In 1960, California adopted a Master Plan for Higher Education that assigned distinct missions to California’s two public university systems and its community college system. It charged the University of California (UC) with serving a relatively small number of the most academically accomplished high school graduates statewide, while the community colleges were to serve their local communities as open–access institutions. While the Master Plan did not specifically assign to the California State University (CSU) a regional role, CSU campuses—through their admissions policies and other practices—largely focused on regional education needs. Recent enrollment management efforts undertaken at several campuses have the potential to weaken that regional role by leaving some CSU–eligible students without guaranteed access to their local campus.

In this report we review how the Master Plan envisioned CSU’s place in the higher education system, and assess how the university has carried out its role in the face of changing enrollment demand and funding limitations. We conclude that CSU’s regional role is an important component of the state’s higher education system, and recommend that the Legislature take steps to protect that focus in the face of enrollment pressures and efforts by some campuses to become more selective. Specifically, we recommend that the Legislature (1) formalize a regional education role for CSU in statute, (2) codify its expectations for CSU’s eligibility pool, and (3) direct CSU to adjust its enrollment policies accordingly.

The state Master Plan for Higher Education, adopted in 1960, promises access to a baccalaureate education for all qualified students through three public higher education segments, each with a distinct mission. Specifically, the California Community Colleges (CCC) are to provide academic and vocational instruction through the first two years of undergraduate education. Their mission also includes remedial instruction, English as a Second Language instruction, and other education services. The UC is designated the state’s primary academic research institution and is to provide undergraduate and graduate instruction in the liberal arts and sciences. The UC has exclusive jurisdiction over instruction in the profession of law and graduate instruction in the professions of medicine, dentistry, and veterinary medicine and awards virtually all public doctoral degrees in the state.

The Master Plan created CSU out of the state teacher colleges, which had been under the state Department of Education. Today, CSU comprises 23 campuses and is governed by an appointed Board of Trustees. The Master Plan directs CSU to offer undergraduate and graduate instruction leading to bachelors and masters degrees in the liberal arts and sciences, the applied fields, and the professions, including the authority to award doctoral degrees jointly with authorized institutions.

The assigning of distinct missions to the three segments has been widely regarded as one of the most important, valuable, and frequently copied elements of the Master Plan. It has helped to justify state support for two separate public university systems, impede mission–creep among institutions, contain growth in costs, and facilitate college access for all eligible students.

In addition to assigning the higher education segments distinct missions, the Master Plan also directs each segment to draw its students from different, though overlapping, eligibility pools. As a result, the segments have different levels of selectivity.

Freshman Eligibility. The Master Plan directs CSU to select its freshmen from the top one–third of high school graduates, placing it in a middle ground between UC (which selects from among the top one–eighth) and the community colleges (which admit any applicant capable of benefiting from instruction). The CSU defines its eligibility pool by an “eligibility index” which combines grade point average (GPA) and standardized test scores from the SAT or ACT. In general, a student with a lower GPA needs a higher standardized test score. In addition, students must obtain a grade of “C” or higher in certain college preparatory coursework. The eligibility index in place for 2010–11 is shown in Figure 1. (The CSU periodically adjusts the index to capture the top one–third of high school graduates.)

Figure 1

California State University Eligibility Index

For High School Graduates Applying to CSU’s 2010–11 Academic Year (Minimum Score Necessary)

|

Grade Point

Average (GPA)

|

ACT

|

Or

|

SATa

|

|

>=3.0

|

n/ab

|

|

n/ab

|

|

2.99

|

10

|

|

510

|

|

2.9

|

12

|

|

580

|

|

2.8

|

14

|

|

660

|

|

2.7

|

16

|

|

740

|

|

2.6

|

18

|

|

820

|

|

2.5

|

20

|

|

900

|

|

2.4

|

22

|

|

980

|

|

2.3

|

24

|

|

1060

|

|

2.2

|

26

|

|

1140

|

|

2.1

|

28

|

|

1220

|

|

2

|

30

|

|

1300

|

|

<2.0

|

n/ab

|

|

n/ab

|

Transfer Eligibility. At the time the Master Plan was adopted in 1960, CSU was requiring that community college students achieve a GPA of at least 2.0 in order to be eligible for admission as a transfer student. The Master Plan report expressed concern about this threshold (particularly as applied to students whose high school performance had been deficient) and called on CSU to assess whether a higher community college GPA should be required.

Currently, CSU requires that upper–division transfer students have completed at least 60 semester units of coursework with an overall GPA of at least 2.0. Students must also complete four general education requirements: oral communication, English composition, critical thinking, and math/quantitative reasoning with a “C” or higher.

Enrollment Priorities. State law specifies enrollment priorities for the public universities. Generally, CSU is to maintain a student body comprised of 40 percent lower division students and 60 percent upper division students (achieved in part through transfer admissions). Statute also directs the universities to assign admission priority to specified groups of students. (See nearby box.) Community college transfer students are to be granted one of the highest priority levels. Students who are place bound are also recognized among the priority groups.

|

The Education Code requires that California State University (CSU) and University of California (UC) campuses admit students in the following priority order:

- Continuing undergraduate students in good standing.

- California Community College (CCC) transfer students who have successfully concluded a course of study in an approved transfer agreement program.

- Other CCC students who have met all of the requirements for transfer.

- Other qualified transfer students (California residents transferring from UC or CSU campuses or from independent colleges who meet the admission standards).

- California residents entering at the freshman or sophomore levels.

Further, the Education Code specifies that within each of the five categories above that the following groups of applicants receive priority consideration:

- Veterans who are residents of California.

- Transfers from CCC.

- Applicants who have been previously enrolled at the campus to which they were applying, provided they left the institution in good standing.

- Applicants who have a degree or credential objective that is not offered generally at other public postsecondary institutions.

- Applicants for whom the distance involved in attending another institution would create financial or other hardships.

|

Generally, CSU campuses have served as regional institutions, developing relationships with local high schools and community colleges and granting priority admission to local students. This regional focus, however, is not specifically required by statute.

Master Plan Assumes, but Does Not Require, Regional Approach. While the Master Plan does not specifically require CSU to serve a regional role, such a role clearly was envisioned in discussions during the Plan’s development. For example, in the 1955 Restudy of the Needs of California in Higher Education that informed the development of the Master Plan, the state’s education leaders argued that state college campuses (excluding the San Luis Obispo campus) should “continue to be responsive to well–documented regional needs.” Moreover, the Master Plan’s approach to new campus locations suggests a focus on regional needs. New campus locations were chosen to increase higher education access for California students using regionally focused criteria:

- The relative numbers of high school graduates, the location of existing institutions in the various areas of the state, and the relation between their capacity and the estimated enrollment in the areas served by each institution.

- The relative number of potential students within reasonable commuting distance of each of the proposed sites.

The framers of the Master Plan recognized that location and enrollment priorities were key to CSU access and emphasized that priority be given to students who would have difficulty attending an out–of–area campus.

CSU Campuses Have Behaved Like Regional Institutions. Admission policies and practices at CSU’s campuses have reflected a focus on regional needs. Campus outreach programs have targeted high schools within their local service areas, even while some campuses developed reputations as “destination campuses” with a significant portion of applications coming from further afield. Even then, serving large numbers of out–of–area students has not historically been in conflict with serving local needs. With the exception of the San Luis Obispo campus (discussed below), CSU campuses have until recently been able to accommodate all eligible local applicants.

Although the Master Plan’s eligibility policy promises access to every eligible applicant who applies, CSU’s budgetary resources in any given year are finite. The General Fund appropriation for CSU in the annual budget act typically is based on a target enrollment level that the university is expected to serve. The statewide Chancellor’s office must work with campuses to manage enrollment demand to achieve enrollment totals close to their targeted levels, while still ensuring that all eligible applicants are offered an enrollment slot. Achieving these twin goals sometimes has involved making it harder for students to submit eligible applications—for example, by moving application deadlines or modifying transfer requirements—but qualified applicants who were attentive to (and met) CSU’s admission requirements could count on admission. Conversely, some campuses have at times sought to increase enrollment by easing application requirements, such as extending application deadlines up to the beginning of the term. (See nearby box for a recent example of CSU’s efforts to manage enrollment in the face of a changing state budget.)

|

Facing increasing enrollment demand at a time of declining state budget support, the California State University (CSU) Chancellor’s Office in 2009 took significant steps to bring enrollment into line with available resources. The Chancellor’s Office planned a systemwide enrollment reduction for the 2010–11 year of approximately 30,000 full–time equivalent (FTE) students, or about 9 percent lower than prior–year levels. (Among other things, this enrollment target assumed CSU would not receive an enrollment funding augmentation in 2010–11.) To achieve this enrollment reduction, CSU instituted new systemwide enrollment constraints and authorized a wide range of enrollment management methods to be employed by the individual campuses, including a fast–track process for declaring impaction.

Contrary to CSU’s early assumptions, the 2010–11 Budget Act included substantial General Fund augmentations. Part of this funding was tied to CSU’s meeting an enrollment target of 339,873 FTE students, or about 30,000 FTE students more than the system’s target. (The budget act requires that CSU return some funding if it fails to meet the specified enrollment target.) Complicating matters, the budget was not adopted until October, well past the beginning of the fall term. As a result, campuses found themselves having to significantly increase enrollment for the spring term in order to meet the enrollment target established in the budget act. At the time this report was prepared, it was unknown whether CSU would succeed in meeting that enrollment target. |

In the decades after the Master Plan was adopted, enrollment to CSU (and to the other segments) increased substantially. Partly this was driven by population growth, but it also reflected the increased importance of college degrees. Although new campuses were opened and enrollment capacity increased, some campuses began to experience difficulty accommodating all eligible applicants.

For many years, California Polytechnic State University San Luis Obispo (Cal Poly) had stood out as a more selective “destination” campus that maintained admissions criteria that exceeded systemwide eligibility. Not even local applicants were guaranteed admission to Cal Poly programs, and more than 90 percent of admitted students came from more than 90 miles away. Then, in the early 1990s, San Diego State University (SDSU) began to move in a similar direction, requiring applicants for various programs and majors to meet admissions criteria that exceeded systemwide eligibility.

Desiring to create a more uniform policy for campus admissions, the CSU Board of Trustees appointed a task force to examine systemwide admissions issues, including impaction (described in the next section). According to official documents, the “key policy question” confronted by the task force was “the extent to which CSU campuses should provide access to fully eligible local applicants.” After extensive discussions, the task recommended a new systemwide policy that permitted campuses to use a variety of enrollment management tools (see Figure 2) while guaranteeing all CSU–eligible students admission to a local CSU campus. The Trustees adopted the task force’s recommendations in 2000.

Figure 2

Examples of Enrollment Management Techniques

|

|

- Adjust application deadlines.

|

- Restrict lower–division transfers.

|

- Establish prerequisites for admission to upper–division status.

|

- Require incoming students to attend orientation and/or pay enrollment deposits.

|

- Make offers of admission provisional on meeting conditions, such as completing courses in progress at time of application, maintaining minimum grade point average, and providing supporting documents.

|

- Implement standards for academic disqualification (for example, do not permit students without good academic standing to reenroll).

|

- Reduce the number of students admitted by exception.

|

- Impose unit caps for currently enrolled students.

|

- Declare program or campus “impaction,” allowing campuses to use supplemental eligibility criteria.

|

An especially powerful enrollment management tool is “impaction,” whereby admissions criteria can be raised above the systemwide requirements for certain programs or groups of students. In contrast to most other enrollment management techniques (which still guarantee a spot for all eligible applicants to a campus), impaction allows campuses or programs to deny admission to applicants who do not meet enhanced requirements beyond statewide eligibility. There are two primary categories of impaction:

- Campus impaction can be triggered when the number of qualified applicants to a campus exceeds campus capacity. An impacted campus may establish admissions criteria for all nonlocal applicants that are stricter than systemwide minimum eligibility. Consistent with the Trustees’ policy of protecting local access, all local applicants who meet systemwide eligibility are guaranteed admission to the campus. This points to a key distinction between how UC and CSU fulfill the eligibility guarantees called for by the Master Plan: while UC regularly redirects applicants from oversubscribed campuses to open ones, CSU has generally sought to ensure admission to each applicant’s local campus (while sometimes restricting applicants’ access to nonlocal campuses).

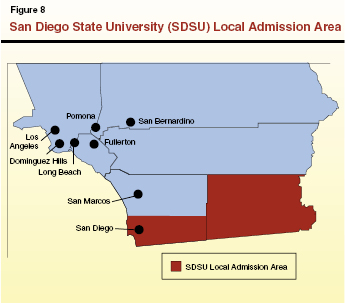

Under the local admission guarantee, each impacted campus designates a local admission area. Guaranteed admission is extended to first–time freshmen and upper–division transfer students who meet systemwide eligibility criteria, and whose high school or community college lies within the local admission area. Students from outside the local area must meet the supplemental eligibility criteria. Figure 3 describes the various local admission areas at the end of 2010.

- Program impaction can be triggered when the number of qualified applicants to a particular program—such as mechanical engineering or nursing—exceeds available space. Impacted programs may establish supplemental admissions criteria for all applicants. In other words, there is no local admissions guarantee for impacted programs, although local students may be awarded extra eligibility index points to help make them more competitive. Historically, only a relatively small number of programs were impacted—primarily programs with unusually high demand, or more costly programs with enrollment limited by resource constraints.

Tension With Local Guarantee. About three quarters of CSU campuses are impacted, and all of them have at least some impacted programs. There is a tension between campus impaction (which guarantees local students’ access to the campus) and program impaction (which provides no such guarantee). The more programs that are impacted at a campus, the fewer options are afforded to a local student who only meets systemwide minimum eligibility. At some point, a large percentage of impacted programs undermines the local guarantee provided by campus impaction. As described below, several campuses have declared all their programs to be impacted.

Figure 3

CSU Local Admission Areas for First–Time Freshmena

|

Campus

|

Local Admission Area

|

|

Chico

|

All high schools (HS) in counties of Butte, Colusa, Glenn, Lassen, Modoc, Plumas, Shasta, Siskiyou, Sutter, Tehama, and Yuba, and four school districts in Trinity: Mountain Valley, Southern Trinity, Trinity Alps, and Trinity HS.

|

|

Fresno

|

All HS in Fresno, Kings, Madera, Tulare counties, and partner schools in other counties.

|

|

Fullerton

|

All HS in Orange County, Chino, Corona/Norco, Walnut, Whittier, and Alvord School District.

|

|

Humboldt

|

All HS in Del Norte, Humboldt, northern Mendocino, and western Trinity counties.

|

|

Long Beach

|

The following school districts: ABC, Anaheim (Cypress and Oxford only), Bellflower, Compton, Downey, Huntington Beach, Long Beach, Los Alamitos, and Paramount.

|

|

Los Angeles

|

All HS located east to 605 freeway and the Los Angeles County line, west to 405 freeway, south to Highway 42 (Firestone Blvd.), and north to Los Angeles County line.

|

|

Northridge

|

All HS in main portion of Los Angeles County and Ventura County.

|

|

Pomona

|

All HS west of the 15 freeway, north of the 60 freeway, east of the 605 freeway, and south of the 210 freeway.

|

|

Sacramento

|

All HS in El Dorado, Placer, Sacramento, San Joaquin, Solano, and Yolo Counties.

|

|

San Bernardino

|

The following school districts in San Bernardino County: Apple Valley, Chaffey, Colton, Fontana, Hesperia, Morongo, Redlands, Rialto, Rim of the World, San Bernardino City, Victor Valley, and Yucaipa. The following school districts in Riverside County: Banning, Beaumont, Coachella Valley, Desert Sands, Jurupa Valley, Moreno Valley, Palm Springs, and Riverside.

|

|

San Diego

|

All HS south of State Highway 56 in San Diego County and all HS in Imperial County.

|

|

San Francisco

|

All HS in Alameda, Contra Costa, Marin, San Francisco, San Mateo, and Santa Clara Counties.

|

|

San Jose

|

All HS in Santa Clara County.

|

|

San Luis Obispo

|

All HS in San Luis Obispo, southern Monterey, and northern Santa Barbara Counties.

|

|

San Marcos

|

All HS north of Highway 56 in San Diego County plus Capistrano and Saddleback Valley, Hemet, Lake Elsinore, Murrieta Valley, San Jacinto, Temecula, and Val Verde.

|

|

Sonoma

|

All HS in Lake, Marin, Mendocino, Napa, Solano, and Sonoma Counties.

|

Various campuses have made use of the enrollment management tools established by systemwide policies. Many campuses have tightened application deadlines, closed off spring term for new admissions (though this was largely reversed for spring 2011), and taken other steps to restrict enrollment. Some campuses have also put in place enhanced admission requirements as permitted under the system’s impaction policies.

All–Program Impaction. As discussed above, CSU–eligible students are guaranteed access to their local campus, even if it is an impacted campus. However, they are not ensured access to impacted programs at their local campus. This points to a potential weakness in CSU’s admissions policies. Admission to a campus is of little value if the student cannot be admitted to the major or program of his or her choice. This becomes especially problematic at campuses where a large percentage of programs are impacted. Figure 4 (see next page) specifies the number of programs impacted at each CSU campus for fall 2011, and shows the five campuses where program impaction is extensive. As discussed earlier, for years all programs at Cal Poly have maintained admission standards higher than systemwide eligibility. Other campuses over the years have declared more and more programs impacted. Then, in fall 2009, SDSU became the second CSU campus to declare all its programs impacted, effectively ending its local admission guarantee. This can be seen as an important milestone in the weakening of CSU’s systemwide policy of serving regional needs—especially because two more campuses quickly followed SDSU and declared all their programs impacted. Below we discuss the shift at SDSU to illustrate in more detail the effects of all–program impaction on local access.

Figure 4

Impacted CSU Undergraduate Programs and Campuses

For 2011–12 Academic Year

|

|

Undergraduate Programs

|

|

Impacted

|

|

Campus

|

Total

|

Impacted

|

|

Campus?a

|

|

Bakersfield

|

24

|

1

|

|

|

|

Channel Islands

|

14

|

1

|

|

|

|

Chico

|

33

|

2

|

|

Yes

|

|

Dominguez Hills

|

27

|

2

|

|

|

|

East Bay

|

30

|

2

|

|

Yes

|

|

Fresno

|

30

|

2

|

|

Yes

|

|

Fullerton

|

30

|

30

|

|

Yes

|

|

Humboldt

|

25

|

1

|

|

Yes

|

|

Long Beach

|

32

|

15

|

|

Yes

|

|

Los Angeles

|

31

|

5

|

|

Yes

|

|

Maritime Academy

|

2

|

0

|

|

|

|

Monterey Bay

|

22

|

0

|

|

|

|

Northridge

|

28

|

1

|

|

Yes

|

|

Pomona

|

31

|

4

|

|

Yes

|

|

Sacramento

|

31

|

4

|

|

Yes

|

|

San Bernardino

|

29

|

3

|

|

Yes

|

|

San Diego

|

35

|

34b

|

|

Yes

|

|

San Francisco

|

36

|

9

|

|

Yes

|

|

San Jose

|

36

|

35b

|

|

Yes

|

|

San Luis Obispo

|

25

|

25

|

|

Yes

|

|

San Marcos

|

20

|

4

|

|

Yes

|

|

Sonoma

|

23

|

8

|

|

Yes

|

|

Stanlislaus

|

24

|

2

|

|

|

Between 1996 and 2010, SDSU experienced a rapid increase in enrollment demand, with the number of applications for admission almost tripling. Although it received money for growth, high enrollment demand at the popular campus exceeded available slots. Over the years, the campus adopted an array of measures to manage its enrollment, including priority deadlines and mandatory summer remediation courses, as well as campus and program impaction.

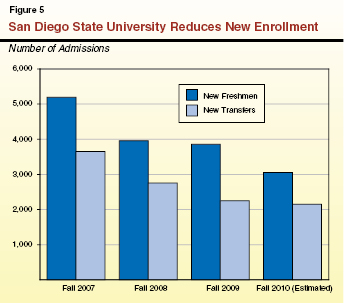

Campus Reduces New Enrollment. Responding to systemwide budget constraints in 2008, the CSU Chancellor’s Office reduced the amount of funding it allocated to most campuses, including SDSU, with the expectation that campuses would accommodate the reductions by enrolling fewer students. Accordingly, SDSU reduced the number of enrollment slots available for both freshmen and transfer students, as illustrated in Figure 5.

Enrollment Reductions Create New Tension Between Local and Nonlocal Applicants. The reduction in enrollment slots for a growing number of new applicants made SDSU admissions even more competitive. Among other things, this increased the stakes of maintaining a local guarantee under campus impaction. If all eligible local students continued to be admitted using minimum systemwide eligibility criteria, then enrollment reductions would be concentrated on out–of–area students. Campus officials expressed concern about how this could affect certain measures of student performance on campus (see nearby box).

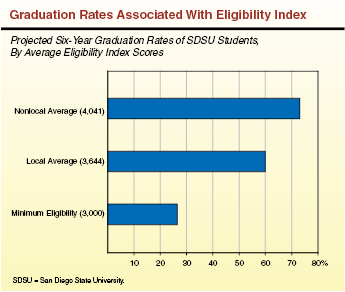

|

When budget constraints forced San Diego State University (SDSU) to admit fewer students, the existing local guarantee would have required that enrollment reductions be concentrated among nonlocal students. Because local applicants would be held to a lower admission standard than nonlocal ones, the result could be a reduction in the average level of preparation of incoming students. This, in turn, could depress graduation rates at the campus. The figure below shows how graduation rates are related to eligibility index scores at SDSU. Campus officials cited this issue as one reason to relax the local guarantee. The campus president emphasized this point in press interviews saying, “At some point, I’ve got to place my bet on the student that’s most likely to be able to succeed and graduate.”

While limiting local students probably helps somewhat to raise graduation rates at SDSU, it does not necessarily improve systemwide performance. For instance, having a higher percentage of better–prepared nonlocal students at SDSU means that the graduation rates at the CSU campuses they otherwise would have attended are now somewhat lower. In essence, limiting preference for local students allows for the grouping of better–prepared students at particular campuses, leaving the less–prepared students to attend other campuses. We discuss this issue further in the “Statewide Policy Implications” section later in this report.

|

Upper division transfer students have the highest admission priority in the CSU system. Like many other campuses, SDSU offers “Transfer Admission Guarantees” (TAGs), whereby students are promised upper–division transfer admission to SDSU in a specific major upon satisfactory completion of specified coursework at a community college. With increased competition for freshman enrollment at SDSU, many students make use of TAGs.

Recent budget reductions have forced SDSU, like other campuses, to make adjustments to admission guarantees. Predicting that there would not be enough transfer enrollment slots in fall 2010 to accommodate all transfers who met the 2009 TAG, SDSU revised its TAG for 2010. The changes are outlined in Figure 6. The main differences between the two agreements are the requirements to complete all transferable courses, including all major preparation courses, at a local community college. Although these changes shrink the number of students guaranteed transfer admission to SDSU, they do continue to prioritize admission for students who have attended local community colleges.

Figure 6

Requirements for the San Diego State University (SDSU) Transfer Admission Guarantee

|

|

2009 Requirements

|

2010 Requirements

|

|

“Golden Four”

|

Complete General Education (GE) requirements in oral communication, written communication, critical thinking, and math/quantitative reasoning with “C” or higher grades.

|

No change.

|

|

Grade Point Average (GPA)

|

Meet the GPA requirement for the major listed in the SDSU General Catalog.

|

Meet the GPA requirement for the major or 2.4 whichever is higher.

|

|

Units

|

Complete a minimum of 60 transferable semester units.

|

No change.

|

|

Local Coursework Requirement

|

At least 50 percent of transferable coursework must be from a local community college or SDSU.

|

100 percent of transferable coursework must be from a local community college or SDSU.

|

|

General Education

|

Complete a certified GE package of 39 units (CSU GE or IGETC) or any applicable lower division GE pattern listed in the SDSU catalog.

|

No change.

|

|

Major Preparation

|

Complete at least two courses of major preparation listed in the SDSU General Catalog.

|

Complete all major preparation listed in the SDSU General Catalog, at a local community college.

|

Concerns Expressed About Course Availability. Even though the new TAG preserves guaranteed admission for students who meet certain requirements, there has been some concern that it is not always possible for students to meet those requirements. The seven local community colleges in SDSU’s admission area expressed particular concern with the requirement that students complete 100 percent of their major preparation requirements at a local community college, owing to the fact that some of the required courses are not available at all the community colleges. In fact, major preparation for only 6 of the top 13 majors can be completed at all the local community college campuses. For example, two required courses for sociology transfers are not available at any of the seven local community colleges. When a needed transfer course is not offered, the student may consider the SDSU cross–enrollment option. But cross enrollment is at the discretion of the campus, on a space–available basis. Cross–enrollment applicants do not necessarily receive course priority over the university’s regularly enrolled students.

Effect on Transfer Students. As it turned out, 750 applicants met all of the new TAG requirements for fall 2010. However, the campus had about 2,150 slots available to accommodate transfer students. To fill the remaining slots, SDSU admitted additional transfer students in the following priority order:

- Applicants who met TAG requirements but with 50 percent of their work from local community colleges (283).

- Applicants from community colleges adjacent to the service area who completed all required transfer work and applied to a major that was not already at its enrollment limit (64).

- Local service area applicants missing some portion of coursework for an undersubscribed major (865).

- Out–of–area applicants who met 100 percent of required transfer work (270).

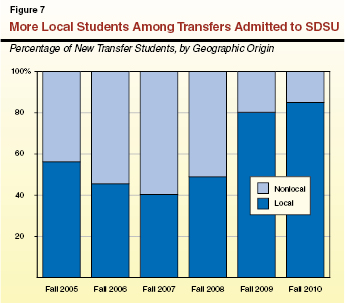

Under these new requirements about 1,900 transfers from the local area were admitted. This represents 85 percent of the total transfer enrollment slots. Figure 7 shows the proportion of local transfer admissions from 2005 to 2010. As reflected in the figure, SDSU has increased the priority given to local transfer students in the past two years.

Some transfer applicants who are denied admission to SDSU have other options within the CSU and UC systems, provided they have the flexibility to leave the region. At all CSU campuses except Cal Poly, transfer students receive priority over freshmen. More than half of these campuses are impacted for transfers, however—they impose supplemental eligibility criteria for nonlocal applicants. The San Diego–area community colleges also have TAGs with all UC campuses except Los Angeles and Berkeley. In fact, San Diego–area transfer center directors and community college counselors report that it is now easier for a local community college student to transfer to University of California, San Diego (UCSD) than SDSU. The UCSD accepts all transfer students who have completed (1) the required courses in English and mathematics, (2) at least 60 transferable units, (3) the Intersegmental General Education Transfer Curriculum, and (4) two regular community college terms, as well as achieved a cumulative GPA of at least 3.0. (Some majors may require completion of additional specific major preparation course work.) Completing these requirements guarantees junior standing in the major.

More controversy was generated when SDSU next tightened enrollment of local first–time freshmen. On September 10, 2009, SDSU requested approval from the Chancellor’s Office to declare full impaction for freshman admission in all programs. Six days later, SDSU received official approval and was able to increase eligibility standards for all freshman students. The campus thus ended the local admission guarantee for high school students, who were previously guaranteed admission if they met the minimum CSU eligibility requirements. (Figure 8 shows SDSU’s local area.)

Local Concerns Raised. Officials in local high school districts and community colleges, as well as some community organizations, expressed vocal concern about some of the policy changes. One objection concerned the short time frame for local students to make alternate plans; the policy change was made public about two weeks before the start of the application period. More fundamental were objections that (1) high school students in San Diego, unlike students in other parts of the state, would not be assured access to their local CSU campus, and (2) some community college students who had been following SDSU’s transfer rules suddenly faced revised admissions criteria. We examine the effects of the policy changes in more detail below.

Under the new admission policies, CSU–eligible local high school graduates are no longer guaranteed admission to SDSU. Instead, local students must compete with out–of–area students for admissions slots (although local students receive extra eligibility index points to enhance their competitiveness).

Students Turned Away. Of the almost 4,800 local applicants to SDSU who met minimum CSU requirements for the fall 2010 term, about 1,740 were denied admission under the new policy. About half (934) of these students accepted SDSU’s offer to be placed on a wait list. As slots became available, 82 of these students were offered admission, and 51 of them ultimately enrolled for the fall term. Rejected eligible applicants were also offered the opportunity to complete lower–division coursework at a local community college within three years and be guaranteed admission to SDSU as a transfer student.

A local student who meets CSU systemwide eligibility criteria, but who is not granted admission to SDSU, remains eligible for admission to another campus within the system. However, several factors could impede this option:

- The student would have to apply to the other institution by the November 30 deadline, but would be unlikely to hear from SDSU on admissions decisions until the spring.

- The CSU system does not maintain a centralized application process, and SDSU does not redirect to other campuses applicants who are denied admission.

- The student would have to be able to relocate to attend the out–of–area institution. This could prove difficult for students with local family or work obligations.

- Several other campuses are designated as impacted and can set higher requirements for nonlocal students. San Diego students who apply to those campuses must meet the higher standards, and must compete with other nonlocal students from across the state for a limited number of slots.

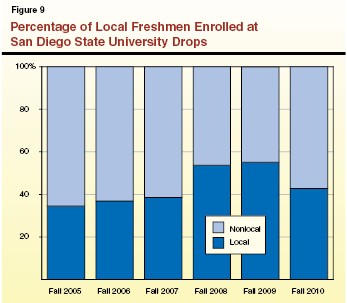

Shift in Student Population. As shown in Figure 9, local students’ share of new student cohorts increased steadily from 2005 through 2009, when they constituted 55 percent of new students. This percentage dropped to 43 percent in 2010, after SDSU eliminated the local guarantee. At the same time, the university established a floor of 37 percent for the share of the new student cohort to be held by local students.

Historically, most CSU campuses have drawn students primarily from high schools and community colleges in the same region. For many years, there was little difficulty in meeting demand from local and nonlocal students alike, as all campuses (with the exception of Cal Poly) had the capacity to accept all applicants to at least some programs. As enrollment levels grew to fill much of that capacity, some campuses became unable to accept all eligible applicants. In response, the Trustees adopted policies to manage enrollment while protecting local access. (As described in the nearby box, recent legislation strengthens protections for local access.) Some campuses continue to embrace the regional role assumed by that system policy, but others are adopting more of a “destination campus” identity that is at odds with a regional role. This tension will likely increase as more programs become impacted.

|

Legislation enacted in 2010 gives additional support to California State University’s (CSU’s) regional role. In particular, two new statutes strengthen CSU’s commitment to local applicants.

Chapter 262 (AB 2402, Block) effectively ends CSU’s policy to expedite new impaction efforts. Chapter 262 requires that a campus provide specified public notice and hearings when it proposes a change in admissions that would affect applicants from the campus’ local service area. (Such proposals could include major impaction or changes to transfer admission criteria.) Once a campus has satisfied those requirements, the campus may submit the proposed change to the system Chancellor for approval. If the proposed change stems from constraints on resources, it can become effective six months after approval by the Chancellor. If the change is not based on resources constraints, the change cannot become effective until at least one year after approval by the Chancellor.

Chapter 428 (SB 1440, Padilla) creates an associate degree for transfer for community college students that, beginning in fall 2011, guarantees eligibility for transfer to a CSU baccalaureate program under certain conditions. While the legislation does not guarantee admission to a specific major or campus, it requires that CSU grant such students priority admission to their local campus and to a major or program determined to be similar to the student’s community college major. |

This raises important policy questions about how CSU should carry out its Master Plan responsibility to accept all eligible applicants somewhere in the system, and in particular its role in meeting regional education needs. In general, we believe that eligible applicants to CSU should be able to attend their local campus. We realize, however, that achieving this involves important tradeoffs and other considerations, which we discuss below.

Integration Within the Higher Education System. The Master Plan envisions CSU as part of a multifaceted higher education system. For that system to work properly, there needs to be sufficient coordination and integration among the component institutions. (See an earlier publication from this Master Plan at 50 series: “Greater Than the Sum of Its Parts—Coordinating Higher Education in California.”) For example, the different eligibility targets assigned to the three public segments were designed to balance the desire to maintain a limited number of selective campuses (at the UC) with universal access to higher education (through the open–access community colleges with a transfer pathway to the universities). Similarly, the Master Plan balances the need to address different types of public interests through governance structures that focus at the state level (UC’s Board of Regents) and the local level (locally elected boards of trustees in each community college district).

The CSU tends to occupy the middle ground with regard to many of the Master Plan’s balancing efforts. The size of its eligibility pool is between that of UC and CCC, as are its academic selectivity, degree of campus autonomy, instructional costs, and the number of campuses spread across the state. With regard to the geographic focus of individual campuses, we believe it makes sense for CSU similarly to occupy a position between UC and CCC. The UC’s admissions policy guarantees students access to the system, but not to any particular campus. As a result, most UC campuses serve a diverse group of students from across the state. In fact, at every UC campus, local students constitute a minority of enrollees. Conversely, students apply to each CCC campus individually, and each campus controls its own admissions process. In this context, it would make sense for CSU to focus its admissions process at a regional level, ensuring eligible students access to a campus within their own region.

Aligning Access. A regional focus for CSU helps to justify the existence of two public university systems whose eligibility pools significantly overlap. More practically, it can help ensure meaningful university access for eligible applicants. Simply guaranteeing that all eligible students are offered admission somewhere in the UC and CSU systems may not be enough for students whose family or work obligations make relocating to a different region impractical. Many students at CSU in particular find themselves in these circumstances.

On the other hand, granting preference to local students over out–of–area students could be perceived as inequitable—particularly when the out–of–area student is better qualified. Moreover, given that CSU campuses differ in terms of size, campus amenities, program offerings, student bodies, and other characteristics, there could be situations when a student’s local campus is not the best suited to that students’ needs.

While acknowledging that there is no ideal approach to local eligibility, we believe that ensuring local access to all eligible students is more important than maintaining equal admissions criteria for all applicants to a given campus. Given that some potential students are unable to relocate outside of their region and the existence of UC campuses as statewide institutions, we conclude that providing practical access to all eligible CSU applicants is more important than maintaining equal admissions standards for all.

Use of Existing Capacity Also a Factor. The dilemma of choosing between local and out–of–area applicants stems in part from a misalignment between enrollment demand and the enrollment capacity of individual campuses and programs. Thus, the policy problem could be mitigated by better aligning resources with demand. In recent years, for example, some campuses have struggled to fill all the enrollment slots allocated to them by the Chancellor’s office, while other campuses have had to turn away students. Similarly, many campuses have departments with fairly low utilization of classroom space while others are filled beyond capacity. Moreover, almost all CSU campuses—even those that have been declared impacted—have considerable unused capacity during the summer months. Of course, the ability to serve more students requires both physical space and the financial resources to pay for faculty and staff. And the ability to shift resources to meet changing demand requires flexibility that is not always possible with existing tenure and other labor rules. But it is evident that there are opportunities to better meet enrollment demand with existing financial and physical resources.

While the Master Plan does not specifically assign CSU a regional role within the state’s tripartite public higher education system, CSU campuses—through their admissions policies and other policies—have largely focused on regional education needs. Demographic changes over the past 50 years, as well as changes in the state’s education needs, have generally increased the importance of that regional focus. However, recent enrollment management efforts undertaken at campuses such as SDSU have the potential to weaken that regional role. We recommend that the Legislature take steps to formalize a regional education role for CSU, and direct CSU to modify its enrollment policies accordingly.

Current statute specifies the types of programs and degrees CSU is to offer, but not the geographic focus of campuses’ enrollment decisions for those programs. Statute does not address how CSU should define its eligibility pool. Although the original Master Plan document recommended that CSU draw from the top one–third of high school graduates, this provision was never codified.

Assign Specifically Regional Role. We recommend that the Legislature amend statute specifically to assign CSU a regional role within the state’s public higher education system. Such an amendment could clarify the distinction between the UC and the CSU as public university systems. It could also specify that local students be given admission priority at CSU.

Codify Eligibility Targets. Because serving regional needs depends to a large extent on how eligibility is determined, we recommend that the Legislature codify its expectations for CSU’s eligibility pools. (A codified eligibility target for UC similarly would make sense.) The CSU could be directed to draw its freshman admissions from the top one–third of high school graduates, as originally called for in the Master Plan. Or a different target could be adopted if the Legislature felt it was warranted. Alternatively, the Legislature could do away with the Master Plan’s focus on a fixed share of high school graduates, and instead adopt some kind of “college readiness” standards that are not linked to any particular percentage of graduates.

As discussed above, some recent enrollment management decisions threaten to weaken CSU’s ability to serve a regional education role. Program impaction policies in particular may result in some CSU–eligible students having no guaranteed access to a campus in their region. We believe that those policies should be consistent with broader state expectations for the public higher education system.

Direct Chancellor’s Office to Align Policies With Amended Master Plan. If the Legislature amends state policy to clarify its intent with regard to CSU’s regional role, we recommend that it direct the Chancellor’s Office to review its admission, enrollment management, and other policies for consistency with its mission. Once this review is completed, CSU should amend its policies as necessary to ensure they are aligned with legislative intent. We recommend that the Legislature also direct the Chancellor’s Office to submit a report with the results of its review and an explanation of the steps taken in light of that review.