Although they receive less public attention now than at times in the past, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) are still significant public health issues, with thousands of people becoming newly infected with HIV in California every year. The state spends an increasing amount every year—over $1.2 billion from all sources in 2009–10—on a variety of programs to prevent HIV, treat HIV and AIDS, support individuals living with HIV and AIDS, and track the prevalence of these conditions. A significant portion of the federal funding that California receives for these programs is based on the number of cases of HIV and AIDS that are reported to the state’s surveillance system.

In this report, we identify significant problems in the state’s ability to accurately track AIDS–related cases. These gaps in the surveillance database weaken the state’s ability to use it as an effective tool to track and respond to trends in the disease. These problems are also affecting the state’s ability to collect additional federal funding that could otherwise be available to offset the cost of state AIDS programs.

To remedy these problems, we recommend two actions that the state could take to enhance its competitiveness for the federal funding awards that are based on this surveillance data. Specifically, we recommend that the state Office of AIDS (OA) take steps to ensure that persons receiving services through state–supported programs are reflected in the HIV surveillance database. We further recommend that laboratories that must report HIV data to local health departments be required to report this data electronically. These changes, our analysis indicates, would make the state’s surveillance database more complete, improve the state’s knowledge of disease trends, and make the state more competitive for federal AIDS funding.

The state spends about $1.2 billion ($455 million from the General Fund) annually on medical treatment and programs related to HIV/AIDS. These include prevention, education, and testing programs; local and statewide surveillance and epidemiological studies; and programs that provide direct services to HIV–positive individuals such as the AIDS Drug Assistance Program (ADAP). In this report, we describe the state’s HIV surveillance system and its importance in determining California’s share of federal funds for HIV and AIDS. We assess significant problems we have identified in this system, and recommend two improvements that our analysis indicates would allow the state to address gaps in this data, better track the epidemic, and draw down a larger share of federal funds for AIDS–related programs.

Fewer Deaths, More Cases. Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) destroys a certain kind of blood cell (called CD4+, or T cells). These cells are crucial to the normal function of the human immune system, and a reduction in the number of these cells reduces the immune system’s ability to fight disease. Although a person infected with HIV may not show symptoms until several years later, the virus is active in the body and, if untreated, the HIV disease will progress to AIDS. An AIDS diagnosis is made when the count of CD4+, or T cells, falls below a certain level or when the person has a history of infections commonly associated with AIDS. The number of new AIDS diagnoses and the number of deaths from AIDS have generally decreased every year since the introduction of effective drug therapy that prevents progression of HIV to AIDS.

However, although fewer people are dying from AIDS, the total number of HIV cases in California is still increasing every year. In California, surveillance of HIV/AIDS and related programs are coordinated by the state OA within the Department of Public Health (DPH). The OA estimates that there are between 68,000 and 106,000 persons infected with HIV in California, and another 68,000 persons who have AIDS. The office also estimates that there have been about 5,000 to 7,000 new cases of HIV infection per year in the state for the past several years.

More People Living With HIV. There is no “cure” for HIV disease or AIDS, but access to more effective drug therapies has allowed many people infected with HIV to reduce the level of virus in their body sufficiently to stay healthy. The drug treatment that helps suppress HIV, however, is far from simple. Medications are very costly and need to be taken daily for the rest of a person’s life, side effects of the medications may be severe, and following the required treatment regimen can be complex.

If current trends in HIV incidence persist, there will be thousands more individuals seeking this treatment every year, putting significant strain on the public resources available to combat this disease. In addition to surveillance programs, the OA also administers a variety of HIV/AIDS–related programs, including ADAP, which provides necessary drug therapies to over 35,000 individuals with HIV or AIDS. Other state departments, such as the Department of Health Care Services (which administers the state’s Medi–Cal Program) and the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR), also provide medical services to individuals with HIV and AIDS. In total, the state spends over $1.2 billion from all fund sources on HIV/AIDS programs.

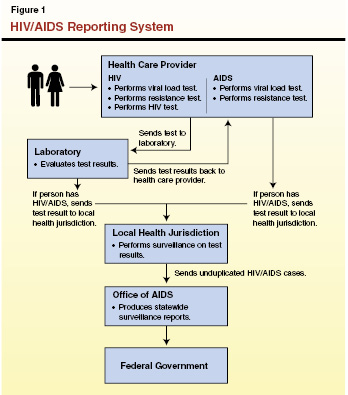

A Tool to Protect Public Health. Surveillance of diseases and conditions is an ongoing, systematic process whereby public health authorities collect and analyze reports of incidence of the disease. Certain diseases and conditions are considered “reportable,” meaning that state law requires providers and laboratories to report cases to local public health jurisdictions (LHJs). The LHJs are departments under the authority of a health officer. State and local surveillance workers in California track over 80 reportable conditions; examples include tuberculosis, hepatitis, measles, and sexually transmitted diseases as well as HIV and AIDS. The data collected informs those responsible for prevention and control of these diseases, and are used to allocate public health system resources to where they are most needed. Some of the key steps in this surveillance process are discussed below. See Figure 1 for an overview of this process.

Testing. The state’s surveillance of HIV and AIDS begins when an individual takes an HIV test, perhaps in a health care provider’s office or a public health clinic. The sample is generally sent to a laboratory for testing, the laboratory provides a positive or negative result back to the provider who ordered the test, and the provider diagnoses the case. These HIV/AIDS lab results and diagnoses are then reported to authorities as discussed below.

- Case Identification. When laboratory test results indicate that a person is HIV–positive or has AIDS, the laboratory is required to transmit this information to an LHJ as well as to the provider who ordered the test. In addition, when the provider receives positive test results back from the laboratory and has diagnosed a case of HIV or AIDS, the provider is also required to transmit this information to the LHJ. Generally, once LHJs receive this information (usually from the laboratory), they contact the health care provider to confirm that a person under their care has a new diagnosis. Diagnoses for HIV and AIDS are tracked separately using this process.

- Case Reporting. Once the case is identified as a new diagnosis, surveillance specialists at LHJs collect additional demographic and health–related information and transmit a Confidential Morbidity Report (CMR) for each confirmed case to the state OA. In turn, the OA compiles these reports, removes duplicate reports, and submits a final report to the federal government. This report is used to track disease trends nationally and to allocate federal resources for HIV.

This information is used by the state OA for epidemiological tracking, for allocating resources within the state, and for measuring progress in combating HIV.

HIV/AIDS Historically Treated Differently Than Other Diseases. In the early years of the epidemic, policies surrounding HIV/AIDS emphasized the autonomy and privacy rights of people with or at risk for infection rather than traditional public health concerns. This has led to HIV/AIDS being treated differently than other diseases and conditions in regard to many testing, consent, and reporting requirements. For example, HIV has different reporting requirements than other diseases. Laboratories can use a variety of methods to report most diseases to LHJs, including phone, fax, or secure electronic delivery. Laboratories must report HIV, however, using methods such as hand delivery or registered mail.

Another example concerns written consent requirements. Generally, routine medical tests do not require the person being tested to complete and sign a written consent form prior to their being tested; verbal consent is usually sufficient if required at all. Until Chapter 550, Statutes of 2007 (AB 682, Berg) removed the written consent requirement from routine HIV testing in California, the state required a separate consent form before an HIV test was performed. Consistent with Chapter 550, the public health community has begun to move away from exceptional treatment of HIV/AIDS and towards handling it more like other diseases with regards to testing, consent, and reporting. For example, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommended in 2006 that testing for HIV infection be performed routinely for all patients age 13 to 64 and that written consent should not be required by the provider in order for an HIV test to be conducted.

HIV Reporting Requirements. Diagnosed cases of AIDS have been reported by California authorities since 1983. However, the state first began requiring laboratories and providers to report HIV infections to LHJs in 2002. Before that time, infections of HIV were reported to LHJs using a code instead of the individual’s name. Reporting by name is the common practice for most diseases. California changed to names–based reporting for HIV infections after it became clear that federal funds being received by the state for AIDS programs were at risk if it did not adopt such a system.

The Ryan White Comprehensive AIDS Resources Emergency (CARE) Act, the main federal funding source for HIV/AIDS programs, was reauthorized by Congress in 2005. Under a draft version of the bill, funding would have been allocated to states based primarily on the number of HIV and AIDS cases that each state reported by name. Since California did not yet report HIV cases by name, it would have been at a significant disadvantage in the allocation of Ryan White CARE Act funding. However, a compromise version of the federal law was enacted that allowed states like California with code–based reporting systems to retain most of their federal funds, but with a modest penalty in their federal awards. In addition, all states were expected to begin reporting HIV infections by name.

In response to the federal law, the Legislature enacted Chapter 20, Statutes of 2006 (SB 699, Soto), requiring health care providers and laboratories to report HIV cases by the patient’s name rather than code, beginning in 2006. Funding for the Ryan White CARE Act was reauthorized again by Congress in 2009, in a form that increases the penalty for states that do not report HIV and AIDS cases by name beginning in 2012. By 2013, the allocation of this federal funding to states will be based entirely on the number of HIV and AIDS cases reported by states by name.

HIV Reporting Falls Short. Despite the state’s ongoing shift to name–based reporting, California does not have an accurate count of HIV cases. As of April 2009, only about 36,000 cases of HIV had been reported by LHJs to the state by name. Based on what is known about nationwide prevalence and the epidemiology of the disease, the OA estimated in 2008 that there are actually between 68,000 and 106,000 HIV (non–AIDS) cases in California. Thus, the current name–based count of 36,000 likely represents only one–third to one–half of actual HIV cases. There are a variety of reasons for this significant discrepancy. For example, some individuals do not know they are infected, and other cases have not yet been captured by the name–based system in the course of routine surveillance. Under current policies and practices, it is likely that California will not have an accurate name–based count of persons with known HIV infection for some time to come. The situation is different for AIDS. Because California authorities have reported AIDS cases by name since 1983, the state’s AIDS database is relatively complete.

Lack of Complete Data Affects Federal Funding to Prevent and Treat HIV/AIDS. Completeness and accuracy of the state’s HIV surveillance data are essential for the state to track current epidemiological trends in the disease and coordinate an effective public health response. Reliable data on the prevalence of HIV is also important if the state is to remain competitive for federal funds that could assist in the prevention and treatment of the disease. The Ryan White CARE Act provides approximately $125 million in federal funding per year to California for HIV prevention programs, ADAP, and a variety of other care and support services. Additional funds are provided to several local jurisdictions within the state that have a high HIV/AIDS prevalence.

However, the state is currently not receiving its maximum potential amount of federal funding from the act because California’s name–based HIV reporting system is incomplete. As noted above, the federal law allocates funding based mainly on each state’s share of the total HIV and AIDS cases nationally that have been reported by name. States such as California that have not yet completed a name–based count of HIV cases are in effect receiving only partial credit for cases that it has reported in the past without names. As a result, the Ryan White CARE Act funding provided to California for HIV code–reported cases is discounted and the state is at a disadvantage in obtaining federal funding.

Like California, other states are also improving their reporting systems and increasing the number of their cases that are reported in compliance with federal law. As a result, we cannot estimate exactly the financial benefit to California from improved reporting. However, we estimate that a significant increase in the number of cases reported by name would increase California’s competitiveness for this funding, perhaps increasing its grant award by several millions to the low tens of millions of dollars annually. Such increases in federal funding could offset the state’s General Fund costs for HIV/AIDS programs, leading to a cost savings or slower rate of growth in General Fund costs for these programs.

In the remainder of this report, we discuss two recommended improvements to the state’s surveillance system for HIV and AIDS that our analysis shows could expedite the transition to a name–based system, thereby helping to ensure that California receives its maximum share of federal funds.

Some Clients Who Receive State–Supported Services Are Not Reported. As mentioned above, the state provides a variety of programs for individuals with HIV and AIDS. However, the state currently has no method for cross–checking to ensure that all individuals who receive these services are included in the HIV surveillance database. For example, the names of individuals who receive drugs through ADAP, the state–run drug assistance program, are not systematically included in the state’s HIV surveillance database. Recent analysis by the OA indicates that several thousand HIV–positive persons may now be receiving various state services but are not yet counted by name in the surveillance system. Some HIV–positive individuals who are receiving services through state–supported programs administered by LHJs are likewise not reflected in the surveillance database.

Some Steps Have Been Taken to Address Gaps in Reporting… The OA has taken some steps to address the gaps in reporting that we have identified. The OA is modifying consent forms for clients represented in the ADAP database, as well as the AIDS Regional Information and Evaluation System (ARIES) database (which includes clients receiving non–ADAP care services funded through the OA). These changes will allow the OA to disclose ADAP and ARIES client names to local health officers (LHOs). The LHOs, in turn, would be able to disclose client names to providers, thereby facilitating active surveillance at the local level to confirm and report additional HIV cases to the surveillance system. Additionally, the OA has provided specific guidance and technical assistance to local health departments to assist them in addressing these surveillance gaps.

...But Further Steps and Follow–Up Would Ensure Progress Is Made. In addition to the efforts involving the ARIES and ADAP databases, we believe further steps could be taken to ensure that the state strategically leverages its data resources to improve public health surveillance of HIV. For example, similar cross–checking should be performed with state correctional health data systems under the purview of CDCR. In order to remove legal ambiguity over whether state and local public health systems can share confidential information with health systems within CDCR and local jails, correctional health systems could be identified in the law as permissible entities with which state or local public health entities could exchange such data for the purposes of public health surveillance. Finally, we believe it would be beneficial for the Legislature to oversee the progress the state is making with using these new procedures to improve surveillance.

Electronic Lab Reporting Would Be More Efficient Than the Current System. As we noted earlier, laboratories are legally required to report to the state surveillance system the outcome of tests that indicate a diagnosis that someone is HIV–positive or has AIDS. Currently, however, laboratories are only allowed to submit HIV reports by what state law calls traceable mail, such as registered mail, or person–to–person transfer, such as hand delivery. They are not allowed to send reports indicating an HIV diagnosis to LHJs electronically. Notably, this is the case even though laboratories are allowed to submit test results for other types of diseases electronically.

Transmitting data in this manner is labor–intensive, both for laboratories and for local surveillance workers. For example, a large laboratory that relies on electronic medical records for its internal record keeping may nonetheless be required to print out a patient’s electronic medical record and mail it to an LHJ. The LHJ then must manually enter this data onto a different form in order to report the case to the state.

Electronic reporting of HIV lab results would be more timely and efficient, and increase the accuracy of data collection. Other states—such as Florida, Illinois, and Texas—have found that centralized lab reporting systems with these capabilities allow better monitoring of the data and improved oversight of local surveillance efforts. Such systems allow surveillance staff to track cases across jurisdictions in a timely manner and to more efficiently track related diseases, like sexually transmitted diseases or Hepatitis C, often seen in the HIV–positive population.

Electronic System Under Development Would Exclude HIV Reports. The DPH is currently developing just such a Web–based Electronic Laboratory Reporting (ELR) system in conjunction with a Web–based Confidential Morbidity Report application (called the Web–CMR) for the reporting of a variety of diseases, including hepatitis, measles, diphtheria, syphilis, and others. This new system, slated for completion in 2010, is intended to reduce data entry errors, streamline the reporting process to make it less labor–intensive, and enhance data security. For example, the electronic system could only be accessed through a secure data network. Any actions to access the data would be tracked, with system users limited to viewing only the specific data they were authorized to view.

We note that, while the reports would be housed in a central location, both the LHJs and the state would have simultaneous access to the reports. In other words, the state could view the reports entered into the system for each jurisdiction, but would not need to process or approve reports in order to make them available to LHJs. This aspect of the system design is critical to ensure that LHJs receive reports in a timely manner.

Current state law, Chapter 449, Statutes of 2008 (AB 2658, Horton), requires laboratories to submit all cases of “reportable disease and conditions” electronically, within one year of the establishment of the new state ELR system. However, HIV reports were specifically exempted from this requirement in order to allow DPH sufficient time to ensure the new system’s data architecture is not at variance with HIV–specific reporting requirements and that the system would meet federal standards for HIV reporting.

We recommend that the Legislature ensure that all individuals receiving state services are represented in the state surveillance database and require that HIV reports be included in the state’s new electronic reporting system.

Ensure Participants in State–Supported Programs Are in the Surveillance Database. We recommend that the Legislature take several steps to ensure that persons receiving services through state–supported programs are reflected in the surveillance database.

- First, we recommend the Legislature change state law to specify that correctional health systems are permissible entities with which state or local public health entities can exchange confidential public health data for the purposes of public health surveillance.

- Second, we recommend the Legislature require the OA to assess the discrepancy between the various databases that are used to track persons receiving HIV/AIDS services and the surveillance database, by performing cross–checking on a regular basis.

- Third, we recommend the Legislature require that the OA report to the Legislature annually, for a period of three years on the progress being made to address gaps in the surveillance system. This report should specify what actions are being taken to ensure that the state is leveraging data on persons receiving state–supported HIV–related services to improve the surveillance database, and report what progress is being made on a county–by–county basis and statewide.

If the Legislature finds that progress is not being made in addressing these surveillance gaps based on the recent changes in OA policy and practice, then it should re–assess at that time whether further changes are needed to the surveillance system. Finally, the OA should request additional statutory authority it deems necessary to improve surveillance of HIV, or request changes to state law that it identifies as restricting the department’s ability to accurately track HIV (provided it does not run afoul of general privacy and security provisions that apply to any confidential health–related information).

Require That HIV and AIDS Cases Be Included in Electronic Reporting. We recommend that DPH be directed to modify the state’s planned central ELR system to ensure that it is capable of including the reporting of HIV and AIDS test results. These modifications should be proposed in a form that makes them eligible under the Ryan White CARE Act for federal funding, and in a form that ensures that LHJs have uninterrupted and immediate access to all reports relating to their jurisdiction. If DPH determines that any statutory changes are necessary in order to allow HIV to be reported electronically, it should advise the Legislature so that it can modify state law to allow electronic reporting to move forward.

We would further recommend the enactment of legislation requiring laboratories to electronically report HIV test results within one year of the modification of the state’s central ELR system to incorporate HIV/AIDS. We note that this change would require DPH to modify current regulations that govern HIV reporting.

The state’s HIV/AIDS surveillance system consists of identification of cases by laboratories and health care providers, reporting of cases by local health departments to the state, and state reporting of total number of cases to the federal government. The state’s fairly recent shift to a name–based HIV surveillance database means that its data on the number of HIV cases is not complete, putting it at a major disadvantage in receiving federal funding to combat the disease. Efforts to enhance the number of cases reported will increase the state’s competitiveness for federal funding for HIV and AIDS. Any additional federal funding the state receives could be used to offset General Fund costs. Accordingly, in this report, we recommend that the OA develop a process to cross–check the records of individuals in state–supported HIV and AIDS programs to ensure that they are included within the surveillance database, and modify ELR rules that apply to other diseases to HIV cases. These two changes would make the state’s reporting of HIV cases more complete, improve the state’s surveillance of the HIV epidemic in California, and increase the state’s competitiveness for federal funds that are available for AIDS–related programs.