authority

(HSRA)—to use some form of a P3. While there can be varying degrees

of P3s, the type of P3 often discussed and most recently used in

California is when a single contract is entered into with a private

partner (often a consortium of several companies) for the design,

construction, finance, operation, and maintenance of an

infrastructure facility. For the purpose of this report, we

generally define a P3 as the contracting with the private sector to

design–build–finance–operate–maintain an infrastructure project. (As

we discuss in the nearby box, the state can also enter into

partnerships with other public entities, such as counties, for the

procurement of state infrastructure.)

State Partnerships with Other Public Entities

In addition to the private sector, the state can utilize

other public entities (such as a county or other public

authorities) for the design, construction, operation, and

maintenance of an infrastructure project. In such cases,

however, these entities typically subcontract (either through a

single contract or multiple contracts) with the private sector

to perform much of the actual work on a project. For example,

the public partner could finance a project with municipal

financing, contract with a private company for design and

construction work, and have separate contracts with other

companies to maintain and operate the infrastructure facility.

An example of a public–public partnership project is "The

Toll Roads" in Southern California—a 50 mile network of tolled

state highways in southern Orange County built by the

Transportation Corridor Agencies (TCAs), which are led by

locally elected officials. In 1987, the Legislature authorized

the TCAs to design, construct, finance, operate, and maintain a

portion of the state's highways and to fund the cost of the

project with tolls. The TCAs contracted with private companies

to perform most of the work on the project.

Under a P3 approach, the state can transfer a significant amount

of responsibility associated with a project to the private sector.

For example, the private partner will generally make design and

construction decisions and be responsible for paying the costs to

resolve any construction issues in order to ensure that the project

is completed on time. In addition, the partner will often be

required to finance the project, which generally includes the costs

of design and construction staff, materials, and construction

equipment. However, in order for a private partner to be willing to

finance these costs, the contract must specify a mechanism for

repaying the partner. In many cases, this involves a revenue source

created by the project (such as a toll or user fee on the

infrastructure facility), with the private partner taking on the

risk that the projected revenues will materialize at the level

anticipated. Alternatively, the state can commit to making annual

payments to the partner from an identified funding source, such as

tax revenues. Since it can take many years for a revenue source

(such as a toll on a road) to pay off the private financings, the

terms of P3 contracts generally range between 25 years to 100 years.

The P3 procurement approach is typically more complex than

design–bid–build and design–build. For instance, under a P3

approach, the state must first evaluate a pool of potential bidders

to determine if they have the qualifications necessary to design,

build, finance, operate, and maintain the infrastructure facility.

Then, qualified bidders submit proposals that the state evaluates in

order to select a preferred bidder. A P3 contract is often awarded

to the bidder deemed to provide the best value.

Three State Departments Authorized to Use P3s for

Certain Projects

As shown in Figure 2, existing state law authorizes the use of

P3s for certain transportation and court construction projects.

(State law also authorizes certain local governments to use P3s for

local infrastructure projects.) Below, we discuss in more detail the

specific P3 authority provided to state departments.

Figure 2

Summary of State Public–Private

Partnership (P3) Authority

|

State Department

|

Type of

Infrastructure

|

State

Law

|

Brief

Description

|

Projects To Date

|

|

Caltrans

|

Highways

|

Chapter 107, Statutes of

1989 (AB 680, Baker)

|

Allowed Caltrans to enter

into up to four P3s.

|

State Route (SR) 91 and SR

125

|

|

Caltrans and regional

transportation agencies

|

Highways, local roads, and

transit

|

Chapter 2, Statutes of 2009

(SB 2X 4, Cogdill)a

|

Allows Caltrans and regional

agencies to enter into an unlimited number of P3s

through 2016.

|

Presidio Parkway

|

|

High–Speed Rail Authority

(HSRA)

|

High–Speed rail

|

Chapter 796, Statutes of

1996 (SB 1420, Kopp)

|

Allows HSRA to enter into P3

contracts for the proposed rail system.

|

High–Speed train system

|

|

Administrative Office of the

Courts (AOC)

|

Court facilities

|

Chapter 176, Statutes of

2007 (SB 82, Committee on Budget and Fiscal Review)

|

Establishes process for

review of AOC P3 projects.

|

Long Beach Courthouse

|

Caltrans. Chapter 107, Statutes of 1989

(AB 680, Baker), authorized Caltrans to enter into P3 agreements for

up to four projects. Under this authorization, as well as that

provided in related follow–up legislation, Caltrans built ten miles

of tolled express lanes in the median of the existing State Route

(SR) 91 in Orange County. In addition, the department built SR 125

in San Diego County that connects the area near the Otay Mesa border

crossing with the state highway system. For each project, Caltrans

used a single contract with a private partner to design, construct,

finance, operate, and maintain the facility. (We discuss these two

projects in more detail later in this report.)

In 2009, Caltrans' authority to enter into P3 agreements was

expanded. Specifically, Chapter 2, Statutes of 2009 (SB 2X 4,

Cogdill), authorizes Caltrans and regional transportation agencies

(such as the Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation

Authority) to enter into an unlimited number of P3 agreements for a

broad range of highway, road, and transit projects through December

31, 2016. However, the legislation specifies that such P3 projects

must achieve one or more objectives as determined by the CTC, which

is responsible for programming and allocating funds for the

construction of highway, rail, and transit improvements. These

objectives include:

-

Improve travel times or reduce vehicle hours

of delay.

-

Improve transportation operation or safety.

-

Provide quantifiable air quality benefits.

-

Meet a forecasted demand of transportation.

In addition, the above agreements are subject to a 60–day review

by the Legislature and PIAC before Caltrans can sign them. The PIAC

is an advisory commission created by Chapter 2 and chaired by the

Secretary of the Business, Transportation, and Housing (BT&H)

Agency. Specifically, PIAC is charged with assembling research, best

practices, and lessons learned from transportation P3s around the

world. The commission can, upon request, assist Caltrans and

regional transportation agencies with P3 project selection,

evaluation, procurement, and implementation. Currently, PIAC

consists of about 20 volunteer members and is staffed within

existing BT&H Agency resources.

In January 2011, Caltrans entered into its first P3 under Chapter

2 for the Presidio Parkway project. This particular P3 requires the

private partner to complete the second phase of the design and

reconstruction of the southern approach to the Golden Gate Bridge

and to operate and maintain the roadway for 30 years. In exchange,

the state will make payments estimated to total roughly $1.1 billion

to the private partner over the life of the contract.

Judicial Council and AOC. Under current

law, the judicial branch is authorized to use P3s. In addition,

state law requires the Judicial Council (the policy making body for

the judicial branch) and their staff in the AOC to develop

performance standards to facilitate the review of P3s and requires

the Department of Finance (DOF) to review projects that include a P3

component. The legislation also specifies that AOC may only proceed

with a P3 if the Legislature does not object to the performance

standards adopted for the project.

The 2007–08 Budget Act directed AOC to gather

information regarding the possible use of a P3 for the replacement

of the Long Beach courthouse. In December 2010, AOC entered into a

P3 that requires a private developer to finance, design, build,

operate, and maintain the Long Beach courthouse over a 35–year

period in exchange for payments from the state totaling $2.3

billion. At this time, the Long Beach courthouse is the only project

that the AOC has procured using a P3.

The HSRA. Chapter 796, Statutes of 1996

(SB 1420, Kopp), created the HSRA and authorized it to use P3

procurement for the development of a High–Speed train system

connecting northern and southern California. However, state law does

not establish a specific process for reviewing or approving P3s for

HSRA. State law requires capital expenditures by HSRA to be approved

by the Legislature. Based on the authority's 2012 business plan, the

HSRA would not award its first P3 contract until 2023.

Benefits and Limitations of P3s

Government entities typically use P3s to achieve benefits that

they may not be able to obtain under a more traditional procurement

approach (such as design–bid–build). However, P3s can also introduce

new limitations and costs as summarized in Figure 3 and described in

detail below.

Potential P3 Benefits

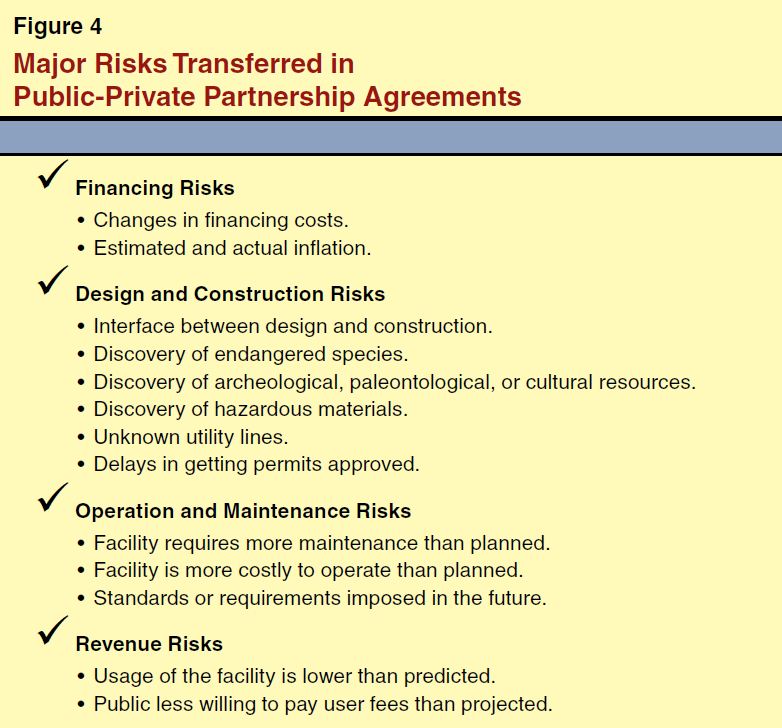

Transfers Project Risks to Private Partner.

The P3s can transfer risks associated with a project from a

government entity to a private partner. Figure 4 summarizes the

major risks that could potentially be transferred, such as those

related to financing, operation, and maintenance. As indicated in

the figure, the most significant risks are associated with the

design and construction of a project. For example, under a P3

approach, the private developer would bear the risks and costs if

the design of the project were changed to fit certain site

conditions (such as soil quality or the discovery of archeological

artifacts). Similarly, the private partner would be responsible for

project cost overruns, which can be very expensive. The transfer of

this risk could reduce or eliminate the need for additional public

funds to complete a project. Moreover, the partner would bear the

risk if the actual revenue collected from any tolls or user fees are

less than projected, which depending on the project, can be

significant. In order to ensure adequate compensation, private

developers attempt to estimate the anticipated costs of resolving

issues on the risks they assume and factor these costs into their

bid. However, in some cases, the developer may be better equipped to

manage certain risks at a lower cost than if the government retained

all of the project risks.

Greater Price and Schedule Certainty.

Based on a survey conducted by the Federal Highway Administration

(FHWA), governments around the world reported that P3s can provide

better price and schedule certainty for the design and construction

of a project compared to a more traditional procurement approach

(such as design–bid–build). In part, this is because P3s allow a

government entity to share certain risks with a private developer

who has more experience with a particular type of project and has

developed strategies to mitigate potential cost increases that could

result from such risks. The government can also achieve greater

price certainty from P3s because, as is the case with design–build

and construction manager at risk contracts, the contacts often have

a maximum price. This means that the private partner must pay for

any cost increases above the agreed upon price. In addition, the

government typically sets up a streamlined process to review the

design and construction decisions made by the partner, which can

help prevent delays in the project schedule. Moreover, P3s that

include financing can incentivize the partner to complete the

project on time and receive the necessary funding (such as payments

from the government or revenues from project user fees) to repay the

private loans taken out to finance the project.

More Innovative Design and Construction Techniques.

Experts in P3s generally believe that the private sector is often

better able to develop innovative project designs and construction

techniques than government entities. In part, this may be due to the

specialized expertise that a private partner can bring to a project.

Greater design and construction innovation could result in a variety

of potential benefits, including lower project costs, a higher

quality project, shorter construction schedules, and enhanced

project features.

"Free Up" Public Funds for Other Purposes.

In general, using a private developer's access to capital can free

up government funds to advance the construction of other

infrastructure in the near–term and, thus, provide the public with

access to improved infrastructure sooner than planned. In addition,

the developer's financing can sometimes provide more advantageous

repayment terms than a government might typically obtain under a

more traditional public financing approach. For example, if

repayment were extended over a longer period of time than the

government typically has to repay borrowed funds, it could reduce

the amount that must be repaid each year. Such freed–up public funds

could then be allocated for other purposes.

Quicker Access to Financing for Projects.

In addition, by making a private developer responsible for financing

a particular project, a government might be able to access financing

in cases where it does not yet have the authority to borrow. For

example, California's constitution requires voter approval prior to

selling certain types of bonds to finance infrastructure projects,

which could delay the state from accessing financing for certain

projects. However, projects financed through a P3 would not require

voter approval, potentially allowing some projects to start

construction sooner.

Higher Level of Maintenance. Due to

insufficient funding for maintenance, as well as how existing

maintenance funding is prioritized, some governments currently do a

poor job in maintaining their infrastructure. For example, due to a

lack of regular maintenance, only 28 percent of California's

highways are in good condition. As a result, many highways require

costly major rehabilitation or replacement. Under a P3 approach, a

government could require the private partner to maintain the

constructed infrastructure to specified standards. Essentially, this

means that P3 facilities could remain in good condition over longer

periods of time, thus allowing the government to delay the cost of

major rehabilitation or replacement.

Keeps Project Debts Off the Government's "Books."

Another benefit of P3 financing is that the debt incurred by a

private partner for a project may not be counted as government debt.

In other words, P3 financing may not appear as debt on government

balance sheets. According to recent studies by the FHWA and the

United Nations Economic Commission for Europe, this is one of the

reasons why some countries in the European Union have chosen to use

P3s. While the benefit of debt not appearing on the government's

balance sheet is probably more important to governments subject to

strict limitations on debt, it could also improve the overall

ability of some governments to borrow funds for other purposes.

However, since California does not have such strict debt limitations

that restrict its options for financing infrastructure projects this

benefit does not currently apply to the state.

Potential P3 Limitations

Increased Financing Costs. Financing a

project through a P3 is likely to be more expensive than the

financing options typically used under the more traditional

procurement approaches (such as obtaining state and federal loans).

This is because private companies typically pay higher interest

rates than government entities to borrow money. For example, a study

of P3 projects in Canada found that private partners typically pay 1

percentage point higher on loans compared to the governmental cost

of borrowing. In times of limited access to financial markets (such

as the financial crisis of 2008), the cost difference between

private and public borrowing was 2 percentage to 3 percentage

points. In addition, private companies will often seek to earn a

profit of roughly 10 percent to 25 percent when loaning funds to a

government, which can further increase P3 financing costs.

Greater Possibility for Unforeseen Challenges.

As previously discussed, in comparison to design–bid–build and

design–build contracts, P3 contracts cover a much longer time period

and scope of activities (such as maintenance of the infrastructure

facility). Thus, there is a greater possibility for unforeseen

issues to arise under a P3 approach. Such issues could include

disputes regarding certain terms in the contract, as well as the

private partner being acquired by another company or going out of

business, effectively resulting in project schedule delays and

additional costs to the government.

Limits government's Flexibility. The

long–term nature of P3s can also "lock in" certain government

funding priorities based on operational needs determined at the time

the contract is negotiated. This can make it difficult to change

funding allocations to reflect changes in government priorities. For

example, a P3 contract may require litter and graffiti to be removed

from a highway within three days. Renegotiating the terms of this

contract to use the funds designated for prompt litter and graffiti

removal to support another activity or project could be very

difficult. In addition, by bundling multiple phases of a project

into a single contract, P3s can make it more difficult for the

government to change how a project is managed. For example, if the

government wanted to make changes to how a private partner handled

customer complaints and questions on a toll road, it would likely

need to propose amendments to the contract, which could increase the

project's overall cost.

New Risks From Complex Procurement Process.

As discussed earlier, the procurement process for P3s is more

complex than the procurement processes traditionally used for state

infrastructure projects (such as design–bid–build and design–build).

In addition to a project's design, construction price, and schedule,

under P3 approach, the government entity must also evaluate

proposals based on financing, operations, and maintenance. In

addition, P3 procurements can also involve complex negotiations

between the government and the private developers who bid on the

project. As a result, P3s can require the government to perform new

activities and take on certain risks that it may not be experienced

at handling. For example, if the state does a poor job of drafting

agreements or fails to address relevant issues in these agreements,

it could experience unexpected costs or receive lower levels of

service than planned.

Fewer Bidders. According to the

research, infrastructure projects that are relatively expensive and

complex tend to be more ideal candidates for P3s. In addition,

private partners tend to be comprised of multiple companies who

coordinate efforts to develop a P3 bid—each with expertise in a

particular component of the project (such as design and

construction, financing, or maintenance). As a result, few private

developers have the financial resources and technical skills to

compete for P3 projects, especially on their own. According to

experts, P3 projects typically receive between one and three bids.

In comparison, similarly sized projects procured under traditional

public sector approaches typically receive a greater number of bids.

Less competition for a project procured as a P3 could be detrimental

to the government, as more competition for a project generally

reduces the price of a project while increasing its quality.

Some Benefits Achieved to Date

In order to determine whether the state has achieved some of the

intended benefits of P3s, we reviewed the two completed P3 projects

procured by the state'sR 91 Express Lanes and SR 125 Tollway. At the

time of this analysis, however, Caltrans was unable to provide us

with the necessary data to evaluate whether the P3 projects

completed by the state—SR 91 and SR 125—resulted in greater price

and schedule certainty than if the projects were procured under a

more traditional approach. As a result, we reviewed recent state

projects that, while not considered P3s, transferred certain risks

and responsibilities to the private sector. Specifically, we

reviewed those projects procured under design–build and construction

manager at risk contracts. These particular projects are summarized

in Figure 5.

Figure 5

Design–build and Construction Manager

at Risk: Cost and Schedule Outcomes

|

Project

|

Implementing Agency

|

Type of

Procurement

|

Project Completion

|

Percentage Price Increase From Contracta

|

|

SR 73 Toll Road

|

TCAs

|

design–build

|

4 months early

|

—

|

|

SR 241, SR 261, and SR 133

Toll Roads

|

TCAs

|

design–build

|

14 months early

|

—

|

|

SR 22 Carpool lanes

|

OCTA

|

design–build

|

1 week late

|

4.6%

|

|

Contra Costa Justice Center

|

AOC

|

Construction manager at risk

|

1 week early

|

1.2

|

|

Fresno Court Facility

Renovation

|

AOC

|

Construction manager at risk

|

1 month late

|

0.2

|

|

State Office Building in

Oakland

|

DGS

|

design–build

|

On schedule

|

—

|

|

San Francisco Civil Center

|

DGS

|

design–build

|

On schedule

|

1.2

|

|

State Office Building in Los

Angeles

|

DGS

|

design–build

|

3 months late

|

7.3

|

|

State Office Buildings in

Sacramento

|

DGS

|

design–build

|

On schedule

|

10.4

|

|

Caltrans Office Building in

Los Angeles

|

DGS

|

design–build

|

15 months late

|

5.2

|

|

Caltrans Office Building in

Marysville

|

DGS

|

design–build

|

On schedule

|

3.0

|

|

Central Plant Renovation in

Sacramento

|

DGS

|

design–build

|

4 months late

|

0.6

|

Price and Schedule Certainty Generally Achieved.

In terms of the projects reviewed, most of them were generally

successful at staying on budget and schedule. When there were

schedule and cost overruns, they were typically relatively small.

For example, three–fourths of the projects opened to users on

schedule or within one month of the planned deadline. Three–fourths

of the projects were also completed on budget or with less than 5

percent in cost overruns. While there is no way of knowing what the

price and schedule outcomes would have been if these projects were

procured differently (such as a design–bid–build project), the

projects were generally successful at meeting the goal of price and

schedule certainty.

Mixed Results During Operations. The SR

91 Express Lanes and the SR 125 Tollway both experienced problems

during the operational phases of their P3 contracts. Specifically,

while both facilities remained open to the public, Caltrans incurred

additional costs resulting from disputes with its private partners.

For example, the SR 91 contract contained a "non–compete clause"

that prohibited Caltrans or other public agencies from competing

with the tolled lanes built by the private partner. Thus, if public

agencies made any improvements to transportation facilities in the

SR 91 corridor (including minor projects to improve the safety of

the general–purpose lanes of the highway), the private partner

believed that the state would be required to compensate for the loss

of toll revenue if fewer people drove on the tolled P3 lanes due to

these improvements. The issue was litigated in court, but was

ultimately settled when the private partner agreed to sell the

rights of the express lanes to the Orange County Transportation

Authority (OCTA), a local public transportation agency. Since OCTA

assumed control of SR 91, Caltrans has not had any conflicts

regarding the non–compete clause.

The SR 125 project experienced legal challenges that delayed its

completion. Such challenges made the partnership less profitable for

the private partner. Specifically, the lawsuit alleged that

Caltrans, as a partner in the agreement, was partially liable for

losses claimed by some of the private companies involved in the

project. The private partner ultimately declared bankruptcy, with

the court awarding the rights to the remainder of the P3 to a group

of lenders who had financed the project. This group subsequently

sold the agreement to the San Diego Association of Governments.

Given the nature of design–build and construction manager at risk

contracts, the other projects we reviewed did not transfer

responsibility for operating the infrastructure facility to a

private partner after it was built. However, the toll road projects

involving SR 73, SR 241, SR 261, and SR 133 did involve other public

entities being responsible for operating the facilities. This

network of tolled public highways in Orange County (commonly

referred to as "The Toll Roads") are managed by the Transportation

Corridor Agencies (TCAs), which are public agencies led by locally

elected officials. While the TCAs may contract with private

companies to operate the toll roads, they are ultimately responsible

for making key decisions and directly managing the contracts. When

the TCAs encountered problems after the highways became operational,

they were able to end a contract with a private operator who was not

meeting expectations and later rebid the work to a different

company. Using separate contracts and retaining more responsibility

for making key decisions helped avoid some of the unforeseen costs

(such as legal costs) that were incurred with the state's P3

projects.

P3 Best Practices

As part of our examination of the P3 approach, we reviewed

international research and interviewed experts in the field. Based

on our review, we identified a set of best practices that have been

found to maximize the potential benefits of P3s and minimize its

potential limitations. These best practices are summarized in Figure

6 and discussed in more detail below.

Establish Overall P3 Policy and Implement Transparent

Processes

Experts recommend that governments adopt an overall P3 policy to

(1) guide decision–makers when evaluating different procurement

options and (2) inform potential private partners and the public of

the process. For example, experts recommend having a transparent

process so that potential partners are aware of the specific

requirements that must be satisfied to bid on a project and how long

the procurement process will likely take. Such transparency also

helps stakeholders and the public understand how and why a

government entity selected a private company to build or operate

public infrastructure. For example, Virginia created the Office of

Transportation public–private Partnerships to develop a consistent

institutionalized process for P3 procurements, in order to help

attract qualified developers and contractors.

Adopt Criteria to Determine Good Candidates for P3

Projects

International research also finds that it is good practice for

governments to adopt criteria for determining whether projects would

be a good fit for P3 procurement, as not all public infrastructure

projects would benefit from a P3 approach. For example, as we

discuss later in this report, the Legislature could establish

criteria that provide a reasonable means of screening potential P3

projects. Such criteria should not be too prescriptive or

cumbersome. Experts recommend that the screening criteria include

the following:

- Government Benefit From Using

Nonpublic Financing. The screening process should

determine if there is a benefit (such as completing the project

sooner) to the government from financing the project with a private

partner, rather than using public funds upfront to pay for the

project. Typically, relatively expensive projects—with costs

ranging from the hundreds of millions to billions of dollars—are

more likely to benefit from private financing, as it can take

several years to save up enough funds to build a large project

without financing or to get approvals for public financing.

- Technically Complex.

Generally, projects that are technically complex are more likely to

benefit from the innovation or specialized expertise that is

typically associated with P3s. For example, a private partner with

extensive experience designing and building tunnels or bridges may

be able to construct a complex tunnel or bridge more quickly and/or

at a lower cost. On the other hand, projects that are very simple

(such as repaving a road) are not as well suited for the P3 approach

because they are less likely to benefit from innovation and

specialized expertise.

- Ability to Transfer Risks to

Partner. Projects that are good candidates for P3s

generally have significant known risks that the government can

transfer to a private partner. For example, a project that is in the

very early stages of development and does not have a completed

environmental review may lack sufficient information to allow for an

effective transfer of risk. Given these unknown risks, potential

partners may be hesitant to bid on the project or may incorporate

large premiums into their bid. Alternatively, a project with clearly

identified risks (such as if a toll road will generate enough

revenue to finance the project) would be more well–suited as a P3.

- Revenue Source to Repay Financing.

As discussed above, P3s require a revenue source to repay the

financing provided by the private partner. Ideally, a project would

have a dedicated revenue source (such as a toll or user fee) to

repay the money borrowed from the partner. The government entity,

however, could commit to make payments to the partner from

government funding sources, such as tax revenues.

Conduct a Rigorous Value for Money Analysis

Once it is determined that a particular project is a good P3

candidate, experts recommend that the government entity perform a

detailed analysis that compares the project's costs using a P3 to

using a more traditional procurement approach. A commonly used

analysis is a "value for money" (VFM) analysis, which identifies all

the costs of a project (such as the design, construction, and

operation and maintenance of the facility) over the life of the

project or the term of the lease with the private partner. These

costs are then "discounted" over time to determine the project's

cost in net present value. In other words, because the expenditures

take place over several decades and the timing of the expenditures

differ between a P3 approach and the more traditional procurement

approach, the comparisons are adjusted to account for the fact that

money available at the present time is worth more than money

available in the future. Specifically, the VFM analysis should

compare the cost of the different procurement approaches in net

present value terms of delivering the same level of service—both

in terms of the quality of the infrastructure constructed and the

quality of the maintenance and operation services provided.

The VFM analyses can be complex and the underlying assumptions

can significantly influence the outcomes. Thus, most experts

recommend specifying parameters for the assumptions (such as for the

discount rate) so that all potential projects are evaluated with

similar criteria.

Adopt and Implement Project Approval Process

Experts recommend maintaining a process to approve projects for

P3 procurement that allows good candidates to proceed. The approving

entity (such as the Legislature or an independent board), which is

typically separate from the agency sponsoring the project, should

verify that (1) the project satisfies most of the established P3

criteria and (2) the VFM analysis shows that a P3 procurement is the

best option. In addition, P3 experts recommend obtaining project

approval prior to having potential partners bid on the project. This

is because private developers may not bid on a project if they are

unsure whether the approving entity might stop it from moving

forward.

Establish Government Expertise in P3s

Another P3 best practice is for government entities to develop

expertise regarding P3s, in order to better protect public resources

when entering into large contracts with private partners.

Experienced departmental staff can make it easier for the state to

handle P3 workload quickly and thoroughly, as well as effectively

communicate with the private sector. Governments could use private

consultants to help with this workload.

Our research also found that P3 expertise can reside at multiple

levels of government. For example, PPP Canada provides information

and assistance to Canada's provincial and municipal governments on

the use of P3s. At the provincial level, Partnerships BC in British

Columbia provides specialized services, such as managing projects

and facilitating communication with the private sector. In addition,

experts recommend reviewing the outcomes of P3 projects at various

stages to allow a government entity to determine what worked well

and what problems were encountered on each project. The lessons

learned can be used to inform future P3 procurements.

State's Use of P3s Falls Short of Best Practices

As we discussed earlier in this report, existing state law

authorizes Caltrans, AOC, and the HSRA to use P3s to procure certain

types of infrastructure. In analyzing their use of this authority,

we generally found that the practices of Caltrans and AOC are not

necessarily aligned with P3 best practices. (At the time of this

report, HSRA had not entered into any P3 contracts.) For example,

our analysis indicates that these departments did not use clear P3

processes and appear to have selected projects not well suited for a

P3 procurement—meaning the Presidio Parkway project and the Long

Beach courthouse project. Our findings regarding each of these

projects are summarized in Figure 7 and described in detail below.

State Lacks Transparent P3 Processes

As discussed above, having clearly defined and transparent P3

processes is considered a best practice. However, our review found

that the state's use of P3 procurement for the Presidio Parkway and

Long Beach courthouse projects lacked transparent frameworks and

clear processes. For example, when

Caltrans used a P3 procurement for the Presidio Parkway, the

department lacked a transparent framework for selecting the project

and conducting a VFM analysis. It did not release a draft P3 program

guide until December 2011, one year after signing the agreement for

Presidio Parkway. While the guide addresses many procedural

questions regarding the department's future use of P3s, it does not

establish a consistent process for evaluating potential P3 projects

through the use of a VFM analysis. We think this is a significant

shortcoming of the guide because establishing VFM processes and

parameters is important to ensure that projects are evaluated on a

consistent basis using reasonable assumptions. The Caltrans draft P3

program guide also does not address how project evaluation, review,

and procurement responsibilities will be carried out when the state

partners with local transportation agencies. Specifically, the guide

does not lay out how the lead agency will be determined and which

entity is responsible for certain tasks, such as review and

oversight. As a result, various local agencies that we talked to

appear to have different understandings of what will be required of

them for P3 projects.

Similarly, AOC did not use a transparent framework in selecting

the Long Beach courthouse to be a P3 project. For example, AOC did

not develop guidelines for selecting potential P3 projects and

conducting VFM analyses. More importantly, at the time of this

report, AOC had not developed transparent criteria or processes for

determining potential P3 projects in the future. For example, it is

unclear how AOC will identify projects that are likely to benefit

from a P3 approach and evaluate potential projects through the use

of VFM analyses.

Selection Criteria for Recent Projects Not Aligned to

Best Practices

Our analysis indicates that the processes used to identify the

two recent state projects for P3 procurement—the Presidio Parkway

and the Long Beach courthouse—included few of the best practice

criteria.

Presidio Parkway Selection Was Problematic.

According to Caltrans staff, the Presidio Parkway project was

selected as a P3 candidate primarily based on two criteria: (1) an

estimated project cost of more than $100 million and (2) a completed

environmental impact review. However, according to the identified

best practices, these two factors alone do not constitute a robust

set of screening criteria. In other words, the selection process for

the project did not include such recommended criteria as the ability

to transfer risk to the private sector and whether the state would

benefit from using non–state financing. While the selection process

for a P3 project does not need to include all of the best practice

criteria, including such criteria does help ensure that the intended

P3 benefits are achieved. Our analysis indicates that if Caltrans

utilized such criteria in its selection process, the Presidio

Parkway project would have been found to be inappropriate for P3

procurement.

For example, the Presidio Parkway project was too far along to

transfer many of the project's risks to a private partner. This is

because the Presidio Parkway's first phase of construction was

already underway using a design–bid–build procurement when the

second phase of the project was selected for P3 procurement. As a

result, potential private partners had limited access to the

construction site, which in turn made them less willing to take on

many of the project's construction risks. For example, the state

retained significant risks regarding the discovery of archeological

artifacts and endangered species. In addition, Caltrans had already

designed about half of the project's second phase prior to awarding

the P3 contract. Thus, the winning bidder may be limited in its

ability to find cost–savings through innovative design and

construction techniques because it must adhere to certain

specifications it did not design.

Long Beach Courthouse Selection Was Problematic.

According to AOC staff, the Long Beach courthouse project was

selected as a P3 candidate based primarily on two criteria: (1) it

was one of the largest court construction projects considered at

that time and (2) the Long Beach area has a competitive market for

the type of property management staff needed to operate a P3.

Similar to the selection of the Presidio Parkway project, the

selection process for the Long Beach courthouse project did not

include much of the recommended best practice criteria. For example,

the selection process did not evaluate whether the project is

technically complex. While the ideal level of complexity for a P3 is

difficult to define in specific terms, the Long Beach courthouse

project lacks unique or complex features that would likely benefit

from innovative design and construction techniques. Accordingly, our

analysis indicates that if AOC utilized best practice criteria in

its selection process, the Long Beach courthouse project would have

been found to be inappropriate for P3 procurement.

VFM Analyses Based on Assumptions That Favored P3

Procurement

As described above, VFM analyses can help decision–makers compare

the cost of a project under different procurement options. Both

Caltrans and AOC contracted with private consultants to perform such

analyses for the Presidio Parkway and Long Beach courthouse

projects. Specifically, the analyses compared the costs of

constructing the project under a more traditional approach to a P3

approach. The VFM analyses found that the state would benefit

financially if the Presidio Parkway and Long Beach courthouse

projects were procured as P3s—meaning it would be cheaper to have a

private developer build and operate the planned facility. Our review

of these particular analyses, however, indicates that both VFM

analyses were based on several assumptions that are subject to

significant uncertainty and interpretation and tended to favor a P3

procurement. If a series of different assumptions were made, the VFM

analyses would have shown that the P3 procurement on the Presidio

Parkway and Long Beach courthouse projects would be more expensive

in the long run than a more traditional procurement.

Assumptions in Presidio Parkway Analysis Favored P3.

Some of the key assumptions made by Caltrans in the VFM analysis of

the Presidio Parkway project that tended to favor P3 procurement

include:

Relatively High Discount Rate.

In order to calculate the net present cost of the project, Caltrans'

VFM analysis discounts the cost of the project under a traditional

approach and a P3 procurement by 8.5 percent per year. As discussed

above, this adjustment is intended to reflect that money spent in

the near term is more valuable than money spent in the future. In

the past, our office has suggested that a 5 percent discount rate be

used for such analyses, but acknowledges there is no one "right"

discount rate. We also note that the state's long–term borrowing

rate is currently less than 5 percent.

Unjustified Tax Adjustment.

The VFM analysis for this project also included a $167 million

adjustment in order to account for increased tax revenues (such as

from corporate taxes) that the private developer would pay to the

state under the P3 approach. The analysis assumed that if the

project was not procured as a P3, the state would not receive these

additional revenues. However, we found the adjustment included

mostly revenues related to potential federal taxes, which would not

directly benefit the state. Thus, the adjustment made a P3 approach

look more favorable than is warranted.

Assumed Early Payment of Cost

Overruns. Under a more traditional procurement

approach (such as design–bid–build), Caltrans assumed the Presidio

Parkway project would exceed its budget by $125 million and that

such cost overruns would need to be paid for at the start of

construction. However, such overages do not typically occur at the

start of a project, but rather as a project progresses through

construction. While some consideration of the potential for cost

overages is reasonable, Caltrans' method relies on subjective

judgment rather than objective evidence. Consequently, the chosen

method has the effect of overstating the net present cost of the

project under a traditional procurement approach, thereby favoring a

P3 procurement approach for the project.

Failed to Account for Competitive

Bidding Environment. The Caltrans' VFM analysis, which

was prepared in February 2010, also did not take into account the

competitive construction bidding environment that occurred around

that time. During this period, Caltrans awarded construction

contracts that were on average 30 percent below the project's

original cost estimate. While it is not possible to know exactly

what the bids would have been if the Presidio Parkway project had

been procured using a more traditional procurement, it appears

reasonable to assume that the project could have been awarded at a

much lower cost than the engineer's cost estimate.

Our analysis indicates that utilizing a different set of

assumptions (such as a discount rate of 5 percent and excluding the

assumed tax adjustment) would result in the cost of the Presidio

Parkway project being less—by as much as $140 million in net

present value terms—in the long run under a traditional procurement

approach than the chosen P3 approach.

Assumptions in Long Beach Courthouse Analysis Favored

P3. Some of the key assumptions in the VFM analysis of

the Long Beach courthouse that tended to favor P3 procurement

include:

- Unjustified Tax Adjustment.

Similar to the Presidio Parkway project, the VFM analysis for the

Long Beach courthouse project included a $232 million adjustment to

account for increased tax revenues that would be paid for by the

private developer under the P3 approach. A major component of this

adjustment reflects revenues from federal taxes. Since additional

federal tax revenues would not directly benefit the state, there

appears to be little to no justification for increasing the cost of

using a traditional procurement approach to reflect the federal

taxes that would be paid by a private developer.

- Overstated Cost Overruns.

The VFM analysis assumed that using AOC's more traditional

procurement approach of construction manager at risk—rather than a

P3 procurement approach—would result in construction cost overruns

for the Long Beach courthouse project totaling $128 million (about

30 percent of the project's estimated cost). However, given that AOC

has procedures in place to prevent such cost overages and has not

experienced them with recent court construction projects, this

assumption has the effect of overstating the cost of the project

under a construction management at risk approach.

- Leasing of Additional Space.

The AOC's VFM analysis assumes that under the P3 approach, the

courthouse project would include space that would initially be

leased by the private developers to other entities, but could

eventually be used by the court. The VFM analysis also assumes this

additional space would be needed by the court in Long Beach in the

future, and builds the cost of leasing this additional space into

its estimates. This factor adds $260 million in costs to a

traditional procurement of the Long Beach courthouse project, but

only $69 million to the cost of the P3. The higher cost under a

traditional approach assumes that a separate building would be

leased and that the leased building would need substantial

modifications. The analysis for the traditional procurement also

assumes increased costs for security officers to monitor the leased

building. While there is some basis for estimating a higher cost for

the potential need to lease additional space under a traditional

procurement approach, the AOC has not conclusively demonstrated that

all of this additional space would be needed by the court in Long

Beach. Moreover, AOC's other courthouse construction projects

ordinarily do not include this kind of extra space.

- Project Completion.

The AOC–s VFM analysis assumes that it would take 14 months longer

to complete the Long Beach courthouse under construction manager at

risk procurement than as a P3 project. Accordingly, the analysis

uses different timelines to discount the costs of the project under

each type of procurement. The way the VFM analysis adjusts for these

assumed differences in timing effectively increases the cost of a

traditional procurement in net present value terms. However, it is

not evident that such a procurement would necessarily take 14 months

longer—especially in view of the considerable flexibility state law

gives AOC with respect to its construction contracting methodology.

Our analysis indicates that utilizing a different set of

assumptions than those discussed above (such as excluding the

assumed federal tax adjustment and leasing costs) would result in

the cost of the Long Beach courthouse project being less—by as much

as $160 million in net present value terms—in the long run under a

traditional procurement approach than the chosen P3 approach.

State Law Lacks Thorough Project Approval Processes

Our analysis found that for both the Presidio Parkway and Long

Beach courthouse projects, the state did not utilize a thorough

process for selecting P3 projects. Having thorough processes in

place could have prevented Caltrans and AOC from entering into a P3

agreement for each project, or at least required changes to

negotiate lower prices and better ensure that the intended P3

benefits are achieved.

For P3 transportation projects, state law requires the CTC to

conduct a limited review of the basic features of each project

sponsored by Caltrans or a regional transportation agency. (We note

that in reviewing the Presidio Parkway project, CTC extended its

evaluation beyond the basic requirements to further review the

project's financing.) However, state law does not require the

commission or another entity to conduct an overall review of whether

(1) the state would benefit from procuring a particular project as a

P3 and (2) whether a particular P3 contract is structured to

maximize the state's benefits. Moreover, while state law does

provide a 60–day period for the appropriate legislative fiscal and

policy committees and PIAC to review P3 proposals before Caltrans

can sign an agreement with a private developer, state law does not

require that Caltrans address any of the concerns raised in these

reviews.

For court construction projects, state law authorizes the Joint

Legislative Budget Committee and DOF to review a potential P3

project before AOC can fully develop the project's concept.

Accordingly, the Legislature reviewed and approved the general

criteria used by AOC to select the private partner for the Long

Beach courthouse project. However, the Legislature did not have an

opportunity to review and comment on the VFM analysis before it was

finalized and the contract was signed with the private developer.

State Lacks P3 Expertise

As previously discussed, experts recommend that government

entities develop expertise regarding P3s in order to better protect

public resources when entering into large contracts with private

developers. Our review, however, finds that such expertise within

state government has not been sufficiently developed in California.

PIAC Has Limited P3 Expertise. The PIAC

was established in 2009 to assemble and share research on best

practices and lessons learned from transportation P3s around the

world. However, based on our discussions with staff at the BT&H

Agency and our review of various PIAC documents (including the

minutes from the seven PIAC meetings that have taken place), we find

that PIAC has done little to implement best practices for

transportation P3s. The only steps that PIAC appears to have taken

in this regard are to post reports containing information on P3 best

practices on its website and to contract for two reports on P3s. We

also note that the commission currently lacks members with in–depth

expertise on issues such as state financing, state procurement, and

state labor issues. Perspectives on these issues could help to

ensure that the state maximizes its benefits when using P3s.

No Systematic Approach for Reviewing Lessons Learned.

Our review also finds that the state does not have a systematic

process for identifying and applying lessons learned from prior P3

projects. Although Caltrans is the only state agency to have entered

into multiple P3 agreements, it currently lacks a formal process for

reviewing past P3 projects in order to maximize benefits and avoid

repeating past mistakes. We understand that AOC is currently

developing a review and reporting process for the Long Beach

courthouse project. Once completed, these reports may provide

helpful lessons learned about AOC's use of P3 procurement.

Recommendations to Maximize State Benefits from P3s

In this report, we reviewed the state's experience with P3s and

identified several instances where the best practices identified in

existing P3 research have not necessarily been followed. Based on

our review and findings, we have identified several opportunities

for the state to further maximize its benefits when deciding to

procure a state infrastructure project as a P3. Our specific

recommendations are summarized in Figure 8 and discussed in detail

below.

Specify P3 Project Selection Criteria

As previously mentioned, the state's processes for selecting P3

projects are inadequate and not necessarily based on selection

criteria identified in the research as best practices. Accordingly,

we recommend that the Legislature adopt legislation requiring that

each state department with P3 authority utilize certain criteria

when evaluating whether a particular project should be procured as a

P3. According to the research, these selection criteria should not

be highly prescriptive, but rather should provide general guidance

regarding the selection of potential P3 projects. Such an approach

would provide for greater consistency across departments in terms of

how P3 projects are selected. The selection criteria should include

being a technically complex project, as well as a project that can

transfer risks to a private partner and benefit from non–state

financing. In addition, the Legislature may want to specify whether

P3 projects must have a revenue source, such as a user fee.

Require Analysis of a Range of Procurement Options

In order to determine which procurement approach would most

effectively benefit the state, we recommend that the Legislature

adopt legislation requiring a comparative VFM analysis of a range of

procurement options (including design–bid–build, design–build, and

P3) for all potential P3 infrastructure projects. Evaluating a range

of procurement options would allow the state to better balance the

potential benefits of increased private sector involvement with the

potential risks unique to each project. In contrast, the benefit of

evaluating only two procurement approaches—as was done by Caltrans

and AOC—can be limited. This is because it does not evaluate other

options (such as design–build), which in some cases may be the best

option.

We also recommend that the Legislature specify in statute that

such VFM analyses:

- Exclude Federal Tax Adjustments.

Increased federal tax revenues do not directly benefit the state and

should not be included in a VFM analysis.

- Apply Costs to Expected Year of

Expenditure. Project costs should be accounted for in

the year they are likely to be incurred, in order to effectively

estimate the project's likely total cost in the long run.

- Use Current Construction Cost

Estimates. Construction cost estimates should be based

on the current bidding environment in the state.

- Include a Sensitivity Analysis.

A sensitivity analysis can help to indicate how the results of the

VFM analysis might change with a different set of assumptions.

Specifically, this analysis should evaluate project costs and

revenues with a range of reasonable discount rates to show how

differing assumptions can influence the outcome of the VFM analysis.

If a project will generate revenue, such as from tolls or fares, a

reasonable range of revenues should also be evaluated in the

sensitivity analysis.

Modify Structure and Responsibilities of PIAC

In order to help ensure that PIAC effectively assembles and

shares research, best practices, and lessons learned from

transportation P3s around the world, we recommend the Legislature

adopt legislation to:

- Expand PIAC's Authority.

In order to provide a consistent review and approval process for the

use of P3 procurement, we recommend

expanding the PIAC's role to require the commission to approve all

state P3 projects, as discussed in detail later in this report. We

also recommend expanding the scope of PIAC to all types of

infrastructure projects, rather than only those related to

transportation. Having the commission involved in all types of P3

will further the state's P3 expertise. To reflect this broader

scope, we also recommend making PIAC an independent commission,

rather than part of the BT&H Agency.

- Direct PIAC to Evaluate Other

Departments for P3 Authority. We have found that

certain types of projects may benefit the state if procured using a

P3. It is possible that state departments other than Caltrans, AOC,

and HSRA will have projects meeting these P3 criteria. Accordingly,

we recommend that the Legislature direct PIAC to review the types of

projects planned by other state departments and recommend to the

Legislature whether P3 authority should be granted to additional

state departments.

- Broaden PIAC's Expertise.

In order to ensure that PIAC has the expertise necessary to advise

state departments on all types of P3s, we believe it would be

beneficial for the commissioners to have a broad mix of expertise

related to P3, as well as state finance and procurements.

Specifically, we recommend that the Legislature appoint some of the

commissioners and that, in addition to P3 experts, the

commission include the Director of the Department of General

Services (or a representative), and the State Treasurer (or a

representative). The Legislature could also consider reducing the

number of commissioners on PIAC to a more manageable size.

- Require PIAC to Develop and

Implement Best Practices. We recommend requiring PIAC

to (1) develop a set of best practices for P3 projects in

California, (2) provide state departments specific steps for

implementing those best practices, and (3) provide technical

assistance to state agencies planning to pursue a P3. Consistent

with the research, it would benefit the state to have such expert

advice provided from the initial project screening stage through the

procurement and administration of a P3 contract. We also recommend

that the Legislature require periodic reports from PIAC in its

efforts in developing and implementing P3 best practices.

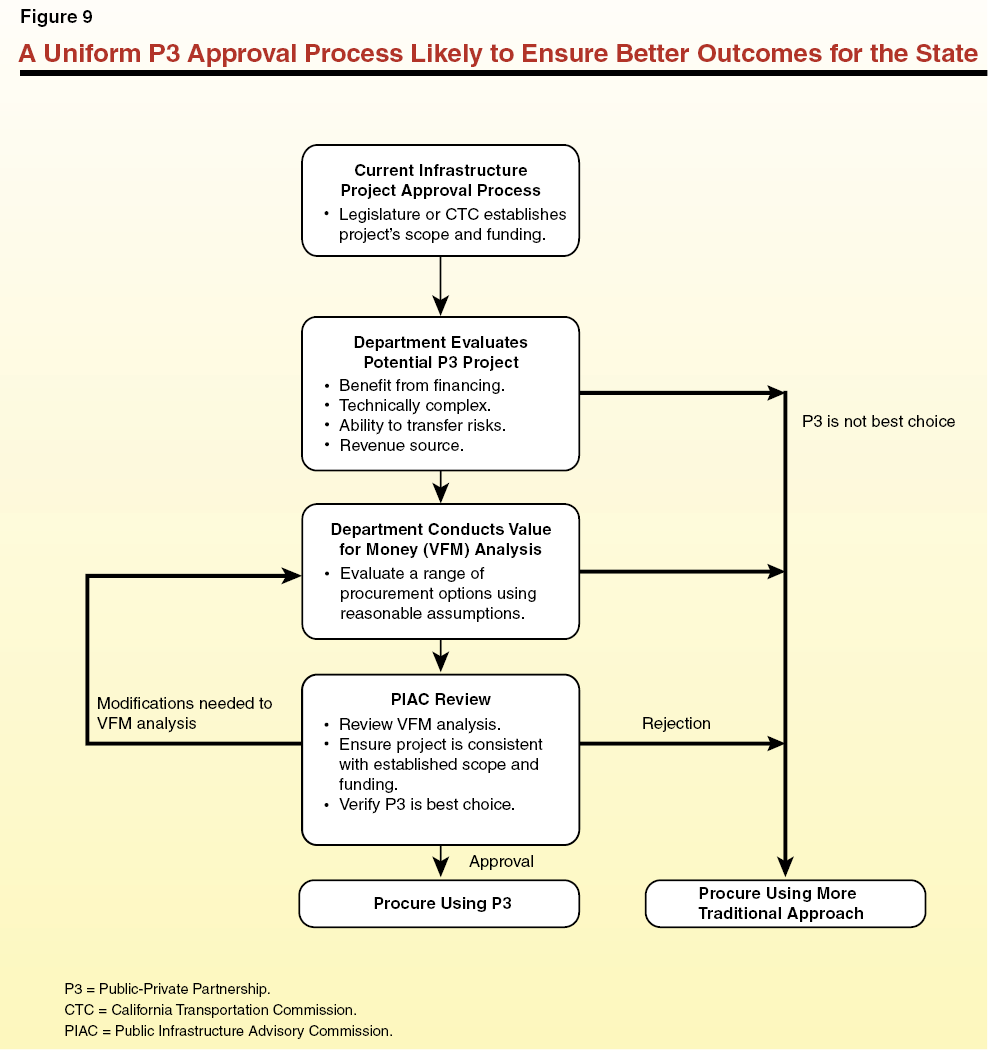

Improve Consistency of state's P3 Approval Process

We recommend that the Legislature adopt legislation to make the

process for reviewing and approving P3 projects consistent and

thorough across those state departments authorized to pursue such

projects. Specifically, we recommend requiring the use of the review

and approval process summarized in Figure 9 and discussed in detail

below.

Require PIAC to Approve P3 Concept and VFM Analysis.

Our above recommendations to modify the structure and

responsibilities of PIAC would make it well–suited to review and

approve a department's proposed use of P3 procurement. As shown in

Figure 9, we recommend that the Legislature require departments to

provide a VFM analysis and other relevant project information (such

as draft procurement documents) on all proposed P3 projects to PIAC.

Under our recommended process, if PIAC identifies

concerns with a P3 proposal, the commission would require the

department sponsoring the project to perform additional analyses and

resubmit the proposal for subsequent review. If a project does not

satisfy the above P3 criteria, we recommend that PIAC have the

authority to reject the use of a P3 approach, and direct the

department to use another procurement method. Thus, we recommend

that the Legislature adopt legislation directing PIAC to implement a

process to evaluate (1) whether a P3 project proposal is consistent

with the scope and cost approved in the state's current capital

outlay processes (meaning either by the Legislature or CTC) and (2)

whether using a P3 approach would be the best procurement option.

Conclusion

Based on our review of existing research, we believe that P3

procurement—if done correctly—has merit and may be the best

procurement option for some of the state's infrastructure projects.

In certain instances, sharing risks with a private partner and using

a diverse financing package (including private loans) may even be

the only way to build those projects that are both very complex and

expensive. For such projects, the use of P3 procurement can make the

price and schedule more certain by transferring various project

risks to a private partner. In addition, access to specialized

expertise and private financing could have the effect of

accelerating projects and providing other benefits to the state.

However, the state does give up considerable control over the

management and long–term funding priorities of a project that is

constructed under a P3 approach. This limitation and others must be

considered carefully when considering a decades–long partnership.

We also find that implementing certain P3 best practices

identified in the research can better ensure that the intended

benefits of P3s to the state are achieved. Thus, in order to

maximize the state's benefits from P3s, we recommend that the

Legislature take a series of steps to ensure that such best

practices are followed in developing and implementing future P3

projects. For example, we recommend specifying P3 project selection

criteria and improving the state's approval process to utilize an

entity with expertise in P3s. More importantly, our proposals to

develop P3 expertise and better evaluate potential P3 projects would

provide for a better understanding of the actual benefits and

limitations of P3 projects. Finally, as the state gains experience

with P3s, the Legislature may want to consider whether the existing

P3 authorization provided to Caltrans and AOC should be expanded to

other departments.